- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility Accessibility

- StudentHome

Help Centre

Introduction writing in your own words.

Writing a good assignment requires building a well structured argument with logical progression, using supporting evidence. This can include quotations taken directly from other sources, paraphrasing someone else’s writing, or referring to other published work.

Including supporting evidence demonstrates that your work is rigorous – you show that you have read the relevant books and articles and that you can back up the assertions made in your argument. You do this by

- directly quoting what another academic has said in a book or article (quoting)

- describing that academic’s work but putting it in your own words (paraphrasing)

- stating a fact or research finding and acknowledging where you found it (referencing).

Make it balanced and logical

If you're asked to make an argument for a particular theory or approach, make sure that you make a balanced use of evidence to support your argument. Don't select only those facts or pieces of evidence that support your argument and ignore competing material.

Understand the difference between fact and conjecture. If what you are discussing is only possibly true, not definitely true, you should make that clear with phrases such as: 'this suggests that ...', or 'it is possible that ...'. This is a requirement in all academic disciplines, but is particularly important in science and technology subjects.

I personally would prefer a short concise essay or assignment that actually addresses the real question that you're being asked rather than pages and pages on the issue. You just won't get marks for that. All the courses are about showing your understanding. Eulina (OU tutor)

Useful resources

A collection of free courses from OpenLearn designed to help you develop good academic practice.

The OU Library's page on how to cite the original material you refer to in your assignments.

OU Library webpage leading to useful online dictionaries and thesauri, some of which are subject-specific.

What it means, the process and who to contact for support.

Last updated 3 months ago

The Open University

Follow us on social media.

- Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

© . . .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write in Your Own Words

Last Updated: January 18, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Michelle Golden, PhD . Michelle Golden is an English teacher in Athens, Georgia. She received her MA in Language Arts Teacher Education in 2008 and received her PhD in English from Georgia State University in 2015. There are 15 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 221,673 times.

Writing a strong essay combines original composition with the incorporation of solid research. Taking the words and ideas of others and weaving them seamlessly into your essay requires skill and finesse. By learning how to paraphrase, exploring how and when to incorporate direct quotes, and by expanding your writing tool-kit more generally, you will be well on your way to writing effectively in your own words.

Learning to Paraphrase

- Take notes, if you have to. If this is your personal text book and not a borrowed one, consider highlighting the text or writing in the margins.

- If you are working digitally, avoid using "copy" and "paste."

- You don't have to write it down word-for-word. Just write the gist of the passage.

- Specific style-guides change often. If you are using a style-guide text book, make sure that it is the more recent version. Another option is to use a website.

Quoting Effectively

- Argue against another author’s specific idea

- Continue another author’s specific idea

- Prove your own point with the help of another author

- Add eloquence or power with a very meaningful quote

- In his book End of Humanism , Richard Schechner states, “I prefer to work from primary sources: what I’ve done, what I’ve seen” (15).

- As Dixon and Foster explain in their book Experimental Cinema , “filmmakers assumed that the audience for their films was to be an intimate group of knowledgeable cineastes” (225).

- In general, your quote should not exceed 3-4 lines of text. If it does (and it is truly necessary), you will need to use block quote formatting.

- At the end of the quote, include any relevant data that you have not already stated, such as the name of the author, the page number, and/or the date of publication. [11] X Research source

- If there is no specific author, then use the editor instead, or whatever your specific style-guide requires.

Building Your Writing Tool-kit

- When you encounter a word you don’t know, look it up!

- Browse a dictionary or thesaurus for fun.

- Talk to others. The spoken word is a great source of new and exciting vocabulary.

- A good resource is Strunk and White’s Elements of Style .

- Another great resources is Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft .

- Theme: A common thread or idea that is appears throughout a literary work.

- Symbolism: An object, character, or color that is used to represent an important idea or concept.

- Dramatic Irony: Irony that occurs when the meaning of the situation is understood by the audience but not by the characters.

Community Q&A

- Using a dictionary or thesaurus is not a bad thing when writing. But they should be used when you have a full and complete thought in your head and have already written it out in simple form without their help. Once completed, develop your thought using similar words, or blend sentences using new words. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 1

- Writing is best accomplished when you have a fresh and open mind -- that means it isn't good to write just before bed. Try writing in the morning, but after breakfast, or before or after dinner in the evening. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 1

- Public libraries are a perfect place to not only find books, but to establish a reading schedule. Many libraries can help you form a list of books that become progressively more difficult and challenging. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 1

- Avoid using several words that all mean the same thing. For example, if something is small, and tiny, the general idea is that something is small. Don't over-use your vocabulary. Thanks Helpful 4 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/using_research/quoting_paraphrasing_and_summarizing/paraphrasing.html

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/QPA_paraphrase2.html ,

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/QPA_paraphrase.html

- ↑ http://www.plagiarism.org/citing-sources/how-to-paraphrase/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/quotations/

- ↑ http://www.ramapo.edu/crw/files/2012/07/5-Step-Approach-to-Incorporating-Quoted-Material.pdf

- ↑ https://web.ccis.edu/Offices/AcademicResources/WritingCenter/EssayWritingAssistance/SuggestedWaystoIntroduceQuotations.aspx

- ↑ https://pitt.libguides.com/citationhelp

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/02/

- ↑ http://www.plagiarism.org/citing-sources/quoting-material/

- ↑ https://success.oregonstate.edu/learning/reading

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/12/how-improve-enlarge-vocabulary-english-memory

- ↑ https://grammar.yourdictionary.com/grammar-rules-and-tips/11-rules-of-grammar.html

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/literary-devices/

- ↑ https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/chapter/types-of-writing-styles/

About This Article

To avoid plagiarism, you’ll need to write other people’s ideas in your own words. Start by reading through the text to make sure you understand it. Then, put it away and try to write down the main ideas like you’re explaining them to a friend. When you’re finished, read your writing back to check it makes sense. Finally, compare it to the original text to see if you missed any important information. If you did, re-write it to include the extra details. Make sure you cite the text you paraphrased using your class's given style guide. That way, you won't get in trouble for plagiarism. For more tips from our English co-author, including how to quote texts in an essay, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Michael Leep

Oct 13, 2016

Did this article help you?

Jan 30, 2017

Ashley-Lynn Thompson

Apr 4, 2017

Mar 10, 2017

Anomin Fefe

Nov 18, 2021

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Assignments

Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine

Introduction

Assignments are a common method of assessment at university and require careful planning and good quality research. Developing critical thinking and writing skills are also necessary to demonstrate your ability to understand and apply information about your topic. It is not uncommon to be unsure about the processes of writing assignments at university.

- You may be returning to study after a break

- You may have come from an exam based assessment system and never written an assignment before

- Maybe you have written assignments but would like to improve your processes and strategies

This chapter has a collection of resources that will provide you with the skills and strategies to understand assignment requirements and effectively plan, research, write and edit your assignments. It begins with an explanation of how to analyse an assignment task and start putting your ideas together. It continues by breaking down the components of academic writing and exploring the elements you will need to master in your written assignments. This is followed by a discussion of paraphrasing and synthesis, and how you can use these strategies to create a strong, written argument. The chapter concludes with useful checklists for editing and proofreading to help you get the best possible mark for your work.

Task Analysis and Deconstructing an Assignment

It is important that before you begin researching and writing your assignments you spend sufficient time understanding all the requirements. This will help make your research process more efficient and effective. Check your subject information such as task sheets, criteria sheets and any additional information that may be in your subject portal online. Seek clarification from your lecturer or tutor if you are still unsure about how to begin your assignments.

The task sheet typically provides key information about an assessment including the assignment question. It can be helpful to scan this document for topic, task and limiting words to ensure that you fully understand the concepts you are required to research, how to approach the assignment, and the scope of the task you have been set. These words can typically be found in your assignment question and are outlined in more detail in the two tables below (see Table 19.1 and Table 19.2 ).

Table 19.1 Parts of an Assignment Question

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the task word requires you to address.

Table 19.2 Task words

The criteria sheet , also known as the marking sheet or rubric, is another important document to look at before you begin your assignment. The criteria sheet outlines how your assignment will be marked and should be used as a checklist to make sure you have included all the information required.

The task or criteria sheet will also include the:

- Word limit (or word count)

- Referencing style and research expectations

- Formatting requirements

Task analysis and criteria sheets are also discussed in the chapter Managing Assessments for a more detailed discussion on task analysis, criteria sheets, and marking rubrics.

Preparing your ideas

Brainstorm or concept map: List possible ideas to address each part of the assignment task based on what you already know about the topic from lectures and weekly readings.

Finding appropriate information: Learn how to find scholarly information for your assignments which is

See the chapter Working With Information for a more detailed explanation .

What is academic writing?

Academic writing tone and style.

Many of the assessment pieces you prepare will require an academic writing style. This is sometimes called ‘academic tone’ or ‘academic voice’. This section will help you to identify what is required when you are writing academically (see Table 19.3 ). The best way to understand what academic writing looks like, is to read broadly in your discipline area. Look at how your course readings, or scholarly sources, are written. This will help you identify the language of your discipline field, as well as how other writers structure their work.

Table 19.3 Comparison of academic and non-academic writing

Thesis statements.

Essays are a common form of assessment that you will likely encounter during your university studies. You should apply an academic tone and style when writing an essay, just as you would in in your other assessment pieces. One of the most important steps in writing an essay is constructing your thesis statement. A thesis statement tells the reader the purpose, argument or direction you will take to answer your assignment question. A thesis statement may not be relevant for some questions, if you are unsure check with your lecturer. The thesis statement:

- Directly relates to the task . Your thesis statement may even contain some of the key words or synonyms from the task description.

- Does more than restate the question.

- Is specific and uses precise language.

- Let’s your reader know your position or the main argument that you will support with evidence throughout your assignment.

- The subject is the key content area you will be covering.

- The contention is the position you are taking in relation to the chosen content.

Your thesis statement helps you to structure your essay. It plays a part in each key section: introduction, body and conclusion.

Planning your assignment structure

When planning and drafting assignments, it is important to consider the structure of your writing. Academic writing should have clear and logical structure and incorporate academic research to support your ideas. It can be hard to get started and at first you may feel nervous about the size of the task, this is normal. If you break your assignment into smaller pieces, it will seem more manageable as you can approach the task in sections. Refer to your brainstorm or plan. These ideas should guide your research and will also inform what you write in your draft. It is sometimes easier to draft your assignment using the 2-3-1 approach, that is, write the body paragraphs first followed by the conclusion and finally the introduction.

Writing introductions and conclusions

Clear and purposeful introductions and conclusions in assignments are fundamental to effective academic writing. Your introduction should tell the reader what is going to be covered and how you intend to approach this. Your conclusion should summarise your argument or discussion and signal to the reader that you have come to a conclusion with a final statement. These tips below are based on the requirements usually needed for an essay assignment, however, they can be applied to other assignment types.

Writing introductions

Most writing at university will require a strong and logically structured introduction. An effective introduction should provide some background or context for your assignment, clearly state your thesis and include the key points you will cover in the body of the essay in order to prove your thesis.

Usually, your introduction is approximately 10% of your total assignment word count. It is much easier to write your introduction once you have drafted your body paragraphs and conclusion, as you know what your assignment is going to be about. An effective introduction needs to inform your reader by establishing what the paper is about and provide four basic things:

- A brief background or overview of your assignment topic

- A thesis statement (see section above)

- An outline of your essay structure

- An indication of any parameters or scope that will/ will not be covered, e.g. From an Australian perspective.

The below example demonstrates the four different elements of an introductory paragraph.

1) Information technology is having significant effects on the communication of individuals and organisations in different professions. 2) This essay will discuss the impact of information technology on the communication of health professionals. 3) First, the provision of information technology for the educational needs of nurses will be discussed. 4) This will be followed by an explanation of the significant effects that information technology can have on the role of general practitioner in the area of public health. 5) Considerations will then be made regarding the lack of knowledge about the potential of computers among hospital administrators and nursing executives. 6) The final section will explore how information technology assists health professionals in the delivery of services in rural areas . 7) It will be argued that information technology has significant potential to improve health care and medical education, but health professionals are reluctant to use it.

1 Brief background/ overview | 2 Indicates the scope of what will be covered | 3-6 Outline of the main ideas (structure) | 7 The thesis statement

Note : The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing conclusions

You should aim to end your assignments with a strong conclusion. Your conclusion should restate your thesis and summarise the key points you have used to prove this thesis. Finish with a key point as a final impactful statement. Similar to your introduction, your conclusion should be approximately 10% of the total assignment word length. If your assessment task asks you to make recommendations, you may need to allocate more words to the conclusion or add a separate recommendations section before the conclusion. Use the checklist below to check your conclusion is doing the right job.

Conclusion checklist

- Have you referred to the assignment question and restated your argument (or thesis statement), as outlined in the introduction?

- Have you pulled together all the threads of your essay into a logical ending and given it a sense of unity?

- Have you presented implications or recommendations in your conclusion? (if required by your task).

- Have you added to the overall quality and impact of your essay? This is your final statement about this topic; thus, a key take-away point can make a great impact on the reader.

- Remember, do not add any new material or direct quotes in your conclusion.

This below example demonstrates the different elements of a concluding paragraph.

1) It is evident, therefore, that not only do employees need to be trained for working in the Australian multicultural workplace, but managers also need to be trained. 2) Managers must ensure that effective in-house training programs are provided for migrant workers, so that they become more familiar with the English language, Australian communication norms and the Australian work culture. 3) In addition, Australian native English speakers need to be made aware of the differing cultural values of their workmates; particularly the different forms of non-verbal communication used by other cultures. 4) Furthermore, all employees must be provided with clear and detailed guidelines about company expectations. 5) Above all, in order to minimise communication problems and to maintain an atmosphere of tolerance, understanding and cooperation in the multicultural workplace, managers need to have an effective knowledge about their employees. This will help employers understand how their employee’s social conditioning affects their beliefs about work. It will develop their communication skills to develop confidence and self-esteem among diverse work groups. 6) The culturally diverse Australian workplace may never be completely free of communication problems, however, further studies to identify potential problems and solutions, as well as better training in cross cultural communication for managers and employees, should result in a much more understanding and cooperative environment.

1 Reference to thesis statement – In this essay the writer has taken the position that training is required for both employees and employers . | 2-5 Structure overview – Here the writer pulls together the main ideas in the essay. | 6 Final summary statement that is based on the evidence.

Note: The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing paragraphs

Paragraph writing is a key skill that enables you to incorporate your academic research into your written work. Each paragraph should have its own clearly identified topic sentence or main idea which relates to the argument or point (thesis) you are developing. This idea should then be explained by additional sentences which you have paraphrased from good quality sources and referenced according to the recommended guidelines of your subject (see the chapter Working with Information ). Paragraphs are characterised by increasing specificity; that is, they move from the general to the specific, increasingly refining the reader’s understanding. A common structure for paragraphs in academic writing is as follows.

Topic Sentence

This is the main idea of the paragraph and should relate to the overall issue or purpose of your assignment is addressing. Often it will be expressed as an assertion or claim which supports the overall argument or purpose of your writing.

Explanation/ Elaboration

The main idea must have its meaning explained and elaborated upon. Think critically, do not just describe the idea.

These explanations must include evidence to support your main idea. This information should be paraphrased and referenced according to the appropriate referencing style of your course.

Concluding sentence (critical thinking)

This should explain why the topic of the paragraph is relevant to the assignment question and link to the following paragraph.

Use the checklist below to check your paragraphs are clear and well formed.

Paragraph checklist

- Does your paragraph have a clear main idea?

- Is everything in the paragraph related to this main idea?

- Is the main idea adequately developed and explained?

- Do your sentences run together smoothly?

- Have you included evidence to support your ideas?

- Have you concluded the paragraph by connecting it to your overall topic?

Writing sentences

Make sure all the sentences in your paragraphs make sense. Each sentence must contain a verb to be a complete sentence. Avoid sentence fragments . These are incomplete sentences or ideas that are unfinished and create confusion for your reader. Avoid also run on sentences . This happens when you join two ideas or clauses without using the appropriate punctuation. This also confuses your meaning (See the chapter English Language Foundations for examples and further explanation).

Use transitions (linking words and phrases) to connect your ideas between paragraphs and make your writing flow. The order that you structure the ideas in your assignment should reflect the structure you have outlined in your introduction. Refer to transition words table in the chapter English Language Foundations.

Paraphrasing and Synthesising

Paraphrasing and synthesising are powerful tools that you can use to support the main idea of a paragraph. It is likely that you will regularly use these skills at university to incorporate evidence into explanatory sentences and strengthen your essay. It is important to paraphrase and synthesise because:

- Paraphrasing is regarded more highly at university than direct quoting.

- Paraphrasing can also help you better understand the material.

- Paraphrasing and synthesising demonstrate you have understood what you have read through your ability to summarise and combine arguments from the literature using your own words.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is changing the writing of another author into your words while retaining the original meaning. You must acknowledge the original author as the source of the information in your citation. Follow the steps in this table to help you build your skills in paraphrasing (see Table 19.4 ).

Table 19.4 Paraphrasing techniques

Example of paraphrasing.

Please note that these examples and in text citations are for instructional purposes only.

Original text

Health care professionals assist people often when they are at their most vulnerable . To provide the best care and understand their needs, workers must demonstrate good communication skills . They must develop patient trust and provide empathy to effectively work with patients who are experiencing a variety of situations including those who may be suffering from trauma or violence, physical or mental illness or substance abuse (French & Saunders, 2018).

Poor quality paraphrase example

This is a poor example of paraphrasing. Some synonyms have been used and the order of a few words changed within the sentences however the colours of the sentences indicate that the paragraph follows the same structure as the original text.

Health care sector workers are often responsible for vulnerable patients. To understand patients and deliver good service , they need to be excellent communicators . They must establish patient rapport and show empathy if they are to successfully care for patients from a variety of backgrounds and with different medical, psychological and social needs (French & Saunders, 2018).

A good quality paraphrase example

This example demonstrates a better quality paraphrase. The author has demonstrated more understanding of the overall concept in the text by using the keywords as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up to see how much the structure has changed from the original text.

Empathetic communication is a vital skill for health care workers. Professionals in these fields are often responsible for patients with complex medical, psychological and social needs. Empathetic communication assists in building rapport and gaining the necessary trust to assist these vulnerable patients by providing appropriate supportive care (French & Saunders, 2018).

The good quality paraphrase example demonstrates understanding of the overall concept in the text by using key words as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up, which indicates how much the structure has changed from the original text.

What is synthesising?

Synthesising means to bring together more than one source of information to strengthen your argument. Once you have learnt how to paraphrase the ideas of one source at a time, you can consider adding additional sources to support your argument. Synthesis demonstrates your understanding and ability to show connections between multiple pieces of evidence to support your ideas and is a more advanced academic thinking and writing skill.

Follow the steps in this table to improve your synthesis techniques (see Table 19.5 ).

Table 19.5 Synthesising techniques

Example of synthesis

There is a relationship between academic procrastination and mental health outcomes. Procrastination has been found to have a negative effect on students’ well-being (Balkis, & Duru, 2016). Yerdelen, McCaffrey, and Klassens’ (2016) research results suggested that there was a positive association between procrastination and anxiety. This was corroborated by Custer’s (2018) findings which indicated that students with higher levels of procrastination also reported greater levels of the anxiety. Therefore, it could be argued that procrastination is an ineffective learning strategy that leads to increased levels of distress.

Topic sentence | Statements using paraphrased evidence | Critical thinking (student voice) | Concluding statement – linking to topic sentence

This example demonstrates a simple synthesis. The author has developed a paragraph with one central theme and included explanatory sentences complete with in-text citations from multiple sources. Note how the blocks of colour have been used to illustrate the paragraph structure and synthesis (i.e., statements using paraphrased evidence from several sources). A more complex synthesis may include more than one citation per sentence.

Creating an argument

What does this mean.

Throughout your university studies, you may be asked to ‘argue’ a particular point or position in your writing. You may already be familiar with the idea of an argument, which in general terms means to have a disagreement with someone. Similarly, in academic writing, if you are asked to create an argument, this means you are asked to have a position on a particular topic, and then justify your position using evidence.

What skills do you need to create an argument?

In order to create a good and effective argument, you need to be able to:

- Read critically to find evidence

- Plan your argument

- Think and write critically throughout your paper to enhance your argument

For tips on how to read and write critically, refer to the chapter Thinking for more information. A formula for developing a strong argument is presented below.

A formula for a good argument

What does an argument look like?

As can be seen from the figure above, including evidence is a key element of a good argument. While this may seem like a straightforward task, it can be difficult to think of wording to express your argument. The table below provides examples of how you can illustrate your argument in academic writing (see Table 19.6 ).

Table 19.6 Argument

Editing and proofreading (reviewing).

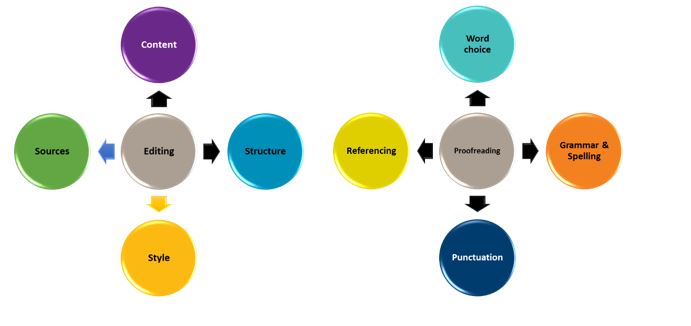

Once you have finished writing your first draft it is recommended that you spend time revising your work. Proofreading and editing are two different stages of the revision process.

- Editing considers the overall focus or bigger picture of the assignment

- Proofreading considers the finer details

As can be seen in the figure above there are four main areas that you should review during the editing phase of the revision process. The main things to consider when editing include content, structure, style, and sources. It is important to check that all the content relates to the assignment task, the structure is appropriate for the purposes of the assignment, the writing is academic in style, and that sources have been adequately acknowledged. Use the checklist below when editing your work.

Editing checklist

- Have I answered the question accurately?

- Do I have enough credible, scholarly supporting evidence?

- Is my writing tone objective and formal enough or have I used emotive and informal language?

- Have I written in the third person not the first person?

- Do I have appropriate in-text citations for all my information?

- Have I included the full details for all my in-text citations in my reference list?

There are also several key things to look out for during the proofreading phase of the revision process. In this stage it is important to check your work for word choice, grammar and spelling, punctuation and referencing errors. It can be easy to mis-type words like ‘from’ and ‘form’ or mix up words like ‘trail’ and ‘trial’ when writing about research, apply American rather than Australian spelling, include unnecessary commas or incorrectly format your references list. The checklist below is a useful guide that you can use when proofreading your work.

Proofreading checklist

- Is my spelling and grammar accurate?

- Are they complete?

- Do they all make sense?

- Do they only contain only one idea?

- Do the different elements (subject, verb, nouns, pronouns) within my sentences agree?

- Are my sentences too long and complicated?

- Do they contain only one idea per sentence?

- Is my writing concise? Take out words that do not add meaning to your sentences.

- Have I used appropriate discipline specific language but avoided words I don’t know or understand that could possibly be out of context?

- Have I avoided discriminatory language and colloquial expressions (slang)?

- Is my referencing formatted correctly according to my assignment guidelines? (for more information on referencing refer to the Managing Assessment feedback section).

This chapter has examined the experience of writing assignments. It began by focusing on how to read and break down an assignment question, then highlighted the key components of essays. Next, it examined some techniques for paraphrasing and summarising, and how to build an argument. It concluded with a discussion on planning and structuring your assignment and giving it that essential polish with editing and proof-reading. Combining these skills and practising them, can greatly improve your success with this very common form of assessment.

- Academic writing requires clear and logical structure, critical thinking and the use of credible scholarly sources.

- A thesis statement is important as it tells the reader the position or argument you have adopted in your assignment. Not all assignments will require a thesis statement.

- Spending time analysing your task and planning your structure before you start to write your assignment is time well spent.

- Information you use in your assignment should come from credible scholarly sources such as textbooks and peer reviewed journals. This information needs to be paraphrased and referenced appropriately.

- Paraphrasing means putting something into your own words and synthesising means to bring together several ideas from sources.

- Creating an argument is a four step process and can be applied to all types of academic writing.

- Editing and proofreading are two separate processes.

Academic Skills Centre. (2013). Writing an introduction and conclusion . University of Canberra, accessed 13 August, 2013, http://www.canberra.edu.au/studyskills/writing/conclusions

Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2016). Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: underregulation or misregulation form. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31 (3), 439-459.

Custer, N. (2018). Test anxiety and academic procrastination among prelicensure nursing students. Nursing education perspectives, 39 (3), 162-163.

Yerdelen, S., McCaffrey, A., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Longitudinal examination of procrastination and anxiety, and their relation to self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: Latent growth curve modeling. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16 (1).

Writing Assignments Copyright © 2021 by Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

5 tips on writing better university assignments

Lecturer in Student Learning and Communication Development, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Alexandra Garcia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

University life comes with its share of challenges. One of these is writing longer assignments that require higher information, communication and critical thinking skills than what you might have been used to in high school. Here are five tips to help you get ahead.

1. Use all available sources of information

Beyond instructions and deadlines, lecturers make available an increasing number of resources. But students often overlook these.

For example, to understand how your assignment will be graded, you can examine the rubric . This is a chart indicating what you need to do to obtain a high distinction, a credit or a pass, as well as the course objectives – also known as “learning outcomes”.

Other resources include lecture recordings, reading lists, sample assignments and discussion boards. All this information is usually put together in an online platform called a learning management system (LMS). Examples include Blackboard , Moodle , Canvas and iLearn . Research shows students who use their LMS more frequently tend to obtain higher final grades.

If after scrolling through your LMS you still have questions about your assignment, you can check your lecturer’s consultation hours.

2. Take referencing seriously

Plagiarism – using somebody else’s words or ideas without attribution – is a serious offence at university. It is a form of cheating.

In many cases, though, students are unaware they have cheated. They are simply not familiar with referencing styles – such as APA , Harvard , Vancouver , Chicago , etc – or lack the skills to put the information from their sources into their own words.

To avoid making this mistake, you may approach your university’s library, which is likely to offer face-to-face workshops or online resources on referencing. Academic support units may also help with paraphrasing.

You can also use referencing management software, such as EndNote or Mendeley . You can then store your sources, retrieve citations and create reference lists with only a few clicks. For undergraduate students, Zotero has been recommended as it seems to be more user-friendly.

Using this kind of software will certainly save you time searching for and formatting references. However, you still need to become familiar with the citation style in your discipline and revise the formatting accordingly.

3. Plan before you write

If you were to build a house, you wouldn’t start by laying bricks at random. You’d start with a blueprint. Likewise, writing an academic paper requires careful planning: you need to decide the number of sections, their organisation, and the information and sources you will include in each.

Research shows students who prepare detailed outlines produce higher-quality texts. Planning will not only help you get better grades, but will also reduce the time you spend staring blankly at the screen thinking about what to write next.

During the planning stage, using programs like OneNote from Microsoft Office or Outline for Mac can make the task easier as they allow you to organise information in tabs. These bits of information can be easily rearranged for later drafting. Navigating through the tabs is also easier than scrolling through a long Word file.

4. Choose the right words

Which of these sentences is more appropriate for an assignment?

a. “This paper talks about why the planet is getting hotter”, or b. “This paper examines the causes of climate change”.

The written language used at university is more formal and technical than the language you normally use in social media or while chatting with your friends. Academic words tend to be longer and their meaning is also more precise. “Climate change” implies more than just the planet “getting hotter”.

To find the right words, you can use SkELL , which shows you the words that appear more frequently, with your search entry categorised grammatically. For example, if you enter “paper”, it will tell you it is often the subject of verbs such as “present”, “describe”, “examine” and “discuss”.

Another option is the Writefull app, which does a similar job without having to use an online browser.

5. Edit and proofread

If you’re typing the last paragraph of the assignment ten minutes before the deadline, you will be missing a very important step in the writing process: editing and proofreading your text. A 2018 study found a group of university students did significantly better in a test after incorporating the process of planning, drafting and editing in their writing.

You probably already know to check the spelling of a word if it appears underlined in red. You may even use a grammar checker such as Grammarly . However, no software to date can detect every error and it is not uncommon to be given inaccurate suggestions.

So, in addition to your choice of proofreader, you need to improve and expand your grammar knowledge. Check with the academic support services at your university if they offer any relevant courses.

Written communication is a skill that requires effort and dedication. That’s why universities are investing in support services – face-to-face workshops, individual consultations, and online courses – to help students in this process. You can also take advantage of a wide range of web-based resources such as spell checkers, vocabulary tools and referencing software – many of them free.

Improving your written communication will help you succeed at university and beyond.

- College assignments

- University study

- Writing tips

- Essay writing

- Student assessment

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Program Manager, Scholarly Development (Research)

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

NCI LIBRARY

Academic writing skills guide: structuring your assignment.

- Key Features of Academic Writing

- The Writing Process

- Understanding Assignments

- Brainstorming Techniques

- Planning Your Assignments

- Thesis Statements

- Writing Drafts

- Structuring Your Assignment

- How to Deal With Writer's Block

- Using Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Introductions

- Revising & Editing

- Proofreading

- Grammar & Punctuation

- Reporting Verbs

- Signposting, Transitions & Linking Words/Phrases

- Using Lecturers' Feedback

Keep referring back to the question and assignment brief and make sure that your structure matches what you have been asked to do and check to see if you have appropriate and sufficient evidence to support all of your points. Plans can be structured/restructured at any time during the writing process.

Once you have decided on your key point(s), draw a line through any points that no longer seem to fit. This will mean you are eliminating some ideas and potentially letting go of one or two points that you wanted to make. However, this process is all about improving the relevance and coherence of your writing. Writing involves making choices, including the tough choice to sideline ideas that, however promising, do not fit into your main discussion.

Eventually, you will have a structure that is detailed enough for you to start writing. You will know which ideas go into each section and, ideally, each paragraph and in what order. You will also know which evidence for those ideas from your notes you will be using for each section and paragraph.

Once you have a map/framework of the proposed structure, this forms the skeleton of your assignment and if you have invested enough time and effort into researching and brainstorming your ideas beforehand, it should make it easier to flesh it out. Ultimately, you are aiming for a final draft where you can sum up each paragraph in a couple of words as each paragraph focuses on one main point or idea.

Communications from the Library: Please note all communications from the library, concerning renewal of books, overdue books and reservations will be sent to your NCI student email account.

- << Previous: Writing Drafts

- Next: How to Deal With Writer's Block >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 1:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ncirl.ie/academic_writing_skills

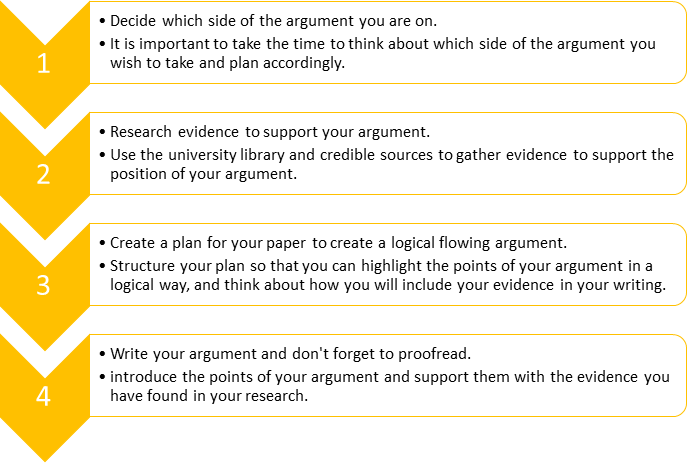

- Steps for writing assignments

- Information and services

- Student support

- Study skills and learning advice

- Study skills and learning advice overview