The Psychology Behind Helping and Prosocial Behaviors: An Examination from Intention to Action

- First Online: 01 January 2009

Cite this chapter

- Jennifer L. Silva 2 ,

- Loren D. Marks Ph.D. &

- Katie E. Cherry 3

1800 Accesses

16 Citations

6 Altmetric

When disasters strike, many people rise to the challenge of providing immediate assistance to those whose lives are in peril. The spectrum of helping behaviors to counter the devastating effects of a natural disaster is vast and can be seen on many levels, from concerned individuals and community groups to volunteer organizations and larger civic entities. In this chapter, we examine the psychology of helping in relation to natural disasters. Definitions of helping behaviors, why we help, and risks of helping others are discussed first. Next, we discuss issues specific to natural disasters and life span considerations, noting the developmental progression of age-related, altruistic motivations. We present a qualitative analysis of helping behaviors based on interviews with participants in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study (LHAS; see Cherry, Silva, & Galea, Chapter 9). These data show that some people directly engaged in helping behaviors to further the relief effort after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, while others spoke of helping indirectly through their associations with local churches and faith-based organizations that provided storm relief. Implications for helping behaviors and intentions to help in a post-disaster situation are considered.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation . New York: Basic Books.

Google Scholar

Batson, C. D., & Coke, J. S. (1981). Empathy: A source of altruistic motivation for helping? In P. Rushton & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Altruism and helping behavior: Social, personality, and developmental perspectives (pp. 167–187). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Batson, C. D., Duncan, B. D., Ackerman, P., Buckley, T., & Birch, K. (1981). Is empathic emotion a source of altruistic motivation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40 , 290–302.

Article Google Scholar

Batson, C. D., Fultz, J., & Schoenrade, P. (1987). Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55 , 19–39.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Beyerlein, K., & Sikkink, D. (2008). Sorrow and solidarity: Why Americans volunteered for 9/11 relief efforts. Social Problems, 55 , 190–215.

Black, B., & Kovacs, P. J. (1999). Age-related variation in roles performed by hospice volunteers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 18 , 479–497.

Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T. R. (2001). Justice and empathy: What motivates people to help others? In M. Ross & D. T. Miller (Eds.), The justice motive in everyday life (pp. 226–250). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. I). London: Hogarth.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory . London: Routledge Press.

Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2002). Approximate perspective on reciprocal altruism. Human Nature, 13 , 129–152.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2007). Volunteering in the United States, 2007 . Retrieved September 30, 2008, from, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/volun.nr0.htm

Burnstein, E., Crandall, C., & Kitayama, S. (1994). Some neo-Darwinian decision rules for altruism: Weighing cues for inclusive fitness as a function of the biological importance of the decision. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67 , 773–789.

Cherry, K. E., Galea, S., & Silva, J. L. (2008). Successful aging and natural disasters: Role of adaptation and resiliency in late life. In M. Hersen & A. M. Gross (Eds.), Handbook of clinical psychology (Vol. 1, pp 810–833). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cherry, K. E., Galea, S., Su, L. J., Welsh, D. A., Jazwinski, S. M., Silva, J. L., et al. (2009). Cognitive and psychosocial consequences of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on middle aged, older, and oldest-old adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study (LHAS). Journal of Applied Social Psychology (in press).

Choi, L. H. (2003). Factors affecting volunteerism among older adults. The Journal of Applied Gerontology, 22 , 179–196.

Cialdini, R. B., Baumann, D. J., & Kenrick, D. T. (1981). Insights from sadness: A three-step model of the development of altruism as hedonism. Developmental Review, 1 , 207–223.

Cialdini, R. B., Kenriek, D. X., & Baumann, D. J. (1982). Effects of mood on prosocial behavior in children and adults. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The development of prosocial behavior (pp.339–359). New York: Academic Press.

Cialdini, R. B., Schaller, M., Houlihan, D., Arps, K., Fultz, J., & Beaman, A. (1987). Empathy-based helping: Is it selflessly or selfishly motivated? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 , 749–758.

Coke, J. S., Batson, C. D., & McDavis, K. (1978). Empathic mediation of helping: A two-stage model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36 , 752–766.

Cunningham, M. R., Jegerski, J., Gruder, C. L., & Barbee, A. P. (1995). Helping in different social relationships: Charity begins at home . Unpublished manuscript, University of Louisville.

Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., Schroeder, D. A., & Penner, L. A. (2006). The social psychology of prosocial behavior . New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1998). Prosocial development. Handbook of child psychology (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 701–778). New York: Wiley and Sons.

Fryock, C. D., & Dorton, A. M. (1994). Unretirement: A career guide for the retired…the soon-to be retired…the never-want-to-be retired . New York: American Management Assoc.

Fultz, J., Bateon, C. D., Fortenbach, V. A., McCarthy, P. M., & Varoey, L. L. (1986). Social evaluation and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50 , 761–769.

Fritz, C., & Williams, H. 1957. The human being in disasters: A research perspective. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 309 , 42–51.

Hamilton, W. D. (1963). The evolution of altruistic behavior. American Naturalist, 97 , 354–356.

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour: I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7 , 1–16 and 17–52.

Harris, M. B., Benson, S. B., & Hall, C. L. (1975). The effects of confession on altruism. Journal of Social Psychology, 96 , 187–192.

Hedge, A., & Yousif, Y. H. (1992). Effects of urban size, urgency, and cost on helpfulness: A cross-cultural comparison between the United Kingdom and the Sudan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 23 , 107–115.

Hertzog, A. R., & Morgan, J. S. (1993). Formal volunteer work among older Americans. In S. A. Bass, F. G. Caro, & Y. P. Chen (Eds.), Achieving a productive aging society (pp. 119–12). Westport, CT: Auburn House Press.

Hood, K. E., Greenberg, G., & Tobach, E. (1995). Behavioral development: Concepts of approach-withdrawal and integrative levels. The T. C. Schneirla Conference Series, Vol. 5 . New York: Garland.

Indiana University Center on Philanthropy. (2007). Giving in the aftermath of the gulf coast hurricanes. Retrieved on September 29, 2008, from, http://foundationcenter.org/gainknowledge/research/pdf/katrina_report_2007.pdf

Johnson, K., Beebe, M. T., Mortimer, J. T., & Snyder, M. (1998). Volunteerism in adolescence: A process perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8 , 309–332.

Kouri, M. K. (1990). Volunteerism and older adults . Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Press.

Latané, B., & Darley, J. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn't he help ? New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts Press.

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion . New York: Plenum.

Lerner, M. J. (1997). What does the belief in a just world protect us from: The dread of death or the fear of understanding suffering? Psychological Inquiry, 8 , 29.

Lerner, M. J., & Simmons, C. H. (1966). The observer’s reaction to the ‘innocent victim’: Compassion or rejection? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 203–210.

Litvack-Miller, W., McDougall, D., & Romney, D. M. (1997). The structure of empathy during middle childhood and its relationship to prosocial behaviour. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs, 123 , 303–325.

Madsen, E. A., Richard, J., Fieldman, G., Plotkin, H. C., Dunbar, R. I. M., Richardson, J., et al. (2007). Kinship and altruism: A cross-cultural study. British Journal of Psychology, 98 , 339–359.

Michel, L. (2007). Personal responsibility and volunteering after a natural disaster: The case of hurricane Katrina. Sociological Spectrum, 27 , 633–652.

Moore, C. W., & Allen, J. P. (1996). The effects of volunteering on the young volunteer. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 17 , 231–258.

Morrow-Howell, N., & Tang, F. (2003). Elder service and youth service in comparative perspective: Nature, activities, and impacts . St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Development [Working paper].

Omoto, A. M., Synder, M., & Martino, S. C. (2000). Volunteerism and the life course: Investing age-related agendas for action. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 22 , 181–197.

Park, G. J. (2002). Factors influencing the meaning of life for middle-aged women. Korean Journal of Women’s Health Nursing, 2 , 232–243.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Character strengths before and after September 11. Psychological Science, 14 , 381–384.

Piliavin, J., Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Clark, R. (1981). Emergency intervention . New York: Academic Press.

Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenburg, J. (2003 ). In the wake of 9/11: The psychology of terror . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Book Google Scholar

Rapoport, A., & Chammah, A. M. (1965). Prisoner's dilemma . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ridley, M. (2003). Nature via nurture: Genes, experience, and what makes us human . New York: Harper Collins Press.

Rubin, Z., & Peplau, L. A. (1975). Who believes in a just world? Journal of Social Issues, 31 , 65–89.

Schaller, M., & Cialdini, R. B. (1988). The economics of empathic helping: Support for a mood management motive. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 24 , 163–181.

Tang, F. (2006). What resources are needed for volunteerism? A life course perspective. The Journal of Applied Gerontology, 25 , 375–390.

Toi, M., & Batson, C. D. (1982). More evidence that empathy is a source of altruistic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43 , 281–292.

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46 , 35–57.

Trivers, R. L. (1983). The evolution of cooperation. In D. L. Bridgeman (Ed.), The nature of prosocial development . New York: Academic Press.

Tyler , T. R., Boeckmann, R. J., Smith, H. J., & Huo, Y. J. (1997). Social justice in a diverse society . Boulder: Westview.

Wallach, M. A., & Wallach, L. (1983). Psychology is sanction for selfishness: The error of egoism in theory and therapy . New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Wilkinson, G. S. (1984). Reciprocal food sharing in the vampire bat. Nature, 308 , 181–184.

Yates, M., & Youniss, J. (1996). A developmental perspective on community service in adolescence. Social Development, 5 , 85–115.

Download references

Acknowledgment

We thank Tracey Frias, Miranda Melancon, and Zia McWilliams for their assistance with data summary and qualitative analyses. We also thank Erin C. Goforth for her helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

This research was supported by grants from the Louisiana Board of Regents through the Millennium Trust Health Excellence Fund (HEF[2001-06]-02) and the National Institute on Aging P01 AG022064. This support is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, 70803-5501, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

Jennifer L. Silva

Louisiana State University, 70803-5501, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

Katie E. Cherry

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katie E. Cherry .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Silva, J.L., Marks, L.D., Cherry, K.E. (2009). The Psychology Behind Helping and Prosocial Behaviors: An Examination from Intention to Action. In: Cherry, K. (eds) Lifespan Perspectives on Natural Disasters. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0393-8_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0393-8_11

Published : 08 June 2009

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-0392-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-0393-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3 How the Social Context Influences Helping

Learning objective.

- Review Bibb Latané and John Darley’s model of helping behavior and indicate the social psychological variables that influence each stage.

Although emotional responses such as guilt, personal distress, and empathy are important determinants of altruism, it is the social situation itself—the people around us when we are deciding whether or not to help—that has perhaps the most important influence on whether and when we help.

Consider the unusual case of the killing of 28-year-old Katherine “Kitty” Genovese in New York City at about 3:00 a.m. on March 13, 1964. Her attacker, Winston Moseley, stabbed and sexually assaulted her within a few yards of her apartment building in the borough of Queens. During the struggle with her assailant, Kitty screamed, “Oh my God! He stabbed me! Please help me!” But no one responded. The struggle continued; Kitty broke free from Moseley, but he caught her again, stabbed her several more times, and eventually killed her.

The murder of Kitty Genovese shocked the nation, in large part because of the (often inaccurate) reporting of it. Stories about the killing, in the New York Times and other papers, indicated that as many as 38 people had overheard the struggle and killing, that none of them had bothered to intervene, and that only one person had even called the police, long after Genovese was dead.

Although these stories about the lack of concern by people in New York City proved to be false (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007), they nevertheless led many people to think about the variables that might lead people to help or, alternatively, to be insensitive to the needs of others. Was this an instance of the uncaring and selfish nature of human beings? Or was there something about this particular social situation that was critical? It turns out, contrary to your expectations I would imagine, that having many people around during an emergency can in fact be the opposite of helpful—it can reduce the likelihood that anyone at all will help.

Latané and Darley’s Model of Helping

Two social psychologists, Bibb Latané and John Darley, found themselves particularly interested in, and concerned about, the Kitty Genovese case. As they thought about the stories that they had read about it, they considered the nature of emergency situations, such as this one. They realized that emergencies are unusual and that people frequently do not really know what to do when they encounter one. Furthermore, emergencies are potentially dangerous to the helper, and it is therefore probably pretty amazing that anyone helps at all.

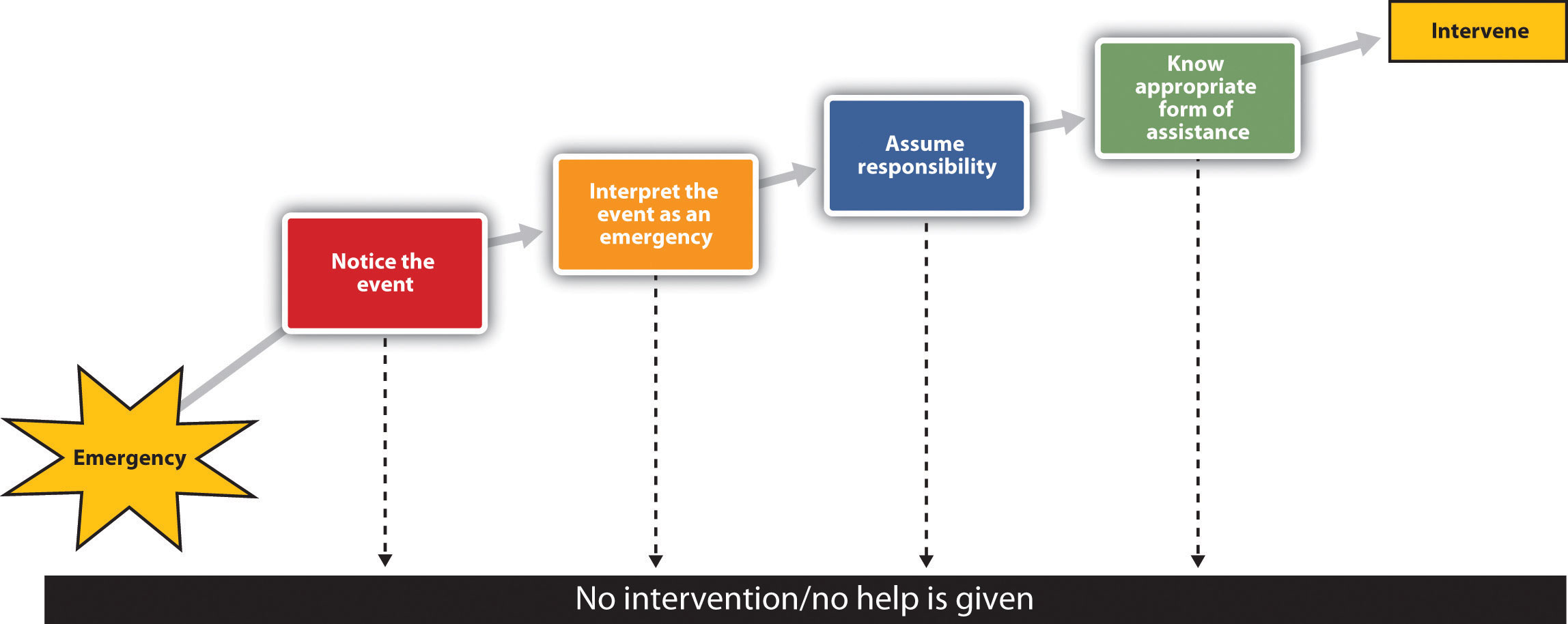

Figure 9.5 Latané and Darley’s Stages of Helping

To better understand the processes of helping in an emergency, Latané and Darley developed a model of helping that took into consideration the important role of the social situation. Their model, which is shown in Figure 9.5 “Latané and Darley’s Stages of Helping” , has been extensively tested in many studies, and there is substantial support for it.

Latané and Darley thought that the first thing that had to happen in order for people to help is that they had to notice the emergency. This seems pretty obvious, but it turns out that the social situation has a big impact on noticing an emergency. Consider, for instance, people who live in a large city such as New York City, Bangkok, or Beijing. These cities are big, noisy, and crowded—it seems like there are a million things going at once. How could people living in such a city even notice, let alone respond to, the needs of all the people around them? They are simply too overloaded by the stimuli in the city (Milgram, 1970).

Many studies have found that people who live in smaller and less dense rural towns are more likely to help than those who live in large, crowded, urban cities (Amato, 1983; Levine, Martinez, Brase, & Sorenson, 1994). Although there are a lot of reasons for such differences, just noticing the emergency is critical. When there are more people around, it is less likely that the people notice the needs of others.

You may have had an experience that demonstrates the influence of the social situation on noticing. Imagine that you have lived with a family or a roommate for a while, but one night you find yourself alone in your house or apartment because your housemates are staying somewhere else that night. If you are like me, I bet you found yourself hearing sounds that you never heard before—and they might have made you pretty nervous. Of course the sounds were always there, but when other people were around you, you were simply less alert to them. The presence of others can divert our attention from the environment—it’s as if we are unconsciously, and probably quite mistakenly, counting on the others to take care of things for us.

Latané and Darley (1968) wondered if they could examine this phenomenon experimentally. To do so, they simply asked their research participants to complete a questionnaire in a small room. Some of the participants completed the questionnaire alone, while others completed the questionnaire in small groups in which two other participants were also working on questionnaires.

A few minutes after the participants had begun the questionnaires, the experimenters started to release some white smoke into the room through a vent in the wall while they watched through a one-way mirror. The smoke got thicker as time went on, until it filled the room. The experimenters timed how long it took before the first person in the room looked up and noticed the smoke. The people who were working alone noticed the smoke in about 5 seconds, and within 4 minutes most of the participants who were working alone had taken some action. But what about the participants working in groups of three? Although we would certainly expect that having more people around would increase the likelihood that someone would notice the smoke, on average, the first person in the group conditions did not notice the smoke until over 20 seconds had elapsed. And although 75% of the participants who were working alone reported the smoke within 4 minutes, the smoke was reported in only 12% of the three-person groups by that time. In fact, in only three of the eight three-person groups did anyone report the smoke at all, even after it had entirely filled the room!

Interpreting

Even if we notice an emergency, we might not interpret it as one. The problem is that events are frequently ambiguous, and we must interpret them to understand what they really mean. Furthermore, we often don’t see the whole event unfolding, so it is difficult to get a good handle on it. Is a man holding an iPod and running away from a group of pursuers a criminal who needs to be apprehended, or is this just a harmless prank? Were the cries of Kitty Genovese really calls for help, or were they simply an argument with a boyfriend? It’s hard for us to tell when we haven’t seen the whole event (Piliavin, Piliavin, & Broll, 1976). Moreover, because emergencies are rare and because we generally tend to assume that events are benign, we may be likely to treat ambiguous cases as not being emergencies.

The problem is compounded when others are present because when we are unsure how to interpret events we normally look to others to help us understand them (this is informational social influence). However, the people we are looking toward for understanding are themselves unsure how to interpret the situation, and they are looking to us for information at the same time we are looking to them.

When we look to others for information we may assume that they know something that we do not know. This is often a mistake, because all the people in the situation are doing the same thing. None of us really know what to think, but at the same time we assume that the others do know. Pluralistic ignorance occurs when people think that others in their environment have information that they do not have and when they base their judgments on what they think the others are thinking .

Pluralistic ignorance seems to have been occurring in Latané and Darley’s studies, because even when the smoke became really heavy in the room, many people in the group conditions did not react to it. Rather, they looked at each other, and because nobody else in the room seemed very concerned, they each assumed that the others thought that everything was all right. You can see the problem—each bystander thinks that other people aren’t acting because they don’t see an emergency. Of course, everyone is confused, but believing that the others know something that they don’t, each observer concludes that help is not required.

Pluralistic ignorance is not restricted to emergency situations (Miller, Turnbull, & McFarland, 1988; Suls & Green, 2003). Maybe you have had the following experience: You are in one of your classes and the instructor has just finished a complicated explanation. He is unsure whether the students are up to speed and asks, “Are there any questions?” All the class members are of course completely confused, but when they look at each other, nobody raises a hand in response. So everybody in the class (including the instructor) assumes that everyone understands the topic perfectly. This is pluralistic ignorance at its worst—we are all assuming that others know something that we don’t, and so we don’t act. The moral to instructors in this situation is clear: Wait until at least one student asks a question. The moral for students is also clear: Ask your question! Don’t think that you will look stupid for doing so—the other students will probably thank you.

Taking Responsibility

Even if we have noticed the emergency and interpret it as being one, this does not necessarily mean that we will come to the rescue of the other person. We still need to decide that it is our responsibility to do something. The problem is that when we see others around, it is easy to assume that they are going to do something and that we don’t need to do anything. Diffusion of responsibility occurs when we assume that others will take action and therefore we do not take action ourselves . The irony of course is that people are more likely to help when they are the only ones in the situation than they are when there are others around.

Darley and Latané (1968) had study participants work on a communication task in which they were sharing ideas about how to best adjust to college life with other people in different rooms using an intercom. According to random assignment to conditions, each participant believed that he or she was communicating with either one, two, or five other people, who were in either one, two, or five other rooms. Each participant had an initial chance to give his opinions over the intercom, and on the first round one of the other people (actually a confederate of the experimenter) indicated that he had an “epileptic-like” condition that had made the adjustment process very difficult for him. After a few minutes, the subject heard the experimental confederate say,

I-er-um-I think I-I need-er-if-if could-er-er-somebody er-er-er-er-er-er-er give me a liltle-er-give me a little help here because-er-I-er-I’m-er-er having a-a-a real problcm-er-right now and I-er-if somebody could help me out it would-it would-er-er s-s-sure be-sure be good…because there-er-er-a cause I-er-I-uh-I’ve got a-a one of the-er-sei er-er-things coming on and-and-and I could really-er-use some help so if somebody would-er-give me a little h-help-uh-er-er-er-er-er c-could somebody-er-er-help-er-uh-uh-uh (choking sounds).…I’m gonna die-er-er-I’m…gonna die-er-help-er-er-seizure-er- (chokes, then quiet). (Darley & Latané, 1968, p. 379)

As you can see in Table 9.2 “Effects of Group Size on Likelihood and Speed of Helping” , the participants who thought that they were the only ones who knew about the emergency (because they were only working with one other person) left the room quickly to try to get help. In the larger groups, however, participants were less likely to intervene and slower to respond when they did. Only 31% of the participants in the largest groups responded by the end of the 6-minute session.

You can see that the social situation has a powerful influence on helping. We simply don’t help as much when other people are with us.

Table 9.2 Effects of Group Size on Likelihood and Speed of Helping

Perhaps you have noticed diffusion of responsibility if you have participated in an Internet users group where people asked questions of the other users. Did you find that it was easier to get help if you directed your request to a smaller set of users than when you directed it to a larger number of people? Consider the following: In 1998, Larry Froistad, a 29-year-old computer programmer, sent the following message to the members of an Internet self-help group that had about 200 members. “Amanda I murdered because her mother stood between us…when she was asleep, I got wickedly drunk, set the house on fire, went to bed, listened to her scream twice, climbed out the window and set about putting on a show of shock and surprise.” Despite this clear online confession to a murder, only three of the 200 newsgroup members reported the confession to the authorities (Markey, 2000).

To study the possibility that this lack of response was due to the presence of others, the researchers (Markey, 2000) conducted a field study in which they observed about 5,000 participants in about 400 different chat groups. The experimenters sent a message to the group, from either a male (JakeHarmen) or female (SuzyHarmen) screen name. Help was sought by either asking all the participants in the chat group, “Can anyone tell me how to look at someone’s profile?” or by randomly selecting one participant and asking “[name of selected participant], can you tell me how to look at someone’s profile?” The experimenters recorded the number of people present in the chat room, which ranged from 2 to 19, and then waited to see how long it took before a response was given.

It turned out that the gender of the person requesting help made no difference, but that addressing to a single person did. Assistance was received more quickly when help was asked for by specifying a participant’s name (in only about 37 seconds) than when no name was specified (51 seconds). Furthermore, a correlational analysis found that when help was requested without specifying a participant’s name, there was a significant negative correlation between the number of people currently logged on in the group and the time it took to respond to the request.

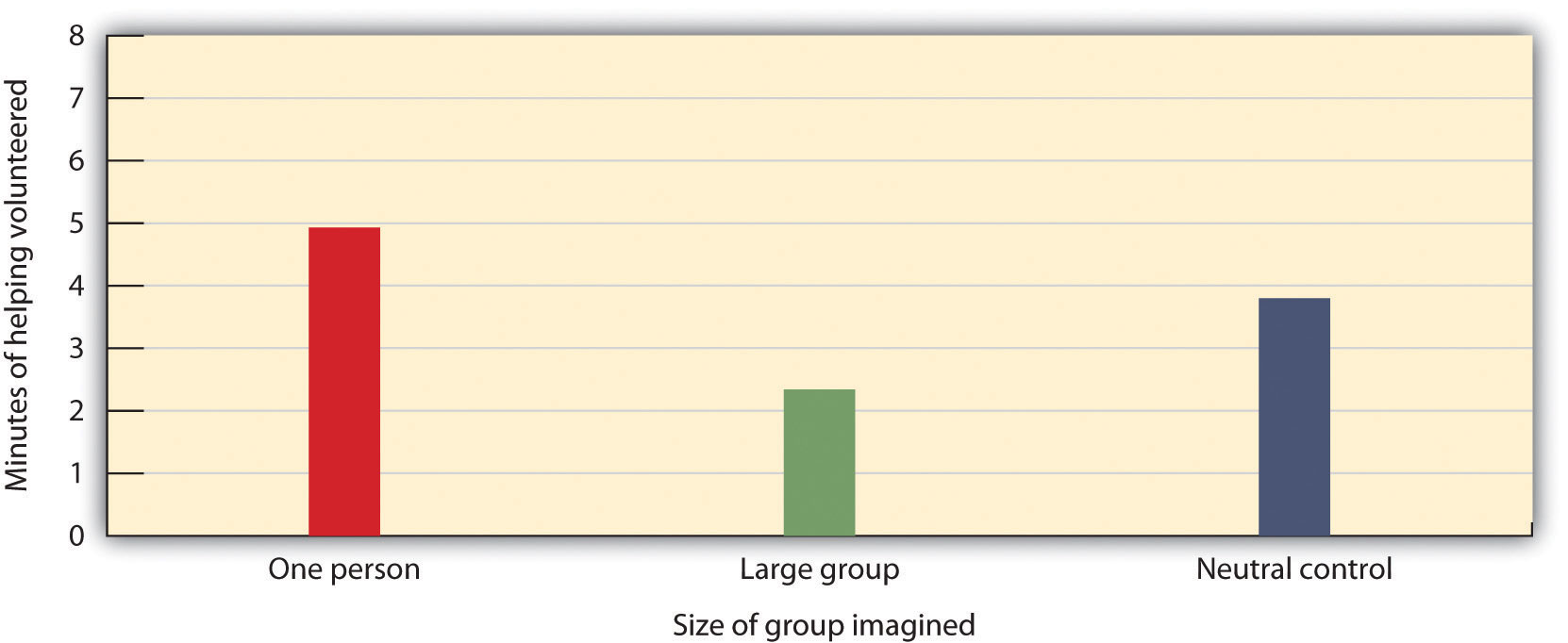

Garcia, Weaver, Moskowitz, and Darley (2002) found that the presence of others can promote diffusion of responsibility even if those other people are only imagined. In these studies the researchers had participants read one of three possible scenarios that manipulated whether participants thought about dining out with 10 friends at a restaurant ( group condition ) or whether they thought about dining at a restaurant with only one other friend ( one-person condition ). Participants in the group condition were asked to “Imagine you won a dinner for yourself and 10 of your friends at your favorite restaurant.” Participants in the one-person condition were asked to “Imagine you won a dinner for yourself and a friend at your favorite restaurant.”

After reading one of the scenarios, the participants were then asked to help with another experiment supposedly being conducted in another room. Specifically, they were asked: “How much time are you willing to spend on this other experiment?” At this point, participants checked off one of the following minute intervals: 0 minutes , 2 minutes , 5 minutes , 10 minutes , 15 minutes , 20 minutes , 25 minutes , and 30 minutes .

Figure 9.6 Helping as a Function of Imagined Social Context

Garcia et al. (2002) found that the presence of others reduced helping, even when those others were only imagined.

As you can see in Figure 9.6 “Helping as a Function of Imagined Social Context” , simply imagining that they were in a group or alone had a significant effect on helping, such that those who imagined being with only one other person volunteered to help for more minutes than did those who imagined being in a larger group.

Implementing Action

The fourth step in the helping model is knowing how to help. Of course, for many of us the ways to best help another person in an emergency are not that clear; we are not professionals and we have little training in how to help in emergencies. People who do have training in how to act in emergencies are more likely to help, whereas the rest of us just don’t know what to do and therefore may simply walk by. On the other hand, today most people have cell phones, and we can do a lot with a quick call. In fact, a phone call made in time might have saved Kitty Genovese’s life. The moral: You might not know exactly what to do, but you may well be able to contact someone else who does.

Latané and Darley’s decision model of bystander intervention has represented an important theoretical framework for helping us understand the role of situational variables on helping. Whether or not we help depends on the outcomes of a series of decisions that involve noticing the event, interpreting the situation as one requiring assistance, deciding to take personal responsibility, and deciding how to help.

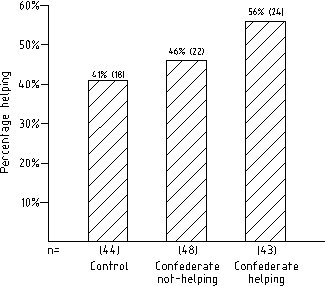

Fischer et al. (2011) recently analyzed data from over 105 studies using over 7,500 participants who had been observed helping (or not helping) in situations in which they were alone or with others. They found significant support for the idea that people helped more when fewer others were present. And supporting the important role of interpretation, they also found that the differences were smaller when the need for helping was clear and dangerous and thus required little interpretation. They also found that there were at least some situations (such as when bystanders were able to help provide needed physical assistance) in which having other people around increased helping.

Although the Latané and Darley model was initially developed to understand how people respond in emergencies requiring immediate assistance, aspects of the model have been successfully applied to many other situations, ranging from preventing someone from driving drunk to making a decision about whether to donate a kidney to a relative (Schroeder, Penner, Dovidio, & Piliavin, 1995).

Key Takeaways

- The social situation has an important influence on whether or not we help.

- Latané and Darley’s decision model of bystander intervention has represented an important theoretical framework for helping us understand the role of situational variables on helping. According to the model, whether or not we help depends on the outcomes of a series of decisions that involve noticing the event, interpreting the situation as one requiring assistance, deciding to take personal responsibility, and implementing action.

- Latané and Darley’s model has received substantial empirical support and has been applied not only to helping in emergencies but to other helping situations as well.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Analyze the Kitty Genovese incident in terms of the Latané and Darley model of helping. Which factors do you think were most important in preventing helping?

- Recount a situation in which you did or did not help, and consider how that decision might have been influenced by the variables specified in Latané and Darley’s model.

Amato, P. R. (1983). The helpfulness of urbanites and small town dwellers: A test between two broad theoretical positions. Australian Journal of Psychology, 35 (2), 233–243.

Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 (4, Pt.1), 377–383.

Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D.,…Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137 (4), 517–537.

Garcia, S. M., Weaver, K., Moskowitz, G. B., & Darley, J. M. (2002). Crowded minds: The implicit bystander effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (4), 843–853.

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10 (3), 215–221.

Levine, R. V., Martinez, T. S., Brase, G., & Sorenson, K. (1994). Helping in 36 U.S. cities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67 (1), 69–82.

Manning, R., Levine, M., & Collins, A. (2007). The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses. American Psychologist, 62 (6), 555–562.

Markey, P. M. (2000). Bystander intervention in computer-mediated communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 16 (2), 183–188.

Milgram, S. (1970). The experience of living in cities. Science, 167 (3924), 1461–1468.

Miller, D. T., Turnbull, W., & McFarland, C. (1988). Particularistic and universalistic evaluation in the social comparison process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 908–917.

Piliavin, J. A., Piliavin, I. M., & Broll, L. (1976). Time of arrival at an emergency and likelihood of helping. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2 (3), 273–276.

Schroeder, D. A., Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., & Piliavin, J. A. (1995). The psychology of helping and altruism: Problems and puzzles . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Suls, J., & Green, P. (2003). Pluralistic ignorance and college student perceptions of gender-specific alcohol norms. Health Psychology, 22 (5), 479–486.

Principles of Social Psychology Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

12: Altruism

Helping and Prosocial Behavior

By Dennis L. Poepsel and David A. Schroeder Truman State University, University of Arkansas

People often act to benefit other people, and these acts are examples of prosocial behavior. Such behaviors may come in many guises: helping an individual in need; sharing personal resources; volunteering time, effort, and expertise; cooperating with others to achieve some common goals. The focus of this module is on helping—prosocial acts in dyadic situations in which one person is in need and another provides the necessary assistance to eliminate the other’s need. Although people are often in need, help is not always given. Why not? The decision of whether or not to help is not as simple and straightforward as it might seem, and many factors need to be considered by those who might help. In this module, we will try to understand how the decision to help is made by answering the question: Who helps when and why?

Learning Objectives

- Learn which situational and social factors affect when a bystander will help another in need.

- Understand which personality and individual difference factors make some people more likely to help than others.

- Discover whether we help others out of a sense of altruistic concern for the victim, for more self-centered and egoistic motives, or both.

Introduction

Go to YouTube and search for episodes of “Primetime: What Would You Do?” You will find video segments in which apparently innocent individuals are victimized, while onlookers typically fail to intervene. The events are all staged, but they are very real to the bystanders on the scene. The entertainment offered is the nature of the bystanders’ responses, and viewers are outraged when bystanders fail to intervene. They are convinced that they would have helped. But would they? Viewers are overly optimistic in their beliefs that they would play the hero. Helping may occur frequently, but help is not always given to those in need. So when do people help, and when do they not? All people are not equally helpful— who helps? Why would a person help another in the first place? Many factors go into a person’s decision to help—a fact that the viewers do not fully appreciate. This module will answer the question: Who helps when and why?

When Do People Help?

Social psychologists are interested in answering this question because it is apparent that people vary in their tendency to help others. In 2010 for instance, Hugo Alfredo Tale-Yax was stabbed when he apparently tried to intervene in an argument between a man and woman. As he lay dying in the street, only one man checked his status, but many others simply glanced at the scene and continued on their way. (One passerby did stop to take a cellphone photo, however.) Unfortunately, failures to come to the aid of someone in need are not unique, as the segments on “What Would You Do?” show. Help is not always forthcoming for those who may need it the most. Trying to understand why people do not always help became the focus of bystander intervention research (e.g., Latané & Darley, 1970).

To answer the question regarding when people help, researchers have focused on

- how bystanders come to define emergencies,

- when they decide to take responsibility for helping , and

- how the costs and benefits of intervening affect their decisions of whether to help.

Defining the situation: The role of pluralistic ignorance

The decision to help is not a simple yes/no proposition. In fact, a series of questions must be addressed before help is given—even in emergencies in which time may be of the essence. Sometimes help comes quickly; an onlooker recently jumped from a Philadelphia subway platform to help a stranger who had fallen on the track. Help was clearly needed and was quickly given. But some situations are ambiguous, and potential helpers may have to decide whether a situation is one in which help, in fact, needs to be given.

To define ambiguous situations (including many emergencies), potential helpers may look to the action of others to decide what should be done. But those others are looking around too, also trying to figure out what to do. Everyone is looking, but no one is acting! Relying on others to define the situation and to then erroneously conclude that no intervention is necessary when help is actually needed is called pluralistic ignorance (Latané & Darley, 1970). When people use the inactions of others to define their own course of action, the resulting pluralistic ignorance leads to less help being given.

Do I have to be the one to help?: Diffusion of responsibility

Simply being with others may facilitate or inhibit whether we get involved in other ways as well. In situations in which help is needed, the presence or absence of others may affect whether a bystander will assume personal responsibility to give the assistance. If the bystander is alone, personal responsibility to help falls solely on the shoulders of that person. But what if others are present? Although it might seem that having more potential helpers around would increase the chances of the victim getting help, the opposite is often the case. Knowing that someone else could help seems to relieve bystanders of personal responsibility, so bystanders do not intervene. This phenomenon is known as diffusion of responsibility (Darley & Latané, 1968).

On the other hand, watch the video of the race officials following the 2013 Boston Marathon after two bombs exploded as runners crossed the finish line. Despite the presence of many spectators, the yellow-jacketed race officials immediately rushed to give aid and comfort to the victims of the blast. Each one no doubt felt a personal responsibility to help by virtue of their official capacity in the event; fulfilling the obligations of their roles overrode the influence of the diffusion of responsibility effect.

There is an extensive body of research showing the negative impact of pluralistic ignorance and diffusion of responsibility on helping (Fisher et al., 2011), in both emergencies and everyday need situations. These studies show the tremendous importance potential helpers place on the social situation in which unfortunate events occur, especially when it is not clear what should be done and who should do it. Other people provide important social information about how we should act and what our personal obligations might be. But does knowing a person needs help and accepting responsibility to provide that help mean the person will get assistance? Not necessarily.

The costs and rewards of helping

The nature of the help needed plays a crucial role in determining what happens next. Specifically, potential helpers engage in a cost–benefit analysis before getting involved (Dovidio et al., 2006). If the needed help is of relatively low cost in terms of time, money, resources, or risk, then help is more likely to be given. Lending a classmate a pencil is easy; confronting someone who is bullying your friend is an entirely different matter. As the unfortunate case of Hugo Alfredo Tale-Yax demonstrates, intervening may cost the life of the helper.

The potential rewards of helping someone will also enter into the equation, perhaps offsetting the cost of helping. Thanks from the recipient of help may be a sufficient reward. If helpful acts are recognized by others, helpers may receive social rewards of praise or monetary rewards. Even avoiding feelings of guilt if one does not help may be considered a benefit. Potential helpers consider how much helping will cost and compare those costs to the rewards that might be realized; it is the economics of helping. If costs outweigh the rewards, helping is less likely. If rewards are greater than cost, helping is more likely.

Do you know someone who always seems to be ready, willing, and able to help? Do you know someone who never helps out? It seems there are personality and individual differences in the helpfulness of others. To answer the question of who chooses to help, researchers have examined 1) the role that sex and gender play in helping, 2) what personality traits are associated with helping, and 3) the characteristics of the “prosocial personality.”

Who are more helpful—men or women?

In terms of individual differences that might matter, one obvious question is whether men or women are more likely to help. In one of the “What Would You Do?” segments, a man takes a woman’s purse from the back of her chair and then leaves the restaurant. Initially, no one responds, but as soon as the woman asks about her missing purse, a group of men immediately rush out the door to catch the thief. So, are men more helpful than women? The quick answer is “not necessarily.” It all depends on the type of help needed. To be very clear, the general level of helpfulness may be pretty much equivalent between the sexes, but men and women help in different ways (Becker & Eagly, 2004; Eagly & Crowley, 1986). What accounts for these differences?

Two factors help to explain sex and gender differences in helping. The first is related to the cost–benefit analysis process discussed previously. Physical differences between men and women may come into play (e.g., Wood & Eagly, 2002); the fact that men tend to have greater upper body strength than women makes the cost of intervening in some situations less for a man. Confronting a thief is a risky proposition, and some strength may be needed in case the perpetrator decides to fight. A bigger, stronger bystander is less likely to be injured and more likely to be successful.

The second explanation is simple socialization. Men and women have traditionally been raised to play different social roles that prepare them to respond differently to the needs of others, and people tend to help in ways that are most consistent with their gender roles. Female gender roles encourage women to be compassionate, caring, and nurturing; male gender roles encourage men to take physical risks, to be heroic and chivalrous, and to be protective of those less powerful. As a consequence of social training and the gender roles that people have assumed, men may be more likely to jump onto subway tracks to save a fallen passenger, but women are more likely to give comfort to a friend with personal problems (Diekman & Eagly, 2000; Eagly & Crowley, 1986). There may be some specialization in the types of help given by the two sexes, but it is nice to know that there is someone out there—man or woman—who is able to give you the help that you need, regardless of what kind of help it might be.

A trait for being helpful: Agreeableness

Graziano and his colleagues (e.g., Graziano & Tobin, 2009; Graziano, Habishi, Sheese, & Tobin, 2007) have explored how agreeableness —one of the Big Five personality dimensions (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1988)—plays an important role in prosocial behavior . Agreeableness is a core trait that includes such dispositional characteristics as being sympathetic, generous, forgiving, and helpful, and behavioral tendencies toward harmonious social relations and likeability. At the conceptual level, a positive relationship between agreeableness and helping may be expected, and research by Graziano et al. (2007) has found that those higher on the agreeableness dimension are, in fact, more likely than those low on agreeableness to help siblings, friends, strangers, or members of some other group. Agreeable people seem to expect that others will be similarly cooperative and generous in interpersonal relations, and they, therefore, act in helpful ways that are likely to elicit positive social interactions.

Searching for the prosocial personality

Rather than focusing on a single trait, Penner and his colleagues (Penner, Fritzsche, Craiger, & Freifeld, 1995; Penner & Orom, 2010) have taken a somewhat broader perspective and identified what they call the prosocial personality orientation . Their research indicates that two major characteristics are related to the prosocial personality and prosocial behavior. The first characteristic is called other-oriented empathy : People high on this dimension have a strong sense of social responsibility, empathize with and feel emotionally tied to those in need, understand the problems the victim is experiencing, and have a heightened sense of moral obligation to be helpful. This factor has been shown to be highly correlated with the trait of agreeableness discussed previously. The second characteristic, helpfulness , is more behaviorally oriented. Those high on the helpfulness factor have been helpful in the past, and because they believe they can be effective with the help they give, they are more likely to be helpful in the future.

Finally, the question of why a person would help needs to be asked. What motivation is there for that behavior? Psychologists have suggested that 1) evolutionary forces may serve to predispose humans to help others, 2) egoistic concerns may determine if and when help will be given, and 3) selfless, altruistic motives may also promote helping in some cases.

Evolutionary roots for prosocial behavior

Our evolutionary past may provide keys about why we help (Buss, 2004). Our very survival was no doubt promoted by the prosocial relations with clan and family members, and, as a hereditary consequence, we may now be especially likely to help those closest to us—blood-related relatives with whom we share a genetic heritage. According to evolutionary psychology, we are helpful in ways that increase the chances that our DNA will be passed along to future generations (Burnstein, Crandall, & Kitayama, 1994)—the goal of the “selfish gene” (Dawkins, 1976). Our personal DNA may not always move on, but we can still be successful in getting some portion of our DNA transmitted if our daughters, sons, nephews, nieces, and cousins survive to produce offspring. The favoritism shown for helping our blood relatives is called kin selection (Hamilton, 1964).

But, we do not restrict our relationships just to our own family members. We live in groups that include individuals who are unrelated to us, and we often help them too. Why? Reciprocal altruism (Trivers, 1971) provides the answer. Because of reciprocal altruism, we are all better off in the long run if we help one another. If helping someone now increases the chances that you will be helped later, then your overall chances of survival are increased. There is the chance that someone will take advantage of your help and not return your favors. But people seem predisposed to identify those who fail to reciprocate, and punishments including social exclusion may result (Buss, 2004). Cheaters will not enjoy the benefit of help from others, reducing the likelihood of the survival of themselves and their kin.

Evolutionary forces may provide a general inclination for being helpful, but they may not be as good an explanation for why we help in the here and now. What factors serve as proximal influences for decisions to help?

Egoistic motivation for helping

Most people would like to think that they help others because they are concerned about the other person’s plight. In truth, the reasons why we help may be more about ourselves than others: Egoistic or selfish motivations may make us help. Implicitly, we may ask, “What’s in it for me ?” There are two major theories that explain what types of reinforcement helpers may be seeking. The negative state relief model (e.g., Cialdini, Darby, & Vincent, 1973; Cialdini, Kenrick, & Baumann, 1982) suggests that people sometimes help in order to make themselves feel better. Whenever we are feeling sad, we can use helping someone else as a positive mood boost to feel happier. Through socialization, we have learned that helping can serve as a secondary reinforcement that will relieve negative moods (Cialdini & Kenrick, 1976).

The arousal: cost–reward model provides an additional way to understand why people help (e.g., Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, & Clark, 1981). This model focuses on the aversive feelings aroused by seeing another in need. If you have ever heard an injured puppy yelping in pain, you know that feeling, and you know that the best way to relieve that feeling is to help and to comfort the puppy. Similarly, when we see someone who is suffering in some way (e.g., injured, homeless, hungry), we vicariously experience a sympathetic arousal that is unpleasant, and we are motivated to eliminate that aversive state. One way to do that is to help the person in need. By eliminating the victim’s pain, we eliminate our own aversive arousal. Helping is an effective way to alleviate our own discomfort.

As an egoistic model, the arousal: cost–reward model explicitly includes the cost/reward considerations that come into play. Potential helpers will find ways to cope with the aversive arousal that will minimize their costs—maybe by means other than direct involvement. For example, the costs of directly confronting a knife-wielding assailant might stop a bystander from getting involved, but the cost of some indirect help (e.g., calling the police) may be acceptable. In either case, the victim’s need is addressed. Unfortunately, if the costs of helping are too high, bystanders may reinterpret the situation to justify not helping at all. For some, fleeing the situation causing their distress may do the trick (Piliavin et al., 1981).

The egoistically based negative state relief model and the arousal: cost–reward model see the primary motivation for helping as being the helper’s own outcome. Recognize that the victim’s outcome is of relatively little concern to the helper—benefits to the victim are incidental byproducts of the exchange (Dovidio et al., 2006). The victim may be helped, but the helper’s real motivation according to these two explanations is egoistic: Helpers help to the extent that it makes them feel better.

Altruistic help

Although many researchers believe that egoism is the only motivation for helping, others suggest that altruism —helping that has as its ultimate goal the improvement of another’s welfare—may also be a motivation for helping under the right circumstances. Batson (2011) has offered the empathy–altruism model to explain altruistically motivated helping for which the helper expects no benefits. According to this model, the key for altruism is empathizing with the victim, that is, putting oneself in the shoes of the victim and imagining how the victim must feel. When taking this perspective and having empathic concern , potential helpers become primarily interested in increasing the well-being of the victim, even if the helper must incur some costs that might otherwise be easily avoided. The empathy–altruism model does not dismiss egoistic motivations; helpers not empathizing with a victim may experience personal distress and have an egoistic motivation, not unlike the feelings and motivations explained by the arousal: cost–reward model. Because egoistically motivated individuals are primarily concerned with their own cost–benefit outcomes, they are less likely to help if they think they can escape the situation with no costs to themselves. In contrast, altruistically motivated helpers are willing to accept the cost of helping to benefit a person with whom they have empathized—this “self-sacrificial” approach to helping is the hallmark of altruism (Batson, 2011).

Although there is still some controversy about whether people can ever act for purely altruistic motives, it is important to recognize that, while helpers may derive some personal rewards by helping another, the help that has been given is also benefitting someone who was in need. The residents who offered food, blankets, and shelter to stranded runners who were unable to get back to their hotel rooms because of the Boston Marathon bombing undoubtedly received positive rewards because of the help they gave, but those stranded runners who were helped got what they needed badly as well. “In fact, it is quite remarkable how the fates of people who have never met can be so intertwined and complementary. Your benefit is mine; and mine is yours” (Dovidio et al., 2006, p. 143).

We started this module by asking the question, “Who helps when and why?” As we have shown, the question of when help will be given is not quite as simple as the viewers of “What Would You Do?” believe. The power of the situation that operates on potential helpers in real time is not fully considered. What might appear to be a split-second decision to help is actually the result of consideration of multiple situational factors (e.g., the helper’s interpretation of the situation, the presence and ability of others to provide the help, the results of a cost–benefit analysis) (Dovidio et al., 2006). We have found that men and women tend to help in different ways—men are more impulsive and physically active, while women are more nurturing and supportive. Personality characteristics such as agreeableness and the prosocial personality orientation also affect people’s likelihood of giving assistance to others. And, why would people help in the first place? In addition to evolutionary forces (e.g., kin selection, reciprocal altruism), there is extensive evidence to show that helping and prosocial acts may be motivated by selfish, egoistic desires; by selfless, altruistic goals; or by some combination of egoistic and altruistic motives. (For a fuller consideration of the field of prosocial behavior, we refer you to Dovidio et al. [2006].)

Test your Understanding

- Batson, C. D. (2011). Altruism in humans . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Becker, S. W., & Eagly, A. H. (2004). The heroism of women and men. American Psychologist, 59 , 163–178.

- Burnstein, E., Crandall, C., & Kitayama, S. (1994). Some neo-Darwinian decision rules for altruism: Weighing cues for inclusive fitness as a function of the biological importance of the decision. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67 , 773–789.

- Buss, D. M. (2004). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind . Boston, MA: Allyn Bacon.

- Cialdini, R. B., & Kenrick, D. T. (1976). Altruism as hedonism: A social developmental perspective on the relationship of negative mood state and helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34 , 907–914.

- Cialdini, R. B., Darby, B. K. & Vincent, J. E. (1973). Transgression and altruism: A case for hedonism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9 , 502–516.

- Cialdini, R. B., Kenrick, D. T., & Baumann, D. J. (1982). Effects of mood on prosocial behavior in children and adults. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The development of prosocial behavior (pp. 339–359). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1998). Trait theories in personality. In D. F. Barone, M. Hersen, & V. B. Van Hasselt (Eds.), Advanced Personality (pp. 103–121). New York, NY: Plenum.

- Darley, J. M. & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 , 377–383.

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene . Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Diekman, A. B., & Eagly, A. H. (2000). Stereotypes as dynamic structures: Women and men of the past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26 , 1171–1188.

- Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., Schroeder, D. A., & Penner, L. A. (2006). The social psychology of prosocial behavior . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Eagly, A. H., & Crowley, M. (1986). Gender and helping behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Review, 66 , 183–201.

- Fisher, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincie, C., Kastenmiller, A., Frey, D., Henne, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review of bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137 , 517–537.

- Graziano, W. G., & Tobin, R. (2009). Agreeableness. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Graziano, W. G., Habashi, M. M., Sheese, B. E., & Tobin, R. M. (2007). Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: A person x situation perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93 , 583–599.

- Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetic evolution of social behavior. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7 , 1–52.

- Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Penner, L. A., & Orom, H. (2010). Enduring goodness: A Person X Situation perspective on prosocial behavior. In M. Mikuliner & P.R. Shaver, P.R. (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 55–72). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Penner, L. A., Fritzsche, B. A., Craiger, J. P., & Freifeld, T. R. (1995). Measuring the prosocial personality. In J. Butcher & C.D. Spielberger (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 10, pp. 147–163). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Piliavin, J. A., Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Clark, R. D., III (1981). Emergency intervention . New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Trivers, R. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46 , 35–57.

- Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2002). A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin, 128 , 699–727.

The phenomenon whereby people intervene to help others in need even if the other is a complete stranger and the intervention puts the helper at risk.

Prosocial acts that typically involve situations in which one person is in need and another provides the necessary assistance to eliminate the other’s need.

Relying on the actions of others to define an ambiguous need situation and to then erroneously conclude that no help or intervention is necessary.

When deciding whether to help a person in need, knowing that there are others who could also provide assistance relieves bystanders of some measure of personal responsibility, reducing the likelihood that bystanders will intervene.

A decision-making process that compares the cost of an action or thing against the expected benefit to help determine the best course of action.

A core personality trait that includes such dispositional characteristics as being sympathetic, generous, forgiving, and helpful, and behavioral tendencies toward harmonious social relations and likeability.

Social behavior that benefits another person.

A measure of individual differences that identifies two sets of personality characteristics (other-oriented empathy, helpfulness) that are highly correlated with prosocial behavior.

A component of the prosocial personality orientation; describes individuals who have a strong sense of social responsibility, empathize with and feel emotionally tied to those in need, understand the problems the victim is experiencing, and have a heightened sense of moral obligations to be helpful.

A component of the prosocial personality orientation; describes individuals who have been helpful in the past and, because they believe they can be effective with the help they give, are more likely to be helpful in the future.

According to evolutionary psychology, the favoritism shown for helping our blood relatives, with the goals of increasing the likelihood that some portion of our DNA will be passed on to future generations.

According to evolutionary psychology, a genetic predisposition for people to help those who have previously helped them.

An egoistic theory proposed by Cialdini et al. (1982) that claims that people have learned through socialization that helping can serve as a secondary reinforcement that will relieve negative moods such as sadness.

An egoistic theory proposed by Piliavin et al. (1981) that claims that seeing a person in need leads to the arousal of unpleasant feelings, and observers are motivated to eliminate that aversive state, often by helping the victim. A cost–reward analysis may lead observers to react in ways other than offering direct assistance, including indirect help, reinterpretation of the situation, or fleeing the scene.

A motivation for helping that has the improvement of the helper’s own circumstances as its primary goal.

A motivation for helping that has the improvement of another’s welfare as its ultimate goal, with no expectation of any benefits for the helper.

An altruistic theory proposed by Batson (2011) that claims that people who put themselves in the shoes of a victim and imagining how the victim feel will experience empathic concern that evokes an altruistic motivation for helping.

According to Batson’s empathy–altruism hypothesis, observers who empathize with a person in need (that is, put themselves in the shoes of the victim and imagine how that person feels) will experience empathic concern and have an altruistic motivation for helping.

According to Batson’s empathy–altruism hypothesis, observers who take a detached view of a person in need will experience feelings of being “worried” and “upset” and will have an egoistic motivation for helping to relieve that distress.

Introduction to Social Psychology Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Jennifer Brown is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 24 January 2024

Cortical regulation of helping behaviour towards others in pain

- Mingmin Zhang 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Ye Emily Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8052-1073 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Mengping Jiang 1 , 2 &

- Weizhe Hong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1523-8575 1 , 2 , 4

Nature volume 626 , pages 136–144 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

1 Citations

73 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neural circuits

- Social behaviour

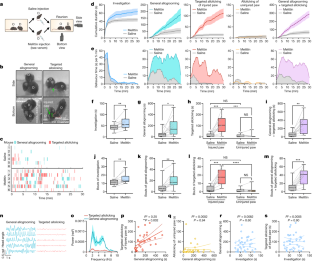

Humans and animals exhibit various forms of prosocial helping behaviour towards others in need 1 , 2 , 3 . Although previous research has investigated how individuals may perceive others’ states 4 , 5 , the neural mechanisms of how they respond to others’ needs and goals with helping behaviour remain largely unknown. Here we show that mice engage in a form of helping behaviour towards other individuals experiencing physical pain and injury—they exhibit allolicking (social licking) behaviour specifically towards the injury site, which aids the recipients in coping with pain. Using microendoscopic imaging, we found that single-neuron and ensemble activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) encodes others’ state of pain and that this representation is different from that of general stress in others. Furthermore, functional manipulations demonstrate a causal role of the ACC in bidirectionally controlling targeted allolicking. Notably, this behaviour is represented in a population code in the ACC that differs from that of general allogrooming, a distinct type of prosocial behaviour elicited by others’ emotional stress. These findings advance our understanding of the neural coding and regulation of helping behaviour.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Reciprocal cortico-amygdala connections regulate prosocial and selfish choices in mice

The role of the anterior insula during targeted helping behavior in male rats

Increased similarity of neural responses to experienced and empathic distress in costly altruism

Data availability.

All data and analyses necessary to understand the conclusions of the manuscript are presented in the main text and in Extended Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for behavioural analysis ( https://github.com/pdollar/toolbox and https://github.com/hongw-lab/Behavior_Annotator ), animal pose tracking ( https://github.com/murthylab/sleap/releases/tag/v1.2.9 ), analysis of mouse vocalizations ( https://github.com/rtachi-lab/usvseg ) 47 , microendoscopic imaging data analysis ( https://github.com/etterguillaume/MiniscopeAnalysis , https://github.com/zhoupc/CNMF_E and https://github.com/flatironinstitute/NoRMCorre ), ROC and SVM decoding analysis is available ( https://github.com/hongw-lab/Code_for_2024_ZhangM ) on GitHub.

Wu, Y. E. & Hong, W. Neural basis of prosocial behavior. Trends Neurosci. 45 , 749–762 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

de Waal, F. B. M. & Preston, S. D. Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18 , 498–509 (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Keysers, C., Knapska, E., Moita, M. A. & Gazzola, V. Emotional contagion and prosocial behavior in rodents. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26 , 688–706 (2022).

Ferretti, V. & Papaleo, F. Understanding others: emotion recognition in humans and other animals. Genes Brain Behav. 18 , e12544 (2019).

Sterley, T.-L. & Bains, J. S. Social communication of affective states. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 68 , 44–51 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Melis, A. P. The evolutionary roots of prosociality: the case of instrumental helping. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 20 , 82–86 (2018).

Dunfield, K. A. A construct divided: prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Front. Psychol. 5 , 958 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lim, K. Y. & Hong, W. Neural mechanisms of comforting: prosocial touch and stress buffering. Horm. Behav. 153 , 105391 (2023).

Bartal, I. B.-A., Decety, J. & Mason, P. Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science 334 , 1427–1430 (2011).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Li, A. K., Koroly, M. J., Schattenkerk, M. E., Malt, R. A. & Young, M. Nerve growth factor: acceleration of the rate of wound healing in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 77 , 4379–4381 (1980).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Berckmans, R. J., Sturk, A., Tienen, L. M., van, Schaap, M. C. L. & Nieuwland, R. Cell-derived vesicles exposing coagulant tissue factor in saliva. Blood 117 , 3172–3180 (2011).

Day, B. J. The science of licking your wounds: function of oxidants in the innate immune system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 163 , 451–457 (2019).

Lu, J. et al. Somatosensory cortical signature of facial nociception and vibrotactile touch–induced analgesia. Sci. Adv. 8 , eabn6530 (2022).

Huang, T. et al. Identifying the pathways required for coping behaviours associated with sustained pain. Nature 565 , 86–90 (2019).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hutson, J. M., Niall, M., Evans, D. & Fowler, R. Effect of salivary glands on wound contraction in mice. Nature 279 , 793–795 (1979).

Dittus, W. P. J. & Ratnayeke, S. M. Individual and social behavioral responses to injury in wild toque macaques ( Macaca sinica ). Int. J. Primatol. 10 , 215–234 (1989).

Article Google Scholar

Li, C.-L. et al. Validating rat model of empathy for pain: effects of pain expressions in social partners. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12 , 242 (2018).

Lariviere, W. R. & Melzack, R. The bee venom test: a new tonic-pain test. Pain 66 , 271–277 (1996).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wu, Y. E. et al. Neural control of affiliative touch in prosocial interaction. Nature 599 , 262–267 (2021).

Mogil, J. S. Animal models of pain: progress and challenges. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10 , 283–294 (2009).

Duan, B., Cheng, L. & Ma, Q. Spinal circuits transmitting mechanical pain and itch. Neurosci. Bull. 34 , 186–193 (2018).

Smith, M. L., Asada, N. & Malenka, R. C. Anterior cingulate inputs to nucleus accumbens control the social transfer of pain and analgesia. Science 371 , 153–159 (2021).

Carrillo, M. et al. Emotional mirror neurons in the rat’s anterior cingulate cortex. Curr. Biol. 29 , 1301–1312 (2019).

Allsop, S. A. et al. Corticoamygdala transfer of socially derived information gates observational learning. Cell 173 , 1329–1342 (2018).

Hernandez-Lallement, J. et al. Harm to others acts as a negative reinforcer in rats. Curr. Biol. 30 , 949–961 (2020).

Lockwood, P. L. The anatomy of empathy: vicarious experience and disorders of social cognition. Behav. Brain Res. 311 , 255–266 (2016).

Johansen, J. P., Fields, H. L. & Manning, B. H. The affective component of pain in rodents: direct evidence for a contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98 , 8077–8082 (2001).

Sato, N., Tan, L., Tate, K. & Okada, M. Rats demonstrate helping behavior toward a soaked conspecific. Anim. Cogn. 18 , 1039–1047 (2015).

Ueno, H. et al. Rescue-like behaviour in mice is mediated by their interest in the restraint tool. Sci. Rep. 9 , 10648 (2019).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Burkett, J. P. et al. Oxytocin-dependent consolation behavior in rodents. Science 351 , 375–378 (2016).

Langford, D. J. et al. Social modulation of pain as evidence for empathy in mice. Science 312 , 1967–1970 (2006).

Bernhardt, B. C. & Singer, T. The neural basis of empathy. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35 , 1–23 (2012).

Phillips, H. L. et al. Dorsomedial prefrontal hypoexcitability underlies lost empathy in frontotemporal dementia. Neuron 111 , 797–806 (2023).

Gangopadhyay, P., Chawla, M., Monte, O. D. & Chang, S. W. C. Prefrontal–amygdala circuits in social decision-making. Nat. Neurosci. 24 , 5–18 (2021).

Haroush, K. & Williams, Z. M. Neuronal prediction of opponent’s behavior during cooperative social interchange in primates. Cell 160 , 1233–1245 (2015).

Paulus, M., Kühn-Popp, N., Licata, M., Sodian, B. & Meinhardt, J. Neural correlates of prosocial behavior in infancy: different neurophysiological mechanisms support the emergence of helping and comforting. Neuroimage 66 , 522–530 (2013).

Paxinos, G. & Franklin, K. B. J. The Mouse brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates , 3rd edn (Academic Press, 2008).

Tjølsen, A., Berge, O.-G., Hunskaar, S., Rosland, J. H. & Hole, K. The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain 51 , 5–17 (1992).

Chen, J., Guan, S.-M., Sun, W. & Fu, H. Melittin, the major pain-producing substance of bee venom. Neurosci. Bull. 32 , 265–272 (2016).

Kingsbury, L. et al. Correlated neural activity and encoding of behavior across brains of socially interacting animals. Cell 178 , 429–446 (2019).

Zhou, T., Sandi, C. & Hu, H. Advances in understanding neural mechanisms of social dominance. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 49 , 99–107 (2018).

Armbruster, B. N., Li, X., Pausch, M. H., Herlitze, S. & Roth, B. L. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 5163–5168 (2007).

Pereira, T. D. et al. SLEAP: a deep learning system for multi-animal pose tracking. Nat. Methods 19 , 486–495 (2021).

Pnevmatikakis, E. A. & Giovannucci, A. NoRMCorre: An online algorithm for piecewise rigid motion correction of calcium imaging data. J. Neurosci. Methods 291 , 83–94 (2017).

Zhou, P. et al. Efficient and accurate extraction of in vivo calcium signals from microendoscopic video data. eLife 7 , e28728 (2018).

Kingsbury, L. et al. Cortical representations of conspecific sex shape social behavior. Neuron 107 , 941–953 (2020).

Tachibana, R. O., Kanno, K., Okabe, S., Kobayasi, K. I. & Okanoya, K. USVSEG: a robust method for segmentation of ultrasonic vocalizations in rodents. PLoS ONE 15 , e0228907 (2020).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Ma, S. Chaudhry, X. Zhang, L. Gu and S. Kim for technical assistance; C. Cahill for suggestions on pain-related experimental procedures; and members of the laboratory of W.H. for valuable comments. Schematics in Figs. 1a , 2a,m,p , 3a,d,i,n and 4a,f and Extended Data Figs. 4a , 9a and 10g,i were created with BioRender.com . This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants (R01 MH130941, R01 NS113124, R01 MH132736, RF1 NS132912 and UF1 NS122124), a Packard Fellowship in Science and Engineering, a Keck Foundation Junior Faculty Award, a Vallee Scholar Award and a Mallinckrodt Scholar Award (to W.H.).

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Mingmin Zhang, Ye Emily Wu

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Neurobiology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Mingmin Zhang, Ye Emily Wu, Mengping Jiang & Weizhe Hong

Department of Biological Chemistry, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Department of Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Ye Emily Wu

Department of Bioengineering, Samueli School of Engineering, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Weizhe Hong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.Z., Y.E.W. and W.H. designed the study. M.Z. carried out all experiments. Y.E.W. and M.Z. carried out computational data analysis. M.J. assisted in some experiments. Y.E.W., M.Z. and W.H. wrote the manuscript. W.H. supervised the entire study.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Weizhe Hong .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.