- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2021

Financial technology and the future of banking

- Daniel Broby ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5482-0766 1

Financial Innovation volume 7 , Article number: 47 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

55 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper presents an analytical framework that describes the business model of banks. It draws on the classical theory of banking and the literature on digital transformation. It provides an explanation for existing trends and, by extending the theory of the banking firm, it illustrates how financial intermediation will be impacted by innovative financial technology applications. It further reviews the options that established banks will have to consider in order to mitigate the threat to their profitability. Deposit taking and lending are considered in the context of the challenge made from shadow banking and the all-digital banks. The paper contributes to an understanding of the future of banking, providing a framework for scholarly empirical investigation. In the discussion, four possible strategies are proposed for market participants, (1) customer retention, (2) customer acquisition, (3) banking as a service and (4) social media payment platforms. It is concluded that, in an increasingly digital world, trust will remain at the core of banking. That said, liquidity transformation will still have an important role to play. The nature of banking and financial services, however, will change dramatically.

Introduction

The bank of the future will have several different manifestations. This paper extends theory to explain the impact of financial technology and the Internet on the nature of banking. It provides an analytical framework for academic investigation, highlighting the trends that are shaping scholarly research into these dynamics. To do this, it re-examines the nature of financial intermediation and transactions. It explains how digital banking will be structurally, as well as physically, different from the banks described in the literature to date. It does this by extending the contribution of Klein ( 1971 ), on the theory of the banking firm. It presents suggested strategies for incumbent, and challenger banks, and how banking as a service and social media payment will reshape the competitive landscape.

The banking industry has been evolving since Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena opened its doors in 1472. Its leveraged business model has proved very scalable over time, but it is now facing new challenges. Firstly, its book to capital ratios, as documented by Berger et al ( 1995 ), have been consistently falling since 1840. This trend continues as competition has increased. In the past decade, the industry has experienced declines in profitability as measured by return on tangible equity. This is partly the result of falling leverage and fee income and partly due to the net interest margin (connected to traditional lending activity). These trends accelerated following the 2008 financial crisis. At the same time, technology has made banks more competitive. Advances in digital technology are changing the very nature of banking. Banks are now distributing services via mobile technology. A prolonged period of very low interest rates is also having an impact. To sustain their profitability, Brei et al. ( 2020 ) note that many banks have increased their emphasis on fee-generating services.

As Fama ( 1980 ) explains, a bank is an intermediary. The Internet is, however, changing the way financial service providers conduct their role. It is fundamentally changing the nature of the banking. This in turn is changing the nature of banking services, and the way those services are delivered. As a consequence, in order to compete in the changing digital landscape, banks have to adapt. The banks of the future, both incumbents and challengers, need to address liquidity transformation, data, trust, competition, and the digitalization of financial services. Against this backdrop, incumbent banks are focused on reinventing themselves. The challenger banks are, however, starting with a blank canvas. The research questions that these dynamics pose need to be investigated within the context of the theory of banking, hence the need to revise the existing analytical framework.

Banks perform payment and transfer functions for an economy. The Internet can now facilitate and even perform these functions. It is changing the way that transactions are recorded on ledgers and is facilitating both public and private digital currencies. In the past, banks operated in a world of information asymmetry between themselves and their borrowers (clients), but this is changing. This differential gave one bank an advantage over another due to its knowledge about its clients. The digital transformation that financial technology brings reduces this advantage, as this information can be digitally analyzed.

Even the nature of deposits is being transformed. Banks in the future will have to accept deposits and process transactions made in digital form, either Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) or cryptocurrencies. This presents a number of issues: (1) it changes the way financial services will be delivered, (2) it requires a discussion on resilience, security and competition in payments, (3) it provides a building block for better cross border money transfers and (4) it raises the question of private and public issuance of money. Braggion et al ( 2018 ) consider whether these represent a threat to financial stability.

The academic study of banking began with Edgeworth ( 1888 ). He postulated that it is based on probability. In this respect, the nature of the business model depends on the probability that a bank will not be called upon to meet all its liabilities at the same time. This allows banks to lend more than they have in deposits. Because of the resultant mismatch between long term assets and short-term liabilities, a bank’s capital structure is very sensitive to liquidity trade-offs. This is explained by Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ). They explain that this makes a bank a’relationship lender’. In effect, they suggest a bank is an intermediary that has borrowed from other investors.

Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ) argue a lender can negotiate repayment obligations and that a bank benefits from its knowledge of the customer. As shall be shown, the new generation of digital challenger banks do not have the same tradeoffs or knowledge of the customer. They operate more like a broker providing a platform for banking services. This suggests that there will be more than one type of bank in the future and several different payment protocols. It also suggests that banks will have to data mine customer information to improve their understanding of a client’s financial needs.

The key focus of Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ), however, was to position a traditional bank is an intermediary. Gurley and Shaw ( 1956 ) describe how the customer relationship means a bank can borrow funds by way of deposits (liabilities) and subsequently use them to lend or invest (assets). In facilitating this mediation, they provide a service whereby they store money and provide a mechanism to transmit money. With improvements in financial technology, however, money can be stored digitally, lenders and investors can source funds directly over the internet, and money transfer can be done digitally.

A review of financial technology and banking literature is provided by Thakor ( 2020 ). He highlights that financial service companies are now being provided by non-deposit taking contenders. This paper addresses one of the four research questions raised by his review, namely how theories of financial intermediation can be modified to accommodate banks, shadow banks, and non-intermediated solutions.

To be a bank, an entity must be authorized to accept retail deposits. A challenger bank is, therefore, still a bank in the traditional sense. It does not, however, have the costs of a branch network. A peer-to-peer lender, meanwhile, does not have a deposit base and therefore acts more like a broker. This leads to the issue that this paper addresses, namely how the banks of the future will conduct their intermediation.

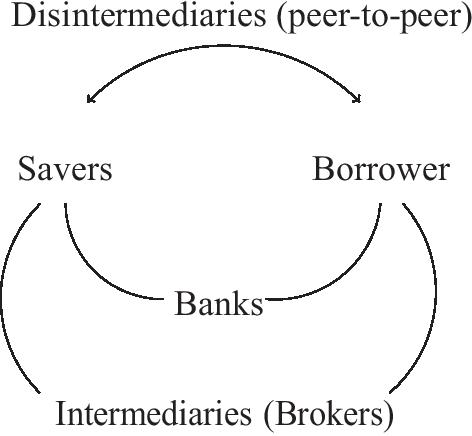

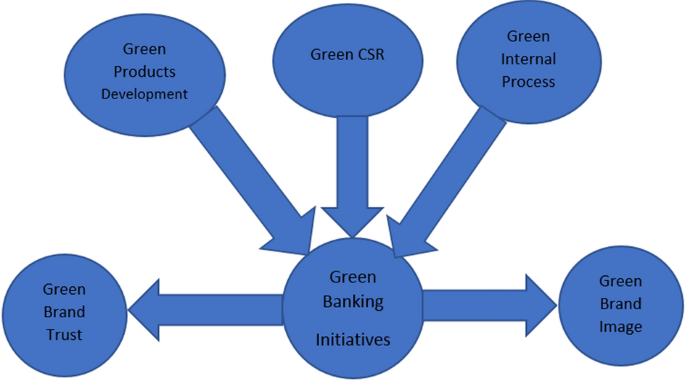

In order to understand what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the nature of the aforementioned intermediation, and the way it is changing. In this respect, there are two key types of intermediation. These are (1) quantitative asset transformation and, (2) brokerage. The latter is a common model adopted by challenger banks. Figure 1 depicts how these two types of financial intermediation match savers with borrowers. To avoid nuanced distinction between these two types of intermediation, it is common to classify banks by the services they perform. These can be grouped as either private, investment, or commercial banking. The service sub-groupings include payments, settlements, fund management, trading, treasury management, brokerage, and other agency services.

How banks act as intermediaries between lenders and borrowers. This function call also be conducted by intermediaries as brokers, for example by shadow banks. Disintermediation occurs over the internet where peer-to-peer lenders match savers to lenders

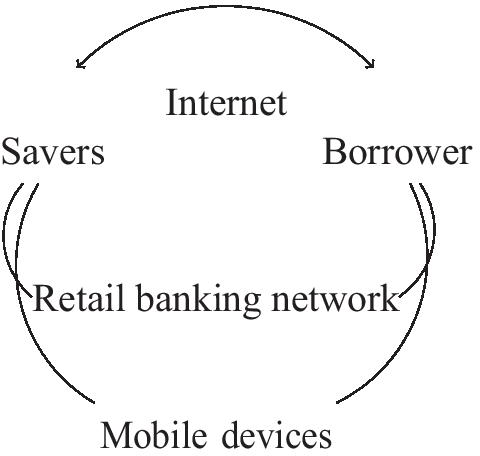

Financial technology has the ability to disintermediate the banking sector. The competitive pressures this results in will shape the banks of the future. The channels that will facilitate this are shown in Fig. 2 , namely the Internet and/or mobile devices. Challengers can participate in this by, (1) directly matching borrows with savers over the Internet and, (2) distributing white labels products. The later enables banking as a service and avoids the aforementioned liquidity mismatch.

The strategic options banks have to match lenders with borrowers. The traditional and challenger banks are in the same space, competing for business. The distributed banks use the traditional and challenger banks to white label banking services. These banks compete with payment platforms on social media. The Internet heralds an era of banking as a service

There are also physical changes that are being made in the delivery of services. Bricks and mortar branches are in decline. Mobile banking, or m-banking as Liu et al ( 2020 ) describe it, is an increasingly important distribution channel. Robotics are increasingly being used to automate customer interaction. As explained by Vishnu et al ( 2017 ), these improve efficiency and the quality of execution. They allow for increased oversight and can be built on legacy systems as well as from a blank canvas. Application programming interfaces (APIs) are bringing the same type of functionality to m-banking. They can be used to authorize third party use of banking data. How banks evolve over time is important because, according to the OECD, the activity in the financial sector represents between 20 and 30 percent of developed countries Gross Domestic Product.

In summary, financial technology has evolved to a level where online banks and banking as a service are challenging incumbents and the nature of banking mediation. Banking is rapidly transforming because of changes in such technology. At the same time, the solving of the double spending problem, whereby digital money can be cryptographically protected, has led to the possibility that paper money will become redundant at some point in the future. A theoretical framework is required to understand this evolving landscape. This is discussed next.

The theory of the banking firm: a revision

In financial theory, as eloquently explained by Fama ( 1980 ), banking provides an accounting system for transactions and a portfolio system for the storage of assets. That will not change for the banks of the future. Fama ( 1980 ) explains that their activities, in an unregulated state, fulfil the Modigliani–Miller ( 1959 ) theorem of the irrelevance of the financing decision. In practice, traditional banks compete for deposits through the interest rate they offer. This makes the transactional element dependent on the resulting debits and credits that they process, essentially making banks into bookkeeping entities fulfilling the intermediation function. Since this is done in response to competitive forces, the general equilibrium is a passive one. As such, the banking business model is vulnerable to disruption, particularly by innovation in financial technology.

A bank is an idiosyncratic corporate entity due to its ability to generate credit by leveraging its balance sheet. That balance sheet has assets on one side and liabilities on the other, like any corporate entity. The assets consist of cash, lending, financial and fixed assets. On the other side of the balance sheet are its liabilities, deposits, and debt. In this respect, a bank’s equity and its liabilities are its source of funds, and its assets are its use of funds. This is explained by Klein ( 1971 ), who notes that a bank’s equity W , borrowed funds and its deposits B is equal to its total funds F . This is the same for incumbents and challengers. This can be depicted algebraically if we let incumbents be represented by Φ and challengers represented by Γ:

Klein ( 1971 ) further explains that a bank’s equity is therefore made up of its share capital and unimpaired reserves. The latter are held by a bank to protect the bank’s deposit clients. This part is also mandated by regulation, so as to protect customers and indeed the entire banking system from systemic failure. These protective measures include other prudential requirements to hold cash reserves or other liquid assets. As shall be shown, banking services can be performed over the Internet without these protections. Banking as a service, as this phenomenon known, is expected to increase in the future. This will change the nature of the protection available to clients. It will change the way banks transform assets, explained next.

A bank’s deposits are said to be a function of the proportion of total funds obtained through the issuance of the ith deposit type and its total funds F , represented by α i . Where deposits, represented by Bs , are made in the form of Bs (i = 1 *s n) , they generate a rate of interest. It follows that Si Bs = B . As such,

Therefor it can be said that,

The importance of Eq. 3 is that the balance sheet can be leveraged by the issuance of loans. It should be noted, however, that not all loans are returned to the bank in whole or part. Non-performing loans reduce the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet and act as a constraint on capital, and therefore new lending. Clearly, this is not the case with banking as a service. In that model, loans are brokered. That said, with the traditional model, an advantage of financial technology is that it facilitates the data mining of clients’ accounts. Lending can therefore be more targeted to borrowers that are more likely to repay, thereby reducing non-performing loans. Pari passu, the incumbent bank of the future will therefore have a higher risk-adjusted return on capital. In practice, however, banking as a service will bring greater competition from challengers and possible further erosion of margins. Alternatively, some banks will proactively engage in partnerships and acquisitions to maintain their customer base and address the competition.

A bank must have reserves to meet the demand of customers demanding their deposits back. The amount of these reserves is a key function of banking regulation. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision mandates a requirement to hold various tiers of capital, so that banks have sufficient reserves to protect depositors. The Committee also imposes a framework for mitigating excessive liquidity risk and maturity transformation, through a set Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio.

Recent revisions of theory, because of financial technology advances, have altered our understanding of banking intermediation. This will impact the competitive landscape and therefor shape the nature of the bank of the future. In this respect, the threat to incumbent banks comes from peer-to-peer Internet lending platforms. These perform the brokerage function of financial intermediation without the use of the aforementioned banking balance sheet. Unlike regulated deposit takers, such lending platforms do not create assets and do not perform risk and asset transformation. That said, they are reliant on investors who do not always behave in a counter cyclical way.

Financial technology in banking is not new. It has been used to facilitate electronic markets since the 1980’s. Thakor ( 2020 ) refers to three waves of application of financial innovation in banking. The advent of institutional futures markets and the changing nature of financial contracts fundamentally changed the role of banks. In response to this, academics extended the concept of a bank into an entity that either fulfills the aforementioned functions of a broker or a qualitative asset transformer. In this respect, they connect the providers and users of capital without changing the nature of the transformation of the various claims to that capital. This transformation can be in the form risk transfer or the application of leverage. The nature of trading of financial assets, however, is changing. Price discovery can now be done over the Internet and that is moving liquidity from central marketplaces (like the stock exchange) to decentralized ones.

Alongside these trends, in considering what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the unregulated lending market that competes with traditional banks. In this part of the lending market, there has been a rise in shadow banks. The literature on these entities is covered by Adrian and Ashcraft ( 2016 ). Shadow banks have taken substantial market share from the traditional banks. They fulfil the brokerage function of banks, but regulators have only partial oversight of their risk transformation or leverage. The rise of shadow banks has been facilitated by financial technology and the originate to distribute model documented by Bord and Santos ( 2012 ). They use alternative trading systems that function as electronic communication networks. These facilitate dark pools of liquidity whereby buyers and sellers of bonds and securities trade off-exchange. Since the credit crisis of 2008, total broker dealer assets have diverged from banking assets. This illustrates the changed lending environment.

In the disintermediated market, banking as a service providers must rely on their equity and what access to funding they can attract from their online network. Without this they are unable to drive lending growth. To explain this, let I represent the online network. Extending Klein ( 1971 ), further let Ψ represent banking as a service and their total funds by F . This state is depicted as,

Theoretically, it can be shown that,

Shadow banks, and those disintermediators who bypass the banking system, have an advantage in a world where technology is ubiquitous. This becomes more apparent when costs are considered. Buchak et al. ( 2018 ) point out that shadow banks finance their originations almost entirely through securitization and what they term the originate to distribute business model. Diversifying risk in this way is good for individual banks, as banking risks can be transferred away from traditional banking balance sheets to institutional balance sheets. That said, the rise of securitization has introduced systemic risk into the banking sector.

Thus, we can see that the nature of banking capital is changing and at the same time technology is replacing labor. Let A denote the number of transactions per account at a period in time, and C denote the total cost per account per time period of providing the services of the payment mechanism. Klein ( 1971 ) points out that, if capital and labor are assumed to be part of the traditional banking model, it can be observed that,

It can therefore be observed that the total service charge per account at a period in time, represented by S, has a linear and proportional relationship to bank account activity. This is another variable that financial technology can impact. According to Klein ( 1971 ) this can be summed up in the following way,

where d is the basic bank decision variable, the service charge per transaction. Once again, in an automated and digital environment, financial technology greatly reduces d for the challenger banks. Swankie and Broby ( 2019 ) examine the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the evaluation of banking risk and conclude that it improves such variables.

Meanwhile, the traditional banking model can be expressed as a product of the number of accounts, M , and the average size of an account, N . This suggests a banks implicit yield is it rate of interest on deposits adjusted by its operating loss in each time period. This yield is generated by payment and loan services. Let R 1 depict this. These can be expressed as a fraction of total demand deposits. This is depicted by Klein ( 1971 ), if one assumes activity per account is constant, as,

As a result, whether a bank is structured with traditional labor overheads or built digitally, is extremely relevant to its profitability. The capital and labor of tradition banks, depicted as Φ i , is greater than online networks, depicted as I i . As such, the later have an advantage. This can be shown as,

What Klein (1972) failed to highlight is that the banking inherently involves leverage. Diamond and Dybving (1983) show that leverage makes bank susceptible to run on their liquidity. The literature divides these between adverse shock events, as explained by Bernanke et al ( 1996 ) or moral hazard events as explained by Demirgu¨¸c-Kunt and Detragiache ( 2002 ). This leverage builds on the balance sheet mismatch of short-term assets with long term liabilities. As such, capital and liquidity are intrinsically linked to viability and solvency.

The way capital and liquidity are managed is through credit and default management. This is done at a bank level and a supervisory level. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision applies capital and leverage ratios, and central banks manage interest rates and other counter-cyclical measures. The various iterations of the prudential regulation of banks have moved the microeconomic theory of banking from the modeling of risk to the modeling of imperfect information. As mentioned, shadow and disintermediated services do not fall under this form or prudential regulation.

The relationship between leverage and insolvency risk crucially depends on the degree of banks total funds F and their liability structure L . In this respect, the liability structure of traditional banks is also greater than online networks which do not have the same level of available funds, depicted as,

Diamond and Dybvig ( 1983 ) observe that this liability structure is intimately tied to a traditional bank’s assets. In this respect, a bank’s ability to finance its lending at low cost and its ability to achieve repayment are key to its avoidance of insolvency. Online networks and/or brokers do not have to finance their lending, simply source it. Similarly, as brokers they do not face capital loss in the event of a default. This disintermediates the bank through the use of a peer-to-peer environment. These lenders and borrowers are introduced in digital way over the internet. Regulators have taken notice and the digital broker advantage might not last forever. As a result, the future may well see greater cooperation between these competing parties. This also because banks have valuable operational experience compared to new entrants.

It should also be observed that bank lending is either secured or unsecured. Interest on an unsecured loan is typically higher than the interest on a secured loan. In this respect, incumbent banks have an advantage as their closeness to the customer allows them to better understand the security of the assets. Berger et al ( 2005 ) further differentiate lending into transaction lending, relationship lending and credit scoring.

The evolution of the business model in a digital world

As has been demonstrated, the bank of the future in its various manifestations will be a consequence of the evolution of the current banking business model. There has been considerable scholarly investigation into the uniqueness of this business model, but less so on its changing nature. Song and Thakor ( 2010 ) are helpful in this respect and suggest that there are three aspects to this evolution, namely competition, complementary and co-evolution. Although liquidity transformation is evolving, it remains central to a bank’s role.

All the dynamics mentioned are relevant to the economy. There is considerable evidence, as outlined by Levine ( 2001 ), that market liberalization has a causal impact on economic growth. The impact of technology on productivity should prove positive and enhance the functioning of the domestic financial system. Indeed, market liberalization has already reshaped banking by increasing competition. New fee based ancillary financial services have become widespread, as has the proprietorial use of balance sheets. Risk has been securitized and even packaged into trade-able products.

Challenger banks are developing in a complementary way with the incumbents. The latter have an advantage over new entrants because they have information on their customers. The liquidity insurance model, proposed by Diamond and Dybvig ( 1983 ), explains how such banks have informational advantages over exchange markets. That said, financial technology changes these dynamics. It if facilitating the processing of financial data by third parties, explained in greater detail in the section on Open Banking.

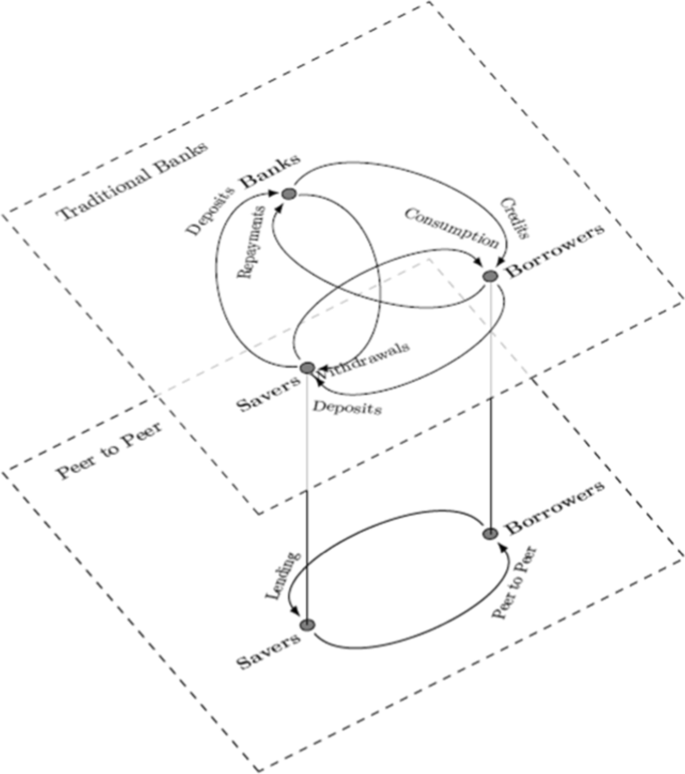

At the same time, financial technology is facilitating banking as a service. This is where financial services are delivered by a broker over the Internet without resort to the balance sheet. This includes roboadvisory asset management, peer to peer lending, and crowd funding. Its growth will be facilitated by Open Banking as it becomes more geographically adopted. Figure 3 illustrates how these business models are disintermediating the traditional banking role and matching burrowers and savers.

The traditional view of banks ecosystem between savers and borrowers, atop the Internet which is matching savers and borrowers directly in a peer-to-peer way. The Klein ( 1971 ) theory of the banking firm does not incorporate the mirrored dynamics, and as such needs to be extended to reflect the digital innovation that impacts both borrowers and severs in a peer-to-peer environment

Meanwhile, the banking sector is co-evolving alongside a shadow banking phenomenon. Lenders and borrowers are interacting, but outside of the banking sector. This is a concern for central banks and banking regulators, as the lending is taking place in an unregulated environment. Shadow banking has grown because of financial technology, market liberalization and excess liquidity in the asset management ecosystem. Pozsar and Singh ( 2011 ) detail the non-bank/bank intersection of shadow banking. They point out that shadow banking results in reverse maturity transformation. Incumbent banks have blurred the distinction between their use of traditional (M2) liabilities and market-based shadow banking (non-M2) liabilities. This impacts the inter-generational transfers that enable a bank to achieve interest rate smoothing.

Securitization has transformed the risk in the banking sector, transferring it to asset management institutions. These include structured investment vehicles, securities lenders, asset backed commercial paper investors, credit focused hedge and money market funds. This in turn has led to greater systemic risk, the result of the nature of the non-traded liabilities of securitized pooling arrangements. This increased risk manifested itself in the 2008 credit crisis.

Commercial pressures are also shaping the banking industry. The drive for cost efficiency has made incumbent banks address their personally costs. Bank branches have been closed as technology has evolved. Branches make it easier to withdraw or transfer deposits and challenger banks are not as easily able to attract new deposits. The banking sector is therefore looking for new point of customer contact, such as supermarkets, post offices and social media platforms. These structural issues are occurring at the same time as the retail high street is also evolving. Banks have had an aggressive roll out of automated telling machines and a reduction in branches and headcount. Online digital transactions have now become the norm in most developed countries.

The financing of banks is also evolving. Traditional banks have tended to fund illiquid assets with short term and unstable liquid liabilities. This is one of the key contributors to the rise to the credit crisis of 2008. The provision of liquidity as a last resort is central to the asset transformation process. In this respect, the banking sector experienced a shock in 2008 in what is termed the credit crisis. The aforementioned liquidity mismatch resulted in the system not being able to absorb all the risks associated with subprime lending. Central banks had to resort to quantitative easing as a result of the failure of overnight funding mechanisms. The image of the entire banking sector was tarnished, and the banks of the future will have to address this.

The future must learn from the mistakes of the past. The structural weakness of the banking business model cannot be solved. That said, the latest Basel rules introduce further risk mitigation, improved leverage ratios and increased levels of capital reserve. Another lesson of the credit crisis was that there should be greater emphasis on risk culture, governance, and oversight. The independence and performance of the board, the experience and the skill set of senior management are now a greater focus of regulators. Internal controls and data analysis are increasingly more robust and efficient, with a greater focus on a banks stable funding ratio.

Meanwhile, the very nature of money is changing. A digital wallet for crypto-currencies fulfills much the same storage and transmission functions of a bank; and crypto-currencies are increasing being used for payment. Meanwhile, in Sweden, stores have the right to refuse cash and the majority of transactions are card based. This move to credit and debit cards, and the solving of the double spending problem, whereby digital money can be crypto-graphically protected, has led to the possibility that paper money could be replaced at some point in the future. Whether this might be by replacement by a CBDC, or decentralized digital offering, is of secondary importance to the requirement of banks to adapt. Whether accommodating crytpo-currencies or CBDC’s, Kou et al. ( 2021 ) recommend that banks keep focused on alternative payment and money transferring technologies.

Central banks also have to adapt. To limit disintermediation, they have to ensure that the economic design of their sponsored digital currencies focus on access for banks, interest payment relative to bank policy rate, banking holding limits and convertibility with bank deposits. All these developments have implications for banks, particularly in respect of funding, the secure storage of deposits and how digital currency interacts with traditional fiat money.

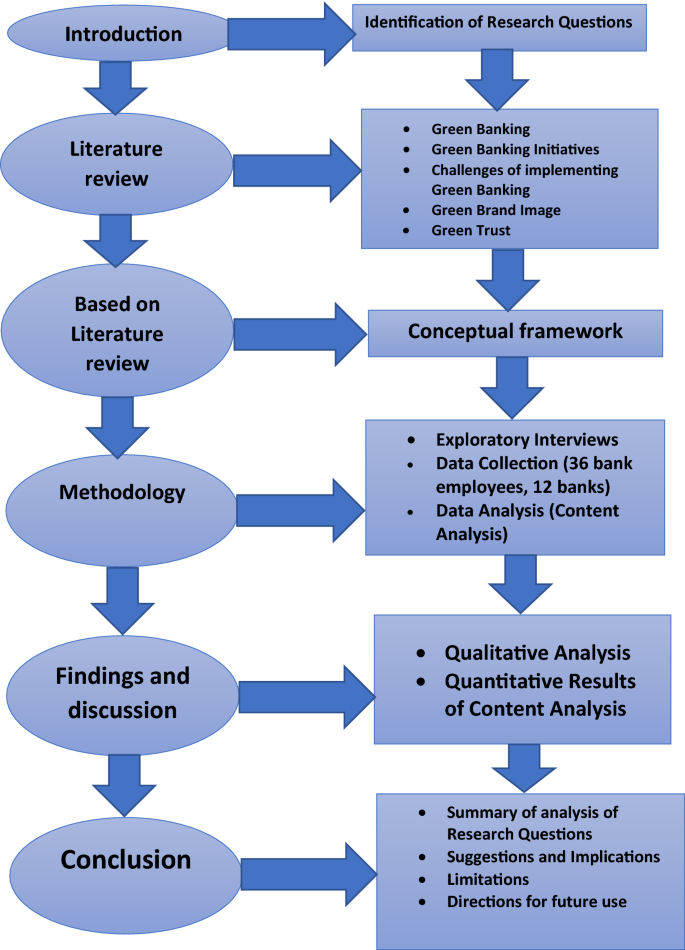

Open banking

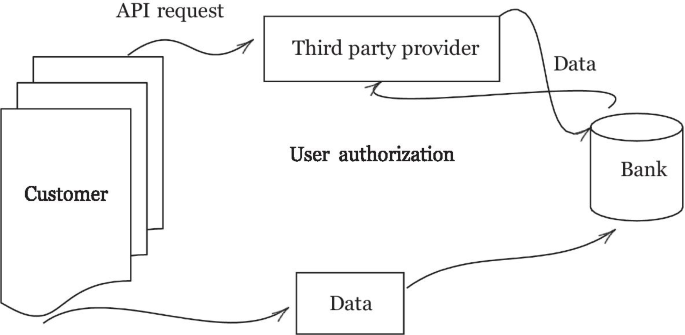

Against the backdrop of all these trends and changes, a new dynamic is shaping the future of the banking sector. This is termed Open Banking, already briefly mentioned. This new way of handling banking data protocols introduces a secure way to give financial service companies consensual access to a bank’s customer financial information. Figure 4 illustrates how this works. Although a fairly simple concept, the implications are important for the banking industry. Essentially, a bank customer gives a regulated API permission to securely access his/her banking website. That is then used by a banking as a service entity to make direct payments and/or download financial data in order to provide a solution. It heralds an era of customer centric banking.

How Open Banking operates. The customer generates data by using his bank account. A third party provider is authorized to access that data through an API request. The bank confirms digitally that the customer has authorized the exchange of data and then fulfills the request

Open Banking was a response to the documented inertia around individual’s willingness to change bank accounts. Following the Retail Banking Review in the UK, this was addressed by lawmakers through the European Union’s Payment Services Directive II. The legislation was designed to make it easier to change banks by allowing customers to delegate authority to transfer their financial data to other parties. As a result of this, a whole host of data centric applications were conceived. Open banking adds further momentum to reshaping the future of banking.

Open Banking has a number of quite revolutionary implications. It was started so customers could change banks easily, but it resulted in some secondary considerations which are going to change the future of banking itself. It gives a clear view of bank financing. It allows aggregation of finances in one place. It also allows can give access to attractive offerings by allowing price comparisons. Open Banking API’s build a secure online financial marketplace based on data. They also allow access to a larger market in a faster way but the third-party providers for the new entrants. Open Banking allows developers to build single solutions on an API addressing very specific problems, like for example, a cash flow based credit rating.

Romānova et al. ( 2018 ) undertook a questionnaire on the Payment Services Directive II. The results suggest that Open Banking will promote competitiveness, innovation, and new product development. The initiative is associated with low costs and customer satisfaction, but that some concerns about security, privacy and risk are present. These can be mitigated, to some extent, by secure protocols and layered permission access.

Discussion: strategic options

Faced with these disruptive trends, there are four strategic options for market participants to con- sider. There are (1) a defensive customer retention strategy for incumbents, (2) an aggressive customer acquisition strategy for challenger banks (3) a banking as a service strategy for new entrants, and (4) a payments strategy for social media platforms.

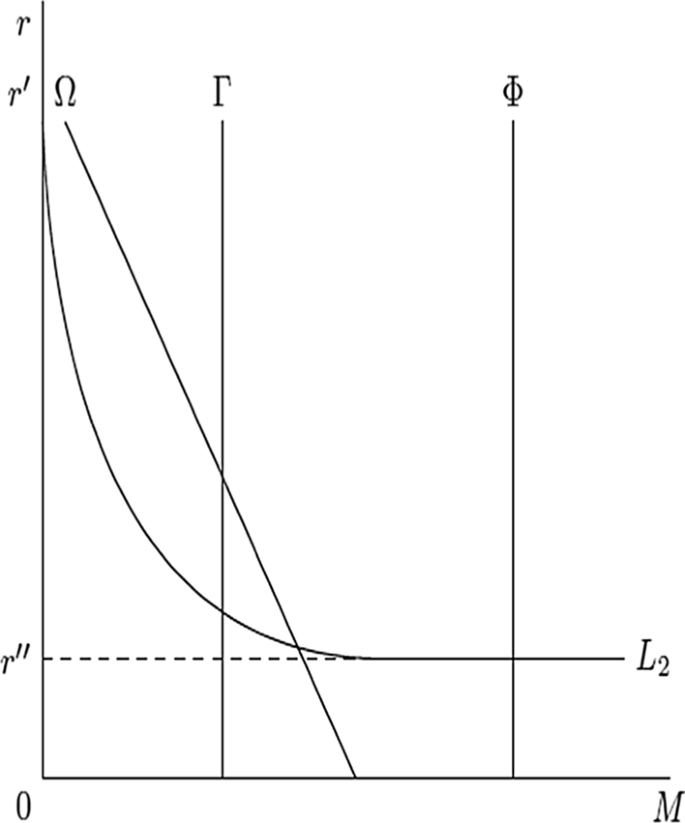

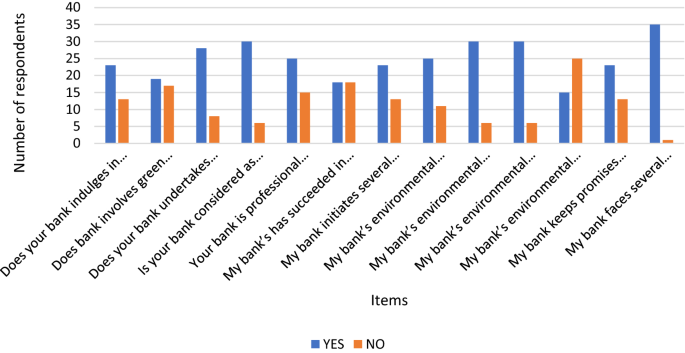

Each of these strategies has to be conducted in a competitive marketplace for money demand by potential customers. Figure 5 illustrates where the first three strategies lie on the tradeoff between money demand and interest rates. The payment strategy can’t be modeled based on the supply of money. In the figure, the market settles at a rate L 2 . The incumbent banks have the capacity to meet the largest supply of these loans. The challenger banks have a constrained function but due to a lower cost base can gain excess rent through higher rates of interest. The peer-to-peer bank as a service brokers must settle for the market rate and a constrained supply offering.

The money demand M by lenders on the y axis. Interest rates on the y axis are labeled as r I and r II . The challenger banks are represented by the line labeled Γ. They have a price and technology advantage and so can lend at higher interest rates. The brokers are represented by the line labeled Ω. They are price takers, accepting the interest rate determined by the market. The same is true for the incumbents, represented by the line labeled Φ but they have a greater market share due to their customer relationships. Note that payments strategy for social media platforms is not shown on this figure as it is not affected by interest rates

Figure 5 illustrates that having a niche strategy is not counterproductive. Liu et al ( 2020 ) found that banks performing niche activities exhibit higher profitability and have lower risk. The syndication market now means that a bank making a loan does not have to be the entity that services it. This means banks in the future can better shape their risk profile and manage their lending books accordingly.

An interesting question for central banks is what the future Deposit Supply function will look like. If all three forms: open banking, traditional banking and challenger banks develop together, will the bank of the future have the same Deposit Supply function? The Klein ( 1971 ) general formulation assumes that deposits are increasing functions of implicit and explicit yields. As such, the very nature of central bank directed monetary policy may have to be revisited, as alluded to in the earlier discussion on digital money.

The client retention strategy (incumbents)

The competitive pressures suggest that incumbent banks need to focus on customer retention. Reichheld and Kenny ( 1990 ) found that the best way to do this was to focus on the retention of branch deposit customers. Obviously, another way is to provide a unique digital experience that matches the challengers.

Incumbent banks have a competitive advantage based on the information they have about their customers. Allen ( 1990 ) argues that where risk aversion is observable, information markets are viable. In other words, both bank and customer benefit from this. The strategic issue for them, therefore, becomes the retention of these customers when faced with greater competition.

Open Banking changes the dynamics of the banking information advantage. Borgogno and Colangelo ( 2020 ) suggest that the access to account (XS2A) rule that it introduced will increase competition and reduce information asymmetry. XS2A requires banks to grant access to bank account data to authorized third payment service providers.

The incumbent banks have a high-cost base and legacy IT systems. This makes it harder for them to migrate to a digital world. There are, however, also benefits from financial technology for the incumbents. These include reduced cost and greater efficiency. Financial technology can also now support platforms that allow incumbent banks to sell NPL’s. These platforms do not require the ownership of assets, they act as consolidators. The use of technology to monitor the transactions make the processing cost efficient. The unique selling point of such platforms is their centralized point of contact which results in a reduction in information asymmetry.

Incumbent banks must adapt a number of areas they got to adapt in terms of their liquidity transformation. They have to adapt the way they handle data. They must get customers to trust them in a digital world and the way that they trust them in a bricks and mortar world. It is no coincidence. When you go into a bank branch that is a great big solid building great big facade and so forth that is done deliberately so that you trust that bank with your deposit.

The risk of having rising non-performing loans needs to be managed, so customer retention should be selective. One of the puzzles in banking is why customers are regularly denied credit, rather than simply being charged a higher price for it. This credit rationing is often alleviated by collateral, but finance theory suggests value is based on the discounted sum of future cash flows. As such, it is conceivable that the bank of the future will use financial technology to provide innovative credit allocation solutions. That said, the dual risks of moral hazard and information asymmetries from the adoption of such solutions must be addressed.

Customer retention is especially important as bank competition is intensifying, as is the digitalization of financial services. Customer retention requires innovation, and that innovation has been moving at a very fast rate. Until now, banks have traditionally been hesitant about technology. More recently, mergers and acquisitions have increased quite substantially, initiated by a need to address actual or perceived weaknesses in financial technology.

The client acquisition strategy (challengers)

As intermediaries, the challenger banks are the same as incumbent banks, but designed from the outset to be digital. This gives them a cost and efficiency advantage. Anagnostopoulos ( 2018 ) suggests that the difference between challenger and traditional banks is that the former address its customers problems more directly. The challenge for such banks is customer acquisition.

Open Banking is a major advantage to challenger banks as it facilitates the changing of accounts. There is widespread dissatisfaction with many incumbent banks. Open Banking makes it easier to change accounts and also easier to get a transaction history on the client.

Customer acquisition can be improved by building trust in a brand. Historically, a bank was physically built in a very robust manner, hence the heavy architecture and grand banking halls. This was done deliberately to engender a sense of confidence in the deposit taking institution. Pure internet banks are not able to do this. As such, they must employ different strategies to convey stability. To do this, some communicate their sustainability credentials, whilst others use generational values-based advertising. Customer acquisition in a banking context is traditionally done by offering more attractive rates of interest. This is illustrated in Fig. 5 by the intersect of traditional banks with the market rate of interest, depicted where the line Γ crosses L 2 . As a result of the relationship with banking yield, teaser rates and introductory rates are common. A customer acquisition strategy has risks, as consumers with good credit can game different challenger banks by frequently changing accounts.

Most customer acquisition, however, is done based on superior service offering. The functionality of challenger banking accounts is often superior to incumbents, largely because the latter are built on legacy databases that have inter-operability issues. Having an open platform of services is a popular customer acquisition technique. The unrestricted provision of third-party products is viewed more favorably than a restricted range of products.

The banking as a service strategy (new entrants)

Banking from a customer’s perspective is the provision of a service. Customers don’t care about the maturity transformation of banking balance sheets. Banking as a service can be performed without recourse to these balance sheets. Banking products are brokered, mostly by new entrants, to individuals as services that can be subscribed to or paid on a fee basis.

There are a number banking as a service solutions including pre-paid and credit cards, lending and leasing. The banking as a service brokers are effectively those that are aggregating services from others using open banking to enable banking as a service.

The rise of banking as a service needs to be understood as these compete directly with traditional banks. As explained, some of these do this through peer-to-peer lending over the internet, others by matching borrows and sellers, conducting mediation as a loan broker. Such entities do not transform assets and do not have banking licenses. They do not have a branch network and often don not have access to deposits. This means that they have no insurance protection and can be subject to interest rate controls.

The new genre of financial technology, banking as a service provider, conduct financial services transformation without access to central bank liquidity. In a distributed digital asset world, the assets are stored on a distributed ledger rather than a traditional banking ledger. Financial technology has automated credit evaluation, savings, investments, insurance, trading, banking payments and risk management. These banking as a service offering are only as secure as the technology on which they are built.

The social media payment strategy (disintermediators and disruptors)

An intermediation bank is a conceptual idea, one created solely on a social networking site. Social media has developed a market for online goods and services. Williams ( 2018 ) estimates that there are 2.46 billion social media users. These all make and receive payments of some kind. They demand security and functionality. Importantly, they have often more clients than most banks. As such, a strategy to monetize the payments infrastructure makes sense.

All social media platforms are rich repositories of data. Such platforms are used to buy and sell things and that requires payments. Some platforms are considering evolving their own digital payment, cutting out the banks as middlemen. These include Facebook’s Diem (formerly Libra), a digital currency, and similar developments at some of the biggest technology companies. The risk with social media payment platform is that there is systemic counter-party protection. Regulators need to address this. One way to do this would be to extend payment service insurance to such platforms.

Social media as a platform moves the payment relationship from a transaction to a customer experience. The ability to use consumer desires in combination with financial data has the potential to deliver a number of new revenue opportunities. These will compete directly with the banks of the future. This will have implications for (1) the money supply, (2) the market share of traditional banks and, (3) the services that payment providers offer.

Further research

Several recommendations for research derive from both the impact of disintermediation and the four proposed strategies that will shape banking in the future. The recommendations and suggestions are based on the mentioned papers and the conclusions drawn from them.

As discussed, the nature of intermediation is changing, and this has implications for the pricing of risk. The role of interest rates in banking will have to be further reviewed. In a decentralized world based on crypto currencies the central banks do not have the same control over the money supply, This suggest the quantity theory of money and the liquidity preference theory need to be revisited. As explained, the Internet reduces much of the friction costs of intermediation. Researchers should ask how this will impact maturity transformation. It is also fair to ask whether at some point in the future there will just be one big bank. This question has already been addressed in the literature but the Internet facilities the possibility. Diamond ( 1984 ) and Ramakrishnan and Thakor ( 1984 ) suggested the answer was due to diversification and its impact on reducing monitoring costs.

Attention should be given by academics to the changing nature of banking risk. How should regulators, for example, address the moral hazard posed by challenger banks with weak balance sheets? What about deposit insurance? Should it be priced to include unregulated entities? Also, what criteria do borrowers use to choose non-banking intermediaries? The changing risk environment also poses two interesting practical questions. What will an online bank run look like, and how can it be averted? How can you establish trust in digital services?

There are also research questions related to the nature of competition. What, for example, will be the nature of cross border competition in a decentralized world? Is the credit rationing that generates competition a static or dynamic phenomena online? What is the value of combining consumer utility with banking services?

Financial intermediaries, like banks, thrive in a world of deficits and surpluses supported by information asymmetries and disconnectedness. The connectivity of the internet changes this dynamic. In this respect, the view of Schumpeter ( 1911 ) on the role of financial intermediaries needs revisiting. Lenders and borrows can be connected peer to peer via the internet.

All the dynamics mentioned change the nature of moral hazard. This needs further investigation. There has been much scholarly research on the intrinsic riskiness of the mismatch between banking assets and liabilities. This mismatch not only results in potential insolvency for a single bank but potentially for the whole system. There has, for example, been much debate on the whether a bank can be too big to fail. As a result of the riskiness of the banking model, the banks of the future will be just a liable to fail as the banks of the past.

This paper presented a revision of the theory of banking in a digital world. In this respect, it built on the work of Klein ( 1971 ). It provided an overview of the changing nature of banking intermediation, a result of the Internet and new digital business models. It presented the traditional academic view of banking and how it is evolving. It showed how this is adapted to explain digital driven disintermediation.

It was shown that the banking industry is facing several documented challenges. Risk is being taken of balance sheet, securitized, and brokered. Financial technology is digitalizing service delivery. At the same time, the very nature of intermediation is being changed due to digital currency. It is argued that the bank of the future not only has to face these competitive issues, but that technology will enhance the delivery of banking services and reduce the cost of their delivery.

The paper further presented the importance of the Open Banking revolution and how that facilitates banking as a service. Open Banking is increasing client churn and driving banking as a service. That in turn is changing the way products are delivered.

Four strategies were proposed to navigate the evolving competitive landscape. These are for incumbents to address customer retention; for challengers to peruse a low-cost digital experience; for niche players to provide banking as a service; and for social media platforms to develop payment platforms. In all these scenarios, the banks of the future will have to have digital strategies for both payments and service delivery.

It was shown that both incumbents and challengers are dependent on capital availability and borrowers credit concerns. Nothing has changed in that respect. The risks remain credit and default risk. What is clear, however, is the bank has become intrinsically linked with technology. The Internet is changing the nature of mediation. It is allowing peer to peer matching of borrowers and savers. It is facilitating new payment protocols and digital currencies. Banks need to evolve and adapt to accommodate these. Most of these questions are empirical in nature. The aim of this paper, however, was to demonstrate that an understanding of the banking model is a prerequisite to understanding how to address these and how to develop hypotheses connected with them.

In conclusion, financial technology is changing the future of banking and the way banks intermediate. It is facilitating digital money and the online transmission of financial assets. It is making banks more customer enteric and more competitive. Scholarly investigation into banking has to adapt. That said, whatever the future, trust will remain at the core of banking. Similarly, deposits and lending will continue to attract regulatory oversight.

Availability of data and materials

Diagrams are my own and the code to reproduce them is available in the supplied Latex files.

Adrian T, Ashcraft AB (2016) Shadow banking: a review of the literature. In: Banking crises. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 282–315

Allen F (1990) The market for information and the origin of financial intermediation. J Financ Intermed 1(1):3–30

Article Google Scholar

Anagnostopoulos I (2018) Fintech and regtech: impact on regulators and banks. J Econ Bus 100:7–25

Berger AN, Herring RJ, Szegö GP (1995) The role of capital in financial institutions. J Bank Finance 19(3–4):393–430

Berger AN, Miller NH, Petersen MA, Rajan RG, Stein JC (2005) Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. J Financ Econ 76(2):237–269

Bernanke B, Gertler M, Gilchrist S (1996) The financial accelerator and the flight to quality. The review of economics and statistics, pp1–15

Bord V, Santos JC (2012) The rise of the originate-to-distribute model and the role of banks in financial intermediation. Federal Reserve Bank N Y Econ Policy Rev 18(2):21–34

Google Scholar

Borgogno O, Colangelo G (2020) Data, innovation and competition in finance: the case of the access to account rule. Eur Bus Law Rev 31(4)

Braggion F, Manconi A, Zhu H (2018) Is Fintech a threat to financial stability? Evidence from peer-to-Peer lending in China, November 10

Brei M, Borio C, Gambacorta L (2020) Bank intermediation activity in a low-interest-rate environment. Econ Notes 49(2):12164

Buchak G, Matvos G, Piskorski T, Seru A (2018) Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. J Financ Econ 130(3):453–483

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Detragiache E (2002) Does deposit insurance increase banking system stability? An empirical investigation. J Monet Econ 49(7):1373–1406

Diamond DW (1984) Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. Rev Econ Stud 51(3):393–414

Diamond DW, Dybvig PH (1983) Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. J Polit Econ 91(3):401–419

Diamond DW, Rajan RG (2000) A theory of bank capital. J Finance 55(6):2431–2465

Edgeworth FY (1888) The mathematical theory of banking. J Roy Stat Soc 51(1):113–127

Fama EF (1980) Banking in the theory of finance. J Monet Econ 6(1):39–57

Gurley JG, Shaw ES (1956) Financial intermediaries and the saving-investment process. J Finance 11(2):257–276

Klein MA (1971) A theory of the banking firm. J Money Credit Bank 3(2):205–218

Kou G, Akdeniz ÖO, Dinçer H, Yüksel S (2021) Fintech investments in European banks: a hybrid IT2 fuzzy multidimensional decision-making approach. Financ Innov 7(1):1–28

Levine R (2001) International financial liberalization and economic growth. Rev Interna Tional Econ 9(4):688–702

Liu FH, Norden L, Spargoli F (2020) Does uniqueness in banking matter? J Bank Finance 120:105941

Pozsar Z, Singh M (2011) The nonbank-bank nexus and the shadow banking system. IMF working papers, pp 1–18

Ramakrishnan RT, Thakor AV (1984) Information reliability and a theory of financial intermediation. Rev Econ Stud 51(3):415–432

Reichheld FF, Kenny DW (1990) The hidden advantages of customer retention. J Retail Bank 12(4):19–24

Romānova I, Grima S, Spiteri J, Kudinska M (2018) The payment services directive 2 and competitiveness: the perspective of European Fintech companies. Eur Res Stud J 21(2):5–24

Modigliani F, Miller MH (1959) The cost of capital, corporation finance, and the theory of investment: reply. Am Econ Rev 49(4):655–669

Schumpeter J (1911) The theory of economic development. Harvard Econ Stud XLVI

Song F, Thakor AV (2010) Financial system architecture and the co-evolution of banks and capital markets. Econ J 120(547):1021–1055

Swankie GDB, Broby D (2019) Examining the impact of artificial intelligence on the evaluation of banking risk. Centre for Financial Regulation and Innovation, white paper

Thakor AV (2020) Fintech and banking: What do we know? J Financ Intermed 41:100833

Vishnu S, Agochiya V, Palkar R (2017) Data-centered dependencies and opportunities for robotics process automation in banking. J Financ Transf 45(1):68–76

Williams MD (2018) Social commerce and the mobile platform: payment and security perceptions of potential users. Comput Hum Behav 115:105557

Download references

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowldgements.

There was no funding associated with this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Financial Regulation and Innovation, Strathclyde Business School, Glasgow, UK

Daniel Broby

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author confirms the contribution is original and his own. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Broby .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

I declare I have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Broby, D. Financial technology and the future of banking. Financ Innov 7 , 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-021-00264-y

Download citation

Received : 21 January 2021

Accepted : 09 June 2021

Published : 18 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-021-00264-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cryptocurrencies

- P2P Lending

- Intermediation

- Digital Payments

JEL Classifications

Please log in to DSpace

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, investigating the role of fintech in the banking industry: what do we know.

European Journal of Innovation Management

ISSN : 1460-1060

Article publication date: 31 March 2022

Issue publication date: 29 August 2023

In recent years, the penetration of digital technologies in the financial industry determined the arising of Fintech, which generated a dynamic and rapid change that business operators and supervisory authorities in the banking industry are struggling to follow it. This is especially due to issues affecting financial intermediaries and customers, and potential risks of stability of the financial system. The aim of this paper is to provide a review of Fintech in the banking industry thus to update the knowledge about technology innovation in the banking sector, identify the major trends in the domain and delineate future research directions.

Design/methodology/approach

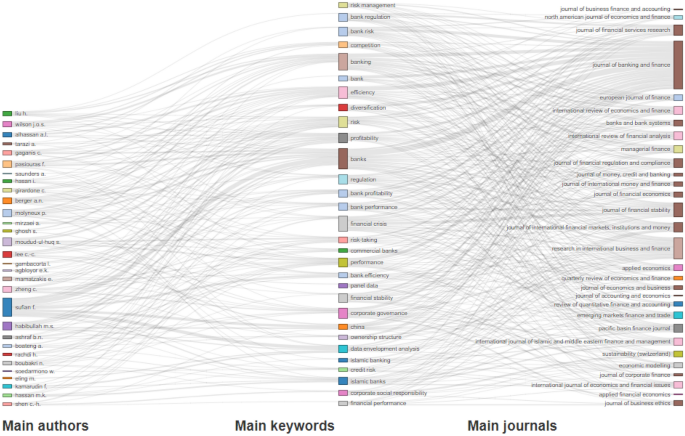

The study reviews 377 articles indexed on Scopus from 2014 to 2021 that focus on Fintech and the banking industry. The methodology adopted is structured in two steps: the keywords selection and the analysis of the documents extracted. The first step identified “Fintech” and “bank” as keywords to be searched within the title, abstract or keywords of documents indexed on Scopus; whereas the second step combined R and VOSviewer to provide a descriptive analysis of the dataset and the analysis of keywords and occurrences, respectively.

Results achieved in the study allow providing a systemic view of the Fintech in the banking industry, including the emergent phenomenon of digital banking. In particular, it is provided with a general overview and descriptive information on the entire sample of documents analyzed, their authors, the keywords used and the most cited works. Besides, a deepening on the model of digital banking is provided, by delineating the six dimensions of the key effects generated by the digital bank model.

Originality/value

Two main elements of originality characterize this study. The first one is related to the fact that few review studies have been published on Fintech in the banking industry, and the second one concerns the multiple dimensions of the impact of Fintech in the banking sector, which includes customer, company, bank, regulation authority and society.

- Financial technologies

- Financial services

Acknowledgements

The author(s) thank the Consorzio Universitario Interprovinciale Salentino (CUIS) for supporting this research.

Elia, G. , Stefanelli, V. and Ferilli, G.B. (2023), "Investigating the role of Fintech in the banking industry: what do we know?", European Journal of Innovation Management , Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 1365-1393. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2021-0608

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Open access

- Published: 03 September 2022

A literature review of risk, regulation, and profitability of banks using a scientometric study

- Shailesh Rastogi 1 ,

- Arpita Sharma 1 ,

- Geetanjali Pinto 2 &

- Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9757-1904 1 , 3

Future Business Journal volume 8 , Article number: 28 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

This study presents a systematic literature review of regulation, profitability, and risk in the banking industry and explores the relationship between them. It proposes a policy initiative using a model that offers guidelines to establish the right mix among these variables. This is a systematic literature review study. Firstly, the necessary data are extracted using the relevant keywords from the Scopus database. The initial search results are then narrowed down, and the refined results are stored in a file. This file is finally used for data analysis. Data analysis is done using scientometrics tools, such as Table2net and Sciences cape software, and Gephi to conduct network, citation analysis, and page rank analysis. Additionally, content analysis of the relevant literature is done to construct a theoretical framework. The study identifies the prominent authors, keywords, and journals that researchers can use to understand the publication pattern in banking and the link between bank regulation, performance, and risk. It also finds that concentration banking, market power, large banks, and less competition significantly affect banks’ financial stability, profitability, and risk. Ownership structure and its impact on the performance of banks need to be investigated but have been inadequately explored in this study. This is an organized literature review exploring the relationship between regulation and bank performance. The limitations of the regulations and the importance of concentration banking are part of the findings.

Introduction

Globally, banks are under extreme pressure to enhance their performance and risk management. The financial industry still recalls the ignoble 2008 World Financial Crisis (WFC) as the worst economic disaster after the Great Depression of 1929. The regulatory mechanism before 2008 (mainly Basel II) was strongly criticized for its failure to address banks’ risks [ 47 , 87 ]. Thus, it is essential to investigate the regulation of banks [ 75 ]. This study systematically reviews the relevant literature on banks’ performance and risk management and proposes a probable solution.

Issues of performance and risk management of banks

Banks have always been hailed as engines of economic growth and have been the axis of the development of financial systems [ 70 , 85 ]. A vital parameter of a bank’s financial health is the volume of its non-performing assets (NPAs) on its balance sheet. NPAs are advances that delay in payment of interest or principal beyond a few quarters [ 108 , 118 ]. According to Ghosh [ 51 ], NPAs negatively affect the liquidity and profitability of banks, thus affecting credit growth and leading to financial instability in the economy. Hence, healthy banks translate into a healthy economy.

Despite regulations, such as high capital buffers and liquidity ratio requirements, during the second decade of the twenty-first century, the Indian banking sector still witnessed a substantial increase in NPAs. A recent report by the Indian central bank indicates that the gross NPA ratio reached an all-time peak of 11% in March 2018 and 12.2% in March 2019 [ 49 ]. Basel II has been criticized for several reasons [ 98 ]. Schwerter [ 116 ] and Pakravan [ 98 ] highlighted the systemic risk and gaps in Basel II, which could not address the systemic risk of WFC 2008. Basel III was designed to close the gaps in Basel II. However, Schwerter [ 116 ] criticized Basel III and suggested that more focus should have been on active risk management practices to avoid any impending financial crisis. Basel III was proposed to solve these issues, but it could not [ 3 , 116 ]. Samitas and Polyzos [ 113 ] found that Basel III had made banking challenging since it had reduced liquidity and failed to shield the contagion effect. Therefore, exploring some solutions to establish the right balance between regulation, performance, and risk management of banks is vital.

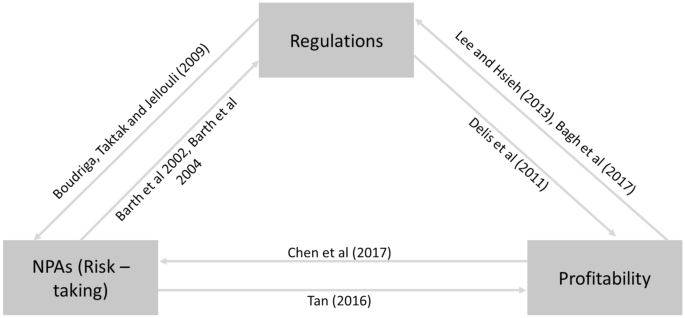

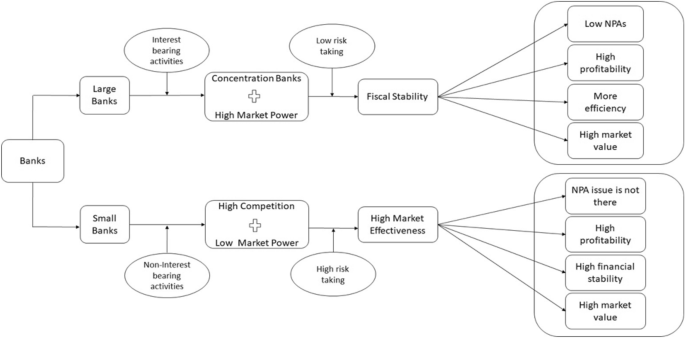

Keeley [ 67 ] introduced the idea of a balance among banks’ profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking). This study presents the balancing act of profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking) of banks as a probable solution to the issues of bank performance and risk management and calls it a triad . Figure 1 illustrates the concept of a triad. Several authors have discussed the triad in parts [ 32 , 96 , 110 , 112 ]. Triad was empirically tested in different countries by Agoraki et al. [ 1 ]. Though the idea of a triad is quite old, it is relevant in the current scenario. The spirit of the triad strongly and collectively admonishes the Basel Accord and exhibits new and exhaustive measures to take up and solve the issue of performance and risk management in banks [ 16 , 98 ]. The 2008 WFC may have caused an imbalance among profitability, regulation, and risk-taking of banks [ 57 ]. Less regulation , more competition (less profitability ), and incentive to take the risk were the cornerstones of the 2008 WFC [ 56 ]. Achieving a balance among the three elements of a triad is a real challenge for banks’ performance and risk management, which this study addresses.

Triad of Profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking). Note The triad [ 131 ] of profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking) is shown in Fig. 1

Triki et al. [ 130 ] revealed that a bank’s performance is a trade-off between the elements of the triad. Reduction in competition increases the profitability of banks. However, in the long run, reduction in competition leads to either the success or failure of banks. Flexible but well-expressed regulation and less competition add value to a bank’s performance. The current review paper is an attempt to explore the literature on this triad of bank performance, regulation, and risk management. This paper has the following objectives:

To systematically explore the existing literature on the triad: performance, regulation, and risk management of banks; and

To propose a model for effective bank performance and risk management of banks.

Literature is replete with discussion across the world on the triad. However, there is a lack of acceptance of the triad as a solution to the woes of bank performance and risk management. Therefore, the findings of the current papers significantly contribute to this regard. This paper collates all the previous studies on the triad systematically and presents a curated view to facilitate the policy makers and stakeholders to make more informed decisions on the issue of bank performance and risk management. This paper also contributes significantly by proposing a DBS (differential banking system) model to solve the problem of banks (Fig. 7 ). This paper examines studies worldwide and therefore ensures the wider applicability of its findings. Applicability of the DBS model is not only limited to one nation but can also be implemented worldwide. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the publication pattern in banking using a blend of scientometrics analysis tools, network analysis tools, and content analysis to understand the link between bank regulation, performance, and risk.

This paper is divided into five sections. “ Data and research methods ” section discusses the research methodology used for the study. The data analysis for this study is presented in two parts. “ Bibliometric and network analysis ” section presents the results obtained using bibliometric and network analysis tools, followed by “ Content Analysis ” section, which presents the content analysis of the selected literature. “ Discussion of the findings ” section discusses the results and explains the study’s conclusion, followed by limitations and scope for further research.

Data and research methods

A literature review is a systematic, reproducible, and explicit way of identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing relevant research produced and published by researchers [ 50 , 100 ]. Analyzing existing literature helps researchers generate new themes and ideas to justify the contribution made to literature. The knowledge obtained through evidence-based research also improves decision-making leading to better practical implementation in the real corporate world [ 100 , 129 ].

As Kumar et al. [ 77 , 78 ] and Rowley and Slack [ 111 ] recommended conducting an SLR, this study also employs a three-step approach to understand the publication pattern in the banking area and establish a link between bank performance, regulation, and risk.

Determining the appropriate keywords for exploring the data

Many databases such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus are available to extract the relevant data. The quality of a publication is associated with listing a journal in a database. Scopus is a quality database as it has a wider coverage of data [ 100 , 137 ]. Hence, this study uses the Scopus database to extract the relevant data.

For conducting an SLR, there is a need to determine the most appropriate keywords to be used in the database search engine [ 26 ]. Since this study seeks to explore a link between regulation, performance, and risk management of banks, the keywords used were “risk,” “regulation,” “profitability,” “bank,” and “banking.”

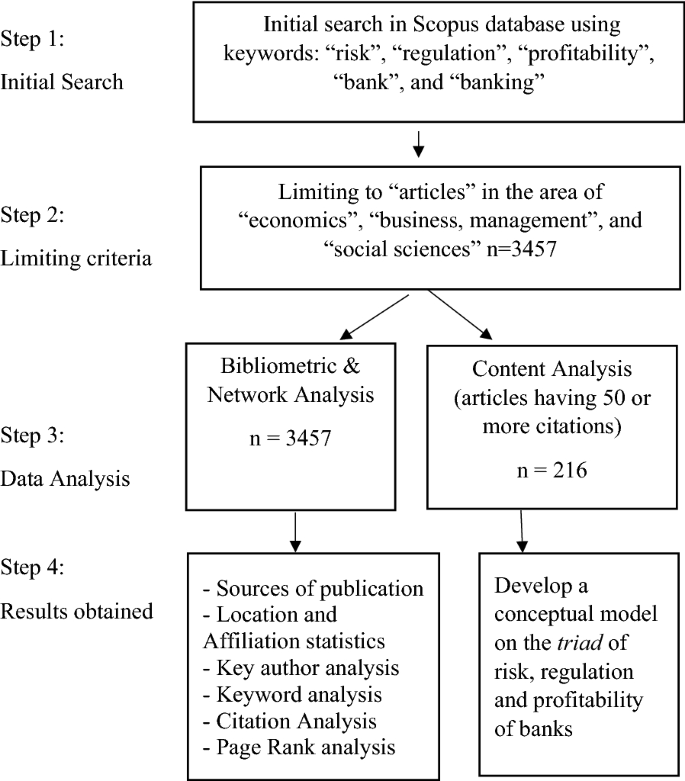

Initial search results and limiting criteria

Using the keywords identified in step 1, the search for relevant literature was conducted in December 2020 in the Scopus database. This resulted in the search of 4525 documents from inception till December 2020. Further, we limited our search to include “article” publications only and included subject areas: “Economics, Econometrics and Finance,” “Business, Management and Accounting,” and “Social sciences” only. This resulted in a final search result of 3457 articles. These results were stored in a.csv file which is then used as an input to conduct the SLR.

Data analysis tools and techniques

This study uses bibliometric and network analysis tools to understand the publication pattern in the area of research [ 13 , 48 , 100 , 122 , 129 , 134 ]. Some sub-analyses of network analysis are keyword word, author, citation, and page rank analysis. Author analysis explains the author’s contribution to literature or research collaboration, national and international [ 59 , 99 ]. Citation analysis focuses on many researchers’ most cited research articles [ 100 , 102 , 131 ].

The.csv file consists of all bibliometric data for 3457 articles. Gephi and other scientometrics tools, such as Table2net and ScienceScape software, were used for the network analysis. This.csv file is directly used as an input for this software to obtain network diagrams for better data visualization [ 77 ]. To ensure the study’s quality, the articles with 50 or more citations (216 in number) are selected for content analysis [ 53 , 102 ]. The contents of these 216 articles are analyzed to develop a conceptual model of banks’ triad of risk, regulation, and profitability. Figure 2 explains the data retrieval process for SLR.

Data retrieval process for SLR. Note Stepwise SLR process and corresponding results obtained

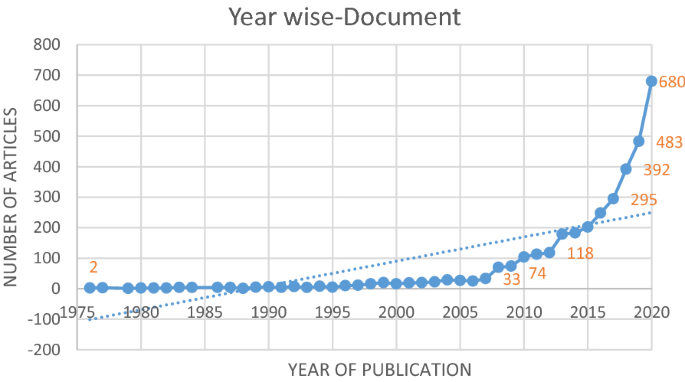

Bibliometric and network analysis

Figure 3 [ 58 ] depicts the total number of studies that have been published on “risk,” “regulation,” “profitability,” “bank,” and “banking.” Figure 3 also depicts the pattern of the quality of the publications from the beginning till 2020. It undoubtedly shows an increasing trend in the number of articles published in the area of the triad: “risk” regulation” and “profitability.” Moreover, out of the 3457 articles published in the said area, 2098 were published recently in the last five years and contribute to 61% of total publications in this area.

Articles published from 1976 till 2020 . Note The graph shows the number of documents published from 1976 till 2020 obtained from the Scopus database

Source of publications

A total of 160 journals have contributed to the publication of 3457 articles extracted from Scopus on the triad of risk, regulation, and profitability. Table 1 shows the top 10 sources of the publications based on the citation measure. Table 1 considers two sets of data. One data set is the universe of 3457 articles, and another is the set of 216 articles used for content analysis along with their corresponding citations. The global citations are considered for the study from the Scopus dataset, and the local citations are considered for the articles in the nodes [ 53 , 135 ]. The top 10 journals with 50 or more citations resulted in 96 articles. This is almost 45% of the literature used for content analysis ( n = 216). Table 1 also shows that the Journal of Banking and Finance is the most prominent in terms of the number of publications and citations. It has 46 articles published, which is about 21% of the literature used for content analysis. Table 1 also shows these core journals’ SCImago Journal Rank indicator and H index. SCImago Journal Rank indicator reflects the impact and prestige of the Journal. This indicator is calculated as the previous three years’ weighted average of the number of citations in the Journal since the year that the article was published. The h index is the number of articles (h) published in a journal and received at least h. The number explains the scientific impact and the scientific productivity of the Journal. Table 1 also explains the time span of the journals covering articles in the area of the triad of risk, regulation, and profitability [ 7 ].

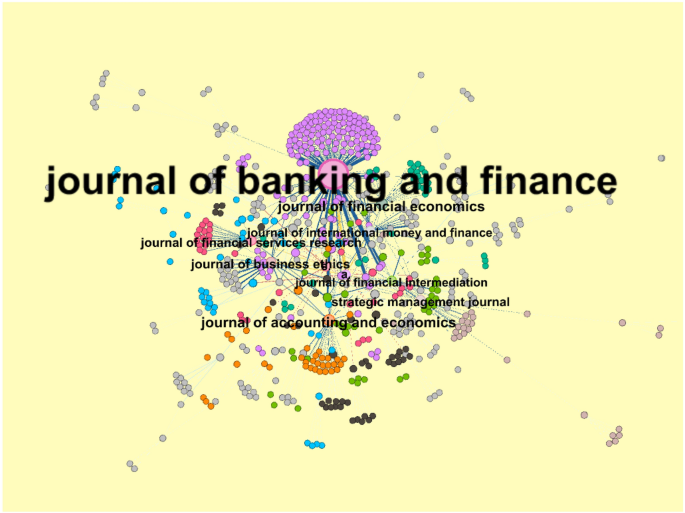

Figure 4 depicts the network analysis, where the connections between the authors and source title (journals) are made. The network has 674 nodes and 911 edges. The network between the author and Journal is classified into 36 modularities. Sections of the graph with dense connections indicate high modularity. A modularity algorithm is a design that measures how strong the divided networks are grouped into modules; this means how well the nodes are connected through a denser route relative to other networks.

Network analysis between authors and journals. Note A node size explains the more linked authors to a journal

The size of the nodes is based on the rank of the degree. The degree explains the number of connections or edges linked to a node. In the current graph, a node represents the name of the Journal and authors; they are connected through the edges. Therefore, the more the authors are associated with the Journal, the higher the degree. The algorithm used for the layout is Yifan Hu’s.

Many authors are associated with the Journal of Banking and Finance, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Financial Economics, Journal of Financial Services Research, and Journal of Business Ethics. Therefore, they are the most relevant journals on banks’ risk, regulation, and profitability.

Location and affiliation analysis

Affiliation analysis helps to identify the top contributing countries and universities. Figure 5 shows the countries across the globe where articles have been published in the triad. The size of the circle in the map indicates the number of articles published in that country. Table 2 provides the details of the top contributing organizations.

Location of articles published on Triad of profitability, regulation, and risk

Figure 5 shows that the most significant number of articles is published in the USA, followed by the UK. Malaysia and China have also contributed many articles in this area. Table 2 shows that the top contributing universities are also from Malaysia, the UK, and the USA.

Key author analysis

Table 3 shows the number of articles written by the authors out of the 3457 articles. The table also shows the top 10 authors of bank risk, regulation, and profitability.

Fadzlan Sufian, affiliated with the Universiti Islam Malaysia, has the maximum number, with 33 articles. Philip Molyneux and M. Kabir Hassan are from the University of Sharjah and the University of New Orleans, respectively; they contributed significantly, with 20 and 18 articles, respectively.

However, when the quality of the article is selected based on 50 or more citations, Fadzlan Sufian has only 3 articles with more than 50 citations. At the same time, Philip Molyneux and Allen Berger contributed more quality articles, with 8 and 11 articles, respectively.

Keyword analysis

Table 4 shows the keyword analysis (times they appeared in the articles). The top 10 keywords are listed in Table 4 . Banking and banks appeared 324 and 194 times, respectively, which forms the scope of this study, covering articles from the beginning till 2020. The keyword analysis helps to determine the factors affecting banks, such as profitability (244), efficiency (129), performance (107, corporate governance (153), risk (90), and regulation (89).