Office of Undergraduate Research

- Office of Undergraduate Research FAQ's

- URSA Engage

- Resources for Students

- Resources for Faculty

- Engaging in Research

- Spring Poster Symposium (SPS)

- Ecampus SPS Videos

- Earn Money by Participating in Research Studies

- Transcript Notation

- Student Publications

How to take Research Notes

How to take research notes.

Your research notebook is an important piece of information useful for future projects and presentations. Maintaining organized and legible notes allows your research notebook to be a valuable resource to you and your research group. It allows others and yourself to replicate experiments, and it also serves as a useful troubleshooting tool. Besides it being an important part of the research process, taking detailed notes of your research will help you stay organized and allow you to easily review your work.

Here are some common reasons to maintain organized notes:

- Keeps a record of your goals and thoughts during your research experiments.

- Keeps a record of what worked and what didn't in your research experiments.

- Enables others to use your notes as a guide for similar procedures and techniques.

- A helpful tool to reference when writing a paper, submitting a proposal, or giving a presentation.

- Assists you in answering experimental questions.

- Useful to efficiently share experimental approaches, data, and results with others.

Before taking notes:

- Ask your research professor what note-taking method they recommend or prefer.

- Consider what type of media you'll be using to take notes.

- Once you have decided on how you'll be taking notes, be sure to keep all of your notes in one place to remain organized.

- Plan on taking notes regularly (meetings, important dates, procedures, journal/manuscript revisions, etc.).

- This is useful when applying to programs or internships that ask about your research experience.

Note Taking Tips:

Taking notes by hand:.

- Research notebooks don’t belong to you so make sure your notes are legible for others.

- Use post-it notes or tabs to flag important sections.

- Start sorting your notes early so that you don't become backed up and disorganized.

- Only write with a pen as pencils aren’t permanent & sharpies can bleed through.

- Make it a habit to write in your notebook and not directly on sticky notes or paper towels. Rewriting notes can waste time and sometimes lead to inaccurate data or results.

Taking Notes Electronically

- Make sure your device is charged and backed up to store data.

- Invest in note-taking apps or E-Ink tablets

- Create shortcuts to your folders so you have easier access

- Create outlines.

- Keep your notes short and legible.

Note Taking Tips Continued:

Things to avoid.

- Avoid using pencils or markers that may bleed through.

- Avoid erasing entries. Instead, draw a straight line through any mistakes and write the date next to the crossed-out information.

- Avoid writing in cursive.

- Avoid delaying your entries so you don’t fall behind and forget information.

Formatting Tips

- Use bullet points to condense your notes to make them simpler to access or color-code them.

- Tracking your failures and mistakes can improve your work in the future.

- If possible, take notes as you’re experimenting or make time at the end of each workday to get it done.

- Record the date at the start of every day, including all dates spent on research.

Types of media to use when taking notes:

Traditional paper notebook.

- Pros: Able to take quick notes, convenient access to notes, cheaper option

- Cons: Requires a table of contents or tabs as it is not easily searchable, can get damaged easily, needs to be scanned if making a digital copy

Electronic notebook

- Apple Notes

- Pros: Easily searchable, note-taking apps available, easy to edit & customize

- Cons: Can be difficult to find notes if they are unorganized, not as easy to take quick notes, can be a more expensive option

Combination of both

Contact info.

618 Kerr Administration Building Corvallis, OR 97331

541-737-5105

13.5 Research Process: Making Notes, Synthesizing Information, and Keeping a Research Log

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Employ the methods and technologies commonly used for research and communication within various fields.

- Practice and apply strategies such as interpretation, synthesis, response, and critique to compose texts that integrate the writer’s ideas with those from appropriate sources.

- Analyze and make informed decisions about intellectual property based on the concepts that motivate them.

- Apply citation conventions systematically.

As you conduct research, you will work with a range of “texts” in various forms, including sources and documents from online databases as well as images, audio, and video files from the Internet. You may also work with archival materials and with transcribed and analyzed primary data. Additionally, you will be taking notes and recording quotations from secondary sources as you find materials that shape your understanding of your topic and, at the same time, provide you with facts and perspectives. You also may download articles as PDFs that you then annotate. Like many other students, you may find it challenging to keep so much material organized, accessible, and easy to work with while you write a major research paper. As it does for many of those students, a research log for your ideas and sources will help you keep track of the scope, purpose, and possibilities of any research project.

A research log is essentially a journal in which you collect information, ask questions, and monitor the results. Even if you are completing the annotated bibliography for Writing Process: Informing and Analyzing , keeping a research log is an effective organizational tool. Like Lily Tran’s research log entry, most entries have three parts: a part for notes on secondary sources, a part for connections to the thesis or main points, and a part for your own notes or questions. Record source notes by date, and allow room to add cross-references to other entries.

Summary of Assignment: Research Log

Your assignment is to create a research log similar to the student model. You will use it for the argumentative research project assigned in Writing Process: Integrating Research to record all secondary source information: your notes, complete publication data, relation to thesis, and other information as indicated in the right-hand column of the sample entry.

Another Lens. A somewhat different approach to maintaining a research log is to customize it to your needs or preferences. You can apply shading or color coding to headers, rows, and/or columns in the three-column format (for colors and shading). Or you can add columns to accommodate more information, analysis, synthesis, or commentary, formatting them as you wish. Consider adding a column for questions only or one for connections to other sources. Finally, consider a different visual format , such as one without columns. Another possibility is to record some of your comments and questions so that you have an aural rather than a written record of these.

Writing Center

At this point, or at any other point during the research and writing process, you may find that your school’s writing center can provide extensive assistance. If you are unfamiliar with the writing center, now is a good time to pay your first visit. Writing centers provide free peer tutoring for all types and phases of writing. Discussing your research with a trained writing center tutor can help you clarify, analyze, and connect ideas as well as provide feedback on works in progress.

Quick Launch: Beginning Questions

You may begin your research log with some open pages in which you freewrite, exploring answers to the following questions. Although you generally would do this at the beginning, it is a process to which you likely will return as you find more information about your topic and as your focus changes, as it may during the course of your research.

- What information have I found so far?

- What do I still need to find?

- Where am I most likely to find it?

These are beginning questions. Like Lily Tran, however, you will come across general questions or issues that a quick note or freewrite may help you resolve. The key to this section is to revisit it regularly. Written answers to these and other self-generated questions in your log clarify your tasks as you go along, helping you articulate ideas and examine supporting evidence critically. As you move further into the process, consider answering the following questions in your freewrite:

- What evidence looks as though it best supports my thesis?

- What evidence challenges my working thesis?

- How is my thesis changing from where it started?

Creating the Research Log

As you gather source material for your argumentative research paper, keep in mind that the research is intended to support original thinking. That is, you are not writing an informational report in which you simply supply facts to readers. Instead, you are writing to support a thesis that shows original thinking, and you are collecting and incorporating research into your paper to support that thinking. Therefore, a research log, whether digital or handwritten, is a great way to keep track of your thinking as well as your notes and bibliographic information.

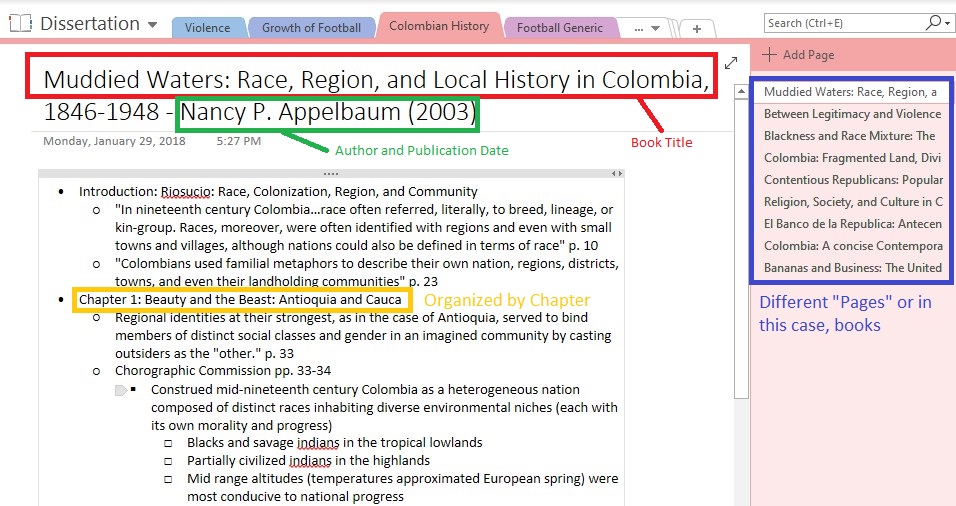

In the model below, Lily Tran records the correct MLA bibliographic citation for the source. Then, she records a note and includes the in-text citation here to avoid having to retrieve this information later. Perhaps most important, Tran records why she noted this information—how it supports her thesis: The human race must turn to sustainable food systems that provide healthy diets with minimal environmental impact, starting now . Finally, she makes a note to herself about an additional visual to include in the final paper to reinforce the point regarding the current pressure on food systems. And she connects the information to other information she finds, thus cross-referencing and establishing a possible synthesis. Use a format similar to that in Table 13.4 to begin your own research log.

Types of Research Notes

Taking good notes will make the research process easier by enabling you to locate and remember sources and use them effectively. While some research projects requiring only a few sources may seem easily tracked, research projects requiring more than a few sources are more effectively managed when you take good bibliographic and informational notes. As you gather evidence for your argumentative research paper, follow the descriptions and the electronic model to record your notes. You can combine these with your research log, or you can use the research log for secondary sources and your own note-taking system for primary sources if a division of this kind is helpful. Either way, be sure to include all necessary information.

Bibliographic Notes

These identify the source you are using. When you locate a useful source, record the information necessary to find that source again. It is important to do this as you find each source, even before taking notes from it. If you create bibliographic notes as you go along, then you can easily arrange them in alphabetical order later to prepare the reference list required at the end of formal academic papers. If your instructor requires you to use MLA formatting for your essay, be sure to record the following information:

- Title of source

- Title of container (larger work in which source is included)

- Other contributors

- Publication date

When using MLA style with online sources, also record the following information:

- Date of original publication

- Date of access

- DOI (A DOI, or digital object identifier, is a series of digits and letters that leads to the location of an online source. Articles in journals are often assigned DOIs to ensure that the source can be located, even if the URL changes. If your source is listed with a DOI, use that instead of a URL.)

It is important to understand which documentation style your instructor will require you to use. Check the Handbook for MLA Documentation and Format and APA Documentation and Format styles . In addition, you can check the style guide information provided by the Purdue Online Writing Lab .

Informational Notes

These notes record the relevant information found in your sources. When writing your essay, you will work from these notes, so be sure they contain all the information you need from every source you intend to use. Also try to focus your notes on your research question so that their relevance is clear when you read them later. To avoid confusion, work with separate entries for each piece of information recorded. At the top of each entry, identify the source through brief bibliographic identification (author and title), and note the page numbers on which the information appears. Also helpful is to add personal notes, including ideas for possible use of the information or cross-references to other information. As noted in Writing Process: Integrating Research , you will be using a variety of formats when borrowing from sources. Below is a quick review of these formats in terms of note-taking processes. By clarifying whether you are quoting directly, paraphrasing, or summarizing during these stages, you can record information accurately and thus take steps to avoid plagiarism.

Direct Quotations, Paraphrases, and Summaries

A direct quotation is an exact duplication of the author’s words as they appear in the original source. In your notes, put quotation marks around direct quotations so that you remember these words are the author’s, not yours. One advantage of copying exact quotations is that it allows you to decide later whether to include a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. ln general, though, use direct quotations only when the author’s words are particularly lively or persuasive.

A paraphrase is a restatement of the author’s words in your own words. Paraphrase to simplify or clarify the original author’s point. In your notes, use paraphrases when you need to record details but not exact words.

A summary is a brief condensation or distillation of the main point and most important details of the original source. Write a summary in your own words, with facts and ideas accurately represented. A summary is useful when specific details in the source are unimportant or irrelevant to your research question. You may find you can summarize several paragraphs or even an entire article or chapter in just a few sentences without losing useful information. It is a good idea to note when your entry contains a summary to remind you later that it omits detailed information. See Writing Process Integrating Research for more detailed information and examples of quotations, paraphrases, and summaries and when to use them.

Other Systems for Organizing Research Logs and Digital Note-Taking

Students often become frustrated and at times overwhelmed by the quantity of materials to be managed in the research process. If this is your first time working with both primary and secondary sources, finding ways to keep all of the information in one place and well organized is essential.

Because gathering primary evidence may be a relatively new practice, this section is designed to help you navigate the process. As mentioned earlier, information gathered in fieldwork is not cataloged, organized, indexed, or shelved for your convenience. Obtaining it requires diligence, energy, and planning. Online resources can assist you with keeping a research log. Your college library may have subscriptions to tools such as Todoist or EndNote. Consult with a librarian to find out whether you have access to any of these. If not, use something like the template shown in Figure 13.8 , or another like it, as a template for creating your own research notes and organizational tool. You will need to have a record of all field research data as well as the research log for all secondary sources.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/13-5-research-process-making-notes-synthesizing-information-and-keeping-a-research-log

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Utility Menu

- ARC Scheduler

- Student Employment

- Note-taking

Think about how you take notes during class. Do you use a specific system? Do you feel that system is working for you? What could be improved? How might taking notes during a lecture, section, or seminar be different online versus in the classroom?

Adjust how you take notes during synchronous vs. asynchronous learning (slightly) .

First, let’s distinguish between synchronous and asynchronous instruction. Synchronous classes are live with the instructor and students together, and asynchronous instruction is material recorded by the professor for viewing by students at another time. Sometimes asynchronous instruction may include a recording of a live Zoom session with the instructor and students.

With this distinction in mind, here are some tips on how to take notes during both types of instruction:

Taking notes during live classes (synchronous instruction).

Taking notes when watching recorded classes (asynchronous instruction)., check in with yourself., if available, annotate lecture slides during lecture., consider writing notes by hand., review your notes., write down questions..

Below are some common and effective note-taking techniques:

Cornell Notes

If you are looking for help with using some of the tips and techniques described above, come to the ARC’s note-taking workshop, offered several times every semester.

Register for ARC Workshops

Accordion style.

- Assessing Your Understanding

- Building Your Academic Support System

- Common Class Norms

- Effective Learning Practices

- First-Year Students

- How to Prepare for Class

- Interacting with Instructors

- Know and Honor Your Priorities

- Memory and Attention

- Minimizing Zoom Fatigue

- Office Hours

- Perfectionism

- Scheduling Time

- Senior Theses

- Study Groups

- Tackling STEM Courses

- Test Anxiety

How to Do Research: A Step-By-Step Guide: 4a. Take Notes

- Get Started

- 1a. Select a Topic

- 1b. Develop Research Questions

- 1c. Identify Keywords

- 1d. Find Background Information

- 1e. Refine a Topic

- 2a. Search Strategies

- 2d. Articles

- 2e. Videos & Images

- 2f. Databases

- 2g. Websites

- 2h. Grey Literature

- 2i. Open Access Materials

- 3a. Evaluate Sources

- 3b. Primary vs. Secondary

- 3c. Types of Periodicals

- 4a. Take Notes

- 4b. Outline the Paper

- 4c. Incorporate Source Material

- 5a. Avoid Plagiarism

- 5b. Zotero & MyBib

- 5c. MLA Formatting

- 5d. MLA Citation Examples

- 5e. APA Formatting

- 5f. APA Citation Examples

- 5g. Annotated Bibliographies

Note Taking in Bibliographic Management Tools

We encourage students to use bibliographic citation management tools (such as Zotero, EasyBib and RefWorks) to keep track of their research citations. Each service includes a note-taking function. Find more information about citation management tools here . Whether or not you're using one of these, the tips below will help you.

Tips for Taking Notes Electronically

- Try using a bibliographic citation management tool to keep track of your sources and to take notes.

- As you add sources, put them in the format you're using (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.).

- Group sources by publication type (i.e., book, article, website).

- Number each source within the publication type group.

- For websites, include the URL information and the date you accessed each site.

- Next to each idea, include the source number from the Works Cited file and the page number from the source. See the examples below. Note that #A5 and #B2 refer to article source 5 and book source 2 from the Works Cited file.

#A5 p.35: 76.69% of the hyperlinks selected from homepage are for articles and the catalog #B2 p.76: online library guides evolved from the paper pathfinders of the 1960s

- When done taking notes, assign keywords or sub-topic headings to each idea, quote or summary.

- Use the copy and paste feature to group keywords or sub-topic ideas together.

- Back up your master list and note files frequently!

Tips for Taking Notes by Hand

- Use index cards to keep notes and track sources used in your paper.

- Include the citation (i.e., author, title, publisher, date, page numbers, etc.) in the format you're using. It will be easier to organize the sources alphabetically when creating the Works Cited page.

- Number the source cards.

- Use only one side to record a single idea, fact or quote from one source. It will be easier to rearrange them later when it comes time to organize your paper.

- Include a heading or key words at the top of the card.

- Include the Work Cited source card number.

- Include the page number where you found the information.

- Use abbreviations, acronyms, or incomplete sentences to record information to speed up the notetaking process.

- Write down only the information that answers your research questions.

- Use symbols, diagrams, charts or drawings to simplify and visualize ideas.

Forms of Notetaking

Use one of these notetaking forms to capture information:

- Summarize : Capture the main ideas of the source succinctly by restating them in your own words.

- Paraphrase : Restate the author's ideas in your own words.

- Quote : Copy the quotation exactly as it appears in the original source. Put quotation marks around the text and note the name of the person you are quoting.

Example of a Work Cited Card

Example notecard.

- << Previous: Step 4: Write

- Next: 4b. Outline the Paper >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 11:01 AM

- URL: https://libguides.elmira.edu/research

Research Guides

Gould library, reading well and taking research notes.

- How to read for college

- How to take research notes

- How to use sources in your writing

- Tools for note taking and annotations

- Mobile apps for notes and annotations

- Assistive technology

- How to cite your sources

Be Prepared: Keep track of which notes are direct quotes, which are summary, and which are your own thoughts. For example, enclose direct quotes in quotation marks, and enclose your own thoughts in brackets. That way you'll never be confused when you're writing.

Be Clear: Make sure you have noted the source and page number!

Be Organized: Keep your notes organized but in a single place so that you can refer back to notes about other readings at the same time.

Be Consistent: You'll want to find specific notes later, and one way to do that is to be consistent in the way you describe things. If you use consistent terms or tags or keywords, you'll be able to find your way back more easily.

Recording what you find

Take full notes

Whether you take notes on cards, in a notebook, or on the computer, it's vital to record information accurately and completely. Otherwise, you won't be able to trust your own notes. Most importantly, distinguish between (1) direct quotation; (2) paraphrases and summaries of the text; and (3) your own thoughts. On a computer, you have many options for making these distinctions, such as parentheses, brackets, italic or bold text, etc.

Know when to quote, paraphrase, and summarize

- Summarize when you only need to remember the main point of the passage, chapter, etc.

- Paraphrase when you are able to able to clearly state a source's point or meaning in your own words.

- Quote exactly when you need the author's exact words or authority as evidience to back up your claim. You may also want to be sure and use the author's exact wording, either because they stated their point so well, or because you want to refute that point and need to demonstrate you aren't misrepresenting the author's words.

Get the context right

Don't just record the author's words or ideas; be sure and capture the context and meaning that surrounds those ideas as well. It can be easy to take a short quote from an author that completely misrepresents his or her actual intentions if you fail to take the context into account. You should also be sure to note when the author is paraphrasing or summarizing another author's point of view--don't accidentally represent those ideas as the ideas of the author.

Example of reading notes

Here is an example of reading notes taken in Evernote, with citation and page numbers noted as well as quotation marks for direct quotes and brackets around the reader's own thoughts.

- << Previous: How to read for college

- Next: How to use sources in your writing >>

- Last Updated: Feb 7, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://gouldguides.carleton.edu/activereading

Questions? Contact [email protected]

Powered by Springshare.

- Writing Home

- Writing Advice Home

Taking Notes from Research Reading

- Printable PDF Version

- Fair-Use Policy

If you take notes efficiently, you can read with more understanding and also save time and frustration when you come to write your paper. These are three main principles

1. Know what kind of ideas you need to record

Focus your approach to the topic before you start detailed research. Then you will read with a purpose in mind, and you will be able to sort out relevant ideas.

- First, review the commonly known facts about your topic, and also become aware of the range of thinking and opinions on it. Review your class notes and textbook and browse in an encyclopaedia or other reference work.

- Try making a preliminary list of the subtopics you would expect to find in your reading. These will guide your attention and may come in handy as labels for notes.

- Choose a component or angle that interests you, perhaps one on which there is already some controversy. Now formulate your research question. It should allow for reasoning as well as gathering of information—not just what the proto-Iroquoians ate, for instance, but how valid the evidence is for early introduction of corn. You may even want to jot down a tentative thesis statement as a preliminary answer to your question. (See Using Thesis Statements .)

- Then you will know what to look for in your research reading: facts and theories that help answer your question, and other people’s opinions about whether specific answers are good ones.

2. Don’t write down too much

Your essay must be an expression of your own thinking, not a patchwork of borrowed ideas. Plan therefore to invest your research time in understanding your sources and integrating them into your own thinking. Your note cards or note sheets will record only ideas that are relevant to your focus on the topic; and they will mostly summarize rather than quote.

- Copy out exact words only when the ideas are memorably phrased or surprisingly expressed—when you might use them as actual quotations in your essay.

- Otherwise, compress ideas in your own words . Paraphrasing word by word is a waste of time. Choose the most important ideas and write them down as labels or headings. Then fill in with a few subpoints that explain or exemplify.

- Don’t depend on underlining and highlighting. Find your own words for notes in the margin (or on “sticky” notes).

3. Label your notes intelligently

Whether you use cards or pages for note-taking, take notes in a way that allows for later use.

- Save bother later by developing the habit of recording bibliographic information in a master list when you begin looking at each source (don’t forget to note book and journal information on photocopies). Then you can quickly identify each note by the author’s name and page number; when you refer to sources in the essay you can fill in details of publication easily from your master list. Keep a format guide handy (see Documentation Formats ).

- Try as far as possible to put notes on separate cards or sheets. This will let you label the topic of each note. Not only will that keep your notetaking focussed, but it will also allow for grouping and synthesizing of ideas later. It is especially satisfying to shuffle notes and see how the conjunctions create new ideas—yours.

- Leave lots of space in your notes for comments of your own—questions and reactions as you read, second thoughts and cross-references when you look back at what you’ve written. These comments can become a virtual first draft of your paper.

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Research skills.

- Searching the literature

- Note making for dissertations

- Research Data Management

- Copyright and licenses

- Publishing in journals

- Publishing academic books

- Depositing your thesis

- Research metrics

- Build your online profile

- Finding support

Note making for dissertations: First steps into writing

Note making (as opposed to note taking) is an active practice of recording relevant parts of reading for your research as well as your reflections and critiques of those studies. Note making, therefore, is a pre-writing exercise that helps you to organise your thoughts prior to writing. In this module, we will cover:

- The difference between note taking and note making

- Seven tips for good note making

- Strategies for structuring your notes and asking critical questions

- Different styles of note making

To complete this section, you will need:

- Approximately 20-30 minutes.

- Access to the internet. All the resources used here are available freely.

- Some equipment for jotting down your thoughts, a pen and paper will do, or your phone or another electronic device.

Note taking v note making

When you think about note taking, what comes to mind? Perhaps trying to record everything said in a lecture? Perhaps trying to write down everything included in readings required for a course?

- Note taking is a passive process. When you take notes, you are often trying to record everything that you are reading or listening to. However, you may have noticed that this takes a lot of effort and often results in too many notes to be useful.

- Note making , on the other hand, is an active practice, based on the needs and priorities of your project. Note making is an opportunity for you to ask critical questions of your readings and to synthesise ideas as they pertain to your research questions. Making notes is a pre-writing exercise that develops your academic voice and makes writing significantly easier.

Seven tips for effective note making

Note making is an active process based on the needs of your research. This video contains seven tips to help you make brilliant notes from articles and books to make the most of the time you spend reading and writing.

- Transcript of Seven Tips for Effective Notemaking

Question prompts for strategic note making

You might consider structuring your notes to answer the following questions. Remember that note making is based on your needs, so not all of these questions will apply in all cases. You might try answering these questions using the note making styles discussed in the next section.

- Question prompts for strategic note making

- Background question prompts

- Critical question prompts

- Synthesis question prompts

Answer these six questions to frame your reading and provide context.

- What is the context in which the text was written? What came before it? Are there competing ideas?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- How is the writing organised?

- What are the author’s methods?

- What is the author’s key argument and conclusions?

Answer these six questions to determine your critical perspectivess and develop your academic voice.

- What are the most interesting/compelling ideas (to you) in this study?

- Why do you find them interesting? How do they relate to your study?

- What questions do you have about the study?

- What could it cover better? How could it have defended its research better?

- What are the implications of the study? (Look not just to the conclusions but also to definitions and models)

- Are there any gaps in the study? (Look not just at conclusions but definitions, literature review, methodology)

Answer these five questions to compare aspects of various studies (such as for a literature review.

- What are the similarities and differences in the literature?

- Critically analyse the strengths, limitations, debates and themes that emerg from the literature.

- What would you suggest for future research or practice?

- Where are the gaps in the literature? What is missing? Why?

- What new questions should be asked in this area of study?

Styles of note making

- Linear notes . Great for recording thoughts about your readings. [video]

- Mind mapping : Great for thinking through complex topics. [video]

Further sites that discuss techniques for note making:

- Note-taking techniques

- Common note-taking methods

- Strategies for effective note making

Did you know?

How did you find this Research Skills module

Image Credits: Image #1: David Travis on Unsplash ; Image #2: Charles Deluvio on Unsplash

- << Previous: Searching the literature

- Next: Research Data Management >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/research-skills

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Graduate Research: Note-Taking and Organization

- Getting Organized

Taking Notes

- Reference Managers

Taking Notes for Research Papers

How to Take Notes

First of all, make sure that you record all necessary and appropriate information: author, title, publisher, place of publication, volume, the span of pages, date. It's probably easiest to keep this basic information about each source on individual 3x5 or 4x6 notecards. This way when you come to creating the "Works Cited" or "References" at the end of your paper, you can easily alphabetize your cards to create the list. Also, keep a running list of page numbers as you take notes so that you can identify the exact location of each piece of noted information. Remember, you will have to refer to these sources accurately, sometimes using page numbers within your paper and, depending on the type of source, using page numbers as part of your list of sources at the end of the paper.

Many people recommend taking all your notes on notecards. The advantage of notecards is that if you write very specific notes or only one idea on one side of the card, you can then spread them out on a table and rearrange them as you are structuring your paper. They're also small and neat and can help you stay organized.

Some people find notecards too small and frustrating to work with when taking notes and use a notebook instead. They leave plenty of space between notes and only write on one side of the page. Later, they either cut up their notes and arrange them as they would the cards, or they color code their notes to help them arrange information for sections or paragraphs of their paper.

What to Put into Notes

When you take notes, your job is not to write everything down, nor is it a good idea to give in to the temptation of photocopying pages or articles.

Notetaking is the process of extracting only the information that answers your research question or supports your working thesis directly. Notes can be in one of three forms: summary, paraphrase, or direct quotation. (It's a good idea to come up with a system-- you might simply label each card or note "s" "p" or "q"--as a way of keeping track of the kind of notes you took from a source.) Also, a direct quotation reproduces the source's words and punctuation exactly, so you add quotation marks around the sentence(s) to show this. Remember it is essential to record the exact page numbers of the specific notes since you will need them later for your documentation.

Work carefully to make sure you have recorded the source of your notes and the basic information you will need when citing your source, to save yourself a great deal of time and frustration--otherwise you will have to make extra trips to the library when writing your final draft.

How to Use Idea Cards

While doing your research, you will be making connections and synthesizing what you are learning. Some people find it useful to make "idea cards" or notes in which they write out the ideas and perceptions they are developing about their topic.

How to Work with Notes

- After you take notes, re-read them.

- Then re-organize them by putting similar information together. Working with your notes involves re-grouping them by topic instead of by source. Re-group your notes by re-shuffling your index cards or by color-coding or using symbols to code notes in a notebook.

- Review the topics of your newly-grouped notes. If the topics do not answer your research question or support your working thesis directly, you may need to do additional research or re-think your original research.

- During this process, you may find that you have taken notes that do not answer your research question or support your working thesis directly. Don't be afraid to throw them away.

It may have struck you that you just read a lot of "re" words: re-read, re-organize, re-group, re-shuffle, re-think. That's right; working with your notes essentially means going back and reviewing how this "new" information fits with your thoughts about the topic or issue of the research.

Grouping your notes should enable you to outline the major sections and then the paragraph of your research paper.

Credit: Online Writing Center, SUNY Empire State College

Organize Your Notes

- After you take notes, re-read them.

- Working with your notes involves re-grouping them by topic instead of by source. Re-group your notes by re-shuffling your index cards or by color-coding or using symbols to code notes in a notebook.

- Review the topics of your newly-grouped notes. If the topics do not answer your research question or support your working thesis directly, you may need to do additional research or re-think your original research.

- During this process, you may find that you have taken notes that do not answer your research question or support your working thesis directly. Don't be afraid to throw them away.

Working with your notes involves a lot of repetition: re-reading, re-organizing, re-grouping, and even re-thinking how "new" information fits with your thoughts about the topic or issue of the research. Ultimately, grouping your notes will allow you to outline the major sections and paragraphs of your research paper.

- << Previous: Getting Organized

- Next: Reference Managers >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2022 3:14 PM

- URL: https://selu.libguides.com/Notetaking

Research Paper: A step-by-step guide: 6. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Topic Ideas

- 3. Thesis Statement & Outline

- 4. Appropriate Sources

- 5. Search Techniques

- 6. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 7. Evaluating Sources

- 8. Citations & Plagiarism

- 9. Writing Your Research Paper

Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

How to take notes and document sources.

Note taking is a very important part of the research process. It will help you:

- keep your ideas and sources organized

- effectively use the information you find

- avoid plagiarism

When you find good information to be used in your paper:

- Read the text critically, think how it is related to your argument, and decide how you are going to use it in your paper.

- Select the material that is relevant to your argument.

- Copy the original text for direct quotations or briefly summarize the content in your own words, and make note of how you will use it.

- Copy the citation or publication information of the source.

There are different ways to take notes and organize your research. Check out this video, and try different strategies to find what works best for you.

- << Previous: 5. Search Techniques

- Next: 7. Evaluating Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2023 12:12 PM

- URL: https://butte.libguides.com/ResearchPaper

Writing a Research Paper: 5. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- Getting Started

- 1. Topic Ideas

- 2. Thesis Statement & Outline

- 3. Appropriate Sources

- 4. Search Techniques

- 5. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 6. Evaluating Sources

- 7. Citations & Plagiarism

- 8. Writing Your Research Paper

Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

How to take notes and document sources.

Note taking is a very important part of the research process. It will help you:

- keep your ideas and sources organized

- effectively use the information you find

- avoid plagiarism

When you find good information to be used in your paper:

- Read the text critically, think how it is related to your argument, and decide how you are going to use it in your paper.

- Select the material that is relevant to your argument.

- Copy the original text for direct quotations or briefly summarize the content in your own words, and make note of how you will use it.

- Copy the citation or publication information of the source.

- << Previous: 4. Search Techniques

- Next: 6. Evaluating Sources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 5:26 PM

- URL: https://kenrick.libguides.com/writing-a-research-paper

Finally see how to stop getting stuck in a project management tool

20 min. personalized consultation with a project management expert

Smart Note-Taking for Research Paper Writing

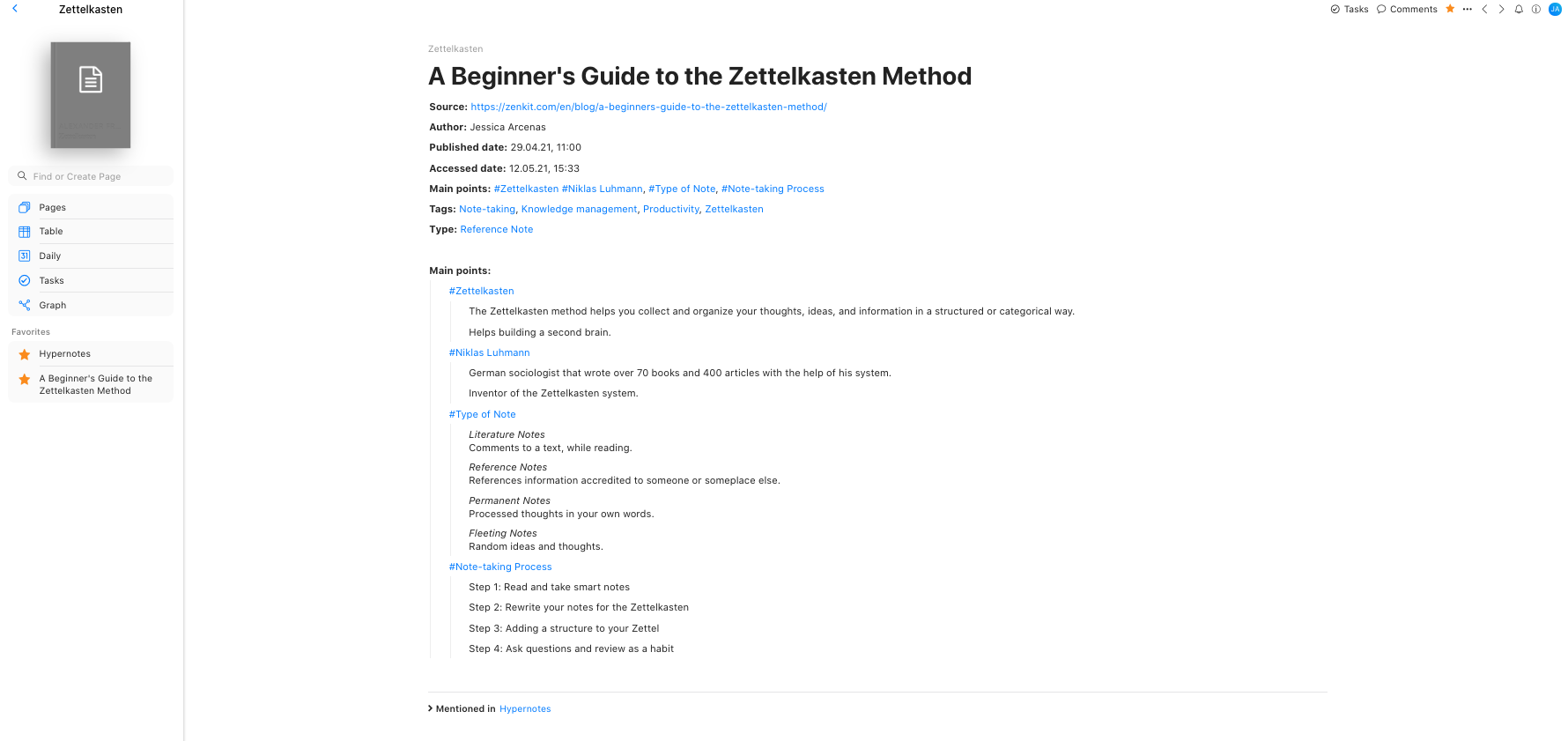

How to organize research notes using the Zettelkasten Method when writing academic papers

With plenty of note-taking tips and apps available, online and in paper form, it’s become extremely easy to take note of information, ideas, or thoughts. As simple as it is to write down an idea or jot down a quote, the skill of academic research and writing for a thesis paper is on another level entirely. And keeping a record or an archive of all of the information you need can quickly require a very organized system.

The use of index cards seems old-fashioned considering that note-taking apps (psst! Hypernotes ) offer better functionality and are arguably more user-friendly. However, software is only there to help aid our individual workflow and thinking process. That’s why understanding and learning how to properly research, take notes and write academic papers is still a highly valuable skill.

Let’s Start Writing! But Where to Start…

Writing academic papers is a vital skill most students need to learn and practice. Academic papers are usually time-intensive pieces of written content that are a requirement throughout school or at University. Whether a topic is assigned or you have to choose your own, there’s little room for variation in how to begin.

Popular and purposeful in analyzing and evaluating the knowledge of the author as well as assessing if the learning objectives were met, research papers serve as information-packed content. Most of us may not end up working jobs in academic professions or be researchers at institutions, where writing research papers is also part of the job, but we often read such papers.

Despite the fact that most research papers or dissertations aren’t often read in full, journalists, academics, and other professionals regularly use academic papers as a basis for further literary publications or blog articles. The standard of academic papers ensures the validity of the information and gives the content authority.

There’s no-nonsense in research papers. To make sure to write convincing and correct content, the research stage is extremely important. And, naturally, when doing any kind of research, we take notes.

Why Take Notes?

There are particular standards defined for writing academic papers . In order to meet these standards, a specific amount of background information and researched literature is required. Taking notes helps keep track of read/consumed literary material as well as keeps a file of any information that may be of importance to the topic.

The aim of writing isn’t merely to advertise fully formed opinions, but also serves the purpose of developing opinions worth sharing in the first place.

What is Note-Taking?

Note-taking (sometimes written as notetaking or note-taking ) is the practice of recording information from different sources and platforms. For academic writing, note-taking is the process of obtaining and compiling information that answers and supports the research paper’s questions and topic. Notes can be in one of three forms: summary, paraphrase, or direct quotation.

Note-taking is an excellent process useful for anyone to turn individual thoughts and information into organized ideas ready to be communicated through writing. Notes are, however, only as valuable as the context. Since notes are also a byproduct of the information we consume daily, it’s important to categorize information, develop connections, and establish relationships between pieces of information.

What Type of Notes Can I Take?

- Explanation of complex theories

- Background information on events or persons of interest

- Definitions of terms

- Quotations of significant value

- Illustrations or graphics

Note-Taking 101

Taking notes or doing research for academic papers shouldn’t be that difficult, considering we take notes all the time. Wrong. Note-taking for research papers isn’t the same as quickly noting down an interesting slogan or cool quote from a video, putting it on a sticky note, and slapping it onto your bedroom or office wall.

Note-taking for research papers requires focus and careful deliberation of which information is important to note down, keep on file, or use and reference in your own writing. Depending on the topic and requirements of your research paper from your University or institution, your notes might include explanations of complex theories, definitions, quotations, and graphics.

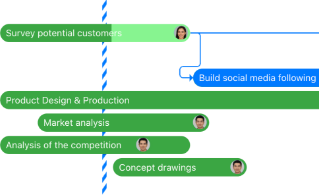

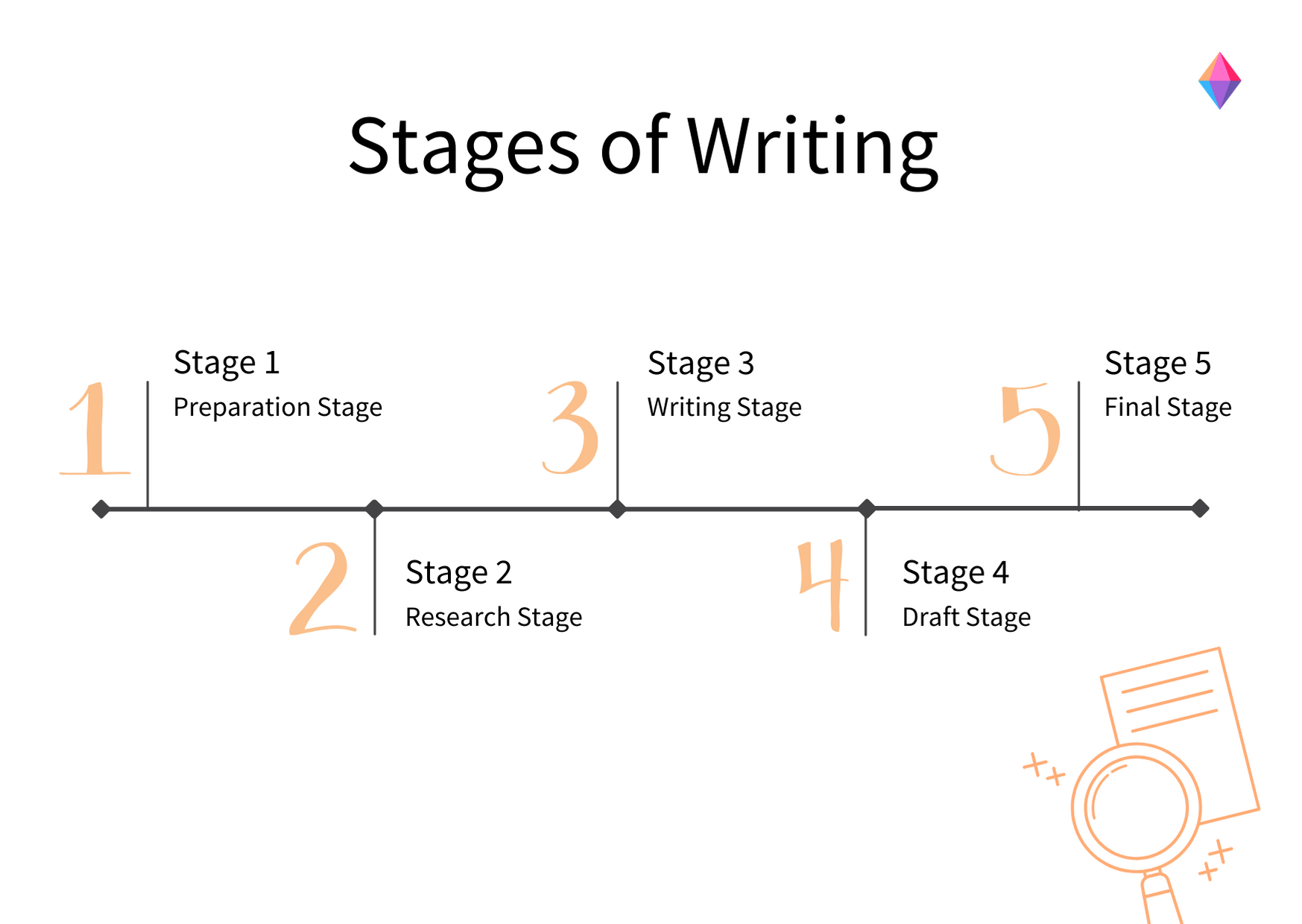

Stages of Research Paper Writing

1. Preparation Stage

Before you start, it’s recommended to draft a plan or an outline of how you wish to begin preparing to write your research paper. Make note of the topic you will be writing on, as well as the stylistic and literary requirements for your paper.

2. Research Stage

In the research stage, finding good and useful literary material for background knowledge is vital. To find particular publications on a topic, you can use Google Scholar or access literary databases and institutions made available to you through your school, university, or institution.

Make sure to write down the source location of the literary material you find. Always include the reference title, author, page number, and source destination. This saves you time when formatting your paper in the later stages and helps keep the information you collect organized and referenceable.

In the worst-case scenario, you’ll have to do a backward search to find the source of a quote you wrote down without reference to the original literary material.

3. Writing Stage

When writing, an outline or paper structure is helpful to visually break up the piece into sections. Once you have defined the sections, you can begin writing and referencing the information you have collected in the research stage.

Clearly mark which text pieces and information where you relied on background knowledge, which texts are directly sourced, and which information you summarized or have written in your own words. This is where your paper starts to take shape.

4. Draft Stage

After organizing all of your collected notes and starting to write your paper, you are already in the draft stage. In the draft stage, the background information collected and the text written in your own words come together. Every piece of information is structured by the subtopics and sections you defined in the previous stages.

5. Final Stage

Success! Well… almost! In the final stage, you look over your whole paper and check for consistency and any irrelevancies. Read through the entire paper for clarity, grammatical errors , and peace of mind that you have included everything important.

Make sure you use the correct formatting and referencing method requested by your University or institution for research papers. Don’t forget to save it and then send the paper on its way.

Best Practice Note-Taking Tips

- Find relevant and authoritative literary material through the search bar of literary databases and institutions.

- Practice citation repeatedly! Always keep a record of the reference book title, author, page number, and source location. At best, format the citation in the necessary format from the beginning.

- Organize your notes according to topic or reference to easily find the information again when in the writing stage. Work invested in the early stages eases the writing and editing process of the later stages.

- Summarize research notes and write in your own words as much as possible. Cite direct quotes and clearly mark copied text in your notes to avoid plagiarism.

Take Smart Notes

Taking smart notes isn’t as difficult as it seems. It’s simply a matter of principle, defined structure, and consistency. Whether you opt for a paper-based system or use a digital tool to write and organize your notes depends solely on your individual personality, needs, and workflow.

With various productivity apps promoting diverse techniques, a good note-taking system to take smart notes is the Zettelkasten Method . Invented by Niklas Luhmann, a german sociologist and researcher, the Zettelkasten Method is known as the smart note-taking method that popularized personalized knowledge management.

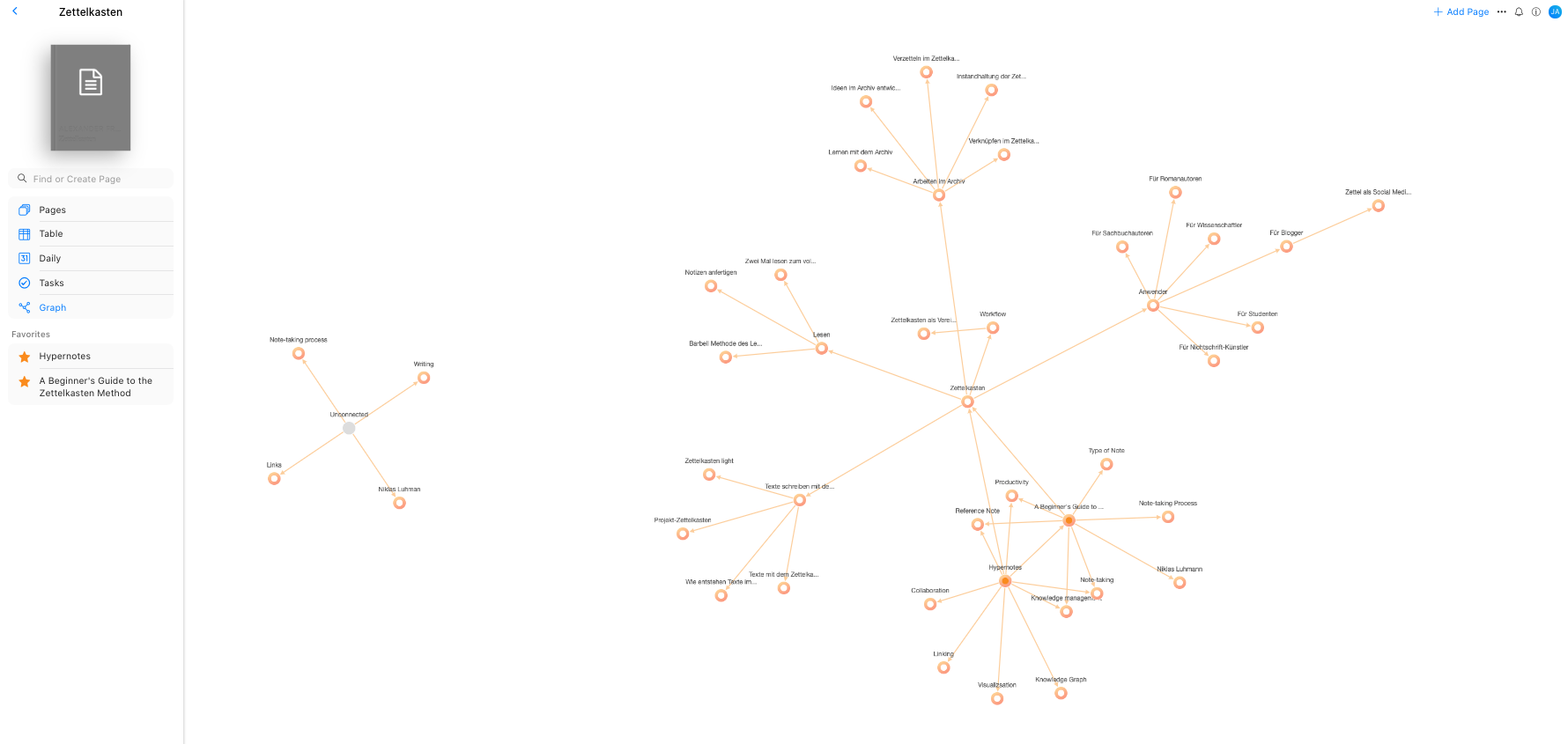

As a strategic process for thinking and writing, the Zettelkasten Method helps you organize your knowledge while working, studying, or researching. Directly translated as a ‘note box’, Zettelkasten is simply a framework to help organize your ideas, thoughts, and information by relating pieces of knowledge and connecting pieces of information to each other.

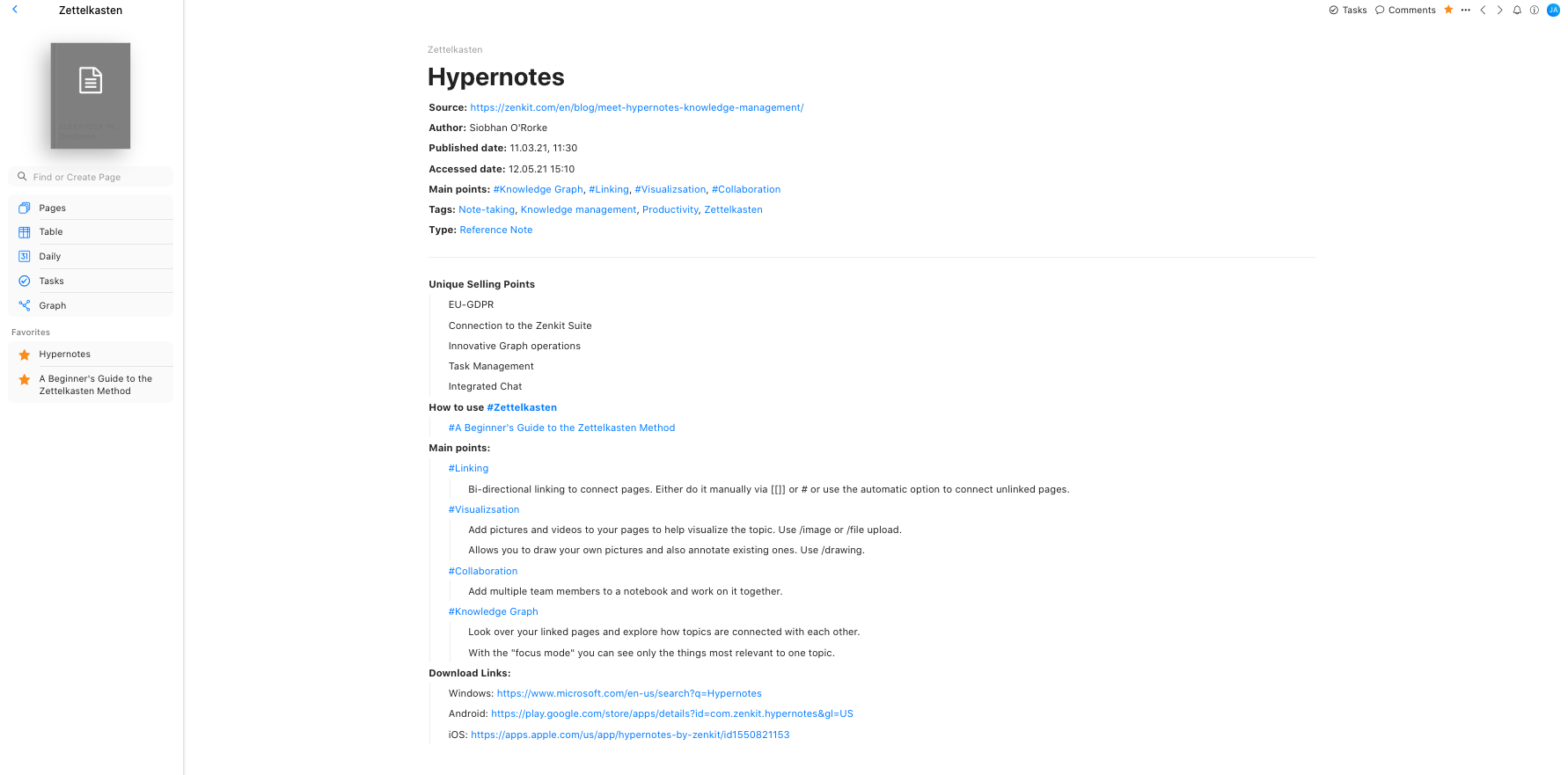

Hypernotes is a note-taking app that can be used as a software-based Zettelkasten, with integrated features to make smart note-taking so much easier, such as auto-connecting related notes, and syncing to multiple devices. In each notebook, you can create an archive of your thoughts, ideas, and information.

Using the tag system to connect like-minded ideas and information to one another and letting Hypernotes do its thing with bi-directional linking, you’ll soon create a web of knowledge about anything you’ve ever taken note of. This feature is extremely helpful to navigate through the enormous amounts of information you’ve written down. Another benefit is that it assists you in categorizing and making connections between your ideas, thoughts, and saved information in a single notebook. Navigate through your notes, ideas, and knowledge easily.

Ready, Set, Go!

Writing academic papers is no simple task. Depending on the requirements, resources available, and your personal research and writing style, techniques, apps, or practice help keep you organized and increase your productivity.

Whether you use a particular note-taking app like Hypernotes for your research paper writing or opt for a paper-based system, make sure you follow a particular structure. Repeat the steps that help you find the information you need quicker and allow you to reproduce or create knowledge naturally.

Images from NeONBRAND , hana_k and Surface via Unsplash

A well-written piece is made up of authoritative sources and uses the art of connecting ideas, thoughts, and information together. Good luck to all students and professionals working on research paper writing! We hope these tips help you in organizing the information and aid your workflow in your writing process.

Cheers, Jessica and the Zenkit Team

FREE 20 MIN. CONSULTATION WITH A PROJECT MANAGEMENT EXPERT

Wanna see how to simplify your workflow with Zenkit in less than a day?

- digital note app

- how to smart notes

- how to take notes

- hypernotes note app

- hypernotes take notes

- note archive software

- note taking app for students

- note taking tips

- note-taking

- note-taking app

- organize research paper

- reading notes

- research note taking

- research notes

- research paper writing

- smart notes

- taking notes zettelkasten method

- thesis writing

- writing a research paper

- writing a thesis paper

- zettelkasten method

More from Karen Bradford

10 Ways to Remember What You Study

More from Kelly Moser

How Hot Desking Elevates the Office Environment in 2024

More from Chris Harley

8 Productivity Tools for Successful Content Marketing

2 thoughts on “ Smart Note-Taking for Research Paper Writing ”

Thanks for sending really an exquisite text.

Great article thank you for sharing!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Zenkit Comment Policy

At Zenkit, we strive to post helpful, informative, and timely content. We want you to feel welcome to comment with your own thoughts, feedback, and critiques, however we do not welcome inappropriate or rude comments. We reserve the right to delete comments or ban users from commenting as needed to keep our comments section relevant and respectful.

What we encourage:

- Smart, informed, and helpful comments that contribute to the topic. Funny commentary is also thoroughly encouraged.

- Constructive criticism, either of the article itself or the ideas contained in it.

- Found technical issues with the site? Send an email to [email protected] and specify the issue and what kind of device, operating system, and OS version you are using.

- Noticed spam or inappropriate behaviour that we haven’t yet sorted out? Flag the comment or report the offending post to [email protected] .

What we’d rather you avoid:

Rude or inappropriate comments.

We welcome heated discourse, and we’re aware that some topics cover things people feel passionately about. We encourage you to voice your opinions, however in order for discussions to remain constructive, we ask that you remember to criticize ideas, not people.

Please avoid:

- name-calling

- ad hominem attacks

- responding to a post’s tone instead of its actual content

- knee-jerk contradiction

Comments that we find to be hateful, inflammatory, threatening, or harassing may be removed. This includes racist, gendered, ableist, ageist, homophobic, and transphobic slurs and language of any sort. If you don’t have something nice to say about another user, don't say it. Treat others the way you’d like to be treated.

Trolling or generally unkind behaviour

If you’re just here to wreak havoc and have some fun, and you’re not contributing meaningfully to the discussions, we will take actions to remove you from the conversation. Please also avoid flagging or downvoting other users’ comments just because you disagree with them.

Every interpretation of spamming is prohibited. This means no unauthorized promotion of your own brand, product, or blog, unauthorized advertisements, links to any kind of online gambling, malicious sites, or otherwise inappropriate material.

Comments that are irrelevant or that show you haven’t read the article

We know that some comments can veer into different topics at times, but remain related to the original topic. Be polite, and please avoid promoting off-topic commentary. Ditto avoid complaining we failed to mention certain topics when they were clearly covered in the piece. Make sure you read through the whole piece before saying your piece!

Breaches of privacy

This should really go without saying, but please do not post personal information that may be used by others for malicious purposes. Please also do not impersonate authors of this blog, or other commenters (that’s just weird).

How to Take Better Notes During Lectures, Discussions, and Interviews

Tried-and-True Methods and Tips From Expert Note-Takers

Horst Tappe / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Note-taking is the practice of writing down or otherwise recording key points of information. It's an important part of the research process. Notes taken on class lectures or discussions may serve as study aids, while notes taken during an interview may provide material for an essay , article , or book. "Taking notes doesn't simply mean scribbling down or marking up the things that strike your fancy," say Walter Pauk and Ross J.Q. Owens in their book, "How to Study in College." "It means using a proven system and then effectively recording information before tying everything together."

Cognitive Benefits of Note-Taking

Note-taking involves certain cognitive behavior; writing notes engages your brain in specific and beneficial ways that help you grasp and retain information. Note-taking can result in broader learning than simply mastering course content because it helps you to process information and make connections between ideas, allowing you to apply your new knowledge to novel contexts, according to Michael C. Friedman, in his paper, "Notes on Note-Taking: Review of Research and Insights for Students and Instructors," which is part of the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching.

Shelley O'Hara, in her book, "Improving Your Study Skills: Study Smart, Study Less," agrees, stating:

"Taking notes involves active listening , as well as connecting and relating information to ideas you already know. It also involves seeking answers to questions that arise from the material."

Taking notes forces you to actively engage your brain as you identify what's important in terms of what the speaker is saying and begin to organize that information into a comprehensible format to decipher later. That process, which is far more than simply scribbling what you hear, involves some heavy brainwork.

Most Popular Note-Taking Methods

Note-taking aids in reflection, mentally reviewing what you write. To that end, there are certain methods of note-taking that are among the most popular:

- The Cornell method involves dividing a piece of paper into three sections: a space on the left for writing the main topics, a larger space on the right to write your notes, and a space at the bottom to summarize your notes. Review and clarify your notes as soon as possible after class. Summarize what you've written on the bottom of the page, and finally, study your notes.

- Creating a mind map is a visual diagram that lets you organize your notes in a two-dimensional structure, says Focus . You create a mind map by writing the subject or headline in the center of the page, then add your notes in the form of branches that radiate outward from the center.

- Outlining is similar to creating an outline that you might use for a research paper.

- Charting allows you to break up information into such categories as similarities and differences; dates, events, and impact; and pros and cons, according to East Carolina University .

- The sentence method is when you record every new thought, fact, or topic on a separate line. "All information is recorded, but it lacks [the] clarification of major and minor topics. Immediate review and editing are required to determine how information should be organized," per East Carolina University.

Two-Column Method and Lists

There are, of course, other variations on the previously described note-taking methods, such as the two-column method, says Kathleen T. McWhorter, in her book, "Successful College Writing," who explains that to use this method:

"Draw a vertical line from the top of a piece of paper to the bottom. The left-hand column should be about half as wide as the right-hand column. In the wider, right-hand column, record ideas and facts as they are presented in a lecture or discussion. In the narrower, left-hand column, note your own questions as they arise during the class."

Making a list can also be effective, say John N. Gardner and Betsy O. Barefoot in "Step by Step to College and Career Success." "Once you have decided on a format for taking notes, you may also want to develop your own system of abbreviations ," they suggest.

Note-Taking Tips

Among other tips offered by note-taking experts:

- Leave a space between entries so that you can fill in any missing information.

- Use a laptop and download information to add to your notes either during or after the lecture.

- Understand that there is a difference between taking notes on what you read and what you hear (in a lecture). If you're unsure what that might be, visit a teacher or professor during office hours and ask them to elaborate.

If none of these methods suit you, read the words of author Paul Theroux in his article "A World Duly Noted" published in The Wall Street Journal in 2013:

"I write down everything and never assume that I will remember something because it seemed vivid at the time."

And once you read these words, don't forget to jot them down in your preferred method of note-taking so that you won't forget them.

Brandner, Raphaela. “How to Take Effective Notes Using Mind Maps.” Focus.

East Carolina University.

Friedman, Michael C. "Notes on Note-Taking: Review of Research and Insights for Students and Instructors." Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teachi ng, 2014.

Gardner, John N. and Betsy O. Barefoot. Step by Step to College and Career Success . 2 nd ed., Thomson, 2008.

McWhorter, Kathleen T. Successful College Writing . 4 th ed, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2010.

O'Hara, Shelley. Improving Your Study Skills: Study Smart, Study Less . Wiley, 2005.

Pauk, Walter and Ross J.Q. Owens . How to Study in College . 11 th ed, Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2004.

Theroux, Paul. "A World Duly Noted." The Wall Street Journal , 3 May 2013.

- How To Take Good Biology Notes

- How to Take Notes with the Cornell Note System

- The Best Study Techniques for Your Learning Style

- 10 Do's and Don'ts for Note Taking in Law School

- How To Take Notes

- Research Note Cards

- The Case for the Importance of Taking Notes

- How to Take Notes on a Laptop and Should You

- 8 Tips for Taking Notes from Your Reading

- Helping Students Take Notes

- Great Solutions for 5 Bad Study Habits

- How to Take Math Notes With a Smartpen

- Improve Your Reading Speed and Comprehension With the SQ3R Method

- How Shorthand Writing Can Improve Your Note-Taking Skills

- How to Be Successful in College

- 10 Tips for Art History Students

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Organizing Research: Taking and Keeping Effective Notes

Once you’ve located the right primary and secondary sources, it’s time to glean all the information you can from them. In this chapter, you’ll first get some tips on taking and organizing notes. The second part addresses how to approach the sort of intermediary assignments (such as book reviews) that are often part of a history course.

Honing your own strategy for organizing your primary and secondary research is a pathway to less stress and better paper success. Moreover, if you can find the method that helps you best organize your notes, these methods can be applied to research you do for any of your classes.

Before the personal computing revolution, most historians labored through archives and primary documents and wrote down their notes on index cards, and then found innovative ways to organize them for their purposes. When doing secondary research, historians often utilized (and many still do) pen and paper for taking notes on secondary sources. With the advent of digital photography and useful note-taking tools like OneNote, some of these older methods have been phased out – though some persist. And, most importantly, once you start using some of the newer techniques below, you may find that you are a little “old school,” and might opt to integrate some of the older techniques with newer technology.

Whether you choose to use a low-tech method of taking and organizing your notes or an app that will help you organize your research, here are a few pointers for good note-taking.

Principles of note-taking

- If you are going low-tech, choose a method that prevents a loss of any notes. Perhaps use one spiral notebook, or an accordion folder, that will keep everything for your project in one space. If you end up taking notes away from your notebook or folder, replace them—or tape them onto blank pages if you are using a notebook—as soon as possible.

- If you are going high-tech, pick one application and stick with it. Using a cloud-based app, including one that you can download to your smart phone, will allow you to keep adding to your notes even if you find yourself with time to take notes unexpectedly.

- When taking notes, whether you’re using 3X5 note cards or using an app described below, write down the author and a shortened title for the publication, along with the page number on EVERY card. We can’t emphasize this point enough; writing down the bibliographic information the first time and repeatedly will save you loads of time later when you are writing your paper and must cite all key information.

- Include keywords or “tags” that capture why you thought to take down this information in a consistent place on each note card (and when using the apps described below). If you are writing a paper about why Martin Luther King, Jr., became a successful Civil Rights movement leader, for example, you may have a few theories as you read his speeches or how those around him described his leadership. Those theories—religious beliefs, choice of lieutenants, understanding of Gandhi—might become the tags you put on each note card.

- Note-taking applications can help organize tags for you, but if you are going low tech, a good idea is to put tags on the left side of a note card, and bibliographic info on the right side.

Organizing research- applications that can help

Using images in research.

- If you are in an archive: make your first picture one that includes the formal collection name, the box number, the folder name and call numbe r and anything else that would help you relocate this information if you or someone else needed to. Do this BEFORE you start taking photos of what is in the folder.

- If you are photographing a book or something you may need to return to the library: take a picture of all the front matter (the title page, the page behind the title with all the publication information, maybe even the table of contents).

Once you have recorded where you find it, resist the urge to rename these photographs. By renaming them, they may be re-ordered and you might forget where you found them. Instead, use tags for your own purposes, and carefully name and date the folder into which the photographs were automatically sorted. There is one free, open-source program, Tropy , which is designed to help organize photos taken in archives, as well as tag, annotate, and organize them. It was developed and is supported by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. It is free to download, and you can find it here: https://tropy.org/ ; it is not, however, cloud-based, so you should back up your photos. In other cases, if an archive doesn’t allow photography (this is highly unlikely if you’ve made the trip to the archive), you might have a laptop on hand so that you can transcribe crucial documents.

Using note or project-organizing apps

When you have the time to sit down and begin taking notes on your primary sources, you can annotate your photos in Tropy. Alternatively, OneNote, which is cloud-based, can serve as a way to organize your research. OneNote allows you to create separate “Notebooks” for various projects, but this doesn’t preclude you from searching for terms or tags across projects if the need ever arises. Within each project you can start new tabs, say, for each different collection that you have documents from, or you can start new tabs for different themes that you are investigating. Just as in Tropy, as you go through taking notes on your documents you can create your own “tags” and place them wherever you want in the notes.

Another powerful, free tool to help organize research, especially secondary research though not exclusively, is Zotero found @ https://www.zotero.org/ . Once downloaded, you can begin to save sources (and their URL) that you find on the internet to Zotero. You can create main folders for each major project that you have and then subfolders for various themes if you would like. Just like the other software mentioned, you can create notes and tags about each source, and Zotero can also be used to create bibliographies in the precise format that you will be using. Obviously, this function is super useful when doing a long-term, expansive project like a thesis or dissertation.

How History is Made: A Student’s Guide to Reading, Writing, and Thinking in the Discipline Copyright © 2022 by Stephanie Cole; Kimberly Breuer; Scott W. Palmer; and Brandon Blakeslee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Note-taking: A Research Roundup

September 9, 2018

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Peergrade and 3Doodler

Let’s talk about note-taking. Every day, in classrooms all over the world, students are taking notes. I have my own half-baked ideas about what makes one approach better than another, and I’m sure you do too. But if we’re going to call ourselves professionals, we need to know what the research says, yes?

So I’ve combed through about three decades’ worth of research, and I’m going to tell you what it says about best practices in note-taking. Although this is not an exhaustive summary, it hits on some of the most frequently debated questions on the subject.

This information is going to be useful for any subject area—I found some really good stuff that would be especially useful for STEM teachers or anyone who does heavy work with calculations, diagrams, and other technical illustrations. Of course, there’s plenty here for teachers of social studies, English, and the humanities as well, so everyone sit tight because you’ll probably come away with something you can apply to your classroom.

First, Let’s Talk About Lectures

When we think about note-taking, it’s natural to assume a context of lecture-based lessons. And yes, that is one common scenario when a student is likely to take notes. But other learning experiences also lend themselves to note-taking: Watching videos in a flipped or blended environment, reading assigned textbook chapters or handouts, doing research for a project, and going on field trips can all be opportunities for taking notes.

So instead of referring to lectures in this overview, I’ll just talk about learning experiences or intake sessions—times when students are absorbing content or skills through some sort of medium, as opposed to purely applying that content or synthesizing it into some kind of product. Even in student-centered, project-driven classrooms where students pursue their own authentic tasks like the Apollo School , or in more traditional classrooms that set aside time for Genius Hour projects, students need to gather, encode, and store information, so note-taking would still be a fit.

What the Research Says About Note-Taking

1. note-taking matters..

Whether it’s taking notes from lectures (Kiewra, 2002) or from reading (Rahmani & Sadeghi, 2011; Chang & Ku, 2014), note-taking has been shown to improve student learning. In other words, if we want our students to remember more of what they learn in our classes, it’s better to have them take notes than it is to not have them take notes.

The thinking behind this is that note-taking requires effort. Rather than passively taking information in, the act of encoding the information into words or pictures forms new pathways in the brain, which stores it more firmly in long-term memory. On top of that, having the information stored in a new place gives students the opportunity to revisit it later and reinforce the learning that happened the first time around.

So if you’re not currently having students take notes in your class, consider adding note-taking to your regular classroom routine. With that said, a number of other factors can influence the potency of a student’s note-taking, and that is what these other points will address.

2. More is better.

Although students are often encouraged to keep notes brief, it turns out that in general, the more notes students take, the more information they tend to remember later. The quantity of notes is directly related to how much information students retain (Nye, Crooks, Powley, & Tripp, 1984).

This would be useful to share with students. If they know that more complete notes will result in better learning, they may be more likely to record additional information in their notes, rather than striving for brevity.

Obviously, some students are going to be faster note-takers than others, and this will allow them to take more complete notes. But you can do quite a bit to help all students get more information into their notes, regardless of their natural speed, and that’s what we’ll talk about next.

3. Explicitly teaching note-taking strategies can make a difference.

Although some students seem to have an intuitive sense for what notes to record, for everyone else, getting trained in specific note-taking strategies can significantly improve the quality of notes and the amount of material they remember later. (Boyle, 2013; Rahmani & Sadeghi, 2011; Robin, Foxx, Martello, & Archable, 1977). This is especially true for students with learning disabilities.

One frequently used note-taking system is Cornell Notes . This approach has been around for decades, and the format provides a simple way to take “live” notes in class and condense and review them later.

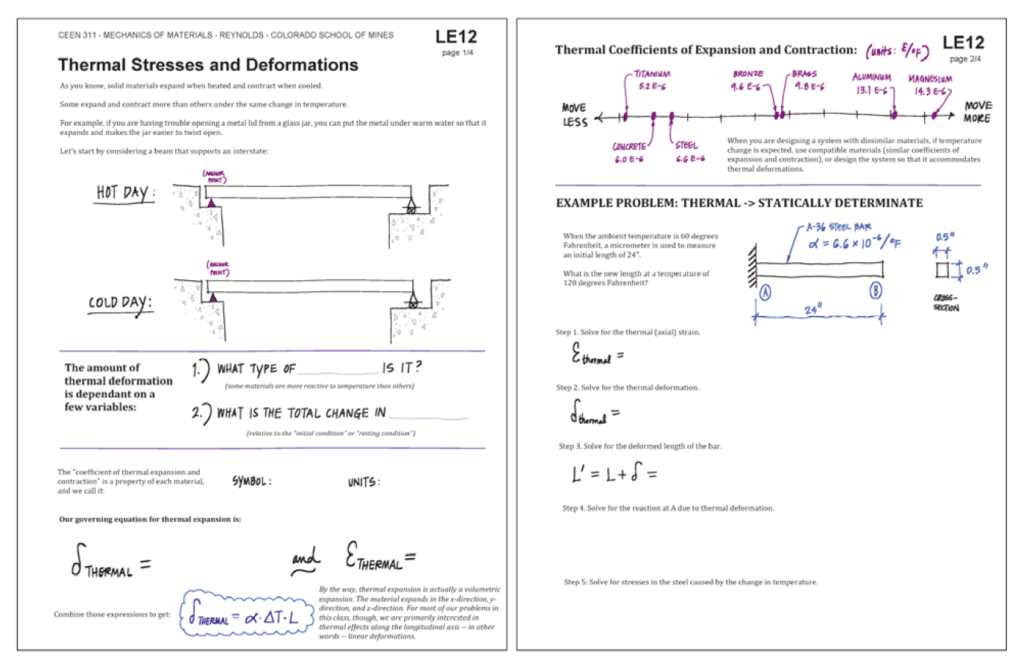

4. Adding visuals boosts the power of notes.

Compared with writing alone, adding drawings to notes to represent concepts, terms, and relationships has a significant effect on memory and learning (Wammes, Meade, & Fernandes, 2016).

The growing popularity of sketchnoting in recent years suggests that teachers are well on their way to taking advantage of this research.

This video combines sketchnoting with Cornell Notes, and it’s an approach I think is definitely worth considering.

To explore sketchnoting more deeply, check out this list of sketchnoting resources compiled by celebrated education sketchnote artist Sylvia Duckworth .

5. Revision, collaboration, and pausing boosts the power of notes.

When students are given the opportunity to revise, add to, or rewrite their notes, they tend to retain more information. And when that revision happens during deliberate pauses in a lecture or other learning experience, students remember the information better and take better notes than if the revision happens after the learning experience is over. Finally, if students collaborate on this revision with partners, they record even more complete notes and score higher on post-tests (Luo, Kiewra, & Samuelson, 2016).