29 Jan 2024

Patent Assignment: How to Transfer Ownership of a Patent

By Michael K. Henry, Ph.D.

- Intellectual Property

- Patent Prosecution

This is the second in a two-part blog series on owning and transferring the rights to a patent. ( Read part one here. )

As we discussed in the first post in this series, patent owners enjoy important legal and commercial benefits: They have the right to exclude others from making, selling, using or importing the claimed invention, and to claim damages from anyone who infringes their patent.

However, a business entity can own a patent only if the inventors have assigned the patent rights to the business entity. So if your employees are creating valuable IP on behalf of your company, it’s important to get the patent assignment right, to ensure that your business is the patent owner.

In this post, we’ll take a closer look at what a patent assignment even is — and the best practices for approaching the process. But remember, assignment (or transfer of ownership) is a function of state law, so there might be some variation by state in how all this gets treated.

What Is a Patent Assignment and Why Does it Matter?

A patent assignment is an agreement where one entity (the “assignor”) transfers all or part of their right, title and interest in a patent or application to another entity (the “assignee”).

In simpler terms, the assignee receives the original owner’s interest and gains the exclusive rights to pursue patent protection (through filing and prosecuting patent applications), and also to license and enforce the patent.

Ideally, your business should own its patents if it wants to enjoy the benefits of the patent rights. But under U.S. law , only an inventor or an assignee can own a patent — and businesses cannot be listed as an inventor. Accordingly, patent assignment is the legal mechanism that transfers ownership from the inventor to your business.

Patent Assignment vs. Licensing

Keep in mind that an assignment is different from a license. The difference is analogous to selling versus renting a house.

In a license agreement, the patent owner (the “licensor”) gives another entity (the “licensee”) permission to use the patented technology, while the patent owner retains ownership. Like a property rental, a patent license contemplates an ongoing relationship between the licensor and licensee.

In a patent assignment, the original owner permanently transfers its ownership to another entity. Like a property sale, a patent assignment is a permanent transfer of legal rights.

U sing Employment Agreements to Transfer Patent Ownership

Before your employees begin developing IP, implement strong hiring policies that ensure your IP rights will be legally enforceable in future.

If you’re bringing on a new employee, have them sign an employment agreement that establishes up front what IP the company owns — typically, anything the employee invents while under your employment. This part of an employment agreement is often presented as a self-contained document, and referred to as a “Pre-Invention Assignment Agreement” (PIAA).

The employment agreement should include the following provisions:

- Advance assignment of any IP created while employed by your company, or using your company’s resources

- An obligation to disclose any IP created while employed by your company, or using your company’s resources

- An ongoing obligation to provide necessary information and execute documents related to the IP they created while employed, even after their employment ends

- An obligation not to disclose confidential information to third parties, including when the employee moves on to a new employer

To track the IP your employees create, encourage your employees to document their contributions by completing invention disclosure records .

But the paperwork can be quite involved, which is why your employment policies should also include incentives to create and disclose valuable IP .

Drafting Agreements for Non-Employees

Some of the innovators working for your business might not have a formal employer-employee relationship with the business. If you don’t make the appropriate arrangements beforehand, this could complicate patent assignments. Keep an eye out for the following staffing arrangements:

- Independent contractors: Some inventors may be self-employed, or they may be employed by one of your service providers.

- Joint collaborators: Some inventors may be employed by, say, a subsidiary or service company instead of your company.

- Anyone who did work through an educational institution : For example, Ph.D. candidates may not be employees of either their sponsoring institution or your company.

In these cases, you can still draft contractor or collaborator agreements using the same terms outlined above. Make sure the individual innovator signs it before beginning any work on behalf of your company.

O btaining Written Assignments for New Patent Applications

In addition to getting signed employment agreements, you should also get a written assignments for each new patent application when it’s filed, in order to memorialize ownership of the specific patent property.

Don’t rely exclusively on the employment agreement to prove ownership:

- The employment agreement might contain confidential terms, so you don’t want to record them with the patent office

- Because employment agreements are executed before beginning the process of developing the invention, they won’t clearly establish what specific patent applications are being assigned

While you can execute the formal assignment for each patent application after the application has been filed, an inventor or co-inventor who no longer works for the company might refuse to execute the assignment.

As such, we recommend executing the assignment before filing, to show ownership as of the filing date and avoid complications (like getting signatures from estranged inventors).

How to Execute a Written Patent Agreement

Well-executed invention assignments should:

- Be in writing: Oral agreements to assign patent rights are typically not enforceable in the United States

- Clearly identify all parties: Include the names, addresses, and relationship of the assignor(s) and assignee

- Clearly identify the patent being assigned: State the patent or patent application number, title, inventors, and filing date

- Be signed by the assignors

- Be notarized : If notarization isn’t possible, have one or two witnesses attest to the signatures

Recording a Patent Assignment With the USPTO

Without a recorded assignment with the U.S. patent office, someone else could claim ownership of the issued patent, and you could even lose your rights in the issued patent in some cases.

So the patent owner (the Assignee) should should record the assignment through the USPTO’s Assignment Recordation Branch . They can use the Electronic Patent Assignment System (EPAS) to file a Recordation Cover Sheet along with a copy of the actual patent assignment agreement.

They should submit this paperwork within three months of the assignment’s date. If it’s recorded electronically, the USPTO won’t charge a recordation fee .

Need to check who owns a patent? The USPTO website publicly lists all information about a patent’s current and previous assignments.

When Would I Need to Execute a New Assignment for a Related Application?

You’ll need only one patent assignment per patent application, unless new matter is introduced in a new filing (e.g., in a continuation-in-part , or in a non-provisional application that adds new matter to a provisional application ). In that case, you’ll need an additional assignment to cover the new matter — even if it was developed by the same inventors.

What If an Investor Won’t Sign the Written Assignment?

If you can’t get an inventor to sign an invention assignment, you can still move forward with a patent application — but you’ll need to document your ownership. To document ownership, you can often rely on an employee agreement , company policy , invention disclosure , or other employment-related documentation.

D o I Need to Record My Assignments in Foreign Countries?

Most assignments transfer all rights, title, and interest in all patent rights throughout the world.

But in some countries, the assignment might not be legally effective until the assignment has been recorded in that country — meaning that the assignee can’t enforce the patent rights, or claim damages for any infringement that takes place before the recordation.

And there might be additional formal requirements that aren’t typically required in the United States. For example, some countries might require a transfer between companies to be signed by both parties, and must contain one or both parties’ addresses.

If you’re assigning patents issued by a foreign country, consult a patent attorney in that country to find out what’s required to properly document the transfer of ownership.

N eed Help With Your Patent Assignments?

Crafting robust assignment agreements is essential to ensuring the proper transfer of patent ownership. An experienced patent professional can help you to prepare legally enforceable documentation.

Henry Patent Law Firm has worked with tech businesses of all sizes to execute patent assignments — contact us now to learn more.

GOT A QUESTION? Whether you want to know more about the patent process or think we might be a good fit for your needs – we’d love to hear from you!

Michael K. Henry, Ph.D.

Michael K. Henry, Ph.D., is a principal and the firm’s founding member. He specializes in creating comprehensive, growth-oriented IP strategies for early-stage tech companies.

10 Jan 2024

Geothermal Energy: An Overview of the Patent Landscape

By Michael Henry

Don't miss a new article. Henry Patent Law's Patent Law News + Insights blog is designed to help people like you build smart, scalable patent strategies that protect your intellectual property as your business grows. Subscribe to receive email updates every time we publish a new article — don't miss out on key tips to help your business be more successful.

Extracted from Law360

Parties seeking to transfer ownership of a patent subject to preexisting licenses often face a difficult task.

On the one hand, the patent owner may desire to obtain the benefits of those prior licenses even after the patent is assigned to a new owner.

On the other, any rights retained by the patent owner, and any restrictions placed on the future assignee, may jeopardize the standing of the assignee to enforce the patent without joining the former owner.

To further complicate this delicate balance, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit's decision in Lone Star Silicon Innovations LLC v. United Microelectronics Corp., and subsequent district court cases applying that decision, have looked to the totality of the contract at issue to determine whether the assignee has standing, subjecting any contractual restrictions on the assignees' rights to further scrutiny.

It is therefore useful to determine which encumbrances must be contractually imposed (and subjected to additional scrutiny) and which are automatically transferred to the assignee when it steps into the shoes of the assignor. It is well-settled that an assignee takes a patent subject to any preexisting encumbrances that run with the patent. But what does it mean to run with the patent? And how should an assignor ensure that future transferees are bound by those provisions?

An Overview of What Runs With the Patent

Patents are, by definition, the right to exclude others from using an invention. When the patent owner has given up the right to exclude another entity through the grant of a license or covenant not to sue, it cannot then transfer that right to exclude to another party. This is true regardless of whether the assignee is aware of the prior actions by the patent owner. In other words, a patent owner cannot assign more rights than it possesses.

The patent owner may also have contractual obligations, or even incentives, to protect those prior license grants. Consequently, it may want to shield the earlier licensees by reserving rights for itself, or imposing restrictions on future purchasers.

This dilemma is further complicated by standing considerations. Courts across the country have grappled with what rights a licensee must possess to have standing to sue for patent infringement. The generally accepted principle is that the licensee must have all substantial rights to sue in its own name.[1] Courts look at the totality of the agreement, i.e., all provisions and their cumulative effect on substantial rights. Courts tend to focus, however, on restrictions that impair enforcement and alienation.

Thus, particular care should be taken when imposing contractual limitations on an assignee's ability to enforce the patent or further transfer the rights it obtains. The line between a preexisting encumbrance that runs with the patent and a substantial right retained by the former patent owner is often difficult to ascertain.

In the recent Lone Star case, the Federal Circuit considered an agreement that restricted assignee Lone Star's ability to enforce or assign the patents without consent of the patent owner, and it further restricted Lone Star's ability to transfer the patents unless the subsequent buyer agreed to be bound by the same restrictions as Lone Star. The court concluded that, when viewed in the totality, Lone Star lacked all substantial rights and thus had standing to sue only if it joined the original patent owner.

Since the Lone Star decision, district courts have examined contractual restrictions to determine whether transferees had all substantial rights necessary to maintain suit without joining the respective patent owners. For example, following Lone Star, district courts have refused to allow an assignee to sue in its own name where the assignee was required to obtain consent prior to filing suite against two specific entities.[2]

As a result of the uncertainty surrounding standing to sue when preexisting rights exist, patent owners looking to assign future rights are wise to consider which rights and obligations automatically transfer and which ones must be contractually imposed.

And for any encumbrances that are imposed contractually, the impact on the assignee's standing to sue should be assessed. Ultimately, patent owners need to assess the relative risks of protecting their existing licensing arrangements against the possibility that doing so will result in the loss of the assignor's independent standing to sue.

Encumbrances That Run With the Patent

As a general rule, only those encumbrances that relate to the actual use of the patent are deemed to run with that right to exclude. The most common encumbrances of this type are those that restrict the ability to use an invention, including explicit licenses authorizing use, and covenants not to sue to enforce a patent right. Once granted, the patent owner's exclusionary rights against the receiving party are diminished. A subsequent assignee then takes a patent subject to those existing licenses and covenants not to sue.[3]

But the term license in this context can be misleading. Most patent license agreements contain not only provisions granting rights to use the patent at issue but also other provisions governing payment (through running royalties or lump sums), dispute resolution, confidentiality and many other issues. A common misperception is that the entire license runs with the patent and therefore binds subsequent assignees, but sellers — and buyers — should beware.

In contrast to license grants and covenants not to sue that impact use of an invention and run with the patent, procedural terms in a licensing agreement that do not directly impact the use of the patent may not be binding on subsequent buyers. Yet the outcome of such provisions is often unclear.

Arbitration Clauses

The Federal Circuit has held that arbitration clauses do not run with the patent because they are unrelated to the actual use of the patent.[4] Instead, these provisions are viewed as features of the underlying contract negotiated by the original parties that do not bind any subsequent patent owner unless that restriction is imposed as part of the contractual patent assignment.

Confidentiality Provisions

Patent license agreements often contain contractual obligations to keep terms of the agreement confidential. Courts have classified confidentiality provisions as procedural terms that do not bind subsequent assignees.[5] Like arbitration clauses, confidentiality provisions relate to the contractual obligations between the negotiating parties, rather than the patent itself, and again generally do not run with the patent upon transfer.

Licenses to use a patent are often directly conditioned on royalty payments for that use. Similarly, patent assignments sometimes require payment of royalties to the original patent owner for future enforcement actions brought by the assignee. While royalty rights may seem to run with the patent — as the commercial benefit of the grant of a right to use the patented invention — some courts have found they do not.[6] These courts have reasoned that the royalty payments are personal between the contracting parties and thus do not bind future assignees.

This outcome is particularly concerning if a patent is assigned to a party in return for a share of future royalties earned by the new patent owner. If that new patent owner subsequently assigns the patent to a third party, the original owner may not have any recourse against that third party to enforce its royalty rights absent a separate contractual arrangement that binds the future assignee.

Not all courts have reached the same conclusion, however. At least one court has distinguished between past royalties, which are not transferred, and future royalties, which are transferred.[7] The court explained that the assignee of a patent becomes vested with the rights of the patentee, but also takes the patent subject to the patentee's previous acts. Under this view, royalties due after the transfer are incident to and transferred with the patent absent an express reservation.

That presumption is reversed with previously accrued royalties though. The right to recover prior royalties or damages for prior infringement may be assigned, but the assignment of a patent without more is not sufficient to confer those rights on the assignee.

Practice Recommendations

Only those encumbrances deemed to run with the patent — those that relate to the actual use of the patent — are likely to bind successors in interest. Potential buyers should perform due diligence on the patents to determine whether the patents are subject to any preexisting licenses or covenants not to sue. Even if the patent owner does not inform the potential buyer of such commitments, they will likely bind the buyer after transfer.

To the extent a patent owner wants (or is contractually obligated) to ensure that existing encumbrances continue to bind future assignees of the patent, it should make sure that all restrictions not specifically tied to the use of the patent are contractually imposed on future assignees.

Such provisions preserve the patent owner's breach of contract rights against the original licensee should that licensee transfer the agreement without the obligations it was required to include. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that any contractual restrictions do not result in the retention of a substantial right that impedes the assignees' standing to sue future infringers.

[1] Lone Star Silicon Innovations LLC v. United Microelectronics Corp. , UMC Grp. (USA), 925 F.3d 1225 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

[2] Home Semiconductor Corp. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd. , No. 13-cv-2033, 2020 WL 1470867 (D. Del. Mar. 26, 2020).

[3] Innovus Prime, LLC v. Panasonic Corp. , No. C-12-00660, 2013 WL 3354390 (N.D. Cal. July 2, 2013).

[4] Datatreasury Corp. v. Wells Fargo & Co. , 522 F.3d 1368, 1372-73 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

[5] Paice, LLC v. Hyundai Motor Co. , No. 12-499, 2014 WL 3533667, at *9-10 (D. Md. July 11, 2014).

[6] In re Particle Drilling Techs., Inc. , No. 09-33744, 2009 WL 2382030 (S.D. Tex. July 29, 2009); Jones v. Cooper Indus., Inc. , 938 S.W.2d 118 (14th Dist. Tex. 1996).

[7] In re Novon Int'l, Inc. v. Novamont S.P.A. , Nos. 98-cv-677E(F), 96-BK-15463B, 2000 WL 432848, at *5 (W.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2000).

- General Publications October 5, 2020 “What Ethernet Patent Ruling Means for Claim Amendments,” Law360 , October 5, 2020. Continuation practice is as popular as ever at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. This is due, at least in part, to the potential for patent challenges before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). This article examines the considerations for both patent owner and challenger for continuation applications stemming from PTAB patent challenges.

- Patent Case Summaries June 4, 2019 Patent Case Summaries | Week Ending May 31, 2019 A weekly summary of the precedential patent-related opinions issued by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and the opinions designated precedential or informative by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.

- Intellectual Property Litigation

- Trademark & Copyright

- Patent Prosecution, Counseling & Review

This website uses cookies to improve functionality and performance. For more information, see our Privacy Statement . Additional details for California consumers can be found here .

This patent assignment is between , an individual a(n) (the " Assignor ") and , an individual a(n) (the " Assignee ").

The Assignor has full right and title to the patents and patent applications listed in Exhibit A (collectively, the " Patents ").

The Assignor wishes to transfer to the Assignee, and the Assignee wishes to purchase and receive from the Assignor, all of its interest in the Patents.

The parties therefore agree as follows:

1. ASSIGNMENT OF PATENTS.

The Assignor assigns to the Assignee, and the Assignee accepts the assignment of, all of the Assignor's interest in the following in the United States and its territories and throughout the world:

- (a) the Patents listed in Exhibit A ;

- (b) the patent claims, all rights to prepare derivative works, goodwill, and other rights to the Patents;

- (c) all registrations, applications (including any divisions, continuations, continuations-in-part, and reissues of those applications), corresponding domestic and foreign applications, letters patents, or similar legal protections issuing on the Patents, and all rights and benefits under any applicable treaty or convention;

- (d) all income, royalties, and damages payable to the Assignor with respect to the Patents, including damages and payments for past or future infringements of the Patents; and

- (e) all rights to sue for past, present, and future infringements of the Patents.

2. CONSIDERATION.

The Assignee shall pay the Assignor a flat fee of as full payment for all rights granted under this agreement. The Assignee shall complete this payment no later than .

3. RECORDATION.

In order to record this assignment with the United States Patent and Trademark Office and foreign patent offices, within hours of the effective date of this assignment, the parties shall sign the form of patent assignment agreement attached as Exhibit B . The Assignor Assignee is solely responsible for filing the assignment and paying any associated fees of the transfer.

4. NO EARLY ASSIGNMENT.

The Assignee shall not assign or otherwise encumber its interest in the Patents or any associated registrations until it has paid to the Assignor the full consideration provided for in this assignment. Any assignment or encumbrance contrary to this provision shall be void.

5. ASSISTANCE.

- (1) sign any additional papers, including any separate assignments of the Patents, necessary to record the assignment in the United States;

- (2) do all other lawful acts reasonable and necessary to record the assignment in the United States; and

- (3) sign all lawful papers necessary for Assignee to retain a patent on the Patents or on any continuing or reissue applications of those Patents.

- (b) Agency. If for any reason the Assignee is unable to obtain the assistance of the Assignor, the Assignor hereby appoints the Assignee as the Assignor's agent to act on behalf of the Assignor to take any of the steps listed in subsection (a).

6. NO LICENSE.

After the effective date of this agreement, the Assignor shall make no further use of the Patents or any patent equivalent, except as authorized by the prior written consent of the Assignee. The Assignor shall not challenge the Assignee's use or ownership, or the validity, of the Patents.

7. ASSIGNOR'S REPRESENTATIONS.

The Assignor hereby represents to the Assignee that it:

- (a) is the sole owner of all interest in the Patents;

- (b) has not transferred, exclusively licensed, or encumbered the Patents or agreed to do so;

- (c) is not aware of any violation or infringement of any third party's rights (or a claim of a violation or infringement) by the Patents;

- (d) is not aware of any third-party consents, assignments, or licenses that are necessary to perform under this assignment;

- (e) was not acting within the scope of employment of any third party when conceiving, creating, or otherwise performing any activity with respect to the Patents.

The Assignor shall immediately notify the Assignee in writing if any facts or circumstances arise that would make any of the representations in this assignment inaccurate.

8. INDEMNIFICATION.

The Assignor shall indemnify the Assignee against:

- (a) any claim by a third party that the Patents or their creation, use, exploitation, assignment, importation, or sale infringes on any patent or other intellectual property;

- (b) any claim by a third party that this assignment conflicts with, violates, or breaches any contract, assignment, license, sublicense, security interest, encumbrance, or other obligation to which the Assignor is a party or of which it has knowledge;

- (c) any claim relating to any past, present, or future use, licensing, sublicensing, distribution, marketing, disclosure, or commercialization of any of the Patents by the Assignor; and

- (d) any litigation, arbitration, judgments, awards, attorneys' fees, liabilities, settlements, damages, losses, and expenses relating to or arising from (a), (b), or (c) above.

- (i) the Assignee promptly notifies the Assignor of that claim;

- (ii) the Assignor controls the defense and settlement of that claim;

- (iii) the Assignee fully cooperates with the Assignor in connection with its defense and settlement of that claim;

- (iv) the Assignee stops all creation, public use, exploitation, importation, distribution, or sales of or relating to the infringing Patents, if requested by the Assignor.

- (i) obtain the right for the Assignee to continue to use the infringing Patent;

- (ii) modify the infringing Patent to eliminate the infringement;

- (iii) provide a substitute noninfringing patent to the Assignee pursuant to this assignment; or

- (iv) refund to the Assignee the amount paid under this assignment for the infringing Patent.

- (c) No Other Obligations. The Assignor shall have no other obligations or liability if infringement occurs, and shall have no other obligation of indemnification or to defend relating to infringement. The Assignor shall not be liable for any costs or expenses incurred without its prior written authorization and shall have no obligation of indemnification or any liability if the infringement is based on (i) any modified form of the Patents not made by the Assignor, (ii) any finding or ruling after the effective date of this assignment, or (iii) the laws of any country other than the United States of America or its states.

9. GOVERNING LAW.

- (a) Choice of Law. The laws of the state of govern this agreement (without giving effect to its conflicts of law principles).

- (b) Choice of Forum. Both parties consent to the personal jurisdiction of the state and federal courts in County, .

10. AMENDMENTS.

No amendment to this assignment will be effective unless it is in writing and signed by a party or its authorized representative.

11. ASSIGNMENT AND DELEGATION.

- (a) No Assignment. Neither party may assign any of its rights under this assignment, except with the prior written consent of the other party. All voluntary assignments of rights are limited by this subsection.

- (b) No Delegation. Neither party may delegate any performance under this assignment, except with the prior written consent of the other party.

- (c) Enforceability of an Assignment or Delegation. If a purported assignment or purported delegation is made in violation of this section, it is void.

12. COUNTERPARTS; ELECTRONIC SIGNATURES.

- (a) Counterparts. The parties may execute this assignment in any number of counterparts, each of which is an original but all of which constitute one and the same instrument.

- (b) Electronic Signatures. This assignment, agreements ancillary to this assignment, and related documents entered into in connection with this assignment are signed when a party's signature is delivered by facsimile, email, or other electronic medium. These signatures must be treated in all respects as having the same force and effect as original signatures.

13. SEVERABILITY.

If any one or more of the provisions contained in this assignment is, for any reason, held to be invalid, illegal, or unenforceable in any respect, that invalidity, illegality, or unenforceability will not affect any other provisions of this assignment, but this assignment will be construed as if those invalid, illegal, or unenforceable provisions had never been contained in it, unless the deletion of those provisions would result in such a material change so as to cause completion of the transactions contemplated by this assignment to be unreasonable.

14. NOTICES.

- (a) Writing; Permitted Delivery Methods. Each party giving or making any notice, request, demand, or other communication required or permitted by this assignment shall give that notice in writing and use one of the following types of delivery, each of which is a writing for purposes of this assignment: personal delivery, mail (registered or certified mail, postage prepaid, return-receipt requested), nationally recognized overnight courier (fees prepaid), facsimile, or email.

- (b) Addresses. A party shall address notices under this section to a party at the following addresses:

- If to the Assignor:

| , | |

- If to the Assignee:

- (c) Effectiveness. A notice is effective only if the party giving notice complies with subsections (a) and (b) and if the recipient receives the notice.

15. WAIVER.

No waiver of a breach, failure of any condition, or any right or remedy contained in or granted by the provisions of this assignment will be effective unless it is in writing and signed by the party waiving the breach, failure, right, or remedy. No waiver of any breach, failure, right, or remedy will be deemed a waiver of any other breach, failure, right, or remedy, whether or not similar, and no waiver will constitute a continuing waiver, unless the writing so specifies.

16. ENTIRE AGREEMENT.

This assignment constitutes the final agreement of the parties. It is the complete and exclusive expression of the parties' agreement about the subject matter of this assignment. All prior and contemporaneous communications, negotiations, and agreements between the parties relating to the subject matter of this assignment are expressly merged into and superseded by this assignment. The provisions of this assignment may not be explained, supplemented, or qualified by evidence of trade usage or a prior course of dealings. Neither party was induced to enter this assignment by, and neither party is relying on, any statement, representation, warranty, or agreement of the other party except those set forth expressly in this assignment. Except as set forth expressly in this assignment, there are no conditions precedent to this assignment's effectiveness.

17. HEADINGS.

The descriptive headings of the sections and subsections of this assignment are for convenience only, and do not affect this assignment's construction or interpretation.

18. EFFECTIVENESS.

This assignment will become effective when all parties have signed it. The date this assignment is signed by the last party to sign it (as indicated by the date associated with that party's signature) will be deemed the date of this assignment.

19. NECESSARY ACTS; FURTHER ASSURANCES.

Each party shall use all reasonable efforts to take, or cause to be taken, all actions necessary or desirable to consummate and make effective the transactions this assignment contemplates or to evidence or carry out the intent and purposes of this assignment.

[SIGNATURE PAGE FOLLOWS]

Each party is signing this agreement on the date stated opposite that party's signature.

Date: _________________ | __________________________________________ |

| Name: | |

Date: _________________ | __________________________________________ |

| Name: |

[PAGE BREAK HERE]

EXHIBIT A PATENTS AND APPLICATIONS

| add border | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

FORM OF RECORDABLE PATENT APPLICATION ASSIGNMENT

For good and valuable consideration, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, between , an individual a(n) (the " Assignor ") and , an individual a(n) (the " Assignee ") all of the Assignor's interest in the Assigned Patents identified in Attachment A to this assignment, and the Assignee accepts this assignment.

Each party is signing this agreement on the date stated opposite that party's signature.

Date: ________________________ | __________________________________________ |

| Name: | |

| NOTARIZATION: | |

| Date: ________________________ | __________________________________________ |

| Name: | |

| NOTARIZATION: |

ATTACHMENT A ASSIGNED PATENTS

| add border | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| **DATE(S) OF EXECUTIONOF DECLARATION ** | ||||

Free Patent Assignment Template

Simplify the process of transferring patent rights for both buyers and sellers with a patent assignment agreement. document the ownership transfer clearly and efficiently..

Complete your document with ease

How-to guides, articles, and any other content appearing on this page are for informational purposes only, do not constitute legal advice, and are no substitute for the advice of an attorney.

Patent assignment: How-to guide

A company’s ability to buy and sell property is essential for its long-term life and vitality. Although it doesn’t take up physical space, too much intellectual property can burden a company, directing limited funds towards maintaining registrations, defending against third-party claims, or creating and marketing a final product.

Selling unused or surplus intellectual property can have an immediate positive effect on a company’s finances, generating revenue and decreasing costs. When it does come time to grow a business, companies looking to purchase property (including patents and other inventions) to support their growth must be sure that the seller does have title to the desired items. A properly drafted patent assignment can help in these circumstances.

A patent assignment is the transfer of an owner’s property rights in a given patent or patents and any patent applications. These transfers may occur independently or as part of larger asset sales or purchases. Patent assignment agreements provide both records of ownership and transfer and protect the rights of all parties.

This agreement is a written acknowledgment of the rights and responsibilities being transferred as part of your sale. This will provide essential documentation of ownership and liability obligations, and you will be well on your way to establishing a clear record of title for all of your patents.

Important points to consider while drafting patent assignments

What is a patent.

A patent is a set of exclusive rights on an invention given by the government to the inventor for a limited period. Essentially, in exchange for the inventor’s agreement to make their invention public and allow others to examine and build on it, the government provides the inventor with a short-term monopoly on their creation. In other words, only they can make, use, or sell that invention.

Are licenses and assignments different from each other?

Licenses are different from assignments. The individual who receives license rights from the patent holder isn’t gaining ownership. Rather, they’re getting assurance from the patent holder that they won’t be sued for making, using, or selling the invention. The terms of the license will vary from agreement to agreement and may address issues of royalties, production, or reversion.

What are the different kinds of patent assignments?

A patent assignment can take many forms.

- It can be the transfer of an individual’s entire interest to another individual or company.

- It can also transfer a specific part of that interest (e.g., half interest, quarter interest, etc.) or a transfer valid only in a designated country area. The exact form of the transfer is specific to the parties' agreement.

What is the role of the United States Patent and Trademark Office in patent transfer?

A patent transfer is usually accomplished through a contract, like the following written agreement form. However, after the parties have negotiated and signed their agreement, the transfer must be recorded with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) . The agreement will only be effective if this registration is made. Moreover, if the transfer isn’t recorded within three months from the date of the assignment, there can be no later purchasers. In other words, such patents are no longer sellable to a third party by the assignee if it isn’t recorded quickly and correctly.

Note that there is a fee for recording each assignment of a patent or patent application.

What details should I add to my patent application?

Although you can adapt the document to suit your arrangement, you should always identify the patent(s) being assigned by their USPTO number and date and include the name of the inventor and the invention’s title (as stated in the patent itself). This is a requirement of federal law, and failure to follow it could invalidate your assignment.

What are the benefits of patent assignment?

The advantage of selling your invention or patent outright (and not simply licensing or attempting to develop and market it yourself) is that you’re guaranteed payment at the price you and the purchaser have negotiated.

On the other hand, that one-time payment is all that you will ever receive for your property. You will no longer have the right to control anyone else’s use of your creation.

By using it yourself or offering a temporary license, you retain the potential for future income. However, such income isn’t certain, and your opportunities are paralleled by risk.

Before selling all of your rights in a patent or patent application, ensure this is the best (and most lucrative) approach for you and your company.

Is it necessary to do due diligence before buying a patent?

Provide valuable consideration to due diligence, and don’t agree without completing it. If you purchase a patent, conduct searches with the patent office on the patents issued and online directories to ensure the seller has complete and unique rights in the offered property. Look for these:

- Has an application already been filed by another person or company?

- What are the chances that this is a patentable item?

Although your findings won’t be guaranteed, you may be protected as an “innocent purchaser” if disputes arise.

You might also find critical information about the value of the patent. Consider hiring a patent attorney to help in your investigation. Comparing patents and applications often requires a specialized and technical understanding to know how useful and unique each one is.

What should I consider while selling a patent?

If you sell an invention or patent, ensure you own it. Although this may seem obvious, intellectual property ownership sometimes must be clarified. This may be the case if, for example, the invention was created as part of your employment or if it was sold or otherwise transferred to somebody else. A thorough search of the USPTO website for the publication number should be conducted before you attempt to sell your property.

Is reviewing and signing the patent necessary?

Review the assignment carefully to ensure all relevant deal points are included. Don't assume certain terms are agreed upon if not stated in the document.

Once the document is ready, sign two copies of the assignment, one for you and one for the other party.

Get the assignment notarized by the notary public to reduce the challenges to the validity of a party’s signature or the transfer itself.

If you’re dealing with a complex agreement for a patent assignment , contact an attorney to help draft an assignment that meets your needs.

Key components to include in patent assignments

The following provisions will help you understand the terms of your assignment. Please review the entire document before starting your step-by-step process.

Introduction of parties

This section identifies the document as a patent assignment. Add the assignment effective date, parties involved, and what type of organization(s) they are. The “assignor” is the party giving their ownership interest, and the “assignee” is the party receiving it.

The “whereas” clauses, or recitals, define the world of the assignment and offer key background information about the parties. In this agreement, the recitals include a simple statement of the intent to transfer rights in the patent. Remember that the assignor can transfer all or part of its interest in the patents.

Assignment of patents

This section constitutes the assignment and acceptance of patents and inventions. Be as complete and clear as possible in your description of the property being transferred.

Consideration

In most agreements, each party is expected to do something. This obligation may be to perform a service, transfer ownership of property, or pay money. In this case, the assignee gives money (sometimes called “consideration”) to receive the assignor’s property. Enter the amount to be paid, and indicate how long the assignee has to make that payment after the agreement is signed.

Authorization to a director

This section is the assignor’s authorization to issue patents in the assignee’s name. In other words, this tells the head of the patent and trademark office that the transfer is valid and that ownership is changing hands by the assignment.

If the assignment is being recorded after the USPTO has issued a patent number, add the patent application number here.

Assignor’s representations and warranties

In this section, the assignor is agreeing to the following terms:

- They’re the sole owner of the inventions and the patents. If there are other owners who aren’t transferring their interests, this means that the only part being transferred is the assignor’s part.

- They haven’t sold or transferred the inventions and the patents to any third party.

- They have the authority to enter the agreement.

- They don’t believe that the inventions and the patents have been taken from any third party without authorization (e.g., a knowing copy of another company’s invention).

- They don’t know if any permissions must be obtained for the assignment to be completed. In other words, once the agreement is signed, the assignment will be effective without anyone else’s input.

- The patents weren’t created while a third party employed the creator. In many cases, if a company employs an individual and comes up with a product, the company will own that product. This section offers assurance to the assignee that there are no companies that will make that claim about the patents being sold.

If you and the other party want to include additional representations and warranties, you can do so here.

Assignee’s representations and warranties

In this section, the assignee is agreeing to the following terms:

- They have the authority to enter into the agreement

- They have enough funds to pay for the assignment

No early assignment

This section prevents the assignee from re-transferring the inventions or patents or using any of them as collateral for loans until it has completely paid the money due under the agreement.

Documentation

This clause is the assignor’s promise to help with any paperwork needed to complete an assignment, such as filing information about the assignment with the USPTO, transferring document titles, transferring paperwork for filing to foreign countries, etc.

No further use of inventions or patents

This section indicates that after the agreement’s filing date, the assignor will stop using all the inventions and patents being transferred and won’t challenge the assignee’s use of those inventions or patents.

Indemnification

This clause describes each party’s future obligations if the patent or any application is found to infringe on a third party’s rights. Either the assignor agrees to take all responsibility for infringement, promising to pay all expenses and costs relating to the claim, or the assignor makes its responsibilities conditional, significantly limiting its obligations if a claim is brought.

Successors and assigns

This section states that the parties’ rights and obligations will be passed on to successor organizations (if any) or organizations to which rights and obligations have been permissibly assigned.

No implied waiver

This clause explains that even if one party allows the other to ignore or break an obligation under the agreement, it doesn’t mean that the party waives any future rights to require the other to fulfill those (or any other) obligations.

Provide the assignor and assignee’s address where all the official or legal correspondence should be delivered.

Governing law

This provision lets the parties choose the state laws used to interpret the document.

Counterparts; electronic signatures

This section explains that if the parties sign the agreement in different locations, physically or electronically, all the separate pieces will be considered part of the same agreement.

Severability

This clause protects the terms of the agreement as a whole, even if one part is later invalidated. For example, if a state law is passed prohibiting choice-of-law clauses, it won’t undo the entire agreement. Instead, only the section dealing with the choice of law would be invalidated, leaving the remainder of the assignment enforceable.

Entire agreement

This section indicates the parties’ agreement that the document they’re signing is “the agreement” about transferring the issued patent.

This clarifies that the headings at the beginning of each section are meant to organize the document and shouldn’t be considered operational parts of the note .

Frequently asked questions

What is a patent assignment .

If you want to buy patents, the first step is to ensure the seller (original owner) owns the patent rights. The second step is the transfer of the patent owner's rights to the buyer. Patent assignments are agreements that cover both steps, helping the buyer and the seller with ownership records and quickly enabling transfer.

What are the requirements for patent assignment?

Here's the information you'll require to complete a patent assignment:

- Who the assignor is : Have their name and contact information ready

- Who the assignee is : Have their information available

- Invention info : Know the inventor's name, invention's registration number, and filing date

Related templates

Assignment of Agreement

Transfer work responsibilities efficiently with an assignment of agreement. Facilitate a smooth transition from one party to another.

Copyright Assignment

Protect your intellectual property with a copyright assignment form. Securely transfer your copyright to another party, clearly defining ownership terms while preserving your rights effectively.

Intellectual Property Assignment Agreement

Safeguard the sale or purchase of assets with an intellectual property assignment agreement. Transfer the ownership of patents, trademarks, software, and other critical assets easily.

Patent Application Assignment

Transfer the ownership rights or interests in a patent application. A patent application agreement defines the terms of transfer, promotes collaboration, and mitigates risks.

Trademark Assignment

Simplify the buying and selling of trademarks with a trademark assignment agreement. Transfer intellectual property rights and ensure a fair and smooth transaction.

Trademark License Agreement

Ensure fair use of intellectual property with a trademark license agreement. Outline the terms of usage and compensation.

IP Assignment and Licensing

IP rights have essentially transformed intangibles (knowledge, creativity) into valuable assets that you can put to strategic use in your business. You can do this by directly integrating the IP in the production or marketing of your products and services, thereby strengthening their competitiveness. With IP assignement and IP licensing, IP owners can also use your IP rights to create additional revenue streams by selling them out, giving others a permission to use them, and establishing joint ventures or other collaboration agreements with others who have complementary assets.

Expert tip: Assignment, license and franchising agreements are flexible documents that can be adapted to the needs of the parties. Nevertheless, most countries establish specific requirements for these agreements, e.g. written form, registration with a national IP office or other authority, etc. For more information, consult your IP office .

IP rights assignment

You can sell your IP asset to another person or legal entity.

When all the exclusive rights to a patented invention, registered trademark, design or copyrighted work are transferred by the owner to another person or legal entity, it is said that an assignment of such rights has taken place.

Assignment is the sale of an IP asset. It means that you transfer ownership of an IP asset to another person or legal entity.

IP for Business Guides

Learn more about the commercialization of patents, trademarks, industrial designs, copyright.

Read IP for Business Guides

IP licensing

You can authorize someone else to use your IP, while maintaining your ownership, by granting a license in exchange for something of value, such as a monetary lump sum, recurrent payments (royalties), or a combination of these.

Licensing provides you with the valuable opportunity to expand into new markets, add revenue streams through royalties, develop partnerships etc.

If you own a patent, know-how, or other IP assets, but cannot or do not want to be involved in all the commercialization activities (e.g. technology development, manufacturing, market expansion, etc.) you can benefit from the licensing of your IP assets by relying on the capacity, know-how, and management expertise of your partner.

Expert tip: Licensing can generally be sole, exclusive or non-exclusive, depending on whether the IP owner retains some rights, or on whether the IP rights can be licensed to one or multiple parties.

Technology licensing agreements

Trademark licensing agreements, copyright licensing agreements, franchising agreements, merchande licensing, joint venture agreements, find out more.

- Learn more about Technology Transfer .

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Intellectual Property Licensing and Transactions

- > Ownership and Assignment of Intellectual Property

Book contents

- Intellectual Property Licensing and Transactions

- Copyright page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Introduction to Intellectual Property Licensing

- 1 The Business of Licensing

- 2 Ownership and Assignment of Intellectual Property

- 3 The Nature of an Intellectual Property License

- 4 Implied Licenses and Unwritten Transactions

- 5 Confidentiality and Pre-license Negotiations

- Part II License Building Blocks

- Part III Industry- and Context-Specific Licensing Topics

- Part IV Advanced Licensing Topics

2 - Ownership and Assignment of Intellectual Property

from Part I - Introduction to Intellectual Property Licensing

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 June 2022

Chapter 2 covers issues surrounding the assignment of IP (i.e., fixing its ownership as a prerequisite to transacting in it), and contrasts ownership with licensing of IP. It specifically covers the assignment of rights in patents, copyrights, trademarks and trade secrets, including within the employment context (i.e., shop rights , individuals hired to invent and works made for hire). The Supreme Court decision in Stanford v. Roche is considered at length. The chapter concludes with a thorough discussion of the issues presented by joint ownership of IP.

Summary Contents

2.1 Assignments of Intellectual Property, Generally 19

2.2 Assignment of Copyrights and the Work Made for Hire Doctrine 22

2.3 Assignment of Patent Rights 27

2.4 Trademark Assignments and Goodwill 37

2.5 Assignment of Trade Secrets 41

2.6 Joint Ownership 42

The owner of an intellectual property (IP) right, whether a patent, copyright, trademark, trade secret or other right, has the exclusive right to exploit that right. Ownership of an IP right is thus the most effective and potent means for utilizing that right. But what does it mean to “own” an IP right and how does a person – an individual or a firm – acquire ownership of it? This chapter explores transfers and assignments of IP ownership, first in general, and then with respect to special considerations pertinent to patents, copyrights and trademarks. Assignments and transfers of IP licenses , another important topic, are covered in Section 13.3 , and attempts to prohibit an assignor of IP from later challenging the validity of transferred IP (through a contractual no-challenge clause or the common law doctrine of “assignor estoppel”) are covered in Chapter 22 .

2.1 Assignments of Intellectual Property, Generally

Once it is in existence, an item of IP may be bought, sold, transferred and assigned much as any other form of property. Like real and personal property, IP can be conveyed through contract, bankruptcy sale, will or intestate succession, and can change hands through any number of corporate transactions such as mergers, asset sales, spinoffs and stock sales.

The following case illustrates how IP rights will be treated by the courts much as any other assets transferred among parties. In this case, the court must interpret a “bill of sale,” the document listing assets conveyed in a particular transaction. Just as with bushels of grain or tons of steel, particular IP rights can be listed in a bill of sale and the manner in which they are listed will determine what the buyer receives.

Systems Unlimited v. Cisco Systems

228 fed. appx. 854 (11th cir. 2007) (cert. denied).

Following the settlement of a dispute between Systems Unlimited, Inc. and Cisco Systems, Inc. over the ownership of certain intellectual property, Cisco agreed to covey the property to Systems. In the resulting bill of sale, Cisco:

granted, bargained, sold, transferred and delivered, and by these presents does grant, bargain, sell, transfer and deliver unto [Systems], its successor and assigns, the following:

Any and all of [Cisco]’s right, title and interest in any copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade secrets and other intellectual property of any kind associated with any software, code or data, including without limitation host controller software and billing software, whether embedded or in any other form (including without limitations, disks, CDs and magnetic tapes), and including any and all available copies thereof and any and all books and records related thereto by [Cisco]

Cisco never delivered [copies of] any of the software to Systems. Alleging that it had been damaged by the non-delivery, Systems sued Cisco for breaching the bill of sale contract and for violating the attendant obligations to deliver the software under the Uniform Commercial Code.

Systems contends that the district court erred in granting summary judgment in favor of Cisco because: (1) the plain language of the bill of sale required Cisco to deliver the software; (2) the bill of sale, when read in conjunction with other contemporaneous agreements, required delivery; and (3) the UCC, which governs the bill of sale, requires that all goods be delivered at a reasonable time. Systems is wrong on each point.

The bill of sale is interpreted in accord with its plain language absent some ambiguity. Here, the parties agree that the bill of sale is clear and unambiguous.

The bill of sale provides that Cisco will “grant, bargain, sell, transfer and deliver unto [Systems] … [a]ny and all of [Cisco]’s right, title and interest in any copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade secrets and other intellectual property of a kind associated with any software, code or data.” As the district court explained, this language unambiguously means that Cisco was required by the bill of sale to transfer to Systems all of its rights in intellectual property associated with certain software and data. There is no mention in the plain language of the contract itself of Cisco being obligated to transfer the actual software, and we will not imply any such obligation absent some good reason under law.

Systems says there are two good reasons to imply an obligation by Cisco to transfer the software. First, Systems argues that the bill of sale must be interpreted in conjunction with the settlement agreement between Systems and Cisco and other documents relating to the intellectual property. These other agreements, Systems claims, include an obligation by Cisco to deliver the software with any conveyance of intellectual property.

Assuming without deciding that the other agreements include language requiring Cisco to deliver the software, they are not relevant here because Systems has never alleged Cisco violated these other agreements. Systems’ complaint alleges only a violation of the bill of sale contract, and there is no obligation in that contract to deliver the software. The bill of sale does not reference or incorporate any other agreement.

To get around this point, Systems argues that “when instruments relate to the same matters, are between the same parties, and made part of substantially one transaction, they are to be taken together.” It is true that this is one of the canons for construing a contract under California law. But it is also true that this canon, as with most others, is inapplicable where the contract that is alleged to have been breached is unambiguous. Here, the language of the bill of sale is unambiguous. Thus, there is no need to apply any canons of construction.

Systems also argues that the UCC imposes a duty on Cisco to deliver the software. We will assume without deciding that Systems’ reading of the UCC is correct. Even so, the provisions of the UCC only apply to contracts that deal predominately with “transactions in goods.” The sale of intellectual property, which is what is involved here, is not a transaction in goods. Thus, the UCC does not apply. Accordingly, the plain language of the bill of sale governs and, as the district court held, it does not include a provision requiring Cisco to deliver any software.

Notes and Questions

1. IP and the UCC . The court in Systems v. Cisco holds that IP licenses and other transactions are not governed by Article 2 of the UCC, which pertains to sales of goods. In Section 3.4 we will discuss whether and to what degree Article 2 applies to IP licenses . But this case relates not to a license, but to a “sale” of software. Why doesn’t UCC Article 2 apply? Should it?

2. Delivery of what ? What does this language from the bill of sale refer to, if not delivery of software: “including any and all available copies thereof”? Does this language represent a drafting mistake by Systems’ attorney? Or an intentional omission by Cisco?

3. The need for software . Why is Systems so upset that Cisco has allegedly refused to deliver the software in question? How useful is an assignment of copyright and other IP to someone who is not in possession of the software code that is copyrighted? Has Cisco “pulled a fast one” on Systems and the court, or is there a valid business reason that could justify Cisco’s failure to deliver the software ?

4. Statute of frauds . Assignments of copyrights, patents and trademarks must all be in writing (17 U.S.C. § 204(a), 35 U.S.C. § 261, 15 U.S.C. § 1060(3)). Why? This requirement does not apply to most licenses, which may be oral. Can you think of a good reason for this distinction?

5. State law and mutual mistake . Despite the federal statutory nature of patents, courts have long held that the question of who holds title to a patent is a matter of state contract law. Footnote 1 This issue arose in an interesting way in Schwendimann v. Arkwright Advanced Coating, Inc ., 959 F.3d 1065 (Fed. Cir. 2020). In Schwendimann , the plaintiff’s former company purported to assign her a patent application in 2003. Due to a clerical error by the law firm handling the matter, the assignment document filed with the patent office listed the wrong patent name and number. In 2011, the plaintiff filed an action asserting the patent against an alleged infringer. The defendant, discovering the incorrect assignment document from 2003, moved to dismiss on the ground that the plaintiff did not hold any enforceable rights at the time she filed suit and thus lacked standing. The district court, interpreting applicable state law, held that the 2003 assignment was the result of a “mutual mistake of fact” that did not accurately reflect the intent of the parties. Accordingly, the erroneous document could be reformed and was sufficient to support standing to bring suit. The Federal Circuit affirmed. Judge Reyna dissented, reasoning that, irrespective of the district court’s later reformation of the erroneous assignment, the plaintiff’s failure to own the patent at the time her suit was filed necessarily barred her suit under Article III of the Constitution. Which of these positions do you find more persuasive? Notwithstanding the holding in favor of the plaintiff, is there a claim for legal malpractice against the law firm in question ?

2.2 Assignment of Copyrights and the Work Made for Hire Doctrine

Under § 201(a) of the Copyright Act, copyright ownership “vests initially in the author or authors of the work.” A copyright owner may assign any of its exclusive rights, in full or in part, to a third party. The assignment generally must be in writing and signed by the owner of the copyright or his or her authorized agent (17 U.S.C. § 204(a)).

If a work of authorship is prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment, then the work is a “work made for hire” and the employer is considered the author and owner of the copyright (17 U.S.C. § 201(b)). In addition, if a work is not made by an employee but is “specially ordered or commissioned,” it will be considered a work made for hire if it falls into one of nine categories enumerated in § 101(2) of the Act: a contribution to a collective work, a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, a translation, a supplementary work, a compilation, an instructional text, a test, answer material for a test, or an atlas. Commissioned works that do not fall into one of these nine categories (for example, software) are not automatically considered to be works made for hire, and copyright must be assigned explicitly through a separate assignment or sale agreement.

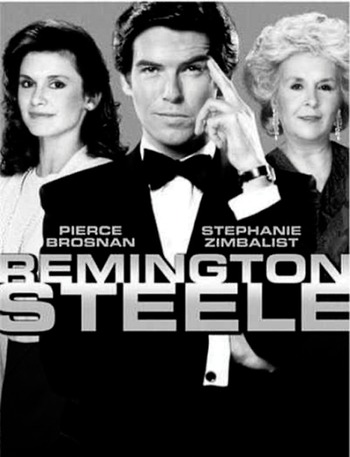

Warren v. Fox Family Worldwide, Inc.

328 f.3d 1136 (9th cir. 2003).

HAWKINS, Circuit Judge.

In this dispute between plaintiff-appellant Richard Warren (”Warren”) and defendants-appellees Fox Family Worldwide (“Fox”), MTM Productions (“MTM”), Princess Cruise Lines (“Princess”), and the Christian Broadcasting Network (“CBN”), Warren claims that defendants infringed the copyrights in musical compositions he created for use in the television series “Remington Steele.” Concluding that Warren has no standing to sue for infringement because he is neither the legal nor beneficial owner of the copyrights in question, we affirm the district court’s Rule 12 dismissal of Warren’s complaint.

Warren and Triplet Music Enterprises, Inc. (“Triplet”) entered into the first of a series of detailed written contracts with MTM concerning the composition of music for “Remington Steele.” This agreement stated that Warren, as sole shareholder and employee of Triplet, would provide services by creating music in return for compensation from MTM. Under the agreement, MTM was to make a written accounting of all sales of broadcast rights to the series and was required to pay Warren a percentage of all sales of broadcast rights to the series made to third parties not affiliated with ASCAP or BMI. These agreements were renewed and re-executed with slight modifications in 1984, 1985 and 1986.

Warren brought suit in propria persona against Fox, MTM, CBN, and Princess, alleging copyright infringement, breach of contract, accounting, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, breach of covenants of good faith and fair dealing, and fraud.

Warren claims he created approximately 1,914 musical works used in the series pursuant to the agreements with MTM; that MTM and Fox have materially breached their obligations under the contracts by failing to account for or pay the full amount of royalties due Warren from sales to parties not affiliated with ASCAP or BMI; and that MTM and Fox infringed Warren’s copyrights in the music by continuing to broadcast and license the series after materially breaching the contracts. As to the other defendants, Warren claims that CBN and Princess infringed his copyrights by broadcasting “Remington Steele” without his authorization. Warren seeks damages, an injunction, and an order declaring him the owner of the copyrights at issue.

Defendants argu[ed] that Warren’s infringement claims should be dismissed for lack of standing because he is neither the legal nor beneficial owner of the copyrights. The district court dismissed Warren’s copyright claims without leave to amend and dismissed his state law claims without prejudice to their refiling in state court, holding that Warren lacked standing because the works were made for hire, and because a creator of works for hire cannot be a beneficial owner of a copyright in the work. Warren appeals.

The first agreement [between the parties], signed on February 25, 1982, states that MTM contracted to employ Warren “to render services to [MTM] for the television pilot photoplay now entitled ‘Remington Steele.’” It also is clear that the parties agreed that MTM would “own all right, title and interest in and to [Warren’s] services and the results and proceeds thereof, and all other rights granted to [MTM] in [the Music Employment Agreement] to the same extent as if … [MTM were] the employer of [Warren].” The Music Employment Agreement provided:

As [Warren’s] employer for hire, [MTM] shall own in perpetuity, throughout the universe, solely and exclusively, all rights of every kind and character, in the musical material and all other results and proceeds of the services rendered by [Warren] hereunder and [MTM] shall be deemed the author thereof for all purposes.

Figure 2.1 Warren claimed that he created 1,914 musical works for the popular 1980s TV series Remington Steele .

The parties later executed contracts almost identical to these first agreements in June 1984, July 1985, and November 1986. As the district court noted, these subsequent contracts are even more explicit in defining the compositions as “works for hire.” Letters that Warren signed accompanying the later Music Employment Agreements provided: “It is understood and agreed that you are supplying [your] services to us as our employee for hire … [and] [w]e shall own all right, title and interest in and to [your] services and the results and proceeds thereof, as works made for hire.”

That the agreements did not use the talismanic words “specially ordered or commissioned” matters not, for there is no requirement, either in the Act or the caselaw, that work-for-hire contracts include any specific wording. In fact, in Playboy Enterprises v. Dumas , 53 F.3d 549 (2d Cir. 1995), the Second Circuit held that legends stamped on checks were writings sufficient to evidence a work-for-hire relationship where the legend read: “By endorsement, payee: acknowledges payment in full for services rendered on a work-made-for-hire basis in connection with the Work named on the face of this check, and confirms ownership by Playboy Enterprises, Inc. of all right, title and interest (except physical possession), including all rights of copyright, in and to the Work.” Id. at 560. The agreements at issue in the instant case are more explicit than the brief statement that was before the Second Circuit.

In this case, not only did the contracts internally designate the compositions as “works made for hire,” they provided that MTM “shall be deemed the author thereof for all purposes.” This is consistent with a work-for-hire relationship under the Act, which provides that “the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author.” 17 U.S.C. § 201(b).

Warren argues that the use of royalties as a form of compensation demonstrates that this was not a work-for-hire arrangement. While we have not addressed this specific question, the Second Circuit held in Playboy that “where the creator of a work receives royalties as payment, that method of payment generally weighs against finding a work-for-hire relationship.” 53 F.3d at 555. However, Playboy clearly held that this factor was not conclusive. In addition to noting that the presence of royalties only “generally” weighs against a work-for-hire relationship, Playboy cites Picture Music, Inc. v. Bourne, Inc ., 457 F.2d 1213, 1216 (2d Cir. 1972), for the proposition that “[t]he absence of a fixed salary … is never conclusive.” 53 F.3d at 555. Further, the payment of royalties was only one form of compensation given to Warren under the contracts. Warren was also given a fixed sum “payable upon completion.” That some royalties were agreed upon in addition to this sum is not sufficient to overcome the great weight of the contractual evidence indicating a work-for-hire relationship.

Warren also argues that because he created nearly 2,000 musical works for MTM, the works were not specially ordered or commissioned. However, the number of works at issue has no bearing on the existence of a work-for-hire relationship. As the district court noted, a weekly television show would naturally require “substantial quantities of verbal, visual and musical content.”

The agreements between Warren and MTM conclusively show that the musical compositions created by Warren were created as works for hire, and Warren is therefore not the legal owner of the copyrights therein.

1. Employee v. Contractor . In Warren v. Fox the musical compositions created by Warren fell into one of the nine categories of “specially commissioned works” that qualify as works made for hire under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act (audiovisual works), even if they were not made by employees of the commissioning party. They will thus be classified as works made for hire so long as they can be shown to have been “specially commissioned” – the focus of the debate in Warren . A slightly different question arose in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid , 490 U.S. 730 (1989). In that case Reid, a sculptor, was engaged by a nonprofit organization, CCNV, to create a memorial “to dramatize the plight of the homeless.” Sculpture is not one of the nine enumerated categories of commissioned works. Thus, even if Reid’s sculpture were “specially commissioned” (as it probably was), it would not be classified as a work made for hire under § 101 unless Reid were considered to be an employee of CCNV. CCNV argued that it exercised a certain degree of control over the subject matter of the sculpture, making it appropriate to classify Reid as its employee. The Court disagreed:

Reid is a sculptor, a skilled occupation. Reid supplied his own tools. He worked in his own studio in Baltimore, making daily supervision of his activities from Washington practicably impossible. Reid was retained for less than two months, a relatively short period of time. During and after this time, CCNV had no right to assign additional projects to Reid. Apart from the deadline for completing the sculpture, Reid had absolute freedom to decide when and how long to work. CCNV paid Reid $15,000, a sum dependent on completion of a specific job, a method by which independent contractors are often compensated. Reid had total discretion in hiring and paying assistants. Creating sculptures was hardly regular business for CCNV. Indeed, CCNV is not a business at all. Finally, CCNV did not pay payroll or Social Security taxes, provide any employee benefits, or contribute to unemployment insurance or workers’ compensation funds.

Does the structure of the works made for hire doctrine under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act make sense? Why should specially commissioned works be considered works for hire only if they fall into one of the nine enumerated categories? Why is a musical composition treated so differently than a sculpture?

2. Manner of compensation . The form of compensation received by the author is mentioned in both Warren v. Fox and CCNV v. Reid . Why is this detail significant to the question of works made for hire? Are the courts’ conclusions with respect to compensation consistent between these two cases?

3. Software contractors and assignment . For a variety of professional, financial and tax-planning reasons, software developers often work as independent contractors and are not hired as employees of the companies for which they create software. And, like the sculpture in CCNV v. Reid , software is not one of the nine enumerated categories of works under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act. Thus, even if it is specially commissioned, software will not be considered a work made for hire. As a result, companies that use independent contractors to develop software must be careful to put in place copyright assignment agreements with those contractors. And because contractors often sit and work beside company employees with very little to distinguish them, neglecting to take these contractual precautions is one of the most common IP missteps made by fledgling and mature software companies alike. If you were the general counsel of a new software company, how would you deal with this issue?

4. Recordation . Section 205 of the Copyright Act provides for recordation of copyright transfers with the Copyright Office. Recordation of transfers is not required, but provides priority if the owner attempts to transfer the same copyrighted work multiple times:

§ 205(d) Priority between Conflicting Transfers.—As between two conflicting transfers, the one executed first prevails if it is recorded, in the manner required to give constructive notice … Otherwise the later transfer prevails if recorded first in such manner, and if taken in good faith, for valuable consideration or on the basis of a binding promise to pay royalties, and without notice of the earlier transfer.

As students of real property will surely observe, this provision resembles a “race-notice” recording statute under state law. As such, the second transferee of a copyright may prevail over a prior, unrecorded transferee if the second transferee records first without notice of the earlier transfer. Note also that this provision is applicable only to copyrights that are registered with the Copyright Office.

5. Statutory termination of assignments . Sections 203 and 304 of the Copyright Act provide that any transfer of a copyright can be revoked by the transferor between 35 and 40 years after the original transfer was made. Footnote 2 This remarkable and powerful right is irrevocable and cannot be contractually waived or circumvented. It was intended to enable authors who were young and unrecognized when they first granted rights to more powerful publishers to profit from the later success of their works. For example, in 1938 Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, the creators of the Superman character, sold their rights to the predecessor of DC Comics for $130. Siegel and Shuster both died penniless in the 1990s, while Superman earned billions for his corporate owners.