Module 4: Strategic Reading

The Structure of an Academic Article

Generally speaking, there is a common flow to scholarly articles. While not a template per se, you can be assured that the following components will be present in most articles. Learning to identify each component is a key step in the strategic reading process, and will help you save time as you screen articles for relevance. Check out the interactive example below that describes each section.

Click on the purple question marks to learn more about each component of an academic article.

Structure of an Academic Article by Emma Seston. Licenced under Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 .

Key Takeaways

Learning to identify each component is a key step in the strategic reading process, and will help you save time as you screen articles for relevance.

Advanced Research Skills: Conducting Literature and Systematic Reviews Copyright © 2021 by Kelly Dermody; Cecile Farnum; Daniel Jakubek; Jo-Anne Petropoulos; Jane Schmidt; and Reece Steinberg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Scientific Writing: Structuring a scientific article

- Resume/Cover letter

- Structuring a scientific article

- AMA Citation Style This link opens in a new window

- APA Citation Style This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publishing This link opens in a new window

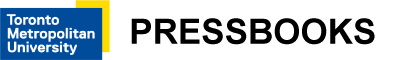

How to Structure a Scientific Article

Many scientific articles include the following elements:

I. Abstract: The abstract should briefly summarize the contents of your article. Be sure to include a quick overview of the focus, results and conclusion of your study.

II. Introduction: The introduction should include any relevant background information and articulate the idea that is being investigated. Why is this study unique? If others have performed research on the topic, include a literature review.

III. Methods and Materials: The methods and materials section should provide information on how the study was conducted and what materials were included. Other researchers should be able to reproduce your study based on the information found in this section.

IV. Results: The results sections includes the data produced by your study. It should reflect an unbiased account of the study's findings.

V. Discussion and Conclusion: The discussion section provides information on what researches felt was significant and analyzes the data. You may also want to provide final thoughts and ideas for further research in the conclusion section.

For more information, see How to Read a Scientific Paper.

Scientific Article Infographic

- Structure of a Scientific Article

- << Previous: Resume/Cover letter

- Next: AMA Citation Style >>

- Last Updated: Jan 23, 2023 11:48 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/scientific-writing

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- Research Guides

Reading for Research: Social Sciences

Structure of a research article.

- Structural Read

Guide Acknowledgements

How to Read a Scholarly Article from the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University

Strategic Reading for Research from the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University

Bridging the Gap between Faculty Expectation and the Student Experience: Teaching Students toAnnotate and Synthesize Sources

Librarian for Sociology, Environmental Sociology, MHS and Public Policy Studies

Academic writing has features that vary only slightly across the different disciplines. Knowing these elements and the purpose of each serves help you to read and understand academic texts efficiently and effectively, and then apply what you read to your paper or project.

Social Science (and Science) original research articles generally follow IMRD: Introduction- Methods-Results-Discussion

Introduction

- Introduces topic of article

- Presents the "Research Gap"/Statement of Problem article will address

- How research presented in the article will solve the problem presented in research gap.

- Literature Review. presenting and evaluating previous scholarship on a topic. Sometimes, this is separate section of the article.

Method & Results

- How research was done, including analysis and measurements.

- Sometimes labeled as "Research Design"

- What answers were found

- Interpretation of Results (What Does It Mean? Why is it important?)

- Implications for the Field, how the study contributes to the existing field of knowledge

- Suggestions for further research

- Sometimes called Conclusion

You might also see IBC: Introduction - Body - Conclusion

- Identify the subject

- State the thesis

- Describe why thesis is important to the field (this may be in the form of a literature review or general prose)

Body

- Presents Evidence/Counter Evidence

- Integrate other writings (i.e. evidence) to support argument

- Discuss why others may disagree (counter-evidence) and why argument is still valid

- Summary of argument

- Evaluation of argument by pointing out its implications and/or limitations

- Anticipate and address possible counter-claims

- Suggest future directions of research

- Next: Structural Read >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 10:44 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/readingforresearch

Structuring your article correctly

Anthony Newman

About this module

One of the key goals when writing a journal article is to communicate the findings clearly. In order to help researchers achieve that objective, scientific papers share a common structure (with slight variations per journal). Clear communication isn’t the only reason these article elements are so important; for example, the title, abstract, and keywords all help to ensure the article is found, indexed, and advertised to potential readers.

In this interactive module, we walk early career researchers through each of the building blocks. We help you understand the type of content each element should contain. We also share tips on how you can maximize their potential, such as key points to consider when writing your article title.

You will come away with the detailed knowledge you need to write an effective scientific article, increasing your chances of publication success.

About the presenter

Senior Publisher, Life Sciences, Elsevier

Anthony Newman is a Senior Publisher with Elsevier and is based in Amsterdam. Each year he presents numerous Author Workshops and other similar trainings worldwide. He is currently responsible for fifteen biochemistry and laboratory medicine journals, he joined Elsevier over thirty years ago and has been Publisher for more than twenty of those years. Before then he was the marketing communications manager for the biochemistry journals of Elsevier. By training he is a polymer chemist and was active in the surface coating industry before leaving London and moving to Amsterdam in 1987 to join Elsevier.

Writing a Scientific Paper: From Clutter to Clarity

Elements of style for writing scientific journal articles, preparing to write for an interdisciplinary journal, how to get published, how to publish in scholarly journals.

Elsevier Early Career Resources -- Advice for young and ambitious scientists

Elsevier Early Career Resources -- Look for the seed of brilliance

How to Write Great Papers (workshop on edition & publication)

Journal Authors

Author Services

JournalFinder

Elsevier Webshop

ScienceDirect

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER BRIEF

- 08 May 2019

Toolkit: How to write a great paper

A clear format will ensure that your research paper is understood by your readers. Follow:

1. Context — your introduction

2. Content — your results

3. Conclusion — your discussion

Plan your paper carefully and decide where each point will sit within the framework before you begin writing.

Collection: Careers toolkit

Straightforward writing

Scientific writing should always aim to be A, B and C: Accurate, Brief, and Clear. Never choose a long word when a short one will do. Use simple language to communicate your results. Always aim to distill your message down into the simplest sentence possible.

Choose a title

A carefully conceived title will communicate the single core message of your research paper. It should be D, E, F: Declarative, Engaging and Focused.

Conclusions

Add a sentence or two at the end of your concluding statement that sets out your plans for further research. What is next for you or others working in your field?

Find out more

See additional information .

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01362-9

Related Articles

How to get published in high impact journals

So you’re writing a paper

Writing for a Nature journal

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Career Feature 03 MAY 24

Postdoc in CRISPR Meta-Analytics and AI for Therapeutic Target Discovery and Priotisation (OT Grant)

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 14/06/2024 Human Technopole (HT) is a new interdisciplinary life science research institute created and supported by the...

Human Technopole

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

PhD/master's Candidate

PhD/master's Candidate Graduate School of Frontier Science Initiative, Kanazawa University is seeking candidates for PhD and master's students i...

Kanazawa University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- SpringerLink shop

Structuring your manuscript

Once you have completed your experiments it is time write it up into a coherent and concise paper which tells the story of your research. Researchers are busy people and so it is imperative that research articles are quick and easy to read. For this reason papers generally follow a standard structure which allows readers to easily find the information they are looking for. In the next part of the course we will discuss the standard structure and what to include in each section.

Overview of IMRaD structure

IMRaD refers to the standard structure of the body of research manuscripts (after the Title and Abstract):

- I ntroduction

- M aterials and Methods

- D iscussion and Conclusions

Not all journals use these section titles in this order, but most published articles have a structure similar to IMRaD. This standard structure:

- Gives a logical flow to the content

- Makes journal manuscripts consistent and easy to read

- Provides a “map” so that readers can quickly find content of interest in any manuscript

- Reminds authors what content should be included in an article

Provides all content needed for the work to be replicated and reproduced Although the sections of the journal manuscript are published in the order: Title, Abstract, Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion, this is not the best order for writing the sections of a manuscript. One recommended strategy is to write your manuscript in the following order:

1. Materials and Methods

These can be written first, as you are doing your experiments and collecting the results.

3. Introduction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Write these sections next, once you have had a chance to analyse your results, have a sense of their impact and have decided on the journal you think best suits the work

7. Abstract

Write your Title and Abstract last as these are based on all the other sections.

Following this order will help you write a logical and consistent manuscript.

Use the different sections of a manuscript to ‘tell a story’ about your research and its implications.

Back │ Next

Library Instruction

Structure of typical research article.

The basic structure of a typical research paper includes Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each section addresses a different objective.

- the problem they intend to address -- in other words, the research question -- in the Introduction ;

- what they did to answer the question in Methodology ;

- what they observed in Results ; and

- what they think the results mean in Discussion .

A substantial study will sometimes include a literature review section which discusses previous works on the topic. The basic structure is outlined below:

- Author and author's professional affiliation is identified

- Introduction

- Literature review section (a discussion about what other scholars have written on the topic)

- Methodology section (methods of data gathering are explained)

- Discussion section

- Conclusions

- Reference list with citations (sources of information used in the article)

Thanks for helping us improve csumb.edu. Spot a broken link, typo, or didn't find something where you expected to? Let us know. We'll use your feedback to improve this page, and the site overall.

Structure of a Research Paper: Tips to Improve Your Manuscript

You’ve spent months or years conducting your academic research. Now it’s time to write your journal article. For some, this can become a daunting task because writing is not their forte. It might become difficult to even start writing. However, once you organize your thoughts and begin writing them down, the overall task will become easier.

We provide some helpful tips for you here.

Organize Your Thoughts

Perhaps one of the most important tasks before you even begin to write is to get organized. By this point, your data is compiled and analyzed. You most likely also have many pages of “notes”. These must also be organized. Fortunately, this is much easier to do than in the past with hand-written notes. Presuming that these tasks are completed, what’s next?

Related: Ready with your title and looking forward to manuscript submission ? Check these journal selection guidelines now!

When suggesting that you organize your thoughts, we mean to take a look at what you have compiled. Ask yourself what you are trying to convey to the reader. What is the most important message from your research? How will your results affect others? Is more research necessary?

Write your answers down and keep them where you can see them while writing. This will help you focus on your goals.

Aim for Clarity

Your paper should be presented as clearly as possible. You want your readers to understand your research. You also do not want them to stop reading because the text is too technical.

Keep in mind that your published research will be available in academic journals all over the world. This means that people of different languages will read it. Moreover, even with scientists, this could present a language barrier. According to a recent article , always remember the following points as you write:

- Clarity : Cleary define terms; avoid nonrelevant information.

- Simplicity : Keep sentence structure simple and direct.

- Accuracy : Represent all data and illustrations accurately.

For example, consider the following sentence:

“Chemical x had an effect on metabolism.”

This is an ambiguous statement. It does not tell the reader much. State the results instead:

“Chemical x increased fat metabolism by 20 percent.”

All scientific research also provide significance of findings, usually presented as defined “P” values. Be sure to explain these findings using descriptive terms. For example, rather than using the words “ significant effect ,” use a more descriptive term, such as “ significant increase .”

For more tips, please also see “Tips and Techniques for Scientific Writing”. In addition, it is very important to have your paper edited by a native English speaking professional editor. There are many editing services available for academic manuscripts and publication support services.

Research Paper Structure

With the above in mind, you can now focus on structure. Scientific papers are organized into specific sections and each has a goal. We have listed them here.

- Your title is the most important part of your paper. It draws the reader in and tells them what you are presenting. Moreover, if you think about the titles of papers that you might browse in a day and which papers you actually read, you’ll agree.

- The title should be clear and interesting otherwise the reader will not continue reading.

- Authors’ names and affiliations are on the title page.

- The abstract is a summary of your research. It is nearly as important as the title because the reader will be able to quickly read through it.

- Most journals, the abstract can become divided into very short sections to guide the reader through the summaries.

- Keep the sentences short and focused.

- Avoid acronyms and citations.

- Include background information on the subject and your objectives here.

- Describe the materials used and include the names and locations of the manufacturers.

- For any animal studies, include where you obtained the animals and a statement of humane treatment.

- Clearly and succinctly explain your methods so that it can be duplicated.

- Criteria for inclusion and exclusion in the study and statistical analyses should be included.

- Discuss your findings here.

- Be careful to not make definitive statements .

- Your results suggest that something is or is not true.

- This is true even when your results prove your hypothesis.

- Discuss what your results mean in this section.

- Discuss any study limitations. Suggest additional studies.

- Acknowledge all contributors.

- All citations in the text must have a corresponding reference.

- Check your author guidelines for format protocols.

- In most cases, your tables and figures appear at the end of your paper or in a separate file.

- The titles (legends) usually become listed after the reference section.

- Be sure that you define each acronym and abbreviation in each table and figure.

Helpful Rules

In their article entitled, “Ten simple rules for structuring papers,” in PLOS Computational Biology , authors Mensh and Kording provided 10 helpful tips as follows:

- Focus on a central contribution.

- Write for those who do not know your work.

- Use the “context-content-conclusion” approach.

- Avoid superfluous information and use parallel structures.

- Summarize your research in the abstract.

- Explain the importance of your research in the introduction.

- Explain your results in a logical sequence and support them with figures and tables.

- Discuss any data gaps and limitations.

- Allocate your time for the most important sections.

- Get feedback from colleagues.

Some of these rules have been briefly discussed above; however, the study done by the authors does provide detailed explanations on all of them.

Helpful Sites

Visit the following links for more helpful information:

- “ Some writing tips for scientific papers ”

- “ How to Structure Your Dissertation ”

- “ Conciseness in Academic Writing: How to Prune Sentences ”

- “ How to Optimize Sentence Length in Academic Writing ”

So, do you follow any additional tips when structuring your research paper ? Share them with us in the comments below!

Thanks for sharing this post. Great information provided. I really appreciate your writing. I like the way you put across your ideas.

Enago, is a good sources of academics presentation and interpretation tools in research writing

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Research Manuscripts Using AI-Powered Insights: Enago reports for effective research communication

Language Quality Importance in Academia AI in Evaluating Language Quality Enago Language Reports Live Demo…

- Reporting Research

Beyond Spellcheck: How copyediting guarantees error-free submission

Submitting a manuscript is a complex and often an emotional experience for researchers. Whether it’s…

How to Find the Right Journal and Fix Your Manuscript Before Submission

Selection of right journal Meets journal standards Plagiarism free manuscripts Rated from reviewer's POV

- Manuscripts & Grants

Research Aims and Objectives: The dynamic duo for successful research

Picture yourself on a road trip without a destination in mind — driving aimlessly, not…

How Academic Editors Can Enhance the Quality of Your Manuscript

Avoiding desk rejection Detecting language errors Conveying your ideas clearly Following technical requirements

Top 4 Guidelines for Health and Clinical Research Report

Top 10 Questions for a Complete Literature Review

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Structuring the Research Paper

Formal research structure.

These are the primary purposes for formal research:

enter the discourse, or conversation, of other writers and scholars in your field

learn how others in your field use primary and secondary resources

find and understand raw data and information

For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research. The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Usually, research papers flow from the general to the specific and back to the general in their organization. The introduction uses a general-to-specific movement in its organization, establishing the thesis and setting the context for the conversation. The methods and results sections are more detailed and specific, providing support for the generalizations made in the introduction. The discussion section moves toward an increasingly more general discussion of the subject, leading to the conclusions and recommendations, which then generalize the conversation again.

Sections of a Formal Structure

The introduction section.

Many students will find that writing a structured introduction gets them started and gives them the focus needed to significantly improve their entire paper.

Introductions usually have three parts:

presentation of the problem statement, the topic, or the research inquiry

purpose and focus of your paper

summary or overview of the writer’s position or arguments

In the first part of the introduction—the presentation of the problem or the research inquiry—state the problem or express it so that the question is implied. Then, sketch the background on the problem and review the literature on it to give your readers a context that shows them how your research inquiry fits into the conversation currently ongoing in your subject area.

In the second part of the introduction, state your purpose and focus. Here, you may even present your actual thesis. Sometimes your purpose statement can take the place of the thesis by letting your reader know your intentions.

The third part of the introduction, the summary or overview of the paper, briefly leads readers through the discussion, forecasting the main ideas and giving readers a blueprint for the paper.

The following example provides a blueprint for a well-organized introduction.

Example of an Introduction

Entrepreneurial Marketing: The Critical Difference

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, John A. Welsh and Jerry F. White remind us that “a small business is not a little big business.” An entrepreneur is not a multinational conglomerate but a profit-seeking individual. To survive, he must have a different outlook and must apply different principles to his endeavors than does the president of a large or even medium-sized corporation. Not only does the scale of small and big businesses differ, but small businesses also suffer from what the Harvard Business Review article calls “resource poverty.” This is a problem and opportunity that requires an entirely different approach to marketing. Where large ad budgets are not necessary or feasible, where expensive ad production squanders limited capital, where every marketing dollar must do the work of two dollars, if not five dollars or even ten, where a person’s company, capital, and material well-being are all on the line—that is, where guerrilla marketing can save the day and secure the bottom line (Levinson, 1984, p. 9).

By reviewing the introductions to research articles in the discipline in which you are writing your research paper, you can get an idea of what is considered the norm for that discipline. Study several of these before you begin your paper so that you know what may be expected. If you are unsure of the kind of introduction your paper needs, ask your professor for more information. The introduction is normally written in present tense.

THE METHODS SECTION

The methods section of your research paper should describe in detail what methodology and special materials if any, you used to think through or perform your research. You should include any materials you used or designed for yourself, such as questionnaires or interview questions, to generate data or information for your research paper. You want to include any methodologies that are specific to your particular field of study, such as lab procedures for a lab experiment or data-gathering instruments for field research. The methods section is usually written in the past tense.

THE RESULTS SECTION

How you present the results of your research depends on what kind of research you did, your subject matter, and your readers’ expectations.

Quantitative information —data that can be measured—can be presented systematically and economically in tables, charts, and graphs. Quantitative information includes quantities and comparisons of sets of data.

Qualitative information , which includes brief descriptions, explanations, or instructions, can also be presented in prose tables. This kind of descriptive or explanatory information, however, is often presented in essay-like prose or even lists.

There are specific conventions for creating tables, charts, and graphs and organizing the information they contain. In general, you should use them only when you are sure they will enlighten your readers rather than confuse them. In the accompanying explanation and discussion, always refer to the graphic by number and explain specifically what you are referring to; you can also provide a caption for the graphic. The rule of thumb for presenting a graphic is first to introduce it by name, show it, and then interpret it. The results section is usually written in the past tense.

THE DISCUSSION SECTION

Your discussion section should generalize what you have learned from your research. One way to generalize is to explain the consequences or meaning of your results and then make your points that support and refer back to the statements you made in your introduction. Your discussion should be organized so that it relates directly to your thesis. You want to avoid introducing new ideas here or discussing tangential issues not directly related to the exploration and discovery of your thesis. The discussion section, along with the introduction, is usually written in the present tense.

THE CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SECTION

Your conclusion ties your research to your thesis, binding together all the main ideas in your thinking and writing. By presenting the logical outcome of your research and thinking, your conclusion answers your research inquiry for your reader. Your conclusions should relate directly to the ideas presented in your introduction section and should not present any new ideas.

You may be asked to present your recommendations separately in your research assignment. If so, you will want to add some elements to your conclusion section. For example, you may be asked to recommend a course of action, make a prediction, propose a solution to a problem, offer a judgment, or speculate on the implications and consequences of your ideas. The conclusions and recommendations section is usually written in the present tense.

Key Takeaways

- For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research.

- The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Scholarly Journal Articles: Structure and Function

- Scholarly Publications

- Forms of Literature

- Peer-review

- Structure of a research article

- Sample Articles

- Title and Abstract

- Authors and Funding

- Introduction and Methods

- Results and Discussion

Structure of a research article in the health sciences

Research in the health sciences can be qualitative, quantitative, or a combination of the two. This guide will focus primarily on quantitative research.

Quantitative research articles are usually written in a standardized format called the IMRaD format. This acronym refers to the I ntroduction, M ethods, R esults, (and) D iscussion sections of the articles. There is also usually a Conclusions section. By following this conventional structure, authors ensure that readers of their articles will be able to readily locate the paper's critical elements.

This rule is not hard and fast, and sometimes the sections may be rearranged or combined, or the authors may use alternate wording for the headings. Regardless, the basic elements are usually present.

Some types of original studies , such as case reports, do not readily lend themselves to this format. But even these types of papers will often follow a logical progression, in which they begin by stating the problem, then move on to describing their findings, and finally to offering possible explanations or conclusions.

Journal articles that are not primary literature, most notably review articles, will be written in whatever style is most appropriate to the content.

- << Previous: Peer-review

- Next: Sample Articles >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 11:08 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uvm.edu/ScholarlyJournalArticle

- Search Menu

- Chemical Biology and Nucleic Acid Chemistry

- Computational Biology

- Critical Reviews and Perspectives

- Data Resources and Analyses

- Gene Regulation, Chromatin and Epigenetics

- Genome Integrity, Repair and Replication

- Methods Online

- Molecular Biology

- Nucleic Acid Enzymes

- RNA and RNA-protein complexes

- Structural Biology

- Synthetic Biology and Bioengineering

- Advance Articles

- Breakthrough Articles

- Special Collections

- Scope and Criteria for Consideration

- Author Guidelines

- Data Deposition Policy

- Database Issue Guidelines

- Web Server Issue Guidelines

- Submission Site

- About Nucleic Acids Research

- Editors & Editorial Board

- Information of Referees

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, description of the web server, results and discussion, data availability, acknowledgements, alphafind: discover structure similarity across the proteome in alphafold db.

The first two authors should be regarded as Joint First Authors.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David Procházka, Terézia Slanináková, Jaroslav Olha, Adrián Rošinec, Katarína Grešová, Miriama Jánošová, Jakub Čillík, Jana Porubská, Radka Svobodová, Vlastislav Dohnal, Matej Antol, AlphaFind: discover structure similarity across the proteome in AlphaFold DB, Nucleic Acids Research , 2024;, gkae397, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae397

- Permissions Icon Permissions

AlphaFind is a web-based search engine that provides fast structure-based retrieval in the entire set of AlphaFold DB structures. Unlike other protein processing tools, AlphaFind is focused entirely on tertiary structure, automatically extracting the main 3D features of each protein chain and using a machine learning model to find the most similar structures. This indexing approach and the 3D feature extraction method used by AlphaFind have both demonstrated remarkable scalability to large datasets as well as to large protein structures. The web application itself has been designed with a focus on clarity and ease of use. The searcher accepts any valid UniProt ID, Protein Data Bank ID or gene symbol as input, and returns a set of similar protein chains from AlphaFold DB, including various similarity metrics between the query and each of the retrieved results. In addition to the main search functionality, the application provides 3D visualizations of protein structure superpositions in order to allow researchers to instantly analyze the structural similarity of the retrieved results. The AlphaFind web application is available online for free and without any registration at https://alphafind.fi.muni.cz .

Protein structural data are highly beneficial scientific resources that serve as the basis for ever-growing and valuable research. Thanks to seven decades of intensive research, we currently have >200 000 experimental protein 3D structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) ( 1 ). Furthermore, the AlphaFold algorithm ( 2 ), trained on these experimental data, produces highly reliable protein 3D structure predictions. As a result, the AlphaFold database has been published ( 3 ), containing >200 million 3D protein structures. In parallel, other databases of predicted protein 3D structures have been published, such as ESM Metagenomic Atlas ( 4 ), collecting 600 million protein 3D structures. Various research fields in bioinformatics benefit from such databases, with new cutting-edge technology on the horizon ( 5 ).

To take full advantage of this enormous amount of data, it is essential to organize them efficiently. Specifically, it is necessary to perform a structure-based search, because structural similarities frequently imply functional correspondence, even without high sequence similarity.