For the best Oliver Wyman website experience, please upgrade your browser to IE9 or later

- Global (English)

- India (English)

- Middle East (English)

- South Africa (English)

- Brazil (Português)

- China (中文版)

- Japan (日本語)

- Southeast Asia (English)

- Belgium (English)

- France (Français)

- Germany (Deutsch)

- Italy (Italiano)

- Netherlands (English)

- Nordics (English)

- Portugal (Português)

- Spain (Español)

- Switzerland (Deutsch)

- UK And Ireland (English)

This article was first published on May 17, 2021.

While change is the only constant in life, there are certainly periods where change is more amplified. We currently find ourselves in one of those periods. The world and our key industries are not immune to the ripple effects of the global pandemic. As an example, for the financial services industry, there are many drivers of change: in the short term, retail banks are facing downward pressures on net income due to record-low interest rates and increasing delinquency rates, and the need to trim costs quickly; in the medium term, new remote working routines are further accelerating digitization, automation, and disintermediation. As a result, business and operating models are trying to adapt to the “new normal.”

The firms able to effectively deliver change will thrive and are more likely to emerge stronger from these changes. However, as recent social science research has shown, delivering change is no easy task: humans have a natural bias against change. Failing to drive change is a challenge to the competitiveness and sustainability of any firm, creating monetary costs, eroding trust with customers and investors, and weighing on culture and employee engagement. On the flip side, firms that successfully deliver change set off a self-reinforcing feedback loop that increases profitability and productivity, builds trust with stakeholders, and attracts top talent.

An often forgotten institutional ‘muscle’ for firms is the ability to effectively manage change risk —the risk that a change program fails to deliver the desired goals. We believe that most firms do not proactively manage change risk in a way that commensurate with the benefits of success and the costs of failure. Effectively managing change risk is a necessary ‘muscle’ to reduce, preempt, mitigate, and manage the challenges that come with (intents of) transformation, without bringing decision paralysis or stifling innovation in the organization. We refer to change risk as a ‘silent risk’ because this ‘muscle’ is often neglected and, too often, that neglect is one of the root causes behind the inability to drive to the desired outcomes.

In our paper, we present an approach to proactively manage change risk, including:

- How to manage change across the end-to-end change lifecycle, to ensure firms develop fit for purpose mechanisms

- How change risk management is a key component of the journey, and the best ways to understand drivers of successful change

- Recommendation for four key change management capabilities, a change risk management framework, change delivery igniters, workforce change capacity management, and a process for initiative prioritization; and actions to help leaders make change management a priority

Below is an excerpt from the report, for the full PDF version, please click here .

Our views on successful change

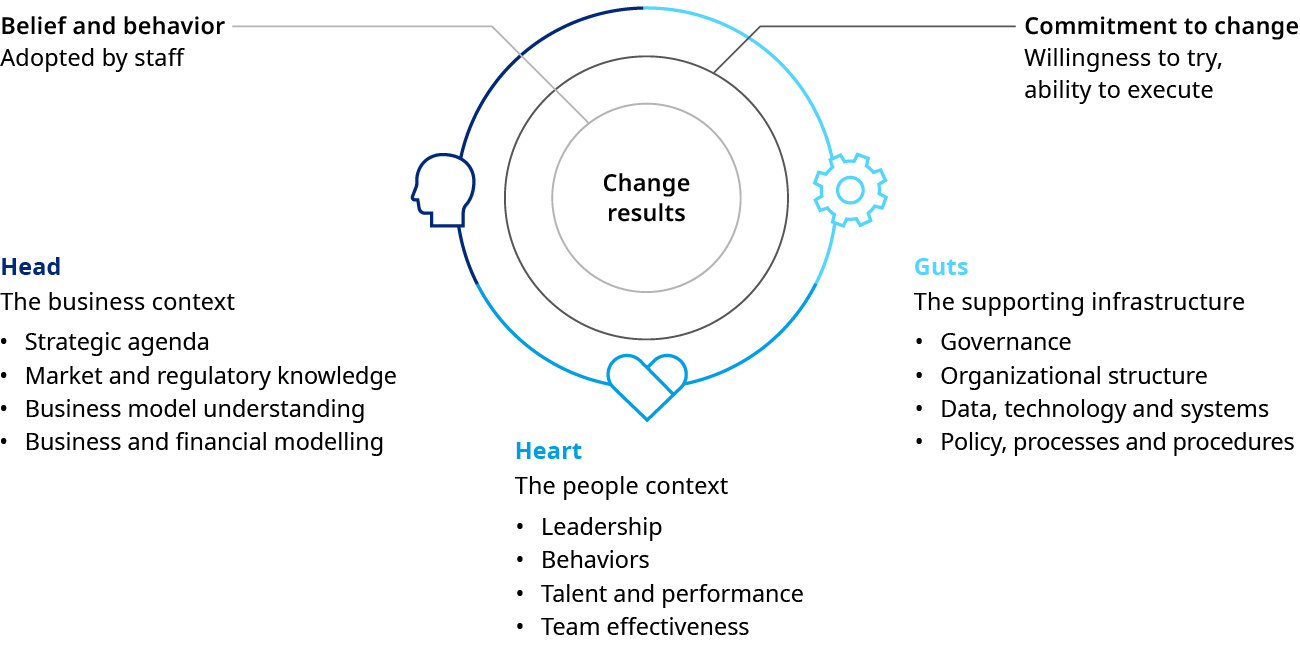

Effective change boils down to directing energy and aligning efforts toward three key elements:

- The strategy and thinking

- The people and behaviors

- The underlying infrastructure

We call these elements the Head, the Heart, and the Guts of an organization. Successful change should have risk management embedded into these key elements.

Successful change occurs when the Head, the Heart, and the Guts are fully aligned, resulting in an organization that has: (1) the willingness to change—through leadership, personal drive, and the identification of strategic value; and (2) the ability to execute—through an adequate workforce, the right infrastructure, and a clear roadmap.

Too often, firms facing change tend to focus on the Head at the expense of the Guts and, especially, the Heart. Such firms often struggle to achieve successful change because lasting change requires individuals to collectively change behaviors. For example, a firm does not become more customer-centric when rolling out a new top-down campaign or training module. Rather, the firm becomes customer-centric when the workforce begins adopting customer-centric behaviors—the way customer interactions play out; the way products are configured; and the way senior leadership communicates and makes decisions.

Change is the only constant in life Heraclitus, c. 535 BCE – 475 BCE.

Experience and research indicate that, for change to occur, each level of the organization needs to understand the objectives and purpose of the change, as well as the new behaviors to adopt. Change experts across the globe call these “vital behaviors”—the smallest actions that, if consistently repeated, will lead to the intended outcomes.

In driving change , the ability to manage change risk needs to be developed in the Guts (through risk management capabilities); the Heart (through an understanding of the workforce stoppers and capacity in the firm); and the Head (through the incorporation of change risk into the firm strategy). Our research shows that, historically, neither risk managers nor front-line risk owners have paid enough attention to managing change risk. If firms believe—as we do—that a better managed change risk is a key success factor, firms must pay more attention to driving alignment between Heart, Head, and Guts in order to achieve successful change, and also appropriately embed risk management capabilities across these elements.

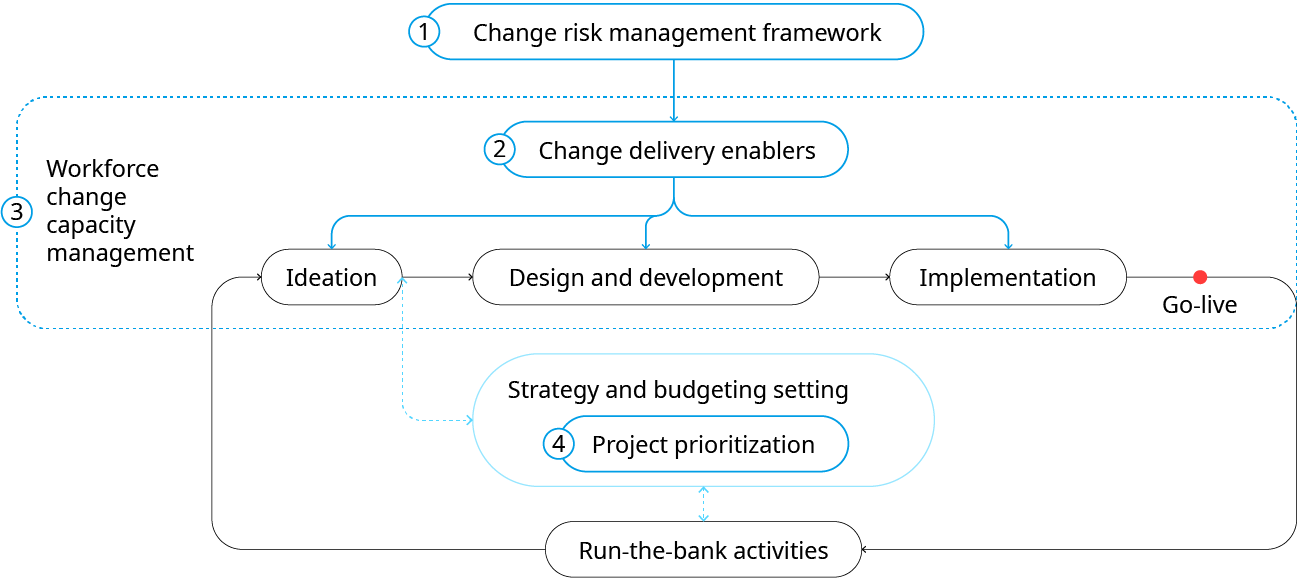

We have identified four capabilities for firms that can increase opportunities to drive effective change management:

1. Change risk management framework: Adapt the firm’s overall risk management framework to cover change risk across the lifecycle

2. Change igniters: Clear obstacles to build a change-oriented organization by diagnosing and addressing organizational weaknesses

3. Workforce change capacity management: Monitor change load and change fatigue, as well as improve organizational agility

4. Initiative prioritization: Develop a process for assessing change initiatives to maximize impact within change capacity

We believe firms that achieve these four capabilities will see an increased efficacy and decreased risk associated with the change programs. Returning to the change lifecycle in the exhibit below, we show how these capabilities can reinforce each stage and broaden the role risk management teams play well beyond the implementation and go-live steps.

Actions for effective change risk management

Given both, the necessity of achieving successful change in the current tumultuous world and the high cost of failure, organizations cannot afford to take a reactive or narrow approach to change risk management.

We recommend front-line and risk management leaders:

Overall, firms that succeed in incorporating change risk management into processes and culture will become more agile and more resilient, while firms that lag will run the risk of being caught flat-footed when the next disruption arrives. Firms that proactively manage change risk will be able to overcome the silent risk that hinders growth and emerge as winners.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Jonathan Lee and Rutger von Post for their contributions to this paper.

- Financial Services

- Risk Management for Financial Services

- Ramy Farha,

- Chris DeBrusk, and

- Antonio Tugores

Striving For Operational Resilience: The Questions Boards And Senior Management Should Ask

Operational resilience has become a key agenda item for boards and senior management. Increasing complexity in processes and IT, dependence on third parties, interconnectedness and data sharing, and sophistication of malicious actors have made disruptions more likely and their impact more severe. High-profile examples of business and operational disruptions abound, covering all segments of the financial services industry.

Non-Financial Risk Convergence And Integration

Non-Financial Risk Management has become more complex due to rapid shifts in technology, automation and greater dependence by banks on systems instead of people.

What Could Go Wrong? How to Manage Risk for Successful Change Initiatives

David Shore, instructor of Strategies for Leading Successful Change Initiatives, shares six steps to effective risk management.

David Shore

Every change initiative comes with inherent risk. But too often we shy away from exploring the potential pitfalls at the outset. If we are to succeed, however, we should embrace risk. After all, change initiatives are born from a risk analysis — a conclusion that the risk of doing nothing is higher than the risk of embarking on an experimental initiative.

When leading a change initiative, you should focus on acknowledging, anticipating, and managing risk — instead of avoiding it at all costs.

The good news is that risk management is not rocket science. Through my extensive work with change initiatives, I’ve identified six key steps to effective risk management. By following these steps on your initiative, I hope you’ll discover how embracing risk can lead to success.

Six Steps to Effective Risk Management

1. at the start, identify the risks you face..

Make a list. Formalize this process by holding a premortem . Just as a postmortem enables the team to assess what went right or wrong after the fact, a premortem provides a space for thinking in advance about what could go wrong during the project. As you and your team brainstorm, you should cast a wide net. Consider factors intrinsic to the project and also those outside the team’s control. For example, consider the risk of potential resistance from stakeholders, which nearly always arises in change initiatives.

2. Quantify the Risks.

Not all risks are created equal. The risk of a slight delay in funding might be very different from the risk of a major partner pulling out of a joint venture. By quantifying the risk, you decrease the influence emotions can play and allow different risks to be compared. One method is to assess the risk along two dimensions: the probability of the risk occurring, and the impact the risk would have if it actually occurred. Using a scale from one to five, you can evaluate each of these dimensions for the risks you’ve identified. Then, you can multiply the two numbers to produce a risk factor from 1 to 25.

3. Establish a Risk Threshold.

Consider your initiative’s tolerance for risk and then establish a threshold. If you are not sure where to start, set your threshold at the center of your risk scale. For example, on a scale of 1 to 25, start with 12 as your threshold. Compare your quantified risks to the threshold and then spend some time thinking about the ones that exceed the threshold and then adjust as needed.

Search all Business Strategy programs.

4. Create Contingency Plans.

For each risk, engage in a thought experiment. First, think about what steps you can take, if any, to eliminate or mitigate the risk. It may be that a small adjustment to your plan will reduce the probability to zero. Second, think about what you plan to do if that possibility becomes reality — in other words, if the risk becomes an issue. Will the team be able to work around it easily? Or will the magnitude of that risk require rethinking your entire initiative? The more you plan for risks ahead of time, the better prepared you will be — and the more successful you will be in keeping your initiative on track

5. Monitor Risks over Time.

Along with the Gantt charts, status reports, dashboards, and other tools that help you assess your progress, you can also create a Risk Register (also called a Risk Log) that sets out all the risks, their risk factors, and current status. As you reach a particular milestone, perhaps one risk can be eliminated from consideration because it is no longer possible. Perhaps another risk has created an issue that needs to be dealt with. Or perhaps a new risk has been identified and should be evaluated. Your goal is to keep a close eye on risk throughout the project.

6. Consider Assigning a Risk Watcher.

You may want to identify a particular team member who has the responsibility to monitor risks and raise flags. Teams working on change initiatives are by definition optimistic. While everyone else on the team might be saying, “This will go fine,” someone needs to be able to say, “Clouds are rolling in” or “We’ve said that for the last six meetings and it hasn’t happened.”

To manage risk successfully, you need to be proactive in anticipating it. And to lead a change initiative successfully, you need to be an honest communicator. Talk with your team and with upper management about risks to the project and issues that crop up along the way. As a manager, you can improve your ability to manage risk by fostering a culture that values positive thinking while encouraging open discussions about problems.

Embracing change means embracing risk. With the right pragmatic approach, you can become a more effective change agent by understanding risk as a natural part of change — and by anticipating and managing it.

Find related Business Strategy programs.

Browse all Professional & Executive Development programs.

About the Author

Shore is an authority on change management recognized as distinguished professor at Tianjin University of Finance and Economics and 2015 Top Thought Leader in Trust.

Why Marketers Should Start Thinking Like Designers

Follow this 5-step process for applying design thinking to your marketing strategy.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

How to Identify and Mitigate Risks During the Change Process

Change Strategists

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

Are you in the process of making changes within your organization? Whether it’s a new software implementation or a company-wide restructuring, change can bring about uncertainty and risk. It’s important to identify and mitigate these risks to ensure a smooth transition and minimize potential negative impacts.

Effective risk management is essential for any successful change process. By conducting a thorough risk assessment, developing a mitigation strategy, and implementing and monitoring risk controls, you can identify potential issues before they become major problems.

In this article, we will provide you with a step-by-step guide on how to identify and mitigate risks during the change process. By following these guidelines, you can ensure that your change process is successful and your organization can thrive in the long run.

Understanding the Importance of Risk Management

You gotta know that managing risk is crucial when making any changes. As you move forward with a change process, there are a lot of uncertainties and potential pitfalls that could arise. That’s where risk identification comes in.

By analyzing the potential risks associated with the change, you can better prepare for them and minimize their impact on the project. Once you’ve identified the potential risks, it’s important to develop risk mitigation techniques.

This means coming up with a plan to reduce the likelihood or impact of each potential risk. For example, if you’re implementing new software, you might identify the risk that the system could crash during the implementation process. A mitigation technique for this risk might be to conduct thorough testing before rolling out the new software to ensure it’s stable.

Effective risk management requires ongoing attention throughout the change process. You can’t just identify the risks and develop mitigation techniques at the beginning of the project and call it good. You need to consistently monitor and reassess the risks as the project progresses.

This will allow you to adjust your mitigation techniques as needed and ensure that you’re always prepared for any potential risks that may arise.

Conducting a Risk Assessment

Now that you’ve gathered all necessary information, it’s time to assess potential hazards and determine the likelihood of negative outcomes. Conducting a risk assessment is crucial in identifying common risks and minimizing their impact on your change process. Here are a few tips to help you conduct a successful risk assessment:

- Use risk assessment tools : There are various tools available to assess risks, such as SWOT analysis, PEST analysis, and FMEA. These tools help you identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of your change process. They also help you identify potential risks and develop strategies to mitigate them.

- Involve stakeholders : Your stakeholders have valuable insights that can help you identify potential risks. Involve them in the risk assessment process to gain a better understanding of the potential challenges and their impact on the change process. This will also help you gain their support for the change.

- Prioritize risks : Not all risks are equal in terms of their impact on the change process. Prioritize the risks based on their likelihood and severity. This will help you focus on the most critical risks and develop strategies to mitigate them.

By conducting a risk assessment, you can identify potential hazards and develop strategies to mitigate them. This will help you minimize the impact on your change process and ensure its success. Remember, risk management is an ongoing process, and you should regularly review and update your risk assessment to ensure its effectiveness.

Developing a Mitigation Strategy

In the current section, we’ll be developing a plan to minimize the negative impact of potential hazards on our change goals. Change management is not just about identifying risks but also about developing a mitigation strategy to respond to them. This is where risk response comes in. Risk response involves developing a plan to mitigate the impact of risks on the change process.

To develop a mitigation strategy for potential hazards, it is important to understand the different types of risks that might occur during the change process. You can do this by conducting a thorough risk assessment, which we have discussed in the previous subtopic. Once you have identified the different types of risks, you can then begin to develop a mitigation strategy that addresses each risk.

A useful way to develop a mitigation strategy is to use a table that outlines each risk, its potential impact, and the actions that can be taken to mitigate it. This table can be used as a reference throughout the change process to ensure that all risks are being addressed. By taking a proactive approach to risk management, you can ensure that your change process is successful and that any potential hazards are minimized.

Implementing and Monitoring Risk Controls

We’ll now focus on putting our plan into action to ensure that any potential issues are kept in check. After developing a mitigation strategy, it’s crucial to implement and monitor risk controls to ensure their effectiveness.

Implementing risk controls means applying the plans and actions outlined in the mitigation strategy. This includes assigning tasks to team members, creating a timeline for completion, and ensuring that everyone is aware of their responsibilities.

Continuous monitoring is essential to ensure that risk controls are effective. It involves regularly checking whether the risk controls are working as intended and if any new risks have emerged. Monitoring can be done through regular meetings with team members, reviewing progress reports, and conducting risk assessments.

Monitoring can also help identify areas for improvement in the risk controls and provide an opportunity to adjust the mitigation strategy if necessary.

In summary, implementing and monitoring risk controls is crucial in identifying and mitigating potential risks during the change process. By putting the mitigation strategy into action and continuously monitoring the effectiveness of risk controls, organizations can reduce the likelihood of issues arising. This approach ensures that the organization is well-prepared to handle any unforeseen challenges that may arise during the change process.

Creating a Contingency Plan for Unforeseen Circumstances

Preparing for the unexpected is like having a safety net – it’s important to have a contingency plan in place to handle any unforeseen circumstances that may arise during the implementation of the risk controls.

Contingency planning involves identifying potential risks and developing risk response strategies to mitigate them. This process helps to ensure that the project stays on track and that any unexpected events are handled effectively.

A contingency plan should include a detailed description of potential risks and how they will be addressed. This plan should also identify the key stakeholders who will be responsible for executing the plan and specify the timeline for implementation.

In addition, the contingency plan should outline the communication strategy for informing all stakeholders of the unforeseen circumstances and the actions that will be taken to address them.

In summary, creating a contingency plan is an essential part of managing risks during the change process. It helps to ensure that the project stays on track and that any unforeseen circumstances are handled effectively. By identifying potential risks and developing risk response strategies, you can mitigate the impact of unexpected events and ensure the success of your project.

How Can Effective Change Communication Mitigate Risks During the Change Process?

Effective change communication planning insights can help mitigate risks during the change process by keeping all stakeholders informed and engaged. Clear and timely communication can address concerns, manage expectations, and foster support for the change. By providing relevant information, addressing potential resistance, and ensuring transparency, communication planning insights can help minimize disruptions and maximize successful change implementation.

In conclusion, managing risks during the change process is a critical task that requires your utmost attention. By conducting a thorough risk assessment, you can identify potential risks and develop a mitigation strategy that will help reduce the likelihood of these risks occurring.

This will ensure that your change process runs smoothly and efficiently, with minimal disruption to your organization. However, it’s important to remember that risks are an inevitable part of any change process, and it’s impossible to eliminate them entirely.

Therefore, it’s essential to implement and monitor risk controls, and to create a contingency plan for unforeseen circumstances. As the saying goes, “expect the best, but prepare for the worst.” By taking a proactive approach to risk management, you can minimize the impact of any unforeseen events and ensure that your change process is successful.

About the author

If you want to grow your business visit Growth Jetpack program . And if you want the best technology to grow your online brand visit Clixoni .

Latest Posts

How to Maintain Employee Morale Amidst Role Changes

Uncover the essential strategies to uphold employee morale during role changes, ensuring a resilient workforce in times of transition.

Workplace Hazards Unveiled: Prevention Strategies Revealed

Curious about how to combat workplace hazards? Explore effective prevention strategies and keep your workplace safe.

The Impact of AI on Business Marketing

Innovative AI applications are transforming business marketing strategies, elevating customer engagement and driving unparalleled growth – discover the groundbreaking impact.

Value and resilience through better risk management

Today’s corporate leaders navigate a complex environment that is changing at an ever-accelerating pace. Digital technology underlies much of the change. Business models are being transformed by new waves of automation, based on robotics and artificial intelligence. Producers and consumers are making faster decisions, with preferences shifting under the influence of social media and trending news. New types of digital companies are exploiting the changes, disrupting traditional market leaders and business models. And as companies digitize more parts of their organization, the danger of cyberattacks and breaches of all kinds grows.

Stay current on your favorite topics

Beyond cyberspace, the risk environment is equally challenging. Regulation enjoys broad popular support in many sectors and regions; where it is tightening, it is putting stresses on profitability. Climate change is affecting operations and consumers and regulators are also making demands for better business conduct in relation to the natural environment. Geopolitical uncertainties alter business conditions and challenge the footprints of multinationals. Corporate reputations are vulnerable to single events, as risks once thought to have a limited probability of occurrence are actually materializing.

The role of the board and senior executives

Risk management at nonfinancial companies has not kept pace with this evolution. For many nonfinancial corporates, risk management remains an underdeveloped and siloed capability in the organization, receiving limited attention from the most senior leaders. From over 1,100 respondents to McKinsey’s Global Board Survey for 2017 , we discovered that risk management remains a relatively low-priority topic at board meetings (exhibit).

A long way to go

Boards spend only 9 percent of their time on risk—slightly less than they did in 2015. Other questions in the survey revealed that only 6 percent of respondents believe that they are effective in managing risk (again, less than in 2015). Some individual risk areas are relatively neglected, and even cybersecurity, a core risk area with increasing importance, is addressed by only 36 percent of boards. While many senior executives stay focused on strategy and performance management, they often fail to challenge capabilities or strategic decisions from a risk perspective (see sidebar, “A long way to go”). A reactive approach to risks remains too common, with action taken only after things go wrong. The result is that boards and senior executives needlessly put their companies at risk, while personally taking on higher legal and reputational liabilities.

Boards have a critical role to play in developing risk-management capabilities at the companies they oversee. First, boards need to ensure that a robust risk-management operating model is in place. Such a model allows companies to understand and prioritize risks, set their risk appetite, and measure their performance against these risks. The model should enable the board and senior executives to work with businesses to eliminate exposures outside the company’s appetite statement, reducing the risk profile where warranted, through such means as quality controls and other operational processes. On strategic opportunities and risk trade-offs, boards should foster explicit discussions and decision making among top management and the businesses. This will enable the efficient deployment of scarce risk resources and the active, coordinated management of risks across the organization. Companies will then be prepared to address and manage emerging crises when risks do materialize.

A sectoral view of risks

Most companies operate in a complex, industry-specific risk environment. They must navigate macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainties and face risks arising in the areas of strategy, finance, products, operations, and compliance and conduct. In some sectors, companies have developed advanced approaches to managing risks that are specific to their business models. These approaches can sustain significant value. At the same time companies are challenged by emerging types of risks for which they need to develop effective mitigation plans; in their absence, the losses from serious risk events can be crippling.

- Automotive companies are controlling supply-chain risks with sophisticated monitoring models that allow OEMs to identify potential risks upfront across the supply chain. At the same time, auto companies must address the strategic challenge of shifting toward electric-powered and autonomous vehicles.

- Pharma companies seek to manage the downside risk of large investments in their product portfolio and pipeline, while addressing product quality and patient safety to comply with relevant regulatory requirements.

- Oil and gas, steel, and energy companies apply advanced approaches to manage the negative effects of financial markets and commodity-price volatility. As social and political demands for cleaner energy are increasing, these companies are actively pursuing growth opportunities to shift their portfolios in anticipation of an energy transition and a low-carbon future.

- Consumer-goods companies protect their reputation and brand value through sound practices to manage product quality as well as labor conditions in their production facilities. Yet they are constantly challenged to meet consumers’ ever-changing tastes and needs, as well as consumer-protection regulations.

Toward proactive risk management

An approach based on adherence to minimum regulatory standards and avoidance of financial loss creates risk in itself. In a passive stance, companies cannot shape an optimal risk profile according to their business models nor adequately manage a fast-moving crisis. Eschewing a risk approach comprised of short-term performance initiatives focused on revenue and costs, top performers deem risk management as a strategic asset, which can sustain significant value over the long term. Inherent in the proactive approach are several essential components.

Strategic decision making

More rigorous, debiased strategic decision making can enhance the longer-term resilience of a company’s business model, particularly in volatile markets or externally challenged industries. Research shows that the active, regular reevaluation of resource allocation, based on sound assessments of risk and return trade-offs (such as entering markets where the business model is superior to the competition), creates more value and better shareholder returns. 1 See, for example, Yuval Atsmon, “ How nimble resource allocation can double your company’s value ,” August 2016; William N. Thorndike, Jr., The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success , Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2012; Rebecca Darr and Tim Koller, “ How to build an alliance against corporate short-termism ,” January 2017. Flexibility is empowering in a dynamic marketplace. Many companies use hedging strategies to insure against market uncertainties. Airlines, for example, have been known to hedge future exposures to fuel-price fluctuations, a move that can help maintain profitability when prices climb. Likewise, strategic investing, based on a longer-term perspective and a deep understanding of a company’s core proposition, generates more value than opportunistic moves aiming at a short-term bump in the share price.

Debiasing and stress-testing

Approaches that include debiasing and stress-testing help senior executives consider previously overlooked sources of uncertainty to judge whether the company’s risk-bearing capacity can absorb their potential impact. A utility in Germany, for example, improved decision making by taking action to mitigate behavioral biases. As a result, it separated its renewables business from its conventional power-generation operations. In the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster, which sharply raised interest in environmentally friendly power generation, the utility’s move led to a significant positive effect on its share price (15 percent above the industry index).

Higher-quality products and safety standards

Investments in product quality and safety standards can bring significant returns. One form this takes in the energy sector is reduced damage and maintenance costs. At one international energy company, improved safety standards led to a 30 percent reduction in the frequency of hazardous incidents. Auto companies with reputations built on safety can command higher prices for their vehicles, while the better reputation created by higher quality standards in pharma creates obvious advantages. As well as the boost in demand that comes from a reputation for quality, companies can significantly reduce their remediation costs—McKinsey research suggests that pharma companies suffering from quality issues lose annual revenue equal to 4 to 5 percent of cost of goods sold.

Comprehensive operative controls

These can lead to more efficient and effective processes that are less prone to disruption when risks materialize. In the auto sector, companies can ensure stable production and sales by mitigating the risk of supply-chain disruption. Following the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, a leading automaker probed potential supply bottlenecks and took appropriate action. After an earthquake in 2016, the company quickly redirected production of affected parts to other locations, avoiding costly disruptions. In high-tech, companies applying superior supply-chain risk management can achieve lasting cost savings and higher margins. One global computer company addressed these risks with a dedicated program that saved $500 million during its first six years. The program used risk-informed contracts, enabling suppliers to lower the costs and risks of doing business with the company. The measures achieved supply assurance for key components, particularly during market shortages, improved cost predictability for components that have volatile costs, and optimized inventory levels internally and at suppliers.

Stronger ethical and societal standards

To achieve standing among customers, employees, business partners, and the public, companies can apply ethical controls on corporate practices end to end. If appropriately publicized and linked to corporate social responsibility, a program of better ethical standards can achieve significant returns in the form of heightened reputation and brand recognition. Customers, for example, are increasingly willing to pay a premium for products of companies that adhere to tighter standards. Employees too appreciate being associated with more ethical companies, offering a better working environment and contributing to society.

The three dimensions of effective risk management

Ideally, risk management and compliance are addressed as strategic priorities by corporate leadership and day-to-day management. More often the reality is that these areas are delegated to a few people at the corporate center working in isolation from the rest of the business. By contrast, revenue growth or cost savings are deeply embedded in corporate culture, linked explicitly to profit-and-loss (P&L) performance at the company level. Somewhere in the middle are specific control capabilities regarding, for example, product safety, secure IT development and deployment, or financial auditing.

Would you like to learn more about our Risk Practice ?

To change this picture, leadership must commit to building robust, effective risk management. The project is three-dimensional: 1) the risk operating model, consisting of the main risk management processes; 2) a governance and accountability structure around these processes, leading from the business up to the board level; and 3) best-practice crisis preparedness, including a well-articulated response playbook if the worst case materializes.

1. Developing an effective risk operating model

The operating model consists of two layers, an enterprise risk management (ERM) framework and individual frameworks for each type of risk. The ERM framework is used to identify risks across the organization, define the overall risk appetite, and implement the appropriate controls to ensure that the risk appetite is respected. Finally, the overarching framework puts in place a system of timely reporting and corresponding actions on risk to the board and senior management. The risk-specific frameworks address all risks that are being managed. These can be grouped in categories, such as financial, nonfinancial, and strategic. Financial risks, such as liquidity, market, and credit risks, are managed by adhering to appropriate limit structures; nonfinancial risks, by implementing adequate process controls; strategic risks, by challenging key decisions with formalized approaches such as debiasing, scenario analyses, and stress testing. While financial and strategic risks are typically managed according to the risk-return trade-off, for nonfinancial risks, the potential downside is often the key consideration.

Finding the right level of risk appetite

Companies need to find the right level of risk appetite, which helps ensure long-term resilience and performance. Risk appetite that is too relaxed or too restrictive can have severe consequences on company financials, as the following two examples indicate:

Too relaxed. One nuclear energy company set its standards for steel equipment in the 1980s and did not review them even when the regulations changed. When the new higher standards were applied to the manufacture of equipment for nuclear power plants, the company fell short of compliance. An earlier adaptation of its risk appetite and tolerance levels would have been significantly less costly.

Too restrictive. A pharma company set quality tolerances to produce a drug to a significantly stricter level than what was required by regulation. At the beginning of production, tolerance intervals could be fulfilled, but over time, quality could no longer be assured at the initial level. The company was unable to lower standards, as these had been communicated to the regulators. Ultimately, production processes had to be upgraded at a significant cost to maintain the original tolerances.

As well as assessing risk based on likelihood and impact, companies must also assess their ability to respond to emerging risks. Capabilities and capacities needed to manage these risks should be evaluated and gaps filled accordingly. Of particular importance in crisis management is the timeliness of an effective response when things go awry. The highly likely, high-impact risk events on which risk management focuses most of its attention often emerge with disarming velocity, taking many companies unawares. To be effective, the enterprise risk management framework must ensure that the two layers are seamlessly integrated. It does this by providing clarity on risk definitions and appetite as well as controls and reporting.

- Taxonomy. A company-wide risk taxonomy should clearly and comprehensively define risks; the taxonomy should be strictly respected in the definition of risk appetite, in the development of risk policy and strategy, and in risk reporting. Taxonomies are usually industry-specific, covering strategic, regulatory, and product risks relevant to the industry. They are also determined by company characteristics, including the business model and geographical footprint (to incorporate specific country and legal risks). Proven risk-assessment tools need to be adopted and enhanced continuously with new techniques, so that newer risks (such as cyberrisk) are addressed as well as more familiar risks.

- Risk appetite. A clear definition of risk appetite will translate risk-return trade-offs into explicit thresholds and limits for financial and strategic risks, such as economic capital, cash-flow at risk, or stressed metrics. In the case of nonfinancial risks like operational and compliance risks, the risk appetite will be based on overall loss limits, categorized into inherent and residual risks (see sidebar, “Finding the right level of risk appetite”).

- Risk control processes. Effective risk control processes ensure that risk thresholds for the specified risk appetite are upheld at all levels of the organization. Leading companies are increasingly building their control processes around big data and advanced analytics. These powerful new capabilities can greatly increase the effectiveness and efficiency of risk monitoring processes. Machine-learning tools, for example, can be very effective in monitoring fraud and prioritizing investigations; automated natural language processing within complaints management can be used to monitor conduct risk.

- Risk reporting. Decision making should be informed with risk reporting. Companies can regularly provide boards and senior executives with insights on risk, identifying the most relevant strategic risks. The objective is to ensure that an independent risk view, encompassing all levels of the organization, is embedded into the planning process. In this way, the risk profile can be upheld in the management of business initiatives and decisions affecting the quality of processes and products. Techniques like debiasing and the use of scenarios can help overcome biases toward fulfilment of short-term goals. A North American oil producer developed a strategic hypothesis given uncertainties in global and regional oil markets. The company used risk modelling to test assumptions about cash flow under different scenarios and embedded these analyses into the reports reviewed by senior management and the board. Weak points in the strategy were thereby identified and mitigating actions taken.

2. Toward robust risk governance, organization, and culture

The risk operating model must be managed through an effective governance structure and organization with clear accountabilities. The governance model maintains a risk culture that strongly reinforces better risk and compliance management across the three lines of defense—business and operations, the compliance and risk functions, and audit. The approach recognizes the inherent contradiction in the first line between performance (revenue and costs) and risk (losses). The role of the second line is to review and challenge the first line on the effectiveness of its risk processes and controls, while the third line, audit, ensures that the lines one and two are functioning as intended.

- Three lines of defense. Effective implementation of the three lines involves the sharp definition of lines one and two at all levels, from the group level through the lines of business, to the regional and legal entity levels. Accountabilities regarding risk and control management must be clear. Risk governance may differ by risk type: financial risks are usually managed centrally, while operational risks are deeply embedded into company processes. The operational risk of any line of business is managed by the business owning the product-development, production, and sales processes. This usually translates into forms of quality control, but the business must also balance the broader impact of risk and P&L. In the development of new diesel engines, automakers lost sight of the balance between compliance risk and the additional cost to meet emission standards, with disastrous results. Risk or compliance functions can only complement these activities by independently reviewing the adequacy of operational risk management, such as through technical standards and controls.

- Reviewing the risk appetite and risk profile. Of central importance within the governance structure are the committees that define the risk appetite, including the parameters for doing business. These committees also make specific decisions on top risks and review the control environment for enhancements as the company’s risk profile changes. Good governance in this case means that risk decisions are considered within the existing divisional, regional, and senior-management governance structure of a company, supported by risk, compliance, and audit committees.

- Integrated risk and compliance governance setup. A robust and adequately staffed risk and compliance organization supports all risk processes. The integrated risk and compliance organization provides for single ownership of the group-wide ERM framework and standards, appropriate clustering of second-line functions, a clear matrix between divisions and control functions, and centralized or local control as needed. A clear trend is observable whereby the ERM layer responsible for group-wide standards, risk processes, and reporting becomes consolidated, whereas the expert teams setting and monitoring specific control standards for the business (including standards for commercial, technical compliance, IT or cyberrisks) become specialized teams covering both regulatory compliance as well as risk aspects.

- Resources. Appropriate resources are a critical factor in successful risk governance. The size of the compliance, risk, audit, and legal functions of nonfinancial companies (0.5 for every 100 employees, on average), are usually much smaller than those of banks (6.9 for every 100 employees). The disparity is partly a natural outcome of financial regulation, but some part of it reflects a capability gap in nonfinancial corporates. These companies usually devote most of their risk and control resources in sector-specific areas, such as health and safety for airlines and nuclear power companies or quality assurance for pharmaceutical companies. The same companies can, however, neglect to provide sufficient resources to monitor highly significant risks, such as cyberrisk or large investments.

- Risk culture. An enhanced risk culture covers mind-sets and behaviors across the organization. A shared understanding is fostered of key risks and risk management, with leaders acting as role models. Especially important are capability-building programs on risk as well as formal mechanisms to assess and reinforce sound risk management practices.

An enhanced risk culture covers mind-sets and behaviors across the organization. A shared understanding is fostered of key risks and risk management, with leaders acting as role models.

3. Crisis preparedness and response

A high-performing, effective risk operating model and governance structure, with a well-developed risk culture minimize the probability of corporate crises , without, of course, completely eliminating them. When unexpected crises strike at high velocity, multinational companies can lose billions in value in the first days and soon find themselves struggling to keep their market position. A best-in-class risk management environment provides the ideal conditions for preparation and response.

- Ensure board leadership. The most important action companies can take to prepare for crises is to ensure that the effort is led by the board and senior management. Top leadership must define the main expected threats, the worst-case scenarios, and the actions and communications that will be accordingly rolled out. For each threat, hypothetical scenarios should be developed for how a crisis will unfold, based on previous crises within and beyond the company’s industry and region.

- Strengthen resilience. By mapping patterns that arose in previous crises, companies can test their own resilience, challenging key areas across the organization for potential weaknesses. Targeted countermeasures can then be developed in advance to strengthen resilience. This crucial aspect of crisis preparedness can involve reviewing and revising the terms and conditions for key suppliers, shoring up financials to ensure short-term availability of cash, or investing in advanced cybersecurity measures to protect essential data and software in the event of failures and breaches.

- Develop action plans and communications. Once these assessments are complete and resilience-building countermeasures are in place, the company can then develop action plans for each threat. The plans must be well articulated, founded on past crises, and address operational and technical planning, financial planning, third-party management, and legal planning. Care should be taken to develop an optimally responsive communications strategy as well. The correct strategy will enable frontline responders to keep pace with or stay ahead of unfolding crises. Communications failures can turn manageable crises into irredeemable catastrophes. Companies need to have appropriate scripts and process logic in place detailing the response to crisis situations, communicated to all levels of the organization and well anchored there. Airlines provide an example of the well-articulated response, in their preparedness for an accident or crash. Not only are detailed scripts in place, but regular simulations are held to train employees at all levels of the company.

- Train managers at all levels. The company should train key managers at multiple levels on what to expect and enable them to feel the pressures and emotions in a simulated environment. Doing this repeatedly and in a richer way each time will significantly improve the company’s response capabilities in a real crisis situation, even though the crisis may not be precisely the one for which managers have been trained. They will also be valuable learning exercises in their own right.

- Put in place a detailed crisis-response playbook. While each crisis can unfold in unique and unpredictable ways, companies can follow a few fundamental principles of crisis response in all situations. First, establish control immediately after the crisis hits, by closely determining the level of exposure to the threat and identifying a crisis-response leader, not necessarily the CEO, who will direct appropriate actions accordingly. Second, involved parties—such as customers, employees, shareholders, suppliers, government agencies, the media, and the wider public—must be effectively engaged with a dynamic communications strategy. Third, an operational and technical “war room” should be set up, to stabilize primary threats and determine which activities to sustain and which to suspend (identifying and reaching out to critical suppliers). Finally, a deliberate effort must be made to address and neutralize the root cause of the crisis and so bring it to an end as soon as possible.

In a digitized, networked world, with globalized supply chains and complex financial interdependencies, the risk environment has grown more perilous and costly. A holistic approach to risk management, based on the lessons, good and bad, of leading companies and financial institutions, can derive value from that environment. The path to risk resilience that is emerging is an effort, led by the board and senior management, to establish the right risk profile and appetite. Success depends on the support of a thriving risk culture and state-of-the-art crisis preparedness and response. Far from minimal regulatory adherence and loss avoidance, the optimal approach to risk management consists of fundamentally strategic capabilities, deeply embedded across the organization.

Daniela Gius is a senior expert in McKinsey’s Hamburg office, Jean-Christophe Mieszala is a senior partner in the Paris office, Ernestos Panayiotou is a partner in the Athens office, and Thomas Poppensieker is a senior partner in the Munich office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The business logic in debiasing

Are you prepared for a corporate crisis?

Nonfinancial risk today: Getting risk and the business aligned

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Managing Risks: A New Framework

- Robert S. Kaplan

- Anette Mikes

Risk management is too often treated as a compliance issue that can be solved by drawing up lots of rules and making sure that all employees follow them. Many such rules, of course, are sensible and do reduce some risks that could severely damage a company. But rules-based risk management will not diminish either the likelihood or the impact of a disaster such as Deepwater Horizon, just as it did not prevent the failure of many financial institutions during the 2007–2008 credit crisis.

In this article, Robert S. Kaplan and Anette Mikes present a categorization of risk that allows executives to understand the qualitative distinctions between the types of risks that organizations face. Preventable risks, arising from within the organization, are controllable and ought to be eliminated or avoided. Examples are the risks from employees’ and managers’ unauthorized, unethical, or inappropriate actions and the risks from breakdowns in routine operational processes. Strategy risks are those a company voluntarily assumes in order to generate superior returns from its strategy. External risks arise from events outside the company and are beyond its influence or control. Sources of these risks include natural and political disasters and major macroeconomic shifts. Risk events from any category can be fatal to a company’s strategy and even to its survival.

Companies should tailor their risk management processes to these different risk categories. A rules-based approach is effective for managing preventable risks, whereas strategy risks require a fundamentally different approach based on open and explicit risk discussions. To anticipate and mitigate the impact of major external risks, companies can call on tools such as war-gaming and scenario analysis.

Smart companies match their approach to the nature of the threats they face.

Editors’ note: Since this issue of HBR went to press, JP Morgan, whose risk management practices are highlighted in this article, revealed significant trading losses at one of its units. The authors provide their commentary on this turn of events in their contribution to HBR’s Insight Center on Managing Risky Behavior.

- Robert S. Kaplan is a senior fellow and the Marvin Bower Professor of Leadership Development emeritus at Harvard Business School. He coauthored the McKinsey Award–winning HBR article “ Accounting for Climate Change ” (November–December 2021).

- Anette Mikes is a fellow at Hertford College, Oxford University, and an associate professor at Oxford’s Saïd Business School.

Partner Center

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Explore the Levels of Change Management

The Costs and Risks of Poorly Managed Change

Tim Creasey

Updated: March 2, 2024

Published: January 19, 2022

When the people side of change is ignored or poorly managed, the project and the organization take on additional costs and risks. When you consider it from this perspective, effective change management is a cost avoidance technique, risk mitigation tactic, and justifiable investment . Here's an overview of common costs and risks, and how to position change management to clearly communicate and share its benefits.

Consequences of Poor Change Management

It's likely that we have all experienced a poorly managed organizational change at some point, either as an offender or victim. We know from experience that when this happens, the individual changes that culminate in organizational change do not take place. We know that when the "people side of change" is mismanaged, projects don't realize the results and outcomes desired. We know that we have a lower likelihood of meeting objectives, finishing on time, and finishing on budget . And we know that speed of adoption will be slower, ultimate utilization will be lower, and proficiency will be lacking—all dragging down expected returns.

Ignoring or mismanaging change manifests as costs and risks that play out on both the project level and organizational level. While some of these costs and risks may seem soft, many are quantifiable and can have a significant impact on financial performance for the project and the organization as a whole.

Project-level costs and risks of mismanaged change

Project-level impacts relate directly to the specific project or initiative forgoing change management. These projects can impact tools, technologies, processes, reporting structures and job roles. They can result from strategic planning, internal stimuli such as performance issues, external stimuli such as regulation or competitive threats, or demands by customers and suppliers. The initiatives may be formalized as projects with project managers, budgets, schedules, etc., or they may be informal in nature but still impact how people do their jobs.

While these projects can take on a number of different forms, the fact remains that ignoring or mismanaging the people side of change has real consequences for project performance:

- Project delays

- Missed milestones

- Budget overruns

- Rework required on design

- Loss of work by project team

- Resistance

- Project put on hold

- Resources not made available

- Obstacles appear unexpectedly

- Project fails to deliver results

- Project is fully abandoned

When we apply change management effectively , we can prevent or avoid costs and mitigate risks tied to how individual employees adopt and utilize a change.

Organization-level costs and risks of mismanaged change

The organizational level is a step above the project-level impacts. These costs and risks are felt not only by the project team, but by the organization as a whole. Many of these impacts extend well beyond the lifecycle of a given project. When valuable employees leave the organization, the costs are extreme. A legacy of failed change presents a significant and ever-present backdrop that all future changes will encounter.

The organizational costs and risks of poorly managing change include:

- Productivity plunges (deep and sustained)

- Loss of valued employees

- Reduced quality of work

- Impact on customers

- Impact on suppliers

- Decline in morale

- Legacy of failed change

- Stress, confusion and fatigue

- Change saturation

Applying change management effectively on a particular project or initiative allows you to avoid organizational costs and risks that last well beyond the life of the project.

Costs and risks of failing to deliver results and outcomes

There is one final dimension of costs and risks to consider, beyond the project and organizational impacts. When we try to introduce a change without using effective change management, we are much less likely to implement the change and fully realize the expected results and outcomes. This final dimension provides answers to the question: What if the change is not fully implemented?

If the change does not deliver the results and outcomes—in large part because we ignored the people side of change —there are additional costs and risks.

Costs if the change is not fully implemented:

- Lost investment made in the project

- Lost opportunity to have invested in other projects

Risks if the change is not fully implemented:

- Expenses not reduced

- Efficiencies not gained

- Revenue not increased

- Market share not captured

- Waste not reduced

- Regulations not met

Change Risks and Change Management

Discussing the costs and risks of poorly managed change is yet another way to make the case for change management . Positioning change management as a cost avoidance technique or a risk mitigation tactic can be an effective approach for communicating change management's value or to get support for the resources you need for managing the people side of change.

Tim Creasey is Prosci’s Chief Innovation Officer and a globally recognized leader in Change Management. Their work forms the basis of the world's largest body of knowledge on managing the people side of change to deliver organizational results.

See all posts from Tim Creasey

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 3 MINS

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Change Management

Are You Demotivating Your Front-Line Employees?

Subscribe here.

ITIL Change Management Risk Assessment

There is always a risk when organizations are implementing changes to their IT systems and infrastructure.

Business leaders and IT team are anxious about that risks because if something goes wrong it may cause technical and financial loss.

This is why risk assessment is an essential component of ITIL change management.

In this blog post, we will explore the process of risk assessment in ITIL change management, including how to identify, evaluate, and mitigate potential risks, as well as the importance of communication and documentation.

Let’s read on

What is ITIL change management risk assessment?

ITIL (Information Technology Infrastructure Library) change management is a process that organizations follow to control and manage changes to their IT systems and infrastructure. The goal of ITIL change management is to minimize the negative impact of changes on business operations, while also ensuring that changes are properly planned, tested, and implemented.

ITIL change management process also includes a risk assessment process to identify and evaluate the potential risks associated with a change. This process helps organizations determine the likelihood and impact of potential risks, and take appropriate actions to mitigate or control those risks.

Why it is important to do risk assessment in ITIL change management?

Before making ITIL change request and going for formal ITIL change approval , assessment of risk are crucial for successful implementation of ITIL change.

By performing a thorough risk assessment before implementing a change, organizations can identify any potential issues and take steps to minimize or eliminate them. This can include developing mitigation strategies, such as creating backups or testing changes in a controlled environment, or implementing control measures, such as additional monitoring or user training.

Furthermore, risk assessment helps organizations prioritize the changes that need to be made based on the level of risk they pose. This enables the organization to focus on the changes that are most critical to the business, while managing the risks associated with them.

Moreover, Risk assessment is an ongoing process and should be regularly reviewed and updated as the organization’s environment and objectives change.

Overall, risk assessment in ITIL change management is critical for ensuring the stability and reliability of an organization’s IT systems, and for minimizing the potential negative impact of changes on business operations.

ITIL Change Management Risk Assessment Process

Risk assessment process involves mainly three steps: Identification of potential risks; evaluating the likelihood and impact of identified risks and prioritization of risks based on likelihood and impact. But here it is also relevant to discuss development of mitigation strategies and their implementation and most importantly how to communicate risks to all stakeholders.

Let’s discuss each of these

1. Identification of potential risks

The identification of potential risks involves identifying and listing all the possible risks that could arise as a result of the proposed change.

There are several methods that can be used to identify potential risks, including:

Brainstorming: A group of individuals with relevant knowledge and experience come together to identify potential risks.

Checklists: Standardized checklists are used to identify potential risks based on past experience or industry best practices.

Root cause analysis: This method looks at the underlying causes of past incidents or problems to identify potential risks.

SWOT analysis: This method looks at the organization’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to identify potential risks.

Impact analysis: This method looks at the potential impact of a change on different areas of the organization, such as operations, security, or compliance, to identify potential risks.

During the identification of potential risks, it is important to consider the different types of risks that may arise, such as technical risks, operational risks, and compliance risks.

It is also important to involve individuals from different departments and with different levels of knowledge and experience in the identification process to ensure that a wide range of potential risks are considered.

2. Evaluating the likelihood and impact of identified risks

Once potential risks are identified, the next step is to evaluate the likelihood and impact of those risks, in order to prioritize them and develop appropriate mitigation and control measures.

This step involves determining the probability of each identified risk occurring, as well as the potential impact on the organization if the risk were to occur.

To evaluate the likelihood of a risk occurring, organizations can use techniques such as:

Probability estimates: Assigning a numerical value to the likelihood of a risk occurring, such as “low”, “medium”, or “high”.

Scenario analysis: Identifying possible scenarios that could lead to the risk occurring and assessing the likelihood of each scenario.

To evaluate the impact of a risk, organizations can consider factors such as:

Financial impact: The potential costs associated with the risk, such as lost revenue or increased expenses.

Operational impact: The potential disruption to business operations, such as service outages or delays.

Compliance impact: The potential impact on compliance with laws, regulations, or industry standards.

Reputational impact: The potential impact on the organization’s reputation or brand.

3. Prioritization of risks based on likelihood and impact

Prioritizing risks based on likelihood involves determining the priority of each identified risk based on the level of risk they pose to the organization.

The most common method of risk prioritization is to create a risk matrix, where the likelihood of a risk occurring is plotted against its potential impact. Risks that fall in the high likelihood and high impact quadrant should be given the highest priority, as they pose the greatest risk to the organization. Risks that fall in the low likelihood and low impact quadrant can be given lower priority.

Another way to prioritize risks is by using a scoring system, where a score is assigned to each risk based on its likelihood and impact. Risks with higher scores would be considered higher priority.

Additionally, organizations can also use other factors such as the urgency of the change and the risk tolerance of the organization to prioritize risks.

4. Development of strategies to mitigate or control identified risks

After identifying and prioritizing potential risks in the ITIL change management process, the next step is to develop strategies to mitigate or control those risks.

Mitigation strategies aim to reduce the likelihood or impact of a risk, while control strategies aim to manage the risk if it does occur.

Here are a few examples of mitigation and control strategies that organizations can use to manage risks:

Creating backups: This can help ensure that data can be restored in the event of a risk occurring.

Testing changes in a controlled environment: This can help identify and resolve any issues before the change is implemented in a production environment.

Implementing redundancy: This can help ensure that critical systems or services can continue to function in the event of a risk occurring.

Implementing additional monitoring: This can help detect and respond to risks more quickly.

Developing incident response plans: This can help organizations respond quickly and effectively to risks that do occur.

Providing user training: This can help ensure that users know how to use systems or services in the event of a change.

The development of mitigation and control strategies should involve individuals from different departments, such as IT, operations, and business, to ensure that a wide range of perspectives and expertise are considered.

Once the strategies are developed, they should be implemented, and regularly reviewed and updated to ensure that they are still effective in managing the risks.

5. Implementation of these strategies

Implementing the strategies is about taking the necessary steps to put the strategies into action and make them operational. This includes:

Assigning responsibilities and tasks: Identifying and assigning the people, departments, or teams responsible for implementing the strategies.

Allocating resources: Identifying and allocating the necessary resources, such as budget and personnel, to implement the strategies.

Developing and communicating procedures: Developing and communicating procedures and guidelines for implementing the strategies, to ensure that they are implemented consistently and correctly.

It’s important to note that the implementation process should be closely coordinated with the change management process, to ensure that the change is implemented correctly and that the strategies are in place before the change is made.

6. Communication of risk assessment findings to relevant stakeholders

Communication of risk assessment ensures that all stakeholders are aware of the risks associated with a change and are able to take appropriate actions to manage those risks.

The communication process typically involves:

Identifying stakeholders: Identifying all stakeholders who may be impacted by the risks associated with the change, including individuals or departments within the organization, as well as external stakeholders such as customers or partners.

Communicating the findings: Communicating the findings of the risk assessment process, including the identified risks, their likelihood and impact, and the control measures that have been implemented to manage those risks.

Providing regular updates : Providing regular updates on the status of the risk management process, including any new risks that have been identified or any changes to the control measures.

Encouraging feedback : Encouraging feedback from stakeholders on the risk assessment process and the control measures implemented, to ensure that the process is effective and that all stakeholders are aware of the risks and the measures taken to manage them.

Communicating the outcome of the change: Communicating the outcome of the change, including any issues that arose, and the actions taken to address them.

Effective communication of risk assessment findings to relevant stakeholders helps build trust and understanding, and allows stakeholders to plan and prepare for potential risks.

Final Words

By performing a thorough risk assessment before implementing a change, organizations can identify bottlenecks and threats to implementation of IT related changes. The findings of risk assessment contribute to developing of mitigation strategies to overcome the potential risks of implementing changes in IT system and infrastructure. Therefore, organizational stability and reliability of its IT system largely depends on how effectively risk assessment is undertaken.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

How to Avoid Common Mistakes in Change Management

Exploring the Types of Crisis Communication

Organisational Restructuring Process

Updated: 19 March 2024 Contributors: Alexandria Iacoviello, Amanda Downie

Change management (CM) is the method by which an organization communicates and implements change. This includes a structured approach to managing people and processes through organizational change.

A change management process helps ensure that employees are equipped and supported for the entirety of the transition. Several reasons constitute a need for change management. Mergers and acquisitions, leadership adjustments and implementation of new technology are common change management drivers. The organizational development needed to compete with rapid digital transformation across the industry leads companies to implement new products and new processes. However, these innovations often disrupt workflows, presenting a need for effective change management.

Successful transformational change goes beyond a communication plan; it involves implementing change throughout the company culture. A change management strategy can help stakeholders to adopt proposed changes more readily than in situations where such a strategy is not employed. By activating employees as change agents by involving them in the workflow, business milestones can be achieved. Leaders can and should establish the benefits of change through developing a comprehensive change management plan.

Find out how HR leaders are leading the way and applying AI to drive HR and talent transformation.

Register for insights on SAP

Change management should be a thought-out, structured plan that remains adaptable to potential improvements. How change leaders choose to approach organizational change management varies in size, need and potential for employee buy-in.

For example, employees who lack change efforts experience may need a more tailored approach, like receiving guidance from human resources (HR). Employees who experience change on an organizational level may serve as good candidates on the change management team, offering insightful support to leadership and fellow employees.

Successful change management is a cumulative result of all the key stakeholders’ success in understanding the change initiatives. This requires proactively engaging and supporting a positive employee experience —invite employees to give constructive feedback and continuously communicate the business process or scope changes.

Psychologists and change leaders have developed several methods of organizational change management:

Developed by change consultant William Bridges (link resides outside ibm.com), this framework focuses on people’s reactions to change. The adjustment of critical stakeholders to change is often compared to the five stages of grief, but instead, the Bridges’ model is described through three stages:

- Endings: The discontinuation of old processes.

- Neutral zone: The uncertainty and confusion as new roles are being identified.

- New beginnings: The acceptance of new ways.

Owned by a joint venture between Capita and the UK Cabinet Office, Axelos developed the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) . The framework uses a detailed guide to manage IT operations and infrastructure. The goal is to drive successful digital transformation through incident-free IT service implementation throughout the change management process.

Over the years, ITIL was improved and expanded upon to enhance the change process. The ITIL framework has four versions, with the latest being ITIL v4. This version prioritizes the implementation of proper DevOps , automation and other essential IT processes. 1 Created to aid in modern-day digital transformation, the Fourth Industrial Revolution prompted ITIL v4.

John Kotter, a Harvard professor, created his process for professionals that are tasked with leading change. 2 He collected the common success factors of numerous change leaders and used them to develop an eight-step process:

- Creating a sense of urgency for change.

- Building a guiding coalition.

- Forming a strategic vision and initiatives.

- Enlisting a volunteer army.

- Enabling action by removing barriers.

- Generating short-term wins.

- Sustaining acceleration.

- Instituting change.

Psychologist Kurt Lewin developed the "unfreeze-change-refreeze" framework during the 1940s. 3 The metaphor implies that the shape of an ice block remains unaltered until it shatters. However, transforming an ice block without breaking it can be done by melting the ice, pouring the water into a new mold and freezing it in the new shape. Lewin drew this comparison for change management strategy, indicating that introducing change in stages can help an organization successfully attain employee buy-in and a smoother change process.

In the late 1970s, McKinsey consultants Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman wrote a book called In Search of Excellence . 4 In that book, a framework was introduced through its ability to map out interrelated factors that can influence the ability of an organization to change. Around 30 years later, this framework became the McKinsey 7-S Framework. The intersection of the elements within the framework differs depending on the culture or institution. Listed in no hierarchical order, those seven elements are:

- Shared values

The Prosci Methodology, developed by the firm Prosci, is based on various studies that examine how people react to change. The methodology comprises three main components: the Prosci Change Triangle (PCT), the ADKAR model and the Prosci 3-Phase Process.

Sponsorship, project management and change management drive the PCT Model framework. This model puts success at the center of these three elements and is used in the overall Prosci Methodology.

ADKAR Model

The ADKAR model addresses one of the most essential change management pieces: the stakeholders. The framework is an acronym that equips change leaders with the right strategies:

- Awareness of the need for change.

- Desire to participate and support the change.

- Knowledge of how to change.