- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Migration Studies

- Editorial Board

- Call for Papers

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. studies of migration studies, 3. methodology, 4. metadata on migration studies, 5. topic clusters in migration studies, 6. trends in topic networks in migration studies, 7. conclusions, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Mapping migration studies: An empirical analysis of the coming of age of a research field

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Asya Pisarevskaya, Nathan Levy, Peter Scholten, Joost Jansen, Mapping migration studies: An empirical analysis of the coming of age of a research field, Migration Studies , Volume 8, Issue 3, September 2020, Pages 455–481, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnz031

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Migration studies have developed rapidly as a research field over the past decades. This article provides an empirical analysis not only on the development in volume and the internationalization of the field, but also on the development in terms of topical focus within migration studies over the past three decades. To capture volume, internationalisation, and topic focus, our analysis involves a computer-based topic modelling of the landscape of migration studies. Rather than a linear growth path towards an increasingly diversified and fragmented field, as suggested in the literature, this reveals a more complex path of coming of age of migration studies. Although there seems to be even an accelerated growth for migration studies in terms of volume, its internationalisation proceeds only slowly. Furthermore, our analysis shows that rather than a growth of diversification of topics within migration topic, we see a shift between various topics within the field. Finally, our study shows that there is no consistent trend to more fragmentation in the field; in contrast, it reveals a recent recovery of connectedness between the topics in the field, suggesting an institutionalisation or even theoretical and conceptual coming of age of migration studies.

Migration studies have developed rapidly as a research field in recent decades. It encompasses studies on all types of international and internal migration, migrants, and migration-related diversity ( King, 2002 ; Scholten, 2018 ). Many scholars have observed the increase in the volume of research on migration ( Massey et al., 1998 ; Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Scholten et al., 2015 ). Additionally, the field has become increasingly varied in terms of links to broader disciplines ( King, 2012 ; Brettell and Hollifield, 2014 ) and in terms of different methods used ( Vargas-Silva, 2012 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz, 2018 ). It is now a field that has in many senses ‘come of age’: it has internationalised with scholars involved from many countries; it has institutionalised through a growing number of journals; an increasing number of institutes dedicated to migration studies; and more and more students are pursuing migration-related courses. These trends are also visible in the growing presence of international research networks in the field of migration.

Besides looking at the development of migration in studies in terms of size, interdisciplinarity, internationalisation, and institutionalisation, we focus in this article on the development in topical focus of migration studies. We address the question how has the field of migration studies developed in terms of its topical focuses? What topics have been discussed within migration studies? How has the topical composition of the field changed, both in terms of diversity (versus unity) and connectedness (versus fragmentation)? Here, the focus is not on influential publications, authors, or institutes, but rather on what topics scholars have written about in migration studies. The degree of diversity among and connectedness between these topics, especially in the context of quantitative growth, will provide an empirical indication of whether a ‘field’ of migration studies exists, or to what extent it is fragmented.

Consideration of the development of migration studies invokes several theoretical questions. Various scholars have argued that the growth of migration studies has kept pace not only with the growing prominence of migration itself but also with the growing attention of nation–states in particular towards controlling migration. The coproduction of knowledge between research and policy, some argue ( Scholten, 2011 ), has given migration research an inclination towards paradigmatic closure, especially around specific national perspectives on migration. Wimmer and Glick Schiller (2002 ) speak in this regard of ‘methodological nationalism’, and others refer to the prominence of national models that would be reproduced by scholars and policymakers ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Favell, 2003 ). More generally, this has led, some might argue, to an overconcentration of the field on a narrow number of topics, such as integration and migration control, and a consequent call to ‘de-migranticise’ migration research ( Dahinden, 2016 ; see also Schinkel, 2018 ).

However, recent studies suggest that the growth of migration studies involves a ‘coming of age’ in terms of growing diversity of research within the field. This diversification of migration studies has occurred along the lines of internationalisation ( Scholten et al., 2015 ), disciplinary variation ( Yans-McLaughlin, 1990 ; King, 2012 ; Brettell and Hollifield, 2014 ) and methodological variation ( Vargas-Silva, 2012 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz, 2018 ). The International Organization for Migration ( IOM, 2017 : 95) even concludes that ‘the volume, diversity, and growth of both white and grey literature preclude a [manual] systematic review’ of migration research produced in 2015 and 2016 alone .

Nonetheless, in this article, we attempt to empirically trace the development of migration studies over the past three decades, and seek to find evidence for the claim that the ‘coming of age’ of migration studies indeed involves a broadening of the variety of topics within the field. We pursue an inductive approach to mapping the academic landscape of >30 years of migration studies. This includes a content analysis based on a topic modelling algorithm, applied to publications from migration journals and book series. We trace the changes over time of how the topics are distributed within the corpus and the extent to which they refer to one another. We conclude by giving a first interpretation of the patterns we found in the coming of age of migration studies, which is to set an agenda for further studies of and reflection on the development of this research field. While migration research is certainly not limited to journals and book series that focus specifically on migration, our methods enable us to gain a representative snapshot of what the field looks like, using content from sources that migration researchers regard as relevant.

Migration has always been studied from a variety of disciplines ( Cohen, 1996 ; Brettell and Hollifield, 2014 ), such as economics, sociology, history, and demography ( van Dalen, 2018 ), using a variety of methods ( Vargas-Silva, 2012 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz, 2018 ), and in a number of countries ( Carling, 2015 ), though dominated by Northern Hemisphere scholarship (see, e.g. Piguet et al., 2018 ), especially from North America and Europe ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ). Taking stock of various studies on the development of migration studies, we can define several expectations that we will put to an empirical test.

Ravenstein’s (1885) 11 Laws of Migration is widely regarded as the beginning of scholarly thinking on this topic (see Zolberg, 1989 ; Greenwood and Hunt, 2003 ; Castles and Miller, 2014 ; Nestorowicz and Anacka, 2018 ). Thomas and Znaniecki’s (1918) five-volume study of Polish migrants in Europe and America laid is also noted as an early example of migration research. However, according to Greenwood and Hunt (2003 ), migration research ‘took off’ in the 1930s when Thomas (1938) indexed 191 studies of migration across the USA, UK, and Germany. Most ‘early’ migration research was quantitative (see, e.g. Thornthwaite, 1934 ; Thomas, 1938 ). In addition, from the beginning, migration research developed with two empirical traditions: research on internal migration and research on international migration ( King and Skeldon, 2010 ; Nestorowicz and Anacka, 2018 : 2).

In subsequent decades, studies of migration studies describe a burgeoning field. Pedraza-Bailey (1990) refers to a ‘veritable boom’ of knowledge production by the 1980s. A prominent part of these debates focussed around the concept of assimilation ( Gordon, 1964 ) in the 1950s and 1960s (see also Morawska, 1990 ). By the 1970s, in light of the civil rights movements, researchers were increasingly focussed on race and ethnic relations. However, migration research in this period lacked an interdisciplinary ‘synthesis’ and was likely not well-connected ( Kritz et al., 1981 : 10; Pryor, 1981 ; King, 2012 : 9–11). Through the 1980s, European migration scholarship was ‘catching up’ ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 : 14) with the larger field across the Atlantic. Substantively, research became increasingly mindful of migrant experiences and critical of (national) borders and policies ( Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 : 49). King (2012) also observes this ‘cultural turn’ towards more qualitative anthropological migration research by the beginning of the 1990s, reflective of trends in social sciences more widely ( King, 2012 : 24). In the 1990s, Massey et al. (1993, 1998 ) and Massey (1994) reflected on the state of the academic landscape. Their literature review (1998) notes over 300 articles on immigration in the USA, and over 150 European publications. Despite growth, they note that the field did not develop as coherently in Europe at it had done in North America (1998: 122).

We therefore expect to see a significant growth of the field during the 1980s and 1990s, and more fragmentation, with a prominence of topics related to culture and borders.

At the turn of the millennium, Portes (1997) lists what were, in his view, the five key themes in (international) migration research: 1 transnational communities; 2 the new second generation; 3 households and gender; 4 states and state systems; and 5 cross-national comparisons. This came a year after Cohen’s review of Theories of Migration (1996), which classifies nine key thematic ‘dyads’ in migration studies, such as internal versus international migration; individual versus contextual reasons to migrate; temporary versus permanent migration; and push versus pull factors (see full list in Cohen, 1996 : 12–15). However, despite increasing knowledge production, Portes argues that the problem in these years was the opposite of what Kritz et al. (1981) observe above; scholars had access to and generated increasing amounts of data, but failed to achieve ‘conceptual breakthrough’ ( Portes, 1997 : 801), again suggesting fragmentation in the field.

Thus, in late 1990s and early 2000s scholarship we expect to find a prominence of topics related to these five themes, and a limited number of “new” topics.

In the 21st century, studies of migration studies indicate that there has been a re-orientation away from ‘states and state systems’. This is exemplified by Wimmer and Glick Schiller’s (2002) widely cited commentary on ‘methodological nationalism’, and the alleged naturalisation of nation-state societies in migration research (see Thranhardt and Bommes, 2010 ), leading to an apparent pre-occupation with the integration paradigm since the 1980s according to Favell (2003) and others ( Dahinden, 2016 ; Schinkel, 2018 ). This debate is picked up in Bommes and Morawska’s (2005) edited volume, and Lavenex (2005) . Describing this shift, Geddes (2005) , in the same volume, observes a trend of ‘Europeanised’ knowledge production, stimulated by the research framework programmes of the EU. Meanwhile, on this topic, others highlight a ‘local turn’ in migration and diversity research ( Caponio and Borkert, 2010 ; Zapata-Barrero et al., 2017) .

In this light, we expect to observe a growth in references to European (and other supra-national) level and local-level topics in the 21t century compared to before 2000.

As well as the ‘cultural turn’ mentioned above, King (2012 : 24–25) observes a re-inscription of migration within wider social phenomena—in terms of changes to the constitutive elements of host (and sending) societies—as a key development in recent migration scholarship. Furthermore, transnationalism, in his view, continues to dominate scholarship, though this dominance is disproportionate, he argues, to empirical reality. According to Scholten (2018) , migration research has indeed become more complex as the century has progressed. While the field has continued to grow and institutionalise thanks to networks like International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe (IMISCOE) and Network of Migration Research on Africa (NOMRA), this has been in a context of apparently increasing ‘fragmentation’ observed by several scholars for many years (see Massey et al., 1998 : 17; Penninx et al., 2008 : 8; Martiniello, 2013 ; Scholten et al., 2015 : 331–335).

On this basis, we expect a complex picture to emerge for recent scholarship, with thematic references to multiple social phenomena, and a high level of diversity within the topic composition of the field. We furthermore expect increased fragmentation within migration studies in recent years.

The key expectation of this article is, therefore, that the recent topical composition of migration studies displays greater diversity than in previous decades as the field has grown. Following that logic, we hypothesise that with diversification (increasingly varied topical focuses), fragmentation (decreasing connections between topics) has also occurred.

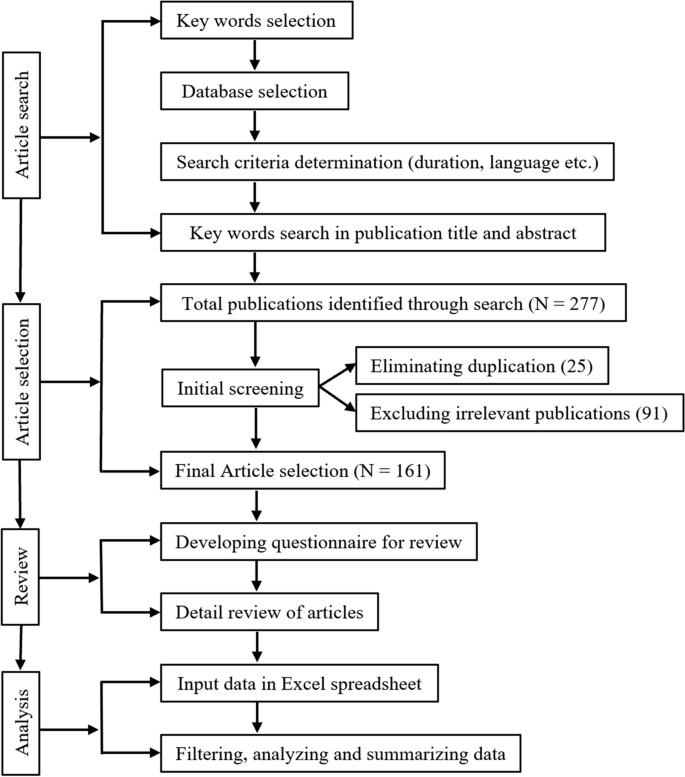

The empirical analysis of the development in volume and topic composition of migration studies is based on the quantitative methods of bibliometrics and topic modelling. Although bibliometric analysis has not been widely used in the field of migration (for some exceptions, see Carling, 2015 ; Nestorowicz and Anacka, 2018 ; Piguet et al., 2018 ; Sweileh et al., 2018 ; van Dalen, 2018 ), this type of research is increasingly popular ( Fortunato et al., 2018 ). A bibliometric analysis can help map what Kajikawa et al. (2007) call an ‘academic landscape’. Our analysis pursues a similar objective for the field of migration studies. However, rather than using citations and authors to guide our analysis, we extract a model of latent topics from the contents of abstracts . In other words, we are focussed on the landscape of content rather than influence.

3.1 Topic modelling

Topic modelling involves a computer-based strategy for identifying topics or topic clusters that figure centrally in a specific textual landscape (e.g. Jiang et al., 2016 ). This is a class of unsupervised machine learning techniques ( Evans and Aceves, 2016 : 22), which are used to inductively explore and discover patterns and regularities within a corpus of texts. Among the most widely used topic models is Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). LDA is a type of Bayesian probabilistic model that builds on the assumption that each document in a corpus discusses multiple topics in differing proportions. Therefore, Document A might primarily be about Topic 1 (60 per cent), but it also refers to terms associated with Topic 2 (30 per cent), and, to a lesser extent, Topic 3 (10 per cent). A topic, then, is defined as a probability distribution over a fixed vocabulary, that is, the totality of words present in the corpus. The advantage of the unsupervised LDA approach that we take is that it does not limit the topic model to our preconceptions of which topics are studied by migration researchers and therefore should be found in the literature. Instead, it allows for an inductive sketching of the field, and consequently an element of surprise ( Halford and Savage, 2017 : 1141–1142). To determine the optimal number of topics, we used the package ldatuning to calculate the statistically optimal number of topics, a number which we then qualitatively validated.

The chosen LDA model produced two main outcomes. First, it yielded a matrix with per-document topic proportions, which allow us to generate an idea of the topics discussed in the abstracts. Secondly, the model returned a matrix with per-topic word probabilities. Essentially, the topics are a collection of words ordered by their probability of (co-)occurrence. Each topic contains all the words from all the abstracts, but some words have a much higher likelihood to belong to the identified topic. The 20–30 most probable words for each topic can be helpful in understanding the content of the topic. The third step we undertook was to look at those most probable words by a group of experts familiar with the field and label them. We did this systematically and individually by first looking at the top 5 words, then the top 30, trying to find an umbrella label that would summarize the topic. The initial labels suggested by each of us were then compared and negotiated in a group discussion. To verify the labels even more, in case of a doubt, we read several selected abstracts marked by the algorithm as exhibiting a topic, and through this were able to further refine the names of the topics.

It is important to remember that this list of topics should not be considered a theoretically driven attempt to categorize the field. It is purely inductive because the algorithm is unable to understand theories, conceptual frames, and approaches; it makes a judgement only on the basis of words. So if words are often mentioned together, the computer regards their probability of belonging to one topic as high.

3.2 Dataset of publications

For the topic modelling, we created a dataset that is representative of publications relevant to migration studies. First, we identified the most relevant sources of literature. Here we chose not only to follow rankings in citation indices, but also to ask migration scholars, in an expert survey, to identify what they considered to be relevant sources. This survey was distributed among a group of senior scholars associated with the IMISCOE Network; 25 scholars anonymously completed the survey. A set of journals and book series was identified from existing indices (such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus) which were then validated and added to by respondents. Included in our eventual dataset were all journals and book series that were mentioned at least by two experts in the survey. The dataset includes 40 journals and 4 book series (see Supplementary Data A). Non-English journals were omitted from data collection because the algorithm can only analyse one language. Despite their influence on the field, we also did not consider broader disciplinary journals (for instance, sociological journals or economic journals) for the dataset. Such journals, we acknowledge, have published some of the most important research in the history of migration studies, but even with their omission, it is still possible to achieve our goal of obtaining a representative snapshot of what migration researchers have studied, rather than who or which papers have been most influential. In addition, both because of the language restriction of the algorithm and because of the Global North’s dominance in the field that is mentioned above ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Piguet et al., 2018 ), there is likely to be an under-representation of scholarship from the Global South in our dataset.

Secondly, we gathered metadata on publications from the selected journals and book series using the Scopus and Web of Science electronic catalogues, and manually collecting from those sources available on neither Scopus nor Web of Science. The metadata included authors, years, titles, and abstracts. We collected all available data up to the end of 2017. In total, 94 per cent of our metadata originated from Scopus, ∼1 per cent from Web of Science, and 5 per cent was gathered manually. One limitation of our dataset lies in the fact that the electronic catalogue of Scopus, unfortunately, does not list all articles and abstracts ever published by all the journals (their policy is to collect articles and abstracts ‘where available’ ( Elsevier, 2017 )). There was no technical possibility of assessing Scopus or WoS’ proportional coverage of all articles actually published. The only way to improve the dataset in this regard would be to manually collect and count abstracts from journal websites. This is also why many relevant books were not included in our dataset; they are not indexed in such repositories.

In the earliest years of available data, only a few journals were publishing (with limited coverage of this on Scopus) specifically on migration. However, Fig. 1 below demonstrates that the numbers constantly grew between 1959 and 2018. As Fig. 1 shows, in the first 30 years (1959–88), the number of migration journals increased by 15, while in the following three decades (1989–2018), this growth intensified as the number of journals tripled to 45 in the survey (see Supplementary Data A for abbreviations).

Number of journals focussed on migration and migration-related diversity (1959–2018) Source: Own calculations.

Within all 40 journals in the dataset, we were able to access and extract for our analysis 29,844 articles, of which 22,140 contained abstracts. Furthermore, we collected 901 available abstracts of chapters in the 4 book series: 2 series were downloaded from the Scopus index (Immigration and Asylum Law in Europe; Handbook of the Economics of International Migration), and the abstracts of the other 2 series, selected from our expert survey (the IMISCOE Research Series Migration Diasporas and Citizenship), were collected manually. Given the necessity of manually collecting the metadata for 896 abstracts of the chapters in these series, it was both practical and logical to set these two series as the cut-off point. Ultimately, we get a better picture of the academic landscape as a whole with some expert-approved book series than with none .

Despite the limitations of access, we can still have an approximate idea on how the volume of publications changed overtime. The chart ( Fig. 2 ) below shows that both the number of published articles and the number of abstracts of these articles follow the same trend—a rapid growth after the turn of the century. In 2017, there were three times more articles published per year than in 2000.

Publications and abstracts in the dataset (1959–2018).

The cumulative graph ( Fig. 3 ) below shows the total numbers of publications and the available abstracts. For the creation of our inductively driven topic model, we used all available abstracts in the entire timeframe. However, to evaluate the dynamics of topics over time, we decided to limit the timeframe of our chronological analyses to 1986–2017, because as of 1986, there were more than 10 active journals and more articles had abstracts. This analysis therefore covers the topical evolution of migration studies in the past three decades.

Cumulative total of publications and abstracts (1959–2017).

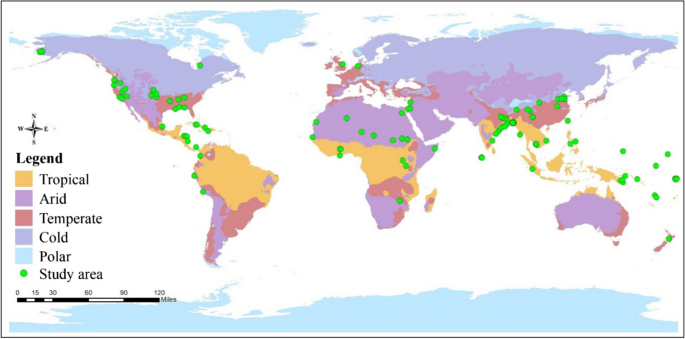

Migration studies has only internationalised very slowly in support of what others have previously argued ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Piguet et al., 2018 ). Figure 4 gives a snapshot of the geographic dispersion of the articles (including those without abstracts) that we collected from Scopus. Where available, we extracted the country of authors’ university affiliations. The colour shades represent the per capita publication volume. English-language migration scholarship has been dominated by researchers based, unsurprisingly, in Anglophone and Northern European countries.

Migration research output per capita (based on available affiliation data within dataset).

The topic modelling (following the LDA model) led us, as discussed in methods, to the definition of 60 as the optimal number of topics for mapping migration studies. Each topic is a string of words that, according to the LDA algorithm, belong together. We reviewed the top 30 words for each word string and assigned labels that encapsulated their meaning. Two of the 60 word strings were too generic and did not describe anything related to migration studies; therefore, we excluded them. Subsequently, the remaining 58 topics were organised into a number of clusters. In the Table 1 below, you can see all the topic labels, the topic clusters they are grouped into and the first 5 (out of 30) most probable words defining those topics.

Topics in migration studies

After presenting all the observed topics in the corpus of our publication data, we examined which topics and topic clusters are most frequent in general (between 1964 and 2017), and how their prominence has been changing over the years. On the basis of the matrix of per-item topic proportions generated by LDA analysis, we calculated the shares of each topic in the whole corpus. On the level of individual topics, around 25 per cent of all abstract texts is about the top 10 most prominent topics, which you can see in Fig. 5 below. Among those, #56 identity narratives (migration-related diversity), #39 migration theory, and #29 migration flows are the three most frequently detected topics.

Top 10 topics in the whole corpus of abstracts.

On the level of topic clusters, Fig. 6 (left) shows that migration-related diversity (26 per cent) and migration processes (19 per cent) clearly comprise the two largest clusters in terms of volume, also because they have the largest number topics belonging to them. However, due to our methodology of labelling these topics and grouping them into clusters, it is complicated to make comparisons between topic clusters in terms of relative size, because some clusters simply contain more topics. Calculating average proportions of topics within each cluster allows us to control for the number of topics per cluster, and with this measure, we can better compare the relative prominence of clusters. Figure 6 (right) shows that migration research and statistics have the highest average of topic proportions, followed by the cluster of migration processes and immigrant incorporation.

Topic proportions per cluster.

An analysis on the level of topic clusters in the project’s time frame (1986–2017) reveals several significant trends. First, when discussing shifts in topics over time, we can see that different topics have received more focus in different time frames. Figure 7 shows the ‘age’ of topics, calculated as average years weighted by proportions of publications within a topic per year. The average year of the articles on the same topic is a proxy for the age of the topic. This gives us an understanding of which topics were studied more often compared with others in the past and which topics are emerging. Thus, an average year can be understood as the ‘high-point’ of a topic’s relative prominence in the field. For instance, the oldest topics in our dataset are #22 ‘Migrant demographics’, followed by #45 ‘Governance of migration’ and #46 ‘Migration statistics and survey research’. The newest topics include #14 ‘Mobilities’ and #48 ‘Intra-EU mobility’.

Average topic age, weighted by proportions of publications (publications of 1986–2017). Note: Numbers near dots indicate the numeric id of topics (see Table 1 for the names).

When looking at the weighted ‘age’ of the clusters, it becomes clear that the focus on migration research and statistics is the ‘oldest’, which echoes what Greenwood and Hunt (2003 ) observe. This resonates with the idea that migration studies has roots in more demographic studies of migration and diversity (cf. Thornthwaite, 1934 ; Thomas, 1938 ), which somewhat contrasts with what van Dalen (2018) has found. Geographies of migration (studies related to specific migration flows, origins, and destinations) were also more prominent in the 1990s than now, and immigrant incorporation peaked at the turn of the century. However, gender and family, diversity, and health are more recent themes, as was mentioned above (see Fig. 8 ). This somewhat indicates a possible post-methodological nationalism, post-integration paradigm era in migration research going hand-in-hand with research that, as King (2012) argues, situates migration within wider social and political domains (cf. Scholten, 2018 ).

Diversity of topics and topic clusters (1985–2017).

Then, we analysed the diversification of publications over the various clusters. Based on the literature review, we expected the diversification to have increased over the years, signalling a move beyond paradigmatic closure. Figure 9 (below) shows that we can hardly speak of a significant increase of diversity in migration studies publications. Over the years, only a marginal increase in the diversity of topics is observed. The Gini-Simpson index of diversity in 1985 was around 0.95 and increased to 0.98 from 1997 onwards. Similarly, there is little difference between the sizes of topic clusters over the years. Both ways of calculating the Gini-Simpson index of diversity by clusters resulted in a rather stable picture showing some fluctuations between 0.82 and 0.86. This indicates that there has never been a clear hegemony of any cluster at any time. In other words, over the past three decades, the diversity of topics and topic clusters was quite stable: there have always been a great variety of topics discussed in the literature of migration studies, with no topic or cluster holding a clear monopoly.

Average age of topic clusters, weighted by proportions (publications of 1986–2017).

Subsequently, we focussed on trends in topic networks. As our goal is to describe the general development of migration studies as a field, we decided to analyse topic networks in three equal periods of 10 years (Period 1 (1988–97); Period 2 (1998–2007); Period 3 (2008–17)). On the basis of the LDA-generated matrix with per-abstract topic proportions (The LDA algorithm determines the proportions of all topics observed within each abstract. Therefore, each abstract can contain several topics with a substantial prominence), we calculated the topic-by-topic Spearman correlation coefficients in each of the time frames. From the received distribution of the correlation coefficients, we chose to focus on the top 25 per cent strongest correlations period. In order to highlight difference in strength of connections, we assigned different weights to the correlations between the topics. Coefficient values above the 75th percentile (0.438) but ≤0.5 were weighted 1; correlations above 0.5 but ≤0.6 were weighted 2; and correlations >0.6 were weighted 3. We visualised these topic networks using the software Gephi.

To compare networks of topics in each period, we used three common statistics of network analysis: 1 average degree of connections; 2 average weighted degree of connections; and 3 network density. The average degree of connections shows how many connections to other topics each topic in the network has on average. This measure can vary from 0 to N − 1, where N is the total number of topics in the network. Some correlations of topics are stronger and were assigned the Weight 2 or 3. These are included in the statistics of average weighted degree of connections, which shows us the variations in strength of existing connections between the topics. Network density is a proportion of existing links over the number of all potentially possible links between the topics. This measure varies from 0 = entirely disconnected topics to 1 = extremely dense network, where every topic is connected to every topic.

Table 2 shows that all network measures vary across the three periods. In Period 1, each topic had on average 21 links with other topics, while in Period 2, that number was much lower (11.5 links). In Period 3, the average degree of connections grew again, but not to the level of Period 1. The same trend is observed in the strength of these links—in Period 1, the correlations between the topics were stronger than in Period 3, while they were the weakest in Period 2. The density of the topic networks was highest in Period 1 (0.4), then in Period 2, the topic network became sparser before densifying again in Period 3 (but not to the extent of Period 1’s density).

Topic network statistics

These fluctuations on network statistics indicate that in the years 1988–97, topics within the analysed field of migration studies were mentioned in the same articles and book chapters more often, while at the turn of the 21st century, these topic co-occurrences became less frequent; publications therefore became more specialised and topics were more isolated from each other. In the past 10 years, migration studies once again became more connected, the dialogues between the topics emerged more frequently. These are important observations about topical development in the field of migration studies. The reasons behind these changes require further, possibly more qualitative explanation.

To get a more in-depth view of the content of these topic networks, we made an overview of the changes in the topic clusters across the three periods. As we can see in Fig. 10 , some changes emerge in terms of the prominence of various clusters. The two largest clusters (also by the number of topics within them) are migration-related diversity and migration processes. The cluster of migration-related diversity increased in its share of each period’s publications by around 20 per cent. This reflects our above remarks on the literature surrounding the integration debate, and the ‘cultural turn’ King mentions (2012). And the topic cluster migration processes also increased moderately its share.

Prominence and change in topic clusters 1988–2017.

Compared with the first period, the topic cluster of gender and family studies grew the fastest, with the largest growth observed in the turn of the century (relative to its original size). This suggests a growing awareness of gender and family-related aspects of migration although as a percentage of the total corpus it remains one the smallest clusters. Therefore, Massey et al.’s (1998) argument that households and gender represented a quantitatively significant pillar of migration research could be considered an overestimation. The cluster of health studies in migration research also grew significantly in the Period 2 although in Period 3, the percentage of publications in this cluster diminished. This suggests a rising awareness of health in relation to migration and diversity (see Sweileh et al., 2018 ) although this too remains one of the smallest clusters.

The cluster on Immigrant incorporation lost prominence the most over the past 30 years. This seems to resonate with the argument that ‘integrationism’ or the ‘integration paradigm’ was rather in the late 1990s (see Favell, 2003 ; Dahinden, 2016 ) and is losing its prominence. A somewhat slower but steady loss was also observed in the cluster of Geographies of migration and Migration research and statistics. This also suggests not only a decreasing emphasis on demographics within migration studies, but also a decreasing reflexivity in the development of the field and the focus on theory-building.

We will now go into more detail and show the most connected topics and top 10 most prominent topics in each period. Figures 11–13 show the network maps of topics in each period. The size of circles reflects the number and strength of links per each topic: the bigger the size, the more connected this topic is to the others; the biggest circles indicate the most connected topics. While the prominence of a topic is measured by the number of publications on that topic, it is important to note that the connectedness the topic has nothing necessarily to do with the amount of publications on that topic; in theory, a topic could appear in many articles without any reference to other topics (which would mean that it is prominent but isolated).

Topic network in 1988–97. Note: Numbers indicate topics' numerical ids, see Table 1 for topics' names.

Topic network in 1998–2007. Note: Numbers indicate topics' numerical ids, see Table 1 for topics' names.

Topic network in 2008–2017. Note: Numbers indicate topics' numerical ids, see Table 1 for topics' names.

Thus, in the section below, we describe the most connected and most prominent topics in migration research per period. The degree of connectedness is a useful indicator of the extent to which we can speak of a ‘field’ of migration research. If topics are well-connected, especially in a context of increased knowledge production and changes in prominence among topics, then this would suggest that a shared conceptual and theoretical language exists.

6.1 Period 1: 1988–97

The five central topics with the highest degree of connectedness (the weighted degree of connectedness of these topics was above 60) were ‘black studies’, ‘mobilities’, ‘ICT, media and migration’, ‘migration in/from Israel and Palestine’, and ‘intra-EU mobility’. These topics are related to geopolitical regions, ethnicity, and race. The high degree of connectedness of these topics shows that ‘they often occurred together with other topics in the analysed abstracts from this period’. This is expected because research on migration and diversity inevitably discusses its subject within a certain geographical, political, or ethnic scope. Geographies usually appear in abstracts as countries of migrants’ origin or destination. The prominence of ‘black studies’ reflects the dominance of American research on diversity, which was most pronounced in this period ( Fig. 11 ).

The high degree of connectedness of the topics on ICT and ‘media’ is indicative of wider societal trends in the 1990s. As with any new phenomenon, it clearly attracted the attention of researchers who wanted to understand its relationship with migration issues.

Among the top 10 topics with the most publications in this period (see Supplementary Data B) were those describing the characteristics of migration flows (first) and migration populations (third). It goes in line with the trends of the most connected topics described above. Interest in questions of migrants’ socio-economic position (fourth) in the receiving societies and discussion on ‘labour migration’ (ninth) were also prevalent. Jointly, these topics confirm that in the earlier years, migration was ‘studied often from the perspectives of economics and demographics’ ( van Dalen, 2018 ).

Topics, such as ‘education and language training’ (second), community development’ (sixth), and ‘intercultural communication’ (eighth), point at scholarly interest in the issues of social cohesion and socio-cultural integration of migrants. This lends strong support to Favell’s ‘integration paradigm’ argument about this period and suggests that the coproduction of knowledge between research and policy was indeed very strong ( Scholten, 2011 ). This is further supported by the prominence of the topic ‘governance of migration’ (seventh), reflecting the evolution of migration and integration policymaking in the late 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, exemplified by the development of the Schengen area and the EU more widely; governance of refugee flows from the Balkan region (also somewhat represented in the topic ‘southern-European migration’, which was the 10th most prominent); and governance of post-Soviet migration. Interestingly, this is the only period in which ‘migration histories’ is among the top 10 topics, despite the later establishment of a journal dedicated to the very discipline of history. Together these topics account for 42 per cent of all migration studies publications in that period of time.

6.2 Period 2: 1998–2007

In the second period, as the general degree of connectedness in the topic networks decreased, the following five topics maintained a large number of connections in comparison to others, as their average weighted degree of connections ranged between 36 and 57 ties. The five topics were ‘migration in/from Israel and Palestine’, ‘black studies’, ‘Asian migration’, ‘religious diversity’, and ‘migration, sexuality, and health’ ( Fig. 12 ).

Here we can observe the same geographical focus of the most connected topics, as well as the new trends in the migration research. ‘Asian migration’ became one of the most connected topics, meaning that migration from/to and within that region provoked more interest of migration scholars than in the previous decade. This development appears to be in relation to high-skill migration, in one sense, because of its strong connections with the topics ‘Asian expat migration’ and ‘ICT, media, and migration’; and, in another sense, in relation to the growing Muslim population in Europe thanks to its strong connection to ‘religious diversity’. The high connectedness of the topic ‘migration sexuality and health’ can be explained by the dramatic rise of the volume of publications within the clusters ‘gender and family’ studies and ‘health’ in this time-frame as shown in the charts on page 13, and already argued by Portes (1997) .

In this period, ‘identity narratives’ became the most prominent topic (see Supplementary Data B), which suggests increased scholarly attention on the subjective experiences of migrants. Meanwhile ‘migrant flows’ and ‘migrant demographics’ decreased in prominence from the top 3 to the sixth and eighth position, respectively. The issues of education and socio-economic position remained prominent. The emergence of topics ‘migration and diversity in (higher) education’ (fifth) and ‘cultural diversity’ (seventh) in the top 10 of this period seem to reflect a shift from integrationism to studies of diversity. The simultaneous rise of ‘migration theory’ (to fourth) possibly illustrates the debates on methodological nationalism which emerged in the early 2000s. The combination of theoretical maturity and the intensified growth in the number of migration journals at the turn of the century suggests that the field was becoming institutionalised.

Overall, the changes in the top 10 most prominent topics seem to show a shifting attention from ‘who’ and ‘what’ questions to ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions. Moreover, the top 10 topics now account only for 26 per cent of all migration studies (a 15 per cent decrease compared with the period before). This means that there were many more topics which were nearly as prominent as those in the top 10. Such change again supports our claim that in this period, there were more intensive ‘sub-field’ developments in migration studies than in the previous period.

6.3 Period 3: 2008–17

In the last decade, the most connected topics have continued to be: ‘migration in/from Israel and Palestine’, ‘Asian migration’, and ‘black studies’. The hypothetical reasons for their central position in the network of topics are the same as in the previous period. The new most-connected topics—‘Conflicts, violence, and migration’, together with the topic ‘Religious diversity’—might indicate to a certain extent the widespread interest in the ‘refugee crisis’ of recent years ( Fig. 13 ).

The publications on the top 10 most prominent topics constituted a third of all migration literature of this period analysed in our study. A closer look at them reveals the following trends (see Supplementary Data B for details). ‘Mobilities’ is the topic of the highest prominence in this period. Together with ‘diasporas and transnationalism’ (fourth), this reflects the rise of critical thinking on methodological nationalism ( Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2002 ) and the continued prominence of transnationalism in the post-‘mobility turn’ era ( Urry (2007) , cited in King, 2012 ).

The interest in subjective experiences of migration and diversity has continued, as ‘identity narratives’ continues to be prominent, with the second highest proportion of publications, and as ‘Discrimination and socio-psychological issues’ have become the eighth most prominent topic. This also echoes an increasing interest in the intersection of (mental) health and migration (cf. Sweileh et al., 2018 ).

The prominence of the topics ‘human rights law and protection’ (10th) and ‘governance of migration and diversity’ (9th), together with ‘conflicts, violence, and migration’ being one of the most connected topics, could be seen as a reflection of the academic interest in forced migration and asylum. Finally, in this period, the topics ‘race and racism’ (fifth) and ‘black studies’ (seventh) made it into the top 10. Since ‘black studies’ is also one of the most connected topics, such developments may reflect the growing attention to structural and inter-personal racism not only in the USA, perhaps reflecting the #blacklivesmatter movement, as well as in Europe, where the idea of ‘white Europeanness’ has featured in much public discourse.

6.4 Some hypotheses for further research

Why does the connectedness of topics change across three periods? In an attempt to explain these changes, we took a closer look at the geographical distribution of publications in each period. One of the trends that may at least partially explain the loss of connectedness between the topics in Period 2 could be related to the growing internationalisation of English language academic literature linked to a sharp increase in migration-focussed publications during the 1990s.

Internationalisation can be observed in two ways. First, the geographies of English language journal publications have become more diverse over the years. In the period 1988–97, the authors’ institutional affiliations spanned 57 countries. This increased to 72 in 1998–2007, and then to 100 in 2007–18 (we counted only those countries which contained at least 2 publications in our dataset). Alongside this, even though developed Anglophone countries (the USA, Canada, Australia, the UK, Ireland, and New Zealand) account for the majority of publications of our overall dataset, the share of publications originating from non-Anglophone countries has increased over time. In 1988–97, the number of publications from non-Anglophone European (EU+EEA) countries was around 13 per cent. By 2008–17, this had significantly increased to 28 per cent. Additionally, in the rest of the world, we observe a slight proportional increase from 9.5 per cent in the first period to 10.6 per cent in the last decade. Developed Anglophone countries witness a 16 per cent decrease in their share of all articles on migration. The trends of internationalisation illustrated above, combined with the loss of connectedness at the turn of the 21st century, seem to indicate that English became the lingua-franca for academic research on migration in a rather organic manner.

It is possible that a new inflow of ideas came from the increased number of countries publishing on migration whose native language is not English. This rise in ‘competition’ might also have catalysed innovation in the schools that had longer established centres for migration studies. Evidence for this lies in the rise in prominence of the topic ‘migration theory’ during this period. It is also possible that the expansion of the European Union and its research framework programmes, as well as the Erasmus Programmes and Erasmus Mundus, have perhaps brought novel, comparative, perspectives in the field. All this together might have created fruitful soil for developing unique themes and approaches, since such approaches in theory lead to more success and, crucially, more funds for research institutions.

This, however, cannot fully explain why in Period 3 the field became more connected again, other than that the framework programmes—in particular framework programme 8, Horizon 2020—encourage the building of scientific bridges, so to speak. Our hypothesis is thus that after the burst of publications and ideas in Period 2, scholars began trying to connect these new themes and topics to each other through emergent international networks and projects. Perhaps even the creation and work of the IMISCOE (2004-) and NOMRA (1998-) networks contributed to this process of institutionalisation. This, however, requires much further thought and exploration, but for now, we know that the relationship between the growth, the diversification, and the connectedness in this emergent research field is less straightforward than we might previously have suggested. This begs for further investigation perhaps within a sociology of science framework.

This article offers an inductive mapping of the topical focus of migration studies over a period of more than 30 years of development of the research field. Based on the literature, we expected to observe increasing diversity of topics within the field and increasing fragmentation between the topics, also in relation to the rapid growth in volume and internationalisation of publications in migration studies. However, rather than growth and increased diversity leading to increased fragmentation, our analysis reveals a complex picture of a rapidly growing field where the diversity of topics has remained relatively stable. Also, even as the field has internationalised, it has retained its overall connectedness, albeit with a slight and temporary fragmentation at the turn of the century. In this sense, we can argue that migration studies have indeed come of age as a distinct research field.

In terms of the volume of the field of migration studies, our study reveals an exponential growth trajectory, especially since the mid-1990s. This involves both the number of outlets and the number of publications therein. There also seems to be a consistent path to internationalisation of the field, with scholars from an increasing number of countries publishing on migration, and a somewhat shrinking share of publications from Anglo-American countries. However, our analysis shows that this has not provoked an increased diversity of topics in the field. Instead, the data showed that there have been several important shifts in terms of which topics have been most prominent in migration studies. The field has moved from focusing on issues of demographics, statistics, and governance, to an increasing focus on mobilities, migration-related diversity, gender, and health. Also, interest in specific geographies of migration seems to have decreased.

These shifts partially resonated with the expectations derived from the literature. In the 1980s and 1990s, we observed the expected widespread interest in culture, seen in publications dealing primarily with ‘education and language training’, ‘community development’, and ‘intercultural communication’. This continued to be the case at the turn of the century, where ‘identity narratives’ and ‘cultural diversity’ became prominent. The expected focus on borders in the periods ( Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 ) was represented by the high proportion of research on the ‘governance of migration’, ‘migration flows’, and in the highly connected topic ‘intra-EU mobility’. Following Portes (1997) , we expected ‘transnational communities’, ‘states and state systems’, and the ‘new second generation’ to be key themes for the ‘new century’. Transnationalism shifts attention away from geographies of migration and nation–states, and indeed, our study shows that ‘geographies of migration’ gave way to ‘mobilities’, the most prominent topic in the last decade. This trend is supported by the focus on ‘diasporas and transnationalism’ and ‘identity narratives’ since the 2000s, including literature on migrants’ and their descendants’ dual identities. These developments indicate a paradigmatic shift in migration studies, possibly caused by criticism of methodological nationalism. Moreover, our data show that themes of families and gender have been discussed more in the 21st century, which is in line with Portes’ predictions.

The transition from geographies to mobilities and from the governance of migration to the governance of migration-related diversity, race and racism, discrimination, and social–psychological issues indicates a shifting attention in migration studies from questions of ‘who’ and ‘what’ towards ‘how’ and ‘why’. In other words, a more nuanced understanding of the complexity of migration processes and consequences emerges, with greater consideration of both the global and the individual levels of analysis.

However, this complexification has not led to thematic fragmentation in the long run. We did not find a linear trend towards more fragmentation, meaning that migration studies have continued to be a field. After an initial period of high connectedness of research mainly coming from America and the UK, there was a period with significantly fewer connections within migration studies (1998–2007), followed by a recovery of connectedness since then, while internationalisation has continued. What does this tell us?

We may hypothesise that the young age of the field and the tendency towards methodological nationalism may have contributed to more connectedness in the early days of migration studies. The accelerated growth and internationalisation of the field since the late 1990s may have come with an initial phase of slight fragmentation. The increased share of publications from outside the USA may have caused this, as according to Massey et al. (1998) , European migration research was then more conceptually dispersed than across the Atlantic. The recent recovery of connectedness could then be hypothesised as an indicator of the field’s institutionalisation, especially at the European level, and growing conceptual and theoretical development. As ‘wisdom comes with age’, this may be an indication of the ‘coming of age’ of migration studies as a field with a shared conceptual and theoretical foundation.

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, as well as dr. J.F. Alvarado for his advice in the early stages of work on this article.

This research is associated with the CrossMigration project, funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the grant agreement Ares(2017) 5627812-770121.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

Bommes M. , Morawska E. ( 2005 ) International Migration Research: Constructions, Omissions and the Promises of Interdisciplinarity . Aldershot : Ashgate .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Brettell C. B. , Hollifield J. F. ( 2014 ) Migration Theory: Talking across Disciplines . London : Routledge .

Caponio T. , Borkert M. ( 2010 ) The Local Dimension of Migration Policymaking . Amsterdam : Amsterdam University Press .

Carling J. ( 2015 ) Who Is Who in Migration Studies: 107 Names Worth Knowing < https://jorgencarling.org/2015/06/01/who-is-who-in-migration-studies-108-names-worth-knowing/#_Toc420761452 > accessed 1 Jun 2015.

Castles S. , Miller M. J. ( 2014 ) The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World , 5th edn. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

Cohen R. ( 1996 ) Theories of Migration . Cheltenham : Edward Elgar .

Dahinden J. ( 2016 ) ‘A Plea for the “De-migranticization” of Research on Migration and Integration,’ Ethnic and Racial Studies , 39 / 13 : 2207 – 25 .

Elsevier ( 2017 ) Scopus: Content Coverage Guide . < https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/69451/0597-Scopus-Content-Coverage-Guide-US-LETTER-v4-HI-singles-no-ticks.pdf > accessed 18 Dec 2018.

Evans J. A. , Aceves P. ( 2016 ) ‘Machine Translation: Mining Text for Social Theory,’ Annual Review of Sociology’ , 42 / 1 : 21 – 50 .

Favell A. ( 2003 ) ‘Integration Nations: The Nation-State and Research on Immigrants in Western Europe’, in Brochmann G. , ed. The Multicultural Challenge , pp. 13 – 42 . Bingley : Emerald .

Fortunato S. , et al. ( 2018 ) ‘Science of Science’ , Science , 359 / 6379 : 1 – 7 .

Geddes A. ( 2005 ) ‘Migration Research and European Integration: The Construction and Institutionalization of Problems of Europe’, in Bommes M. , Morawska E. (eds). International Migration Research: Constructions, Omissions and the Promises of Interdisciplinarity , pp. 265 – 280 . Aldershot : Ashgate .

Gordon M. ( 1964 ) Assimilation in American Life . New York : Oxford University Press .

Greenwood M. J. , Hunt G. L. ( 2003 ) ‘The Early History of Migration Research,’ International Regional Sciences Review , 26 / 1 : 3 – 37 .

Halford S. , Savage M. ( 2017 ) ‘Speaking Sociologically with Big Data: Symphonic Social Science and the Future for Big Data Research,’ Sociology , 51 / 6 : 1132 – 48 .

IOM ( 2017 ) ‘Migration Research and Analysis: Growth, Reach and Recent Contributions’, in IOM, World Migration Report 2018 , pp. 95 – 121 . Geneva : International Organization for Migration .

Jiang H. , Qiang M. , Lin P. ( 2016 ) ‘A Topic Modeling Based Bibliometric Exploratoin of Hydropower Research,’ Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews , 57 : 226 – 37 .

Kajikawa Y. , et al. ( 2007 ) ‘Creating an Academic Landscape of Sustainability Science: An Analysis of the Citation Network,’ Sustainability Science , 2 / 2 : 221 – 31 .

King R. , Skeldon R. ( 2010 ) ‘Mind the Gap: Integrating Approaches to Internal and International Migration,’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 36 / 10 : 1619 – 46 .

King R. , Skeldon R. ( 2002 ) ‘Towards a New Map of European Migration,’ International Journal of Population Geography , 8 / 2 : 89 – 106 .

King R. , Skeldon R. ( 2012 ) Theories and Typologies of Migration: An Overview and a Primer . Malmö : Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM ).

Kritz M. M. , Keely C. B. , Tomasi S. M. ( 1981 ) Global Trends in Migration: Theory and Research on International Population Movements . New York : The Centre for Migration Studies .

Lavenex S. ( 2005 ) ‘National Frames in Migration Research: The Tacit Political Agenda’, in Bommes M. , Morawska E. (eds) International Migration Research: Constructions, Omissions and the Promises of Interdisciplinarity , pp. 243 – 263 . Aldershot : Ashgate .

Martiniello M. ( 2013 ) ‘Comparisons in Migration Studies,’ Comparative Migration Studies , 1 / 1 : 7 – 22 .

Massey D. S. , et al. ( 1993 ) ‘Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal,’ Population and Development Review , 19 / 3 : 431 – 66 .

Massey D. S. ( 1994 ) ‘An Evaluation of International Migration Theory: The North American Case,’ Population and Development Review , 20 / 4 : 699 – 751 .

Massey D. S. , et al. ( 1998 ) Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium . Oxford : Clarendon .

Morawska E. ( 1990 ) ‘The Sociology and Historiography of Immigration’, In Yans-McLaughlin V. , (ed.) Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Nestorowicz J. , Anacka M. ( 2018 ) ‘Mind the Gap? Quantifying Interlinkages between Two Traditions in Migration Literature,’ International Migration Review , 53/1 : 1 – 25 .

Pedraza-Bailey S. ( 1990 ) ‘Immigration Research: A Conceptual Map,’ Social Science History , 14 / 1 : 43 – 67 .

Penninx R. , Spencer D. , van Hear N. ( 2008 ) Migration and Integration in Europe: The State of Research . Oxford : ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society .

Piguet E. , Kaenzig R. , Guélat J. ( 2018 ) ‘The Uneven Geography of Research on “Environmental Migration”,’ Population and Environment , 39 / 4 : 357 – 83 .

Portes A. ( 1997 ) ‘Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and Opportunities,’ International Migration Review , 31 / 4 : 799 – 825 .

Pryor R. J. ( 1981 ) ‘Integrating International and Internal Migration Theories’, in Kritz M. M. , Keely C. B. , Tomasi S. M. (eds) Global Trends in Migration: Theory and Research on International Population Movements , pp. 110 – 129 . New York : The Center for Migration Studies .

Ravenstein G. E. ( 1885 ) ‘The Laws of Migration,’ Journal of the Royal Statistical Society , 48 : 167 – 235 .

Schinkel W. ( 2018 ) ‘Against “Immigrant Integration”: For an End to Neocolonial Knowledge Production,’ Comparative Migration Studies , 6 / 31 : 1 – 17 .

Scholten P. ( 2011 ) Framing Immigrant Integration: Dutch Research-Policy Dialogues in Comparative Perspective . Amsterdam : Amsterdam University Press .

Scholten P. ( 2018 ) Mainstreaming versus Alienation: Conceptualizing the Role of Complexity in Migration and Diversity Policymaking . Rotterdam : Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam .

Scholten P. , et al. ( 2015 ) Integrating Immigrants in Europe: Research-Policy Dialogues . Dordrecht : Springer .

Sweileh W. M. , et al. ( 2018 ) ‘Bibliometric Analysis of Global Migration Health Research in Peer-Reviewed Literature (2000–2016)’ , BMC Public Health , 18 / 777 : 1 – 18 .

Thomas D. S. ( 1938 ) Research Memorandum on Migration Differentials . New York : Social Science Research Council .

Thornthwaite C. W. ( 1934 ) Internal Migration in the United States . Philadelphia, PA : University of Pennsylvania Press .

Thränhardt D. , Bommes M. ( 2010 ) National Paradigms of Migration Research . Göttingen : V&R Unipress .

Urry J. ( 2007 ) Mobilities . Cambridge : Polity .

van Dalen H. ( 2018 ) ‘Is Migration Still Demography’s Stepchild?’ , Demos: Bulletin over Bevolking en Samenleving , 34 / 5 : 8 .

Vargas-Silva C. ( 2012 ) Handbook of Research Methods in Migration . Cheltenham : Edward Elgar .

Wimmer A. , Glick Schiller N. ( 2002 ) ‘Methodological Nationalism and beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences,’ Global Networks , 2 / 4 : 301 – 34 .

Yans-McLaughlin V. ( 1990 ) Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Zapata-Barrero R. , Yalaz E. ( 2018 ) Qualitative Research in European Migration Studies . Dordrecht : Springer .

Zapata-Barrero R. , Caponio T. , Scholten P. ( 2017 ) ‘Theorizing the “Local Turn” in a Multi-Level Governance Framework of Analysis: A Case Study in Immigrant Policies,’ International Review of Administrative Sciences , 83 / 2 : 241 – 6 .

Zolberg A. R. ( 1989 ) ‘The Next Waves: Migration Theory for a Changing World,’ International Migration Review , 23 / 3 : 403 – 30 .

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2049-5846

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

07 May 2024

McAuliffe, M. and L.A. Oucho (eds.), 2024. World Migration Report 2024. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva.

- Google Scholar

- EndNote X3 XML

- EndNote 7 XML

- Endnote tagged

World Migration Report 2024

Since 2000, IOM has been producing its flagship world migration reports every two years. The World Migration Report 2024 , the twelfth in the world migration report series, has been produced to contribute to increased understanding of migration and mobility throughout the world. This new edition presents key data and information on migration as well as thematic chapters on highly topical migration issues, and is structured to focus on two key contributions for readers: Part I: key information on migration and migrants (including migration-related statistics); and Part II: balanced, evidence-based analysis of complex and emerging migration issues.

This flagship World Migration Report has been produced in line with IOM’s Environment Policy and is available online only. Printed hard copies have not been made in order to reduce paper, printing and transportation impacts.

The World Migration Report 2024 interactive page is also available here .

- Editorial, review and production team

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Photographs

- List of figures and tables

- List of appendices

- Chapter 1 – Report overview: Migration continues to be part of the solution in a rapidly changing world, but key challenges remain

- Chapter 2 – Migration and migrants: A global overview

- Chapter 3 – Migration and migrants: Regional dimensions and developments

- Chapter 4 – Growing migration inequality: What do the global data actually show?

- Chapter 5 – Migration and human security: Unpacking myths and examining new realities and responses

- Chapter 6 – Gender and migration: Trends, gaps and urgent action

- Chapter 7 – Climate change, food insecurity and human mobility: Interlinkages, evidence and action

- Chapter 8 – Towards a global governance of migration? From the 2005 Global Commission on International Migration to the 2022 International Migration Review Forum and beyond

- Chapter 9 – A post-pandemic rebound? Migration and mobility globally after COVID-19

- Open access

- Published: 08 August 2018

Migration and health: a global public health research priority

- Kolitha Wickramage 1 ,

- Jo Vearey 2 ,

- Anthony B. Zwi 3 ,

- Courtland Robinson 4 &

- Michael Knipper 5

BMC Public Health volume 18 , Article number: 987 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

47k Accesses

129 Citations

105 Altmetric

Metrics details

With 244 million international migrants, and significantly more people moving within their country of birth, there is an urgent need to engage with migration at all levels in order to support progress towards global health and development targets. In response to this, the 2nd Global Consultation on Migration and Health– held in Colombo, Sri Lanka in February 2017 – facilitated discussions concerning the role of research in supporting evidence-informed health responses that engage with migration.

Conclusions

Drawing on discussions with policy makers, research scholars, civil society, and United Nations agencies held in Colombo, we emphasize the urgent need for quality research on international and domestic (in-country) migration and health to support efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs aim to ‘leave no-one behind’ irrespective of their legal status. An ethically sound human rights approach to research that involves engagement across multiple disciplines is required. Researchers need to be sensitive when designing and disseminating research findings as data on migration and health may be misused, both at an individual and population level. We emphasize the importance of creating an ‘enabling environment’ for migration and health research at national, regional and global levels, and call for the development of meaningful linkages – such as through research reference groups – to support evidence-informed inter-sectoral policy and priority setting processes.

Peer Review reports

Migration and health are increasingly recognized as a global public health priority [ 1 ]. Incorporating mixed flows of economic, forced, and irregular migration, migration has increased in extent and complexity. Globally, it is estimated that there are 244 million international migrants and significantly more internal migrants – people moving within their country of birth [ 2 ]. Whilst the majority of international migrants move between countries of the ‘global south’ [ 2 ], these movements between low and middle-income countries remain a “blind spot” for policymakers, researchers and the media, with disproportionate political and policy attention focused on irregular migration to high-income countries. Migration is increasingly recognized as a determinant of health [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. However, the bidirectional relationship between migration and health remains poorly understood, and action on migration and health remains limited, negatively impacting not only those who migrate but also sending, receiving, and ‘left-behind’ communities [ 1 ].

In February 2017, an international group of researchers participated in the 2nd Global Consultation on Migration and Health held in Colombo, Sri Lanka with the objectives of sharing lessons learned, good practices, and research in addressing the relationship between migration and health [ 1 ]. Hosted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Sri Lankan government, the Global Consultation brought together governments, civil society, international organizations, and academic representatives in order to address migration and health. The Consultation facilitated engagement with the health needs of migrants, reconciling the focus on long-term economic and structural migration - both within and across international borders - with that of acute, large-scale displacement flows that may include refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons and undocumented migrants.

The Consultation was organised around inputs on three thematic areas: Global Health [ 6 ]; Vulnerability and Resilience [ 7 ]; and, Development [ 8 ]. These inputs guided working group discussions exploring either policy, research, or monitoring in relation to migration and health. This paper reports on the outcomes of the research group after an extensive period of debate at the Consultation and over the subsequent 9 months. We identify key issues that should guide research practice in the field of migration and health, and outline strategies to support the development of evidence-informed policies and practices at global, regional, national, and local levels [ 9 ]. Debate and discussion at the Consultation, and below, were guided by two key questions:

What are the opportunities and challenges, and the essential components associated with developing a research agenda on migration and health?

What values and approaches should guide the development of a national research agenda and data collection system on migration and health?

Our discussions emphasized that international targets, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Universal Health Coverage (UHC; Health target 3.8 of the SDGs), are unlikely to be achieved if the dynamics of migration are not better understood and incorporated in policy and programming. To address this, and in order to improve policy and programming, a renewed focus on enhancing our understanding of the linkages between both international and internal migration and health, as well as the outcomes and impacts arising from them, is urgently needed.

Migration and health research: Leave no-one behind

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identify migration as both a catalyst and a driver for sustainable development. A clarion call of the SDGs is to ‘leave no-one behind’, irrespective of their legal status, in order to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for all [ 10 ]. In many countries, however, equitable access to health services is considered as a goal only in relation to citizens. Additionally, internal migration is left out of programming and policy interventions designed to support UHC for all. While UHC aims at ensuring “everyone” can access affordable health systems without increasing the risk of financial ruin or impoverishment, the formulation of UHC remains unclear regarding non-nationals/non-citizens [ 11 ]. While many international declarations state that the right to health applies to all, including migrants and non-citizens, many national policies exclude these groups in whole or part [ 12 ].

In addition to international and internal migration, the health concerns associated with labour migration require attention; migrant workers are estimated to account for 150.3 million of the 244 million international migrants [ 2 ]. While labour migration leads to significant economic gains for countries of origin and destination, true developmental benefits are only realised with access to safe, orderly and humane migration practice [ 13 ]. Many migrant labourers work in conditions of precarious employment, within ‘difficult, degrading and dangerous’ jobs yet little is known about the health status, health outcomes, and resilience/vulnerability trajectories of these migrant workers and their ‘left behind’ families. Many undergo health assessments as a pre-condition for travel and migration, yet many such programs remain unlinked to national public health systems [ 14 ].

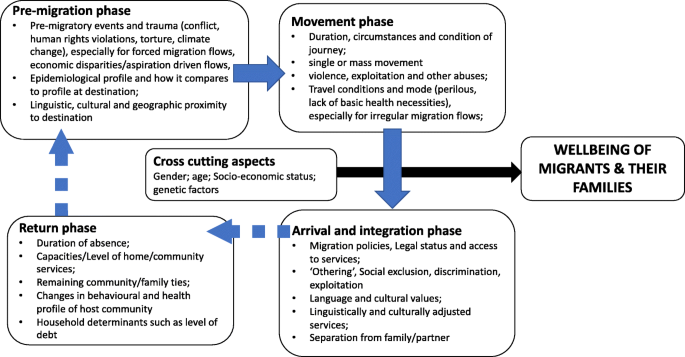

Our discussions highlighted the complex and heterogeneous nature of research on migration and health, with particular concerns raised around the emphasis on international rather than internal migration, in view of the greater volume of the latter. The need for a multilevel research agenda to guide appropriate action on international and internal migration, health, and development was highlighted. In order to account for immediate, long-term and inter-generational impacts on health outcomes, migration and health research should: (1) incorporate the different phases of migration (Fig. 1 ); (2) adopt a life-course approach; and, (3) integrate a social determinants of health (SDH) approach.

Factors influencing health and wellbeing of migrants and their families along the phases of migration

Unease was expressed about the increasingly polarised political viewpoints on migration, often propagated by nationalist and populist movements, which present real challenges to researchers. This may also be associated with a reluctance to finance research exploring discriminatory policies that limit the access of international migrants to health services and other positive determinants of health, including work and housing.

The increasing complexity of global, regional, and national migration trends, as well as disagreements about the correct way to define and label different types of migrants, create additional difficulties within an already tense and politically contested research domain. Associated with this are the particular challenges associated with collecting and utilising data on ‘irregular migrants’ – international migrants currently without the documentation required to legally be in a particular country. These undocumented migrants, often living in the shadows of society, are more vulnerable to poor health outcomes due to restrictive policies on access to health and social services, to safe working and living conditions, and/or a reluctance to access services for fear of arrest, detention and/or deportation [ 15 , 16 ]. Whilst arguments for improving access to health care for marginalised migrants are based on principles of equity, public health, and human rights, the importance of research on the economic implications of limiting access to care for international migrants was highlighted [ 2 ]. This challenging terrain generated a myriad of research questions during the group discussions (Table 1 ).

Towards a framework for advancing migration and health research

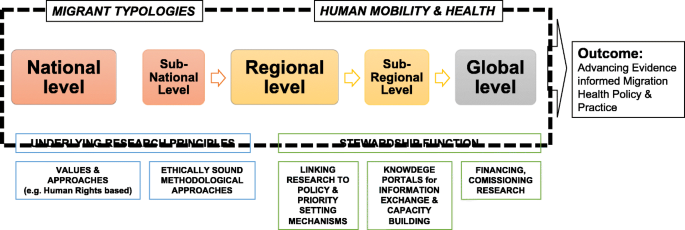

The consultation took into account the extensive research experience of the group (see Appendix ), as well as engagement with key literature and context-specific evidence [see, for example 1–7]. Discussion led to the development of a framework that brings together what we identify as the key components for advancing a global, multi-level, migration and health research agenda (Fig. 2 ). Two areas of focus to advance the migration and health research agenda were identified: (1) exploring health issues across various migrant typologies , and (2) improving our understanding of the interactions between migration and health . Advancing research in both areas is essential if we are to improve our understanding of how to respond to the complex linkages between both international and internal migration and health. This, we argue, can be achieved by moving away from an approach that exceptionalises migration and migrants, to one that integrates migration into overall health systems research, design, and delivery, and conceptualises this as a way to support the achievement of good health for all.

Advancing Migration and Health Research at National, Regional and Global Levels: a conceptual framework

Building from these focus areas, our framework outlines the essential components for the development and application of multi-level research on migration and health. First are key principles underlying research practice: promoting interdisciplinary, human rights oriented, ethically sound approaches for working with migrants. Second are multi-level stewardship functions needed to meaningfully link migration and health research to policy practice and priority setting, [ 17 ]. This includes establishing knowledge exchange mechanisms, financing, commissioning, and utilising research to guide evidence informed policies. This may better enable health systems to become ‘migration aware’ [ 18 ] or what the International Organization for Migration (IOM) terms ‘mobility competent’ - sensitive to health and migration [ 1 ].

Migration and health research: Two key focus areas

Migrant typologies.