- Our Mission

More Than a Dozen Ways to Build Movement Into Learning

Physical activity that amplifies learning can have a powerful effect on retention and engagement—it’s also fun.

When researchers at Texas A&M University gave standing desks to 34 high school students, they discovered that after consistent use, standing while learning delivered a significant boost to students’ executive functioning skills—the sorts of cognitive skills that allow kids to manage their time, understand and memorize information, and organize thoughts in writing. Even small amounts of movement, this emerging research revealed, can deliver a positive impact on learning: Neurocognitive testing of the standing students, the pilot study notes, showed a 7 to 14 percent improvement in their cognitive performance, a noteworthy impact for such a simple intervention.

Infusing classrooms with physical activity—or at least the option of some movement, at student discretion—isn’t just good for kids’ bodies, it’s also a powerful tool for improving learning and focus and reducing classroom management issues . And yet, from kindergarten through high school “students spend most of their academic lives at a desk,” says educator Brad Johnson for The Washington Post , an arrangement that is meant to increase their focus and academic productivity, but can actually create kids who are “bored, off-task, disruptive or otherwise disengaged.”

There are many smart, innovative ways to build movement into lessons and the research increasingly supports getting kids moving in schools to promote better physical health, provide the types of breaks that reset our cognitive processes so that we can learn anew, and even link our physical bodies to our cognitive insights to encode learning more deeply. From intentionally aligning curriculum with movement to improve retention, to planning frequent and active brain breaks to clear working memory, here are more than a dozen ways educators and researchers are pairing learning with movement.

INTEGRATING MOVEMENT IN THE CURRICULUM

Incorporating gross and fine motor activities across many subject areas makes a lot of sense, particularly to teach foundational concepts. In math classes, for instance, you can create chalk grids on the playground and have children walk sloped lines, stopping to discuss and walk the line’s “rise” and “run,” or you can use hand and arm gestures to teach a broader range of mathematical concepts like tangents and cosines. Here are a few more ways educators are injecting movement into lessons.

In Science, Becoming a Liquid: Science teacher and instructional coach JaShan Wilson turned social distancing requirements into an opportunity for her students to “use their own bodies to model movements, test phenomena, and engage with the curriculum.”

For lessons on matter and particle movement, for example, she asks students to “act like solids, liquids, or gases,” and then “switch it up as in Simon Says until all students sped up, slowed down, or vibrated in order to represent how matter moves.” For a unit on energy, Wilson’s students examine the transfer of energy by making wave movements with their arms. “The more energy they apply, the higher the amplitude,” Wilson notes. Engaging students in these “human labs,” as Wilson calls them, delivered impressive academic results: Her students did better on formative assessments and “continued to utilize the movements and reference the activities, which showed how they connected the concepts to them permanently.”

Playing Basketball Math: In a six-week study involving 757 Copenhagen elementary school students, researchers had half the students do math while playing basketball. The other half studied math in class as usual, and played basketball solely as a regular gym activity.

The kids who played while doing math did tasks like “counting how many times they could sink a basket from three meters away versus at a one-meter distance,” and then added up the numbers, says Linn Damsgaard , one of the study’s authors. Among the students who played basketball while doing math, the researchers reported a 6 percent boost in math mastery; a 16 percent increase in intrinsic motivation; and a 14 percent improvement in “perceived autonomy,” or self-determination, compared to peers learning in the classroom.

Student Thespians: When researchers asked 8-year-olds to mimic the words they were learning in another language by using their hands and bodies to act out the word’s meaning—by spreading their arms and pretending to fly while they learned the German word for airplane, for example—the students were 73 percent more likely to recall them , even two months later.

In ELA and social study classes, having kids partake in skits may feel like it’s inviting chaos, but the body will often remember what the mind forgets—and getting students to act out historical events or scenes from works of literature can help them remember the information, grasp the basic elements of drama, or provide them with a new opportunity to listen to the sounds and rhythms of written and spoken language.

Drawing It Out: Even indifferent or unpracticed artists benefit by drawing what they’ve learned, a 2018 study concluded, resulting in retention rates that were double the rates of when kids wrote or read.

When a student draws a concept, they “must elaborate on its meaning and semantic features,” the researchers explain, while engaging “in the actual hand movements needed for drawing”—a rich mixture of cognitive and physiological activities that encodes learning more deeply and is a “reliable, replicable means of boosting performance.”

The drawing doesn’t have to be expert-level: even stick figures or crude shapes accompanied by annotations will do, and data visualizations work similarly to hand-drawn pictures. You can assess learning by allowing kids to try one-pagers that demonstrate their understanding of a topic through art; incorporate more graphs and statistical modeling into math and science classes; have students draw models of solar systems or cells in science classes; or let students create travel journals to document any learning journey graphically.

ACTIVE BRAIN BREAKS

Research shows that when students take brief, active breaks throughout the day, it increases productivity, creativity, and social skills . “When we take a brain break, it refreshes our thinking and helps us discover another solution to a problem or see a situation through a different lens,” writes Lori Desautels , an assistant professor at the Butler University College of Education. “The brain break actually helps to incubate and process new information,” says Desautels.

So plan for frequent breaks (we’ve included a few ideas to get you started) and keep them active and social—a brisk walk around the perimeter of the classroom, a quick stretch, an energizing freeze dance.

Brain breaks for younger students: Try wiggle breaks where kids stand and wiggle each arm and leg in succession or opposite sides , where kids blink one eye while snapping fingers on the opposite side and then reverse the exercise. For energizing breath , have students pant like dogs with their mouths open and tongues out for 30 seconds, hands on the belly, then breathe briskly for another 30 seconds with mouths closed. Easier still: invite kids to jump in place like they’re on a trampoline; or keep it really simple with a quick crab walk around the room.

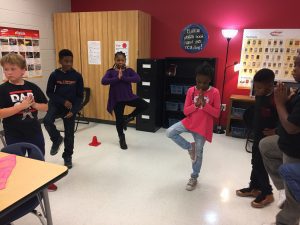

Brain breaks for older students: Try a wave , starting at one end of the room with students standing and raising their arms; or have them get out of their chairs for a whole-body stretch or for a brief walk around the room. They can also pass a ball around for a quick game of catch, practice a few yoga poses like tree pose or warrior II, or very simply, ask them to hop on one foot , then switch to the other foot for a minute or two.

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT MOVEMENT WHILE LEARNING

Doodling, Fidgeting, and More: There’s often confusion about movement that is not directly related to learning. While drawing a plant cell or creating a pictorial representation of a scene from a novel will deepen retention and result in more durable learning , when students doodle during lessons—by drawing elaborate cartoons while an unrelated lesson is in progress, for example—the research, and the cognitive science, suggests that learning is compromised .

In a 2019 study during which students were asked to doodle—which the researchers defined as “drawing that is semantically unrelated to to-be-remembered information”—while they learned, they showed “poorer free recall for words encoded while free-form doodling compared to words that were drawn or written.”

Multitasking divides our attention , a finite cognitive resource, and makes us less proficient at both tasks. But there’s a wrinkle here, too: There is some evidence that activities that require very little attention, like fidgeting or listening to soft background music (but probably not loud or attention-gobbling music), don’t divide our focus to the same degree. Being tolerant of a certain amount of fidgeting or a pair of headphones is an important accommodation for students who might otherwise need to get out of their seats entirely, or might struggle with focused, demanding tasks like homework. In the end, the more distracting any task is to the lesson, the less likely learning is to stick.

- Browse By Category

- View ALL Lessons

- Submit Your Idea

- Shop Lesson Books

- Search our Lessons

- Browse All Assessments

- New Assessments

- Paper & Pencil Assessments

- Alternative Assessments

- Student Assessments

- View Kids Work

- Submit Your Ideas

- Browse All Best Practices

- New Best Practices

- How BPs Work

- Most Popular

- Alphabetical

- Submit Your Best Practice

- Browse All Prof. Dev.

- Online PD Courses

- Onsite Workshops

- Hall of Shame

- Becoming a PE Teacher

- PE Articles

- Defending PE

- Substitute Guidelines

- Online Classes

- PE Research

- Browse All Boards

- Board of the Week

- Submit Your Bulletin Board

- Browse All Class Mngt

- Lesson Ideas

- New Teacher Tips

- Reducing Off-Task Behavior

- Browse All Videos

- Find Grants

- Kids Quote of the Week

- Weekly Activities

- Advertise on PEC

- FREE Newsletter

PE Central has partnered with S&S Discount Sports to provide a full range of sports and PE products for your program.

Get Free Shipping plus 15% OFF on orders over $59! Use offer code B4260. Shop Now!

- Shop Online Courses:

- Classroom Management

- Integrating Literacy & Math

- Grad Credit

- All PE Courses

- Cooperative Fitness Challenge

- Cooperative Skills Challenge

- Log It (Activity Tracker)

- Instant Activities

- Grades 9-12

- Dance of the Month

- Special Events Menu

- Cues/Performance Tips

- College Lessons

- Search All Lessons

- Paper & Pencil Assessments

- Shop Assessment

- How BP's Work

- Shop Bulletin Board Books

- Apps for PE Main Menu

- Submit Your App

- Ask our App Expert

- Active Gaming

- What is Adapted PE

- Ask Our Expert

- Adapting Activities

- IEP Information

- Adapted Web Sites

- Shop Adapted Store

- PreK Lesson Ideas

- PreK Videos

- Homemade PreK PE Equip

- Shop PreK Books

- Shop Class Mngt Products

- Search Jobs

- Interview Questions

- Interview Tips

- Portfolio Development

- Becoming PE Teacher

- Fundraising/Grants

- New Products

- T-Shirts/Accessories

- Class Management

- Middle School

- High School

- Curriculums

- Limited Space

- Search Our Lessons

New Online Courses

- Among Us Fitness Challenge

- Mystery Exercise Box

- The ABC's of Yoga

- Fun Reaction Light Workout

- Virtual Hopscotch

- Red Light, Green Light

- My Name Fitness Challenge

- Holiday Lessons

- Fitness Challenge Calendars

- Field Day Headquarters

- Field Day Online Course

- Star Wars FD

- Power Rangers Field Day

- Superhero FD

- SUPER "FIELD DAY" WORLD

- Nickelodeon FD

- What's New on PEC

- Halloween Station Cards

- Halloween Locomotors

- Thriller Halloween Dance

- Halloween Safety Tips Board

- Spooktacular Diet Board

- Halloween Nutritional Board

- Chicken Dance Drum Fitness

- Mission "Possible" Fitness

- Setting Goals - Fitnessgram

- Muscular Endurance Homework

- Poster Contest-Good Fitness

- Musical Fitness Dots

- FALLing for Fitness

- Fitness Routines

- Free PE Homework Lessons

- K-4 Report Card

- K-2 Progress Report

- Central Cass MS Report Card

- MS Evaluation Tool

- Activity Evaluation Tool

- SLO and Smart Goal Examples

- No Quacks About It-You Can Assess

- Super 6 Fitness Stations

- Throwing at the Moving Ducks

- Basketball Station Team Challenge

- Tennis Stations

- Olympic Volleyball Skills

- Fitness Stations Self Assessment

- Peer Assessment Fitness Checklist

- Where s the Turkey Fitness Game

- Thanksgiving PE Board Game

- Turkey Bowl

- Thanksgiving Extravaganza!

- Twas the Night Before Thanksgiving

- Team Turkey Hunt

- Thanksgiving Healthy Food & Locomotors

- View Spring Schedule

- Curriculum Development in PE

- Assessment in PE

- Methods of Teaching Elem PE

- Methods of Teaching Adapted PE

- Using Technology in PE

- History of PE

- View Self-Paced Courses

- PE for Kids with Severe Disabilities

- Add Int'l Flair to Your Program

- Teaching Yoga in PE

- Classroom Management Tips

- Social & Emotional Learning in PE

- Large Group Games in PE

- Teaching PE In Limited Space

- My Favorite Apps in PE

- See All Courses

- PE Homework Ideas

- Home Activity Visual Packet

- Home Fitness Games

- Activity Calendars

- 10 At Home Learning Activities

- Distance Learning Google Drive

- Log It Activity Log

- Hair UP! Dance

- Jumping Jack Mania Dance

- Shaking it to "Uptown Funk"

- Dynamite Line Dance Routine

- Core Strength w Rhythm Sticks

- Dancing with the Skeletal System

- Team Building and Rhythms Dance

- Back to School Apple Board

- How I Exercised Over the Summer

- Picture Yourself Participating in PE

- Thumbs Up for Learning PE

- Welcome to PE

- Let's Get Moving

- What Makes You a Star

- Do Not Stop Trying!

- Fall Team Buildiing Field Day

- Better When I'm Dancin'

- Locomotor Scavenger Hunt

- Follow My Lead IA

- Pass, Dribble, "D"

- Fitness Concepts Assessment

- Silvia Family Hometown Hero's BB

- See All New Ideas

- Project Based Learning in PE

- Flipped Teaching in PE

- Assessment Strategies

- Technology in PE

- Fitness and FitnessGram

- Curriculum Planning/Mapping

- Call to Book - 678-764-2536

- End of Year PE Poem

- Just Taught My Last Class Blog

- We've Grown so Much Board

- Time Flies Board

- Hanging Out This Summer Board

- How will YOU be ACTIVE? Board

- Staying Active Over Summer Board

- St. Patrick's Day Circuit

- Catch The Leprechaun

- Leprechaun Treasure Hunt

- Irish Jig Tag

- Celebrating St. Patty\92s Day Dance

- LUCKY to have PE Board

- Eat Green for Health Board

- Activity Skills Assessment

- Smart Goal Example

- Understanding Fitness Components

- Cooperation Assessment

- Line Dance Peer Evaluation

- View All Assessments

- Detective Valentine

- Valentine Volley

- Valentine's For the Heart

- Valentine Rescue

- 100 Ways Heart Healthy Board

- Make a Healthy Heart Your Valentine

- Don't Overlook Your Health

- Star Wars Dance Lesson

- Merry Fitmas Bulletin Board

- Welcome to PE Bulletin Board

- Gymnastics Skills Bulletin Board

- Don't Let Being Healthy Puzzle You

- It's Snow Easy to be Active

- Exercise Makes You Bright

- Basketball Lesson

- Bottle Cap Basketball

- Skills Card Warm Up

- Building Dribblers

- Feed the Frogs

- Rings of Fire Dribbling

- All basketball ideas on PEC

- Fall Into Fitness Board

- Turkeys in Training

- Gobbling Up Healthy Snacks

- Gobble If You Love PE

- Don't Gobble 'Til You Wobble

- Hickory Elem is Thankful

- Mr. Gobble Says

- Fall & Rise of PE Part 1

- Fall & Rise of PE Part 2

- PE Teachers Making a Difference

- Leading Enthusiastic Student Groups

- Using Twitter for PE PD

- Two Person Parachute Activity

- Pool Noodle Lessons in PE

- Basketball Shooting Stations

- Thanksgiving Stations

- Sobriety Testing Stations

- Seuss-Perb Stations

- Cooperative Skills Stations

- Cooperative Fitness Stations

Help for HPE at Home Download Free

Pe central online courses learn more, shop the p.e. & sports flash sale now shop now.

Call Sandy ( 800-243-9232 , ext. 2361) at S&S Worldwide for a great equipment deal!

What's New | Search PEC | Teaching Articles | Hall of Shame | Kids Quotes | Shop S&S

What's New Lesson Ideas Newsletter Site Updated: 6-11-15

Great PE Ideas! Superstars of PE

PE Job Center (Job Openings, Sample Interview Questions, Portfolio Guidelines

Inspirational Video! Cerebral Palsy Run--Matt Woodrum Cheered on by PE Teacher, Family and Classmates

New Blog! Physical Educators \96 You Are Making a Difference!

Physical Education teachers are truly amazing! I have believed this ever since I become one back in 1986 and I was reminded of how truly special they are the other day while reviewing 236 responses to a survey that S&S conducted on PE Central. Question number 21 of the survey reads, \93What gets you most excited about your physical education job?\94 Continue to read full blog post

Use LOG IT To Keep Kids Active Over the Summer

We have searched our site and found some fun things to encourage your kids to become physically active over the summer. Check out some of our cool summer bulletin boards and for a great professional development conference we highly recommend the National PE Institute July 27-29 in Asheville, NC.

- LOG IT --walk virtually around the USA. Sign your kids up before they leave school!

- Log It is a Step Towards Fitness (Education World Article)

Best Practices:

- Leadership and Summer Fitness through "Charity Miles"

Bulletin Boards:

- Countdown to Summer

- Hanging Out This Summer

- Summer Plans

New! Dancing with Math Dance Idea of the Month | More New Ideas

FREE Top 10 Field Day Activities eBook Enter $2,500 Giveaway Contest for a chance to win the "Field Day of Your Dreams!" 25% off Field Day equipment! Offer code E4213. (Expires 4/30/15)

Field Day just got easier! We have worked with our partner S&S Discount Sports to come up with the ultimate "Top 10 Field Day Activities" FREE eBook . You can enter their $2,500 Giveaway contest for a chance to win the "Field Day of Your Dreams!" Check it out!

Congrats to Nicki Newman Case and her Student!

Last week, physical education teacher Nicki Newman Case, got her Kids Quote of the Week published. She sent us the picture (below) of the young man who was responsible for the quote! By getting the quote published on PE Central, she has earned a $50 eGift card from our sponsor, S&S Worldwide! Here is her Facebook post on PEC. Thanks for sharing Nicki and congrats to both of you!

Nicki Newman Case, PEC Facebook Post " I wanted to thank PE Central for sending me an email that said I won $50 for a published kid quote. I am going to let the kid who wrote the Valentine help me pick out what he wants from the S&S catalog to use in our gym. I am also going to buy him the "I got Published" t-shirt. THANK YOU! I presented the winner of the Kids Quote of the Week with his T-shirt this morning at assembly! He LOVED it! "

Take the PE Central Survey! Complete and enter to win a $250 S&S Worldwide eGift Card

Stay Connected with PE Central Join the PE Central Facebook Page | Follow PE Central on Twitter

New Dances Waltzing Line Dance (with video) Shake It Senora Dance (with video) McDowell County, WV Happy Dance

Holiday Bulletin Boards | Holiday Lesson Ideas | What's New on PEC

New! Unedited Full Length Video Lessons

New! Valentine's Day Physical Education T-Shirts Order them now! They are awesome!

Share the Cooperative Fitness Challenges! 6 Free Fitness Station Activities

Dance Lesson Ideas of the Month!

Enter for a Chance to Win $100!

Are you teaching The First Tee National School Program in your school? What's working at your school? Send in your best practices and lesson plan ideas for the National School Program. Your roles as physical educators and leaders is vitally important to making a difference in a child\92s life. That\92s why we want to do our part in supporting you and share the great work you are doing. Click here to learn more

Want to bring The First Tee National School Program to your elementary school? To learn more go here

New! Physical Education Report Cards New! Pink PE Women's V-Neck Tee Register for the Cooperative Fitness and Skill Challenges

Featured Article: Using PE Central's \91LOG IT\92 as a Step Toward Fitness (Great way to track summer physical activity-- Log It )

New Teaching Videos Content is King: High School Circuits Lesson Highlights (9-12) Content is King: Food Pond Common Core Lesson Highlights (4th) Content is King: 4 x 4 fitness Lesson Highlights (5th) Basketball Dribbling Full Elementary Lesson

Featured Product! Elements of Dance Poster Set Workbook, Flashcard Set, Value Pack

61 Essential Apps for PE Teachers Book

20% Off Adapted PE Products

Featured Holiday Bulletin Boards

New Boards | View All Boards | Board of the Week | Submit a Board

School Funding Center Find grants for your school and program!

Featured Halloween Bulletin Board Don't Let Fitness Testing Spook You!

New Product Section: eBooks (PDF Downloads) Adapted PE Desk Reference eBook

NEW! Dance Lesson Idea of the Month: Team Building and Rhythms Dance (w/ Video)

Submit Your Ideas Now Published Ideas Earn a $50.00 eGift Card from S&S Worldwide

Sale! Save 20% on Most of Our Products! $3.00 Flat Rate Shipping Rate on ALL Orders

New eBOOKS! TEPE Books: Fitness, PreK, Assessment, PE Homework

Great Back to School Lesson Idea and Product! Behavior Self Check Lesson Idea and Poster Set

This Class Management Lesson idea, featuring 3 vinyl posters should help physical educators when students get a little bit off-task. View the entire lesson idea . Purchase Poster Set

Featured Classroom Management Lesson Idea: Behavior Self-Check Lesson (w/posters)

Check Out Our PE T-shirts

Happy thanksgiving.

Featured Thanksgiving Bulletin Boards

Featured Bulletin Boards ( View All Boards )

PE Central Copyright 1996-2020 All Rights Reserved

PE Central 2516 Blossom Trl W Blacksburg, VA 24060 E-mail : [email protected] Phone : 540-953-1043 Fax : 540-301-0112

Copyright 1996-2016 PE Central® www.pecentral.org All Rights Reserved Web Debut : 08/26/1996

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter and receive

physical education lesson ideas, assessment tips and more!

Your browser does not support iframes.

No thanks, I don't need to stay current on what works in physical education.

We envision a world where every mind, every body, every young person is healthy and ready to succeed

We’re ensuring that all young people have the chance to live healthier lives

To date, our work has impacted over 31 million young people

We work with schools, youth-serving organizations, and businesses to build healthier communities that support healthy kids

Focus Areas

Our evidence-based program empowers schools to create healthier learning environments for students and staff

- Out-of-School Time

Our best practices framework offers guidance for healthy student engagement during out-of-school time

The Walking Classroom

Our innovative program supports health and learning with educational podcasts students listen to while they walk

School Policies

We inform school policies to ensure children’s environments support and promote good health

In your state

See all states, other areas of focus.

- Juvenile Justice

Business Sector

For schools, districts, & ost, visit the action center.

Take an assessment, create an action plan, and discover tools to create healthier school and out-of-school time environments.

Access resources and support to create and sustain a healthy school, district, or out-of-school time site.

Products & Services

Learn about our suite of customizable tools, capacity building resources, and professional development opportunities.

For Families & Caregivers

Get healthy at home.

Resource collections that help families prioritize healthy living and create home environments where everyone can thrive.

- Eating Healthy

- Moving More

- Feeling Healthy

- Prioritizing Routine Immunizations

- Nourishing Families with Del Monte Foods

- Celebrating Health

- For Educators & Health Champions

Other Ways to Make a Difference

Make a tax-deductible donation to give more kids a healthy future.

America’s Healthiest Schools

- Learn More about our Recognition Program

- Get the 2024 Award Guide

- View the 2023 List of America’s Healthiest Schools

All Resources

Start browsing our entire resource library

Most Popular

Explore our most popular tools and resources

- Smart Snacks Calculator

- Fitness Breaks

- Physical Activity Break Cards

- Employee Wellness Staff Survey

- Nature-Based BINGO

- Harmony at Home Toolkit

- Healthy at Home Toolkit

Discover resources to support your unique needs

- Staff Well-Being

- Family Engagement

- Health Education

- Nutrition Services

- Physical Activity

- Physical Education

- Smart Snacks

- Social & Emotional Health

- Tobacco & Vaping Prevention

Become an expert in your favorite subjects

- Running Start: First Steps to Creating Healthier Environments

- QPE for All: Best Practices in Physical Education

- But, It’s Just a Cupcake

- Walk the Talk - Modeling Healthy Behaviors

- Before, During and After School Physical Activity

- WSCC’ing up Well-Being

- Classroom Physical Activity

Movement in the classroom has been shown to boost students' daily minutes of physical activity and support academic learning through improved behavior and focus.

Healthier Generation can show you how to integrate activity in the classroom, in a way that supports learning.

Get started implementing classroom physical activity breaks using our Physical Activity Task Cards or Fitness Trail Station Cards that you can print and use anytime throughout the school day. And don’t miss our Fitness Break Videos , which are sure to get students out of their seats and moving.

Need ideas for integrating movement with content? Try NC Energizers and Active Academics .

Next Step: learn how students can benefit from physical activity during out-of-school time !

- Physical Activity during Out-of-School Time

Join the Movement

Everyone can support healthy futures. Find the role that’s right for you!

Take Action Today

Stay up to Date

Get the latest Healthier Generation news and healthy resources delivered to your inbox

- In Your State

- Take Action

- In a School

- In an Out-of-School Time Setting

- Collaborate

- Resource Library

- AFHK RESOURCE LIBRARY

Classroom Physical Activity Breaks

Take Action

Schools and teachers looking to integrate physical activity both in and out of the classroom should start with a few initial steps and considerations before implementing a new or enhancing an existing program.

- Engage and leverage your school health team to identify key opportunities for student physical activity as well as any significant barriers to successful implementation.

- Understand your local school wellness policy and how it supports or enhances opportunities for brain breaks and classroom energizers.

- Develop your elevator pitch to describe to your different audiences why physical activity is important and how it links to academic achievement as well as other positive outcomes.

- Get your principal’s approval! A supportive principal is essential to your efforts.

- Make this activity inclusive for all abilities:

- Empower students to suggest and choose which activities, games and movements they find enjoyable and accessible.

- Get to know your students and find out about their abilities, limitations, and interests. Encourage them to be a part of the learning and lesson planning process.

- Demonstrate modifications of simple and complex movement skills such as jumping jacks, squats, and push-ups. For example, show students a wall push-up, a kneeling push-up, and a full push-up. Give students the opportunity to choose which option is best.

- Adapt the game or activity rules. Some simple suggestions include reducing the number of players on a team, modifying the activity area, eliminating time limits, and lowering or enlarging targets or goals.

- Try creative or team-building games where success is only possible when the whole group works together.

- Integrate various types and sizes of equipment such as tactile balls, juggling scarves, numbered spot markers, and foam noodles.

- Vary body parts used, the speed of movement, and number of repetitions to adjust for mobility limitations or low fitness students.

- Mobility adaptations: Some activities may be done from a seated position allowing mobility challenged students to participate with peers or doing similar motions with hands/arms as others are doing with feet legs.

- Sensory adaptations: Students with deafness, speech, self-management or cognitive problems may be able to participate fully in a follow the leader manner. These are very short periods of activity and done in groups of fewer than thirty so students are able to keep up to peers.

Social Emotional Health Highlights

Activities such as these help students explore…

Self-Management: Classroom Physical Activity breaks provide the perfect opportunity for students and teachers to organize their thoughts to better manage stress and control impulses. Release the wiggles with a dance or two and give students are an opportunity to check-in with their emotions and get motivated to continue working towards their goals.

Responsible Decision Making: Taking a classroom activity break can be a great way to redirect attention and antsy behavior to a fun, interactive activity or game. Sometimes all children need is a short opportunity to analyze the current situation, reflect, and responsibly choose their next action. Physical Activity breaks in the classroom provide students an opportunity to practice these skills while increasing to energize the brain.

Participate with your students in the activity. Students will be more likely to join in and have fun if they see their school community moving with them.

Keep physical activity breaks short and manageable. Shoot for 1 – 5 minute breaks at least 2-3 times per day.

Ask teachers and school administrators to share and demonstrate their favorite activities, games, and movement ideas during staff meetings throughout the school year.

Create a classroom atmosphere that embraces movement! Consider playing age and culturally appropriate music.

Integrate physical activity into academic concepts when possible.

Encourage your physical education teacher to be a movement leader and advocate.

Empower students by asking them to share and lead their own physical activity break ideas.

Add in fun equipment items such as beanbags, spot markers, yoga mats, and balance boards. Consider applying for a Game On grant !

Add physical activity breaks right into your daily schedule. Try creating a classroom physical activity calendar of events that includes a variety of ideas throughout the month. Use a classroom physical activity tracker to help your students reach 10 minutes daily!

Ask a parent volunteer create a playlist of music that complements planned movement breaks.

Ask parents to create movement break activity cards and props for teachers to use.

For more activities and ideas like this one, be sure to sign up for our news and updates . And if you like what you see, please donate to support our work creating more ways to help build a healthier future for kids.

Additional Resources

Categories: Physical Activity & Play , At School , Digital Resource

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Free end-of-year letter templates to your students 📝!

46 Unique Phys Ed Games Your Students Will Love

Get your steps in!

There’s nothing kids need more to break up a day spent sitting still and listening than a fun PE class to let off some steam. In the old days, going to gym class probably included playing kickball or dodgeball after running a few laps. Since then, there have been countless reinventions of and variations on old classics as well as completely new games. Although there is no shortage of options, we love that the supplies required remain relatively minimal. You can transport to another galaxy using just a pool noodle or two or create a life-size game of Connect 4 using just Hula-Hoops. You’ll want to make sure to have some staples on hand like balls, beanbags, and parachutes. There are even PE games for kindergartners based on beloved children’s TV shows and party games. Regardless of your students’ athletic abilities, there is something for everyone on our list of elementary PE games!

1. Tic-Tac-Toe Relay

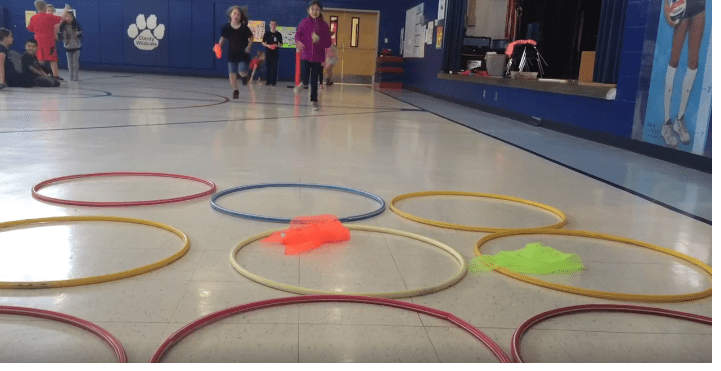

Elementary PE games that not only get students moving but also get them thinking are our favorites. Grab some Hula-Hoops and a few scarves or beanbags and get ready to watch the fun!

Learn more: Tic-Tac-Toe Relay at S&S Blog

2. Blob Tag

Pick two students to start as the Blob, then as they tag other kids, they will become part of the Blob. Be sure to demonstrate safe tagging, stressing the importance of soft touches.

Learn more: Blob Tag at Playworks

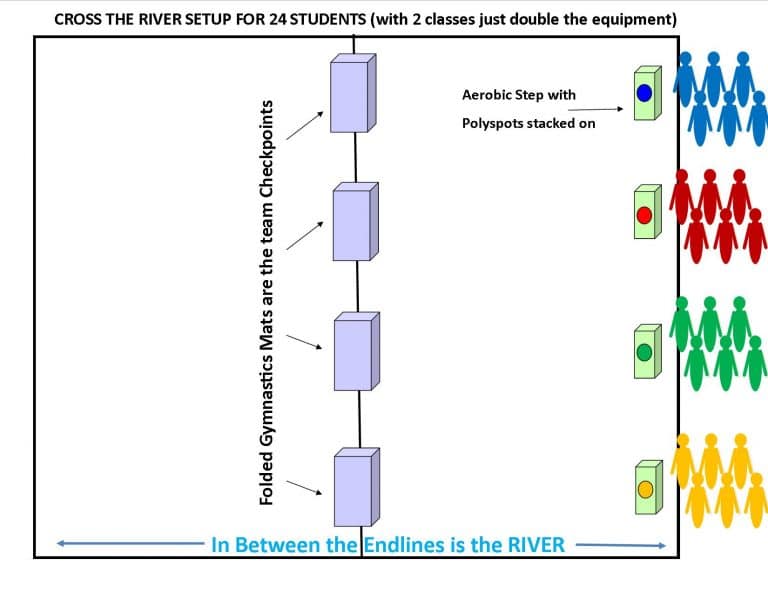

3. Cross the River

This fun game has multiple levels that students have to work through, including “get to the island,” “cross the river,” and “you lost a rock.”

Learn more: Cross the River at The PE Specialist

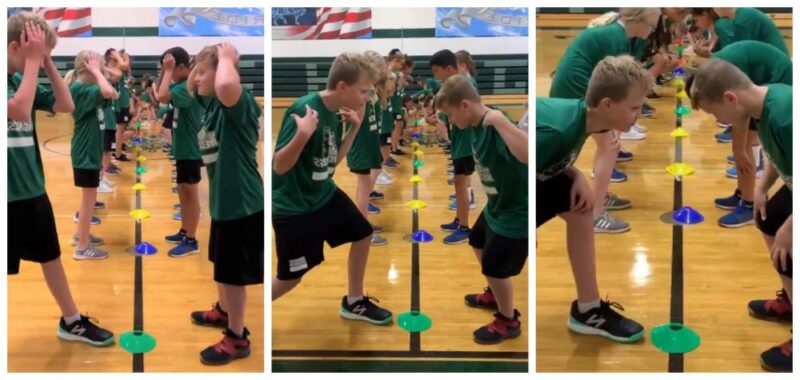

4. Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Cones

Line up cones, then have students pair up and stand on either side of a cone. Finally, call out head, shoulders, knees, or cones. If cones is called, students have to race to be the first to pick up their cone before their opponent.

Learn more: Head, Shoulders, Knees & Cones at S&S Blog

5. Spider Ball

Elementary PE games are often variations of dodgeball like this one. One or two players start with the ball and attempt to hit all of the runners as they run across the gym or field. If a player is hit, they can then join in and become a spider themselves.

Learn more: Spider Ball Game at Kid Activities

6. Crab Soccer

We love elementary PE games that require students to act like animals (and we think they will too). Similar to regular soccer, but students will need to play on all fours while maintaining a crab-like position.

Learn more: Crab Soccer at Playworks

7. Halloween Tag

This is the perfect PE game to play in October. It’s similar to tag, but there are witches, wizards, and blobs with no bones!

Learn more: Halloween Tag at The Physical Educator

8. Crazy Caterpillars

We love that this game is not only fun but also works on students’ hand-eye coordination. Students will have fun pushing their balls around the gym with pool noodles while building their caterpillars.

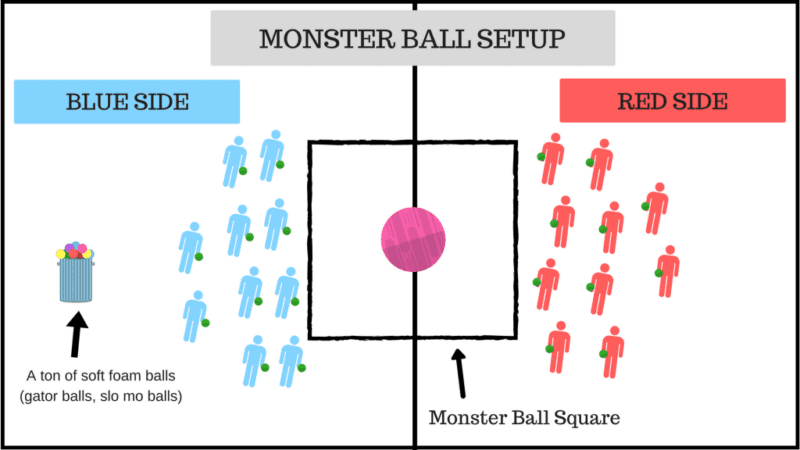

9. Monster Ball

You’ll need a large exercise ball or something similar to act as the monster ball in the middle. Make a square around the monster ball, divide the class into teams on either side of the square, then task the teams with throwing small balls at the monster ball to move it into the other team’s area.

Learn more: Monster Ball at The PE Specialist

10. Striker Ball

Striker ball is an enjoyable game that will keep your students entertained while working on reaction time and strategic planning. We love that there is limited setup required before playing.

Learn more: Striker Ball at S&S Blog

11. Parachute Tug-of-War

What list of elementary PE games would be complete without some parachute fun? So simple yet so fun, all you will need is a large parachute and enough students to create two teams. Have students stand on opposite sides of the parachute, then let them compete to see which side comes out on top.

Learn more: Parachute Tug-of-War at Mom Junction

12. Fleas Off the Parachute

Another fun parachute game where one team needs to try to keep the balls (fleas) on the parachute and the other tries to get them off.

Learn more: Fleas Off the Parachute at Mom Junction

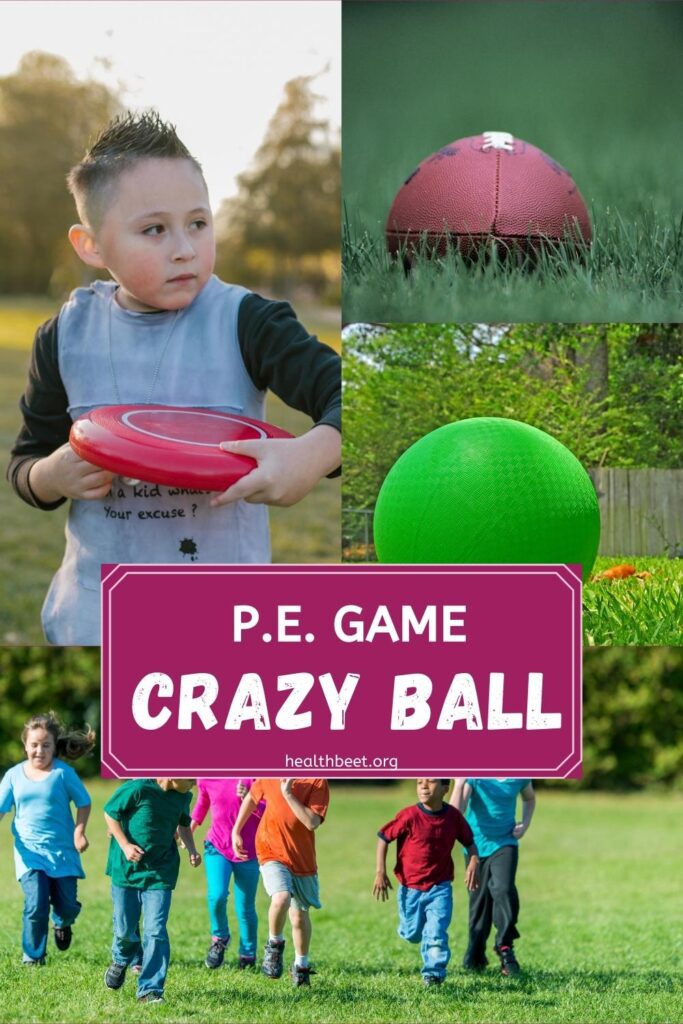

13. Crazy Ball

The setup for this fun game is similar to kickball, with three bases and a home base. Crazy ball really is so crazy as it combines elements of football, Frisbee, and kickball!

Learn more: Crazy Ball at Health Beet

14. Bridge Tag

This game starts as simple tag but evolves into something more fun once the tagging begins. Once tagged, kids must form a bridge with their body and they can’t be freed until someone crawls through.

Learn more: Bridge Tag at Great Camp Games

15. Star Wars Tag

Elementary PE games that allow you to be your favorite movie character are just way too much fun! You will need two different-colored pool noodles to stand in for lightsabers. The tagger will have one color pool noodle that they use to tag students while the healer will have the other color that they will use to free their friends.

Learn more: Star Wars Tag at Great Camp Games

16. Rob the Nest

Create an obstacle course that leads to a nest of eggs (balls) and then divide the students into teams. They will have to race relay-style through the obstacles to retrieve eggs and bring them back to their team.

17. Four Corners

We love this classic game since it engages students physically while also working on color recognition for younger students. Have your students stand on a corner, then close their eyes and call out a color. Students standing on that color earn a point.

Learn more: Four Corners at The Many Little Joys

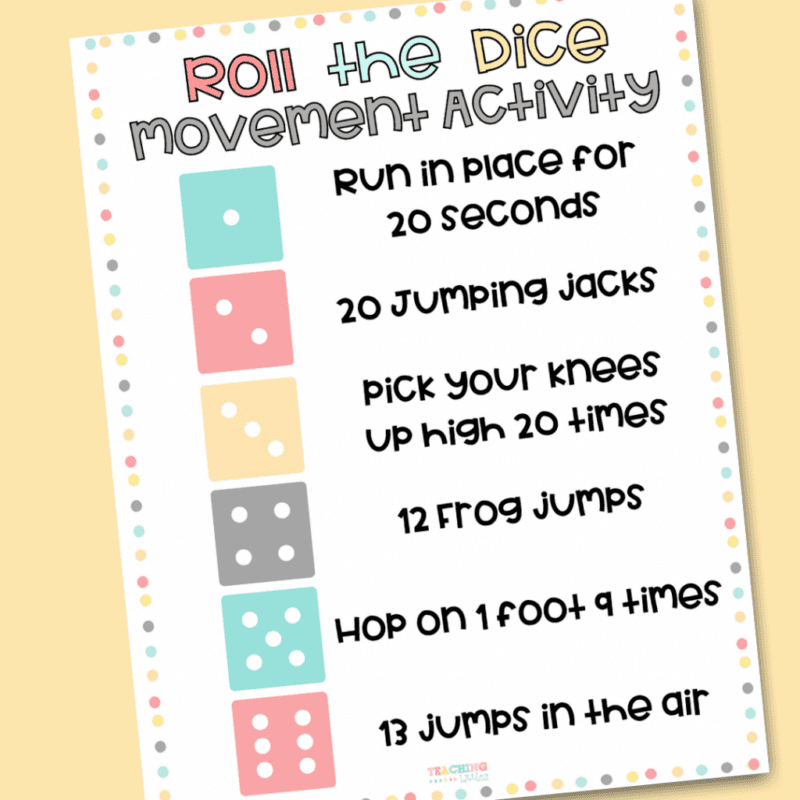

18. Movement Dice

This is a perfect warm-up that requires only a die and a sheet with corresponding exercises.

Learn more: Roll the Dice Movement Break at Teaching Littles

19. Rock, Paper, Scissors Tag

A fun spin on tag, children will tag one another and then play a quick game of Rock, Paper, Scissors to determine who has to sit and who gets to continue playing.

Learn more: Rock, Paper, Scissors Tag at Grade Onederful

20. Cornhole Cardio

This one is so fun but can be a little bit confusing, so be sure to leave plenty of time for instruction. Kids will be divided into teams before proceeding through a fun house that includes cornhole, running laps, and stacking cups.

Learn more: Cardio Cornhole at S&S Blog

21. Connect 4 Relay

This relay takes the game Connect 4 to a whole new level. Players must connect four dots either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.

22. Zookeepers

Students will love imitating their favorite animals while playing this fun variation of Four Corners where the taggers are the zookeepers.

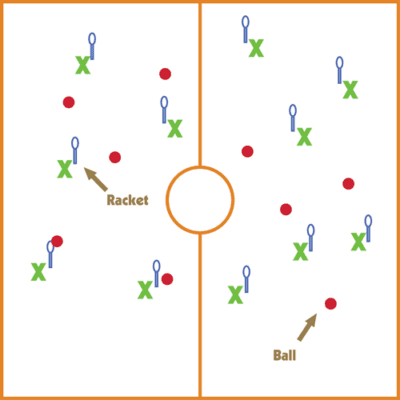

23. Racket Whack-It

Students stand with rackets in hand while balls are thrown at them—they must either dodge the balls or swat them away.

Learn more: Racket Whack-It via PEgames.org

24. Crazy Moves

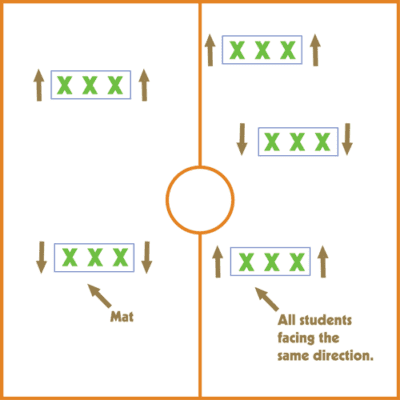

Set mats out around the gym, then yell out a number. Students must race to the mat before it is already filled with the correct number of bodies.

Learn more: Crazy Moves at PEgames.org

25. Wheelbarrow Race

Sometimes the best elementary PE games are the simplest. An oldie but a goodie, wheelbarrow races require no equipment and are guaranteed to be a hit with your students.

Learn more: Wheelbarrow Race at wikiHow

26. Live-Action Pac-Man

Fans of retro video games like Pac-Man will get a kick out of this live-action version where students get to act out the characters.

27. Spaceship Tag

Give each of your students a Hula-Hoop (spaceship), then have them run around trying not to bump into anyone else’s spaceship or get tagged by the teacher (alien). Once your students get really good at it, you can add different levels of complexity.

28. Rock, Paper, Scissors Beanbag Balance

We love this spin on Rock, Paper, Scissors because it works on balance and coordination. Students walk around the gym until they find an opponent, then the winner collects a beanbag, which they must balance on their head!

Learn more: Rock, Paper, Scissors Beanbag Balance at PE Universe

29. Throwing, Catching, and Rolling

This is a fun activity but it will require a lot of preparation, including asking the school maintenance staff to collect industrial-sized paper towel rolls. We love this activity because it reminds us of the old-school arcade game Skee-Ball!

Learn more: Winter Activity at S&S Blog

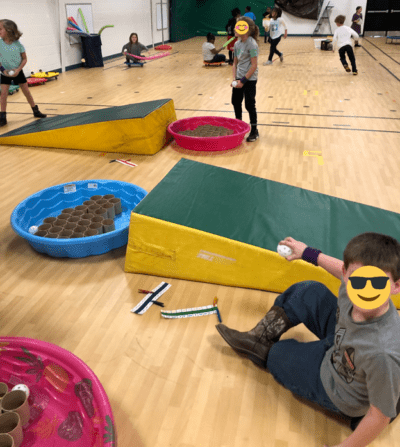

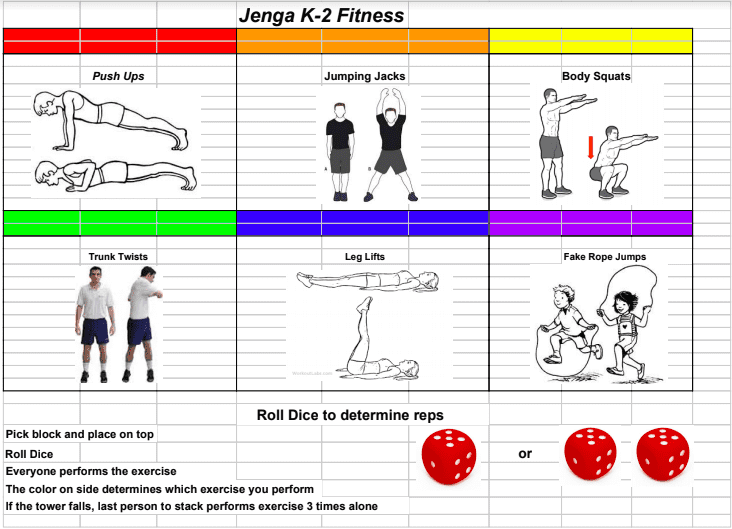

30. Jenga Fitness

Although Jenga is fun enough on its own, combining it with fun physical challenges is sure to be a winner with young students.

Learn more: Jenga Fitness at S&S Blog

31. Volcanoes and Ice Cream Cones

Divide the class into two teams, then assign one team as volcanoes and the other as ice cream cones. Next, spread cones around the gym, half upside down and half right side up. Finally, have the teams race to flip as many cones as possible to either volcanoes or ice cream cones.

Learn more: Warm-Up Games at Prime Coaching Sport

This fun variation on dodgeball will have your students getting exercise while having a ton of fun! Begin with three balls on a basketball court. If you are hit by a ball, you are out. If you take a step while holding a ball, you are out. There are other rules surrounding getting out and also how to get back in, which can be found in this video.

33. Musical Hula-Hoops

PE games for kindergartners that are similar to party games are some of our favorites! Think musical chairs but with Hula-Hoops! Lay enough Hula-Hoops around the edge of the gym minus five students since they will be in the muscle pot. Once the music starts, students walk around the gym. When the music stops, whoever doesn’t find a Hula-Hoop becomes the new muscle pot!

34. 10-Second Tag

This game is perfect to play at the beginning of the year since it helps with learning names and allows the teacher to get to know the first student in line.

35. The Border

This game is so fun and requires no equipment whatsoever. Divide the gym into two sides. One side can move freely while the other side must avoid letting their feet touch the floor by rolling around, crawling, etc.

36. Freedom Catch

This is a simple throwing, catching, and tag game that will certainly be a hit with your PE class. Captors attempt to tag players so they can send them to jail. You can be freed if someone on your team runs to a freedom cone while throwing a ball to the jailed person. If the ball is caught by the jailed person, they can rejoin the game.

37. Oscar’s Trashcan

As far as PE games for kindergartners goes, this one is a guaranteed winner since it is based on the show Sesame Street . You’ll need two large areas that can be sectioned off to use as trash cans and also a lot of medium-size balls. There are two teams who must compete to fill their opponent’s trash can while emptying their own. Once over, the trash will be counted and the team with the least amount of trash in their trash can wins!

38. 4-Way Frisbee

Divide your class into four separate teams, who will compete for points by catching a Frisbee inside one of the designated goal areas. Defenders are also able to go into the goal areas. There are a number of other rules that can be applied so you can modify the game in a way that’s best for your class.

39. Badminton King’s/Queen’s Court

This one is simple but fun since it is played rapid-fire with kids waiting their turn to take on the King or Queen of the court. Two players start and as soon as a point is earned, the loser swaps places with another player. The goal is to be the player that stays on the court the longest, consistently knocking out new opponents.

40. Jumping and Landing Stations

Kids love stations and they definitely love jumping, so why not combine those things into one super-fun gym class? They’ll have a blast challenging themselves with all the different obstacles presented in this video.

41. Ninja Warrior Obstacle Course

Regardless of whether you’ve ever seen an episode of American Ninja Warrior , you are probably familiar with the concept and so are your students. Plus, you’ll probably have just as much fun as your students setting up the obstacles and testing them out!

42. Balloon Tennis

Since kids love playing keepy-uppy with a balloon, they will love taking it a step further with balloon tag!

43. Indoor Putting Green

If your school can afford to invest in these unique putting green sets, you can introduce the game of golf to kids as young as kindergarten. Who knows, you might just have a future Masters winner in your class!

44. Scooter Activities

Let’s be honest, we all have fond memories of using scooters in gym class. Regardless of whether you do a scooter sleigh or scooter hockey, we think there is something for everyone in this fun video.

45. Pick It Up

This is the perfect PE game to play if you are stuck in a small space with a good-size group. Teams win by making all of their beanbag shots and then collecting all of their dots and stacking them into a nice neat pile.

46. Dodgeball Variations

Since not all kids love having balls thrown at them, why not try a dodgeball alternative that uses gym equipment as targets rather than fellow students? For example, have each student stand in front of a Hula-Hoop with a bowling ball inside of it. Students need to protect their hoop while attempting to knock over their opponents’ pins.

What are your favorite elementary PE games to play with your class? Come and share in our We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, check out our favorite recess games for the classroom ..

You Might Also Like

25 Surefire Student Engagement Strategies To Boost Learning

Transform your learners from passive to passionate! Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physically Active Lesson Interventions

About this resource:.

Source: The Guide to Community Preventive Services

The last reviewed date indicates when the evidence for this resource last underwent a comprehensive review.

Workgroups: Physical Activity Workgroup , Adolescent Health Workgroup

Classroom-based physically active lessons are those in which teachers direct bouts of physical activity during an academic lesson. The Community Preventive Services Task Force conducted a systematic review of the evidence and recommends classroom-based physically active lesson interventions based on findings that this intervention lead to increased physical activity and to improved academic outcomes for students. The recommended lesson interventions:

- Involve moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- Range from 10 to 30 minutes in length

- Include training for teachers, like lesson plans and resources to engage students in physical activity

Objectives related to this resource (2)

Suggested citation.

Guide to Community Preventive Services. (2021). Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physically Active Lesson Interventions. Retrieved from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-classroom-based-physically-active-lesson-interventions .

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Healthy kids and the promotion of physical activity for students is a hot topic! This page offers a compilation of resources that may assist teachers in adopting classroom physical activity (listed alphabetically). At the bottom of the page are links to programming to increase physical activity across the school day. (Please also see our Materials page for implementation ideas and activities.)

Action for Healthy Kids

This site is dedicated to promoting health in children, primarily through school-based actions.

- http://www.actionforhealthykids.org

Active Classrooms

This page, part of Active Schools, offers a list of resources to aid teachers in engaging students in movement within the classroom.

- https://www.activeschoolsus.org/campaigns/active-classrooms/

Active for Life

This site, while geared at parents, offers free activity ideas for children based on age (1-12 yrs) and skill sets. It is also a resource for physical activity in children.

- Home: http://activeforlife.com

- Direct link to activity search: http://activeforlife.com/activities

Active Schools Acceleration Project

This links accesses a launch kit for CHALK/Just Move™ curriculum materials to engage students in physical activity at school.

- Launch Kit Home: http://www.activeschoolsasap.org/node/213

- Direct link to Just Move™ Start-up Guide with implementation tips: http://www.activeschoolsasap.org/files/u8/just-move-guide_final_08.20.13.pdf

- Direct link to Just Move™ Activity Cards: http://www.activeschoolsasap.org/files/u8/just_move_cards_final_08.13.13.pdf

Alliance for a Healthier Generation (Physical Activity in Schools)

This site promotes physical activity and shares guidance and resources for increasing physical activity opportunities at school. There is also an option to sign your school up for the Healthy Schools Program.

- https://www.healthiergeneration.org/take_action/schools/physical_activity

BAM! Body and Mind

This site offers information about various types of physical activity that students may wish to learn more about – what gear is needed, how to be safe, how to play, and fun facts for each activity. While these activities are not conducive to classroom physical activity, the cards may assist in the creation of an active culture and promote physical activity in students outside of school.

- http://www.cdc.gov/bam/activity/index.html

Classroom Physical Activity

As a sub-set of the Healthy Schools site, this Centers for Disease Control and Prevention page is dedicated to classroom physical activity. It offers an overview, data and policy information, and several documents on strategies for integrating physical activity into the classroom. As an additional resource, a PPT presentation can be downloaded and shared with stakeholders.

- Main page: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/classroom-pa.htm

- Direct link to PDF “Strategies for Classroom Physical Activity in Schools” : https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/pdf/ClassroomPAStrategies_508.pdf

- Direct link to PPT download “Integrate Classroom Physical Activity: Getting Students Active During School” : https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/pdf/Integrate_Classroom_PA_PPT_slides_508.PPTX

Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program – ONLINE COURSE!

Developed by the CDC as part of their “Training Tools for Healthy Schools: Promoting Health and Academic Success”, this free online course offers individuals a chance to “understand the importance and benefits of youth physical activity, recognize the components of a Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program, and learn the process for developing, implementing, and evaluating a Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program”.

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/professional_development/e-learning/CSPAP/index.html

Energizing Brain Breaks

This site primarily seeks to sell the Energizing Brain Breaks books, but also offers information about classroom physical activity breaks and relevant links.

- http://energizingbrainbreaks.com

5 Strategies for Recess Planning

This page, from the June 2017 National Association of Elementary School Principals, offers step-by-step suggestions for cultivating effective recess time for students.

- https://www.naesp.org/resource/5-strategies-for-recess-planning

The Importance of Active Classrooms

This single page, compiled by Support Real Teachers, has links to a host of helpful resources for engaging students in movement at school.

- http://www.supportrealteachers.org/brain-breaks-and-class-based-activities.html

Integrating Physical Activity into the Classroom: Practical Strategies for All School Health Leaders *NEW*

Recorded WEBINAR by Springboard to Active Schools that shares ” two new resources to help teachers and caregivers easily integrate physical activity with a safety, inclusion, and equity lens in different learning settings” while modeling movement engagement.

- https://www.ashaweb.org/integrating-physical-activity-into-the-classroom-practical-strategies-for-all-school-health-leaders

Involve Families in Physical Activity in Schools

This PDF, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, addresses the importance of parental involvement and offer tips to promote parental support of classroom physical activity practices.

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/pdf/Family_Engagement_Data_Brief_CDC_Logo_FINAL_191106.pdf

Marcia Lee Unnever, founder of Kids Focus, has compiled a list of videos relevant to brain-based learning and physical activity. Kids Focus offers brain-based movements for the early childhood and elementary classroom as well as professional training on cognition and behavioral development in childhood.

- https://kidsfocususa.com/videos

By Nemours Center, the KidsHealth website offers information about health in children. Several pages are dedicated to classroom physical activity, and include suggestions and strategies for implementation, videos, discussion questions and student worksheets to facilitate increased knowledge on fitness benefits, and more.

- KidsHealth in the Classroom home: http://classroom.kidshealth.org

- Easy Elementary Exercises: http://kidshealth.org/en/kids/bfs-elementary-execises.html?ref=classroom

- Grades preK-2 Fitness: http://kidshealth.org/classroom/prekto2/personal/fitness/fitness.pdf

- Grades 3-5 Fitness: http://kidshealth.org/classroom/3to5/personal/fitness/fitness.pdf

- Boost Grades, Improve Behavior: http://kidshealth.org/en/parents/elementary-exercises.html

- NBA FIT: http://kidshealth.org/classroom/prekto2/personal/fitness/nba_fit_classroom_color.pdf

The Kinesthetic Classroom: Teaching and Learning through Movement

This TEDx talk by the author of the book addresses the principles of the brain in relation to movement and learning.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=41gtxgDfY4s

Learning on the Move

This website, created by physical educator Liz Giles-Brown, shares a similar mission with Classrooms in Motion™ – offering information and resources for active learning – broken down into brain basics, learning to move, and moving to learn categories.

- http://www.learningonthemove.org

Made to Play

“Our generation is the least active. Ever. And that’s not ok. We’re not looking for a pro. Just a chance. If you think you have what it takes to get us moving, Nike has a way for you to join in.”

- https://www.nike.com/made-to-play

- Direct link to Designed to Move report: https://www.nike.com/pdf/made-to-play-designed-to-move-2020-report.pdf

Math & Movement

“Math & Movement uses multi-sensory learning approaches to teach students valuable skills to succeed in their school’s math and reading curricula. …students learn through different styles which is why our exercises include teaching with visual, auditory, and kinesthetic elements aligned with most state standards.”

- https://mathandmovement.com

Move Your Body, Grow Your Brain

The authors of this article, who developed a Brain-Based Teaching degree, share strategies for incorporating movement and activity into the classroom as brain-based learning.

- https://www.edutopia.org/blog/move-body-grow-brain-donna-wilson

Moving Minds Toolkit

This free PDF download, from Moving Minds, is a great resource. Drafted to advocate for active learning, it offers easy-to-read information and graphics on relevant research and implementation. (Must enter name and email to access.)

- https://www.moving-minds.com/toolkit

Physical Activity for Children

This site offers information about physical activity for youth and provides suggestions for parents and communities to support physical activity.

- http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/nutrition/nutrition/dietary_guide/hgic4032.html

RunJumpThrow

“USA Track & Field and Hershey teamed up to create RunJumpThrow (RJT), a hands-on learning program that gets kids excited about physical activity by introducing them to the basic running, jumping and throwing skills through track and field.”

- https://www.usatf.org/runjumpthrow

Safe Routes to School

To promote active transportation to school, this national partnership published a toolkit called “The Wheels on the Bike Go Round & Round: How to Get a Bike Train Rolling at Your School.” The main site also shares background and information to support walking and biking to school.

- https://www.saferoutespartnership.org/resources/toolkit/bike-train-toolkit

Springboard to Active Schools

“Since 2016, Springboard to Active Schools supports CDC-funded state departments of health and/or education to promote active school environments in school districts and schools across the country.”

- https://schoolspringboard.org

Stand Up Kids

In partnership with Let’s Move! Active Schools, this site shares interesting data on sitting vs. standing, as well as interactive data on outcomes associated with sedentary behavior, such as sitting. Also included within the site is a “Tools” page that offers movement break videos to decrease sitting time in the classroom.

- http://standupkids.org

Strategies for Recess in Schools

“Recess helps students to achieve the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity that can improve strength and endurance; enhance academic achievement; and increase self-esteem for children and adolescents. …new guidance documents that provide schools with 19 evidence-based strategies for recess, as well as a planning guide and template to help develop a written recess plan that integrates these strategies.”

- http://portal.shapeamerica.org/standards/guidelines/Strategies_for_Recess_in_Schools.aspx

TeachHub.com

These two pages from the TeachHub site offer tips and suggestions for incorporating movement into the classroom. *Moss article moved to new site

- Top 12 Classroom Fitness Activities (by Annie Condron)

- How to Use Fitness Breaks to Keep Students Alert in the Classroom (by Dick Moss)

Think Outside the Sandbox: Creative Ways to Keep Kids Active

This site, which was actually put together by a playground equipment company, offers quick suggestions on how to increase physical activity among children along with a list of resources links to other helpful sites.

- http://www.playgroundequipment.com/think-outside-the-sandbox-creative-ways-to-keep-kids-active

Using Brain Breaks to Restore Students’ Focus

Filed on Edutopia’s website under ‘brain-based learning’, this article provides the reader an opportunity to “learn about the science and classroom applicability of these quick learning activities.”

- https://www.edutopia.org/article/brain-breaks-restore-student-focus-judy-willis

Programming to Increase Activity

100 Mile Club

The 100 Mile Club a free program that encourages students to run incremental distances to reach the 100 mile goal across the academic school year. Incentives, including t-shirts, certificates, and pencils, are available for a fee.

- https://100mileclub.com

BOKS (Build Our Kids’ Success) is a free program, sponsored by Reebok, that is lead by volunteer parents before school. Check out all of the program information and how to start a program at your school!

- https://www.bokskids.org

- See also free downloads: https://www.bokskids.org/downloads

The Daily Mile

The Daily Mile, started in the UK, engages students in 15 minutes of running each day while at school. Given the success and simplicity of this free program, schools around the world are getting their students active using The Daily Mile.

- Home: https://www.thedailymile.org

- United States site: https://www.thedailymile.us

SEL Journeys (by CATCH)

SEL Journeys is “a digital experience that allows students to explore the world through movement and the arts while focusing on Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) themes like diversity, empathy and kindness.” Some free resources and demonstrations are available; pricing available on request.

- https://edumotion.com

Marathon Kids

Marathon Kids, now partnered with Nike, invites schools to start running clubs to get students active.

- https://marathonkids.org

My School in Motion

The motto of the My School in Motion program, “Moving together every morning for healthier minds, bodies, and attitudes!”, is achieved through “a school-wide daily fitness, nutrition, health and wellness program performed at the beginning of every school day.” Contact My School in Motion, Inc. today to get your school in motion!

- https://www.myschoolinmotion.org

Physical Activity: Interventions to Increase Active Travel to School

“The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) recommends interventions to increase active travel to school based on evidence they increase walking among students and reduce risks for traffic-related injury.”

- https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-interventions-increase-active-travel-school

WassUp 1.9.4.5 timestamp: 2024-05-16 03:15:22AM UTC (03:15AM) If above timestamp is not current time, this page is cached.

Save 20% & Free Shipping.

- Free Resources

Your cart is currently empty.

Continue Shopping

- Sensory Sack

- Sensory Rattles

- Sensory Baby Mat

- Matching Game

- Fidgets Bands

- Light Covers

- Wall Posters

- Storage Solution

- Weighted Blanket

- Fidget Toys

- Anti Blue Glasses

- Fine Motor Toys

- Coloring Activities

- Electronic Toys

How Physical Activity Benefits Classroom Learning

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Science behind Physical Activity and Learning

- Brain Structure 🧠

- Neurotransmitters and Hormones ✨

- Increased Oxygen Flow 💨

- Reduced Stress and Anxiety 😔

- Physical Activity Programs in Schools

- Classroom Exercises 👩🏫

- Brain Breaks 🧠

- Physical Education Classes 🏃♀️

- Active Transportation 🚶

- Improved Academic Performance

- Test Scores and Grades 📝

- Attention and Focus 🙇

- Memory and Retention 💭

- Creativity and Problem-Solving Skills ➿

- Health Benefits of Physical Activity

- Reduced Risk of Chronic Diseases ❤️

- Improved Sleep 😴

- Better Mental Health 😊

1. Introduction

As students spend more and more time sitting in classrooms, teachers and schools are searching for ways to make learning more engaging and effective. One approach gaining traction is integrating physical activity into the curriculum. While the benefits of physical activity on overall health are well-known, the impact on academic performance is often overlooked. In this article, we'll explore the science behind how physical activity can benefit classroom learning and discuss the various ways schools can incorporate physical activity into the school day. Whether you're a teacher, parent, or student, read on to discover how physical activity can improve academic performance and enhance overall well-being.

2. The Science behind Physical Activity and Learning

Physical activity triggers several changes in the brain that can enhance learning and cognitive performance . Here are a few ways physical activity can benefit classroom learning:

- Brain Structure

- Neurotransmitters and Hormones

Physical activity also releases neurotransmitters and hormones that are crucial for brain function. For example, exercise can increase the production of dopamine, which is associated with motivation and reward. Additionally, exercise can stimulate the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is critical for the growth and survival of brain cells.

- Increased Oxygen Flow

Physical activity can increase blood flow and oxygen supply to the brain, which is essential for optimal cognitive function. This increased oxygen flow can help students feel more alert and focused during class.

- Reduced Stress and Anxiety

Physical activity has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety levels . This is significant because high levels of stress and anxiety can impair cognitive function and hinder academic performance.

3. Physical Activity Programs in Schools

To integrate physical activity into the classroom, schools can implement various programs and initiatives. Here are a few examples:

- Classroom Exercises

Teachers can incorporate brief exercise breaks into their lessons to help students stay active and focused. These exercises can include simple stretches or movements that don't require much space.

- Brain Breaks

Brain breaks are short breaks that give students the opportunity to move around and engage in physical activity. These breaks can range from a few minutes to a full recess period.

- Physical Education Classes

Physical education classes provide students with structured exercise opportunities that can benefit their physical and mental health.

- Active Transportation

Walking or biking to school is an excellent way for students to get regular physical activity. Additionally, this mode of transportation can reduce traffic congestion and air pollution around schools. Make sure they have chaperones if needed or a teacher makes sure the kids are leaving the school safely.

4. Improved Academic Performance

Physical activity has been shown to improve academic performance in several ways:

- Test Scores and Grades

Studies have found a positive correlation between physical activity and academic performance. Specifically, students who participate in physical activity tend to score higher on tests and receive better grades.

- Attention and Focus

Physical activity can improve attention and focus in the classroom . For example, students who participated in brief exercise breaks during class were more attentive and less distracted than their peers who did not.

- Memory and Retention

Physical activity can also enhance memory and retention . Research has shown that exercise can improve the hippocampus's size

- Creativity and Problem-Solving Skills

Physical activity can also enhance creativity and problem-solving skills. Exercise has been shown to increase the production of new brain cells in the hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with these cognitive processes.

5. Health Benefits of Physical Activity

Beyond its impact on academic performance, physical activity has numerous health benefits that can improve students' overall well-being:

- Reduced Risk of Chronic Diseases

Regular physical activity can reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease . Encouraging students to be physically active from a young age can establish healthy habits that last a lifetime.

- Improved Sleep

Physical activity can also improve sleep quality and duration, which is essential for students' overall health and well-being. Studies have found that regular exercise can help students fall asleep faster and stay asleep longer.

- Better Mental Health

Physical activity has been shown to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, which can have a significant impact on students' mental health. Incorporating physical activity into the school day can provide students with a valuable outlet for stress and anxiety.

Incorporating physical activity into the classroom can benefit students' academic performance, health, and well-being. From brief exercise breaks to physical education classes, there are numerous ways schools can promote physical activity and create a more engaging and effective learning environment. But how can we get this to be fun? Out of all the subjects, physical education should be the most fun to get our little ones pumped to go into other subjects. Incorporating education into more play based learning can have an overall net positive impact on children. How have you found fun, entertaining ways to get your kids moving, playing & learning?

- What types of physical activity are best for classroom learning?

*Any type of physical activity that gets students moving and active can benefit classroom learning. This can include brief exercise breaks, brain breaks, physical education classes, and active transportation.

- How often should students engage in physical activity during the school day?

*It is recommended that students engage in at least 60 minutes of physical activity per day, which can be spread out throughout the school day.

- What are some ways schools can promote physical activity outside of the classroom?

*Schools can promote physical activity by offering after-school sports programs, creating safe and accessible walking and biking paths, and hosting physical activity events such as field days or fun runs.

- Can physical activity benefit students with learning disabilities?

* Yes, physical activity can benefit all students, including those with learning disabilities. Research has shown that physical activity can improve cognitive function and academic performance in children with ADHD and other learning disabilities.

- How can parents encourage physical activity outside of school?

*Parents can encourage physical activity by scheduling regular family activities that involve movement, such as hikes or bike rides, and limiting screen time to encourage more active play.

Leave a comment

Added To Your Shopping Cart!

Availability

Product type

Enjoy 20% off

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Committee on Physical Activity and Physical Education in the School Environment; Food and Nutrition Board; Institute of Medicine; Kohl HW III, Cook HD, editors. Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013 Oct 30.

Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

4 Physical Activity, Fitness, and Physical Education: Effects on Academic Performance

Key messages.

- Evidence suggests that increasing physical activity and physical fitness may improve academic performance and that time in the school day dedicated to recess, physical education class, and physical activity in the classroom may also facilitate academic performance.

- Available evidence suggests that mathematics and reading are the academic topics that are most influenced by physical activity. These topics depend on efficient and effective executive function, which has been linked to physical activity and physical fitness.

- Executive function and brain health underlie academic performance. Basic cognitive functions related to attention and memory facilitate learning, and these functions are enhanced by physical activity and higher aerobic fitness.

- Single sessions of and long-term participation in physical activity improve cognitive performance and brain health. Children who participate in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity benefit the most.

- Given the importance of time on task to learning, students should be provided with frequent physical activity breaks that are developmentally appropriate.

- Although presently understudied, physically active lessons offered in the classroom may increase time on task and attention to task in the classroom setting.

Although academic performance stems from a complex interaction between intellect and contextual variables, health is a vital moderating factor in a child's ability to learn. The idea that healthy children learn better is empirically supported and well accepted ( Basch, 2010 ), and multiple studies have confirmed that health benefits are associated with physical activity, including cardiovascular and muscular fitness, bone health, psychosocial outcomes, and cognitive and brain health ( Strong et al., 2005 ; see Chapter 3 ). The relationship of physical activity and physical fitness to cognitive and brain health and to academic performance is the subject of this chapter.

Given that the brain is responsible for both mental processes and physical actions of the human body, brain health is important across the life span. In adults, brain health, representing absence of disease and optimal structure and function, is measured in terms of quality of life and effective functioning in activities of daily living. In children, brain health can be measured in terms of successful development of attention, on-task behavior, memory, and academic performance in an educational setting. This chapter reviews the findings of recent research regarding the contribution of engagement in physical activity and the attainment of a health-enhancing level of physical fitness to cognitive and brain health in children. Correlational research examining the relationship among academic performance, physical fitness, and physical activity also is described. Because research in older adults has served as a model for understanding the effects of physical activity and fitness on the developing brain during childhood, the adult research is briefly discussed. The short- and long-term cognitive benefits of both a single session of and regular participation in physical activity are summarized.

Before outlining the health benefits of physical activity and fitness, it is important to note that many factors influence academic performance. Among these are socioeconomic status ( Sirin, 2005 ), parental involvement ( Fan and Chen, 2001 ), and a host of other demographic factors. A valuable predictor of student academic performance is a parent having clear expectations for the child's academic success. Attendance is another factor confirmed as having a significant impact on academic performance ( Stanca, 2006 ; Baxter et al., 2011 ). Because children must be present to learn the desired content, attendance should be measured in considering factors related to academic performance.

- PHYSICAL FITNESS AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY: RELATION TO ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE

State-mandated academic achievement testing has had the unintended consequence of reducing opportunities for children to be physically active during the school day and beyond. In addition to a general shifting of time in school away from physical education to allow for more time on academic subjects, some children are withheld from physical education classes or recess to participate in remedial or enriched learning experiences designed to increase academic performance ( Pellegrini and Bohn, 2005 ; see Chapter 5 ). Yet little evidence supports the notion that more time allocated to subject matter will translate into better test scores. Indeed, 11 of 14 correlational studies of physical activity during the school day demonstrate a positive relationship to academic performance ( Rasberry et al., 2011 ). Overall, a rapidly growing body of work suggests that time spent engaged in physical activity is related not only to a healthier body but also to a healthier mind ( Hillman et al., 2008 ).