20 Positive Psychotherapy Exercises, Sessions and Worksheets

The word “psychotherapy” often evokes images of nerve-wracked patients reclining on couches, a stern therapist with furrowed brows and a notepad, and a deep uneasiness linked to the identification and analysis of every childhood trauma you have suffered, whether you remembered it before the session or not.

Although this is an outdated and largely inaccurate idea of psychotherapy, it still may seem counterintuitive to combine positive psychology with psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy is typically reserved for those with moderate to severe behavioral, emotional, or personality issues—not people who are often happy and healthy, and also struggle with occasional stress.

How can this type of therapy, which deals with such serious and difficult subject matter, possibly be considered “positive?”

Fortunately, many respected psychologists have been working to develop a useful and evidence-based positive approach to psychotherapy over the last two decades.

These pioneering researchers have married the research of positive psychology and the science and practice of psychotherapy into a life-affirming alternative to traditional psychotherapy—one that focuses on your strengths instead of your weaknesses, and works towards improving what is good in life instead of mitigating that which is not (Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006).

It does not replace traditional psychotherapy, but can act as an extremely effective supplement to help a person move from “just getting by” to flourishing and thriving! For more on this effective ‘supplement’, we share a variety of exercises, tools and a range of therapy sessions.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

5 positive psychotherapy exercises and tools, 15 sessions – exercises and tools, a take-home message.

Here is an overview of some of the most effective exercises and tools in a positive psychotherapist’s toolbox.

1. Gratitude Journal

One of the simplest yet most effective exercises in positive psychology is a gratitude journal . Evidence has shown that developing gratitude for the things in your life that you may otherwise take for granted, can have a big impact on your outlook and satisfaction with your life (Davis et al., 2016; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006).

The practice of keeping a gratitude journal is quite simple and easy to explain to a client who might need a boost in positive emotions.

As a therapist or other mental health professional, instruct your client to do the following:

- Get a notebook or journal that you can dedicate to this practice every day.

- Every night before bed, write down three things that you were grateful for that day.

- Alternatively, you can write down five things that you were grateful for on a weekly basis.

- Encourage them to think of particular details from the day or week, rather than something broad or non-specific (i.e., “the warm sunshine coming through the window this afternoon” rather than “the weather”).

If your client is having trouble thinking of things they are grateful for, tell them to try thinking about what their life would be like without certain aspects. This will help them to identify the things in their life they are most grateful (Marsh, 2011).

2. Design a Beautiful Day

Who doesn’t want to design a beautiful day for themselves?

This exercise is not only fun for most clients, but it also carries a double impact: the planning of the near-perfect day, and the actual experience of the near-perfect day.

As a counselor or therapist, encourage your client to think about what a beautiful day means to them.

What do they love to do? What do they enjoy that they haven’t had a chance to do recently? What have they always wanted to do but have never tried?

These questions can help guide your client to discover what constitutes a beautiful day to them. Direct your client to pick a day in the near future and design their day with the following tips in mind:

- Some alone time is fine, but try to involve others for at least part of the day.

- Include the small details that you are looking forward to in your plan, but don’t plan out your entire day. Leave some room for spontaneity!

- Break your usual routine and do something different, whether it’s big or small.

- Be aware that your beautiful day will almost certainly not go exactly as planned, but it can still be beautiful!

- Use mindfulness on your beautiful day to soak in the simple pleasures you will experience throughout the day.

3. Self-Esteem Journal

The self-esteem journal is another straightforward but effective exercise for clients suffering from feelings of low self-worth.

This Self-Esteem Journal For Adults provides a template for each day of the week and three prompts per day for your client to respond to, including prompts like:

- Something I did well today…

- Today I had fun when…

- I felt proud when…

- Today I accomplished…

- I had a positive experience with…

- Something I did for someone…

The simple act of noticing and identifying positive things from their day can help clients gradually build their self-esteem and enhance their wellbeing. Sometimes all we need is a little nudge to remember the positive things we do!

4. Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness meditation can be an excellent tool to fight anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions, making it a perfect tool for therapists and counselors to use with their clients.

To introduce your client to mindfulness meditation, you can try the “ mini-mindfulness exercise ,” a quick and easy lesson that only takes a few minutes to implement.

Follow these steps to guide your client through the process:

- Have your client sit in a comfortable position with a dignified but relaxed posture and their eyes closed. Encourage them to turn off “autopilot” and turn on their deeper awareness of where they are, what they are doing, and what they are thinking.

- Guide them through the process of becoming aware of their breath. Instruct them to take several breaths without trying to manipulate or change their breathing; instead encourage them to be aware of how it feels as they inhale air through the nostrils or mouth and into the lungs, as they hold the air for a brief moment, and as they exhale the air again. Direct their attention to how their chest feels as it rises and falls, how their belly feels as it expands and contracts, and how the rest of their body feels as they simply breathe.

- Direct your client to let their awareness expand. Now, they can extend their focus beyond their breath to the whole body. Have them pay attention to how their body feels, including any tightness or soreness that may be settled into their muscles. Let them be present with this awareness for a minute or two, and tell them to open their eyes and continue with the session or with their day when they are ready.

Once your client is introduced to mindfulness meditation, encourage them to try it out on their own. They may find, as so many others have, that mindfulness can be a great way to not only address difficult or negative emotions but maintain positive ones throughout the day as well.

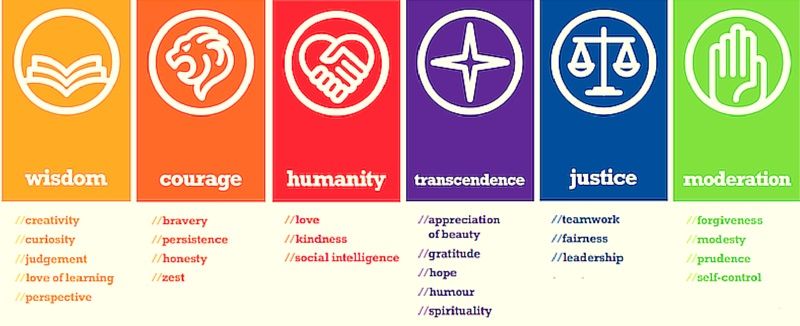

5. Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS)

The VIA-IS is one of the most commonly used tools in positive psychology, and it has applications in positive psychotherapy as well. Completing this questionnaire will help your clients identify their dominant strengths— allowing them to focus their energy and attention on using their inherent strengths in their daily life, instead of getting distracted by the skills or traits they may feel they are lacking.

The VIA-IS is reliable, validated, and backed by tons of scientific research, and best of all – it’s free to use (Ruch, Proyer, Harzer, Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2010).

Direct your clients to the VIA website to learn about the 24 character strengths and take the VIA-IS to discover their own top strengths.

These strengths are organized into six broad categories as follows:

Wisdom and Knowledge

- Creativity;

- Love of learning;

- Perspective.

- Perseverance;

- Social intelligence.

- Leadership.

- Forgiveness;

- Self-regulation .

Transcendence

- Appreciation of beauty and excellence;

- Gratitude ;

- Spirituality.

Once your client has taken the survey and identified their top 5 strengths , instruct them to bring in their results and have a discussion with them about how they can better apply these strengths to their work, relationships, recreation, and daily life.

The order of sessions outlined below is merely suggestive but there are some essential components that should be maintained to increase long term effectiveness and enhance learning.

While every session introduces new exercises and tools, it is also recommended that some form of restorative technique is used at the beginning and at the conclusion of every session.

For each session, we also suggest one homework assignment to facilitate maintenance in between sessions.

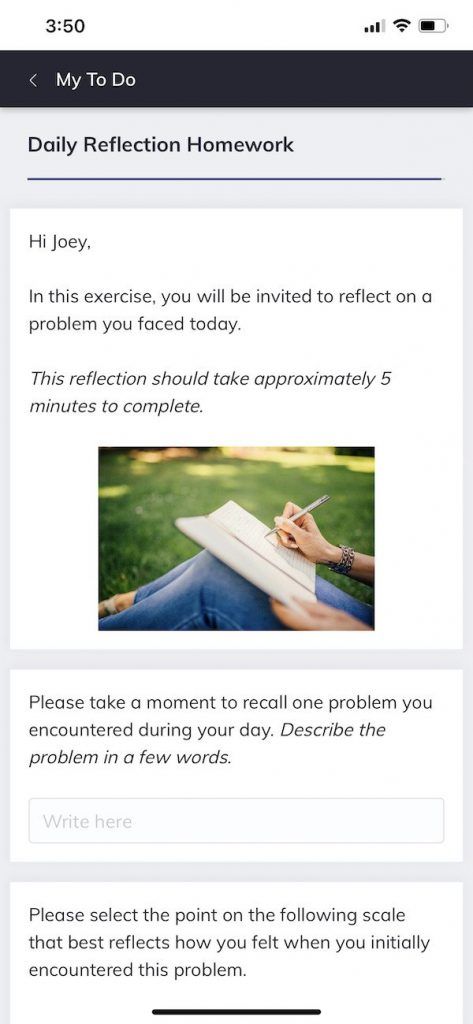

If you are a therapist who regularly assigns homework to your clients, we recommend checking out the platform Quenza to help digitize and scale this aspect of your therapy practice.

The platform incorporates a simple drag-and-drop builder that therapists can use to craft a range of digital activities for their clients to complete in between therapy sessions. These activities can include audio meditations, reflections, self-paced learning modules, and more.

Once done, the therapist can then share these activities directly to their clients’ devices, such as the Daily Reflection on the right, track their progress using Quenza’s dashboard, and send follow-up reminders to complete the activities via push notification.

Additionally, one size does not fit all when introducing any practice including mindfulness, so fit should be carefully considered and special attention should be paid to cultural considerations.

Session I – Positive Inception

Goal : Exploration of strengths and positive attributes is accomplished by inviting the client to share a personal story that shows them at their best as a form of introduction.

Tool : Positive Introduction prompt

Rationale : Initial session is intended to set a positive tone for the on-going practitioner-client interaction. Building rapport both at the outset and throughout the relationship are key factors to better outcomes from a therapeutic process.

One positive psychotherapy practice recommended for this session is a positive introduction. A positive introduction is based on principles of Appreciative Inquiry and involves asking a client to recall a positive event in his or her life that ended very well.

Positive memories can generate positive emotions and improve mood regulation. Positive narratives also help restore healthier self-concept and allow the client to build resources in terms of new ideas and perspectives (Denborough, 2014).

In-session Resources:

- Positive Introduction

Describe an event in your life where you handled a difficult situation in a positive way and things turn out well. It does not have to be a major event but try to think of something that brought out the best in you. Write about the situation in form of story with a beginning, middle and positive end: ____________

Discussion questions:

- Tell me how this event influenced how you see yourself?

- What about you specifically helped you deal with this situation?

- Are other people aware of this story in the way you described it?

Homework : As homework, clients can create anchors out of these positive memories by collecting pictures or artifacts that remind them of the pleasant memory. The practitioner can also provide the client with an option to seal this positive introduction in an envelope to be opened at a later date and kept by the practitioner for safekeeping.

Lastly, the client should be encouraged to write similar stories and keep them handy for a quick pick me up.

Practitioner can also suggest that client asks others to share their inspiring stories, that client share more stories like this one and pay attention to what they say about themselves, what themes keep recurring, how their stories change depending on audience, what role they play in their own stories and whether they are a victim or a survivor.

Clinician notes:

Pay careful attention and take notes as the narratives will tend to form sequences.

If a client has a difficulty recalling positive events, they can ask family or friends to recall for them or they can tell a story of someone they admire.

Session II – The Powers Within

Goal : To assess signature strengths and to cultivate engagement through daily activities by choosing tasks that speak to one’s strengths.

Tool : Signature Strengths Assessment

Rationale : Exercising specific strengths can facilitate goal progression and contribute to wellness and personal growth (Linley, Nielsen, Gillett, & Biswas-Diener, 2010). Psychology of motivation teaches us that there are keystone habits that spark positive changes in other areas related to the one being made, so can certain strengths support the healing and growth process. Strength assessment is given, and the concept of engagement is explained.

Preparation:

Prior to the session, the client should ask three people to report on their strengths.

In-session Worksheets:

- Your Core Values

Read carefully the descriptions of 24 character strengths below. They can be found in the VIA Institute on Character website .

Circle 5 of the strengths that you find yourself exercising most often and that you feel characterize you the most:

List your 5 signature strengths and then answer questions and prompts to determine the key markers of your signature strengths.

- Authenticity: Is this strength a part of who I am at the core?

- Enthusiasm: While using this strength I feel excited and joyous.

- Learning: Is it natural and effortless for me to use this strength?

- Persistence: I find it difficult to stop when I use this strength.

- Energy: When I use this strength, do I feel invigorated and full of zest?

- Creativity: Do I find new ways and design projects to use this strength?

Pick one or two and try to describe specific experiences or anecdotes associated with expression of that strength: _____________

Now consider the client’s peer feedback. The reports will probably not be identical, but some significant overlap is highly likely.

Circle any areas of considerable overlap and try to identify the following:

- Signature strengths – these have been mentioned several (3-4 times) by the client’s feedback providers

- Potential blind spots – strengths mentioned by others, but not the client themselves.

- How confident do you feel about knowing your signature strengths after completing the assessment?

- How well do your strengths reflect your personality?

- Which of the strengths you identified have always been there and which have you acquired at some point in your life?

- Which signature strengths stood out for you in terms of specific markers like authenticity, energy or learning?

Homework : Instruct clients to take VIA strengths survey assessment and ask that they observe if using signature strengths produces greater engagement.

Clinician notes :

Reminders are tangible cues in our environment that focus our attention on a particular commitment we made. Reminders help anchor a new habit of thought and behavior.

They can be simple or more complicated and creative like a screen saver on the clients’ phone, a bracelet or a keychain that reminds them of their signature strengths, a picture on the wall of the person who motivates them or an entry in their planner with times for a podcast that encourages them to practice and reflect.

Session III – Amplify Your Internal Assets

Goal : To gain a deeper understanding of optimal levels of usage of strengths. Use your signature strengths to be happier as well as to develop skills. Use your strengths to manage your negatives.

Tool : Optimizing Strengths exercise

Rationale : Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, and Minhas (2011) argue against just identifying one’s strengths as it represents a fixed mindset and decreases motivation. He suggests that we should treat strengths as “potentials for excellence” to foster belief in the possibility of improvement where therapy can lead us to develop them further.

Development of practical intelligence can be initiated through considering how client’s strengths can be translated into concrete purposeful actions that enhance commitment, engagement and problem-solving.

- Optimizing Strengths

Read the common scenarios below and reflect on the potential of under and overuse of strengths:

- Someone is feeling sad or appears disinterested and apathetic

- Someone obsesses over small details and worries too much about things you perceive as insignificant

- Someone is always volunteering and takes on too many commitments and projects

- Someone is often playful and humorous

- Some fail to confront another for inappropriate behavior

Discussion questions :

- What behaviors let you know you’re overusing or underusing your strengths?

- What specific circumstances trigger your overuse or underuse of strengths?

- What cultural or personal history factors could reinforce your over- or underuse of strengths?

- If you’re overusing one strength, what other strength could counterbalance that overuse?

For between sessions assignment, ask the client to describe a current challenge and then reflect on the following questions:

- Is it due to overuse or underuse of strengths?

- What aspects of this challenge would you like to change?

- What strengths can you use in this situation?

- What are the implications on others of using these strengths?

- In what way can you calibrate the use of these strengths to improve the situations?

In imparting practical wisdom strategies make sure clients perceive this as the development of a strength, not merely as use of a well-developed strength. Practical wisdom strategies are:

- Translate strengths into specific actions and observe the outcome

- Consider if strengths are relevant to the context

- Resolve conflicting strengths through reflecting on the possible outcomes of the use of these strengths

- Consider the impact of your strengths on others

- Calibrate according to changing circumstances

Session IV – You at Your Best

Goal : Visualize a better version of yourself.

Tool : You at Your Best Worksheet

Rationale : Our visions of who we wish to become in the future, be it our best selves, our ideal selves or simply our better selves, reflect our personal and professional goals and are created by imagining a better version of who we are today and then striving toward it.

Cultivating and sustaining desirable action can bring us closer to that future self and it may require that we refrain from behaviors that deter us and change old habits that don’t serve us.

Ideal selves reflect our hopes, dreams, and aspirations, and speak to our skills, abilities, achievements, and accomplishments that we wish to attain (Higgins, 1987; Markus & Nurius, 1986).

Research supports this phenomenon of movement toward ideal selves and shows that it predicts many positive outcomes: life satisfaction, emotional wellbeing, self-esteem, vitality, relational stability, relational satisfaction (Drigotas, 2002; Drigotas, Rusbult, Wieselquist, & Whitton, 1999; Kumashiro, Rusbult, Finkenauer, & Stocker, 2007; Rusbult, Kumashiro, Kubacka, & Finkel, 2009).

- You At Your Best

1. Find your story.

Recall a recent time or event when you were at your absolute best. You might have been overcoming a serious challenge, or perhaps you made someone else’s life better.

Think about what made you feel happier, more alive. Maybe you were:

- more relaxed,

- more grounded,

- more enthusiastic,

- more energized,

- more engaged,

- more creative,

- more connected,

- more reflective,

Describe your story as clearly as possible, allowing the details in your narrative to demonstrate your strengths and values.

What happened? What was your part in it? How did you feel?

3. Beginning, Middle, End

Craft your narrative with a start, middle, and powerful ending. It may help to replay the experience in your mind as it happened.

Highlight or circle any words that you feel might relate to your personal strengths.

5. Find your Strengths

List the strengths you’ve identified from the exercise.

- How can you move toward this better version of you?

- How can you use your signature strengths?

- What concrete action can you commit to?

- What barriers do you see and what and who can help?

- How different is your life once you’ve made the change?

Homework : Commit to specific actions for the week. Name someone who is willing to support you. Decide on how often this person will check in on your progress and how.

Clinician notes : Remind the client that less is more, and that a long list is bound to fail because cognitive overload is likely to lead them to do nothing. Modest aspirations translate into small wins that lead to gradual change. Reinforcing new behaviors takes time and failure is a normal part of the process. Remind the client that they are more likely to succeed on their fifth or sixth attempt.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Session V – Positive Reappraisal

Goal : Open and closed memories are reappraised through four different methods.

Tools : Open and Closed Memories Questionnaire, Positive Reappraisal exercise

Rationale : Personal written disclosure is employed to explore resentment and painful memories and to encourage cognitive processing using your strengths in order to re-file them so that they don’t drain your energy.

The purpose of positive appraisal is not to change the event or the person involved in these negative memories but to refile then in a way that does not continue to drain us emotionally or psychologically.

- Open and Closed Memories Questionnaire

Please answer the following questions to determine if you have open memories:

- Does my past prevent me from moving forward?

- Does your open or negative memory involve someone who harmed you and you find yourself thinking about this person or the consequences of their actions?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of engaging in this processing of painful memories?

- Have you sought another person’s perspective on this issue?

Now apply the following positive reappraisal strategies to one of your memories:

- Create some distance. One way to create a psychological space between you and your negative memory is to describe from this person’s perspective to allow yourself to revise the meaning and the feelings around it. Imagine yourself as a journalist or a fly on the wall and describe your open memory from a vantage point of a third person while keeping a neutral expression.

- Reinterpret by focusing on subtle aspects of the memory and deliberately recall any positive aspects you may have missed while keeping the negatives at bay. Think of your values in life and how those can be infused in how you remember.

- Step back and observe your memory unfold with a non-judgmental receptive mind and shift focus to internal and external experiences evoked by the memory. See if you can allow your memory to pass by.

- Divert your attention to a different task that is engaging.

- Which strategy was most beneficial?

- Which strategy was difficult to do?

- How has this experience put your life in perspective for you?

- How has this event benefited you as a person?

- What personal strengths grew out of this experience?

- How has this experience helped you see differently what and who is important in your life?

Homework : Apply one of the strategies to a new challenge and reflect on it in writing before the next session.

Clinician notes : A level of caution needs to be exercised when exploring painful memories. Encourage the client to explore a memory that is not too traumatic. Start the session with a mindfulness practice and ask the client to monitor their emotional state.

Session VI – Forgiveness is Divine

Goal : Model of forgiveness is introduced, and the letter of forgiveness is assigned to transform bitterness.

Tool : REACH Forgiveness worksheet and Forgiveness Letter.

Rationale : Forgiveness is a choice, although not an easy one. It is a gradual process that requires commitment. Decisional forgiveness is only the first step. Empathy is key and ultimately forgiveness is a gift you give to yourself.

Everett Worthington (n.d.), leading research in forgiveness, designed a model that outlines the necessary components of effective emotional forgiveness and the worksheet below is based on his REACH method. You can find an extensive discussion of the psychology of forgiveness in our blog.

One model of forgiveness therapy that places empathy at its center and stresses emotional forgiveness is Worthington’s REACH forgiveness model based on the stress and coping theory of forgiveness. Each step in REACH is applied to a target transgression that the client is trying to change.

R = Recall the Hurt E = Empathize with the Person Who Hurt You A = Give an Altruistic Gift of Forgiveness C = Commit to the Emotional Forgiveness That Was Experienced H = Hold on to Forgiveness When Doubts Arise (Worthington, 2006).

- REACH forgiveness

Follow the reach model in your written narrative of forgiveness:

- R = Recall the Hurt. Close your eyes and recall the transgression and the person involved. Take a deep breath and try not to allow self-pity to take over. Write briefly about what happened: ___________

- E = Empathize with the Person Who Hurt You. People often act in hurtful ways when they feel threatened, afraid or hurt. Do your best in trying to imagine what the transgressor was thinking and feeling and write a plausible explanation for their actions. This part is supposed to be difficult: ___________

- A = Give an Altruistic Gift of Forgiveness. Remember a time when you were forgiven by another person. Describe the event and its effect on you: ____________

- C = Commit to the Emotional Forgiveness That Was Experienced. Commit to a gesture of forgiveness, public or private, either by sharing with someone your decision to forgive or by writing a forgiveness letter that you never send.

- H = Hold on to Forgiveness When Doubts Arise. Recurrence of memories will be normal but the reminder you created above will be helpful in holding onto your decision to forgive. Brainstorm ways in which you can support your resolution as well as those that may deter you.

A key to helping a person develop empathy for the transgressor is to help the client take the perspective of the other person. To assist the client, write the five Ps on a sheet of paper as a cue to the client and ask them to answer the questions using the five prompts:

- Pressures: What were the situational pressures that made the person behave the way he or she did?

- Past: What were the background factors contributing to the person acting the way he or she did?

- Personality: What are the events in the person’s life that lead to the person having the personality that he or she does?

- Provocations: What were my own provocative behaviors? Alternatively, might the other person, from his or her point of view, perceive something I did as a provocation?

- Plans: What were the person’s good intentions? Did the person want to help me, correct me, or have in mind that he or she thought would be good for me, but his or her behavior did not have that effect? In fact, it had just the opposite effect.

Homework : Leslie Greenberg and Wanda Malcolm (2002) have demonstrated that people who can generate fantasies where they vividly imagine the offender apologizing and being deeply remorseful are ones who are most likely able to forgive successfully.

Ask the client to vividly imagine the offender apologizing and then write a letter of forgiveness to this person. The client does not need to do anything with the letter itself.

Clinician notes : Although relaxation techniques should be used at the outset and at the conclusion of every session, this one, in particular, is important.

If the client has a difficulty finding compassion for the transgressor, one of the most effective ways to help a client experience empathy is to use the empty-chair technique.

The client imagines sitting across from the offender, who is imagined to be in an empty chair. The client describes his or her complaint as if the offender were there. The client then moves to the empty chair and responds from the point of view of the offender. The conversation proceeds with the client moving back and forth between chairs.

The objective is to allow the person to express both sides of the conversation personally, and thus experience empathy. In doing so, the person might imagine an apology or at least an acknowledgment of the hurt that was inflicted.

Session VII – Good Enough

Goal : To establish realistic expectations of progress. Good enough mindset and concepts of satisficing versus maximizing are introduced, and an action plan to increase satisficing is devised.

Tool : Maximizer v. Satisficer Assessment, Strategies to Increase Satisficing

Rationale : According to psychologist Barry Schwartz (2004), maximizers always aim to make the best possible choice. They take their time and compare products both before and after making purchasing decisions.

Maximizers are more prone to depression due to overly high expectations and fear of regret. Maximizers, like perfectionists, seek to achieve the best, but perfectionists have high standards that they don’t expect to meet, whereas maximizers have very high standards that they do expect to meet, and, when they are unable to meet them, they become depressed (Chowdhury, Ratneshwar, & Mohanty, 2009; Schwartz et al., 2002).

The questionnaire below will help to assess if your client is a maximizer or a satisficer. There are several techniques for increasing satisficing and developing a “good enough” mindset.

- Maximizer v. Satisficer Assessment

Read the following statements and carefully rate to what degree they are true and descriptive of who you most often are. Rate them on a scale of one to seven, where one means completely disagree and seven means strongly agree.

Now add the scores for your answers. The average score is 50, the high score is 75 and the low score is 25 or below. If your score is below 40, you are on the satisficing end of the scale. If you scored 65 and above, it is likely you have maximizing type behaviors that may impact your wellbeing. Consider some of the strategies to increase satisficing listed below.

Strategies to Increase Satisficing

To make choices versus simply have choices means to be able to reflect on what makes a decision important, what makes particular choice say about you, or even create new options if no good options are available. To practice these skills, try the following:

- Shorten or eliminate deliberation about decisions that are not important.

- Take the time that has just become available to you to ask yourself what you really want in the areas of life where making decisions really matters.

To generally do more satisficing, try the following:

- Recall the time when you settled for good enough.

- Reflect on how you chose in those areas.

- Apply the strategy to another area.

Reflect on what pursuing all the available opportunities costs you:

- Make a decision to stick with a decision to do something unless you’re truly dissatisfied.

- Resist the urge to go after the new and improved.

- Resolve to combat the fear of missing out.

- Adopt the attitude where you don’t fix what’s not broken.

Imagine there is no going back. Make your decision irreversible and final to limit the amount of time you waste processing the alternatives:

- Make a list of reversible decisions.

- Now pick some of those decisions to be made irreversible.

Practice attitude of gratitude and being grateful for what you have and the good aspects of the choices you have made and resolve not to ruminate what was bad about them:

- Pick a few decisions you’ve made to practice this attitude.

Having regrets can influence our ability to make a decision to a point of us avoiding to make them. Make an effort to minimize regret where appropriate:

- Reduce the number of options before making a decision.

- Focus on what is good about making the decision.

- Identify yourself as a satisficer versus maximizer.

Adaptation, also known as the hedonic treadmill, robs us of satisfaction we can get from a positive experience. Combat adaptation and develop realistic expectations about how experiences change over time:

- Next time you purchase something fully consider how long the thrill of owning it will last.

- Vow to spend less time looking for a perfect match.

- Create a reminder to yourself to appreciate how good things really are versus how they are less than what they originally were.

Lower your expectations. Our satisfaction with experiences is determined to a large extent by our expectations. To increase satisfaction with results, try the following:

- Reduce the number of options you will consider.

- Allow for serendipity.

- Ask yourself what a satisficer would do in this situation.

Beware of social comparisons. Practice not comparing yourself to others as quality of experience can be significantly reduced by comparing yourself to others:

- Focus on what makes you happy and what gives meaning to your life.

- Limit the use of social media when you feel the urge to compare your life to that of others.

Appreciate constrains. Our freedom of choice and ability to decide decreases as our options increase. Our society provides rules by which we are limited in forms of laws and norms of behavior.

- Create your own list of rules that you are willing to practice to increase your ability to make effective choices.

- What does your satisficer versus maximizer score say about you?

- If you scored high, what are the emotional or physical costs of maximizing?

- In what way knowing your tendencies can help you make meaningful changes in your life?

Homework : Ask the client to practice one or more techniques of satisficing throughout the week.

Clinician notes : Repetition just like regular reminders can aid the client in creating lasting change. Together repetitive action and repetition create ritual over time. Encourage clients to build new positive habits of thinking and behaving.

Session VIII – Count Your Blessings

Goal : The notion of counting one’s blessings and enduring thankfulness is discussed, gratitude exercise is introduced, and blessings journal is assigned.

Tool : Three Good Things and Gratitude Visit

Rationale : Extensive research shows that enduring thankfulness has many health benefits (Emmons, 2007). In one clinical study, the gratitude condition participants reported significantly better mental health than those in the expressive and control conditions.

This session introduces the client to the practice of gratitude by counting one’s blessings daily and planning a gratitude visit. Clients are also asked to keep a gratitude journal between sessions.

Three Good Things

Before going to bed, write about three good things that happened to you that day. Reflect on those good things by answering the following questions:

- Why did this good thing happen and what does it mean to you?

- What lessons have you learned from reflecting on this good thing?

- How did you or others contribute to this good thing happening?

Gratitude Visit

Gratitude is oriented toward others. Think of a person to whom you would like to express gratitude. Write a letter to them. Try to be specific in describing the way in which their actions have made an important difference in your life. When finished, arrange a visit with that person without explaining the purpose. Try to make it as casual as possible.

When you see them after you settle in, read your letter slowly, with expression and eye contact. And allow the other person to react unhurriedly. Reminisce about the times and specific events that made that person important to you.

- What feelings came up as you wrote your letter?

- What was the easiest part to write and what was the toughest part?

- Describe the other person’s reaction to your expression of gratitude?

- How were you affected by their reaction?

- How long did these feelings last after you presented your letter?

- How often did you recall the experience in the days following?

Homework : Blessings journal is assigned, and client is asked to write about three good things that happened that day before bedtime every night for a week in a way that was introduced during the session.

Suggest that clients socialize with more people who are grateful and observe if that improves their mood. People who are thankful have a language of future, abundance, gifts, and satisfaction.

You can also ask clients to find ways to express gratitude directly to another person. While doing so, ask them to avoid saying just thank you and express gratitude in concrete terms.

Clinician notes : Considerable effort and time to manage the logistics are required to write a letter and arrange a visit. Be sure to provide clients adequate time and support to complete this practice over the course of therapy. You can discuss the timeline, periodically remind them, and even encourage clients to read their Gratitude Letters so they can make changes and rehearse the experience of writing it and reading it out loud.

Be sure clients have the opportunity to share their experiences of the Gratitude Visit.

Session IX – Instilling Hope and Optimism

Goal : One Door Closes, One Door Opens exercise is introduced and the client is encouraged to reflect on three doors that closed and what opportunities for growth it offered.

Tools : One Door Closes, One Door Opens, and Learning Optimism prompts

Rationale : Essentially, hope is the perception that one can reach the desired goals (Snyder, 1994). Hopeful thinking comes down to cultivating the belief that one can find and use pathways to desired goals (Snyder, Rand, & Sigmond, 2002).

Optimism can be learned and can be cultivated by explaining setbacks in a way that steers clear of catastrophizing and helplessness. Optimistic people see bad events as temporary setbacks and explain good events in terms of permanent causes such as traits or abilities.

Optimists also tend to steer away from sweeping universal explanations for events in their lives and don’t allow helplessness to cut across other aspects of their lives (Seligman, 1991).

Painful experiences can be re-narrated as it is the client who gets to say what it all means. Like a writer, a sculptor or a painter the client can re-create his or her life story from a different perspective, allow it to take a different shape and incorporate light into the dark parts of their experience.

- One Door Closes, Another Door Opens

Think of times when you failed to get a job you wanted or when you were rejected by someone you loved. When one door closes, another one almost always opens. Reflect and write about three doors that closed and what opportunities for growth it offered. Use the following questions to help with your reflections:

- What was the impact of doors that closed?

- Did this impact bring something positive to you? What was it?

- What led to a door closing, and what or who helped you to open another door?

- How did you grow from doors that opened?

- If there is room for more growth, what might this growth look like?

Learning Optimism

Think of something that happened recently that negatively impacted your life. Explore your beliefs about the adversity to check for catastrophizing.

- What evidence do you have that your evaluation of the situation is correct?

- What were the contributing causes to the situation?

- What does this mean and what are the potential implications?

- How is the belief about the situation useful to you?

- When a door closes, how do you explain the causes of failure to yourself?

- Regarding your happiness and wellbeing, what were the negatives and positives of this adversity?

- Was the impact of this setback all-encompassing or long-lasting?

- Was it easy or hard for you to see if a door opened, even just a crack?

- What does the closed door represent for you now?

- How did the One Door Closes, Another Door Opens practice enhanced your flexibility and adaptability?

- Do you think that deliberate focus on the brighter side might encourage you to minimize or overlook tough realizations that you need to face?

- Would you still like the door that closed to be opened, or do you not care about it now?

Homework : As a weekly exercise explain and write down your broad outlook on life in one or two sentences and then monitor if daily stressors have an impact on your overall perspective. If so, brainstorm ways to help your perspective remain constant.

Alternatively, to practice hope, ask the client to reflect on one or two people who helped to open the doors or who held the opened doors for them to enter.

And to practice optimism, ask the client to help a friend with a problem by encouraging him or her to look for the positive aspects of the situation.

Clinician notes : The benefits of optimism are not unbounded, but they do free us to achieve the goals we set. Our sense of values or our judgment is not eroded by learning optimism , it is enhanced by it.

Suggest to your clients that if rumination keeps showing up, they consider positive distraction and volunteer the time they normally spend analyzing problems to endeavors that make an impact on the world. Not only will they distract themselves in a positive way but may also gain a much-needed perspective on their problems.

Session X – Resilience

Goal : Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is introduced and practiced through writing therapy.

Tool : Expressive Writing

Rationale : Many patients following trauma develop Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), but many also experience Posttraumatic Growth (PTG). Without minimizing the pain and while respecting clients’ readiness, exploration of the possibility for growth from trauma can help them gain insight into the meaning of life and the importance of relationships.

Research shows that PTG can lead clients to:

- mitigate the feelings of loss or helplessness (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006)

- develop a renewed belief in their abilities to endure and prevail

- achieve improved relationships through discovering who they can really count on

- feel more comfortable with intimacy (Kinsella, Grace, Muldoon, & Fortune, 2015)

- have a greater sense of compassion for others who suffer

- develop greater appreciation for life (Jayawickreme & Blackie, 2014; Roepke, 2015)

- enhanced personal strength and spirituality (Fazio, Rashid, & Hayward, 2008)

Positive reinterpretation, problem-focused coping, and positive religious coping facilitate PTG. Although time itself doesn’t influence PTG as it remains stable over time, intervening events and processes do facilitate growth.

James Pennebaker’s strategy, known as the Writing Therapy, showed that writing about a traumatic or upsetting experience can improve people’s health and wellbeing (Pennebaker, & Evans, 2014).

While assuring complete confidentiality, clients are asked to write for 15 to 30 minutes for three to five consecutive days about one of their most distressing or traumatic life experiences in detail and to fully explore their personal reactions and deepest emotions.

- Expressive Writing

Using a note pad or journal, please write a detailed account of a trauma you experienced. In your writing, try to let go and explore your deepest thoughts and feelings about the traumatic experience in your life. You can tie this experience to other parts of your life, or keep it focused on one specific area.

Continue to write for at least 15 to 20 minutes a day for four consecutive days. Make sure you keep your writings in a safe, secure place that only you have access to. You can write about the same experience on all four days or you can write about different experiences.

At the end of four days, after describing the experience, please write if the experience has helped you with the following:

- understand what the experience means to you.

- understand your ability to handle similar situations.

- understand your relationships in a different light.

- What was the most difficult part of writing?

- Do you agree that even though it may have been difficult, it was still worth writing?

Some reactions to the trauma, adversity, or losses can be so strong that we deliberately avoid associated feelings.

- Did the writing process help you see this avoidance if any?

- Did writing help you to visualize growth in terms of your perspective on life?

- Did you experience healing or growth, despite having the lingering pain of the trauma or loss?

Homework : Ask the client to continue writing for three more consecutive days for 15 to 30 minutes each time. Remind the client to make sure to keep their writings in a safe, secure place that only he or she has access to. They can write about the same experience on all four days or they can write about different experiences.

Clinician notes : To better understand the context in which clients are living, the practitioner should continue discussing therapeutic changes with clients without necessarily asking about growth. It also helps to accept the fact that it may be difficult to pinpoint the start and end that marks when growth from trauma occurs.

Focusing on themes of change may help identify when additional support is needed to amplify PTG while keeping in mind that some clients for reasons outside of their control will not continue to experience long-term growth.

Session XI – Taste for Life

Goal : Tendencies toward busy behavior are assessed and savoring exercise is assigned based on the client’s preference and strategies to safeguard against adaptations are discussed.

Tool : Busy Behavior Assessment and Savoring Techniques

Rationale : According to Carl Honoré (2004), we live in a multitasking era where we have become addicted to speed. Evidence shows that people who are cognitively busy are also more likely to act selfishly, use sexist language, and make erroneous judgment in social situations.

On the other hand, research also shows that when people are in a relaxed state, the brain slips into a deeper, richer, more nuanced mode of thought (Kahneman, 2011). Psychologists actually call this “Slow Thinking,” and one method for achieving this cognitive state it to practice what is known as savoring .

Fred Bryant, a pioneer in savoring, defines it as a mindful process of attending to and appreciating the positive experiences in one’s life (2003). Bryant describes four types of savoring: basking, thanksgiving, marveling, and luxuriating. Research shows that savoring fosters:

- positive emotions

- increases wellbeing

- deepens a connection to the meaningful people in our lives.

Savoring requires effort that involves deliberately working against the pressures to multitask. Learning to savor requires time and becomes more natural the more we practice it.

Kinds of Savoring Experiences:

- Basking is about taking great pleasure or satisfaction in one’s accomplishments, good fortune, and blessings

- Thanksgiving is about expressing gratitude and giving thanks

- Luxuriating is about taking great pleasure and showing no restraint in enjoying physical comforts and sensations

- Marveling is about becoming filled with wonder or astonishment: beauty often induces marveling and exercising virtue may also inspire it

- Mindfulness is a state of being aware, attentive, and observant of oneself, one’s surroundings and other people.

- Busy Behavior Assessment

Reflect on whether or not you find yourself constantly busy and how this manifest in your daily life by answering the following questions:

- Do you multitask or find yourself constantly short on time?

- What are some of the signs of being busy and living life in the fast track: information overload, time crunch, overstimulation, underperforming, anxiety, and multitasking?

- Which ones of these do you experience?

- Reflect on what drives your busy behavior.

- Do you believe that these drivers are internal, external, or a combination of both?

Savoring Techniques

Practice the following strategies to increase savoring. All of the strategies to slow down mentioned here require active engagement. Select one or two of the following Savoring Techniques:

- Sharing With Others: Seek out others to share an experience. Tell them how much you value the moment (this is the single strongest predictor of pleasure.)

- Memory Building: Take mental photographs or even a physical souvenir of an event and reminisce about it later with others.

- Self-praise: Share your achievements with others and be proud. Do so in a way that is authentic and honest in celebrating your persistence in maintaining focus in achieving something meaningful to you.

- Sharpening Perceptions: Focus deliberately on certain elements and block out others. For example, most people spend far more time thinking about how they can correct something that has gone wrong than they do basking in what has gone right.

Brainstorm specific actions you will take to practice one or more of these techniques and think about who will support you or what can inhibit your progress.

Discussion questions : When, where, and how frequently can you use it to increase positive emotions in your daily life?

Homework : Pick a favorite or a different savoring technique and practice it between sessions. Reflect and write your personal list of actions which can sustain and enhance savoring.

Clinician notes : Savoring requires practice and some clients may struggle with savoring practices because they overthink the experience which tends to interfere with their ability to notice and attend to their senses.

The focus of the Savoring practices is positive but if the clients are feeling distressed, see if they are able to put aside their negative thoughts and feelings by using the diversion strategy from Session Five: Open and Closed Memories to optimally benefit from this exercise.

Clients should attend mindfully to all aspects of a savoring experience, including its cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects. However, tuning in too much to feelings or thoughts may backfire and could interfere, eventually dampening the savoring experience so encourage the client to monitor their experiences for adaptation.

Session XII – People Matter

Goal : Seeing best in others and developing strategies for cultivation of positive relationships

Tool : Strength Spotting Exercise

Rationale : Recognizing the strengths of one’s loved ones has been proven to have significant positive benefits on relationships and wellbeing of those who practice it actively.

Understanding one another’s strengths foster a greater appreciation for each person’s intentions and actions and promote empathy. Ultimately, positive relationships buffer us against stress. The central positive psychotherapy (PPT) practice covered in this session is learning to see strengths in others and creating a Tree of Positive Relationships.

- Strengths Spotting

Answer the following questions about people you have close relationships with:

- Who in your immediate or extended relationships always appears to be the most hopeful and optimistic person?

- Who in your relationship circles has the most humorous and playful disposition?

- Who in your relations is the most creative person?

- Who is always cheerful, bubbly, and smiley?

- Who is the most curious person?

- Who always treats others fairly and squarely?

- Who is the most loving person in your family or friends?

- Who among your loved ones loves to create new things?

- Who is a good leader?

- Who in your relations is the most forgiving person?

- Who among your loved ones shows balanced self-regulation?

- What behaviors, actions, or habits does your partner exhibit to denote the strengths you identified?

- Do you share strengths with each other?

- Discuss any you share as well as ones you don’t.

- In what ways do your strengths complement each other?

- Did you also look at your partner’s and your bottom strengths?

- What can you learn from those?

Homework : If practical, ask your family and friends to take the VIA strengths survey. Create a Tree of Positive Relationships to help you and people you are close to gain greater insight into each other’s strengths.

Encourage clients to have uninterrupted, quality conversations with their loved ones at least once per week.

Clinician notes : To maintain progress, suggest that clients brainstorm a way to celebrate each other’s strengths. Suggest they focus on bonding activities that establish communication patterns, routines, and traditions both through daily, casual ways of enjoying each other’s company as well as more elaborate planned celebrations and vacations.

Session XIII – Politics of Wellbeing

Goal : Positive communication is addressed through learning about Active Constructive Responding and client is encouraged to look for opportunities to practice.

Tool : Active Constructive Responding (ACR)

Rationale : Shelly Gable and her colleagues found that sharing and responding positively to good events in our lives increases relationship satisfaction and strengthens our bonds (2004). When we capitalize on positive events in our lives by allowing others to partake in the good news not only do we amplify it, but also increase feelings of being valued and validated.

- Active Constructive Responding (ACR)

Read carefully the following descriptions of different styles of responding to good news. Check off which type of responses you identify with most of the time.

- When I share good news, my partner responds enthusiastically.

- Sometimes my partner is more excited about my wins than I am.

- My partner shows a genuine interest and asks a lot of questions when I talk about good events.

- My partner is happy for me but does not make a big deal out of my sharing positive news.

- When good things happen to me, my partner is silently supportive.

- Although my partner says little, I know she is happy for me.

- Often when I share good news, my partner finds a problem with it.

- My partner often sees a downside to the good events.

- My partner is often quick to point out the downside of good things.

- I’m not sure my partner often cares much.

- I often feel my partner doesn’t pay attention to me.

- My partner often seems uninterested.

Now let us try ACR in session. We will take turns sharing good news and then allowing the other person to respond. Think of something positive and recent that happened to you and tell me about it.

- What can you learn about yourself from identifying your response style?

- Are there any barriers that hinder you in engaging in ACR? They can be subjective or objective such as your personality style, preferences, and family of origin, culture, beliefs, or interpersonal dynamics.

- Should you already engage in some sort of ACR, what can you do to take it to a higher level?

- If you find that ACR doesn’t come naturally to you, what small steps can you take to adopt some aspects of this practice that are consistent with your disposition?

- Identify individuals or situations that display all four responding styles.

- What effects do you notice of each style both on sharer and responder?

Homework : Ask the client to practice ACR beyond his intimate relationships and use it with family member and friends.

Clinician notes : If the client is proficient in ACR, consider expanding the practice of positive communication into positive affirmations where partners offer each other words and actions that confirm the partners’ beliefs about themselves and behave in ways that are congruent with their partner’s ideal self (Drigotas, 2002).

Ask the client to practice perceptual affirmations where partners’ general view of each other is aligned with their ideal self, where we perceive our partners as trying their best, where we are forgiving of shortcoming and sympathize with the pain of failure, and finally, where we shine the light on qualities.

Ask the client to also practice behavioral affirmations where partners elicit behaviors that are in congruence with the other person’s ideal selves as well as create opportunities for expression of those ideal selves while decreasing situations that can negate them and behaviors that conflict.

This paves the way toward movement in the direction of being the most valuable self through skill development and reflection on aspirations congruent with deeply help hopes and dreams.

Session XIV – Gift of Time

Goal : Therapeutic benefits of helping others are introduced and the client is encouraged to Give the Gift of Time in a way that employs their strengths.

Tool : Gift of Time

Rationale : Helping others and practicing altruistic behavior has been shown to significantly increase a sense of meaning and purpose in life. In addition to making a difference, we also benefit from shifting our focus away from ourselves and indulging in our own thoughts (Keltner, 2009).

Research shows that material gifts lose their charm and value over time, but positive experiences and interactions continue to pay dividends through increased confidence that you can, in fact, do good (Kasser & Kanner, 2004).

- Gift of Time

Think of ways in which you could give someone you care about a Gift of Time. Brainstorm ways of doing something that requires a fair amount of time and involves using your strengths. Using your strengths to deliver the gift will make the exercise more satisfying.

- If creativity is your strength, write an anniversary note or make a gift by hand.

- If kindness sets you apart, prepare a dinner or run errands for a sick friend.

- If your humor is your strength, find a way to cheer someone up.

Write about your experience, recalling the details of what was involved in planning and reflect on how it made you feel.

- What feeling came up as you were giving your gift?

- How did you feel after giving your gift?

- What was the reaction of the recipient of your gift?

- What were the positive or negative consequences resulting from giving your gift?

- Did you use one or more of your signature strengths? If so, which one?

- Have you undertaken such an activity in the past? What was it?

- Did you find that it was different this time around? If so, what differences did you notice?

- Have there been times in the past when you were asked to give the Gift of Time and you didn’t want to?

- Have you been a recipient of someone else’s Gift of Time? What was it?

- Are you willing to give the Gift of Time regularly for a particular cause? What cause might this be?

- Do you anticipate any adaptation, and do you think the Gift of Time might not provide as much satisfaction as it did the first time?

- If so, what steps can you take to address this?

Homework : To maintain progress, suggest that the client performs a few random acts of kindness or consider volunteering for a cause they care about in a way that would allow them to use their strengths.

Clinician Note : Exercise caution if the self-care of clients is already compromised and make sure that their altruistic endeavors don’t negatively impact their self-care needs. To help clients decide on the scale of their altruistic endeavors, explore carefully client’s level of distress and wellbeing as it may reveal their exposure to a potential vulnerability.

Session XV – A Life Worth Living

Goal : The concept of a full life is explained as an integration of enjoyment, engagement and meaning and ways of sustaining positive change in the future are devised.

Tools : From Your Past Toward Your Future and Positive Legacy

Rationale : Cultivation of meaning helps us articulate our life goals in a way that integrates our past, present, and future. It provides a sense of efficacy, helps create ways to justify our actions and connects us to other people through a shared sense of purpose.

Cultivating long term life-satisfaction is closely tied to meaningful pursuits and our lives provide opportunities for meaningful stretches if one is willing to look.

In this final session, we combine the positive introduction with a better version of the self, and the hope of leaving a positive legacy.

- From Your Past Toward Your Future

If available, please read your Positive Introduction from Session I. If not, simply recall your story of resilience from our first session. Answer the following questions:

- From the experience of resilience in your Positive Introduction story, what meaning do you derive today? ____

- Which character strengths are most prominent in your story now that you have explored them further? _____

- Do you still use these strengths in everyday life? If so, how? ______

- What does your story of resilience tell you about your life’s purpose? ____

- What creative or significant achievements would you like to pursue in the next 10 years? ____

- If you were to pick one, what makes it most important for you and why? ____

- In what way will this goal make a difference for others? ____

- What steps do you need to take over the next 10 years to accomplish it? Describe what you need to do year by year? ______

- Which of your signature strengths will you use in accomplishing this goal? ____

Positive Legacy

Envision your life as you would like it to be and how you would want to be remembered by others. What accomplishments and strengths would they mention? What would you like your legacy to be? Describe in concrete terms. _____

Now look back at what you wrote and ask yourself if you have a plan that is both realistic and within your ability to do so.

- What was like it to re-read your story of resilience again?

- Would you write it the same way today? If not, what would you change?

- How has your thinking about the purpose and meaning of life changed over the course of our sessions?

- What was the process like for you of reflecting on and then writing about your goals for the future?

- What will your life look like when you accomplish your goals?

- What might happen if you do not accomplish your goals?

- Think of ways you can use your signature strengths to do something that would enable you to leave a Positive Legacy.

- What specific actions would you take to accomplish your short and long-term goals? What is the timeline for completion of these actions?

Homework : Resolve to keep this in a safe place and read it again a year from now. At that point ask yourself if you made progress, if you need to revise your goals, or if new goals have emerged for you.

Clinician notes : Some client may struggle to find purpose and meaning in their life, especially if they are struggling with a significant loss, trauma or severe depression. Nevertheless, it is very important for the client to be asked about meaning. Irvin Yalom (2020), the author of Existential Psychotherapy states that every one of his clients expressed concerns about the lack of meaning in their lives.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We hope that you found this overview of effective positive psychotherapy tools to be helpful.

What has your experience been using these positive psychotherapy exercises? Leave a comment below. We would love to hear and learn from you.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & Minhas, G. (2011). A dynamic approach to psychological strength development and intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology , 6 (2), 106-118.

- Bryant, F. (2003). Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. Journal of Mental Health , 12 (2), 175-196.

- Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2006). The foundations of posttraumatic growth: An expanded framework. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth (pp. 1-23). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Chowdhury, T. G., Ratneshwar, S., & Mohanty, P. (2009). The time-harried shopper: Exploring the differences between maximizers and satisficers. Marketing Letters , 20 (2), 155-167.

- Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., … & Worthington Jr, E. L. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 63 (1), 20-31.

- Denborough, D. (2014). Retelling the stories of our lives: Everyday narrative therapy to draw inspiration and transform experience . New York, NY: Norton.

- Drigotas, S. M. (2002). The Michelangelo phenomenon and personal well‐being. Journal of Personality , 70 (1), 59-77.

- Drigotas, S. M., Rusbult, C. E., Wieselquist, J., & Whitton, S. W. (1999). Close partner as sculptor of the ideal self: Behavioral affirmation and the Michelangelo phenomenon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 77 (2), 293-323.

- Emmons, R. A. (2007). Thanks! How the new science of gratitude can make you happier . New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Fazio, R. J., Rashid, T., & Hayward, H. (2008). Growth through loss and adversity: A choice worth making. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Positive psychology: Exploring the best in people, Vol. 3. Growing in the face of adversity (pp. 1–27). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Malcolm, W. (2002). Resolving unfinished business: Relating process to outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 70 (2), 406-416.

- Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review , 94 (3), 319-340.

- Honoré, C. (2004). In praise of slow: How a worldwide movement is challenging the cult of speed . London, UK: Orion.

- Jayawickreme, E., & Blackie, L. E. (2014). Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Evidence, controversies and future directions. European Journal of Personality , 28 (4), 312-331.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Kasser, T., & Kanner, A. D. (Eds.). (2004). Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Keltner, D. (2009). Born to be good: The science of a meaningful life . New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Kinsella, E. L., Grace, J. J., Muldoon, O. T., & Fortune, D. G. (2015). Post-traumatic growth following acquired brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology , 6.

- Kumashiro, M., Rusbult, C. E., Finkenauer, C., & Stocker, S. L. (2007). To think or to do: The impact of assessment and locomotion orientation on the Michelangelo phenomenon. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships , 24 (4), 591-611.

- Linley, P. A., Nielsen, K. M., Gillett, R., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). Using signature strengths in pursuit of goals: Effects on goal progress, need satisfaction, and well-being, and implications for coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review , 5 (1), 6-15.

- Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41 (9), 954-969.

- Marsh, J. (2011, November 17). Tips for keeping a gratitude journal. Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/tips_for_keeping_a_gratitude_journal

- Pennebaker, J. W., & Evans, J. F. (2014). Expressive writing: Words that heal: Using expressive writing to overcome traumas and emotional upheavals, resolve issues, improve health, and build resilience . Enumclaw, WA: Idyll Arbor.

- Roepke, A. M. (2015). Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 83 (1), 129-142.

- Ruch, W., Proyer, R. T., Harzer, C., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2010). Values in action inventory of strengths (VIA-IS). Journal of Individual Differences, 31 (3), 138-149.

- Rusbult, C. E., Kumashiro, M., Kubacka, K. E., & Finkel, E. J. (2009). “The part of me that you bring out”: Ideal similarity and the Michelangelo phenomenon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96 (1), 61-82.

- Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice: Why more is less. New York, NY: Harper‐Collins.

- Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 83 (5), 1178-1197.

- Seligman, M. E. (1991). Learned optimism . New York, NY: AA Knopf.

- Seligman, M. E., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist , 61 (8), 774-788.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology , 1 (2), 73-82.

- Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope . New York, NY: Free Press.

- Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., & Sigmond, D. R. (2005). Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 257-276). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Worthington Jr, E. L. (2006). Just forgiving: How the psychology and theology of forgiveness and justice inter-relate. Journal of Psychology & Christianity , 25 (2), 155-168.

- Worthington Jr, E. L. (n.d.). REACH forgiveness of others. Retrieved from http://www.evworthington-forgiveness.com/reach-forgiveness-of-others

- Yalom, I. D. (2020). Existential psychotherapy . New York, NY: Hachette.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

I am very happy to see this post because it really a nice post. Thanks

This article is very informative and comprehensive. It has broadened my knowledge and perspective on Positive Psychotherapy. The exercises can benefit my clients as well as myself in the pursuit of happiness.

This is indeed one of the most rarely well thought and designed positive therapy/ coaching exercises which I am certain that will have a good impact on the client. Millions of thanks

This article has made me more effective in my work and I thank you dearly!

you are a genius!!!!!!

Beautifully executed. Focused on the positive. Clients would feel enthused to pursue it. A positive psychology CBT.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Empty Chair Technique: How It Can Help Your Clients

Resolving ‘unfinished business’ is often an essential part of counseling. If left unresolved, it can contribute to depression, anxiety, and mental ill-health while damaging existing [...]

29 Best Group Therapy Activities for Supporting Adults

As humans, we are social creatures with personal histories based on the various groups that make up our lives. Childhood begins with a family of [...]

47 Free Therapy Resources to Help Kick-Start Your New Practice

Setting up a private practice in psychotherapy brings several challenges, including a considerable investment of time and money. You can reduce risks early on by [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (42)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (63)

The Counseling Palette

Mental health activities to help you and your clients thrive, 1. purchase 2. download 3. print or share with clients.

- Nov 27, 2021

11 New Therapy Worksheets for Anxiety, PTSD, and More

Updated: Sep 5, 2023

Download worksheets on CBT, anxiety, PTSD, self-care and more

T herapy worksheets can make all the difference. While it’s great to talk through new concepts, having a physical tool to share or send home can reinforce all the work done in sessions.

Fortunately, PDF worksheets can work just as well for telehealth as in-person therapy. You can print them out, or share them electronically on-screen or via e-mail.

Here’s a little about how these worksheets were developed, along with descriptions of each.

Article Highlights Background

CBT Triangle

Anxiety Plan

Understanding PTSD

Strong Emotions

Challenging Thoughts

Reframing trauma thoughts, anxiety hierarchy.

Trauma Narrative Making Meaning

Grounding Stones

Using These Tools

I developed each of the worksheets below based on my CBT and PTSD training, as well as my real-life experience in the field.

I find many of the mental health worksheets online cover key concepts, but they aren’t always user-friendly.

For example, a “cognitive distortion,” really just refers to an unhelpful thought. “Exposure,” means facing a fear that’s making your life difficult.

(And sometimes all those charts in traditional worksheets just make me dizzy.)

My worksheets and tools generally try to avoid this kind of psychological jargon, especially in the prompts and descriptions for clients. (I do sometimes keep these tech terms in the titles, mainly so that therapists recognize them at a glance.)

While we teachers and counselors like terms like “evidence-based,” many clients simply want to know what these skills mean for their lives, and how they can feel a little better.

They don't necessarily need to know any of the psychology terms to overcome specific symptoms or problems.

With that in mind, here are the worksheets I’ve developed based on concepts like anxiety management, mindfulness, grounding, PTSD treatment, exposure , and self-care.

To get started, my CBT triangle worksheet is available here for free . You can get the rest of these in a bundle at a nominal price. (Use coupon code 1110 for 10% off any of the worksheet kits and downloads.)

If you’re struggling with cost, send me a message and I’ll keep you updated when I run deals or promotions in the future.

Now, let’s get into some therapy worksheets !

CBT Triangle Worksheet

The cognitive behavioral triangle, or CBT triangle , is a quick and easy tool to teach the idea of changing our thoughts.

While feelings are natural, and many thoughts are automatic, we can change negative patterns over time.

For example, if someone tends to beat themselves up anytime they struggle at work, there may be a pattern in place.

They may believe their colleagues or boss don’t like them. This could lead to them feeling anxious or discouraged.

This discouragement could then make it harder to work, repeating the cycle.

With the CBT triangle, you can chart these patterns. The thought, “I’m bad at this job,” connects to the feeling, “discouragement, fear,” which leads to the behavior (taking more time on projects).

This then reinforces the original thought of, “I’m bad at this job,” and the triangle goes round and round.

The most basic step in CBT is to practice changing that original thought.