- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Twin Studies

Introduction, reference works.

- Special Collections

- Methodology

- Historical Perspectives

- Research Methods and Design

- Biological Processes

- Conjoined Twinning

- Twinning Rates

- Zygosity Diagnosis

- Old Studies

- New Studies

- Cognitive Abilities

- Personality

- Bereavement

- Behavioral and Learning Problems

- Developmental Studies

- Interests, Attitudes, and Values

- Twin Relationships

- Sexual Behavior and Orientation

- Psychiatric Disorders

- Neurological Disorders

- Economic and Political Behavior

- Body Size and Structure

- Disease Susceptibility

- Epigenetics

- Molecular Genetics

- Brain Imaging

- Controversies and Challenges

- Education and Parenting

- Life Histories

- Arts and Sciences

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Birth Order

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Intelligence

- Prenatal Development

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspectives on Adoption

- The Flynn Effect

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Remote Work

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Twin Studies by Nancy L. Segal LAST REVIEWED: 19 March 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 19 March 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0101

Twin research is an informative approach for understanding the genetic and environmental influences affecting behavioral, physical, and medical traits. The simple yet elegant logic of the twin method derives from the differences in genetic relatedness between the two types of twins. Identical (monozygotic or MZ) twins share 100 percent of their genes, while fraternal (dizygotic or DZ) share 50 percent of their genes, on average. MZ twins result when a fertilized egg (ovum) divides during the first two weeks following conception, while DZ twins result when a woman simultaneously releases two eggs that are fertilized by two separate sperm. MZ twins are always same sex, whereas DZ twins may be same-sex or opposite-sex. However, rare events occasionally produce unusual MZ and DZ twin variations. Twin researchers compare the resemblance between MZ and DZ twins with reference to a particular trait, such as height or weight. Greater resemblance between MZ twins than DZ twins demonstrates that the trait under study is under partial genetic control. There are also various ways that twins and their families can be used in research to increase the potential yield of a study. Sophisticated biometrical techniques can estimate the extent of difference among people associated with their genes, shared environments and nonshared environments. Twin research has proliferated in recent years. This is largely because the power of the twin method for understanding the origin and development of human traits has become increasingly appreciated by investigators representing diverse fields. Twinning rates have also increased dramatically since 1980, especially the rate of fraternal twinning as a consequence of fertility treatments. There have been stunning advances in quantitative mathematical methodology that continue to increase the value of twin studies. Lastly, there have been enormous developments in the molecular genetics and genomics fields with respect to associating genes posing increased risks for specific behaviors and disease. Twins will continue to play a prominent role in these endeavors. The sources presented in this article represent a wide range of areas and topics within twin research. General overviews of the field, both historical and current, are provided, as well as a listing of special collections in twin research, that is, books and journals focusing on a particular topic or theme and web addresses. The largest section includes topics reflecting the widening range of psychological, biological, and medical traits that have been examined via twin research methods. The section on twin-based perspectives provides sources treating unusual twin-related topics.

Twin research has had a successful yet controversial past, a trend that has continued through the present. Despite the wealth of information that has been derived from twin studies, various methodological and interpretive aspects continue to be questioned. The historical roots of twin studies, its acceptance into the mainstream of psychological and medical research, and its challenges are documented in a number of books, articles, and essays. The resources in this section span a wide range of twin-related topics. The five books are appropriate for experienced investigators and new scientists, as well as general audiences searching for information about the many ways twins are used in scientific studies. Johnson, et al. 2009 and Boomsma, et al. 2002 go more deeply into current trends in twin research but will interest anyone concerned with what twin studies have (and can potentially) reveal about the origins of variation in human behavioral and physical traits. The selections here include general overviews of the biological and psychological aspects of twinship ( Scheinfeld 1967 ), the nature-nurture debates ( Wright 1997 ), overviews of unusual topics in the study of twins ( Segal 2000 ), and cultural issues ( Stewart 2003 , Piontelli 2008 ). An older, but still informative account of the biology and psychology of twinning is also provided ( Bryan 1983 ).

Boomsma, Dorret, Andreas Busjahn, and Leona Peltonen. 2002. Classical twin studies and beyond. Nature Reviews (Genetics) 3:872–882.

DOI: 10.1038/nrg932

Describes and documents the potential of large twin registries to study complex human traits. Discusses various twin research designs (e.g., classic twin study, co-twin control, genotyping of marker loci) and their application in scientific research. Includes lists of twin registers in and outside European countries.

Bryan, Elizabeth. 1983. The nature and nurture of twins . London: Ballière Tindall.

A comprehensive examination of biological and psychological aspects of twinning by a British physician. Includes helpful information on twin types, twinning rates, and related topics. Also includes some specific topics not covered elsewhere, such as twin loss and twins with special needs.

Johnson, Wendy, Eric Turkheimer, Irving I. Gottesman, and Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. 2009. Beyond heritability: Twin studies in behavioral research. Current Directions in Psychological Science 18:217–220.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01639.x

Makes the argument that the heritability of most behavioral traits is now known, yet twin studies retain a vital place in psychological research. Twin research should direct greater attention to environmental influences on behavior in a quest to identify its underlying mechanisms.

Piontelli, Alessandra. 2008. Twins in the world: The legends they inspire and the lives they lead . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Examines beliefs and practices regarding twinship from a cross-cultural perspective. The author’s background in neurology, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and obstetrics substantially enriches the firsthand experiences she describes.

Scheinfeld, Amram. 1967. Twins and supertwins . Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott.

An older, but complete survey of the history, biology, and psychology of twins before this became mainstream science. Often includes information that is difficult to find elsewhere.

Segal, Nancy L. 2000. Entwined lives: Twins and what they tell us about human behavior . New York: Plume.

A comprehensive overview of the background, methods, findings, and implications of twin research. Nine of the sixteen chapters address special topics such as athletic performance, legal circumstances, conjoined twinning, and noteworthy twin pairs. Written by a professor of psychology.

Stewart, Ellen. 2003. Exploring twins: Towards a social analysis of twinship . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Addresses the social, societal, and cultural aspects of twinship. Also considers various views of twins from the perspectives of the twins, their family members, and society at large. Draws on sources from multiple disciplines.

Wright, Lawrence. 1997. Twins and what they tell us about who we are . New York: John Wiley.

An account of research concerning genetic and environmental events making MZ twins both alike and different in behavior. The focus is largely, but not exclusively, on separately raised twins. A very good starting point for work in this area, although more recent publications from the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart should be consulted. Written by a well-known journalist.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Critical Thinking

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- Heuristics and Biases

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Personality Psychology

- Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies: From Car...

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Protocol Analysis

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Research Methods

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Cognition

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Twin Studies

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 August 2018

Genetics, personality and wellbeing. A twin study of traits, facets and life satisfaction

- Espen Røysamb 1 , 2 ,

- Ragnhild B. Nes 1 , 2 ,

- Nikolai O. Czajkowski 1 , 2 &

- Olav Vassend 1

Scientific Reports volume 8 , Article number: 12298 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

80k Accesses

52 Citations

101 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Heritable quantitative trait

- Human behaviour

Human wellbeing is influenced by personality traits, in particular neuroticism and extraversion. Little is known about which facets that drive these associations, and the role of genes and environments. Our aim was to identify personality facets that are important for life satisfaction, and to estimate the contribution of genetic and environmental factors in the association between personality and life satisfaction. Norwegian twins (N = 1,516, age 50–65, response rate 71%) responded to a personality instrument (NEO-PI-R) and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS). Regression analyses and biometric modeling were used to examine influences from personality traits and facets, and to estimate genetic and environmental contributions. Neuroticism and extraversion explained 24%, and personality facets accounted for 32% of the variance in life satisfaction. Four facets were particularly important; anxiety and depression in the neuroticism domain, and activity and positive emotions within extraversion. Heritability of life satisfaction was 0.31 (0.22–0.40), of which 65% was explained by personality-related genetic influences. The remaining genetic variance was unique to life satisfaction. The association between personality and life satisfaction is driven mainly by four, predominantly emotional, personality facets. Genetic factors play an important role in these associations, but influence life satisfaction also beyond the effects of personality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Disentangling the personality pathways to well-being

Personality traits and dimensions of mental health

Predicting wellbeing over one year using sociodemographic factors, personality, health behaviours, cognition, and life events

Introduction.

Human wellbeing and life satisfaction are influenced by life events, health, economy and social relations 1 , 2 . Life satisfaction is also closely connected to personality traits 3 , 4 , but the nature of this relation is partly unknown. There is limited knowledge about which specific aspects, or facets, of personality are most important. Further, both personality and life satisfaction are influenced by genetic factors 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , but we have inadequate understanding of the role of genetic and environmental factors in explaining the links between personality and life satisfaction. Which traits, and which particular facets, are most important for promoting or obstructing individual life satisfaction? Are the associations accounted for by genetic factors, environmental factors, or both? Does the genetic influence on life satisfaction stem entirely from personality related genetics, or do genetic factors for life satisfaction operate independently of personality?

The scientific study of the good life and wellbeing has prospered in recent years 9 , 10 , 11 . As the field has grown, a number of constructs and approaches have emerged. The construct of subjective wellbeing (SWB) occupies a central position, and is typically seen as comprising three components - frequent positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and presence of life satisfaction 12 . Life satisfaction represents a global evaluation of life, a mental summarizing of life as good, or not so good, according to the individual’s own values, norms, and ideals 13 . As such, life satisfaction constitutes the key cognitive component in SWB and positive mental health 12 , 14 . In parallel with SWB, the construct of psychological wellbeing (PWB) contains components such as engagement, personal growth, and flow-experiences, thereby focusing more on functioning well than feeling well 15 , 16 , 17 . Research on SWB and PWB represent two different, but complimentary traditions, focusing on distinguishable yet related dimensions of wellbeing overall. The dimensions of SWB and PWB have also been integrated into broader models, such as the tripartite model of mental wellbeing (MWB) including emotional, psychological and also social wellbeing 18 . Thus, in correspondence with research on taxonomies and the nature of psychopathology (i.e., illbeing), the wellbeing field today addresses several aspects of the good life. Life satisfaction represents a central component in SWB in particular, but features as an important aspect inherent in most models.

Genetics of Wellbeing

Genetic factors appear to play an important role in most human characteristics 19 and wellbeing is no exception. Heritability estimates for different conceptualizations of wellbeing typically range from 0.30 to 0.50 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 . A meta-analysis of 13 studies from seven different countries and including more than 30,000 twins, reported a weighted average heritability of 0.40 for wellbeing 5 . This meta-analysis also found substantial heterogeneity in heritability estimates across studies, beyond that expected by random fluctuations, thus verifying the theoretical notion that there is no fixed heritability for wellbeing. Rather, the share of variance accounted for by genetic factors varies across cultures, age groups, and the particular wellbeing phenomena studied. Another meta-analysis by Bartels 6 , with somewhat different inclusion criteria, samples and analytic strategy reported an average heritability of 0.36 for wellbeing.

There is evidence of a common genetic influence on different wellbeing components such as subjective happiness, life satisfaction, SWB and PWB 24 , 26 , but also genetic influences that are specific to the different components 26 , 27 . The genetic factors in wellbeing are partly related to the genetic influences on social support 28 , and inversely, depression 29 and internalizing disorders 30 , 31 , 32 . Additionally, longitudinal studies have shown that genetic factors account for most of the stability in wellbeing with heritability for the stable variance, or dispositional wellbeing, estimated in the 70–90% range 33 , 34 . By contrast, environmental factors constitute the major source of change in wellbeing 34 , 35 .

Despite clear evidence of substantial genetic influences on wellbeing in general, findings on life satisfaction are somewhat divergent, with heritability estimates ranging from zero to 0.59 24 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 . The meta-analysis by Bartels 6 examined heritability of life satisfaction specifically, and reported an average heritability of 0.32. Thus, life satisfaction appears to be somewhat more influenced by environmental factors than other dimensions of wellbeing. Further, although levels of life satisfaction commonly vary only moderately with age, there might be age-related moderation of genetic and environmental factors. As life satisfaction represents an evaluation of life-so-far, life at older age likely include more life events, adversaries and accomplishments than life at younger age, thereby suggesting stronger environmental than genetic effects. There is a need for more knowledge about the genetic and environmental influences on life satisfaction in the mature population, measured by validated and reliable multi-item instruments.

Recent advances in molecular genetics have contributed to our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of wellbeing – including heritability. Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) uses genotyping of common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in unrelated individuals to estimate heritability. Rietveld, et al . 39 reported that up to 18% of the variance in wellbeing can be explained by cumulative additive effects of genetic variants that are frequent in the population. This suggests that common genetic polymorphisms account for nearly half of the overall heritability of SWB. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) are used to identify specific genetic variants associated with a phenotype. Recently, Okbay, et al . 40 used GWAS in a sample of 298,420 individuals, and identified three credible genetic loci associated with wellbeing. However, these three variants explained only a small fraction (4%) of the variance. Molecular genetic studies expand rapidly and are expected to provide important new insights into the genetics of wellbeing. However, it also seems clear that twin and family studies are unique in their ability to capture the total genetic and environmental factors involved, along with the overall overlap and specificity across different characteristics.

Personality and Life-Satisfaction

Personality refers to relatively stable and characteristic patterns of cognition, emotion, and behavior that vary across individuals. These patterns are commonly described in terms of specific personality traits. The most widely known trait models today are the five-factor and big five models 41 , 42 , which converge on five broad personality traits, including extraversion, neuroticism, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. There is a well-established relationship between personality traits and wellbeing in general, and personality and life satisfaction in particular 3 , 4 , 43 . More specifically, the big five traits of neuroticism and extraversion consistently explain substantial amounts of variance in wellbeing. The findings are more mixed regarding the trait of conscientiousness, whereas agreeableness and openness seem to play a limited, or negligible role in wellbeing 3 , 43 , 44 .

The five-factor model of personality is hierarchical with the higher-order domains (traits) comprising a set of lower-order facets 45 . For example, in the NEO-PI perspective, as developed by Costa and McCrae 41 , the domain of neuroticism includes the facets of anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness and vulnerability to stress. Correspondingly, the domain of extraversion includes warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement-seeking and positive emotions. Despite solid evidence for relations between the general big five factors and wellbeing, there is still limited knowledge about which facets of the traits that contribute the most to wellbeing.

Theoretically, inter-personal facets such as warmth and gregariousness (sociability) contribute to wellbeing indirectly by creating well-functioning social relationships that subsequently influence wellbeing. Social support and good social relations have quite consistently been found to correlate positively with wellbeing 28 , 46 , 47 , and may partly be influenced by personality traits and facets.

There is also theoretical reason to expect factors contributing to accomplishments and goal attainment , in the conscientiousness domain, to be important for life satisfaction 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 . Life satisfaction judgments consider the gap between actual states and ideal states. Personality facets such as competence, self-discipline, achievement-striving and dutifulness may be important in obtaining ideal states, and are thus likely to predict life satisfaction.

Finally, personality tendencies to certain emotional experiences, such as anxiety or positive emotions may similarly influence wellbeing as life satisfaction judgments are coloured by both current emotional states and by memories of past emotional episodes. For example, a personality disposition to experience positive emotions may contribute to many episodes of joy and enthusiasm. These episodes may constitute a basis for the subsequent evaluation of life so far 4 , 52 , 53 . Thus, from a theoretical perspective both interpersonal facets, accomplishment-related facets and emotional facets would be important in generating a good life.

Empirical examinations of relations between personality facets and life satisfaction are limited. However, a few studies have shed light on the issue. Schimmack and colleagues 52 found the depression facet of neuroticism, and the positive emotions facet of extraversion to be the strongest and most consistent predictors of life satisfaction. They concluded that depression is more important than anxiety or anger, and a cheerful temperament is more important than being active or sociable. Quevedo and Abella 54 found depression and the achievement striving facet of conscientiousness, but not positive emotions, to be the important facets, whereas Albuquerque, et al . 55 identified depression and positive emotions as central, and found an additional effect from the vulnerability facet of neuroticism. Finally, Anglim and Grant 56 reported significant semi-partial correlations between life satisfaction and the three facets of depression, self-consciousness and cheerfulness.

These studies have provided important knowledge about the nuanced associations between personality and life satisfaction, and point to some particularly important personality facets. Yet, findings so far are limited, as the results are partly divergent, and mostly based on (young) student samples and convenience samples. Consequently, there is a need for replication of findings and expansion of cultures and age groups studied.

Genetic and Environmental Factors in Personality and Life Satisfaction

Personality traits are relatively stable characteristics, and there is considerable evidence for genetic components 57 , 58 . Although associations between personality traits, and partly their facets, and wellbeing are established, there is limited knowledge about the mechanisms involved in these associations. Are the associations between personality and wellbeing due to common genetic factors, and is the entire heritability of wellbeing accounted for by the genetic factors in personality – is wellbeing genetically speaking a personality thing?

A few studies have addressed these questions at the level of broad personality traits. First, Weiss and colleagues 59 found a global SWB-measure to be accounted for by unique genetic effects for neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness, and by a common genetic factor that influenced all five personality domains. Environmental factors also contributed to the associations, but there were no genetic effects unique to SWB. In a similar vein, Hahn and colleagues 38 reported shared genetic effects for life satisfaction and the traits of neuroticism and extraversion, but not conscientiousness. Both additive and non-additive genetic effects contributed to the relation between personality and life satisfaction, and again the entire heritability of life satisfaction was accounted for by personality-related genetic factors. Finally, a study examining personality traits and flourishing found substantial genetic effects on the associations, but also identified a unique genetic influence on wellbeing, unrelated to personality 60 . This latter study was unique in its focus on the construct of flourishing as comprising both eudaimonic and hedonic aspects of wellbeing, based on Keyes’ tripartite model including emotional, psychological and social wellbeing 61 , and thereby also involving both feeling good and functioning well.

Thus, a few recent studies have reported exciting evidence of a substantial genetic contribution to the association between personality traits and wellbeing. However, several important questions remain to be addressed. First, no studies to date have examined genetic and environmental contributions to the associations between personality facets and wellbeing. Given the findings for broad personality traits, we hypothesize considerable genetic effects also for their facets. Yet, the magnitude of such effects is unknown. Second, only one study 38 has examined life satisfaction specifically – rather than global measures of wellbeing. Third, as previous studies have relied only on short-form measures of broader traits, there is a pressing need for examining both traits and facets in relation to life satisfaction by means of comprehensive, valid, well-established instruments. Fourth, findings from the few previous studies are divergent as to whether the entire genetic effect on wellbeing is due to personality-related genetic influences. Fifth, whereas prior studies have examined samples with broad age ranges, we wanted to examine a specific period in life – middle to late adulthood – to assess how relatively stable personality characteristics contribute to life satisfaction in a life course perspective. Finally, as previous studies have been inconclusive regarding sex-differences in the underlying etiology of wellbeing 6 , 62 , we also wanted to test for such differences.

The aims of the current study were to (a) identify personality traits and facets that contribute uniquely to life satisfaction, and thereby pinpoint the dispositional constituents of a happy personality, (b) estimate the heritability of life satisfaction in middle to late adulthood, (c) disentangle the genetic and environmental influences shared by personality traits/facets, and life satisfaction, and finally hence to (d) determine whether all of the genetic influence on life satisfaction is due to personality related genetic factors as suggested by some previous studies.

Correlation and Regression Analyses

As shown in Table 1 , neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness were all significantly correlated with life satisfaction, while agreeableness and openness were not. The strongest correlation was found for neuroticism, yet with substantial associations also for extraversion and conscientiousness. In the multiple regression analysis including these three factors, only neuroticism and extraversion showed significant unique contributions. The effects remained when controlling for sex and age. A total of 24% of the variance in life satisfaction was accounted for.

We next examined the associations for all the 30 personality facets. Table 2 shows the resulting correlations. A total of 23 facets were significantly associated with life satisfaction. In the neuroticism domain, all facets showed significant correlations, ranging from −0.14 for impulsiveness to −0.51 for depression. Within extraversion, excitement seeking was virtually unrelated (0.05) to life satisfaction, whereas positive emotions (0.30) and activity (0.28) showed substantial associations. In the openness domain, only one facet, ideas, showed a significant but very modest correlation (0.08). The agreeableness domain was notable for a combination of positive and negative associations. Trust (0.17) and altruism (0.09) were positively associated with life satisfaction, while negative associations were shown for modesty (−0.08) and tendermindedness (−0.08). Finally, in the conscientiousness domain, all factors showed significant and positive correlations, and in particular competence (0.30) and self-discipline (0.28) appeared to be potentially important.

Next, regression analyses were conducted in which all 30 facets were tested simultaneously. Ten facets showed significant and unique effects (Table 2 ). In total, these facets explained 33% of the variance (adjusted R 2 = 32%) in life satisfaction. Four facets yielded substantial betas, that is above 0.10, and with p < 0.01, namely N1-anxiety, N3-depression, E4-activity and E6-positive emotions (label N1 refers to Neuroticism facet 1, etc). The remaining significant facets were found across all personality domains and included the openness facets of values and actions, the agreeableness facet of compliance, and the conscientiousness facets of order and deliberation. However, these effects were relatively minor (i.e., beta <0.10). Also, when performing Bonferroni correction and examining the False Discovery Rate 63 , only the four facets with betas >0.10 retained p < 0.01. Thus, for the biometric analyses disentangling genetic and environmental effects we focused on these four facets with substantial and significant effects. Summarizing the regression findings, the happy, or satisfied personality is given by the equation:

Biometric twin analyses

Twin-cotwin correlations across zygosity groups were calculated for the neuroticism and extraversion traits, the four major facets (i.e., anxiety, depression, positive emotion, activity) and life satisfaction. Table 3 shows the correlations. In general, the monozygotic (MZ) correlations were substantial, and in all cases higher than the corresponding dizygotic (DZ) correlations, indicating additive genetic effects.

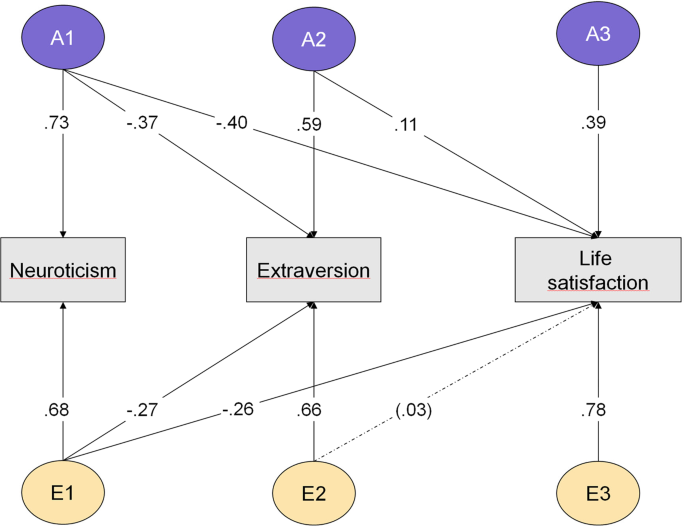

Based on the findings from the regression analyses, we next tested a set of tri-variate Cholesky models including neuroticism, extraversion and life satisfaction. Table 4 (upper part, block I) shows the fit of the different models. Model 1 included additive genetic (A), common environmental (C) and non-shared environmental (E) factors, and allowed estimates to vary across sex. Model 2, which included only A and E effects, did not fit significantly worse (i.e., Δ − 2LL = 0.89, Δdf = 12, n.s.) and produced a lower AIC value. Further, models 3 and 4, involving scalar sex-limitation, yielded additional improvements in fit, that is, increasingly lower AIC values, no significant reduction in fit, and more parsimony. Finally, models 5 and 6, where parameters were constrained to be equal across sex, resulted in higher AIC and worse fit. Thus, model 4 yielded overall best fit, and included only A and E effects with standardized parameters similar for men and women. Figure 1 shows the Cholesky parameters of the model.

Biometric Cholesky model of neuroticism, extraversion and life satisfaction. A = Additive genetic factor; E = Non-shared environmental factor; All parameters: p < 0.05, except one parameter (n.s.) in parenthesis and dotted arrow.

Heritability estimates (with 95% CIs) were 0.53 (0.46; 0.60) for neuroticism, 0.49 (0.41; 0.56) for extraversion and 0.32 (0.23; 0.41) for life satisfaction. Based on the Cholesky model we also calculated the genetic and environmental correlations between the two personality traits and life satisfaction. Genetic correlations were −0.70 (−0.58; −0.83) for neuroticism, and 0.53 (0.37; 0.68) for extraversion. Correspondingly, environmental correlations were −0.32 (−0.23; −0.40) for neuroticism and 0.15 (0.08; 0.24) for extraversion.

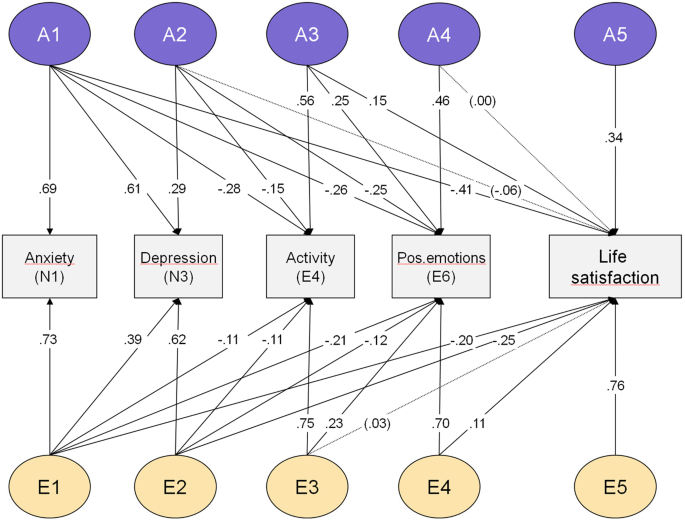

Moving from the big five factors to the personality facets, again we tested a set of models including the four facets found to be most strongly predictive of life satisfaction. Table 4 (lower part, block II, models 7–12) shows the results. Again, the best fitting model included only A and E effects (model 10), and standardized estimates did not differ across sex. Figure 2 shows the parameter estimates of the best model.

Biometric Cholesky model of four personality facets (anxiety, depression, activity and positive emotions) and life satisfaction. A = Additive genetic factor; E = Non-shared environmental factor; N = Neuroticism; E = Extraversion. All parameters: p < 0.05, except three parameters in parentheses and dotted arrows.

In this best-fitting model, heritabilities were estimated to 0.47 (0.40–0.54) for anxiety, 0.46 (0.38–0.53) for depression, 0.42 (0.33–0.49) for activity, 0.40 (0.32–0.48) for positive emotions, and 0.31 (0.22–0.40) for life satisfaction. As can be seen in Fig. 2 , genetic factors from both the neuroticism and extraversion facets uniquely influenced life satisfaction. However, after the effect of latent factor A1 (reflecting the genetic variance in anxiety) was accounted for, there was no additional genetic effect from the unique genetic factor of depression (A2). Likewise, the genetic variance in activity (A3) influenced life satisfaction, but there was no additional genetic effect from positive emotions (E4). Thus, the genetic variance in each of the two personality domains, which influenced life satisfaction, appeared to be shared by the facets within their respective domain (neuroticism or extraversion), and the facet-specific influences on life satisfaction appeared to be driven by environmental effects. Notable is also the unique genetic factor (A5) influencing life satisfaction after all the genetic effects of the facets were accounted for.

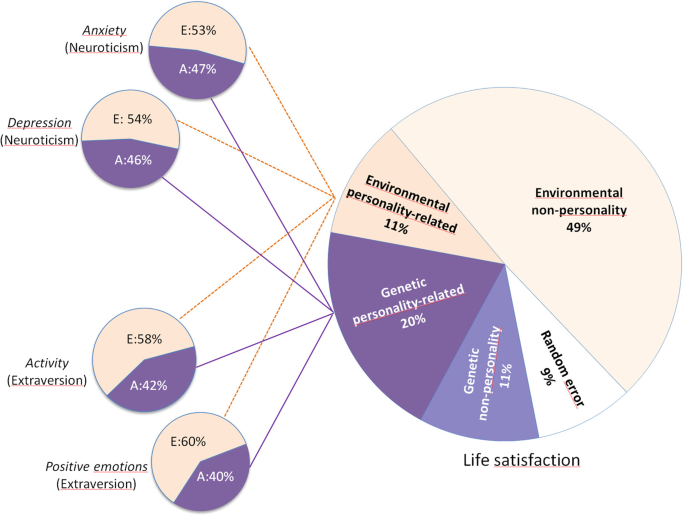

A total of 20% of the variance in life satisfaction was accounted for by personality-related genetic factors, and 11% was explained by a genetic factor unrelated to personality. Thus, of the total heritability of life satisfaction ( h 2 = 0.31), about 65% was driven by personality genetic factors, and the remaining 35% was due genetic influences independent of personality. Further, the combined effect of personality facets on life satisfaction also involved environmental effects, accounting for 11% of the variance. Finally, 58% of the variance in life satisfaction was environmental in origin and unrelated to personality. This environmental component includes random measurement error (1-alpha = 9%), thus implying an estimated true non-shared environmental component of 49%. Figure 3 shows the decomposed sources of variance for life satisfaction, along the corresponding variance components of the four facets.

Life satisfaction: Sources of origin decomposed. Genetic and non-shared environmental components, divided into personality-based and non-personality sources. Estimated random error (1-α) also shown for life satisfaction. For facets, additive genetic (A) and non-shared environmental variance (E) shown.

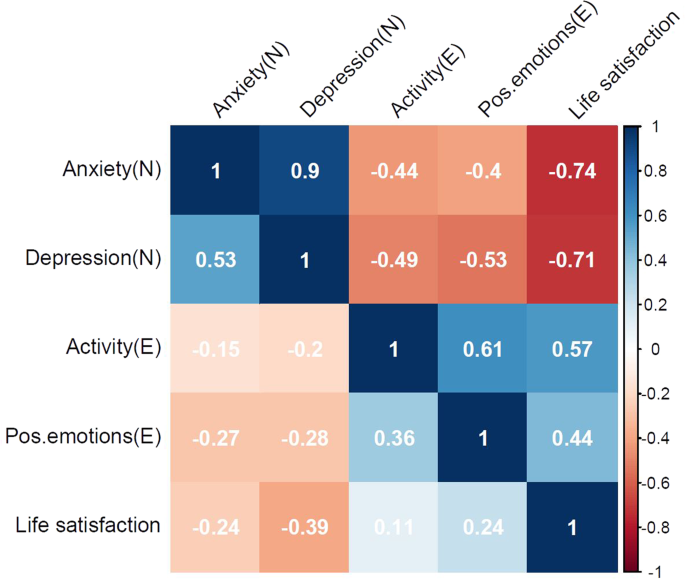

Based on the best-fitting model, we also calculated genetic and environmental correlations for the variables, shown in Fig. 4 , above and below the diagonal, respectively. Generally, the genetic correlations within personality domains were high, and the genetic correlations between facets and life satisfaction were moderate to high. The corresponding environmental correlations were generally lower, but suggested also important associations due to environmental factors.

Genetic and environmental correlations, above and below diagonal, respectively.

We set out to delineate etiological factors involved in the associations between personality and life satisfaction. Personality traits are well-established predictors of wellbeing in general and life satisfaction in particular 3 , 43 . The issue of why personality traits influence life satisfaction was addressed along two paths: First, we examined the broad personality traits and the specific personality facets that drive the effects from traits. Second, we examined the role of genetic and environmental factors in the link between personality and life satisfaction.

Personality and life satisfaction

At the level of broad traits, neuroticism and extraversion were uniquely predictive of life satisfaction, in line with previous studies 3 , 4 . Further, four facets of unique importance for life satisfaction were identified, namely anxiety and depression from the neuroticism domain, and positive emotions and activity from the extraversion domain. The happy, or satisfied personality thus seems to have low levels of anxiety and depression, and high levels of positive emotions and activity. The highly emotional nature of these facets is noteworthy. That is, three out of the four facets explicitly refer to affective tendencies, whereas the fourth facet (activity) adds vigor, energy and liveliness 41 . Thus, the cognitive evaluation of life satisfaction is partly based on emotional tendencies inherent in the big five model. Our findings accord with previous studies in identifying depression, and partly positive emotions, as central predictors of life satisfaction 52 , 55 . However, whereas prior studies have found facets such as vulnerability, excitement-seeking 52 , and achievement striving 54 to be significant, in this population based sample covering middle to late adulthood, we found anxiety and activity to be important.

Although a high number of facets were correlated with life satisfaction at the zero-order level, most facets did not show unique effects on life satisfaction in the multivariate analyses. There were no unique effects from interpersonal facets such as warmth, assertiveness, gregariousness, trust or straightforwardness. Neither did we find effects from accomplishment-related facets such as competence, self-discipline or dutifulness. This does not imply that having warm and trustful relations, or high levels of competence, are inconsequential for wellbeing. Rather, we interpret the findings to suggest that the predominantly emotional facets are underlying tendencies accounting for some of the zero-order associations between other facets and life satisfaction.

Why and how do depression, anxiety, positive emotions and activity play such important roles in generating a good – or not so good – life? We believe that a dual set of mechanisms are involved. First, from a top-down perspective 64 , 65 , life satisfaction is influenced by a general way of seeing life, the glasses through which we perceive the world. Therefore, negative and positive affective tendencies might color our ongoing evaluations of what life has been like.

Second, and in accordance with a bottom-up perspective 64 , positive and negative affective tendencies over time contribute to life experiences that are taken into account when performing a current evaluation. That is, a person with a strong tendency to experience positive emotions and activity/energy, combined with a low tendency to depression and anxiety, might recall a high number of episodes characterized by such experiences, and thereby summarize life as mostly good. In contrast, a person prone to anxiety and depression, who experiences few positive emotions and low activity/energy, might have a mental album comprising of numerous episodes and life periods that are less satisfactory.

Importantly, depression (sadness/distress), anxiety (fear) and positive emotions are represented in most models of basic emotions 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 . These basic emotions are seen as evolutionary adaptive and functional responses to environmental exposures. Although we are all equipped with the potential to experience such emotions, from a personality perspective there are individual differences in our tendency to activate them, and as such they are encompassed as facets in the five-factor personality model. Adding the facet of activity (energy) to the equation we have four basic building blocks, inherent in our personality, that contribute uniquely to a good life. In a dual-process model these tendencies operate both by coloring current perceptions of life-so-far, and by having contributed to a number of positive and/or negative experiences throughout the life lived.

In the wellbeing-illbeing structural model (WISM), wellbeing is conceptualized as comprising both well-staying and well-moving, and illbeing is correspondingly divided into ill-staying and ill-moving 15 , 23 . The model posits that humans have various goal states, and we may experience the presence of an obtained goal state (well-staying), we may be in a process towards a desired goal (well-moving), we may experience threats implying a risk of losing goals (ill-moving), and finally we may realize that a goal state is lost (ill-staying). The current findings are noteworthy in identifying personality facets that have certain connections to these four goal-state conditions. Positive emotions can be seen as indicative of well-staying, activity is potentially important for well-moving, anxiety is a core feature of ill-moving and depression is a characteristic of loss and ill-staying. Thus, our findings lend support to the notion of well-staying, well-moving, ill-staying and ill-moving as fundamental human scenarios that all are important for generating or obstructing good lives.

The role of genetic and environmental factors

The estimated heritability for life satisfaction was 0.31. This is in the lower range of previous estimates for general wellbeing 24 , 35 , and below a meta-analysis estimate of 0.40 5 . However, although findings are divergent, several studies have reported heritability estimates for life satisfaction that are moderately lower than for other wellbeing constructs 32 , 70 , 71 , and the meta-analysis by Bartels 6 reported a heritability of 0.32 for life satisfaction. Our study is one of the first to examine life satisfaction beyond midlife specifically, with a well-established instrument. The findings point to both genetic and environmental influences – yet with the latter clearly being the most important. As such, life satisfaction appears to be more about the environmentally influenced life course, events and relationships, than about a genetically driven tendency. Such an interpretation also implies potentials for change in life satisfaction, and possibly substantial benefits of wellbeing interventions 35 , 72 .

We tested models examining sex-differences in the genetic and environmental sources of wellbeing. In line with several studies 6 , 21 , 70 , but in contrast to some others 62 , 73 , we found the heritability, and the environmental component, to be of similar magnitude for females and males. Although the total variance might vary, our findings provide evidence that the relative contribution of genetic factors is similar across sex.

While genetic factors seem to play only a moderate role for the total variability in life satisfaction, genetic factors appear to have a major role in the association between personality and life satisfaction. Both at the levels of broad traits and more specific facets, genetic factors were highly important in explaining the effect of personality on life satisfaction. That is, there are genetic factors influencing personality that also influence life satisfaction, whereas environmental factors play a more limited role in this relationship. More specifically, the genetic dispositions to experience a low degree of depression and anxiety, and a high degree of positive emotions and activity contribute to a life experienced as good and satisfactory.

To our knowledge this study is the very first to examine genetic factors in the association between personality facets and life satisfaction. In general, our finding of genetic factors playing a key role accord with the few previous studies examining broad personality traits and wellbeing in genetically informative samples 38 , 59 , 74 . However, whereas two of these previous studies found the entire heritability of wellbeing to be due to personality-related genetic factors 38 , 59 , in line with Keyes et al . 60 we identified a unique genetic factor influencing life satisfaction beyond the effect of personality, accounting for 11% of the total variance. We can only speculate on the genetic mechanisms involved. Theoretically, there could be a specific, genetically driven, tendency to having a positive outlook on life that is not captured within the five-factor model. Alternatively, there could be influences from conditions such as mental abilities or somatic disorders – both of which have substantial genetic influences 19 – that also are outside the personality domain. Further studies are required both to address this aspect of life satisfaction, and generally to delineate the complex processes starting with DNA-molecules and ending up with a person evaluating her life as good – or not.

The findings also accord with a recent molecular genetic study of the association between wellbeing and neuroticism. Okbay, et al . 40 used GWAS and bivariate Linkage Disequilibrium Score regression, and reported a genetic correlation of −0.75 between wellbeing and neuroticism. Despite the limited variance explained in the GWAS it is noteworthy that the correlation corresponds highly with the current estimate of genetic correlations of −0.70 for neuroticism, −0.74 for the anxiety facet, and −0.71 for the depression facet.

It is also noteworthy that there was a common genetic factor for anxiety and depression that contributed to life satisfaction, and there was no unique genetic variance in depression that predicted life satisfaction beyond that shared with anxiety. The facet-specific influences appear to be driven by environmental effects. Corresponding findings were seen for extraversion; a common genetic factor for activity and positive emotions contributed to the genetic variance in life satisfaction.

Strengths of the current study include a population based sample, a fairly high response rate, and well-established extensive measurements. Nevertheless, some limitations should be noted. First, as with any twin study, heritabilities and genetic correlations are not fixed figures, but are estimated for a certain population, and only future studies can validate the findings across other societies and age groups. Second, the sample size implies limited ability to identify small effects – potentially common environmental factors or sex differences. Third, although the NEO-PI-R is a well-established instrument, the reliabilities of the facets were partly limited. Measurement error is captured in the E-factor in the biometric analyses, and might contribute to reduced environmental, but not genetic, correlations.

The findings replicate previous studies of wellbeing and life satisfaction as influenced by genetic factors – with heritabilities in the 30–40% range 5 , 6 . We also replicate substantial associations between wellbeing and personality, both for the general traits of neuroticism and extraversion, and for specific facets 3 , 52 , 56 . Moreover, we identified four personality facets that appear to play an important role in driving the associations between personality and life satisfaction. These facets include basic emotional tendencies, and point to the importance of emotions as sources of direct and indirect pathways that contribute to good lives. Roughly two thirds of the genetic variance in life satisfaction was found to be due to these facets. In addition, we found a certain genetic component in life satisfaction unrelated to personality traits or facets. Finally, the findings provide solid evidence of the role of environmental factors in generating good lives – also by contributing to associations between personality and life satisfaction.

Twins were recruited from the Norwegian Twin Registry (NTR). The registry comprises several cohorts of twins 75 , 76 , and the current study drew a random sample from the cohort born 1945–1960. In 2010, questionnaires were sent to a total of 2,136 twins. After reminders, 1,516 twins responded, yielding a response rate of 71%. Of the participants, 1,272 individuals were pair responders, and 244 were single responders. Zygosity has previously been determined based on questionnaire items shown to classify correctly 97–98% of the twins 77 . The cohort, as registered in the NTR, consists only of same-sex twins, and the study sample consisted of 290 monozygotic (MZ) male twins, 247 dizygotic (DZ) male twins, 456 MZ female twins and 523 DZ female twins. The age range of the sample was 50–65 years (mean = 57.11, sd = 4.5). The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics of South-East Norway, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) developed by Ed Diener and colleagues 78 , 79 . The SWLS contains five items, such as “I am satisfied with my life”. Response options range from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree . The SWLS is widely used in wellbeing research, and has well-established psychometric properties 80 . Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was 0.91.

Personality was measured by the NEO-PI-R 45 , 81 . The NEO-PI-R contains 240 items tapping the five general factors of personality, namely neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Within each of these factors, or domains, the NEO-PI-R measures six facets, or sub-factors (see results section for overview of all 30 facets). Each of these facets is measured by eight items. Response options range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree . The NEO-PI-R is a well-established instrument, with sound psychometric properties 41 . In the current sample alphas for the five factors were 0.92 (neuroticism), 0.87 (extraversion), 0.88 (openness), 0.84 (agreeableness) and 0.87 (conscientiousness). Alphas for the facets ranged from 0.47 (C5 self-discipline) to 0.85 (N1 anxiety), with a mean of 0.67.

Correlations were used to examine the bivariate associations between life satisfaction and personality traits and their facets. Next, we used regression analyses to (a) examine the unique contributions from the five broad personality traits, and to (b) identify the facets that are important for the association between personality and life satisfaction. Due to the non-independence of observations within twin pairs we used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to account for the paired structure to obtain correct standard errors and significance levels. Further, to adjust for multiple testing we performed subsequent analyses with Bonferroni correction and the False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach 63 .

Based on the regression analyses we conducted two sets of multivariate biometric analyses to estimate the genetic and environmental contributions to the associations between personality and life satisfaction. The first set examined the relation between the major big five factors and life satisfaction. The second set of analyses focused on the specific facets that uniquely predicted life satisfaction. In order to focus on facets with substantive effects, we chose to retain only facets yielding regression betas >0.10, and with p < 0.01.

Standard Cholesky models 82 , 83 were used to estimate the genetic and environmental contributions to variance and covariance in personality and life satisfaction. All models were run with the OpenMx package in R 84 . The biometric models take advantage of the basic premise that MZ twins share 100% of their genes, whereas DZ twins share on average 50% of their segregating genes. Generally, the models allow for estimating three major sources of variance, including additive genetic factors (A), common environment (C) and non-shared environment (E). In addition, non-additive genetic effects (D) may be tested, but are only indicated if the observed MZ-correlations are more than twice the DZ-correlations. A Cholesky model is a structural equation model comprising the measured variables as observed phenotypes and the A, C and E components as latent factors (for illustration see Fig. 1 ). Models are constrained so that latent A-factors correlate perfectly among MZ-twins, and at 0.5 among DZ-twins. C-factors are correlated at unity for both zygosity groups, and E-factors are by definition uncorrelated. Different models are compared to determine the presence of the genetic and environmental effects (e.g., the fit of an ACE model is compared to an AE model) or sex-differences. In line with standard practice, we tested different types of sex-limitation models 85 . First, common sex-limitation models allow parameter estimates to vary across sex, involving differences in magnitude for genetic and environmental effects. Second, scalar sex-limitation allows the unstandardized variance-covariance matrices to vary across sex, but standardized parameters (e.g., heritabilities) are constrained to be equal. Finally, the sex-limitation models were compared with models having all parameters constrained to equal across sex. To assess models and identify the best fitting model we used the minus2LogLikelihood difference (Δ − 2LL) test, and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) 86 .

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study may be requested from the Norwegian Twin Registry. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Information about data access is available here: https://www.fhi.no/en/studies/norwegian-twin-registry/

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour (2018).

Jebb, A. T., Tay, L., Diener, E. & Oishi, S. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nature Human Behaviour 2 , 33–38 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

DeNeve, K. M. & Cooper, H. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 124 , 197–229 (1998).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Lucas, R. E. & Diener, E. In Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed .) (eds John, O. P., Robins, R. W. & Pervin, L. A.) 795–814 (Guilford Press; US, 2008).

Nes, R. B. & Røysamb, E. In Genetics of Psychological Well-Being (ed. Pluess, M.) 75–96 (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Bartels, M. Genetics of wellbeing and its components satisfaction with life, happiness, and quality of life: A review and meta-analysis of heritability studies. Behavior Genetics 45 , 137–156 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Johnson, W. & Krueger, R. F. Genetic and environmental structure of adjectives describing the domains of the Big Five Model of personality: A nationwide US twin study. J Res Pers 38 , 448–472 (2004).

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J. & Vernon, P. A. Heritability of the big five personality dimensions and their facets: A twin study. Journal of Personality 64 , 577–591 (1996).

Lucas, R. E. & Diener, E. In Handbook of emotions (3rd ed.) (eds Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J. M. & Barrett, L. F.) 471–484 (Guilford Press; US, 2008).

Diener, E. et al . Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on Subjective Well-Being. Can Psychol 58 , 87–104 (2017).

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. Handbook of well-being . (DEF Publishers, 2018).

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Lucas, R. E. In Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed . ) 187–194 (Oxford University Press; US, 2009).

Kahneman, D., Diener, E. & Schwarz, N. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology . 1999. xii, 593 (Russell Sage Foundation; US, 1999).

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E. & Smith, H. L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin 125 , 276–302 (1999).

Røysamb, E. & Nes, R. In Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-being (ed. Vitterso, J.) (Springer, 2016).

Ryff, C. D. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom 83 , 10–28 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Huta, V. & Waterman, A. S. Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a Classification and Terminology for Understanding Conceptual and Operational Definitions. J Happiness Stud 15 , 1425–1456 (2014).

Keyes, C. L. M., Myers, J. M. & Kendler, K. S. The structure of the genetic and environmental influences on mental well-being. Am. J. Public Health 100 , 2379–2384 (2010).

Polderman, T. J. C. et al . Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nature Genet. 47 , 702–709 (2015).

Nes, R. B. Happiness in behaviour genetics: Findings and implications. J Happiness Stud 11 , 369–381 (2010).

Røysamb, E., Tambs, K., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Neale, M. C. & Harris, J. R. Happiness and health: Environmental and genetic contributions to the relationship between subjective well-being, perceived health, and somatic illness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 , 1136–1146 (2003).

Nes, R. B. & Røysamb, E. Happiness in behaviour genetics: An update on heritability and changeability. J Happiness Stud 18 , 1533–1552 (2016).

Røysamb, E. & Nes, R. B. In Ha nd bo ok of we ll-be ing (eds Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L.) Ch. The genetics of well-being (DEF Publishers, 2018).

Bartels, M. & Boomsma, D. I. Born to be happy? The etiology of subjective well-being. Behavior Genetics 39 , 605–615 (2009).

Archontaki, D., Lewis, G. J. & Bates, T. C. Genetic influences on psychological well-being: a nationally representative twin study. Journal of Personality 81 , 221–230 (2013).

Franz, C. E. et al . Genetic and environmental multidimensionality of well- and ill-being in middle aged twin men. Behavior Genetics . 42 , pp (2012).

Archontaki, D., Lewis, G. J. & Bates, T. C. Genetic influences on psychological well-being: A nationally representative twin study. Journal of Personalit y . 81 , pp (2013).

Wang, R. A. H., Davis, O. S. P., Wootton, R. E., Mottershaw, A. & Haworth, C. M. A. Social support and mental health in late adolescence are correlated for genetic, as well as environmental, reasons. Sci Rep-Uk 7 (2017).

Nes, R. B. et al . Major depression and life satisfaction: A population-based twin study. J Affect Disorders 144 , 51–58 (2013).

Kendler, K. S., Myers, J. M., Maes, H. H. & Keyes, C. L. M. The relationship between the genetic and environmental influences on common internalizing psychiatric disorders and mental well-being. Behavior Genetic s . 41 , pp (2011).

Bartels, M., Cacioppo, J. T., van Beijsterveldt, T. C. E. M. & Boomsma, D. I. Exploring the association between well-being and psychopathology in adolescents. Behavior Genetic s . 43 , pp (2013).

Nes, R. B., Czajkowski, N., Røysamb, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. & Tambs, K. Well-being and ill-being: Shared environments, shared genes? The Journal of Positive Psychology 3 , 253–265 (2008).

Nes, R. B. & Røysamb, E. Happiness in Behaviour Genetics: An Update on Heritability and Changeability. J Happiness Stud 18 , 1533–1552 (2017).

Nes, R. B., Røysamb, E., Tambs, K., Harris, J. R. & Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. Subjective well-being: genetic and environmental contributions to stability and change. Psychological Medicine 36 , 1033–1042 (2006).

Røysamb, E., Nes, R. B. & Vitterso, J. In Stability of Happiness (eds Sheldon, K. & Lucas, R. E.) (Elsevier, 2014).

Caprara, G. V. et al . Human Optimal Functioning: The Genetics of Positive Orientation Towards Self, Life, and the Future. Behavior Genetics 39 , 277–284 (2009).

Harris, J. R., Pedersen, N. L., Stacey, C., McClearn, G. & Nesselroade, J. R. Age differences in the etiology of the relationship between life satisfaction and self-rated health. Journal of Aging and Health 4 , 349–368 (1992).

Hahn, E., Johnson, W. & Spinath, F. M. Beyond the heritability of life satisfaction-The roles of personality and twin-specific influences. J Res Pers 47 , 757–767 (2013).

Rietveld, C. A. et al . Molecular genetics and subjective well-being. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 , 9692–9697 (2013).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Okbay, A. et al . Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nature Genet. 48 , 624–633 (2016).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. NEO PI-R . Professional Manual . (Psychological Assessment Resourses, 1992).

Goldberg, L. R. An Alternative Description of Personality - the Big-5 Factor Structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59 , 1216–1229 (1990).

Steel, P., Schmidt, J. & Shultz, J. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 134 , 138–161 (2008).

Vitterso, J. Personality traits and subjective well-being: Emotional stability, not extraversion, is probably the important predictor. Personality and Individual Difference s . 3 1, pp (2001).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Domains and Facets - Hierarchical personality-assessment using the revised NEO personality-inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment 64 , 21–50 (1995).

Bergeman, C., Plomin, R., Pedersen, N. L. & McClearn, G. Genetic mediation of the relationship between social support and psychological well-being. Psychol Aging 6 , 640–646 (1991).

David, S. A., Boniwell, I. & Conley Ayers, A. The Oxford handbook of happiness . 1097 (Oxford University Press; US, 2013).

Seligman, M. E. P. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being . xii, 349 (Free Press; US, 2011).

Headey, B. Life goals matter to happiness: A revision of set-point theory. Soc Indic Re s . 8 6, pp (2008).

Oishi, S. & Diener, E. Goals, culture, and subjective well-being. Pers Soc Psychol B 27 , 1674–1682 (2001).

Sheldon, K. M. et al . Persistent pursuit of need-satisfying goals leads to increased happiness: A 6-month experimental longitudinal study. Motiv Emotion 34 , 39–48 (2010).

Schimmack, U., Oishi, S., Furr, R. M. & Funder, D. C. Personality and life satisfaction: A facet-level analysis. Pers Soc Psychol B 30 , 1062–1075 (2004).

Schimmack, U., Diener, E. & Oishi, S. Life-satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: The use of chronically accessible and stable sources. Journal of Personality 70 , 345–384 (2002).

Quevedo, R. J. M. & Abella, M. C. Well-being and personality: Facet-level analyses. Personality and Individual Differences 50 , 206–211 (2011).

Albuquerque, I., de Lima, M. P., Matos, M. & Figueiredo, C. Personality and Subjective Well-Being: What Hides Behind Global Analyses? Soc Indic Res 105 , 447–460 (2012).

Anglim, J. & Grant, S. Predicting Psychological and Subjective Well-Being from Personality: Incremental Prediction from 30 Facets Over the Big 5. J Happiness Stud 17 , 59–80 (2016).

Bouchard, T. J. Genetic influence on human psychological traits - A survey. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13 , 148–151 (2004).

Jang, K. L., McCrae, R. R., Angleitner, A., Riemann, R. & Livesley, W. J. Heritability of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: Support for a hierarchical model of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 , 1556–1565 (1998).

Weiss, A., Bates, T. C. & Luciano, M. Happiness is a personal(ity) thing: The genetics of personality and well-being in a representative sample. Psychological Science 19 , 205–210 (2008).

Keyes, C. L. M., Kendler, K. S., Myers, J. M. & Martin, C. C. The Genetic Overlap and Distinctiveness of Flourishing and the Big Five Personality Traits. J Happiness Stud 16 , 655–668 (2015).

Keyes, C. L. M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 43 , 207–222 (2002).

Røysamb, E., Harris, J. R., Magnus, P., Vitterso, J. & Tambs, K. Subjective well-being. Sex-specific effects of genetic and environmental factors. Personality and Individual Differences 32 , 211–223 (2002).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met 57 , 289–300 (1995).

MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Feist, G. J., Bodner, T. E., Jacobs, J. F. & Miles, M. & Tan, V. Integrating Top-down and Bottom-up Structural Models of Subjective Well-Being - a Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68 , 138–150 (1995).

Marsh, H. W. & Yeung, A. S. Top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal models: The direction of causality in multidimensional, hierarchical self-concept models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75 , 509–527 (1998).

Ekman, P. Facial Expressions of Emotion - New Findings, New Questions. Psychological Science 3 , 34–38 (1992).

Ekman, P., Sorenson, E. R. & Friesen, W. V. Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion. Science 164 , 86–& (1969).

Izard, C. E. Basic Emotions, Natural Kinds, Emotion Schemas, and a New Paradigm. Perspect Psychol Sci 2 , 260–280 (2007).

Izard, C. E. Emotion Theory and Research: Highlights, Unanswered Questions, and Emerging Issues. Annu Rev Psychol 60 , 1–25 (2009).

De Neve, J.-E., Christakis, N. A., Fowler, J. H. & Frey, B. S. Genes, economics, and happiness. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 5 , 193–211 (2012).

Franz, C. E. et al . Genetic and environmental multidimensionality of well- and ill-being in middle aged twin men. Behavior Genetics 42 , 579–591 (2012).

Bolier, L. et al . Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Bmc Public Health 13 (2013).

Bartels, M., Cacioppo, J. T., van Beijsterveldt, T. C. & Boomsma, D. I. Exploring the association between well-being and psychopathology in adolescents. Behavior Genetics 43 , 177–190 (2013).

Keyes, C. L. M., Kendler, K. S., Myers, J. M. & Martin, C. C. The Genetic Overlap and Distinctiveness of Flourishing and the Big Five Personality Traits. J Happiness Stud 16 , 655–668 (2014).

Nilsen, T. S. et al . The Norwegian Twin Registry from a Public Health Perspective: A Research Update. Twin Res Hum Genet 16 , 285–295 (2013).

Harris, J. R., Magnus, P. & Tambs, K. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health twin program of research: An update. Twin Res Hum Genet 9 , 858–864 (2006).

Magnus, P., Berg, K. & Nance, W. E. Predicting Zygosity in Norwegian Twin Pairs Born 1915–1960. Clin Genet 24 , 103–112 (1983).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49 , 71–75 (1985).

Pavot, W. & Diener, E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psycholog y . 3 , pp (2008).

Pavot, W. & Diener, E. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment 5 , 164–172 (1993).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Stability and change in personality assessment: The Revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. Journal of Personality Assessment 68 , 86–94 (1997).

Loehlin, J. C. The Cholesky approach: A cautionary note. Behavior Genetics 26 , 65–69 (1996).

Neale, M. C. & Cardon, L. R. Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families . (Kluwer Academic; 1992., 1992).