Manipulating the masses: How propaganda was used during World War I

World War I was a conflict that not only consumed the lives of the soldiers in the trenches and battlefields, but also had a powerful impact on the hearts and minds of millions at home.

This was done through the strategic use of propaganda. The proactive manipulation of people's attitudes through the media played a surprisingly pivotal role in shaping public opinion and mobilizing resources.

But how exactly was propaganda used during World War I?

What were the different types of propaganda employed by the warring nations?

And how did it influence society's perception of the war?

What is 'propaganda'?

The term 'propaganda' often carries negative connotations, associated with manipulation and deceit.

However, its roots are far more neutral, derived from the Latin 'propagare', meaning 'to spread or propagate'.

In essence, propaganda is about disseminating information, ideas, or rumors for the purpose of helping or injuring an institution, a cause, or a person.

It has always been a powerful tool of persuasion, with the capability of molding public opinion and directing collective action.

Propaganda, as a concept, is as old as human civilization itself: from the ancient Egyptians who used it to glorify their pharaohs, to the Romans who utilized it to control public opinion.

However, it was during World War I that propaganda was used on an industrial scale.

It leveraged the advancements in mass communication technologies such as the printing press, radio, and cinema.

Governments quickly realized that to sustain a war on a global scale, they needed not just the physical resources but also the psychological backing of their citizens.

How countries used propaganda

Each nation involved in the war had its unique propaganda strategies; h owever, there were common themes and techniques that transcended national boundaries.

Firstly, and most obviously, propaganda was used to justify the war, usually to portray it as a noble and necessary endeavor.

At the same time, it was used to demonize the enemy. To do this, it would paint them as a threat not just to the nation but to civilization itself.

In a much more benign way, it was also used to mobilize resources by encouraging men to enlist or for civilians to buy war bonds.

The British, for example, established the War Propaganda Bureau early in the war which enlisted famous writers and artists to create compelling propaganda materials.

These were distributed both at home and abroad.

The Germans, on the other hand, relied heavily on propaganda to maintain morale during the British naval blockade.

These blockades had prevented shipping from reaching German ports, which caused severe food shortages in Germany.

In comparison, in the United States, which entered the war later , the Committee on Public Information, which was established by President Woodrow Wilson, launched a massive propaganda campaign to build support for the war effort.

Interestingly, this campaign was not just aimed at adults but also at children, with propaganda materials distributed in schools to instill a sense of patriotism and duty from a young age.

In Russia, propaganda was used to try and maintain support for the war amidst growing social unrest, which eventually led to the Russian Revolution .

The Russian government used propaganda to portray the war as a fight against German imperialism.

This was aimed at appealing to the nationalist sentiments of the Russian people, but it had little effect in the end.

Common types of WWI propaganda

During World War I, propaganda was employed in a variety of forms, each designed to serve a specific purpose.

The types of propaganda used can be broadly categorized into recruitment propaganda, war bond propaganda, enemy demonization propaganda, and nationalism and patriotism propaganda.

Recruitment propaganda

One of the most visible forms of propaganda during the war was recruitment propaganda.

As the war dragged on and casualty numbers rose, it became increasingly important for nations to encourage more men to enlist.

Recruitment posters often depicted the ideal soldier as brave, honorable, and patriotic, appealing to a sense of duty and masculinity.

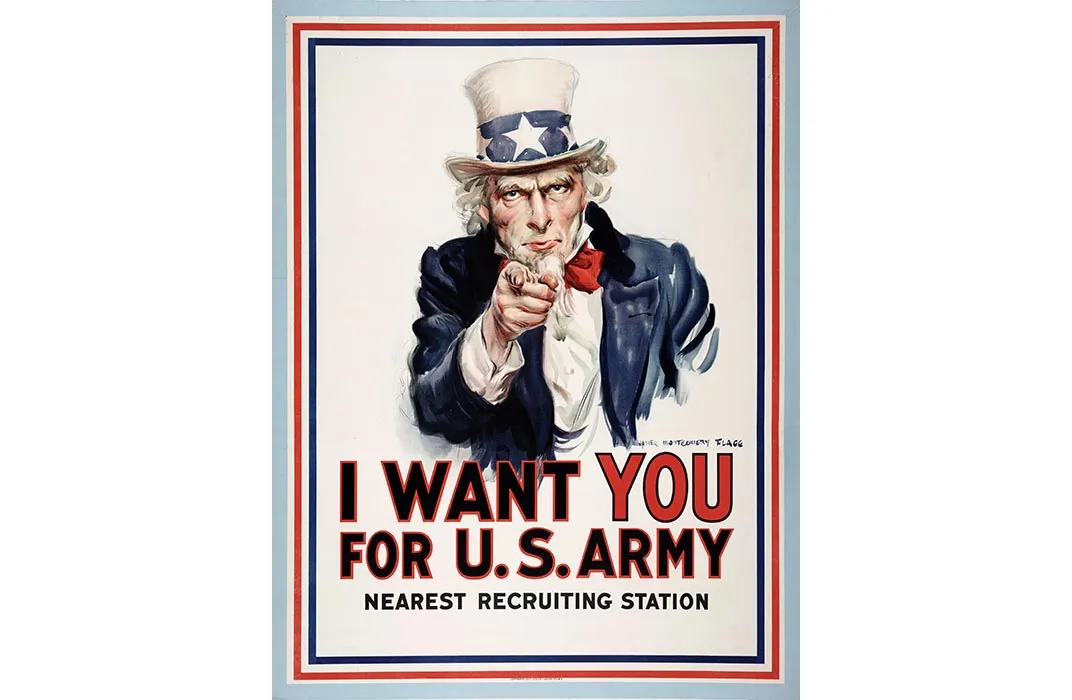

Iconic images such as Lord Kitchener's "Your Country Needs You" poster in Britain, or Uncle Sam's "I Want You" poster in the United States, became powerful symbols of the call to arms.

War bonds propaganda

Another crucial aspect of propaganda was the promotion of war bonds. Financing the war was a massive undertaking.

So, governments turned to their citizens for help.

War bond propaganda aimed to convince the public that purchasing bonds was both a financial investment and a patriotic duty.

These campaigns often used emotional appeals. It suggested that buying bonds was a way to support the troops and contribute to the war effort.

Enemy demonisation propaganda

The demonization of the enemy was a common theme in World War I propaganda.

By portraying the enemy as monstrous, barbaric, or inhuman, governments could justify the war and stoke a sense of fear and hatred.

This type of propaganda was often based on stereotypes or outright lies, such as the infamous "Rape of Belgium" campaign by the Allies, which exaggerated German atrocities to gain international support.

Nationalisation and patriotism propaganda

Finally, propaganda was also used to foster a sense of nationalism and patriotism.

This was especially important in multi-ethnic empires like Austria-Hungary or the Ottoman Empire, where loyalty to the state was not a given.

The resultant nationalistic propaganda often used symbols, myths, and historical narratives to create a sense of shared identity and purpose.

The impact on society

One of the most significant impacts of propaganda was its role in creating a culture of sacrifice and service, where everyone was expected to do their part for the war effort.

Furthermore, propaganda influenced the way the war was understood and remembered.

It created a narrative of the war that highlighted the heroism and sacrifice of the soldiers, while downplaying the horror and destruction.

This narrative was often uncritically accepted, leading to a romanticized and distorted view of the war.

Ultimately, the use of propaganda during World War I may have had a significant impact on society by introducing new methods of mass communication and persuasion.

The techniques developed during the war, from the use of posters and films to the manipulation of news and information, became a standard part of political and commercial communication in the decades that followed.

The crucial role of artists and designers

Artists and designers' skills were harnessed to create powerful images and messages.

They were, in essence, visual storytellers, crafting narratives of heroism, sacrifice, and patriotism that resonated with the masses.

A well-designed poster or illustration could convey a message instantly and emotionally.

As a result, artists and designers used a variety of techniques to maximize the impact of their work: from the use of bold colors and simple, striking designs to the manipulation of symbols and stereotypes.

There are a number of very famous examples form various countries. In Britain, o ne of the most famous examples is the "Your Country Needs You" poster, featuring Lord Kitchener.

The poster, designed by Alfred Leete, became an iconic symbol of the call to arms.

Its simple yet powerful design resonating with the British public.

In Germany, artists like Ludwig Hohlwein and Lucian Bernhard created striking posters that promoted war bonds and recruitment.

Their work, characterized by bold typography and dramatic imagery, was instrumental in maintaining morale and unity during the war.

Then, in the United States, artists like James Montgomery Flagg and Howard Chandler Christy created memorable propaganda posters.

Flagg's "I Want You" poster, featuring Uncle Sam, became one of the most iconic images of the war, while Christy's posters, featuring idealized images of women, appealed to a sense of chivalry and duty.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

History News Network puts current events into historical perspective. Subscribe to our newsletter for new perspectives on the ways history continues to resonate in the present. Explore our archive of thousands of original op-eds and curated stories from around the web. Join us to learn more about the past, now.

Sign up for the HNN Newsletter

The propaganda posters that won the u.s. home front.

Albinko Hasic is a PhD student at Syracuse University, whose research concerns propaganda.

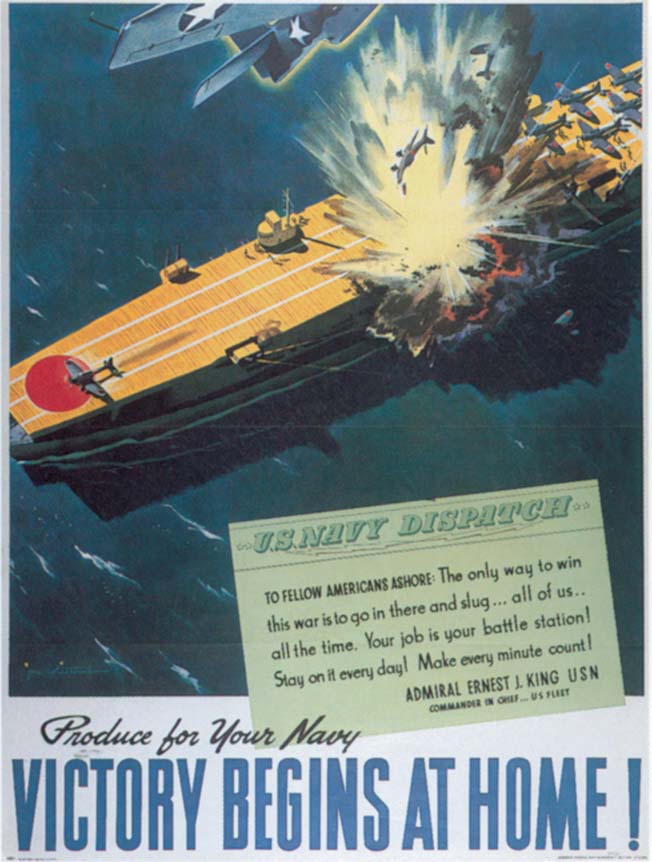

In 1917, James Montgomery Flagg created his iconic Uncle Sam poster encouraging American men to join the war cause with the clear message, “I want you for the U.S. Army!” as the U.S. ramped up preparations to enter World War I. Even though this was not the first instance of propaganda posters being employed on behalf of a war cause, the visual medium proved to be effective in the military’s recruitment drives and posters were routinely used to boost morale, encourage camaraderie, and raise esprit de corps . Posters were cheap, easily distributed, and fomented a sense of patriotism and duty. In World War II, the U.S. turned to artists once again in an attempt to influence the public on the home front. Today, these posters offer a glimpse into American society and the efforts to mold public opinion in the country.

Rolled out on a massive scale in World War I, the popularity of posters as propaganda only further increased in World War II. With the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. began mobilizing once again but not just militarily. The U.S. government leveraged hundreds of artists across the country to deliver important messages through visual means. This included some relatively famous artists such as the creator of Aquaman , Paul Norris, whose sketches were noticed by his superiors during his time in the military. The artists’ designs were not just focused on the rank and file of the military either. The Office of War Information (OWI) believed that the ‘home front,’ was just as sensitive to enemy misinformation, and went to work creating a series of posters specifically focused on the population back home as the engine of the war effort in Europe and the Pacific.

The designs and posters had a wide range in terms of messaging and design. Even though there was quite a number of posters in the U.S. with xenophobic or down right racist messaging and visuals, the majority centered around themes of tradition, patriotism, duty, and honor. This was further expanded on the home front with themes such as conservation, production, work ethic, buying war bonds, tending to “victory gardens,” encouraging women in the labor force, and cementing a common enemy in the eyes of the American public.

A Common Enemy Emerges

Several U.S. propaganda posters employed a tactic known as demonization. This involved portraying the enemy as barbarian , aggressive, conniving, or simply evil. Demonization included derogatory name calling including terms such as “Japs,” “Huns,” and “Nips,” among others. Several posters in the U.S tapped into demonization by showcasing the Japanese with overly exaggerated features and by recycling racist and xenophobic personifications.

This was often paired with messaging such as one anti-Japanese poster which portrayed Emperor Hirohito rubbing his hands saying, “Go ahead, please take day off!.” The tactic was clear, motivate the working population at home to avoid sick days through fear of the inhuman enemy who is planning an attack on the homeland at any moment.

Fear was a popular theme employed by artists, even with differing messages. In one poster, a giant Nazi boot is depicted crushing a small church with the language, “We’re fighting to prevent this.” Often, fear was utilized as a way to encourage the purchase of war bonds. Numerous posters portray children wearing gas masks or under the shadow of giant swastikas with clear messaging, “Buy war bonds to prevent this possible future.”

Conservation and Production

Some posters employed comedy as a way to break through, while at the same time tapping into the overarching fear of the enemy. For example, one poster, seemingly in an attempt to encourage carpooling, depicts an outline of Adolf Hitler riding shotgun with a commuter with the messaging, “When you ride alone, you ride with Hitler.” Others encouraged high production outputs by likening slacking off with aiding and abetting America’s foreign enemies. At the same time, others were more positivist in nature such as the famous Rosie the Riveter “We can do it!,” poster, encouraging women in the workforce.

Interestingly, many posters encouraged conservation and “victory gardens.” In an attempt to counterbalance rationing, the Department of Agriculture encouraged personal home gardens and small farms as a way to raise the production of fresh vegetables during the course of the war. Some scholars, such as Stuart Kallen believe that victory gardens contributed up to a third of all domestic vegetable production in the country during the course of the war. Posters espoused popular sentiments such as “our food is fighting,” “food is ammunition,” and “dig for victory.” Coinciding with this, posters also espoused the benefits of canning with messages such as, “of course I CAN,” and “can all you can.”

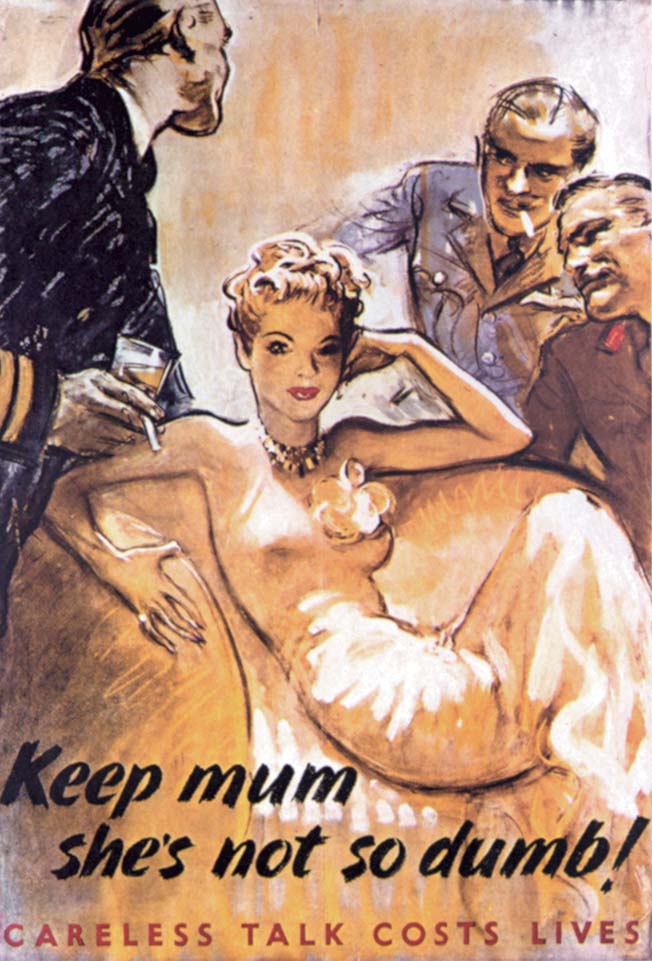

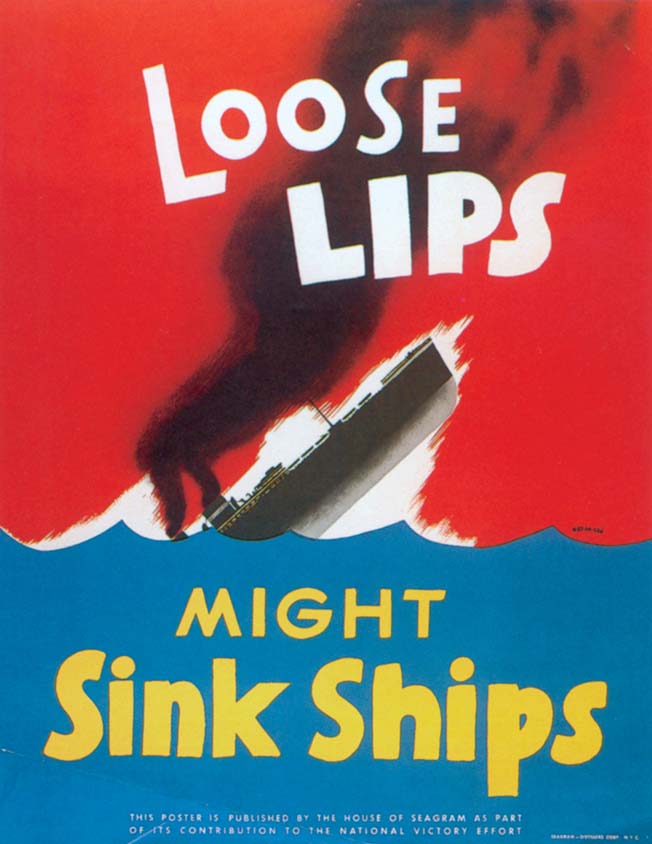

Loose Lips Sink Ships

Perhaps one of the most fascinating themes which were propagated on the home front is misinformation and “loose talk.” Some scholars have speculated that this theme emerged out of fear of domestic spies and foreign intelligence operations within the U.S. Others, however, maintain that the U.S. intelligence services had shut down any foreign intelligence networks even prior to America’s involvement in WWII. Their claim is that these types of messages merely aimed to dispel rumors and prevent a loss of morale at home and abroad. Whatever the case may be, the government asked illustrators to discourage the population at home from casual chatter about troop deployment, movement, and any other sensitive information which could be “picked up,” by enemy receptors or propagated on a large scale. The phrase, “ loose lips sink ships ,” emerged thanks in part to the work of Seymour Goff. Goff’s poster depicts a U.S. boat on fire, sinking with the words, “Loose lips might sink ships.” Similar messaging was also prevalent in Great Britain and Germany as well.

Just as World War II was fought with bullets, boats, tanks and planes, the war at home was fought with information stemming from sources such as movies, radio, leaflets, and posters. Artists suddenly became soldiers on the front to win the hearts and minds of the American public. Propaganda posters offer us an interesting insight into the objectives of the U.S. government and the war time aims of the mission to create consensus at home.

Humor and Horror: Printed Propaganda during World War I

«Propaganda in the form of posters, postcards, and trade cards flourished during World War I due to developments in print technology that had begun in the 19th century. Governments on both sides of the conflict invested in printed matter that rallied public sentiments of nationalism and support for the war while also encouraging animosity toward the enemy.»

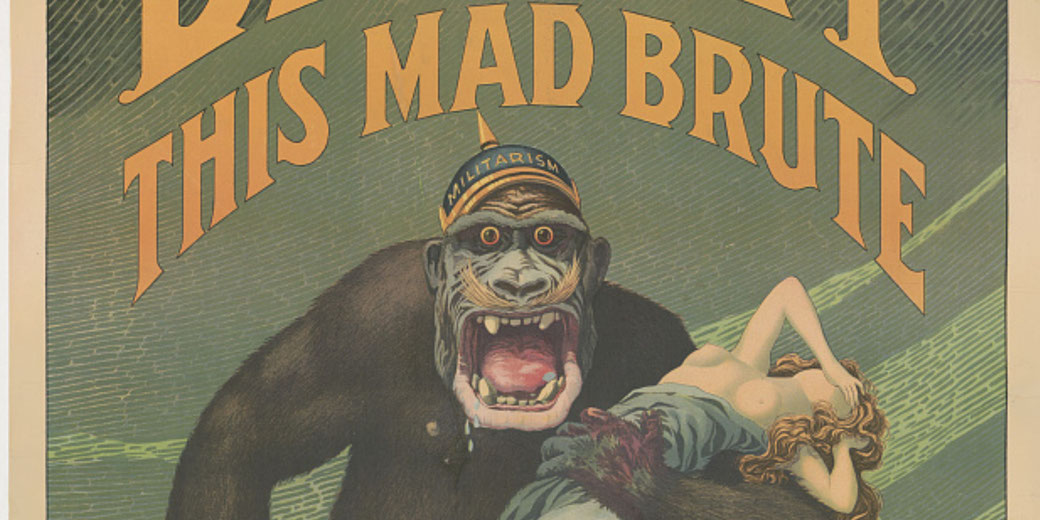

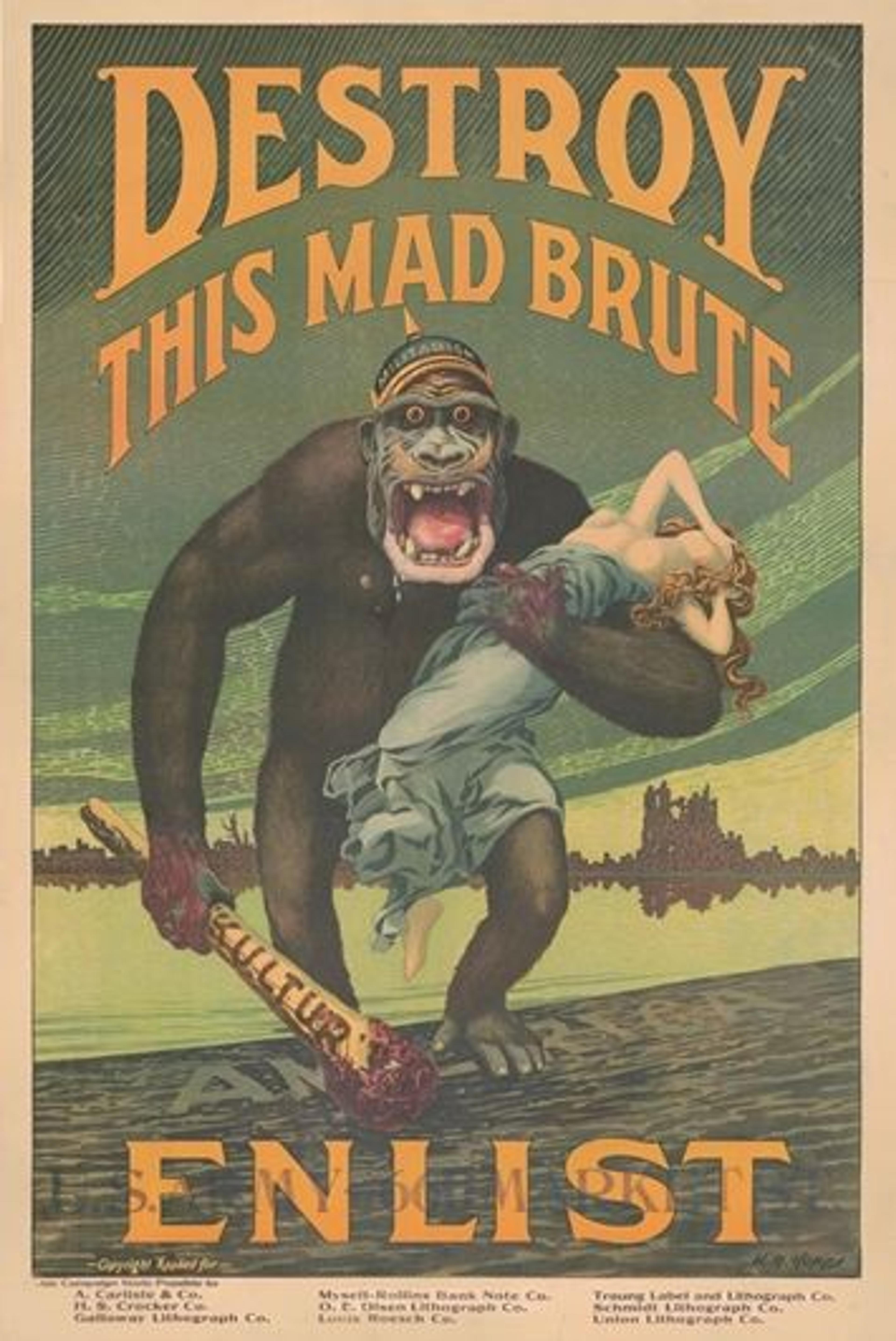

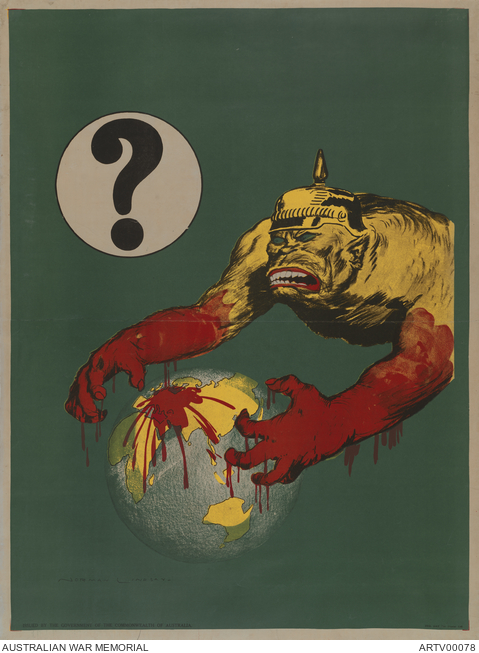

Left: Harry Ryle Hopps (American, 1869–1937). Destroy This Mad Brute: Enlist , 1917. Color lithograph, image: 38 3/4 x 25 5/8 in. (98.4 x 65.1 cm). Collection of Mary Ellen Meehan

During wartime, large-format, full-color posters plastered walls from city streets to classrooms. They mobilized support for the war effort, summoned donations to charities, encouraged participation in war bonds, and publicized victories in notable battles to a broad public. Illustrators of varying renown were called on to produce forceful images whose meaning could be quickly and easily grasped by a diverse audience.

Calling on American men to enlist, Harry Ryle Hopps's poster Destroy This Mad Brute: Enlist (1917) casts Germany as a barbarian who has arrived on U.S. shores, leaving behind a destroyed Europe. The "mad brute" wears a spiked helmet emblazoned with the word "militarism" and dons a mustache suggestive of Kaiser Wilhelm II's whiskers. He has abducted an allegorical figure of Lady Liberty and clenches the bloodied club of German Kultur (culture). The motif of the barbarous enemy abounds in propaganda issued by the Allied forces, and the ape-like figure in particular—a precursor to the title character in the 1933 film King Kong —spoke to an audience familiar with Charles Darwin's theories of evolution.

Right: Fritz Erler (German, 1868–1940). Help Us Win! Buy War Bonds ( Helft uns siegen! Zeichnet die Kriegsanleihe ) , 1917. Color lithograph, image: 22 3/4 x 17 1/2 in. (57.8 x 44.5 cm). Collection of Mary Ellen Meehan

On the German side, Fritz Erler designed Help Us Win! Buy War Bonds (1917) after making studies of soldiers at the front. The man depicted in his poster wears a type of steel helmet introduced by the German army in 1916. The gas mask on his chest, the two "potato-masher" grenades in a pouch dangling from his left shoulder, and the barbed wire that surrounds him are all visual hallmarks of World War I. The artist formed the soldier's pupils into small crosses, harnessing Christian symbolism to cast him as a noble and timeless figure. The poster was produced in three sizes and was also issued as a postcard to promote war bonds to German citizens.

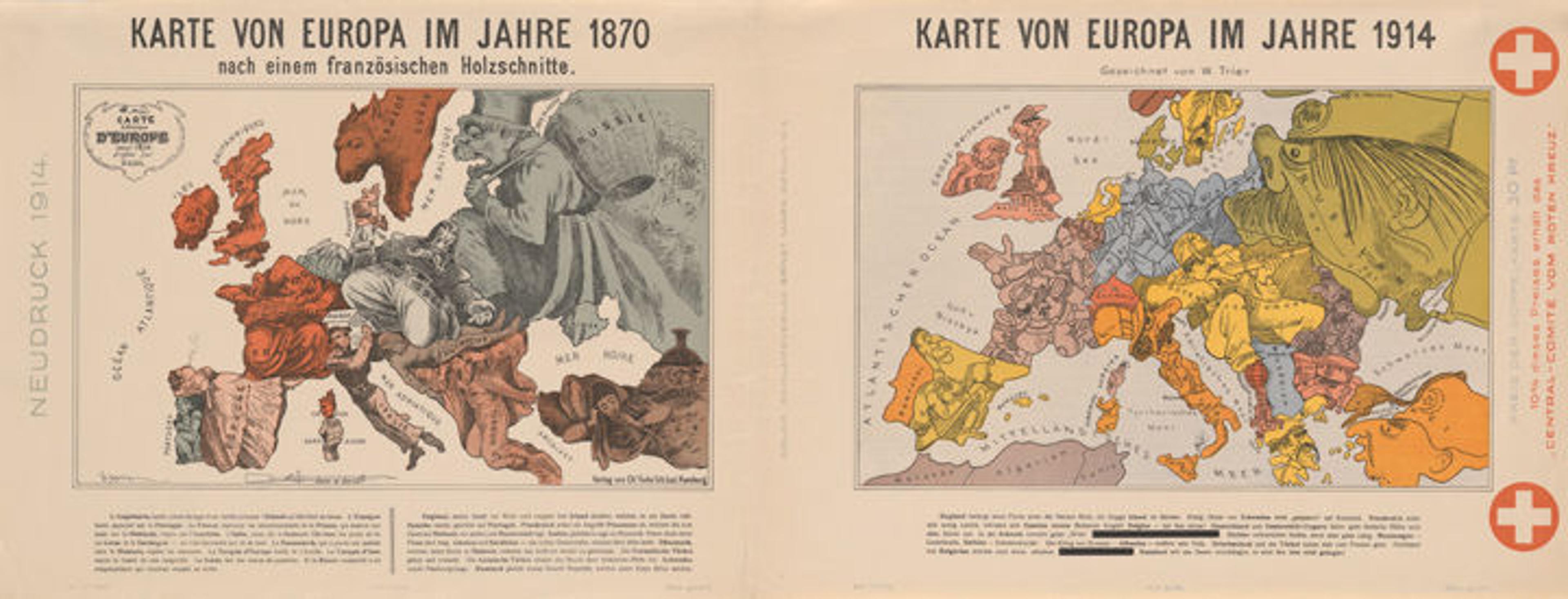

Paul Hadol (French, 1835–1875) and Walter Trier (Bohemian, 1890–1951). Map of Europe in 1870 / Map of Europe in 1914 , 1914. Commercial color lithograph, sheet: 14 5/16 x 37 3/16 in. (36.4 x 94.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. William O’D. Iselin, 1961 (61.681.9a, b)

Drawing on humor to sway public opinion, French artist Paul Hadol illustrated a satirical map of Europe at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), from which the Prussian army emerged victorious one year later. In response, German artist Walter Trier produced a map of the region at the outbreak of World War I, with each country similarly cast as a caricature. He depicts Germany and Austria-Hungary as heroic soldiers fending off surrounding nations, each represented by a negative stereotypical figure. A percentage of the proceeds from sales of his map supported the Red Cross.

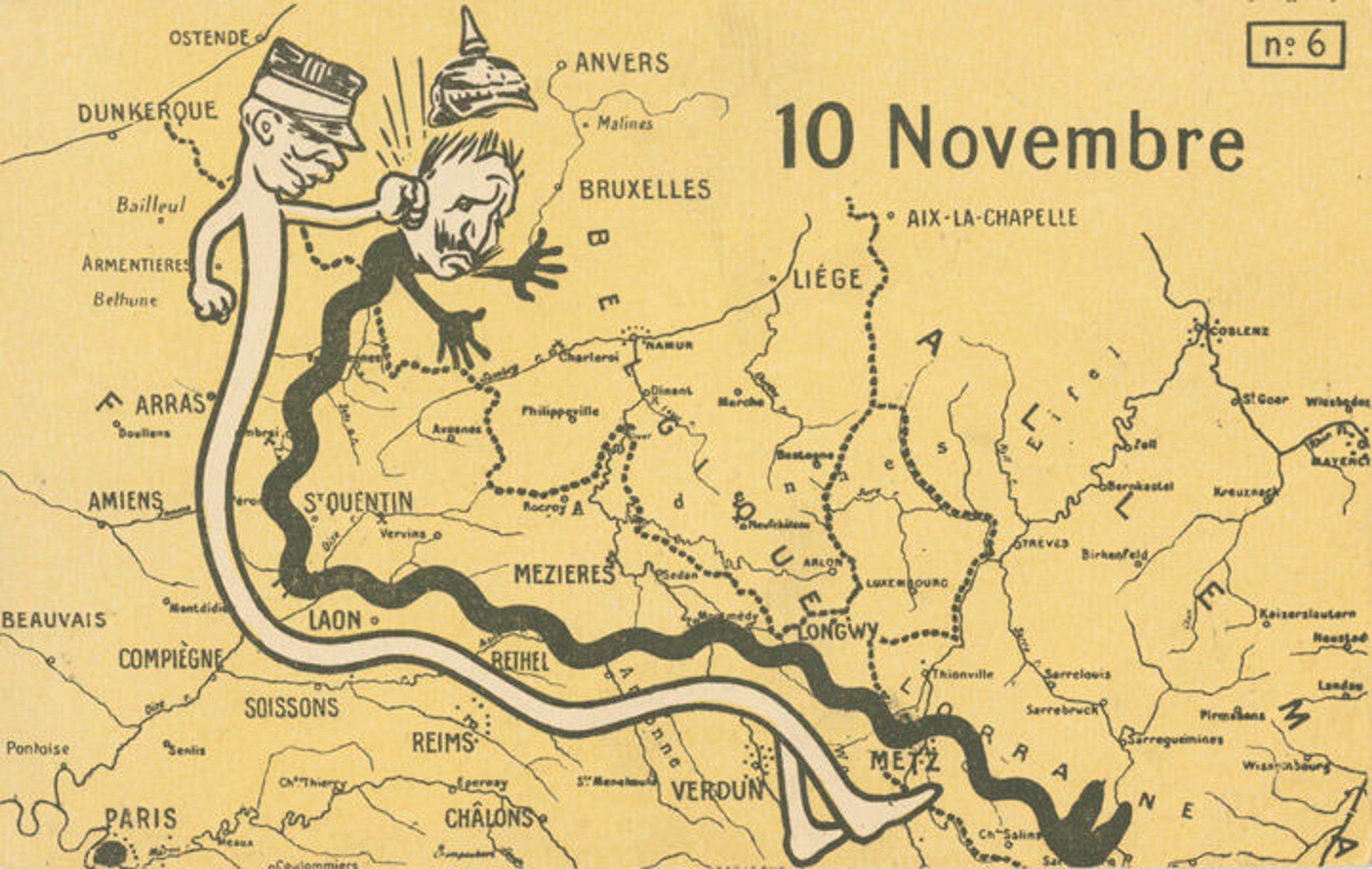

November 10 , from the series Battles of August–November, 1914 , 1914. French. Color lithographs, sheet: 4 x 6 in. (10.2 x 15.2 cm). Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Thanks to their diminutive size, postcards were another ideal tool for circulating propaganda and publicizing wartime events. Like Trier's poster, a series of postcards based on cartoons published in an English magazine uses caricature in comparing the opposing armies to a pair of "scientific wrestlers." The sequence in the spread, published on November 4, 1914, ends on October 26, at the height of the First Battle of Ypres. The postcard issuer included an additional scene (above): the November 10 Battle of Langemarck, represented as a knockout blow.

Left: Quarrels and Fights Are Unacceptable, as It Diminishes Individual Dignity , from the series Women Soldiers , ca. 1917. Color lithograph, sheet: 6 x 4 in. (15.2 x 10.2 cm). Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The provisional government in place in Russia, which controlled the country following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and prior to the ascendance of the Bolsheviks in 1917, established all-female combat units in an attempt to inspire war-weary male soldiers and demonstrate the Bolshevik model of equality among citizens. Postcards featuring members of the women's battalions were paired with moralizing captions celebrating qualities such as bravery, unity, and good hygiene.

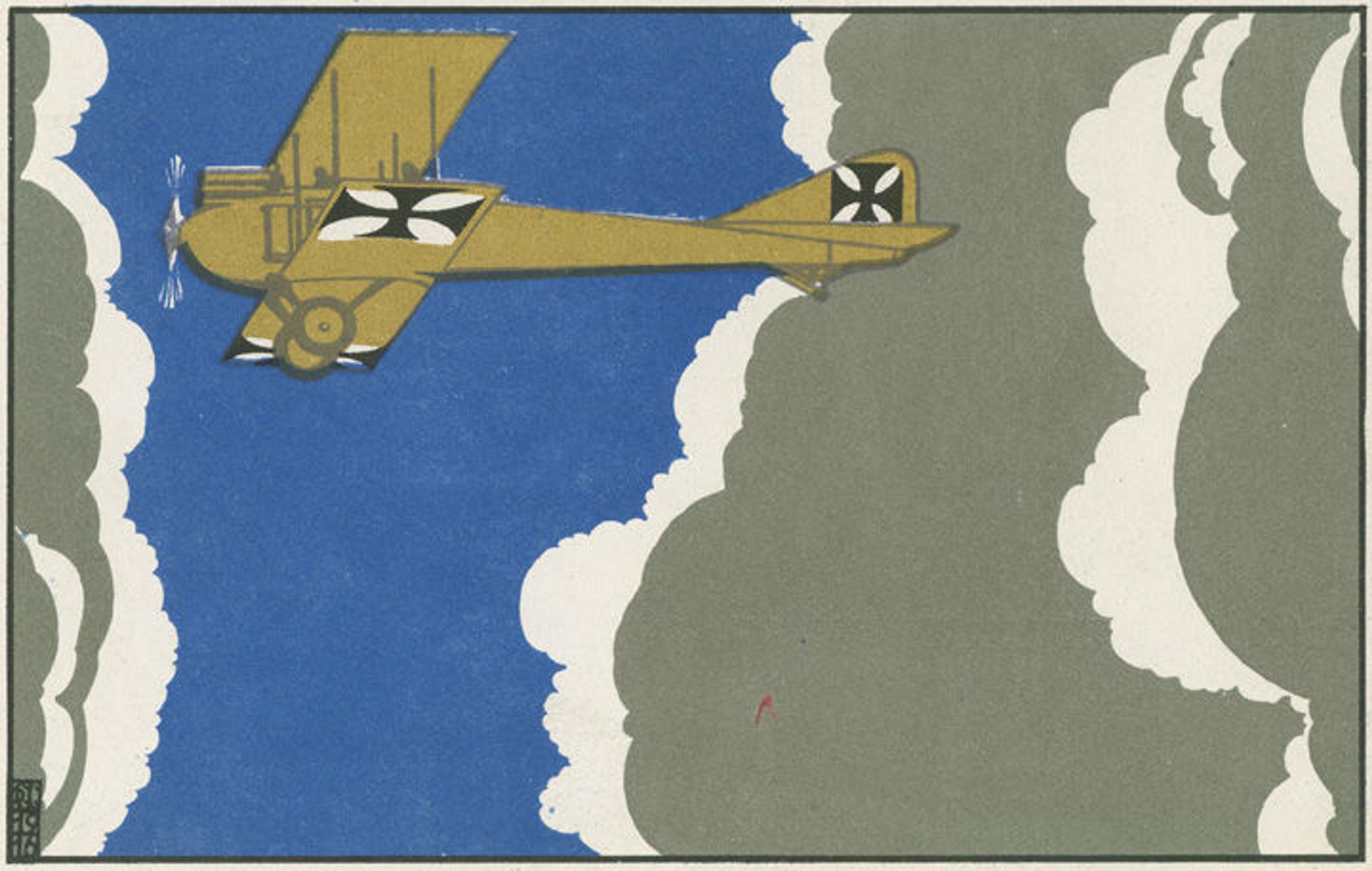

Carl Otto Czeschka (Austrian, 1878–1960). Central Power Aircraft in Flight , from the series German Armaments , 1915–16. Color lithograph, sheet: 4 x 6 in. (10.2 x 15.2 cm). Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive. Promised gift, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Other wartime postcards were considered objets d'art. Those designed by Carl Otto Czeschka, a member of the Wiener Werkstätte (a community of artists in Vienna established in 1903 devoted to restoring thoughtful craftsmanship to industrial production), extol German armaments like the aircraft pictured above. The Bahlsen cookie company issued the postcards for the German military postal service ( Feldpost ), which provided complimentary mail service to soldiers. Their streamlined compositions and color palette also appealed to collectors with a taste for modernist design.

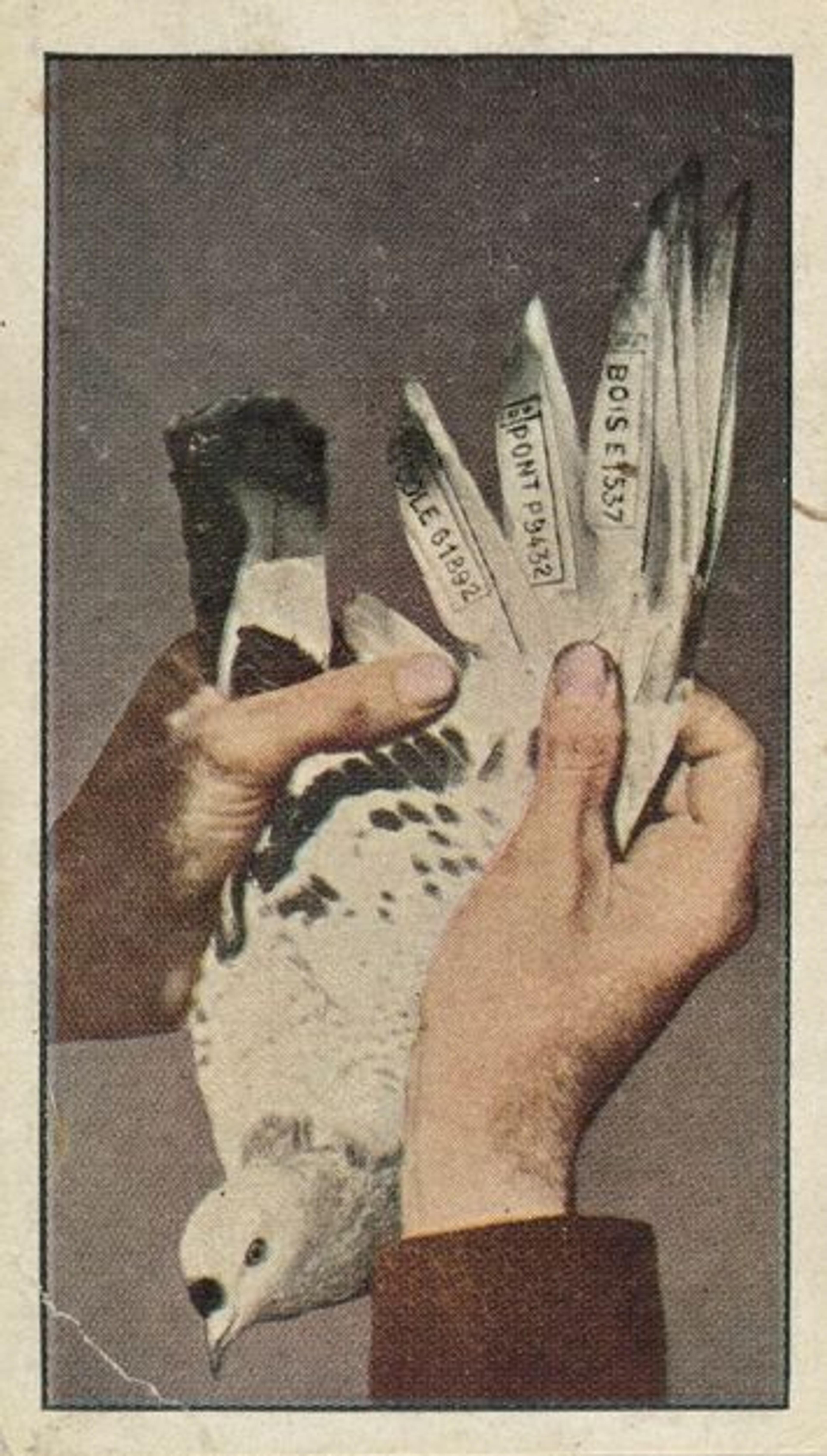

Right: Issued by American Tobacco Company; original photograph by Underwood & Underwood (American). Card No. 74, Belgian Carrier Pigeon, with Its Message in Code , from the World War I Scenes series (T121) issued by Sweet Caporal Cigarettes, 1914–15. Photolithograph, sheet: 2 5/8 x 1 9/16 in. (6.7 x 3.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (63.350.246.121.1–.250)

Trade cards—antecedents to today's business cards—were a popular means for companies to publicize their products, and often included captivating images to encourage customer loyalty. Trade cards from the Jefferson R. Burdick Collection distributed in packs of Sweet Caporal cigarettes illustrate the unprecedented convergence of modern technologies with traditional wartime tools, such as homing pigeons that deliver messages in code inscribed on their feathers. While such collectables were used for promotional purposes, they also had an educational component and aimed to spread knowledge about all facets of the war.

These posters, postcards, and trade cards may all be viewed through January 7, 2018, in the exhibition World War I and the Visual Arts ; many of these works are also discussed in the accompanying issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin .

Related Links

World War I and the Visual Arts , on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018

Read more blog posts in this exhibition's Now at The Met series .

Allison Rudnick

Associate Curator Allison Rudnick manages the Study Room for Drawings and Prints and oversees the ephemera collection. She joined the department as a research assistant in 2012 and has held positions at the print shop Harlan & Weaver and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Active in the field of contemporary printmaking, she is a frequent contributor to Art in Print and serves as treasurer for the Association of Print Scholars. She holds a BA from Connecticut College and an MPhil from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where she is a PhD candidate.

World War I: 100 Years Later

A Smithsonian magazine special report

The Posters That Sold World War I to the American Public

A vehemently isolationist nation needed enticement to join the European war effort. These advertisements were part of the campaign to do just that

Jia-Rui Cook

On July 28, 1914, World War I officially began when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. In Europe and beyond, country after country was drawn into the war by a web of alliances. It took three years, but on April 2, 1917, the U.S. entered the fray when Congress declared war on Germany.

The government didn’t have time to waste while its citizens made up their minds about joining the fight. How could ordinary Americans be convinced to participate in the war “ Over There ,” as one of the most popular songs of the era described it?

Posters—which were so well designed and illustrated that people collected and displayed them in fine art galleries—possessed both visual appeal and ease of reproduction. They could be pasted on the sides of buildings, put in the windows of homes, tacked up in workplaces, and resized to appear above cable car windows and in magazines. And they could easily be reprinted in a variety of languages.

To merge this popular form of advertising with key messages about the war, the U.S. government’s public information committee formed a Division of Pictorial Publicity in 1917. The chairman, George Creel, asked Charles Dana Gibson, one of most famous American illustrators of the period, to be his partner in the effort. Gibson, who was president of the Society of Illustrators, reached out to the country’s best illustrators and encouraged them to volunteer their creativity to the war effort.

These illustrators produced some indelible images, including one of the most iconic American images ever made: James Montgomery Flagg’s stern image of Uncle Sam pointing to the viewer above the words, “I Want You for U.S. Army.” (Flagg’s inspiration came from an image of the British Secretary of State for War , Lord Kitchener, designed by Alfred Leete.) The illustrators used advertising strategies and graphic design to engage the casual passerby and elicit emotional responses. How could you avoid the pointing finger of Uncle Sam or Lady Liberty? How could you stand by and do nothing when you saw starving children and a (fictional) attack on New York City?

“Posters sold the war,” said David H. Mihaly, the curator of graphic arts and social history at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, where 55 of these posters will go on view August 2. “These posters inspired you to enlist, to pick up the flag and support your country. They made you in some cases fear an enemy or created a fear you didn’t know you had. Nations needed to convince their citizens that this war was just, and we needed to participate and not sit and watch.” There were certainly propaganda posters before 1917, but the organization and mass distribution of World War I posters distinguished them from previous printings, Mihaly said.

Despite the passage of 100 years—as well as many wars and disillusionment about them—these posters retain their power to make you stare. Good and evil are clearly delineated. The suffering is hard to ignore. The posters tell you how to help, and the look in the eyes of Uncle Sam makes sure you do.

“ Your Country Calls!: Posters of the First World War ” will be on view at the Huntington from August 2 to November 3, 2014. Jia-Rui Cook wrote this for Zocalo Public Square .

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

The Great War

Propaganda posters, increasing awareness and encouraging support.

The United States has been at war since 2001. While there is media coverage, it does not tend to hit the headlines very often, and there is very little impact on the day–to–day life of ordinary citizens. This was not the case with World War I. Citizens of the United States were acutely aware that they were at war and their lives changed dramatically because of it.

Probably the most significant aspect in which their lives changed dealt with food. Government posters encouraged people to eat less, grow gardens and make sure that there was sufficient food for the troops. Other posters were aimed at getting people to buy savings bonds — a method of financing a war.

While posters were a positive form of propaganda during World War I, they are no longer used today.

The Digital Collections website will be partially or fully unavailable from May 12, 8pm - May 13, 2am PDT.--> The ability to search for and view database items will still be possible during that time.

- Advanced Search

War Poster Collection

Browse Collection

Sample Searches

- Dutch and German

- National security

- Women in war

- World War I

- World War II

A selection of World War I and II posters from the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections Division collections. Included are propaganda on purchasing war bonds, the importance of national security and posters from allied and axis powers.

The University of Washington Libraries Special Collections Division houses many collections of regional and historical significance, notably specialized and scarce materials, such as these examples of World War I and World War II posters. World War I, known as the Great War, stimulated the transformation of this well-established advertising tool into an effective propaganda medium for war. Often designed by the leading artists and illustrators of the time, they were cheap to produce and easy to distribute. Their direct slogans and visual imagery appealed to a variety of cultural and nationalistic themes that served to muster public support for the war campaign. Many were illustrated with compelling images of heroes, sacrifice and family values. While some encouraged the purchase of war bonds and solicited donations for non-profit organizations such as the Red Cross, others promoted patriotism and warned against aiding the enemy with careless talk. The study of this medium leads us to a greater understanding of their effectiveness as tools for propaganda, aids in the analysis of national cultural and symbolic values, and helps define ideological differences between nations at war.

About the Database

The information for the Posters Database was researched and prepared by the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections Division and Cataloging staff in 2000. Not all the posters from the collection were included in this database. The images were scanned in RGB color using a Olympus C-2000 Zoom digital camera and saved in .jpg format. Some manipulation of the images was done to present the clearest possible digital image. The scanned images were then linked with descriptive data using OCLC's CONTENTdm software. The original collection resides in the UW Libraries Special Collections Division as the Posters Collection.

Back to top

- Mission Statement

- Collections

- Imaging Services

- Student Employment

- Make Appointment

- Group Tours

- K-12 Field Trips

- Summer Camp

- Book a K-12 Visit or Kit

- Field Trips

- Classroom Activity Kits

- Professional Development

- Downloadables

- Mapmaking Contest

- News & Events

- Search The Collection

- Browse Maps

- Gallery Exhibits

- Map Commentaries

- Digital Exhibits

- Reference Books

- Digital Commons

- Ask a Librarian

- EXHIBIT SECTION |

Section Two: Propaganda Posters

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Policy |

Posters were a common form of propaganda during World War I. While propaganda is often associated with dishonesty, effective propagandists recognize the danger of lying; if even one mistruth is revealed, it throws the whole campaign into question. Primarily visual, the propaganda poster was a safe mode of delivery for emotional appeals, referencing ominous potentialities and general circumstances rather than specific events. The feelings elicited, whether righteous anger or fear or empathy, were intended to provoke the viewer to action, to purchase Liberty Bonds or to enlist in the Armed Forces. As William W. Biddle wrote in Propaganda and Education (1932), “any emotion may be ‘drained off’ into any activity by skillful manipulation.”

Propaganda posters also legitimized the war effort. By referencing atrocities committed by the Germans in Belgium and at sea, they implied that only the enemy practiced brutality in war; American soldiers were the heroes who stood between the Kaiser’s thugs and their victims. The visual representations of German soldiers often took the form of a bloodthirsty, grotesque caricature, reinforcing the demonization of the “Hun,” a derogatory nickname for a German soldier.

One of the more haunting propaganda posters of WWI, Enlist shows a woman dressed in white and cradling an infant as she drifts to the ocean floor. Rather than portray her imminent drowning as a fait accompli , the artist includes bubbles rising from her mouth to show she is still alive, compelling the viewer to see the tragedy in the midst of its unfolding. Far above her is the still-sinking wreck of a ship. The poster uses only one word, "Enlist." No additional words were necessary, because the American public of 1915 would immediately recognize the event to which the image referred. This poster was drawn by Fred Spear and produced by the Boston Committee of Public Safety only one month after the sinking of the British Passenger Liner, Lusitania .

While German U-Boats had already attacked many vessels in British waters, including two American ships, none of those sinkings resulted in the carnage of the Lusitania . The U-Boat was only 400 yards away from the ship when it fired a torpedo in its side, damaging the passenger liner so severely that it sank completely in just 18 minutes. The death total horrified the American public, with over 1,200 people killed, including 128 U.S. citizens.

Despite the public outcry, it would be almost two more years before the United States joined the war, making the message of this poster a bit premature. Its explicit call to action relies on its implicit appeal to the viewer's empathy and outrage. The depiction of the victims as a Madonna and child transforms the message into an almost religious call for justice.

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.50552/

6. Enlist Fred Spear, 1915 Library of Congress Collection URL: www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.50552

7. Remember Belgium

"Remember Belgium" was a common message of Allied propaganda during World War I. This poster asks the viewer to recall the cruelties of the German forces during the invasion and occupation of Belgium, including the slaughter of thousands of civilians, many of them children. It is estimated that by the end of the war, well over 20,000 Belgian civilians had died at the hands of the Germans. The bulk of the atrocities occurred in the first few months of the war, when invading troops burnt about 25,000 homes. The Allied press, however, was more dogged in its publicization of numerous otherwise unconfirmed incidents of sexual assault and grotesque mutilations of Belgian women and children. These series of real and alleged crimes became known as the "Rape of Belgium." Allied illustrations and posters used the figure of a brutalized woman to symbolize Belgium throughout the war.

Ellsworth Young's poster was produced after the U.S. joined the war in 1917, making it a few years out-of-date. It's disturbing imagery was nonetheless compelling, making it one of the most well-known American posters of the war. By referencing the lurid reports circulating throughout Allied press of German troops brutalizing children, this image solicits the viewer's outrage and pity. A screaming girl, silhouetted against the burning Belgian landscape, is being forcibly dragged off by a German soldier with a spiked helmet and large mustache. The girl is quite young, her size suggesting that she is only around nine or ten years old. This picture also appeared in an 1918 edition of the Ladies' Home Journal , with the caption, "Somebody's little girl. Suppose she were yours. Buy Liberty Bonds to save her."

7. Remember Belgium Ellsworth Young, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/43049

8. Remember Your First Thrill of American Liberty

The U.S. Food Administration's Education Division produced this poster several months after the country entered the war. Unlike many of its contemporaries, this poster relies on the viewer's sense of duty rather than outrage at injustices committed by the enemy. Below the image of immigrants passing the Statue of Liberty on their way to Ellis Island, the phrase "Your Duty" appears in large capitalized letters. Targeted specifically at immigrants, this poster was distributed in Yiddish and Italian as well as English. The colors used—red, white, and blue—were intended to appeal to the patriotic pride of the new citizens, who are urged to "Remember [their] First Thrill of American Liberty."

8. Remember Your First Thrill of American Liberty Sackett & Wilhelms Co., 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42932

9. That Liberty Shall Not Perish from the Earth

A bleak contrast to the previous poster (#8), this scene portrays the Statue of Liberty, not gazed on with excitement by newly arrived immigrants, but enveloped in flames. Lady Liberty's torch lies in rubble at her base, and nearby, her head is partially submerged in the waters of New York Harbor. The skyscrapers of the city are discernable in the distance, all subsumed in a massive conflagration. Silhouetted against the fiery sky are bomber planes.

The message of this poster is clear; without victory over the enemy in Europe, war could come home to America. The text below the scene implies that, should the Allied forces fail, liberty may "perish from the Earth." The viewer can help prevent this outcome simply by purchasing Liberty Bonds.

This poster is markedly similar to a set of drawings that appeared in the August 10, 1916 edition of Life Magazine . The first illustration shows the Statue of Liberty and New York City with an ominous caption, "The Unready Nation." The following illustration, titled "The Grave of Liberty," shows a post-destruction scene of the city and statue, in which the buildings are immolated ruins and only the torch of the Statue of Liberty remains, peeking out from the water.

9. That Liberty Shall Not Perish from the Earth Joseph Pennell, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42943

10. The Time Has Come to Conquer or Submit

Woodrow Wilson's round portrait in a bronze decorative border, reminiscent of currency, is the central image of this poster. Presented in large print below the portrait is Wilson's quote regarding the U.S. entrance into World War I: "The time has come to conquer or submit… For us there is but one choice. We have made it." A powerful quote, it employs the viewer's pride and sense of duty and justice.

This quote would soon be appropriated by the Silent Sentinels, a women's suffrage organization created by the famous suffragist, Alice Paul. For two and a half years, beginning before the U.S. entry into the war and ending well after the Armistice, Paul and her fellow suffragists protested in silence outside the White House. The use of silence as a form of protest was strategically effective; their arguments were not presented in the voices of women, so routinely ignored, but in the form of banners, often quoting powerful men. The rhetoric of the Allied officials typically characterized the war as a fight for freedom, for their own countries and for the smaller nations under the German Alliance, while ignoring their own violations of the right to self-determination in their imperial possessions and at home, with the lack of suffrage for the female half of their own citizenry. The banners of the Silent Sentinels called attention to the politicians' hypocrisy, a practice that elicited strong reactions from officials.

On October 20, 1917, Paul carried a banner quoting Woodrow Wilson: "The time has come to conquer or submit, for us there is but one choice. We have made it." She and her compatriots were arrested and sentenced to seven months in prison. This act was later declared unconstitutional by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, although not until the suffragists had spent their time in the Occoquan Workhouse. The women were abused throughout their incarceration, the most famous incident occurring on November 14, 1917, when the prison superintendent ordered the guards to torture the suffragist inmates. The incident became known as the "Night of Terror," with the severe beating of many women, some of whom were then suspended with their hands in chains over their heads, knocked unconscious against iron objects, and choked. One woman, Alice Cosu, suffered a heart attack; Alice Paul herself had already been rendered unable to walk from a long solitary confinement without adequate sustenance. When news of the Night of Terror reached the American public, the resulting outrage caused support for the Suffrage Movement to swell. The women were released two weeks after the Night of Terror and returned to protesting, not stopping until the Nineteenth Amendment was passed by Congress a year and a half later.

10. The Time Has Come to Conquer or Submit American Lithographic Company, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42747

11. Must Children Die and Mothers Plead in Vain

Must Children Die and Mothers Plead in Vain? depicts a mother and her two young children crouching amongst ruins. With her left hand raised upward in a pose suggesting supplication, the woman cradles one of her babies in her right arm while another child grasps at her waist. Only a few of the items in the rubble are discernible, including an empty pan and jug to the far right, a reminder of the widespread food shortages and hunger in Europe. In the darker rubble at the left of the poster, an oval shape appears behind the woman's back; although unclear, the shape could be the head of another child, possibly dead.

Like many of the posters featuring women and children, this image aims to elicits pity and, to a lesser degree, guilt from the viewer. It implies that the viewer has a responsibility to provide whatever resources they are able to contribute to bring the war to an earlier end, because the longer the conflict continues, the more women and children will suffer.

11. Must Children Die and Mothers Plead in Vain Sackett & Wilhelms Co., 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/43059

12. Clear the Way

Created by Howard Chandler Christy, a well known illustrator of the early twentieth century, this poster is one of three similar posters each featuring branches of the military. "If you want to fight, join the Marines" and "Fight or Buy War Bonds," which depicts a marching group of Army soldiers (www.oshermaps.org/map/42927), are the other two in the series. Each poster includes a beautiful woman, likely allegorical representations of liberty or America. The personification of liberty in this poster appears to be emerging from the ocean, dressed in white, possibly suggesting innocence, and wearing a laurel wreath, a classical symbol of victory in war. Behind her is an American flag and below her are members of the U.S. Navy in a sea battle, preparing to fire on an unseen enemy target. Barefoot, tattooed, heavily muscled, and universally white and blond, the men are figures of an idealized masculinity. While the explicit message of this poster is "Buy Bonds," another intention, like in Chandler's other two military posters, is to inspire the male viewer to enlist and prove himself to be one of these heroic figures.

12. Clear the Way Howard Chandler Christy, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42748

See also: Fight or Buy Bonds Howard Chandler Christy, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42927

13. Halt the Hun

This poster uses a dramatic scene of a victim, villain, and hero to capture the viewer's attention. A German soldier looms menacingly over a terrified woman on the ground. With her hair in disarray and her shirt seemingly torn, it is clear that she has already been victimized in some way. In her arms, she cradles a naked, possibly lifeless, child. The villain of the scene wears a spiked helmet and iron cross, one bloody hand holding a bayonet-fitted rifle and the other grabbing the woman's shoulder. The flames in the background give evidence to additional crimes committed by the German. The hero of the scene is an American soldier, who requires only one arm to restrain the villain. Unlike the German soldier, who is hunched and squat with a short neck and protruding jaw, the American stands tall, his chiseled features and confident bearing contrasting sharply with the appearance of the villain. Instead of a rifle, the hero wields a sword more suited to a medieval knight.

The text of the poster uses concise but strong language. "Halt" is also a German word, and "Hun" was the pejorative nickname given to the Germans during World War I. The Huns of the fourth and fifth centuries were a nomadic people in Europe and were considered uncivilized, aggressive, and barbaric. Typically shown with a spiked helmet, bayonet, and bloody hands, the figure of the Hun is prevalent in the Allied propaganda of World War I.

13. Halt the Hun Henry Raleigh, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42752

14. Beat Back the Hun with Liberty Bonds

Fred Strathmann's poster features one of the more chilling iterations of the Hun figure. Blood drips from his bayonet and hands as he peers with green greedy eyes across the ocean, presumably towards America. Mirroring the frequently used trope of the "skulking Indian" in American print culture at the time, the Hun's hunched posture and black skin can be interpreted as a racial statement. The smoldering ruins of Europe, splattered with blood from the Hun's hands, seem to imply that this could be the America's future if the "Hun" is not defeated. This poster aims to elicit fear and hatred of the enemy, and in doing so, to inspire the viewer to "Beat Back the Hun" and preserve the safety of the nation by buying Liberty Bonds.

14. Beat Back the Hun with Liberty Bonds Fred Strothman, 1917 Robert & Frank Neikirk Collection URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/42751

- To Conquer or Submit: America Views the Great War

- 1. Persuasive Maps

- 2. Propaganda Posters

- 3. Newsmaps

- 4. Military Maps

- 5. Wartime Atlases

- 6. Miscellaneous

- Basic Search

- Advanced Search

- Imagery Search

- Content Search

- Site Search

A portion of the holdings in these collections have been optimized to allow searching for elements within a given map, such as sea monsters, decorative borders, cartouche, or other imagery. This search screen will allow you to search these elements, but remember it is only searching a fraction of the collections.

During the "Great War," the lithographed poster was the harbinger, reporter, and arbiter of news, opinion, and sentiment on both the frontlines and the home front. This evocative form of public communication had the advantage of being able both to go and to remain everywhere. When the United States of America entered the conflict in April 1917, the poster as a medium of expression was not new. In the decades preceding the First World War, not only had many formal artists been drawn to the medium, but the poster, with its graphic appeal, had also become a tool of advertising, commerce, and industry. Innovations in color lithography and the development of larger and faster printing presses in the second half of the nineteenth century greatly facilitated the emergence of the modern, mass-produced poster defined by its powerful integration of emotionally evocative graphic images with brief, but direct and effective, textual messages.

Harry A. Garfield, head of the wartime United States Fuel Administration, said, "I can get the authority to write a column or a page about fuel —but I cannot make everybody or even anybody read it. But if I can get a striking drawing with or without a legend of a few lines, everyone who runs by must see it." Continuing in this vein, Joseph Pennell wrote: "That is the whole secret of the appeal of the poster—and by the poster the governments of the world have appealed to the people, who need not know how to read in order to understand, if the design is effective and explanatory." American Artists were working with and for the government of their country, working to communicate with the people at home , at work , and in the camps overseas .

As America went to war, officials in the United States, like those in Europe, quickly found the poster to be what the Publicity Bureau termed "a silent and powerful recruiter." Agencies, public and private, rushed to engage artists to create war posters. In just two years, America printed more than twenty million copies of perhaps 2,500 posters in support of the war effort, more posters than all the other belligerents combined. The purpose of this government-sponsored art was to communicate essential information rapidly and efficiently (in the era that preceded radio broadcasting). By all accounts these propaganda posters excelled in conveying the right message to their intended audience. In his Liberty Loan poster book, artist Joseph Pennell explained: "When the United States wished to make public its wants, whether of men or money, it found art—as the European countries had found—was the best medium."

The demands of war challenged American artists to create posters in aid of propaganda, recruiting, relief, and conservation with the same energy that had previously been reserved for the creation of great exhibition pictures. World War One poster artists would range from some of the best-known painters and illustrators of the day—Charles Dana Gibson, James Montgomery Flagg, and Howard Chandler Christy—to commercial artists, even students and other amateurs. The war efforts led these artists to inquire, perhaps for the first time, into the nature and possibilities of the medium. The most successful war poster artists generally came from the ranks of popular magazine and book illustrators who were trained not to simplify and eliminate but to be realistic, detailed, and, above all, evocative. James Montgomery Flagg's "Uncle Sam," originally produced as a cover for Leslie's Illustrated , became the prototype for all posters with a central figure pointing a finger at the viewer, and his "I Want You for the U. S. Army" was and remains one of the most famous posters of all time.

Flagg and the other posters artists worked for the Division of Pictorial Publicity, a branch of the Committee of Public Information. Formed just one week after America declared war on Germany, the CPI coordinated the federal government's broad-based effort to mold public opinion in support of the war. (For more on the propaganda campaign, see the Introduction to "The Home Front", especially the Mobilizing Resources and Patriotism & Politics sections.) The DPI was organized in New York under the direction of Charles Dana Gibson. Joseph Pennell served as an associate chairman of the Pictorial Division while continuing to produce designs and writing Joseph Pennell's Liberty Loan Poster , a short work describing the essential elements of the war poster. Division branches in Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco soon followed. The New York group met weekly to select designs that were forwarded to Washington, D. C. where government bureaucrats made choices based on social, economic, or cultural characteristics rather than artistic quality. The Division accepted approximately 1,500 designs, about half of which were used for posters. Various government branches, the Shipping Board, the YMCA and many other organizations used these designs. Exceptionally, the Navy had its own poster bureau directed by Henry Reuterdahl.

The appeal of the war poster was direct and typically emotional rather than intellectual. The objective of the poster was to induce instantaneous comprehension of its message and to urge the viewer to act. The goals were to attract the attention of the target audience, make a clear and specific suggestion or impression, and provide a lasting influence. The qualities of effective poster design were breadth of appeal combined with strength, simplicity, and legibility of design. A well-designed poster was instantly comprehensible, leaving nothing to be studied, deciphered, or overlooked. Many finely crafted posters have continued to attract attention and to deliver their message long after the conclusion of the campaigns for which they were designed. Theoretically, the propaganda poster was capable of communicating its message graphically, without words. A choice phrase or ringing appeal, typically of ten words or less, usually served to double its value: "Lend As They Fight" , "Teamwork Wins" , or "Halt the Hun!" . A well-chosen phrase could draw attention to desired themes such as patriotism, heroism, or determination, while proving highly memorable.

Just as American government enrolled young men to fight the war overseas, so American artists drafted familiar symbols (patriotic, heroic, and sentimental) into the service of propaganda. Gibson's and Christy's American beauties appeared in their traditional role of the girl next door in aid of recruitment or assumed the heroic drapery of Liberty or Victory to urge participation in war work or liberty loans . While numerous appeals focused on traditional female roles of sweetheart, mother and housewife, the propaganda posters show how the war opened to young women the new public roles and responsibilities . "Uncle Sam" appealed not only for U. S. Army recruits but this patriotic icon also called for home front service to the National Industrial Conservation Movement , the United States Fuel Administration , the Liberty Loan , and War Savings Stamps .

While the majority of American war posters appealed to the ideals of unity, patriotism, service, sacrifice, and the higher values of humanity, certain propaganda posters were designed to evoke negative ethnic stereotypes and nativist sentiments. Posters with slogans such as "Civilization vs. Barbarism" , "Hun or Home" , "Help Us Make It Hot for the Kaiser" , and "Help Stop This: Buy W.S.S. & Keep Him Out of America" , tended to depict the German soldier as superhuman in size, brutal and fiendish in character, and the Kaiser as undersized, trifling, and ridiculous.

However we judge the message of the posters in hindsight, there is little doubt that they succeeded in their primary purpose of eliciting a strong response from Americans of their period. Making dramatic use of emotion-laden symbols such as the American flag, the Statue of Liberty, and Uncle Sam, these posters served as a call to action when democracy was in peril and reinforced an American's pride in country and his or her innate patriotism and readiness for sacrifice. Such posters also had the psychological importance of bringing the war home to the civilians and suggesting relatively small but meaningful sacrifices on their part. In addition to the reminders of the soldiers at the front, posters showed the civilian population what they could do to aid those soldiers (enlist, buy bonds or war savings stamps) and win the war (conservation, relief). (For more on the civilian response to the war, see The Home Front/Mobilizing Resources .)

In North Carolina, as elsewhere in the United States, citizens would have seen locally produced and federally distributed posters on the streets and mounted in factories, businesses, and public buildings. Unfortunately for historians, posters were an ephemeral medium. Most of the millions of posters produced were soon pasted over or destroyed by the elements after they were read. The posters included in this site are among the relatively few copies that have survived intact and in good condition. They are a small part of the holdings of posters and other graphic materials from both world wars in the Bowman Gray Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library. This remarkable collection includes approximately 1,100 American posters from World War I, one of the largest and best preserved collections of such materials and one of the first for which online catalog records have been created for the individual posters.

As part of "North Carolinians and the Great War" project, the Academic Affairs Library has digitized one hundred U. S. World War I posters. The focus is on those that would have been widely distributed in North Carolina and would have been influential in helping to shape attitudes and behavior in support of the war and related efforts within the state. The sample chosen reflects (1) a range of governmental and private agency sponsorship of the posters, (2) an array of the artists involved in their design and production, and (3) the diversity of issues that the posters sought to address and influence (from military recruitment and war loans to the conservation of vital resources, medical aid, and refugee relief.)

The one hundred posters included in this site have been divided into broad subject categories that reflect how contemporaries might have thought of them: finance (including Liberty Loans, War Savings and Thrift Stamps), resources (involving both products that were raised or manufactured, or those that were conserved such as food and fuel), military service (from recruitment to camp life to postwar adjustment), propaganda, and war work. This classification provides a preliminary organizational scheme for viewing war posters, but viewers are invited to seek other ways of reading these complex visual documents. Propaganda posters of the First World War served as carriers of both open and covert messages about the war, the sponsoring agency, patriotism, politics, and identity. To attempt to limit these images to one scheme of classification is to underestimate and undervalue their symbolic and communicative role.

Sources: Walton Rawls, Wake up, America!: World War I and the American Poster .(New York: Abbeville Press, 1988) and Libby Chenault, Battlelines: World War I Posters from the Bowman Gray Collection . (Chapel Hill: Rare Book Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1988). For additional published sources and web sites on World War I posters, see For Further Research section.

Return to Propaganda Posters Home Page

Return to Topical Access to the Collection Home Page

- An Ordinary Man, His Extraordinary Journey

- Hours/Admission

- Nearby Dining and Lodging

- Information

- Library Collections

- Online Collections

- Photographs

- Harry S. Truman Papers

- Federal Records

- Personal Papers

- Appointment Calendar

- Audiovisual Materials Collection

- President Harry S. Truman's Cabinet

- President Harry S. Truman's White House Staff

- Researching Our Holdings

- Collection Policy and Donating Materials

- Truman Family Genealogy

- To Secure These Rights

- Freedom to Serve

- Events and Programs

- Featured programs

- Civics for All of US

- Civil Rights Teacher Workshop

- High School Trivia Contest

- Teacher Lesson Plans

- Truman Library Teacher Conference 2024

- National History Day

- Student Resources

- Truman Library Teachers Conference

- Truman Presidential Inquiries

- Student Research File

- The Truman Footlocker Project

- Truman Trivia

- The White House Decision Center

- Three Branches of Government

- Electing Our Presidents Teacher Workshop

- National History Day Workshops from the National Archives

- Research grants

- Truman Library History

- Contact Staff

- Volunteer Program

- Internships

- Educational Resources

American Propaganda in the Great War

- Students will analyze American propaganda posters from World War 1, the Great War.

- They will view examples of war American war propaganda, & determine what these posters are conveying.

Students will learn that propaganda is information, both biased & misleading to promote or publicize a certain political cause or point of view. They will then analyze examples of American propaganda.

- Examine & analyze WW1 era American propaganda posters to determine the poster’s message, audience it is supposed to reach & its effectiveness.

Massachusetts Content Standards:

- # 35: Analyze causes & course of America in WW1

- # 36: Analyze the rationale of America’s entering the conflict

- # 37: Analyze the role played by the USA in support of the Allied Powers

The student may view examples of propaganda posters on various websites, including the following:

- www.theworldwar.org

- www.ww1propaganda.com

- www.warhistoryonline.com

- www.smithosnianmag.com

The student will inspect & analyze three (#3) American WW1 posters: One should be geared to American men, calling on them to enlist in the war effort. A second poster should be geared toward the American people in general, illustrating the evilness of the ‘Hun” enemy. The third poster should reach out to the American people living on the “Home Front”. This one would ask all Americans to volunteer their time, donate to the war effort in any number of ways, or to conserve food/fuel, etc.

For each poster the student will:

- Identify which group of people the poster is aimed

- Explain in their own words what they believe the poster in attempting to convey to the reader

- C) Decide if the poster effectively reaches the reader> In other words, is the poster convincing? Why or why not?

Important! The student must include a picture/print of each poster, either attaching their evaluation of each poster to on the print/picture, or by writing their evaluation on the picture

- The exercise (homework grade) will be based on 40 possible points.

- Students will be graded on the originality of their poster choice (in other words, try to find one that another student is NOT also using) on a number basis from 5 to 10, with 10 being the highest grade.

- Student will also be graded on satisfactorily identifying the poster’s audience, explaining the meaning of the poster, as well as deciding the effectiveness of each poster. Each of these three will be graded on the same number system as above, 5 to 10.

Donate Today

Propaganda posters

Propaganda is a form of communication that promotes a particular perspective or agenda by using text and images to provoke an emotional response and influence behaviour.

Can you think of some modern examples of propaganda?

1. During the First World War, propaganda was used around the world for fundraising, to build hatred of the enemy, and to encourage enlistment. Posters were an ideal method of communicating this propaganda, as they could be printed and distributed quickly in large quantities.

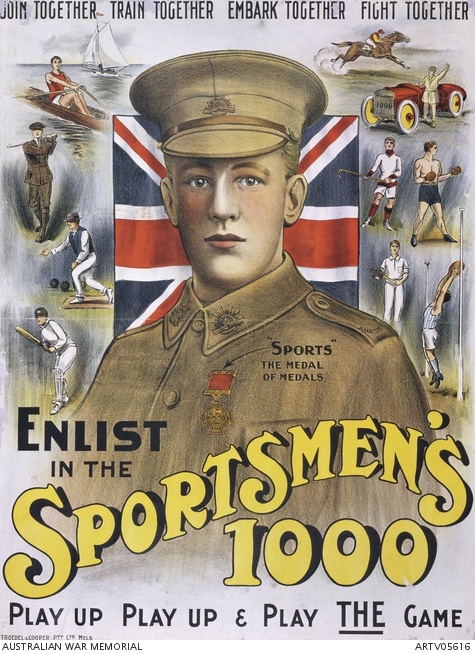

Here are two examples of Australian propaganda posters, which aimed to encourage enlistment by promoting a sense of comradery and duty:

Accession Number: ARTV05616

Sportsmens’ Recruiting Committee, Troedel and Cooper Pty. Ltd, Enlist in the Sportsmens’ 1000 , 1917, chromolithograph on paper, 98.7 x 73.2 cm

Accession Number: ARTV00141

David Souter, Win the War League, William Brooks and Co. Ltd, It is nice in the surf, but what about the men in the trenches? , 1915, lithograph printed in colour on paper, 76.2 x 51.4 cm

a. What messages are the posters presenting?

b. Who are those posters targeting? Who are they not targeting, and why?

c.What do these posters tell us about how the typical Australian man was percieved during the early 1900s?

d. Do you think these posters would have influenced people like Augusta Enberg , the Christensen family , or Peter Rados ? Why or why not?

2. The following propaganda posters also encouraged enlistment, but did this by building fear of the enemy.

Accession Number: ARTV00078

Norman Lindsay, Commonwealth Government of Australia Syd. Day, The Printer Ltd, ?, 1918, chromolithograph on paper, 99 x 74.4 cm

Accession Number: ARTV06030

B.E. Pike, VAP Service, Must it come to this? , 1914 – 1918, chromolithograph on paper, 57.7 x 46 cm

Accession Number: ARTV00079

Norman Lindsay, Commonwealth Government of Australia, W.E. Smith Ltd, Will you fight now or wait for this? , 1918, chromolithograph on paper, 98.3 x 74.6 cm

a. How is the enemy depicted, and what message is being presented?

b. How does the artist use text and images to convey this message?

c. What mood is being created?

d. What design elements (colour, typography, shape, space, and scale) have contributed to the mood of this poster?

e. Do you think the artist has been successful in getting their messages across? Why or why not?

f. How do you think these posters might have made Australians with German heritage feel?

3. Below are German propaganda posters that also focus on the notion of the enemy.

Accession Number: ARTV10343

Claus Berthold, Das Duetsche Scharfe Schwert [The German sharp sword], 1917, lithograph on paper, 90.8 x 58 cm

Accession Number: ARTV10346

Leopold von Kalckreuth, Hurrah, Alle Neune [Hurrah, all nine!], 1918, lithograph printed in colour, 75.4 x 57 cm

Accession Number: ARTV05099

Egon Tschirch Was England Will! [What England will do!...], 1918, lithograph printed in colour, 93 x 67cm

a. Translate the text on these posters using Google Translate . You can also find out more about the posters by searching with the image number (such as ARTV10346) at www.awm.gov.au

b. Compare and contrast these three German posters, to the three Australian posters that also focus on the enemy. Identify similarities and differences relating to message, tone, and the representation of the opposing side. Which posters do you think have the greatest impact? Why?

4. Design your own First World War propaganda poster. You might like to consider:

a. Will you use an Australian, British, German, French or other perspective?

b. What are you trying to get the viewer to think or feel?

c. Will your message be positive or negative?

d. What colours, font, size, and style will you use to get your message across?

For more images and activities relating to propaganda posters from the First and Second World Wars, view the Hearts and Minds education kit.

Last updated: 19 January 2021

Please enter at least 3 characters

World War II Propaganda Posters

Created by everyone from Norman Rockwell to the Stetson Hat Company, World War II propaganda posters played a crucial role in motivating Americans.

This article appears in: October 2002

By Eric H. Roth

Military posters played a crucial role in motivating Americans to do their best and make sacrifices—of all kinds—during World War II. The War Department, Red Cross, General Electric, Stetson Hat Company, and dozens of other organizations created thousands of patriotic posters to mobilize public support. Poignant, colorful images on paper were created and distributed to

build support for avenging Pearl Harbor, protecting American families, selling war bonds, conserving fuel, increasing factory production, promoting democratic ideals, growing vegetables, expanding the workforce, and keeping secrets.

The propaganda war, before television and the Internet, looked—and maybe worked—best on posters. Wartime posters, often printed in runs of 10,000, were designed to be used once, understood in 20 seconds, displayed for a few months, and thrown away. The few remaining posters, often created by skilled artists and illustrators, have become historical artifacts. Museums, scholars, collectors, veterans—and, increasingly, baby boomers—are celebrating these wartime images for their sociological, aesthetic, and historical value. World War II posters have become hot commodities and very collectible items.

“The Posters That Won the War,” a cyber exhibition at www. posterny. com by the Chisholm-Larsson Gallery, tells the story and highlights 50 original WWII posters: “The production, recruiting, and War Bond posters of WWII were ‘America’s weapons on the wall.’ Millions of posters of hundreds of unique designs cascaded off the presses and onto the American landscape, raising hopes in the dark days after Pearl Harbor and convincing folks on the homefront that their efforts were the key to victory. Today, the relatively few posters that remain are a colorful, nostalgic, and highly collectible snapshot of America at war.”

Robert Chisholm, the owner of Chisholm-Larsson Gallery in New York City, counts 627 different original WWII posters in his collection of 24,000-plus posters. “Whatever your budget, you can find a WWII poster,” says Chisholm. “Ninety percent are $400 or less.”

The gold standard for collectors’ WWII vintage posters, however, remains the Meehan Military Posters catalog. “The only organization in the world,” according to the company’s literature, “devoted to providing original, vintage posters of the two World Wars and Spanish Civil War to collectors, museums, decorators, and investors.” Meehan Military Posters divides WWII posters into nine distinct categories: pilots/planes, recruitment, conservation, espionage, nurses, foreign aid, war production, morale, and foreign on its searchable Web site.

Each color catalog, published twice a year, contains thumbnail-sized reproductions of hundreds of original military posters from “nearly all combatants in both World Wars.” A concise description gives the background of each poster, noting the artist, year of publication, size, condition, and price. The catalog costs $15, but many collectors and dealers consider it an essential investment. “His prices are very good, very fair,” observes a West Coast competitor, Burt Blum, owner of the Trading Post in Santa Monica and a lifelong dealer in vintage magazines and posters.

Fair should not be confused with cheap. “Today an expensive WWII poster can command as much as $4,000 or $5,000,” declares Meehan. “A German poster designed and drawn by the great German poster artist Ludwig Hohlwein could easily be in that range.” Meehan Catalog #36 features many rare, expensive, and fascinating posters. A pair designed by Melbourne Brindle graces the front and back covers. The first haunting image shows a sinking ship, printed by Stetson Hat Company. It warns: “Loose Talk Can Cost Lives! … Keep it under your STETSON.” The second dramatic poster of a sunken Merchant Marine ship beneath a German U-Boat, with the words “Careless talk did this … Keep it under Your Stetson,” sells for $2,750.

The pricey Stetson poster illuminates a common theme of many World War II posters: the dangers of espionage and careless talk. “Silence—means security. Be careful what you say or write,” by illustrator Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer in 1945 shows a night-patrol infantryman walking somewhere in the Pacific. Meehan sells it for $325. Other military posters, more available and by less well-known artists, such as the 1943 “This Man May Die If You Talk Too Much,” featuring a handsome sailor looking through a porthole, and the 1944 “We Caught Hell!—someone must have talked” sell for $145 in the poster catalog. These poignant posters place clear responsibility for the safety of sailors and soldiers on the silence of civilians and fellow servicemen.

Almost the entire “Loose lips sink ships” poster series has become quite collectible. An excellent example, according to veteran poster dealer Gail Chisholm (Robert’s sister, neighbor, and friendly rival poster gallery owner), shows a hissing snake surrounded by the words “Less Dangerous Than Careless Talk”—she sells it for $330. The easy-to-use Chisholm Gallery Web site includes a wide selection of World War II posters. “There are also a lot of great and amusing posters against careless talk,” such as “Keep Mum, She’s Not So Dumb,” observes Robert Chisholm.

“Powers of Persuasion: Poster Art of World War II,” a popular exhibit at the National Archives Building in Washington DC from May 1994 to February 1995, emphasized the two psychological approaches used to motivate Americans: pride and fear. “Words are ammunition,” said a Government Information Manual issued by the Office of War Information in the exhibit. “Each word an American utters either helps or hurts the war effort. He must stop rumors. He must challenge the cynic and the appeaser. He must not speak recklessly. He must remember that the enemy is listening.” An online exhibit culled from the museum show features 33 posters, one sound file, and some background historical information.

Across the country at an outdoor flea market in Santa Monica, dealer Garrison Dover has found WWII military posters to be a hot topic. “When I get WWII posters, they tend to move fast,” said Dover, the owner of Pacific Posters International. “Sometimes a guy will ask if we have any WWII posters. You show him two or three, and he buys them all. Somebody who collects WWII posters will buy anything in stock … under the right circumstances.”

Price might be one of those circumstances. “Wartime posters go for $20 to $2,000,” continues Dover, with most posters going for around $200. “Anything selling for more than $2,000 is a one of a kind.” The significant price tag for those two Stetson Hat posters also reflects a general principle in collecting—the more unusual the item, the higher the price. “Most posters were government issues, but there are some from General Electric, General Motors, and other companies,” notes Robert Chisholm. “They are more collectible because they had a smaller circulation.”

“We are currently advertising posters printed in a series for the Kroger Baking Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, which they placed in their grocery store windows during the war,” says Meehan. “They are now selling for several thousand dollars each. Privately printed posters like these had very small print runs compared to government posters.” Yet some dealers consider it a mistake to confuse the initial print run with the number of surviving copies.

“People always want to know how many posters were printed, and you don’t know,” confesses Gail Chisholm. “The number printed has nothing to do with the number surviving. It wasn’t a successful (advertising) campaign if it wasn’t on the street.” Location can also be a factor in the perception of rarity and poster prices. Dover sells original vintage posters at antique malls, flea markets, and vintage poster shows, and only opens his Santa Barbara gallery for private appointments. His web site also leads to some sales.

Sometimes rarity and historical importance are not the most critical factors. Occasionally even relatively rare posters can be bought for under $250—especially if the image is something that few people would want to look at in their home. A somber 1942 poster of a dead sailor in the surf above the words “A Careless Word … A Needless Loss” is listed for $235 in the Meehan Military Posters Catalog #36.

A few posters have become celebrated American icons. James Montgomery Flagg’s 1941 version of Uncle Sam pointing, with the caption “I Want You for the U.S. Army,” consistently sells for well over $1,000. The Meehan Catalog lists the price as $1,500. This classic WWII poster, based on the infamous World War I poster, deliberately evokes the patriotic imagery from the “war to end all wars.”

Most WWII posters, however, look quite different from WWI propaganda posters. “WWI posters were primarily designed by illustrators who volunteered their efforts,” says Sarah Stocking, president of the Independent Vintage Poster Dealers Association and owner of Sarah Stocking Fine Vintage Posters. “They mostly appeal to patriotism.” Stocking specializes in commercial European posters from the 1920s and 1930s.

Gail Chisholm makes a related point. “World War I posters are from a more innocent and naive society,” she says. “Obviously, it’s called the Great War. It was enough to have a pretty woman with a furling flag to convince young men to enlist and risk their lives.”

“Perhaps more importantly,” concludes Stocking, “WWI posters are not brutal.” Stocking carries posters on WWI, WWII, the Spanish Civil War, and propaganda. She “prefers” WWI posters because there is less text.

By contrast, American posters from WWII were often realistic, intense, and evocative of both positive and negative emotions.

“WWII posters were often made about fear and the enemy,” says Stocking. “The world had really changed in 20 years, and had gotten smaller because the government was worried about spying.” Radio broadcasts, airplanes, and increased tourism brought Europe “closer” to the United States. “World War II posters are much more aggressive,” concurs Gail Chisholm. The widely distributed poster showing a bomb, labeled “War Production,” targeted at the Rising Sun and Nazi swastika is an example. “Some also have ugly caricatures of Japanese and Germans—but especially Japanese.” Institutional collectors tend to be the major purchasers of the more controversial and/or foreign posters. American propaganda posters, however, appear politically correct in comparison to the vicious images in Axis propaganda posters. “I have a phenomenal Italian one—even away from the perspective of the war,” says Gail Chisholm. “It has an ugly, leering, black American soldier pulling down a Venus De Milo sculpture.” The harsh image, designed to inflame Italian fears about an American invasion, emphasizes racial hatreds. “Some patrons have gotten very upset by the image,” she says. She considers the disturbing image “a peek into history.” The controversial Italian poster, designed by Gino Boccasile in 1944, brings up another aspect of collecting historical posters. “Taking things out of context changes your perception,” observes Gail Chisholm. “You can have different interpretations. At the time, everybody understood a poster’s context, but now it is less clear.”

A few American posters, among the most sought after by institutional collectors, attempted to build relations between racial groups. A widely distributed poster, “United We Win,” shows steelworkers, a black man and a white man, working together under a giant American flag. “Those posters tend to be quite valuable,” says Gail Chisholm.