How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

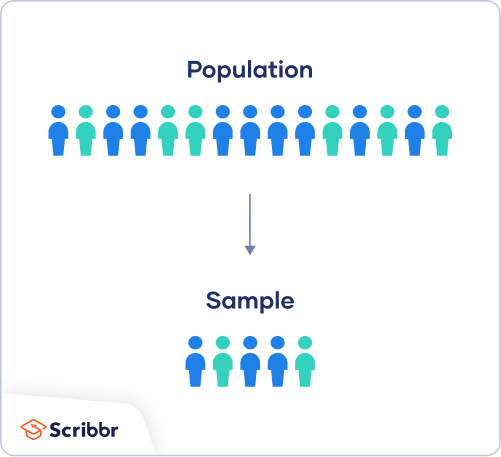

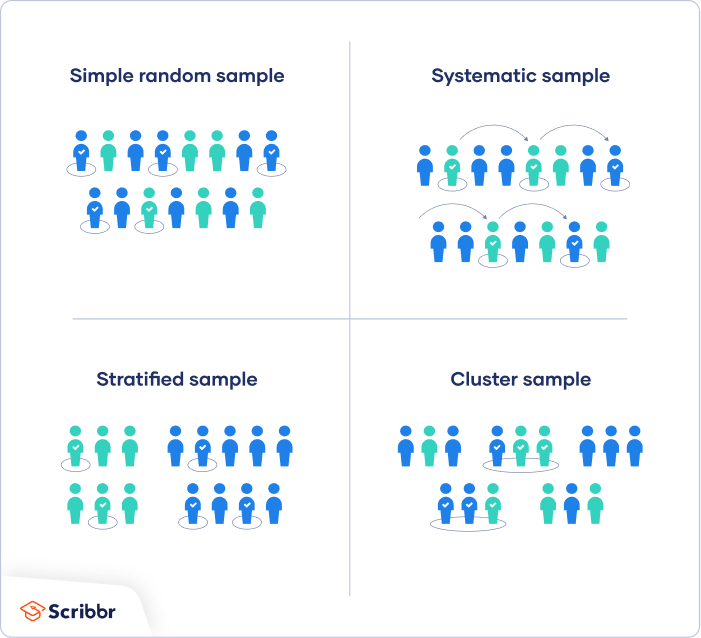

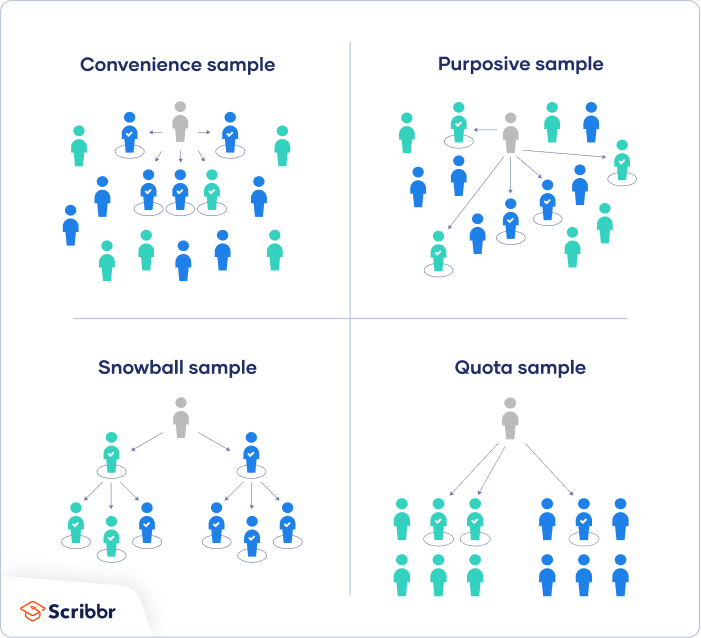

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How To Write A Research Paper

Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example - Examples for Different Formats

Published on: Jun 12, 2021

Last updated on: Feb 6, 2024

People also read

How to Write a Research Paper Step by Step

How to Write a Proposal For a Research Paper in 10 Steps

A Comprehensive Guide to Creating a Research Paper Outline

Types of Research - Methodologies and Characteristics

300+ Engaging Research Paper Topics to Get You Started

Interesting Psychology Research Topics & Ideas

Qualitative Research - Types, Methods & Examples

Understanding Quantitative Research - Definition, Types, Examples, And More

How To Start A Research Paper - Steps With Examples

How to Write an Abstract That Captivates Your Readers

How To Write a Literature Review for a Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Types of Qualitative Research Methods - An Overview

Understanding Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research - A Complete Guide

How to Cite a Research Paper in Different Citation Styles

Easy Sociology Research Topics for Your Next Project

200+ Outstanding History Research Paper Topics With Expert Tips

How To Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Write a Good Research Paper Title

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper in 3 Simple Steps

How to Write an Abstract For a Research Paper with Examples

How To Write a Thesis For a Research Paper Step by Step

How to Write a Discussion For a Research Paper | Objectives, Steps & Examples

How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper - Structure and Tips

How to Write a Problem Statement for a Research Paper in 6 Steps

How To Write The Methods Section of a Research Paper Step-by-Step

How to Find Sources For a Research Paper | A Guide

Share this article

Writing a research paper is the most challenging task in a student's academic life. researchers face similar writing process hardships, whether the research paper is to be written for graduate or masters.

A research paper is a writing type in which a detailed analysis, interpretation, and evaluation are made on the topic. It requires not only time but also effort and skills to be drafted correctly.

If you are working on your research paper for the first time, here is a collection of examples that you will need to understand the paper’s format and how its different parts are drafted. Continue reading the article to get free research paper examples.

On This Page On This Page -->

Research Paper Example for Different Formats

A research paper typically consists of several key parts, including an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, and annotated bibliography .

When writing a research paper (whether quantitative research or qualitative research ), it is essential to know which format to use to structure your content. Depending on the requirements of the institution, there are mainly four format styles in which a writer drafts a research paper:

Letâs look into each format in detail to understand the fundamental differences and similarities.

Research Paper Example APA

If your instructor asks you to provide a research paper in an APA format, go through the example given below and understand the basic structure. Make sure to follow the format throughout the paper.

APA Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example MLA

Another widespread research paper format is MLA. A few institutes require this format style as well for your research paper. Look at the example provided of this format style to learn the basics.

MLA Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example Chicago

Unlike MLA and APA styles, Chicago is not very common. Very few institutions require this formatting style research paper, but it is essential to learn it. Look at the example given below to understand the formatting of the content and citations in the research paper.

Chicago Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example Harvard

Learn how a research paper through Harvard formatting style is written through this example. Carefully examine how the cover page and other pages are structured.

Harvard Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

A research paper is based on different parts. Each part plays a significant role in the overall success of the paper. So each chapter of the paper must be drafted correctly according to a format and structure.

Below are examples of how different sections of the research paper are drafted.

Research Proposal Example

A research proposal is a plan that describes what you will investigate, its significance, and how you will conduct the study.

Research Proposal Sample (PDF)

Abstract Research Paper Example

An abstract is an executive summary of the research paper that includes the purpose of the research, the design of the study, and significant research findings.

It is a small section that is based on a few paragraphs. Following is an example of the abstract to help you draft yours professionally.

Abstract Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Literature Review Research Paper Example

A literature review in a research paper is a comprehensive summary of the previous research on your topic. It studies sources like books, articles, journals, and papers on the relevant research problem to form the basis of the new research.

Writing this section of the research paper perfectly is as important as any part of it.

Literature Review in Research Sample (PDF)

Methods Section of Research Paper Example

The method section comes after the introduction of the research paper that presents the process of collecting data. Basically, in this section, a researcher presents the details of how your research was conducted.

Methods Section in Research Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Conclusion Example

The conclusion is the last part of your research paper that sums up the writerâs discussion for the audience and leaves an impression. This is how it should be drafted:

Research Paper Conclusion Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

The research papers are not limited to a particular field. They can be written for any discipline or subject that needs a detailed study.

In the following section, various research paper examples are given to show how they are drafted for different subjects.

Science Research Paper Example

Are you a science student that has to conduct research? Here is an example for you to draft a compelling research paper for the field of science.

Science Research Paper Sample (PDF)

History Research Paper Example

Conducting research and drafting a paper is not only bound to science subjects. Other subjects like history and arts require a research paper to be written as well. Observe how research papers related to history are drafted.

History Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Psychology Research Paper Example

If you are a psychology student, look into the example provided in the research paper to help you draft yours professionally.

Psychology Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example for Different Levels

Writing a research paper is based on a list of elements. If the writer is not aware of the basic elements, the process of writing the paper will become daunting. Start writing your research paper taking the following steps:

- Choose a topic

- Form a strong thesis statement

- Conduct research

- Develop a research paper outline

Once you have a plan in your hand, the actual writing procedure will become a piece of cake for you.

No matter which level you are writing a research paper for, it has to be well structured and written to guarantee you better grades.

If you are a college or a high school student, the examples in the following section will be of great help.

Research Paper Outline (PDF)

Research Paper Example for College

Pay attention to the research paper example provided below. If you are a college student, this sample will help you understand how a winning paper is written.

College Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example for High School

Expert writers of CollegeEssay.org have provided an excellent example of a research paper for high school students. If you are struggling to draft an exceptional paper, go through the example provided.

High School Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Examples are essential when it comes to academic assignments. If you are a student and aim to achieve good grades in your assignments, it is suggested to get help from CollegeEssay.org .

We are the best writing company that delivers essay help for students by providing free samples and writing assistance.

Professional writers have your back, whether you are looking for guidance in writing a lab report, college essay, or research paper.

Simply hire a writer by placing your order at the most reasonable price. You can also take advantage of our essay writer to enhance your writing skills.

Nova A. (Literature, Marketing)

As a Digital Content Strategist, Nova Allison has eight years of experience in writing both technical and scientific content. With a focus on developing online content plans that engage audiences, Nova strives to write pieces that are not only informative but captivating as well.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Research Paper Guide

Research Paper Example

Research Paper Examples - Free Sample Papers for Different Formats!

People also read

Research Paper Writing - A Step by Step Guide

Guide to Creating Effective Research Paper Outline

Interesting Research Paper Topics for 2024

Research Proposal Writing - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Start a Research Paper - 7 Easy Steps

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper - A Step by Step Guide

Writing a Literature Review For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Qualitative Research - Methods, Types, and Examples

8 Types of Qualitative Research - Overview & Examples

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research - Learning the Basics

200+ Engaging Psychology Research Paper Topics for Students in 2024

Learn How to Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper: Examples and Tips!

20+ Types of Research With Examples - A Detailed Guide

Understanding Quantitative Research - Types & Data Collection Techniques

230+ Sociology Research Topics & Ideas for Students

How to Cite a Research Paper - A Complete Guide

Excellent History Research Paper Topics- 300+ Ideas

A Guide on Writing the Method Section of a Research Paper - Examples & Tips

How To Write an Introduction Paragraph For a Research Paper: Learn with Examples

Crafting a Winning Research Paper Title: A Complete Guide

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion - Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a Thesis For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write A Discussion For A Research Paper | Examples & Tips

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Writing a Problem Statement for a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Finding Sources For a Research Paper: A Complete Guide

A Guide on How to Edit a Research Paper

200+ Ethical Research Paper Topics to Begin With (2024)

300+ Controversial Research Paper Topics & Ideas - 2024 Edition

150+ Argumentative Research Paper Topics For You - 2024

How to Write a Research Methodology for a Research Paper

Crafting a comprehensive research paper can be daunting. Understanding diverse citation styles and various subject areas presents a challenge for many.

Without clear examples, students often feel lost and overwhelmed, unsure of how to start or which style fits their subject.

Explore our collection of expertly written research paper examples. We’ve covered various citation styles and a diverse range of subjects.

So, read on!

- 1. Research Paper Example for Different Formats

- 2. Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

- 3. Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

- 4. Research Paper Example Outline

Research Paper Example for Different Formats

Following a specific formatting style is essential while writing a research paper . Knowing the conventions and guidelines for each format can help you in creating a perfect paper. Here we have gathered examples of research paper for most commonly applied citation styles :

Social Media and Social Media Marketing: A Literature Review

APA Research Paper Example

APA (American Psychological Association) style is commonly used in social sciences, psychology, and education. This format is recognized for its clear and concise writing, emphasis on proper citations, and orderly presentation of ideas.

Here are some research paper examples in APA style:

Research Paper Example APA 7th Edition

Research Paper Example MLA

MLA (Modern Language Association) style is frequently employed in humanities disciplines, including literature, languages, and cultural studies. An MLA research paper might explore literature analysis, linguistic studies, or historical research within the humanities.

Here is an example:

Found Voices: Carl Sagan

Research Paper Example Chicago

Chicago style is utilized in various fields like history, arts, and social sciences. Research papers in Chicago style could delve into historical events, artistic analyses, or social science inquiries.

Here is a research paper formatted in Chicago style:

Chicago Research Paper Sample

Research Paper Example Harvard

Harvard style is widely used in business, management, and some social sciences. Research papers in Harvard style might address business strategies, case studies, or social policies.

View this sample Harvard style paper here:

Harvard Research Paper Sample

Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

A research paper has different parts. Each part is important for the overall success of the paper. Chapters in a research paper must be written correctly, using a certain format and structure.

The following are examples of how different sections of the research paper can be written.

Research Proposal

The research proposal acts as a detailed plan or roadmap for your study, outlining the focus of your research and its significance. It's essential as it not only guides your research but also persuades others about the value of your study.

Example of Research Proposal

An abstract serves as a concise overview of your entire research paper. It provides a quick insight into the main elements of your study. It summarizes your research's purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions in a brief format.

Research Paper Example Abstract

Literature Review

A literature review summarizes the existing research on your study's topic, showcasing what has already been explored. This section adds credibility to your own research by analyzing and summarizing prior studies related to your topic.

Literature Review Research Paper Example

Methodology

The methodology section functions as a detailed explanation of how you conducted your research. This part covers the tools, techniques, and steps used to collect and analyze data for your study.

Methods Section of Research Paper Example

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

The conclusion summarizes your findings, their significance and the impact of your research. This section outlines the key takeaways and the broader implications of your study's results.

Research Paper Conclusion Example

Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

Research papers can be about any subject that needs a detailed study. The following examples show research papers for different subjects.

History Research Paper Sample

Preparing a history research paper involves investigating and presenting information about past events. This may include exploring perspectives, analyzing sources, and constructing a narrative that explains the significance of historical events.

View this history research paper sample:

Many Faces of Generalissimo Fransisco Franco

Sociology Research Paper Sample

In sociology research, statistics and data are harnessed to explore societal issues within a particular region or group. These findings are thoroughly analyzed to gain an understanding of the structure and dynamics present within these communities.

Here is a sample:

A Descriptive Statistical Analysis within the State of Virginia

Science Fair Research Paper Sample

A science research paper involves explaining a scientific experiment or project. It includes outlining the purpose, procedures, observations, and results of the experiment in a clear, logical manner.

Here are some examples:

Science Fair Paper Format

What Do I Need To Do For The Science Fair?

Psychology Research Paper Sample

Writing a psychology research paper involves studying human behavior and mental processes. This process includes conducting experiments, gathering data, and analyzing results to understand the human mind, emotions, and behavior.

Here is an example psychology paper:

The Effects of Food Deprivation on Concentration and Perseverance

Art History Research Paper Sample

Studying art history includes examining artworks, understanding their historical context, and learning about the artists. This helps analyze and interpret how art has evolved over various periods and regions.

Check out this sample paper analyzing European art and impacts:

European Art History: A Primer

Research Paper Example Outline

Before you plan on writing a well-researched paper, make a rough draft. An outline can be a great help when it comes to organizing vast amounts of research material for your paper.

Here is an outline of a research paper example:

Here is a downloadable sample of a standard research paper outline:

Research Paper Outline

Want to create the perfect outline for your paper? Check out this in-depth guide on creating a research paper outline for a structured paper!

Good Research Paper Examples for Students

Here are some more samples of research paper for students to learn from:

Fiscal Research Center - Action Plan

Qualitative Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example Introduction

How to Write a Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example for High School

Now that you have explored the research paper examples, you can start working on your research project. Hopefully, these examples will help you understand the writing process for a research paper.

If you're facing challenges with your writing requirements, you can hire our essay writing service .

Our team is experienced in delivering perfectly formatted, 100% original research papers. So, whether you need help with a part of research or an entire paper, our experts are here to deliver.

So, why miss out? Place your ‘ write my research paper ’ request today and get a top-quality research paper!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Nova Allison is a Digital Content Strategist with over eight years of experience. Nova has also worked as a technical and scientific writer. She is majorly involved in developing and reviewing online content plans that engage and resonate with audiences. Nova has a passion for writing that engages and informs her readers.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Research Paper Examples

Research paper examples are of great value for students who want to complete their assignments timely and efficiently. If you are a student in the university, your first stop in the quest for research paper examples will be the campus library where you can get to view the research sample papers of lecturers and other professionals in diverse fields plus those of fellow students who preceded you in the campus. Many college departments maintain libraries of previous student work, including large research papers, which current students can examine.

Embark on a journey of academic excellence with iResearchNet, your premier destination for research paper examples that illuminate the path to scholarly success. In the realm of academia, where the pursuit of knowledge is both a challenge and a privilege, the significance of having access to high-quality research paper examples cannot be overstated. These exemplars are not merely papers; they are beacons of insight, guiding students and scholars through the complex maze of academic writing and research methodologies.

At iResearchNet, we understand that the foundation of academic achievement lies in the quality of resources at one’s disposal. This is why we are dedicated to offering a comprehensive collection of research paper examples across a multitude of disciplines. Each example stands as a testament to rigorous research, clear writing, and the deep understanding necessary to advance in one’s academic and professional journey.

Access to superior research paper examples equips learners with the tools to develop their own ideas, arguments, and hypotheses, fostering a cycle of learning and discovery that transcends traditional boundaries. It is with this vision that iResearchNet commits to empowering students and researchers, providing them with the resources to not only meet but exceed the highest standards of academic excellence. Join us on this journey, and let iResearchNet be your guide to unlocking the full potential of your academic endeavors.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, what is a research paper.

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Criminal Justice

- Criminal Law

- Criminology

- Mental Health

- Political Science

Importance of Research Paper Examples

- Research Paper Writing Services

A Sample Research Paper on Child Abuse

A research paper represents the pinnacle of academic investigation, a scholarly manuscript that encapsulates a detailed study, analysis, or argument based on extensive independent research. It is an embodiment of the researcher’s ability to synthesize a wealth of information, draw insightful conclusions, and contribute novel perspectives to the existing body of knowledge within a specific field. At its core, a research paper strives to push the boundaries of what is known, challenging existing theories and proposing new insights that could potentially reshape the understanding of a particular subject area.

The objective of writing a research paper is manifold, serving both educational and intellectual pursuits. Primarily, it aims to educate the author, providing a rigorous framework through which they engage deeply with a topic, hone their research and analytical skills, and learn the art of academic writing. Beyond personal growth, the research paper serves the broader academic community by contributing to the collective pool of knowledge, offering fresh perspectives, and stimulating further research. It is a medium through which scholars communicate ideas, findings, and theories, thereby fostering an ongoing dialogue that propels the advancement of science, humanities, and other fields of study.

Research papers can be categorized into various types, each with distinct objectives and methodologies. The most common types include:

- Analytical Research Paper: This type focuses on analyzing different viewpoints represented in the scholarly literature or data. The author critically evaluates and interprets the information, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

- Argumentative or Persuasive Research Paper: Here, the author adopts a stance on a contentious issue and argues in favor of their position. The objective is to persuade the reader through evidence and logic that the author’s viewpoint is valid or preferable.

- Experimental Research Paper: Often used in the sciences, this type documents the process, results, and implications of an experiment conducted by the author. It provides a detailed account of the methodology, data collected, analysis performed, and conclusions drawn.

- Survey Research Paper: This involves collecting data from a set of respondents about their opinions, behaviors, or characteristics. The paper analyzes this data to draw conclusions about the population from which the sample was drawn.

- Comparative Research Paper: This type involves comparing and contrasting different theories, policies, or phenomena. The aim is to highlight similarities and differences, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of the subjects under review.

- Cause and Effect Research Paper: It explores the reasons behind specific actions, events, or conditions and the consequences that follow. The goal is to establish a causal relationship between variables.

- Review Research Paper: This paper synthesizes existing research on a particular topic, offering a comprehensive analysis of the literature to identify trends, gaps, and consensus in the field.

Understanding the nuances and objectives of these various types of research papers is crucial for scholars and students alike, as it guides their approach to conducting and writing up their research. Each type demands a unique set of skills and perspectives, pushing the author to think critically and creatively about their subject matter. As the academic landscape continues to evolve, the research paper remains a fundamental tool for disseminating knowledge, encouraging innovation, and fostering a culture of inquiry and exploration.

Browse Sample Research Papers

iResearchNet prides itself on offering a wide array of research paper examples across various disciplines, meticulously curated to support students, educators, and researchers in their academic endeavors. Each example embodies the hallmarks of scholarly excellence—rigorous research, analytical depth, and clear, precise writing. Below, we explore the diverse range of research paper examples available through iResearchNet, designed to inspire and guide users in their quest for academic achievement.

Anthropology Research Paper Examples

Our anthropology research paper examples delve into the study of humanity, exploring cultural, social, biological, and linguistic variations among human populations. These papers offer insights into human behavior, traditions, and evolution, providing a comprehensive overview of anthropological research methods and theories.

- Archaeology Research Paper

- Forensic Anthropology Research Paper

- Linguistics Research Paper

- Medical Anthropology Research Paper

- Social Problems Research Paper

Art Research Paper Examples

The art research paper examples feature analyses of artistic expressions across different cultures and historical periods. These papers cover a variety of topics, including art history, criticism, and theory, as well as the examination of specific artworks or movements.

- Performing Arts Research Paper

- Music Research Paper

- Architecture Research Paper

- Theater Research Paper

- Visual Arts Research Paper

Cancer Research Paper Examples

Our cancer research paper examples focus on the latest findings in the field of oncology, discussing the biological mechanisms of cancer, advancements in diagnostic techniques, and innovative treatment strategies. These papers aim to contribute to the ongoing battle against cancer by sharing cutting-edge research.

- Breast Cancer Research Paper

- Leukemia Research Paper

- Lung Cancer Research Paper

- Ovarian Cancer Research Paper

- Prostate Cancer Research Paper

Communication Research Paper Examples

These examples explore the complexities of human communication, covering topics such as media studies, interpersonal communication, and public relations. The papers examine how communication processes affect individuals, societies, and cultures.

- Advertising Research Paper

- Journalism Research Paper

- Media Research Paper

- Public Relations Research Paper

- Public Speaking Research Paper

Crime Research Paper Examples

The crime research paper examples provided by iResearchNet investigate various aspects of criminal behavior and the factors contributing to crime. These papers cover a range of topics, from theoretical analyses of criminality to empirical studies on crime prevention strategies.

- Computer Crime Research Paper

- Domestic Violence Research Paper

- Hate Crimes Research Paper

- Organized Crime Research Paper

- White-Collar Crime Research Paper

Criminal Justice Research Paper Examples

Our criminal justice research paper examples delve into the functioning of the criminal justice system, exploring issues related to law enforcement, the judiciary, and corrections. These papers critically examine policies, practices, and reforms within the criminal justice system.

- Capital Punishment Research Paper

- Community Policing Research Paper

- Corporal Punishment Research Paper

- Criminal Investigation Research Paper

- Criminal Justice System Research Paper

- Plea Bargaining Research Paper

- Restorative Justice Research Paper

Criminal Law Research Paper Examples

These examples focus on the legal aspects of criminal behavior, discussing laws, regulations, and case law that govern criminal proceedings. The papers provide an in-depth analysis of criminal law principles, legal defenses, and the implications of legal decisions.

- Actus Reus Research Paper

- Gun Control Research Paper

- Insanity Defense Research Paper

- International Criminal Law Research Paper

- Self-Defense Research Paper

Criminology Research Paper Examples

iResearchNet’s criminology research paper examples study the causes, prevention, and societal impacts of crime. These papers employ various theoretical frameworks to analyze crime trends and propose effective crime reduction strategies.

- Cultural Criminology Research Paper

- Education and Crime Research Paper

- Marxist Criminology Research Paper

- School Crime Research Paper

- Urban Crime Research Paper

Culture Research Paper Examples

The culture research paper examples examine the beliefs, practices, and artifacts that define different societies. These papers explore how culture shapes identities, influences behaviors, and impacts social interactions.

- Advertising and Culture Research Paper

- Material Culture Research Paper

- Popular Culture Research Paper

- Cross-Cultural Studies Research Paper

- Culture Change Research Paper

Economics Research Paper Examples

Our economics research paper examples offer insights into the functioning of economies at both the micro and macro levels. Topics include economic theory, policy analysis, and the examination of economic indicators and trends.

- Budget Research Paper

- Cost-Benefit Analysis Research Paper

- Fiscal Policy Research Paper

- Labor Market Research Paper

Education Research Paper Examples

These examples address a wide range of issues in education, from teaching methods and curriculum design to educational policy and reform. The papers aim to enhance understanding and improve outcomes in educational settings.

- Early Childhood Education Research Paper

- Information Processing Research Paper

- Multicultural Education Research Paper

- Special Education Research Paper

- Standardized Tests Research Paper

Health Research Paper Examples

The health research paper examples focus on public health issues, healthcare systems, and medical interventions. These papers contribute to the discourse on health promotion, disease prevention, and healthcare management.

- AIDS Research Paper

- Alcoholism Research Paper

- Disease Research Paper

- Health Economics Research Paper

- Health Insurance Research Paper

- Nursing Research Paper

History Research Paper Examples

Our history research paper examples cover significant events, figures, and periods, offering critical analyses of historical narratives and their impact on present-day society.

- Adolf Hitler Research Paper

- American Revolution Research Paper

- Ancient Greece Research Paper

- Apartheid Research Paper

- Christopher Columbus Research Paper

- Climate Change Research Paper

- Cold War Research Paper

- Columbian Exchange Research Paper

- Deforestation Research Paper

- Diseases Research Paper

- Earthquakes Research Paper

- Egypt Research Paper

Leadership Research Paper Examples

These examples explore the theories and practices of effective leadership, examining the qualities, behaviors, and strategies that distinguish successful leaders in various contexts.

- Implicit Leadership Theories Research Paper

- Judicial Leadership Research Paper

- Leadership Styles Research Paper

- Police Leadership Research Paper

- Political Leadership Research Paper

- Remote Leadership Research Paper

Mental Health Research Paper Examples

The mental health research paper examples provided by iResearchNet discuss psychological disorders, therapeutic interventions, and mental health advocacy. These papers aim to raise awareness and improve mental health care practices.

- ADHD Research Paper

- Anxiety Research Paper

- Autism Research Paper

- Depression Research Paper

- Eating Disorders Research Paper

- PTSD Research Paper

- Schizophrenia Research Paper

- Stress Research Paper

Political Science Research Paper Examples

Our political science research paper examples analyze political systems, behaviors, and ideologies. Topics include governance, policy analysis, and the study of political movements and institutions.

- American Government Research Paper

- Civil War Research Paper

- Communism Research Paper

- Democracy Research Paper

- Game Theory Research Paper

- Human Rights Research Paper

- International Relations Research Paper

- Terrorism Research Paper

Psychology Research Paper Examples

These examples delve into the study of the mind and behavior, covering a broad range of topics in clinical, cognitive, developmental, and social psychology.

- Artificial Intelligence Research Paper

- Assessment Psychology Research Paper

- Biological Psychology Research Paper

- Clinical Psychology Research Paper

- Cognitive Psychology Research Paper

- Developmental Psychology Research Paper

- Discrimination Research Paper

- Educational Psychology Research Paper

- Environmental Psychology Research Paper

- Experimental Psychology Research Paper

- Intelligence Research Paper

- Learning Disabilities Research Paper

- Personality Psychology Research Paper

- Psychiatry Research Paper

- Psychotherapy Research Paper

- Social Cognition Research Paper

- Social Psychology Research Paper

Sociology Research Paper Examples

The sociology research paper examples examine societal structures, relationships, and processes. These papers provide insights into social phenomena, inequality, and change.

- Family Research Paper

- Demography Research Paper

- Group Dynamics Research Paper

- Quality of Life Research Paper

- Social Change Research Paper

- Social Movements Research Paper

- Social Networks Research Paper

Technology Research Paper Examples

Our technology research paper examples address the impact of technological advancements on society, exploring issues related to digital communication, cybersecurity, and innovation.

- Computer Forensics Research Paper

- Genetic Engineering Research Paper

- History of Technology Research Paper

- Internet Research Paper

- Nanotechnology Research Paper

Other Research Paper Examples

- Abortion Research Paper

- Adoption Research Paper

- Animal Testing Research Paper

- Bullying Research Paper

- Diversity Research Paper

- Divorce Research Paper

- Drugs Research Paper

- Environmental Issues Research Paper

- Ethics Research Paper

- Evolution Research Paper

- Feminism Research Paper

- Food Research Paper

- Gender Research Paper

- Globalization Research Paper

- Juvenile Justice Research Paper

- Law Research Paper

- Management Research Paper

- Philosophy Research Paper

- Public Health Research Paper

- Religion Research Paper

- Science Research Paper

- Social Sciences Research Paper

- Statistics Research Paper

- Other Sample Research Papers

Each category of research paper examples provided by iResearchNet serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers seeking to deepen their understanding of a specific field. By offering a comprehensive collection of well-researched and thoughtfully written papers, iResearchNet aims to support academic growth and encourage scholarly inquiry across diverse disciplines.

Sample Research Papers: To Read or Not to Read?

When you get an assignment to write a research paper, the first question you ask yourself is ‘Should I look for research paper examples?’ Maybe, I can deal with this task on my own without any help. Is it that difficult?

Thousands of students turn to our service every day for help. It does not mean that they cannot do their assignments on their own. They can, but the reason is different. Writing a research paper demands so much time and energy that asking for assistance seems to be a perfect solution. As the matter of fact, it is a perfect solution, especially, when you need to work to pay for your studying as well.

Firstly, if you search for research paper examples before you start writing, you can save your time significantly. You look at the example and you understand the gist of your assignment within several minutes. Secondly, when you examine some sample paper, you get to know all the requirements. You analyze the structure, the language, and the formatting details. Finally, reading examples helps students to overcome writer’s block, as other people’s ideas can motivate you to discover your own ideas.

The significance of research paper examples in the academic journey of students cannot be overstated. These examples serve not only as a blueprint for structuring and formatting academic papers but also as a beacon guiding students through the complex landscape of academic writing standards. iResearchNet recognizes the pivotal role that high-quality research paper examples play in fostering academic success and intellectual growth among students.

Blueprint for Academic Success

Research paper examples provided by iResearchNet are meticulously crafted to demonstrate the essential elements of effective academic writing. These examples offer clear insights into how to organize a paper, from the introductory paragraph, through the development of arguments and analysis, to the concluding remarks. They showcase the appropriate use of headings, subheadings, and the integration of tables, figures, and appendices, which collectively contribute to a well-organized and coherent piece of scholarly work. By studying these examples, students can gain a comprehensive understanding of the structure and formatting required in academic papers, which is crucial for meeting the rigorous standards of academic institutions.

Sparking Ideas and Providing Evidence

Beyond serving as a structural guide, research paper examples act as a source of inspiration for students embarking on their research projects. These examples illuminate a wide array of topics, methodologies, and analytical frameworks, thereby sparking ideas for students’ own research inquiries. They demonstrate how to effectively engage with existing literature, frame research questions, and develop a compelling thesis statement. Moreover, by presenting evidence and arguments in a logical and persuasive manner, these examples illustrate the art of substantiating claims with solid research, encouraging students to adopt a similar level of rigor and depth in their work.

Enhancing Research Skills

Engagement with high-quality research paper examples is instrumental in improving research skills among students. These examples expose students to various research methodologies, from qualitative case studies to quantitative analyses, enabling them to appreciate the breadth of research approaches applicable to their fields of study. By analyzing these examples, students learn how to critically evaluate sources, differentiate between primary and secondary data, and apply ethical considerations in research. Furthermore, these papers serve as a model for effectively citing sources, thereby teaching students the importance of academic integrity and the avoidance of plagiarism.

In essence, research paper examples are a fundamental resource that can significantly enhance the academic writing and research capabilities of students. iResearchNet’s commitment to providing access to a diverse collection of exemplary papers reflects its dedication to supporting academic excellence. Through these examples, students are equipped with the tools necessary to navigate the challenges of academic writing, foster innovative thinking, and contribute meaningfully to the scholarly community. By leveraging these resources, students can elevate their academic pursuits, ensuring their research is not only rigorous but also impactful.

Custom Research Paper Writing Services

In the academic journey, the ability to craft a compelling and meticulously researched paper is invaluable. Recognizing the challenges and pressures that students face, iResearchNet has developed a suite of research paper writing services designed to alleviate the burden of academic writing and research. Our services are tailored to meet the diverse needs of students across all academic disciplines, ensuring that every research paper not only meets but exceeds the rigorous standards of scholarly excellence. Below, we detail the multifaceted aspects of our research paper writing services, illustrating how iResearchNet stands as a beacon of support in the academic landscape.

At iResearchNet, we understand the pivotal role that research papers play in the academic and professional development of students. With this understanding at our core, we offer comprehensive writing services that cater to the intricate process of research paper creation. Our services are designed to guide students through every stage of the writing process, from initial research to final submission, ensuring clarity, coherence, and scholarly rigor.

The Need for Research Paper Writing Services

Navigating the complexities of academic writing and research can be a daunting task for many students. The challenges of identifying credible sources, synthesizing information, adhering to academic standards, and articulating arguments cohesively are significant. Furthermore, the pressures of tight deadlines and the high stakes of academic success can exacerbate the difficulties faced by students. iResearchNet’s research paper writing services are crafted to address these challenges head-on, providing expert assistance that empowers students to achieve their academic goals with confidence.

Why Choose iResearchNet

Selecting the right partner for research paper writing is a pivotal decision for students and researchers aiming for academic excellence. iResearchNet stands out as the premier choice for several compelling reasons, each designed to meet the diverse needs of our clientele and ensure their success.

- Expert Writers : At iResearchNet, we pride ourselves on our team of expert writers who are not only masters in their respective fields but also possess a profound understanding of academic writing standards. With advanced degrees and extensive experience, our writers bring depth, insight, and precision to each paper, ensuring that your work is informed by the latest research and methodologies.

- Top Quality : Quality is the cornerstone of our services. We adhere to rigorous quality control processes to ensure that every paper we deliver meets the highest standards of academic excellence. Our commitment to quality means thorough research, impeccable writing, and meticulous proofreading, resulting in work that not only meets but exceeds expectations.

- Customized Solutions : Understanding that each research project has its unique challenges and requirements, iResearchNet offers customized solutions tailored to your specific needs. Whether you’re grappling with a complex research topic, a tight deadline, or specific formatting guidelines, our team is equipped to provide personalized support that aligns with your objectives.

- Affordable Prices : We believe that access to high-quality research paper writing services should not be prohibitive. iResearchNet offers competitive pricing structures designed to provide value without compromising on quality. Our transparent pricing model ensures that you know exactly what you are paying for, with no hidden costs or surprises.

- Timely Delivery : Meeting deadlines is critical in academic writing, and at iResearchNet, we take this seriously. Our efficient processes and dedicated team ensure that your paper is delivered on time, every time, allowing you to meet your academic deadlines with confidence.

- 24/7 Support : Our commitment to your success is reflected in our round-the-clock support. Whether you have a question about your order, need to communicate with your writer, or require assistance with any aspect of our service, our friendly and knowledgeable support team is available 24/7 to assist you.

- Money-Back Guarantee : Your satisfaction is our top priority. iResearchNet offers a money-back guarantee, ensuring that if for any reason you are not satisfied with the work delivered, you are entitled to a refund. This policy underscores our confidence in the quality of our services and our dedication to your success.

Choosing iResearchNet for your research paper writing needs means partnering with a trusted provider committed to excellence, innovation, and customer satisfaction. Our unparalleled blend of expert writers, top-quality work, customized solutions, affordability, timely delivery, 24/7 support, and a money-back guarantee makes us the ideal choice for students and researchers seeking to elevate their academic performance.

How It Works: iResearchNet’s Streamlined Process

Navigating the process of obtaining a top-notch research paper has never been more straightforward, thanks to iResearchNet’s streamlined approach. Our user-friendly system ensures that from the moment you decide to place your order to the final receipt of your custom-written paper, every step is seamless, transparent, and tailored to your needs. Here’s how our comprehensive process works:

- Place Your Order : Begin your journey to academic success by visiting our website and filling out the order form. Here, you’ll provide details about your research paper, including the topic, academic level, number of pages, formatting style, and any specific instructions or requirements. This initial step is crucial for us to understand your needs fully and match you with the most suitable writer.

- Make Payment : Once your order details are confirmed, you’ll proceed to the payment section. Our platform offers a variety of secure payment options, ensuring that your transaction is safe and hassle-free. Our transparent pricing policy means you’ll know exactly what you’re paying for upfront, with no hidden fees.

- Choose Your Writer : After payment, you’ll have the opportunity to choose a writer from our team of experts. Our writers are categorized based on their fields of expertise, academic qualifications, and customer feedback ratings. This step empowers you to select the writer who best matches your research paper’s requirements, ensuring a personalized and targeted approach to your project.

- Receive Your Work : Our writer will commence work on your research paper, adhering to the specified guidelines and timelines. Throughout this process, you’ll have the ability to communicate directly with your writer, allowing for updates, revisions, and clarifications to ensure the final product meets your expectations. Once completed, your research paper will undergo a thorough quality check before being delivered to you via your chosen method.

- Free Revisions : Your satisfaction is our priority. Upon receiving your research paper, you’ll have the opportunity to review the work and request any necessary revisions. iResearchNet offers free revisions within a specified period, ensuring that your final paper perfectly aligns with your academic requirements and expectations.

Our process is designed to provide you with a stress-free experience and a research paper that reflects your academic goals. From placing your order to enjoying the success of a well-written paper, iResearchNet is here to support you every step of the way.

Our Extras: Enhancing Your iResearchNet Experience

At iResearchNet, we are committed to offering more than just standard research paper writing services. We understand the importance of providing a comprehensive and personalized experience for each of our clients. That’s why we offer a range of additional services designed to enhance your experience and ensure your academic success. Here are the exclusive extras you can benefit from:

- VIP Service : Elevate your iResearchNet experience with our VIP service, offering you priority treatment from the moment you place your order. This service ensures your projects are given first priority, with immediate attention from our team, and direct access to our top-tier writers and editors. VIP clients also benefit from our highest level of customer support, available to address any inquiries or needs with utmost urgency and personalized care.

- Plagiarism Report : Integrity and originality are paramount in academic writing. To provide you with peace of mind, we offer a detailed plagiarism report with every research paper. This report is generated using advanced plagiarism detection software, ensuring that your work is unique and adheres to the highest standards of academic honesty.

- Text Messages : Stay informed about your order’s progress with real-time updates sent directly to your phone. This service ensures you’re always in the loop, providing immediate notifications about key milestones, writer assignments, and any changes to your order status. With this added layer of communication, you can relax knowing that you’ll never miss an important update about your research paper.

- Table of Contents : A well-organized research paper is key to guiding readers through your work. Our service includes the creation of a detailed table of contents, meticulously structured to reflect the main sections and subsections of your paper. This not only enhances the navigability of your document but also presents your research in a professional and academically appropriate format.

- Abstract Page : The abstract page is your research paper’s first impression, summarizing the essential points of your study and its conclusions. Crafting a compelling abstract is an art, and our experts are skilled in highlighting the significance, methodology, results, and implications of your research succinctly and effectively. This service ensures that your paper makes a strong impact from the very beginning.

- Editor’s Check : Before your research paper reaches you, it undergoes a final review by our team of experienced editors. This editor’s check is a comprehensive process that includes proofreading for grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors, as well as ensuring that the paper meets all your specifications and academic standards. This meticulous attention to detail guarantees that your paper is polished, professional, and ready for submission.

To ensure your research paper is of the highest quality and ready for submission, it undergoes a rigorous editor’s check. This final review process includes a thorough examination for any grammatical, punctuation, or spelling errors, as well as a verification that the paper meets all your specified requirements and academic standards. Our editors’ meticulous approach guarantees that your paper is polished, accurate, and exemplary.

By choosing iResearchNet and leveraging our extras, you can elevate the quality of your research paper and enjoy a customized, worry-free academic support experience.

A research paper is an academic piece of writing, so you need to follow all the requirements and standards. Otherwise, it will be impossible to get the high results. To make it easier for you, we have analyzed the structure and peculiarities of a sample research paper on the topic ‘Child Abuse’.

The paper includes 7300+ words, a detailed outline, citations are in APA formatting style, and bibliography with 28 sources.

To write any paper you need to write a great outline. This is the key to a perfect paper. When you organize your paper, it is easier for you to present the ideas logically, without jumping from one thought to another.

In the outline, you need to name all the parts of your paper. That is to say, an introduction, main body, conclusion, bibliography, some papers require abstract and proposal as well.

A good outline will serve as a guide through your paper making it easier for the reader to follow your ideas.

I. Introduction

Ii. estimates of child abuse: methodological limitations, iii. child abuse and neglect: the legalities, iv. corporal punishment versus child abuse, v. child abuse victims: the patterns, vi. child abuse perpetrators: the patterns, vii. explanations for child abuse, viii. consequences of child abuse and neglect, ix. determining abuse: how to tell whether a child is abused or neglected, x. determining abuse: interviewing children, xi. how can society help abused children and abusive families, introduction.

An introduction should include a thesis statement and the main points that you will discuss in the paper.

A thesis statement is one sentence in which you need to show your point of view. You will then develop this point of view through the whole piece of work:

‘The impact of child abuse affects more than one’s childhood, as the psychological and physical injuries often extend well into adulthood.’

Child abuse is a very real and prominent social problem today. The impact of child abuse affects more than one’s childhood, as the psychological and physical injuries often extend well into adulthood. Most children are defenseless against abuse, are dependent on their caretakers, and are unable to protect themselves from these acts.

Childhood serves as the basis for growth, development, and socialization. Throughout adolescence, children are taught how to become productive and positive, functioning members of society. Much of the socializing of children, particularly in their very earliest years, comes at the hands of family members. Unfortunately, the messages conveyed to and the actions against children by their families are not always the positive building blocks for which one would hope.

In 2008, the Children’s Defense Fund reported that each day in America, 2,421 children are confirmed as abused or neglected, 4 children are killed by abuse or neglect, and 78 babies die before their first birthday. These daily estimates translate into tremendous national figures. In 2006, caseworkers substantiated an estimated 905,000 reports of child abuse or neglect. Of these, 64% suffered neglect, 16% were physically abused, 9% were sexually abused, 7% were emotionally or psychologically maltreated, and 2% were medically neglected. In addition, 15% of the victims experienced “other” types of maltreatment such as abandonment, threats of harm to the child, and congenital drug addiction (National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, 2006). Obviously, this problem is a substantial one.

In the main body, you dwell upon the topic of your paper. You provide your ideas and support them with evidence. The evidence include all the data and material you have found, analyzed and systematized. You can support your point of view with different statistical data, with surveys, and the results of different experiments. Your task is to show that your idea is right, and make the reader interested in the topic.

In this example, a writer analyzes the issue of child abuse: different statistical data, controversies regarding the topic, examples of the problem and the consequences.

Several issues arise when considering the amount of child abuse that occurs annually in the United States. Child abuse is very hard to estimate because much (or most) of it is not reported. Children who are abused are unlikely to report their victimization because they may not know any better, they still love their abusers and do not want to see them taken away (or do not themselves want to be taken away from their abusers), they have been threatened into not reporting, or they do not know to whom they should report their victimizations. Still further, children may report their abuse only to find the person to whom they report does not believe them or take any action on their behalf. Continuing to muddy the waters, child abuse can be disguised as legitimate injury, particularly because young children are often somewhat uncoordinated and are still learning to accomplish physical tasks, may not know their physical limitations, and are often legitimately injured during regular play. In the end, children rarely report child abuse; most often it is an adult who makes a report based on suspicion (e.g., teacher, counselor, doctor, etc.).

Even when child abuse is reported, social service agents and investigators may not follow up or substantiate reports for a variety of reasons. Parents can pretend, lie, or cover up injuries or stories of how injuries occurred when social service agents come to investigate. Further, there is not always agreement about what should be counted as abuse by service providers and researchers. In addition, social service agencies/agents have huge caseloads and may only be able to deal with the most serious forms of child abuse, leaving the more “minor” forms of abuse unsupervised and unmanaged (and uncounted in the statistical totals).

While most laws about child abuse and neglect fall at the state levels, federal legislation provides a foundation for states by identifying a minimum set of acts and behaviors that define child abuse and neglect. The Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), which stems from the Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003, defines child abuse and neglect as, at minimum, “(1) any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, or exploitation; or (2) an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk or serious harm.”

Using these minimum standards, each state is responsible for providing its own definition of maltreatment within civil and criminal statutes. When defining types of child abuse, many states incorporate similar elements and definitions into their legal statutes. For example, neglect is often defined as failure to provide for a child’s basic needs. Neglect can encompass physical elements (e.g., failure to provide necessary food or shelter, or lack of appropriate supervision), medical elements (e.g., failure to provide necessary medical or mental health treatment), educational elements (e.g., failure to educate a child or attend to special educational needs), and emotional elements (e.g., inattention to a child’s emotional needs, failure to provide psychological care, or permitting the child to use alcohol or other drugs). Failure to meet needs does not always mean a child is neglected, as situations such as poverty, cultural values, and community standards can influence the application of legal statutes. In addition, several states distinguish between failure to provide based on financial inability and failure to provide for no apparent financial reason.

Statutes on physical abuse typically include elements of physical injury (ranging from minor bruises to severe fractures or death) as a result of punching, beating, kicking, biting, shaking, throwing, stabbing, choking, hitting (with a hand, stick, strap, or other object), burning, or otherwise harming a child. Such injury is considered abuse regardless of the intention of the caretaker. In addition, many state statutes include allowing or encouraging another person to physically harm a child (such as noted above) as another form of physical abuse in and of itself. Sexual abuse usually includes activities by a parent or caretaker such as fondling a child’s genitals, penetration, incest, rape, sodomy, indecent exposure, and exploitation through prostitution or the production of pornographic materials.

Finally, emotional or psychological abuse typically is defined as a pattern of behavior that impairs a child’s emotional development or sense of self-worth. This may include constant criticism, threats, or rejection, as well as withholding love, support, or guidance. Emotional abuse is often the most difficult to prove and, therefore, child protective services may not be able to intervene without evidence of harm to the child. Some states suggest that harm may be evidenced by an observable or substantial change in behavior, emotional response, or cognition, or by anxiety, depression, withdrawal, or aggressive behavior. At a practical level, emotional abuse is almost always present when other types of abuse are identified.

Some states include an element of substance abuse in their statutes on child abuse. Circumstances that can be considered substance abuse include (a) the manufacture of a controlled substance in the presence of a child or on the premises occupied by a child (Colorado, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Virginia); (b) allowing a child to be present where the chemicals or equipment for the manufacture of controlled substances are used (Arizona, New Mexico); (c) selling, distributing, or giving drugs or alcohol to a child (Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, and Texas); (d) use of a controlled substance by a caregiver that impairs the caregiver’s ability to adequately care for the child (Kentucky, New York, Rhode Island, and Texas); and (e) exposure of the child to drug paraphernalia (North Dakota), the criminal sale or distribution of drugs (Montana, Virginia), or drug-related activity (District of Columbia).

One of the most difficult issues with which the U.S. legal system must contend is that of allowing parents the right to use corporal punishment when disciplining a child, while not letting them cross over the line into the realm of child abuse. Some parents may abuse their children under the guise of discipline, and many instances of child abuse arise from angry parents who go too far when disciplining their children with physical punishment. Generally, state statutes use terms such as “reasonable discipline of a minor,” “causes only temporary, short-term pain,” and may cause “the potential for bruising” but not “permanent damage, disability, disfigurement or injury” to the child as ways of indicating the types of discipline behaviors that are legal. However, corporal punishment that is “excessive,” “malicious,” “endangers the bodily safety of,” or is “an intentional infliction of injury” is not allowed under most state statutes (e.g., state of Florida child abuse statute).

Most research finds that the use of physical punishment (most often spanking) is not an effective method of discipline. The literature on this issue tends to find that spanking stops misbehavior, but no more effectively than other firm measures. Further, it seems to hinder rather than improve general compliance/obedience (particularly when the child is not in the presence of the punisher). Researchers have also explained why physical punishment is not any more effective at gaining child compliance than nonviolent forms of discipline. Some of the problems that arise when parents use spanking or other forms of physical punishment include the fact that spanking does not teach what children should do, nor does it provide them with alternative behavior options should the circumstance arise again. Spanking also undermines reasoning, explanation, or other forms of parental instruction because children cannot learn, reason, or problem solve well while experiencing threat, pain, fear, or anger. Further, the use of physical punishment is inconsistent with nonviolent principles, or parental modeling. In addition, the use of spanking chips away at the bonds of affection between parents and children, and tends to induce resentment and fear. Finally, it hinders the development of empathy and compassion in children, and they do not learn to take responsibility for their own behavior (Pitzer, 1997).