Cornelia van Scherpenberg, Lindsey Bultema, Anja Jahn, Michaela Löffler, Vera Minneker, Jana Lasser

Manifestations of power abuse in academia and how to prevent them

11 March 2021 | doi:10.5281/zenodo.4580544 | 1 Comment

A group of researchers from the German N² network presents the results of a survey among PhD students on the abuse of power in science and outlines ways to counter it

This article results from a cooperation within N² , a network of the Helmholtz Juniors , Leibniz PhD Network and Max Planck PhDnet . The International PhD Program Mainz (IPP) is an associated member of N². Representing more than 16.000 doctoral researchers, it is the biggest network of doctoral researchers in Germany. The N² member networks regularly conduct surveys and, individually or in the framework of N², represent issues concerning the doctoral researchers of their networks towards the respective research organizations as well as to the public.

In recent years, evidence of cases of power abuse in academia have been made public in various news reports about poor leadership, bullying and even sexual harassment of employees by superiors at universities (Boytchev, 2020; Hartocollis, 2018; Schenkel, 2018) and non-university research organisations in Germany and abroad (Devlin & Marsh, 2018; Weber, 2018). In addition, surveys amongst employees (especially doctoral researchers) at these institutions has revealed alarming numbers of instances of (witnessing) bullying (In German reports of abusive behaviour at the workplace, the word „mobbing“ is often used for „bullying“), discrimination or sexual harassment by a superior (e.g., Arcudi et al., 2019; Beadle et al., 2020; Olsthoorn et al., 2020; Peukert et al., 2020; Regler et al., 2019; Schraudner et al., 2019).

These numbers and reports suggest that the basis for these incidents is inherent in the structures of the academic system. The academic system, not only in Germany, is set up very hierarchically – people with an established career (e.g., a professor, a research group leader, or a director of a research institute) sit at the top, while early career researchers, continuing their education and advancing their career, are at the lower end of the hierarchy.

In this article we outline the manifestations of power hierarchy and dependencies in the academic system from the point of view of doctoral researchers (DRs) – based on findings from surveys on the situation of DRs at non-university research organisations in Germany, as well as on our own experiences as DRs and elected representatives of the DRs in the Helmholtz Association, Leibniz Association, Max Planck Society and IPP Mainz, respectively. Moreover, we give recommendations on how to navigate and prevent instances of power abuse and summarize which measures have already been taken by research institutions such as those with which N² member networks are affiliated (A detailed report on our results and observations can also be found in the contribution to the 2020 conference “Absender unbekannt. Anonyme Anschuldigungen in der Wissenschaft“ (Lasser et al., accepted)).

DATA COLLECTION ON SUPERVISION AND INSTANCES OF POWER ABUSE IN THE 2019 N² HARMONIZED SURVEY

In 2019, the N² members conducted harmonized surveys in their networks. The individual survey reports (Beadle et al., 2020; Olsthoorn et al., 2020; Peukert et al., 2020) shed light on the relationship between supervision, working conditions, mental health and experiences of abusive behaviour. Supplemented by reports from other large national (Briedis et al., 2018; Schraudner et al., 2019) and international surveys (Wellcome Trust, 2020; Woolston, 2019), they serve as evidence for the status quo of the prevalence of power abuse in (German) academia, which we outline below.

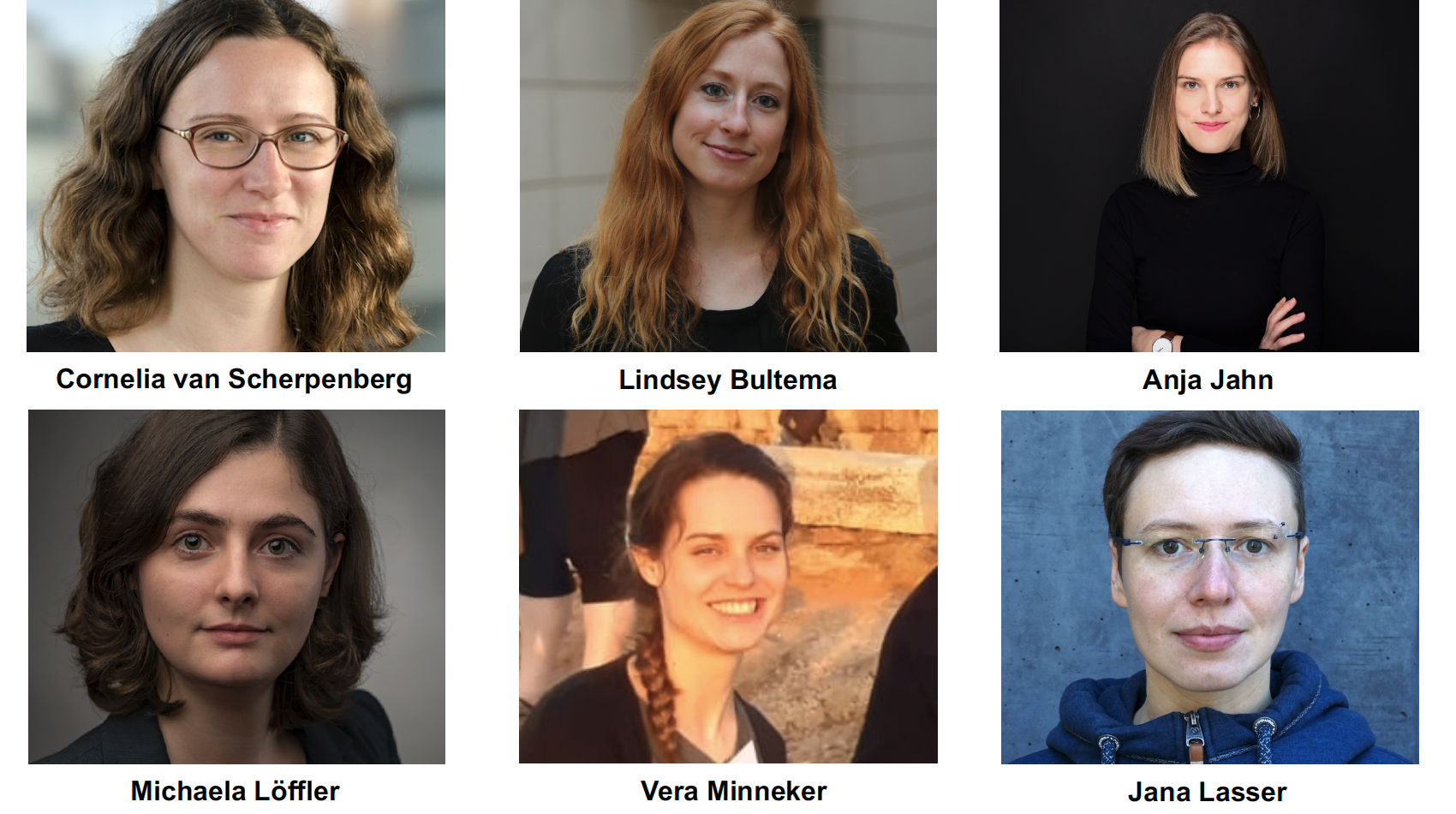

Prevalence of conflict cases amongst early career researchers According to our surveys 10-13% of DRs report to have been subjected to bullying by a superior at least once (Figure 1A). Only one third of those who have experienced bullying reported the incident to an official body (Figure 1B) and out of those, only about a quarter are satisfied with how the matter was resolved (Figure 1C). In other surveys (e.g., Schraudner et al., 2019), the respondents’ two most important reasons for not reporting an incident are their concerns that there would be no consequences for the perpetrator and the fear that their career would be impeded. Indeed, significant numbers reported general negative consequences or specific negative consequences for their career after they made a report.

Figure 1: Experiences with bullying and conflict reporting. A: Participants were asked “While working at your institute/center, have you at any point been subjected to bullying by a superior?”. The graph shows the fraction over all respondents who have at least once experienced bullying by a superior. B: Participants were asked “Did you ever report a conflict with a superior?”. The graph shows the fraction over all respondents who answered “yes”. C: For those who answered yes in (B), participants were asked “Please indicate the level of satisfaction with the consequences of your report?”. The answers were given on a scale from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied” and are grouped here (dissatisfied = very dissatisfied + dissatisfied, neither nor, satisfied = very satisfied + satisfied). Numbers compiled from the individual survey reports by the respective networks that are part of N2 (Beadle et al., 2020; Olsthoorn et al., 2020; Peukert et al., 2020). Graphic created by Theresa Kuhl, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Centre for Environmental Health.

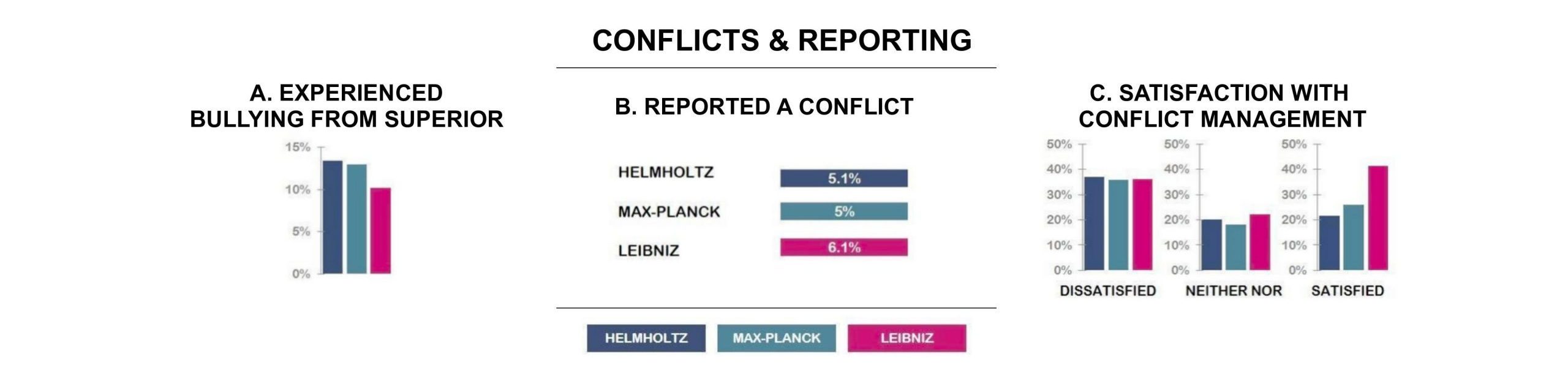

Amongst the DRs represented by N², about a quarter of DRs are dissatisfied with their supervision (Figure 2A) and about a third consider giving up their PhD “often” or “occasionally”, a tendency that correlates with experiences of bullying (Figure 2B, see also Briedis et al, 2018). These findings universally show that DRs perceive the strong and multiple dependencies between them and their supervisors as problematic, leading to dissatisfaction, mental health problems (For a detailed report on the mental health crisis among doctoral researchers see our previous post on this blog) and thoughts about quitting.

Figure 2: Satisfaction with supervision and aspects of academia. A: Participants were asked “How satisfied are you with your PhD supervision in general?”. The answers were given on a scale from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied” and are grouped here (dissatisfied = very dissatisfied + dissatisfied + rather dissatisfied, satisfied = very satisfied + satisfied + rather dissatisfied). Numbers compiled from the individual survey reports by the respective networks that are part of N2 (Beadle et al., 2020; Olsthoorn et al., 2020; Peukert et al., 2020). Graphic created by Theresa Kuhl, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Centre for Environmental Health.

Multiple dependencies in academia

Why do conflicts between supervisors and DRs occur and how do they manifest? Due to the academic hierarchy, power differentials between DRs and their superiors exist in different, often interconnected areas of academic life. In the majority of cases, the employer and scientific supervisor are the same person, who therefore has administrative power over future employment and contract extensions as well as over evaluation of scientific results. These professors, institute directors, research group leaders, or principal investigators (PIs) and their relationship to the DR have a direct impact on the DR’s academic reputation and future successful navigation through the academic system (e.g., as co-authors on publications and grant applications, through grading of theses, or through recommendation letters). These various dependencies on the superior put the DR in a vulnerable position. They have a lot to lose and may therefore be unable or unwilling to defend themselves in cases of conflict. A closer look at these characteristics of power differentials reveals their potential as sources of conflicts and abusive behavior – but also the opportunity to alleviate them through measures and systematic changes.

Power through scientific evaluation Traditionally, in German universities and research institutions, the main supervisor of a dissertation is also the main evaluator of the project. This means that they have to assess the quality of a thesis which results from work they supervised themselves. This conflation between supervision and assessment often results in a conflict of interest that can take many forms.

On the one hand, there are no incentives for superiors to truthfully evaluate the work they have supervised (sometimes on a daily basis): Senior researchers (such as PIs or professors) are often assessed on the number of DRs they graduate – an incentive to let people pass with low grades rather than failing them due to substandard work.

On the other hand and more commonly, supervisors can use the threat of a bad thesis evaluation to compel work from the DRs beyond what has been contractually agreed upon – for example when it comes to scientific publications. The duration required to publish in an academic journal varies greatly, depending on the journal and field. Although the researcher can assess the average time it takes from submission to acceptance for a specific journal, once the article is submitted, they no longer have control over how quickly the submission progresses through the peer review system (Huisman & Smits, 2017). In turn, this can delay the thesis completion by many months.

Figure 3: Employment situation and working hours of DRs in the N2 member organizations. Numbers compiled from the individual survey reports by the respective networks that are part of N2 (Beadle et al., 2020; Olsthoorn et al., 2020; Peukert et al., 2020). Graphic created by Theresa Kuhl, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Centre for Environmental Health.

Power over type and length of employment Researchers usually have a high intrinsic motivation to work extensively on their research, and this is exacerbated by the high pressure and competitive environment in academia (Woolston, 2019). However, pressure from supervisors is given as a main reason for long average working hours (see Figure 3A), work on weekends and a tendency not to take vacation time in academia. This pressure is intensified by the precarious employment situation of the majority of DRs.

Employment contracts for DRs are almost always time-limited: 98% of DRs working at universities or non-university research institutions have fixed-term contracts (BUWIN, 2021, p. 111); for postdocs or scientists without tenure under the age of 45 this number still ranges between 84-96% (BUWIN, 2021, p.112). Data reveals that a PhD in Germany takes between 3.5 and 7.1 years, depending on the subject (BUWIN, 2021, p. 138; Jaksztat et al., 2012; and see Figure 3B). However, our survey results show that many DRs receive a contract with a duration of less than 36 months (Figure 3C). These contract durations are not long enough to ensure the completion of a PhD within the first employment contract and make it very likely that DRs will need at least one contract extension to complete their degree. The situation is even more precarious for other early career researchers such as postdocs and junior group leaders. In 2017, half of all employment contracts were reported to be limited to less than one year (BUWIN, 2017, p.132), even though research projects regularly take substantially longer to be completed. This situation seems to have improved slightly, with average contract durations of 28 months for postdocs (BUWIN, 2021, p. 116/117).

Decisions about further employment of DRs are often taken by a single person who has power over the research unit, institute or third-party funding on which the DR is employed. This means that DRs regularly depend on them to extend their contracts. While a permanent contract cannot be easily terminated as it usually requires justification and/or involvement of the works or staff council, employees with short-term contracts can be easily let go by simply not renewing their contract. In addition to increasing the researchers’ financial vulnerability, these precarious employment conditions are especially threatening to international researchers from outside the European Union, who might lose their residence permit, which is directly tied to their working contract.

Power over reputation and knowledge transfer Particularly at the beginning of an academic career, DRs are dependent on their superiors to share their knowledge and experience of the academic sphere with them, in order to be successful in academia. For example, the PI or professor is much more knowledgeable about appropriate funding agencies, appropriate venues for publications, conferences and the scientific network.

Researchers profit significantly when their supervisors introduce them into relevant academic circles and help them move through the bottleneck of academic hierarchy in general. This puts supervisors in a unique position of power, to foster or damage the reputation of the DRs. Less than half of the DRs report that they receive the support they need from their supervisors to further their career. This can manifest itself in supervisors allowing or preventing DRs from attending conferences and criticizing their graduates in front of other senior researchers and potential future employers. The most formal shape that this power differential takes is the letter of recommendation which is required for almost all applications to future academic and non-academic positions. Supervisors have no obligation to provide such a letter and if they do, they have no obligation to substantiate a negative assessment of the DR. Moreover, in most academic fields, supervisors have the power to decide about authorship contributions in academic publications. In many cases, at least one first or corresponding author publication is required to receive a doctorate and to successfully apply for a research position or grant after completion of the PhD. The pressure to “publish or perish” leaves DRs dependent on their supervisor to grant them this (first) authorship (Wu et al., 2019).

Lastly, it is much harder for international researchers (especially on short-term contracts) to familiarize themselves with the bureaucratic structures, workplace regulations and their own employment rights.

THE VICIOUS CYCLE OF ABUSIVE BEHAVIOUR IN ACADEMIA…

As outlined above, power differentials exist in many aspects of academia and DRs depend on their supervisors for their livelihood, reputation and future career. These systemic conditions lay the ground for ubiquitous potential conflicts. However, as incidents of abusive behaviour are rarely reported, the academic system is deprived of much-needed feedback from a majority of its members, hindering improvement. At worst, DRs might pass on their own experiences of bad and abusive supervision when they become postdocs or when it is their turn to supervise and lead a research group – the vicious cycle of bad scientific leadership and dependencies. This situation is damaging for the academic system as a whole, as it rewards conformism and alienates original thinkers and creative young minds from research. This way, the competitiveness of academia is reproduced time and time again, leaving researchers little room to pursue their original goal: to advance scientific progress (see also Dirnagl, 2021).

Therefore, we propose a variety of measures that have the potential not only to resolve but prevent conflicts related to power differentials and break the vicious cycle. The recommendations are based on a position paper on Power Abuse and Conflict Resolution published by our network (N², 2019). We would like to stress that some recommendations we describe here are already (being) implemented in research institutions, also through fruitful exchanges between the institutions and PhD representatives or networks (see Infobox).

Conflict Resolution & Prevention of Power Abuse Measures implemented by the Helmholtz Association (HGF), the Max Planck Society (MPG) & the Leibniz Association (WGL). Many research institutions and universities have implemented measures for prevention and resolution of conflict. In many instances, these measures were the result of a fruitful collaboration with the respective PhD networks. The following measures have been implemented in the organisations represented by N²:

Supervision agreement and Thesis Advisory Committees

- 55-70% of DRs have a supervision agreement and/or a Thesis Advisory Committee (N² harmonized survey 2019).

- Supervision agreement composed by Leibniz PhD Network in 2020, already implemented in some WGL institutes ( link ).

- Supervision and employment guidelines on an institutional level are stated in doctoral guidelines ( HGF , MPG , WGL )

Leadership trainings

- MPG started seminars and coaching for directors and research group leaders within the framework of the Planck Academy founded in 2020.

- The HGF has introduced the Helmholtz Leadership Academy .

- The WGL has established a lecture program on leadership ( Führungskolleg ).

Conflict reporting and resolution

- In order to deal with conflicts, institutes and centers of the HGF, MPG and WGL have local ombudspersons.

- The WGL introduced a central ombuds committee in 2020 ( link ).

- The HGF is currently establishing a central ombudsperson with the new good scientific practice guidelines.

- The MPG assigned an external law firm as an independent contact point in 2018, and in 2019 established an Internal Investigations Unit as a central reporting office that can initiate investigations.

- The WGL created the external Advice Center for Conflict Guidance and Prevention.

… AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HOW TO BREAK IT

Supervision agreements First of all, power differentials can be navigated and power abuse prevented if DRs and their supervisors sign and adhere to a supervision agreement, which clearly outlines roles, expectations and procedures from both sides. Such an agreement can go a long way in preventing a mismatch of expectations or misunderstandings right from the beginning of a project and side-stepping potential conflicts that could escalate. They also establish a level of accountability for the supervision provided, and also for the work expected from the DR.

Thesis Advisory Committees Moreover, PhD supervision should be spread out to more than one person, ideally in the form of a Thesis Advisory Committee, which includes external, independent advisors who consult on the progress of the dissertation project. This is already common practice in the UK, but also in most institutes belonging to the Max Planck Society (see infobox).

At the same time, when it comes to thesis assessment, there should be a clear division between main supervisor and main referee. At the minimum, as suggested also by the Hochschulrektorenkonferenz (HRK, 2012), external reviewers should be included in the thesis evaluation and grading process.

Leadership and communication trainings An additional measure which promises to alleviate the instances of power differentials outlined above, is to introduce leadership training for any senior researcher taking on supervision and/or leadership responsibility. This addresses the assumption that power abuse often does not happen out of spite but is rather an expression of the inability to effectively manage and lead a research group. With the latest incidents of power abuse (Boytchev, 2020; Devlin & Marsh, 2018; Hartocollis, 2018; Weber, 2018), it has become once more apparent that scientific excellence does not equal good leadership skills. Therefore, any researcher who is responsible for the supervision of DRs should take part in mandatory and regular leadership training in order to learn how best to guide the DRs and their other employees through the existing differentials in reputation, knowledge and employment status. At the same time, doctoral researchers and postdocs would benefit from training courses focusing on communication and cultural skills, empowerment for networking and career choices, and knowledge about navigating the academic system and its obstacles.

Confidential and independent conflict resolution Whenever a conflict occurs, the victim should have the opportunity to make a confidential report of the incident with the expectation of a timely investigation. Therefore, it is important that the existing reporting structures are clearly outlined by the institution and regularly communicated to its members. Conflict resolution should involve a multi-staged investigation, as appropriate to the level of escalation of the conflict. Such a process should start at local conflict resolution mechanisms (Ombudsperson, works council etc.) and include the possibility to involve investigation of the conflict case by an independent committee. All steps of the conflict resolution mechanism must be clearly documented and communicated to all parties involved. In all instances, when the victim feels it is necessary, their anonymity must be protected. The trust in these mechanisms is key to establish them as a feedback structure for researchers from all levels.

Protection through anonymity From our own experience as representatives of DRs and through studying the data from our surveys, we know that a strong motivator for DRs not to report incidents of abusive behaviour is the fear of negative consequences for their careers. Thus, the possibility to anonymously contact people responsible for conflict resolution (such as an ombudsperson or gender equality officer) allows victims of power abuse to receive support without the fear of direct repercussions from their supervisor. Importantly, the identity of the person reporting a conflict needs to remain anonymous to the offender, even after the conclusion of the investigation, to protect the reputation and career of the victim.

Recently, anonymous accusations in the academic context have been discussed critically (e.g., Buchhorn & Freisinger, 2020). We acknowledge that allegations of power abuse can have a very damaging impact on the reputation and career of senior researchers as well. However, firstly, according to a recent report by the German “Ombudsman für die Wissenschaft” (Czesnick & Rixen, in press), anonymous accusations only account for approximately 10% of all accusations. Secondly, assessing the substance of an accusation can be achieved without knowing the identity of the accuser. Lastly, anonymity extends to the potential offender as well, ensuring their opportunity to defend themselves and resolve the incident without damage to their reputation.

Overall, anonymity is an absolute necessity to alleviate the power differentials between DRs and senior researchers and encourage reporting of incidents and corrective action. Taking into account the measures which have already been implemented (see Infobox), the developments are promising. As representatives of doctoral researchers, we regularly communicate our recommendations to various stakeholders of the academic system within our organizations and beyond and highly appreciate when they are taken seriously and when PhD representatives are invited to take part in the development of appropriate measures. We recognize the importance of and the need to change the organizational culture surrounding power differentials in academia. While a system is hard to change, we believe that implementation of the measures outlined above will reduce the incidences of abusive behavior and enable the academic system to deal with conflicts that it currently cannot resolve in a satisfactory manner. Only through collaboration on all levels of the academic hierarchy can we maintain a system that provides a healthy feedback culture, offers a supportive and sustainable working environment, and fosters excellent research.

Arcudi, A., Cumurovic, A., Gotter, C., Graeber, D., Joly, P., Ott, V., Schanze, J.-L., Thater, S., Weltin, M., & Yenikent, S. (2019). Doctoral Researchers in the Leibniz Association: Final Report of the 2017 Leibniz PhD Survey .

Beadle, B., Do, S., El Youssoufi, D., Felder, D., Gorenflos López, J., Jahn, A., Pérez-Bosch Quesada, E., Rottleb, T., Rüter, F., Schanze, J.-L., Stroppe, A.-K., Thater, S., Verrière, A., & Weltin, M. (2020). Being a Doctoral Researcher in the Leibniz Association: 2019 Leibniz PhD Network Survey Report . Leibniz PhD Network. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/69403

Boytchev, H. (2020). Neue Vorwürfe von Mobbing und Willkür in der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. BuzzFeed .

Briedis, K., Lietz, A., Ruß, U., Schwabe, U., Weber, A., Birkelbach, R., & Hoffstätter, U. (2018). NACAPS 2018 .

Buchhorn, E., & Freisinger, G. M. (2020). Mission Rufmord: Mobbing gegen Führungskräfte. manager magazin .

BUWIN (2017). Bundesbericht Wissenschaftlicher Nachwuchs 2017: Statistische Daten und Forschungsbefunde zu Promovierenden und Promovierten in Deutschland. http://www.oapen.org/download/?type=document&docid=640942

BUWIN (2021). Bundesbericht Wissenschaftlicher Nachwuchs 2021: Statistische Daten und Forschungsbefunde zu Promovierenden und Promovierten in Deutschland. https://www.buwin.de/dateien/buwin-2021.pdf

Czesnick, H., & Rixen, S. (in press). Sind anonyme Hinweise auf wissenschaftliches Fehlverhalten ein Problem? Eine Einschätzung aus Sicht des “Ombudsman für die Wissenschaft.”

Devlin, H., & Marsh, S. (2018). Top cancer scientist loses £3.5m of funding after bullying claims . https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/aug/17/top-cancer-scientist-has-35m-in-grants-revoked-after-bullying-claims

Dirnagl, U. (2021). Back to the Future: Von industrieller zu inhaltlicher Forschungsbewertung [Laborjournal Online]. Einsichten Eines Wissenschaftsnarren. https://www.laborjournal.de/rubric/narr/narr/n_21_01.php

Hartocollis, A. (2018, November 15). Dartmouth Professors Are Accused of Sexual Abuse by 7 Women in Lawsuit (Published 2018). The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/15/us/dartmouth-professors-sexual-harassment.html

HRK. (2012). Empfehlung zur Qualitätssicherung in Promotionsverfahren .

Huisman, J., & Smits, J. (2017). Duration and quality of the peer review process: The author’s perspective. Scientometrics , 113 (1), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2310-5

Jaksztat, S., Preßler, N., & Briedis, K. (2012). Promotions- und Arbeitsbedingungen Promovierender im Vergleich . HIS: Forum Hochschule. https://www.uni-heidelberg.de/md/journal/2013/04/fh201215_promotion.pdf

Lasser, J., Bultema, L., Jahn, A., Löffler, M., Minneker, V., & van Scherpenberg, C. (submitted). Power abuse and anonymous accusation in academia from the point of view of early career researchers. In Anonyme Anschuldigungen in der Wissenschaft .

N². (2019). Power abuse and conflict resolution .

Olsthoorn, L. H. M., Heckmann, L. A., Filippi, A., Vieira, R. M., Varanasi, R. S., Lasser, J., Bäuerle, F., Zeis, P., Schulte-Sasse, R., & Group 2019/2020, M. P. P. survey. (2020). PhDnet Report 2019 . Max Planck PhDnet. https://pure.mpg.de/pubman/faces/ViewItemOverviewPage.jsp?itemId=item_3243876_4

Peukert, K., Jacobi, L., Geuer, J., Paredes Cisneros, I., Löffler, M., Lienig, T., Taylor, S., Gusic, M., Novakovic, N., Kuhl, T., Ordini, E., Runge, A., Samoylov, O., Härtel, M., Amend, A.-L., & Nagel, M. (2020). Survey report 2019 . Helmholtz Juniors. https://www.helmholtz.de/fileadmin/user_upload/06_jobs_talente/Helmholtz-Juniors/Survey_Report2019.pdf

Regler, B., Einhorn, L., Lasser, J., Vögele, M., Elizarova, S., Bäuerle, F., Wu, C., Förste, S., Shenolikar, J., & Group 2018, P. S. (2019). PhDnet Report 2018 . https://doi.org/10.17617/2.3052826

Schenkel, L. (2018). Die ETH entlässt Professorin Carollo wegen Mobbing-Vorwürfen – 7 Antworten zur ersten Kündigung in der Geschichte der Hochschule . Neue Zürcher Zeitung. https://www.nzz.ch/zuerich/eth-zuerich-entlaesst-professorin-carollo-die-wichtigsten-fakten-ld.1495950

Schraudner, M., Striebing, C., & Hochfeld, K. (2019). Work culture and work atmosphere in the Max Planck Society . Fraunhofer Center for Responsible Research and Innovation. https://www.mpg.de/14284109/mpg-arbeitskultur-ergebnisbericht-englisch.pdf

Weber, C. (2018). Max-Planck-Direktorin Tania Singer verlässt Institut . Süddeutsche.de. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wissen/max-planck-empathie-singer-1.4240504

Wellcome Trust. (2020). What Researchers Think About the Culture They Work In . Wellcome Trust. https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/what-researchers-think-about-the-culture-they-work-in.pdf

Woolston, C. (2019). PhDs: The tortuous truth. Nature , 575 (7782), 403–406. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03459-7

Wu, C. M., Regler, B., Bäuerle, F. K., Vögele, M., Einhorn, L., Elizarova, S., Förste, S., Shenolikar, J., & Lasser, J. (2019). Perceptions of publication pressure in the Max Planck Society. Nature Human Behaviour , 3 (10), 1029–1030. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0728-x

thank you for the article

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

First we need to confirm, that you're human. fifty four ÷ = nine

Author info

Cornelia van Scherpenberg is a doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Science where she researches the neural basis of language production processes. She is a member of the N² advisory board and was deputy spokesperson of the Max Planck PhDnet and N² board member in 2020.

Lindsey Bultema is a doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter, Hamburg. She’s focusing on in-liquid electron imaging techniques. She is the 2020 Spokesperson of the Max Planck PhDnet and current advisory board member of N².

Anja Jahn is a doctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute for History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) in Leipzig. In research she focuses on multilingualism in the literatures of East Central Europe. She is member of the N² Advisory board and was spokesperson of the Leibniz PhD Network and N² Board member from September 2019 to October 2020.

Michaela Löffler is researching hydrogen isotope effects at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ in Leipzig. She was spokesperson for the doctoral representation Helmholtz Juniors and thus N² Board member in 2020.

Vera Minneker is a doctoral researcher and coordinator of the “International PhD Programme on Gene Regulation, Epigenetics and Genome Stability“ (IPP) at the Institute for Molecular Biology gGmbH Mainz. She was an elected doctoral researcher representative of the IPP and board member of N² from April 2019 to August 2020. She studies the formation of oncogenic chromosome translocations using high-throughput imaging and automated image analysis.

Jana Lasser is a PostDoc at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna and the Medical University Vienna. She works on modelling complex social systems with a focus on the connection between social & societal dynamics and mental & physical health. She is a member of the N² advisory board and was spokesperson of the Max Planck PhDnet in 2018.

On power and its corrupting effects: the effects of power on human behavior and the limits of accountability systems

Affiliation.

- 1 Independent Scholar, Yardley, PA, USA.

- PMID: 37645621

- PMCID: PMC10461512

- DOI: 10.1080/19420889.2023.2246793

Power is an all-pervasive, and fundamental force in human relationships and plays a valuable role in social, political, and economic interactions. Power differences are important in social groups in enhancing group functioning. Most people want to have power and there are many benefits to having power. However, power is a corrupting force and this has been a topic of interest for centuries to scholars from Plato to Lord Acton. Even with increased knowledge of power's corrupting effect and safeguards put in place to counteract such tendencies, power abuse remains rampant in society suggesting that the full extent of this effect is not well understood. In this paper, an effort is made to improve understanding of power's corrupting effects on human behavior through an integrated and comprehensive synthesis of the neurological, sociological, physiological, and psychological literature on power. The structural limits of justice systems' capability to hold powerful people accountable are also discussed.

Keywords: Dominance; Dominance Hierarchy; Justice systems; Power and Access; Power and Evolution; Power and Mental Health; Power and Nepotism; Power and Sex; Power and Status; Power and self-interested behavior; Power and size; Powerlessness and behavior; Social Rank; Social Status; Socioeconomic status; high power and low status; power; power addiction; power and aggressive behavior; power and ambition; power and bariatric surgery; power and bias; power and cooperation; power and corruption; power and credibility; power and dehumanizing behavior; power and demeaning behavior; power and disinhibited behavior; power and entitlement; power and gossip; power and hypocrisy; power and overconfidence; power and physical attractiveness; power and self righteousness; power and sexual harassment; power and unethical behavior; power and victimhood; structural limits of accountability systems.

© 2023 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Publication types

Grants and funding.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Abuse of Power depicted in Animal Farm Research Paper

Related Papers

English Literature and Language Review

Dr. OMAR O JABAK

The present research study attempted to provide an interpretation of George Orwell"s Animal Farm as an outcry against false revolutionary leaders who go back on their promises and turn into dehumanized dictators even worse than the dictators against whom they and their fellow revolutionaries rebelled. To achieve that objective, the researcher read the novella critically within its socio-political context and traced the transformation of the leading character, Napoleon, who stands for such revolutionary leaders. The data of the current research were all extracted from Orwell"s Animal Farm. The researcher used content analysis to analyze the selected data and developed an analytical comparison through which he closely examined Napoleon"s character before and after the revolution. The findings of the study revealed that Napoleon was an opportunistic revolutionary who used the revolution to an evil end. Napoleon"s dramatic transformation from a noble revolutionary into a ruthless, corrupt ruler proved that Orwell"s novella can be read as an attack on false revolutionary leaders who become dehumanized despots, far worse than the dictators whom they aspired to replace with democratic leaders.

International Journal of Literature and Arts

Dlnya Mohammed

This paper studies the key roles that anthropomorphism plays in George Orwell's Animal Farm and Mark Twain's A Dog's Tale. In many ways, it is confusing when it comes to the difference between personification and anthropomorphism. To avoid this, the researcher makes a comparison between these two literary devices. Then the function of anthropomorphism is explained. Finally the purpose of anthropomorphism in the mentioned texts is made clear through textual analysis approach.

Prof.Dr.Abdul Ghafoor Awan

ABSTRACT-The main aim of this research paper is to analyze and explore Totalitarianism and its heinous impacts on any society. The other purpose of research paper is to take a deep look at Marxism with its history, principles and ideologies. The next target is exploring the terms utopia and dystopia and their creation. The next important aim of this research paper is to interlink all these terms; Totalitarianism, Marxism and Dystopia. One causes the other. The purpose of main study is the impacts of totalitarianism and Marxism towards the creation of dystopia. George Orwell’s selected fictions include Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Both of these novels fulfill the above mentioned themes and for the first time all these themes will be connected and analyzed according to these two master pieces. Totalitarianism is a form of tyrant government in which a dictator rules the country according to his own wish and desire. History is full of such totalitarian leaders. The current research paper describes the history of the Totalitarianism and totalitarian dictators. The next resort is Marxism which is work of Karl Marx and he openly described themes, principles and ideologies of Marxism. Marxist study is embellished with capitalism in which a ruler or the upper class works to get control of the economy while exploiting the lower class. The dangerous impact of totalitarianism and capitalism is that it generates dystopian society and George Orwell’s novels are perfect choice for this research paper.

Mamadou Moustapha Sangharé

Ardeniz Özenç

George Orwell, the penname of Eric Arthur Blair, is one of the most prominent English writers of 20th century (Ash). He is best known for his fable Animal Farm, and his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (Rossi and Rodden 8-10). Orwell is generally considered to be a “political writer” (Rossi and Rodden 1). However his political views conformed to neither communism nor capitalism, which were the major political ideologies that governed the world politics in the first half of the 20th century. He has a unique understanding of socialism that contradicts the Stalinist Communism of his age and capitalist ideology in general. His idea of socialism is based on a classless, egalitarian society in which the state has the responsibility to provide its citizens with equal rights and equal opportunities, so that every individual is capable of thinking for themselves. Especially, for the purpose of drawing attention to the conditions of the poor and oppressed, Orwell got down among the poorest people and produced a body of work dealing with poverty and social injustice, as well as other works dealing with the violation of basic human rights by totalitarian oppression. The aim of this paper is to analyse the development of Orwell’s understanding of socialism through analysing some of his works: The Road to Wigan Pier, Homage to Catalonia, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Michael Makovi

George Orwell is famous for his two final fictions, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. These two works are sometimes understood to defend capitalism against socialism. But as Orwell was a committed socialist, this could not have been his intention. Orwell's criticisms were directed not against socialism per se but against the Soviet Union and similarly totalitarian regimes. Instead, these fictions were intended as Public Choice-style investigations into which political systems furnished suitable incentive structures to prevent the abuse of power. This is demonstrated through a study of Orwell's non-fiction works, where his opinions and intentions are more explicit.

Majid Khorsand

Mubarak Muhammad

RELATED PAPERS

Goran O . Mustafa

Rıdvan Korkut

International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education

SMART M O V E S J O U R N A L IJELLH

Susan McHugh

Iain Munro , Julie Labatut , john desmond

Rebin Najmalddin

International Journal of Science and Research

Amin Amirdabbaghian

SKIREC Publication- UGC Approved Journals

Harjot Singh

The Cambridge Companion to George Orwell

Morris Dickstein

Th. Horan (ed.), Critical Insights: Animal Farm, Ipswich Mass., Salem Press, 2018

Dario Altobelli

Ilha do Desterro A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies

Amin Amirdabbaghian , KRISHNAVANIE SHUNMUGAM

Andrew N. Rubin

Farhad Ahmad

Tom Ue, FRHistS

Joshua B . Gardiner

Talita Panikashvili

Anastacia Babenko

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Examining the Relationship Between Leaders' Power Use, Followers' Motivational Outlooks, and Followers' Work Intentions

Taylor peyton.

1 School of Hospitality Administration, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States

2 Valencore Consulting, Cambridge, MA, United States

Drea Zigarmi

3 The Ken Blanchard Companies, Escondido, CA, United States

4 University of San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States

Susan N. Fowler

From the foundation of self-determination theory and existing literature on forms of power, we empirically explored relationships between followers' perceptions of their leader's use of various forms of power, followers' self-reported motivational outlooks, and followers' favorable work intentions. Using survey data collected from two studies of working professionals, we apply path analysis and hierarchical multiple regression to analyze variance among constructs of interest. We found that followers' perceptions of hard power use by their leaders (i.e., reward, coercive, and legitimate power) was often related to higher levels of sub-optimal motivation in followers (i.e., amotivation, external regulation, and introjected regulation). However, followers who perceived their leaders used soft power (i.e., expert, referent, and informational power) often experienced higher levels of optimal motivation (i.e., identified regulation and intrinsic motivation), but further investigation of soft power use is warranted. The quality of followers' motivational outlooks was also related to intentions to perform favorably for their organizations.

Introduction

This study merges two fields of investigation: forms of leadership power stemming from empirical research on the psychology of power over the last five decades, and motivational outlooks from research on self-determination theory (SDT) over the last 40 years. Researchers in both areas have called for greater in-depth exploration of the relationship between leadership and motivation in organizational settings (eg., Elias, 2008 ; Stone et al., 2009 ; Meyer et al., 2010 ; Randolph and Kemery, 2011 ; Anderson and Brion, 2014 ).

Much of the research on the psychology of power is “still largely removed from the complexities and confounds of behavior in organizational settings” (Anderson and Brion, 2014 , p. 85). While laboratory studies have certain strong advantages, future research will need to grapple with the dynamics of interpersonal and psychological interactions, and related implications for organizational life (Anderson and Brion, 2014 ).

Podsakoff and Schriesheim ( 1985 ) called for investigations of the independent contributions different power bases make to explain variance in criterion variables relevant to subordinate outcomes. Also, Elias ( 2008 ) identified a need for more research on specific criteria that facilitate leaders' decisions regarding the kind of power they should exercise. In response to these calls and other apparent gaps in the literature, studies began to appear. For example, Mossholder et al. ( 1998 ) found that subordinates' perceptions of procedural justice fully mediated the relationship between ratings of their supervisors' use of five forms of social power, and job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Ward ( 1998 ) also studied subordinates' perceptions of their managers, and found that for four of eight aspects of psychological work climate, managerial power bases interacted with subordinates' manifest needs (achievement, dominance, autonomy, and affiliation). Notably, managers' use of personal power (expert and referent) had the biggest impact on psychological climate, especially when personal power use also occurred with reward power use (Ward, 1998 ). Politis ( 2005 ) examined relationships between five forms of managerial power and credibility, with employee knowledge acquisition attributes. Politis ( 2005 ) uncovered a positive relationship between expert power and knowledge acquisition attributes including negotiation, control, and personal traits; also, the study found that greater use of coercive and referent power related to lower levels of knowledge sharing and knowledge acquisition. Additionally, Pierro et al. ( 2012 ) discovered how supervisors' and subordinates' need for cognitive closure related to the efficacy and application of various social power bases, specifically regarding: employee preference for soft or hard power, subordinates' performance, and other organizational outcomes. Pierro et al. ( 2013 ) found positive relationships between transformational/charismatic leadership and subordinates' inclinations to comply with soft power, which was also indicative of higher levels of affective organizational commitment.

While the above studies demonstrate some of the work on power bases as they relate to criterion variables in accordance with calls from Podsakoff and Schriesheim ( 1985 ) and others, very few studies examine the connection between motivation and forms of power use, and SDT has not yet been comprehensively applied in these investigations. Power is an undeniable aspect of leadership, and we agree with other authors (i.e., Aguinis et al., 1994 ; Randolph and Kemery, 2011 ) who maintain that there is not enough is known about the degree to which employee perceptions of their managers' use of various forms of power is correlated with various forms of employee motivation.

Scholars in the field of SDT have made similar calls for more in-depth research connecting leadership behavior to motivation in organizational settings (e.g., Deci and Ryan, 2002 ; Stone et al., 2009 ). Some SDT researchers have requested a closer examination of how leadership qualities and interpersonal styles of managers influence their followers' tendencies to align their personal goals with organizational goals (i.e., Gagné and Deci, 2005 ). Other SDT researchers call for the examination of how leader behaviors can foster increased levels of intrinsic motivation in followers (e.g., Jungert et al., 2013 ). Still other SDT authors ask for research on how leaders might optimize employee engagement in organizational settings (Dysvik and Kuvaas, 2010 ).

A preponderance of the SDT literature and its core principles has been applied in settings other than business (Deci and Ryan, 2002 ; Ryan and Deci, 2017 ). While some business leaders may have a cursory awareness of the fundamental concepts of SDT (such as the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence), few understand how to successfully support employees' needs in the face of organizational pressures for performance and output (Stone et al., 2009 ). Much of the present organizational psychology depends upon the “carrot and the stick” strategy for motivation and command-and-control methods for performance and behavior (Stone et al., 2009 ; Fowler, 2014 ). Here we explore the impact of various kinds of leadership power on non-power holders in organizations. We are interested in gaining insight into how a non-power holder's motivational outlooks may relate to their leaders' use of power in the workplace.

Purpose and Organization of the Study

This study aims to answer calls from researchers in both fields of investigation by empirically examining the relationship between leaders' use of various forms of power, followers' motivational outlooks, and followers' work intentions in organizations. Specifically, we propose to answer Podsakoff and Schriesheim ( 1985 ) call “to assess the independent contribution of each of the power bases to the variance explained in subordinate criterion variables” (p. 406). This study, is also directed toward the third research avenue suggested by “to consider putting future research efforts into those who are powerless” (Strum and Antonakis, 2015 , p. 157). In response, we focus on the intrapersonal experiences of followers who operate under their leaders' power. We examine the degree to which the perceived use of six forms of leader power might explain variance in follower motivation (i.e., its sub-forms), and follower work intentions. We consider existing literature on power and SDT to hypothesize that leaders' use of different kinds and combinations of power is connected to various motivational outlooks and work intentions in the non-power holder.

Review Of The Literature On Leader Power, Employee Motivation, And Employee Work Intention

Leader power.

Power typically entails a condition in which some individuals have control over resources and some do not. The term power is most commonly defined as “the asymmetric control over valued resources” (Anderson and Brion, 2014 , p. 69). Power relationships are inherently social and exist only in relation to others; parties with low power rely on parties with high power to obtain rewards and avoid punishment (Vince, 2014 ).

For leaders to be effective they must be able to shape the behavior of others (Elias, 2008 ). Forms of leader power that can be used to shape others behavior are embedded in people's psyches (Vince, 2014 ) through the structural features of today's organizations (Pfeffer, 1992 ; Clegg et al., 2006 ; Vince, 2014 ). Before the turn of this century, much of the literature concerned with leader power has been sociological or philosophical in origin and character (Elias, 2008 ; Anderson and Brion, 2014 ) and has traditionally dealt with the “social structure of corporations” (Clegg et al., 2006 , p. 387). The structural perspective of power (Pfeffer, 1992 ) has given rise to the foundation of systems of authority and the formation of legitimate social power relationships (e.g., Pfeffer, 1992 , 2011 ; DuBrin, 2009 ; Haugaard and Clegg, 2012 ; Lunenberg, 2012 ; Vince, 2014 ).

Leaders in the workplace may reinforce their power through their own demeanor and behavior, but they are ordained with their power by the organizational context (e.g., the authority to control resources, followers assigned to work under them), which includes higher-ranking small groups or strategic decision makers (Anderson and Brion, 2014 ). The antecedents for the bases for power stem from the social structure, the cultural patterned behavior of groups, and other practices within organizations (Lukes, 1974 , 2005 ). Much of the early literature on power was concerned with the character, skills and personality of the designated leader, with the organization's structures, policies, procedures, and with forms of hierarchy that authorize a leader's power (Foucault, 1982 ).

The bases of power (French and Raven's, 1959 ; Raven, 1965 ), which will be described next, define forms of power observed from human and contextual factors, whereas the psychology of power is concerned with how people perceive and experience the power bases, either when they hold the power themselves, or when they are under the power of others. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, there has been a rise in the number of empirical studies on the psychology of power, as researchers have recently begun to explore psychological perceptions of power to better understand how power use affects individuals in an organizational context (Anderson and Brion, 2014 ). There has been a shift away from studying power as it resides in structures, policies, and procedures, and a shift toward studying individual perceptions that are held by power/non-power holders when various uses of power occur. Recent work on individual perceptions includes, for example: studies concerned with why power facilitates self-interested behavior (DeCelles et al., 2012 ); how people who are primed with high- vs. low-power tend to adopt the visual perspective of others, adjust to other people's points of view, and feel empathy for others (Galinsky et al., 2006 ); and how power influences people's thinking while resolving moral dilemmas (Lammers and Stapel, 2009 ). Additionally, we agree with other researchers (e.g., Farmer and Aguinis, 2005 ; Dambe and Moorad, 2008 ) who have noted that most studies on power have predominantly focused on the power holder and not on either the mutuality of the power holder and the non-power holder, or on the perspective of the individual non-power holder.

Various Bases of Power

French and Raven's ( 1959 ) and Raven ( 1965 ) presented five conceptual forms of leader power which have been the basis of 50 years of research (Elias, 2008 ). These five forms of leader power—expert, referent, reward, legitimate, and coercive power—have remained relatively constant over time, even though there have been controversial issues, such as response bias possibilities, concept overlap, and single-item measurement (cf. Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ). To date, French and Raven's ( 1959 ) five forms of power are frequently used for the study of power in organizations.

Subsequently, Raven refined the five concepts of power from the earlier 1959 publication by adding a sixth major form of power, informational power, and further differentiated types of legitimate power into legitimate reciprocity, legitimate equity, and legitimate dependence (Raven, 1993 ). Additionally, coercive power was divided into personal coercive power and impersonal coercive power (Raven et al., 1998 ), and reward power was separated into personal reward power and impersonal reward power (Raven et al., 1998 ). These changes were made in an effort to overcome some of the concerns raised by Podsakoff and Schriesheim ( 1985 ) and Yukl and Tracy ( 1992 ), among others (Raven et al., 1998 ).

Alternatively, some researchers have classified varying forms of power into two clusters, i.e., soft and hard power, based on the amount of perceived freedom employees have in responding to the types of power used by their managers (e.g., Raven et al., 1998 ; Pierro et al., 2008 ; Randolph and Kemery, 2011 ). Expert power, informational power, and referent power are referred to by these and other authors as soft forms of power, while coercive, reward, and legitimate power have been classified as hard forms of power. Hard types of power require higher levels of non-power holder compliance and result in lower levels of autonomy.

Expert power depends on perceptions of the follower regarding the influencer's superior knowledge (Raven et al., 1998 ). The strength of this power turns upon the amount of expertise or knowledge the follower attributes to the influencer on a specific topic (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ). Informational power refers to the influencer's perceived capacity to provide a rationale to the follower regarding why the follower should change his or her beliefs or behaviors (Raven et al., 1998 ). Referent power is dependent on the follower's perceived personal identification with the influencer (Raven et al., 1998 ). The basis of this power stems from the extent to which the follower's personal self-identity is made better through interaction with the influencer or the desire of the follower to be like, or associated with, the influencer (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ).

Coercive power is defined as the perceived ability of the leader to penalize the targets if they do not adhere to requested outcomes (Raven et al., 1998 ). The potency of coercive power lies in the perceived extent of the punishment possible, and its use often correlates with increased negative affect between leader and follower (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ). Reward power originates from a perceived possibility of monetary or non-monetary compensation (Raven et al., 1998 ). The intensity of reward power heightens with an increase in the rewards possible, and with its relative attractiveness to the receiver (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ). Legitimate power originates from the subordinate's perceived understanding of the leader's right to influence (Raven et al., 1998 ). The potency of legitimate power arises from the internalized values the follower has concerning the authority or right of the leader to be the leader (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ).

Correlates and Outcomes of Power

The nature of power is inherently a double-edged sword in which some people have prerogatives and others do not. This realization has given rise to research on self-interested behavior and the misuse of various forms of power, the subsequent examination of psychological explanations (e.g., Galinsky et al., 2006 ; Lammers and Stapel, 2009 ; DeCelles et al., 2012 ), and resultant possible solutions, such as empowerment (e.g., Conger and Kanungo, 1988 ; Randolph and Kemery, 2011 ).

Research studies in the last two decades reveal that the use of various forms of power correlates with various desirable and undesirable organizational and individual outcomes. For example, greater use of soft kinds of power (expert, referent, and informational power) are connected to higher levels of organizational citizenship behavior, empowerment, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction (e.g., Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ; Elias, 2008 ; Randolph and Kemery, 2011 ), whereas the use of hard forms of power (coercive, reward, and legitimate) are related to greater absenteeism, lower productivity, lower self-confidence levels, and burnout (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ; Elias, 2008 ; Randolph and Kemery, 2011 ).

Employee Motivation and Self-Determination Theory

The concept of motivation in this study originates from the fundamental tenets of SDT, which have been researched and confirmed in the past five decades. This theory holds that individuals are volitional, able to initiate behaviors (Deci and Ryan, 1985 , 2002 ) and that individuals thrive when their psychological needs are satisfied (Deci and Ryan, 1985 , 2002 ). SDT purports that the individual cognitively process their experience which results in self-direction through flexible psychological structures that allow individuals to direct action toward the achievement of desired ends (Ryan and Deci, 2017 ).

Additionally, SDT researchers (e.g., Deci and Ryan, 1985 ; Ryan and Deci, 2000 ) maintain that an individual's actions are self-determined when they are chosen and supported by personally defined boundaries rather than being coerced, pressured, or induced through incentives. The term self-determination connotes a sense of self-management or self-regulation that, over time, brings with it goal direction, energy, persistence, and intention (Ryan and Deci, 2000 , 2017 ). In other words, individuals can understand why they behave the way they do. SDT purports that individuals can understand the causality of their actions, develop causality orientations (implicit and explicit, Deci and Ryan, 1985 ), and regulate their future behaviors to be congruent with such orientations.

SDT emphasizes that individuals' psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence must be fulfilled (Deci and Ryan, 1985 , 2002 ). Rather than focusing upon the lessening of physiological drives of sex, hunger, thirst, and pain avoidance, lasting human motivation originates from intrinsic needs for integration and growth (Deci and Ryan, 1985 ). Given that there is a spectrum of needs, frequent interactions with the environment allow for the fulfillment of basic psychological needs for thriving and flourishing, that encompasses more than physiological satiation (Deci and Ryan, 2002 ). The basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence, often designated as “psychological nutriments,” are as mandatory as physiological nourishment for human psychological development and well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000 , p. 75). These basic psychological needs can give rise to various forms of motivational regulation and their associated motivational outlooks.

SDT defines two broad categories of motivational regulation: controlled regulation and autonomous regulation. Controlled regulation entails participation in an activity for instrumental reasons, rather than for reasons of pleasure or being interested in the activity for the sake of the activity itself (Gagné and Deci, 2005 ; Meyer et al., 2010 ). Autonomous regulation is designated as a person's participation in an activity for its own sake, because it is pleasurable or because it is of interest (Gagné and Deci, 2005 ; Meyer et al., 2010 ). Within controlled and autonomous regulation, SDT postulates various sub-categories or motivational outlooks: external, introjected, identified, and intrinsic. In this paper, we use the terms for motivation, such as motivational outlooks or forms regulation offered by Gagné et al. ( 2015 ).

An external motivational outlook is driven by desired rewards or punishment avoidance (i.e., controlled regulation). An introjected motivational outlook is connected to ego enhancement or to the avoidance of guilt or shame (i.e., controlled regulation). External and introjected motivational outlooks are classified as controlled regulation, in that they originate from instrumental outcomes or external conditions (Gagné and Deci, 2005 ).

An identified motivational outlook is a state in which the individual participates in activities to be congruent with valued personal goals (i.e., autonomous regulation). The identified motivational outlook usually stems from willful actions that adhere to stated values. If, after reflection, the individual believes he/she has chosen at will to engage in an activity because it is congruent with his/her fundamental needs and values, a sense of autonomy is obtained (Ryan and Deci, 2000 ; Gagné and Deci, 2005 ). And finally, an intrinsic motivational outlook is a state in which a personal sense of self is expressed by the individual when participating in an activity (i.e., autonomous regulation) (Gagné and Deci, 2005 ; Meyer et al., 2010 ). Identified or intrinsic motivational outlooks are categorized as autonomous regulation.

Apart from the motivational regulations, a state of amotivation, or disinterest, can occur when people lack the volition to act—or act passively—toward a specific outcome. Amotivation may exist because of forces beyond the individual's control. This feeling of helplessness may stem from uncontrollable or unpredictable environmental factors, or it could happen because the individual was overwhelmed by thoughts and feelings from within, such as anger, rage, resignation, or despair (Deci and Ryan, 1985 ). It is possible that employees may carry out their tasks mindlessly and without purpose or care, with little regard for their performance. External and introjected regulation are different from amotivation because, in the former, the motivation of the individual expresses a modicum of volition for some specific outcome.

We use the language “sub-optimal” and “optimal” to broadly refer to clusters of motivational outlooks or states, and the distinction is based on each state's support of sustainable, long-term human flourishing. Sub-optimal motivational outlooks include amotivation, external regulation, and introjected regulation; they are classified together as sub-optimal, in that an individual's energy toward a given task is approached from a lack of interest, or from a psychological place other than positive interest or value-congruent reasons. Thus, employee performance originating from any of the sub-optimal motivational outlooks, over the long haul, will either be characterized by a lack of effort or will likely not be sustainable. Alternatively, we classify identified and intrinsic motivational outlooks (i.e., autonomous regulation) as optimal, because they involve greater fulfillment of basic psychological needs, and therefore employee efforts stemming from optimal motivation are more likely to be sustainable.

Work Intentions

In keeping with the SDT, an individual's energy for “volitional, intentional behavior originates from underlying personal needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence” (Deci, 1980 , p. 23). Here an intention is defined as a mental image of the behavior an individual plans to manifest (Bagozzi, 1992 ). Several studies have revealed that intentions are an important concept in the attitude-intention-behavior chain (e.g., Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980 ; Armitage and Connor, 2001 ). Studies testing social cognitive appraisal theory, for instance, have predicted work satisfaction from self-efficacy, positive affect, and work conditions (Duffy and Lent, 2009 ), have examined the relationship between control coping and employee withdrawal during organizational change (Fugate et al., 2011 ), have identified the relationship between appraisal/coping variables and stressful encounter outcomes (Folkman et al., 1986 ), and have uncovered relationships between consumers' behavioral intentions to use services in the future with consumer expectations, perceived quality, and satisfaction (Gotlieb et al., 1994 ).

In the fields of health and social psychology, various meta-analyses have demonstrated strong relationships between intentions and behavior (e.g., Cooke and Sheeran, 2004 ; Gollwitzer and Paschal, 2006 ; Webb and Sheeran, 2006 ). We chose to use the concept of work intentions as outcome variables because they are stronger predictors of employee behavior. Three meta-analyses conducted over the last 40 years have established that intentions are better predictors of employee behavior than outcome variables, such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction (e.g., Steel and Ovalle, 1984 ; Tett and Meyer, 1993 ; Podsakoff et al., 2007 ).

This research explores possible relationships between followers' perceptions of their leader's use of different kinds and combinations of power, various types of motivational outlooks in followers, and five work intentions held by followers. See Figure 1 for our conceptual model.

Overall conceptual model.

Very little empirical testing of the relationships between power and motivation exists in the literature, so the main impetus for our hypotheses is theoretical. Our underlying logic regarding followers' motivational outlooks assumes that the non-power holders' basic psychological need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence will be met or not met, facilitated are not facilitated, through the leader's use of various forms of power, hard or soft. The theoretical justification for these hypotheses lies in the followers' experience of the quality of: choice or autonomy given by the leader, relatedness cultivated by the leader, and competence experienced in relationship to the leader.

Specifically, we point to the research on human choice. Building on the work of SDT researchers, Patall et al. ( 2008 ) included 41 studies in a meta-analysis examining the effects of choice on intrinsic motivation. The authors concluded that intrinsic motivation was stronger when choice was given, and when rewards were not given. According to SDT, when a person's basic psychological needs (autonomy, relatedness, competence) are met, they thrive and behave in more self-determined (or optimally motivated) ways. Giving a person a choice relates to their experience of autonomy, one of the three basic psychological needs. Definitions of various forms of power (i.e., Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985 ; Raven et al., 1998 ; Pierro et al., 2008 ) suggest that coercive power, reward power, and legitimate (i.e., hard) power provide limited opportunity for the person under these types of power to exercise choice, compared to expert, referent, and informational (i.e., soft) power. If a leader's hard power limits follower choice much more than soft power, we anticipate followers' basic psychological needs and motivation will be affected accordingly.

Also, we found two empirical studies that examined different forms of power and motivation. First, Elangovan and Xie ( 1999 ), reported many positive relationships between subordinates' levels of internal motivation and forms of power being used by their supervisors, but effects were notably stronger for subordinates with low self-esteem or external locus of control. Second, Pierro et al. ( 2008 ) reported hard power compliance positively correlated with extrinsic motivation and negatively correlated with intrinsic motivation, whereas soft power compliance was positively correlated with intrinsic motivation. Pierro et al. ( 2008 ) and Elangovan and Xie ( 1999 ) both did not frame their studies primarily in SDT, so neither study included measures of motivation that captured the various subscales of motivation comprehensively defined by SDT.

Given the small number of studies exploring the relationship between leader power and subordinate motivation, more research is needed. Thus, applying conclusions from the research on human choice, from SDT, and from the above literature testing French and Raven's power bases in relationship to motivation, we propose:

- Hypothesis 1a : Leaders' use of various kinds of hard power will positively correlate with followers' sub-optimal motivation (i.e., amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation).

- Hypothesis 1b : Leaders' use of various kinds of hard power will negatively correlate with, or not correlate with, followers' optimal motivation (i.e., identified regulation, intrinsic motivation).

- Hypothesis 1c : Leaders' use of various kinds of soft power will negatively correlate with, or not correlate with, followers' sub-optimal motivation (i.e., amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation).

- Hypothesis 1d : Leaders' use of various kinds of soft power will positively correlate with followers' optimal motivation (i.e., identified regulation, intrinsic motivation).

Furthermore, leaders' use of power and followers' motivation may also relate to followers' work intentions. Zigarmi et al. ( 2016 ) examined employee locus of control, forms of motivational regulation, harmonious and obsessive passion, and desirable work intentions. While the direct connection between motivational regulation variables and work intentions in Zigarmi et al. ( 2016 ) was not estimated in their structural model, their correlation matrix showed: strong positive relationships between autonomous motivation and all five work intentions, small-to-medium negative relationships between amotivation and all work intentions, and small positive relationships between controlled motivation and three of five work intentions. Such relationships are in accordance with the assumptions of SDT, which purport that optimal motivation relates to human thriving.

Additionally, Zigarmi et al. ( 2015 ) found slight-to-moderate positive correlations between employees' perceptions of their leaders' use of expert and referent (i.e., soft) power and all favorable work intentions. In the same study, coercive and legitimate (i.e., hard) power were negatively and somewhat weakly correlated with five of ten possible work intentions, whereas reward power was somewhat positively correlated to all five work intentions. In their structural model that included positive and negative affect as mediators, Zigarmi et al. ( 2015 ) found that—except for expert power which had a negative, direct path to intent to perform—reward power and expert power each positively and directly related to two of five favorable work intentions. From that work, we observe variability in employees' intentions to perform well for their organization, relative to the kind of power their leaders use.

Considering the above, regarding the relationship between power, motivation, and work intentions, we propose:

- Hypothesis 2a : Followers' sub-optimal motivation (i.e., amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation) will negatively correlate with, or not correlate with, their work intentions.

- Hypothesis 2b : Followers' optimal motivation (i.e., identified regulation, intrinsic motivation) will positively correlate with their work intentions.

- Hypothesis 3a : Followers' motivational outlooks will partially mediate perceptions of leaders' use of various kinds of power and followers' work intentions.

- Hypothesis 4a : Followers of leaders who use multiple kinds of hard power at high levels (as compared to leaders who use lower levels of all kinds of hard power) will report higher levels of amotivation, external regulation, and introjected regulation, lower levels of (or no difference in levels of) identified regulation and intrinsic motivation, and lower levels of (or no difference in levels of) work intentions.

- Hypothesis 4b : Followers of leaders who use multiple kinds of soft power at high levels (as compared to leaders who use lower levels of all kinds of soft power) will report higher levels of identified regulation and intrinsic motivation, lower levels of (or no difference in levels of) amotivation, external regulation, and introjected regulation, and higher levels of work intentions.

Hypothesis 3a was written parsimoniously to address all substantive constructs of interest to us, as our approach to partial mediation analyses will be exploratory. Thus, any non-significant relationships we uncover from testing Hypotheses 1a − 1d and 2a − 2b will naturally affect the possibility to test partial mediation proposed by Hypothesis 3a.

In summary, we hypothesize that a leader's increased use of harder forms of power will be related to decreased quality of their followers' forms of motivation, and that less optimal motivation in employees will relate to lower levels of work intentions. Also, the more optimal forms of motivation in employees should correlate with higher levels of work intentions. While various studies we cited above provide some support for the connection between followers' work intentions relative to their motivation, and to their leaders' use of power, we have found no empirical study yet that has examined these factors together.

We conducted two studies to test our hypotheses. Study 1 involved a sample of respondents from a single organization, while Study 2 collected a larger sample of employees working across many organizations. Study 2 was conducted to determine if the findings from Study 1 could be replicated. Both studies were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Ken Blanchard Companies.

Participants for Study 1

Three-hundred seventy employees from a training and consulting organization in Southern California were invited to participate in Study 1. The sample for analysis included 229 employees, or a 62% response rate. Seventy percent of respondents were female, 78% were White/Caucasian, 22% were managers, and 60% reported being born in 1961 or later. Thirty percent had graduate degrees, 44% were college graduates, and 26% had some college education or less. Organizational tenure varied; 30% said they had been with their organization for 5 years or less, 21% reported a tenure of 6–10 years, 34% reported a tenure of 11–20 years, and 15% said they had worked for their organization for 21 years or more.

Procedures for Study 1

Participants from a single organization were invited through email to complete an online survey. Data for this study were gathered as part of a voluntary, anonymous, annual survey conducted by the company's human resources department.

In addition to demographic information, participants were asked to respond to subscales measuring their manager's use of power and the kinds of motivational outlooks they personally experience at work.

Managerial use of power was measured through the Interpersonal Power Inventory (IPI) from Raven et al. ( 1998 ). The IPI presents 11 subscales representing various power bases and is an extension of the original six power bases proposed by French and Raven's ( 1959 ) and subsequently Raven ( 1965 ). The IPI asks respondents to think of a time when they complied with their supervisor's request despite initially being reluctant to do so, then presents 33 items asking for their reason for compliance to be rated on a 7-point response scale (1 = definitely not a reason , 7 = definitely a reason ). To ensure parsimony and practicality in the interpretation of results, Study 1 combined the IPI's eleven subscales of power to measure the original six power bases: reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, expert power, referent power, and informational power. The reward and coercive power subscales each had six items, the legitimate power subscale included nine items, and the expert, referent, and informational power subscales were each made up of three items. Example items follow for each kind of power subscale used in this work: “My supervisor could help me receive special benefits” (reward power), “My supervisor may have been cold and distant if I did not do as requested” (coercive power), “I understood that my supervisor really needed my help on this” (legitimate power), “My supervisor probably knew more about the job than I did” (expert power), “I looked up to my supervisor and generally modeled my work accordingly” (referent power), and “My supervisor gave me good reasons for changing how I did the job” (informational power). Alpha coefficients for the power subscales in Study 1 ranged from 0.87 to 0.96.