Business Model Innovation: What It Is And Why It’s Important

Industry Advice Business

Amazon launched in 1995 as the “Earth’s biggest bookstore.” Fast-forward 22 years, and that “bookstore” is now a leader in cloud computing, can deliver groceries to your doorstep, and produces Emmy Award-winning television series.

The trillion-dollar organization has achieved this growth by being continuously willing to innovate upon its business model in order to address new challenges and pursue new opportunities.

“Amazon is amazing at new business model development,” says Greg Collier, an academic specialist in Northeastern’s D’Amore-McKim School of Business and the director of international programs for the Center for Entrepreneurship Education . “They look at themselves from a customer-defined perspective.”

That approach has helped Amazon scale because rather than rely on one revenue stream or customer segment, the company continuously asks “ What’s next?” This has allowed leadership to iterate on its business model accordingly, repeatedly experimenting with a process known as business model innovation .

As Amazon’s success demonstrates, this process can be incredibly exciting and impactful when you’re in control. However, when the need to innovate your business model is thrust upon you by outside forces, it can also feel quite disruptive.

For instance, today, the novel coronavirus is causing tremendous shifts in both the national and global economy. Many companies are being forced to innovate and adapt their business models in order to meet these challenges, or else risk falling victim to these drastic changes.

Read on to explore what business model innovation is and why it is so important for businesses to be capable of change.

What Is Business Model Innovation?

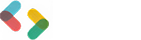

A business model is a document or strategy which outlines how a business or organization delivers value to its customers. In its simplest form, a business model provides information about an organization’s target market, that market’s need, and the role that the business’s products or services will play in meeting those needs.

Business model innovation , then, describes the process in which an organization adjusts its business model. Often, this innovation reflects a fundamental change in how a company delivers value to its customers, whether that’s through the development of new revenue streams or distribution channels.

Business Model Innovation Example: The Video Game Industry

Amazon is not the only company known for continuously innovating its business model.

The video game industry, for example, has gone through a number of periods of business model innovation in recent years, Collier says, by envisioning new ways in which to make money from customers.

When video games were first created, the consoles that housed them were expensive and bulky, which put them out of reach of most consumers. This gave rise to arcades, which would charge customers to essentially purchase credits needed to play the games.

As manufacturing processes and technological advancements made it easier to create smaller, more economical units, however, companies like Atari took advantage of the demand by selling units directly to the customer—a massive departure from what had been the accepted practice.

More recently, game developers have had to undergo rapid business model innovation in order to meet the evolving demands of customers—many of whom want to be able to play their games right on their smartphones.

Originally, many companies adjusted their practices in order to put their games in this format, charging consumers a subscription fee or making them pay to unlock new levels. Some of those businesses, however, were able to innovate their business models to make gameplay free to the end-user by incorporating in-app advertising or selling merchandise such as T-shirts and plush toys. This practice, they found, was able to dramatically increase their reach, while also bringing in substantial funds from consumers.

As Collier notes, “Competitors can easily change how they price.” That’s why it’s crucial for companies to consider how their products are being delivered.

The Importance of Business Model Innovation

Business model innovation allows a business to take advantage of changing customer demands and expectations. Were organizations like Amazon and Atari unable to innovate and shift their business models, it is very possible that they could have been displaced by newcomers who were better able to meet the customer need.

Business Model Innovation Example: Blockbuster vs. Netflix

Take Blockbuster, for example. The video rental chain faced a series of challenges, particularly when DVDs started out selling VHS tapes. DVDs took up less shelf space, had higher quality video and audio, and were also durable and thin enough to ship in the mail—which is where Netflix founders Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph spotted an opportunity.

The pair launched Netflix in 1997 as a DVD-by-mail business, enabling customers to rent movies without needing to leave their house. The added bonus was that Netflix could stock its product in distribution centers; it didn’t need to maintain inventory for more than 9,000 stores and pay the same operating costs Blockbuster did.

It took seven years for Blockbuster to start its own DVD-by-mail service. By that point, Netflix had a competitive advantage and its sights set on launching a streaming service, forcing Blockbuster to play a game of constant catch-up. In early 2014, all remaining Blockbuster stores shut down .

“Blockbuster’s problem was really distribution,” Collier says. “DVDs inspired Netflix, and the technology change then drove a change in the business model. And those changes are a lot harder to copy. You’re eliminating key pieces in the way a business operates.”

For this reason, it’s often harder for legacy brands to innovate. Those companies are already delivering a product or service that their customers expect, making it more difficult for teams to strategize around what’s next or think through how the industry could be disrupted.

“Disruption is usually then done by new entrants,” Collier says. “Established organizations are already making money.”

Business Model Innovation Example: Kodak

By focusing solely on existing revenue streams, however, organizations could face a fate similar to Kodak. The company once accounted for 90 percent of film and 85 percent of camera sales . Although impressive, that was just the problem: Kodak viewed itself as a film and chemical business, so when the company’s own engineer, Steven Sasson, created the first digital camera, Kodak ignored the business opportunity. Executives were nervous the shift toward digital would make Kodak’s existing products irrelevant, and impact its main revenue stream. The company lost its first-mover advantage and, in turn, was later forced to file for bankruptcy.

Business Model Innovation Example: Mars

Mars started as a candy business, bringing popular brands like Milky Way, M&M’s, and Snickers to market. Over time, however, Mars started expanding into pet food and, eventually, began acquiring pet hospitals. In early 2017, Mars purchased VCA —a company that owns roughly 800 animal hospitals—for $7.7 billion. further solidifying its hold on the pet market.

“Mars looked at its core capabilities, which is what corporate entrepreneurship is all about,” Collier says. “It’s about looking at your products and services in new ways. Leverage something you’re really good at and apply it in new ways to new products.”

The Role of Lean Innovation

Implementing lean innovation is advantageous. Lean innovation enables teams to develop, prototype, and validate new business models faster and with fewer resources by capturing customer feedback early and often.

Collier recommends companies start with a hypothesis: “I have this new customer and here’s the problem I’m solving for him or her,” for example. From there, employees can start to test those key assumptions using different ideation and marketing techniques to gather customer insights, such as surveying. That customer feedback can then be leveraged to develop a pilot or prototype that can be used to measure the team’s assumptions. If the first idea doesn’t work, companies can more easily pivot and test a new hypothesis.

“This is a big part people forget to do,” Collier says. “Lean design allows us to rapidly test and experiment perpetually until we come to a model that works.”

Pursuing Innovation in Business

In addition to business model innovation, companies could also pursue other types of innovation , including:

- Product Innovation : This describes the development of a new product, as well as an improvement in the performance or features of an existing product. Apple’s continued iteration of its iPhone is an example of this.

- Process Innovation : Process innovation is the implementation of new or improved production and delivery methods in an effort to increase a company’s production levels and reduce costs. One of the most notable examples of this is when Ford Motor Company introduced the first moving assembly line, which brought the assembly time for a single vehicle down from 12 hours to roughly 90 minutes .

The choice to pursue product, process, or business model innovation will largely depend on the company’s customer and industry. Executives running a product firm, for example, need to constantly think about how they plan to innovate their product.

“When the innovation starts to slow down, that’s when firms should be thinking of and looking at next-generation capabilities,” Collier suggests.

If a company is trying to choose where to focus its efforts, however, the business model is a recommended place to start.

“Business model innovation is often more impactful on a business than product innovations,” Collier says. “It’s Amazon’s business model that’s disrupting the market.”

Innovation Doesn’t Always Come Easy

While the examples above demonstrate that innovation is an important part of running a business, it’s also clear that it doesn’t always come easy. Corporate history is littered with examples of companies that were unable to innovate when they needed to the most.

Luckily, there are steps that business owners, entrepreneurs, and professionals can take to become better suited to pursuing innovation when an opportunity appears.

Learning the fundamentals of how businesses and industries change will prove to be instrumental in enabling you to carry out your own initiatives. Assess and dissect the successes and failures of businesses in the past, and learn how to apply these valuable lessons to your own challenges.

This article was originally published in December 2017. It has since been updated for accuracy and relevance.

Subscribe below to receive future content from the Graduate Programs Blog.

About shayna joubert, related articles.

Master’s in Project Management or an MBA: What’s the Difference?

5 Practices of Exemplary Leaders

Why You Should Get an MBA

Did you know.

The annual median starting salary for MBA graduates is $115,000. (GMAC, 2018)

Master of Business Administration

Emerge as a leader within your organization.

Most Popular:

Tips for taking online classes: 8 strategies for success, public health careers: what can you do with an mph, 7 international business careers that are in high demand, edd vs. phd in education: what’s the difference, 7 must-have skills for data analysts, in-demand biotechnology careers shaping our future, the benefits of online learning: 8 advantages of online degrees, how to write a statement of purpose for graduate school, the best of our graduate blog—right to your inbox.

Stay up to date on our latest posts and university events. Plus receive relevant career tips and grad school advice.

By providing us with your email, you agree to the terms of our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Keep Reading:

Should I Go To Grad School: 4 Questions to Consider

Grad School or Work? How to Balance Both

7 Networking Tips for Graduate Students

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

Innovation in Business: What It Is & Why It’s Important

- 08 Mar 2022

Today’s competitive landscape heavily relies on innovation. Business leaders must constantly look for new ways to innovate because you can't solve many problems with old solutions.

Innovation is critical across all industries; however, it's important to avoid using it as a buzzword and instead take time to thoroughly understand the innovation process.

Here's an overview of innovation in business, why it's important, and how you can encourage it in the workplace.

What Is Innovation?

Innovation and creativity are often used synonymously. While similar, they're not the same. Using creativity in business is important because it fosters unique ideas . This novelty is a key component of innovation.

For an idea to be innovative, it must also be useful. Creative ideas don't always lead to innovations because they don't necessarily produce viable solutions to problems.

Simply put: Innovation is a product, service, business model, or strategy that's both novel and useful. Innovations don't have to be major breakthroughs in technology or new business models; they can be as simple as upgrades to a company's customer service or features added to an existing product.

Access your free e-book today.

Types of Innovation

Innovation in business can be grouped into two categories : sustaining and disruptive.

- Sustaining innovation: Sustaining innovation enhances an organization's processes and technologies to improve its product line for an existing customer base. It's typically pursued by incumbent businesses that want to stay atop their market.

- Disruptive innovation: Disruptive innovation occurs when smaller companies challenge larger businesses. It can be classified into groups depending on the markets those businesses compete in. Low-end disruption refers to companies entering and claiming a segment at the bottom of an existing market, while new-market disruption denotes companies creating an additional market segment to serve a customer base the existing market doesn't reach.

The most successful companies incorporate both types of innovation into their business strategies. While maintaining an existing position in the market is important, pursuing growth is essential to being competitive. It also helps protect a business against other companies affecting its standing.

Learn about the differences between sustaining and disruptive innovation in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

The Importance of Innovation

Unforeseen challenges are inevitable in business. Innovation can help you stay ahead of the curve and grow your company in the process. Here are three reasons innovation is crucial for your business:

- It allows adaptability: The recent COVID-19 pandemic disrupted business on a monumental scale. Routine operations were rendered obsolete over the course of a few months. Many businesses still sustain negative results from this world shift because they’ve stuck to the status quo. Innovation is often necessary for companies to adapt and overcome the challenges of change.

- It fosters growth: Stagnation can be extremely detrimental to your business. Achieving organizational and economic growth through innovation is key to staying afloat in today’s highly competitive world.

- It separates businesses from their competition: Most industries are populated with multiple competitors offering similar products or services. Innovation can distinguish your business from others.

Innovation & Design Thinking

Several tools encourage innovation in the workplace. For example, when a problem’s cause is difficult to pinpoint, you can turn to approaches like creative problem-solving . One of the best approaches to innovation is adopting a design thinking mentality.

Design thinking is a solutions-based, human-centric mindset. It's a practical way to strategize and design using insights from observations and research.

Four Phases of Innovation

Innovation's requirements for novelty and usefulness call for navigating between concrete and abstract thinking. Introducing structure to innovation can guide this process.

In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar teaches design thinking principles using a four-phase innovation framework : clarify, ideate, develop, and implement.

- Clarify: The first stage of the process is clarifying a problem. This involves conducting research to empathize with your target audience. The goal is to identify their key pain points and frame the problem in a way that allows you to solve it.

- Ideate: The ideation stage involves generating ideas to solve the problem identified during research. Ideation challenges assumptions and overcomes biases to produce innovative ideas.

- Develop: The development stage involves exploring solutions generated during ideation. It emphasizes rapid prototyping to answer questions about a solution's practicality and effectiveness.

- Implement: The final stage of the process is implementation. This stage involves communicating your developed idea to stakeholders to encourage its adoption.

Human-Centered Design

Innovation requires considering user needs. Design thinking promotes empathy by fostering human-centered design , which addresses explicit pain points and latent needs identified during innovation’s clarification stage.

There are three characteristics of human-centered design:

- Desirability: For a product or service to succeed, people must want it. Prosperous innovations are attractive to consumers and meet their needs.

- Feasibility: Innovative ideas won't go anywhere unless you have the resources to pursue them. You must consider whether ideas are possible given technological, economic, or regulatory barriers.

- Viability: Even if a design is desirable and feasible, it also needs to be sustainable. You must consistently produce or deliver designs over extended periods for them to be viable.

Consider these characteristics when problem-solving, as each is necessary for successful innovation.

The Operational and Innovative Worlds

Creativity and idea generation are vital to innovation, but you may encounter situations in which pursuing an idea isn't feasible. Such scenarios represent a conflict between the innovative and operational worlds.

The Operational World

The operational world reflects an organization's routine processes and procedures. Metrics and results are prioritized, and creativity isn't encouraged to the extent required for innovation. Endeavors that disrupt routine—such as risk-taking—are typically discouraged.

The Innovative World

The innovative world encourages creativity and experimentation. This side of business allows for open-endedly exploring ideas but tends to neglect the functional side.

Both worlds are necessary for innovation, as creativity must be grounded in reality. You should strive to balance them to produce human-centered solutions. Design thinking strikes this balance by guiding you between the concrete and abstract.

Learning the Ropes of Innovation

Innovation is easier said than done. It often requires you to collaborate with others, overcome resistance from stakeholders, and invest valuable time and resources into generating solutions. It can also be highly discouraging because many ideas generated during ideation may not go anywhere. But the end result can make the difference between your organization's success or failure.

The good news is that innovation can be learned. If you're interested in more effectively innovating, consider taking an online innovation course. Receiving practical guidance can increase your skills and teach you how to approach problem-solving with a human-centered mentality.

Eager to learn more about innovation? Explore Design Thinking and Innovation ,one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you're not sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

Business Model Innovation – The What, Why, and How

In the last couple of decades, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the popularity of business model innovation – and for good reason.

Technology has made it easier than ever to adopt a wide variety of novel business models effectively. At the same time, increased pace of innovation and global competition has made differentiation more important than ever .

In addition, with the havoc caused by COVID-19, we're already seeing that even though many businesses are battling for survival, there are also winners. Those winners usually possess very robust business models, which further outlines the importance of business model innovation in times like this.

In this article, we’ll look into what exactly it is, why it is so important, as well as how one can make it happen with the help of quite a few examples.

Table of contents

- What is business model innovation?

- Why is it important?

- Examples of innovative business models

- How to create business model innovation

The Definition of Business Model Innovation

One of the common mistakes people make when it comes to business models is that they simply look at them very narrowly as just the pricing model for their products and services.

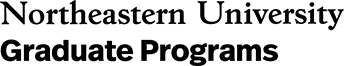

While it certainly is a key part of the business model, the term is actually defined as the way an “organization creates, delivers and captures value”.

Business model is the way an organization creates, delivers and captures value.

Successful business models thus take a very holistic approach by integrating these different aspects of the business into a well-organized and thought out system.

Business model innovation, then is simply a novel way to put these pieces together to hopefully create a system that produces more value for both customers and the organization itself.

Why Is Business Model Innovation So Important?

Without realizing it, a business that doesn’t explicitly focus on their business model as a whole often ends up compromising their initial strengths.

For example, many businesses start to gradually drift apart from the true needs of their customers unless they specifically focus on avoiding that. Some might focus too heavily on just optimizing the delivery of their products and sacrifice their ability to create value.

There are many reasons for these phenomena. Perhaps management focuses too heavily on what the competition is doing, or perhaps there’s pressure from shareholders to optimize for short-term profit.

Regardless, there are countless industries where the true interests of the customers and those of the service providers have become opposite.

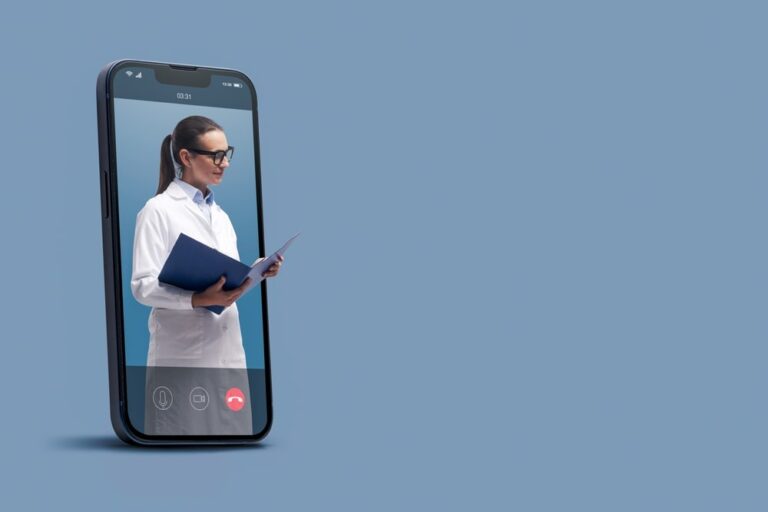

The healthcare sector is a prime example of this: a private hospital has strong incentives for wanting you to be chronically sick so that you’d keep coming back regularly and they could charge you for each visit. You naturally want the hospital to take good care of you, but ideally, you’d just want to stay healthy and not have to go to the doctors’ in the first place.

Business model innovation is simply put probably the most important tool for building a business that creates maximal value for all stakeholders: customers, shareholders, employees, and the society at large.

This obviously leads to a wide variety of benefits :

- Increased value creation will lead to increased growth , even for otherwise stagnant businesses

- As business model innovation often requires new operating models and is thus often very difficult for established competitors to copy

- …which can lead to an extend period of competitive advantage

- The right kind of business model also helps overcome objections to sales and create positive brand recognition

- As mentioned, some business models can make the business much more robust towards market cycles and unexpected “black swan” events, such as the recent COVID-19 crisis

To conclude, business model innovation is a flexible tool for building a great business irrespective of the industry. That’s why you’ll see most of the fastest growing and most disruptive businesses including business model innovation as a key part of their “innovation mix” .

Examples of Business Model Innovation

Before we get into the part where we look at how to actually do business model innovation, let’s first take a look at a few examples of business model innovation to get a better picture of what it can look like in practice.

Subscription models

Subscription models are a powerful way to turn one-off purchases to a more predictable, and over time larger, stream of revenue while ensuring that the customer keeps getting value and is also able to better afford higher-end services due to the purchase occurring over time.

Subscription models are equally applicable for both B2B and B2C businesses.

On the B2B side, Software as a Service (SaaS) products like Microsoft Office 365 and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) offerings like Amazon Web Services are great examples of this approach.

Subscription businesses tend to have quite distinct, straightforward value chains but do require some capabilities that many product businesses might not be very strong at, such as delivery and customer support.

Freemium is a portmanteau of the words free and premium. It refers to business models where a company offers a free version of their product, typically with certain limitations, in order to attract users and eventually upgrade them to paying “premium customers”.

For businesses with a good product, high gross margins and high customer acquisition costs, such as most content and software businesses, this can be a very powerful model, especially in crowded markets.

The Freemium model is quite common for B2B software products that tend to have bottom-up adoption like Slack and Zoom , but also for many B2C services, such as Spotify and Apple iCloud .

The downside is that without strong value creation, freemium models might make it difficult for the business to capture enough value.

In essence, platforms are places that aggregate and/or facilitate supply and demand meeting. Platforms are characterized by their distributed approach to creating value.

In practice that means that they’re basically either matchmakers or marketplaces, but still come in many shapes and forms. They typically earn money by either taking a commission of the transactions, or by charging the supply side for the value-added services they provide.

These days you mostly hear the term being used for digital platforms, but the business model far predates online services. Shopping malls and classified ads in newspapers are just a couple of examples of traditional platform business models.

The challenge with platform business models is that it's often really hard to get platforms off the ground and achieve a critical mass where they become self-sustaining.

Direct-to-Consumer (D2C)

Both consumer and industrial goods manufacturers have traditionally relied on a, often complicated, supply chain of wholesalers and retailers to sell their goods.

Before the Internet, that allowed them to have a much larger geographical reach and thus benefit from economies of scale.

However, with the rise of e-commerce, we’ve seen a rapid rise in the popularity of the Direct-to-Consumer business model in many categories of consumer goods.

This approach provides the manufacturer with higher margins as the middlemen are removed, gives them much more control over the brand, customer experience and relationship, and provides them with more data, that is also of higher quality, on demand and customer preferences.

Ads, affiliates & sponsorships

For as long as there have been content and communication channels, there’s been advertising in one form or the other, and that hasn’t changed recently.

With the rise of the Internet, smartphones, and the democratization of content creation, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in content, which has made the traditional business model of monetizing content with advertising and sponsorships harder since there’s so much more competition for people’s attention.

For the right kind of audiences, typically in very specific niches, it can still be a viable business model in itself and for other businesses with a sizeable following, it can become an additional secondary source of income.

For example, while Spotify generates the vast majority of its revenue and profits from its subscribers, advertising revenue does provide the company with a solid secondary revenue stream that can be used for investing in growth.

Loss leaders & add-on services

While there’s nothing new in selling professional services, we’ve seen many interesting novel business models built around them.

A great example of this is the business model of open source software companies like WordPress, Red Hat and Elastic . These companies have built very popular open source software products that they let other companies use completely for free.

When you give away great software for free, it tends to become extremely widely adopted, as has certainly been the case for the aforementioned three products. Without the open source model, these companies would never have been able to reach the kind of market share they’ve actually managed to get to.

Once their products have been adopted at scale, the open source companies are obviously well positioned to either sell professional services or offer hosting services for this large base of users.

The same basic logic of giving something away for free, or at a loss, and then sell additional products or services to that wider customer base is also known as a loss leader strategy. It has been widely adopted across many industries, such as retail where stores might offer a real bargain for certain attractive products to lure in more foot traffic.

In general, selling maintenance contracts and other add-on services has become a ubiquitous business model especially in B2B, but also for more expensive B2C products, such as cars.

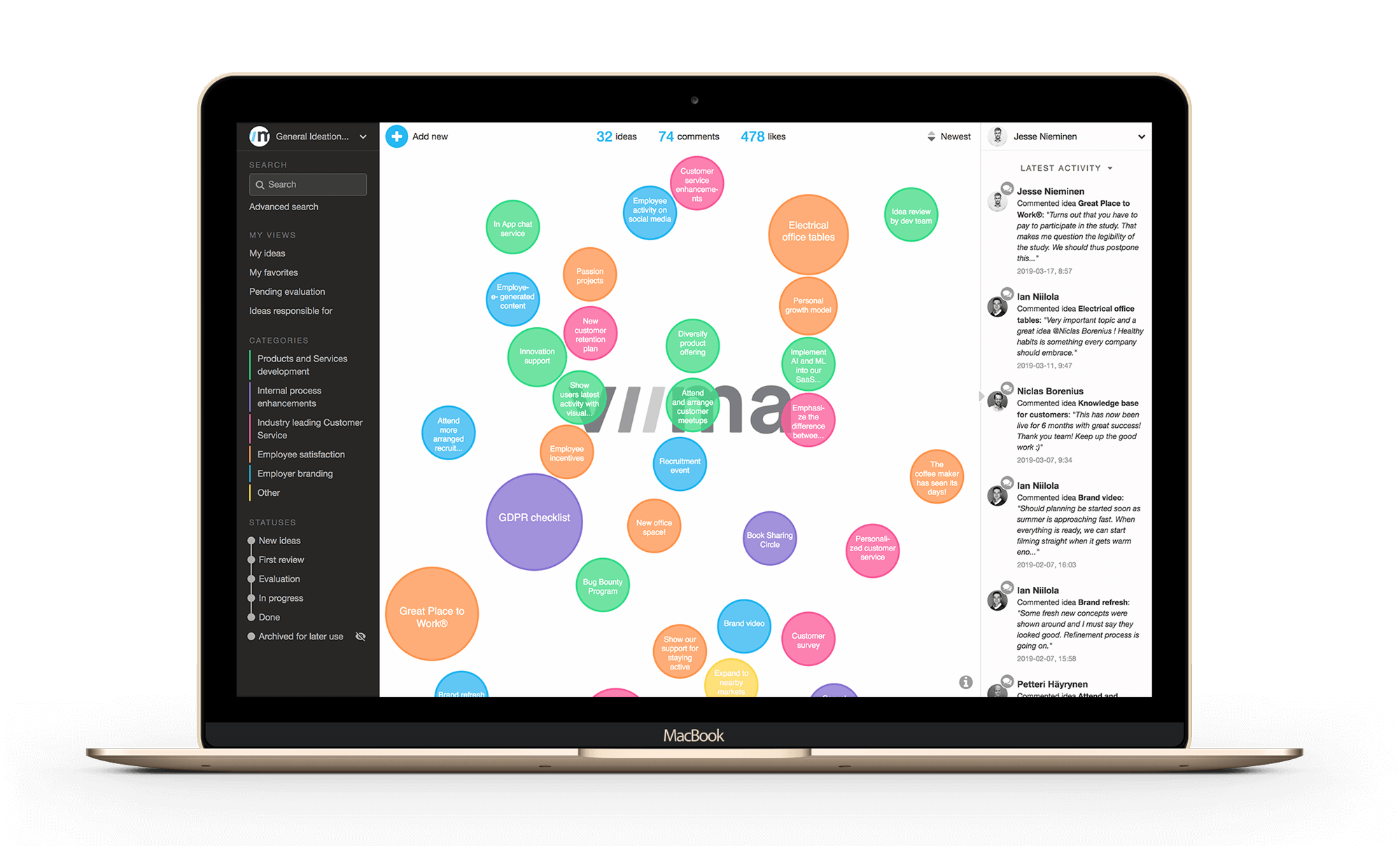

Razor & blades

Interestingly, just like with so many other stories of innovation , the story of the business model being invented by Gillette when he first created disposable razor blades isn’t true . In reality, it was invented by the competitors that entered the market once Gillette’s patents expired.

Since then, the model has been adopted by many companies selling goods like film cameras, printers and Nespresso capsules .

While the aforementioned examples cover some of the innovative business model patterns that we’ve seen gain popularity in the recent years, there are many others as well: franchising, auctions, micropayments, pay-what-you-want , the list goes on.

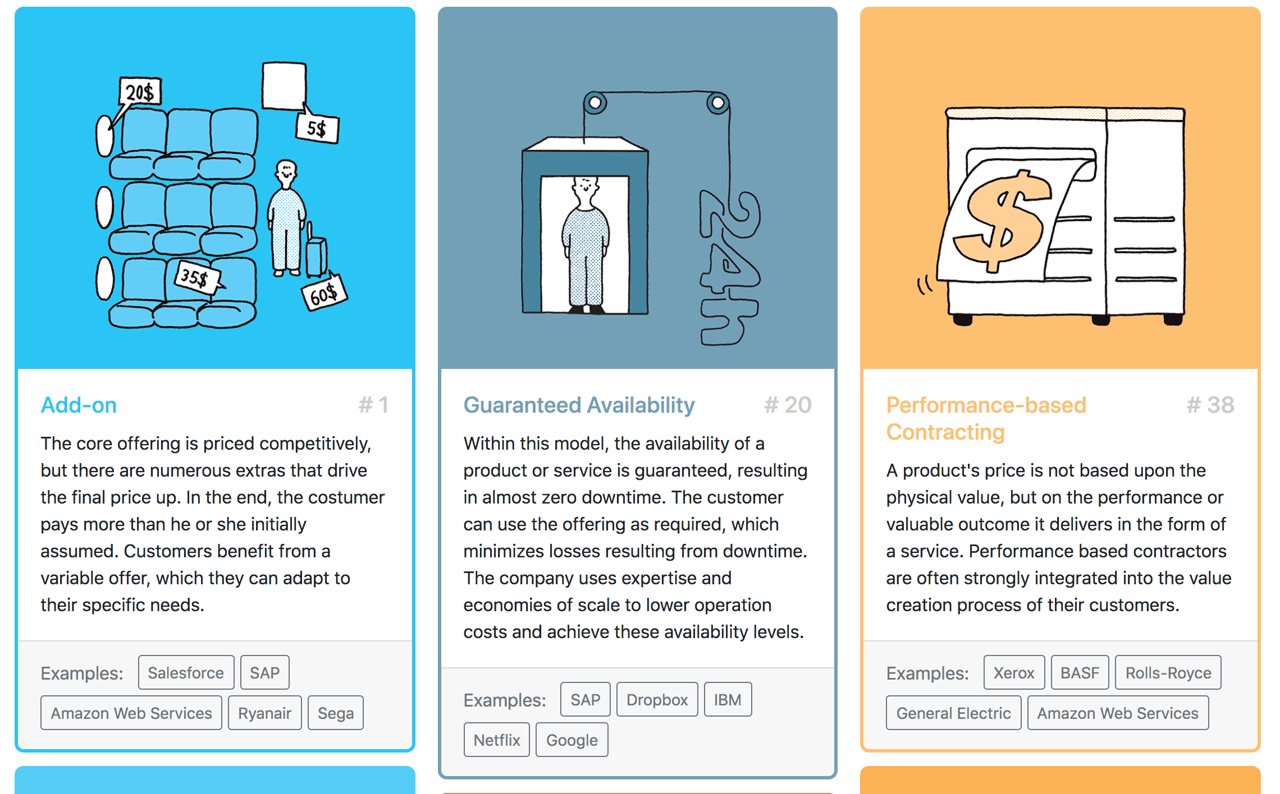

The Business Model Navigator is a very convenient and easy-to-use tool for browsing these patterns.

There are literally countless ways you can combine the different business models together with different product and service offerings to try to maximize the value created by your products and services.

Another example of this is Peloton . They sell high-end exercise equipment like bikes and treadmills for home use, and couple that with a subscription service that provides exercise programs, virtual classes and many other engaging features to accompany the bike. According to the company, even though their devices are quite expensive, they aim to sell them at break-even and then make money with the subscriptions.

This obviously means that to make a profit, they need to ensure that their customers stay motivated and keep exercising, which is what ultimately keeps them fit and creates value for everyone involved.

The leadership of the company may not have managed the business optimally, which has led to severe financial challenges after the lockdowns ended but that doesn't take anything away from the fundamental strength of the business model. Still, this is a great reminder that while a strong business model is a great foundation, there's more to running a successful business than that.

How Do You Create Business Model Innovation?

The examples above have hopefully provided you with some inspiration on what kind of new business models might be possible.

However, if you’re looking to create a business model innovation for your business, here are a few tips that can help you find the right model for you.

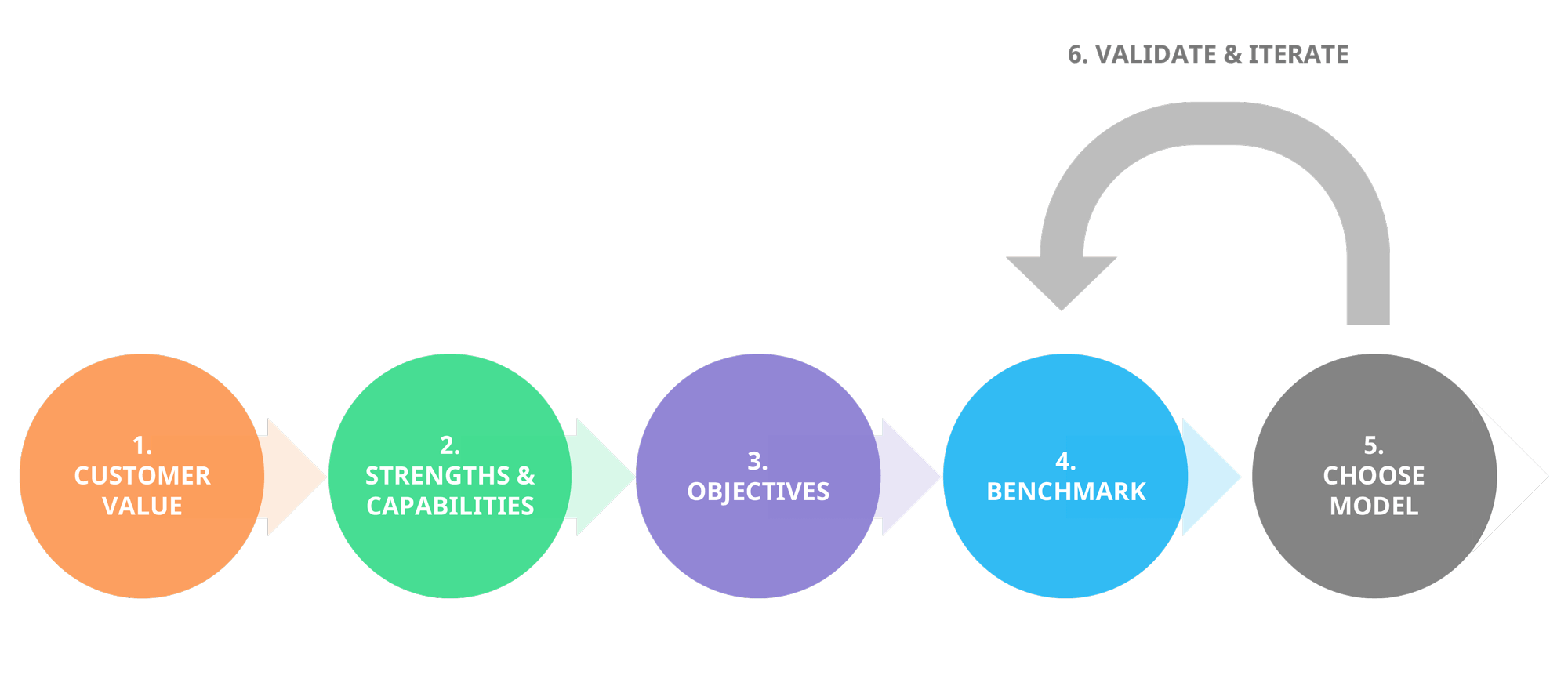

1. Start with customer value

The first step, as with every innovation, is to start with customer value.

- What is “the job” that the customer wants done?

- What are the obstacles that currently prevent them from getting the job done?

- What are your customers now using to get the same job done, or why are they putting off doing it?

- How do they know if the job is done or not?

Once you have a clear answer to these questions, you’ll already be well on your way.

2. What are your strengths?

Every business should obviously build their business models to benefit from and take advantage of their own strengths and unique capabilities.

For example, if you have plenty of data and when and how your products break, you’re obviously the party that’s best positioned to provide novel maintenance services, or maybe even insurance for these products.

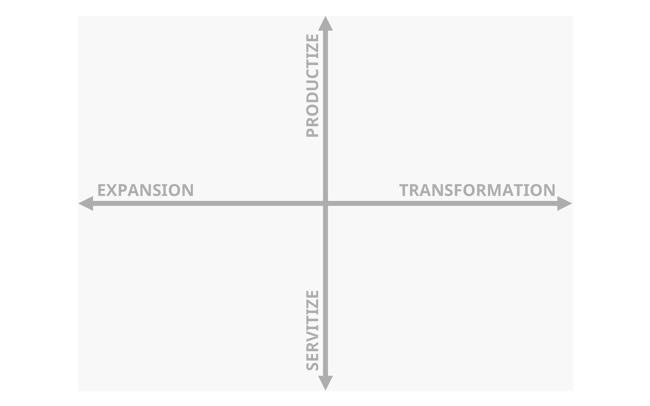

3. What are your objectives for the business?

Some businesses want to focus on profitability, others want to grow as much as possible, and some simply want to do as good of a job as possible for their customers.

These goals ultimately matter a lot when you’re trying to design the perfect business model as different business models are better suited for different kinds of goals.

Some companies might simply want to find ways to expand their current business with minor tweaks to their model where others might be looking for bigger, more transformative kind of changes.

For example, if you’re looking to maximize growth, you should choose a business model where the customer gets almost all of the value and keep costs down to maximize adoption.

In the short term, you will take a financial hit compared to some of the other models, but this can make the business unattractive for competitors, thus providing you with a big competitive advantage in the long run. The Freemium and open source models are obvious examples of this approach.

4. Look for patterns by benchmarking leading innovators

As mentioned, the best business models are tailored to the needs of your customers, the characteristics of your industry, as well as your business objectives.

Thus, whenever you’re looking to design a new business model, it’s usually a good idea to benchmark what the most innovative companies in the world are currently doing.

You should obviously know where your competition is but remember that the point of business model innovation is to find a way that allows you to provide much more value than they do, either at a lower price or with better margins, maybe even both, so don’t just copy them!

Thus, the best benchmarks are often from very different industries.

As mentioned, the Business Model Navigator is a great resource for this benchmarking process. It’s a website that features 55 different business model patterns that you can try to apply for your own business, including most of the examples we presented above.

5. Put it all together to identify the right model

The next step is to combine your findings from steps 1, 2, 3 and 4. Find ways where you can create as much value for your customers as possible, that uses your strengths, and allows you to capture a fair share of that revenue as determined by your business objectives.

This is obviously the creative part, so it might take some time and effort to get this right, but remember that you can always look at the examples we’ve mentioned above.

On the other hand, if you are selling products, you probably want to turn one off sales into a more predictable stream of revenue, as well as grow the amount of business you get from each customer. In this case, the solution is to either sell add-on services that help your customers make the most out of your products, or to look for ways that you could use to turn those one-off product sales into subscriptions with some service components.

6. Validate and iterate

As with any other kind of innovation, you typically don’t get business model innovation right the first time around either.

In the end, the only way to know if it works is by testing the business model in practice.

The challenging part with many business model innovations are that they often require drastic changes to your current operating model, which you obviously shouldn’t do unless you have strong evidence for the transition being worth it.

Thus, it’s crucially important that you validate the assumptions that you’ve done in the steps leading to this point, starting from your most critical assumption , and pilot that with a small subset of your customers.

Validating the business model at smaller scale obviously saves costs and resources, but has another key advantage: speed. Learning and moving fast is essential for innovation success.

Learning and moving fast is essential for innovation success.

It can sometimes take quite a few of those tweaks to figure out the right business model, even if your products are brilliant, which is why you need to learn, iterate, and move fast when your window of opportunity is still open.

To conclude, business model innovation is a powerful, yet still very underappreciated tool.

It’s one of those topics that is quite straightforward to get the hang of, and can thus help make a difference quite soon.

If you’re not seeing the business results you think you should be getting with your products and services, or you’re looking to take significant market share from entrenched competitors, give business model innovation a try.

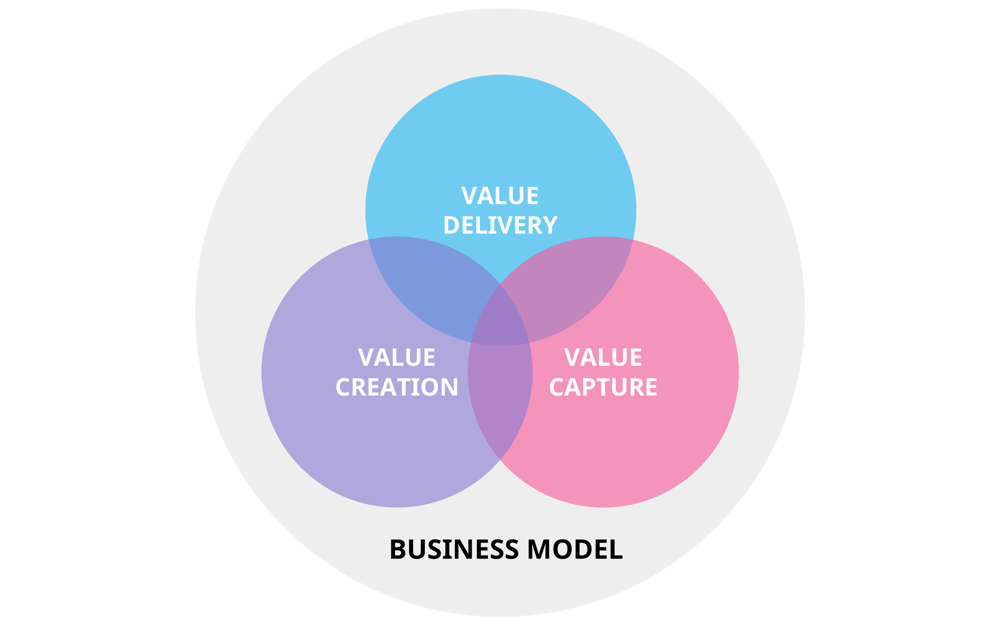

If you want a powerful tool to get started with your innovation process, you might want to try Viima ! It takes just minutes and is completely free.

And, consider joining the thousands of innovators already following our latest articles!

Related articles

Social Innovation - the What, Why and How

The Importance of Innovation – What Does it Mean for Businesses and our Society?

5 Simple Steps for Finding the Right Business Idea

A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Knowledge at Wharton Podcast

Business model innovation matters more than ever, february 15, 2021 • 33 min listen.

A new book by Wharton’s Raphael (“Raffi”) Amit and Christoph Zott from IESE Business School guides business leaders on how to craft a winning business model innovation strategy for the long game of disruption.

Wharton’s Raphael Amit and Christoph Zott from IESE Business School discuss their new book, Business Model Innovation Strategy.

The coronavirus pandemic has been a roller coaster for business managers. Some are cresting high, others are in freefall, and many more are simply trying to hang on until the nightmare ride comes to a stop. Amid the panic, there are valuable lessons for leaders who can take a deep breath and step back. Wharton management professor Raffi Amit and Christoph Zott , an entrepreneurship professor at the University of Navarra’s IESE Business School in Spain, have written a new book to guide businesses through the internal and external shocks caused by the pandemic and other disruptions. Business Model Innovation Strategy: Transformational Concepts and Tools for Entrepreneurial Leaders draws on 20 years of research and practice to help businesses embrace change by building a strategy that will make them more resilient and responsive to the marketplace. Amit and Zott joined Knowledge at Wharton to talk about the book. (Listen to the podcast at the top of this page.)

An edited transcript of the conversation follows.

Knowledge at Wharton: Before we dive into the book, could you give me a little background on your collaboration?

Raffi Amit: We’ve known each other since the mid-1990s, when we met at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Both Chris and I are strategy and entrepreneurship scholars with a very pragmatic orientation and very rich practical experiences. We observed in the mid- and late-1990s that there were all these e-businesses that were formed, and they are enormously valuable. We observed companies like eBay, for example, which was founded in 1995 and went public in 1998. It doesn’t have a product. The cost of goods sold is zero. Yet eBay is worth billions of dollars. Take Netflix, another example of a company that was founded in 1997 and went public in 2002. There’s really nothing new about its product. You could have rented CDs at Blockbuster, yet Netflix innovated in the way you rent a CD. Initially, it was mail order, and now it’s streaming. By innovating the way you rent a CD, it drove Blockbuster out of business.

This allowed Chris and me to realize that there is a new form of innovation that is distinct from product innovation, that is distinct from process innovation, and which does not require mountains of R&D expenses and years of research. This new form of innovation centered on the way companies do business. Namely, their business model. We published over two dozen papers together, and we decided to write a book about business model innovation.

Christoph Zott: The real answer is that because our last names fit so well together — Amit and Zott. We’re the team that looks at something and tries to find the answer from A to Z. If you go even beyond the internet and the focus on business models, what brought us together was our keen interest in entrepreneurship and everything that has to do with value creation. Raffi and I share a passion for that subject. We really want to understand how value is created, how people create something from nothing. This is this magical formula that is typically attributed to entrepreneurs. They’re able to turn ideas into something tangible. [They build] companies that provide employment to people. They create products that customers want to buy.

The relevant issue that we were observing, especially in the second part of the 1990s, was that there were a bunch of companies that were created very fast and made it to IPO really fast. Netscape, Yahoo, eBay. We asked ourselves, “What’s special about these businesses? Is there anything new here?” That led us to the realization that what these companies were doing and were really good at had nothing to do with our preconceived notions of products or services. But it was in how they did business, which we then called the business model.

“Everything that we have learned in business school for the past decades is still true. But the business model offers a new avenue for value creation.” –Christoph Zott

There was something fundamentally new going on, and it didn’t really have to do with the digitization of business. We saw that digitization was an enabler for firms to go about business in a new way, in a different way. This got us off on our work on business models and business model innovation. We wrote our first paper together in 2000, and it was published in the Strategic Management Journal . It’s still considered one of the seminal pieces on business models. It wasn’t that the business model was a brand-new idea for managers. But for academia, it was a new idea. We were interested in developing this idea and exploring it further because we thought it was a very, very rich idea. If you have companies that, within a matter of a few years, become worth billions of dollars, there must be something really to it. We’ve been at it now for a long time, and the book represents a summary of the insights that we and our colleagues have found and researched over the past 20 years.

Knowledge at Wharton: Let’s talk about what business model innovation is. In this book, you help define it by telling us what it is not. You wrote that, “Modifying an activity by making it faster, cheaper, or higher quality is not a business model innovation.” That statement seems to eliminate the traditional avenues of improvement that managers usually take. What should they be doing instead?

Zott: I’d like to address this question in two ways. Yes, we do say in our book what a business model is not. And we do this deliberately, because we think it helps people understand better what a business model is in the first place. In general, there is a lot of confusion about what a business model really is. If one person says A and another person thinks B, it’s very hard to think that they have a real conversation around this topic. So, we thought it would be very important first to define the concept clearly.

The second thing is that we don’t believe that other ways of creating value have become less important and that the business model eliminates these traditional avenues. In contrast, the business model adds to these traditional avenues of improvement for business managers. It complements them. Everything that we have learned in business school for the past decades is still true. But the business model offers a new avenue for value creation.

Knowledge at Wharton: Professor Amit, what is the framework for business model innovation?

Amit: Now we know what the business model is not — it’s not the product, it’s not the firm, it’s not all-encompassing, and it’s not the same thing as a business plan. The way we think about the business model is as a system of interdependent and interconnected activities that are designed to capture market needs, or perceived market needs, and create value for all the stakeholders. It’s a holistic concept that requires the manager to take a step back and apply system-wide or system-level thinking.

There are really four dimensions in a business model. First, what are the activities that need to be carried out as part of this business model? Second, how are these activities sequenced or connected to each other? Third, who carries out each of the activities? And fourth, why is this business model creating value for all stakeholders, and why does this business model enable the focal firm that innovates the business model to capture some of this value?

The basic idea is, as Chris pointed out, if you just change and make the product a little bit better — you add a feature, for example, or make it work faster — it doesn’t change the system of activities. So, when we talk about business model innovation, it refers to a business model that is new to the industry in which the firm competes. And business model innovation strategy, which is the title of the book, refers to the design of a new activity system, namely, the design of a new business model. It refers to the processes by which that new system of activities is created and the implementation of the system within the context of the firm. And very, very importantly, [it includes] the ongoing adaptation of that business model to a changing ecosystem or environment within which the firm competes.

Zott: I just wanted to repeat this very important observation — that a business model is not all-encompassing. If it were all-encompassing, how would it then be different from a firm or an organization? We’re talking about the business model of a company, of an organization. This is distinct. In terms of the business model, it’s the activity system that we would like to highlight as the crucial underlying conceptual backbone.

We could think of Apple, which is a very well-known example because Apple does both. Apple is brilliant with product innovation and design. They have innovated many gadgets that are household items today, which has made them one of the most valuable companies on the planet. The iPhone is one of the latest examples of that.

“When we talk about business model innovation, it refers to a business model that is new to the industry in which the firm competes.” –Raphael Amit

But they are also a very powerful business model innovator. With the introduction of their app store and iTunes and all of those innovations, what they have done is added a distribution platform to their hardware business, which makes their hardware business more valuable. They benefit from the sale of the gadgets, but they also benefit from the sale of the content that is played on these gadgets, so they benefit twice. There is a mutually reinforcing relationship here between their product innovation and their business model innovation.

Knowledge at Wharton: In the book, you stress the importance of adopting a business model mindset. That usually refers to startups and thinking like an entrepreneur, but it’s a little bit more than that for you. So, what is a business model mindset and why is it important?

Zott: You mentioned entrepreneurial mindset. That is one type of mindset that’s certainly very helpful. But when we talk about business model mindset, we refer to what Raffi has mentioned a little earlier as system-level thinking and holistic thinking. Entrepreneurs also need to think at the system level and holistically because they need to think about the entire business architecture. They need to think about all business functions.

It’s the same thing with the business model [mindset]. In the business model mindset, you need to be able to take a step back, and this sometimes is very difficult for managers because they’re focused. They work in organizations, within certain functions, so they’re good at one thing. They’re good at strategy, they’re good at marketing. They may work in sales, or they may work in finance. But they rarely have this opportunity to take a step back and rethink the entire construction, the entire architecture of the business for which they’re working. How does it all hang together? How are all these activities connected to each other? That is what we believe requires a specific mindset — this ability to see the forest and not just the trees. That’s the first requirement of a business model mindset. To be able to jump the level of analysis from a focus on activities or individual activities or products, to the system level.

Amit: Think about a car manufacturer executive’s reaction to the entry of Tesla into the automotive market. The first thing they are thinking about is, “Well, maybe what we should do is expand our product portfolio and have an electric car or a hybrid car,” because the focus is on the technology of the product.

But Elon Musk — who has a background at Wharton — already adopted a much broader perspective on his firm’s innovation strategy, taking Apple as an inspiration not only for promoting distinctive technology and slick product design, but also imitating and incorporating other key aspects of the Apple business model. For example, they have their own stores rather than having franchises distribute their car. They have total control of the entire process, from the design to manufacturing and the sales. General Motors doesn’t have that. Mercedes Benz doesn’t have that. Chrysler doesn’t have that. Ford doesn’t. They use third-party franchisees that do the sales, so they don’t have total control of the interaction with the end customer. But Tesla does. And that feedback allows Tesla to continuously innovate its offer and be ahead of the competition. It’s not focused just on the car. It’s a much more holistic perspective on doing business.

Knowledge at Wharton: That’s a really great example because we just found out that Elon Musk has topped the list of richest people in the world. Clearly, he’s doing something right. We can take some lessons from his business model mindset.

“You need to be able to take a step back, and this sometimes is very difficult for managers because they’re focused.” –Christoph Zott

Zott: The Tesla example is a brilliant one in order to highlight the two traps into which managers often fall. The first trap is the level of analysis trap, which is when managers continue to focus on what they thought was the important thing to focus on. Like, for example, the product. This is very clear in the car industry. If you look at traditional car firms, and you ask managers in those car firms what’s really important, many of them will continue to talk about the car and the engine and elements of the design of the car, and so on and so forth. They’re completely focused and concentrated on the car as a product. Whereas people like Elon Musk and others in the e-mobility industry know that the car as a product is one vision. The other vision would be the car as a software platform, or even as a service. And that would be a different type of level of analysis. To get from one to the other is extremely, extremely difficult. If you have worked all your life on products, and all of a sudden somebody comes along and says, “It’s not about the product anymore. It’s about how you do business,” that’s a difficult one to grasp.

That ties into the second trap, which is the familiarity trap. You’re used to working within a particular activity system, within a particular company. You’re used to working within a car manufacturer that has things set up in a certain way, that has a production line, but then outsources many things to suppliers and works with dealerships. This is your familiar reference point. To cast that aside and say, “Wow, maybe we should do things very differently. Maybe we should not outsource so many things and should do them internally,” or vice versa — that’s not so easy, either. People are familiar with certain things, and have a hard time grasping the new and the need for a new way of doing things. The need for a new business model. They also are very much focused on a certain level of analysis, especially at the product level, and then have a hard time understanding why they should be talking about activities. “Why should activities matter? Isn’t it the product that’s important here?” We say both are important, but you need to make the move and the jump from one to the other. And that’s, I think, a mindset issue.

Knowledge at Wharton: The coronavirus pandemic has upended business in a very short period of time. But if we go back through history, there are a number of moments that have redefined business. We can think of World War II, the oil crisis in the 1970s, the development of the internet. Is this pandemic any different? Are there new lessons to be learned here?

Zott: I think that the COVID crisis is acting as an accelerator in many respects. Does it highlight very new issues? I’m not so sure. I think it brings to the forefront issues that were already there, but it makes them even more salient. It’s an accelerator in many ways, for example when we talk about education and digital ways of delivering education. In our universities, both at the Wharton School and at IESE Business School, we’ve seen a change that we would not have believed possible a year ago. I think of it more as an accelerator than as something that brings about fundamentally new desires and fundamentally new developments. Although we cannot exclude that.

Knowledge at Wharton: Dr. Amit, would you agree?

Amit: Let’s just put things a little bit in perspective. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a severe, multifaceted global crisis — both a health crisis and an economic crisis. The shocks to the economy were both on the demand side as well as on the supply side. A catastrophic pandemic such as COVID-19 is very likely to alter the preferences, habits, and risk attitudes of consumers, in part because of the long stays at home and the social distancing measures that were applied. What seems very likely is that many companies — both large and small, both private and public, both for-profit and not-for-profit — will be prompted to reimagine themselves, to reinvent themselves, in order to survive and prosper in the future.

The way they engage with their customers might change dramatically. For the last almost year, we didn’t go to malls. We didn’t go shopping. We did everything online. If you are a mall owner, you will ask yourself, “Will consumers come back to malls? Will they need the mall? Will they need to go when they are so used to shopping online today?”

There are profound behavioral changes that might occur as a result of this pandemic. Companies need to look at themselves and say, “Should we find new ways to interact with our partners, with our customers?” Therefore, “Do we need to design a new business model?” There is no doubt that the pandemic has prompted companies to reimagine and redesign their business models. I think that we don’t really know how the new normal will evolve. That’s work in progress, right? There are so many things that are happening, both politically, socially, and otherwise, and there is a record level of uncertainty as a result. That, for sure, will affect how companies will decide to engage with their stakeholders.

“There is no doubt that the pandemic has prompted companies to reimagine and redesign their business models.” –Raphael Amit

I think that the breadth and depth of the changes that the pandemic has brought about, as well as the speed at which those things have occurred, will result in substantial business model innovation. Our book provides guidance to executives on how to go about doing this, because many are not that familiar with that process and with that type of thinking.

As we work with companies around the world, we see that they’re struggling. If you’re a mall, you’re trying to hold onto the retailers that lease space from you. But maybe they should think totally differently about the usage of the space, not just running after retailers and convincing them to continue to pay the rent. Maybe they should engage in different uses of the space. Maybe do some entertainment, maybe do some other things that would bring people back into malls, not just for shopping but for other activities that complement shopping.

Knowledge at Wharton: If readers take one thing away from your book, what do you want that lesson to be?

Amit: Pay attention to your business model strategy. It has become a strategic imperative and a key strategic choice that managers and entrepreneurs need to make. The business model requires an ongoing, innovative adaptation to the changing external environment. Make sure that your organization accepts change and has a business model innovation mindset to enable it to continue and prosper in the future.

Zott: I think the most important message to entrepreneurs and managers out there — and it’s a positive message — is that business model innovation has become a new form of innovation. It’s best conceived of as how to do business and how to do business in new ways. It’s centered on the firm’s activity system, and it represents a new form of value creation.

Think of it as a new type of innovation. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist. You don’t have to be an engineer. You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in anything in order to come up with a new business model idea. It’s very democratic, and it’s an equalizer. You can come up with new ideas, creative new ways of doing business, and build a fantastic new company around that. But as Raffi pointed out, in order to do this systematically and in a disciplined manner, you have to have a strategy for it, especially if you’re working for a large company. This is not just for start-up entrepreneurs, but it’s particularly important for established companies who need to reinvent themselves. And then COVID-19 presents us with a rationale for why it’s important to think about reinventing ourselves.

More From Knowledge at Wharton

How Financial Frictions Hinder Innovation

How Early Adopters of Gen AI Are Gaining Efficiencies

How Is AI Affecting Innovation Management?

Looking for more insights.

Sign up to stay informed about our latest article releases.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Four Paths to Business Model Innovation

- Karan Girotra

- Serguei Netessine

The secret to success lies in who makes what decisions when and why.

Reprint: R1407H

Drawing on the idea that any business model is essentially a set of key decisions that collectively determine how a business earns its revenue, incurs its costs, and manages its risks, the authors view innovations to the model as changes to those decisions: What mix of products or services should you offer? When should you make your key decisions? Who are your best decision makers? and Why do key decision makers choose as they do? In this article they present a framework to help managers take business model innovation to the level of a reliable and improvable discipline. Companies can use the framework to make their innovation processes more systematic and open so that business model reinvention becomes a continual, inclusive process rather than a series of isolated, internally focused events.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

Business model innovation is typically an ad hoc process, lacking any framework for exploring opportunities. As a result, many companies miss out on inexpensive ways to radically improve their profitability and productivity.

The Solution

Drawing on the idea that a business model reflects a set of decisions, the authors frame innovation in terms of deciding what products or services to offer, when to make decisions, who should make them, and why the decision makers choose as they do.

Traditional call centers hire a staff to supply services as needed from a place of work, incurring significant up-front costs and risks. LiveOps created a new model by revising the order of decisions: It employs agents as calls come in by routing the calls to home-based freelancers who have signaled their availability.

Business model innovation is a wonderful thing. At its simplest, it demands neither new technologies nor the creation of brand-new markets: It’s about delivering existing products that are produced by existing technologies to existing markets. And because it often involves changes invisible to the outside world, it can bring advantages that are hard to copy.

- KG Karan Girotra is the Charles H. Dyson Family Professor of Management at Cornell Tech and the Johnson College of Business at Cornell University, and a coauthor, with Serguei Netessine, of The Risk-Driven Business Model: Four Questions That Will Define Your Company (HBR Press, 2014). Follow him on Twitter: @Girotrak

- Serguei Netessine is the vice dean for global initiatives and the Dhirubhai Ambani Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and a coauthor, with Karan Girotra, of The Risk-Driven Business Model: Four Questions That Will Define Your Company (HBR Press, 2014). Follow him on Twitter: @snetesin

Partner Center

- November 7, 2023

- Digital Experience , Digital Strategy , Digital Transformation

What is Business Model Innovation?

Business Model Innovation (BMI) is more than just a set of incremental changes; it represents a holistic and radical transformation of how a company creates and delivers value to its customers. Most importantly, from the shareholder’s view, BMI represents how it generates revenue or profits through the value proposition.

While some may be well-versed in Business Model Innovation, others may wonder, “What exactly is Business Model Innovation?” In this guide, we define the concept, explain its importance, provide examples, discuss strategies and challenges, and look to the future of Business Model Innovation.

Business Model Innovation Defined

Business Model Innovation is a comprehensive approach that determines the core components of a company’s strategy, including its target audience, value proposition, revenue streams, and cost structure.

Business Model Innovation involves:

- Rethinking an organization’s existing business models.

- Challenging conventional wisdom.

- Exploring novel approaches to problem-solving.

A core component of Business Model Innovation that most organizations overlook is the Operating Model. The Operating Model is an expansion on Michael Porter’s Value Chain first described in his book Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance . In simple terms, a value chain is a series of steps or systems a business uses to create value for its customers. The Operating Model builds upon the concept of the value chain to include all of the capabilities that support the value chain (illustrated as chevrons – see below). Capabilities are visual constructs that describe the people who perform business processes supported by various technologies within an organization. The Operating Model makes the activities and processes that an organization conducts explicit, and in doing so, allows the organization to easily identify, evaluate, and correct inefficient, ineffective, or missing capabilities that are crucial in executing the organization’s strategy.

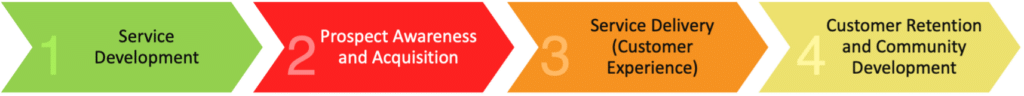

Using the Operating Model for BMI focuses on the business processes within the organization that produce customer value. Broadly, these processes fall into three or four Process Families:

- Service Development

- Prospect Awareness and Acquisition

- Service Delivery ( Customer Experience )

- Customer Retention and Community Development

Importance of Business Model Innovation

To stay relevant, businesses always need to evolve, but they can choose to do so proactively and lead the way or reactively and struggle to keep up. For companies that want to remain relevant , Business Model Innovation allows them to leverage changing customer demands and expectations to drive business growth. Far too many have failed to heed market dynamics at their peril ( for example did you know that Eastman Kodak, a pioneer in the photography industry, played a vital role in the development of digital imaging technology and yet was unable to capitalize on its investment)..

Examples of Business Model Innovation

Many things we enjoy and rely upon exist due to Business Model Innovation. Just take Netflix, for example. The company began as a DVD rental service, transformed into a cutting-edge subscription-based streaming platform that completely disrupted the industry, and is now creating a buzz by randomly giving away DVDs to customers. Another example is Airbnb. It disrupted the hotel industry with innovative peer-to-peer accommodation arrangements and tourism experiences. These companies boldly shook up the status quo and became staples in our lives.

Strategies in Business Model Innovation

The fastest way to build new business models, innovate, and transform culture along the way is with a Strategy-to-Execution process that includes the following tenets from the Transformation Manifesto :

- A complete and total leadership focus on running, improving, and transforming the business simultaneously is required.

- A strategy-to-execution process is cultivated and includes many contributors. Without this, running and improving the business will fail, and transformation will be impossible.

- The strategy-to-execution process must be driven by vision and inspiration. The best type of transformation is driven by value and is not a response to market forces.

- A fundamental rethinking of the business operating model must be embraced. Forget hierarchy; it’s all about capability development and deployment.

- There must be a deliberate shift away from command and control models to new networked models of work.

- Adoption of new capability-based behaviors, metrics, and responsibilities must be widespread.

- Transformation requires new techniques – capability modeling, business value analysis, heat mapping, investment road mapping, and enterprise architecture.

- Higher velocity must be created by using the agile or scrum approach for business and IT.

- Inspired stumbling forward must be encouraged and rewarded.

- Transformation must start with CEO and C-suite leadership and center on Talent Management. Leadership must demand more from HR and IT to leverage talent for better collaboration and to create the conditions for innovation and growth.

Challenges in Business Model Innovation

Despite their best efforts, many organizations seem to be incapable of Business Model Innovation. The most common root cause of this struggle is that businesses make the mistake of confusing the Org-chart, which describes what employees do for the organization, with the Operating Model, which describes what an organization does to deliver its value proposition to its customers.

While it can be helpful to direct attention to employee contributions, doing so in this context distracts from what is at the core of business transformation. Viewing business model transformation through the lens of the Org-chart encourages parochial thinking and reinforces departmental silos. Org-chart thinking typically results in a retrospective inward gaze rather than a forward-looking outward scan to discover new market opportunities, enhance customer experiences, and improve operational efficiencies.

Using the Operating Model for BMI focuses on the customer-value-producing business processes within the organization. Viewing the organization through this lens not only positions the organization for Business Model Innovation but more importantly, it often reveals gaping competitive holes, leaving the organization highly susceptible to digital disruptors – new or existing competitors who have leveraged new/emerging technology to leapfrog existing incumbents.

Future of Business Model Innovation

The Future of Business Model Innovation is for you to define. What will your business innovate?

In his book, The Fourth Industrial Revolution , Klaus Schwab stated, “The question for all industries and companies, without exception, is no longer am I going to be disrupted but when is disruption coming, what form will it take, and how will it affect me and my organization?” At Accelare, we’ve created a quick, 4-minute assessment that helps organizations evaluate their operating model to determine their digital disruption exposure.

This assessment looks at four specific domains that are critical to BMI:

- Value Innovation/Customer Experience – The organization’s ability to design and deliver a meaningful customer experience at a lower cost.

- Operational Innovation/Agility – The organization’s ability to re-align human capital, business processes, and current technology to anticipate and capitalize on market shifts.

- Organizational Engagement – The organization’s ability to promote employee experiences and build alignment through communication and active participation.

- Financial Health – The organization’s ability to allocate capital to create value for stakeholders.

Upon completion, we will send out a free, personalized report that compares your organization against a baseline and offers advice on improving your digital disruption resilience and BMI efforts.

To jumpstart your Business Model Innovation journey, take our Digital Disruption Assessment .

More Insights

Key Factors in Digital Disruption: People and Technology

Digital disruption is transforming industries at an unprecedented pace, influencing not just market dynamics but also the internal operations of organizations. While technology undoubtedly plays

5 Recent Examples of Digital Disruption and Their Impact

In recent years, digital disruption has become a central theme in the evolving business landscape. This phenomenon occurs when emerging technologies and new business models

What is an Operating Model in Business?

In the complex and ever-evolving business landscape, understanding the intricacies of an operating model is crucial for any organization aiming to achieve strategic goals and

Is your organization at risk of digital disruption?

Take our 4-minute, 12 question disruption assessment

Business Model Innovation

- First Online: 01 October 2020

Cite this chapter

- Bernd W. Wirtz 2

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Business and Economics ((STBE))

8454 Accesses

1 Citations

- The original version of this chapter was revised. A correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48017-2_22

Business model innovation has received more attention in recent years than nearly all of the other subareas of business model management. In this respect, there is a great interest in literature and practice regarding the conditions, structure and implementation of innovations on the business model level. Since business model innovation is rather abstract compared to product or process innovation, knowledge of the business model concept as well as classic innovation management is necessary in order to better understand it.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

See also for the following chapter Wirtz ( 2010a , 2018a , 2019a ).

Afuah, A. (2004). Business models – A strategic management approach . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Google Scholar

Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e-business. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (6), 493–520.

Article Google Scholar

Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2012). Creating value through business model innovation. Sloan Management Review, 53 (3), 41–49.

Bucherer, E., Eisert, U., & Gassmann, O. (2012). Towards systematic business model innovation: Lessons from product innovation management. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21 (2), 183–198.

Budde, F., Elliot, B. R., Farha, G., & Palmer, C. R. (2000). The chemistry of knowledge. McKinsey Quarterly, 4 , 99–107.

Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Ricart, J. E. (2010). From strategy to business models and to tactics. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 195–215.

Chesbrough, H. (2006). Open business models . Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy & Leadership, 35 (6), 12–17.

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 354–363.

Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11 (3), 529–555.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (Eds.). (2006). Open innovation. Researching a new paradigm . Oxford: Oxford University.

Cooper, R. G. (1994). Third-generation new product processes. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11 (1), 3–14.

Deloitte. (2002). Business model innovation . New York: Deloitte.

Demil, B., & Lecocq, X. (2010). Business model evolution: In search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 227–246.

Denicolai, S., Ramirez, M., & Tidd, J. (2014). Creating and capturing value from external knowledge: The moderating role of knowledge intensity. R&D Management, 44 (3), 248–264.

Eppler, M. J., & Hoffmann, F. (2012). Does method matter? An experiment on collaborative business model idea generation in teams. Innovations, 14 (3), 388–403.

Gambardella, A., & McGahan, A. M. (2010). Business model innovation: General purpose technologies and their implications for industry structures. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 262–271.

Goffin, K., & Mitchell, R. (2010). Innovation management: Strategy and implementation using the pentathlon framework (2nd ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Günzel, F., & Holm, A. B. (2013). One size does not fit all: Understanding the front-end and back-end of business model innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 17 (1), 1–34.