- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Editorial article, editorial: doing critical health communication: a forum on methods.

- 1 Department of Communication, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, United States

- 2 Department of Communication, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, United States

Editorial on the Research Topic “Doing” Critical Health Communication. A Forum on Methods

The assumed premise of health communication research is straightforward: improving communication processes across all health-related domains. Communication between providers and patients, public health messaging, health literacy training, culturally competent healthcare, health status sharing in families, workplaces, and small groups can all fit within the broad definition of health communication. However, philosophical differences in what communication means–or for that matter, what health means–result in a complex, multi-paradigmatic field of study. For instance, viewing communication primarily as information transfer leads to a different trajectory of research and scholarship than a view of communication as the constitutive process of meaning making. Similarly, conceptualizing health as a means of achieving social concordance or even control vs. as a site of social struggle leads us different places.

Within the well-established field of health communication, a preponderance of published research continues to be rooted in communication models that derive from social psychology and information science. Consequently, emerging issues, new theoretical and methodological directions, and ethical challenges define the landscape of the field. For instance, we have witnessed a significant rise in interpretive research focusing on the social construction of meaning. However, we believe there is more work to do in nurturing critical health communication [CHC] perspectives.

The primary rationale for this research topic was to describe multiple ways to engage in CHC methodologies through a set of short, “how-to” articles. The original impetus were two roundtable panels (convened at successive National Communication Association conventions) to gauge the trajectory of CHC in the decade after Zoller and Kline’s review of the contributions of interpretive/critical health communication research in the Annals of Communication (then called Communication Yearbook). One of the things we recognized in those panel discussions was that CHC was still considered a niche sub-discipline or area within health communication, and consequently, students and young scholars who were interested in CHC often did not receive formal guidance in this area, notwithstanding the dramatic increases in CHC-fueled work being published in our disciplinary journals, and/or presented at conferences. Even for scholars familiar with the intellectual terrains of poststructuralism, postcolonialism, the “linguistic turn,” hermeneutics, phenomenology and critical theory, there was a gap in documenting these theoretical concepts into concrete ways of “doing” health communication research.

In calling for papers, we urged potential authors to ask, “What makes your work critical?” How do methodological practices illuminate the role of critique? What are the ontological and epistemological implications of doing CHC? How is CHC related to critical praxis? How does “doing” critical work engage with/deviate from the broader interpretive move toward discourses/texts? What do recent provocations around the “return to the material” in Communication scholarship mean for CHC researchers? How is CHC situated to respond to widening racial, gendered and other social disparities in health across the globe? Finally, how do CHC researchers situate their own privilege and conceptualize embodied risk through their work? The fourteen articles that comprise this collection, selected from the 30 + abstracts submitted for consideration, and shortlisted from 19 full-text article submissions) respond to this prompt in unique, individual ways.

Of the fourteen articles, five report on new/original research, four offer ‘Conceptual Analysis’ or brief essays on a particular concept. Another four are short “Perspectives” on varying issues concerning CHC, and one is a Brief Research Report. As to our remit of a “how to” for CHC, the articles offer pedagogical insights on CHC methods in a variety of ways.

Zoller and Kline’s 2008 drew attention to both shared attributes and key points of difference in interpretive and critical health communication. One of our goals for this topic was to theorize their differences as well as their “blurry edges.” Anne Kerber’s essay addresses longstanding conflicts between a critical “hermeneutic” of suspicion that interrogates relations of power and an affirmative stance that seeks positive models of critical social change.

A second rationale for this collection was to re-establish the disciplinary history of the efforts of CHC scholars. At the abovementioned conference panel discussions and through our own anecdotal experience, we have learnt that the multi-decade project to critique, de-parochialize, globalize and queer the body of the discipline (and consequently, its journals and editorial boards), led by women, scholars of color, LGBTQ scholars, and scholars from the Global South, has not been documented or set into the received intellectual history of the field (in contrast to cognate areas, like critical organizational or critical management studies). This absence influences the diffusion of our work. It also makes it possible for other scholarly collectives, notably our colleagues who coalesce under the “Rhetoric of Health and Medicine” or RHM, whose work we admire, review and support, to largely ignore this history and the contributions of CHC scholars in opening up space for critical/humanist inquiry in this area. In that sense, we seek to make explicit the politics, the pragmatics and the real-life implications of doing CHC work. As a foundational scholar in the area, Heather Zoller’s essay derives from her extensive work in the field, and outlines how the politics of academic training, visibility, and publishing intersect in pursuing a trajectory of critical health communication research. This essay is an excellent entry point for this research topic.

Essays in this collection model different forms of critical analysis. For instance, Carter and Alexander’s original research is an exemplar for connecting race, class, historical positioning, and health communication practices. Their interview-based original research highlights the voices of African American farmers, revealing how their issues and interests have been silenced in discussions about United States farming. They connect these erasures with broader political discourses about diet and health disparities.

Khan et al model critical ethnographic analysis through their study of Ashodaya Samithi , a sex worker collective in Mysore, India. They offer narratives that highlight resistance and alliance building that are imperative in order to invert dominant discriminatory notions of nationhood and citizenship that have and continue to violate health and rights of marginalized communities. Much of the critical work in health communication has emerged from the global South, espousing a critique of the West-dominated nature of communication theorizing and global health policies.

Dutta and his team provide a primer in a Marxist approach to critical theorizing, with attention to the global subaltern. The authors draw from their embodied culture-centered research engaging in activist interventions that aim to disrupt Whiteness and associated capitalist and colonial logics. The authors challenge us to consider what counts as resistance organizing in ways that provide an interesting counterpoint to Kerber’s essay. Such tensions in what counts as “critical” research in health communication continues to be an important fault line in our field. Metatheoretical differences in conceptualizing the role of the critic in health communication manifest in methodological and pragmatic differences in what research looks like. One such difference is in the practice of what some scholas call ‘critical reflexivity’

Critical reflexivity–or the continual introspection of how analysis reveals the motivations of the analyst as much as it says something about that which is analyzed–is a governing principle guiding the ethical conduct of critical research. Rebecca de Souza’s essay interrogates how the literature on critical reflexivity–what she calls the “self-other” hyphen—predicates a white researcher introspecting on their ethical analytical practices as they work in communities of color. However, flipping the trope, de Souza’s essay offers a fascinating look at what happens when a person of color navigates analysis of predominantly white spaces. Through an analysis of the responses and challenges to her work by peer reviewers, commentators and colleagues, de Souza offers a window into the “micro-politics” of knowledge production. Her work offers practical suggestions for scholars of color to challenge the hegemonic assumptions that emerge from working in white spaces.

Similarly, Leandra Hernandez and Sarah De Los Santos Upton provide an exemplar of the power of critical reflexivity and the need for critical praxis through social justice activism. The essay blends discussion of their research and activist work, describing the intersectional approach they have taken to health communication research at the United States-Mexico border. Situated as Chicana feminists, they have investigated gendered, racial and class constructions in the context of reproductive justice, violence, and immigration. The authors describe how their work has necessitated a blending of theoretical and methodological approaches.

Critical reflexivity is also an important tool in Smita Misra’s essay , which centers around the concept of migrant trauma. As encapsulated by their experiences in a participatory theater project that purportedly allowed for refugees to cope with trauma, Misra offers a critical reflexive account of how well-meaning, “participatory”/critical projects can offer limited/constraining understanding of the lives of the vulnerable populations they serve.

Nicole Hudak’s essay discusses challenges in publishing research that does not fit within post-positivism, calling for more advocacy of qualitative and critical research. In addition, the essay challenges all of us to interrogate reviewer practices that reinforce heteronormativity and create barriers to research addressing LGBTQ + health care experiences. This turn to embodied identity is further crystallized in Ellingson’s work, which theorizes embodiment more centrally.

Embodiment becomes sensorial in Laura Ellingson’s essay. Sensual intersubjectivities that blend the senses, the motors, and the material, Ellingson explains, are crucial to critical health communication research methods because interrupting discourses on/of what makes certain bodies/citizens ‘healthy’ and ‘normal’ calls for a sustained practice of sensorial reflexivity.

If critical reflexivity is one way to redefine the “blurry edges” between interpretive and critical approaches, then Sastry and Basu’s essay offers a methodological warrant to use critical reflexivity as a practicable method for analysis in health communication. The essay elucidates an approach blending culture-centered analysis, abductive analysis, and critical reflexivity in a post-COVID world. Departing from their ethnographic work in the culture-centered tradition, the authors offer a framework to analyze health discourses using the early responses to COVID-19 as an exemplar.

Several essays offer methodological innovations in the doing of critical health research. Sarah MacLean and Simon Hatcher write about the walkthrough method in their essay. The walkthrough method offers a viable process to scrutinize the architecture of a health technology tools –- the BEACON Rx Platform in their case –in terms of expected use and consequent implications of access and equity. This method also creates spaces for questioning the discourses inherent in health technologies that frame dominant understandings of how to be in “good” health.

Wendy Pringle provides a new methodological tool for critical health communication scholars, particularly those interested in textual/rhetorical analysis and policy discourses. She adapts the “What's the Problem Represented to be?” (WPR) approach from the field of discursive policy analysis. The paper uses the illustrative example of the legalization of medical assistance in dying in Canada. The WPR method facilitates attention to evolving discourses of problem constructions, and she describes the implications for people with disabilities, including what is said and what is left unspoken. The method addresses social change, including policy critique, and advocacy as a form of resistance.

In our call for papers, we hoped to collectively articulate (and complicate) what exactly we mean by “critical” in CHC. In addition to the models we have discussed, Kim Kline and Shamshad Khan call attention to the need for CHC scholars to speak to both internal and external stakeholders. Their essay signposts the possibilities and challenges for CHC scholars to engage in “transdisciplinary” collaborations within and without the discipline of health communication.

Speaking of collaborations, this research topic would not have been realized without the collaborative efforts between the contributing authors, the editorial team, and most importantly, the large number of reviewers who volunteered their time and intellectual commitment to this cause–not to mention adapting their reviewing practices for Frontiers. While open-access, transparency, and publication of reviewers’ names with published articles signals the timely democratization of the publication process, the concomitant “bot-tification” of the process was a learning curve for several Communication scholars–us included.

As we conclude this editorial, the United States has more than 13 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, and some estimates suggest that the death toll might reach 5,00,000 by the summer of 2021. Debates around masks, vaccines, technology transfers, economic impacts and racial and income inequalities related to the pandemic continue, painfully demonstrate the need for more research in how mechanisms of power/control/inequality shape individual and collective experiences of health and illness.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Keywords: health communication, critical health studies, research methods, reflexivity, critical health communication

Citation: Sastry S, Zoller HM and Basu A (2021) Editorial: Doing Critical Health Communication: A Forum on Methods. Front. Commun. 5:637579. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.637579

Received: 03 December 2020; Accepted: 24 December 2020; Published: 25 January 2021.

Edited and reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Sastry, Zoller and Basu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shaunak Sastry, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

'Doing' Critical Health Communication: A Forum on Methods

Health Communication Research Paper Topics

Community Health Issues

- Change Agency

- Collective Efficacy

- Community Mobilization

- Community Organizing as a Research Approach

- Community Participation

- Community-Based Participatory Research

- Comprehensive Community Initiatives

- Conflict Management: Health Professionals

- Cultural Differences

- Health Activism and Public Health

- Immigrant Families

- Media Literacy

- Nature, Environment, and Sustainability

- Organizational and Public Policy Barriers

- Readiness Assessments

- Rural Health Communication

- Sex Workers

- Social Action, Types of

- Social Aggregates

- Social Capital

- Social Determinants of Health

- University–Community Relationships

End-of-Life Issues

- Advance Directives

- Advanced Aging Communities

- Bereavement

- Communicating Bad News

- Death and Dying

- Family Communication and End of Life

- Final Conversations

- Palliative Care

- Pediatric Hospice Care

- Rhetoric: Death with Dignity

- Staff Communication in Nursing Homes

- Terminality

Evaluation of Health Intervention, Education, and Communication

- Content Analysis

- Data Mining

- Focus Groups

- Logic Models and Program Evaluation

- Measurement Problems

- Message Quality Measurement

- Mixed Methods of Evaluation

- Modeling Development and Testing

- New Technologies and Intervention Evaluation Methodology

- Qualitative Methods of Evaluation

- Quantitative Methods of Evaluation

- Risk Communication

- Risk Society

- Setting Objectives in Health Communication and Intervention

- Statistical Challenges in Evaluation

Everyday and Family Health Communication Issues

- Adolescent Substance Abuse Prevention

- Alcohol and Health Decision Making

- Childhood Injury Prevention

- Communication with Families

- Consequences of Health Literacy

- Consequences of Stigmatization

- Coping with Stigmatization

- Courtesy Stigma

- Cross-Generational Health Communication

- Decision Making

- Disabilities and Family Relationships

- Everyday Health Communication

- Familial Roles in Health Communication

- Family Caregiving

- Family Meeting

- Family Planning

- Family Relationship to Health

- Grief and Loss

- Health Communication with Children

- Health Education

- Health Literacy and Numeracy

- Health Transition and Family Communication

- Illness Identity

- Improving Health Literacy

- Integrating Health Literacy into Health Care Systems

- Measurement of Health Literacy

- Model of Health Literacy

- Mother–Daughter Dyad Communication

- Online Health Literacy

- Religion and Spirituality

- Social Construction of Disability

- Social Identity

- Social Influence of Everyday Health Communication

- Social Norms

- Social Support and Cardiovascular Health

- Social Support and Health

- Social Support and Support Groups

- Social Support Interventions

- Stigma Reduction

- Stigmatization

- Stigmatization, Labels, Marks, and Peril

- Surrogate Decision Makers

- Teen Pregnancy

- Types of Social Support

- Unintended Effects of Health Communication

- Health Campaigns

- Advertising of Dietary Supplements

- Advertising of Food

- Advertising of Over-the-Counter Drugs

- Advertising of Prescription Drugs

- Affordable Care Act

- Assessment of Health Campaigns

- Awareness and Instruction Strategies

- Campaign Effects Versus Effectiveness

- Campaigns in Developing Countries

- Channels and Formats

- Communication Complex

- Communication for Behavioral Impact

- Crisis Communication

- Disease Prevention

- Dissemination

- Emotion Appraisals Regarding Risk

- Evidence Role in Health Campaigns

- Formative Evaluation

- Governmental Regulation of Advertising

- Incentive Appeals

- Influential Source Messengers

- Integrated Marketing Mix

- Interpersonal Communication and Mass Media Health Campaigns

- Message Design

- Message Sidedness

- Message Tailoring

- Optimistic Bias

- Perceived Threat

- Program Strategies: Campaigns

- Public Service Announcements

- Risk Communication and Food Safety

- Risk Perceptions

- Risk-Taking Behavior

- Segmentation of Health Campaigns

- Sensation-Seeking Targeting

- Social Marketing

International and Diversity Issues in Health Communication

- Conflict and Negative Health Effects

- Cultural Sensitivity

- Discrimination or Bias in Health Care

- Disenfranchised Populations

- Ethnic Diversity in Health Care Settings

- Health Disparities in Clinical Interactions

- Health Disparities on Communal Level

- Human Rights

- Immigrant Populations

- Intercultural Health Communication

- Islamic Healing

- LGBT Issues

- Marginalized Populations

- Overall Health Disparities

- Personal Influences on Health Disparities

- Public Health Intervention in Multicultural Communities

- Relational Influences on Health Disparities

- Solutions for Health Disparities

- Structure-Centered Approach

Health Information

- Defensive Reactions to Health Messages

- Digital Divide

- Disclosure and Family Health History

- Disclosure and Medical Errors

- Disclosure and Providers and Patients

- Emotion and Information Seeking

- Explaining Illness

- Expressive Writing and Health

- Health Citizenship

- Health Communication Curricula

- Information Nonseeking

- Information Seeking

- Information Sharing

- Need for Explaining Illness

- Online Health Information Seeking

- Online Health Information Sharing

- Opinion Leaders

- Psychosocial Determinants of Health Information-Seeking Behavior

- Social Determinants of Health Information-Seeking Behavior

- History of Health Communication

- Basic Concepts of Communication

- Communication Across the Lifespan

- Communication Networks

- E-Health Defined

- Evolution of Medicine as Business

- Health Information Channels

- Patient and Relationship-Centered Communication and Medicine

- Personalized Medicine

- Postcolonial Studies and Health

- Premises of Health Communication

- Science Communication

- Translational Research

Media Content

- Advertising Unhealthy Foods to Children

- Body Images and Portrayals

- Celebrity Cancer Announcements

- Celebrity Endorsements

- Critical Analysis of Media and Health

- Digital Media

- Entertainment–Education

- European Approach to Entertainment–Education

- Health Blogging

- Health Consequences of Pornography

- Health Journalism

- Health Promotion

- Hollywood and Public Relations Approach to Entertainment–Education

- Ideological Hegemony

- Impact of Media Content

- Institutional Processes and Competing Agendas

- Interpretation and Effects of Disclaimers

- Media and Health Disparities

- Media and Quality of Health Information

- Media Content: Magazines

- Media Content: Newspapers

- Media Content: Other Print

- Media Content: Televised Entertainment

- Media Content: Televised News

- Media Coverage of Genetically Modified Organisms

- Media Depictions of Disability

- Media Depictions of Medical Workers

- Media Depictions of Mental Illnesses

- Moderating Variables and Audience Effects

- Music in Health Behavior

- Obesity and Mass Media

- Pathways to Change Tool

- Public Relations and Health Journalism

- Public Relations and Health Promotion

- Public Relations and Social Media

- Reaching Audiences

- Role of Involvement in Entertainment–Education

- Social Marketing and Community Change Perspective

- Twitter and Public Health

Organizational Issues and Health Policy

- Adult Children of Alcoholics

- American Medical Association

- Conflict Management and Health Professionals

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Health Care Teams

- Health Policy

- Healthy People Initiative

- Hospital Governance Culture

- Informed Consent

- Interdisciplinary Health Services Research

- Mediated Health Campaigns

- Multicultural Campaigns

- National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy

- National Cancer Institute

- National Institutes of Health

- National Library of Medicine

- National Medical Association

- Organizations and Health

- Patient Privacy

- Politics and Political Complexities

- Public Relations and Health Care Organizations

- Role Stress

- Segmentation and Public Relations

- Stress and Burnout

- Stress and Burnout: Emotional Labor

- Stress and Burnout: Home–Work Conflict

- Three Community and Five Cities Projects

- S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Working Well

- World Health Organization

Provider–Patient Interaction

- Adherence to Medical Regimens

- Anger Appeals

- Clinical Trial Participation

- Coding Health Interaction

- Collaborative Decision Making

- Contested Illnesses

- Conversation Analysis

- Decision Making Between Support Providers and Persons with Disabilities

- Dependent Variables Derived from Critical Health Outcomes

- Difficult Patients

- Discourse and Health

- Doctor–Patient Communication

- Emergency Rooms

- Emotions and the Medical Care Process

- Face and Politeness

- Health Care Environment

- HIV Test Counseling

- Identification

- Interactional Context and Intervention

- Interpersonal Communication Skills

- Interpreters and Language

- Interviewing in the Health Care Context

- Language and Negation Bias in Doctor–Patient Interaction

- Language Brokering

- Listening in Health Care Interactions

- Malpractice Litigation

- Medical Outcomes

- Nonverbal Communication in Health Care Settings

- Open Dialogue Approach

- Overtreatment and Overreliance on Diagnostic Testing

- Pathways to Health Outcomes

- Patient Activation

- Patient Education and Hospital Discharge and Readmission

- Patient Empowerment

- Patient Navigators and Family Advisors

- Patient Safety

- Patients and Communication Skills Training:

- Prescribing Medications

- Providers and Communication Skills Training and Assessment

- Quality of Life as a Health Outcome

- Satisfaction

- Shared Mind in Collaborative Decision Making:

- Supportive Listening

- Uncertainty in Collaborative Decision Making

- Public Health Communication

- Biopreparedness and Biosecurity

- Climate Change

- Communication of Scientific Complexity

- Developmental Health

- Disaster Relief

- Emergency Preparedness and Response

- Environmental Health

- Evolution of Public Health Communication

- Flu Vaccine Rhetoric

- HIV/AIDS Prevention

- Immunizations

- Memorable Messages

- Mother-to-Child HIV/AIDS Transmission

- Newborn Care

- Online Health Information Credibility

- Priming in Health Campaign Messages

- Public Engagement and Science Policy

- Public Health and Academic Partnerships

- Public Understanding of Research

- Public Understanding of Science

- Research in Environmental Health

- School Health

- Science Literacy

- Sexual Health

- Warning Labels

- Warning Labels on Alcohol

- Warning Labels on Cigarettes

- Warning Labels on Prescription Drugs

- Women’s Health

- Work Site Safety

Specific Health Issues/Providers

- Child and Spousal Abuse

- Acupuncture

- Age-Related Hearing Loss

- Alternative and Complementary Medicine

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ayurveda, Yoga, and Meditation

- Bioterrorism

- Birth Control and Contraception

- Breast Cancer

- Breastfeeding

- Bullying and Cyberbullying

- Cancer Risk Communication

- Cancer Survivorship

- Chronic Diseases

- Communication Interventions

- Contraception

- Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

- Distance Caregiving

- Drug and Alcohol Abuse Minimization

- Eating Disorders

- Emergency Health Communication

- Enhancement

- Gambling Addiction

- Heart Health

- HIV/AIDS and Disclosure Dilemmas

- HIV/AIDS Treatment

- HIV/AIDS, Condom Use, and Meanings

- Holistic Medicine

- Human Papillomavirus

- Influenza A Virus Subtype H1N1

- Integrative Medicine

- Internet Addiction

- Language, Metaphors, and Social Construction of HIV/AIDS

- Malaria and Mosquito Nets

- Male Circumcision

- Mammography

- Meanings of HIV/AIDS Test

- Mental Health

- Military Health

- Military Sexual Assault

- Multilevel Interventions

- Neurorhetoric

- Nutrition and Diet

- Oral Health and Dentistry

- Organ Donation

- Pharmacists

- Physical Activity and Weight

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prenatal Health Promotion

- Prostate Cancer

- Responses to Slow-Motion Technological Disaster

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

- Sex Education

- Sexual Assault

- Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention

- Skin Cancer and Sun Safety

- Skin Cancer and Tanning

- Social Determinants of Disparities in HIV/AIDS

- Transitions, Health Effects, and Support

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Tuberculosis

- Vaccinations

Technology and Health Communication

- Biomedical and Health Informatics

- Bundled Interventions

- Communication Technology Theoretical Frameworks

- Computer-Tailored Interventions

- Customization as Tailoring 2.0

- Digital Personal Health Records

- Electronic Medical Records

- Free-Standing Computer Kiosks

- Geographic Information Systems Technology

- Internet and Information Acquisition

- Medical Body Implants

- Mobile Health

- New Reproductive Technologies

- Online Focus Groups

- Online Health Information Exchange and Privacy

- Online Support Groups

- Online Support Groups Advantages and Disadvantages

- Persuasive Technologies for Health

- Secondary Data Analysis

- Social Media

- Technology and Health Outcomes

- Technology Impact on Physician–Patient Dialogue

- Telemedicine

- Virtual Reality Environments

- Weak Tie/Strong Tie Network Support

- Web-Based Delivery

Health Communication Theories, Ethics, and Philosophy

- Acculturation

- Action Tendency Emotions

- Acute Versus Preventive Care

- Affection Exchange Theory

- Agenda Setting

- Amputee Wannabes

- Attribution Theory and Attribution Error

- Biological Citizenship

- Biopower and Biopolitics

- Care Model and Productive Interaction

- Change Approaches

- Communication Accommodation Theory

- Communication Privacy Management Theory

- Communication Theory of Identity

- Community Resilience

- Control Theory

- Critical Approaches

- Cultivation Theory

- Cultural Variance Model

- Culture-Centered Approaches

- Cyberchondria

- Diffusion of Innovations Model

- Double ABC-X Model of Family Stress and Coping

- Dual-Processing Models

- Ecological Perspectives

- Encoded Exposure and Aided Versus Unaided Awareness

- Ethic of Care

- Ethics and Health Campaigns

- Ethics and Health Communication Strategies

- Ethics and New Technologies

- Ethics of Provider–Patient Interaction

- Ethnography

- Ethnomethodology

- Fear Appeals and the Extended Parallel Process Model

- Generative Tensions in Health Communication Theory

- Globalization Theory

- Grounded Theory

- Harm Reduction Theory

- Health Belief Model

- Health Communication Ethics

- Health Locus of Control

- Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture

- Inconsistent Nurturing as Control Theory

- Inoculation Effects

- Instructional Principles of Risk Communication

- Invisible Disabilities

- Loose Versus Tight Coupling

- Measurement of Social Networks

- Media Complementarity Theory

- Medicalization

- Message Sensation Value

- Meta-Analysis

- Motivational Interviewing

- Multilevel Modeling

- Narrative Engagement Theory

- Narrative Medicine

- Narratives and Barrier Reduction

- Narratives and Health Campaigns

- Narratives and Social Marketing

- Negotiated Morality Theory

- Olson’s Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems

- Organization–Public Relations Theory

- O-S-O-R Model

- Perceived Effectiveness

- Phenomenology

- Placebo Effects

- Problematic Integration Theory

- Problem-Based Learning

- Psychological Reactance

- Psychometric Theory and Reliability/Validity of Measures

- Reconceptualized Health Belief Model

- Relational Dialectics Theory

- Relational Health Communication Competence Model

- Rhetoric, Health, and Medicine

- Risk Information Seeking and Processing Model

- Risk Perception Attitude Framework

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Situational Theory and Communication Behaviors

- Social Cognitive Theory

- Social Comparison Theory

- Social Construction of Reality

- Social Construction Perspective on Risk Communication

- Social Judgment Theory

- Social Networks

- Social Networks and Message Delivery

- Societal Risk Reduction Motivation Model

- Sociometric Social Networks

- Structural Violence and Health

- Systems Theory

- Theory of Motivated Information Management

- Theory of Normative Social Behavior

- Theory of Planned Behavior

- Theory of Reasoned Action

- Traditions of Health Communication Theory

- Trait Approaches

- Uncertainty Management Theory

- Uses and Gratifications Theory

- Weick’s Model of Organizing

Organization of the Field

There is no simple or complete way to organize the field of health communication, though several sub-fields have existed depending on one’s research interests, as well as adventitious and historical circumstances. At the individual level, the focus is twofold: (1) how health cognitions affect, and behaviors influence and are influenced by, health communications; and (2) how interpersonal interactions between patients, family members, and providers, and with members of their social network, influence health outcomes. At the organizational level, some have studied the role of communication within health-care systems and how organization of the media and the practices of media professionals may influence population and individual health.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

Finally, at the societal level, the focus is on large-scale social changes and the role of communication with such changes. For example, one might examine how strategic communications as well as natural diffusion of information impact individual and population health; or how communication mediates and is influenced by social determinants such as social class, neighborhood, social cohesion and conflict, social and economic policies, and how that impacts individual and population health.

Even as these levels provide a useful organizing framework, two caveats are warranted. First, policymaking and research related to health may affect more than one level. Second, interest in a level of analysis and pursuit of work at one level is not inconsequential. Locating a problem at one level, and studying it at that level, have implications for the kind of policy or practice that is likely to emerge from that research.

Interpersonal Communication

Extensive attention has been given to understanding the consequences of communication between physicians and patients on patient satisfaction, adherence, and quality of life. One theme is who controls the interaction between providers and patients, known as ‘relational control.’ A second theme focuses on the outcomes of patient– provider interactions. Extensive research has documented that patient–provider communication influences patient satisfaction which, in turn, is related to patient adherence and compliance to treatment regimens, ease of distress, physiological response, length of stay in the hospital, quality of life, and health status, among others. Third, researchers have documented stark differences in patient preparation and access, and in care received and health outcomes, between social classes as well as racial and ethnic groups.

The implications of interpersonal interaction in the context of families, friends, co-workers, and voluntary associations on health outcomes have become one of the most dynamic areas of research in health communication. This topic has been pursued from diverse theoretical viewpoints by researchers focusing on social networks, social support, family communications, and social capital based on the researcher’s disciplinary origins and research interests. In addition to social support, social networks can accelerate or decelerate diffusion of new information, and also influence how it is interpreted (Himelboim & Han 2014). Members within networks can serve as role models for lifestyle behaviors such as smoking and obesity. The emergence and spread of the Internet have broadened the scope of interpersonal interaction and its influence in health communication by moderating the limits of geography.

Mass Media and Health

The incidental and routine use of media for news and entertainment serves four functions in health. (1) The informational function is served when casual use of media for news or other purposes may expose the audience to developments on new treatments or new drugs, alert them to risk factors, or warn them of impending threats such as avian flu; (2) media serve an instrumental function by providing information that facilitates action; e.g., in times of natural disasters the audience may learn about places where they should take shelter, and information of this kind allows for practical action; (3) media defines what is acceptable and legitimate, performing a social control function; (4) the communal function is served when media provide social support, generate social capital, and connect people to social institutions and groups.

Information seeking, as a construct, has gained greater currency in recent times as more information on health has become routinely available because of greater coverage of health in the media, the spread of health-related content on the world wide web, or the consumerist movement in health that promotes informed or shared decision-making. It is widely assumed that under certain conditions some people actively look for health information to seek a second opinion, make a more informed choice on treatments, and learn in greater depth about a health problem that afflicts them or their friends or family members.

The most visible and popular means of strategic communications is through health campaigns which have become a critical arsenal in health promotion. A typical health campaign attempts to promote change by increasing the amount of information on the health topic, and by defining the issue of interest in such a way as to promote health or prevent disease. Recent reviews of the vast literature on health campaigns have identified conditions under which health campaigns can be successful (e.g. Noar 2006; Randolph & Viswanath 2004).

Emerging Challenges/Dimensions

First, the combined impact of computers and telecommunications on society has been transformative, impinging on almost every facet of human life including art, culture, science, and education. Consumer informatics integrates consumer information needs and preferences with clinical systems to empower patients to take charge of their healthcare, bring down costs, and improve quality of care. For example, the integration of electronic medical records with communications should facilitate communications between patients and providers, send automatic reminders to patients to stay on schedule, and help patients navigate the health-care system. Second, technological developments are coinciding with the consumerist movement in health-care. The paternalistic model that characterized the physician–patient relationship is slowly being complemented by alternative models such as shared/informed decisionmaking models (SDM/IDM) or patient-centered communication (PCC). Third, the significant investments in biomedical research enterprise in the developing world, and movement toward more evidence- based medicine, have led to calls for translation of the knowledge from the laboratory to the clinic and the community. Lastly, an urgent and a moral imperative in health is addressing the profound inequities in access to health-care and the disproportionate burden of disease faced by certain groups.

References:

- Epstein, R. M. & Street, R. L., Jr. (2007). Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. NIH Publication no. 07–6225. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

- Glanz, K., Rimer, B., & Viswanath, K. (eds.) (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Himelboim, I. & Han, J. Y. (2014). Cancer talk on twitter: Community structure and information sources in breast and prostate cancer social networks. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives, 19(2), 210–225.

- Hornik, R. (ed.) (2002). Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- McCauley, M., Blake, K., Meissner, H., & Viswanath, K. (2013). The social group influences of U.S. health journalists and their impact on the newsmaking process. Health Education Research, 28(20), 339–51.

- Noar, S. M. (2006). A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: Where do we go from here? Journal of Health Communication, 11, 21–42.

- Obregon, R. & Waisbord, S. (eds.) (2012). The handbook of global health communication. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Parker, J. C. & Thorson, E. (2008). Health communication in the new media landscape. New York: Springer.

- Randolph, W. & Viswanath, K. (2004). Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: Marketing health in a crowded media world. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 419–37.

- Snyder, L. B. & Hamilton, M. A. (2002). A meta-analysis of U.S. health campaign effects on behavior: Emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information, and beware of secular trend. In R. Hornik (ed.), Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 357–383.

- Viswanath, K. (2005). The communications revolution and cancer control. Nature Reviews Cancer, 5(10), 828–835.

Back to Communication Research Paper Topics .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

Long-term weight loss effects of semaglutide in obesity without diabetes in the SELECT trial

- Donna H. Ryan 1 ,

- Ildiko Lingvay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7006-7401 2 ,

- John Deanfield 3 ,

- Steven E. Kahn 4 ,

- Eric Barros ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6613-4181 5 ,

- Bartolome Burguera 6 ,

- Helen M. Colhoun ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8345-3288 7 ,

- Cintia Cercato ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6181-4951 8 ,

- Dror Dicker 9 ,

- Deborah B. Horn 10 ,

- G. Kees Hovingh 5 ,

- Ole Kleist Jeppesen 5 ,

- Alexander Kokkinos 11 ,

- A. Michael Lincoff ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8175-2121 12 ,

- Sebastian M. Meyhöfer 13 ,

- Tugce Kalayci Oral 5 ,

- Jorge Plutzky ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7194-9876 14 ,

- André P. van Beek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0335-8177 15 ,

- John P. H. Wilding ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2839-8404 16 &

- Robert F. Kushner 17

Nature Medicine ( 2024 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

1 Citations

2154 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Medical research

In the SELECT cardiovascular outcomes trial, semaglutide showed a 20% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events in 17,604 adults with preexisting cardiovascular disease, overweight or obesity, without diabetes. Here in this prespecified analysis, we examined effects of semaglutide on weight and anthropometric outcomes, safety and tolerability by baseline body mass index (BMI). In patients treated with semaglutide, weight loss continued over 65 weeks and was sustained for up to 4 years. At 208 weeks, semaglutide was associated with mean reduction in weight (−10.2%), waist circumference (−7.7 cm) and waist-to-height ratio (−6.9%) versus placebo (−1.5%, −1.3 cm and −1.0%, respectively; P < 0.0001 for all comparisons versus placebo). Clinically meaningful weight loss occurred in both sexes and all races, body sizes and regions. Semaglutide was associated with fewer serious adverse events. For each BMI category (<30, 30 to <35, 35 to <40 and ≥40 kg m − 2 ) there were lower rates (events per 100 years of observation) of serious adverse events with semaglutide (43.23, 43.54, 51.07 and 47.06 for semaglutide and 50.48, 49.66, 52.73 and 60.85 for placebo). Semaglutide was associated with increased rates of trial product discontinuation. Discontinuations increased as BMI class decreased. In SELECT, at 208 weeks, semaglutide produced clinically significant weight loss and improvements in anthropometric measurements versus placebo. Weight loss was sustained over 4 years. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03574597 .

Similar content being viewed by others

Effects of a personalized nutrition program on cardiometabolic health: a randomized controlled trial

Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 5 trial

What is the pipeline for future medications for obesity?

The worldwide obesity prevalence, defined by body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg m − 2 , has nearly tripled since 1975 (ref. 1 ). BMI is a good surveillance measure for population changes over time, given its strong correlation with body fat amount on a population level, but it may not accurately indicate the amount or location of body fat at the individual level 2 . In fact, the World Health Organization defines clinical obesity as ‘abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health’ 1 . Excess abnormal body fat, especially visceral adiposity and ectopic fat, is a driver of cardiovascular (CV) disease (CVD) 3 , 4 , 5 , and contributes to the global chronic disease burden of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cancer and other chronic conditions 6 , 7 .

Remediating the adverse health effects of excess abnormal body fat through weight loss is a priority in addressing the global chronic disease burden. Improvements in CV risk factors, glycemia and quality-of-life measures including personal well-being and physical functioning generally begin with modest weight loss of 5%, whereas greater weight loss is associated with more improvement in these measures 8 , 9 , 10 . Producing and sustaining durable and clinically significant weight loss with lifestyle intervention alone has been challenging 11 . However, weight-management medications that modify appetite can make attaining and sustaining clinically meaningful weight loss of ≥10% more likely 12 . Recently, weight-management medications, particularly those comprising glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, that help people achieve greater and more sustainable weight loss have been developed 13 . Once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, is approved for chronic weight management 14 , 15 , 16 and at doses of up to 2.0 mg is approved for type 2 diabetes treatment 17 , 18 , 19 . In patients with type 2 diabetes and high CV risk, semaglutide at doses of 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg has been shown to significantly lower the risk of CV events 20 . The SELECT trial (Semaglutide Effects on Heart Disease and Stroke in Patients with Overweight or Obesity) studied patients with established CVD and overweight or obesity but without diabetes. In SELECT, semaglutide was associated with a 20% reduction in major adverse CV events (hazard ratio 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 0.90; P < 0.001) 21 . Data derived from the SELECT trial offer the opportunity to evaluate the weight loss efficacy, in a geographically and racially diverse population, of semaglutide compared with placebo over 208 weeks when both are given in addition to standard-of-care recommendations for secondary CVD prevention (but without a focus on targeting weight loss). Furthermore, the data allow examination of changes in anthropometric measures such as BMI, waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) as surrogates for body fat amount and location 22 , 23 . The diverse population can also be evaluated for changes in sex- and race-specific ‘cutoff points’ for BMI and WC, which have been identified as anthropometric measures that predict cardiometabolic risk 8 , 22 , 23 .

This prespecified analysis of the SELECT trial investigated weight loss and changes in anthropometric indices in patients with established CVD and overweight or obesity without diabetes, who met inclusion and exclusion criteria, within a range of baseline categories for glycemia, renal function and body anthropometric measures.

Study population

The SELECT study enrolled 17,604 patients (72.3% male) from 41 countries between October 2018 and March 2021, with a mean (s.d.) age of 61.6 (8.9) years and BMI of 33.3 (5.0) kg m − 2 (ref. 21 ). The baseline characteristics of the population have been reported 24 . Supplementary Table 1 outlines SELECT patients according to baseline BMI categories. Of note, in the lower BMI categories (<30 kg m − 2 (overweight) and 30 to <35 kg m − 2 (class I obesity)), the proportion of Asian individuals was higher (14.5% and 7.4%, respectively) compared with the proportion of Asian individuals in the higher BMI categories (BMI 35 to <40 kg m − 2 (class II obesity; 3.8%) and ≥40 kg m − 2 (class III obesity; 2.2%), respectively). As the BMI categories increased, the proportion of women was higher: in the class III BMI category, 45.5% were female, compared with 20.8%, 25.7% and 33.0% in the overweight, class I and class II categories, respectively. Lower BMI categories were associated with a higher proportion of patients with normoglycemia and glycated hemoglobin <5.7%. Although the proportions of patients with high cholesterol and history of smoking were similar across BMI categories, the proportion of patients with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥2.0 mg dl −1 increased as the BMI category increased. A high-sensitivity C-reactive protein >2.0 mg dl −1 was present in 36.4% of patients in the overweight BMI category, with a progressive increase to 43.3%, 57.3% and 72.0% for patients in the class I, II and III obesity categories, respectively.

Weight and anthropometric outcomes

Percentage weight loss.

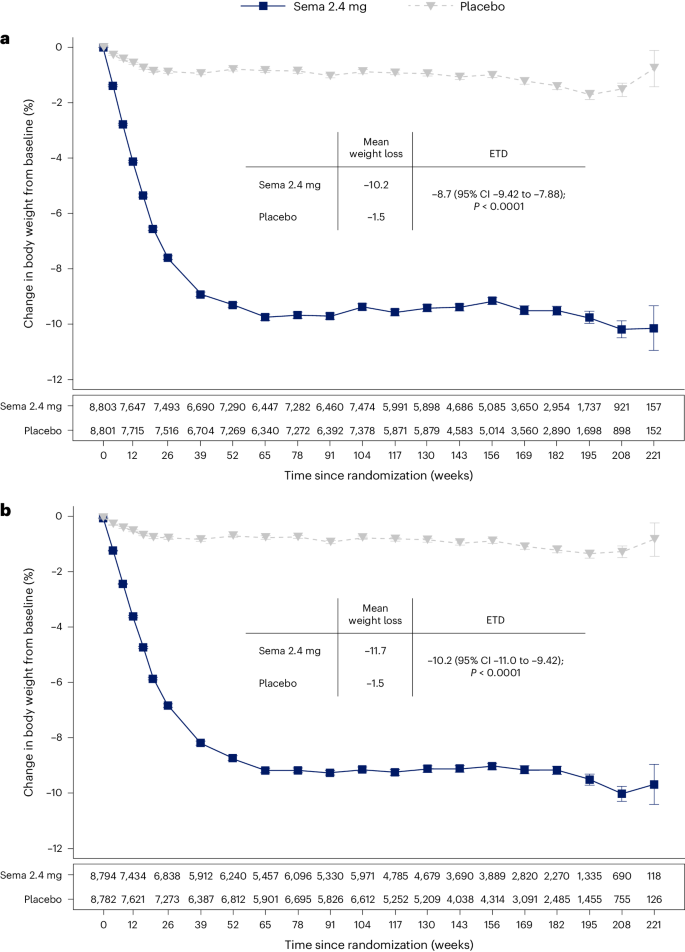

The average percentage weight-loss trajectories with semaglutide and placebo over 4 years of observation are shown in Fig. 1a (ref. 21 ). For those in the semaglutide group, the weight-loss trajectory continued to week 65 and then was sustained for the study period through week 208 (−10.2% for the semaglutide group, −1.5% for the placebo group; treatment difference −8.7%; 95% CI −9.42 to −7.88; P < 0.0001). To estimate the treatment effect while on medication, we performed a first on-treatment analysis (observation period until the first time being off treatment for >35 days). At week 208, mean weight loss in the semaglutide group analyzed as first on-treatment was −11.7% compared with −1.5% for the placebo group (Fig. 1b ; treatment difference −10.2%; 95% CI −11.0 to −9.42; P < 0.0001).

a , b , Observed data from the in-trial period ( a ) and first on-treatment ( b ). The symbols are the observed means, and error bars are ±s.e.m. Numbers shown below each panel represent the number of patients contributing to the means. Analysis of covariance with treatment and baseline values was used to estimate the treatment difference. Exact P values are 1.323762 × 10 −94 and 9.80035 × 10 −100 for a and b , respectively. P values are two-sided and are not adjusted for multiplicity. ETD, estimated treatment difference; sema, semaglutide.

Categorical weight loss and individual body weight change

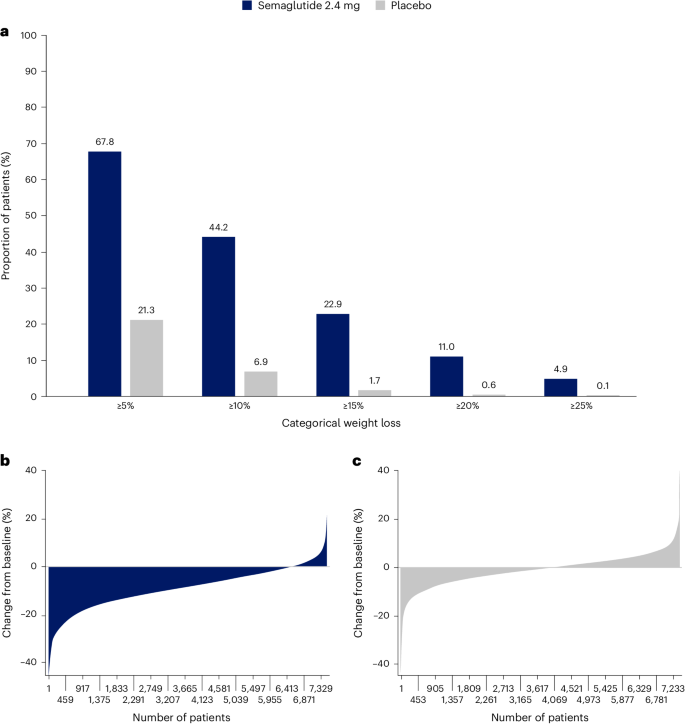

Among in-trial (intention-to-treat principle) patients at week 104, weight loss of ≥5%, ≥10%, ≥15%, ≥20% and ≥25% was achieved by 67.8%, 44.2%, 22.9%, 11.0% and 4.9%, respectively, of those treated with semaglutide compared with 21.3%, 6.9%, 1.7%, 0.6% and 0.1% of those receiving placebo (Fig. 2a ). Individual weight changes at 104 weeks for the in-trial populations for semaglutide and placebo are depicted in Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c , respectively. These waterfall plots show the variation in weight-loss response that occurs with semaglutide and placebo and show that weight loss is more prominent with semaglutide than placebo.

a , Categorical weight loss from baseline at week 104 for semaglutide and placebo. Data from the in-trial period. Bars depict the proportion (%) of patients receiving semaglutide or placebo who achieved ≥5%, ≥10%, ≥15%, ≥20% and ≥25% weight loss. b , c , Percentage change in body weight for individual patients from baseline to week 104 for semaglutide ( b ) and placebo ( c ). Each patient’s percentage change in body weight is plotted as a single bar.

Change in WC

WC change from baseline to 104 weeks has been reported previously in the primary outcome paper 21 . The trajectory of WC change mirrored that of the change in body weight. At week 208, average reduction in WC was −7.7 cm with semaglutide versus −1.3 cm with placebo, with a treatment difference of −6.4 cm (95% CI −7.18 to −5.61; P < 0.0001) 21 .

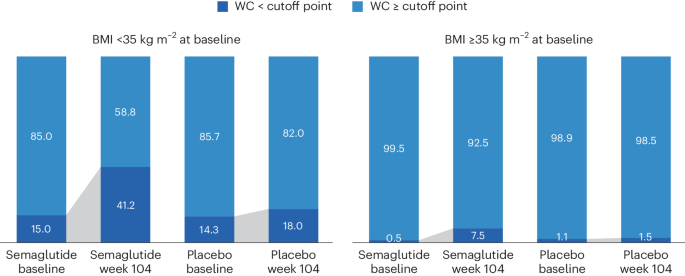

WC cutoff points

We analyzed achievement of sex- and race-specific cutoff points for WC by BMI <35 kg m − 2 or ≥35 kg m − 2 , because for BMI >35 kg m − 2 , WC is more difficult technically and, thus, less accurate as a risk predictor 4 , 25 , 26 . Within the SELECT population with BMI <35 kg m − 2 at baseline, 15.0% and 14.3% of the semaglutide and placebo groups, respectively, were below the sex- and race-specific WC cutoff points. At week 104, 41.2% fell below the sex- and race-specific cutoff points for the semaglutide group, compared with only 18.0% for the placebo group (Fig. 3 ).

WC cutoff points; Asian women <80 cm, non-Asian women <88 cm, Asian men <88 cm, non-Asian men <102 cm.

Waist-to-height ratio

At baseline, mean WHtR was 0.66 for the study population. The lowest tertile of the SELECT population at baseline had a mean WHtR <0.62, which is higher than the cutoff point of 0.5 used to indicate increased cardiometabolic risk 27 , suggesting that the trial population had high WCs. At week 208, in the group randomized to semaglutide, there was a relative reduction of 6.9% in WHtR compared with 1.0% in placebo (treatment difference −5.87% points; 95% CI −6.56 to −5.17; P < 0.0001).

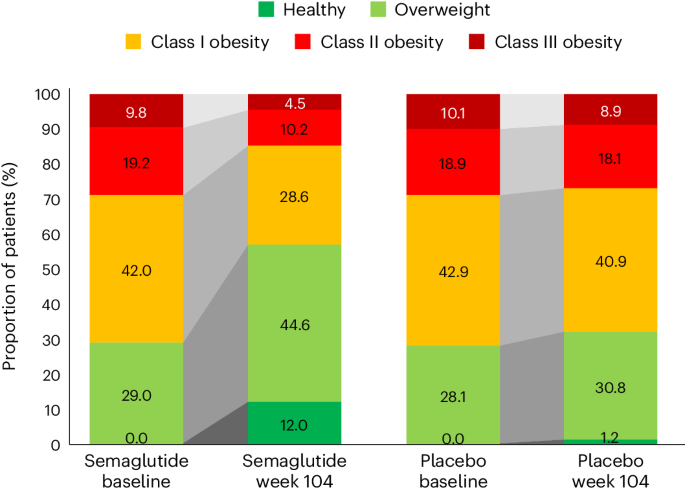

BMI category change

At week 104, 52.4% of patients treated with semaglutide achieved improvement in BMI category compared with 15.7% of those receiving placebo. Proportions of patients in the BMI categories at baseline and week 104 are shown in Fig. 4 , which depicts in-trial patients receiving semaglutide and placebo. The BMI category change reflects the superior weight loss with semaglutide, which resulted in fewer patients being in the higher BMI categories after 104 weeks. In the semaglutide group, 12.0% of patients achieved a BMI <25 kg m − 2 , which is considered the healthy BMI category, compared with 1.2% for placebo; per study inclusion criteria, no patients were in this category at baseline. The proportion of patients with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg m − 2 ) fell from 71.0% to 43.3% in the semaglutide group versus 71.9% to 67.9% in the placebo group.

In the semaglutide group, 12.0% of patients achieved normal weight status at week 104 (from 0% at baseline), compared with 1.2% (from 0% at baseline) for placebo. BMI classes: healthy (BMI <25 kg m − 2 ), overweight (25 to <30 kg m − 2 ), class I obesity (30 to <35 kg m − 2 ), class II obesity (35 to <40 kg m − 2 ) and class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg m − 2 ).

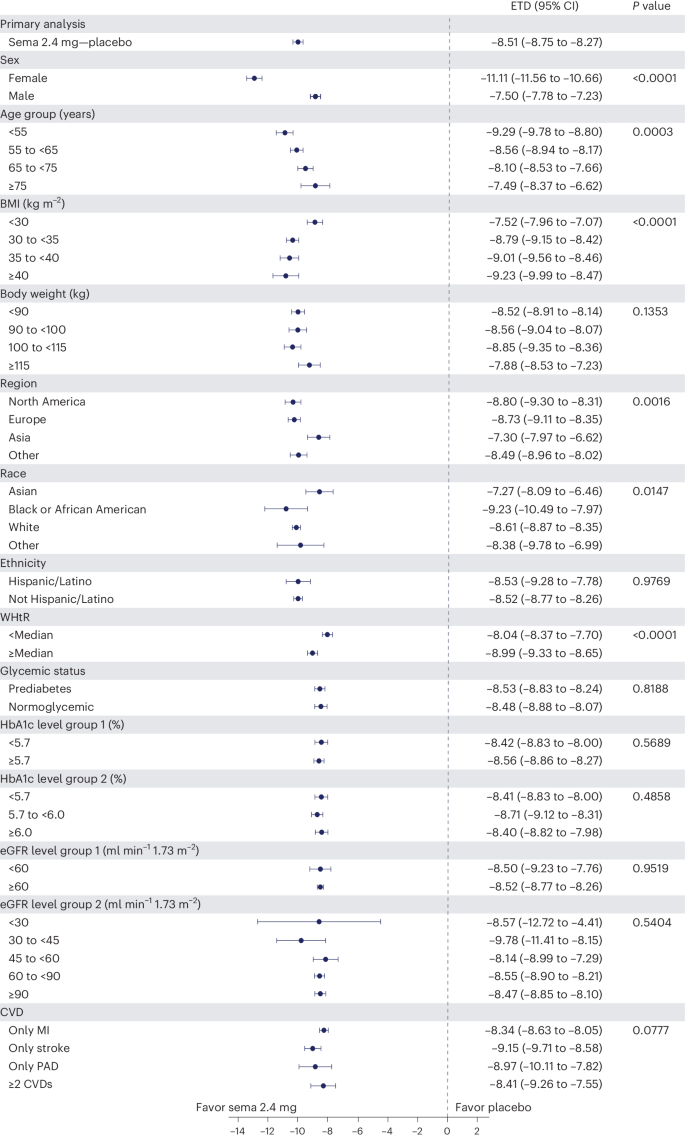

Weight and anthropometric outcomes by subgroups

The forest plot illustrated in Fig. 5 displays mean body weight percentage change from baseline to week 104 for semaglutide relative to placebo in prespecified subgroups. Similar relationships are depicted for WC changes in prespecified subgroups shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 . The effect of semaglutide (versus placebo) on mean percentage body weight loss as well as reduction in WC was found to be heterogeneous across several population subgroups. Women had a greater difference in mean weight loss with semaglutide versus placebo (−11.1% (95% CI −11.56 to −10.66) versus −7.5% in men (95% CI −7.78 to −7.23); P < 0.0001). There was a linear relationship between age category and degree of mean weight loss, with younger age being associated with progressively greater mean weight loss, but the actual mean difference by age group is small. Similarly, BMI category had small, although statistically significant, associations. Those with WHtR less than the median experienced slightly lower mean body weight change than those above the median, with estimated treatment differences −8.04% (95% CI −8.37 to −7.70) and −8.99% (95% CI −9.33 to −8.65), respectively ( P < 0.0001). Patients from Asia and of Asian race experienced slightly lower mean weight loss (estimated treatment difference with semaglutide for Asian race −7.27% (95% CI −8.09 to −6.46; P = 0.0147) and for Asia −7.30 (95% CI −7.97 to −6.62; P = 0.0016)). There was no difference in weight loss with semaglutide associated with ethnicity (estimated treatment difference for Hispanic −8.53% (95% CI −9.28 to −7.76) or non-Hispanic −8.52% (95% CI −8.77 to 8.26); P = 0.9769), glycemic status (estimated treatment difference for prediabetes −8.53% (95% CI −8.83 to −8.24) or normoglycemia −8.48% (95% CI −8.88 to −8.07; P = 0.8188) or renal function (estimated treatment difference for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 or ≥60 ml min −1 1.73 m − 2 being −8.50% (95% CI −9.23 to −7.76) and −8.52% (95% CI −8.77 to −8.26), respectively ( P = 0.9519)).

Data from the in-trial period. N = 17,604. P values represent test of no interaction effect. P values are two-sided and are not adjusted for multiplicity. The dots show estimated treatment differences, and the error bars show 95% CIs. Details of the statistical models are available in Methods . ETD, estimated treatment difference; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease; sema, semaglutide.

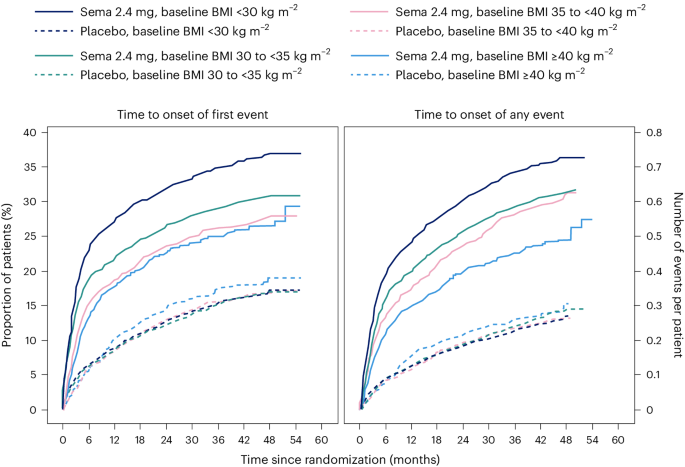

Safety and tolerability according to baseline BMI category

We reported in the primary outcome of the SELECT trial that adverse events (AEs) leading to permanent discontinuation of the trial product occurred in 1,461 patients (16.6%) in the semaglutide group and 718 patients (8.2%) in the placebo group ( P < 0.001) 21 . For this analysis, we evaluated the cumulative incidence of AEs leading to trial product discontinuation by treatment assignment and by BMI category (Fig. 6 ). For this analysis, with death modeled as a competing risk, we tracked the proportion of in-trial patients for whom drug was withdrawn or interrupted for the first time (Fig. 6 , left) or cumulative discontinuations (Fig. 6 , right). Both panels of Fig. 6 depict a graded increase in the proportion discontinuing semaglutide, but not placebo. For lower BMI classes, discontinuation rates are higher in the semaglutide group but not the placebo group.

Data are in-trial from the full analysis set. sema, semaglutide.

We reported in the primary SELECT analysis that serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported by 2,941 patients (33.4%) in the semaglutide arm and by 3,204 patients (36.4%) in the placebo arm ( P < 0.001) 21 . For this study, we analyzed SAE rates by person-years of treatment exposure for BMI classes (<30 kg m − 2 , 30 to <35 kg m − 2 , 35 to <40 kg m − 2 , and ≥40 kg m − 2 ) and provide these data in Supplementary Table 2 . We also provide an analysis of the most common categories of SAEs. Semaglutide was associated with lower SAEs, primarily driven by CV event and infections. Within each obesity class (<30 kg m − 2 , 30 to <35 kg m − 2 , 35 to <40 kg m − 2 , and ≥40 kg m − 2 ), there were fewer SAEs in the group receiving semaglutide compared with placebo. Rates (events per 100 years of observation) of SAEs were 43.23, 43.54, 51.07 and 47.06 for semaglutide and 50.48, 49.66, 52.73 and 60.85 for placebo, with no evidence of heterogeneity. There was no detectable difference in hepatobiliary or gastrointestinal SAEs comparing semaglutide with placebo in any of the four BMI classes we evaluated.

The analyses of weight effects of the SELECT study presented here reveal that patients assigned to once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg lost significantly more weight than those receiving placebo. The weight-loss trajectory with semaglutide occurred over 65 weeks and was sustained up to 4 years. Likewise, there were similar improvements in the semaglutide group for anthropometrics (WC and WHtR). The weight loss was associated with a greater proportion of patients receiving semaglutide achieving improvement in BMI category, healthy BMI (<25 kg m − 2 ) and falling below the WC cutoff point above which increased cardiometabolic risk for the sex and race is greater 22 , 23 . Furthermore, both sexes, all races, all body sizes and those from all geographic regions were able to achieve clinically meaningful weight loss. There was no evidence of increased SAEs based on BMI categories, although lower BMI category was associated with increased rates of trial product discontinuation, probably reflecting exposure to a higher level of drug in lower BMI categories. These data, representing the longest clinical trial of the effects of semaglutide versus placebo on weight, establish the safety and durability of semaglutide effects on weight loss and maintenance in a geographically and racially diverse population of adult men and women with overweight and obesity but not diabetes. The implications of weight loss of this degree in such a diverse population suggests that it may be possible to impact the public health burden of the multiple morbidities associated with obesity. Although our trial focused on CV events, many chronic diseases would benefit from effective weight management 28 .

There were variations in the weight-loss response. Individual changes in body weight with semaglutide and placebo were striking; still, 67.8% achieved 5% or more weight loss and 44.2% achieved 10% weight loss with semaglutide at 2 years, compared with 21.3% and 6.9%, respectively, for those receiving placebo. Our first on-treatment analysis demonstrated that those on-drug lost more weight than those in-trial, confirming the effect of drug exposure. With semaglutide, lower BMI was associated with less percentage weight loss, and women lost more weight on average than men (−11.1% versus −7.5% treatment difference from placebo); however, in all cases, clinically meaningful mean weight loss was achieved. Although Asian patients lost less weight on average than patients of other races (−7.3% more than placebo), Asian patients were more likely to be in the lowest BMI category (<30 kg m − 2 ), which is known to be associated with less weight loss, as discussed below. Clinically meaningful weight loss was evident in the semaglutide group within a broad range of baseline categories for glycemia and body anthropometrics. Interestingly, at 2 years, a significant proportion of the semaglutide-treated group fell below the sex- and race-specific WC cutoff points, especially in those with BMI <35 kg m − 2 , and a notable proportion (12.0%) fell below the BMI cutoff point of 25 kg m − 2 , which is deemed a healthy BMI in those without unintentional weight loss. As more robust weight loss is possible with newer medications, achieving and maintaining these cutoff point targets may become important benchmarks for tracking responses.

The overall safety profile did not reveal any new signals from prior studies, and there were no BMI category-related associations with AE reporting. The analysis did reveal that tolerability may differ among specific BMI classes, since more discontinuations occurred with semaglutide among lower BMI classes. Potential contributors may include a possibility of higher drug exposure in lower BMI classes, although other explanations, including differences in motivation and cultural mores regarding body size, cannot be excluded.

Is the weight loss in SELECT less than expected based on prior studies with the drug? In STEP 1, a large phase 3 study of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg in individuals without diabetes but with BMI >30 kg m − 2 or 27 kg m − 2 with at least one obesity-related comorbidity, the mean weight loss was −14.9% at week 68, compared with −2.4% with placebo 14 . Several reasons may explain the observation that the mean treatment difference was −12.5% in STEP 1 and −8.7% in SELECT. First, SELECT was designed as a CV outcomes trial and not a weight-loss trial, and weight loss was only a supportive secondary endpoint in the trial design. Patients in STEP 1 were desirous of weight loss as a reason for study participation and received structured lifestyle intervention (which included a −500 kcal per day diet with 150 min per week of physical activity). In the SELECT trial, patients did not enroll for the specific purpose of weight loss and received standard of care covering management of CV risk factors, including medical treatment and healthy lifestyle counseling, but without a specific focus on weight loss. Second, the respective study populations were quite different, with STEP 1 including a younger, healthier population with more women (73.1% of the semaglutide arm in STEP 1 versus 27.7% in SELECT) and higher mean BMI (37.8 kg m − 2 versus 33.3 kg m − 2 , respectively) 14 , 21 . Third, major differences existed between the respective trial protocols. Patients in the semaglutide treatment arm of STEP 1 were more likely to be exposed to the medication at the full dose of 2.4 mg than those in SELECT. In SELECT, investigators were allowed to slow, decrease or pause treatment. By 104 weeks, approximately 77% of SELECT patients on dose were receiving the target semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly dose, which is lower than the corresponding proportion of patients in STEP 1 (89.6% were receiving the target dose at week 68) 14 , 21 . Indeed, in our first on-treatment analysis at week 208, weight loss was greater (−11.7% for semaglutide) compared with the in-trial analysis (−10.2% for semaglutide). Taken together, all these issues make less weight loss an expected finding in SELECT, compared with STEP 1.

The SELECT study has some limitations. First, SELECT was not a primary prevention trial, and the data should not be extrapolated to all individuals with overweight and obesity to prevent major adverse CV events. Although the data set is rich in numbers and diversity, it does not have the numbers of individuals in racial subgroups that may have revealed potential differential effects. SELECT also did not include individuals who have excess abnormal body fat but a BMI <27 kg m − 2 . Not all individuals with increased CV risk have BMI ≥27 kg m − 2 . Thus, the study did not include Asian patients who qualify for treatment with obesity medications at lower BMI and WC cutoff points according to guidelines in their countries 29 . We observed that Asian patients were less likely to be in the higher BMI categories of SELECT and that the population of those with BMI <30 kg m − 2 had a higher percentage of Asian race. Asian individuals would probably benefit from weight loss and medication approaches undertaken at lower BMI levels in the secondary prevention of CVD. Future studies should evaluate CV risk reduction in Asian individuals with high CV risk and BMI <27 kg m − 2 . Another limitation is the lack of information on body composition, beyond the anthropometric measures we used. It would be meaningful to have quantitation of fat mass, lean mass and muscle mass, especially given the wide range of body size in the SELECT population.

An interesting observation from this SELECT weight loss data is that when BMI is ≤30 kg m − 2 , weight loss on a percentage basis is less than that observed across higher classes of BMI severity. Furthermore, as BMI exceeds 30 kg m − 2 , weight loss amounts are more similar for class I, II and III obesity. This was also observed in Look AHEAD, a lifestyle intervention study for weight loss 30 . The proportion (percentage) of weight loss seems to be less, on average, in the BMI <30 kg m − 2 category relative to higher BMI categories, despite their receiving of the same treatment and even potentially higher exposure to the drug for weight loss 30 . Weight loss cannot continue indefinitely. There is a plateau of weight that occurs after weight loss with all treatments for weight management. This plateau has been termed the ‘set point’ or ‘settling point’, a body weight that is in harmony with the genetic and environmental determinants of body weight and adiposity 31 . Perhaps persons with BMI <30 kg m − 2 are closer to their settling point and have less weight to lose to reach it. Furthermore, the cardiometabolic benefits of weight loss are driven by reduction in the abnormal ectopic and visceral depots of fat, not by reduction of subcutaneous fat stores in the hips and thighs. The phenotype of cardiometabolic disease but lower BMI (<30 kg m − 2 ) may be one where reduction of excess abnormal and dysfunctional body fat does not require as much body mass reduction to achieve health improvement. We suspect this may be the case and suggest further studies to explore this aspect of weight-loss physiology.

In conclusion, this analysis of the SELECT study supports the broad use of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg as an aid to CV event reduction in individuals with overweight or obesity without diabetes but with preexisting CVD. Semaglutide 2.4 mg safely and effectively produced clinically significant weight loss in all subgroups based on age, sex, race, glycemia, renal function and anthropometric categories. Furthermore, the weight loss was sustained over 4 years during the trial.

Trial design and participants

The current work complies with all relevant ethical regulations and reports a prespecified analysis of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SELECT trial ( NCT03574597 ), details of which have been reported in papers describing study design and rationale 32 , baseline characteristics 24 and the primary outcome 21 . SELECT evaluated once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiac events (a composite endpoint comprising CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke) in individuals with established CVD and overweight or obesity, without diabetes. The protocol for SELECT was approved by national and institutional regulatory and ethical authorities in each participating country. All patients provided written informed consent before beginning any trial-specific activity. Eligible patients were aged ≥45 years, with a BMI of ≥27 kg m − 2 and established CVD defined as at least one of the following: prior myocardial infarction, prior ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, or symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found elsewhere 32 .

Human participants research

The trial protocol was designed by the trial sponsor, Novo Nordisk, and the academic Steering Committee. A global expert panel of physician leaders in participating countries advised on regional operational issues. National and institutional regulatory and ethical authorities approved the protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Study intervention and patient management

Patients were randomly assigned in a double-blind manner and 1:1 ratio to receive once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo. The starting dose was 0.24 mg once weekly, with dose increases every 4 weeks (to doses of 0.5, 1.0, 1.7 and 2.4 mg per week) until the target dose of 2.4 mg was reached after 16 weeks. Patients who were unable to tolerate dose escalation due to AEs could be managed by extension of dose-escalation intervals, treatment pauses or maintenance at doses below the 2.4 mg per week target dose. Investigators were allowed to reduce the dose of study product if tolerability issues arose. Investigators were provided with guidelines for, and encouraged to follow, evidence-based recommendations for medical treatment and lifestyle counseling to optimize management of underlying CVD as part of the standard of care. The lifestyle counseling was not targeted at weight loss. Additional intervention descriptions are available 32 .

Sex, race, body weight, height and WC measurements

Sex and race were self-reported. Body weight was measured without shoes and only wearing light clothing; it was measured on a digital scale and recorded in kilograms or pounds (one decimal with a precision of 0.1 kg or lb), with preference for using the same scale throughout the trial. The scale was calibrated yearly as a minimum unless the manufacturer certified that calibration of the weight scales was valid for the lifetime of the scale. Height was measured without shoes in centimeters or inches (one decimal with a precision of 0.1 cm or inches). At screening, BMI was calculated by the electronic case report form. WC was defined as the abdominal circumference located midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest. Measures were obtained in a standing position with a nonstretchable measuring tape and to the nearest centimeter or inch. The patient was asked to breathe normally. The tape touched the skin but did not compress soft tissue, and twists in the tape were avoided.

The following endpoints relevant to this paper were assessed at randomization (week 0) to years 2, 3 and 4: change in body weight (%); proportion achieving weight loss ≥5%, ≥10%, ≥15% and ≥20%; change in WC (cm); and percentage change in WHtR (cm cm −1 ). Improvement in BMI category (defined as being in a lower BMI class) was assessed at week 104 compared with baseline according to BMI classes: healthy (BMI <25 kg m − 2 ), overweight (25 to <30 kg m − 2 ), class I obesity (30 to <35 kg m − 2 ), class II obesity (35 to <40 kg m − 2 ) and class III obesity (≥40 kg m − 2 ). The proportions of individuals with BMI <35 or ≥35 kg m − 2 who achieved sex- and race-specific cutoff points for WC (indicating increased metabolic risk) were evaluated at week 104. The WC cutoff points were as follows: Asian women <80 cm, non-Asian women <88 cm, Asian men <88 cm and non-Asian men <102 cm.

Overall, 97.1% of the semaglutide group and 96.8% of the placebo group completed the trial. During the study, 30.6% of those assigned to semaglutide did not complete drug treatment, compared with 27.0% for placebo.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses for the in-trial period were based on the intention-to-treat principle and included all randomized patients irrespective of adherence to semaglutide or placebo or changes to background medications. Continuous endpoints were analyzed using an analysis of covariance model with treatment as a fixed factor and baseline value of the endpoint as a covariate. Missing data at the landmark visit, for example, week 104, were imputed using a multiple imputation model and done separately for each treatment arm and included baseline value as a covariate and fit to patients having an observed data point (irrespective of adherence to randomized treatment) at week 104. The fit model is used to impute values for all patients with missing data at week 104 to create 500 complete data sets. Rubin’s rules were used to combine the results. Estimated means are provided with s.e.m., and estimated treatment differences are provided with 95% CI. Binary endpoints were analyzed using logistic regression with treatment and baseline value as a covariate, where missing data were imputed by first using multiple imputation as described above and then categorizing the imputed data according to the endpoint, for example, body weight percentage change at week 104 of <0%. Subgroup analyses for continuous and binary endpoints also included the subgroup and interaction between treatment and subgroup as fixed factors. Because some patients in both arms continued to be followed but were off treatment, we also analyzed weight loss by first on-treatment group (observation period until first time being off treatment for >35 days) to assess a more realistic picture of weight loss in those adhering to treatment. CIs were not adjusted for multiplicity and should therefore not be used to infer definitive treatment effects. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 TS1M5 (SAS Institute).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.