Introducing AARP Members Edition: Your source for tips to live well, members-only games, exclusive interviews, recipes and more.

AARP daily Crossword Puzzle

Hotels with AARP discounts

Life Insurance

AARP Dental Insurance Plans

AARP MEMBERSHIP

AARP Membership — $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products, hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine. Find how much you can save in a year with a membership. Learn more.

- right_container

Work & Jobs

Social Security

AARP en Español

- Membership & Benefits

- Members Edition

AARP Rewards

- AARP Rewards %{points}%

Conditions & Treatments

Drugs & Supplements

Health Care & Coverage

Health Benefits

AARP Hearing Center

Advice on Tinnitus and Hearing Loss

Get Happier

Creating Social Connections

Brain Health Resources

Tools and Explainers on Brain Health

Your Health

8 Major Health Risks for People 50+

Scams & Fraud

Personal Finance

Money Benefits

View and Report Scams in Your Area

AARP Foundation Tax-Aide

Free Tax Preparation Assistance

AARP Money Map

Get Your Finances Back on Track

How to Protect What You Collect

Small Business

Age Discrimination

Flexible Work

Freelance Jobs You Can Do From Home

AARP Skills Builder

Online Courses to Boost Your Career

31 Great Ways to Boost Your Career

ON-DEMAND WEBINARS

Tips to Enhance Your Job Search

Get More out of Your Benefits

When to Start Taking Social Security

10 Top Social Security FAQs

Social Security Benefits Calculator

Medicare Made Easy

Original vs. Medicare Advantage

Enrollment Guide

Step-by-Step Tool for First-Timers

Prescription Drugs

9 Biggest Changes Under New Rx Law

Medicare FAQs

Quick Answers to Your Top Questions

Care at Home

Financial & Legal

Life Balance

LONG-TERM CARE

Understanding Basics of LTC Insurance

State Guides

Assistance and Services in Your Area

Prepare to Care Guides

How to Develop a Caregiving Plan

End of Life

How to Cope With Grief, Loss

Recently Played

Word & Trivia

Atari® & Retro

Members Only

Staying Sharp

Mobile Apps

More About Games

Right Again! Trivia

Right Again! Trivia – Sports

Atari® Video Games

Throwback Thursday Crossword

Travel Tips

Vacation Ideas

Destinations

Travel Benefits

Outdoor Vacation Ideas

Camping Vacations

Plan Ahead for Summer Travel

AARP National Park Guide

Discover Canyonlands National Park

History & Culture

8 Amazing American Pilgrimages

Entertainment & Style

Family & Relationships

Personal Tech

Home & Living

Celebrities

Beauty & Style

Movies for Grownups

Summer Movie Preview

Jon Bon Jovi’s Long Journey Back

Looking Back

50 World Changers Turning 50

Sex & Dating

Spice Up Your Love Life

Friends & Family

How to Host a Fabulous Dessert Party

Home Technology

Caregiver’s Guide to Smart Home Tech

Virtual Community Center

Join Free Tech Help Events

Create a Hygge Haven

Soups to Comfort Your Soul

AARP Solves 25 of Your Problems

Driver Safety

Maintenance & Safety

Trends & Technology

AARP Smart Guide

How to Clean Your Car

We Need To Talk

Assess Your Loved One's Driving Skills

AARP Smart Driver Course

Building Resilience in Difficult Times

Tips for Finding Your Calm

Weight Loss After 50 Challenge

Cautionary Tales of Today's Biggest Scams

7 Top Podcasts for Armchair Travelers

Jean Chatzky: ‘Closing the Savings Gap’

Quick Digest of Today's Top News

AARP Top Tips for Navigating Life

Get Moving With Our Workout Series

You are now leaving AARP.org and going to a website that is not operated by AARP. A different privacy policy and terms of service will apply.

Go to Series Main Page

What is Medicare assignment and how does it work?

Kimberly Lankford,

Because Medicare decides how much to pay providers for covered services, if the provider agrees to the Medicare-approved amount, even if it is less than they usually charge, they’re accepting assignment.

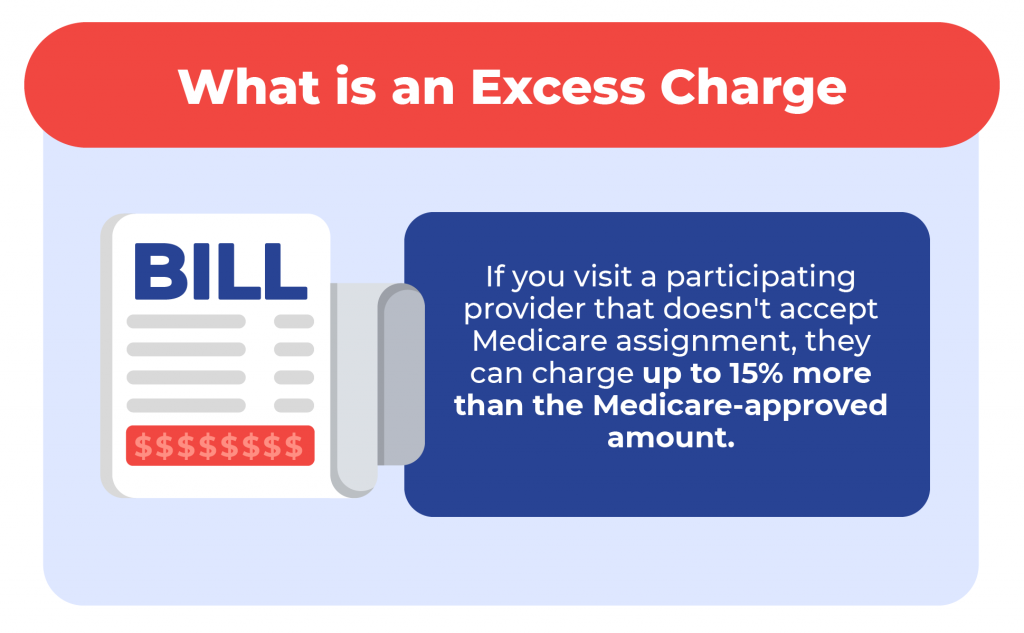

A doctor who accepts assignment agrees to charge you no more than the amount Medicare has approved for that service. By comparison, a doctor who participates in Medicare but doesn’t accept assignment can potentially charge you up to 15 percent more than the Medicare-approved amount.

That’s why it’s important to ask if a provider accepts assignment before you receive care, even if they accept Medicare patients. If a doctor doesn’t accept assignment, you will pay more for that physician’s services compared with one who does.

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine. Find out how much you could save in a year with a membership. Learn more.

How much do I pay if my doctor accepts assignment?

If your doctor accepts assignment, you will usually pay 20 percent of the Medicare-approved amount for the service, called coinsurance, after you’ve paid the annual deductible. Because Medicare Part B covers doctor and outpatient services, your $240 deductible for Part B in 2024 applies before most coverage begins.

All providers who accept assignment must submit claims directly to Medicare, which pays 80 percent of the approved cost for the service and will bill you the remaining 20 percent. You can get some preventive services and screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies , without paying a deductible or coinsurance if the provider accepts assignment.

What if my doctor doesn’t accept assignment?

A doctor who takes Medicare but doesn’t accept assignment can still treat Medicare patients but won’t always accept the Medicare-approved amount as payment in full.

This means they can charge you up to a maximum of 15 percent more than Medicare pays for the service you receive, called “balance billing.” In this case, you’re responsible for the additional charge, plus the regular 20 percent coinsurance, as your share of the cost.

How to cover the extra cost? If you have a Medicare supplement policy , better known as Medigap, it may cover the extra 15 percent, called Medicare Part B excess charges.

All Medigap policies cover Part B’s 20 percent coinsurance in full or in part. The F and G policies cover the 15 percent excess charges from doctors who don’t accept assignment, but Plan F is no longer available to new enrollees, only those eligible for Medicare before Jan. 1, 2020, even if they haven’t enrolled in Medicare yet. However, anyone who is enrolled in original Medicare can apply for Plan G.

Remember that Medigap policies only cover excess charges for doctors who accept Medicare but don’t accept assignment, and they won’t cover costs for doctors who opt out of Medicare entirely.

Good to know. A few states limit the amount of excess fees a doctor can charge Medicare patients. For example, Massachusetts and Ohio prohibit balance billing, requiring doctors who accept Medicare to take the Medicare-approved amount. New York limits excess charges to 5 percent over the Medicare-approved amount for most services, rather than 15 percent.

AARP NEWSLETTERS

%{ newsLetterPromoText }%

%{ description }%

Privacy Policy

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

How do I find doctors who accept assignment?

Before you start working with a new doctor, ask whether he or she accepts assignment. About 98 percent of providers billing Medicare are participating providers, which means they accept assignment on all Medicare claims, according to KFF.

You can get help finding doctors and other providers in your area who accept assignment by zip code using Medicare’s Physician Compare tool .

Those who accept assignment have this note under the name: “Charges the Medicare-approved amount (so you pay less out of pocket).” However, not all doctors who accept assignment are accepting new Medicare patients.

AARP® Vision Plans from VSP™

Vision insurance plans designed for members and their families

What does it mean if a doctor opts out of Medicare?

Doctors who opt out of Medicare can’t bill Medicare for services you receive. They also aren’t bound by Medicare’s limitations on charges.

In this case, you enter into a private contract with the provider and agree to pay the full bill. Be aware that neither Medicare nor your Medigap plan will reimburse you for these charges.

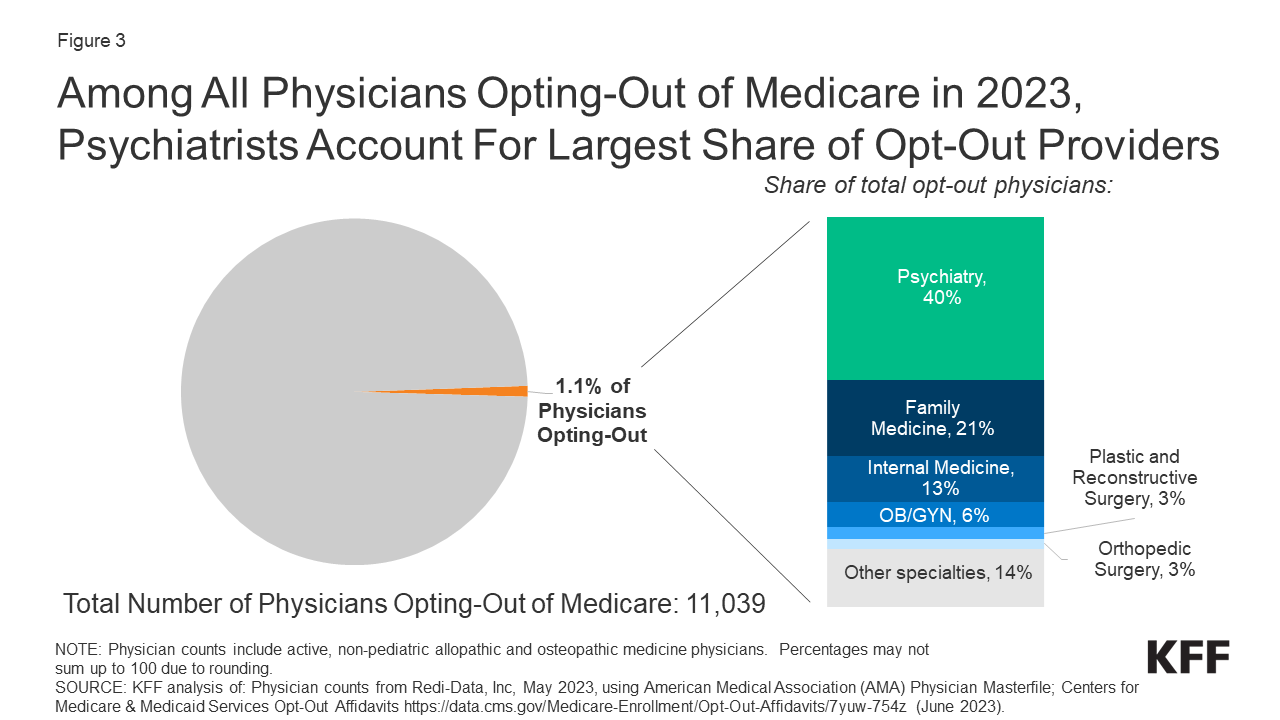

In 2023, only 1 percent of physicians who aren’t pediatricians opted out of the Medicare program, according to KFF. The percentage is larger for some specialties — 7.7 percent of psychiatrists and 4.2 percent of plastic and reconstructive surgeons have opted out of Medicare.

Keep in mind

These rules apply to original Medicare. Other factors determine costs if you choose to get coverage through a private Medicare Advantage plan . Most Medicare Advantage plans have provider networks, and they may charge more or not cover services from out-of-network providers.

Before choosing a Medicare Advantage plan, find out whether your chosen doctor or provider is covered and identify how much you’ll pay. You can use the Medicare Plan Finder to compare the Medicare Advantage plans and their out-of-pocket costs in your area.

Return to Medicare Q&A main page

Kimberly Lankford is a contributing writer who covers Medicare and personal finance. She wrote about insurance, Medicare, retirement and taxes for more than 20 years at Kiplinger’s Personal Finance and has written for The Washington Post and Boston Globe . She received the personal finance Best in Business award from the Society of American Business Editors and Writers and the New York State Society of CPAs’ excellence in financial journalism award for her guide to Medicare.

Unlock Access to AARP Members Edition

Already a Member? Login

More on Medicare

How Do I Create a Personal Online Medicare Account?

You can do a lot when you decide to look electronically

I Got a Medicare Summary Notice in the Mail. What Is It?

This statement shows what was billed, paid in past 3 months

Understanding Medicare’s Options: Parts A, B, C and D

Making sense of the alphabet soup of health care choices

Recommended for You

AARP Value & Member Benefits

Learn, earn and redeem points for rewards with our free loyalty program

AARP® Dental Insurance Plan administered by Delta Dental Insurance Company

Dental insurance plans for members and their families

The National Hearing Test

Members can take a free hearing test by phone

AARP® Staying Sharp®

Activities, recipes, challenges and more with full access to AARP Staying Sharp®

SAVE MONEY WITH THESE LIMITED-TIME OFFERS

Speak with a Licensed Insurance Agent

- (888) 335-8996

Medicare Assignment

Home / Medicare 101 / Medicare Costs / Medicare Assignment

Summary: If a provider accepts Medicare assignment, they accept the Medicare-approved amount for a covered service. Though most providers accept assignment, not all do. In this article, we’ll explain the differences between participating, non-participating, and opt-out providers. You’ll also learn how to find physicians in your area who accept Medicare assignment. Estimated Read Time: 5 min

What is Medicare Assignment

Medicare assignment is an agreement by your doctor or other healthcare providers to accept the Medicare-approved amount as the full cost for a covered service. Providers who “accept assignment” bill Medicare directly for Part B-covered services and cannot charge you more than the applicable deductible and coinsurance.

Most healthcare providers who opt-in to Medicare accept assignment. In fact, CMS reported in its Medicare Participation for Calendar Year 2024 announcement that 98 percent of Medicare providers accepted assignment in 2023.

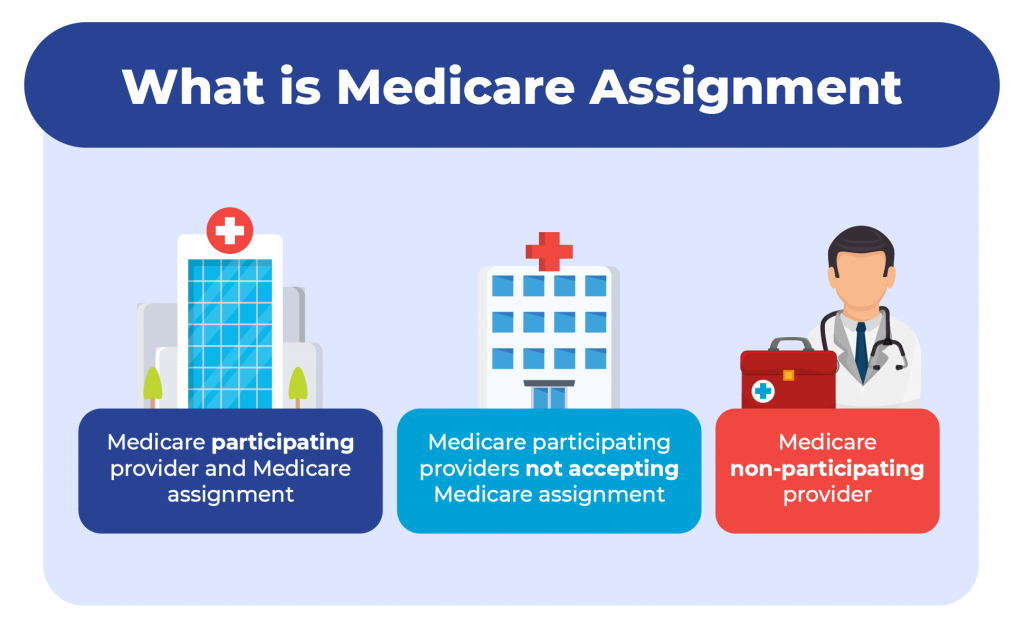

Providers who accept Medicare are divided into two groups: Participating providers and non-participating providers. Providers can decide annually whether they want to participate in Medicare assignment, or if they want to be non-participating.

Providers who do not accept Medicare Assignment can charge up to 15% above the Medicare-approved cost for a service. If this is the case, you will be responsible for the entire amount (up to 15%) above what Medicare covers.

Below, we’ll take a closer look at participating, non-participating, and opt-out physicians.

Medicare Participating Providers: Providers Who Accept Medicare Assignment

Healthcare providers who accept Medicare assignment are known as “participating providers”. To participate in Medicare assignment, a provider must enter an agreement with Medicare called the Participating Physician or Supplier Agreement. When a provider signs this agreement, they agree to accept the Medicare-approved charge as the full charge of the service. They cannot charge the beneficiary more than the applicable deductible and coinsurance for covered services.

Each year, providers can decide whether they want to be a participating or non-participating provider. Participating in Medicare assignment is not only beneficial to patients, but to providers as well. Participating providers get paid by Medicare directly, and when a participating provider bills Medicare, Medicare will automatically forward the claim information to Medicare Supplement insurers. This makes the billing process much easier on the provider’s end.

Medicare Non-Participating Providers: Providers Who Don’t Accept Assignment

Healthcare providers who are “non-participating” providers do not agree to accept assignment and can charge up to 15% over the Medicare-approved amount for a service. Non-participating Medicare providers still accept Medicare patients. However they have not agreed to accept the Medicare-approved cost as the full cost for their service.

Doctors who do not sign an assignment agreement with Medicare can still choose to accept assignment on a case-by-case basis. When non-participating providers do add on excess charges , they cannot charge more than 15% over the Medicare-approved amount. It’s worth noting that providers do not have to charge the maximum 15%; they may only charge 5% or 10% over the Medicare-approved amount.

When you receive a Medicare-covered service at a non-participating provider, you may need to pay the full amount at the time of your service; a claim will need to be submitted to Medicare for you to be reimbursed. Prior to receiving care, your provider should give you an Advanced Beneficiary Notice (ABN) to read and sign. This notice will detail the services you are receiving and their costs.

Non-participating providers should include a CMS-approved unassigned claim statement in the additional information section of your Advanced Beneficiary Notice. This statement will read:

“This supplier doesn’t accept payment from Medicare for the item(s) listed in the table above. If I checked Option 1 above, I am responsible for paying the supplier’s charge for the item(s) directly to the supplier. If Medicare does pay, Medicare will pay me the Medicare-approved amount for the item(s), and this payment to me may be less than the supplier’s charge.”

This statement basically summarizes how excess charges work: Medicare will pay the Medicare-approved amount, but you may end up paying more than that.

Your provider should submit a claim to Medicare for any covered services, however, if they refuse to submit a claim, you can do so yourself by using CMS form 1490S .

Opt-Out Providers: What You Need to Know

Opt-out providers are different than non-participating providers because they completely opt out of Medicare. What does this mean for you? If you receive supplies or services from a provider who opted out of Medicare, Medicare will not pay for any of it (except for emergencies).

Physicians who opt-out of Medicare are even harder to find than non-participating providers. According to a report by KFF.org, only 1.1% of physicians opted out of Medicare in 2023. Of those who opted out, most are physicians in specialty fields such as psychiatry, plastic and reconstructive surgery, and neurology.

How to Find A Doctor Who Accepts Medicare Assignment

Finding a doctor who accepts Medicare patients and accepts Medicare assignment is generally easier than finding a provider who doesn’t accept assignment. As we mentioned above, of all the providers who accept Medicare patients, 98 percent accept assignment.

The easiest way to find a doctor or healthcare provider who accepts Medicare assignment is by visiting Medicare.gov and using their Compare Care Near You tool . When you search for providers in your area, the Care Compare tool will let you know whether a provider is a participating or non-participating provider.

If a provider is part of a group practice that involves multiple providers, then all providers in that group must have the same participation status. As an example, we have three doctors, Dr. Smith, Dr. Jones, and Dr. Shoemaker, who are all part of a group practice called “Health Care LLC”. The group decides to accept Medicare assignment and become a participating provider. Dr. Smith decides he does not want to accept assignment, however, because he is part of the “Health Care LLC” group, he must remain a participating provider.

Using Medicare’s Care Compare tool, you can select a group practice and see their participation status. You can then view all providers who are part of that group. This makes finding doctors who accept assignment even easier.

To ensure you don’t end up paying more out-of-pocket costs than you anticipated, it’s always a good idea to check with your provider if they are a participating Medicare provider. If you have questions regarding Medicare assignment or are having trouble determining whether a provider is a participating provider, you can contact Medicare directly at 1-800-633-4227. If you have questions about excess charges or other Medicare costs and would like to speak with a licensed insurance agent, you can contact us at the number above.

Announcement About Medicare Participation for Calendar Year 2024, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed January 2024

https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-participation-announcement.pdf

Annual Medicare Participation Announcement, CMS.gov. Accessed January 2024

https://www.cms.gov/medicare-participation

Does Your Provider Accept Medicare as Full Payment? Medicare.gov. Accessed January 2024

https://www.medicare.gov/basics/costs/medicare-costs/provider-accept-Medicare

Thomas Liquori

Ashlee Zareczny

- Medicare Eligibility Requirements

- Medicare Enrollment Documents

- Apply for Medicare While Working

- Guaranteed Issue Rights

- Medicare by State

- Web Stories

- Online Guides

- Calculators & Tools

© 2024 Apply for Medicare. All Rights Reserved.

Owned by: Elite Insurance Partners LLC. This website is not connected with the federal government or the federal Medicare program. The purpose of this website is the solicitation of insurance. We do not offer every plan available in your area. Currently we represent 26 organizations which offer 3,740 products in your area. Please contact Medicare.gov or 1-800-MEDICARE or your local State Health Insurance Program to get information on all of your options.

Let us help you find the right Medicare plans today!

Simply enter your zip code below

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

CMS Newsroom

Search cms.gov.

- Physician Fee Schedule

- Local Coverage Determination

- Medically Unlikely Edits

Annual Medicare Participation Announcement

Annual Medicare Participation Open Enrollment Period

Read this year's Announcement (PDF) about the annual Medicare participation open enrollment period.

Every year from mid-November through December 31, providers can decide if they want to participate in Medicare for the upcoming year. In early to mid-November, your MAC will send a post card reminding you about the annual participation open enrollment period.

We’re proud to share that 98% of providers participate in Medicare. As you plan for 2022, this announcement provides information that may help you determine whether you want to continue or become a Medicare participating (PAR) provider.

We pledge to work with you to put patients first. To do this, we must empower patients and providers to work together to make the best health care decisions for patients.

Participating vs. Non-Participating Medicare “participation” means you agree to accept claims assignment for all Medicare-covered services to your patients. By accepting assignment, you agree to accept Medicare-allowed amounts as payment in full. You may not collect more from the patient than the Medicare deductible and coinsurance or copayment .

| Participating Provider or Supplier | Non-Participating Provider or Supplier |

|---|---|

Choose the situation that applies to you to find out what to do between mid-November and December 31 each year.

You don’t need to do anything.

Complete the Medicare Participating Physician or Supplier Agreement (CMS-460) (PDF) and mail it (or a copy) to each MAC to which you’ll send Part B claims.

Submit the Medicare Participating Physician or Supplier Agreement (CMS-460) (PDF) electronically with your enrollment application.

Write to each MAC to which you send Part B claims telling them that you’re terminating your participation in Medicare effective January 1. This written notice must be postmarked before December 31 of the previous effective year.

What You Need to Know About Medicare Assignment

If you are one of the more than 63 million Americans enrolled in Medicare and are on the lookout for a new provider, you may wonder what your options are. A good place to start? Weighing the pros and cons of choosing an Original Medicare plan versus a Medicare Advantage plan—both of which have their upsides.

Let’s say you decide on an Original Medicare plan, which many U.S. doctors accept. In your research, however, you come across the term “Medicare assignment.” Cue the head-scratching. What exactly does that mean, and how might it affect your coverage costs?

What is Medicare Assignment?

It turns out that Medicare assignment is a concept you need to understand before seeing a new doctor. First things first: Ask your doctor if they “accept assignment”—that exact phrasing—which means they have agreed to accept a Medicare-approved amount as full payment for any Medicare-covered service provided to you. If your doctor accepts assignment, that means they’ll send your whole medical bill to Medicare, and then Medicare pays 80% of the cost, while you are responsible for the remaining 20%.

A doctor who doesn’t accept assignment, however, could charge up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved amount for their services, depending on what state you live in, shouldering you with not only that additional cost but also your 20% share of the original cost. Additionally, the doctor is supposed to submit your claim to Medicare, but you may have to pay them on the day of service and then file a reimbursement claim from Medicare after the fact.

Worried that your doctor will not accept assignment? Luckily, 98% of U.S. physicians who accept Medicare patients also accept Medicare assignment, according to the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). They are known as assignment providers, participating providers, or Medicare-enrolled providers.

It can be confusing. Here’s how to assess whether your provider accepts Medicare assignment, and what that means for your out-of-pocket costs:

The 3 Types of Original Medicare Providers

1. participating providers, or those who accept medicare assignment.

These providers have an agreement with Medicare to accept the Medicare-approved amount as full payment for their services. You don’t have to pay anything other than a copay or coinsurance (depending on your plan) at the time of your visit. Typically, Medicare pays 80% of the cost, while you are responsible for the remaining 20%, as long as you have met your deductible.

2. Non-participating providers

“Most providers accept Medicare, but a small percentage of doctors are known as non-participating providers,” explains Caitlin Donovan, senior director of public relations at the National Patient Advocate Foundation (NPAF) in Washington D.C. “These may be more expensive,” she adds. Also known as non-par providers, these physicians may accept Medicare patients and insurance, but they have not agreed to take assignment Medicare in all cases. That means they’re not held to the Medicare-approved amount as payment in full. As a reminder, a doctor who doesn’t accept assignment can charge up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved amount, depending on what part of the country you live in, and you will have to pay that additional amount plus your 20% share of the original cost.

What does that mean for you? Besides being charged more than the Medicare-approved amount, you might also be required to do some legwork to get reimbursed by Medicare.

- You may have to pay the entire bill at the time of service and wait to be reimbursed 80% of the Medicare-approved amount. In most cases, the provider will submit the claim for you. But sometimes, you’ll have to submit it yourself.

- Depending on the state you live in, the provider may also charge you as much as 15% more than the Medicare-approved amount. (In New York state, for example, that add-on charge is limited to 5%.) This is called a limiting charge—and the difference, called the balance bill, is your responsibility.

There are some non-par providers, however, who accept Medicare assignment for certain services, on a case-by-case basis. Those may include any of the services—anything from hospital and hospice care to lab tests and surgery—available from any assignment-accepting doctor, with a key exception: If a non-par provider accepts assignment for a particular service, they cannot bill you more than the regular Medicare deductible and coinsurance amount for that specific treatment. Just as it’s important to confirm whether your doctor accepts assignment, it’s also important to confirm which services are included at assignment.

3. Opt-out providers

A small percentage of providers do not participate in Medicare at all. In 2020, for example, only 1% of all non-pediatric physicians nationwide opted out, and of that group, 42% were psychiatrists. “Some doctors opt out of providing Medicare coverage altogether,” notes Donovan.“In that case, the patient would pay privately.” If you were interested in seeing a physician who had opted out of Medicare, you would have to enter a private contract with that provider, and neither you nor the provider would be eligible for reimbursement from Medicare.

How do I know if my doctor accepts Medicare assignment?

The best way to find out whether your provider accepts Medicare assignment is simply to ask. First, confirm whether they are participating or non-participating—and if they are non-participating, ask whether they accept Medicare assignment for certain services.

Also, make sure to ask your provider exactly how they will be billing Medicare and what charges you might expect at the time of your visit so that you’re on the same page from the start.

Is seeing a non-participating provider who accepts Medicare assignment more expensive?

The short answer is yes. There are usually out-of-pocket costs after you’re reimbursed. But it may not cost as much as you think, and it may not be much more than if you see a participating provider. Still, it could be challenging if you’re on a fixed income.

For example, let’s say you’re seeing a physical therapist who accepts Medicare patients but not Medicare assignment. Medicare will pay $95 per visit to the provider; but your provider bills the service at $115. In most states, you’re responsible for a 15% limiting charge above $95. In this case, your bill would be 115% of $95, or $109.25.

Once you get your $95 reimbursement back from Medicare, your cost for the visit—the balance bill—would be $14.25 (plus any deductibles or copays) .

In some states, the maximum cap on the limiting charge is less than 15%. As mentioned earlier, New York state, for instance, allows only a 5% surcharge, which means that physical therapy appointment would cost you just $4.75 extra.

Bottom line: Medicare assignment providers and non-participating providers who agree to accept Medicare assignment are both viable options for patients. So if you want to see a particular provider, don’t rule them out just because they’re non-par.

While seeing a non-participating provider may still be affordable, ultimately, the biggest headache may be keeping track of claims and reimbursements, or simply setting aside the right amount of money to pay for your visit up front.

Before you schedule a visit, be sure to ask how much the service will cost. You can also estimate the payment amount based on Medicare-approved charges. A good place to start is this out-of-pocket expense calculator provided by the CMS.

What if I see a provider who opts out of Medicare altogether?

An opt-out provider will create a private contract with you, underscoring the terms of your agreement. But Medicare will not reimburse either of you for services.

Seeing a provider who does not accept Medicare will likely be more expensive. And your visits won’t count toward your deductible. But you may be able to work out paying reduced fees on a sliding scale for that provider’s services, all of which would be laid out in your contract.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Balance Billing in Health Insurance

- How It Works

- When It Happens

- What to Do If You Get a Bill

- If You Know in Advance

Balance billing happens after you’ve paid your deductible , coinsurance or copayment and your insurance company has also paid everything it’s obligated to pay toward your medical bill. If there is still a balance owed on that bill and the healthcare provider or hospital expects you to pay that balance, you’re being balance billed.

This article will explain how balance billing works, and the rules designed to protect consumers from some instances of balance billing.

Is Balance Billing Legal or Not?

Sometimes it’s legal, and sometimes it isn’t; it depends on the circumstances.

Balance billing is generally illegal :

- When you have Medicare and you’re using a healthcare provider that accepts Medicare assignment .

- When you have Medicaid and your healthcare provider has an agreement with Medicaid.

- When your healthcare provider or hospital has a contract with your health plan and is billing you more than that contract allows.

- In emergencies (with the exception of ground ambulance charges), or situations in which you go to an in-network hospital but unknowingly receive services from an out-of-network provider.

In the first three cases, the agreement between the healthcare provider and Medicare, Medicaid, or your insurance company includes a clause that prohibits balance billing.

For example, when a hospital signs up with Medicare to see Medicare patients, it must agree to accept the Medicare negotiated rate, including your deductible and/or coinsurance payment, as payment in full. This is called accepting Medicare assignment .

And for the fourth case, the No Surprises Act , which took effect in 2022, protects you from "surprise" balance billing.

Balance billing is usually legal :

- When you choose to use a healthcare provider that doesn’t have a relationship or contract with your insurer (including ground ambulance charges, even after implementation of the No Surprises Act).

- When you’re getting services that aren’t covered by your health insurance policy, even if you’re getting those services from a provider that has a contract with your health plan.

The first case (a provider not having an insurer relationship) is common if you choose to seek care outside of your health insurance plan's network.

Depending on how your plan is structured, it may cover some out-of-network costs on your behalf. But the out-of-network provider is not obligated to accept your insurer's payment as payment in full. They can send you a bill for the remainder of the charges, even if it's more than your plan's out-of-network copay or deductible.

(Some health plans, particularly HMOs and EPOs , simply don't cover non-emergency out-of-network services at all, which means they would not cover even a portion of the bill if you choose to go outside the plan's network.)

Getting services that are not covered is a situation that may arise, for example, if you obtain cosmetic procedures that aren’t considered medically necessary, or fill a prescription for a drug that isn't on your health plan's formulary . You’ll be responsible for the entire bill, and your insurer will not require the medical provider to write off any portion of the bill—the claim would simply be rejected.

Prior to 2022, it was common for people to be balance billed in emergencies or by out-of-network providers that worked at in-network hospitals. In some states, state laws protected people from these types of surprise balance billing if they had state-regulated health plans.

But not all states had these protections. And the majority of people with employer-sponsored health insurance are covered under self-insured plans, which are not subject to state regulations. This is why the No Surprises Act was so necessary.

How Balance Billing Works

When you get care from a doctor, hospital, or other healthcare provider that isn’t part of your insurer’s provider network (or, if you have Medicare, from a provider that has opted out of Medicare altogether , which is rare but does apply in some cases ), that healthcare provider can charge you whatever they want to charge you (with the exception of emergencies or situations where you receive services from an out-of-network provider while you're at an in-network hospital).

Since your insurance company hasn’t negotiated any rates with that provider, they aren't bound by a contract with your health plan.

Medicare Limiting Charge

If you have Medicare and your healthcare provider is a nonparticipating provider but hasn't entirely opted out of Medicare, you can be charged up to 15% more than the allowable Medicare amount for the service you receive (some states impose a lower limit).

This 15% cap is known as the limiting charge, and it serves as a restriction on balance billing in some cases. If your healthcare provider has opted out of Medicare entirely, they cannot bill Medicare at all and you'll be responsible for the full cost of your visit.

If your health insurance company agrees to pay a percentage of your out-of-network care, the health plan doesn’t pay a percentage of what’s actually billed . Instead, it pays a percentage of what it says should have been billed, otherwise known as a reasonable and customary amount.

As you might guess, the reasonable and customary amount is usually lower than the amount you’re actually billed. The balance bill comes from the gap between what your insurer says is reasonable and customary, and what the healthcare provider or hospital actually charges.

Let's take a look at an example in which a person's health plan has 20% coinsurance for in-network hospitalization and 40% coinsurance for out-of-network hospitalization. And we're going to assume that the No Surprises Act does not apply (ie, that the person chooses to go to an out-of-network hospital, and it's not an emergency situation).

In this scenario, we'll assume that the person already met their $1,000 in-network deductible and $2,000 out-of-network deductible earlier in the year (so the example is only looking at coinsurance).

And we'll also assume that the health plan has a $6,000 maximum out-of-pocket for in-network care, but no cap on out-of-pocket costs for out-of-network care:

| Coverage | 20% coinsurance with a $6,000 maximum out-of-pocket, including $1,000 deductible that has already been met earlier in the year | 40% coinsurance with no maximum out-of-pocket, (but a deductible that has already been met) with balance bill |

| Hospital charges | $60,000 | $60,000 |

| Insurer negotiates a discounted rate of | $40,000 | There is no discount because this hospital is out-of-network |

| Insurer's reasonable and customary rate | Not applicable, since the insurer has a contract with the hospital | $45,000 |

| Insurer pays | $35,000 (80% of the negotiated rate until the patient hits their maximum out-of-pocket, then the insurer pays 100%) | $27,000 (60% of the $45,000 reasonable and customary rate) |

| You pay coinsurance of | $5,000 (20% of the negotiated rate, until you hit the maximum out-of-pocket of $6,000. This is based on the $1,000 deductible paid earlier in the year, plus the $5,000 from this hospitalization) | $18,000 (40% of $45,000) |

| Balance billed amount | $0 (the hospital is required to write-off the other $20,000 as part of their contract with your insurer) | $15,000 (The hospital's original bill minus insurance and coinsurance payments) |

| When paid in full, you’ve paid | $5,000 (Your maximum out-of-pocket has been met. Keep in mind that you already paid $1,000 earlier in the year for your deductible) | $33,000 (Your coinsurance plus the remaining balance.) |

When Does Balance Billing Happen?

In the United States, balance billing usually happens when you get care from a healthcare provider or hospital that isn’t part of your health insurance company’s provider network or doesn’t accept Medicare or Medicaid rates as payment in full.

If you have Medicare and your healthcare provider has opted out of Medicare entirely, you're responsible for paying the entire bill yourself. But if your healthcare provider hasn't opted out but just doesn't accept assignment with Medicare (ie, doesn't accept the amount Medicare pays as payment in full), you could be balance billed up to 15% more than Medicare's allowable charge, in addition to your regular deductible and/or coinsurance payment.

Surprise Balance Billing

Receiving care from an out-of-network provider can happen unexpectedly, even when you try to stay in-network. This can happen in emergency situations—when you may simply have no say in where you're treated or no time to get to an in-network facility—or when you're treated by out-of-network providers who work at in-network facilities.

For example, you go to an in-network hospital, but the radiologist who reads your X-rays isn’t in-network. The bill from the hospital reflects the in-network rate and isn't subject to balance billing, but the radiologist doesn’t have a contract with your insurer, so they can charge you whatever they want. And prior to 2022, they were allowed to send you a balance bill unless state law prohibited it.

Similar situations could arise with:

- Anesthesiologists

- Pathologists (laboratory doctors)

- Neonatologists (doctors for newborns)

- Intensivists (doctors who specialize in ICU patients)

- Hospitalists (doctors who specialize in hospitalized patients)

- Radiologists (doctors who interpret X-rays and scans)

- Ambulance services to get you to the hospital, especially air ambulance services, where balance billing was frighteningly common

- Durable medical equipment suppliers (companies that provide the crutches, braces, wheelchairs, etc. that people need after a medical procedure)

These "surprise" balance billing situations were particularly infuriating for patients, who tended to believe that as long as they had selected an in-network medical facility, all of their care would be covered under the in-network terms of their health plan.

To address this situation, many states enacted consumer protection rules that limited surprise balance billing prior to 2022. But as noted above, these state rules don't protect people with self-insured employer-sponsored health plans, which cover the majority of people who have employer-sponsored coverage.

There had long been broad bipartisan support for the idea that patients shouldn't have to pay additional, unexpected charges just because they needed emergency care or inadvertently received care from a provider outside their network, despite the fact that they had purposely chosen an in-network medical facility. There was disagreement, however, in terms of how these situations should be handled—should the insurer have to pay more, or should the out-of-network provider have to accept lower payments? This disagreement derailed numerous attempts at federal legislation to address surprise balance billing.

But the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, which was enacted in December 2020, included broad provisions (known as the No Surprises Act) to protect consumers from surprise balance billing as of 2022. The law applies to both self-insured and fully-insured plans, including grandfathered plans, employer-sponsored plans, and individual market plans.

It protects consumers from surprise balance billing charges in nearly all emergency situations and situations when out-of-network providers offer services at in-network facilities, but there's a notable exception for ground ambulance charges.

This is still a concern, as ground ambulances are among the medical providers most likely to balance bill patients and least likely to be in-network, and patients typically have no say in what ambulance provider comes to their rescue in an emergency situation. But other than ground ambulances, patients are no longer subject to surprise balance bills as of 2022.

The No Surprises Act did call for the creation of a committee to study ground ambulance charges and make recommendations for future legislation to protect consumers. The Biden Administration announced the members of that committee in late 2022, and the committee began holding meetings in May 2023.

Balance billing continues to be allowed in other situations (for example, the patient simply chooses to use an out-of-network provider). Balance billing can also still occur when you’re using an in-network provider, but you’re getting a service that isn’t covered by your health insurance. Since an insurer doesn’t negotiate rates for services it doesn’t cover, you’re not protected by that insurer-negotiated discount. The provider can charge whatever they want, and you’re responsible for the entire bill.

It is important to note that while the No Surprises Act prohibits balance bills from out-of-network working at in-network facilities, the final rule for implementation of the law defines facilities as "hospitals, hospital outpatient departments, critical access hospitals, and ambulatory surgical centers." Other medical facilities are not covered by the consumer protections in the No Surprises Act.

Balance billing doesn’t usually happen with in-network providers or providers that accept Medicare assignment . That's because if they balance bill you, they’re violating the terms of their contract with your insurer or Medicare. They could lose the contract, face fines, suffer severe penalties, and even face criminal charges in some cases.

If You Get an Unexpected Balance Bill

Receiving a balance bill is a stressful experience, especially if you weren't expecting it. You've already paid your deductible and coinsurance and then you receive a substantial additional bill—what do you do next?

First, you'll want to try to figure out whether the balance bill is legal or not. If the medical provider is in-network with your insurance company, or you have Medicare or Medicaid and your provider accepts that coverage, it's possible that the balance bill was a mistake (or, in rare cases, outright fraud).

And if your situation is covered under the No Surprises Act (ie, an emergency, or an out-of-network provider who treated you at an in-network facility), you should not be subject to a balance bill. So be sure you understand what charges you're actually responsible for before paying any medical bills.

If you think that the balance bill was an error, contact the medical provider's billing office and ask questions. Keep a record of what they tell you so that you can appeal to your state's insurance department if necessary.

If the medical provider's office clarifies that the balance bill was not an error and that you do indeed owe the money, consider the situation—did you make a mistake and select an out-of-network healthcare provider? Or was the service not covered by your health plan?

If you went to an in-network facility for a non-emergency, did you waive your rights under the No Surprises Act (NSA) and then receive a balance bill from an out-of-network provider? This is still possible in limited circumstances, but you would have had to sign a document indicating that you had waived your NSA protections.

Negotiate With the Medical Office

If you've received a legitimate balance bill, you can ask the medical office to cut you some slack. They may be willing to agree to a payment plan and not send your bill to collections as long as you continue to make payments.

Or they may be willing to reduce your total bill if you agree to pay a certain amount upfront. Be respectful and polite, but explain that the bill caught you off guard. And if it's causing you significant financial hardship, explain that too.

The healthcare provider's office would rather receive at least a portion of the billed amount rather than having to wait while the bill is sent to collections. So the sooner you reach out to them, the better.

Negotiate With Your Insurance Company

You can also negotiate with your insurer. If your insurer has already paid the out-of-network rate on the reasonable and customary charge, you’ll have difficulty filing a formal appeal since the insurer didn’t actually deny your claim . It paid your claim, but at the out-of-network rate.

Instead, request a reconsideration. You want your insurance company to reconsider the decision to cover this as out-of-network care , and instead cover it as in-network care. You’ll have more luck with this approach if you had a compelling medical or logistical reason for choosing an out-of-network provider .

If you feel like you’ve been treated unfairly by your insurance company, follow your health plan’s internal complaint resolution process.

You can get information about your insurer’s complaint resolution process in your benefits handbook or from your human resources department. If this doesn’t resolve the problem, you can complain to your state’s insurance department.

- Learn more about your internal and external appeal rights.

- Find contact information for your Department of Insurance using this resource .

If your health plan is self-funded , meaning your employer is the entity actually paying the medical bills even though an insurance company may administer the plan, then your health plan won't fall under the jurisdiction of your state’s department of insurance.

Self-funded plans are instead regulated by the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefit Services Administration. Get more information from the EBSA’s consumer assistance web page or by calling an EBSA benefits advisor at 1-866-444-3272.

If You Know You’ll Be Legally Balance Billed

If you know in advance that you’ll be using an out-of-network provider or a provider that doesn’t accept Medicare assignment, you have some options. However, none of them are easy and all require some negotiating.

Ask for an estimate of the provider’s charges. Next, ask your insurer what they consider the reasonable and customary charge for this service to be. Getting an answer to this might be tough, but be persistent.

Once you have estimates of what your provider will charge and what your insurance company will pay, you’ll know how far apart the numbers are and what your financial risk is. With this information, you can narrow the gap. There are only two ways to do this: Get your provider to charge less or get your insurer to pay more.

Ask the provider if he or she will accept your insurance company’s reasonable and customary rate as payment in full. If so, get the agreement in writing, including a no-balance-billing clause.

If your provider won’t accept the reasonable and customary rate as payment in full, start working on your insurer. Ask your insurer to increase the amount they’re calling reasonable and customary for this particular case.

Present a convincing argument by pointing out why your case is more complicated, difficult, or time-consuming to treat than the average case the insurer bases its reasonable and customary charge on.

Single-Case Contract

Another option is to ask your insurer to negotiate a single-case contract with your out-of-network provider for this specific service.

A single-case contract is more likely to be approved if the provider is offering specialized services that aren't available from locally-available in-network providers, or if the provider can make a case to the insurer that the services they're providing will end up being less expensive in the long-run for the insurance company.

Sometimes they can agree upon a single-case contract for the amount your insurer usually pays its in-network providers. Sometimes they’ll agree on a single-case contract at the discount rate your healthcare provider accepts from the insurance companies she’s already in-network with.

Or, sometimes they can agree on a single-case contract for a percentage of the provider’s billed charges. Whatever the agreement, make sure it includes a no-balance-billing clause.

Ask for the In-Network Coinsurance Rate

If all of these options fail, you can ask your insurer to cover this out-of-network care using your in-network coinsurance rate. While this won’t prevent balance billing, at least your insurer will be paying a higher percentage of the bill since your coinsurance for in-network care is lower than for out-of-network care.

If you pursue this option, have a convincing argument as to why the insurer should treat this as in-network. For example, there are no local in-network surgeons experienced in your particular surgical procedure, or the complication rates of the in-network surgeons are significantly higher than those of your out-of-network surgeon.

Balance billing refers to the additional bill that an out-of-network medical provider can send to a patient, in addition to the person's normal cost-sharing and the payments (if any) made by their health plan. The No Surprises Act provides broad consumer protections against "surprise" balance billing as of 2022.

A Word From Verywell

Try to prevent balance billing by staying in-network, making sure your insurance company covers the services you’re getting, and complying with any pre-authorization requirements. But rest assured that the No Surprises Act provides broad protections against surprise balance billing.

This means you won't be subject to balance bills in emergencies (except for ground ambulance charges, which can still generate surprise balance bills) or in situations where you go to an in-network hospital but unknowingly receive care from an out-of-network provider.

Congress.gov. H.R.133—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 . Enacted December 27, 2021.

Kona M. The Commonwealth Fund. State balance billing protections . April 20, 2020.

Data.CMS.gov. Opt Out Affidavits .

Chhabra, Karan; Schulman, Kevin A.; Richman, Barak D. Health Affairs. Are Air Ambulances Truly Flying Out Of Reach? Surprise-Billing Policy And The Airline Deregulation Act . October 17, 2019.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2022 Employer Health Benefits Survey .

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Members of New Federal Advisory Committee Named to Help Improve Ground Ambulance Disclosure and Billing Practices for Consumers . December 13, 2022.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Advisory Committee on Ground Ambulance and Patient Billing (GAPB) .

Internal Revenue Service; Employee Benefits Security Administration; Health and Human Services Department. Requirements Related to Surprise Billing . August 26, 2022.

National Conference of State Legislatures. States Tackling "Balance Billing" Issue . July 2017.

By Elizabeth Davis, RN Elizabeth Davis, RN, is a health insurance expert and patient liaison. She's held board certifications in emergency nursing and infusion nursing.

Medicare Assignment: Understanding How It Works

Medicare assignment is a term used to describe how a healthcare provider agrees to accept the Medicare-approved amount. Depending on how you get your Medicare coverage, it could be essential to understand what it means and how it can affect you.

What is Medicare assignment?

Medicare sets a fixed cost to pay for every benefit they cover. This amount is called Medicare assignment.

You have the largest healthcare provider network with over 800,000 providers nationwide on Original Medicare . You can see any doctor nationwide that accepts Medicare.

Understanding the differences between your cost and the difference between accepting Medicare and accepting Medicare assignment could be worth thousands of dollars.

Doctors that accept Medicare

Your healthcare provider can fall into one of three categories:

Medicare participating provider and Medicare assignment

Medicare participating providers not accepting medicare assignment, medicare non-participating provider.

More than 97% of healthcare providers nationwide accept Medicare. Because of this, you can see almost any provider throughout the United States without needing referrals.

Let’s discuss the three categories the healthcare providers fall into.

Participating providers are doctors or healthcare providers who accept assignment. This means they will never charge more than the Medicare-approved amount.

Some non-participating providers accept Medicare but not Medicare assignment. This means you can see them the same way a provider accepts assignment.

You need to understand that since they don’t take the assigned amount, they can charge up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved amount.

Since Medicare will only pay the Medicare-approved amount, you’ll be responsible for these charges. The 15% overcharge is called an excess charge. A few states don’t allow or limit the amount or services of the excess charges. Only about 5% of providers charge excess charges.

Opt-out providers don’t accept Original Medicare, and these healthcare providers are in the minority in the United States. If healthcare providers don’t accept Medicare, they won’t be paid by Medicare.

This means choosing to see a provider that doesn’t accept Medicare will leave you responsible for 100% of what they charge you. These providers may be in-network for a Medicare Advantage plan in some cases.

Avoiding excess charges

Excess charges could be large or small depending on the service and the Medicare-approved amount. Avoiding these is easy. The simplest way is to ask your provider if they accept assignment before service.

If they say yes, they don’t issue excess charges. Or, on Medicare.gov , a provider search tool will allow you to look up your healthcare provider and show if they accept Medicare assignment or not.

Medicare Supplement and Medicare assignment

Medigap plans are additional insurance that helps cover your Medicare cost-share . If you are on specific plans, they’ll pay any extra costs from healthcare providers that accept Medicare but not Medicare assigned amount. Most Medicare Supplement plans don’t cover the excess charges.

The top three Medicare Supplement plans cover excess charges if you use a provider that accepts Medicare but not Medicare assignment.

Medicare Advantage and Medicare assignment

Medicare assignment does not affect Medicare Advantage plans since Medicare Advantage is just another way to receive your Medicare benefits. Since your Medicare Advantage plan handles your healthcare benefits, they set the terms.

Most Medicare Advantage plans require you to use network providers. If you go out of the network, you may pay more. If you’re on an HMO, you’d be responsible for the entire charge of the provider not being in the network.

Do all doctors accept Medicare Supplement plans?

All doctors that accept Original Medicare accept Medicare Supplement plans. Some doctors don’t accept Medicare. In this case, those doctors won’t accept Medicare Supplements.

Where can I find doctors who accept Medicare assignment?

Medicare has a physician finder tool that will show if a healthcare provider participates in Medicare and accepts Medicare assignments. Most doctors nationwide do accept assignment and therefore don’t charge the Part B excess charges.

Why do some doctors not accept Medicare?

Some doctors are called concierge doctors. These doctors don’t accept any insurance and require cash payments.

What is a Medicare assignment?

Accepting Medicare assignment means that the healthcare provider has agreed only to charge the approved amount for procedures and services.

What does it mean if a doctor does not accept Medicare assignment?

The doctor can change more than the Medicare-approved amount for procedures and services. You could be responsible for up to a 15% excess charge.

How many doctors accept Medicare assignment?

About 97% of doctors agree to accept assignment nationwide.

Is accepting Medicare the same as accepting Medicare assignment?

No. If a doctor accepts Medicare and accepts Medicare assigned amount, they’ll take what Medicare approves as payment in full.

If they accept Medicare but not Medicare assignment, they can charge an excess charge of up to 15% above the Medicare-approved amount. You could be responsible for this excess charge.

What is the Medicare-approved amount?

The Medicare-approved amount is Medicare’s charge as the maximum for any given medical service or procedure. Medicare has set forth an approved amount for every covered item or service.

Can doctors balance bill patients?

Yes, if that doctor is a Medicare participating provider not accepting Medicare assigned amount. The provider may bill up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved amount.

What happens if a doctor does not accept Medicare?

Doctors that don’t accept Medicare will require you to pay their full cost when using their services. Since these providers are non-participating, Medicare will not pay or reimburse for any services rendered.

Get help avoiding Medicare Part B excess charges

Whether it’s Medicare assignment, or anything related to Medicare, we have licensed agents that specialize in this field standing by to assist.

Give us a call, or fill out our online request form . We are happy to help answer questions, review options, and guide you through the process.

Related Articles

- What are Medicare Part B Excess Charges?

- How to File a Medicare Reimbursement Claim?

- Medicare Defined Coinsurance: How it Works?

- Welcome to Medicare Visit

- Guide to the Medicare Program

CALL NOW (833) 972-1339

What Does It Mean for a Doctor to Accept Medicare Assignment?

Written by: Malini Ghoshal, RPh, MS

Reviewed by: Malinda Cannon, Licensed Insurance Agent

Key Takeaways

Doctors who accept Medicare assignment are paid agreed-upon rates for services.

It’s important to verify that your doctor accepts assignment before receiving services to avoid high out-of-pocket costs.

A doctor or clinician may be “non-participating” but can still agree to accept Medicare assignment for some services.

If you visit a doctor or clinician who has opted out (doesn’t accept Medicare), you may have to pay for your entire visit cost unless it’s a medical emergency.

Medigap Supplemental insurance (Medigap) plans won’t pay for service costs from doctors who don’t accept assignment.

One of the things that Original Medicare beneficiaries often enjoy about their coverage is that they can use it anywhere in the country. Unlike plans with provider networks, they can visit doctors either at home or on the road; both are covered the same.

But do all doctors accept Medicare patients?

Truth is, this wide-ranging coverage area only applies to doctors who accept Medicare assignment. Fortunately, most do. If you’re eligible for Medicare, it’s important to visit doctors and clinicians who accept Medicare assignment. This will help keep your out-of-pocket costs within your control. Doctors who agree to accept Medicare assignment sign an agreement that they’re willing to accept payment from Medicare for their services.

If you’re a current beneficiary or nearing enrollment, you may have other questions. Do all doctors accept Medicare Advantage plans? What about Medicare Supplement insurance (Medigap)? Read on to learn how to find doctors that accept Medicare assignment and how this keeps your healthcare costs down.

Let’s find your ideal Medicare Advantage plan.

What Is Medicare Assignment of Benefits?

When you’re eligible for Medicare, you have the option to visit doctors and clinicians who accept assignment. This means they are Medicare-approved providers who agree to receive Medicare reimbursement rates for covered services. This helps save you money.

If you have Original Medicare (Part A and B), your doctor visits are covered by your Part B plan. Inpatient services such as hospital stays and some skilled nursing care are covered by Part A .

In order for a participating doctor (or facility) to bill Medicare and be reimbursed, you must authorize Medicare to reimburse your doctor directly for your covered services. This is called the Medicare assignment of benefits. You transfer your right to receive Medicare payment for a covered service to your doctor or other provider.

Note: If you have a Medicare Supplement insurance ( Medigap ) plan to pay for out-of-pocket costs, you may also need to sign a separate assignment of benefits form for Medigap reimbursement. More on Medigap below.

How Can I Find Doctors Near Me That Accept Medicare?

There are several ways to find doctors and other clinicians who accept Medicare assignment close to you.

First, let’s take a look at the different types of Medicare providers.

They include:

Participating providers: Medicare-participating doctors and providers sign a participation agreement stating they will accept Medicare reimbursement rates for their services.

Non-participating providers: Doctors or providers who are non-participating providers are eligible to accept Medicare assignment but haven’t signed a Medicare agreement. They may choose to accept assignment on a case-by-case basis. If you visit a non-participating provider, make sure to ask if they accept assignment for your particular service. Also get a copy of their fees. They will need to select “yes” on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS Form 1500 to accept assignment for the service.

Opt-out providers: Some doctors and other providers choose not to accept Medicare. If they choose to opt out, the period is two years (based on Medicare guidelines). The opt-out automatically renews if the provider doesn’t request a change in their status. You would be responsible for paying all costs for services received from an opt-out provider. You cannot bill Medicare for reimbursement unless the service was an urgent or emergency medical need. According to a report from KFF , roughly 1% of non-pediatric physicians opted out of Medicare in 2023.

Visiting a doctor who doesn’t accept assignment may cost you more. These providers can charge you up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved rate for a given service. This 15% charge is called the limiting charge. Some states limit this extra charge to a certain percent. This may also be called the Part B excess charge.

Here are some tips for finding doctors and providers who accept Medicare assignment:

- The easiest way to find a doctor who accepts Medicare assignment is to contact their office and ask them directly.

- If you’re looking for a new doctor, you can use the Medicare search tool to find clinicians and doctors that accept Medicare assignment.

- You can also ask a state health insurance assistance program (SHIP) representative for help in locating a doctor that accepts Medicare assignment.

- Don’t assume that having a longstanding relationship with your doctor means nothing will ever change. Check in with them to make sure they still accept Medicare assignment and whether they’re planning to opt out.

Note: Your doctor can choose to become a non-participating provider or opt out of participating in Medicare. It’s important to verify they accept Medicare assignment before receiving any services.

Can I bundle multiple benefits into one plan?

Do Doctors Who Accept Medicare Have to Accept Supplement Plans?

If your doctor accepts Medicare assignment and you have Original Medicare (Medicare Part A and Part B) with a Medicare Supplement (Medigap) plan, they will accept the supplemental insurance. Depending on your Medigap plan coverage , it may pay all or part of your out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles, copayments and coinsurance.

However, if you have a Medicare Advantage plan (Part C), you may have a network of covered doctors under the plan. If you visit an out-of-network doctor, you may need to pay all or part of the cost for your services.

Keep in mind that you can’t have a Medigap supplemental plan if you have a Medicare Advantage plan.

If you have questions or want to learn more about different Medicare plans like Original Medicare with Medigap versus Medicare Advantage, GoHealth has licensed insurance agents ready to help. They can shop your different options and offer impartial guidance where you need it.

Do Most Doctors Accept Medicare Advantage Plans?

Many doctors accept Medicare Advantage (Part C) plans, but these plans often use provider networks. These networks are groups of doctors and providers in an area that have agreed to treat an insurance company’s customers. If you have a Part C plan, you may be required to see in-network doctors with few exceptions. However, these types of plans are popular options for all-in-one coverage for your health needs. Plans must offer Part A and B coverage, plus a majority also include Part D , or prescription drug coverage. But whether a doctor accepts a Medicare Advantage plan may depend on where you live and the type of Medicare Advantage plan you have.

There are several types of Medicare Advantage plans including:

- Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): These plans have a network of covered providers, as well as a primary care physician to manage your care. If you visit a doctor outside your plan network, you may have to pay the full cost of your visit.

- Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): You’ll probably still have a primary care physician, but these are more flexible plans that allow you to go out of network in some cases. But you may have to pay more.

- Private Fee for Service (PFFS): You may be able to visit any doctor or provider with these plans, but your costs may be higher.

- Special Needs Plan (SNP): This type of plan is only for certain qualified individuals who either have a specific health condition ( C-SNP ) or who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare insurance ( D-SNP ).

Find the Medicare Plan that works for you.

What Are Medicare Assignment Codes?

Medicare assignment codes help Medicare pay for covered services. If your doctor or other provider accepts assignment and is a participating provider, they will file for reimbursement for services with a CMS-1500 form and the code will be “assigned.”

But non-participating providers can select “not assigned.” This means they are not accepting Medicare-assigned rates for a given service. They can charge up to 15% over the full Medicare rate for the service.

If you go to a doctor or provider who accepts assignment, you don’t need to file your own claim. Your doctor’s office will directly file with Medicare. Always check to make sure your doctor accepts assignment to avoid excess charges from your visit.

Health Insurance Claim Form . CMS.gov.

Lower costs with assignment . Medicare.gov.

How Many Physicians Have Opted-Out of the Medicare Program? KFF.org.

Joining a plan . Medicare.gov.

This website is operated by GoHealth, LLC., a licensed health insurance company. The website and its contents are for informational and educational purposes; helping people understand Medicare in a simple way. The purpose of this website is the solicitation of insurance. Contact will be made by a licensed insurance agent/producer or insurance company. Medicare Supplement insurance plans are not connected with or endorsed by the U.S. government or the federal Medicare program. Our mission is to help every American get better health insurance and save money. Any information we provide is limited to those plans we do offer in your area. Please contact Medicare.gov or 1-800-MEDICARE to get information on all of your options.

Let's see if you're missing out on Medicare savings.

We just need a few details.

Related Articles

What Is Medicare IRMAA?

What Is an IRMAA in Medicare?

How to Report Medicare Fraud

Medicare Fraud Examples & How to Report Abuse

How to Change Your Address with Medicare

Reporting a Change of Address to Medicare

Can I Get Medicare if I’ve Never Worked?

Can You Get Medicare if You've Never Worked?

Why Are Some Medicare Advantage Plans Free?

Why Are Some Medicare Advantage Plans Free? $0 Premium Plans Explained

What Is Medicare Assignment?

Am I Enrolled in Medicare?

When and How Do I Enroll?

When and How Do I Enroll in Medicare?

Medicare Frequently Asked Questions

Let’s see if you qualify for Medicare savings today!

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Article Search

Attorney search, search articles, find attorneys, what you pay your doctor under medicare depends on the doctor.

Medicare Part B recipients must satisfy an annual deductible. Once the deductible has been met, Medicare pays 80 percent of what Medicare considers a "reasonable charge" for the item or service. The beneficiary is responsible for the other 20 percent.

Local Elder Law Attorneys in Your City

Elder Law Attorney

Firm Name City, State

However, in most cases what Medicare calls a "reasonable charge" is less than what a doctor or other medical provider normally charges for a service. Whether a Medicare beneficiary must pay part of the difference between the Medicare-approved charge and the provider's normal charge depends on whether or not the provider has agreed to participate in the Medicare program.

If your doctor participates in Medicare, it means that the doctor "accepts assignment." In other words, the doctor agrees that the total charge for the covered service will be the amount approved by Medicare. Medicare then pays the provider 80 percent of its approved amount, after subtracting any part of your annual deductible that has not already been met. The provider then charges you the remaining 20 percent of the approved "reasonable" charge, plus any part of the deductible that has not been satisfied.

If your doctor does not accept assignment, the rules are different. Non-participating doctors can charge beneficiaries 20 percent of the approved amount plus up to an additional 15 percent more than the Medicare-approved amount. Non-participating doctors can also charge you the entire bill for the care upfront and request that you bill Medicare for reimbursement, while doctors who accept assignment cannot. Note that if you have Medigap plans F and G, they will cover the additional 15 percent charges (however, as of January 1, 2020, plan F is no longer sold).

Doctors can also choose to opt out of Medicare altogether. This means the doctor will not submit any claims to Medicare for reimbursement. If your doctor opts out of Medicare, you will be responsible for the full amount of your bill.

The payment system under Medicare Advantage is different because doctors contract with Advantage’s HMO or PPO plans and agree to the plan’s payment terms. As far as your payment responsibilities go, your plan will require specific copays and deductibles, which will vary plan by plan. Remember that at any time, Medicare Advantage plans can make changes to which doctors they cover, and doctors can choose to join or leave plans, so having a Medicare Advantage plan does not mean your doctor will always be covered. If your doctor leaves your plan’s network and you want to keep your doctor, you may need to switch plans to have your bills covered.

For more information about Medicare, click here .

Related Articles

Where should you put your retirement money.

There are as many opportunities to grow money as there are people with great ideas. ?Here?is a survey of types of investment...

Should You Sell Your Life Insurance Policy?

Older Americans with a life insurance policy that they no longer need have the option to sell the policy to investors. These...

Be on the Lookout for New Medicare Cards (and New Card-Related Scams)

The federal government is issuing new Medicare cards to all Medicare beneficiaries. To prevent fraud and fight identity theft...

Editor's Suggested Articles

Need more information? Subscribe to Elder Law Updates.

Medicaid 101

What medicaid covers.

In addition to nursing home care, Medicaid may cover home care and some care in an assisted living facility. Coverage in your state may depend on waivers of federal rules.

How to Qualify for Medicaid

To be eligible for Medicaid long-term care, recipients must have limited incomes and no more than $2,000 (in most states). Special rules apply for the home and other assets.

Medicaid’s Protections for Spouses

Spouses of Medicaid nursing home residents have special protections to keep them from becoming impoverished.

Medicaid Planning Strategies

Careful planning for potentially devastating long-term care costs can help protect your estate, whether for your spouse or for your children.

Estate Recovery: Can Medicaid Take My House After I’m Gone?

If steps aren't taken to protect the Medicaid recipient's house from the state’s attempts to recover benefits paid, the house may need to be sold.

Help Qualifying and Paying for Medicaid, Or Avoiding Nursing Home Care

There are ways to handle excess income or assets and still qualify for Medicaid long-term care, and programs that deliver care at home rather than in a nursing home.

Are Adult Children Responsible for Their Parents’ Care?

Most states have laws on the books making adult children responsible if their parents can't afford to take care of themselves.

Applying for Medicaid

Applying for Medicaid is a highly technical and complex process, and bad advice can actually make it more difficult to qualify for benefits.

Alternatives to Medicaid

Medicare's coverage of nursing home care is quite limited. For those who can afford it and who can qualify for coverage, long-term care insurance is the best alternative to Medicaid.

Most Recent Medicaid Articles

Elderlaw 101, estate planning.

Distinguish the key concepts in estate planning, including the will, the trust, probate, the power of attorney, and how to avoid estate taxes.

Grandchildren

Learn about grandparents’ visitation rights and how to avoid tax and public benefit issues when making gifts to grandchildren.

Guardianship/Conservatorship

Understand when and how a court appoints a guardian or conservator for an adult who becomes incapacitated, and how to avoid guardianship.

Health Care Decisions

We need to plan for the possibility that we will become unable to make our own medical decisions. This may take the form of a health care proxy, a medical directive, a living will, or a combination of these.

Long-Term Care Insurance

Understand the ins and outs of insurance to cover the high cost of nursing home care, including when to buy it, how much to buy, and which spouse should get the coverage.

Learn who qualifies for Medicare, what the program covers, all about Medicare Advantage, and how to supplement Medicare’s coverage.

Retirement Planning

We explain the five phases of retirement planning, the difference between a 401(k) and an IRA, types of investments, asset diversification, the required minimum distribution rules, and more.

Senior Living