- DEREE - The American College of Greece (ACG)

- John S. Bailey Library

Google Scholar Guide

- Advanced searching

Google Scholar provides several advanced searching options. These options may include the use of:

- the Advanced search features.

- Boolean and proximity operators.

- words as search operators.

- symbols as search operators.

The Advanced search features

Click the hamburger icon ( ) on the left-hand corner. This reveals a menu from which you could choose the Advanced search .

Once you select the Advanced search , a pop-up window with the available advanced search options appears.

You may use the following options:

- Find articles with all of the terms: Default search option. | Combines search terms. | Retrieves articles that include all search terms. | Narrows down search results.

- Find articles with the exact phrase: Retrieves articles which include the search terms when they appear together, as an exact phrase. | Narrows down search results.

- Find articles with at least one of the words: Retrieves articles which include either or all search terms. | Expands search results.

- Find articles without the words: Excludes search terms. | Narrows down search results.

You can specify where the words you are searching may appear, by using any of the following options:

- anywhere in the article: Default search option. | Returns articles which include the search terms in any part of the article; title or body. | Works in conjunction with any of the "Find articles" options.

- in the title of the article: Returns articles which include the search terms only in the title of the article. | Works in conjunction with any of the "Find articles" options.

There are three additional search options to use:

- Return articles authored by: Returns articles written by a particular author | Works in conjunction with any of the "Find articles" or "Return articles" options. | Narrows down search results.

- Return articles published in: Returns articles published in a particular periodical publication. | Works in conjunction with any of the "Find articles" or "Return articles" options. | Narrows down search results.

- Return articles dated between: Returns articles published in a particular date range. | Works in conjunction with any of the "Find articles" or "Return articles" options. | Narrows down search results.

Boolean operators

This type of search uses operators that help you narrow or broaden your search. The most common operators are AND , OR , NOT . Check the table below to see when and how to use them in Google Scholar.

Words as search operators

Google Scholar supports the use of words as search operators. These words are:

- intitle : Results include a specific search term in the title of the article.| Syntax: intitle:search term Tip! Do not add a space after the colon.

- intext : Results include a specific search term in the body of the article.| Syntax: intext:search term Tip! Do not add a space after the colon.

- author : Results include articles written by a specific author.| Syntax: author:"first name last name" Tip! Do not add a space after the colon. Place quotation marks around the author's name.

- source : Results include articles published in a particular journal.| Syntax: source:"journal title" Tip! Do not add a space after the colon. Place quotation marks around the journal title.

- ininventor : Results include patent related documents including the name of a patent inventor. Syntax: ininventor:"first name last name" Tip! Do not add a space after the colon. Place quotation marks around the inventor's name.

- assignee : Results include patent related documents including the entity that is granted the ownership of the patent.| Syntax: assignee:"entity name" Tip! Do not add a space after the colon. Place quotation marks around the entity name.

Symbols as search operators

Google Scholar supports the use of symbols as search operators. These symbols are:

- Quotation marks ( " " ): Results include the search terms when they appear as a phrase. Syntax: "search term A search term B"

- Hyphen ( - ): You can use the hyphen to indicate that words are strongly connected. Syntax: search term A-search term B | Tip! Do not add spaces before and after the hyphen.

- Hyphen ( - ): You can use the hyphen to exclude words from a search query. Syntax: search term A -search term B | Tip! Add a space after the first search terms, but do not add a space between the hyphen and the search term you want to exclude.

- << Previous: Basic searching

- Next: Saving results >>

- Library links setup

- Open access articles

- Basic searching

- Saving results

- Citing results

- Evaluating results

- Creating alerts

- Author profiles

- Last updated: Dec 21, 2022 1:37 PM

18 Google Scholar tips all students should know

Dec 13, 2022

[[read-time]] min read

Think of this guide as your personal research assistant.

“It’s hard to pick your favorite kid,” Anurag Acharya says when I ask him to talk about a favorite Google Scholar feature he’s worked on. “I work on product, engineering, operations, partnerships,” he says. He’s been doing it for 18 years, which as of this month, happens to be how long Google Scholar has been around.

Google Scholar is also one of Google’s longest-running services. The comprehensive database of research papers, legal cases and other scholarly publications was the fourth Search service Google launched, Anurag says. In honor of this very important tool’s 18th anniversary, I asked Anurag to share 18 things you can do in Google Scholar that you might have missed.

1. Copy article citations in the style of your choice.

With a simple click of the cite button (which sits below an article entry), Google Scholar will give you a ready-to-use citation for the article in five styles, including APA, MLA and Chicago. You can select and copy the one you prefer.

2. Dig deeper with related searches.

Google Scholar’s related searches can help you pinpoint your research; you’ll see them show up on a page in between article results. Anurag describes it like this: You start with a big topic — like “cancer” — and follow up with a related search like “lung cancer” or “colon cancer” to explore specific kinds of cancer.

Related searches can help you find what you’re looking for.

3. And don’t miss the related articles.

This is another great way to find more papers similar to one you found helpful — you can find this link right below an entry.

4. Read the papers you find.

Scholarly articles have long been available only by subscription. To keep you from having to log in every time you see a paper you’re interested in, Scholar works with libraries and publishers worldwide to integrate their subscriptions directly into its search results. Look for a link marked [PDF] or [HTML]. This also includes preprints and other free-to-read versions of papers.

5. Access Google Scholar tools from anywhere on the web with the Scholar Button browser extension.

The Scholar Button browser extension is sort of like a mini version of Scholar that can move around the web with you. If you’re searching for something, hitting the extension icon will show you studies about that topic, and if you’re reading a study, you can hit that same button to find a version you read, create a citation or to save it to your Scholar library.

Install the Scholar Button Chrome browser extension to access Google Scholar from anywhere on the web.

6. Learn more about authors through Scholar profiles.

There are many times when you’ll want to know more about the researchers behind the ideas you’re looking into. You can do this by clicking on an author’s name when it’s hyperlinked in a search result. You’ll find all of their work as well as co-authors, articles they’re cited in and so on. You can also follow authors from their Scholar profile to get email updates about their work, or about when and where their work is cited.

7. Easily find topic experts.

One last thing about author profiles: If there are topics listed below an author’s name on their profile, you can click on these areas of expertise and you’ll see a page of more authors who are researching and publishing on these topics, too.

8. Search for court opinions with the “Case law” button.

Scholar is the largest free database of U.S. court opinions. When you search for something using Google Scholar, you can select the “Case law” button below the search box to see legal cases your keywords are referenced in. You can read the opinions and a summary of what they established.

9. See how those court opinions have been cited.

If you want to better understand the impact of a particular piece of case law, you can select “How Cited,” which is below an entry, to see how and where the document has been cited. For example, here is the How Cited page for Marbury v. Madison , a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling that established that courts can strike down unconstitutional laws or statutes.

10. Understand how a legal opinion depends on another.

When you’re looking at how case laws are cited within Google Scholar, click on “Cited by” and check out the horizontal bars next to the different results. They indicate how relevant the cited opinion is in the court decision it’s cited within. You will see zero, one, two or three bars before each result. Those bars indicate the extent to which the new opinion depends on and refers to the cited case.

In the Cited by page for New York Times Company v. Sullivan, court cases with three bars next to their name heavily reference the original case. One bar indicates less reliance.

11. Sign up for Google Scholar alerts.

Want to stay up to date on a specific topic? Create an alert for a Google Scholar search for your topics and you’ll get email updates similar to Google Search alerts. Another way to keep up with research in your area is to follow new articles by leading researchers. Go to their profiles and click “Follow.” If you’re a junior grad student, you may consider following articles related to your advisor’s research topics, for instance.

12. Save interesting articles to your library.

It’s easy to go down fascinating rabbit hole after rabbit hole in Google Scholar. Don’t lose track of your research and use the save option that pops up under search results so articles will be in your library for later reading.

13. Keep your library organized with labels.

Labels aren’t only for Gmail! You can create labels within your Google Scholar library so you can keep your research organized. Click on “My library,” and then the “Manage labels…” option to create a new label.

14. If you’re a researcher, share your research with all your colleagues.

Many research funding agencies around the world now mandate that funded articles should become publicly free to read within a year of publication — or sooner. Scholar profiles list such articles to help researchers keep track of them and open up access to ones that are still locked down. That means you can immediately see what is currently available from researchers you’re interested in and how many of their papers will soon be publicly free to read.

15. Look through Scholar’s annual top publications and papers.

Every year, Google Scholar releases the top publications based on the most-cited papers. That list (available in 11 languages) will also take you to each publication’s top papers — this takes into account the “h index,” which measures how much impact an article has had. It’s an excellent place to start a research journey as well as get an idea about the ideas and discoveries researchers are currently focused on.

16. Get even more specific with Advanced Search.

Click on the hamburger icon on the upper left-hand corner and select Advanced Search to fine-tune your queries. For example, articles with exact words or a particular phrase in the title or articles from a particular journal and so on.

17. Find extra help on Google Scholar’s help page.

It might sound obvious, but there’s a wealth of useful information to be found here — like how often the database is updated, tips on formatting searches and how you can use your library subscriptions when you’re off-campus (looking at you, college students!). Oh, and you’ll even learn the origin of that quote on Google Scholar’s home page.

18. Keep up with Google Scholar news.

Don’t forget to check out the Google Scholar blog for updates on new features and tips for using this tool even better.

Related stories

Quiz: Do you know solar eclipse Search Trends?

4 ways to use Search to check facts, images and sources online

Get more personalized shopping options with these Google tools

6 ways to travel smarter this summer using Google tools

Empowering your team to build best-in-class mmms.

New ways we’re tackling spammy, low-quality content on Search

Let’s stay in touch. Get the latest news from Google in your inbox.

How to use Google Scholar

Read these tips to improve your searching with Google Scholar, and to find out when it is useful for you to search with Google Scholar - and when you'd better use another tool or database.

Google Scholar: pros and cons

Google Scholar is a very powerful search engine for scientific literature that is used by many researchers and students. It is especially useful to find and access publications that you already know, or to do a quick search on a topic.

Google Scholar is less useful when you want to get an overview of literature on a certain topic, e.g., for your thesis or literature review. This is because Google Scholar offers limited options to combine multiple search terms with Boolean operators (like AND, OR, NOT). By default, Google Scholar searches in the full text of publications. Advanced searching allows you to limit your search to specific fields (title, author, a particular journal and date), but you can’t limit your search to e.g. title, abstract and keywords fields only (as in Scopus).

The selection that Google Scholar makes for you is not transparent. It ranks the search results and shows only the first 1,000 results of any search, based on algorithms that Google changes frequently. The ranking depends on settings that you may be unaware of, such as your language settings or location.

To get an overview of scientific literature on a certain topic, therefore, it’s better to use a bibliographic database. Find out here how to choose the best databases for your subject.

Getting access to publications

If you use Google Scholar from the WUR Library website , you automatically get access to the sources that are part of the WUR collections, if you are on campus.

When you work from the Google Scholar website , make sure that it makes a link to WUR Library to give you easy access to the licensed sources. If you don’t see a ‘Get It from WUR’ link next to your search results, go to Settings in the menu on the top of the page. Here, choose Library links and add Wageningen University & Research Library to the list.

For more information about access to licensed sources off-campus, go to How to access licensed sources directly .

Tips to improve your searching

Note that most of these tips also work in Google!

- Use the Advanced search option (in the menu) to search in specific ‘fields’ or to limit results by year range. These options won’t work optimally (see above), but it can help to limit the number of results.

- Use double quotation marks to search for multiple words next to each other in the specified order (like in compound terms or an exact phrase), e.g., “climate change” or “the impact of climate change on food security”. Otherwise, Google (Scholar) automatically combines multiple words with the operator AND.

- Include alternative terms by using the OR operator. In some cases Google (Scholar) doesn’t include obvious synonyms in your search. With the OR operator you can combine these terms and find more. Instead of OR you can also use | (a pipe), e.g., “heart|myocardial infarction|attack” finds heart infarction, myocardial infarction, heart attack and myocardial attack.

- Exclude specific terms by using the – operator. You can exclude as many terms as you want, e.g., mercury –ford –freddy –outboards –planet.

- Allintitle : Limit your search to terms appearing in the title only, e.g., allintitle:”agaricus bisporus”.

- Filetype : Limit your search to specific file types by using filetype: or ext: E.g., “agaricus bisporus” filetype:pdf

- Site : Limit your search to certain websites or domains. This can be useful for websites without good search options, e.g., “plant diseases” site:journals.plos.org. By searching within certain domain extensions, you can limit your search by country or type of institution, e.g., “plant diseases” site:.edu (academic institutions in the USA).

- Combine all of the above to do more precise searches, e.g., allintitle:“carbon dioxide” OR CO2 -phosphorus ext:pdf site:.edu

- Personalise your searching via Settings and use other handy features of Google Scholar. For example, make your own library of references (called My Library), create literature alerts, or let Google Scholar show import citation links to EndNote or another reference manager. To use these options, you’ll need to sign in with your Google account.

Remember also that there are more Google search engines for specific source types, such as Google Books and Google Patents .

For more tips and information, go to About Google Scholar .

How to Use Google Scholar for Research: A Complete Guide

To remain competitive, Research and Development (R&D) teams must utilize all of the resources available to them. Google Scholar can be a powerful asset for R&D professionals who are looking to quickly find relevant sources related to their project. With its sophisticated search engine capabilities, advanced filtering options, and alert notifications, using Google Scholar for research allows teams to easily locate reliable information in an efficient manner. Want to learn how to use google scholar for research? This blog post will cover how to use google scholar for research, how R&D professionals can exploit the potential of Google Scholar to uncover novel discoveries related to their projects, as well as remain apprised of advancements in their area.

Table of Contents

What is Google Scholar?

Overview of google scholar, searching with google scholar, finding relevant sources with google scholar, exploring related topics, evaluating sources found on google scholar, staying up to date with google scholar alerts, faqs in relation to how to use google scholar for research, how do i use google scholar for research, can you use google scholar for research papers, why is it important to use google scholar for research, are google scholar articles credible.

Google Scholar is a powerful research platform that enables users to quickly find, access, and evaluate scholarly information. It provides easy access to academic literature from all disciplines, including books, journal articles, conference papers, and more. Google Scholar offers researchers a wide range of tools for searching the web for the relevant content as well as ways to keep up with new developments in their field.

Google Scholar i s an online search engine designed specifically for finding scholarly literature on the internet. Google Scholar provides access to a vast array of scholarly literature from renowned universities and publishers around the world, simplifying the process of locating relevant material on any subject. In addition to its comprehensive indexing capabilities, Google Scholar also includes advanced search features such as citation tracking and alert notifications when new results are published in your chosen areas of interest.

The platform makes it a breeze for users to traverse multiple facets of a given topic by providing them with an array of different filters they can apply when conducting searches – these include things such as author name or publication date range; language; type (e.g., book chapter vs journal article); source material (e.g., open access only); etc Moreover, many results found through this platform come equipped with full-text PDFs available for download – so you don’t have to worry about pesky paywalls blocking your path while doing research.

Google Scholar is an invaluable resource for research and development teams, offering quick access to a wealth of scholarly information. Utilizing the proper search approaches, you can quickly locate precisely what you need by employing Google Scholar. Let’s look now at how to refine your results with advanced search techniques.

Key Takeaway: Google Scholar is a powerful research platform that gives researchers an array of tools to quickly locate, access and evaluate scholarly information. It provides users with advanced search features such as citation tracking and alert notifications, along with easy-to-apply filters for narrowing down results by author name or publication date range – making it the go-to tool for any researcher looking to cut through the noise.

Exploring with Google Scholar can be a useful approach to quickly locate applicable scholarly material. There are several different strategies that can be used to get the most out of this powerful tool.

Basic google scholar search strategies involve entering a few keywords or phrases into the search bar and then refining your results using filters, sorting options, and related topics. This method is ideal for those who require a rapid search of information without needing to expend an excessive amount of time researching exact terms, especially for those unfamiliar with searching databases such as Google Scholar. It’s also useful for those who don’t have a lot of experience in searching databases like Google Scholar.

Advanced search strategies allow users to take advantage of more sophisticated features such as Boolean operators , wildcards, and phrase searches. These tools make it easier to narrow down results by specifying exactly what you’re looking for or excluding irrelevant sources from your search results. Advanced searchers should also pay attention to synonyms when crafting their queries since these can help broaden the scope of their searches while still providing relevant results.

Finally, refining your results is key in order to ensure that you only see sources that are truly relevant and authoritative on the topic at hand. Filters such as date range, publication type, language, author name, etc., can help refine your query so that only high-quality sources appear in your list of results. Sorting options provide users with the ability to prioritize documents, enabling them to quickly locate relevant materials without needing to review a large number of irrelevant ones.

Utilizing Google Scholar can be advantageous for swiftly finding pertinent research materials, but it is essential to comprehend the search strategies and filters at hand in order to maximize your searches. By understanding how to identify keywords and phrases, explore related topics, and utilize sorting options and filters, you can ensure that you are finding all of the relevant sources for your research project.

Key Takeaway: Google Scholar is a great tool for quickly locating relevant research sources. Advanced searchers can make use of Boolean operators, wildcards and phrase searches to narrow down their results while basic search strategies such as entering keywords into the search bar work just fine too. Additionally, refining your results with filters and sorting options helps ensure that you only see high-quality sources related to your topic at hand.

Locating applicable materials via Google Scholar can be a challenging endeavor, particularly for those unfamiliar with the research process. To facilitate the research process, employing various strategies can expedite and refine the search for relevant sources through Google Scholar.

Making use of keywords and phrases is a powerful method for finding pertinent sources on Google Scholar. It is important to identify key terms related to your topic or research question so you can narrow down the results. Additionally, using quotation marks around multiple words will allow you to get more precise results as it searches for exact matches instead of individual words within a phrase.

Exploring related topics helps provide additional context when researching on Google Scholar. This includes looking at previous studies conducted on similar topics or areas of interest, which provides further insight into potential sources available from other researchers’ work in the field. Utilizing tools such as co-citation analysis also allows users to explore how different authors have been cited together over time by providing visualizations based on their connections and relationships with each other through citations.

Utilizing filters and sorting options such as language, date range, publication type, etc., enables users to refine their search even further so they only receive results that match their specific criteria. Sorting options like relevance ranking or date published also make it easier for them to find what they need without having to sift through hundreds of irrelevant documents manually. By utilizing these features effectively, researchers can save valuable time when searching for relevant sources in Google Scholar since all the information they need will already be organized accordingly right away, saving them an hour’s worth of manual labor.

By utilizing Google Scholar, research teams can quickly and easily find relevant sources for their projects. With the next heading, we will explore how to evaluate these sources for credibility and authority.

Key Takeaway: Utilizing the right keywords and phrases, exploring related topics, and utilizing filters are essential techniques for finding relevant sources quickly with Google Scholar. By taking advantage of the available features, you can swiftly and accurately pinpoint documents that meet your criteria.

To assess the reliability and authority of each source, consider factors such as the publication’s reputation, author credentials in the field, and when it was published. To do this, look for publications from reputable journals or authors with credentials in the field. Furthermore, consider when the source was issued – more modern pieces may be more pertinent and exact than older ones.

It is advantageous to be aware of the distinct kinds of publications that can appear in search results, such as scholarly articles, books, conference papers, and dissertations; each offering various degrees of precision and accuracy depending on their intent and target audience.

For example, a book chapter may provide an overview of a topic while a peer-reviewed journal article will contain more detailed information backed up by research evidence. Similarly, conference papers are typically shorter summaries of research projects whereas dissertations offer comprehensive coverage including methodology and analysis results. Understanding these differences helps you identify which sources are most suitable for your needs when conducting research using Google Scholar.

Evaluating sources found on Google Scholar is an important step to ensure the credibility and accuracy of research results. By setting up alerts with Google Scholar, you can stay informed about new research findings and manage your subscriptions accordingly.

Maximize your research efforts with Google Scholar. Assess credibility & authority, pay attention to the date of publication & understand different types of publications. #ResearchTips #GoogleScholar Click to Tweet

Google Scholar is an invaluable tool for staying up to date with the latest research in your field. With its alert feature, you can easily set up notifications so that you’re always on top of new developments. Setting up alerts and managing them effectively will help ensure that you never miss a beat when it comes to relevant information.

Begin your research by utilizing Google Scholar’s sophisticated search features such as keyword and phrase searches, sorting results according to relevance or date of publication, and excluding unrelated sources. Once you’ve identified the most pertinent topics related to your research interests, set up alerts for each one by clicking on the bell icon in the upper right corner of the page. This will allow Google Scholar to send notifications whenever new content is published about those specific topics.

When setting up alerts in Google Scholar, make sure that they are tailored specifically toward what matters most to you – this could include certain authors or journals whose work has particular relevance to your own research projects. You can also adjust how often these alerts are sent (daily or weekly) depending on how frequently new material is being published within those fields of study. Additionally, if there are any other sources outside of Google Scholar which may contain useful information (such as blogs), consider adding their RSS feeds into your alert system too so that all relevant updates appear in one place.

Finally, don’t forget to manage existing alerts regularly; this means keeping track of which ones are still relevant and deleting any no longer needed from time to time (this helps keep clutter down). Additionally, try experimenting with different combinations/filters within each alert until you find what works best for keeping yourself informed without getting overwhelmed with notifications.

Key Takeaway: Utilize Google Scholar to stay up-to-date on the latest research in your field – create tailored alerts for specific topics and authors, adjust frequency of notifications as needed, and manage existing alerts regularly. Stay ahead of the curve by gathering all pertinent news in one location.

Google Scholar is a great tool for conducting research. It provides access to millions of scholarly articles, books, and other sources from across the web. Google scholar works by entering keywords related to your topic into the search bar at the top of the page to quickly locate relevant scholarly articles, books, and other sources from across the web. Then narrow down your results using filters such as date range or publication type.

Finally, skim through the abstracts and full texts to pinpoint useful information for your research project.

Yes, Google Scholar is a great resource for research papers. It offers access to an extensive range of scholarly literature from journals, books, and conference proceedings. The search engine provides a convenient way to locate the most recent research in any area by entering keywords or phrases.

Advanced capabilities, such as citation monitoring, can be utilized to track the latest citations of one’s own or others’ work.

Google Scholar is an invaluable tool for research, as it provides access to a vast range of scholarly literature from around the world. It allows researchers to quickly and easily search through millions of publications and journals in order to find relevant information.

Google Scholar also offers the ability to trace connections between different works, allowing researchers to stay abreast of recent developments in their field. With its user-friendly interface, Google Scholar makes researching easier than ever before.

Yes, Google Scholar articles are credible. They provide access to a wide range of academic literature from reliable sources such as peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings. Expert scrutiny has been conducted to guarantee the accuracy and excellence of the articles before they are put up on Google Scholar. Additionally, each article includes information about its authorship and citation count which can help readers assess their credibility further.

Google Scholar provides a convenient way to uncover pertinent material, assess the quality of these sources with ease, and be informed about novel advancements in your area through notifications. Thus, R&D supervisors should know how to use google scholar for research. Also, R&D supervisors considering utilizing Google Scholar for investigation ought to recall that this apparatus should not supplant customary techniques, for example, peer survey or manual searching; rather it should supplement them.

With its powerful search capabilities and ability to keep researchers informed about their fields of interest, using Google Scholar for research can save time while providing more accurate results than ever before.

Unlock the power of research with Cypris . Our platform provides rapid time to insights, enabling R&D and innovation teams to quickly access data sources for their projects.

Similar insights you might enjoy

Gallium Nitride Innovation Pulse

Carbon Capture & Storage Innovation Pulse

Sodium-Ion Batteries Innovation Pulse

Google Scholar

- Google Scholar Basics

Advanced Scholar Search

Accessing the advanced scholar search menu, advanced search features.

- Results Page

Much of the time, a simple keyword search will help you find what you need. However, there are times when you may want to have more control over what your search does. You may want to control the publication date, search for results by a particular author or in a particular journal, give synonyms, or remove unwanted results. When you need to do this, the Advanced Scholar Search menu can help.

- In the upper left corner of the page, press the button made of three horizontal lines to open a new menu.

- Advanced Search should be the second to last option in the newly-opened menu.

The Advanced Scholar Search menu has eight ways of searching, organized into three broad sections. You are able to mix and match these different search options together.

All / Exact Phrase / At Least One / Without

Helps you control the search words you are searching with.

- Words typed into the first search bar must all be included in your result. This is how a regular Google Scholar search works.

- You can also do this in the regular search bar by putting the words in quotes. Ex. "myocardial infarction"

- You can also do this in the regular search bar by putting "OR" in between your search words. Ex. Missouri politics OR government

- You can also do this in the regular search bar by putting a minus sign (-) before a word. Ex. Shakespeare -tragedies

Where My Words Occur

Controls where Google Scholar will look for your search words.

- Selecting "anywhere in the article" will likely turn up a larger number of results, because the search engine can look for your keywords in more places. This is the Google Scholar default.

- Selecting "in the title of the article" may help improve the relevance of your results, because if your keyword is in the title, it is likely more important to what the article is about.

Authored by/Published in/ Dated Between

- You can also do this in the regular search bar by putting "author:" before the author's name. Ex. intersectionality author:Crenshaw

- The second search bar lets you search for results in a particular scholarly journal . Google Scholar understands many common ways of abbreviating journal titles.

- You can also adjust this from the results page .

- << Previous: Google Scholar Basics

- Next: Results Page >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2023 11:21 AM

- URL: https://semo.libguides.com/google-scholar

Google Scholar: an Introduction to Google Scholar: Google Scholar Search Tips

- Master Google Scholar

- Google Scholar Search Tips

- Miscellaneous

- Search Google Scholar

1. Author search is one of the most effective ways to find a specific paper. If you know who wrote the paper you're looking for, you can simply add their last name to your search terms.

For example: The search [ friedman regression ] returns papers on the subject of regression written by people named Friedman. If you want to search on an author's full name, or last name and initials, enter the name in quotes: [ "jh friedman" ].

2. When a word is both a person's name and a common noun, you might want to use the "author:" operator . This operator only affects the search term that immediately follows it, and there must be no space between "author:" and your search term.

For example: [ author:flowers ] returns papers written by people with the name Flowers, whereas [ flowers -author:flowers ] returns papers about flowers, and ignores papers written by people with the name Flowers (a minus in front of a search term excludes results that contain this search term).

3. You may use the operator with an author's full name in quotes to further refine your search. Try to use initials rather than full first names, because some sources indexed in Google Scholar only provide the initials.

For example: To find papers by Donald E. Knuth, you could try [ author:"d knuth" ], [ author:"de knuth"] , or [ author:"donald e knuth" ].

1. Date-restricted searches can be effective when you're looking for the latest developments in a given area.

The dropdown menu labeled anytime , which is available on all search results pages, allows you to limit the search to commonly used recent periods.

The Advanced Scholar Search page allows you to restrict your search to other periods. Click on the down arrow in the search field to access the Advanced Scholar Search page.

For example: Here's how you'd search for articles on superconducting films that were published since 2004:

2. Bear in mind, however, that some web sources don't include publication dates, and a date-restricted search will not return articles for which Google Scholar was unable to determine a date of publication. So if you're sure that an article about superconducting films came out this year and a date-restricted search doesn't find it, retry the search without the date restriction.

Publication

(This option is only available on the Advanced Scholar Search page.)

1. A publication-restricted

- Plain-Text Editor

search only returns results with specific words from a specific publication.

For example: If you want to search the Journal of Finance for articles about mutual funds, you might start like this:

2. Keep in mind, however, that publication-restricted searches may be incomplete. Google Scholar gathers bibliographical data from many sources, including automatically extracting it from text and citations. This information may be incomplete or even incorrect; many preprints, for instance, don't say where (or even whether) the article was ultimately published.

In general, publication-restricted searches are effective if you're certain of what you're looking for, but they‘re often narrower than you might expect.

For instance: You might find that a search across all publications for [ mutual funds ] gives more useful results than a more specific search for "funds" only in the Journal of Finance .

3. Finally, bear in mind that one journal can be spelled several ways (e.g., Journal of Biological Chemistry is often abbreviated as J Biol Chem ), so you may need to try several spellings of a given publication in order to get complete search results.

Additional Search Tips

Be specific for best results , e.g. photography during the civil war, not just civil war.

After entering a search, use the facets on the left to narrow the results :

- target only peer-reviewed articles

- show only items with Full Text available online

- include/exclude newspaper articles, books, journal articles, and more

- limit your results by date, language, format or subject

Expanding your search

- Mark the facet on the left labeled "Add results beyond your library's collection" to search more places and include items not found in TCC Libraries. For items not available in the TCC Libraries collections, "r equest item through ILL " to place an interlibrary loan request for the item.

- Wildcards ( Wildcards cannot be used as the first character of a search.)

- The question mark (?) will match any one cha racter and can be used to find “Olsen” or “Olson” by searching for “Ols?n.”

- The asterisk (*) will match zero or more characters within a word or at the end of a word. A search for “Ch*ter” would match “Charter,” “Character,” and “Chapter.” When used at the end of a word, such as “Temp*,” it will match all suffixes “Temptation,” “Temple” and “Temporary.”

- Include Similar Terms in the Search : Use the tilde (~) character at the end of a word to match words that look similar. When used on the term “Lead~” it will match “Wead,” “Veade,” and “Tead.”

- << Previous: Master Google Scholar

- Next: Citations >>

- Last Updated: Mar 4, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.tulsacc.edu/googlescholar

Metro Campus Library : 918.595.7172 | Northeast Campus Library : 918.595.7501 | Southeast Campus Library : 918.595.7701 | West Campus Library : 918.595.8010 --> email: Library Website Technical Help | MyTCC | © 2024 Tulsa Community College

Reference management. Clean and simple.

The top list of academic search engines

1. Google Scholar

4. science.gov, 5. semantic scholar, 6. baidu scholar, get the most out of academic search engines, frequently asked questions about academic search engines, related articles.

Academic search engines have become the number one resource to turn to in order to find research papers and other scholarly sources. While classic academic databases like Web of Science and Scopus are locked behind paywalls, Google Scholar and others can be accessed free of charge. In order to help you get your research done fast, we have compiled the top list of free academic search engines.

Google Scholar is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only lets you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free but also often provides links to full-text PDF files.

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles

- Abstracts: only a snippet of the abstract is available

- Related articles: ✔

- References: ✔

- Cited by: ✔

- Links to full text: ✔

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, RIS, BibTeX

BASE is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany. That is also where its name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles (contains duplicates)

- Abstracts: ✔

- Related articles: ✘

- References: ✘

- Cited by: ✘

- Export formats: RIS, BibTeX

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open-access research papers. For each search result, a link to the full-text PDF or full-text web page is provided.

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles

- Links to full text: ✔ (all articles in CORE are open access)

- Export formats: BibTeX

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need anymore to query all those resources separately!

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles and reports

- Links to full text: ✔ (available for some databases)

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX (available for some databases)

Semantic Scholar is the new kid on the block. Its mission is to provide more relevant and impactful search results using AI-powered algorithms that find hidden connections and links between research topics.

- Coverage: approx. 40 million articles

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, BibTeX

Although Baidu Scholar's interface is in Chinese, its index contains research papers in English as well as Chinese.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 100 million articles

- Abstracts: only snippets of the abstract are available

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX

RefSeek searches more than one billion documents from academic and organizational websites. Its clean interface makes it especially easy to use for students and new researchers.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 1 billion documents

- Abstracts: only snippets of the article are available

- Export formats: not available

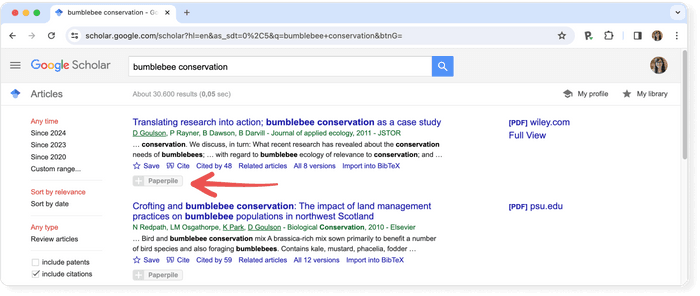

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to save, organize, and cite your references. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons:

Google Scholar is an academic search engine, and it is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only let's you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free, but also often provides links to full text PDF file.

Semantic Scholar is a free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature developed at the Allen Institute for AI. Sematic Scholar was publicly released in 2015 and uses advances in natural language processing to provide summaries for scholarly papers.

BASE , as its name suggest is an academic search engine. It is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany and that's where it name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open access research papers. For each search result a link to the full text PDF or full text web page is provided.

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need any more to query all those resources separately!

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

265k Accesses

15 Citations

705 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Sascha Kraus, Matthias Breier, … João J. Ferreira

Plagiarism in research

Gert Helgesson & Stefan Eriksson

Open peer review: promoting transparency in open science

Dietmar Wolfram, Peiling Wang, … Hyoungjoo Park

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

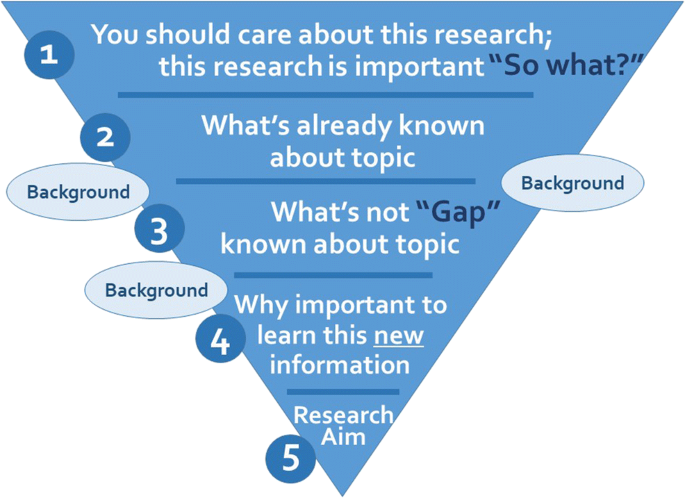

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

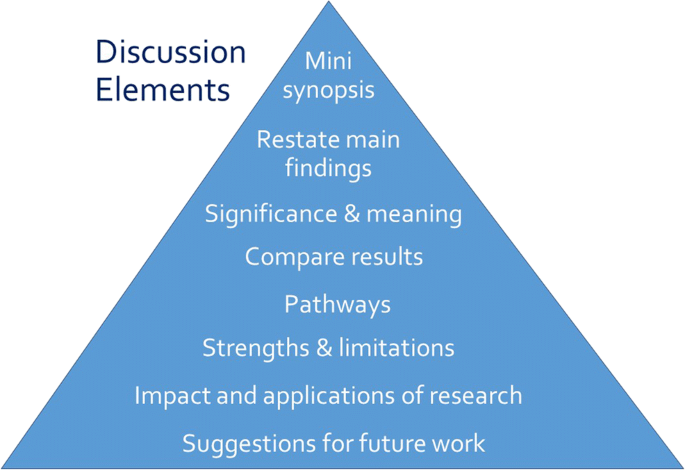

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

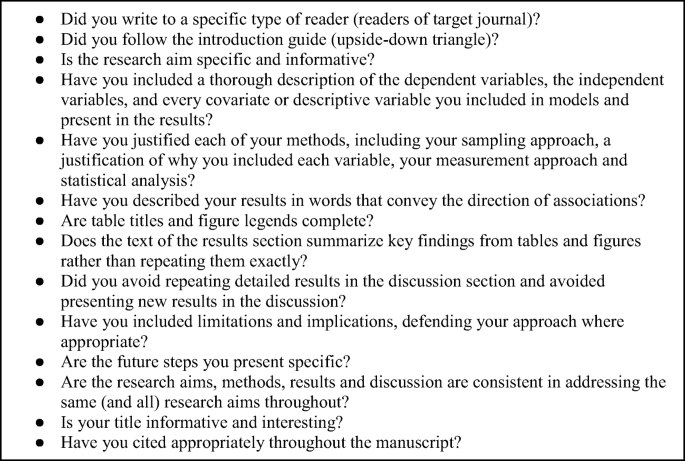

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Library databases

- Library website

Google Scholar: Search Google Scholar

Search tips for google scholar.

Google Scholar is very similar to Google; you can use many of the same search options.

- Google Scholar automatically places AND between words:

nurse stress retention

- Place quotation marks around phrases or titles:

"social learning theory"

"On the Origin of Species"

- Search for alternate terms using OR, with the terms enclosed in parentheses:

("first grade" OR "second grade")

(theory OR model)

You can also use the advanced Google Scholar search to create your search string. Creating a complex Google Scholar search can be difficult.

A good Google Scholar strategy is to try multiple searches, adjusting your keywords with each search.

- Learn more about Google Scholars advanced search.

Cited By feature in Google Scholar

Use the Cited by link to find articles and books that cite a specific article.

The cited by feature is a great way to find more recent articles and to trace an idea from its original source up to the present.

- Start by locating a single item in Google Scholar.

- Click the Cited by link to see a list of the items that cite your original item. Older and more influential items will have a higher number of Cited by results.

Advanced search options

For more complex searches, try Google Scholar's Advanced Search page.

- To access the advanced search option, click on the three line icon in the upper left corner of the Google Scholar search page.

The advanced search allows you to search more precisely.

- Use the articles dated between option to limit to specific years.

- Try the authored by search box to see resources by a specific author

- Explore the other search options to see what's most effective for your search, such as searching in specific journals, searching for exact phrases, and using different keyword strategies.

Watch a search

- Watch a search for a complicated topic using the advanced search feature.

See how the search differs between a library database and Google Scholar.

- Watch a search for a specific article by title.

Video: Google Scholar Advanced Search

(1 min 18 sec) Recorded January 2018 Transcript

Video: Find an article by title in Google Scholar

(2 min 38 sec) Recorded January 2018 Transcript

- Previous Page: Home

- Next Page: Google Scholar Results & Full Text

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Getting Better Results with Google Scholar

- Five Top Tips for Searching in Google Scholar

- What is Google Scholar? What is it for?

- Linking Google Scholar and the Libraries to get more content

- Google Scholar Advanced Searching

- Authors, cited references, cited works, etc.

- Collecting citation information from your Google Scholar profile

- Google Scholar Metrics for Faculty

- Some special search types

- Citing Your Sources

- Where Does It Originate?

- Google Datasets (beta)

Five Top Tips for Searching Google Scholar

1. Google Scholar doesn't have a thesaurus or list of subject terms, because it is skimming Web content that is created by others. You may have to use synonyms OR'ed together to draw a more complete set of citations. You must capitalize the OR to have it used as an operator, and it works better if the terms are enclosed in parentheses.

For example: (Twelfth Night OR 12th Night) for the play's title

2. You may use quotation marks around a phrase to make GS search for it as that phrase.

For example: ("Tomato Mosaic Virus" OR TMV)

For example: "Plutarch's Lives"

3. You can't use * as a truncation symbol; a stem word and * to get the endings, like comput*, doesn't work here. It may be used to replace a whole word in a phrase, such as "the * and future *" which would pick up phrases like "the Once and Future King." A colleague calls this the 'whole word wildcard'. GS does look for other forms of some words, such as plurals and related terms.

4. Search for specific authors using the "Initials or first name then lastname" format to get a better result--

for example, "LR Oliver" generally works better than Oliver, Lawrence R. although you can use both, such as ("LR Oliver" OR "Oliver, LR")

Also, you can use the author tag, which is the word author[no space]a colon[no space] and the author's name, such as author:Hawking

5. Google Scholar shows how many times works have been cited-- and as citations differ, the numbers may be spread among the variant citations. Check the citing publications for accuracy-- even if someone has an unusual name, the software can make mistakes. It does not allow sorting or removal of duplicates.

GS is not searching for ALL possible relevant publications. It often doesn't show all cited references to books or book chapters. You may need to use subject databases to get a comprehensive search.

GS isn't the best choice for systematic reviews because what is retrieved varies by whether a particular person is logged in, that it isn't comprehensive, and that it will change over time, even day to day.

Bonus tip: "sort by date" will only offer the references published in the last year.

Searching in Google Scholar: +, -, OR

Search Google Scholar using your chosen terms. Context searching is better than it used to be. An AND is assumed between words. OR works only if in capital letters. NOT or the minus sign - can be used to exclude terms . Do not put a space between the mark and the search term.

For example, searches like:

"James Joyce" Ulysses (oeuvre OR "body of work")

"water quality" (benthic OR lotic) macroinvertebrates -riparian

should work better than typing complete sentences.

Use the "Find It!at UARK" link [more direct] to locate items if you have set your preferences to work with our Libraries' pages. Or use the links to other campuses or sources, being aware that they may or may not allow you to have the material.

- Searching 101, a brief video by Ruth G. at Concordia University Libraries, in Wisconsin

Hyphenation--Yes and No

Styles differ; some people use a hyphen between parts of a hyphenated word, and some use a space. Google and GS retrieve both versions of the term, up to a point. If a hyphen (–) shows up in a query, e.g., [parti-colored], it searches for:

- the term with the hyphen, e.g., parti-colored

- the term without the hyphen, e.g., particolored

- the term with the hyphen replaced by a space, e.g., parti colored

If you want to get a comprehensive search for a hyphenated word, you are better off using quotation marks around the parts, since searches of versions of the word without a hyphen or space won't find versions of the word which do include them.

So, "parti-colored" gets particolored, parti colored and parti-colored. But particolored only gets itself.

I rescued a big dog who was greyish brown, black, tan and white. The vet tech wrote that she was parti-colored, but she spelled it party-colored, which was very appropriate for her. She loved a party, especially if snacks were involved.

Some of this box's content is paraphrased from http://www.googleguide.com/interpreting_queries.html.

- << Previous: Linking Google Scholar and the Libraries to get more content

- Next: Google Scholar Advanced Searching >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 2:51 PM

- URL: https://uark.libguides.com/googlescholar

- See us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Phone: 479-575-4104

A Short Review on the Current Understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Hye ran park.

1 Department of Neurosurgery, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul 03080, Korea.

Jae Meen Lee

Hyo eun moon, dong soo lee.

2 Department of Nuclear Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, Korea.

Bung-Nyun Kim

3 Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, Korea.

Jinhyun Kim

4 Center for Functional Connectomics, Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), Seoul 02792, Korea.

Dong Gyu Kim

Sun ha paek.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a deficit in social behaviors and nonverbal interactions such as reduced eye contact, facial expression, and body gestures in the first 3 years of life. It is not a single disorder, and it is broadly considered to be a multi-factorial disorder resulting from genetic and non-genetic risk factors and their interaction. Genetic studies of ASD have identified mutations that interfere with typical neurodevelopment in utero through childhood. These complexes of genes have been involved in synaptogenesis and axon motility. Recent developments in neuroimaging studies have provided many important insights into the pathological changes that occur in the brain of patients with ASD in vivo. Especially, the role of amygdala, a major component of the limbic system and the affective loop of the cortico-striatothalamo-cortical circuit, in cognition and ASD has been proved in numerous neuropathological and neuroimaging studies. Besides the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens is also considered as the key structure which is related with the social reward response in ASD. Although educational and behavioral treatments have been the mainstay of the management of ASD, pharmacological and interventional treatments have also shown some benefit in subjects with ASD. Also, there have been reports about few patients who experienced improvement after deep brain stimulation, one of the interventional treatments. The key architecture of ASD development which could be a target for treatment is still an uncharted territory. Further work is needed to broaden the horizons on the understanding of ASD.

INTRODUCTION

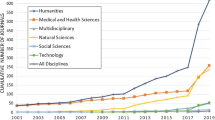

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by a lack of social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication in the first 3 years of life. The distinctive social behaviors include an avoidance of eye contact, problems with emotional control or understanding the emotions of others, and a markedly restricted range of activities and interests [ 1 ]. The current prevalence of ASD in the latest large-scale surveys is about 1%~2% [ 2 , 3 ]. The prevalence of ASD has increased in the past two decades [ 4 ]. Although the increase in prevalence is partially the result of changes in DSM diagnostic criteria and younger age of diagnosis, an increase in risk factors cannot be ruled out [ 5 , 6 ]. Studies have shown a male predominance; ASD affects 2~3 times more males than females [ 2 , 3 , 7 ]. This diagnostic bias towards males might result from under-recognition of females with ASD [ 8 ]. Also, some researchers have suggested the possibility that the female-specific protective effects against ASD might exist [ 9 ].