How-To Geek

How to work with variables in bash.

Want to take your Linux command-line skills to the next level? Here's everything you need to know to start working with variables.

Hannah Stryker / How-To Geek

Quick Links

Variables 101, examples of bash variables, how to use bash variables in scripts, how to use command line parameters in scripts, working with special variables, environment variables, how to export variables, how to quote variables, echo is your friend, key takeaways.

- Variables are named symbols representing strings or numeric values. They are treated as their value when used in commands and expressions.

- Variable names should be descriptive and cannot start with a number or contain spaces. They can start with an underscore and can have alphanumeric characters.

- Variables can be used to store and reference values. The value of a variable can be changed, and it can be referenced by using the dollar sign $ before the variable name.

Variables are vital if you want to write scripts and understand what that code you're about to cut and paste from the web will do to your Linux computer. We'll get you started!

Variables are named symbols that represent either a string or numeric value. When you use them in commands and expressions, they are treated as if you had typed the value they hold instead of the name of the variable.

To create a variable, you just provide a name and value for it. Your variable names should be descriptive and remind you of the value they hold. A variable name cannot start with a number, nor can it contain spaces. It can, however, start with an underscore. Apart from that, you can use any mix of upper- and lowercase alphanumeric characters.

Here, we'll create five variables. The format is to type the name, the equals sign = , and the value. Note there isn't a space before or after the equals sign. Giving a variable a value is often referred to as assigning a value to the variable.

We'll create four string variables and one numeric variable,

my_name=Dave

my_boost=Linux

his_boost=Spinach

this_year=2019

To see the value held in a variable, use the echo command. You must precede the variable name with a dollar sign $ whenever you reference the value it contains, as shown below:

echo $my_name

echo $my_boost

echo $this_year

Let's use all of our variables at once:

echo "$my_boost is to $me as $his_boost is to $him (c) $this_year"

The values of the variables replace their names. You can also change the values of variables. To assign a new value to the variable, my_boost , you just repeat what you did when you assigned its first value, like so:

my_boost=Tequila

If you re-run the previous command, you now get a different result:

So, you can use the same command that references the same variables and get different results if you change the values held in the variables.

We'll talk about quoting variables later. For now, here are some things to remember:

- A variable in single quotes ' is treated as a literal string, and not as a variable.

- Variables in quotation marks " are treated as variables.

- To get the value held in a variable, you have to provide the dollar sign $ .

- A variable without the dollar sign $ only provides the name of the variable.

You can also create a variable that takes its value from an existing variable or number of variables. The following command defines a new variable called drink_of_the_Year, and assigns it the combined values of the my_boost and this_year variables:

drink_of-the_Year="$my_boost $this_year"

echo drink_of_the-Year

Scripts would be completely hamstrung without variables. Variables provide the flexibility that makes a script a general, rather than a specific, solution. To illustrate the difference, here's a script that counts the files in the /dev directory.

Type this into a text file, and then save it as fcnt.sh (for "file count"):

#!/bin/bashfolder_to_count=/devfile_count=$(ls $folder_to_count | wc -l)echo $file_count files in $folder_to_count

Before you can run the script, you have to make it executable, as shown below:

chmod +x fcnt.sh

Type the following to run the script:

This prints the number of files in the /dev directory. Here's how it works:

- A variable called folder_to_count is defined, and it's set to hold the string "/dev."

- Another variable, called file_count , is defined. This variable takes its value from a command substitution. This is the command phrase between the parentheses $( ) . Note there's a dollar sign $ before the first parenthesis. This construct $( ) evaluates the commands within the parentheses, and then returns their final value. In this example, that value is assigned to the file_count variable. As far as the file_count variable is concerned, it's passed a value to hold; it isn't concerned with how the value was obtained.

- The command evaluated in the command substitution performs an ls file listing on the directory in the folder_to_count variable, which has been set to "/dev." So, the script executes the command "ls /dev."

- The output from this command is piped into the wc command. The -l (line count) option causes wc to count the number of lines in the output from the ls command. As each file is listed on a separate line, this is the count of files and subdirectories in the "/dev" directory. This value is assigned to the file_count variable.

- The final line uses echo to output the result.

But this only works for the "/dev" directory. How can we make the script work with any directory? All it takes is one small change.

Many commands, such as ls and wc , take command line parameters. These provide information to the command, so it knows what you want it to do. If you want ls to work on your home directory and also to show hidden files , you can use the following command, where the tilde ~ and the -a (all) option are command line parameters:

Our scripts can accept command line parameters. They're referenced as $1 for the first parameter, $2 as the second, and so on, up to $9 for the ninth parameter. (Actually, there's a $0 , as well, but that's reserved to always hold the script.)

You can reference command line parameters in a script just as you would regular variables. Let's modify our script, as shown below, and save it with the new name fcnt2.sh :

#!/bin/bashfolder_to_count=$1file_count=$(ls $folder_to_count | wc -l)echo $file_count files in $folder_to_count

This time, the folder_to_count variable is assigned the value of the first command line parameter, $1 .

The rest of the script works exactly as it did before. Rather than a specific solution, your script is now a general one. You can use it on any directory because it's not hardcoded to work only with "/dev."

Here's how you make the script executable:

chmod +x fcnt2.sh

Now, try it with a few directories. You can do "/dev" first to make sure you get the same result as before. Type the following:

./fnct2.sh /dev

./fnct2.sh /etc

./fnct2.sh /bin

You get the same result (207 files) as before for the "/dev" directory. This is encouraging, and you get directory-specific results for each of the other command line parameters.

To shorten the script, you could dispense with the variable, folder_to_count , altogether, and just reference $1 throughout, as follows:

#!/bin/bash file_count=$(ls $1 wc -l) echo $file_count files in $1

We mentioned $0 , which is always set to the filename of the script. This allows you to use the script to do things like print its name out correctly, even if it's renamed. This is useful in logging situations, in which you want to know the name of the process that added an entry.

The following are the other special preset variables:

- $# : How many command line parameters were passed to the script.

- $@ : All the command line parameters passed to the script.

- $? : The exit status of the last process to run.

- $$ : The Process ID (PID) of the current script.

- $USER : The username of the user executing the script.

- $HOSTNAME : The hostname of the computer running the script.

- $SECONDS : The number of seconds the script has been running for.

- $RANDOM : Returns a random number.

- $LINENO : Returns the current line number of the script.

You want to see all of them in one script, don't you? You can! Save the following as a text file called, special.sh :

#!/bin/bashecho "There were $# command line parameters"echo "They are: $@"echo "Parameter 1 is: $1"echo "The script is called: $0"# any old process so that we can report on the exit statuspwdecho "pwd returned $?"echo "This script has Process ID $$"echo "The script was started by $USER"echo "It is running on $HOSTNAME"sleep 3echo "It has been running for $SECONDS seconds"echo "Random number: $RANDOM"echo "This is line number $LINENO of the script"

Type the following to make it executable:

chmod +x special.sh

Now, you can run it with a bunch of different command line parameters, as shown below.

Bash uses environment variables to define and record the properties of the environment it creates when it launches. These hold information Bash can readily access, such as your username, locale, the number of commands your history file can hold, your default editor, and lots more.

To see the active environment variables in your Bash session, use this command:

If you scroll through the list, you might find some that would be useful to reference in your scripts.

When a script runs, it's in its own process, and the variables it uses cannot be seen outside of that process. If you want to share a variable with another script that your script launches, you have to export that variable. We'll show you how to this with two scripts.

First, save the following with the filename script_one.sh :

#!/bin/bashfirst_var=alphasecond_var=bravo# check their valuesecho "$0: first_var=$first_var, second_var=$second_var"export first_varexport second_var./script_two.sh# check their values againecho "$0: first_var=$first_var, second_var=$second_var"

This creates two variables, first_var and second_var , and it assigns some values. It prints these to the terminal window, exports the variables, and calls script_two.sh . When script_two.sh terminates, and process flow returns to this script, it again prints the variables to the terminal window. Then, you can see if they changed.

The second script we'll use is script_two.sh . This is the script that script_one.sh calls. Type the following:

#!/bin/bash# check their valuesecho "$0: first_var=$first_var, second_var=$second_var"# set new valuesfirst_var=charliesecond_var=delta# check their values againecho "$0: first_var=$first_var, second_var=$second_var"

This second script prints the values of the two variables, assigns new values to them, and then prints them again.

To run these scripts, you have to type the following to make them executable:

chmod +x script_one.shchmod +x script_two.sh

And now, type the following to launch script_one.sh :

./script_one.sh

This is what the output tells us:

- script_one.sh prints the values of the variables, which are alpha and bravo.

- script_two.sh prints the values of the variables (alpha and bravo) as it received them.

- script_two.sh changes them to charlie and delta.

- script_one.sh prints the values of the variables, which are still alpha and bravo.

What happens in the second script, stays in the second script. It's like copies of the variables are sent to the second script, but they're discarded when that script exits. The original variables in the first script aren't altered by anything that happens to the copies of them in the second.

You might have noticed that when scripts reference variables, they're in quotation marks " . This allows variables to be referenced correctly, so their values are used when the line is executed in the script.

If the value you assign to a variable includes spaces, they must be in quotation marks when you assign them to the variable. This is because, by default, Bash uses a space as a delimiter.

Here's an example:

site_name=How-To Geek

Bash sees the space before "Geek" as an indication that a new command is starting. It reports that there is no such command, and abandons the line. echo shows us that the site_name variable holds nothing — not even the "How-To" text.

Try that again with quotation marks around the value, as shown below:

site_name="How-To Geek"

This time, it's recognized as a single value and assigned correctly to the site_name variable.

It can take some time to get used to command substitution, quoting variables, and remembering when to include the dollar sign.

Before you hit Enter and execute a line of Bash commands, try it with echo in front of it. This way, you can make sure what's going to happen is what you want. You can also catch any mistakes you might have made in the syntax.

Home > Bash Scripting Tutorial > Bash Variables > Variable Declaration and Assignment > How to Assign Variable in Bash Script? [8 Practical Cases]

How to Assign Variable in Bash Script? [8 Practical Cases]

Variables allow you to store and manipulate data within your script, making it easier to organize and access information. In Bash scripts , variable assignment follows a straightforward syntax, but it offers a range of options and features that can enhance the flexibility and functionality of your scripts. In this article, I will discuss modes to assign variable in the Bash script . As the Bash script offers a range of methods for assigning variables, I will thoroughly delve into each one.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Getting Familiar With Different Types Of Variables.

- Learning how to assign single or multiple bash variables.

- Understanding the arithmetic operation in Bash Scripting.

Free Downloads

Local vs global variable assignment.

In programming, variables are used to store and manipulate data. There are two main types of variable assignments: local and global .

A. Local Variable Assignment

In programming, a local variable assignment refers to the process of declaring and assigning a variable within a specific scope, such as a function or a block of code. Local variables are temporary and have limited visibility, meaning they can only be accessed within the scope in which they are defined.

Here are some key characteristics of local variable assignment:

- Local variables in bash are created within a function or a block of code.

- By default, variables declared within a function are local to that function.

- They are not accessible outside the function or block in which they are defined.

- Local variables typically store temporary or intermediate values within a specific context.

Here is an example in Bash script.

In this example, the variable x is a local variable within the scope of the my_function function. It can be accessed and used within the function, but accessing it outside the function will result in an error because the variable is not defined in the outer scope.

B. Global Variable Assignment

In Bash scripting, global variables are accessible throughout the entire script, regardless of the scope in which they are declared. Global variables can be accessed and modified from any script part, including within functions.

Here are some key characteristics of global variable assignment:

- Global variables in bash are declared outside of any function or block.

- They are accessible throughout the entire script.

- Any variable declared outside of a function or block is considered global by default.

- Global variables can be accessed and modified from any script part, including within functions.

Here is an example in Bash script given in the context of a global variable .

It’s important to note that in bash, variable assignment without the local keyword within a function will create a global variable even if there is a global variable with the same name. To ensure local scope within a function , using the local keyword explicitly is recommended.

Additionally, it’s worth mentioning that subprocesses spawned by a bash script, such as commands executed with $(…) or backticks , create their own separate environments, and variables assigned within those subprocesses are not accessible in the parent script .

8 Different Cases to Assign Variables in Bash Script

In Bash scripting , there are various cases or scenarios in which you may need to assign variables. Here are some common cases I have described below. These examples cover various scenarios, such as assigning single variables , multiple variable assignments in a single line , extracting values from command-line arguments , obtaining input from the user , utilizing environmental variables, etc . So let’s start.

Case 01: Single Variable Assignment

To assign a value to a single variable in Bash script , you can use the following syntax:

However, replace the variable with the name of the variable you want to assign, and the value with the desired value you want to assign to that variable.

To assign a single value to a variable in Bash , you can go in the following manner:

Steps to Follow >

❶ At first, launch an Ubuntu Terminal .

❷ Write the following command to open a file in Nano :

- nano : Opens a file in the Nano text editor.

- single_variable.sh : Name of the file.

❸ Copy the script mentioned below:

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. Next, variable var_int contains an integer value of 23 and displays with the echo command .

❹ Press CTRL+O and ENTER to save the file; CTRL+X to exit.

❺ Use the following command to make the file executable :

- chmod : changes the permissions of files and directories.

- u+x : Here, u refers to the “ user ” or the owner of the file and +x specifies the permission being added, in this case, the “ execute ” permission. When u+x is added to the file permissions, it grants the user ( owner ) permission to execute ( run ) the file.

- single_variable.sh : File name to which the permissions are being applied.

❻ Run the script by using the following command:

Case 02: Multi-Variable Assignment in a Single Line of a Bash Script

Multi-variable assignment in a single line is a concise and efficient way of assigning values to multiple variables simultaneously in Bash scripts . This method helps reduce the number of lines of code and can enhance readability in certain scenarios. Here’s an example of a multi-variable assignment in a single line.

You can follow the steps of Case 01 , to save & make the script executable.

Script (multi_variable.sh) >

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. Then, three variables x , y , and z are assigned values 1 , 2 , and 3 , respectively. The echo statements are used to print the values of each variable. Following that, two variables var1 and var2 are assigned values “ Hello ” and “ World “, respectively. The semicolon (;) separates the assignment statements within a single line. The echo statement prints the values of both variables with a space in between. Lastly, the read command is used to assign values to var3 and var4. The <<< syntax is known as a here-string , which allows the string “ Hello LinuxSimply ” to be passed as input to the read command . The input string is split into words, and the first word is assigned to var3 , while the remaining words are assigned to var4 . Finally, the echo statement displays the values of both variables.

Case 03: Assigning Variables From Command-Line Arguments

In Bash , you can assign variables from command-line arguments using special variables known as positional parameters . Here is a sample code demonstrated below.

Script (var_as_argument.sh) >

Case 04: Assign Value From Environmental Bash Variable

In Bash , you can also assign the value of an Environmental Variable to a variable. To accomplish the task you can use the following syntax :

However, make sure to replace ENV_VARIABLE_NAME with the actual name of the environment variable you want to assign. Here is a sample code that has been provided for your perusal.

Script (env_variable.sh) >

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. The value of the USER environment variable, which represents the current username, is assigned to the Bash variable username. Then the output is displayed using the echo command.

Case 05: Default Value Assignment

In Bash , you can assign default values to variables using the ${variable:-default} syntax . Note that this default value assignment does not change the original value of the variable; it only assigns a default value if the variable is empty or unset . Here’s a script to learn how it works.

Script (default_variable.sh) >

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. The next line stores a null string to the variable . The ${ variable:-Softeko } expression checks if the variable is unset or empty. As the variable is empty, it assigns the default value ( Softeko in this case) to the variable . In the second portion of the code, the LinuxSimply string is stored as a variable. Then the assigned variable is printed using the echo command .

Case 06: Assigning Value by Taking Input From the User

In Bash , you can assign a value from the user by using the read command. Remember we have used this command in Case 2 . Apart from assigning value in a single line, the read command allows you to prompt the user for input and assign it to a variable. Here’s an example given below.

Script (user_variable.sh) >

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. The read command is used to read the input from the user and assign it to the name variable . The user is prompted with the message “ Enter your name: “, and the value they enter is stored in the name variable. Finally, the script displays a message using the entered value.

Case 07: Using the “let” Command for Variable Assignment

In Bash , the let command can be used for arithmetic operations and variable assignment. When using let for variable assignment, it allows you to perform arithmetic operations and assign the result to a variable .

Script (let_var_assign.sh) >

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. then the let command performs arithmetic operations and assigns the results to variables num. Later, the echo command has been used to display the value stored in the num variable.

Case 08: Assigning Shell Command Output to a Variable

Lastly, you can assign the output of a shell command to a variable using command substitution . There are two common ways to achieve this: using backticks ( “) or using the $() syntax. Note that $() syntax is generally preferable over backticks as it provides better readability and nesting capability, and it avoids some issues with quoting. Here’s an example that I have provided using both cases.

Script (shell_command_var.sh) >

The first line #!/bin/bash specifies the interpreter to use ( /bin/bash ) for executing the script. The output of the ls -l command (which lists the contents of the current directory in long format) allocates to the variable output1 using backticks . Similarly, the output of the date command (which displays the current date and time) is assigned to the variable output2 using the $() syntax . The echo command displays both output1 and output2 .

Assignment on Assigning Variables in Bash Scripts

Finally, I have provided two assignments based on today’s discussion. Don’t forget to check this out.

- Difference: ?

- Quotient: ?

- Remainder: ?

- Write a Bash script to find and display the name of the largest file using variables in a specified directory.

In conclusion, assigning variable Bash is a crucial aspect of scripting, allowing developers to store and manipulate data efficiently. This article explored several cases to assign variables in Bash, including single-variable assignments , multi-variable assignments in a single line , assigning values from environmental variables, and so on. Each case has its advantages and limitations, and the choice depends on the specific needs of the script or program. However, if you have any questions regarding this article, feel free to comment below. I will get back to you soon. Thank You!

People Also Ask

Related Articles

- How to Declare Variable in Bash Scripts? [5 Practical Cases]

- Bash Variable Naming Conventions in Shell Script [6 Rules]

- How to Check Variable Value Using Bash Scripts? [5 Cases]

- How to Use Default Value in Bash Scripts? [2 Methods]

- How to Use Set – $Variable in Bash Scripts? [2 Examples]

- How to Read Environment Variables in Bash Script? [2 Methods]

- How to Export Environment Variables with Bash? [4 Examples]

<< Go Back to Variable Declaration and Assignment | Bash Variables | Bash Scripting Tutorial

Mohammad Shah Miran

Hey, I'm Mohammad Shah Miran, previously worked as a VBA and Excel Content Developer at SOFTEKO, and for now working as a Linux Content Developer Executive in LinuxSimply Project. I completed my graduation from Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). As a part of my job, i communicate with Linux operating system, without letting the GUI to intervene and try to pass it to our audience.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Get In Touch!

Legal Corner

Copyright © 2024 LinuxSimply | All Rights Reserved.

How to Use the basename Command in Linux Bash

- Linux Howtos

- How to Use the basename Command in Linux …

Use the basename Command to Strip Directory From Filename in Linux Bash

Use the basename command to remove suffix from filename in linux bash.

Sometimes, in Bash scripting, you may want to get the filename, not the entire path, and even get rid of the extension at the end of a file.

This article will explain using the basename command to strip the directory and suffix from a filename in Linux Bash.

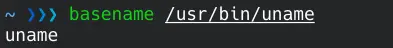

The basename command strips the directory from the filenames. It prints filename with any leading directory components removed.

After the basename command name, type the filename.

In the example above, the basename command deletes the /usr/bin directory and prints uname to the screen.

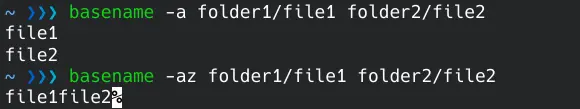

You can also give multiple filenames with the -a or --multiple parameters. The command performs the same operation for each argument and prints each on a new line with these parameters.

All output is written the same line (not the newline) using the -z or --zero parameter.

We will first remove the directory from both filenames and print both on a new line in this example. Then, we will print both on the same line with the -z parameter.

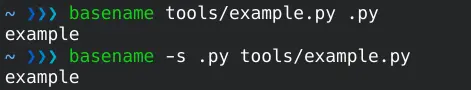

The basename command also deletes the file suffix and the directory if specified. To remove the file’s suffix, type the suffix you want to delete at the end of the command.

You can also use the -s or --suffix parameter to delete the suffix.

The example below will delete both the directory and the .py extension.

Get Suffix From Filename in Linux Bash

We can use the following code to get the suffix of a file. First, we strip the directory using the basename command and store it in the filename variable.

Then, using the double hash with the expression suffix=${filename##*.} , we get the suffix.

We get all the extensions after the first dot, not just the last suffix, using a single hash for files with multiple extensions like .en.md .

Yahya Irmak has experience in full stack technologies such as Java, Spring Boot, JavaScript, CSS, HTML.

Related Article - Bash Command

- How to Add New Users in Linux in Bash Script

- How to Check if a Command Exists in Bash

- How to Use the shift Command in Bash Scripts

- The tr Command in Linux Bash

- The sed Command in Bash

Previous: Bourne Shell Variables , Up: Shell Variables [ Contents ][ Index ]

5.2 Bash Variables

These variables are set or used by Bash, but other shells do not normally treat them specially.

A few variables used by Bash are described in different chapters: variables for controlling the job control facilities (see Job Control Variables ).

($_, an underscore.) At shell startup, set to the pathname used to invoke the shell or shell script being executed as passed in the environment or argument list. Subsequently, expands to the last argument to the previous simple command executed in the foreground, after expansion. Also set to the full pathname used to invoke each command executed and placed in the environment exported to that command. When checking mail, this parameter holds the name of the mail file.

The full pathname used to execute the current instance of Bash.

A colon-separated list of enabled shell options. Each word in the list is a valid argument for the -s option to the shopt builtin command (see The Shopt Builtin ). The options appearing in BASHOPTS are those reported as ‘ on ’ by ‘ shopt ’. If this variable is in the environment when Bash starts up, each shell option in the list will be enabled before reading any startup files. This variable is readonly.

Expands to the process ID of the current Bash process. This differs from $$ under certain circumstances, such as subshells that do not require Bash to be re-initialized. Assignments to BASHPID have no effect. If BASHPID is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

An associative array variable whose members correspond to the internal list of aliases as maintained by the alias builtin. (see Bourne Shell Builtins ). Elements added to this array appear in the alias list; however, unsetting array elements currently does not cause aliases to be removed from the alias list. If BASH_ALIASES is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

An array variable whose values are the number of parameters in each frame of the current bash execution call stack. The number of parameters to the current subroutine (shell function or script executed with . or source ) is at the top of the stack. When a subroutine is executed, the number of parameters passed is pushed onto BASH_ARGC . The shell sets BASH_ARGC only when in extended debugging mode (see The Shopt Builtin for a description of the extdebug option to the shopt builtin). Setting extdebug after the shell has started to execute a script, or referencing this variable when extdebug is not set, may result in inconsistent values.

An array variable containing all of the parameters in the current bash execution call stack. The final parameter of the last subroutine call is at the top of the stack; the first parameter of the initial call is at the bottom. When a subroutine is executed, the parameters supplied are pushed onto BASH_ARGV . The shell sets BASH_ARGV only when in extended debugging mode (see The Shopt Builtin for a description of the extdebug option to the shopt builtin). Setting extdebug after the shell has started to execute a script, or referencing this variable when extdebug is not set, may result in inconsistent values.

When referenced, this variable expands to the name of the shell or shell script (identical to $0 ; See Special Parameters , for the description of special parameter 0). Assignment to BASH_ARGV0 causes the value assigned to also be assigned to $0 . If BASH_ARGV0 is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

An associative array variable whose members correspond to the internal hash table of commands as maintained by the hash builtin (see Bourne Shell Builtins ). Elements added to this array appear in the hash table; however, unsetting array elements currently does not cause command names to be removed from the hash table. If BASH_CMDS is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

The command currently being executed or about to be executed, unless the shell is executing a command as the result of a trap, in which case it is the command executing at the time of the trap. If BASH_COMMAND is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

The value is used to set the shell’s compatibility level. See Shell Compatibility Mode , for a description of the various compatibility levels and their effects. The value may be a decimal number (e.g., 4.2) or an integer (e.g., 42) corresponding to the desired compatibility level. If BASH_COMPAT is unset or set to the empty string, the compatibility level is set to the default for the current version. If BASH_COMPAT is set to a value that is not one of the valid compatibility levels, the shell prints an error message and sets the compatibility level to the default for the current version. The valid values correspond to the compatibility levels described below (see Shell Compatibility Mode ). For example, 4.2 and 42 are valid values that correspond to the compat42 shopt option and set the compatibility level to 42. The current version is also a valid value.

If this variable is set when Bash is invoked to execute a shell script, its value is expanded and used as the name of a startup file to read before executing the script. See Bash Startup Files .

The command argument to the -c invocation option.

An array variable whose members are the line numbers in source files where each corresponding member of FUNCNAME was invoked. ${BASH_LINENO[$i]} is the line number in the source file ( ${BASH_SOURCE[$i+1]} ) where ${FUNCNAME[$i]} was called (or ${BASH_LINENO[$i-1]} if referenced within another shell function). Use LINENO to obtain the current line number.

A colon-separated list of directories in which the shell looks for dynamically loadable builtins specified by the enable command.

An array variable whose members are assigned by the ‘ =~ ’ binary operator to the [[ conditional command (see Conditional Constructs ). The element with index 0 is the portion of the string matching the entire regular expression. The element with index n is the portion of the string matching the n th parenthesized subexpression.

An array variable whose members are the source filenames where the corresponding shell function names in the FUNCNAME array variable are defined. The shell function ${FUNCNAME[$i]} is defined in the file ${BASH_SOURCE[$i]} and called from ${BASH_SOURCE[$i+1]}

Incremented by one within each subshell or subshell environment when the shell begins executing in that environment. The initial value is 0. If BASH_SUBSHELL is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

A readonly array variable (see Arrays ) whose members hold version information for this instance of Bash. The values assigned to the array members are as follows:

The major version number (the release ).

The minor version number (the version ).

The patch level.

The build version.

The release status (e.g., beta1 ).

The value of MACHTYPE .

The version number of the current instance of Bash.

If set to an integer corresponding to a valid file descriptor, Bash will write the trace output generated when ‘ set -x ’ is enabled to that file descriptor. This allows tracing output to be separated from diagnostic and error messages. The file descriptor is closed when BASH_XTRACEFD is unset or assigned a new value. Unsetting BASH_XTRACEFD or assigning it the empty string causes the trace output to be sent to the standard error. Note that setting BASH_XTRACEFD to 2 (the standard error file descriptor) and then unsetting it will result in the standard error being closed.

Set the number of exited child status values for the shell to remember. Bash will not allow this value to be decreased below a POSIX -mandated minimum, and there is a maximum value (currently 8192) that this may not exceed. The minimum value is system-dependent.

Used by the select command to determine the terminal width when printing selection lists. Automatically set if the checkwinsize option is enabled (see The Shopt Builtin ), or in an interactive shell upon receipt of a SIGWINCH .

An index into ${COMP_WORDS} of the word containing the current cursor position. This variable is available only in shell functions invoked by the programmable completion facilities (see Programmable Completion ).

The current command line. This variable is available only in shell functions and external commands invoked by the programmable completion facilities (see Programmable Completion ).

The index of the current cursor position relative to the beginning of the current command. If the current cursor position is at the end of the current command, the value of this variable is equal to ${#COMP_LINE} . This variable is available only in shell functions and external commands invoked by the programmable completion facilities (see Programmable Completion ).

Set to an integer value corresponding to the type of completion attempted that caused a completion function to be called: TAB , for normal completion, ‘ ? ’, for listing completions after successive tabs, ‘ ! ’, for listing alternatives on partial word completion, ‘ @ ’, to list completions if the word is not unmodified, or ‘ % ’, for menu completion. This variable is available only in shell functions and external commands invoked by the programmable completion facilities (see Programmable Completion ).

The key (or final key of a key sequence) used to invoke the current completion function.

The set of characters that the Readline library treats as word separators when performing word completion. If COMP_WORDBREAKS is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

An array variable consisting of the individual words in the current command line. The line is split into words as Readline would split it, using COMP_WORDBREAKS as described above. This variable is available only in shell functions invoked by the programmable completion facilities (see Programmable Completion ).

An array variable from which Bash reads the possible completions generated by a shell function invoked by the programmable completion facility (see Programmable Completion ). Each array element contains one possible completion.

An array variable created to hold the file descriptors for output from and input to an unnamed coprocess (see Coprocesses ).

An array variable containing the current contents of the directory stack. Directories appear in the stack in the order they are displayed by the dirs builtin. Assigning to members of this array variable may be used to modify directories already in the stack, but the pushd and popd builtins must be used to add and remove directories. Assignment to this variable will not change the current directory. If DIRSTACK is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

If Bash finds this variable in the environment when the shell starts with value ‘ t ’, it assumes that the shell is running in an Emacs shell buffer and disables line editing.

Expanded and executed similarly to BASH_ENV (see Bash Startup Files ) when an interactive shell is invoked in POSIX Mode (see Bash POSIX Mode ).

Each time this parameter is referenced, it expands to the number of seconds since the Unix Epoch as a floating point value with micro-second granularity (see the documentation for the C library function time for the definition of Epoch). Assignments to EPOCHREALTIME are ignored. If EPOCHREALTIME is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

Each time this parameter is referenced, it expands to the number of seconds since the Unix Epoch (see the documentation for the C library function time for the definition of Epoch). Assignments to EPOCHSECONDS are ignored. If EPOCHSECONDS is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

The numeric effective user id of the current user. This variable is readonly.

A colon-separated list of shell patterns (see Pattern Matching ) defining the list of filenames to be ignored by command search using PATH . Files whose full pathnames match one of these patterns are not considered executable files for the purposes of completion and command execution via PATH lookup. This does not affect the behavior of the [ , test , and [[ commands. Full pathnames in the command hash table are not subject to EXECIGNORE . Use this variable to ignore shared library files that have the executable bit set, but are not executable files. The pattern matching honors the setting of the extglob shell option.

The editor used as a default by the -e option to the fc builtin command.

A colon-separated list of suffixes to ignore when performing filename completion. A filename whose suffix matches one of the entries in FIGNORE is excluded from the list of matched filenames. A sample value is ‘ .o:~ ’

An array variable containing the names of all shell functions currently in the execution call stack. The element with index 0 is the name of any currently-executing shell function. The bottom-most element (the one with the highest index) is "main" . This variable exists only when a shell function is executing. Assignments to FUNCNAME have no effect. If FUNCNAME is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

This variable can be used with BASH_LINENO and BASH_SOURCE . Each element of FUNCNAME has corresponding elements in BASH_LINENO and BASH_SOURCE to describe the call stack. For instance, ${FUNCNAME[$i]} was called from the file ${BASH_SOURCE[$i+1]} at line number ${BASH_LINENO[$i]} . The caller builtin displays the current call stack using this information.

If set to a numeric value greater than 0, defines a maximum function nesting level. Function invocations that exceed this nesting level will cause the current command to abort.

A colon-separated list of patterns defining the set of file names to be ignored by filename expansion. If a file name matched by a filename expansion pattern also matches one of the patterns in GLOBIGNORE , it is removed from the list of matches. The pattern matching honors the setting of the extglob shell option.

An array variable containing the list of groups of which the current user is a member. Assignments to GROUPS have no effect. If GROUPS is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

Up to three characters which control history expansion, quick substitution, and tokenization (see History Expansion ). The first character is the history expansion character, that is, the character which signifies the start of a history expansion, normally ‘ ! ’. The second character is the character which signifies ‘quick substitution’ when seen as the first character on a line, normally ‘ ^ ’. The optional third character is the character which indicates that the remainder of the line is a comment when found as the first character of a word, usually ‘ # ’. The history comment character causes history substitution to be skipped for the remaining words on the line. It does not necessarily cause the shell parser to treat the rest of the line as a comment.

The history number, or index in the history list, of the current command. Assignments to HISTCMD are ignored. If HISTCMD is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

A colon-separated list of values controlling how commands are saved on the history list. If the list of values includes ‘ ignorespace ’, lines which begin with a space character are not saved in the history list. A value of ‘ ignoredups ’ causes lines which match the previous history entry to not be saved. A value of ‘ ignoreboth ’ is shorthand for ‘ ignorespace ’ and ‘ ignoredups ’. A value of ‘ erasedups ’ causes all previous lines matching the current line to be removed from the history list before that line is saved. Any value not in the above list is ignored. If HISTCONTROL is unset, or does not include a valid value, all lines read by the shell parser are saved on the history list, subject to the value of HISTIGNORE . The second and subsequent lines of a multi-line compound command are not tested, and are added to the history regardless of the value of HISTCONTROL .

The name of the file to which the command history is saved. The default value is ~/.bash_history .

The maximum number of lines contained in the history file. When this variable is assigned a value, the history file is truncated, if necessary, to contain no more than that number of lines by removing the oldest entries. The history file is also truncated to this size after writing it when a shell exits. If the value is 0, the history file is truncated to zero size. Non-numeric values and numeric values less than zero inhibit truncation. The shell sets the default value to the value of HISTSIZE after reading any startup files.

A colon-separated list of patterns used to decide which command lines should be saved on the history list. Each pattern is anchored at the beginning of the line and must match the complete line (no implicit ‘ * ’ is appended). Each pattern is tested against the line after the checks specified by HISTCONTROL are applied. In addition to the normal shell pattern matching characters, ‘ & ’ matches the previous history line. ‘ & ’ may be escaped using a backslash; the backslash is removed before attempting a match. The second and subsequent lines of a multi-line compound command are not tested, and are added to the history regardless of the value of HISTIGNORE . The pattern matching honors the setting of the extglob shell option.

HISTIGNORE subsumes the function of HISTCONTROL . A pattern of ‘ & ’ is identical to ignoredups , and a pattern of ‘ [ ]* ’ is identical to ignorespace . Combining these two patterns, separating them with a colon, provides the functionality of ignoreboth .

The maximum number of commands to remember on the history list. If the value is 0, commands are not saved in the history list. Numeric values less than zero result in every command being saved on the history list (there is no limit). The shell sets the default value to 500 after reading any startup files.

If this variable is set and not null, its value is used as a format string for strftime to print the time stamp associated with each history entry displayed by the history builtin. If this variable is set, time stamps are written to the history file so they may be preserved across shell sessions. This uses the history comment character to distinguish timestamps from other history lines.

Contains the name of a file in the same format as /etc/hosts that should be read when the shell needs to complete a hostname. The list of possible hostname completions may be changed while the shell is running; the next time hostname completion is attempted after the value is changed, Bash adds the contents of the new file to the existing list. If HOSTFILE is set, but has no value, or does not name a readable file, Bash attempts to read /etc/hosts to obtain the list of possible hostname completions. When HOSTFILE is unset, the hostname list is cleared.

The name of the current host.

A string describing the machine Bash is running on.

Controls the action of the shell on receipt of an EOF character as the sole input. If set, the value denotes the number of consecutive EOF characters that can be read as the first character on an input line before the shell will exit. If the variable exists but does not have a numeric value, or has no value, then the default is 10. If the variable does not exist, then EOF signifies the end of input to the shell. This is only in effect for interactive shells.

The name of the Readline initialization file, overriding the default of ~/.inputrc .

If Bash finds this variable in the environment when the shell starts, it assumes that the shell is running in an Emacs shell buffer and may disable line editing depending on the value of TERM .

Used to determine the locale category for any category not specifically selected with a variable starting with LC_ .

This variable overrides the value of LANG and any other LC_ variable specifying a locale category.

This variable determines the collation order used when sorting the results of filename expansion, and determines the behavior of range expressions, equivalence classes, and collating sequences within filename expansion and pattern matching (see Filename Expansion ).

This variable determines the interpretation of characters and the behavior of character classes within filename expansion and pattern matching (see Filename Expansion ).

This variable determines the locale used to translate double-quoted strings preceded by a ‘ $ ’ (see Locale-Specific Translation ).

This variable determines the locale category used for number formatting.

This variable determines the locale category used for data and time formatting.

The line number in the script or shell function currently executing. If LINENO is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

Used by the select command to determine the column length for printing selection lists. Automatically set if the checkwinsize option is enabled (see The Shopt Builtin ), or in an interactive shell upon receipt of a SIGWINCH .

A string that fully describes the system type on which Bash is executing, in the standard GNU cpu-company-system format.

How often (in seconds) that the shell should check for mail in the files specified in the MAILPATH or MAIL variables. The default is 60 seconds. When it is time to check for mail, the shell does so before displaying the primary prompt. If this variable is unset, or set to a value that is not a number greater than or equal to zero, the shell disables mail checking.

An array variable created to hold the text read by the mapfile builtin when no variable name is supplied.

The previous working directory as set by the cd builtin.

If set to the value 1, Bash displays error messages generated by the getopts builtin command.

A string describing the operating system Bash is running on.

An array variable (see Arrays ) containing a list of exit status values from the processes in the most-recently-executed foreground pipeline (which may contain only a single command).

If this variable is in the environment when Bash starts, the shell enters POSIX mode (see Bash POSIX Mode ) before reading the startup files, as if the --posix invocation option had been supplied. If it is set while the shell is running, Bash enables POSIX mode, as if the command

had been executed. When the shell enters POSIX mode, it sets this variable if it was not already set.

The process ID of the shell’s parent process. This variable is readonly.

If this variable is set, and is an array, the value of each set element is interpreted as a command to execute before printing the primary prompt ( $PS1 ). If this is set but not an array variable, its value is used as a command to execute instead.

If set to a number greater than zero, the value is used as the number of trailing directory components to retain when expanding the \w and \W prompt string escapes (see Controlling the Prompt ). Characters removed are replaced with an ellipsis.

The value of this parameter is expanded like PS1 and displayed by interactive shells after reading a command and before the command is executed.

The value of this variable is used as the prompt for the select command. If this variable is not set, the select command prompts with ‘ #? ’

The value of this parameter is expanded like PS1 and the expanded value is the prompt printed before the command line is echoed when the -x option is set (see The Set Builtin ). The first character of the expanded value is replicated multiple times, as necessary, to indicate multiple levels of indirection. The default is ‘ + ’.

The current working directory as set by the cd builtin.

Each time this parameter is referenced, it expands to a random integer between 0 and 32767. Assigning a value to this variable seeds the random number generator. If RANDOM is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

Any numeric argument given to a Readline command that was defined using ‘ bind -x ’ (see Bash Builtin Commands when it was invoked.

The contents of the Readline line buffer, for use with ‘ bind -x ’ (see Bash Builtin Commands ).

The position of the mark (saved insertion point) in the Readline line buffer, for use with ‘ bind -x ’ (see Bash Builtin Commands ). The characters between the insertion point and the mark are often called the region .

The position of the insertion point in the Readline line buffer, for use with ‘ bind -x ’ (see Bash Builtin Commands ).

The default variable for the read builtin.

This variable expands to the number of seconds since the shell was started. Assignment to this variable resets the count to the value assigned, and the expanded value becomes the value assigned plus the number of seconds since the assignment. The number of seconds at shell invocation and the current time are always determined by querying the system clock. If SECONDS is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

This environment variable expands to the full pathname to the shell. If it is not set when the shell starts, Bash assigns to it the full pathname of the current user’s login shell.

A colon-separated list of enabled shell options. Each word in the list is a valid argument for the -o option to the set builtin command (see The Set Builtin ). The options appearing in SHELLOPTS are those reported as ‘ on ’ by ‘ set -o ’. If this variable is in the environment when Bash starts up, each shell option in the list will be enabled before reading any startup files. This variable is readonly.

Incremented by one each time a new instance of Bash is started. This is intended to be a count of how deeply your Bash shells are nested.

This variable expands to a 32-bit pseudo-random number each time it is referenced. The random number generator is not linear on systems that support /dev/urandom or arc4random , so each returned number has no relationship to the numbers preceding it. The random number generator cannot be seeded, so assignments to this variable have no effect. If SRANDOM is unset, it loses its special properties, even if it is subsequently reset.

The value of this parameter is used as a format string specifying how the timing information for pipelines prefixed with the time reserved word should be displayed. The ‘ % ’ character introduces an escape sequence that is expanded to a time value or other information. The escape sequences and their meanings are as follows; the braces denote optional portions.

A literal ‘ % ’.

The elapsed time in seconds.

The number of CPU seconds spent in user mode.

The number of CPU seconds spent in system mode.

The CPU percentage, computed as (%U + %S) / %R.

The optional p is a digit specifying the precision, the number of fractional digits after a decimal point. A value of 0 causes no decimal point or fraction to be output. At most three places after the decimal point may be specified; values of p greater than 3 are changed to 3. If p is not specified, the value 3 is used.

The optional l specifies a longer format, including minutes, of the form MM m SS . FF s. The value of p determines whether or not the fraction is included.

If this variable is not set, Bash acts as if it had the value

If the value is null, no timing information is displayed. A trailing newline is added when the format string is displayed.

If set to a value greater than zero, TMOUT is treated as the default timeout for the read builtin (see Bash Builtin Commands ). The select command (see Conditional Constructs ) terminates if input does not arrive after TMOUT seconds when input is coming from a terminal.

In an interactive shell, the value is interpreted as the number of seconds to wait for a line of input after issuing the primary prompt. Bash terminates after waiting for that number of seconds if a complete line of input does not arrive.

If set, Bash uses its value as the name of a directory in which Bash creates temporary files for the shell’s use.

The numeric real user id of the current user. This variable is readonly.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How do I assign a variable in Bash whose name is expanded ($) from another variable?

I have a part of script as below.

I call notify with 2 parameters.

I create a dynamic variable in function with export. And the main script is in the while loop. My question is how can I use notif_$2 variable in if check? Or how can I assign it's decimal content to another variable? In the example I tried with printf it doesn't assign the content.

- 2 This question is a bit unclear. Could you please provide a Minimal, Complete, and Verifiable example ? – wjandrea Jun 17, 2017 at 15:14

TL;DR: One way is local tmp="notif_$2"; printf -v "old_notif" "%d" "${!tmp}" .

You are trying to expand a parameter (in this case, a variable) whose name must itself be obtained by expanding another parameter (in this case, a positional parameter). Furthermore, the positional parameter must be expanded, then concatenated with the text notif_ , to produce the text that must then itself be expanded.

Bash lets you do this cleanly with indirect expansion or a nameref .

The first two sections of this post show drop-in replacements for your printf -v command, using those techniques. The remaining sections are optional; they further explain these features and what you can do with them.

Way 1: Indirect Expansion

Indirect expansion is the most similar, conceptually speaking, to what you have written. Instead of the printf -v command you have now, you can use these two commands:

local makes the tmp parameter local to the shell function. If for some reason you don't want that, just omit the word local . The parameter doesn't need to be called tmp .

Indirect expansion is covered in 3.5.3 Shell Parameter Expansion in the Bash reference manual .

Way 2: Namerefs

Another way is to use a nameref. A nameref refers to a parameter. You create it from the name of the parameter, but once created, it behaves as though it is that parameter when you read from or write to it.

To use a nameref, replace your printf -v command with:

Passing the -n option to local or declare causes the newly introduced parameter to be a nameref. Notice that, in the printf command, you will use ordinary parameter expansion ( $ref ) -- not indirect expansion -- because the shell performs the indirection automatically for the nameref.

You do need local or declare here, because -n ref="notif_$2" by itself would be an error and ref="notif_$2" by itself wouldn't make a nameref. declare without the -g option in a shell function behaves like local , so you can use that style if you prefer. Or, in the unusual case where you wanted the nameref to be usable after the function returned, you could use declare -g Thanks to G-Man for pointing out a mistake about this in an earlier version of this answer.

(Depending on your needs, it might even make sense to use a nameref for more than just these two lines. To learn how, read on.)

Namerefs are covered in 3.4 Shell Parameters in the Bash reference manual .

Detailed Explanation: How Indirect Expansion Works

Shell features are most easily demonstrated through interactive use, but positional parameters (like 2 , expanded via $2 ) don't have quite the same meaning outside a shell function, and the local builtin doesn't work at all outside a function (you would use declare instead, or nothing).

So, to start with a simplified example, suppose you are working interactively in your shell and you have run:

After you run that, 1234 is stored in the parameter notif_foo . (It also exports that parameter as an environment variable.) We can see this by inspecting notif_foo :

This outputs 1234 .

Your scenario is analogous to not knowing what is in the x parameter. (In your case, you instead don't know what's in the second positional parameter passed to your shell function. I'll get to that soon.)

But you can build the parameter name and put it in another parameter:

Now y holds notif_foo , so you can use indirect expansion on y , which looks like this:

That expands to 1234 , just as if you had used "$notif_foo" . But you don't need to know $x is foo to use it.

For example, this will assign 1234 to old_notif :

If you need to format the contents of $notif_foo , you can do that, too. For example, you can use printf if you need it. This command is similar to the printf command in your question, and has the effect of assigning 1234 to old_notif :

(It also works in your original quoting style, i.e., printf -v "old_notif" "%d" "${!y}" has the same effect.)

Of course, this relies on the y parameter being suitably assigned first.

To write your shell function, you will replace $x with $2 , and you will probably want to use the local builtin to prevent your temporary variable--which I will now call tmp instead of y --from leaking out of the function's scope.

Or, using the quoting style you used in the question:

Detailed Explanation: How Namerefs Work

To try out namrefs interactively, you must use declare -n rather than local -n (because local only works--or is needed--inside the body of a shell function).

As before, suppose you have run:

Thus $notif_foo expands to 1234 . You can create a nameref to the parameter named by the result of expanding "notif_$x" :

Now y refers to the name notif_foo , and ordinary parameter expansion on y will automatically dereference that name, thereby expanding the notif_foo parameter. That is, this expands to 1234 , just as if you had used $notif_foo :

To write your shell function, you will replace $x with $2 , and I recommend using local instead of declare . I suggest also using a somewhat more descriptive name than y ; for a short function with no other nameref declarations, ref is probably adequately clear.

Or, with the quoting style you've been using:

Namerefs are Powerful

A nameref lets you do more with its referred-to parameter than just read from it. You can also, for example, write to it:

The second command creates a nameref to a parameter that might not yet exist. That's no problem! It will be created when you first assign to it, even if that assignment is through the nameref.

The third command looks like it assigns 1234 to y , but really it assigns it to notif_foo . Now both $y and $notif_foo expand to 1234 . $notif_foo expands to 1234 because that's the value stored in notif_foo ; $y expands to 1234 because y is a nameref for notif_foo .

Suppose you want to know what y refers to, though. That is, suppose you want to get notif_foo , rather than 1234 , from y . Well, you can, because with a nameref, indirect expansion has the opposite of its usual effect. This expands to notif_foo :

In your function, you could introduce notif_$2 through a nameref.

This suggests another way to deal with notif_$2 in your function: you can introduce it through a nameref, and use the nameref for each subsequent access.

Currently you have:

As an alternative, you could use:

That's more complicated that necessary, though, since presumably you only created the x1 parameter because export "notif_$2=$(date +%s)" is hard to read. ref="$(date +%s)" is just as simple, though, so you can omit the x1= line and write:

It occurs to me that you might have been using export just to assign the parameter for use in your shell. If you don't actually need to export it to child processes, then you can just use the first two lines, and that's simpler than what you have.

If you do need to export it, use all three. It's still a bit more complicated than what you have... but it may let you simplify the rest of your function, because, afterwards:

- Instead of having to write notif_$2 , you can just write ref .

- This works even in scenarios where writing notif_$2 is inadequate. That is, it is no longer necessary to do anything special (like Way 1 and Way 2 above) to expand the parameter whose name is the result of expanding notif_$2 . Just write ref .

- This even works for writing -- and creating, and unsetting -- the parameter. (After the point of declaration, ref= text writes to and can even create the referred-to parameter; unset ref unsets the referred-to parameter.)

If you're going to use a nameref throughout your whole function, you may want to think of a more meaningful name for it than ref . (The best name will, of course, be determined by the task you are writing the function to carry out.)

- Dear Eliah, thank you for your detailed explanation. I really appreciate. – Emre Canan Jun 30, 2017 at 6:26

- 1 (1) You might want to mention that namerefs are available only in bash version 4.3 and higher. (2) You say “You cannot omit local here, though [… if …] you wanted the nameref to be usable after the function has returned, you could replace it with declare .” Either you’re mistaken or I’m misunderstanding you. If I do declare -n ref=whatever in a function, then that nameref exists only until the function returns. This answer says that (in bash) variables declared (with declare , without -g ) in functions are local to the function. – G-Man Says 'Reinstate Monica' Jun 22, 2019 at 19:03

- @G-Man Thanks. What I said about local was wrong and unclear; I've edited. You're right that declare without -g in a bash function works like local . Also, my goal was to say that namerefs must be declared, which didn't come through. As for which bash versions support namerefs, I'm reluctant to add that. Trying and failing to use namerefs shouldn't cause harm, and no supported Ubuntu release packaged so old a version of bash even when the post was new. Similarly, my (and others') AU poss tend not to warn about portability, outside non-EoL Ubuntu, of find , echo , and other commands. – Eliah Kagan Jun 22, 2019 at 19:31

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged bash ..

- The Overflow Blog

- OverflowAI and the holy grail of search

- The Good, the Bad, and the Disruptive: Let us know where you stand in the...

- Featured on Meta

- Our Partnership with OpenAI

- What deliverables would you like to see out of a working group?

Hot Network Questions

- I am trying to create a superior triangular table

- Are spectral subtypes a logarithmic scale, or a linear one?

- 1 Corinthians 15:4-7 a physical, or spiritual heavenly appearance

- Image recognition in air to air missiles

- Why has the Cuban government invested little or nothing on biofuels?

- Does an object approaching a black hole ever cross the combined event horizon of the black hole and itself?

- Why does Windows command prompt command chaining not short circuit when a batch file returns non-zero?

- Reasons for implementing op-amps which are not unity-gain stable

- Can I say "Rolex watches are astronomical", "astronomical" in the sense of "expensive"?

- What does an inclination of 0 degrees mean?

- Is 1 Kings 18 talking about the daily evening sacrifice?

- Why GLM don't have an error term and why shouldn't residuals be i.i.d?

- Did Einstein ever say "Then I would feel sorry for the good Lord. The theory is correct." about the theory of relativity?

- How Much Rehab/Partial Rebuild Can Be Done While Keeping Existing Mortgage?

- Can White still castle?

- Counting consecutive units in nested lists

- How can I write the text in another language instead of English?

- New carbon road bike - scratches discovered on chain stay

- Are one in four victims of intimate partner homicides in Australia male?

- Polarizing paper "almost good enough", but no revision offered

- You can't tell me the US lacks –

- I got something for you

- Advice on making a quad-directional power/data connector

- депутат followed by a feminine name

Change the hostname of your AL2 instance

When you launch an instance into a private VPC, Amazon EC2 assigns a guest OS hostname. The type of hostname that Amazon EC2 assigns depends on your subnet settings. For more information about EC2 hostnames, see Amazon EC2 instance hostname types in the Amazon EC2 User Guide for Linux Instances .

A typical Amazon EC2 private DNS name for an EC2 instance configured to use IP-based naming with an IPv4 address looks something like this: ip-12-34-56-78.us-west-2.compute.internal , where the name consists of the internal domain, the service (in this case, compute ), the region, and a form of the private IPv4 address. Part of this hostname is displayed at the shell prompt when you log into your instance (for example, ip-12-34-56-78 ). Each time you stop and restart your Amazon EC2 instance (unless you are using an Elastic IP address), the public IPv4 address changes, and so does your public DNS name, system hostname, and shell prompt.

This information applies to Amazon Linux. For information about other distributions, see their specific documentation.

Change the system hostname

If you have a public DNS name registered for the IP address of your instance (such as webserver.mydomain.com ), you can set the system hostname so your instance identifies itself as a part of that domain. This also changes the shell prompt so that it displays the first portion of this name instead of the hostname supplied by AWS (for example, ip-12-34-56-78 ). If you do not have a public DNS name registered, you can still change the hostname, but the process is a little different.

In order for your hostname update to persist, you must verify that the preserve_hostname cloud-init setting is set to true . You can run the following command to edit or add this setting:

If the preserve_hostname setting is not listed, add the following line of text to the end of the file:

To change the system hostname to a public DNS name

Follow this procedure if you already have a public DNS name registered.

For AL2: Use the hostnamectl command to set your hostname to reflect the fully qualified domain name (such as webserver.mydomain.com ).

For Amazon Linux AMI: On your instance, open the /etc/sysconfig/network configuration file in your favorite text editor and change the HOSTNAME entry to reflect the fully qualified domain name (such as webserver.mydomain.com ).

Reboot the instance to pick up the new hostname.

Alternatively, you can reboot using the Amazon EC2 console (on the Instances page, select the instance and choose Instance state , Reboot instance ).

Log into your instance and verify that the hostname has been updated. Your prompt should show the new hostname (up to the first ".") and the hostname command should show the fully-qualified domain name.

To change the system hostname without a public DNS name

For AL2: Use the hostnamectl command to set your hostname to reflect the desired system hostname (such as webserver ).

For Amazon Linux AMI: On your instance, open the /etc/sysconfig/network configuration file in your favorite text editor and change the HOSTNAME entry to reflect the desired system hostname (such as webserver ).

Open the /etc/hosts file in your favorite text editor and change the entry beginning with 127.0.0.1 to match the example below, substituting your own hostname.

You can also implement more programmatic solutions, such as specifying user data to configure your instance. If your instance is part of an Auto Scaling group, you can use lifecycle hooks to define user data. For more information, see Run commands on your Linux instance at launch and Lifecycle hook for instance launch in the AWS CloudFormation User Guide .

Change the shell prompt without affecting the hostname

If you do not want to modify the hostname for your instance, but you would like to have a more useful system name (such as webserver ) displayed than the private name supplied by AWS (for example, ip-12-34-56-78 ), you can edit the shell prompt configuration files to display your system nickname instead of the hostname.

To change the shell prompt to a host nickname

Create a file in /etc/profile.d that sets the environment variable called NICKNAME to the value you want in the shell prompt. For example, to set the system nickname to webserver , run the following command.

Open the /etc/bashrc (Red Hat) or /etc/bash.bashrc (Debian/Ubuntu) file in your favorite text editor (such as vim or nano ). You need to use sudo with the editor command because /etc/bashrc and /etc/bash.bashrc are owned by root .

Edit the file and change the shell prompt variable ( PS1 ) to display your nickname instead of the hostname. Find the following line that sets the shell prompt in /etc/bashrc or /etc/bash.bashrc (several surrounding lines are shown below for context; look for the line that starts with [ "$PS1" ):

Change the \h (the symbol for hostname ) in that line to the value of the NICKNAME variable.

(Optional) To set the title on shell windows to the new nickname, complete the following steps.

Create a file named /etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-xterm .

Make the file executable using the following command.

Open the /etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-xterm file in your favorite text editor (such as vim or nano ). You need to use sudo with the editor command because /etc/sysconfig/bash-prompt-xterm is owned by root .

Add the following line to the file.

Log out and then log back in to pick up the new nickname value.

Change the hostname on other Linux distributions

The procedures on this page are intended for use with Amazon Linux only. For more information about other Linux distributions, see their specific documentation and the following articles:

How do I assign a static hostname to a private Amazon EC2 instance running RHEL 7 or Centos 7?

To use the Amazon Web Services Documentation, Javascript must be enabled. Please refer to your browser's Help pages for instructions.

Thanks for letting us know we're doing a good job!

If you've got a moment, please tell us what we did right so we can do more of it.

Thanks for letting us know this page needs work. We're sorry we let you down.

If you've got a moment, please tell us how we can make the documentation better.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Stack Overflow Public questions & answers; Stack Overflow for Teams Where developers & technologists share private knowledge with coworkers; Talent Build your employer brand ; Advertising Reach developers & technologists worldwide; Labs The future of collective knowledge sharing; About the company

Using basename in bash script. I showed some examples of the basename command. Let's see a couple of examples of basename in bash scripts. Suppose you have a file path variable and you want to store the file name from the path in a variable.

2. Basic Usage. The basename command allows us to extract the filename component from a given path. Here's its basic syntax: basename [OPTIONS] NAME. An example can quickly show how we can use the command and what it does: $ basename /some/path/theBaseName.txt. theBaseName.txt. By default, basename extracts the filename component from a ...

Tour Start here for a quick overview of the site Help Center Detailed answers to any questions you might have Meta Discuss the workings and policies of this site

Here, we'll create five variables. The format is to type the name, the equals sign =, and the value. Note there isn't a space before or after the equals sign. Giving a variable a value is often referred to as assigning a value to the variable. We'll create four string variables and one numeric variable, my_name=Dave.

A shell assignment is a single word, with no space after the equal sign. So what you wrote assigns an empty value to thefile; furthermore, since the assignment is grouped with a command, it makes thefile an environment variable and the assignment is local to that particular command, i.e. only the call to ls sees the assigned value.. You want to capture the output of a command, so you need to ...

As the image depicts above, the var_int variables return the assigned value 23 as the Student ID.. Case 02: Multi-Variable Assignment in a Single Line of a Bash Script. Multi-variable assignment in a single line is a concise and efficient way of assigning values to multiple variables simultaneously in Bash scripts.This method helps reduce the number of lines of code and can enhance readability ...

Using variables in bash shell scripts. In the last tutorial in this series, you learned to write a hello world program in bash. #! /bin/bash echo 'Hello, World!'. That was a simple Hello World script. Let's make it a better Hello World. Let's improve this script by using shell variables so that it greets users with their names.

The OP is using a graphical file manager and is asking how to include and use the path of the selected file not the directory in bash. Your answer ( while you clearly know how to do it ) needs more expanding to specifically address the OP's issue and help solve it. Also PATH in uppercase will overwrite the existing executable path variable. So ...