Edgar Allan Poe Research Paper Topics

This page provides students with a rich tapestry of Edgar Allan Poe research paper topics . From the haunting beauty of his poetry to the chilling narratives of his short stories, Poe’s works present a myriad of research opportunities. This comprehensive guide not only delves into a categorized list of Edgar Allan Poe research paper topics but also offers insights into choosing the perfect Poe topic and crafting an impeccable research paper. Additionally, iResearchNet’s unparalleled writing services are showcased, promising meticulous research and tailored writing solutions. Dive deep into the Gothic allure of Poe, and embark on an academic journey with iResearchNet’s expert guidance.

Edgar Allan Poe’s enigmatic style and dark themes have continuously intrigued scholars and avid readers alike for generations. For those seeking to delve deep into the recesses of Poe’s mind, here is a comprehensive list of Edgar Allan Poe research paper topics spanning across various facets of his work:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, 1. poe’s poetry.

- An analysis of the rhythmic patterns in The Raven .

- The exploration of love and loss in Annabel Lee .

- Ulalume – A journey through grief and remembrance.

- The dark romanticism of A Dream Within a Dream .

- Symbolism in The Bells .

- The personification of death in The Conqueror Worm .

- Navigating the landscapes of Eldorado .

- Themes of sorrow and yearning in Lenore .

- Imagery and melancholy in The Sleeper .

- To Helen and the ideals of beauty.

2. Tales of the Macabre

- Psychological terror in The Tell-Tale Heart .

- The thin line between sanity and insanity in The Black Cat .

- The descent into madness in The Cask of Amontillado .

- Death and disease in The Masque of the Red Death .

- Exploration of guilt in William Wilson .

- The Fall of the House of Usher and the Gothic tradition.

- The pursuit of the unknown in The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar .

- The torment of the soul in Ligeia .

- Themes of revenge in Hop-Frog .

- The intricate narrative of The Pit and the Pendulum .

3. Detective Fiction

- The Murders in the Rue Morgue and the birth of detective fiction.

- The analytical prowess of C. Auguste Dupin.

- The detective’s role in The Mystery of Marie Rogêt .

- Deductive reasoning in The Purloined Letter .

- Poe’s influence on the modern detective genre.

- Examination of crime in Poe’s detective tales.

- The development of sidekicks in detective fiction.

- The detective’s moral compass in Poe’s works.

- Female characters in Poe’s detective stories.

- The evolution of clues and red herrings in Poe’s mysteries.

4. Poe and the Supernatural

- Exploration of the afterlife in Morella .

- Ghosts and hauntings in Poe’s tales.

- The dichotomy of life and death in Berenice .

- The metaphysical in Silence – A Fable .

- Exploration of the soul in The Oval Portrait .

- Visions and prophecies in Poe’s works.

- The exploration of otherworldly realms.

- Portrayal of apparitions and spirits.

- The supernatural as a reflection of human psyche.

- Dreams and omens in Poe’s tales.

5. Poe’s Personal Life and Works

- The influence of Poe’s turbulent love life on his poetry.

- Tragedies of Poe: The deaths that shaped his tales.

- Poe’s relationship with alcohol and its reflection in his work.

- The financial struggles of Poe and their impact on his writings.

- Poe’s tumultuous relationship with the literary community.

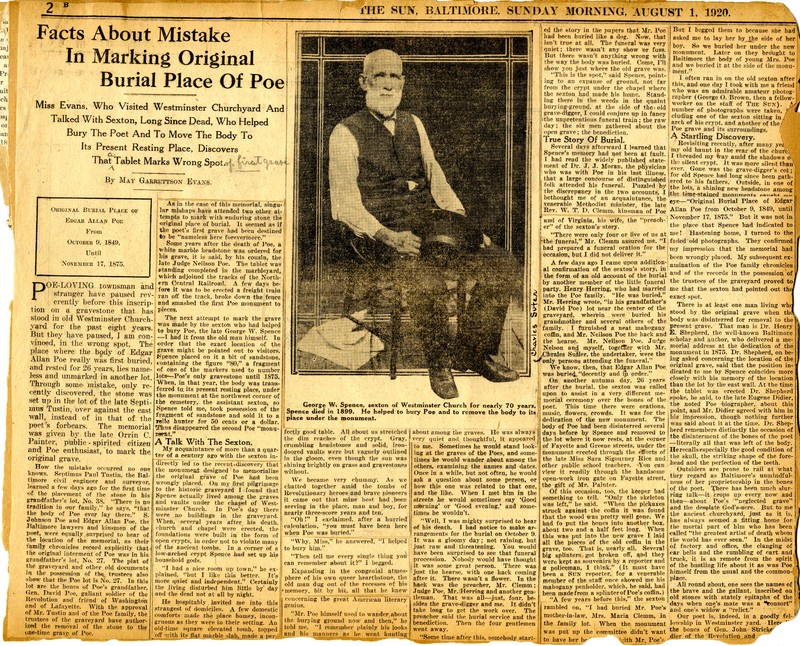

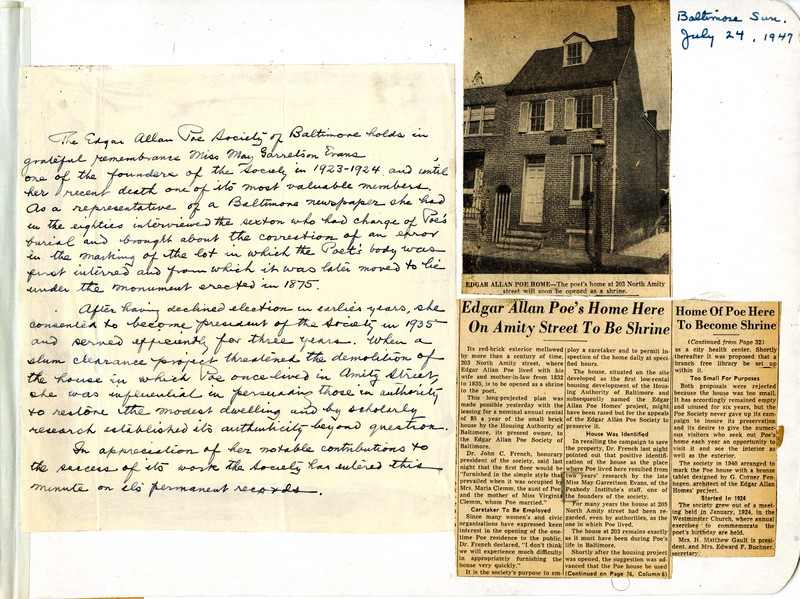

- The mystery of Poe’s death: Theories and narratives.

- Poe’s years in Baltimore and their influence.

- Poe and his foster parents: A complicated bond.

- The influence of Poe’s academic life on his tales.

- Poe’s critiques and their influence on American literature.

6. Poe’s Literary Techniques

- Poe’s use of unreliable narrators.

- The symbolism of the Gothic in Poe’s works.

- The mastery of first-person narrative in Poe’s stories.

- Poe’s pioneering use of psychological horror.

- The recurring motif of the ‘eye’ in Poe’s tales.

- Exploration of sound, from the beating heart to the ominous raven.

- The role of nature in setting the mood in Poe’s works.

- The juxtaposition of beauty and decay in Poe’s prose.

- Poe’s portrayal of women: Idealization and objectification.

- Themes of confinement and entrapment in Poe’s narratives.

7. Poe’s Influence on Modern Literature

- Poe’s impact on 20th-century horror writers.

- The continuation of C. Auguste Dupin in Sherlock Holmes.

- Poe’s influence on contemporary gothic fiction.

- Adaptations of Poe in cinema and theater.

- Modern reimaginings of The Tell-Tale Heart .

- The legacy of The Raven in modern pop culture and more.

- The reinterpretation of Poe’s themes in graphic novels.

- Poe’s legacy in the genre of psychological thrillers.

- How contemporary poets have built upon Annabel Lee .

- The Fall of the House of Usher in modern architectural narratives.

Poe’s Exploration of the Human Psyche

- Exploration of obsession in tales like The Tell-Tale Heart .

- Madness and sanity: The blurred lines in Poe’s narratives.

- Delving into paranoia in The Black Cat .

- Love, loss, and mourning in Poe’s poetic and prose works.

- The subconscious fears in The Premature Burial .

- The human psyche’s struggle with mortality.

- Guilt, conscience, and human nature in Poe’s writings.

- The role of memory in stories like Eleonora .

- The fine line between reality and illusion in Poe’s tales.

- Analyzing self-identity and duality in works like William Wilson .

9. Poe and the Victorian Era

- The portrayal of Victorian society in Poe’s works.

- Social conventions and restraints in Poe’s narratives.

- The influence of the Victorian Gothic on Poe’s tales.

- Victorian views on mortality and their reflections in Poe’s stories.

- The role of women in Poe’s Victorian narratives.

- Poe’s criticism of Victorian moral hypocrisy.

- Poe’s interaction with other Victorian writers.

- The role of science and reason in Poe’s Victorian tales.

- The Victorians’ fascination with the macabre and the supernatural.

- Poe’s view on Victorian advancements and industrialization.

10. Analysis of Selected Works

- A deep dive into The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym .

- The many layers of The Descent into the Maelstrom .

- Isolation and despair in The Island of the Fay .

- The metaphysical quandaries of Eureka: A Prose Poem .

- Unraveling Tamerlane : Poe’s early hints at genius.

- Delving into the drama of Politian .

- Love and loss: An analysis of Bridal Ballad .

- The journey of self-discovery in Al Aaraaf .

- Dissecting the mysteries of MS. Found in a Bottle .

- The symbolism and depth of The Man of the Crowd .

Delving into Edgar Allan Poe’s vast realm of literary contributions is akin to embarking on a journey through layers of the human psyche, societal reflections, and transcendent themes. His works, suffused with intricate symbolism and profound emotion, continue to resonate powerfully with readers across the globe, even after centuries. These Edgar Allan Poe research paper topics serve as a window, offering a glimpse into the multifaceted world of Poe, where every narrative, be it prose or poetry, reveals a new dimension of understanding. By exploring these subjects, students not only immerse themselves in the richness of Poe’s genius but also engage in critical thinking, analytical assessments, and a deeper appreciation of literary artistry. As one ventures deeper into his narratives and poems, it becomes clear why Poe stands as an immortal pillar in the pantheon of literary greats.

Edgar Allan Poe and the Range of Research Paper Topics

Edgar Allan Poe, a name that evokes a mosaic of emotions – from eerie suspense to profound melancholy. Often hailed as the master of the macabre, Poe’s contributions to American literature span much more than just tales of horror and the uncanny. His works are a rich tapestry woven with intricate themes, unparalleled symbolism, and a deep understanding of the human psyche. This literary genius’s stories and poems have continually fascinated scholars, readers, and writers alike, offering a plethora of Edgar Allan Poe research paper topics for literature enthusiasts to dive into.

To understand the vast range of research avenues in Poe’s works, one must first grasp the breadth of his literary portfolio. Although primarily recognized for his gothic tales, Poe was also an astute critic, an innovative poet, and a pioneer of the short story genre. He adeptly merged both European romanticism and American originality, resulting in a unique literary style that still stands unmatched.

The Enigmatic Poe

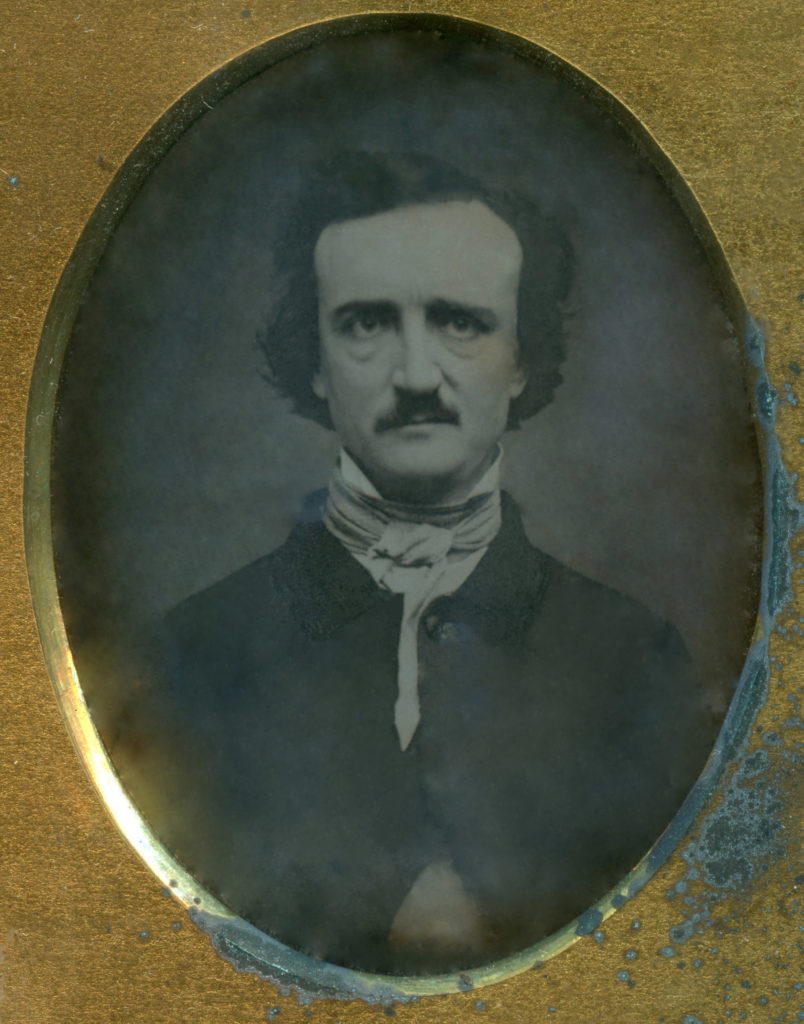

One of the enduring fascinations with Poe is his own life – as mysterious and tragic as some of his tales. Orphaned at a young age, battling personal demons, and facing numerous adversities, Poe’s tumultuous life deeply influenced his writings. Exploring the parallels between his personal experiences and his fictional worlds is a research area that continues to captivate scholars. His enigmatic death, still a mystery, is a testament to the lingering intrigue surrounding his life.

Poe’s Exploration of the Human Psyche

Much ahead of his time, Poe delved deep into the complexities of the human mind. Stories like The Tell-Tale Heart and The Black Cat are not just tales of horror but profound psychological studies of guilt, paranoia, and mental descent. Analyzing the psychological undertones in his works provides a multi-dimensional approach to his stories, making them relevant even in modern psychoanalytical discussions.

Symbolism and the Supernatural

Poe’s tales are replete with symbols. Be it the hauntingly sentient House of Usher or the relentless Raven, Poe used symbols to enhance the atmospheric dread of his stories and to dive deep into abstract concepts. This prolific use of symbolism offers researchers a rich field to dissect, interpret, and reinterpret.

Poe and Science Fiction

Often overshadowed by his gothic tales, Poe’s foray into science fiction, exemplified by stories like The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall and Mellonta Tauta , is an area ripe for exploration. Here, he blends his narrative genius with speculative visions of science, creating stories that can be viewed as precursors to the modern science fiction genre.

Poetic Techniques and Innovations

Poe was not just a storyteller; he was a poet par excellence. His poems, such as Annabel Lee , The Bells , and Ulalume , are studies in rhythm, sound, and emotion. They oscillate between the melancholic and the macabre, making them enduring pieces of poetic art. Researching his poetic techniques, innovations, and influences can be a fulfilling journey for anyone interested in poetic forms and structures.

Literary Criticism and Theories

As a critic, Poe had strong opinions on art, literature, and the role of the critic. His reviews, essays, and theories on writing are illuminating, offering a peek into the mind of a literary genius. Exploring Poe’s literary criticism can provide insights into 19th-century literary standards, Poe’s influences, and his expectations from literature and fellow writers.

Poe’s cultural impact is another intriguing facet to consider. His influence is not limited to American literature but spans globally, impacting various art forms. From cinema adaptations to his influence on subsequent writers and even musicians, Poe’s legacy is extensive and multifaceted.

The very nature of Poe’s work – its depth, diversity, and enduring relevance – makes it a goldmine for research. Whether one is analyzing the structural aspects of his poems, dissecting the themes of his tales, or tracing the influences of his personal life on his works, the opportunities for scholarly exploration are virtually limitless.

In conclusion, Edgar Allan Poe’s literary contributions are not mere tales to be read and forgotten. They are intricate webs of narrative brilliance, emotional depth, and symbolic complexity. For literature students and scholars, every Poe story or poem presents a unique research challenge, beckoning them to delve deeper, question more, and embark on an endless journey of literary discovery.

How to Choose Edgar Allan Poe Research Paper Topics

Selecting a topic for a research paper on Edgar Allan Poe is like being a kid in a candy store. The options are vast, intriguing, and tempting. But with so many directions to pursue, how does one choose a topic that’s not only engaging but also academically rewarding? Let’s embark on this journey of selection with some structured steps and key considerations.

- Identify Your Interest: Begin by determining which of Poe’s works or themes particularly captivate you. Is it the eerie atmosphere of “The Fall of the House of Usher” or the relentless psychological torment in “The Tell-Tale Heart”? Your genuine interest will make the research process more enjoyable and your paper more passionate.

- Consider the Scope: While it’s tempting to pick a broad topic like “Poe’s contribution to American literature,” it might be too vast for a detailed study. Instead, opt for more narrow focuses, such as “Poe’s influence on the detective fiction genre.”

- Historical Context: Poe’s writings did not emerge in a vacuum. Understanding the socio-political and cultural context of his time can offer a fresh lens to view his works. Topics like “Poe and the American Romantic Movement” or “Societal Reflections in Poe’s Gothic Tales” can be compelling.

- Analytical versus Argumentative: Determine the nature of your paper. An analytical paper on “The Symbolism in The Raven ” differs from an argumentative paper asserting “Poe’s Representation of Women as Symbols of Death and Decay.”

- Relevance to Modern Times: Exploring how Poe’s themes resonate with contemporary issues can be enlightening. For instance, examining the portrayal of mental health in his stories in light of current psychological understanding can be a rich research area.

- Cross-disciplinary Approaches: Don’t restrict yourself to purely literary angles. Poe’s works can be explored from psychological, sociological, or even philosophical perspectives. A topic like “Freudian Analysis of Poe’s Protagonists” can be intriguing.

- Comparative Studies: Comparing Poe with other contemporaries or authors from different eras can shed light on literary evolutions and contrasts. Topics such as “Poe and Hawthorne: A Study in Dark Romanticism” can offer dual insights.

- Unexplored Angles: While much has been written about Poe’s famous works, venturing into his lesser-known stories, poems, or essays can be rewarding. Delving deep into these uncharted territories can present fresh perspectives.

- Consider Available Resources: Ensure that there are enough primary and secondary sources available for your chosen topic. While original interpretations are valuable, building upon or contrasting with existing scholarship enriches your research.

- Seek Feedback: Before finalizing your topic, discuss it with peers, professors, or literature enthusiasts. Fresh eyes can offer new perspectives, refine your focus, or even present angles you hadn’t considered.

In conclusion, choosing a research paper topic on Edgar Allan Poe requires a blend of personal interest, academic viability, and originality. Remember that the goal is not just to explore the enigmatic world Poe created but to add a unique voice to the ongoing discourse about his works. Armed with passion and a structured approach, you’re set to select a topic that will not only enlighten readers but also deepen your appreciation of Poe’s literary genius.

How to Write an Edgar Allan Poe Research Paper

Crafting a research paper on Edgar Allan Poe is a journey into the heart of 19th-century American Gothic literature. Known as the master of macabre, Poe’s works are rich in symbolism, psychological insights, and intricate narratives. To bring justice to such depth in a research paper, a systematic approach is necessary. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you navigate the hauntingly beautiful world of Poe and create a compelling paper.

- Deep Reading: Before everything else, immerse yourself in the selected work(s) of Poe. Read it multiple times, noting the nuances, literary techniques, and recurrent themes. This isn’t just casual reading; it’s about diving deep into the text.

- Thesis Statement: A research paper isn’t merely a summary. It needs a central argument or perspective. Craft a clear, concise thesis statement that conveys the essence of your paper. For instance, “Through The Fall of the House of Usher , Poe explores the thin boundary between sanity and madness.”

- Outline Your Thoughts: Structure is vital when delving into Poe’s intricate narratives. Create an outline with clear sections, including introduction, literature review, methodology (if applicable), main arguments, counterarguments, and conclusion.

- Historical and Biographical Context: To understand Poe, it’s imperative to understand his life and times. Infuse your paper with insights about Poe’s tumultuous life, his contemporaries, and the broader socio-cultural milieu of his era.

- Literary Analysis: Delve into the literary aspects of the work. Explore Poe’s use of symbolism, metaphor, allegory, and other devices. Analyze his narrative structures, use of unreliable narrators, or the rhythm and meter in his poems.

- Interdisciplinary Insights: Don’t limit your analysis to a purely literary perspective. Draw insights from psychology (especially when discussing tales like The Tell-Tale Heart ), philosophy, or even the sciences.

- Engage with Scholars: Your interpretations should be in dialogue with established Poe scholars. Reference critical essays, research papers, and academic discourses that align or contradict your arguments. This lends credibility to your work.

- Address Counterarguments: A well-rounded research paper acknowledges differing views. If there are prominent interpretations that contradict your thesis, address them. It shows academic integrity and a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

- Effective Conclusion: Wrap up by reiterating your thesis and summarizing your main arguments. Also, hint at the broader implications of your findings or suggest areas for future research.

- Proofreading and Citations: After pouring so much effort into your analysis, don’t let grammatical errors or incorrect citations mar your paper. Review your work multiple times, use citation tools, and adhere to the desired formatting style (MLA, APA, etc.).

In summary, writing a research paper on Edgar Allan Poe is an intricate dance between analysis and appreciation. While the process requires a meticulous approach, it’s also an opportunity to immerse oneself in the rich tapestry of Poe’s imagination. Remember, it’s not just about producing an academic paper, but also about connecting with one of the literary world’s most enigmatic figures. Embrace the challenge, and let Poe’s haunting allure guide your pen.

Custom Research Paper Writing Services

Navigating the mysterious and captivating world of Edgar Allan Poe is no simple endeavor. The depth, symbolism, and emotional charge in his writings require a unique blend of understanding, analysis, and passion. For students tasked with crafting a research paper on Poe, the weight of doing justice to such a literary giant can feel overwhelming. This is where iResearchNet steps in, bridging the gap between student ambition and academic excellence. Here’s what sets our services apart when it comes to delivering a custom Edgar Allan Poe research paper.

- Expert Degree-Holding Writers: Our team boasts professionals who have not only mastered the craft of academic writing but are also well-versed in the world of Edgar Allan Poe. Their academic background and passion for literature ensure that your paper is in capable hands.

- Custom Written Works: We do not believe in one-size-fits-all. Every Edgar Allan Poe research paper crafted by iResearchNet is tailored to individual requirements, ensuring uniqueness and relevance.

- In-depth Research: Poe’s writings demand an intricate level of analysis. Our research dives deep into his texts, critical interpretations, historical contexts, and the nuances that make his work stand out.

- Custom Formatting: Whether your institution requires APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, or Harvard formatting, our writers are adept at creating papers that adhere strictly to these guidelines.

- Top Quality: Quality is our hallmark. From structuring the paper to ensuring coherent arguments and impeccable language, we ensure that your paper shines in all aspects.

- Customized Solutions: Whether you need insights into The Raven ‘s melancholic undertones or a deep dive into the symbolism in The Tell-Tale Heart , our writers provide solutions tailored to your specific needs.

- Flexible Pricing: We understand the budget constraints students often face. Our pricing models are designed to offer premium quality services at rates that don’t break the bank.

- Short Deadlines: Time crunch? No worries. Our efficient team can deliver top-notch research papers even on tight deadlines, ensuring you never miss a submission date.

- Timely Delivery: We respect deadlines and understand their importance in the academic world. With iResearchNet, timely delivery is a guarantee.

- 24/7 Support: Whether you have a query, need an update, or require last-minute changes, our support team is available round the clock to assist you.

- Absolute Privacy: Your trust is paramount. All personal and academic information shared with us remains confidential, always.

- Easy Order Tracking: With our seamless tracking system, you can monitor the progress of your paper, ensuring transparency throughout the process.

- Money-Back Guarantee: Our goal is your satisfaction. If, for any reason, the paper doesn’t meet your expectations, our money-back guarantee ensures you’re covered.

In conclusion, writing about Edgar Allan Poe is as challenging as it is rewarding. With iResearchNet’s comprehensive writing services, you not only get a paper that matches academic standards but also captures the essence of Poe’s genius. Entrust us with your academic journey through the hauntingly beautiful world of Poe, and let us craft a paper that resonates with both intellect and emotion.

Embrace the Dark Allure of Poe with iResearchNet

Dive into the shadowy realms of Edgar Allan Poe’s universe, a world filled with intricate tales of love, despair, horror, and the supernatural. As you traverse this intricate literary landscape, let the expertise of iResearchNet guide and support you. While the gothic beauty of Poe’s works is undeniably captivating, the task of analyzing and interpreting them can be daunting. Why wander alone in these literary labyrinths when you can have a seasoned guide by your side?

By choosing iResearchNet, you’re not just selecting a service; you’re opting for a partnership. A partnership that understands the nuances of Poe’s writings, recognizes the depths of his narratives, and captures the essence of his stories in every line written. Each tale, from the heart-wrenching Annabel Lee to the haunting Masque of the Red Death , demands more than just a surface-level reading. It calls for a deep dive into the very soul of the narrative, a task that our expert writers are perfectly poised to undertake.

But the allure of iResearchNet goes beyond mere expertise. It’s about the commitment to excellence, the dedication to understanding your specific needs, and the relentless pursuit of academic brilliance. We’re not just offering a service; we’re extending an invitation. An invitation to embark on an unforgettable journey through Poe’s dark yet enchanting world, with the assurance that you have the best in the business by your side.

So, are you ready to embrace the macabre, the romantic, and the profound tales of one of literature’s most iconic figures? Trust in the expertise of iResearchNet, and let us illuminate the path. Dive deep, explore fearlessly, and let the dark allure of Poe’s world captivate your academic endeavors. Step forward with confidence, and let’s begin this enthralling journey together!

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

100 Edgar Allan Poe Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Edgar Allan Poe is one of the most influential and celebrated writers in American literature. Known for his dark and mysterious themes, Poe's work continues to captivate readers and inspire new generations of writers. If you're a student tasked with writing an essay on Edgar Allan Poe, you may be struggling to come up with a compelling topic. To help you get started, here are 100 Edgar Allan Poe essay topic ideas and examples:

- Analyze the use of symbolism in Poe's "The Raven."

- Discuss the theme of madness in Poe's short stories.

- Explore the role of women in Poe's works.

- Compare and contrast the different narrators in Poe's stories.

- Investigate the influence of Poe's personal life on his writing.

- Examine the use of Gothic elements in Poe's poems.

- Discuss the significance of death in Poe's poetry.

- Analyze the theme of isolation in Poe's works.

- Explore the role of the supernatural in Poe's stories.

- Compare Poe's poetry to his short stories.

- Investigate the use of irony in Poe's writing.

- Discuss the theme of revenge in Poe's works.

- Analyze the role of fear in Poe's stories.

- Explore the theme of love and loss in Poe's poetry.

- Discuss the influence of Edgar Allan Poe on modern horror literature.

- Analyze the use of setting in Poe's stories.

- Explore the theme of guilt in Poe's works.

- Discuss the significance of the title character in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Analyze the use of suspense in Poe's writing.

- Explore the theme of obsession in Poe's works.

- Discuss the role of the narrator in Poe's stories.

- Analyze the theme of duality in Poe's works.

- Explore the significance of the title character in "The Black Cat."

- Discuss the use of unreliable narrators in Poe's stories.

- Analyze the theme of addiction in Poe's works.

- Explore the role of death in Poe's poetry.

- Discuss the theme of betrayal in Poe's stories.

- Analyze the use of repetition in Poe's writing.

- Explore the theme of imprisonment in Poe's works.

- Discuss the significance of the title character in "Ligeia."

- Analyze the use of foreshadowing in Poe's stories.

- Explore the theme of redemption in Poe's works.

- Discuss the role of the supernatural in Poe's poetry.

- Analyze the theme of decay in Poe's works.

- Explore the significance of the title character in "Lenore."

- Discuss the use of unreliable memory in Poe's stories.

- Analyze the theme of madness in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Explore the role of guilt in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Discuss the significance of the setting in "The Fall of the House of Usher."

- Analyze the theme of obsession in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Explore the role of revenge in "The Cask of Amontillado."

- Discuss the use of irony in "The Masque of the Red Death."

- Analyze the theme of addiction in "The Black Cat."

- Explore the significance of the title character in "The Raven."

- Discuss the use of symbolism in "The Pit and the Pendulum."

- Analyze the theme of duality in "William Wilson."

- Explore the role of fear in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Discuss the significance of the setting in "The Murders in the Rue Morgue."

- Analyze the theme of isolation in "The Fall of the House of Usher."

- Explore the role of the supernatural in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Discuss the use of unreliable narration in "The Black Cat."

- Analyze the theme of love and loss in "Annabel Lee."

- Explore the significance of the title character in "The Tell-Tale Heart."

- Discuss the role of the narrator in "The Fall of the House of Usher."

- Analyze the theme of revenge in "The Cask of Amontillado."

- Explore the use of repetition in "The Raven."

- Analyze the theme of madness in "The Black Cat."

- Discuss the use of symbolism in "The Masque of the Red Death."

- Analyze the theme of addiction in "The Pit and the Pendulum."

- Explore the significance of the title character in "The Fall of the House of Usher."

- Discuss the role of fear in

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Poe, edgar allan.

- Thomas Wright

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.612

- Published online: 26 September 2017

At the beginning of the twenty-first century , Edgar Allan Poe was more popular than ever. The Raven and a number of his Gothic and detective tales were among the most famous writings in the English language, and they were often some of the first works of literature that young adults read. They had also entered the popular imagination—football teams and beers were named after them, and they had inspired episodes of the animated television show The Simpsons and a number of rock songs. Poe also continued to exercise a profound influence over writers and artists. Two of the most popular authors of the second half of the twentieth century , Stephen King and Isaac Asimov , acknowledged Poe as an important precursor. Countless novels published at the end of the twentieth century , such as Peter Ackroyd 's The Plato Papers: A Prophesy ( 1999 ) and Mark Z. Danielewski 's House of Leaves ( 2000 ), also bear definite traces of his influence. The Argentinean author Jorge Luis Borges , whose own works are greatly indebted to Poe, once called him the unacknowledged father of twentieth-century literature, and Poe's influence shows no signs of diminishing. Despite his enormous popularity and influence, Poe's canonical status is still challenged by certain commentators. Harold Bloom , for instance, regards Poe's writings as vulgar and stylistically flawed. Bloom follows in a long line of Poe detractors, many of whom have been amazed by the fact that what T. S. Eliot called his “puerile” and “haphazard” productions could have influenced “great” writers such as the French poets Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé .

Poe criticism was, however, far more favorable (and far more plentiful) over the last half of the twentieth century than previously. Poe is indeed something of a boom industry in academia. New Critics, New Historicists, psychoanalysts, and poststructuralists all find his works suggestive. Few of these critics are interested in making aesthetic judgements, however, and those who concern themselves with such things continue to express doubts about Poe's achievement.

As a result, Poe remains something of an enigma. To many he is a formative influence, a genius, and an inspiration; to others he is a shoddy stylist and a charlatan. It would be more reasonable, perhaps, to regard Poe as all of these things and to accept James Russell Lowell 's famous judgment that he was “Three fifths…genius, and two fifths sheer fudge.” Few of Poe's readers are reasonable, however, as he is one of those writers who is either loved or hated.

Poe's Persona

One of the reasons Poe has been far more popular and influential than writers who, according to some, have produced works of greater literary value is that he created, with a little help from others, a fascinating literary persona. That persona was of an author at once bohemian and extremely intellectual. The bohemian aspect was largely the creation of his “friend” Rufus Wilmot Griswold , who in his obituary of Poe described him as a depraved and demonic writer. Poe himself was responsible for the intellectual element: he presented himself to the public in his writings as an erudite and bookish scholar.

Poe's persona captured the imagination of the world; like Byron before him, he became a kind of mythical or archetypal figure. Nineteenth-century poets such as Ernest Dowson and Baudelaire (who prayed to Poe and dressed up as him) regarded Poe as the original bohemian poète maudit (a tradition in which the poet explores extremes of experience and emotional depth) and as the first self-conscious literary artist. As such, he seemed to be a prefiguring type of themselves. This legendary persona may be at odds with Poe's real personality and the actual facts of his biography, but that is beside the point. What matters is that it fascinated and continues to fascinate people.

Poe's legendary personality and life have also provided people with a context in which his writings can be read (and it is worth noting here that an account of Poe's life has traditionally appeared as a preface to anthologies of his works). As is the case with the Irish writer Oscar Wilde , we tend to read Poe's works as expressions of his (real or mythical) character and as dramatizations of his personality. This confers a degree of homogeneity on his writings; although he experimented in a variety of forms and wrote on numberless topics, we think of all of his productions as “Poe performances.”

Early Poetry

Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston on 19 January 1809 , the son of the itinerant actors David Poe Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold , both of whom died when he was still an infant. He was brought up by the Richmond tobacco merchant John Allan , with whom he had a difficult relationship. Educated in London and then, for a brief period, at the University of Virginia, Poe entered the U.S. Army in 1827 . It was always Poe's ambition to be recognized as a great poet, and in 1827 he published his first volume of verse, Tamerlane and Other Poems , under the name “a Bostonian.”

The title poem of the slim collection is a monologue by Tamerlane, the Renaissance Turkish warrior. The other poems are conventional romantic meditations on death, solitude, nature, dreams, and vanished youth in which Poe comes before us, as it were, in the theatrical garb of the romantic poet. The poems display Poe's considerable gift for imitation (which he later used to great effect in his prose parodies) and his habit of half quoting from his favorite authors. They contain countless echoes from romantic poets (especially Lord Byron). It is not, however, so much a question of plagiarism as it is of Poe serving a literary apprenticeship and placing himself within a poetic tradition.

In 1829 Poe published, under his own name, his second verse collection, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems . It contained revised versions of some of the poems that had been published in Tamerlane (Poe was a zealous reviser) and seven new poems. Sonnet—To Science , Poe's famous poem on the antagonistic relationship between science and poetry, opens the book. It is followed by the title poem, Al Aaraaf , which has been variously interpreted as a lament for the demise of the creative imagination in a materialistic world and as an allegorical representation of Poe's aesthetic theories. The poem is characterized by its variety of meter, its heavy baroque effects, and its extreme obscurity. The volume has its lighter moments, however. Fairyland , with its “Dim vales,” “Huge moons,” and yellow albatrosses is one of Poe's first exercises in burlesque and self-parody. It was typical of Poe to include, within the same volume, serious poems and comic pieces that seem to parody those compositions.

In 1831 , wishing to leave the army, Poe got himself expelled from the West Point military academy. In that year he also brought out a third volume of poetry, Poems by Edgar A. Poe . This collection represents a considerable advance on his earlier efforts and contains famous poems such as To Helen and The Doomed City (later called The City in the Sea ). The former, which is perhaps the most beautiful of all Poe's lyrics, is a stately hymn to Helen of Troy, which in its later, revised form, contained the celebrated lines:

Thy Naiad airs have brought me home To the Glory that was Greece, And the grandeur that was Rome.

The Doomed City is a wonderful evocation of a silent city beneath the sea.

Both poems create a haunting atmosphere through the use of alliteration, assonance, measured rhythms, and gentle rhymes; they also contain words with long open vowel sounds such as “loom,” “gloom,” “yore,” and “bore” that were to become a Poe trademark. Because of Poe's fondness for such techniques, it is hardly surprising that his poems have been compared to music. Poe believed that music was the art that most effectively excited, elevated, and intoxicated the soul and thus gave human beings access to the ethereal realm of supernal beauty, a realm in which Poe passionately believed and for which he seems to have pined throughout his life. As Poe aimed to create similar effects with his verse, he attempted to marry poetry and music. This is why the rhythm of his verse is perfectly measured and often incantatory; it is also why he frequently chose words for their sounds rather than for their sense. In To Helen , for example, he writes of “those Nicéan barks of yore,” a rather confused classical allusion but a word that produces wonderfully musical vibrations.

Poe offers us what he called “a suggestive indefiniteness of meaning with a view of bringing about vague and therefore spiritual effects .” Decadent and symbolist poets of the nineteenth century , including Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine , were heavily influenced by Poe's method, and they consciously imitated his “word-music.” They also regarded Poe as their most important precursor because of his theoretical statements about poetry. Indeed, Poe was (and perhaps remains) as famous a critic and theoretician of verse as he was a poet. He is particularly remembered for his powerful denunciation of didactic poetry and for his emphasis on the self-consciousness and deliberateness of the poet's art.

Most of Poe's important theoretical pronouncements were made in the essays and lectures he wrote toward the end of his life. In Poems he wrote a prefatory “Letter to Mr —,” which represents his first theoretical statement about verse. Here he defined poetry as a pleasurable idea set to music. He also argued, with more than a slight nod to the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge , that poetry “is opposed to a work of science by having, for its immediate object, pleasure, not truth; to romance, by having for its object an indefinite instead of a definite pleasure.” At its best, Poe's poetry embodies such ideas by creating vague yet powerful atmospheric effects and by giving the reader intense aesthetic pleasure.

Poe's early poetry received mixed reviews and failed to establish him as either a popular or a critically acclaimed author. Later commentators, such as T. S. Eliot and Walt Whitman , criticized its limited range and extent; they also bemoaned its lack of intellectual and moral content. Others dismissed Poe as a mere verse technician; Emerson famously referred to him as “the jingle man.” Poe's verse was, however, revered by later nineteenth-century poets such as Mallarmé and Dowson, and considering his influence on such Decadent and symbolist writers, he can perhaps be regarded as the most influential American poet of that century after Whitman.

Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque

Numerous connections exist between Poe's early verse and the short stories he started to write for magazines and newspapers around 1830 . (Poe's decision to turn his hand to prose was partly because of the lack of commercial and critical success achieved by his poetry.) In some of his stories Poe included poems; he also returned to forms, such as the dramatic monologue and the dialogue between disembodied spirits, that he had used in poems such as Tamerlane and Al Aaraaf . And yet Poe's tales are clearly distinguished from his early verse, most obviously by their variety of mood, content, and theme. Poe seems to have been liberated as a writer when he turned from romantic verse to the more flexible, capacious, and traditionally heterogeneous genre of the short story. He now had at his disposal a multitude of tones and devices, and in the twenty-five stories that he wrote in the 1830s and that were collected in the anthology Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (2 vols., 1840 ), he exploited these to great effect.

In fact, such is the diversity of the style and mood of Poe's early stories that the division of the contents of Tales into the two categories of grotesque and arabesque seems simplistic and inadequate. Poe's grotesques are comic and burlesque stories that usually involve exaggeration and caricature. In this group we can include the tales Lionizing and The Scythe of Time (earlier called A Predicament ), which are satires of the contemporary literary scene. Another characteristic of Poe's grotesque stories is the introduction of elements of the ludicrous and the absurd. In the tale Loss of Breath , the protagonist literally loses his breath and goes out in search of it. It is a shame that Poe's early grotesques are generally neglected, because not only do they testify to his range and resourcefulness as a writer, but some of them are compelling and funny. The neglect results partly from the fact that, in order to be appreciated, they require extensive knowledge of the literary and political state of antebellum America and partly because they have been overshadowed by his arabesque tales.

Poe's arabesque tales are intricately and elaborately constructed prose poems. The word “arabesque” can also be applied to those stories in which Poe employed Gothic techniques. Gothic literature, which typically aimed to produce effects of mystery and horror, was established in the latter half of the eighteenth century by writers such as the English novelist Anne Radcliffe and the German story writer E. T. A. Hoffmann . By the beginning of the nineteenth century , the Gothic short story had become one of the most popular forms of magazine literature in England and America.

It is generally agreed that Poe's particular contribution to Gothic literature was his use of the genre to explore and describe the psychology of humans under extreme and abnormal conditions. Typically, his characters are at the mercy of powers over which they have no control and which their reason cannot fully comprehend. These powers may take the form of sudden, irrational impulses (“the imp of the perverse” that inspires the protagonist of Berenice to extract the teeth of his buried wife, for example), or as is the case with the eponymous hero of William Wilson , a hereditary disease. Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque contains some of Poe's most famous Gothic productions, including Morella , Ligeia , and Berenice (the stories of the so-called “marriage group,” which concern the deaths of beautiful young women), along with perhaps the most popular of all his tales, The Fall of the House of Usher .

“Usher” is a characteristic arabesque production. It exhibits many of the trappings of Gothic fiction: a decaying mansion located in a gloomy setting, a protagonist (Roderick Usher) who suffers from madness and a peculiar sensitivity of temperament inherited from his ancient family, and a woman (his sister) who is prematurely buried and who rises from her tomb. Yet from Gothic clichés such as these, Poe produced a tale of extraordinary power. Indeed, perhaps only Stephen King in The Shining ( 1977 ) has succeeded in investing a building with such horror and in conveying the impression that it is alive.

Apart from the grotesque and arabesque stories, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque includes other varieties of writing. Hans Phaall has been classed as science fiction, and King Pest is a surreal historical adventure. Several stories contain elements of all of these genres; Metzengerstein , for example, is at once a work of historical fiction, a powerful Gothic tale, and a witty and grotesque parody of the latter genre. The diversity of the contents of the tales, and the variety of theme and style within individual stories, must be seen in the context of the original form in which they appeared. All of the tales were first published in popular newspapers and magazines from 1832 to 1839 . The audience for such publications was extremely heterogeneous, and Poe was clearly trying to appeal to as large a cross-section as possible. We should also remember that, unlike subscribers to weightier publications, the magazine- and newspaper-reading public had a very limited attention span. Readers craved novelty, sensation, and diversity.

Poe was profoundly influenced by the tastes of this public. In a letter to Thomas Willis White , a newspaper editor, he remarked that the public loves “the ludicrous heightened into the grotesque: the fearful colored into the horrible: the witty exaggerated into the burlesque: the singular wrought out into the strange and mystical.” In Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque this is precisely what he gave them. The most obvious characteristic of his stories is their sensationalism: they include accounts of balloon journeys to the moon, premature burials, encounters with the devil, and a number of gruesome deaths.

From the early 1830s Poe planned to gather together his short stories and publish them in book form. In the mid-1830s he unsuccessfully offered for publication a collection of stories under the title Tales of the Folio Club . Poe devised an elaborate plan for the “Folio Club” volume. The tales were to be read out, over the course of a single evening, by various members of a literary club, and each story was to be followed by the critical remarks of the rest of the company. The book was evidently intended as a satire of popular contemporary modes of fiction and criticism; as such it can be compared to the work of Poe's English contemporary, Thomas Love Peacock . The satirical intent is clearly indicated by the names and descriptions of the various club members, which include “Mr Snap, the President, who is a very lank man with a hawk nose.” Many of the figures were based on real people.

When considering Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque , it is important to remember the dramatic nature of its forerunner. Our knowledge of the Folio Club gathering encourages us to read Poe's stories as the compositions of various personae and to regard Poe as author of the authors of the tales. W. H. Auden described Poe's writing as operatic, and Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque does indeed resemble an opera in which Poe's narrators walk on and off the stage. Thus, the narrator of Morella mutters, melodramatically, “Years—years, may pass away, but the memory of that epoch—never!” as he leaves the stage to make way for the narrator of Lionizing . “I am,” the latter remarks to the reader-audience by way of introduction, “that is to say, I was —a great man.”

Poe's gift for impersonating his narrators is remarkable, and like a great dramatist, he seemed to contain multitudes of characters. The comparison with the playwright is appropriate because the world of Poe's writing is a thoroughly theatrical one. In it the laws of “real life” (of psychological accuracy and consistency, for instance) do not apply, and in this context we can recall Poe's famous distinction between “Hamlet the dramatis persona” and “Hamlet the man.” In the Poe universe, bizarre and absurd incidents occur on a regular basis, the dialogue and the settings are distinctly stagy, and everything is hyperbolic. As the above quotations from Morella and Lionizing suggest, it is also a world in which tragedy can be quickly followed by comedy.

And here we might recall that Poe was the son of two itinerant actors. It is particularly interesting to note that Poe's beloved mother, Eliza, was renowned for her ability to play an enormous range of tragic and comic roles, often in the same theatrical season. Her son seems to have inherited this gift as, in his writings, he effortlessly swaps a suit of sables for motley attire. At times, as in The Visionary (later called The Assignation ), which contains elements of tragedy, parody, and self-parody, Poe wore both costumes at the same time. And this in turn may help us understand the appeal of Gothic literature for Poe, because it is a form of writing in which comedy intensifies the horror by setting it in relief. Those who have adapted Poe's tales for the cinema have appreciated the humorous elements of the Gothic, as their films are at once terrifying and hilarious.

Drama and theatricality are in fact everywhere in Poe's writing. As a young poet, he effortlessly mimicked the styles of writers such as Byron; as a reviewer he convincingly adopted the tone of the authoritative critic. Throughout his works he seems to entertain and juggle ideas rather than to offer them as articles of faith, and the idea of literary performance is central to his authorship. Poe is a writer-performer whose productions can be compared to virtuoso literary displays. As readers we are like members of a theater audience who are by turns enthralled, horrified, and dazzled, and when the performance is over we applaud Poe's artistry.

An appreciation of the theatrical nature of Poe's work has important consequences for criticism. If we view Poe's writing as fundamentally dramatic, it becomes impossible to discover Poe's individual voice in the universe of voices that is his work or to analyze it from the point of view of his authorial intentions. It also becomes essential to judge the work's style and content in terms of its dramatic appropriateness: when Poe's writing is weak and verbose, for example, this may be the appropriate style for a particular narrator.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket

The only full-length novel that Poe would write, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket ( 1838 ), was begun on the suggestion of a publisher to whom he had unsuccessfully offered Tales of the Folio Club . Its first two installments appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger , and it came out in book form in 1838 . In choosing to write a sensational sea adventure—the plot includes, among other things, a mutiny, a shipwreck, a famine, and a massacre—Poe once again selected an extremely popular subject and form.

As a realistic chronicle of an utterly fantastic journey, the novel is similar to some of the stories Poe had written in the 1830s, such as MS. Found in a Bottle . Cast in the form of a first-person account of a real sea voyage and including journal entries, “factual” information, and scholarly footnotes, Pym is written with a sharp attention to significant detail that recalls the novels of the eighteenth-century author Daniel Defoe . This attention to detail, which can be found throughout Poe's fiction, confers a degree of verisimilitude on narrations that lack psychological realism. Poe's fictional works are not, in other words, realistic, but they have a reality of their own. Pym is also similar to a Defoe novel in that it is digressive and loosely structured. In contrast to Poe's short stories, it lacks a definite architecture and fails to create a unified impression or effect. Curiously enough, this is precisely what makes it such a hypnotic book. Pym's journey, like that of Karl Rossman in Franz Kafka 's Amerika ( 1927 ), is imbued with a vague sense of horror.

Pym also contains a preface, reminiscent of Defoe, in which the narrator claims that the book is a real account of a voyage although its first installments in the Southern Literary Messenger had appeared under the name of the short-story writer, “Mr Poe.” Few reviewers were taken in by this typical Poe hoax, and the novel was generally reviewed with varying degrees of enthusiasm, as a work of fiction. Until around the 1960s, critics tended to agree with Poe's own dismissive estimation of his “very silly” novel. Since then, however, it has received much better press and has inspired a variety of readings that range from the autobiographical to the allegorical. Like many of Poe's works, it is Pym 's ambiguity and indefiniteness that make it so suggestive. These qualities are perfectly embodied in the novel's famous last line. As the eponymous hero's boat heads toward a cataract, a shrouded human figure suddenly appears, “And the hue of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.” At about the same time Poe also wrote two other works, both unfinished, that can be briefly mentioned here. The Journal of Julius Rodman , a Pym -like account of an expedition across the Rocky Mountains, appeared in Gentleman's Magazine in 1840 . Five years previously the Southern Literary Messenger had published scenes from Politian , a blank verse tragedy set in Renaissance Italy that would later be included in The Raven and Other Poems ( 1845 ).

Poe's Criticism

Throughout his life Poe wrote a great deal of literary journalism and worked in an editorial capacity for a variety of newspapers. It was also one of his great ambitions to edit his own magazine. As a critic he was outspoken, vitriolic, and fearless. He highlighted the technical limitations of the books he reviewed, accused several authors (most famously Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ) of plagiarism, and took great delight in attacking the New England literary establishment.

Poe was not simply motivated by a disinterested concern for the health of letters; he was also desperately trying to carve his way to literary fame. That is why his criticism tended to be as sensational as his short-story writing: controversy was the equivalent of the Gothic and grotesque effects of his fiction. Without money or regular employment, Poe had to achieve celebrity status in order to survive in the literary marketplace, and if he could not be famous then he would be notorious. He did everything he could to keep his name before the public, even going to the extent of anonymously reviewing his own works.

Poe also used the pages of the popular press to fashion and present an image of himself as a man of immense erudition. In his articles, as in his short stories, he included countless quotations and phrases from various languages; he also made a great exhibition of his learning. Poe's “Marginalia,” published in newspapers during the 1840s, consists of comments and meditations that he claimed to have scribbled in the margins of the books in his library. “I sought relief,” he commented, like a latter-day Renaissance connoisseur of fine literature, “from ennui in dipping here and there at random among the volumes of my library.” The reality was quite different, however. Poe wrote the pieces as fillers for newspapers when they were short of copy, and the sad fact of the matter was that he could never afford to assemble an extensive library of his own.

Poe's most important contributions to literary criticism were his theories concerning the short story and poetry. It has been suggested that his comments on the short story, which were scattered throughout reviews of books such as Nathaniel Hawthorne 's Twice-Told Tales ( 1837 ), helped establish the genre in its modern form. Poe's theory can be briefly summarized. He was concerned above all with the effect of his tale on the reader. This effect should, he thought, be single and unified. When readers finished the story they ought be left with a totality of impression, and every element of the story—character, style, tone, plot, and so on—should contribute to that impression. Stories too long to be read at a single sitting could not, in Poe's view, achieve such powerful and unified effects—hence the brevity of his own productions. Poe also advocated the Aristotelian unities of place, time, and action and put special emphasis on the opening and conclusion of his tales. In addition, he encouraged authors to concentrate exclusively on powerful emotional and aesthetic effects—the aim of fiction, he suggested, was not a didactic one. Finally, instead of providing the reader with a transparent upper current of meaning, he thought that the meaning of a tale should be indefinite and ambiguous.

Obviously, such ideas help us understand Poe's own short stories. The Tell-Tale Heart and The Masque of the Red Death , for example, exhibit most of the above-mentioned characteristics. The theories of poetry that Poe adumbrated in book reviews and in lectures such as The Poetic Principle ( 1849 ) also help us understand his verse. In Poe's criticism there is a sense in which he was justifying his own practice as a creative writer and also attempting to create the kind of critical atmosphere in which his work would be favorably judged. Other writers, such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound , have also found this to be an effective strategy for achieving literary success. More broadly, it can be suggested that writing such as Poe's that lacks a definite content and an unambiguous message requires a theory in order to, as it were, support it and make it intelligible to the reader.

Poe's statements about poetry are similar to his pronouncements on the short story. Thus, in a review of Longfellow's Hyperion, A Romance ( 1839 ), he criticized its lack of a definite design and unified effect. Later, when commenting on the same author's Ballads and Other Poems ( 1841 ), he complained of Longfellow's didacticism and his failure to appreciate that the aim of poetry was not to instruct readers but to give them access to the world of supernal beauty. These ideas were expressed in a more theoretical form in The Poetic Principle , in which Poe criticized what he referred to as “the heresy of the didactic” and famously defined poetry as “the Rhythmical Creation of Beauty.” These ideas proved to be extremely influential and were later adapted by “art-for-art's-sake” aesthetes such as Oscar Wilde and by symbolists such as Paul Valéry . It has also been suggested that Poe's emphasis on the words on the page, rather than on external considerations such as the writer's biography, make him an important precursor of the New Critics.

The Raven and Other Poems

Poe's most influential theoretical essay was probably “The Philosophy of Composition,” published in Graham's Magazine in 1846 . Before we turn to it, however, it is necessary to consider The Raven , the inception and writing of which the essay describes. The Raven , first published in the New York Evening Mirror in January 1845 , was an instant hit with the reading public. This allusion to pop music is apt because the immediate and enormous success of the poem has been accurately compared to that of a present-day song. On its publication, Poe became an overnight sensation, and thereafter he would always be associated with the poem. In a sense this association is unfortunate, because it obscures the fact that the poem, like many of Poe's short stories, is a dramatic production. The narrator, a young man mourning the death of his love Lenore, sits in his study musing “over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore”—a character and a setting typical of Poe. As well as being a dramatic poem, it is also an intensely theatrical one: the gloomy weather, the speaking bird, and props such as the purple curtain and the bust of Pallas could have been filched from the set of a Gothic drama. The young man's language, too, is distinctly stagy; at one point he remarks to the Raven: “ ‘Sir…or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore.’ ” The effect of such distinctly camp lines is complicated; you are not sure whether to laugh or scream. In the theater, and in the theatrical world of the poem, it is of course possible to do both.

Given the theatricality of the poem, it is fitting that Poe performed it, just as Dickens performed his novels, in public and private readings. During his recitations Poe once again proved that the theater was in his blood: he would dress in black, turn the lamps down low, and chant the poem in a melodious voice. The content of the poem is of course unrealistic; like a great drama, however, it creates its own vivid and convincing reality through its solemn rhymes and its stately rhythm.

Poe's raven has become as famous as those other birds of romanticism, Keats 's nightingale, Shelley 's skylark, and Coleridge's albatross. This is ironic because, in The Philosophy of Composition , he insisted that the poem was not a romantic one. The essay was written to demonstrate that, far from being a work of inspiration, the composition of The Raven proceeded with what he called “the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem.” Along with metaphors drawn from mathematics, Poe typically (and revealingly) used images of acting to convey his detachment and self-consciousness during the writing of the poem.

Desiring to create a powerful effect of melancholy beauty that would appeal to both “the popular and the critical taste,” Poe tells us that he hit upon the saddest of all subjects: the death of a beautiful woman. This had, of course, been the subject of several of his earlier writings, such as the “marriage group” of stories in Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque . In order to make the effect of the poem intense and unified, he decided that it should be limited to around one hundred lines and that it would include a refrain composed of the single, sonorous word, Nevermore . In the remainder of the essay Poe, who might be compared here to a magician who enjoys explaining away his tricks, goes on to make numerous comments of a similar nature.

It has been suggested that The Philosophy of Composition was a typical Poe hoax, and it is highly unlikely that it is a veracious account of the actual writing of The Raven . This, however, is largely irrelevant since the essay's importance lies in the fact that it offered a novel theory of composition and a new conception of the poet. Poe was attempting to replace the idea of the inspired poet that had been established by the ancients and by contemporaries such as Coleridge with his notion of the cold and calculating author. Once again, Poe's idea proved to be extremely influential in the history of literature. It informs Valéry's conception of the poet as an extremely self-conscious artist and T. S. Eliot's idea of the impersonal author.

It is doubtful that Poe's theories would have exercised such a powerful influence had he not also embodied and dramatized them in his writings. Perhaps even more important, he also offered himself as an archetype of the kind of author he was describing. Poe presented himself, in other words, as the exemplar of the self-conscious poet, an original that poets such as Baudelaire copied.

The Raven was republished in Poe's most substantial and famous collection of verse, The Raven and Other Poems , in 1845 . The book, which was prefaced by a statement that typically succeeded in being at once self-effacing and arrogant, contained revised versions of earlier compositions such as Israfel and poems that had never previously appeared in book form. Also included in the collection were several poems that had appeared, or would later appear, in Poe's short stories. (This is a striking demonstration of the homogeneous nature of Poe's oeuvre.) The most famous of these poems are The Haunted Palace , a powerful atmospheric poem improvised by Roderick Usher, and The Conqueror Worm , written by the eponymous hero of Ligeia . In the latter, angels are in a theater watching humankind play out its meaningless “motley drama” in which there is “much of Madness and more of Sin / And horror the soul of the plot.” Suddenly, “a blood-red thing” comes onto the stage. The lights go out, the curtain comes down, and death (for it is he) holds illimitable dominion over all. In its Gothic style, its dark vision of the world, and its theatricality, the poem is characteristic of its author and indeed reads like a microcosm of his oeuvre. One obvious point that can be made in connection with the poems that appeared in Poe's short stories is that they are dramatic works (a comparison here might be made with Robert Browning's monologues). Yet again, Poe displays his great gifts as a mimic or actor, and once more we are alerted to the difficulties of reading his work in an autobiographical light.

Many of Poe's finest poems were written after the publication of The Raven and were collected in volume form posthumously. These include the onomatopoeic The Bells , the beautiful ballad Annabel Lee , and the musical masterpiece Ulalume . This last poem is perhaps the most perfect example of Poe's ability to create a mysterious and unearthly atmosphere through repetition, assonance, and the use of languorous, usually trisyllabic, words. While discussing the poem, Poe is reported to have remarked that he deliberately wrote verse that would be unintelligible to the many. Ulalume is certainly hard to understand, but like the rest of Poe's verse, its ambiguity heightens rather than diminishes its power.

Poe, the Detective Story, and Science Fiction

Between the publication of Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque in 1840 and his death in 1849 , Poe wrote numerous short stories. Among them are some of the most famous of all his writings, such as The Black Cat , The Tell-Tale Heart , The Cask of Amontillado , The Pit and the Pendulum , Hop-Frog , and The Masque of the Red Death . These stories have achieved the status of myths in the Western world; even those who have not read them know their plots. Because of the exigencies of space, and also because some of Poe's arabesque and grotesque productions have already been discussed, the focus here is on the stories that appeared in Tales ( 1845 ) and, in particular, on Poe's detective tales and science fiction. Although reviewers of Tales were, as usual, divided between those who described Poe as a great original and those who dismissed him as a showy and stylistically incompetent writer, the volume sold better than any of Poe's other publications.

Four detective stories (or “Tales of ratiocination,” as Poe called them) appeared in Tales : the prize-winning The Gold-Bug and three tales that featured the detective C. Auguste Dupin: The Purloined Letter , The Mystery of Marie Roget , and The Murders in the Rue Morgue . Although writers such as Voltaire, William Godwin , and Tobias Smollet had produced examples of what might be loosely termed crime fiction in the eighteenth century , it was these tales that established the modern short detective story as a definite and distinct form.

In The Murders in the Rue Morgue , the most famous and entertaining of Poe's detective stories, we immediately recognize the structure of the modern detective tale. A hideous and inexplicable crime is committed (the brutal murder of two women in a locked room in Paris), and all the evidence is placed before us. The police, who rely on cunning and instinct rather than rational method and imagination, are utterly baffled. Fortunately for them, an amateur genius, Dupin, is on hand to unravel the mystery. The tale (which in terms of its action is written backward) thus includes two stories: that of the crime and that of its solution and explanation by Dupin.

In creating Dupin, Poe invented the archetype of the modern detective. Among Dupin's descendents are Agatha Christie 's Hercule Poirot, G. K. Chesterton 's Father Brown, and of course Sir Arthur Conan Doyle 's Sherlock Holmes, who in one of Conan Doyle's stories actually discusses Dupin's merits. An eccentric and reclusive genius, Dupin is both a poetic visionary and a detached man of reason; he combines the attributes of the poet with those of the mathematician. In The Purloined Letter , where he unravels a mystery by identifying with the criminal, Dupin also displays an actor's power of empathy. He is, in other words, a glorified and aristocratic version of Poe. Poe also created the original of the detective's companion: a friend of average intelligence who narrates the tale and who acts, as it were, as the reader's representative within it. In The Murders in the Rue Morgue , the character is nameless; in later works by other authors he will be called Doctor Watson and Captain Hastings.

Poe is thus in large part responsible for one of the most popular and dominant forms of modern literature. After reading Poe, the French writers the Goncourt brothers believed that they had discovered “the literature of the twentieth century —love giving place to deductions…the interest of the story moved from the heart to the head…from the drama to the solution.” This prediction proved correct. Twentieth-century writers such as Jorge Luis Borges (who believed that Poe's ghost dictated detective stories to him) consciously imitated Poe, and the popularity and influence of the detective story has been, and still is, enormous. The broader point made by the Goncourt brothers concerning a literature of “the head” is also interesting. The detective story is essentially an intellectual exercise or game, and much of Poe's writing can be described in these terms. Perhaps it is this quality in his work that made it so popular and influential in the twentieth century .

The invention, or at the very least the foundation, of the modern detective story is surely Poe's greatest contribution to world literature. He has also been hailed as the father of modern science fiction. The extent to which Poe established the genre is, however, a matter of controversy. Those who have argued for his formative influence point to the futuristic, technological, and rationalistic elements of his work. It is perhaps better to approach the question through a consideration of Poe's influence, which was enormous. Poe's science fiction stories profoundly influenced later masters of the genre such as Jules Verne , H. G. Wells , and Isaac Asimov (who conflated the science fiction tale and the detective story). Among the Poe stories that have been classed as science fiction are Hans Phaall , the eponymous hero's account of his nineteen-day balloon journey to the moon, and the futuristic Mellonta Tauta . Two stories in Tales , The Colloquy of Monos and Una and The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion , have also been classified as science fiction tales.

Both are dialogues between disembodied spirits set sometime in the distant future. The dialogue form, which derives from ancients such as Lucian and Plato , was very popular in Poe's time among satirical writers such as Thomas Love Peacock, Giacomo Leopardi , and William Blake . Poe also used it for satirical purposes; in these dialogues he criticizes his age for, among other things, its exclusive belief in science. Poe's argument with science was in some respects a typically romantic one. Science and industrialization, it is suggested in The Colloquy , have given humans the false idea that they have dominion over nature and have devalued the poetic intellect.

Yet Poe went further than this conventional romantic position and challenged science's claims to objectivity and its emphasis on empiricism. So far as objectivity is concerned, reading hoax stories such as Hans Phaall leaves the impression that scientific explanations of the world are not unlike stories and that science itself may be a kind of fiction. Regarding the limitations of empiricism, Poe believed that the discovery of facts was not enough and that it is what is done with them that is important. It requires, Poe suggests, a visionary rather than a scientist to sort, connect, and shape them into theories. This visionary figure, who is both poet and mathematician, appears throughout Poe's writings. Sometimes he is Dupin, the great detective; at other times he is Poe, the theorist of poetic composition and the author of the scientific prose poem Eureka .

Poe evidently believed that Eureka , published in 1848 , was his greatest achievement: “I have no desire to live since I have done ‘Eureka,’ ” he wrote to his mother-in-law. “I could accomplish nothing more.” Indeed, he appears to have regarded it as nothing less than the solution to the secret of the universe. It is most unfortunate for humanity, therefore, that Eureka makes extremely dull reading and is very difficult to understand. One of the best attempts at a summary is contained in Kenneth Silverman 's ( 1991 ) excellent biography of Poe. Suffice it to say here that Eureka , subtitled as “Essay on the material and the spiritual universe” predicted, among other things, the annihilation and the rebirth of the universe.

Although Eureka has traditionally been regarded as a distinct work within the Poe canon, there are many connections between it and the rest of his oeuvre. Passages in short stories such as Mellonta Tauta prefigure some of its contents. In his preface to the book Poe described it as a poem rather than a “scientific” work. “I offer this Book of Truths,” he wrote, adapting Keats's famous line, “not in the character of a Truth-Teller, but for the Beauty that abounds in its Truth; constituting it True.”

The rather confused critical reception that Eureka received also made it a typical Poe production. Some reviewers read it as an elaborate hoax in the manner of Hans Phaall ; others considered it to be a prolix and labored satire of scientific discourse. Certain critics regarded it as a brilliant and sincere work of genius, yet it was also dismissed as arrant fudge. Such diverse and extreme reactions to Poe's work have already been noted; they testify to the fact that, whatever else his writing is, it is impossible to ignore.

Poe's Influence

When Poe died in Baltimore on 7 October 1849 from causes that are still the subject of debate, some commentators predicted that his works would be forgotten. They could not have been more wrong, as his books are currently read throughout the world and his influence on world literature has been extraordinary. With their consummate artistry, their self-consciousness, and their heavy atmosphere of decay, Poe's poems and tales (along with his literary persona and his theories) inspired Decadent and symbolist writers of the nineteenth century . Baudelaire, among whose earliest works were translations of Poe's stories, famously died with a copy of Poe's tales beside his bed. Mallarmé, Verlaine, Dowson, and Wilde also worshipped at the Poe shrine.

At the end of the nineteenth century , science fiction writers such as Verne and Wells and authors of detective stories such as Conan Doyle acknowledged their profound debt to Poe. It was Conan Doyle who remarked that Poe's tales “have been so pregnant with suggestion…that each is a root from which a whole literature has developed.” In the twentieth century Poe's influence was no less profound. His short stories were of immense importance to authors as diverse as Kafka, H. P. Lovecraft (who referred to his tales of horror as “Poe stories”), Vladimir Nabokov , and Stephen King. He has also had a powerful effect on every other branch of the arts. Painters such as René Magritte and Edmund Dulac were fascinated by him, and film directors such as Roger Corman and Alfred Hitchcock also took inspiration from his writings.

Poe continues to inspire and enchant people today. In the future he will no doubt attract as much hostile criticism as he has in the past, but he will survive because he will continue to be read. And despite all of the faults and all of the fudge in his writings, it is hard, in conclusion, to think of another American writer who has so drastically altered the landscape of the popular imagination or who has had such a powerful effect on his fellow artists.

Selected Works

- Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827)

- Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (1829)

- Poems by Edgar A. Poe (1831)

- The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838)

- Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840)

- The Raven and Other Poems (1845)

- Tales (1845)

- Eureka (1848)

- Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe (1969–1978)

- The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe (1976)

- The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Writings (1986)

- Poetry, Tales, and Selected Essays (1996)

Further Reading

- Carlson, Eric W. , ed. The Recognition of Edgar Allan Poe: Selected Criticism since 1829 . Ann Arbor, Mich., 1966. Collection of all of the famous essays on Poe, including those by T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, and Walt Whitman.

- Carlson, Eric W. , ed. A Companion to Poe Studies . Westport, Conn., 1996. A comprehensive collection of modern appraisals of every aspect of Poe's life and work.

- Hayes, Kevin J. The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe . Cambridge, 2002. Excellent and wide-ranging collection of late-twentieth-century Poe scholarship.

- Hyneman, Esther F. Edgar Allan Poe: An Annotated Bibliography of Books and Articles in English, 1827–1973 . Boston, 1974.

- Silverman, Kenneth . Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance . New York, 1991. Its psychoanalytic explanations are sometimes unconvincing, but it is easily the best biography available.

- Walker, I. M. , ed. Edgar Allan Poe: The Critical Heritage . New York, 1986. Anthology of contemporary reviews of Poe's work.

Related Articles

- American Detective Fiction