Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis

- ROBERT T. FINTZY , M.D. ,

Search for more papers by this author

Henceforth, be forewarned: not everyone doing criminal profile work is doing it correctly. “Many dangerously unqualified, unscrupulous individuals [are in] the practice of creating criminal profiles” (p. xxix), declares Brent Turvey, which is why he wrote this book. It is his attempt at providing the solid foundation on which a standard of workmanship, ethics, definitions, practices, methodology, training, education, and peer review can be uniformly established so that criminal profiling can become a profession rather than a haphazard job for ill-prepared probers. This text documents the principles of proper criminal profiling and undertakes to establish definite criteria for professionalization.

What is criminal profiling? Whatever one has gleaned from films and fiction—with all due respect to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes—is misleading. The current loose definition describes criminal profiling as any process elucidating notions about a sought-after criminal. However, Turvey dismisses the popular myth that profilers are born with an intuitive gift. Instead, Turvey advocates a discipline that will necessitate the careful evaluation of physical evidence, collected and properly analyzed by a team of specialists from different areas, for the purpose of systematically reconstructing the crime scene, developing a strategy to assist in the capture of the offender, and thereafter aiding in the trial. In his schema, a criminal profiler is only one component, although an integral one, in the criminal investigation process.

Turvey differentiates between inductive and deductive criminal profiling. The former involves broad generalizations and/or statistical reasoning—a subjective approach in Turvey’s view. Turvey favors the deductive method of criminal profiling, in which the criminal profiler possesses an open mind; questions all assumptions, premises, and opinions put forth; and demands collaboration regardless of how distinguished the supplier of the input. Here, the emphasis is on the profiler’s objectivity, self-knowledge (to overcome transference distortions), and critical thinking skills—plus an ability to try to understand the needs being satisfied by each behavior of the offender as well as the offender’s patterns. Turvey places great emphasis on all forms of forensic analysis (e.g., wound analysis, blood stain pattern analysis, and bullet trajectory analysis), crime scene characteristics (including photos), victim and witness statements, and a thorough study of the characteristics of the victim—yes, the victim. He uses the crime scene characteristics to differentiate between modus operandi and “signature behaviors” (i.e., actions unique to the crime but not necessary to commit the crime), as well as to determine inferences about the offender’s state of mind at the time of the crime, his or her planning, level of skill, victim selection, fantasy, motivation, and degree of risk taken. Turvey labels his process behavioral evidence analysis and considers it objective because it is based on facts rather than averages and extrapolations from statistics. He acknowledges that criminal profiling is a skill rather than an art or science.

Turvey reminds the reader that no two cases are exactly alike; hence, the inductive method, with its “magical” quality, is great for Hollywood but is not the most effective practice. The criminal profiler’s gut instinct, unless it can be concretely confirmed, tends to lead the criminal profiler astray and wastes valuable time. Not only do criminals think differently than most people, but Turvey points out that behavior has different meanings between cultures and from region to region. Necessarily, behavioral evidence analysis must be a dynamic process, ever-changing as the successful criminal’s methods become more refined, or deteriorate, over the course of time.

As I understand it, a criminal profiler needs to be a monitor, coordinator, interpreter, and advisor to the different branches of the investigator tree—with a premium placed on facts rather than theories. The value of teamwork is crucial. Each team member must recognize the complementarity of all team members and be willing to share information. Historically, many unsuccessful investigations have been marked by a lack of interagency cooperation (secondary to politics, turf battles, etc.). Furthermore, there are differences in skill levels among team members, despite the number of years of experience. Since the criminal profile is vitiated whenever any part lacks merit, the criminal profiler must check all assumptions. Wound patterns, for example, are complex, and even well-trained medical examiners can miss and/or misinterpret them—thus, the need for multiple forensic scientists. In addition, the criminal profiler’s competency can be compromised if he or she fails to visit the crime scene.

Although forensic psychiatrists can perform clinical interviews for the purpose of diagnosis, treatment, and courtroom competency/sanity assessment, they cannot do the work of a criminal profiler. A psychiatrist can contribute to the criminal profile but is only one member of a team. The same can be said of law enforcement agents, psychologists, sociologists, medical examiners, and detectives. Far more advanced training is required to become a professional criminal profiler, training that has heretofore been nonregulated—a situation that Turvey hopes to radically change, with this book as catalyst and guide.

The sections of the book that interested me the most are diverse. The preface, where the author relates those factors which led him to become a criminal profiler, is a sensitive, well-written, personal introduction. Then, as gory as is the chapter on wound analysis (color photos included—not meant for the squeamish!), I ultimately became convinced that the minute details described by the medical examiner rank as one of the most enlightening, mind-stimulating contributing factors in the effort to weed out a killer.

Intensive case examples in the appendixes of the book provocatively exercised my own detective mind. In appendix IIA, the Jon Benet Ramsey presentation includes a detailed autopsy description that evidently had not appeared publicly and, without stating it directly, unequivocally points to a particular suspect. To my chagrin, John Douglas, a highly respected criminal consultant, certainly seems to have goofed by basing his profile solely on his own conjoint 4.5-hour interview with the parents. Appendix I details more about the “Jack the Ripper” murders than one probably is familiar with and also permitted me the opportunity to think along as an involved investigator. Appendix IIIA presents an actual behavioral evidence analysis report, 56 pages worth, that is thorough and clear.

Most of the chapters are by Turvey himself. The writing and direction are consistent throughout—with the exception of chapter 21 by U.K. psychiatrist Dr. Diana Tamlyn, which reveals a lack of knowledge about what truly constitutes a professional criminal profiler and therefore made me wonder why these nine pages were included. Most chapters are mercifully brief, thus allowing for relief and frequent respites to assimilate the information. Unique, and more helpful than traditional footnotes, are numbered asides that appear in the more-than-ample margins. Wide borders also allow for spontaneous reader’s notes, and I highly recommend this format for future books.

The chapters address investigative as well as trial strategies, ethics, alternate methods of criminal profiling, arson, serial rape/homicide, criminal behavior on the Internet, task force management, and more. This book is a text, reference source, and proselytizing attempt, all in one. A glossary, bibliography, and index abet this worthy contribution. One disappointment, though: Turvey (pp. 195, 448) incorrectly says that the only difference between a sociopath and a psychopath is that the former originates from social forces and early experiences. Not only is the etiology of both these entities unclear, but 40 years in psychiatry has taught me that the only distinction is that a psychopath commits violent crimes.

Certainly, quite a few of Turvey’s opinions are subject to controversy. For instance, in chapter 24, he attributes society’s interest in serial rape and serial homicide to venial excitement rather than considering it might be an attempt at self-protection and/or understanding for prophylactic reasons. I also object to his facile dismissal of less-than-scientific sources, such as handwriting analysis and polygraph tests, as psychological speculations. Although these have their limitations, when facts are lacking, as they often are, such intuitive offerings can prove useful. It seems to me that a conflation of both inductive and deductive criminal profiling, with the main emphasis on the latter, rather than Turvey’s idealistic unitary bias, could be practical.

Criminal Profiling is not for casual or marathon reading. It requires the concentration and diligence possible only in short spurts of study. Remarkably, the redundancy throughout the book serves a didactic function by clarifying and reinforcing important points. Psychiatrists will be interested to know that behavioral evidence analysis techniques have no clinical purpose—they are not based on an interest in an offender’s mental well-being but on the goal of protecting society. Turvey further adds, “Freudian theories…are not designed for investigative purposes” (p. 237). The primary goals of criminal profiling include the reduction of the viable suspect pool in a criminal investigation, assistance in the linkage of potentially related crimes, assessment of the potential for escalation of criminal behavior, provision of relevant leads and strategies, and keeping the investigation on track. The criminal profiler is not preoccupied with specifically naming the offender. Criminal profilers are advisors; detectives and investigators solve cases.

This book should be reviewed by anyone intent on becoming a professional criminal profiler. It would also be a good idea if such an aspirant possessed an ample cache of compulsive traits because the efficient criminal profile has to be so meticulous. The material contained in this book is only a beginning; prolonged first-hand investigatory experience under an expert’s tutelage is mandatory.

Criminal Profiling would be of value to psychiatrists in two respects: 1) as a humbling experience in terms of recognizing the limitations of a psychiatrist in a criminal investigation and 2) as an intellectual expansion for those with polymathic proclivities.

By Brent Turvey, M.S. San Diego, Academic Press, 1999, 451 pp., $79.95.

- Cited by None

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychiatr Psychol Law

- v.28(5); 2021

Reframing criminal profiling: a guide for integrated practice

Wayne petherick.

a Criminology Department, Faculty of Society and Design, Bond University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

Nathan Brooks

b School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

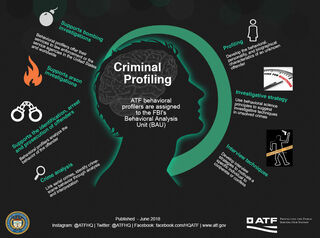

Profiling aims to identify the major personality and behavioural characteristics of offenders from their interactions in the crime. The discipline has undergone numerous changes and advances since its first modern use by the psychological/psychiatric community. The current paper reviews the different approaches to criminal profiling, exploring the reasoning and justification utilised across profiling practices. Profiling aims to assist criminal investigators; however, the variance in profiling approaches has contributed to inconsistency across the field, bringing the utility of profiling into question. To address the current areas of practice deficit in criminal profiling, a framework is proposed to promote integrated practice. The CRIME approach provides a framework (consisting of crime scene evaluations, relevancy of research, investigative or clinical opinions, methods of investigation, and evaluation) to promote structure and uniformity in profile development, aiming to assist in the reliability of the practice by providing an integrative framework for developing profiles.

In its most basic form, criminal profiling (also known as offender profiling and behavioural profiling, among others) is an investigative tool to discern offender characteristics from behaviour. This base understanding is common to most, if not all, approaches to profiling, with the main difference between practices being the reasoning and decision-making processes used to arrive at the final profile (Petherick, 2014a , 2014b ). Despite the level of scientific reasoning being notably different across the approaches, there has been little attempt to understand what this reasoning is and how it impacts on profile content. Profiling has been subject to discrepancies across practice, with a dearth of processes or principles to promote integrated practice. There have, however, been many attempts to understand more advanced aspects of profiling such as the accuracy of one group over another (Kocsis et al., 2000 ; Pinizzotto & Finkel, 1990 ), or the assistance offered by profilers to end consumers (Cole & Brown, 2011 ; Copson, 1995 ), mental health professional’s attitudes to profiling (Torres et al., 2006 ) and the operational utility of offender profiling (Gekoski & Gray, 2011 ).

Criminal profiling details the characteristics of the likely perpetrator of a given crime. Far from having an abstract relationship to criminal profiling, logic is pivotal to constructing rational and robust arguments about offender characteristics, not only in the profile itself but also in the communication of the elements of the profile to consumers. Indeed, devoid of any logical process, conclusions about the offender remain nothing more than unfounded assumption or ill-informed guesswork. The type of logic reasoning employed by the profiler is the most fundamental difference between approaches, and it is critical to consider the different types of reasoning employed across profiling practices. Logic, the process of argumentation, is defined by Farber ( 1942 , p. 41) as ‘a unified discipline which investigates the structure and validity of ordered knowledge’. Further, according to Battacharyya ( 1958 , p. 326):

Logic is usually defined as the science of valid thought. But as thought may mean either the act of thinking of the object of valid thought, we get two definitions of logic: logic as the science (1) of the act of valid thinking, or (2) of the objects of valid thinking.

Stock ( 2004 , p. 8) adopts a different approach:

Logic may be declared to be both the science and the art of thinking. It is the art of thinking in the same sense that grammar is the art of speaking. Grammar is not in itself the right use of words, but a knowledge of it enables men to use words correctly. In the same way a knowledge of logic enables men to think correctly or at least to avoid incorrect thoughts. As an art, logic may be called the navigation of the sea of thought.

It is the purpose of logic to analyse the methods by which valid judgements are obtained in any science or discourse, which is met by the formulation of general laws dictating the validity of judgements (Farber, 1942 ). More than simply providing a theoretical framework for structuring arguments, the basic principles of logic allow for a more rigorous formulation and testing of any argument. A better understanding of this theoretical framework provides a better understanding of the processes employed by the profiler, as well as the discipline itself. Additionally, the difference in the ways that profiles are argued is of great practical importance (Goldsworthy, 2001 , p. 30):

One important factor that should be considered is how acceptable the method of profiling is to those who will be using the profile. . . . Like any product, the profile must be end-user friendly. Few law enforcement personnel have qualifications in psychology or related disciplines, and it is this very fact that can make investigators dubious as to how conclusions presented in the profile were reached. For instance, a claim that a particular type of serial murderer will be 40 years old, white and a blue collar worker will be treated with derision by investigators unless it can be shown how that conclusion was reached, and further that the conclusion is likely to be true.

Goldsworthy argues two key points: first, that logic and reasoning should be employed in the construction of the profile, and, second, that the logic and reasoning employed be clearly elucidated throughout. While it should stand to reason that logic and reasoning should be used in profiling, we use the term in a more formal sense to move the process away from such idiosyncrasies as ‘intuition’ or ‘common sense’.

There are primarily three types of logic used in developing profiles: induction, abduction and deduction. Rather than representing different types of logic, these are best thought of as different points along the logical continuum, beginning with various hypotheses about what may have occurred or that may be true (induction), and through the scientific method we falsify each conclusion until we are left with the best possible explanation (abduction) or only one that is based on universal laws or principles and cannot be falsified (deduction). Sometimes, because of the nature of human behaviour, evidence dynamics or active attempts to thwart the investigation (referred to as staging, among others), we are left with the best explanation for the evidence we are observing – that is, abduction.

An inductive argument is where the conclusion is likely or a matter of probability based on supporting premises, such as physical evidence or research. While a good inductive argument provides strong support for the conclusion, the argument is still not infallible. For example, in research on behavioural consistency, Bateman and Salfati ( 2007 ) found that hiding the body occurred 67.8% of the time, and that moving the body after the homicide occurred in 61.1% of the time. While cited as high-frequency behaviours, these results suggest that each will only be found approximately two thirds of the time. As a result, investigators using a profile that reports such statistical inferences may equate probability with certainty. However, these behaviours occur in some cases and not others, raising an issue with both the utility of this information and in determining where offending behaviour is consistent and inconsistent with research. This may be especially true in cases where the level of certainty is communicated in a vague or general way, such as ‘most of the time the body will be hidden’. While technically true, this argument does not communicate the exact level of certainty.

Induction proceeds from a specific set of observations to a generalisation known as a premise, and the premise is a working assumption (Thornton, 1997 ). From observations in each case, comparisons are made to determine the level of similarity to past cases sharing similar features. These similarities provide generalisations that may then be offered as a conclusion in the current case. For example, a woman is found murdered, and a generalised conclusion is reached that the suspect is likely to be male, due to male offenders perpetrating between 85–90% of homicides (Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], 2002 ; Mouzos, 2005 ). The central premise in induction is similarity, where analysis of unlawful activity reveals that criminal activity often has common features (Navarro & Schafer, 2003 ). The application of inductive logic where the similarity is drawn from research on criminal behavioural patterns can be appreciated through the following (Kocsis, 2001 , p. 32):

To use this model to produce a psychological profile, behaviours from any of the [behaviour] patterns are compared and matched with those of the unsolved case. Once a behaviour pattern has been matched with the unsolved case it can be cross referenced with offender characteristics.

Abduction is a style of reasoning that could be summed up as reasoning to the best explanation (Davis et al., 2018 ). That is, the evidence in a case is more indicative of a single hypothesis from a number of possible hypotheses, though not inclusive of one to the exclusion of all others. According to Niiniluoto ( 1999 ) this type of reasoning has been the staple heuristic method of classical detective stories, and ‘the logic of the “deductions” of Sherlock Holmes is typically abductive’ (p. S441).

Deduction relies on induction, where hypotheses are drawn based on case similarities and are then tested against the evidence in the current case. Offender characteristics are arrived at through a systematic study of the patterns and themes present in the physical and behavioural evidence, where if the premise is true, the conclusion must also be true (Bevel & Gardner, 2008 ). Neblett ( 1985 , p. 114) goes further, stating that ‘ if the conclusion is false, then at least one of the premises must be false ’. For this reason, when employing a deductive approach, it is incumbent on the profiler to establish the validity of each and every premise before drawing conclusions from them.

Because a deductive argument is structured so that the conclusion is implicitly contained within the premise unless the reasoning is invalid, the conclusion will follow as a matter of course. Put another way, a deductive argument is designed to go from truth to truth. A deductive argument will therefore be valid if (Alexandra et al., 2002 , p. 65):

- It is not logically possible for the conclusions to be false if the premises are true.

- The conclusions must be true, if the premises are true.

- It would be contradictory to assert the premises yet deny the conclusions.

In profiling, deduction relies upon the scientific method which is a ‘reasoned step by step procedure involving observations and experimentation in problem solving’ (Bevel, 2001 , p. 154). Induction, abduction and deduction relying on the scientific method go hand-in-hand in criminal profiling: theories are developed based on research and experience (induction), which are then examined in light of the current case to determine which may or may not be true given the available evidence (abduction), and attempts are then made to falsify those that remain through hypothesis testing and revision (the scientific method that in ideal scenarios would lead to deduction). Only when theories have withstood this process of falsification can they be considered complete, and that a truth has been determined.

While there is no conclusive data on the commonality and occurrences of profiling practices, it would make reasoned sense to suggest that induction is the most common, given that many approaches rely on statistics or case experience in developing the final profile. Furthermore, induction is the foundation for both abduction and deduction. Owing to the nature of crime scenes and criminal behaviour and the lack of universal principle in human behaviour overall, deduction would be considered the least common type of reasoning, making abduction second by default. Although deduction is concerned with absolutes, abduction centres on probable reasoning derived through hypothesis testing. Hence, in abductive reasoning, conclusions are reached without the reliance on a definitive cause, instead determined based on the likelihood, feasibility and practicality of a given hypothesis. According to Niiniluoto ( 1999 ), in consideration of Pierce’s ( 1898 ) position on an abductive argument, the following is concluded (p. S439):

- The surprising fact C is observed.

- But if A were true, C would be a matter of course.

- Hence, there is reason to suspect that A is true.

The use of abductive reasoning is common practice in the clinical process of differential diagnosis, along with providing the underpinnings for crime assessment and profile development (Davis et al., 2018 ; Rainbow & Gregory, 2011 ). As Davis et al. ( 2018 ) observed, ‘profilers should take time to argue against their opinions and consider alternate hypotheses (p. 187–206). Consequently, the current review intends to examine the reasoning and decision making employed across offender profiling. The major profiling practices are discussed, and the utility of these approaches explored. As noted by Fox and Farrington ( 2018 ), ‘there appears to be substantial variation in what is considered to be OP [offender profiling], who is conducting it, the methodology and approach that is used, the findings that are achieved, as well as where and how the results are presented’ (p. 1248). The significant differences amongst approaches to offender profiling, along with widespread disputes between practitioners, have greatly impeded the field (Fox et al., 2020 ). These limitations have caused scepticism about the investigative utility of profiling, along with the scientific efficacy of the practice (Fox et al., 2020 ). For offender profiling to have scientific validity and more widespread recognition in investigations and admissibility in court, a uniformed approach to practise remains essential (Fox & Farrington, 2018 ; Freckelton, 2008 ). The current review contends that for profiling to be recognised as a scientific and evidence-based tool, homogeny in practice must be achieved, best viewed through an integrative approach to offender profiling.

Profiling approaches

While there is considerable overlap between practitioners and how they approach the development of a profile, there are also significant differences. Whether these constitute enough to be considered different methodologies is currently a subject of debate, with some suggesting that differences are more about emphasis on various parts of the process (Davis et al., 2018 ).

Criminal investigative analysis

Owing to its depiction in film and television, perhaps the best known profiling approach would be that developed by the FBI. Criminal investigative analysis, or CIA, is inductive and abductive with its roots in early law enforcement attempts to understand patterns of criminal behaviour. Early CIA thinking allocated offenders to one of two types: The organised asocial and the disorganised nonsocial, with these terms first appearing in The Lust Murderer in 1980 (see Hazelwood & Douglas, 1980 ). Between 1979 and 1983, FBI agents interviewed offenders in federal custody (see Burgess & Ressler, 1985 ) to formalise this taxonomy and determine whether there were consistent features across offences that may be useful in classifying future offenders (Petherick, 2014a ). At these early stages, the FBI method employed this organised/disorganised typology as a decision process model, which classifies offenders by virtue of the level of sophistication, planning and competence evident in the crime scene. According to the study’s authors, ‘the agents involved in profiling were able to classify murders as either organised or disorganised in the commission of their crimes ’ further noting that ‘ because this method of identifying offenders was based largely on a combination of experience and intuition, it had its failures as well as its successes’ (Burgess & Ressler, 1985 , p. 3). Indeed, the study’s two quantitative objectives were to first identify whether there are crime scene differences between organised and disorganised murderers and second to identify variables that may be useful in profiling sexual murderers for which organised and disorganised murderers differ. However, Douglas et al. ( 1986 ), acknowledged that profile development did not solely rely on a classification of organised or disorganised, explaining that profiles are derived through ‘the classification of the crime, its organised/disorganised aspects, the offender’s selection of a victim, strategies used to control the victim, the sequence of the crime, the staging (or not) of the crime, the offender’s motivation for the crime and the crime scene dynamics’ (p. 412).

An organised crime is one with evidence of planning, where the victim is a targeted stranger, where the crime scene reflects overall control, restraints are used, and there are aggressive acts prior to death. This suggests the offender is organised with the crime scene being a reflection of personality; they will generally be above average intelligence, be socially competent, prefer skilled work, have a high birth order, have a controlled mood during the crime, and are more likely to use alcohol (Douglas & Burgess, 1986 ; Ressler et al., 1992 ). Conversely, a disorganised crime shows spontaneity, where the victim or location is known, the crime scene is random and sloppy, there is sudden violence, minimal restraints are used, and there are sexual acts after death. This is again suggestive of the personality of the offender, with a disorganised offender being below average intelligence and socially inadequate, and having lower birth order, anxious mood during the crime and minimal use of alcohol or drugs (Douglas & Burgess, 1986 ; Ressler et al., 1992 ). Despite having discrete classifications, it is generally acknowledged that no one offender will fit so neatly into either type, with most being categorised as ‘mixed’ – that is, having elements of both types. The FBI dichotomy has received criticism from some practitioners (Canter et al., 2004 ; Canter & Heritage, 1990 ; Canter & Youngs, 2003 ), and there have been limited empirical findings published by the FBI in relation to practice changes (Fox & Farrington, 2018 ). One exception to this was the study conducted by Morton et al. ( 2014 ), who observed that ‘Dichotomous typologies by their very nature have challenges, as an “either/or” choice, cannot possibly explain complex, multiple event human interactions’ (p. 5). Further to this, Morton and colleagues suggested that profiling should serve as a tool that provides law enforcement investigators with investigative information, rather than providing classifications from predetermined categories or cumbersome typologies.

Diagnostic evaluations

Diagnostic evaluations do not represent a single profiling method per se but are instead a generic description of the services offered by mental health professionals, and largely rely on clinical judgement (Bradley, 2003 ). The profile provided by psychiatrist Dr James Brussel in 1956 to assist in the ‘Mad Bomber’ case is by far the most famous example of this approach to profiling (Brussel, 1968 ). In the early stages of profiling, the diagnostic and clinical approach occurred on an as-needed basis (Wilson et al., 1997 ), usually as one part of a broad range of psychological services. The contribution of mental health experts to investigations took shape when various police services asked whether clinical interpretations of unknown offenders might help in identification and apprehension (Canter, 1989 ). Even though other methods have come to the fore, largely eclipsing these early contributions, at the time of publication, Copson ( 1995 ) claimed that over half of the profiling done in the United Kingdom was by psychologists and psychiatrists using a clinical approach. In an early study of the range of services offered by police psychologists, Bartol ( 1996 ) found that, on average, 2% of the total monthly workload of in-house psychologists was spent on profiling, and that 3.4% of the monthly workload of part-time consultants was spent on profiling. Interestingly, despite diagnostic evaluations being among the earliest approaches, research on the attitudes of clinical practitioners revealed scepticism of profiling as a whole. For example, Bartol ( 1996 ) found that 70% of those questioned did not feel comfortable giving this advice, and felt that the practice was questionable. What is more (Bartol, 1996 , p. 79):

One well-known police psychologist with more than 20 years of experience in the field, considered criminal profiling ‘virtually pointless and dangerous’. Many of the respondents wrote that much more research needs to be done before the process becomes a useful tool.

Torres et al. ( 2006 ) show similar disdain for the practice. Of the 161 survey respondents, 10% had profiling experience, and 25% considered themselves knowledgeable of the practice. Less than 25% considered the practice to have sufficient scientific reliability or validity. However, despite this, many respondents also considered profiling a useful tool for law enforcement. In examining their role in profiling, McGrath ( 2001 , p. 321) suggests that clinicians may be well suited to the profiling process, owing to the following reasons:

- Their background in the behavioural sciences and their training in psychopathology place them in an enviable position to deduce personality and behavioural characteristics from crime scene information.

- The forensic psychiatrist is in a good position to infer the meaning behind signature behaviours.

- Given their training, education, and focus on critical and analytical thinking, the forensic psychiatrist is in a good position to ‘channel their training into a new field’.

Despite supporting this role, McGrath ( 2001 ) also notes that the clinician should be careful not to get caught up in, or focus too heavily on, treatment issues. This role confusion may come about because those conducting diagnostic evaluations may not often be exposed to the needs and wants of investigations, having little experience in reviewing crime scene data or witness depositions (West, 2000 ). However, the diagnostic evaluation approach to profiling has largely changed since these empirical studies were conducted during the 1990s through to the early 2000s. There has been an uprising in specialised police roles requiring registration as a psychiatrist or psychologist along with knowledge or experience in law enforcement investigations (e.g. see below a description of behavioural investigative advice). Consequently, the clinical and diagnostic approach to profiling is now embedded in specialised police positions, rather than in general forensic psychology and psychiatry practice.

Investigative psychology

Investigative psychology (IP) employs scientific research and is largely dependent on the empirical analysis conducted on individual crime types. Because IP relies more on empirical research than other inductive methods, strengths of this approach to practice are evident. However, a considerable issue in the use of applying this process to developing a criminal profile is the potential variance that may arise between profilers in determining the details of the crime and the applicability of relevant or suitable research. Furthermore, reliance on research may mean that crimes of extreme violence or low frequency may not be adequately researched to base a profile on. As with CIA, IP identifies profiling as only one part of an overall approach (Canter, 2000 , p. 1091):

The domain of investigative psychology covers all aspects of psychology that are relevant to the conduct of criminal and civil investigations. Its focus is on the ways in which criminal activities may be examined and understood in order for the detection of crime to be effective and legal proceedings to be appropriate. As such, investigative psychology is concerned with psychological input to the full range of issues that relate to the management, investigation and prosecution of crime.

Canter ( 2011 ) discussed the action–characteristics equation, whereby crime scene actions are followed by a process of deriving inferences, resulting in the identification of offender characteristics. The stage of inference development employs empirical procedures and a conceptually driven approach to establish actions and characteristics. The inference process seeks to examine interpersonal style, emotions, intellect, knowledge and familiarity, and skills. Upon analysis, conclusions are provided regarding the salience of the crime, case linkage, offender characteristics and based location. At the cornerstone of the IP approach to profiling is advanced statistical modelling and facet theory, forming both the empirical and conceptual approaches to IP practice (Canter & Youngs, 2003 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). However, although IP empirical research has provided a substantial contrition to profiling and investigating the nuanced aspects of offending, there is contention in regard to whether IP constitutes an individual approach to profiling, or instead an essential step in the provision of a profile (Davis et al., 2018 ; Rainbow et al., 2014 ; Snook et al., 2010 ).

Behavioural evidence analysis

The literature on behavioural evidence analysis (BEA) identifies that when rigorously applied to a criminal investigation the method aims to be largely deductive in nature; however, it should be noted than an absence of universal principles in the behavioural sciences renders this more an ideal than a reality. Additionally, given the reliance of deductive logic on inductive theories and the scientific method, it would be wrong to classify the method as wholly deductive. The theory of BEA states that conclusions about the offender should not be rendered unless specific physical evidence (based on a detailed crime reconstruction) exists. In BEA, the profiler spends a great deal of time establishing the veracity and validity of the physical evidence and its relationship to the criminal event. Indeed, this focus on detail is listed by some as a problem with the practice, specifically that deductive approaches are time consuming and provide limited information to investigators (see Holmes & Holmes, 2002 ).

Like many approaches, BEA is composed of steps or stages. The first, forensic analysis , refers to the examination, testing and interpretation of any and all physical evidence (Petherick & Turvey, 2008 ). To be able to understand any behavioural evidence, a full and complete reckoning of the physical evidence must be undertaken. Victimology , the second stage, examines any and all victim-related information such as height, sex, age, hobbies, habits and routines. Information derived during this stage can also help determine victim risk and target selection. Crime scene characteristics seeks to establish the distinguishing features of the crime scene, including the method of approach and attack, the method of control, location type, nature and sequence of any sexual acts, materials used, precautionary acts and verbal activity (Petherick & Turvey, 2008 ).

Offender characteristics , the final stage, assesses all of the above information for themes that collectively suggest personality or behavioural characteristics of the offender. In contrast to other approaches, BEA proposes a smaller number of characteristics that can be definitively established, including knowledge of the victim, knowledge of the crime scene, knowledge of methods and materials, criminal skill and motive (see Petherick, 2014a ).

Behavioural investigative advice

In the early 2000s, a new method of supporting police investigation known as behavioural investigative advice (BIA) emerged in the United Kingdom. The BIA discipline seeks to offer a broad range of psychological and scientific assistance to police investigations, including, but not limited to offender profiling (Rainbow et al., 2014 ). The role of BIAs is to offer senior investigative officers extra support and enhance their decision making during serious crime investigations through the use of behavioural science theory, research and expertise (Davis et al., 2018 ). The use of BIAs to assist investigations is considered to be positive and an essential step in incorporating specialised expertise into policing. However, in considering offender profiling, it is unclear as to the processes that BIAs use in assisting investigations and developing profiles. It would seem that BIA is a distinct profession, rather than a variation in profiling practice (Davis et al., 2018 ). Although research presented by BIAs has proposed the use of decision-making models (see Alison et al., 2003 ) to reach profile conclusions, the standards of evidence required for a BIA to develop a profile appears varied. An example of the decision making employed in BIA profiles was provided by Alison et al. ( 2003 ) who proposed the application of Toulmin’s ( 1958 ) philosophy of argument. The principles of applying this structure of argument to profiling was due to ‘the need for the justificatory functioning of substantive argument, whilst also being aware of the limitations of formal deductive, decontextualized logic for practical, ‘real world’ issues’ (Alison et al., 2003 , p. 174). In applying these principles to derive a profile, a profile statement must be derived from backing, warrant, grounds, modality and the consideration of rebuttal. The application of structured argument and evidence-based consideration in a profile is considered to be paramount to scientific practice and demonstrates support for the BIA discipline. BIA appears to be a progressive approach to criminal profiling and has received empirical recognition through a developing body of research (Alison et al., 2010 ; Almond et al., 2011 ; Marshall & Alison, 2011 ). For example, studies have reported positive police satisfaction with BIA involvement in cases and recommendations (Almond et al., 2011 ; Cole & Brown, 2011 ). The development of BIA practice is considered promising for both profiling and investigative assistance; however, the discipline would benefit from further scientific scrutiny in relation to operational approaches. The use of principles to derive a structured argument is essential in profiling, yet the development of a supported argument is only part of the required decision-making processes for producing a profile, with considerable degree and variation possible without a standardised practice framework. BIA is a progressive discipline, although subject to fallibility without process prioritisation and practice uniformity.

Towards integrated practice in criminal profiling

The variation across profiling practices has resulted in inconsistencies emerging in relation to the reliance on evidence, conclusions provided and the investigative utility of profiles (Almond et al., 2011 ; Fox et al., 2020 ). This has ranged from profiles providing statements without justification or the possibility of falsification, being derived predominantly on research conclusions, dismissing inconsistencies in a case, preferencing typology characteristics, omitting victimology evidence, selectively reporting confirmatory evidence, being provided verbally and without documentation, and failing to evaluate all case materials (Almond et al., 2011 ; Morton et al., 2014 ; Petherick & Brooks, 2014 ; Petherick & Ferguson, 2010 ; Turvey, 2012 ; Wilson et al., 1997 ). Each approach is characterised by strengths and weakness. For example, the linking of crime scene evidence with valid conclusions as evident in the BEA method provides scientific efficacy; however, this method can also be limiting, offering a narrow profile and minimal investigate assistance. According to Alison et al. ( 2003 ), the success of a profile is dependent on the types of conclusions provided, rather than the method used to derive these. For substantiated conclusions in profiles, there must be evidence of logical argument and pragmatic utility, ensuring conclusions are both logical and practical (Alison et al., 2010 ; Almond et al., 2011 ). Any conclusion/statement provided in a profile must have grounding, warrant, veracity and the capacity for falsification consistent with principles of the structure of argument (Toulmin, 1958 ). The grounding of the argument must be supported by scientific knowledge, whilst the warrant of the argument must permit this to be demonstrated in specialised research. In relation to veracity, there must be a form of specification in regard to the likelihood or probability of the claim occurring, whilst falsification must be possible, ensuring that that the statement or claim can be tested or disproven (Alison et al., 2003 ; Toulmin, 1958 ). Along with the profiles being derived from evidence and grounded in logical conclusions, statistical regularities between the types of offence and the types of offender characteristics can offer further investigative utility (Fox et al., 2020 ). As Fox and Farrington ( 2018 ) state, ‘all future profiles should be developed using a solid empirical approach that relies on advanced statistical analysis of large data sets’ (p. 1263). Consequently, it appears that the discipline of criminal profiling would benefit from an integrated approach to practice that provides a framework for the provision of profiles. An integrated framework serves to support the strengths of each methodology, whilst providing a structured guide to profile development. The current issues pertaining to profiling are akin to the limitations identified with the early generation of psychological risk assessments, with a need to integrate empirical findings, practitioner expertise and processes of practice. The issues in the field of risk assessment resulted in adjustments to practice and the development of a new generation of assessment instruments known as structured professional judgments (SPJs; Cooper et al., 2008 ; Davis & Ogloff, 2008 ; Gormley & Petherick, 2015 ). The introduction of SPJs has permitted an integrative approach to risk assessment, assimilating the scientific basis of the actuarial approach along with the benefits of the clinical approach. In accordance with the need for integrated practice in criminal profiling, a structural framework is proposed, represented by the acronym CRIME. The CRIME framework seeks to overcome the pitfalls of singular profiling approaches and instead provide a structured framework for profile development, incorporating the strengths of each of the examined practices, whilst acknowledging the limitations and weakness of utilising a specific process. This framework is similar to other recommendations and is based upon a similar philosophy to that of at least the works of Davis and Bennett ( 2016 ) and Ackley ( 2017 ).

- C – Crime scene evaluations

- R – Relevancy of research

- I – Investigative or clinical opinion

- M – Methods of investigation

- E - Evaluation

The CRIME framework is centred on a tiered process of profile development. The first tier, crime scene evaluations , relies largely on the crime scene and the evidence present to determine justifications. Consistent with a BEA approach, conclusions cannot be reached without the presence of evidence at the crime scene indicating that a set behaviour or event has occurred. This tier is considered to carry primary significance in the profile, accompanied by the other tiers, which provide additional information of assistance to investigations. At this first phase, evaluations are determined in respect to crime scene evidence, victimology and offender behaviour. The second tier, relevancy of research , is intended to provide investigators with an overview of research on similar offending behaviour, noting factors of relevance in similar crimes and characteristics that have been found on these occasions. This step must specify the limitations of relying on this research and instead seek to provide education and background on the offending matter. The third tier, investigative or clinical opinion , is considered to carry less weight and should be included in profiles with caution. This may include investigators’ unique understanding of factors such as access of local areas, criminal trends or past victim patterns. These factors are provided in the profile as suggestions and knowledge that may be of note for investigators to consider and review during the investigative processes. This information is considered of lower investigative relevance and not based in fact. The penultimate stage and tier of the CRIME framework is methods of investigation . This stage aims to provide detailed implications arising from the aforementioned steps, indicating avenues for investigators to explore and offering techniques of investigation and advice in relation to the suspect. The final stage is evaluation , and involves a critical examination of the profile itself, the logic, reasoning and sequencing used to arrive at the profile, and any input the investigators have about the document. This also includes an evaluation of the profile in light of new information or evidence that has come to light since the profile was generated, along with a peer review of the profile before this is provided to the consumer.

An example of the application of the CRIME framework to the below scenario (adapted from Aydin & Dirilen-Gumus, 2011 , p. 2615–2616; Douglas et al., 1986 , p. 416) is as follows:

At 3.00 pm a young woman’s nude body was discovered on the roof top of an apartment building where she was living. The female had been extensively beaten to her face, and she had been strangled with the bag strap that belonged to her purse. Her nipples had been cut off after her death, and these had been placed on her chest. On the inside of her thigh in ink, were the words, ‘You can’t stop me’. On her abdomen, the words, ‘Fuck you’ were scrawled on this section of her body. The pendant that was usually worn by the woman, a Jewish sign (Chai) for good luck, was missing from around her neck. The missing pendant was presumed taken by the murderer. Her nylon stockings had been removed and loosely tied around her wrists and ankles near a railing, with her underpants pulled over her face. The crime scene revealed that the victim’s earrings that she had been wearing were placed symmetrically on either side of her head. An umbrella and ink pen had been inserted into the woman’s vagina and a hair comb was placed into her pubic hairs. Her jaw and nose had been broken, her molars were loosened, and due to the blunt force trauma, she had sustained multiple face fractures. The cause of death was determined to be asphyxia by ligature (purse strap) strangulation. There were also post-mortem bite marks on the victim’s thighs, along with several contusions, haemorrhages and lacerations to the body. The killer had defecated on the roof top and this was covered with the victims’ clothing.

The preliminary police reports revealed that another resident of the apartment building, a white male, aged 15 years, had discovered the victim’s wallet. The young male discovered the wallet in the stairwell between the third and fourth floors at approximately 8.20 am, keeping the wallet with him until he returned home from school for lunch that afternoon. Upon returning home, he gave the wallet to his father, a white male, aged 40 years. After receiving the wallet, the father went to the victim’s apartment at 2.50 pm and handed this to the victim’s mother whom she resided with. The mother contacted the day-care centre to inform her daughter about the wallet; however, upon contacting the centre, she learnt that her daughter had not appeared for work that morning. The mother, the victim’s sister and a neighbour began searching the building. Shortly afterwards they discovered the body, and the neighbour called the police. Initial investigations by police revealed that no witnesses had seen the victim after she left her apartment that morning.

The investigation revealed that the victim was a 26-year-old, 4′11″, 90-lb, white female. The victim resided with her mother and father in the apartment building. She awoke around 6.30 am on the day of her murder, dressed, had breakfast (consisting of coffee and juice) and left for work. The woman worked at a near-by day-care centre, where she was employed as a group teacher for handicapped children. When she would leave for work in the morning, she would often alternate between taking the elevator or walking down the stairs, depending on her mood. She had a slight curvature of the spine (kyphoscoliosis) and was a shy and quiet woman. The medical examiner’s report revealed that there was no semen in the victim’s vagina, but semen was detected on the victim’s body. There were visible bite marks on the victim’s thigh and knee area and the murderer had cut the victim’s nipples with a knife after she was deceased and written on her body. The stab wounds that she had sustained were not deep. The examination concluded that the cause of death was strangulation, first manual, then ligature, with the strap of her purse.

While the challenges of developing a profile based on a short scenario are evident, the outline in Table 1 of the integrated CRIME framework details a summary of how the steps may be initially formed and subsequently utilised. The profile should start with an overview of the crime and the details, before integrating the CRIME steps. Upon completion of the five steps, the practitioner producing the profile should summarise the information and provide a review of the importance of the information provided within the profile, again emphasising the reliance of evidence-based information in the profile, from both the standing research corpus and crime scene evidence.

CRIME profile development.

Not only is this approach useful for providing as holistic an understanding of the case as possible, undertaking the CRIME framework may also serve as a bootstrapping process for other types of advice investigators may request as a natural extension of the assistance. For example, having a deep understanding of the crimes of a serial criminal may assist with the process of case linkage where one attempts to link previously unlinked cases to one offender or offender group. Similarly, the profiler/analyst may be able to provide insight into risk assessment of a serial or other offender to determine the likelihood that they will escalate or graduate to other crimes, such as from a sex offender to a killer.

Recommendations and conclusion

For profiling to develop as a discipline, greater scientific rigor is required, with profiles needing to incorporate logic and reasoning that are supported by appropriate evidence and justification. Criminal profiling must have investigative utility, assisting investigations, rather than creating confusion or misleading cases. Secondly, for profiling to advance there must be a move towards scientific practice, with uniformity across the field essential for admissibility in court (Freckelton, 2008 ) should the profiler/analyst be appropriately qualified for such endeavours. Although profiling is intended to develop investigative hypotheses, given the progression towards evidence-based policing, some proponents have suggested that for profiling to constitute a scientific method, court and legal admissibility is essential (Bosco et al., 2010 ; Freckelton, 2008 ; Petherick & Brooks, 2014 ). Currently, profiling regularly fails to add probative value to cases, and instead is considered to have a greater prejudicial effect (Bosco et al., 2010 ). One of the central challenges to profiling meeting admissibility standards in courts has been due to the inconsistencies in practice, with large discrepancies observed across approaches and methods of practice. The reliance on singular methods appears largely problematic, failing to consider the strengths of other profiling modalities, while also exposing investigations to the fragility of a sole method approach.

For profiling to develop as a forensic science and ultimately have admissibility in court, the discipline must be reliable, subject to peer review and scientific publication, be generally accepted amongst fellow practitioners, have guiding or governing standards, have identifiable error rates, and be implemented only in appropriate and applicable cases (Bosco et al., 2010 ). Subsequently, it is proposed that a joint methodology be employed when constructing criminal profiles, focusing on the strengths of each profiling approach and establishing uniformity in practice standards. It is suggested that this approach form the CRIME framework, consisting of crime scene evaluations, relevancy of research, investigative or clinical opinions, methods of investigation and evaluation. The CRIME approach provides a framework to promote the scientific practice of profiling, aiming to assist in the reliability of the practice by detailing a standardised process of developing profiles. It is intended that through the CRIME framework profiles will encompass error rates, specified in the crime scene evaluation and relevancy of research stages, whilst the evaluation stage seeks to incorporate peer review and consultation into practice. For profile to continue as a discipline, systemisation and evidence-based practice is required. Although the CRIME framework is not the ultimate solution to developing a ‘gold standard’ in criminal profiling, the approach seeks to promote integration and unity in practice, an essential first step in establishing practice consistency. It is recommended that future research seek to explore the benefit of profiles derived through the framework, reviewing the consistency and emergence of evidence-based practice. This could be investigated through police satisfaction, profile accuracy and the evidence of reasoning underpinning profiles derived through the CRIME framework. The future of profiling is dependent on the discipline progressing towards science, and integrated practice is the first fundamental step (Fox & Farrington, 2018 ).

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest.

Wayne Petherick has declared no conflicts of interest

Nathan Brooks has declared no conflicts of interest

Informed consent

The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

- Ackley, C. N. (2017). Criminal investigative advice: A move toward a scientific, multidisciplinary model. In Van Haselt V. B. & Bourke M. L. (Eds.), Handbook of behavioural criminology (pp. 215–238). Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alexandra, A., Matthews, S., & Miller, M. (2002). Reasons, values, and institutions . Tertiary Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alison, L., Smith, M. D., Eastman, O., & Rainbow, L. (2003). Toulmin’s philosophy of argument and its relevance to offender profiling . Psychology, Crime & Law , 9 , 173–183. doi: 10.1080/1068316031000116265 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alison, L., Goodwill, A., Almond, L., van den Heuvel, C., & Winter, J. (2010). Pragmatic solutions to offender profiling and behavioural investigative advice. Legal and Criminological Psychology , 15 (1), 115–132. doi: 10.1348/135532509X463347 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Almond, L., Alison, L., & Porter, L. (2011). An evaluation and comparison of claims made in behavioural investigative advice reports compiled by the National Policing Improvement Agency in the United Kingdom. In Alison L., Rainbow L., & Knabe S. (Eds.), Professionalising offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aydin, F., & Dirilen-Gumus, O. (2011). Development of a criminal profiling instrument . Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences , 30 , 2612–2616. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartol, C. R. (1996). Police psychology: Then, now and beyond . Criminal Justice and Behaviour , 23 ( 1 ), 70–89. doi: 10.1177/0093854896023001006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Battacharyya, S. (1958). The concept of logic . Philosophy and Phenomenological Research , 18 ( 3 ), 326–340. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bateman, A. L., & Salfati, C. G. (2007). An examination of behavioral consistency using individual behaviors or groups of behaviors in serial homicide . Behavioral Sciences & the Law , 25 ( 4 ), 527–544. doi: 10.1002/bsl.742 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevel, T. (2001). Applying the scientific method to crime scene reconstruction . Journal of Forensic Identification , 51 ( 2 ), 150–165. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevel, T., & Gardner, R. M. (2008). Bloodstain pattern analysis with an introduction to crime reconstruction (3rd ed.). CRC Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bosco, D., Zappalà, A., & Santtila, P. (2010). The admissibility of offender profiling in courtroom: A review of legal issues and court opinions . International Journal of Law and Psychiatry , 33 ( 3 ), 184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.03.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradley, P. (2003). Criminal profiling: What’s it all about? Inpsych. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brussel, J. A. (1968). Casebook of a crime psychiatrist . Bernard Geis Associates. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burgess, A. W., & Ressler, R. K. (1985). Sexual homicides: Crime scene and pattern of criminal behaviour . National Institute of Justice Grant 82-IJ-CX-0065, US Department of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=98230 .

- Canter, D. (1989). Offender profiles . The Psychologist , 2 ( 1 ), 12–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. (2000). Investigative psychology. In Siegel J., Knupfer G., & Saukko P. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of forensic science . Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V. (2011). Resolving the offender “Profiling equations” and the emergence of an investigative psychology . Current Directions in Psychological Science , 20 ( 1 ), 5–10. doi: 10.1177/0963721410396825 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V., Alison, L. J., Alison, E., & Wentink, N. (2004). The organized/disorganized typology of serial murder: Myth or model? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law , 21 , 293–320. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V., & Heritage, R. (1990). A multivariate model of sexual offence behaviour: Development in “offender profiling”: I . The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry , 1 ( 2 ), 185–212. doi: 10.1080/09585189008408469 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V., & Youngs, D. (2003). Beyond ‘offender profiling’: The need for an investigative psychology. In Carson D. & Bull R. (Eds.), Handbook of psychology in legal contexts (2nd ed., pp. 171–205). Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole, T., & Brown, J. (2011). What do senior investigative police officers want from behavioural investigative advisers. In Alison L., Rainbow L., & Knabe S. (Eds.), Professionalising offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper, B. S., Griesel, D., & Yuille, J. C. (2008). Clinical-forensic risk assessment. The past and current state of affairs . Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice , 7 ( 4 ), 1–63. doi: 10.1300/J158v07n04_01 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Copson, G. (1995). Coals to Newcastle? Part 1: A study of offender profiling. Police Research Group Special Interest Paper 7 . Home Office. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M. R., & Bennett, D. (2016). Future directions for criminal behaviour analysis of deliberately set fire events. In Doley R. M., Dickens G. L., & Gannon T. A. (Eds.), The psychology of arson: A practical guide to understanding and managing deliberate firesetters (p. 131–146). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M. R., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2008). Risk assessment. In Fritzon K. & Wilson P. (Eds.), Forensic psychology and criminology: An Australian perspective (pp. 141–164). McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M., Rainbow, L., Fritzon, K., West, A., & Brooks, N. (2018). Behavioural investigative advice: A contemporary commentary on offender profiling activity. In Griffiths A. & Milne R. (Eds.), The psychology of criminal investigation: From theory to practice (pp. 187–206). Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas, J. E., & Burgess, A. E. (1986). Criminal profiling: A viable investigative tool against violent crime . FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin , 55 , 9–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas, J. E., Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Hartman, C. R. (1986). Criminal profiling from crime scene analysis . Behavioral Sciences & the Law , 4 ( 4 ), 401–422. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370040405 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farber, M. (1942). Logical systems and the principles of logic . Philosophy of Science , 9 ( 1 ), 40–54. doi: 10.1086/286747 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2002). Uniform crime report . www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius_02/html/web/index.html

- Fox, B., Farrington, D. P., Kapardis, A., & Hambly, O. C. (2020). Evidence-based offender profiling . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox, B., & Farrington, D. P. (2018). What have we learned from offender profiling? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 years of research . Psychological Bulletin , 144 ( 12 ), 1247–1274. doi: 10.1037/bul0000170 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freckelton, I. (2008). Profiling evidence in the courts. In Canter D. & Žukauskienė R. (Eds.), Psychology and law: Bridging the gap (pp. 79–102). Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gekoski, A., & Gray, J. M. (2011). It may be true, but how’s it helping?’: UK police detectives’ views of the operational usefulness of offender profiling . International Journal of Police Science & Management , 13 ( 2 ), 103–116. doi: 10.1350/ijps.2011.13.2.236 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldsworthy, T. (2001). Criminal profiling. Is it investigatively relevant? [Master of criminology dissertation]. Bond University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gormley, J., & Petherick, W. (2015). Risk assessment. In Petherick W. (Ed.), Applied crime analysis: A social science approach to understanding crime, criminals, and victims (pp. 172–189). Elsevier. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hazelwood, R. R., & Douglas, J. E. (1980). The lust murderer . FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin , 49 ( 4 ), 1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Holmes, R., & Holmes, S. (2002). Profiling violent crimes: An investigative tool (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kocsis, R. N. (2001). Serial arsonist crime profiling: An Australian empirical study . Firenews. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kocsis, R. N., Irwin, H. J., Hayes, A. F., & Nunn, R. (2000). Expertise in psychological profiling: A comparative assessment . Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 15 ( 3 ), 311–331. doi: 10.1177/088626000015003006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshall, B. C., & Alison, L. (2011). Stereotyping, congruence and presentation order: Interpretative biases in utilizing offender profiles. In Alison L., Rainbow L., & Knabe S. (Eds.), Professionalising offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- McGrath, M. (2001). Criminal profiling: Is there a role for the forensic psychiatrist? Journal of the American Academy of Forensic Psychiatry and Law , 28 ( 3 ), 315–324. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morton, R. J., Tillman, J. M., & Gaines, S. J. (2014). Serial murder: Pathways for investigations . U.S. Department of Justice. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mouzos, J. (2005). Homicide in Australia: 2003-2004 national homicide monitoring program (NHMP) annual report . Australian Institute of Criminology. [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro, J., & Schafer, J. R. (2003). Universal principles of criminal behavior: A tool for analyzing criminal intent. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin , 72 (1), 22–24. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/fbileb72&i=23 [ Google Scholar ]

- Neblett, W. (1985). Sherlock’s logic: Learn to reason like a master detective . Barnes and Noble Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Niiniluoto, I. (1999). Defending abduction . Philosophy of Science , 66 , S436–S451. http://www.jstor.com/stable/188790 [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A. (2014a). Criminal profiling methods. In Petherick W. A. (Ed.), Profiling and serial crime: Theoretical and practical issues in behavioural profiling (3rd ed.). Anderson Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A. (2014b). Induction and deduction in criminal profiling. In Petherick W. A. (Ed.), Profiling and serial crime: Theoretical and practical issues in behavioural profiling (3rd ed.). Anderson Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A., & Brooks, N. (2014). Where to from here? In Petherick W. A. (Ed.), Profiling and serial crime: Theoretical and practical issues in behavioural profiling (3rd ed., pp. 241–259). Anderson Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A., & Ferguson, C. E. (2010). Ethics for the forensic criminologist. In Petherick W. A., Turvey B. E., & Ferguson C. E. (Eds.), Forensic Criminology . Elsevier Science. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A., & Turvey, B. E. (2008). Behavioral evidence analysis: An ideo deductive method of criminal profiling. In Turvey B. E. (Ed.), Criminal profiling: An introduction to behavioral evidence analysis (3rd ed). Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pierce, C. S. (1898). Reasoning and the logic of things: The Cambridge conferences lectures of 1898 . In K. L. Ketner (Ed.). Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinizzotto, A. J., & Finkel, N. J. (1990). Criminal personality profiling: An outcome and process study . Law and Human Behavior , 14 ( 3 ), 215–233. doi: 10.1007/BF01352750 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rainbow, L., & Gregory, A. (2011). What behavioural investigative advisers actually do. In L. Alison & L. Rainbow (Eds.), Professionalizing offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice (pp. 35–50). Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rainbow, L., Gregory, A., & Alison, L. (2014). Behavioural investigative advice. In Bruinsma G. J. N. & Weisburd D. L. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 125–134). Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Douglas, J. E. (1992). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives . Free Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Snook, B., Eastwood, J., Gendreau, P., & Bennell, C. (2010). The importance of knowledge cumulation and the search for hidden agendas: A reply to Kocsis, Middledorp, and Karpin (2008). Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice , 10 (3), 214–223. doi: 10.1080/15228930903550541 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stock, G. W. J. (2004). Deductive logic . Project Gutenberg Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thornton, J. (1997). The general assumptions and rationale of forensic identification. In Faigman D. L., Kaye D. H., Saks M. J., & Sanders J. (Eds.), Modern scientific evidence: The law and expert testimony . West Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Torres, A. N., Boccaccini, M. T., & Miller, H. A. (2006). Perceptions of the validity and utility of criminal profiling among forensic psychologists and psychiatrists . Professional Psychology: Research and Practice , 37 ( 1 ), 51–58. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.1.51 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toulmin, S. (1958). The uses of argument . Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Turvey, B. E. (2012). Ethics and the criminal profiler. In Turvey B. E. (Ed.), Criminal Profiling: An introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis (4th ed., pp. 601–626). Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- West, A. (2000). Clinical assessment of homicide offenders: The significance of crime scene in offense and offender analysis . Homicide Studies , 4 ( 3 ), 219–233. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson, P., Lincoln, R., & Kocsis, R. N. (1997). Validity, utility and ethics for serial violent and sex offenders . Psychiatry, Psychology and Law , 4 ( 1 ), 1–12. doi: 10.1080/13218719709524891 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- © 2007

Criminal Profiling

International Theory, Research, and Practice

- Richard N. Kocsis (Forensic Psychologist)

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Combines vast empirical research with the author's personal experiences

Draws together for the time the characteristics of the CAP approach to profiling violent crimes

Describes for the experienced and lay person how to use the various CAP models to profile a particular crime without necessarily needing to comprehend how each model was originally built

91k Accesses

123 Citations

5 Altmetric

- Table of contents

About this book

Bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

Buying options

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check for access.

Table of contents (20 chapters)

Front matter, profiling crimes of violence, homicidal syndromes.

- George B. Palermo

Offender Profiles and Crime Scene Patterns in Belgian Sexual Murders

- Fanny Gerard, Christian Mormont, Richard N. Kocsis

Profiling Sexual Fantasy

- Dion Gee, Aleksandra Belofastov

Murder by Manual and Ligature Strangulation

- Helinä Häkkänen

Criminal Propensity and Criminal Opportunity

- Eric Beauregard, Patrick Lussier, Jean Proulx

New Techniques and Applications

Case linkage.

- Jessica Woodhams, Ray Bull, Clive R. Hollin

Predicting Offender Profiles From Offense and Victim Characteristics

- David P. Farrington, Sandra Lambert

Criminal Profiling in a Terrorism Context

Geographic profiling of terrorist attacks.

- Craig Bennell, Shevaun Corey

Legal and Policy Considerations for Criminal Profiling

Criminal profiling as expert evidence.

- Caroline B. Meyer

- Anne Marie R. Paclebar, Bryan Myers, Jocelyn Brineman

The Phenomenon of Serial Murder and the Judicial Admission of Criminal Profiling in Italy

- Angelo Zappalá, Dario Bosco

Criminal Profiling and Public Policy

- Jeffrey B. Bumgarner

The Observations of the French Judiciary

- Laurent Montet

The Image of Profiling

- James S. Herndon

Critiques and Conceptual Dimensions to Criminal Profiling

- Violent Crime

- identification

Book Title : Criminal Profiling

Book Subtitle : International Theory, Research, and Practice

Editors : Richard N. Kocsis

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-146-2

Publisher : Humana Totowa, NJ

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : Humana Press 2007

Hardcover ISBN : 978-1-58829-684-9 Published: 06 July 2007

Softcover ISBN : 978-1-61737-717-4 Published: 05 November 2010

eBook ISBN : 978-1-60327-146-2 Published: 30 June 2007

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXII, 418

Number of Illustrations : 10 b/w illustrations

Topics : Forensic Medicine

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Criminal & Behavioral Profiling

- Curt R. Bartol

- Anne M. Bartol

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

(Due to changes in the curriculum we have not adopted this book or any similar text.) The book gives a good basic overview of the field of criminal and behavioural profiling. The text is very accessible and should be ok to read even for non-native English readers. I would not hesitate to use this book at our university of applied sciences or at a university in the Netherland. The development of the field is described along historical lines and works towards the current way that theory, research and practice are still evolving. It’s very much a relatively young discipline and not without it’s controversies. These and different schools of thought within the field are well presented in the book. The book is a very nice and concise introduction into the field of criminal and behavioural profiling.