Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- 20th Century

The 8 Most Important Inventions and Innovations of World War One

Peta Stamper

04 aug 2021.

World War One was a conflict unlike any experienced before it, as inventions and innovations changed the way warfare was conducted before the 20th century. Many of the new players that arose from World War One have since become familiar to us both in military and peacetime contexts, repurposed after armistice in 1918 .

Among this wealth of creations, these 8 give particular insight into how war affected different groups of people – women, soldiers, Germans at home and away – both during and after World War One.

1. Machine guns

Revolutionising warfare, the traditional horse-drawn and cavalry combat was no match for guns that could shoot multiple bullets at the pull of a trigger. First invented by Hiram Maxim in the United States in 1884, the Maxim gun (shortly known after as the Vickers gun) was adopted by the German Army in 1887.

At the start of World War One machine guns like the Vickers were hand cranked, yet by the war’s end they had evolved into fully automatic weapons capable of firing 450-600 rounds a minute. Specialised units and techniques such as ‘barrage fire’ were devised during the war to fight using machine guns.

With the availability of internal combustion engines, armoured plates and the issues of manoeuvrability posed by trench warfare, the British quickly sought a solution to providing troops with mobile protection and firepower. In 1915, the Allied forces began developing armoured ‘landships’, modelled on and disguised as water tanks. These machines could cross difficult terrain using their caterpillar tracks – in particular, trenches.

By the Battle of the Somme in 1916, land tanks were being used during combat. At the Battle of Flers-Courcelette the tanks demonstrated undeniable potential, despite also having been shown to be death traps for those operating them from inside.

It was the Mark IV, weighing 27-28 tons and crewed by 8 men, that changed the game. Boasting a 6 pound gun plus a Lewis machine gun, over 1,000 Mark IV tanks were made during the war, proving successful during the Battle of Cambrai . Having become integral to war strategy, in July 1918 the Tanks Corps was founded and had around 30,000 members by the war’s end.

3. Sanitary products

Cellucotton existed before war broke out in 1914, created by a small company in the US called Kimberly-Clark (K-C). The material, invented by the firm’s researcher Ernest Mahler while in Germany, was found to be five times more absorbent than normal cotton and was less expensive than cotton when mass produced – ideal for use as surgical dressings when the US entered World War One in 1917 .

Dressing traumatic injuries that needed the sturdy cellucotton, Red Cross nurses on the battlefields started using the absorbent dressings for their sanitary needs. With the end of war in 1918 came the end of the army and Red Cross’ demand for Cellucotton. K-C bought back the surplus from the army and from these leftovers were inspired by the nurses to devise a new sanitary napkin product.

Only 2 years later, the product was released onto the market as ‘Kotex’ (meaning ‘cotton texture’), innovated by the nurses and hand made by women workers in a shed in Wisconsin.

A Kotex newspaper advert 30 November, 1920

Image Credit: CC / cellucotton products company

With poisonous gas used as a silent, psychological weapon during World War One, Kimberly-Clark has also begun experimenting with flattened cellucotton to make gas mask filters.

Without success in the military department, from 1924 K-C decided to sell the flattened cloths as make-up and cold cream removers calling them ‘Kleenex’, inspired by the K and -ex of ‘Kotex’ – the sanitary pads. When women complained their husbands were using Kleenex to blow their noses, the product was rebranded as a more hygienic alternative to handkerchiefs.

Against a growing tide of xenophobia and worries about ‘spies’ on the home front, World War One saw tens of thousands of Germans living in Britain interned in camps as suspected ‘enemy aliens’. One such ‘alien’ was the German bodybuilder and boxer, Joseph Hubertus Pilates, who was interned on the Isle of Man in 1914.

A frail child, Pilates had taken up bodybuilding and performed in circuses all over Britain. Determined to keep us his strength, during his 3 years in the internment camp Pilates developed a slow and precise form of strengthening exercises he named ‘Contrology’.

Internees who had been left bed-ridden and in need of rehabilitation were given resistance training by Pilates, who continued his successful fitness techniques after the war when he opened his own studio in New York in 1925.

6. ‘Peace sausages’

During World War One the British Navy’s blockade – plus a war fought on two fronts – of Germany successfully cut off German supplies and trade, but also meant that food and everyday items became scarce for German civilians. By 1918, many Germans were on the brink of starvation.

Seeing the widespread hunger, Mayor of Cologne Konrad Adenauer (later to become Germany’s first chancellor post-World War Two) began to research alternative food sources – especially meat, which was difficult if not impossible for most people to get hold of. Experimenting with a mixture of rice-flour, Romanian corn flour and barley, Adenauer devised a wheatless bread. Yet hopes of a viable food source were soon dashed when Romania entered the war and the cornflour supply stopped.

Konrad Adenauer, 1952

Image Credit: CC / Das Bundesarchiv

Once again searching for a meat substitute, Adenauer decided on making sausages from soy, calling the new foodstuff Friedenswurst meaning ‘peace sausage’. Unfortunately, he was denied the patent on the Friedenswurst because German regulations meant you could only call a sausage such if it contained meat. The British were evidently not so fussy, however, as in June 1918 King George V awarded the soy sausage a patent.

7. Wristwatches

Wristwatches were not new when war was declared in 1914. In fact, they had been worn by women for a century before the conflict began, famously by the fashionable Queen of Naples Caroline Bonaparte in 1812. Men who could afford a timepiece instead kept it on a chain in their pocket.

However, warfare demanded both hands and easy time-keeping. Pilots needed two hands for flying, soldiers for hands-on fighting and their commanders a way of launching precisely timed advances, such as the ‘creeping barrage’ strategy.

Timing ultimately meant the difference between life and death, and soon wristwatches were in high demand. By 1916 it was believed by the Coventry watchmaker H. Williamson that 1 in 4 soldiers wore a ‘wristlet’ while “the other three mean to get one as soon as they can”.

Even the luxury French watchmaker Louis Cartier was inspired by the machines of war to create the Cartier Tank Watch after seeing the new Renault tanks, the watch mirroring the tanks’ shape.

8. Daylight saving

A US poster showing Uncle Sam turning a clock to daylight saving time as a clock-headed figure throws his hat in the air, 1918.

Image Credit: CC / United Cigar Stores Company

Time was essential to the war effort, both for the military and civilians at home. The idea of ‘daylight saving’ was first suggested by Benjamin Franklin in the 18th century, who noted that summer sunshine was wasted in the mornings while everyone slept.

Yet faced with coal shortages, Germany implemented the scheme from April 1916 at 11pm, jumping forwards to midnight and therefore gaining an extra hour of daylight in the evenings. Weeks later, Britain followed suit. Although the scheme was abandoned after the war, daylight saving returned for good during the energy crises of the 1970s.

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

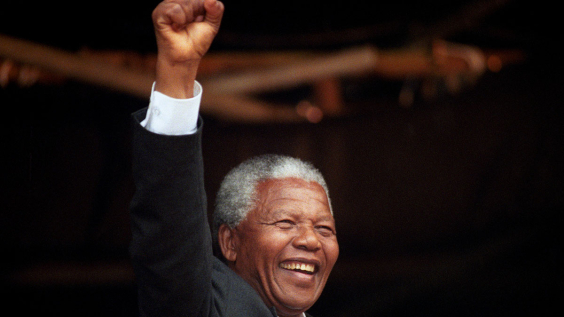

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

Military technology has always shaped and defined how wars were fought. The First World War, however, saw a breadth and scale of technological innovation of unprecedented impact. It was the first modern mechanized industrial war in which material resources and manufacturing capability were as consequential as the skill of the troops on the battlefield.

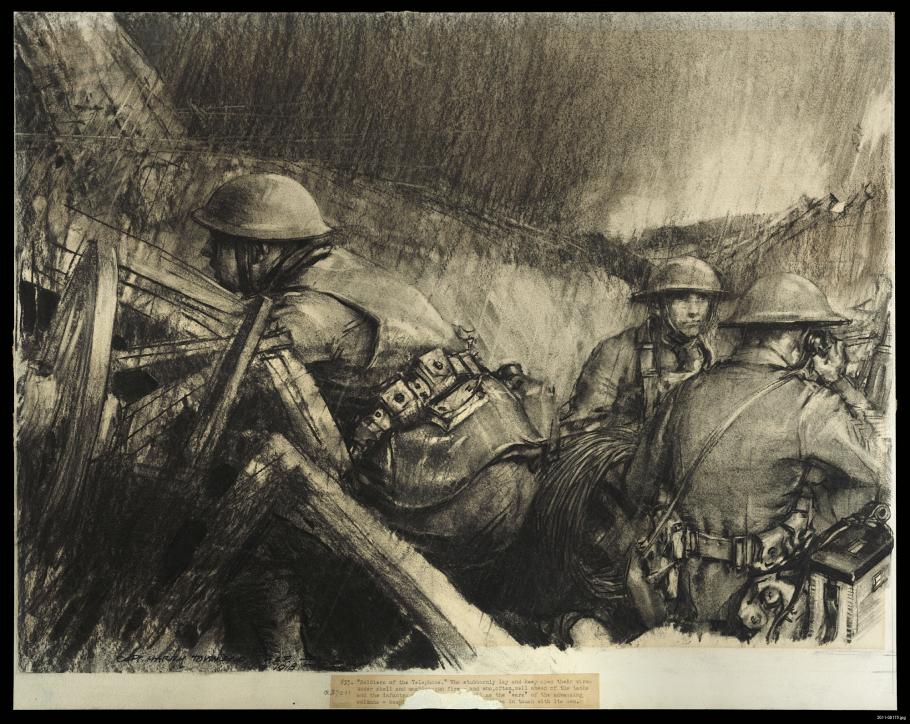

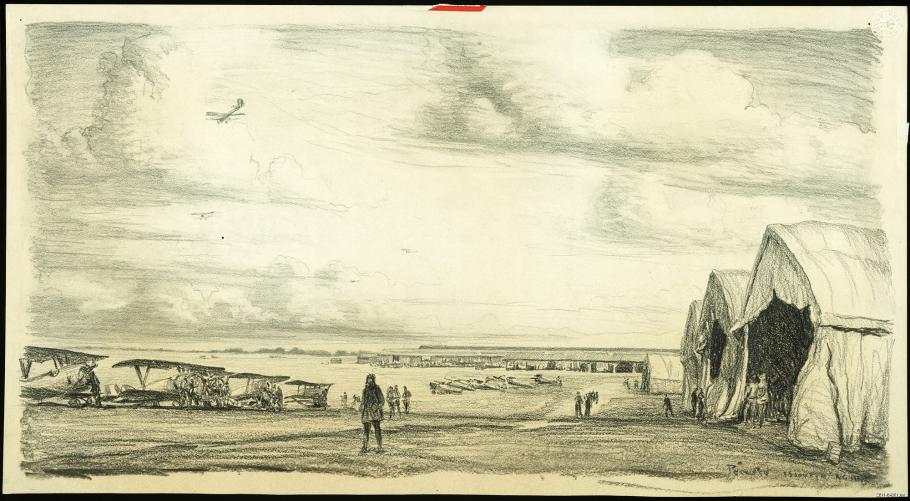

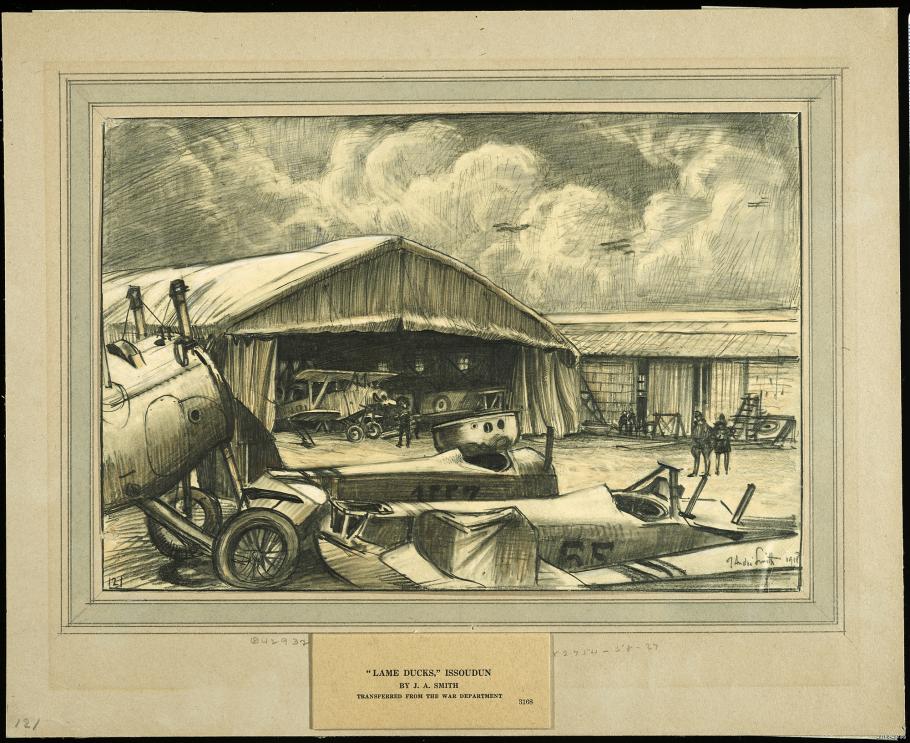

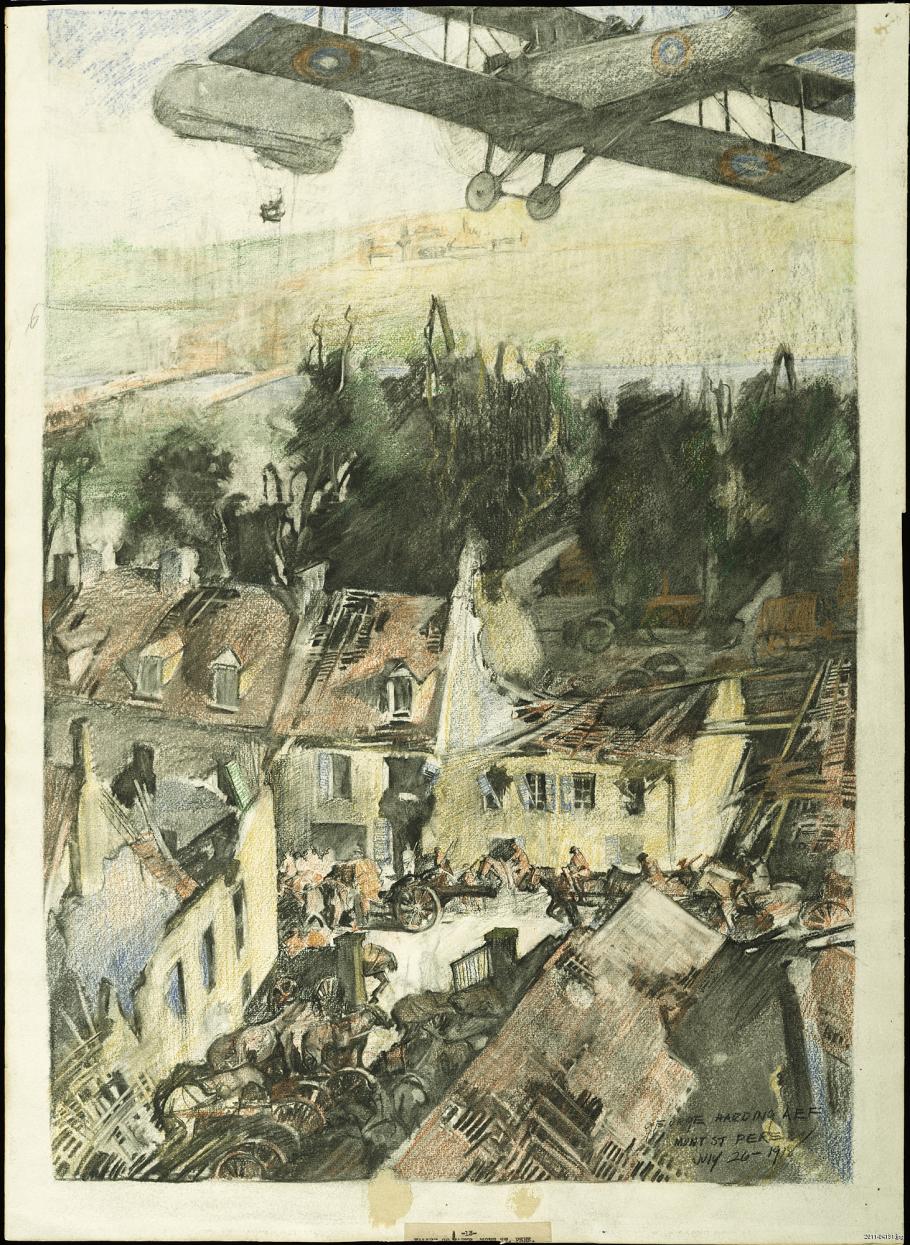

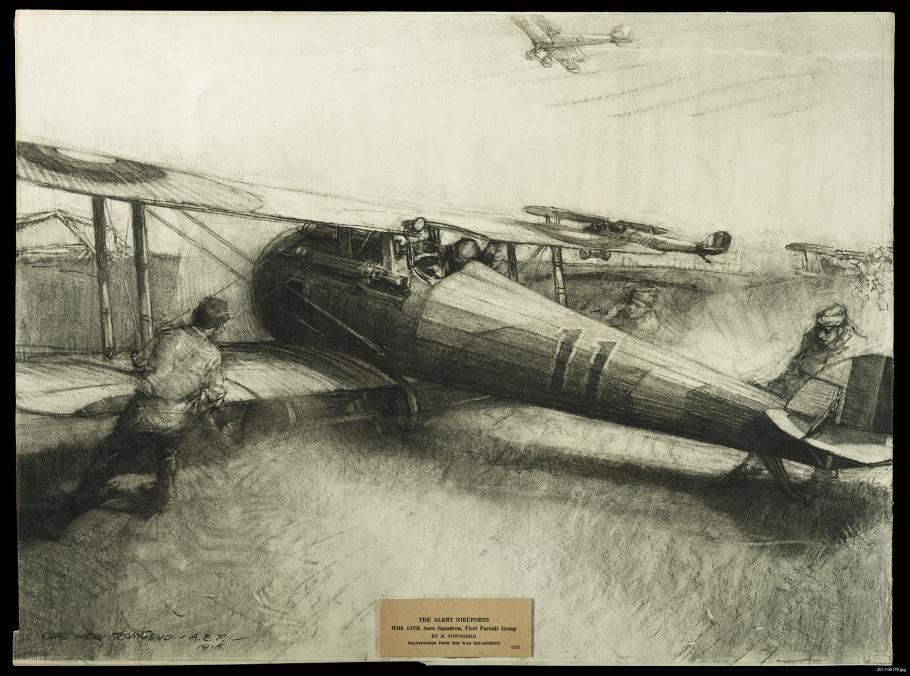

Heavy artillery, machine guns, tanks, motorized transport vehicles, high explosives, chemical weapons, airplanes, field radios and telephones, aerial reconnaissance cameras, and rapidly advancing medical technology and science were just a few of the areas that reshaped twentieth century warfare. The AEF artists documented the new military technology as thoroughly as every other aspect of the war.

After three years on the sidelines, the United States lagged far behind the latest technology and faced a monumental task equipping hundreds of thousands of new soldiers. U.S. industry was just beginning to gear up for this challenge when the AEF arrived in France. American troops frequently used European produced equipment, as is evident in much of the AEF artwork.

Harlequin Freighters by J. André Smith, Watercolor and charcoal, July 1918

Harlequin Freighters J. André Smith Watercolor and charcoal, July 1918

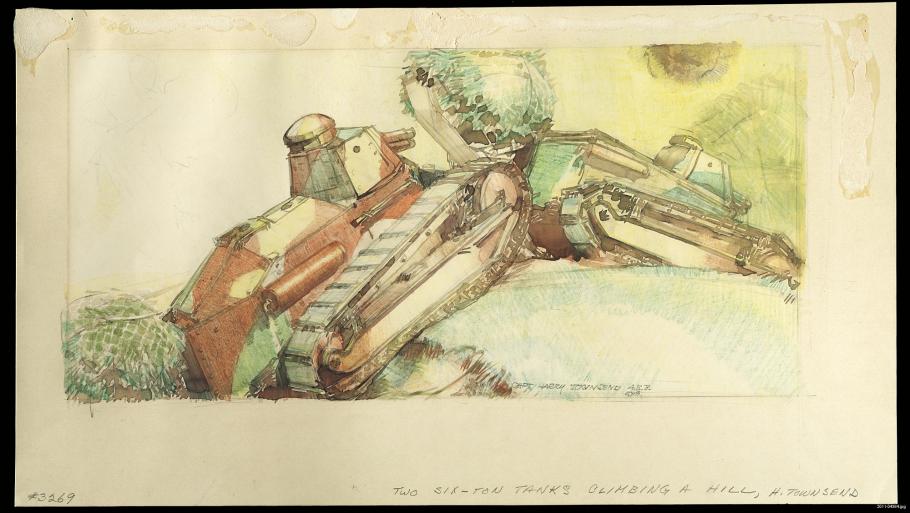

Two Six-Ton Tanks Climbing a Hill by Harry Everett Townsend, Watercolor and pastel on paper, 1918

Two Six-Ton Tanks Climbing a Hill Harry Everett Townsend Watercolor and pastel on paper, 1918

Left by the Hun, 152 mm Mortar by Harry Everett Townsend, Charcoal on card, 1918

Left by the Hun, 152 mm Mortar Harry Everett Townsend Charcoal on card, 1918

American Artillery and Machine Guns by George Matthews Harding, Charcoal and crayon on paper, July 24, 1918

American Artillery and Machine Guns George Matthews Harding Charcoal and crayon on paper, July 24, 1918

Gas Alert by Harry Everett Townsend, charcoal on paper, 1918

Gas Alert Harry Everett Townsend Charcoal on paper, 1918

Soldiers of the Telephone by Harry Everett Townsend, Charcoal on paper, 1918

Soldiers of the Telephone Harry Everett Townsend Charcoal on paper, 1918

The Flying Field, Issoudun by Ernest Clifford Peixotto, charcoal on board, August 1918

The Flying Field, Issoudun Ernest Clifford Peixotto Charcoal on board, August 1918

Forced Landing Near Neufchateau by Harry Everett Townsend | Charcoal on paper, 1918

Forced Landing Near Neufchateau Harry Everett Townsend Charcoal on paper, 1918

Lame Ducks, Issoudun by J. André Smith, pencil on paper, 1918

Lame Ducks, Issoudun J. André Smith Pencil on paper, 1918

Valley of the Marne at Mont St. Père by George Harding Matthews, charcoal, pastel, and sanguine on paper, July 26, 1918

Valley of the Marne at Mont St. Père George Harding Matthews Charcoal, pastel, and sanguine on paper, July 26, 1918

The Alert Nieuports by Harry Everett Townsend, charcoal on paper, 1918

The Alert Nieuports Harry Everett Townsend Charcoal on paper, 1918

94th Aero Squadron “Hat-in-the-Ring” Insignia

America’s first combat squadron was the 94th. Its famous “Hat-in-the Ring” insignia reflected the phrase used in April 1917 when the United States entered the war and was said to have now “thrown its hat in the ring.”

This example came from the aircraft of Harvey Weir Cook, who shot down 3 enemy aircraft and four observation balloons. The victories are represented with iron crosses inside the brim of the hat.

Gift of Donald Sieurin and D. Peter Sieurin

The AEF WWI war art collection currently is held by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Division of Armed Forces History, from which the artworks in this exhibition are on loan.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

NC Educators : please take a moment to share your needs and perspectives with us by completing the North Carolina Educator Information Survey

Copyright notice

This article is from Tar Heel Junior Historian , published for the Tar Heel Junior Historian Association by the North Carolina Museum of History. Used by permission of the publisher. For personal use and not for further distribution. Please submit permission requests for other uses directly to the museum editorial staff .

Is anything in this article factually incorrect? Please submit a comment.

Have a question or a suggestion about this entry contact ncpedia at https://www.ncpedia.org/contact, wwi: technology and the weapons of war.

by A. Torrey McLean Reprinted with permission from Tar Heel Junior Historian , Spring 1993. Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: WWI: Life on the Western Front

The popular image of World War I is soldiers in muddy trenches and dugouts, living miserably until the next attack. This is basically correct. Technological developments in engineering, metallurgy, chemistry, and optics had produced weapons deadlier than anything known before. The power of defensive weapons made winning the war on the western front all but impossible for either side.

When attacks were ordered, Allied soldiers went “over the top,” climbing out of their trenches and crossing no-man’s-land to reach enemy trenches. They had to cut through belts of barbed wire before they could use rifles, bayonets, pistols, and hand grenades to capture enemy positions. A victory usually meant they had seized only a few hundred yards of shell-torn earth at a terrible cost in lives. Wounded men often lay helpless in the open until they died. Those lucky enough to be rescued still faced horrible sanitary conditions before they could be taken to proper medical facilities. Between attacks,the snipers, artillery, and poison gas caused misery and death.

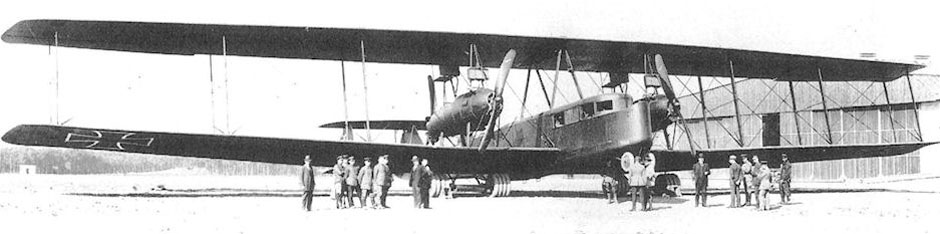

Airplanes , products of the new technology, were primarily made of canvas, wood, and wire. At first they were used only to observe enemy troops. As their effectiveness became apparent, both sides shot planes down with artillery from the ground and with rifles, pistols, and machine guns from other planes. In 1916, the Germans armed planes with machine guns that could fire forward without shooting off the fighters’ propellers. The Allies soon armed their airplanes the same way, and war in the air became a deadly business. These light, highly maneuverable fighter planes attacked each other in wild air battles called dogfights. Pilots who were shot down often remained trapped in their falling, burning planes, for they had no parachutes. Airmen at the front did not often live long. Germany also used its fleet of huge dirigibles, or zeppelins, and large bomber planes to drop bombs on British and French cities. Britain retaliated by bombing German cities.

Back on the ground, the tank proved to be the answer to stalemate in the trenches. This British invention used American-designed caterpillar tracks to move the armored vehicle equipped with machine guns and sometimes light cannon. Tanks worked effectively on firm, dry ground, in spite of their slow speed, mechanical problems, and vulnerability to artillery. Able to crush barbed wire and cross trenches, tanks moved forward through machine gun fire and often terrified German soldiers with their unstoppable approach.

Chemical warfare first appeared when the Germans used poison gas during a surprise attack in Flanders, Belgium, in 1915. At first, gas was just released from large cylinders and carried by the wind into nearby enemy lines. Later, phosgene and other gases were loaded into artillery shells and shot into enemy trenches. The Germans used this weapon the most, realizing that enemy soldiers wearing gas masks did not fight as well. All sides used gas frequently by 1918. Its use was a frightening development that caused its victims a great deal of suffering, if not death.

Both sides used a variety of big guns on the western front, ranging from huge naval guns mounted on railroad cars to short-range trench mortars. The result was a war in which soldiers near the front were seldom safe from artillery bombardment. The Germans used super–long-range artillery to shell Paris from almost eighty miles away. Artillery shell blasts created vast, cratered, moonlike landscapes where beautiful fields and woods had once stood.

At sea, submarines attacked ships far from port. In order to locate and sink German U-boats, British scientists developed underwater listening devices and underwater explosives called depth charges. Warships became faster and more powerful than ever before and used newly invented radios to communicate effectively. The British naval blockade of Germany, which was made possible by developments in naval technology, brought a total war to civilians. The blockade caused a famine that finally brought about the collapse of Germany and its allies in late 1918. Starvation and malnutrition continued to take the lives of German adults and children for years after the war.

The firing stopped on November 11, 1918, but modern war technology had changed the course of civilization. Millions had been killed, gassed, maimed, or starved. Famine and disease continued to rage through central Europe, taking countless lives. Because of rapid technological advances in every area, the nature of warfare had changed forever, affecting soldiers, airmen, sailors, and civilians alike.

A. Torrey McLean, a former United States Army officer who served in Vietnam, studied World War I for more than thirty years, personally interviewing a number of World War I veterans.

Additional resources:

"World War I in Photos." The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/static/infocus/wwi/introduction/ (accessed April 16, 2015).

Fitzgerald, Gerard J. 2008. "Chemical warfare and medical response during World War I." American Journal of Public Health. April 2008. 98(4): 611-625. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2376985/ . Corrected July 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2424079/

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Rumerman, Judy. "The U.S. Aircraft Industry Durin World War I." U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. #

"Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI." State Archives of North Carolina. N.C. Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm (accessed September 25, 2013).

"World War I." North Carolina Digital History. Learn NC. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newcentury/3.0

WWI: NC Digital Collections . NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit , State Archives of NC.

Image credits:

"Gas Mask. WWI. Used in France." NC Museum of History. Accession no. H.1999.1.406. http://collections.ncdcr.gov .

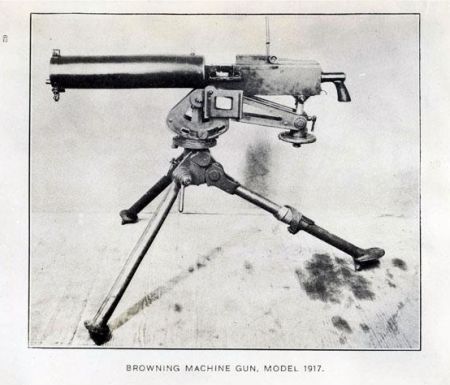

"Browning Machine Gun. Model 1917." 1918. NC Museum of History. Accession No. H.1918.31.9. http://collections.ncdcr.gov .

1 May 1993 | McLean, A. Torrey

World War I Technology

World War I was one of the defining events of the 20th century. From 1914 to 1918 conflict raged in much of the world and involved most of Europe, the United States, and much of the Middle East. In terms of technological history, World War I is significant because it marked the debut of many new types of weapons and was the first major war to “benefit” from technological advances in radio, electrical power, and other technologies.

World War I grew out of a variety of factors that had been building up throughout Europe in the preceding decades. During the later 1800s many European countries experienced a rise in nationalism. Nationalism, combined with growing industrial capabilities, led to military buildups and an increasingly tense political situation throughout the continent. Nations were increasingly nervous about what their neighbors might be planning. In response to this tension, England, France, and Russia (Italy would join in 1915 after the war was underway) formed the “Triple Entente” and aligned against Germany and Austria-Hungary. This was one of numerous alliances that divided Europe and made world war virtually impossible to avoid if one nation took action against another.

The flashpoint of the war is generally regarded as the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, during a state visit to Sarajevo. Austria-Hungry turned its anger towards Serbia, who, they believed, encouraged and abetted the assassination. In retaliation, Austria-Hungary invaded Serbia. On 29 July, in defense of Serbia, Tsar Nicholas II mobilized Russia’s armed forces to pressure Austria-Hungary. Three days later, on 1 August, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany honored its alliance with Austria-Hungary, and declared war on Russia. That same day, France, following its alliance with Russia, mobilized. Two days later, on 3 August, Germany declared war on France. Great Britain, as an ally of France, declared war on Germany on 4 August. Less then a month and a half after the assassination of the Archduke and within a week of the first military mobilizations the peoples of Europe were engulfed in war.

From the onset, those involved in the war were aware that technology would make a critical impact on the outcome. In 1915 British Admiral Jacky Fisher wrote, “The war is going to be won by inventions.” New weapons, such as tanks, the zeppelin, poison gas, the airplane, the submarine, and the machine gun, increased casualties, and brought the war to civilian populations. The Germans shelled Paris with long-range (60 miles or 100 kilometers) guns; London was bombed from the air for the first time by zeppelins.

World War I was also the first major war that was able to draw upon electrical technologies that had been in development at the turn of the century. Radio , for example, became essential for communications. The most important advance in radio was the transmission of voice rather than code, something the electron tube, as oscillator and amplifier, made possible. Electricity also made a huge impact on the war. Battleships, for example, might have electric signaling lamps, an electric helm indicator, electric fire alarms, remote control—from the bridge—of bulkhead doors, electrically controlled whistles, and remote reading of water level in the boilers. Electric power turned guns and turrets and raised ammunition from the magazines up to the guns. Searchlights—both incandescent and carbon-arc—became vital for nighttime navigation, for long-range daytime signaling, and for illuminating enemy ships in night engagements.

Submarines also became potent weapons. Although they had been around for years, it was during WWI that they began fulfilling their potential as a major threat. Unrestricted submarine warfare, in which German submarines torpedoed ships without warning—even civilian ships belonging to non-combatant nations such as the United States—resulted in the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915, killing 1,195 people. Finding ways to outfit ships to detect submarines became a major goal for the allies. Researchers determined that allied ships and submarines could be outfitted with sensitive microphones that could detect engine noise from enemy submarines. These underwater microphones played an important part in combatting the submarine threat. The Allies also developed sonar , but it came too close to the end of the war to offer much help.

The war, especially the brutality of trench warfare, brought death and disease on a scale people had never before experienced. During the 10-month-long Battle of Verdun in 1916, for example, as many as 1,000,000 people were killed. As the war dragged on, casualties increased, and the war became unpopular with ordinary people. Revolution in 1917 led to the end of Russian participation in the war and precipitated the Bolshevik regime. Just over a year later, a worker’s revolution in Germany forced the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II on 9 November 1918. With the militaristic Kaiser out of the way, Germany requested an armistice. Two days later, it took effect on the “Eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.” On 28 June 1919 German delegates signed the Treaty of Versailles and the war was officially over.

Although the war was over, its ramifications were far reaching. Technologically, great strides had been made in just about every area that might come into play during war. But the costs had been dear, and the end only temporary. Deaths from “The Great War” have been estimated at 10,000,000, and the end of the war itself, the Treaty of Versailles and its humiliating terms for Germany, laid the groundwork for World War II. The war was called “the war to end all wars,” and at the time that seemed possible. Unfortunately, it would prove untrue in less then a generation.

- Communications

- Radio communication

- Military applications

- World War I

- Aerospace engineering

- Land transportation

The Atlantic

World war i in photos: technology.

Industrialization brought massive changes to warfare during the Great War. Newly-invented killing machines begat novel defense mechanisms, which, in turn spurred the development of even deadlier technologies. Nearly every aspect of what we would consider modern warfare debuted on World War I battlefields.

When Europe's armies first marched to war in 1914, some were still carrying lances on horseback. By the end of the war, rapid-fire guns, aerial bombardment, armored vehicle attacks, and chemical weapon deployments were commonplace. Any romantic notion of warfare was bluntly shoved aside by the advent of chlorine gas, massive explosive shells that could have been fired from more than 20 miles away, and machine guns that spat out bullets like firehoses. Each side did its best to build on existing technology, or invent new methods, hoping to gain any advantage over the enemy. Massive listening devices gave them ears in the sky, armored vehicles made them impervious to small arms fire, tanks could (most of the time) cruise right over barbed wire and trenches, telephones and heliographs let them speak across vast distances, and airplanes gave them new platforms to rain death on each other from above. New scientific work resulted in more lethal explosives, new tactics made old offensive methods obsolete, and mass-produced killing machines made soldiers both more powerful and more vulnerable. On this 100-year anniversary, I've gathered photographs of the Great War from dozens of collections, some digitized for the first time, to try to tell the story of the conflict, those caught up in it, and how much it affected the world. Today's entry is part 3 of a 10-part series on World War I , which will be posted every Sunday until June 29. Come back next week for Part 4.

- Glossary of terms

- Privacy notice

- Accessibility

- World War I 1914 to 1918

- World War II 1939 to 1945

- Kokoda Track 1942 to 1943

- Burma-Thailand Railway and Hellfire Pass 1942 to 1943

- The Malayan Emergency 1948 to 1960

- Korean War 1950 to 1953

- The Indonesian Confrontation 1962 to 1966

- Vietnam War 1962 to 1975

- Gulf War 1990 to 1991

- Peacekeeping since 1947

- Biographies

- Oral histories

- Australians in wartime

- Great War memories

- Short films

- 3-nine-39 radio and video series

- National Service Scheme

- Veteran research

- Days of commemoration in Australia

- Event planning

- Personal commemorations

- Symbols of commemoration

- Memorial sites to visit

- Commemorative grants

- Anzac Day commemorative package

- Remembrance Day commemorative package

- Teaching resources

- Themes to explore

- Anzac Day Schools' Awards

- National History Challenge

- Stories of Service series

- Commemorative Activity Centre

Technology and equipment developed during World War I

The war drove scientific and technological initiative on an unprecedented scale. Innovation on both sides created more destructive and effective weapons. Communications, medicine and transportation were also advanced. But not all inventions achieved their intended goals.

A significant technological advance in World War I was the adoption and modification of aeroplanes for military use.

Early aircraft flown by Australian Flying Corps crews were unsuited to operations in the Middle East. When Lieutenant George Merz was let down by a faulty plane on 30 Jul 1915, he became the first Australian airman to die in the war. His unarmed Caudron G.3 was prone to engine problems. In the desert between Nasiriyeh and Basra, Merz and his passenger were murdered while trying to fix the plane.

Only 3 years later, Australian airmen were piloting the deadliest machines of the war. The last Australian airmen to die in the war were:

- Captain Thomas Baker of Adelaide, South Australia

- Lieutenant Arthur 'Jack' Palliser of Ulverstone, Tasmania

- 2nd Lieutenant Parker Symons of Moonta, South Australia

Captain Baker was an accomplished combat pilot. As part of No. 4 Squadron, he had brought down five German planes over 7 days.

All three men were killed on 4 November 1918 while escorting a squadron of British bombers back to base after a raid over Leuze. Their manoeuvrable Sopwith Snipe planes were shot down by the ace German pilot, Rittmeister Karl Bolle.

Tactics in aerial warfare developed throughout the war and included:

- artillery spotting

- battery ranging

- sector reconnaissance

- spotting for fire-effect

- dogfighting

Germany’s Baron Manfred von Richthofen , 'the Red Baron', was a well-known fighter pilot at the time. With 80 combat victories, he was the highest scoring pilot of the war. Von Richthofen was killed in action over France on 21 April 1918. At his funeral the next day, the Australian Flying Corps No. 3 Squadron fired a 12-gun salute.

Anti-aircraft weapons

At the start of World War I, dedicated anti-aircraft weapons were rare because few aircraft were used and their military use had not been proven. At first, Allied units were slow to provide dedicated anti-aircraft batteries. Germany initially led the way with motorised and horse-drawn guns controlled by the German Army Air Service.

Both sides quickly realised the value of planes during combat. Aircraft were used to undertake:

- offensive roles, such as bombing and artillery spotting

- reconnaissance operations, such as photography and surveillance

Combatting these offensive aerial roles needed more effective weapons that could:

- provide high rates of fire with specialised munitions

- be elevated towards the sky to shoot down aircraft

Scientific research to develop specialised munitions included:

- timed fuses that would detonate shells in the air, dispersing shrapnel to destroy aircraft

- incendiary shells that would ignite and set fire to airships and balloons

Other ways to prevent attacks from aircraft and airships were devised to:

- disrupt their passage, such as searchlights and web-like barriers of tethered balloons

- funnel aircraft into anti-aircraft firing range

Optical systems to track and range aircraft were important. Such advances helped to direct more accurate fire at incoming planes.

Both sides mounted machine guns on tripods as anti-aircraft measures. Although machine guns had a high rate of fire, they lacked the range of heavier calibre artillery munitions. Infantry on both sides sometimes used their rifles to shoot at low flying planes.

In 1917, Germany released a high velocity 88mm artillery gun as an anti-aircraft weapon. It allowed anti-aircraft gunners to more accurately calculate their bearings to shoot down Allied planes.

The British also developed some specialised anti-aircraft guns in different calibres. The best known was a variation of the ' pom-pom' gun .

By the end of the war, adoption of anti-aircraft tactics and weapons meant that:

- Americans claimed 58 aircraft shot down from 1917 onwards

- British and Australian forces claimed 340 aircraft shot

- French forces claimed 500 aircraft shot down

- German forces claimed over 1500 aircraft shot down

Airships and balloons

Military use of balloons peaked during World War I.

Newly developed dirigibles were more manoeuvrable and tougher than traditional hot air balloons. They were a constant sight above both sides' trenches on the Western Front.

Observation balloons:

- were floated or tethered to a great height behind the front lines

- carried observers who could spot enemy troop movements and collect intelligence

Ground artillery took advantage of the observer's increased range of sight from up high.

Anti-balloon warfare

Balloons became a target for both sides during the war. They were heavily defended by anti-aircraft guns on the ground and patrolling fighter aircraft.

Allied flying squadrons shot down German balloons with specially developed ammunition. This was an important tactic to prevent intelligence collection before major offensives. Incendiary bullets ignited the flammable gases in the balloons, causing them to erupt into fireballs.

The Buckingham incendiary bullet was developed for Allied airmen to use against German balloons.

Being an observer in a balloon or dirigible was risky business. You could be shot down by the enemy. Observation crews used parachutes long before they were adopted by airmen.

If a balloon came under attack, its occupant's only chance of survival would be to bail out and deploy a parachute as they left the basket. Sometimes their escape was too late, or their parachute caught alight.

Tethered observation balloons were used at sea, including by the Royal Australian Navy. Balloons were tethered to vessels, such as HMAS Parramatta , to help spot, pursue and sink enemy submarines.

The saying, 'The balloon goes up', means that something exciting or risky is beginning. During the war, the ascent of the enemy's observation balloon was nearly always followed by a barrage of shells.

Armoured cars and other vehicles

Armoured cars were widely used in the Middle East and on the Western Front. These cars were particularly useful for reconnaissance.

Even taxis played a role in the war. A fleet of taxis carried reinforcements to the forward areas in the First Battle of the Marne in 1914.

Where they could be used, motorised ambulances fulfilled a vital role. They provided rapid transportation for the wounded to hospitals.

Gas and anti-gas measures

Gas canisters and shells.

Gas was an effective tactic for clearing enemy forward positions during the war. Gases used included:

- mustard gas

When gas was first used in combat on the Western Front, it was stored in cylinders. When the wind was favourable, it was released to drift over enemy lines.

The gas from cylinders had a fairly short range in windy conditions and could prove lethal to the side using it if the wind changed direction.

At the Battle of Loos, the chlorine gas used against the Germans blew back into the faces of the British and Canadian troops. War correspondent Charles Bean wrote:

as a matter of fact gas in cloud form, emitted from cylinders, was never used directly against an Australian division

From 1916, gas was delivered in shells, which could be shot over a greater distance.

Anti-gas measures became increasingly sophisticated as the war progressed. In 1915, the British Army issued its troops with primitive cotton face pads soaked in sodium bicarbonate. The bicarb soda in the 'Black Veil' worked against a normal concentration of chlorine for about 5 minutes. By 1918, it was common to use filter respirators with charcoal or chemicals to neutralise the gas.

Gas alarm gong

When a gas attack seemed imminent or was in progress, the troops on the front would bang on a gas alarm gong to warn others. The gongs were usually hand made from metal rods or shell casings.

Sometimes strombus horns were sounded too.

A foldable anti-gas fan was designed to supply the troops with fresh air after a gas attack. It was used to clear gaseous residue that collected in shell-holes and craters.

Communication

The nature of trench warfare drove a need for more rapid communication between headquarters and the front lines. Conventional methods of communication at the time included:

- animals , such as pigeons and dogs

Telephones were widely used in the trenches, but their lines could easily be cut due to artillery damage or enemy sabotage.

The portable Morse code machine used by British forces enabled:

- communication between headquarters and the front line

- developments in field radios for forward observers to communicate with artillery units

The portable Fullerphone included both Morse code and speech facilities.

Early aircraft could drop message canisters down to ground forces. As planes became more sophisticated, so did their methods of communication.

A throat microphone described as 'a cap with a throat microphone and earpiece' was developed for hands-free communication. Pilots could receive orders from ground staff and pass on intelligence they had collected in the air.

[xxx **insert image of throat microphone from UK Archive's record - cat ref: AIR 10/100 - Image available from UK Archives booklet at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/first-world-war/telecommunications-in-war/ **]

<caption>Flying cap equipped with telephone headset and throat microphone, 1918 handbook, UK Archives ref. AIR 10/100</caption>

Wireless was used to send messages between ships on convoy duty or during battle.

Other important communications methods included:

- heliographs (sunlight flashed in mirrors)

- signalling flags

- signalling lamps (eg Begbie oil lamp and Lucas daylight electric lamp)

- simple tools for transmitting Morse code (eg a whistle)

Signalling flags, lamps and whistles carried the risk of being seen or heard by the enemy.

Some technical developments enabled the collection of intelligence from intercepted telecommunications. Wireless signals from German Zeppelins were collected at 'Direction Finding Stations' in Great Britain. This provided both the location and anticipated targets of Zeppelin attacks.

As a final measure, the complete 'cut off' of communications was another way to stall and disrupt a German attack.

Inventions and innovation

Artillery techniques.

Artillery was the most devastating weapon during the war.

The Allies put a lot of effort into locating and destroying German artillery positions. One technique was artillery sound ranging . This process used the sound of individual artillery pieces to work out the position and coordinates of enemy batteries.

Another technique was acoustic location , a forerunner to radar. An unusual device with large horns could amplify distant the sounds of enemy aircraft. The sound was monitored through headphones. Similar developments were initiated in marine acoustics to locate enemy submarines.

Flash spotting was important too. Ground troops would observe for the flash of an artillery piece being fired as another method of locating enemy batteries.

Kettering unmanned torpedo

The Americans developed the first pilotless flying weapon ('drone') in 1918.

The Kettering Bug had pre-set pneumatic and electrical controls to stabilise and guide it toward a target. After a set period, the controls closed an electrical circuit to stop the engine. This released the wings and caused the machine to plunge to earth, where 180 pounds (82kg) of explosive would detonate on impact.

The war ended before it could be used in combat.

Periscope rifle

The trench periscope rifle was invented in May 1915 by Lance Corporal William Beech, 2nd Battalion AIF. The gun allowed a soldier to take accurate aim and fire from down inside the trench, without exposing himself to fire from enemy trenches or snipers.

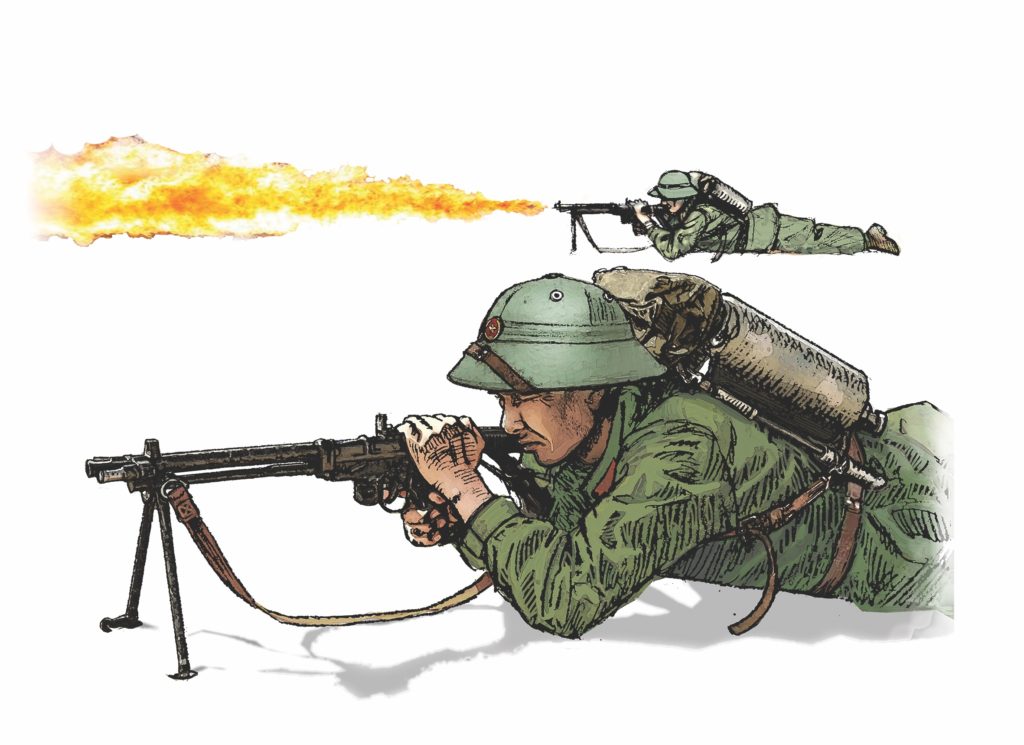

Flamethrower

The Germans improved the flamethrower , a brutal infantry weapon. Its operator could send a jet of flame many metres towards enemy troops. Inside the device, a cylinder of oil was being pressurised by a propellant, such as carbon dioxide or nitrogen.

Hand grenades

The hand grenade (called 'bombs' at the time) became more advanced and lethal during the war.

Initially, the Germans had the most advanced grenades. By the end of the war, the British and French forces had developed more effective:

- fragmentation and concussion grenades

- 'smoke' grenades to conceal movement

- coloured smoke grenades for signalling

- gas grenades

- rifle launched grenades

Sometimes the troops themselves took the initiative to make grenades. The AIF’s ' jam tin' bomb was an empty tin or two packed with explosives, shrapnel and a fuse.

Medical advances

No one was prepared for the tremendous physical impact that modern artillery, gas and machine guns — and the stress of battle — would have on the men.

At first, armies had very basic arrangements in place for moving and treating wounded men. Usually, a man would be carried away from the battle by soldiers, or be placed on a stretcher or a horse or mule-drawn cart. Private Simpson and his donkey is one early Australian example of using donkeys to transport for the wounded.

Military medical facilities were also poorly equipped to treat:

- loss of blood

- open wounds

Before the age of antibiotics, medical officers were unable to kill harmful bacteria, such as gangrene-causing Clostridium perfringens . Many patients either died from the infection or underwent salvage amputations of gangrenous limbs.

Transport and treatment improvements

Three significant medical advances sprang from the experience of mass casualties in World War I:

- specialised anaesthetists

The methods of evacuating and treating wounded that evolved so quickly during World War I are the forerunners of the technologically advanced tools used in modern military medicine.

The Carrel-Dakin method to wash open wounds with a solution of sodium hypochlorite was a major breakthrough. It helped to prevent the spread of deadly bacteria.

Other major developments included:

- anaesthetic to reduce pain, such as nitrous oxide

- anti-coagulants to store blood in 'blood banks'

Medical treatment became more hygienic and less traumatic. Supplies of blood saved countless wounded men from bleeding to death.

Specialist anaesthetist posts were introduced to casualty clearing stations behind the lines by late 1917. This enabled specialist medical officers to help prevent shock during surgery by focusing on:

- blood transfusions

- pain relief

- resuscitation

The British Army trained 200 nurses in anaesthesia in late 1917. They were posted to the casualty clearing stations in 1918.

Post-war improvements

The terrible effects of modern weapons on the human body were addressed as the war went on.

Men who suffered tremendous disfigurements were helped with the development of:

- maxillofacial reconstructive surgery

- use of prostheses as facial masks and limb replacements

Common conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) , were little understood at the time. The psychological impact of the war was called 'shell shock'. It was known that loud explosions, such as fireworks, could trigger a reaction in some returned service men and women.

Both Navy and merchant navy ships helped the Allies to win the war against Germany.

For the first 6 months of the war, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) fleet operated under one command. After that, its sailors and ships served with different squadrons around the world - as requested by the British Admiralty.

RAN ships and submarines worked with the Grand Fleet and other Allied navies to:

- search for enemy raiders over thousands of miles of ocean

- carry out anti-submarine warfare

- escort convoys of merchant ships carrying supplies and troops

- do long routine patrols, essential to the blockade of Germany and enemy ports

- experiment with the use of aircraft at sea

- sweep for mines in home waters

Australian ships could be found around the world during the war. From South Pacific outposts to the freezing North Atlantic Ocean, the waters off Africa, the Caribbean off Mexico’s west coast, navigating New Guinean rivers, patrolling the Mediterranean and in the waters surrounding Australia.

Ultimately, the British Grand Fleet, which included Australian ships, played a vital role in the defeat of Germany. Not by destroying the Imperial German Navy, but by preventing the German fleet from reaching open waters and making possible the Allied blockade of Germany.

The Allies’ ability to maintain a naval blockade of Germany crippled Germany’s imports and industry. It was a significant factor in the Allied victory.

Naval developments

More powerful battleships could carry the largest guns. The Dreadnought class of battleships gave both sides tremendous destructive capability.

- ammunition with greater firing range

- naval fire control systems in Dreadnought class battleships for added lethality

- steam turbines for a faster more agile battleship

Small torpedo boats were developed to attack and harass much larger naval and merchant navy vessels.

Merchant navy

Both sides used converted merchant vessels to attack or defend shipping.

German commerce raiders were converted civilian ships carrying disguised weapons. Their apparent vulnerability often lured enemy vessels towards them. Armed merchant cruisers were converted civilian ships equipped with guns.

The German raider, Möwe, sank 34 merchant ships. The German raider, Wolf, sank 12 ships and laid sea mines in the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Tasman Sea in 1917. The mines sank three ships in Australian and New Zealand waters.

The heaviest ships engaged in commerce raiding were German light cruisers. They attacked Allied shipping in the Atlantic, Caribbean, Pacific and Indian oceans. The SMS Emden sank Allied vessels before being sunk by HMAS Sydney

The British and French navies also used armed merchant vessels. The British 'Q' ships were used in anti-submarine warfare.

Submarines played a significant role during World War I.

The Allied and German navies used submarines against enemy warships from the outset of the war.

Australia’s submarines, AE1 and AE2, served the British Admiralty from the start of the war. AE1 tragically became the first Allied submarine los in the war. It disappeared with all 35 British and Australian crewmen on 14 September 1914.

Great feats of submariners' bravery were celebrated early in the war.

British Captain Norman Holbrook led the submarine B11 on a high-risk mission through the Dardanelles on 13 December 1914. After a tortuous passage through the narrow waterway, the crew sank the Turkish battleship, Mesudiye, and then escaped.

Australia’s AE2 also traversed the Dardanelles . The crew damaged an Ottoman gunboat before the submarine was attacked by a Turkish ship and scuttled on 30 April 1915. They were all taken prisoner.

Submarine warfare

Submarine warfare was almost polite at first. Submarine crews tried to obey the internationally agreed cruiser rules . For example, a German U-boat would surface and allow the crew to abandon a ship before it was sunk. But this operation was difficult and risky for submarines, and it was soon replaced with more aggressive tactics.

In 1915, the Germans declared unrestricted submarine warfare on Allied and neutral vessels. The policy aimed to isolate Britain and starve its people of resources.

The infamous sinking of the RMS Lusitania by Germany's U-20 was an example of this policy. An angry response from the United States made Germany stop the practice between September 1915 and February 1917.

In response to the Allied blockade of German sea ports, Germany escalated its submarine operations from 20 U-boats in 1914 to 140 by 1917 when the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed in full force.

Anti-submarine strategies

During the war, Allied forces initiated U-boat countermeasures, such as:

- warship escorts ordered for convoys of merchant ships

- heavily armed Q-ships disguised as merchant ships

- airborne reconnaissance to spot U-boats

The Royal Navy used heavily armed merchant ships called Q-ships to lure U-boats into making a surface attack. When the U-boat approached, the Q-ship would unleash its superior concealed guns. Deceitful tactics included staging an abandonment, with some crew visibly 'leaving' the ship in lifeboats.

The Allies also tried airborne reconnaissance to spot U-boats, with varying success. Spotters in airplanes or tethered balloons were used to this end.

Anti-submarine technology

The Allies developed other anti-submarine measures, including:

- depth charges

- detection equipment

- underwater barriers

Australian ships were at the forefront of early experiments to launch military planes at sea . The idea of operating aircraft from platforms on battle cruisers and light cruisers became reality.

On 1 June 1918, a Sopwith Camel scout (fighter) aircraft flown from the deck of HMAS Sydney intercepted two German reconnaissance aircraft. One was badly damaged and reportedly went into a tail spin.

Tanks and land vehicles

The tank was developed in response to the stalemate of trench warfare on the Western Front. German trenches seemed impenetrable to Allied infantry, with a combination of:

- barbed wire

- overlapping arcs of machine-gun fire and rifle fire from German infantry

- strong-points and concrete reinforced pillboxes on the Hindenburg Line

- rapid counter-attacks by fresh reinforcements

Attacking forces suffered horrendous casualties as soon as they left the protection of their own trenches. Even if an Allied assault met with early success, the costly gains were often held only fleetingly.

Tank design combined:

- all-terrain capability of the tank's caterpillar tracks

- armour to protect it from machine gun and rifle fire

In April 1917, the First Battle of Bullecourt left the Australian troops suspicious about the capability of tanks. But further developments made tanks a potent weapon for the Allies.

Tanks were used with success at:

- Battle of Arras in April and May 1917

- Battle of Hamel in July 1918

- Battle of Amiens in August 1918

Anti-tank tactics

Germany was the first to develop anti-tank warfare to combat the tanks being developed by Allies. On the battlefield, tanks were susceptible to:

- German artillery firing directly over their sights

- anti-tank ditches

- anti-tank 'traps'

- anti-tank rifles (Mauser 13mm)

- fragmentation

- strong-point

Further reading

- Impact of aircraft in World War I

- Tanks and armoured vehicles

- Armoured cars at Aleppo

- Transport and supply during the First World War

- A fleet of taxis and the Battle of Marne

- The submarine war

- Anti-aircraft warfare

- Anti-submarine warfare

- Armoured vehicles

- Chemical warfare

- Communications

- Inventions and innovations

- Personal protective equipment

- Sound ranging techniques

- Technology and equipment

- World War I 1914-1918

Last updated: 13 April 2021

Cite this page

Monthly updates on new content, free resources and commemorations.

We'll protect your details in line with our Privacy Policy. Learn about our newsletter .

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Weapons of World War I: Machine Guns, Mortars, and More

Humans proved themselves remarkably ingenuous and adaptable when it came to finding new ways to maim and kill during the First World War . The list below explores many of the weapons used to produce millions of casualties in four short years.

Table of Contents

Recommended for you

Weapons of world war ii.

Weapons Check | Walther P-38

North Vietnam’s Type 74 Flamethrower

All nations used more than one type of firearm during the First World War. The rifles most commonly used by the major combatants were, among the Allies, the Lee-Enfield .303 (Britain and Commonwealth), Lebel and Berthier 8mm (France), Mannlicher–Carcano M1891, 6.5mm (Italy), Mosin–Nagant M1891 7.62 (Russia), and Springfield 1903 .30–06 (USA). The Central Powers employed Steyr–Mannlicher M95 (Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria), Mauser M98G 7.92mm (Germany), and Mauser M1877 7.65mm (Turkey). The American Springfield used a bolt-action design that so closely copied Mauser’s M1989 that the US Government had to pay a licensing fee to Mauser, a practice that continued until America entered the war.

Back to top

WW1 Machine guns

Most machine guns of World War 1 were based on Hiram Maxim’s 1884 design. They had a sustained fire of 450–600 rounds per minute, allowing defenders to cut down attacking waves of enemy troops like a scythe cutting wheat. There was some speculation that the machine gun would completely replace the rifle. Contrary to popular belief, machine guns were not the most lethal weapon of the Great War. That dubious distinction goes to the artillery.

“Military science develops so rapidly in times of actual war that the weapons of today soon is (sic) discarded and something better taken up.” Attributed to a German agent in Rotterdam in 1915 news stories

WW1 Flamethrowers

Reports of infantry using some sort of flame-throwing device can be found as far back as ancient China. During America’s Civil War some Southern newspapers claimed Abraham Lincoln had observed a test of such a weapon. But the first recorded use of hand-held flamethrowers in combat was on February 26, 1915, when the Germans deployed the weapon at Malancourt, near Verdun. Tanks carried on a man’s back used nitrogen pressure to spray fuel oil, which was ignited as it left the muzzle of a small, hand-directed pipe. Over the course of the war, Germany utilized 3,000 Flammenwerfer troops; over 650 flamethrower attacks were made. The British and French both developed flame-throwing weapons but did not make such extensive use of them.

WW1 Mortars

Mortars of World War I were far advanced beyond their earlier counterparts. The British introduced the Stokes mortar design in 1915, which had no moving parts and could fire up to 22 three-inch shells per minute, with a range of 1,200 yards. The Germans developed a mortar ( minenwerfer , or “mine thrower”) that had a 10-inch barrel and fired shells loaded with metal balls.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

WW1 Artillery

The 20th century’s most significant leap in traditional weapons technology was the increased lethality of artillery due to improvements in gun design, range and ammunition ‚—a fact that was all too clear in the Great War, when artillery killed more people than any other weapon did. Some giant guns could hurl projectiles so far that crews had to take into account the rotation of the earth when plotting their fire. Among smaller field guns, the French 75mm cannon developed a reputation among their German opponents as the “Devil Gun.” French commanders claimed it won the war. French 75 mm field guns also saw action in the Second World War, during which some were modified by the Germans into anti-tank guns with limited success.

WW1 Poison gas

On April 22, 1915, German artillery fired cylinders containing chlorine gas in the Ypres area, the beginning of gas attacks in the First World War. Other nations raced to create their own battlefield gases, and both sides found ways to increase the severity and duration of the gases they fired on enemy troop concentrations. Chlorine gas attacked the eyes and respiratory system; mustard gas did the same but also caused blistering on any exposed skin. Comparatively few men died from gas. Most returned to active service after treatment, but the weapon incapacitated large numbers of troops temporarily and spread terror wherever it was used. The use of poison gas was outlawed by international law following the war, but it has been used in some later conflicts, such as the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88).

Ideas for “land battleships” go back at least as far as the Medieval Era; plans for one are included among the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. The long-sought weapon became reality during the First World War. “Tank” was the name the British used as they secretly developed the weapon, and it stuck, even though the French simultaneously developed the Renault FT light armored vehicle, which had a traversable turret, unlike the British designs. (Various reasons have been given for choosing the name “tank,” from shells that were shaped like water-carriers to the British concealing construction of their secret weapon under the guise of making irrigation tanks for sale to Russia.) The first British tank (“Little Willie”) weighed approximately 14 tons, had a top speed of three mph, and broke down frequently. Improved tanks were deployed during the war, but breakdowns remained a significant problem that led many commanders to believe the tank would never play a major role in warfare. The Germans developed an armored fighting vehicle only in response to the British and French deploying tanks. The only German design of the war, A7V, was an awe-inspiring but cumbersome beast that resembled a one-story building on treads.

Initially, tanks were doled out in small numbers to support infantry attacks. The Battle of Cambrai , November 20, 1917, is generally regarded as the first use of massed tank formations; the British deployed over 470 of them for that battle. However, the French had already successfully employed 76 tanks during the battle at Malmaison on October 23, 1917, one of the most impressive French victories of the Great War.

WW1 Aircraft

The air war of World War I continues to fascinate as much as it did at the time. This amazing new technology proved far more useful than most military and political leaders anticipated. Initially used only for reconnaissance, before long planes were armed with machine guns. Once Anthony Fokker developed a method to synchronize a machine gun’s fire with the rotation of the propeller, the airplane became a true weapon.

Early aircraft were flimsy, kite-like designs of lightweight wood, fabric and wires. The 80–120 horsepower engines used in 1914 produced top speeds of 100 mph or less; four years later speed had nearly doubled. Protection for pilots remained elusive, but most pilots disdained carrying parachutes regardless. Over the course of the war multi-engine bombers were developed, the largest being Germany’s “Giant,” the Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI , with a wingspan of 138 feet and four engines. It had a range of about 500 miles and a bomb-load capacity of 4,400 lbs., although in long-range operations, such as bombing London, Giants carried only about half that much.

WW1 Submarines

Britain, France, Russia and the United States of America had all developed submarine forces before Germany began development of its Unterzeeboats (Undersea boats, or U-boats) in 1906, but during World War I submarines came to be particularly associated with the Imperial German Navy, which used them to try to bridge the gap in naval strength it suffered compared to Britain’s Royal Navy. Longer-range U-boats were developed and torpedo quality improved during the war. Submarines could strike unseen from beneath the waves with torpedoes but also surfaced to use their deck gun. One tactic was for the low-riding subs to slip in among a convoy of ships while surfaced, attack and dive. An unsuccessful post-war effort was made to ban submarine warfare, as was done with poison gas.

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Seminoles Taught American Soldiers a Thing or Two About Guerrilla Warfare

During the 1835–42 Second Seminole War and as Army scouts out West, these warriors from the South proved formidable.

An SAS Rescue Mission Mission Gone Wrong

When covert operatives went into Italy to retrieve prisoners of war, little went according to plan.

- Advanced Search

International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Welcome to 1914-1918-online.

“1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War” is an English-language virtual reference work on the First World War. Read More

Kemal, Mustafa (Atatürk)

By erik-jan zürcher, konoe, fumimaro, by gerhard krebs, ecumenical patriarchate of constantinople, by dimitris kamouzis, by malte könig, fall of baghdad, by christoph herzog, max, adolphe, by laurence van ypersele, west africa, by george n. njung, by lucy betteridge-dyson, caucasus front, by tigran martirosyan, czechoslovak-hungarian border conflict, by aliaksandr piahanau.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

World War I

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 10, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

World War I, also known as the Great War, started in 1914 after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. His murder catapulted into a war across Europe that lasted until 1918. During the four-year conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire (the Central Powers) fought against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan and the United States (the Allied Powers). Thanks to new military technologies and the horrors of trench warfare, World War I saw unprecedented levels of carnage and destruction. By the time the war was over and the Allied Powers had won, more than 16 million people—soldiers and civilians alike—were dead.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Tensions had been brewing throughout Europe—especially in the troubled Balkan region of southeast Europe—for years before World War I actually broke out.

A number of alliances involving European powers, the Ottoman Empire , Russia and other parties had existed for years, but political instability in the Balkans (particularly Bosnia, Serbia and Herzegovina) threatened to destroy these agreements.

The spark that ignited World War I was struck in Sarajevo, Bosnia, where Archduke Franz Ferdinand —heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire—was shot to death along with his wife, Sophie, by the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914. Princip and other nationalists were struggling to end Austro-Hungarian rule over Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Great War

Two-Night Event, The Great War Begins Monday, May 27 at 8/7c and streams the next day

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand set off a rapidly escalating chain of events: Austria-Hungary , like many countries around the world, blamed the Serbian government for the attack and hoped to use the incident as justification for settling the question of Serbian nationalism once and for all.

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Because mighty Russia supported Serbia, Austria-Hungary waited to declare war until its leaders received assurance from German leader Kaiser Wilhelm II that Germany would support their cause. Austro-Hungarian leaders feared that a Russian intervention would involve Russia’s ally, France, and possibly Great Britain as well.

On July 5, Kaiser Wilhelm secretly pledged his support, giving Austria-Hungary a so-called carte blanche, or “blank check” assurance of Germany’s backing in the case of war. The Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary then sent an ultimatum to Serbia, with such harsh terms as to make it almost impossible to accept.

World War I Begins

Convinced that Austria-Hungary was readying for war, the Serbian government ordered the Serbian army to mobilize and appealed to Russia for assistance. On July 28, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the tenuous peace between Europe’s great powers quickly collapsed.

Within a week, Russia, Belgium, France, Great Britain and Serbia had lined up against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and World War I had begun.

The Western Front

According to an aggressive military strategy known as the Schlieffen Plan (named for its mastermind, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen ), Germany began fighting World War I on two fronts, invading France through neutral Belgium in the west and confronting Russia in the east.

On August 4, 1914, German troops crossed the border into Belgium. In the first battle of World War I, the Germans assaulted the heavily fortified city of Liege , using the most powerful weapons in their arsenal—enormous siege cannons—to capture the city by August 15. The Germans left death and destruction in their wake as they advanced through Belgium toward France, shooting civilians and executing a Belgian priest they had accused of inciting civilian resistance.

First Battle of the Marne

In the First Battle of the Marne , fought from September 6-9, 1914, French and British forces confronted the invading German army, which had by then penetrated deep into northeastern France, within 30 miles of Paris. The Allied troops checked the German advance and mounted a successful counterattack, driving the Germans back to the north of the Aisne River.

The defeat meant the end of German plans for a quick victory in France. Both sides dug into trenches , and the Western Front was the setting for a hellish war of attrition that would last more than three years.

Particularly long and costly battles in this campaign were fought at Verdun (February-December 1916) and the Battle of the Somme (July-November 1916). German and French troops suffered close to a million casualties in the Battle of Verdun alone.

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

World War I Books and Art

The bloodshed on the battlefields of the Western Front, and the difficulties its soldiers had for years after the fighting had ended, inspired such works of art as “ All Quiet on the Western Front ” by Erich Maria Remarque and “ In Flanders Fields ” by Canadian doctor Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae . In the latter poem, McCrae writes from the perspective of the fallen soldiers:

Published in 1915, the poem inspired the use of the poppy as a symbol of remembrance.

Visual artists like Otto Dix of Germany and British painters Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash and David Bomberg used their firsthand experience as soldiers in World War I to create their art, capturing the anguish of trench warfare and exploring the themes of technology, violence and landscapes decimated by war.

The Eastern Front

On the Eastern Front of World War I, Russian forces invaded the German-held regions of East Prussia and Poland but were stopped short by German and Austrian forces at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August 1914.

Despite that victory, Russia’s assault forced Germany to move two corps from the Western Front to the Eastern, contributing to the German loss in the Battle of the Marne.

Combined with the fierce Allied resistance in France, the ability of Russia’s huge war machine to mobilize relatively quickly in the east ensured a longer, more grueling conflict instead of the quick victory Germany had hoped to win under the Schlieffen Plan .

Russian Revolution

From 1914 to 1916, Russia’s army mounted several offensives on World War I’s Eastern Front but was unable to break through German lines.

Defeat on the battlefield, combined with economic instability and the scarcity of food and other essentials, led to mounting discontent among the bulk of Russia’s population, especially the poverty-stricken workers and peasants. This increased hostility was directed toward the imperial regime of Czar Nicholas II and his unpopular German-born wife, Alexandra.

Russia’s simmering instability exploded in the Russian Revolution of 1917, spearheaded by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks , which ended czarist rule and brought a halt to Russian participation in World War I.

Russia reached an armistice with the Central Powers in early December 1917, freeing German troops to face the remaining Allies on the Western Front.

America Enters World War I

At the outbreak of fighting in 1914, the United States remained on the sidelines of World War I, adopting the policy of neutrality favored by President Woodrow Wilson while continuing to engage in commerce and shipping with European countries on both sides of the conflict.

Neutrality, however, it was increasingly difficult to maintain in the face of Germany’s unchecked submarine aggression against neutral ships, including those carrying passengers. In 1915, Germany declared the waters surrounding the British Isles to be a war zone, and German U-boats sunk several commercial and passenger vessels, including some U.S. ships.

Widespread protest over the sinking by U-boat of the British ocean liner Lusitania —traveling from New York to Liverpool, England with hundreds of American passengers onboard—in May 1915 helped turn the tide of American public opinion against Germany. In February 1917, Congress passed a $250 million arms appropriations bill intended to make the United States ready for war.

Germany sunk four more U.S. merchant ships the following month, and on April 2 Woodrow Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany.

Gallipoli Campaign

With World War I having effectively settled into a stalemate in Europe, the Allies attempted to score a victory against the Ottoman Empire, which entered the conflict on the side of the Central Powers in late 1914.

After a failed attack on the Dardanelles (the strait linking the Sea of Marmara with the Aegean Sea), Allied forces led by Britain launched a large-scale land invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula in April 1915. The invasion also proved a dismal failure, and in January 1916 Allied forces staged a full retreat from the shores of the peninsula after suffering 250,000 casualties.

Did you know? The young Winston Churchill, then first lord of the British Admiralty, resigned his command after the failed Gallipoli campaign in 1916, accepting a commission with an infantry battalion in France.

British-led forces also combated the Ottoman Turks in Egypt and Mesopotamia , while in northern Italy, Austrian and Italian troops faced off in a series of 12 battles along the Isonzo River, located at the border between the two nations.

Battle of the Isonzo

The First Battle of the Isonzo took place in the late spring of 1915, soon after Italy’s entrance into the war on the Allied side. In the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, also known as the Battle of Caporetto (October 1917), German reinforcements helped Austria-Hungary win a decisive victory.

After Caporetto, Italy’s allies jumped in to offer increased assistance. British and French—and later, American—troops arrived in the region, and the Allies began to take back the Italian Front.

World War I at Sea

In the years before World War I, the superiority of Britain’s Royal Navy was unchallenged by any other nation’s fleet, but the Imperial German Navy had made substantial strides in closing the gap between the two naval powers. Germany’s strength on the high seas was also aided by its lethal fleet of U-boat submarines.

After the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, in which the British mounted a surprise attack on German ships in the North Sea, the German navy chose not to confront Britain’s mighty Royal Navy in a major battle for more than a year, preferring to rest the bulk of its naval strategy on its U-boats.

The biggest naval engagement of World War I, the Battle of Jutland (May 1916) left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, and Germany would make no further attempts to break an Allied naval blockade for the remainder of the war.

World War I Planes

World War I was the first major conflict to harness the power of planes. Though not as impactful as the British Royal Navy or Germany’s U-boats, the use of planes in World War I presaged their later, pivotal role in military conflicts around the globe.

At the dawn of World War I, aviation was a relatively new field; the Wright brothers took their first sustained flight just eleven years before, in 1903. Aircraft were initially used primarily for reconnaissance missions. During the First Battle of the Marne, information passed from pilots allowed the allies to exploit weak spots in the German lines, helping the Allies to push Germany out of France.

The first machine guns were successfully mounted on planes in June of 1912 in the United States, but were imperfect; if timed incorrectly, a bullet could easily destroy the propeller of the plane it came from. The Morane-Saulnier L, a French plane, provided a solution: The propeller was armored with deflector wedges that prevented bullets from hitting it. The Morane-Saulnier Type L was used by the French, the British Royal Flying Corps (part of the Army), the British Royal Navy Air Service and the Imperial Russian Air Service. The British Bristol Type 22 was another popular model used for both reconnaissance work and as a fighter plane.

Dutch inventor Anthony Fokker improved upon the French deflector system in 1915. His “interrupter” synchronized the firing of the guns with the plane’s propeller to avoid collisions. Though his most popular plane during WWI was the single-seat Fokker Eindecker, Fokker created over 40 kinds of airplanes for the Germans.

The Allies debuted the Handley-Page HP O/400, the first two-engine bomber, in 1915. As aerial technology progressed, long-range heavy bombers like Germany’s Gotha G.V. (first introduced in 1917) were used to strike cities like London. Their speed and maneuverability proved to be far deadlier than Germany’s earlier Zeppelin raids.

By the war’s end, the Allies were producing five times more aircraft than the Germans. On April 1, 1918, the British created the Royal Air Force, or RAF, the first air force to be a separate military branch independent from the navy or army.

Second Battle of the Marne

With Germany able to build up its strength on the Western Front after the armistice with Russia, Allied troops struggled to hold off another German offensive until promised reinforcements from the United States were able to arrive.

On July 15, 1918, German troops launched what would become the last German offensive of the war, attacking French forces (joined by 85,000 American troops as well as some of the British Expeditionary Force) in the Second Battle of the Marne . The Allies successfully pushed back the German offensive and launched their own counteroffensive just three days later.

After suffering massive casualties, Germany was forced to call off a planned offensive further north, in the Flanders region stretching between France and Belgium, which was envisioned as Germany’s best hope of victory.

The Second Battle of the Marne turned the tide of war decisively towards the Allies, who were able to regain much of France and Belgium in the months that followed.

The Harlem Hellfighters and Other All-Black Regiments

By the time World War I began, there were four all-Black regiments in the U.S. military: the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. All four regiments comprised of celebrated soldiers who fought in the Spanish-American War and American-Indian Wars , and served in the American territories. But they were not deployed for overseas combat in World War I.

Blacks serving alongside white soldiers on the front lines in Europe was inconceivable to the U.S. military. Instead, the first African American troops sent overseas served in segregated labor battalions, restricted to menial roles in the Army and Navy, and shutout of the Marines, entirely. Their duties mostly included unloading ships, transporting materials from train depots, bases and ports, digging trenches, cooking and maintenance, removing barbed wire and inoperable equipment, and burying soldiers.