- How it works

Academic Assignment Samples and Examples

Are you looking for someone to write your academic assignment for you? This is the right place for you. To showcase the quality of the work that can be expected from ResearchProspect, we have curated a few samples of academic assignments. These examples have been developed by professional writers here. Place your order with us now.

Assignment Sample

Discipline: Sociology

Quality: Approved / Passed

Discipline: Construction

Quality: 1st / 78%

Discipline: Accounting & Finance

Quality: 2:1 / 69%

Undergraduate

Discipline: Bio-Medical

Quality: 1st / 76%

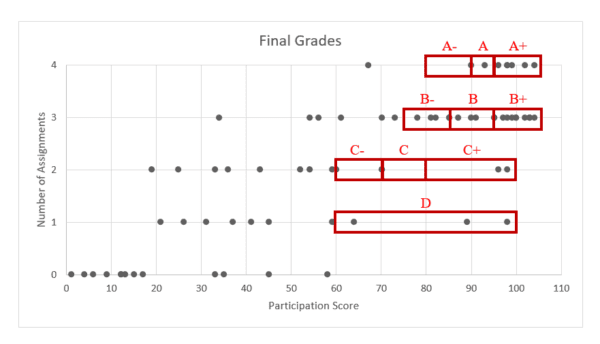

Discipline: Statistics

Quality: 1st / 73%

Discipline: Health and Safety

Quality: 2:1 / 68%

Discipline: Business

Quality: 2:1 / 67%

Discipline: Medicine

Quality: 2:1 / 66%

Discipline: Religion Theology

Quality: 2:1 / 64%

Discipline: Project Management

Quality: 2:1 / 63%

Discipline: Website Development

Discipline: Fire and Construction

Discipline: Environmental Management

Discipline: Early Child Education

Quality: 1st / 72%

Analysis of a Business Environment: Coffee and Cake Ltd (CC Ltd)

Business Strategy

Application of Project Management Using the Agile Approach ….

Project Management

Assessment of British Airways Social Media Posts

Critical annotation, global business environment (reflective report assignment), global marketing strategies, incoterms, ex (exw), free (fob, fca), cost (cpt, cip), delivery …., it systems strategy – the case of oxford university, management and organisation in global environment, marketing plan for “b airlines”, prepare a portfolio review and remedial options and actions …., systematic identification, analysis, and assessment of risk …., the exploratory problem-solving play and growth mindset for …..

Childhood Development

The Marketing Plan- UK Sustainable Energy Limited

Law assignment.

Law Case Study

To Analyse User’s Perception towards the Services Provided by Their…

Assignment Samples

Research Methodology

Discipline: Civil Engineering

Discipline: Health & Manangement

Our Assignment Writing Service Features

Subject specialists.

We have writers specialising in their respective fields to ensure rigorous quality control.

We are reliable as we deliver all your work to you and do not use it in any future work.

We ensure that our work is 100% plagiarism free and authentic and all references are cited.

Thoroughly Researched

We perform thorough research to get accurate content for you with proper citations.

Excellent Customer Service

To resolve your issues and queries, we provide 24/7 customer service

Our prices are kept at a level that is affordable for everyone to ensure maximum help.

Loved by over 100,000 students

Thousands of students have used ResearchProspect academic support services to improve their grades. Why are you waiting?

"I am glad I gave my order to ResearchProspect after seeing their academic assignment sample. Really happy with the results. "

Law Student

"I am grateful to them for doing my academic assignment. Got high grades."

Economics Student

Frequently Ask Questions?

How can these samples help you.

The assignment writing samples we provide help you by showing you versions of the finished item. It’s like having a picture of the cake you’re aiming to make when following a recipe.

Assignments that you undertake are a key part of your academic life; they are the usual way of assessing your knowledge on the subject you’re studying.

There are various types of assignments: essays, annotated bibliographies, stand-alone literature reviews, reflective writing essays, etc. There will be a specific structure to follow for each of these. Before focusing on the structure, it is best to plan your assignment first. Your school will have its own guidelines and instructions, you should align with those. Start by selecting the essential aspects that need to be included in your assignment.

Based on what you understand from the assignment in question, evaluate the critical points that should be made. If the task is research-based, discuss your aims and objectives, research method, and results. For an argumentative essay, you need to construct arguments relevant to the thesis statement.

Your assignment should be constructed according to the outline’s different sections. This is where you might find our samples so helpful; inspect them to understand how to write your assignment.

Adding headings to sections can enhance the clarity of your assignment. They are like signposts telling the reader what’s coming next.

Where structure is concerned, our samples can be of benefit. The basic structure is of three parts: introduction, discussion, and conclusion. It is, however, advisable to follow the structural guidelines from your tutor.

For example, our master’s sample assignment includes lots of headings and sub-headings. Undergraduate assignments are shorter and present a statistical analysis only.

If you are still unsure about how to approach your assignment, we are here to help, and we really can help you. You can start by just asking us a question with no need to commit. Our writers are able to assist by guiding you through every step of your assignment.

Who will write my assignment?

We have a cherry-picked writing team. They’ve been thoroughly tested and checked out to verify their skills and credentials. You can be sure our writers have proved they can write for you.

What if I have an urgent assignment? Do your delivery days include the weekends?

No problem. Christmas, Boxing Day, New Year’s Eve – our only days off. We know you want weekend delivery, so this is what we do.

Explore More Samples

View our professional samples to be certain that we have the portofilio and capabilities to deliver what you need.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Sample Papers

This page contains sample papers formatted in seventh edition APA Style. The sample papers show the format that authors should use to submit a manuscript for publication in a professional journal and that students should use to submit a paper to an instructor for a course assignment. You can download the Word files to use as templates and edit them as needed for the purposes of your own papers.

Most guidelines in the Publication Manual apply to both professional manuscripts and student papers. However, there are specific guidelines for professional papers versus student papers, including professional and student title page formats. All authors should check with the person or entity to whom they are submitting their paper (e.g., publisher or instructor) for guidelines that are different from or in addition to those specified by APA Style.

Sample papers from the Publication Manual

The following two sample papers were published in annotated form in the Publication Manual and are reproduced here as PDFs for your ease of use. The annotations draw attention to content and formatting and provide the relevant sections of the Publication Manual (7th ed.) to consult for more information.

- Student sample paper with annotations (PDF, 5MB)

- Professional sample paper with annotations (PDF, 2.7MB)

We also offer these sample papers in Microsoft Word (.docx) format with the annotations as comments to the text.

- Student sample paper with annotations as comments (DOCX, 42KB)

- Professional sample paper with annotations as comments (DOCX, 103KB)

Finally, we offer these sample papers in Microsoft Word (.docx) format without the annotations.

- Student sample paper without annotations (DOCX, 36KB)

- Professional sample paper without annotations (DOCX, 96KB)

Sample professional paper templates by paper type

These sample papers demonstrate APA Style formatting standards for different professional paper types. Professional papers can contain many different elements depending on the nature of the work. Authors seeking publication should refer to the journal’s instructions for authors or manuscript submission guidelines for specific requirements and/or sections to include.

- Literature review professional paper template (DOCX, 47KB)

- Mixed methods professional paper template (DOCX, 68KB)

- Qualitative professional paper template (DOCX, 72KB)

- Quantitative professional paper template (DOCX, 77KB)

- Review professional paper template (DOCX, 112KB)

Sample papers are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Chapter 2 and the Concise Guide Chapter 1

Related handouts

- Heading Levels Template: Student Paper (PDF, 257KB)

- Heading Levels Template: Professional Paper (PDF, 213KB)

Other instructional aids

- Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS)

- APA Style Tutorials and Webinars

- Handouts and Guides

- Paper Format

View all instructional aids

Sample student paper templates by paper type

These sample papers demonstrate APA Style formatting standards for different student paper types. Students may write the same types of papers as professional authors (e.g., quantitative studies, literature reviews) or other types of papers for course assignments (e.g., reaction or response papers, discussion posts), dissertations, and theses.

APA does not set formal requirements for the nature or contents of an APA Style student paper. Students should follow the guidelines and requirements of their instructor, department, and/or institution when writing papers. For instance, an abstract and keywords are not required for APA Style student papers, although an instructor may request them in student papers that are longer or more complex. Specific questions about a paper being written for a course assignment should be directed to the instructor or institution assigning the paper.

- Discussion post student paper template (DOCX, 31KB)

- Literature review student paper template (DOCX, 37KB)

- Quantitative study student paper template (DOCX, 53KB)

Sample papers in real life

Although published articles differ in format from manuscripts submitted for publication or student papers (e.g., different line spacing, font, margins, and column format), articles published in APA journals provide excellent demonstrations of APA Style in action.

APA journals began publishing papers in seventh edition APA Style in 2020. Professional authors should check the author submission guidelines for the journal to which they want to submit their paper for any journal-specific style requirements.

Credits for sample professional paper templates

Quantitative professional paper template: Adapted from “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines,” by B. Bago, D. G. Rand, and G. Pennycook, 2020, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 149 (8), pp. 1608–1613 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000729 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Qualitative professional paper template: Adapted from “‘My Smartphone Is an Extension of Myself’: A Holistic Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of Using a Smartphone,” by L. J. Harkin and D. Kuss, 2020, Psychology of Popular Media , 10 (1), pp. 28–38 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000278 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Mixed methods professional paper template: Adapted from “‘I Am a Change Agent’: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Students’ Social Justice Value Orientation in an Undergraduate Community Psychology Course,” by D. X. Henderson, A. T. Majors, and M. Wright, 2019, Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology , 7 (1), 68–80. ( https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000171 ). Copyright 2019 by the American Psychological Association.

Literature review professional paper template: Adapted from “Rethinking Emotions in the Context of Infants’ Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Interest and Positive Emotions,” by S. I. Hammond and J. K. Drummond, 2019, Developmental Psychology , 55 (9), pp. 1882–1888 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000685 ). Copyright 2019 by the American Psychological Association.

Review professional paper template: Adapted from “Joining the Conversation: Teaching Students to Think and Communicate Like Scholars,” by E. L. Parks, 2022, Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology , 8 (1), pp. 70–78 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000193 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Credits for sample student paper templates

These papers came from real students who gave their permission to have them edited and posted by APA.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Assignment is a task given to students by a teacher or professor, usually as a means of assessing their understanding and application of course material. Assignments can take various forms, including essays, research papers, presentations, problem sets, lab reports, and more.

Assignments are typically designed to be completed outside of class time and may require independent research, critical thinking, and analysis. They are often graded and used as a significant component of a student’s overall course grade. The instructions for an assignment usually specify the goals, requirements, and deadlines for completion, and students are expected to meet these criteria to earn a good grade.

History of Assignment

The use of assignments as a tool for teaching and learning has been a part of education for centuries. Following is a brief history of the Assignment.

- Ancient Times: Assignments such as writing exercises, recitations, and memorization tasks were used to reinforce learning.

- Medieval Period : Universities began to develop the concept of the assignment, with students completing essays, commentaries, and translations to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the subject matter.

- 19th Century : With the growth of schools and universities, assignments became more widespread and were used to assess student progress and achievement.

- 20th Century: The rise of distance education and online learning led to the further development of assignments as an integral part of the educational process.

- Present Day: Assignments continue to be used in a variety of educational settings and are seen as an effective way to promote student learning and assess student achievement. The nature and format of assignments continue to evolve in response to changing educational needs and technological innovations.

Types of Assignment

Here are some of the most common types of assignments:

An essay is a piece of writing that presents an argument, analysis, or interpretation of a topic or question. It usually consists of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Essay structure:

- Introduction : introduces the topic and thesis statement

- Body paragraphs : each paragraph presents a different argument or idea, with evidence and analysis to support it

- Conclusion : summarizes the key points and reiterates the thesis statement

Research paper

A research paper involves gathering and analyzing information on a particular topic, and presenting the findings in a well-structured, documented paper. It usually involves conducting original research, collecting data, and presenting it in a clear, organized manner.

Research paper structure:

- Title page : includes the title of the paper, author’s name, date, and institution

- Abstract : summarizes the paper’s main points and conclusions

- Introduction : provides background information on the topic and research question

- Literature review: summarizes previous research on the topic

- Methodology : explains how the research was conducted

- Results : presents the findings of the research

- Discussion : interprets the results and draws conclusions

- Conclusion : summarizes the key findings and implications

A case study involves analyzing a real-life situation, problem or issue, and presenting a solution or recommendations based on the analysis. It often involves extensive research, data analysis, and critical thinking.

Case study structure:

- Introduction : introduces the case study and its purpose

- Background : provides context and background information on the case

- Analysis : examines the key issues and problems in the case

- Solution/recommendations: proposes solutions or recommendations based on the analysis

- Conclusion: Summarize the key points and implications

A lab report is a scientific document that summarizes the results of a laboratory experiment or research project. It typically includes an introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

Lab report structure:

- Title page : includes the title of the experiment, author’s name, date, and institution

- Abstract : summarizes the purpose, methodology, and results of the experiment

- Methods : explains how the experiment was conducted

- Results : presents the findings of the experiment

Presentation

A presentation involves delivering information, data or findings to an audience, often with the use of visual aids such as slides, charts, or diagrams. It requires clear communication skills, good organization, and effective use of technology.

Presentation structure:

- Introduction : introduces the topic and purpose of the presentation

- Body : presents the main points, findings, or data, with the help of visual aids

- Conclusion : summarizes the key points and provides a closing statement

Creative Project

A creative project is an assignment that requires students to produce something original, such as a painting, sculpture, video, or creative writing piece. It allows students to demonstrate their creativity and artistic skills.

Creative project structure:

- Introduction : introduces the project and its purpose

- Body : presents the creative work, with explanations or descriptions as needed

- Conclusion : summarizes the key elements and reflects on the creative process.

Examples of Assignments

Following are Examples of Assignment templates samples:

Essay template:

I. Introduction

- Hook: Grab the reader’s attention with a catchy opening sentence.

- Background: Provide some context or background information on the topic.

- Thesis statement: State the main argument or point of your essay.

II. Body paragraphs

- Topic sentence: Introduce the main idea or argument of the paragraph.

- Evidence: Provide evidence or examples to support your point.

- Analysis: Explain how the evidence supports your argument.

- Transition: Use a transition sentence to lead into the next paragraph.

III. Conclusion

- Restate thesis: Summarize your main argument or point.

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your essay.

- Concluding thoughts: End with a final thought or call to action.

Research paper template:

I. Title page

- Title: Give your paper a descriptive title.

- Author: Include your name and institutional affiliation.

- Date: Provide the date the paper was submitted.

II. Abstract

- Background: Summarize the background and purpose of your research.

- Methodology: Describe the methods you used to conduct your research.

- Results: Summarize the main findings of your research.

- Conclusion: Provide a brief summary of the implications and conclusions of your research.

III. Introduction

- Background: Provide some background information on the topic.

- Research question: State your research question or hypothesis.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of your research.

IV. Literature review

- Background: Summarize previous research on the topic.

- Gaps in research: Identify gaps or areas that need further research.

V. Methodology

- Participants: Describe the participants in your study.

- Procedure: Explain the procedure you used to conduct your research.

- Measures: Describe the measures you used to collect data.

VI. Results

- Quantitative results: Summarize the quantitative data you collected.

- Qualitative results: Summarize the qualitative data you collected.

VII. Discussion

- Interpretation: Interpret the results and explain what they mean.

- Implications: Discuss the implications of your research.

- Limitations: Identify any limitations or weaknesses of your research.

VIII. Conclusion

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your paper.

Case study template:

- Background: Provide background information on the case.

- Research question: State the research question or problem you are examining.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of the case study.

II. Analysis

- Problem: Identify the main problem or issue in the case.

- Factors: Describe the factors that contributed to the problem.

- Alternative solutions: Describe potential solutions to the problem.

III. Solution/recommendations

- Proposed solution: Describe the solution you are proposing.

- Rationale: Explain why this solution is the best one.

- Implementation: Describe how the solution can be implemented.

IV. Conclusion

- Summary: Summarize the main points of your case study.

Lab report template:

- Title: Give your report a descriptive title.

- Date: Provide the date the report was submitted.

- Background: Summarize the background and purpose of the experiment.

- Methodology: Describe the methods you used to conduct the experiment.

- Results: Summarize the main findings of the experiment.

- Conclusion: Provide a brief summary of the implications and conclusions

- Background: Provide some background information on the experiment.

- Hypothesis: State your hypothesis or research question.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of the experiment.

IV. Materials and methods

- Materials: List the materials and equipment used in the experiment.

- Procedure: Describe the procedure you followed to conduct the experiment.

- Data: Present the data you collected in tables or graphs.

- Analysis: Analyze the data and describe the patterns or trends you observed.

VI. Discussion

- Implications: Discuss the implications of your findings.

- Limitations: Identify any limitations or weaknesses of the experiment.

VII. Conclusion

- Restate hypothesis: Summarize your hypothesis or research question.

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your report.

Presentation template:

- Attention grabber: Grab the audience’s attention with a catchy opening.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of your presentation.

- Overview: Provide an overview of what you will cover in your presentation.

II. Main points

- Main point 1: Present the first main point of your presentation.

- Supporting details: Provide supporting details or evidence to support your point.

- Main point 2: Present the second main point of your presentation.

- Main point 3: Present the third main point of your presentation.

- Summary: Summarize the main points of your presentation.

- Call to action: End with a final thought or call to action.

Creative writing template:

- Setting: Describe the setting of your story.

- Characters: Introduce the main characters of your story.

- Rising action: Introduce the conflict or problem in your story.

- Climax: Present the most intense moment of the story.

- Falling action: Resolve the conflict or problem in your story.

- Resolution: Describe how the conflict or problem was resolved.

- Final thoughts: End with a final thought or reflection on the story.

How to Write Assignment

Here is a general guide on how to write an assignment:

- Understand the assignment prompt: Before you begin writing, make sure you understand what the assignment requires. Read the prompt carefully and make note of any specific requirements or guidelines.

- Research and gather information: Depending on the type of assignment, you may need to do research to gather information to support your argument or points. Use credible sources such as academic journals, books, and reputable websites.

- Organize your ideas : Once you have gathered all the necessary information, organize your ideas into a clear and logical structure. Consider creating an outline or diagram to help you visualize your ideas.

- Write a draft: Begin writing your assignment using your organized ideas and research. Don’t worry too much about grammar or sentence structure at this point; the goal is to get your thoughts down on paper.

- Revise and edit: After you have written a draft, revise and edit your work. Make sure your ideas are presented in a clear and concise manner, and that your sentences and paragraphs flow smoothly.

- Proofread: Finally, proofread your work for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors. It’s a good idea to have someone else read over your assignment as well to catch any mistakes you may have missed.

- Submit your assignment : Once you are satisfied with your work, submit your assignment according to the instructions provided by your instructor or professor.

Applications of Assignment

Assignments have many applications across different fields and industries. Here are a few examples:

- Education : Assignments are a common tool used in education to help students learn and demonstrate their knowledge. They can be used to assess a student’s understanding of a particular topic, to develop critical thinking skills, and to improve writing and research abilities.

- Business : Assignments can be used in the business world to assess employee skills, to evaluate job performance, and to provide training opportunities. They can also be used to develop business plans, marketing strategies, and financial projections.

- Journalism : Assignments are often used in journalism to produce news articles, features, and investigative reports. Journalists may be assigned to cover a particular event or topic, or to research and write a story on a specific subject.

- Research : Assignments can be used in research to collect and analyze data, to conduct experiments, and to present findings in written or oral form. Researchers may be assigned to conduct research on a specific topic, to write a research paper, or to present their findings at a conference or seminar.

- Government : Assignments can be used in government to develop policy proposals, to conduct research, and to analyze data. Government officials may be assigned to work on a specific project or to conduct research on a particular topic.

- Non-profit organizations: Assignments can be used in non-profit organizations to develop fundraising strategies, to plan events, and to conduct research. Volunteers may be assigned to work on a specific project or to help with a particular task.

Purpose of Assignment

The purpose of an assignment varies depending on the context in which it is given. However, some common purposes of assignments include:

- Assessing learning: Assignments are often used to assess a student’s understanding of a particular topic or concept. This allows educators to determine if a student has mastered the material or if they need additional support.

- Developing skills: Assignments can be used to develop a wide range of skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, research, and communication. Assignments that require students to analyze and synthesize information can help to build these skills.

- Encouraging creativity: Assignments can be designed to encourage students to be creative and think outside the box. This can help to foster innovation and original thinking.

- Providing feedback : Assignments provide an opportunity for teachers to provide feedback to students on their progress and performance. Feedback can help students to understand where they need to improve and to develop a growth mindset.

- Meeting learning objectives : Assignments can be designed to help students meet specific learning objectives or outcomes. For example, a writing assignment may be designed to help students improve their writing skills, while a research assignment may be designed to help students develop their research skills.

When to write Assignment

Assignments are typically given by instructors or professors as part of a course or academic program. The timing of when to write an assignment will depend on the specific requirements of the course or program, but in general, assignments should be completed within the timeframe specified by the instructor or program guidelines.

It is important to begin working on assignments as soon as possible to ensure enough time for research, writing, and revisions. Waiting until the last minute can result in rushed work and lower quality output.

It is also important to prioritize assignments based on their due dates and the amount of work required. This will help to manage time effectively and ensure that all assignments are completed on time.

In addition to assignments given by instructors or professors, there may be other situations where writing an assignment is necessary. For example, in the workplace, assignments may be given to complete a specific project or task. In these situations, it is important to establish clear deadlines and expectations to ensure that the assignment is completed on time and to a high standard.

Characteristics of Assignment

Here are some common characteristics of assignments:

- Purpose : Assignments have a specific purpose, such as assessing knowledge or developing skills. They are designed to help students learn and achieve specific learning objectives.

- Requirements: Assignments have specific requirements that must be met, such as a word count, format, or specific content. These requirements are usually provided by the instructor or professor.

- Deadline: Assignments have a specific deadline for completion, which is usually set by the instructor or professor. It is important to meet the deadline to avoid penalties or lower grades.

- Individual or group work: Assignments can be completed individually or as part of a group. Group assignments may require collaboration and communication with other group members.

- Feedback : Assignments provide an opportunity for feedback from the instructor or professor. This feedback can help students to identify areas of improvement and to develop their skills.

- Academic integrity: Assignments require academic integrity, which means that students must submit original work and avoid plagiarism. This includes citing sources properly and following ethical guidelines.

- Learning outcomes : Assignments are designed to help students achieve specific learning outcomes. These outcomes are usually related to the course objectives and may include developing critical thinking skills, writing abilities, or subject-specific knowledge.

Advantages of Assignment

There are several advantages of assignment, including:

- Helps in learning: Assignments help students to reinforce their learning and understanding of a particular topic. By completing assignments, students get to apply the concepts learned in class, which helps them to better understand and retain the information.

- Develops critical thinking skills: Assignments often require students to think critically and analyze information in order to come up with a solution or answer. This helps to develop their critical thinking skills, which are important for success in many areas of life.

- Encourages creativity: Assignments that require students to create something, such as a piece of writing or a project, can encourage creativity and innovation. This can help students to develop new ideas and perspectives, which can be beneficial in many areas of life.

- Builds time-management skills: Assignments often come with deadlines, which can help students to develop time-management skills. Learning how to manage time effectively is an important skill that can help students to succeed in many areas of life.

- Provides feedback: Assignments provide an opportunity for students to receive feedback on their work. This feedback can help students to identify areas where they need to improve and can help them to grow and develop.

Limitations of Assignment

There are also some limitations of assignments that should be considered, including:

- Limited scope: Assignments are often limited in scope, and may not provide a comprehensive understanding of a particular topic. They may only cover a specific aspect of a topic, and may not provide a full picture of the subject matter.

- Lack of engagement: Some assignments may not engage students in the learning process, particularly if they are repetitive or not challenging enough. This can lead to a lack of motivation and interest in the subject matter.

- Time-consuming: Assignments can be time-consuming, particularly if they require a lot of research or writing. This can be a disadvantage for students who have other commitments, such as work or extracurricular activities.

- Unreliable assessment: The assessment of assignments can be subjective and may not always accurately reflect a student’s understanding or abilities. The grading may be influenced by factors such as the instructor’s personal biases or the student’s writing style.

- Lack of feedback : Although assignments can provide feedback, this feedback may not always be detailed or useful. Instructors may not have the time or resources to provide detailed feedback on every assignment, which can limit the value of the feedback that students receive.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

References in Research – Types, Examples and...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to...

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

The Beginner's Guide to Writing an Essay | Steps & Examples

An academic essay is a focused piece of writing that develops an idea or argument using evidence, analysis, and interpretation.

There are many types of essays you might write as a student. The content and length of an essay depends on your level, subject of study, and course requirements. However, most essays at university level are argumentative — they aim to persuade the reader of a particular position or perspective on a topic.

The essay writing process consists of three main stages:

- Preparation: Decide on your topic, do your research, and create an essay outline.

- Writing : Set out your argument in the introduction, develop it with evidence in the main body, and wrap it up with a conclusion.

- Revision: Check your essay on the content, organization, grammar, spelling, and formatting of your essay.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Essay writing process, preparation for writing an essay, writing the introduction, writing the main body, writing the conclusion, essay checklist, lecture slides, frequently asked questions about writing an essay.

The writing process of preparation, writing, and revisions applies to every essay or paper, but the time and effort spent on each stage depends on the type of essay .

For example, if you’ve been assigned a five-paragraph expository essay for a high school class, you’ll probably spend the most time on the writing stage; for a college-level argumentative essay , on the other hand, you’ll need to spend more time researching your topic and developing an original argument before you start writing.

| 1. Preparation | 2. Writing | 3. Revision |

|---|---|---|

| , organized into Write the | or use a for language errors |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Before you start writing, you should make sure you have a clear idea of what you want to say and how you’re going to say it. There are a few key steps you can follow to make sure you’re prepared:

- Understand your assignment: What is the goal of this essay? What is the length and deadline of the assignment? Is there anything you need to clarify with your teacher or professor?

- Define a topic: If you’re allowed to choose your own topic , try to pick something that you already know a bit about and that will hold your interest.

- Do your research: Read primary and secondary sources and take notes to help you work out your position and angle on the topic. You’ll use these as evidence for your points.

- Come up with a thesis: The thesis is the central point or argument that you want to make. A clear thesis is essential for a focused essay—you should keep referring back to it as you write.

- Create an outline: Map out the rough structure of your essay in an outline . This makes it easier to start writing and keeps you on track as you go.

Once you’ve got a clear idea of what you want to discuss, in what order, and what evidence you’ll use, you’re ready to start writing.

The introduction sets the tone for your essay. It should grab the reader’s interest and inform them of what to expect. The introduction generally comprises 10–20% of the text.

1. Hook your reader

The first sentence of the introduction should pique your reader’s interest and curiosity. This sentence is sometimes called the hook. It might be an intriguing question, a surprising fact, or a bold statement emphasizing the relevance of the topic.

Let’s say we’re writing an essay about the development of Braille (the raised-dot reading and writing system used by visually impaired people). Our hook can make a strong statement about the topic:

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

2. Provide background on your topic

Next, it’s important to give context that will help your reader understand your argument. This might involve providing background information, giving an overview of important academic work or debates on the topic, and explaining difficult terms. Don’t provide too much detail in the introduction—you can elaborate in the body of your essay.

3. Present the thesis statement

Next, you should formulate your thesis statement— the central argument you’re going to make. The thesis statement provides focus and signals your position on the topic. It is usually one or two sentences long. The thesis statement for our essay on Braille could look like this:

As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness.

4. Map the structure

In longer essays, you can end the introduction by briefly describing what will be covered in each part of the essay. This guides the reader through your structure and gives a preview of how your argument will develop.

The invention of Braille marked a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by blind and visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Write your essay introduction

The body of your essay is where you make arguments supporting your thesis, provide evidence, and develop your ideas. Its purpose is to present, interpret, and analyze the information and sources you have gathered to support your argument.

Length of the body text

The length of the body depends on the type of essay. On average, the body comprises 60–80% of your essay. For a high school essay, this could be just three paragraphs, but for a graduate school essay of 6,000 words, the body could take up 8–10 pages.

Paragraph structure

To give your essay a clear structure , it is important to organize it into paragraphs . Each paragraph should be centered around one main point or idea.

That idea is introduced in a topic sentence . The topic sentence should generally lead on from the previous paragraph and introduce the point to be made in this paragraph. Transition words can be used to create clear connections between sentences.

After the topic sentence, present evidence such as data, examples, or quotes from relevant sources. Be sure to interpret and explain the evidence, and show how it helps develop your overall argument.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

See the full essay example

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion is the final paragraph of an essay. It should generally take up no more than 10–15% of the text . A strong essay conclusion :

- Returns to your thesis

- Ties together your main points

- Shows why your argument matters

A great conclusion should finish with a memorable or impactful sentence that leaves the reader with a strong final impression.

What not to include in a conclusion

To make your essay’s conclusion as strong as possible, there are a few things you should avoid. The most common mistakes are:

- Including new arguments or evidence

- Undermining your arguments (e.g. “This is just one approach of many”)

- Using concluding phrases like “To sum up…” or “In conclusion…”

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Write your essay conclusion

Checklist: Essay

My essay follows the requirements of the assignment (topic and length ).

My introduction sparks the reader’s interest and provides any necessary background information on the topic.

My introduction contains a thesis statement that states the focus and position of the essay.

I use paragraphs to structure the essay.

I use topic sentences to introduce each paragraph.

Each paragraph has a single focus and a clear connection to the thesis statement.

I make clear transitions between paragraphs and ideas.

My conclusion doesn’t just repeat my points, but draws connections between arguments.

I don’t introduce new arguments or evidence in the conclusion.

I have given an in-text citation for every quote or piece of information I got from another source.

I have included a reference page at the end of my essay, listing full details of all my sources.

My citations and references are correctly formatted according to the required citation style .

My essay has an interesting and informative title.

I have followed all formatting guidelines (e.g. font, page numbers, line spacing).

Your essay meets all the most important requirements. Our editors can give it a final check to help you submit with confidence.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- How long is an essay? Guidelines for different types of essay

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

- How to conclude an essay | Interactive example

More interesting articles

- Checklist for academic essays | Is your essay ready to submit?

- Comparing and contrasting in an essay | Tips & examples

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

- Generate topic ideas for an essay or paper | Tips & techniques

- How to revise an essay in 3 simple steps

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

- How to write a descriptive essay | Example & tips

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

- How to write an essay outline | Guidelines & examples

- How to write an expository essay

- How to write the body of an essay | Drafting & redrafting

- Kinds of argumentative academic essays and their purposes

- Organizational tips for academic essays

- The four main types of essay | Quick guide with examples

- Transition sentences | Tips & examples for clear writing

Get unlimited documents corrected

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How to Write a Perfect Assignment: Step-By-Step Guide

Table of contents

- 1 How to Structure an Assignment?

- 2.1 The research part

- 2.2 Planning your text

- 2.3 Writing major parts

- 3 Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

- 4 Will I succeed with my assignments?

- 5 Conclusion

How to Structure an Assignment?

To cope with assignments, you should familiarize yourself with the tips on formatting and presenting assignments or any written paper, which are given below. It is worth paying attention to the content of the paper, making it structured and understandable so that ideas are not lost and thoughts do not refute each other.

If the topic is free or you can choose from the given list — be sure to choose the one you understand best. Especially if that could affect your semester score or scholarship. It is important to select an engaging title that is contextualized within your topic. A topic that should captivate you or at least give you a general sense of what is needed there. It’s easier to dwell upon what interests you, so the process goes faster.

To construct an assignment structure, use outlines. These are pieces of text that relate to your topic. It can be ideas, quotes, all your thoughts, or disparate arguments. Type in everything that you think about. Separate thoughts scattered across the sheets of Word will help in the next step.

Then it is time to form the text. At this stage, you have to form a coherent story from separate pieces, where each new thought reinforces the previous one, and one idea smoothly flows into another.

Main Steps of Assignment Writing

These are steps to take to get a worthy paper. If you complete these step-by-step, your text will be among the most exemplary ones.

The research part

If the topic is unique and no one has written about it yet, look at materials close to this topic to gain thoughts about it. You should feel that you are ready to express your thoughts. Also, while reading, get acquainted with the format of the articles, study the details, collect material for your thoughts, and accumulate different points of view for your article. Be careful at this stage, as the process can help you develop your ideas. If you are already struggling here, pay for assignment to be done , and it will be processed in a split second via special services. These services are especially helpful when the deadline is near as they guarantee fast delivery of high-quality papers on any subject.

If you use Google to search for material for your assignment, you will, of course, find a lot of information very quickly. Still, the databases available on your library’s website will give you the clearest and most reliable facts that satisfy your teacher or professor. Be sure you copy the addresses of all the web pages you will use when composing your paper, so you don’t lose them. You can use them later in your bibliography if you add a bit of description! Select resources and extract quotes from them that you can use while working. At this stage, you may also create a request for late assignment if you realize the paper requires a lot of effort and is time-consuming. This way, you’ll have a backup plan if something goes wrong.

Planning your text

Assemble a layout. It may be appropriate to use the structure of the paper of some outstanding scientists in your field and argue it in one of the parts. As the planning progresses, you can add suggestions that come to mind. If you use citations that require footnotes, and if you use single spacing throughout the paper and double spacing at the end, it will take you a very long time to make sure that all the citations are on the exact pages you specified! Add a reference list or bibliography. If you haven’t already done so, don’t put off writing an essay until the last day. It will be more difficult to do later as you will be stressed out because of time pressure.

Writing major parts

It happens that there is simply no mood or strength to get started and zero thoughts. In that case, postpone this process for 2-3 hours, and, perhaps, soon, you will be able to start with renewed vigor. Writing essays is a great (albeit controversial) way to improve your skills. This experience will not be forgotten. It will certainly come in handy and bring many benefits in the future. Do your best here because asking for an extension is not always possible, so you probably won’t have time to redo it later. And the quality of this part defines the success of the whole paper.

Writing the major part does not mean the matter is finished. To review the text, make sure that the ideas of the introduction and conclusion coincide because such a discrepancy is the first thing that will catch the reader’s eye and can spoil the impression. Add or remove anything from your intro to edit it to fit the entire paper. Also, check your spelling and grammar to ensure there are no typos or draft comments. Check the sources of your quotes so that your it is honest and does not violate any rules. And do not forget the formatting rules.

with the right tips and guidance, it can be easier than it looks. To make the process even more straightforward, students can also use an assignment service to get the job done. This way they can get professional assistance and make sure that their assignments are up to the mark. At PapersOwl, we provide a professional writing service where students can order custom-made assignments that meet their exact requirements.

Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

Want to write like a pro? Here’s what you should consider:

- Save the document! Send the finished document by email to yourself so you have a backup copy in case your computer crashes.

- Don’t wait until the last minute to complete a list of citations or a bibliography after the paper is finished. It will be much longer and more difficult, so add to them as you go.

- If you find a lot of information on the topic of your search, then arrange it in a separate paragraph.

- If possible, choose a topic that you know and are interested in.

- Believe in yourself! If you set yourself up well and use your limited time wisely, you will be able to deliver the paper on time.

- Do not copy information directly from the Internet without citing them.

Writing assignments is a tedious and time-consuming process. It requires a lot of research and hard work to produce a quality paper. However, if you are feeling overwhelmed or having difficulty understanding the concept, you may want to consider getting accounting homework help online . Professional experts can assist you in understanding how to complete your assignment effectively. PapersOwl.com offers expert help from highly qualified and experienced writers who can provide you with the homework help you need.

Will I succeed with my assignments?

Anyone can learn how to be good at writing: follow simple rules of creating the structure and be creative where it is appropriate. At one moment, you will need some additional study tools, study support, or solid study tips. And you can easily get help in writing assignments or any other work. This is especially useful since the strategy of learning how to write an assignment can take more time than a student has.

Therefore all students are happy that there is an option to order your paper at a professional service to pass all the courses perfectly and sleep still at night. You can also find the sample of the assignment there to check if you are on the same page and if not — focus on your papers more diligently.

So, in the times of studies online, the desire and skill to research and write may be lost. Planning your assignment carefully and presenting arguments step-by-step is necessary to succeed with your homework. When going through your references, note the questions that appear and answer them, building your text. Create a cover page, proofread the whole text, and take care of formatting. Feel free to use these rules for passing your next assignments.

When it comes to writing an assignment, it can be overwhelming and stressful, but Papersowl is here to make it easier for you. With a range of helpful resources available, Papersowl can assist you in creating high-quality written work, regardless of whether you’re starting from scratch or refining an existing draft. From conducting research to creating an outline, and from proofreading to formatting, the team at Papersowl has the expertise to guide you through the entire writing process and ensure that your assignment meets all the necessary requirements.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Essay samples for every taste and need

Find the perfect essay sample that you can reference for educational purposes. Need a unique one?

Choose samples by essay type

The font type, compare and contrast, how to craft a good essay writing sample.