- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, a systematic review of factors that influence youths career choices—the role of culture.

- 1 College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 2 College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 3 College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

Good career planning leads to life fulfillment however; cultural heritage can conflict with youths' personal interests. This systematic review examined existing literature on factors that influence youths' career choices in both collectivist and individualistic cultural settings from around the globe with the aim of identifying knowledge gaps and providing direction for future research. A systematic review strategy using the Joana Briggs Institute's format was conducted. The ERIC, PsychInfo, Scopus, and Informit Platform databases were searched for articles published between January 1997 and May 2018. A total of 30 articles were included in the review, findings revealed that youth from collectivist cultures were mainly influenced by family expectations, whereby higher career congruence with parents increased career confidence and self-efficacy. Personal interest was highlighted as the major factor that influenced career choice in individualistic settings, and the youth were more independent in their career decision making. Bicultural youth who were more acculturated to their host countries were more intrinsically motivated in their career decision making. Further research is imperative to guide the understanding of parental influence and diversity, particularly for bicultural youths' career prospects and their ability to use the resources available in their new environments to attain meaningful future career goals.

Introduction

Career choice is a significant issue in the developmental live of youths because it is reported to be associated with positive as well as harmful psychological, physical and socio-economic inequalities that persist well beyond the youthful age into an individual's adult life ( Robertson, 2014 ; Bubić and Ivanišević, 2016 ). The term “youth” is described by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) as a more fluid category than a fixed age group and it refers to young people within the period of transitioning from the dependence of childhood to adulthood independence and awareness of their interdependence as members of a community ( UNESCO, 2017 ).

The complexity of career decision-making increases as age increases ( Gati and Saka, 2001 ). Younger children are more likely to offer answers about their ideal career which may represent their envisioned utopia and phenomenal perceptions about what they want to do when they grow up ( Howard and Walsh, 2011 ). As children get older, they are more likely to describe their career choice as a dynamic interplay of their developmental stages and the prevailing environmental circumstances ( Howard and Walsh, 2011 ). Youth career decision-making is required to go through a process of understanding by defining what they want to do and exploring a variety of career options with the aid of guidance and planning ( Porfeli and Lee, 2012 ). Proper handling of the process affirms individual identity and fosters wellbeing, job satisfaction and stability ( Kunnen, 2013 ).

Many theoretical models have been proposed to explain the process of career development and decision-making, one of which is the Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) by Lent et al. (1994) . According to the SCCT, career development behaviors are affected by three social cognitive processes - self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations and career goals and intentions which interplay with ethnicity, culture, gender, socio-economic status, social support, and any perceived barriers to shape a person's educational and career trajectories ( Lent et al., 2000 ; Blanco, 2011 ). This emphasizes the complex interplay between the personal aspirations of youths in their career choices and decision-making and the external influences which act upon them. Carpenter and Foster (1977) postulated that the earlier experiences and influences which individuals are exposed to form the bedrock of how they conceive their career aspirations ( Carpenter and Foster, 1977 ). These authors' assertion lends support to the tenets of SCCT and they have developed a three-dimensional framework to classify the factors that influence career choice. Carpenter and Foster proposed that all career-influencing factors derive from either intrinsic, extrinsic, or interpersonal dimensions. They referred to the intrinsic dimension as a set of interests related to a profession and its role in society. Extrinsic refers to the desire for social recognition and security meanwhile the interpersonal dimension is connected to the influence of others such as family, friends, and teachers ( Carpenter and Foster, 1977 ).

Further exploration by other researchers reveal that youth who are motivated by intrinsic factors are driven by their interests in certain professions, and employments that are personally satisfying ( Gokuladas, 2010 ; Kunnen, 2013 ). Therefore, intrinsic factors relate to decisions emanating from self, and the actions that follow are stimulated by interest, enjoyment, curiosity or pleasure and they include personality traits, job satisfaction, advancement in career, and learning experiences ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ; Kunnen, 2013 ; Nyamwange, 2016 ). Extrinsic factors revolve around external regulations and the benefits associated with certain occupations ( Shoffner et al., 2015 ). Prestigious occupations, availability of jobs and well-paying employments have also been reported to motivate youth career decision-making ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ). Consequently, extrinsically motivated youth may choose their career based on the fringe benefits associated with a particular profession such as financial remuneration, job security, job accessibility, and satisfaction ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ; Edwards and Quinter, 2011 ; Bakar et al., 2014 ). Interpersonal factors encompass the activities of agents of socialization in one's life and these include the influence of family members, teachers/educators, peers, and societal responsibilities ( Gokuladas, 2010 ; Bossman, 2014 ; Wu et al., 2015 ). Beynon et al. reported that Chinese-Canadian students' focus in selecting a career was to bring honor to the family ( Beynon et al., 1998 ). Students who are influenced by interpersonal factors highly value the opinions of family members and significant others; they therefore consult with and depend on these people and are willing to compromise their personal interest ( Guan et al., 2015 ).

Studies have shown that cultural values have an impact on the factors that influence the career choices of youths ( Mau, 2000 ; Caldera et al., 2003 ; Wambu et al., 2017 ; Hui and Lent, 2018 ; Tao et al., 2018 ). Culture is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes one group of people from another ( Hofstede, 2001 , p.9) ( Hofstede, 2001 ). Hofstede (1980) seminal work on culture dimensions identified four major cultural dimensions in his forty-country comparative research ( Hofstede, 1980 ). The first dimension is known as “individualism-collectivism.” In individualistic cultures, an individual is perceived as an “independent entity,” whilst in collectivistic cultures he/she is perceived as an “interdependent entity.” That said, decision-making in individualistic cultures are based on individuals ‘own wishes and desires, whilst in collectivistic cultures, decisions are made jointly with the “in-group” (such as family, significant others and peers), and the primary objective is to optimize the group's benefit. The second dimension is power distance. In high power distant cultures; power inequality in society and its organizations exist and is accepted. The third dimension - uncertainty avoidance denotes the extent to which uncertainty and ambiguity is tolerated in society. In high uncertainty avoidant cultures, it is less tolerated, whereas in low uncertainty avoidant cultures it is more tolerated. Lastly, masculinity and femininity dimension deals with the prevailing values and priorities. In masculine cultures, achievement and accumulation of wealth is valued and strongly encouraged; in feminine cultures, maintaining good interpersonal relationships is the priority.

In his later work on “Cultural Dimension Scores,” Hofstede suggested that countries' score on power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence depicts whether they are collectivist inclined or individualistic-oriented ( Hofstede, 2011 ). Countries that espoused collectivist values may score low and countries that are entrenched in individualistic values may score high on the above-mentioned six cultural dimension score models ( Hofstede, 1980 , 2001 , 2011 ). This model aids the characterization of countries into either individualistic or collectivist cultural settings.

On this basis, western countries like Australia, United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA) have been shown to align with individualism and such cultures are oriented around independence, self-reliance, freedom and individual autonomy; while African and Asian nations align more closely with collectivism in which people identify with societal interdependence and communal benefits ( Hofstede, 1980 ; Sinha, 2014 ). Research indicates that basing cultures on individualistic versus collectivist dimensions may explain the classical differences in career decision-making among youths ( Mau, 2004 ; Amit and Gati, 2013 ; Sinha, 2014 ). The normative practice in individualistic societies is for the youth to be encouraged to choose their own careers and develop competency in establishing a career path for themselves, while youths from collectivist societies may be required to conform to familial and societal standards and they are often expected to follow a pre-determined career track ( Oettingen and Zosuls, 2006 ).

The interaction between individualistic and collectivist cultures has increased in frequency over the last 20 years due to global migration. Given that different standards are prescribed for the youths' career selection from the two cultures (collectivist—relatedness, and individualistic—autonomy), making a personal career decision could be quite daunting in situations where migrant families have moved from their heritage cultures into a host country. Friction may arise between the adapting youths and their often traditionally focused and opinionated parents as the families resettle in the host countries.

According to a report by the United Nations (UN), the world counted 173–258 million international migrants from 2000 to 2017, representing 3.4 percent of the global population. Migration is defined by the International Organisation of Migration (IOM) as the movement of a person or a group of persons, either across an international border, or within a state ( IOM, 2018 ). In this era of mass migration, migrant students who accompanied their parents to another country and are still discerning their career pathways could be exposed to the unfamiliar cultural values in general and the school/educational system in particular ( Zhang et al., 2014 ). On this note, migrant students might face a daunting task in negotiating their career needs both within host countries' school systems and perhaps within their own family setups. These migrant youth undoubtedly face uncertainties and complexities as career decision-making trajectory could be different in their heritage cultures compared to the prevailing status quo of the host country's culture ( Sawitri and Creed, 2017 ; Tao et al., 2018 ). As youth plan and make career decisions, in the face of both expected and unexpected interests, goals, expectations, personal experiences as well as obligations and responsibilities, cultural undercurrents underpin what the youth can do, and how they are required to think. Some studies have examined cross-cultural variations in factors influencing the career choice of youth from both similar and dissimilar cultural settings ( Mau, 2000 ; Lee, 2001 ; Fan et al., 2012 , 2014 ; Tao et al., 2018 ). However, there may be large differences between different migrant populations.

Given the influence of cultural heritage on career choice and with the increasing numbers of transitions between cultures, it is important to examine the scope and range of research activities available in the area of youths' career choice, particularly in relation to how movements across cultures affect the youth in their career decision making. To the best of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive review of existing literature available in this area. Using the three-dimensional framework proposed by Carpenter and Foster (1977) , this systematic review aims to examine the factors influencing youths' career choices, with particular reference to cultural impact. It will also identify any gaps in the existing literature and make recommendations that will help guide future research and aid policy makers and educational counselors in developing adequately equipped and well-integrated career choice support systems that will foster a more effective workforce.

Literature Search

A systematic review strategy was devised and the literature search was conducted using the Joana Briggs Institute's (JBI) format. The search was conducted between December 2016 and May 2018, utilizing James Cook University's subscription to access the following databases: Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), PsycINFO, Scopus and Informit. The subject and keyword searches were conducted in three parts.

1. Career and its cognate terms:

“Career development” OR “Career decision” OR “career choice” OR “Career choices” OR “Career planning” OR “Career guidance” OR Career OR Careers OR “Career advancement” OR “Career exploration” OR Vocation OR Vocations OR Vocational OR “Occupational aspiration” OR Job OR Jobs OR Occupations OR Occupation OR Occupational” AND

2. Youth and its cognate terms:

“Youth OR Youths” OR “Young adults” OR adolescent* OR teenage* OR student” AND

3. Factors and variables:

“Intrinsic OR Extrinsic OR Interpersonal OR Individualistic OR Collectivist OR Culture OR Cultures OR Cultural OR “Cross Cultural.”

The Boolean operators (OR/AND) and search filters were applied to obtain more focused results. The articles included in the final search were peer-reviewed and the references of publications sourced from these searches were hand searched to obtain additional abstracts. Searches of reference and citation lists commenced in December 2016, repeated in March, July and November 2017 and finally May 2018 to identify and include any new, relevant articles.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Only peer-reviewed articles published in English within the last 20 years (1997-2018) and with full text available were included. Studies included in the final analysis were original research articles that focused on career choices of youth from all cultures including migrant youth who are also known as bicultural (those who accompanied their parents to another country). The rationale for using the cultural concepts of collectivist and individualistic cultural settings was inspired by Hofstede's Cultural Dimensional Scores Model ( Hofstede, 2011 ). Abstracts were excluded if they focused on students below secondary school level and those already in the workforce as the study mainly focused on youth discerning their career choices and not those already in the workforce.

Data Extraction

Two of the researchers (PAT and BMA) independently assessed data for extraction, using coding sheets. Study variables compared were author and year of publication, country and continent of participant enrolment, cultural setting, study design, participant numbers, and educational level, factors influencing career choice and major outcomes. Data were crosschecked in a consensus meeting and discrepancies resolved through discussion and mutual agreement between the two reviewers. The third and fourth authors (T.I.E and D.L) were available to adjudicate if required.

Quality of Methods Assessment

In this study, two reviewers (PAT and TIE) ascertained the quality and validity of the articles using JBI Critical Appraisal (CA) tools for qualitative and cross-sectional studies ( Aromataris and Munn, 2017 ). In any event of disagreement, a third reviewer (BMA) interceded to make a judgement. Both JBI CA tools assess the methodological quality of the included studies to derive a score ranging from 0 (low quality) to 8 or 10 (high quality). Using these tools, studies with a total score between 0 and 3 were deemed of low quality, studies with a score between 4 and 6 were classed as of moderate quality and studies with scores from 7 were deemed to be of high quality (sound methodology).

Study Selection

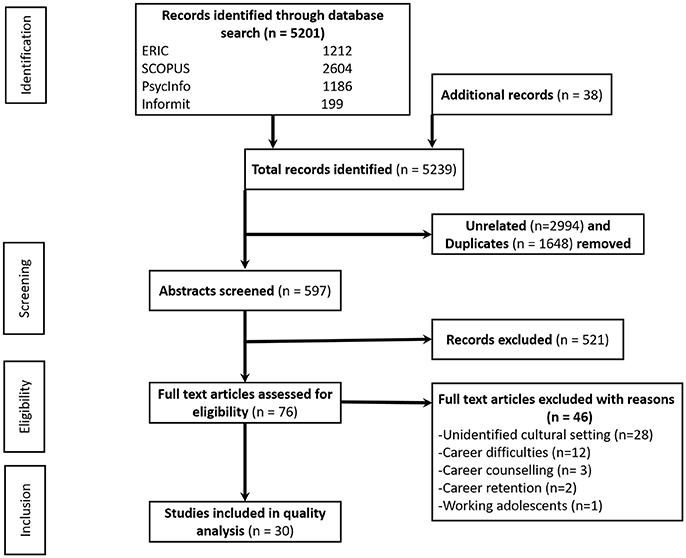

Articles retrieved from the initial database search totaled 5,201. An additional 38 articles were retrieved from direct journal search by bibliographic search. A total of 597 records remained after duplicates and unrelated articles were removed. Of this number, 521 were excluded after abstract review mainly for not meeting the inclusion criteria, leaving 76 full text articles for eligibility check. A further 46 were excluded because they focused on career difficulties, counseling, retention, working adolescents, or the cultural setting was not stated. Applying this screening process resulted in 30 studies for inclusion in the qualitative review synthesis (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Search strategy. The figure shows the search strategy including databases assessed for this study.

Study Characteristics

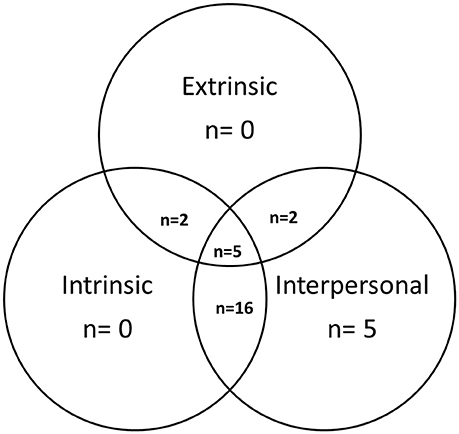

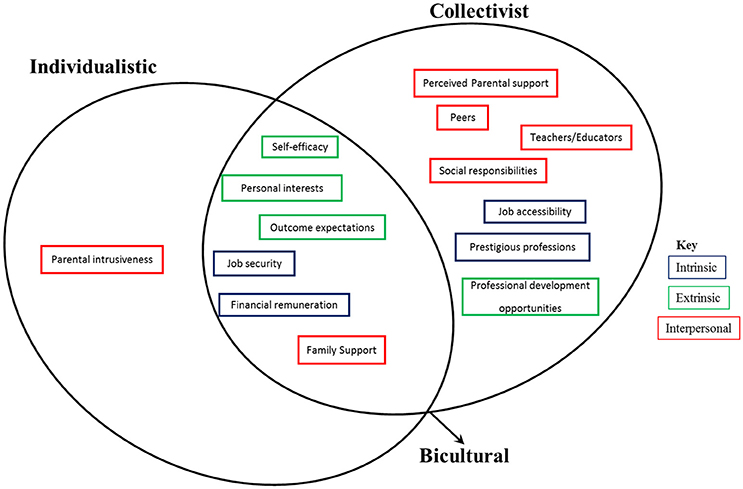

All three factors (Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Interpersonal) affecting adolescents' career choices were identified in this review (Figure 2 ). Out of the 30 articles, five (17%) explored interpersonal factors exclusively ( Cheung et al., 2013 ; Gunkel et al., 2013 ; Fan et al., 2014 ; Zhang et al., 2014 ; Fouad et al., 2016 ). Majority of the studies, 16 out of 30 (53%) explored interpersonal and intrinsic factors solely ( Mau, 2000 ; Lee, 2001 ; Caldera et al., 2003 ; Howard et al., 2009 ; Lent et al., 2010 ; Shin and Kelly, 2013 ; Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ; Sawitri et al., 2014 , 2015 ; Guan et al., 2015 ; Li et al., 2015 ; Sawitri and Creed, 2015 , 2017 ; Kim et al, 2016 ; Hui and Lent, 2018 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ).

Figure 2 . Diagrammatic illustration of the included studies highlighting the factors that influence youth career choices. The figure shows the number of studies focusing on each of the three factors (intrinsic, extrinsic and interpersonal).

No articles focused solely on extrinsic or intrinsic factors. Two studies each explored the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic ( Choi and Kim, 2013 ; Atitsogbe et al., 2018 ) as well as extrinsic and interpersonal factors ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ; Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ). The remaining five articles (17%) explored all three factors (intrinsic, extrinsic, and interpersonal, ( Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ; Agarwala, 2008 ; Gokuladas, 2010 ; Fan et al., 2012 ; Tao et al., 2018 ). Table 1 summarizes the 30 articles included in this review. Intrinsic factors explored in the literature include self-interest, job satisfaction, and learning experiences. Extrinsic factors include job security, guaranteed job opportunities, high salaries, prestigious professions and future benefits. Meanwhile, interpersonal factors include parental support, family cohesion, peer influence, and interaction with educators.

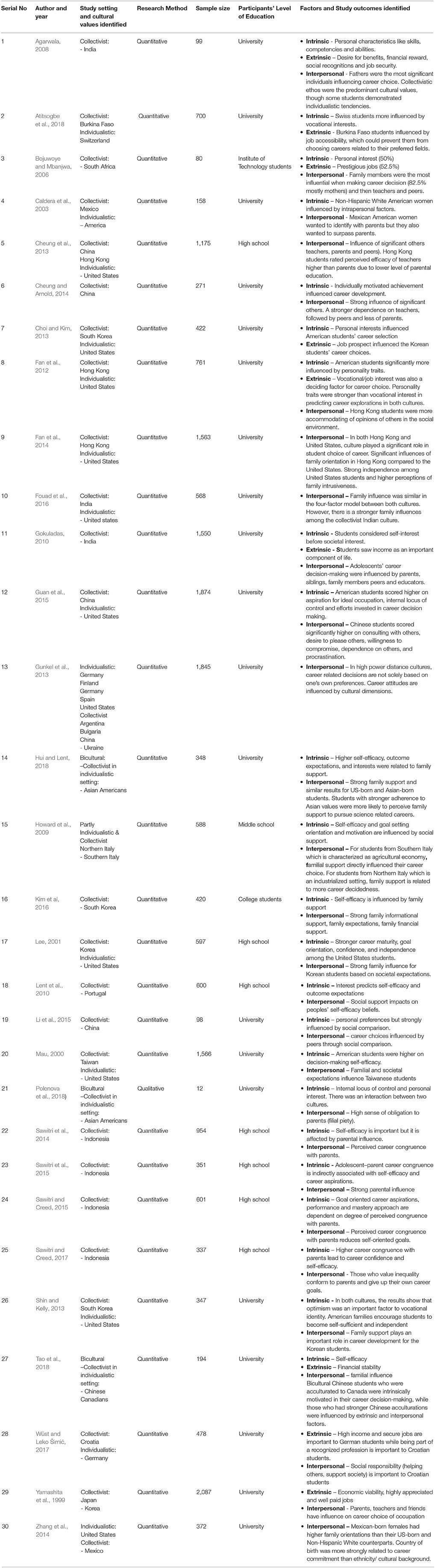

Table 1 . Summary of studies included in the review.

The collectivist cultural settings examined in the reviewed articles included Argentina, Burkina Faso, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Portugal, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan and Ukraine; while the individualistic ones were Canada, Finland, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and United States of America. Italy was considered as partly individualistic and collectivist. Fourteen studies included participants from both collectivist and individualistic cultural settings ( Mau, 2000 ; Lee, 2001 ; Caldera et al., 2003 ; Howard et al., 2009 ; Fan et al., 2012 , 2014 ; Cheung et al., 2013 ; Choi and Kim, 2013 ; Gunkel et al., 2013 ; Shin and Kelly, 2013 ; Zhang et al., 2014 ; Guan et al., 2015 ; Fouad et al., 2016 ; Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ; Atitsogbe et al., 2018 ; Hui and Lent, 2018 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ; Tao et al., 2018 ). Twelve studies focused on collectivist cultural settings ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ; Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ; Agarwala, 2008 ; Gokuladas, 2010 ; Lent et al., 2010 ; Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ; Sawitri et al., 2014 , 2015 ; Li et al., 2015 ; Kim et al, 2016 ; Sawitri and Creed, 2017 ). Three studies examined participants who moved from collectivist to individualistic settings ( Hui and Lent, 2018 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ; Tao et al., 2018 ) and one study considered both cultural dimensions within a single setting ( Howard et al., 2009 ). Twenty-nine of the included studies used a range of quantitative designs. Participant numbers in these ranged from 80 to 2087. One study used qualitative design with 12 participants.

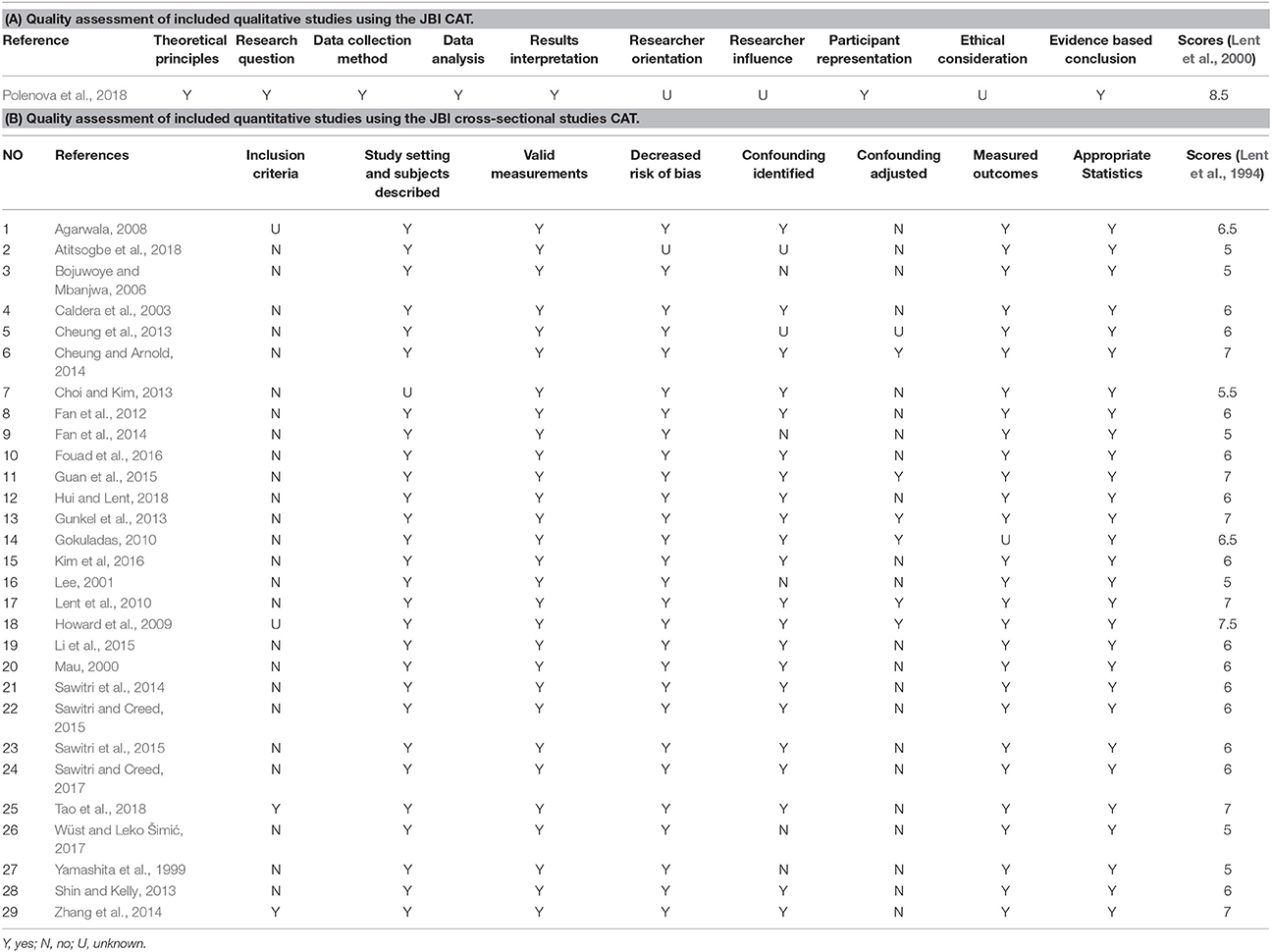

Quality of Methods of Included Studies

The quality assessment of methods employed in the 30 studies included in this review are outlined in Table 2 . The qualitative study was assessed using the JBI qualitative CA tool and was of sound methodology (Table 2A ). Using the JBI cross-sectional CA tool, 9 of the 29 quantitative studies (31 %) were of sound methodology (score of 6.5–7). The other 20 studies (69 %) were of moderate quality (Table 2B ).

Table 2 . Quality assessment of included articles.

Synthesis of Study Results

Table 1 and Figure 3 details the study setting and the underlying factors influencing youth career choices. Analysis of the reviewed articles revealed four major themes namely: extrinsic, intrinsic and interpersonal factors and emergent bicultural influence on career choice. These four major themes had several subthemes and are reported below.

Figure 3 . Career influencing factors. The figures shows identified career influencing factors and their distribution in cultural settings.

Extrinsic Factors

Extrinsic factors examined in the reviewed articles included financial remuneration, job security, professional prestige and job accessibility.

Financial Remuneration

Financial remuneration was identified as the most influential extrinsic factor in career choice decision. Income was considered as an important component of life, particularly among youth who had a higher level of individualism ( Agarwala, 2008 ; Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ). Wüst and Leko Šimić reported that German students ranked “a high income” highest with a 3.7 out of 5 and regarded it as the most important feature of their future job in comparison to Croatian students who gave it a lower ranking of 3 out of 5 ( Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ). While amongst Indian management students, it was rated as the third most important factor influencing career choice ( Agarwala, 2008 ). Financial reward was also a high motivator for career decision among Chinese migrant students in Canada ( Tao et al., 2018 ), and Korean students ( Choi and Kim, 2013 ). In contrast, the need for higher remuneration did not influence career decision making among engineering students in India ( Gokuladas, 2010 ), and Japanese senior college students ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ).

Professional Prestige

Professional prestige was identified as an important deciding factor for youth career decision making in India ( Agarwala, 2008 ), South Africa ( Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ), Croatia ( Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ), Japan and Korea ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ), which are all collectivist settings. Prestige statuses attached to some occupations were strong incentives to career choices; was ranked as the second most important positive influence in career decision making by over half of the respondents in a South African study, indicating that these youth wanted prestigious jobs so that they could live good lives and be respected in the society ( Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ). Japanese and Korean students were also highly influenced by occupational prestige ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ); however, the Korean students considered it of higher importance than their Japanese counterparts.

Job Accessibility

Job accessibility was also considered as a deciding factor for youth's career decision in a collectivist Burkina Faso society where nearness to employment locations prevented students from choosing careers related to their preferred fields of endeavor ( Atitsogbe et al., 2018 ). Another study explored the perceptions of hospitality and tourism career among college students and demonstrated that Korean students are more likely to focus on current market trends such as job accessibility in comparison to their American counterparts ( Choi and Kim, 2013 ), implying that they are less flexible with their choices. However, job accessibility and vocational interest were less predictive of career explorations than personality traits in both cultural settings in a different study ( Fan et al., 2012 ).

Job Security

Job security was reported as influential in only one study where it was identified as highly important by German youth in comparison to their Croatian counterparts ( Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ). They suggested that their finding are in line with the uncertainty avoidance index proposed by Hofstede (2011) which also takes on a relatively high value for Germans. They provided two major reasons for the findings—(1) “secure jobs” has a tradition for young Germans and (2) change in employment contracts in Germany; with fewer employees under 25 having permanent contracts ( Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ).

Intrinsic Factors

The literature explored intrinsic factors such as personal interests, self-efficacy, outcome expectations and professional development opportunities.

Personal Interests

Personal interests in career decision-making appeared to be an important factor in the selection of a life career ( Caldera et al., 2003 ; Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ; Gokuladas, 2010 ; Lent et al., 2010 ; Choi and Kim, 2013 ; Atitsogbe et al., 2018 ). Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa ascertained that about fifty per cent of youth career decisions are based on their personal interests ( Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ), and Gokuladas maintained that students from urban areas are most likely to consider their personal interests before societal interests when making career decisions ( Gokuladas, 2010 ). Lent et al., reported that personal interest predict youth's career outcome expectations ( Lent et al., 2010 ) while Li et al., indicated that in collectivist Chinese culture, personal interests matter significantly however individual preferences are strongly influenced by social comparison ( Li et al., 2015 ). Atitsogbe et al., observed that Swiss students are more influenced by personal interests ( Atitsogbe et al., 2018 ). They reported that in Switzerland, interest differentiation was significantly associated with self-identity. This scenario was compared to the situation in the collectivist Burkina Faso culture where interest differentiation and consistency were less associated self-identity ( Atitsogbe et al., 2018 ). Similarly, Korean students were reported to focus on the prevailing market trends such as salary, job positions, and promotion opportunities in contrast to American student who were more future oriented and interested in setting individual desired goals in their reality oriented-perceptions ( Choi and Kim, 2013 ). Personal interest was also linked to career aspirations in Mexican American women ( Caldera et al., 2003 ).

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy was considered a vital intrinsic factor in the career decision-making process of youth ( Howard et al., 2009 ; Fan et al., 2012 ; Guan et al., 2015 ; Hui and Lent, 2018 ). Howard et al. reported individualistic and collectivist dimensions in two different regions within the same country due to economic factors ( Howard et al., 2009 ). In collectivist cultures, students' self-efficacy was linked to their level of congruence with their parents. Whereas in individualistic cultural settings, like America, families encourage students to become self-sufficient and independent ( Mau, 2000 ; Fan et al., 2012 ; Shin and Kelly, 2013 ; Guan et al., 2015 ; Hui and Lent, 2018 ).

Outcome Expectations

Two studies carried out in collectivist cultural settings reported that youth's outcome expectation are contingent/dependent on the degree of perceived congruence with parents ( Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ; Sawitri et al., 2015 ). One article that studied the outcome expectations of youth in individualistic cultural setting reported that among students in the United States, strong career maturity, confidence, and outcome expectations were culturally based ( Lee, 2001 ).

Professional Development Opportunities

The opportunity for professional development is also a major intrinsic career-influencing factor ( Lee, 2001 ; Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ; Guan et al., 2015 ). University students in China were individually matured and influenced by career development opportunities ( Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ). While American students were shown to score higher for ideal occupations ( Guan et al., 2015 ), and influenced by goal motivation and strong career maturity ( Lee, 2001 ). This is similar to high school students in Indonesia, although dependent on congruence with parents ( Sawitri and Creed, 2015 ).

Interpersonal Factors

The literature discussed the extent to which family members, teachers/educators, peers, and social responsibilities influence youth's career decision-making.

Influence of Family Members

Agarwala suggested the father was seen as the most significant individual influencing the career choice of Indian management students ( Agarwala, 2008 ). This could be understood in the context of a reasonably patriarchal society. According to the study, most of the participants' fathers were mainly professionals, which may have motivated their career selection. In another study, mothers (52.50%) were regarded as the most significant family member that impacted positively on students' career choices ( Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ). Fathers (18.75%) were the second most significant individual, followed by siblings or guardians (16.25%) ( Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ). Good rapport among family members culminating in an effective communication within the family set up is crucial for laying sound foundation for career decision making. Higher career congruence with parents also increased career confidence and self-efficacy ( Sawitri et al., 2014 , 2015 ; Sawitri and Creed, 2015 , 2017 ; Kim et al, 2016 ). Furthermore, parents' profession influences career choice as children from agricultural backgrounds tend to take on their parents' job, while those from industrialized settings have more autonomy and career decidedness ( Howard et al., 2009 ).

Other familial influence on career decision-making according to the results of the only qualitative study in our review, include parental values, parental pressure, cultural capital and family obligations ( Polenova et al., 2018 ). The study indicated the apparent Asian American cultural preference for certain professions/careers. Students indicated that, parental opinion sometimes put an emphasis on a specific career. In that study, several participants emphasized that they were not forced, but “strongly encouraged” ( Polenova et al., 2018 ).

It's not like your parents are going to put a gun to your head and say “You're going to be a doctor” but from a young age, they say things like, “You're going to be a great doctor, I can't wait until you have that stethoscope around your neck.”

Polenova et al., 2018

Teachers and Educators

Teachers and educators are significant figures in the process of youth's career decision-making ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ; Howard et al., 2009 ; Gokuladas, 2010 ; Cheung et al., 2013 ; Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ). Cheung et al. and Howard et al. reported that in both collectivist and individualistic cultures, teacher are seen as significant figures who are agents of development and could have influence on students' career decision making ( Howard et al., 2009 ; Cheung et al., 2013 ). Cheung et al. further reported that students in Hong Kong rated perceived efficacy of teachers higher than parents due to lower level of parental education ( Cheung et al., 2013 ). In addition, Cheung and Arnold demonstrated a strong student dependence on teachers followed by peers and less of parents ( Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ).

Peer Influence

Two studies carried out in both cultural settings showed peer influence as a third potent force (after parents and teachers) that can significantly impact on the career decisions of youth, especially girls ( Howard et al., 2009 ; Cheung et al., 2013 ). Other studies reported that peers are a branch of the significant others and as social agents, they influence their kinds through social comparisons and acceptance ( Yamashita et al., 1999 ; Lee, 2001 ; Bojuwoye and Mbanjwa, 2006 ; Gokuladas, 2010 ; Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ).

Social Responsibilities

The impact of social responsibility as a driving force in youth career decision-making was identified by Fouad et al. (2016) , who noted that the career decision-making of South Korean youth is influenced by societal expectations. This is supported by another research, which suggested that societal expectations influenced youth career choices in both collectivist and individualistic cultures ( Lee, 2001 ; Mau, 2004 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ; Tao et al., 2018 ).

Emergent Bicultural Influence on Youth Career Choices

Of the 30 articles, only three explored the career decision making of bicultural youths ( Hui and Lent, 2018 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ; Tao et al., 2018 ). Strong family support influenced US-born and Asian-born students as shown by a recent study ( Hui and Lent, 2018 ). Hui and Lent found that students with stronger adherence to Asian values were more likely to perceive family support to pursue science related careers ( Hui and Lent, 2018 ). High sense of obligation to parents (filial piety), internal locus of control, and personal interests were identified as factors that influenced bi-cultural Asian American students' career decision making ( Polenova et al., 2018 ). Bicultural Chinese students who were acculturated to Canada were highly intrinsically motivated (internal locus of control and self-efficacy) in their career decision-making, while those who had stronger Chinese acculturations were influenced by extrinsic (financial stability) and interpersonal (family) factors ( Tao et al., 2018 ).

This systematic review examined the existent factors influencing the career choices of the youths from different countries around the globe, from either or both collectivist and individualistic cultural settings. Intrinsic and interpersonal factors were more investigated than extrinsic factors in the reviewed articles. In these articles, intrinsic factors included personal interests, professional advancement, and personality traits. Extrinsic factors included guaranteed employment opportunities, job security, high salaries, prestigious professions and future benefits. Meanwhile, interpersonal factors are the activities of agents of socialization in one's life, such as parental support, family cohesion, status, peer influence as well as interaction with other social agents such as school counsellors, teachers and other educators ( Lent et al., 2010 ; Shin and Kelly, 2013 ; Cheung and Arnold, 2014 ; Guan et al., 2015 ; Kim et al, 2016 ).

The three factors (intrinsic, extrinsic and interpersonal) relating to career choices are pervasive in both cultures. Their level of influence on the youth differs from culture to culture and appear to be dependent on perceived parental congruence leading to self-efficacy and better career choice outcomes. The studies carried out in Canada, Finland, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and United States of America showed a high level of individualism, which typifies intrinsic motivation for career choice. Youths in individualistic cultural settings were influenced by the combinations of intrinsic (personal interest, personality trait, self-efficacy), extrinsic (job security, high salaries) and to a lesser extent, interpersonal (parental guidance) factors and are encouraged to make their own career decisions ( Mau, 2004 ; Gunkel et al., 2013 ). In contrast, studies carried out in Argentina, Burkina Faso, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Portugal, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, and Ukraine showed a high level of collectivism. Youths in collectivist cultures were mainly influenced by interpersonal (honoring parental and societal expectations and parental requirements to follow a prescribed career path) and extrinsic (prestigious professions) ( Mau, 2000 ; Gunkel et al., 2013 ). The opinions of significant others matter significantly to youths from collectivist cultural settings. Whereas, in individualistic cultures, youths tend to focus on professions that offer higher income and satisfy their personal interests ( Wüst and Leko Šimić, 2017 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ).

Parental influences were found to be significant in collectivist cultural settings ( Agarwala, 2008 ; Sawitri et al., 2014 ), implying that youths from this culture value the involvement of significant others, especially parents, and other family members, during their career decision-making processes. The activities of parents and significant others are very pivotal in the lives of the youth as they navigate their career paths. Cheung et al. reported the role of significant others (teachers) in influencing youth career choices when parents are unable to suitably play such role ( Cheung et al., 2013 ). Interestingly, one article focused on two different cultural orientations within one country and reported that parents' profession influence career choice as children from agricultural backgrounds tend to take on their parents' job, while those from industrialized settings have more autonomy and career decidedness ( Howard et al., 2009 ). This finding emphasizes the complex interplay of cultural context and the environment in the career aspirations of youths ( Fouad et al., 2016 ).

The review suggests that youths of collectivist orientations, tend to subordinate personal interests to group goals, emphasizing the standards and importance of relatedness and family cohesion ( Kim et al, 2016 ). However, such patterns of behavior may be conflicted, particularly during cross-cultural transitions. Parental influence have been reported to generate difficulties within the family and discrepancies over career choice decisions are not uncommon within both cultures ( Myburgh, 2005 ; Keller and Whiston, 2008 ; Dietrich and Kracke, 2009 ; Sawitri et al., 2014 ). The conundrum is will adolescents of collectivist orientation be comfortable with their cultural ethos after resettling in a different environment with individualistic cultural beliefs and practices?

Our study revealed that when youth transfer from their heritage culture to a different cultural setting, their cultural values are challenged and their career decision-making patterns may be affected. For instance, Tao et al. reported that students of Chinese descent who were acculturated to Canada primed personal interests, self-efficacy and financial stability instead of honoring parental and societal expectations in their career decision-making ( Tao et al., 2018 ). Similarly, Asian American students with stronger adherence to Asian values had a high sense of obligation to parents ( Polenova et al., 2018 ) and were more likely to perceive family support than their counterparts who were more acculturated to American values ( Hui and Lent, 2018 ). Our data also suggest a strong interplay of individualist and collectivist cultural values coexisting in harmony and jointly influencing how the youth in the current global environment define themselves, relate to others, and decide priorities in conforming to social/societal norms. Movement across cultures (migration) leads to several changes and adjustments in an individual's life. The internal and psychological changes the youth may encounter, otherwise known as psychological acculturation, also affect their career identity ( Berry, 1997 ). Given that only three out of the 30 reviewed studies were conducted in bicultural settings ( Hui and Lent, 2018 ; Polenova et al., 2018 ; Tao et al., 2018 ), further studies are recommended to examine the career choice practices of youths who have transferred from collectivistic to individualistic cultures and vice versa.

Practical Implications for Counsellors and Policy Makers

Social Learning Theory proposes that the role of a career counselor is to help clients expand their career choices and help clarify beliefs that can interfere or promote their career plans ( Krumboltz, 1996 ). Culture has a major influence on people's beliefs therefore, it is integral that career counselors are able to provide culturally responsive career directions to guide the youth in the pursuit of their career aspirations. Providing accessible sources of support and empowering youths to openly discuss their concerns relating to career decision-making will broaden the youths' understanding and this could have a significant impact on their academic and career pathways. Family support is important for all youths as they navigate their career explorations, especially for migrants. The role of counselors is not only limited to the youths, it can also benefit the entire family. Essentially, counselors can attempt to engage not just the youths in exploring academic and vocational opportunities, but also offer avenues for families to become involved and connected to the career decision-making processes.

Cultural identities combined with the varied expectations for achievement can be an overwhelming experience for the youth. Counselors can seize this opportunity to provide companionship and direction as the youth figure out their career pathways ( Gushue et al., 2006 ; Risco and Duffy, 2011 ).

The significance of a school environment that is conducive and embraces the racial and academic identity of its students can be a huge asset to boost youth morale. Gonzalez et al. reported that students who feel culturally validated by others at school and experience positive ethnic regard, have more confidence in their career aspirations ( Gonzalez et al., 2013 ). Career counselors together with other educators and service providers hold influential positions as they can furnish academic, cultural and social support that family members alone cannot provide.

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

The major strength of this review is that it has provided increased understanding of the cultural underpinnings of the factors that influence the career choices of youths. The study has also highlighted areas of knowledge gap in the literature, such as fewer studies exploring the impact of extrinsic factors on career choice and the need for more bicultural studies. However, the conclusions drawn from this review are limited to the data that were extracted from the studies identified. We acknowledge that there are caveats with the use of the concepts “collectivist and individualistic” to describe the cultural underpinnings of different countries as there are some fluidity around their usage as suggested by Hofstede (1991 , 2001) . However, the use of these concepts was helpful in classifying the cultural background of the participants included in this review. The findings of the studies reviewed within each country may not necessarily be representative of all the cultural orientations in those countries. Furthermore, researchers from different cultures (or studying different cultures) may have chosen to study only the variables that they believe will have relevance. Nevertheless, most of the studies reviewed had large sample sizes and were conducted in various countries across the globe.

Recommendations

• Of the 30 articles reviewed, only one involved qualitative study designs. Further qualitative studies on this topic are required to provide in-depth understanding of the influences on youth's career choices and to allow causal inferences to be made.

• There were only three articles that examined the career decision-making of the bicultural youths from the perspective of the mainstream and the heritage cultures. Better career choices for the bicultural youth will enhance their self-identity and lead to commitment to duty and eventual career satisfaction. Without harnessing the potentials of youths through career education and training, the bicultural and migrant youths' face uncertainties in the future in the host country. The rippling effects of such uncertainties in the future could have a detrimental effect on the country's economy. Therefore, there is the need for increased research activities in this area in host countries. Educational system planning should be developed to encourage youth to have self-efficacy and be more involved in job-related information seeking. This will be especially efficient in progressing bicultural youths who might have migrated with their parents into a new culture.

• Sound education at school can open ways for career decisions. Interventions designed to assist youth in strengthening their academic self-efficacy, internal motivation, and goal-setting strategies can foster improved career choice outcomes.

Conclusions

The three factors investigated in this study are pervasive in influencing the career decisions of youths in both individualistic and collectivist societies. In collectivist societies, parental intervention is understood as a requirement to support their children's efforts and equip them to be responsible and economically productive. Meanwhile, the standard practice in individualistic societies is for parents to endorse their children's opinions and encourage them to choose careers that make them happy. Overall, further research is imperative to guide the understanding of parental influence and diversity in bicultural and migrant youths' career prospects and their ability to use the resources available in their new environments to attain meaningful future career goals. Additional research, particularly qualitative, is required to explore the level of family involvement in youths' career choices among migrant families in different cultural settings.

Author Contributions

PA-T and BM-A extracted the data. BM-A, TE, and DL critically appraised and validated the study findings. PA-T developed the first draft of the manuscript. BM-A, TE, DL, and KT reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Agarwala, T. (2008). Factors influencing career choice of management students in India. Career Dev. Int. 13, 362–376. doi: 10.1108/13620430810880844

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Amit, A., and Gati, I. (2013). Table or circles: a comparison of two methods for choosing among career alternatives. Career Dev. Q. 61, 50–63. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00035.x

Aromataris, E., and Munn, Z. E. (2017). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual . The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available online at: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

Atitsogbe, K. A., Moumoula, I. A., Rochat, S., Antonietti, J. P., and Rossier, J. (2018). Vocational interests and career indecision in Switzerland and Burkina Faso: cross-cultural similarities and differences. J. Vocat. Behav. 107, 126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.04.002

Bakar, A. R., Mohamed, S., Suhid, A., and Hamzah, R. (2014). So you want to be a teacher: what are your reasons? Int. Educ. Stud. 7, 155–161. doi: 10.5539/ies.v7n11p155

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol . 46, 5–34.

Google Scholar

Beynon, J., Toohey, K., and Kishor, N. (1998). Do visible minority students of Chinese and South Asian ancestry want teaching as a career?: perceptions of some secondary school students in Vancouver, B. C. Can. Eth. Stud. J. 30:50.

Blanco, Á. (2011). Applying social cognitive career theory to predict interests and choice goals in statistics among Spanish psychology students. J. Voc. Behavior . 78, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.07.003

Bojuwoye, O., and Mbanjwa, S. (2006). Factors impacting on career choices of technikon students from previously disadvantaged high schools. J. Psychol. Afr . 16, 3–16. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2006.10820099

Bossman, I. (2014). Bossman, Ineke, Educational Factors that Influence the Career Choices of University of Cape Coast Students (April 5) . Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2420846

Bubić, A., and Ivanišević, K. (2016). The role of emotional stability and competence in young adolescents' career judgments. J. Career Dev . 43, 498–511. doi: 10.1177/0894845316633779

Caldera, Y. M., Robitschek, C., Frame, M., and Pannell, M. (2003). Intrapersonal, familial, and cultural factors in the commitment to a career choice of mexican american and non-hispanic white college Women. J. Counsel. Psychol. 50, 309–323. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.3.309

Carpenter, P., and Foster, B. (1977). The career decisions of student teachers. Educ. Res. Pers. 4, 23–33.

Cheung, F. M., Wan, S. L. Y., Fan, W., Leong, F., and Mok, P. C. H. (2013). Collective contributions to career efficacy in adolescents: a cross-cultural study. J. Vocat. Behav . 83, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.05.004

Cheung, R., and Arnold, J. (2014). The impact of career exploration on career development among Hong Kong Chinese University students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev . 55, 732–748. doi: 10.1353/csd.2014.0067

Choi, K., and Kim, D. Y. (2013). A cross cultural study of antecedents on career preparation behavior: learning motivation, academic achievement, and career decision self-efficacy. J. Hosp. Leis Sports Tour Educ . 13, 19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2013.04.001

Dietrich, J., and Kracke, B. (2009). Career-specific parental behaviors in adolescents' development. J. Vocat. Behav . 75, 109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.005

Edwards, K., and Quinter, M. (2011). Factors influencing students career choices among secondary school students in Kisumu municipality, Kenya. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2, 81–87. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC135714

Fan, W., Cheung, F. M., Leong, F. T. L., and Cheung, S. F. (2014). Contributions of family factors to career readiness: a cross-cultural comparison. Career Dev. Q. 62, 194–209. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2014.00079.x

Fan, W., Cheung, F. M., Leong, F. T., and Cheung, S. F. (2012). Personality traits, vocational interests, and career exploration: a cross-cultural comparison between American and Hong Kong students. J. Career Assess . 20, 105–119. doi: 10.1177/1069072711417167

Fouad, N. A., Kim, S.-y., Ghosh, A., Chang, W., and Figueiredo, C. (2016). Family influence on career decision making:validation in india and the United States. J. Career Assess. 24, 197–212. doi: 10.1177/1069072714565782

Gati, I., and Saka, N. (2001). High school students' career-related decision-making difficulties. J. Counsel. Dev . 79:331. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01978.x

Gokuladas, V. K. (2010). Factors that influence first-career choice of undergraduate engineers in software services companies: a South Indian experience. Career Dev. Int. 15, 144–165. doi: 10.1108/13620431011040941

Gonzalez, L. M., Stein, G. L., and Huq, N. (2013). The Influence of Cultural identity and perceived barriers on college-going beliefs and aspirations of latino youth in emerging immigrant communities. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 35, 103–120. doi: 10.1177/0739986312463002

Guan, Y., Chen, S. X., Levin, N., Bond, M. H., Luo, N., Xu, J., et al. (2015). Differences in career decision-making profiles between american and chinese university students: the relative strength of mediating mechanisms across cultures. J. Cross-Cult Psychol . 46, 856–872. doi: 10.1177/0022022115585874

Gunkel, M., Schlägel, C., Langella, I. M., Peluchette, J. V., and Reshetnyak, E. (2013). The influence of national culture on business students' career attitudes - An analysis of eight countries. Z Persforsch . 27, 47–68. doi: 10.1177/239700221302700105

Gushue, G., Clarke, C., Pantzer, K., and Scanlan, K. (2006). Self-efficacy, perceptions of barriers, vocational identity, and the career exploration behaviour of Latino/ a high school students. Carreer Dev. Q. 54, 307–317. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00196.x

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2:8. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Howard, K. A. S., Ferrari, L., Nota, L., Solberg, V. S. H., and Soresi, S. (2009). The relation of cultural context and social relationships to career development in middle school. J. Vocat. Behav. 75, 100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.013

Howard, K. A., and Walsh, M. E. (2011). Children's conceptions of career choice and attainment: model development. J. Career Dev . 38, 256–271. doi: 10.1177/0894845310365851

Hui, K., and Lent, R. W. (2018). The roles of family, culture, and social cognitive variables in the career interests and goals of Asian American college students. J. Couns. Psychol . 65, 98–109. doi: 10.1037/cou0000235

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

IOM (2018). Key Migration Terms . Available online at: https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

Keller, B. K., and Whiston, S. C. (2008). The role of parental influences on young adolescents' career development. J. Career Assess. 16, 198–217. doi: 10.1177/1069072707313206

Kim, S.-,Y., Ahn, T., and Fouad, N. (2016). Family influence on korean students' career decisions: a social cognitive perspective. J. Career Assess. 24, 513–526. doi: 10.1177/1069072715599403

Krumboltz, J. (1996). “A learning theory of career counseling,” in Handbook of Career Counseling Theory and Practice , eds M. L. Savickas and W. Bruce Walsh (Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black), 55–80.

Kunnen, E. S. (2013). The effects of career choice guidance on identity development. Educ. Res. Int . 2013:901718. doi: 10.1155/2013/901718

Lee, K.-H. (2001). A cross-cultural study of the career maturity of Korean and United States high school students. J. Career Dev . 28, 43–57. doi: 10.1177/089484530102800104

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., and Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 45, 79–122. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., and Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: a social cognitive analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 47:36. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36

Lent, R. W., Paixao, M. P., da Silva, J. T., and Leitao, L. M. (2010). Predicting occupational interests and choice aspirations in portuguese high school students: a test of social cognitive career theory. J. Voc. Behav. 76, 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.10.001

Li, X., Hou, Z. J., and Jia, Y. (2015). The influence of social comparison on career decision-making: vocational identity as a moderator and regret as a mediator. J. Vocat. Behav . 86, 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.003

Mau, W. C. (2000). Cultural differences in career decision-making styles and self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav . 57, 365–378. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1745

Mau, W. C. J. (2004). Cultural dimensions of career decision-making difficulties. Career Dev. Q. 53, 67–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2004.tb00656.x

Myburgh, J. (2005). An empirical analysis of career choice factors that influence first-year Accounting students at the University of Pretoria: a cross-racial study. Meditari Account. Res. 13:35. doi: 10.1108/10222529200500011

Nyamwange, J. (2016). Influence of students' Interest on Career Choice among First Year University Students in Public and Private Universities in Kisii County, Kenya. J. Educ. Pract. 7:7.

Oettingen, G., and Zosuls, C. (2006). “Culture and self-efficacy in adolescents,” in Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents , eds F. Pajeres and T. Urdan (Greenwich: Information Age Publishing), 245–265.

Polenova, E., Vedral, A., Brisson, L., and Zinn, L. (2018). Emerging between two worlds: a longitudinal study of career identity of students from Asian American immigrant families. Emerg. Adulthood . 6, 53–65. doi: 10.1177/2167696817696430

Porfeli, E. J., and Lee, B. (2012). Career development during childhood and adolescence. New Dir. Youth Dev . 2012, 11–22. doi: 10.1002/yd.20011

Risco, C. M., and Duffy, R. D. (2011). A Career Decision-making profile of latina/o incoming college students. J. Career Dev . 38, 237–255. doi: 10.1177/0894845310365852

Robertson, P. J. (2014). Health inequality and careers. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 42, 338–351. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2014.900660

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol . 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sawitri, D. R., and Creed, P. A. (2015). Perceived career congruence between adolescents and their parents as a moderator between goal orientation and career aspirations. Pers. Individ. Dif. 81, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.061

Sawitri, D. R., and Creed, P. A. (2017). Collectivism and perceived congruence with parents as antecedents to career aspirations: a social cognitive perspective. J. Career Dev. 44, 530–543. doi: 10.1177/0894845316668576

Sawitri, D. R., Creed, P. A., and Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2014). Parental influences and adolescent career behaviours in a collectivist cultural setting. Int. J. Educ. Voc. Guid. 14, 161–180. doi: 10.1007/s10775-013-9247-x

Sawitri, D. R., Creed, P. A., and Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2015). Longitudinal relations of parental influences and adolescent career aspirations and actions in a collectivist society. J. Res. Adolesc. 25, 551–563. doi: 10.1111/jora.12145

Shin, Y.-J., and Kelly, K. R. (2013). Cross-cultural comparison of the effects of optimism, intrinsic motivation, and family relations on vocational identity. Career Dev. Q. 61, 141–160. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00043.x

Shoffner, M. F., Newsome, D., Barrio Minton, C. A., and Wachter Morris, C. A. (2015). A Qualitative Exploration of the STEM career-related outcome expectations of young adolescents. J. Career Dev . 42, 102–116. doi: 10.1177/0894845314544033

Sinha, J. B. (ed.). (2014). “Collectivism and individualism,” in Psycho-Social Analysis of the Indian Mindset (New Delhi: Springer), 27–51.

Tao, D., Zhang, R., Lou, E., and Lalonde, R. N. (2018). The cultural shaping of career aspirations: acculturation and Chinese biculturals' career identity styles. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 50, 29–41. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000091

UNESCO (2017). Learning to Live Together: What Do We Mean by “Youth”? Available online at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-%20%20%20sciences/themes/youth/youth-definition/ .

Wambu, G., Hutchison, B., and Pietrantoni, Z. (2017). Career decision-making and college and career access among recent African immigrant students. J. College Access . 3:17. Available online at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jca/vol3/iss2/6

Wu, L. T., Low, M. M., Tan, K. K., Lopez, V., and Liaw, S. Y. (2015). Why not nursing? A systematic review of factors influencing career choice among healthcare students. Int. Nurs. Rev. 62, 547–562. doi: 10.1111/inr.12220

Wüst, K., and Leko Šimić, M. (2017). Students' career preferences: intercultural study of Croatian and German students. Econ. Sociol. 10, 136–152. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-3/10

Yamashita, T., Youn, G., and Matsumoto, J. (1999). Career decision-making in college students: cross-cultural comparisons for Japan and Korea. Psychol Rep . 84(3 Part 2), 1143–1157. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1143

Zhang, L., Gowan, M. A., and Trevi-o, M. (2014). Cross-cultural correlates of career and parental role commitment. J. Manage Psychol . 29, 736–754. doi: 10.1108/JMP-11-2012-0336

Keywords: career choice, youths, collectivist culture, individualistic culture, cross-cultures

Citation: Akosah-Twumasi P, Emeto TI, Lindsay D, Tsey K and Malau-Aduli BS (2018) A Systematic Review of Factors That Influence Youths Career Choices—the Role of Culture. Front. Educ . 3:58. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00058

Received: 31 January 2018; Accepted: 28 June 2018; Published: 19 July 2018.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2018 Akosah-Twumasi, Emeto, Lindsay, Tsey and Malau-Aduli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter Akosah-Twumasi, [email protected]

Advertisement

Perceived support and influences in adolescents’ career choices: a mixed-methods study

- Open access

- Published: 02 September 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jenny Marcionetti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7906-8785 1 &

- Andrea Zammitti 2

2180 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Support and influences on adolescents’ career choices come from a variety of sources. However, studies comparing the importance given to various sources of support are few, and none have analyzed differences in the support provided by mothers and fathers. This study aimed to examine quantitatively the importance given to support from various sources in a sample of 432 Swiss adolescents at two points in time in the period of choice and to explore qualitatively experiences related to support given/received by 10 mother–child dyads in the career choice process. The overall results endorse the mother as the main source of support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Associations between social support, career self-efficacy, and career indecision among youth

Reciprocal effects between parental support and career maturity in the developmental process of career maturity

Configuration of Parent-Reported and Adolescent-Perceived Career-Related Parenting Practice and Adolescents’ Career Development: A Person-Centered, Longitudinal Analysis of Chinese Parent–Adolescent Dyads

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With the arrival of adolescence, career planning becomes very important (Gati & Saka, 2001 ). Among the main difficulties that adolescents have to overcome, there are school–professional choices (Lodi et al., 2008 ). In fact, around the age of 14–15 years, adolescents must make choices about their future and can live a condition of indecision and insecurity that is associated with difficulties in making decisions and with procrastination or avoidance of the choice task (Nota & Soresi, 2002 ). This process is certainly not facilitated by the 21st-century context, in which it is increasingly difficult to make predictions, ask for suggestions, or choose (Soresi & Nota, 2015 ).

It is widely recognized that parental support plays a fundamental role in career development of sons and daughters (Whiston & Keller, 2004 ), and in particular the support provided by mothers (Colarossi & Eccles, 2003 ; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992 ; Levitt et al., 1993 ). School actors, principally teachers, have also been found to be an important source of support for career choices (Wong et al., 2021 ). Although various studies agree on the importance of adolescents perceiving social support to deal with the career choice process (Whiston & Keller, 2004 ), still few have been interested in understanding what the most important sources of this support are (e.g. Cheung & Arnold, 2010 ; Gushue & Whitson, 2006 ), distinguishing not only between parents, school guidance counselors, and teachers but also between mothers and fathers, and also investigating whether the adolescent’s gender might influence this perception. In addition, few have studied adolescents’ perceptions of influences they have had and support received relating to the career choice and at the same time their parents’ perceptions of influence and support provided using a qualitative approach.

The present study thus had two main aims, each pursued with a specific approach. The first, using a quantitative approach, was to examine the importance of different sources of support in a sample of adolescents at two points in time in their last year of compulsory school. The second, with a qualitative approach, was to delve into the experience related to support given/received by 10 mother–child dyads in the career choice process.

Parental influences

Parents are a major source of interpersonal support and can influence their children’s self-efficacy and professional expectations, their interests, and career goals (Kenny & Medvide, 2013 ). It has been shown that adolescents consider it normal to be influenced by their parents in career choices and do not think that decisions will be made only by them (Bernardo, 2010 ). Indeed, the expectations of parents contribute to obtaining positive career outcomes (Fouad et al., 2008 ). However, this is valid only when the adolescent believes he can meet these expectations (Leung et al., 2011 ); when the adolescent does not feel up to meeting the expectations of parents, there is the risk of developing psychological distress (Wang & Heppner, 2002 ). Hence, parental support in this area can foster aspirations, exploration, and career planning (Cheung & Arnold, 2010 ; Ma & Yeh, 2010 ) but as long as it is actually perceived as support (Garcia et al., 2012 ).

Career concerns have to do with the stress of planning a future task (Cairo et al., 1996 ; Savickas et al., 1988 ). They represent anxiety about the fact that the individual is managing something important for their professional future (Code & Bernes, 2006 ). Students who find themselves making a choice must deal with this stress and manage the choice also based on the expectations of family, peers, and educational institutions (Creed et al., 2009 ). The career choice process, therefore, implicates emotions (Blustein et al., 1995 ) that involve both the adolescent and their parents. These emotions can stimulate action and make sense of the career development process within the family setting (Young et al., 1997 ). However, they can also be associated with prolonged indecision (Gati et al., 2011 ) and make mothers overly concerned, especially when adolescents hardly discuss their future plans (Kobak et al., 1994 ). Indeed, the behavior of parents concerning the choices of their children can be support, when they help them make choices by providing them with guidance, but also interference, when they excessively control the choices their children make, or lack of engagement, due to disinterest or other factors such as financial problems, overwork, or other (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ).

What has been expressed up to now indicates that parents can be a valid resource that provides instrumental and emotional support to the adolescent in transition increasing self-efficacy in career decision-making (Lent et al., 2003 ), professional and career adaptability (Kenny & Bledsoe, 2005 ; Parola & Marcionetti, 2021 ), career exploration (Kracke, 1997 ), and diminishing indecision about career choices (Guerra & Braungart-Rieker, 1999 ; Marcionetti & Rossier, 2016a ; Parola & Marcionetti, 2021 ). On the other hand, they can also constitute a risk factor in career choices when they interfere too much or lack engagement in this process (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ; Zhao et al., 2012 ).

Colarossi and Eccles ( 2003 ) conducted a study considering the perception of parental support on adolescents in the development of self-esteem or depression; the peculiarity of this study is that parental support was distinguished in support received from fathers and support received from mothers. Indeed, a limitation of research on parental support is that it is often considered as a single measure, without separating maternal and paternal support and considering the gender of the adolescent. The authors have shown, in fact, that the effects are different for male and female adolescents. In particular, male adolescents perceive greater support from fathers than females whereas it has been found that there are no significant differences concerning the perception of the support received from the mothers. Finally, fathers, compared to mothers, teachers and peers were perceived as providers of a smaller amount of support. This study is consistent with other research carried out in this area (Colarossi, 2001 ; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992 ; Levitt et al., 1993 ) and underlines the idea that it is important to differentiate maternal and paternal support. Indeed, according to Leaper et al. ( 1998 ), mothers show a tendency to use more supportive language than fathers and are more involved when it comes to the school and educational decisions of their children. According to this, Ginevra et al. ( 2015 ) and Porfeli et al. ( 2013 ) showed that mothers perceive themselves as more supportive than fathers in the career development of their children. Other authors also confirm these results, which underlines the greater role of mothers compared with fathers in their children’s career choices (e.g., McCabe & Barnett, 2000 ).

School influences

In middle schools, school counselors and career guidance specialists are often the main personnel responsible for monitoring and helping students in sustaining the career choice (Gysbers & Lapan, 2009 ; Multon, 2006 ). This is also the case in Southern Switzerland, where this study has been conducted. However, in studies made in other countries, it emerged that students do not always see their services as sufficient, or helpful (Mortimer et al., 2002 ). Hence, in many countries more responsibility has been given to teachers for supporting their students’ career development. On the one hand, teachers can give “general support” that can promote the development of different career and life competencies during their classes (Kivunja, 2014 ). In this sense, Lei et al. ( 2018 ) say that teachers provide general support in both giving social support, which involves emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal support, and promoting self-determination. Indeed, the teacher supports the development of autonomy, decision-making, and intrinsic motivation, which increase in adolescents the motivation to pursue life and career goals. On the other hand, teachers can give specific career-related support. For Wong et al. ( 2021 ) specific career-related support is “anything a teacher does that can facilitate the career planning of students” (Wong et al., 2021 , p. 132) such as inquiring about career paths, helping students identify their interests, giving information about jobs, and providing help in setting goals. Teacher support has been proven to have a significant impact on the development of students’ career aspirations, future orientation, career exploration, and planning (Alm et al., 2019 ; Hirschi et al., 2011 ; Rogers & Creed, 2011 ).

Studies that have compared the importance of various sources of support in the career decision-making process seem to point to teachers as the most important source of support (although the differences are never huge). These studies are few in number and have been conducted on quite diverse samples in terms of culture and age and considering different career-related outcomes. For example, Gushue and Whitson ( 2006 ) in the USA have shown that teachers support has more effect than parental support on the level of African American ninth-grade public high school students’ positive expectations about the career chosen. The study from Di Fabio and Kenny ( 2015 ) with Italian high school students suggests that teacher support contributes more than peer support in increasing resilience, perceived employability, and self-efficacy. Cheung and Arnold ( 2010 ) found that teacher support is more effective than parental and peers’ support in predicting career exploration in Hong Kong university students. Finally, Kenny and Bledsoe ( 2005 ) in a sample of US urban high school students showed that support from family, teachers, close friends, and peer beliefs about school all contributed significantly to the explanation of the four dimensions of career adaptability, school identification, perceptions of educational barriers, career outcome expectations, and career planning. Moreover, they analyzed the different contribution of each relational variable when controlling for the others, finding that family support contributed to explaining variance in perceived educational barriers and career expectations; teacher support contributed to explaining variance in school identification; and perceived peer beliefs contributed to explaining perceived educational barriers and school identification. The results thus seem to indicate that different actors may contribute differently to support the choice process. This suggests that all actors can play an important role in providing support. However, no study to our knowledge has captured adolescents’ perceptions with respect to which figure has been most supportive in this process. It is indeed important that not only does the support offered have a concrete effect on the choice process, but also that it is recognized, otherwise risking being interpreted as “lack of engagement,” and positively valued by the adolescent, otherwise risking being interpreted as “interference” (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ).

Methodologies to study career-related social support

Social support can be provided by close relatives such as parents and siblings and by other persons more or less trained to give it, such as career counselors and teachers. It can also be of different types; for instance, Cutrona and Russell ( 1990 ) and Cutrona ( 1996 ) distinguished between emotional support (the support given through love and empathy, concern, comfort, and security), social integration or network support (the support given by the feeling part of a group with people who hold similar interests and concerns), esteem support (the support that boosts others self-confidence through respect for others qualities, belief in another’s abilities, and validation of thoughts, feelings, or actions), information support (the factual input, advice, or guidance and appraisal of the situation), and tangible assistance (the support through instrumental assistance with tasks or resources). Moreover, the support received, and then perceived, can be influenced by one’s tendency and ability to ask for it (Marcionetti & Rossier, 2016b ). The same goes for the ability to give support and then to feel efficient in giving it. Finally, all these aspects can be influenced by cultural differences (Ishii et al., 2017 ).

Despite the complex nature of social support, there are few studies in which adolescents were asked who the most important people were in providing support in the process of school and career choice by directly asking them for their opinion on the matter. As mentioned earlier, we believe it is important that the support offered (by parents, school and career counselor, teacher, or peers) is also perceived and evaluated positively, lest it instead be deemed lacking in engagement or experienced as interference (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ). Moreover, the studies carried out to investigate the importance of different sources of career-related support for adolescents are mostly quantitative in nature, although there are some exceptions (e.g., Schultheiss et al., 2001 ; Young & Friesen, 1992 ). There is also a lack of studies investigating how parents–child relationships are influential in the career development process and the parents and children’s cross-perceptions of them and of the emotionality felt in them.

An interesting way to fill some of these research gaps is to use a mixed-methods research design. What is unique about these methods is that they allow both quantitative and qualitative approaches to be used in a single research study or set of related studies. To do this there are various ways that can make one or the other of these approaches precede the other and give different or equal importance to them (Creswell & Creswell, 2017 ; Stick & Lincoln, 2006 ). For example, in a first phase, quantitative data can be collected through the administration of a questionnaire. Then, the descriptive data provided in this phase of the study can be used to guide the subsequent qualitative data collection with face-to-face interviews. Thus, mixed method research utilizes a quantitative and qualitative approach to create a stronger research result than either method individually (Malina et al., 2011 ).