Spring and Summer Applications are Now Open

Lorem Ipsum

Assessments for Schools

CTD helps schools understand and use data to inform instruction, measure growth for advanced learners, and plan for programming.

Learn more about assessment options

Gifted Education Resources

View resources

Professional Learning

Practical, timely topics to help teachers and administrators effectively identify and meet the needs of gifted students.

See our offerings for educators

Consulting Services and Program Review

Re-imagine your gifted education services using our talent development framework

Curriculum Resources and Student Programs

Bring CTD’s curriculum, programming, and professional development to your classroom!

Review our Curriculum Resources

Job Opportunities

At Center for Talent Development (CTD), we believe the best educators don’t just teach; they inspire young people to think big, take risks and believe in themselves.

Browse our opportunities

Eligibility

Understanding a student’s academic potential and current level of achievement is an important step in choosing the best course.

Learn about eligibility criteria and program types

Grades and Evaluation

If you have selected a program and course, start your application.

Family Consulting

Invest in a conversation with an expert from CTD about understanding your child's abilities and planning for talent development.

CTD Assessment

Talent development is a journey that involves developing potential into achievement. Learn more about your child's academic potential, learning level, and need for advanced programming, including acceleration.

Parent Education Resources

CTD provides resources for parents to nurture their child's talent at home and outside the classroom.

See our resources

Family Events

CTD offers periodic workshops and webinars for parents and families

Explore all events

Enrichment and credit-bearing, accelerated programs designed for students at every age and stage of talent development.

Learn More About Our Programs

Grade Levels

- Pre K - Grade 2

- Grade 3 - Grade 8

- Grade 9 - Grade 12

Program Types

- Summer Programs

- Online Programs

- Weekend Programs

- Leadership and Service-Learning Programs

Assessments

A guide to understanding abilities, finding strengths, and charting a talent development pathway

Tuition and Fees

View tuition information

Financial Aid

Need-based financial aid is available to qualified students for most CTD programs and assessments.

Learn about financial aid options

Scholarships

CTD has several scholarship options and collaborates with the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.

Learn about scholarship options

Withdrawals and Refunds

Before enrolling, please review our withdrawal and refund policies.

Review all policies

The Research Behind Graphic Novels and Young Learners

By Leslie Morrison, CTD Summer Leapfrog Coordinator

Graphic novels have become a popular format in classrooms, partly due to their appeal to reluctant readers. More recently, a growing body of research , focused on how the brain processes the combination of images and text, indicates that graphic novels are also excellent resources for advanced learners.

When students read visual narratives, the activity in the brain is similar to how readers comprehend text-based sentences. However, when students learn to read graphic novels with an analytical eye, depth and complexity are added to the reading process.

With graphic novels, students use text and images to make inferences and synthesize information, both of which are abstract and challenging skills for readers. Images, just like text, can be interpreted in many different ways, and can bring nuances to the meaning of the story. In this form of literature, the images and the text are of equal importance —the text would not fully make sense without the images, and the reverse is true as well.

Graphic novels can also challenge students to think deeply about the elements of storytelling . In a traditional text, students uncover meaning embedded in sentences and paragraphs. In graphic texts, students must analyze the images, looking for signs of character development, for example, or clues that help build plot. All of this experience developing textual and visual reading skills contribute to students’ understanding of their world — the ways the text and images all around them communicate — and in turn help them in crafting their own stories .

Barbee, M. Comic Books as Models for Literacy Instruction. International Reading Association. 2015.

Brenna, B. How Graphic Novels Support Reading Comprehension Strategy Development in Children. Wiley-Blackwell. Literacy Journal, UKLA, pp.88- 94. 2012.

Brown, Sally. A Blended Approach to Reading and Writing Graphic Stories. Wiley Online Library. 2013.

Bucher, K., & Manning, M. Bringing Graphic Novels into a School’s Curriculum. The Clearing House, November / December 2004.

Cohn, Neil. The Visual Language of Comics: Introduction to the Structure and Cognition of Sequential Images . London: Bloomsbury. 2013.

Eisner, W. Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative . W.W. Norton & Company. 2008.

Gillenwater, C. Graphic Novels in Advanced English / Language Arts Classrooms: A Phenomenological Case Study. Dissertation, Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2012.

McCloud, S. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. William Morrow Paperbacks. 1994.

Comic in the Classroom: Why Comics?

The Impact of Structures and Meaning on Sequential Image Comprehension

Neil Cohn, Martin Paczinski, Phil Holcomb, Ray Jackendoff, Gina Kuperberg,

-Tufts University

http://www.visuallanguagelab.com/P/NC_pn&b_abstract.pdf

2023 © Northwestern University Center for Talent Development

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Graphic novels can accelerate critical thinking, capture nuance and complexity of history, says Stanford historian

Historical graphic novels can provide students a nuanced perspective into complex subjects in ways that are difficult, and sometimes impossible, to characterize in conventional writing and media, says Stanford historian Tom Mullaney.

Global history is not just significant events on a timeline, it is also the ordinary, mundane moments that people experience in between. Graphic novels can capture this multidimensionality in ways that are difficult, and sometimes impossible, in more traditional media formats, says Stanford history professor Tom Mullaney .

Tom Mullaney, a professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences, uses graphic novels in his teachings to help students appreciate different experiences and perspectives throughout history. (Image credit: Ilmiyah Achmad)

Mullaney has incorporated graphic novels in some of his Stanford courses since 2017; in 2020, he taught a course dedicated to the study of world history through comic strip formats.

While graphic novels are not a substitute for academic literature, he said he finds them a useful teaching and research tool. They not only portray the impact of historic events on everyday lives, but because they can be read in one or two sittings, they get to it at a much faster rate than say a 10,000 word essay or autobiography could.

“It accelerates the process of getting to subtlety,” said Mullaney, a professor of history at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences . “There’s just so much you can do, and so many questions you can ask, and so many perspective shifts you can carry out – like that! You can just do it – you show them something, they read it and BOOM! It’s like an accelerant. It’s awesome.”

For example, in Thi Bui’s graphic novel The Best We Could Do , themes of displacement and diaspora emerge as she talks about her family’s escape from war-torn Vietnam to the United States. The illustrated memoir shows Bui’s upbringing in suburban California and the complicated memories her parents carry with them as they move about their new life in America. In other chapters, she depicts her mother and father back in Vietnam and what their own childhood was like amidst the country’s upheaval.

Graphic novels like The Best We Could Do and also Maus , Art Spiegelman’s seminal portrayal of his Jewish family’s experience during the Holocaust, illustrate the challenges and subtleties of memory – particularly family memory – and the entanglements that arise when narrating history, Mullaney said.

Graphic novels prime readers for the complexity of doing and reading historical research and how there is no simplistic, narrative arc of history. “When I read a graphic novel, I feel prepared to ask questions that allow me to go into the harder core, peer-reviewed material,” Mullaney said.

The everyday moments that graphic novels are exceptionally good at capturing also raise questions in the reader’s mind, Mullaney said. Readers sit in the family living room and at the kitchen table with Spiegelman and Bui and follow along as their characters try to understand what their parent’s generation went through and discover it’s not always easy to grasp. “Not everything mom and dad say makes sense,” said Mullaney.

These seemingly mundane moments also present powerful opportunities for inquiry. “The ordinary is where the explanation lives and where you can start asking questions,” Mullaney added.

Graphic novels can also depict how in periods of war and conflict, violence can become part of everyday existence and survival. The simplicity of the format allows heavy, painful experiences to emerge from a panel untethered and unweighted from lengthy descriptions or dramatizations.

“They’re banal. They’re not dramatic. There are no strings attached. In a work of nonfiction, in an article or book, it would be almost impossible to do that. There would have to be so much expository writing and so much description that you would lose the horror of it,” Mullaney said.

A ‘fundamental misunderstanding’

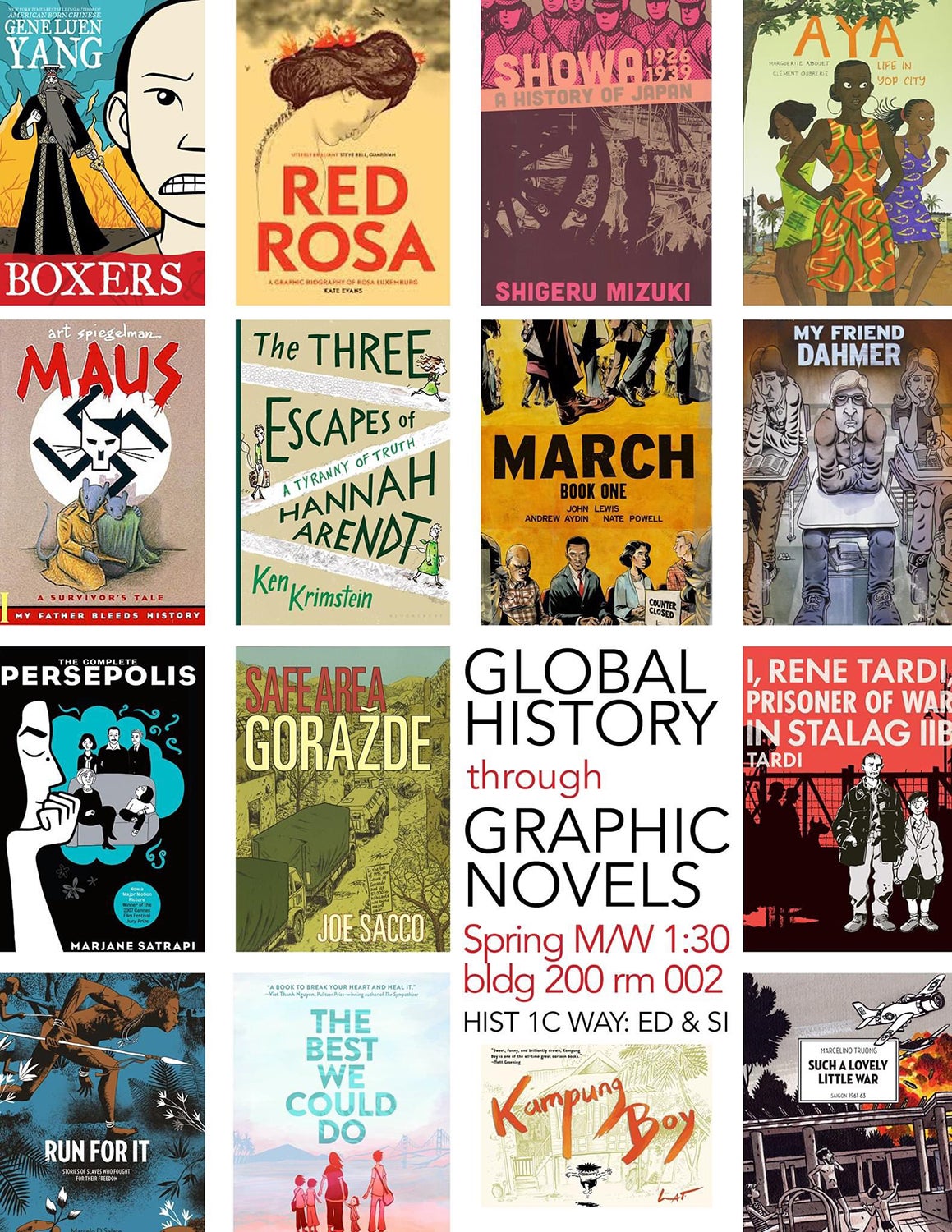

Graphic novels like Maus and The Best We Could Do were included in Mullaney’s 2020 Stanford class, Global History Through Graphic Novels .

In 2020, Tom Mullaney, a professor of history, taught Global History Through Graphic Novels , a course that paired graphic novels such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus with archival materials and historical essays to examine modern world history from the 18th to the 21st century. He created a poster for the class, as shown here. (Image credit: Tom Mullaney)

In the course, Mullaney paired graphic novels with archival materials and historical essays to examine modern world history from the 18th to the 21st century.

The course syllabus also included the graphic novels Showa , Shigeru Mizuki ’s manga series about growing up in Japan before World War II, and Such a Lovely Little War , about Marcelino Truong’s experience as a child in Saigon during the Vietnam War.

Most recently, Mullaney has offered to teach a variation of the Stanford course to the public, free for high school and college students , this summer.

Registration for the online course opened shortly after news emerged and made international headlines that Maus was banned by a Tennessee school board for its depiction of nudity and use of swear words.

Within two days of Mullaney’s course registration opening, over 200 students from across the world signed up.

Mullaney believes that there is a “fundamental misunderstanding” about what young people can process when it comes to negotiating complex themes and topics – whether it is structural racism or the Holocaust. They just need some guidance, which he hopes as a teacher, he can provide.

“I think students of high school age or even younger, if they have the scaffolding they need – which is the job of educators to give them – they can handle the structural inequalities, darknesses and horrors of life,” he said.

Mullaney noted that many teenagers are already exposed to many of these difficult issues through popular media. “But they’re just doing it on their own and figuring it out for themselves – that’s not a good idea,” he said.

Mullaney said he hopes he can teach Global History Through Graphic Novels to Stanford students again this fall.

For Stanford scholars interested in learning more about the intersection of graphic novels and scholarship, there is a newly established working group through the Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages, Comics, More than Words .

You have exceeded your limit for simultaneous device logins.

Your current subscription allows you to be actively logged in on up to three (3) devices simultaneously. click on continue below to log out of other sessions and log in on this device., teaching with graphic novels.

Illustration by Gareth Hinds

On March 14, 2013, teachers in the Chicago Public Schools were told, without explanation, to remove all copies of Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Persepolis (Pantheon, 2003) from their classrooms.

A day later, facing protests from students and anti-censorship organizations, Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett explained the move. The “powerful images of torture” on a single page of the book made it unsuitable for seventh graders and required the district to give teachers in grades eight through 10 special professional development classes before they could teach it. The book was pulled from classrooms for those grades, but remained in school libraries.

This is the paradox of graphic novels: The visual element that gives them their power can also make them vulnerable to challenges. Researcher Steven Cary calls this the “naked buns” effect. “It’s the rare student or parent who objects to the words ‘naked buns,’” he writes in Going Graphic: Comics at Work in the Multilingual Classroom (Heinemann, 2004). “But an image of naked buns can set off fireworks.”

At the same time, graphic novels are increasingly used in the classroom. For over a decade, public librarians have been promoting graphic novels as literature, and researchers have studied their benefits in educational settings.

From challenged material to classroom curricula

To help educators and librarians deal with the potential fallout sparked by strong graphic imagery, the American Library Association’s (ALA) Banned Books Week planning committee, working with the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), has made comics and graphic novels the focus of this year’s Banned Books Week (BBW; September 21–27). The CBLDF site has a free, downloadable BBW handbook and also tracks challenges in schools and public libraries, and offers advice on the educational use of graphic novels.

“The number and profile of challenges that CBLDF participates in has risen dramatically in recent years,” says Charles Brownstein, executive director of CBLDF. “As a partner in the Kids’ Right to Read Project , we are addressing challenges to comics and prose books on an almost weekly basis.” The nonprofit organization provides assistance in a number of ways, often writing letters of support for challenged books and talking to school and library administrators.

“Prose books and comics are challenged for the same reasons,” Brownstein says. “Content addressing the facts of life about growing up, like sexuality, sexual orientation, race issues, challenging authority, and drug and alcohol use are causes for challenges. [Profanity] is often a factor,” as is violence.

In the old days, comics found in schools were usually smuggled in by students, and challenges meant a teacher snatching away the “Richie Rich” or “Superman” concealed in a social studies textbook. Times have changed. In sixth-grade teacher Jennifer DeFeo’s social studies class at Thomas Jefferson Middle School in Jefferson City, Missouri, the textbook is a graphic novel, the centerpiece of the Zombie-Based Learning program, in which students learn geography by tracking the undead after a zombie apocalypse. She has used graphic novels in literacy classes to build vocabulary via context clues, which can be hard for some readers using prose books.

Because the last decade has seen a sharp increase in the number and quality of graphic novels published for readers of all ages, they are more common in classrooms and school libraries. Publishers often provide lesson plans, information on curricula, and tie-ins to the Common Core State Standards. The organization Reading With Pictures recently published a graphic textbook, Reading With Pictures: Comics That Make Kids Smarter (Andrews McMeel, 2014), an anthology of short, nonfiction comics stories accompanied by a downloadable teacher’s guide.

Graphic novels as teaching tools

Educators agree that graphic novels are useful for teaching new vocabulary, visual literacy, and reading skills. They “offer some solid advantages in reading education,” says Jesse Karp, early childhood and interdivisional librarian at the Little Red School House and Elisabeth Irwin High School in New York City. “They reinforce left-to-right sequence like nothing else. The images scaffold word/sentence comprehension and a deeper interpretation of the words and story. The relative speed and immediate enjoyment build great confidence in new readers.”

“For weak language learners and readers, graphic novels’ concise text paired with detailed images helps [them] decode and comprehend the text,” says Meryl Jaffe, an instructor at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth, Online Division, and the author of several books on using comics in the classroom. “Reading is less daunting, with less text to decode. While vocabulary is often advanced, the concise verbiage highlights effective language usage,” adds Jaffe, who also blogs for CBLDF about using comics in the classroom. She cites the “Babymouse” series (Random) and Squish, Super Amoeba (Random, 2011) both by Jennifer L. and Matthew Holm. “There is ‘smart’ but limited text, complemented by images that show what is being said, or thought.”

“For skilled readers, graphic novels offer a different type of reading experience while modeling concise language usage,” Jaffe adds. Jimmy Gownley’s “Amelia Rules!” series (S. & S.), for instance, uses a variety of visual techniques and dialog filled with humor and “words of wisdom.”

Furthermore, Jaffe says, the pairing of words and images gives learning a boost by creating new memory pathways and associations. “Research shows that our brains process and store visual information faster and more efficiently than verbal information,” she says. “Pairing [graphic novels] with traditional prose texts is an excellent means of promoting verbal skills and memory.” Ho Che Anderson’ s King (Fantagraphics, 2010), a biography of Martin Luther King Jr., for example, can be paired with biographies and news articles about civil rights.

“I feel that the lower average, although four percent is not that much lower, was partly due to the fact that I created the test from the actual text and not a combination of the text and the graphic novel,” Kallenborn adds. Repeating the experiment with Hamlet, he drew quiz questions from a summary, rather than the original text. Students who used the graphic novel spent 50 fewer minutes reading and scored seven percent higher on a comprehension quiz.

Effective communication

Sometimes graphic novels can convey an idea better than conventional prose. Ronell Whitaker, who teaches English at Dwight D. Eisenhower High School in Blue Island, Illinois, had been “running into a wall” trying to teach his students about inference until he started using graphic novels. When he taught Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese (First Second, 2006), his students had to infer that the three main characters were all the same person. “This was especially difficult for some of my kids, but when they got it, they felt like they had discovered a hidden message,” he says.

When teaching with graphic novels, Whitaker explains that readers infer what happens between panels. “I had kids write out the completed action of a page or two using descriptive prose,” he says. “They demonstrated two things: One, their ideas about what actions connected the images we can see in each panel. Two, how effective comics can be at communicating information.”

The pull of graphic novels in the school library was demonstrated in a 1981 study cited in Stephen D. Krashen’s The Power of Reading (Libraries Unlimited, 1993). Researchers put comics in a junior high school library and allowed students to read them there, but not check them out. Visits to the library increased by 87 percent and circulation of non-comic books by 30 percent.

Nonetheless, school libraries have seen their share of graphic novel challenges.

• In 2009, a mother asked that Amazing Spider-Man Vol II: Revelations by J. Michael Straczynski and others (Marvel, 2002) be pulled from an elementary school library in Millard, Oklahoma. “It has a lot of sexual undertones,” she said, adding that comics had little literary value.

• In 2010, a Minnesota woman asked that Jeff Smith’s series “Bone” (Scholastic) be removed from her school district’s libraries since it showed characters smoking and drinking. A committee voted 10-1 to keep it.

• After a parent and a county council member complained about violence and nudity in “Dragon Ball” (rated 13+ by its publisher, Viz Manga), the Wicomico, Maryland, school district removed it from all school libraries.

How to head off challenges

“The single most important step to prevent challenges is to have a detailed and comprehensive selection policy, including challenge procedure,” says Brownstein. “Many libraries and school districts refer to or even quote ALA’s Library Bill of Rights.” He also cites the importance of shelving books according to the appropriate age group.

“Often, people who think they want a title removed only want it out of reach of certain constituents or age groups,” says Karp. “I make sure there is no title in the collection that I wouldn’t go to the mat for,” such as American Born Chinese and Neil Gaiman and P. Craig Russell’s Coraline (HarperCollins, 2008) .

“When I distribute the books, I forewarn kids, ‘This one deals with war. It can be pretty graphic and painful,’” says Lee. “Or, ‘The characters curse a lot. If your parents will be upset that you’re reading a book with strong language, you might skip this.’” Some kids were uncomfortable with the drug use in Lynda Barry’s One Hundred Demons (Sasquatch, 2002), and Lee didn’t use Brian K. Vaughan’s Pride of Baghdad (D. C., 2006) in the book club because of images of violence involving animals.

Good communication with parents and staff is key. “I made sure my principal was on board before I even started the collection,” as well as conversing with administrators and parents, Keller says.

“If anything ever comes up, you want there to be as few surprises as possible,” Karp adds.

In seven years, Karp has had only one book objection go beyond a conversation. “The [objector voiced] their argument to a larger group of parents and administrators. We had an open discussion,” he says. “Careful explanation of how the graphic novel was used, particularly that it was intended for and only made available to older students, made a big difference.”

Should a challenge occur, Brownstein advises librarians to follow procedure “to the letter”—which can be difficult if it goes directly to the district school committee or an administrator, rather than the school. He urges them to report the challenge and reach out to CBLDF, ALA, and the Kids Right to Read project. “Even if the challenge is resolved quietly and successfully, it’s important to report it to us, to the Office of Intellectual Freedom at ALA, or the National Coalition Against Censorship,” he says. “The more information we have about what’s being challenged, the better equipped we are to respond in a helpful way, and to make proactive tools.”

While their visual aspect may make titles such as Persepolis or “Bone” vulnerable to challenges, that’s what also makes them essential to a school’s collection. “Today’s kids have grown up reading comics,” says Keller. “A school or library that doesn’t include comics isn’t addressing the needs or wants of their community….Images are a part of today’s culture: selfies, pictures on the net, ads, video, infographics. If we aren’t educating young students about reading images, they aren’t getting a rounded education.”

Brigid Alverson is editor of Good Comics for Kids. Robin Brenner, Lori Henderson, Esther Keller, and Eva Volin are contributors.

Get Print. Get Digital. Get Both!

Libraries are always evolving. Stay ahead. Log In.

Add Comment :-

Comment policy:.

- Be respectful, and do not attack the author, people mentioned in the article, or other commenters. Take on the idea, not the messenger.

- Don't use obscene, profane, or vulgar language.

- Stay on point. Comments that stray from the topic at hand may be deleted.

- Comments may be republished in print, online, or other forms of media.

- If you see something objectionable, please let us know . Once a comment has been flagged, a staff member will investigate.

First Name should not be empty !!!

Last Name should not be empty !!!

email should not be empty !!!

Comment should not be empty !!!

You should check the checkbox.

Please check the reCaptcha

Posted : Sep 14, 2014 09:09

Ethan Smith

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.

Posted 6 hours ago REPLY

Jane Fitgzgerald

Posted 6 hours ago

Michael Woodward

Continue reading.

Added To Cart

Related , now on the yarn podcast . . ., “the very unlikely forrest gump of the avant-garde.” a nicholas day q&a about nothing: john cage and 4’33”, we’ve got a gal from kalamazoo: it’s a polly horvath q&a and cover reveal for library girl, lumberjanes 10th anniversary campaign launches on kickstarter | news, new magical history tour 3-in-1 | exclusive announcement, the rules of the genre are: there are no rules. an alicia d. williams q&a on mid-air, "what is this" design thinking from an lis student.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, --> Log In

You did not sign in correctly or your account is temporarily disabled

REGISTER FREE to keep reading

If you are already a member, please log in.

Passwords must include at least 8 characters.

Your password must include at least three of these elements: lower case letters, upper case letters, numbers, or special characters.

The email you entered already exists. Please reset your password to gain access to your account.

Create an account password and save time in the future. Get immediate access to:

News, opinion, features, and breaking stories

Exclusive video library and multimedia content

Full, searchable archives of more than 300,000 reviews and thousands of articles

Research reports, data analysis, white papers, and expert opinion

Passwords must include at least 8 characters. Please try your entry again.

Your password must include at least three of these elements: lower case letters, upper case letters, numbers, or special characters. Please try your entry again.

Thank you for registering. To have the latest stories delivered to your inbox, select as many free newsletters as you like below.

No thanks. return to article, already a subscriber log in.

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Thank you for visiting.

We’ve noticed you are using a private browser. To continue, please log in or create an account.

CREATE AN ACCOUNT

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS

Already a subscriber log in.

Most SLJ reviews are exclusive to subscribers.

As a subscriber, you'll receive unlimited access to all reviews dating back to 2010.

To access other site content, visit our homepage .

ALAN v37n3 - 'The Best of Both Worlds': Rethinking the Literary Merit of Graphic Novels

"the best of both worlds": rethinking the literary merit of graphic novels.

T he future of this form awaits its participants who truly believe that the application of sequential art, with its interweaving of words and pictures, could provide a dimension of communication that contributes—hopefully on a level never before attained—to the body of literature that concerns itself with the examination of human experience.”— Will Eisner, Comics and Sequential Art (p. 141)

To say that graphic novels have attracted attention from educators is by now axiomatic. Professional journals, like this one, routinely feature articles that extol their virtue as a pedagogical tool. Books attest to the creative ways teachers are using them to scaffold students as readers and writers. Sessions devoted to graphic novels at the National Council of Teachers of English’s annual convention are invariably well attended and seem to proliferate in number from one year to the next. By all accounts, it would seem that educators have embraced a form of text whose older brother, the comic book, was scorned by teachers in the not-so-distant past. Appearances, however, can be deceiving.

When Melanie Hundley, on behalf of the editors of The ALAN Review , invited me to contribute a column on graphic novels for an issue of the journal devoted to the influence of film, new media, digital technology, and the image on young adult literature, I was only too happy to oblige because it afforded me the opportunity to confront two assumptions that strike me as characterizing arguments for using graphic novels in schools: the first is that graphic novels are a means to an end, an assumption that usually results in overlooking their literary merit; the second assumes that students will embrace graphic novels enthusiastically, in spite of the stigmas attached to them.

Literary Merit or Means to an End?: The Professional Debate

Consider, for a moment, some of the reasons educators are encouraged to embrace graphic novels—and, to a lesser extent, comic books—as a teaching tool. Graphic novels are said to:

- scaffold students for whom reading and writing are difficult ( Bitz, 2004 ; Frey & Fisher, 2004 ; Morrison, Bryan, & Chilcoat, 2002 );

- foster visual literacy ( Frey & Fisher, 2008 );

- support English language learners ( Ranker, 2007 );

- motivate “reluctant” readers ( Crawford, 2004 ; Dorrell, 1987 );

- and provide a stepping stone that leads students to transact with more traditional (and presumably more valuable) forms of literature.

These are worthwhile objectives, and it is not hard to understand why a form of text thought to lend itself to addressing so many ends would capture the imagination of educators. At the same time, these arguments strike me as perpetuating—albeit unintentionally—a misperception that has plagued the comic book for the better part of its existence. Specifically, it regards works written in the medium of comics (be it comic books or graphic novels) as a less complex, less sophisticated form of reading material best used with weaker readers or struggling students.

It is tempting to interpret the enthusiasm literacy educators have shown for graphic novels as a sign of the field’s having moved toward a broader understanding of what “counts” as text—surely our willingness to embrace a form of reading material similar to one our predecessors demonized is evidence of a more progressive, if not more enlightened, view. To be sure, there was no shortage of teachers and librarians who lined up to denounce the comic book when adolescents laid claim to it as a part of youth culture in the 1940s and 1950s. Less frequently acknowledged is that there were also educators who adopted a more tolerant view of the comic book and who sought to use students’ interest in it as a foundation on which to develop their literacy practices and literary tastes. By examining the professional debate that raged over comic books in the 1940s, it is possible to appreciate the extent to which current arguments for using graphic novels in the classroom parallel those educators made on behalf of the comic book in the past.

Parents and educators paid relatively little attention to the comic book when Superman made his debut in Action Comics in 1938. Within two years, however, the commercial success the character experienced, coupled with the legion of imitators he spawned, made it difficult for them to do so any longer. David Hadju (2008) observes that the number of comic books published in the United States grew from 150 in 1937 to approximately 700 in 1940 (p. 34). While the connection adults drew between comic books and juvenile delinquency would gain traction in the early 1950s, much of the early criticism leveled against comic books focused on their perceived aesthetic value—or lack thereof. Sterling North, a literary critic for the Chicago Daily News, was one of the first to question the propriety of allowing adolescents to read comic books. In an editorial published on May 8, 1940, titled “A National Disgrace,” he chastised the comic book for, among other things, being “badly drawn, badly written and badly printed” (p. 56). In his opinion, parents and teachers were obliged to “break the ‘comic’ magazine," and he identified the antidote: it was necessary, North argued, to ensure that young readers had recourse to quality literature. “The classics,” he wrote, “are full of humor and adventure—plus good writing” (p. 56). Parents and teachers who neglected to substitute traditional literature in place of comic books were, in his opinion, “guilty of criminal negligence” (p. 56). That the newspaper reportedly received over twenty-five million requests to reprint North’s editorial is evidence of the extent to which his call-to-action resonated with the public ( Nyberg, 1998 ).

Although the outcry over comic books dissipated in the face of World War II, professional and scholarly publications aimed at teachers and librarians continued to debate the influence they had on the literary habits of developing readers. Although there were educators who insisted that comic books were detrimental to reading, there were others who acknowledged the value students attached to them and advocated a more tolerant approach. One article, written by a high school English teacher and published in English Journal in 1946, is of particular interest, given the theme of this journal issue. Entitled “Comic Books— A Challenge to the English Teacher,” it opened by foregrounding a challenge its author felt “new” media posed for literacy educators:

The teaching of English today is a far more complex matter than it was thirty or forty years ago. It is not that the essential character of the adolescent student has changed, or that the principles of grammar or the tenets that govern good literature have been greatly modified, but rather that the average student of the present is being molded in many ways by three potent influences: the movies, the radio, and the comic book. ( Dias, 1946 , p. 142)

Rather than condemn comic books as a pernicious influence, he instead chose to appropriate them as a tool with which to foster student interest in traditional literature. Characterizing his efforts to do so as “missionary work among [his] comic-book heathens,” he explained how he engaged students in conversation regarding the comic books they read with the intention of identifying a genre that appealed to them ( Dias, 1946 , p. 143). Having done so, he recommended a traditional work of literature he thought might interest them. This approach, he argued, made it possible for him to build on students’ interests and use comic books “constructively as a stepping stone to a lasting interest in good literature” (p. 142).

Others took a similar tack. In 1942, Harriet Lee, who taught freshman English, observed that while teachers recognized a need to encourage students to evaluate their experiences with film and radio, they ignored comic books. Citing the success she experienced teaching a series of units that challenged students to critically assess the literary merit of their favorite comic books and comic strips—an approach that bears a faint resemblance to critical media literacy—she encouraged others to do the same. Two years later, W. W. D. Sones (1944) , a professor of education at the University of Pittsburgh, foregrounded the instructional value of comic books and cited research that suggested they could be used to support “slow” readers and motivate “non-academic” students (p. 234), a population whose alleged lack of interest in school-based reading and writing appears to have established them as forerunners to the so-called “reluctant” reader of today. Having identified other ends toward which comic books lent themselves, Sones characterized them as vehicles with which “to realize the purposes of the school in the improvement of reading, language development, or acquisition of information” (p. 238).

Significantly, these educators were united by a shared belief—although they advocated using comic books for instructional purposes, they showed little regard for their aesthetic value. Indeed, much like those who criticized comic books, they were unable to recognize any degree of literary merit in them at all. Instead, they regarded them as a way station on a journey whose ultimate purpose was to lead students to transact with traditional literature. Comic books were, as one English teacher put it, “a stepping stone to the realms of good literature—the literature that is the necessary and rightful heritage of the adolescent” ( Dias, 1946 , p. 143).

It is not hard to recognize points of overlap between the arguments outlined above and those made for using graphic novels in the classroom today. By foregrounding these parallels, I do not mean to suggest that contemporary educators are entirely blind to the graphic novel’s literary merit. Anyone who attends conferences or reads professional journals knows that certain titles— Maus ( Spiegelman, 1996 ) and Persepolis ( Satrapi, 2003 ) come readily to mind—are frequently cited as warranting close study. Nevertheless, arguments that foreground graphic novels as tools with which to support struggling readers, promote multiple literacies, motivate reluctant readers, or lead students to transact with more traditional forms of literature have the unintended effect of relegating them to a secondary role in the classroom; in doing so, they overlook the aesthetic value in much the same way as educators did in the past.

There is a difference between acknowledging (or, better yet, appropriating) a form of text and putting it to work in the classroom, and embracing it as a worthwhile form of reading material in its own right. At the current time, anecdotal evidence suggests that educators remain skeptical of the graphic novel’s literary merit. Hillary Chute (2008) , for example, points to “the negative reaction many in the academy have to the notion of ‘literary’ comics as objects of inquiry” (p. 460). Kimberly Campbell (2007) , who taught middle and high school language arts prior to teaching college, recalls conversations with colleagues who expressed their “concern that graphic novels don’t provide the rigor that novels require” (p. 207). I have spoken to high school teachers who were unwilling to use graphic novels with students in honors classes because they feared the ramifications. Asked to provide a rationale for teaching traditional literature—young adult or canonical—educators routinely cite its ability to foster self-reflection, initiate social change, promote tolerance, and stimulate the imagination. As those who read them know, good graphic novels are capable of realizing these same ends. As one junior in high school explained, “I love everything about them. I feel that they’re a beautiful painting mixed with an entertaining and thought-provoking novel. They’re the best of both worlds to me.”

Acceptable In-School Literature?: The Students' Debate

That educators should continue to question the literary merit of graphic novels is understandable. Graphic novels, like other novels, are not “value-free” texts, though we often seem to treat them as such. They have a history, and the stigmas that trail in their wake are capable of shaping our perceptions of them as a form of reading material. As John Berger (1972) observed, “The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe” (p. 8). Acknowledging this, a decision to introduce graphic novels in a context that has traditionally privileged “high art” can seem radical. Those who write about graphic novels, myself included, consequently recognize a need to persuade teachers—as well as parents—of their value. Yet whereas we acknowledge that teachers may question the graphic novel’s literary merit, we often seem to proceed under an assumption that students will embrace them unquestioningly, as if they were somehow impervious to the stigmas their elders recognize. My experiences working with students, both at the university and high school levels, suggest that teachers who are interested in using graphic novels may expect to encounter a certain degree of resistance.

To support this assertion, allow me to share a personal anecdote. For the past three years, I taught an introductory course on young adult literature for undergraduates interested in pursuing a career in elementary or secondary education. One of the course assignments required them to compose three critical response papers in which they responded to works of literature they read over the course of the quarter. Two of the papers asked them to address traditional young adult novels, while the third invited them to respond to a graphic novel. While there were inevitably students who appreciated the opportunity to read a graphic novel, a surprisingly large number were critical of them. This was especially true of those who wished to teach high school. While they were willing to entertain the notion that young adult literature might warrant a place in the curriculum, they vehemently resisted the possibility that graphic novels might be of value as well. One student wrote:

It’s understandable to have pictures in elementary grade level books because children at that grade level are still learning about comprehension and formulation of their own ideas. Young adults are at an age where they are able (and teachers want them to) form their own ideas and think critically about books. I believe that providing pictures strips away the young adult’s creative and critical thinking about books.

Another explained:

The combination of pictures and text in novels, to me, seems childish and doesn’t allow readers to think critically.

Still another student wrote:

For my teaching goals, I want to include literature that will do at least one of three things—preferably all of them at once: encourage students to read, teach something, and broaden the reader’s world view and encourage critical thinking. I do not believe that graphic novels do these things. First, there simply is not enough text to make me believe that it significantly encourages reading.

These are not extreme cases. Rather, I selected these excerpts because they are representative of the arguments I received from students who questioned the propriety of teaching graphic novels, particularly as a form of literature. It is interesting to note the negative manner in which they regarded the image, which they assumed precluded critical thinking. This is not the sort of response one might expect from members of a so-called “visual generation.” Yet conversations with colleagues at professional conferences indicate that this sort of resistance to graphic novels is not uncommon.

In conducting a study designed to understand how high school students responded to multimodal texts, Hammond (2009) found that the participants with whom she worked were cognizant of a stigma attached to reading graphic novels, the result of which detracted from their popularity (p. 126). My experiences working with six sophomores and juniors who participated in a case study that sought to understand how high school students read and talk about graphic novels yielded a similar finding. A recurring theme suggested that the students were aware of stigmas attached to graphic novels; one regarded them as a puerile form of reading material, and another saw those who read them as social misfits—or, to borrow their term, “nerds.”

These were not abstract arguments for one of the students, who took great pleasure in reading comic books and graphic novels. A junior in high school, Barry was familiar with the emotional pain such stigmas can cause, and when he talked about them, an underlying sense of anger often permeated his words. Reflecting on the ease with which his peers dismissed a form of reading material he valued, he wrote:

Why should I feel ashamed when I’m at track practice calling my pals to go to the comic book store while my teammates are around. [sic] It’s just strange how they can look at something that I find so beautiful, and spit on it without giving a second thought.

On another occasion, he suggested that the perception that graphic novels constituted a childish form of reading material was so prevalent, it dissuaded younger audiences from reading them, a fact he found ironic. “It’s to the point now where even kids that read comics are persecuted by other kids,” he explained.

It is worth noting that the students with whom I worked did not harbor a negative view of graphic novels. They volunteered to take part in an after-school reading group devoted to them, and in doing so, they evinced a willingness to explore a form of reading material that was new to some of them. That said, their cognizance of stigmas associated with graphic novels, coupled with the experience of the student who felt the disdain of his peers, suggest that these stigmas may constitute obstacles for teachers who choose to incorporate these texts into the curriculum. In short, we cannot, as educators, proceed from a belief that students will automatically embrace a form of reading material that has historically been stigmatized, especially when we ask them to interact with it in a classroom context. To become a member of what Rabinowitz (1987/1998 ) calls a text’s authorial audience, one might assume that readers have first to regard it as a viable form of reading material, a supposition that, in the case of graphic novels, may not always hold.

So What Now?

By challenging assumptions that underlie arguments for using graphic novels, I do not wish to detract from their value. Rather, I wish to suggest that it’s possible to view graphic novels in another light, one that acknowledges them as a viable form of literature that warrants close examination in its own right. My experiences working with the high school students who participated in my study consistently suggested that graphic novels are capable of inspiring high-level thinking, of stimulating rich discussion, and of fostering aesthetic appreciation—an observation the students shared. Sarah, a sophomore, explained:

I think all of us have taken away just as much from like our graphic novel reading experience as we have from our classroom reading experience. Maybe more. And I think . . . there’s just as much substance to graphic novels as there is to just regular literature, and I don’t think teachers realize that.

Another student remarked, “I didn’t know they were going to have such a big impact on how I look at things in the world.” Is this not the sort of thing we want students to say about their experiences with literature—indeed, about their experiences with art?

Good graphic novels, like good literature, are capable of moving readers to reflect on unexamined aspects of their lives. Not all graphic novels will, of course, but the same might be said of much of the traditional literature on bookstore shelves. To increase awareness of their literary merit and to gauge their potential complexity, it is necessary for professional and scholarly journals such as this one to call for articles that subject them to the same degree of critical scrutiny afforded traditional literature. Moreover, there is a need for reviews that acknowledge titles beyond the usual standards and that help educators keep pace with the multitude of graphic novels published each year. Finally, there is a need for a field-wide conversation that identifies the challenges involved in using graphic novels so that we might begin to address them and, in doing so, develop a sense of appreciation for their artistic merit.

Sean Connors is an assistant professor of English Education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education and Health Professions, at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Prior to pursuing his doctoral degree, Sean taught English at Coconino High School in Flagstaff, Arizona. He has taught undergraduate courses in Young Adult Literature, as well as an English Education Lab Experience course for potential preservice English language arts teachers. His scholarly interests include understanding how adolescents read and experience graphic novels, and asking how educators might expand the use of diverse critical perspectives in secondary school literature curricula. When he isn’t reading graphic novels and young adult literature, Sean enjoys hiking with his wife and dogs and rooting for the Red Sox.

Works Cited

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. New York: Viking Press.

Bitz, M. (2004). The comic book project: Forging alternative pathways to literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47, 574-586.

Campbell, K. H. (2007). Less is more: Teaching literature with short texts - grades 6--12. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Chute, H. (2008). Comics as literature? Reading graphic narrative. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 123, 452-465.

Crawford, P. (2004). A novel approach: Using graphic novels to attract reluctant readers and promote literacy. Literacy Media Connection, 22 (5), 26-28.

Dias, E. J. (1946). Comic books - A challenge to the English teacher. English Journal, 35 (3), 142-145.

Dorrell, L. D. Why comic books? School Library Journal, 34 (3), 30-32.

Eisner, W. (1985). Comics and sequential art: Principles & practice of the world's most popular art form. Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press.

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2008). Teaching visual literacy: Using comic books, graphic novels, anime, cartoons, and more to develop comprehension and thinking skills. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2004). Using graphic novels, anime, and the Internet in an urban high school. English Journal, 93 (3), 19-25.

Hadju, D. (2008). The ten-cent plague: The great comic-book scare and how it changed America. New York: Picador

Hammond, H. K. (2009). Graphic novels and multimodal literacy: A reader response study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota.

Lee, H. E. (1942). Discrimination in reading. English Journal, 31 (9), 677-679.

Morrison, T. G., Bryan, G., & Chilcoat, G. W. (2002). Using student-generated comic books in the classroom. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45, 758-767.

North, S. (1940, June). A national disgrace. Illinois Libraries, p. 3.

Nyberg, A. K. (1998). Seal of approval: The history of the comics code. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Rabinowitz, P. J. (1987/1998). Before reading: Narrative conventions and the politics of interpretation. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Ranker, J. (2007). Using comic books as read-alouds: Insights on reading instruction from an English as a second language classroom. The Reading Teacher, 61, 296-305.

Satrapi, M. (2003). Persepolis: The story of a childhood. New York: Pantheon.

Sones, W. W. D. (1944). The comics and the institutional method. Journal of Educational Sociology, 18, 232-240.

Spiegelman, A. (1996). The complete Maus: A survivor's tale. New York: Pantheon.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

With graphic novels, students use text and images to make inferences and synthesize information, both of which are abstract and challenging skills for readers. Images, just like text, can be interpreted in many different ways, and can bring nuances to the meaning of the story. In this form of literature, the images and the text are of equal ...

Abstract. Student engagement in novels is a key factor in whether or not a student can be successful in reading. The purpose of this study was to analyze student engagement with graphic novels and traditional novels, and to describe any preferences students had when selecting novels to read independently.

children's literature must be high quality. Likewise, not all graphic novels are equal, and as they become more frequently used in the classroom, quality becomes a vital question. Most of the research on graphic novels in the classroom has taken place at the secondary-college level (Carter 2007; Frey and Fisher 2008; Tabachnik 2009).

Historical graphic novels can provide students a nuanced perspective into complex subjects in ways that are difficult, and sometimes impossible, to characterize in conventional writing and media ...

A Case for the Inclusion of Graphic Novels in the Classroom. By Brittany Rosenberg . Abstract. This paper will explore the use of graphic novels in the context of the classroom, ultimately arguing that graphic novels not only deserve a place in elementary through high school classrooms, but are an effective and successful learning tool. The ...

The didactic potential and pedagogical value of graphic novels have caught the attention of ... this essay explains how graphic novels can be used to achieve major institutional ... petence on the story level.5 Intercultural learning can also be realized if graphic novels initiate research on a foreign culture, for instance, when a story is ...

Literacy experts herald the educational benefits of using graphic novels across the curriculum and with different types of students. This study involved an analysis of the graphic novel format compared to the ... GNs in the classroom based on her experiences and research. The benefits included the facilitation of rich discussion, application of ...

suggested specific strategies for use with graphic novels. This paper discussed the plan of action the researchers implemented to include graphic novels in their curriculum, as well as implications of their findings. Keywords: graphic novels, literacy texts, multimodal reading, visual strategies, synthesizing strategies _____

Michael A. Chaney's edited collection Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels is a welcome addition to the growing body of scholarly literature investigating graphic texts. Chaney has grouped twenty-seven essays into four sections, focusing on the work of Art Spiegelman, global autography, women's life writing, and the range of self-representational strategies to ...

A multifaceted, classroom‐based research project explored how developing Grade 7 students' knowledge of literary and illustrative elements affects their understanding, interpretation and analysis of picturebooks and graphic novels, and their subsequent creation of their own print texts.

Abstract. The increase of graphic novels in libraries and schools and on award lists illustrates one way that children's literature is changing. This article explores the relation between words and illustrations in a popular graphic novel. The multimodal format of graphic novels requires readers to consider the words, graphics, panel sizes, and ...

Teach literary devices - Readers are required to be actively engaged in the process of decoding and comprehending a range of literacy devices, including narrative structure, metaphor and symbolism, point of view, and the use of puns, alliteration, and inferences. Teach the classics- Classic novels that have been adapted to graphic novels ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Read an excerpt from an article on filmmaking. Filmmaking can be broken down into three phases. The preproduction phase includes things such as securing financing for the film, writing the script, scouting locations, and hiring cast and crew. In the production phase the actual recording of the video and audio takes place. This ...

Jessica Lee, a teacher librarian at Willard Middle School in Berkeley, California, who hosts a weekly graphic novel discussion group, sees the speed factor as a plus. "With text-only books, kids read at such different rates and often struggle to finish a novel in a timely manner," she says. "With graphic novels, we are all on the same ...

In doing that, we wove a reading and oral language experience together to model text prompts for writing. Bringing students' out-of-school love for graphic novels to re-engage learners. Here's why it's worked. 1. Graphic novels use interwoven visuals and text to convey meaning to readers. Graphic novels are a multimodel text and there's ...

graphic novels, created pre and post unit creative pieces based on the literary terms and were observed for behaviors and attitudes. The findings show that using graphic novels can enhance student recall of literary terms and they are a text type students enjoy. Teachers should use graphic novels in classrooms because they are an engaging tool that

Those who write about graphic novels, myself included, consequently recognize a need to persuade teachers—as well as parents—of their value. Yet whereas we acknowledge that teachers may question the graphic novel's literary merit, we often seem to proceed under an assumption that students will embrace them unquestioningly, as if they were ...

For example, it's easy to create a sizzling sound. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Decide if each phrase is an example of standard English or slang. Sort the tiles into the correct categories., Prompt: Write an informative essay explaining what has caused the English spoken today to be different from the English ...

In the essay Singer ponders whether new technologies—and the ever-expanding and accessible "sea of information"—might make it increasingly difficult for writers to retain the public's interest. Hillary Chute surveys the latest releases in graphic adaptations of literary classics, including Renee Nault's version of The Handmaid's ...

They are: choosing a topic, researching for an informative essay, constructing an outline of your informative essay, writing and concluding, finalizing, and revising the project. Following these steps will help students write an informative essay correctly. Therefore, this structure is essential to make your informative essay effective and ...

A research-based essay that addresses the issue of graphic novels and their place as literature and also informs readers about the value of graphic novels is given below.. Some of the uses of a graphic novel are:. They are used to tell a story; They are a fun way to make illustrations; They help the readers to grasp the concept of the action; They help in imagery,. etc

English 2 Semester 1. Read the description a student gave about how she wrote her research paper. Once I analyzed the prompt, I was able to determine my purpose and audience. Since I knew it was a research-based essay, I found several valid sources, making sure to write citation information for each, so I could use the citations in my paper and ...