My English Language

English language resources for efl students and teachers.

Syllables and Stress

Syllables and stress are two of the main areas of spoken language. Pronouncing words with the stress on the correct syllables will help you improve your spoken English, make your sentences easier to understand and help you sound more like a native speaker .

English syllables are stress-timed. English is classed as a ‘stress-based’ language, which means the meanings of words can be altered significantly by a change in word stress and sentence stress. This is why it is important to learn how to use word stress in English and develop an understanding of sentence stress and English stress patterns.

The English language is heavily stressed with each word divided into syllables. Here are some examples of English words with different numbers of syllables. These sets of words are followed by a series of examples using the correct stress placement:

Words with one syllable

The, cold, quite, bed, add, start, hope, clean, trade, green, chair, cat, sign, pea, wish, drive, plant, square, give, wait, law, off, hear, trough, eat, rough, trout, shine, watch, for , out, catch, flight, rain, speech, crab, lion, knot, fixed, slope, reach, trade, light, moon, wash, trend, balm, walk, sew, joke, tribe, brooch

Words with two syllables

Party, special, today, quiet, orange, partner, table, demand, power, retrieve, doctor , engine, diet, transcribe, contain, cabbage , mountain, humour, defend, spatial, special, greedy, exchange, manage, carpet, although, trophy, insist, tremble, balloon, healthy, shower, verbal, business, mortgage, fashion, hover, butcher, magic, broken

Words with three syllables

Fantastic, energy, expensive, wonderful, laughable, badminton, idiot, celery, beautiful, aggression, computer, journalist, horrify , gravity, temptation, dieting, trampoline, industry, financial , distinguished, however, tremendous, justify, inflation, creation, injustice, energise, glittering, tangible, mentalise, laughable, dialect, crustacean, origin

Words are made up of syllables – image source

Words with four syllables

Understanding, indecisive, conversation , realistic, moisturising, American , psychology, gregarious, independence, affordable, memorandum, controversial, superior, gymnasium, entrepreneur, traditional, transformation, remembering , establishment, vegetation, affectionate, acupuncture, invertebrate

Words with five syllables

Organisation, uncontrollable, inspirational, misunderstanding , conversational, opinionated, biological, subordination, determination, sensationalist, refrigerator, haberdashery, hospitality, conservatory, procrastination, disobedience, electrifying, consideration, apologetic, particularly, compartmentalise, hypochondria

Words with six syllables

Responsibility, idiosyncratic, discriminatory, invisibility, capitalisation, extraterrestrial, reliability, autobiography, unimaginable, characteristically, superiority, antibacterial, disciplinarian, environmentalist, materialism, biodiversity, criminalisation, imaginatively, disobediently

Words with seven syllables

Industrialisation, multiculturalism, interdisciplinary, radioactivity, unidentifiable, environmentalism, individuality, vegetarianism , unsatisfactorily, electrocardiogram

English Stress Patterns

When thinking about syllables and stress in English, usually we find that one syllable of a word is stressed more than the others. There are always one or more stressed syllables within a word and this special stress placement helps words and sentences develop their own rhythm .

Syllables and stress patterns in English help to create the sounds , pronunciations and rhythms that we hear all around us.

Word Stress in English

We come to recognise these English syllables and stress patterns in conversations in real life interactions and on the radio and television . Using the correct stressed syllables within a word is an important part of speech and understanding.

Pronouncing words with the right word stress will make your language sound more natural to native speakers. Here are some words from the previous lists with the stressed syllable in bold:

Two syllable words stress patterns:

Qui et, par ty, spe cial, to day , or ange, part ner, ta ble, de mand , po wer, re trieve , en gine, di et, gree dy, ex change , man age, car pet, al though, re lax, com fort

Three syllable words stress patterns:

Fan tas tic, en ergy, ex pen sive, ag gre sion, won derful, laugh able, bad minton, cel ery, temp ta tion, trampo line, in dustry, din tin guished, fi nan cial, how ev er, tre men dous, li brary

Four syllable words stress patterns:

Under stand ing, inde cis ive, conver sat ion, rea l is tic, mois turising, Am er ican, psy cho logy, inde pen dence, entrepren eur, transfor ma tion, fas cinating, com fortable

Five syllable words stress patterns:

Uncon troll able, inspir at ional, misunder stand ing, conver sat ional, o pin ionated, bio log ical, alpha bet ical, subordi nat ion, re fri gerator, hab erdashery, hospi tal ity

Six syllable words stress patterns:

Responsi bil ity, idiosyn crat ic, invisi bil ity, capitali sat ion, dis crim inatory or discrimi nat ory, antibac ter ial, superi or ity, autobi og raphy, ma ter ialism, biodi ver sity, criminalis at ion, i mag inatively,

Seven syllable words stress patterns:

Industriali sat ion, multi cul turalism, interdisci plin ary, radioact iv ity, uni den tifiable, environ men talism, individu al ity, vege tar ianism, unsatis fac torily, electro card iogram

Image source

Syllables and Stress Patterns in English Speech

Using clear syllables and stress patterns is an important part of speech. The correct word stress in English is crucial for understanding a word quickly and accurately.

Even if you cannot hear a word well and are not familiar with the context, you can often still work out what the word is, simply from listening to which syllable is stressed.

In the same way, if a learner pronounces a word differently from the accepted norm, it can be hard for a native speaker to understand the word. The word or sentence might be grammatically correct, but if they have used the wrong (or an unexpected) stress pattern or the wrong stressed syllables, it could make it unintelligible to a native.

English Word Stress Rules

Here are some general rules about word stress in English:

- Only vowel sounds are stressed (a,e,i,o,u).

- A general rule is that for two syllable words, nouns and adjectives have the stress on the first syllable, but verbs have the stress on the second syllable.

For example: ta ble (noun), spec ial (adjective), de mand (verb).

- Words ending in ‘ic’, ‘tion’ or ‘sion’ always place their stress on the penultimate (second to last) syllable. (e.g. super son ic, At lan tic, dedi ca tion, at ten tion, transfor ma tion, compre hen sion).

- Words ending in ‘cy’, ‘ty’, ‘gy’ and ‘al’ always place their stress on the third from last syllable. (e.g. acc oun tancy, sin cer ity, chro nol ogy, inspi rat ional, hypo the tical).

- Words ending in ‘sm’ with 3 or fewer syllables have their stress on the first syllable (e.g. pri sm, schi sm, aut ism, bot ulism, sar casm) unless they are extensions of a stem word. This is often the case with words ending ‘ism’.

- Words ending in ‘ism’ tend to follow the stress rule for the stem word with the ‘ism’ tagged onto the end (e.g. can nibal = can nibalism, ex pre ssion = ex pre ssionism, fem inist = fem inism, oppor tun ist = oppor tun ism).

- Words ending in ‘sm’ with 4 or more syllables tend to have their stress on the second syllable (e.g. en thu siasm, me ta bolism).

Words ending in ‘ous’

- Words ending in ‘ous’ with 2 syllables have their stress on the first syllable (e.g. mon strous, pi ous, an xious, pom pous, zeal ous, con scious, fa mous, gra cious, gor geous, jea lous, joy ous).

- English words ending in ‘ous’ with 4 syllables usually have their stress on the second syllable (e.g. gre gar ious, a non ymous, su per fluous, an dro gynous, car niv orous, tem pes tuous, lux ur ious, hil ar ious, con tin uous, cons pic uous). There are some exceptions using different stressed syllables, such as sacri leg ious, which stresses the 3rd syllable.

Words ending in ‘ous’ with 3 or more syllables do not always follow a set stress pattern. Here are some common English words with 3 syllables ending in ‘ous’ and their stress placement:

Words ending in ‘ous’ with stress on first syllable

fab ulous, friv olous, glam orous, cal culus, du bious, en vious, scan dalous, ser ious, ten uous, chiv alrous, dan gerous, fur ious

Words ending in ‘ous’ with stress on second syllable

e nor mous, au da cious, fa ce tious, di sas trous, fic ti cious, hor ren dous, con ta gious, am bit ious, cou ra geous

Stress can changing the meaning of a word

Remember, where we place the stress in English can change the meaning of a word . This can lead to some funny misunderstandings – and some frustrating conversations!

Words that have the same spelling but a different pronunciation and meaning are called heteronyms . Here are a few examples of words where the stressed syllable changes the meaning of the word:

The word ‘object’ is an example of an English word that can change meaning depending on which syllable is stressed. When the word is pronounced ‘ ob ject’ (with a stress on the first syllable) the word is a noun meaning an ‘item’, ‘purpose’ or ‘person/thing that is the focus’ of a sentence.

For example:

- She handed the lady a rectangular ob ject made of metal

- He was the ob ject of the dog’s affection

- The ring was an ob ject of high value

- The ob ject of the interview was to find the best candidate for the job

- The ob ject was small and shiny – it could have been a diamond ring!

But if the same word is pronounced ‘ob ject ‘ (with the stress on the second syllable) the word is now a verb , meaning ‘to disagree with’ something or someone.

- They ob ject to his constant lateness

- The man ob ject ed to the size of his neighbour’s new conservatory

- She strongly ob jects to being called a liar

- We ob ject to the buildings being demolished

- No one ob ject ed to the proposal for more traffic lights

Original image source

When the word ‘present’ is pronounced ‘ pre sent’ (with the stress on the first syllable) the word is a noun meaning ‘a gift’ or an adjective meaning ‘here / not absent’.

- She handed him a beautifully wrapped pre sent

- The book was a pre sent from their grandparents

- Everyone was pre sent at the meeting

But when the word is pronounced ‘pre sent’ (with the stress on the second syllable) the word is now a verb meaning ‘to introduce’ something or someone, ‘to show’ or ‘to bring to one’s attention’. It can also be used when talking about presenting a TV or radio show (i.e. to be a ‘presenter’).

- May I pre sent Charlotte Smith, our new store manager

- Bruce Forsyth used to pre sent ‘Strictly Come Dancing’

- I’d like to pre sent my research on the breeding habits of frogs

- They pre sent ed the glittering trophy to the winner

- She was pre sent ed with the Oscar

- This new situation pre sents a problem

To present or a present? Image source

Another example of an English word changing meaning depending on where you place the stress is the word ‘project’. This can be the noun when the stressed syllable is at the start – ‘ pro ject’ (a task).

- They started work on the research pro ject immediately

- She looked forward to her next pro ject – repainting the house

- He enjoyed writing restaurant reviews – it was his current passion pro ject

However, this word becomes a verb when the stressed syllables moves to the end – ‘to pro ject ‘ (to throw/launch, to protrude, to cause an image to appear on a surface, or to come across/make an impression).

- The object was pro ject ed into the air at high velocity

- The film will be pro ject ed onto the screen

- The chimney pro jects 3 metres from the roof

- She always pro jects herself with confidence

Stress patterns in compound words

Compound words are single words made up of two distinct parts. They are sometimes hyphenated. Here are examples of stress patterns in compound words in English:

- Compound nouns have the stress on the first part: e.g. sugar cane, beet root, hen house, trip wire, light house, news paper, port hole, round about, will power

- Compound adjectives and verbs have the stress on the second part: e.g. whole hearted , green- fingered , old- fashioned , to under stand , to in form , to short- change , to over take

English sentence stress

Once you understand word stress in English, you need to think about sentence stress . This means deciding which words to stress as part of the sentence as a whole. Stressed syllables can create a distinctive, rhythmic pattern within a sentence. This is how English stress patterns are related to the rhythm of English and help create the ‘music’ of a language .

English speakers tend to put stress on the most important words in a sentence in order to draw the listener’s attention to them. The most important words are the words that are necessary for the meaning of the sentence. Sentence stress is just as important as word stress for clarity. For example:

‘The cat sat on the mat while eating its favourite food’

The most important words here are: ‘cat’, ‘mat’, ‘eating’ and ‘food’. Even if you only hear those words, you would still be able to understand what is happening in the sentence simply from hearing which words are stressed.

Clearly, it is the nouns and verbs that are the most important parts of the sentence , as these are the ‘content words’ that help with meaning. Content words are usually stressed.

The adjectives , adverbs and conjunctions all add flavour to the sentence, but they are not absolutely necessary to understand the meaning. These ‘helper’ words are usually unstressed.

In our example sentence: ‘The cat sat on the mat while eating its favourite food’ , we have already used the word ‘cat’ so we do not need to emphasise the word ‘its’ (or ‘he/she’ if you want to give the cat a gender), because we already know who is eating the food (i.e. the cat).

English word stress within a sentence

Stress patterns affect words and sentences in English.

The stress on a word (the word stress) is the emphasis placed on that word. In the sentence below, “I never said he ate your chocolate”, the stressed word will change the meaning or implication of the sentence:

Stressing the first word ‘I’ implies that I (the speaker) never said it. It might be true or it might not be true – the point is, I never said it – someone else did.

Stressing the second word ‘never’ emphasises that I never said it. There was never an occasion when I said it (whether it is true or not).

Stressing the third word ‘said’ means that I never said it. He might have eaten your chocolate, but I didn’t say it. I might have thought it, but I never said it out loud (I may only have implied it).

Stressing the fourth word ‘he’ means I didn’t say it was him that ate your chocolate, only that someone did.

Stressing the fifth word ‘ate’ means I didn’t say he had eaten it. Perhaps he took it and threw it away or did something else with it.

Stressing the sixth word ‘your’ means it wasn’t your chocolate he ate – it could have been someone else’s chocolate.

Stressing the seventh word ‘chocolate’ emphases that it was not your chocolate he ate – he ate something else belonging to you.

So the sentence stress in English makes all the difference to the meaning of the whole sentence. The stressed word in the sentence is the one we should pay the most attention to.

Stress placement affects the whole understanding of the English language. This issue is strongly related to the rhythm of English . Getting the right word stress , sentence stress and rhythm leads to the perfect communication of your intended message.

So who ate your chocolate? – image source

Stressed Vowel Sounds and Weak Vowels in English

The necessary words in an English sentence are stressed more by increasing the length and clarity of the vowel sound .

In contrast, the unnecessary words are stressed less by using a shorter and less clear vowel sound. This is called a ‘weak’ vowel sound .

In fact, sometimes the vowel sound is almost inaudible. For example, the letter ‘a’ in English is often reduced to a muffled ‘uh’ sound. Grammarians call this a ‘shwa’ or /ə/.

You can hear this ‘weak’ vowel sound at the start of the words ‘about’ and ‘attack’ and at the end of the word ‘banana’. They can sound like ‘ubout’, ‘uttack’ and ‘bananuh’ when spoken by a native English speaker. The article ‘a’ as a single word is also unstressed and reduced in this way to a weak ‘uh’ sound.

For example: ‘Is there a shop nearby?’ sounds like ‘Is there-uh shop nearby?’ This shwa can also be heard in other instances, such as in the word ‘and’ when it is used in a sentence. For example: ‘This book is for me and you’ can sound sound like ‘This book is for me un(d) you’.

The reason for this weak stress pattern in English is to help the rhythm and speed of speech . Using this weak ‘uh’ sound for the vowel ‘a’ helps the speaker get ready for the next stressed syllable by keeping the mouth and lips in a neutral position.

To pronounce the ‘a’ more clearly would require a greater opening of the mouth, which would slow the speaker down.

The giraffe on the right holds its mouth and lips in a neutral position, ready to speak again – image source

As English is a stress-timed language , the regular stresses are vital for the rhythm of the language , so the vowel sounds of unstressed words in English often get ‘lost’.

In contrast, syllable-timed languages (such as Spanish) tend to work in the opposite way, stressing the vowel sounds strongly, while the consonants get ‘lost’.

Click on the highlighted text to learn more about how English word stress and sentence stress relates to the rhythm of English and intonation in English .

What do you think about syllables and stress in English?

Do you find the syllables and stress patterns a difficult part of learning a new language?

Have you had any funny misunderstandings from stressing the wrong syllable in English? We’d love to hear your stories!

Are there any English words or sentences with odd stressed syllables or difficult stress patterns that you would like advice on?

Can you think of good way to remember or practise correct English word stress and sentence stress?

Do you have any ideas to help EFL students improve their understanding of syllables and stress?

Let us know your thoughts in the comments box.

122 thoughts on “ Syllables and Stress ”

Thank You very Much For this information.. It Helps a lot..

Can you suggest me a song which its lyrics has syllables and pattern?

A good way to practise the syllables and patterns of the English language is to use nursery rhymes and children’s songs. These usually have simple vocabulary so the student can listen to the patterns rather than concentrate on the meaning. http://www.myenglishlanguage.com/2012/08/24/teach-efl-using-nursery-rhymes/

Another useful tool for music fans is pop music from the 1950s and 1960s. Artists like Elvis Presley have simple, effective lyrics that are easy to understand, leaving the listener free to focus on the sounds of the words.

Do any readers have other suggetsions for great listening practice?

Best wishes, Catherine

Thanks so much,its help a lot,now i have cover all the problems on this topic

Hi Utile, I’m really glad you found the article helpful! You might also our articles on Phonology and Speaking/Listening skills 🙂

hi would u tell me how syllables relates to stress , rhythm, and intonation???please

Hi Asmaa, Stress determines which syllable is emphasised the most and the least during speech, rhythm concerns the gaps between syllables during speech and intonation is all about voice pitch (e.g. the voice rises at the end of a sentence to form a question). We will be publishing an article about this topic soon, so watch this space 🙂 Best wishes, Catherine

why is word like nation sounds (sh)?

The ‘tion’ at the end of many English words is thought to have developed from Norman French influence (you can see our History of English section for more about the influence of the Norman Conquest ). English words ending in ‘tion’ are usually pronounced with a ‘sh’ sound but when the letter ‘s’ precedes the ‘tion’, the word is normally pronounced with a ‘ch’ sound. For example, ‘intention’ and ‘position’ have a ‘sh’ sound, but ‘question’ and ‘suggestion’ have a ‘ch’ sound’. I hope this helps 🙂

How would you break procrastination? since I blv the type of English you speak would influence the pronunciation.Which syllable would then be stressed?

Hi Sherin, the word ‘procrastination’ follows the 5 syllable pattern for a word ending in ‘tion’, so the stress comes on the 4th or penultimate syllable – procrastiNAtion (just like the word ‘pronunciAtion’).

thanks for the information.

You’re welcome, Victor. I hope you enjoy the rest of our Phonology section where we have more information on rhythm and intonation in English 🙂 Best wishes, Catherine

Great job here.

Thanks, Dayo. I’m glad you found the article useful.

Hi. which syllable carries the stress in this words? Pronunciation, homogenous, determination, education. Thanks

Hi Olakunle, thanks for your question. These words are pronounced as follows with the stress falling on the letters in bold :

Pronunci a tion, hom o genous, determi na tion, edu ca tion

Ho mo genous (4 syllables) is pronounced with the stress on the second syllable. There is another very similar word, homo gen eous (5 syllables) which is pronounced with the stress on the third syllable. The difference is all in the extra ‘e’.

The words ending in ‘ation’ always have a stress on the penultimate syllable (‘a’)

I hope this helps!

I cant close this page without saying a big thank you. infanct you make me understand this concept to the best of my knowledge.

Thanks for your comment, Idasho – that’s great you found the article so useful. You might also enjoy our Rhythm of English page. 🙂

Thank you so so much. Pls I still need clarity on words ending n with ‘sm” and “ous” Thank you

Thanks for your comment, Amy. We have added a section about words ending in ‘sm’ and ‘ous’ in the English Stress Rules section. I hope this helps.

wow! this is great and really helpful. can there be stress on other parts of speech in a sentence other than nouns and verbs? if yes, examples pls

I’m glad you found the page useful! Normally a sentence stresses the nouns and verbs because these are the most important ‘content’ words. Other words can also be stressed, such as adjectives and adverbs. For example: ‘She bought a big, red car’ – here the adjectives ‘big’ and ‘red’ and the noun ‘car’ would all normally be stressed. In the sentence: ‘They walked quickly to the office’ the adverb ‘quickly’ would also be stressed alongside the verb ‘walked’ and the noun ‘office’.

Structural words, such as conjunctions and prepositions, are rarely stressed. The exception to this is when emphasising a point or correcting information. For example: ‘He cooked chicken and beef for dinner’ – here the most important aspect of the sentence is not that he cooked dinner (that information is expected or already known by the listener), but that he cooked both meats. Stressing the conjunction ‘and’ helps us understand this meaning.

I hope that helps!

hi admin, what about words ending in “ing”. How are they stressed

Hi Ijeoma, the ‘ing’ ending adds another syllable to the word but the ‘ing’ ending is always unstressed. For example: ‘drive’ (1 syllable) becomes ‘ dri ving’ (2 syllables) and ‘ mois turise’ (3 syllables) becomes ‘ mois turising’ (4 syllables).

i really love this. pls what is the stress of the word that end wit MENT example goverment

Thank you very much for this knowledge you imparted on me.. feel like staying here forever

Thanks for your comment, Marcell. I’m really pleased the article helped you! It means a lot to know that learners are benefiting from the content. You might also find our pages on intonation and rhythm of English useful. Good luck with your language learning!

In the word ‘government’ the stress is on the first syllable: gov ernment. This is because ‘ment’ is used here as a suffix and does not change the stress of the original word ( gov ern – gov ernment). ‘Ment’ is often used as a suffix like this to change a verb into a noun, but the new word will always follow its original stress rule – the ‘ment’ is never stressed.

Other examples of this: ‘an nounce ‘ – ‘an nounce ment’, ‘disap point ‘ – ‘disap point ment’, ‘com mit ‘ – ‘com mit ment’, ‘de vel op’ – ‘de vel opment’.

For words ending in ‘ment’ where the ‘ment’ part is not a suffix, the stress can be more difficult to place. Here are some examples: ce ment , fig ment, aug ment , sed iment, par liament, im ped iment, com pliment.

If the word is longer than 2 syllables and the ‘ment’ is not a suffix, the stress will not be on ‘ment’. In words with 2 syllables the stress can be on either the first or last syllable and sometimes this can change the meaning of the word (e.g. ‘ tor ment’ (noun) and ‘to tor ment ‘ (verb).

Can any readers think of any word with more than 2 syllables ending in ‘ment’, where the ‘ment’ is not a suffix and the stress is on the ‘ment’? This is an interesting challenge!

Hope this explanation helps, Abu 🙂

I Really Appreciate These..But According To The Rule,two Syllable Words that is”verb and adjective” Will Have Their stress on the second sylable then why is it GOVern and nt govERN

Hi Ayomide, thanks for your comment! The word ‘govern’ is a verb (‘to govern’) but not an adjective. The related adjective would be ‘governed’. For words with two syllables that are adjectives and verbs the stress will usually be on the second syllable, but this is only a general rule and you will find exceptions.

Some examples of exceptions are: ‘open’ – ‘to open’ (verb) and ‘an open book’ (adjective); ‘better’ – ‘to better’ (verb, ‘to better something’ means to improve on it) and ‘a better book’ (adjective); ‘baby’ – ‘to baby (someone)’ (verb, meaning to pamper/mollycoddle) and ‘a baby sparrow’ (adjective) All these words are also nouns – could this be why they are pronounced on their first syllable? Can anyone think of other two-syllable words that are stressed on the first syllable and are both adjectives and verbs – but are not also nouns?

Thanks……how to divide the word int syllabus

Hi Karima, to divide a word into syllables we break down the word into units of speech. Each syllable contains a vowel sound and the start/end of vowel sounds act as the breaks between syllables. The syllables help in creating the rhythm of the language . It’s worth noting that prefixes and suffixes will always add a syllable (e.g. rewriting = re-writ-ing).

Hi my name is Elizabeth I am confused with the stress placements for these names increase in salary,increase in premium,they contract the dreaded disease at sea,my record was kept in the school,the principal advised the students at assembly

Hi me again can you explain to me about the bound morphemes because i dont understand why they say these words are not examples of bound morphemes . caption,amuse,image

Hi Elizabeth, Thanks for your question. The word ‘increase’ changes its stress placement depending on whether you are using it as as a verb (to in crease ) or a noun (the/an in crease). The verb stresses the second syllable and the noun stresses the first syllable, so this would determine how your first two sentence fragments are stressed. (Incidentally, the stress for the other words here would be sal ary and prem ium) The words ‘contract’ and ‘record’ work in the same way (verbs – ‘to con tract ‘ and ‘to re cord ‘, nouns – ‘a con tract’, ‘a re cord’) In this context, ‘contract’ is a verb, so the stress placement would be: ‘they con tract the dread ed dis ease at sea ‘. In the other sentence, ‘record’ is used as a noun, so the stress placement would be: ‘my re cord was kept at school ‘ The last sentence would have this stress pattern: ‘the prin cipal ad vised the stu dents at as sem bly’. I hope this helps! If you send the full sentences for the first two fragments containing the word ‘increase’ we can determine if they are used as nouns or verbs and therefore the exact stress placement.

Hi again Elizabeth 🙂 A bound morpheme is a word element that cannot stand alone as a word. This includes prefixes and suffixes. Examples of bound morphemes are: ‘re’, ‘pre’, ‘ing’, the pluralising ‘s’, the possessive ‘s’,’er’, est’ and ‘ous’. They can be added to another word to create a new word. For example: pre arrange, re write, copy ing , pencil s , Elizabeth `s , strong er , strong est , danger ous . The words in your question (caption, amuse and image) are not bound morphemes because they can stand alone as words in their own right. I hope this explanation helps!

Thanks so much I have learnt a lot. But how can words such as guarantee, decompose, afternoon, fortunate, inundate, computer, alternate, efficient, galvanize, convocation, habitable, momentary be stressed.

Hi Arinze, I’m glad the page has helped you learn more about syllables and stress 🙂 The words in your list are stressed as follows: guaran tee , decom pose , after noon , for tunate (from the noun ‘ for tune’), in undate, com pu ter, al ternate (verb), al ter nate (adjective), ef fi cient, gal vanize, convo ca tion, ha bitable, mo mentary (from the noun ‘ mo ment’).

How can we stress the words that end with ‘ay’ as in always, ‘lt’ as in result, malt, belt, ‘ce’ as in reproduce, peace, lice, pierce, ‘and’ as in understand, ‘it’ as in permit, vomit …. Hope to hear from you Sir/Ma Thanks

Hi Adebola, Here are the words you requested with the stressed syllable highlighted: al ways, re sult , malt , belt , repro duce , peace , lice , pierce , under stand , per mit (noun), to per mit (verb), vom it. The words with only one syllable (belt, malt, peace, lice, pierce) are irrelevant to the issue of word stress because stress only becomes apparent when there is a contrast with another unstressed syllable within the same word. I hope this helps!

How to stress words or phrases without sending offensive msaage? Please help.

Hi Sara, Are you worried about any words or phrases in particular? If the listener knows you aren’t a native speaker, they will make allowances for any mispronunciations and 99.99% of native speakers won’t be offended if you say something cheeky by mistake, so please don’t worry 🙂

pls help me stress dis words..communicate,investigate,advocate

Hi Taiwo, here is how those words are stressed: com mun icate, in ves tigate, ad vocate

Thanks so much, this really helped me.

I’m glad the page helped, Peace – thanks for taking time to comment 🙂

Please how are words that ends in OR stressed.

Hi Cynthia, Thanks for your question. Words ending in OR usually denote a property of something or someone. For OR words with 2 syllables (e.g. debt or, sail or, auth or, act or, tract or, terr or, error, mirr or, maj or, ten or, don or, sen sor), these nearly always have the stress on the first syllable. One exception is ab hor . It is worth noting that in British English we often have a ‘u’ between the ‘o’ and ‘r’ but American English doesn’t usually have the ‘u’ (e.g. hon our, trem or, pall our, lab our, ard our, glam our, col our).

Words ending in OR that have a root word are stressed the same as the root word. Adding OR to the root is often a way of giving a noun agency. For example: pro ject or, de tect or, gen erator, con duct or, ac cel erator, ad min istrator, rad iator and gov ernor all come from the root verbs: to pro ject , to de tect , to gen erate, to con duct , to ac cel erate, to ad min istrate, to rad iate and to gov ern.

If there is no root word, the stress will often be on the third from last syllable. So if there are 3 syllables in total, it will be on the first syllable e.g. met aphor, mon itor, sen ior). Another example is ‘am bass ador’ with 4 syllables.

You have helped me greatly madam, God bless you

I’m glad you found the page useful – thanks for stopping by!

Thank you so much ..for your very helpful article. Please give us some simple tips on how to perfect the English stress pattern. Almost all the general rules have so many exceptions.

Hi Ralphael, glad you found the page helpful. English is full of exceptions unfortunately, but some simple tips include:

- Stress the most important words in the sentence.

- Modulate your voice to add emotion to important words – don’t keep it flat and monotone.

- Keep stressed syllables slightly longer, higher in pitch and louder than unstressed syllables.

- Identify how many syllables a word has so you can break it up – and remember the stress will fall on a vowel sound.

- Speak clearly and slowly – even without perfect stress patterns, slow and clear voices are much easier to understand.

- Focus on the general rules – you will learn about the exceptions with practice.

- Read and listen to a text at the same time – an audio book with transcript is perfect (also try TV with subtitles) so you can hear how a sentence is pronounced and get used to the sounds and rhythm of English .

God bless you rabbi ..I really wish I am in your college. I have so many questions, some not pertaining to this topic.

Hi, what are relationship between syllables and stress in English language

What is the name of the stress symbol called as in café with the symbol over the (e)? And is it on any keyboard to type? I just noticed it on my sentence above and it was there automatically, how do I get each time I type café?

Hi David, the accent slanting forwards in the word café is called an acute accent (the accent slanting backwards is a grave accent). The right Alt key (sometimes marked Alt Gr) can create this accent when pressed with the e key. The apostrophe key ‘ + e also works in the same way. You can also create the letter e with an acute accent using the shortcut keys Alt + 0233. Let me know if these worked for you!

It didn’t give me what I wanted

I’m sorry you didn’t find the information you needed Felix. Did you have a specific question about syllables and stress you wanted help with?

i have been waiting such an opportunity, thank god it has come; madam, i have been finding it tough to understand stress on my own, though, i got some rules that helps me while dealing with stress like: if a word end with the following; ic, sion, tion, nium, cious, nics, cience, stress mark falls on the second syllable from the end if counting backward eg eduCAtion. stress mark falls on the third syllable from the end if counting backward, these words end with the following; ate, ty, cy, gy. eg, calCUlate. but with all this, i still find it tough to stress most of the polysyllabic words, pls can you help me? words like; educative, agreement,philanthropist, understandable, and several others, i can’t stress them with dictionary aid, pls help me!

Thanks for your message Lorkyaa. The pronunciations for the words you mention are: ed ucative (from the verb ‘to ed ucate’), a gree ment (from ‘to a gree ‘), phil an thropist and under stand able (from ‘to under stand ‘). The word ‘calculate’ is pronounced cal culate with the stress on the first syllable, which is indeed the third from the end!

Hi thanks a lot, it really helped me with some issues

Thank you for the knowledge

Academic has a stress on the second syllable and academic has a stress on the second to last symbol. Academic follows the ic rule. How do I explain that the middle syllable of academy is stressed?

Hi Jenna, We can explain the difference in stress pattern between the adjective ‘academic’ (stress on the penultimate syllable) and its related noun ‘academy’ (stress on 2nd syllable) because these words have different roles in a sentence. Adjectives ending in ‘ic’ will stress the penultimate syllable, but it doesn’t follow that their related nouns will follow this stress pattern. Can any other teachers offer insight into this adjective/noun relationship when it comes to word stress?

Thank you so much. It really helped us. Great job

You’re welcome Sunny, thanks for stopping by 🙂

Such an useful article….concepts are explained so clearly and in a easily understandable way…thanks a lot!! could you throw some light on the stress pattern for the words like chairperson,probably,sentence,insurance,disintegrate,impossible ?

Glad you found it useful, Vani! The stress pattern for these words is as follows: chair person, pro bably, sen tence, in sur ance, dis in tegrate and im poss ible.

Thanks,pls what is the stress word for investigation

Hi Vivian, the word ‘investigation’ has 5 syllables and the stress is placed on the 4th syllable: investi ga tion. The root word here is ‘in ves tigate’ which has stress on the 2nd syllable. The ending ‘ion’ in ‘investigation’ moves the stress to the penultimate syllable.

Good job Catherine, I guess the syllable in accommodation falls on ‘DA’, where does it falls in accommodate? Thanks.

Hi Remi, yes the stress falls on ‘da’ in ‘accommo da tion’ but it falls on the second syllable (‘co’) in ‘a cco mmodate’

I thank God I found this on time

Glad you found the page useful, Promise!

Pls, how can departmental, synonym, university, structure and culture be stress.

Hi Michael, these words are stressed as follows (stressed syllables in bold): depart men tal, syn onym, uni ver sity, struc ture, cul ture

I am glad, thanks a million times for this lesson. I really enjoyed it.

Thanks Catherine, glad i found this article. In this article i learnt that words ending with “ment” like government can be stress on its base word i.e GOvern , but what about Bewilderment?

Hello Tope, glad you found the article useful! Bewilderment also follows this pattern – it is stressed on the second syllable (‘wil’) because the base word is be wil der.

Good contribution, Admin!

Where is the stressed syllable in the word “TRIBALISM”? If asked to underline the stressed syllable, where exactly would the underlining begin and end?

Hi Joseph, the word tribalism is stressed on the first syllable: tri balism

I really appreciate you, I learned a lot

Can you please tell me the real relationship between syllable structure and stress I am missing something out

Hi Thimozana, Stressed syllables are normally longer, louder, clearer and slightly higher in pitch than unstressed syllables. The relationship between syllables and stress will usually follow the patterns explored in this page – for example, nouns with 2 syllables normally have their stress on the first syllable. The English language always has exceptions though, so unfortunately there is no one definitive rule that will work every time.

Hey Catherine, Thank you so much for such a nice explanation. You dedication is superb the way you have been answering the queries of the readers on this platform since 2012. I could read this page continuously for 1 hour without even a single moment of boredom. Hats off to your dedication !!!

Regards Mahender.

Thank you for your kind words, Mahender! I love teaching and helping people understand more about English – hopefully my answers and explanations are useful! It’s great to hear you enjoyed the article so much. Good luck in your language journey!

Am grateful because this article is to rich.. I have been strengthen by this article.

Thanks It really helped

How can I make primary stress in a syllable?

I am want to know more on unstressed vowel sounds and stressed sentence

Hi Yusuff, you might find our page on silent letters useful when learning about unstressed sounds.

I wonder why the word “communicative” stresses on the second syllable.Are there any special rules?

Hi Jocelyn, the word ‘communicative’ comes from the root word ‘communicate’ and keeps the same stress. Both are stressed on the second syllable. Most words that are a variation of another word will continue to be stressed in the same way as their root word.

I need more answer on five syllable words and there primary stress

Thank you very much for this. I really find it helpful.

Please admin do we have five syllable words that have their stress on the fifth syllable? And please can you mention some of the words?

pls list polysyllabic words with stress on penultimate syllable

Thank you for this Great Article…it’s very helpful.

Pls Words ending with “ite”, “phy”, “able”, “ment” can be dressed where?

Please I need a list of five syllable words stressed on the fifth syllables

This is so so helpful! However, I noticed that when words become longer the stress shifts or maybe I am wrong here, look at these examples, forbid – forbidden (do you stress for or bid, transformation – transformational (ma is where the stress fall) right? How about /al-ter-na-ting/?

Hi LG, glad you found the page useful! The longer words will usually have the same stress as their root word, though there are exceptions. In your example, ‘for bid ‘ and ‘for bid den’ both have their stress on the second syllable ‘bid’. ‘Transfor ma tion’ and ‘transfor ma tional’ both have their stress on the third syllable ‘ma’. Words ending in ‘ation’ will stress the ‘a’, instead of their root (e.g. here the root ‘trans form ‘ stresses ‘form’). Your third example, ‘ al ternating’ stresses the first syllable ‘al’, the same as its verb root ‘to al ternate’. There is also an adjective version ‘al ter nate’ which stresses the ‘ter’.

Hi I’m from Nigeria Found dis helpful keep it up

Thanks a lot for this now I can focus on other topics for my JAMB

Thanks for inspiration this articles are very helpful I appreciate

There are three boundary markers: {{angbr IPA|.}} for a syllable break, {{angbr IPA||}} for a minor prosodic break and {{angbr IPA|‖}} for a major prosodic break. The tags ‘minor’ and ‘major’ are intentionally ambiguous. Depending on need, ‘minor’ may vary from a [[foot (prosody)|foot]] break to a break in list-intonation to a continuing–prosodic-unit boundary (equivalent to a comma), and while ‘major’ is often any intonation break, it may be restricted to a final–prosodic-unit boundary (equivalent to a period). The ‘major’ symbol may also be doubled, {{angbr IPA|‖}}, for a stronger break.{{#tag:ref|Russian sources commonly use {{unichar|2E3E|WIGGLY VERTICAL LINE}} (approx. ⌇) for less than a minor break, such as list intonation (e.g. the very slight break between digits in a telephone number).Ž.V. Ganiev (2012) ”Sovremennyj ruskij jazyk.” Flinta/Nauka. A dotted line {{unichar|2E3D|VERTICAL SIX DOTS}} is sometimes seen instead.|group=”note”}}

Hi please be so kind to assist me with the following words i need stress pattern for them for example Character-Ooo Remove? Celebrities’? Currency? Killing? Silly? Waste? Product? Action? Figures? Fight? Please I need to be sure hence I am asking please assist

Hi Sasha, the words in your list are stressed as follows (stress in bold): Cha racter, Re move , Ce leb rities, Cur rency, Kil ling, Si lly, W aste, Pro duct, Ac tion, Fi gures, F ight Note the words ‘waste’ and ‘fight’ only have one syllable.

thanks to this. it helps more than you think

Really helpful ! thanks

I think other site proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and wonderful user genial style and design, let alone the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

Can you give me a list of 2-syllable words that are nouns when stressed on the first syllable and verbs when stressed on the second? example: PROGress and proGRESS.

To my own simple knowledge of syllable and stress, I think when counting where stress is placed in any word we count from right to left not from left to right. For instance : international =should be stressed in NA that’s interNAtional , Now,when counting we will say international is stress in the 3rd syllable that is counting from right hand side to the left hand side. But in your analysis I discovered you counted from left hand side to right hand side which is ought not to be.

Hi Joanne, here are a few more two-syllable words that follow this pattern: record, permit, content, contest, survey, produce, refuse, protest, conflict

Hi Seun, that’s an interesting thought. I think we count from left to right when counting syllables because we read from left to right in English. It would seem counterintuitive to count from right to left for a native English speaker.

My take on compound word stress is that I go by the rule: Stress falls on what you want to point out in context or what defines the compound word

Therefore it is /OLD fashioned/ and /GREEN fingered/ to me as well as /MARIGOLD Avenue/ and /MARIGOLD Street/. This also brings more clarity.

Similar pattern is the /VICE president/, /MASS graves/, /SELF defence/, /GAZA strip/: the first part distinguishes something from a category. So stress falls on part one, unless I want to point out the other part within a specific context (e.g. saying the Gaza Strip has the geographical shape of a strip of land or you want to go to Marigold Avenue, not Marigold Street).

Any idea what rules may be behind doing it differently?

Hi Steve, thanks for your insights. I think the idea of stressing the other way around is to stress the most important part (or the noun) over the extra description (or the adjective). So to take a couple of your examples, the fact that something is a grave or a form of defence is more important than the fact it is a ‘mass’ grave or ‘self’ defence. So the ‘category’ is the most important part because the other part couldn’t exist on its own to describe the subject. It’s such an interesting topic though and people will always disagree on the ‘right’ pronunciation of some words!

thanks alot

Thank you so much. it really helped me, but how do I stress words with tive, able, ry.

This page helped me with a lot of things. I am so glad I found this page, it is clear and detailed. Thank you ma

Hi help me stress this words 1 Beginning 2 Generous 3 Necessary 4 Reasonable 5 Individual 6 Execution 7 Instigation 8 Television

Hi Don, here are the stress patterns for these words: 1 Be gin ning 2 Gen erous 3 Ne cessary 4 Rea sonable 5 Indi vid ual 6 Exe cu tion 7 Insti ga tion 8 Tele vi sion

invaluable resources in this domain, especially non-native learners. I hope in near future to add audio clips!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Linguapress.com

- English grammar

- Advanced reading

- Intermediate reading

- Language games and puzzles

Word stress in Eng lish

Six basic rules of word stress, cor rect ly place the ton ic ac cent on mul ti- syl lable words in eng lish..

The six essential rules of word stress or accentuation in English.

3. the "-ion" rule: strong endings. this rule takes priority over all other rules., prefixes .

Mr. William Archer, after a long list of seemingly arbitrary accentuations in the English language ( America To-Day , p. 193), goes on to say: `But the larger our list of examples, the more capricious does our accentuation seem, the more evidently subject to mere accidents of fashion. There is scarcely a trace of consistent or rational principle in the matter.' It will be the object of the following pages to show that there are principles, and that the `capriciousness' is merely the natural consequences of the fact that there is not one single principle, but several principles working sometimes against each other. (p. 160)

These rules ... are ordered, and apply in a cycle, first to the smallest constituents (that is, lexical morphemes), then to the next larger ones, and so on, until the largest domain of phonetic processes is reached .... essentiallly the same rules apply both inside and outside the word. Thus ... a single cycle of transformational rules ... by repeated application, determines the phonetic structure of a complex form.

Log In 0 The website uses cookies for functionality and the collection of anonymised analytics data. We do not set cookies for marketing or advertising purposes. By using our website, you agree to our use of cookies and our privacy policy . We're sorry, but you cannot use our site without agreeing to our cookie usage and privacy policy . You can change your mind and continue to use our site by clicking the button below. This confirms that you accept our cookie usage and privacy policy.

Free English Lessons

Sentence stress – video.

Download PDF

In this lesson, you can learn about sentence stress in English.

Stress means that you pronounce some syllables more strongly than others. there are many different types of stress in english, and stress is used in many different ways., pronouncing sentence stress correctly will make a big difference to how you pronounce english . you’ll immediately sound clearer and more natural when you speak english., quiz: sentence stress.

Now, test your understanding of the lesson with this 16-question quiz.

You’ll see your score at the end. After you finish, click ‘view questions’ to see the correct answers and explanations.

Quiz Summary

0 of 16 Questions completed

Information

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading…

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You must first complete the following:

0 of 16 Questions answered correctly

Time has elapsed

You have reached 0 of 0 point(s), ( 0 )

Earned Point(s): 0 of 0 , ( 0 ) 0 Essay(s) Pending (Possible Point(s): 0 )

- Not categorized 0%

Well done! You’ve finished!

Maybe you should review the video and/or the script, and try the quiz again?

A good score! Do you understand the questions you got wrong?

A great score! Nice work!

A perfect score! Congratulations!

1 . Question

Look at a short dialogue:

A: “Most milk comes from horses.” B: “No, most milk comes from cows.”

Which word is likely to have more stress than any other?

- Milk (in A's sentence)

- Milk (in B's sentence)

2 . Question

Imagine that you hear: “Did YOU say that?”

The speaker adds extra stress to the word ‘you’. What does this mean? Choose the best option.

- The speaker is surprised, because s/he thought that someone else said that.

- The speaker is surprised, because s/he thinks that you are too shy to say that.

- The speaker cannot believe that anyone said that.

- The speaker is asking whether you said that or not.

3 . Question

Imagine that you hear: “The train left at nine in the MORNING?” The speaker adds extra stress to the word ‘morning’. What does the speaker mean? Choose the best option.

- The speaker thought that the train left at nine in the evening.

- The speaker thought that the train left earlier than nine in the morning.

- The speaker is unhappy that s/he has missed the train.

- The speaker did not know that the train left at nine.

4 . Question

A: “Here’s your key. Your room is on the 14th floor.” B: “There must be some mistake. I asked for a room on the ground floor.”

Which word is likely to have more stress than the others?

5 . Question

Write one word in the space to complete the sentence.

Sentences contain words, which carry the meaning of the sentence are are usually stressed, and grammar words, which connect the parts of the sentence, and are not usually stressed.

6 . Question

You should pronounce stressed syllables more clearly, more slowly, and more than unstressed syllables.

7 . Question

Pronouncing sentence stress well depends on creating clear between stressed and unstressed syllables.

8 . Question

You can add extra stress to a word if you want to emphasise one particular idea, if you want to contrast two ideas, or if you want to correct or someone else.

9 . Question

True or false: if a sentence is used by different people in different contexts, the same words will always be stressed.

10 . Question

True or false: there are other kinds of stress besides sentence stress.

11 . Question

True or false: ‘grammar’ words in a sentence (articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs, etc.) are never stressed.

12 . Question

True or false: practising sentence stress can improve your listening comprehension in English.

13 . Question

In general, which parts of speech are more likely to be content words? Choose as many answers as you think are right.

- Auxiliary verbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

14 . Question

Which words in the following sentence are likely to be grammar words?

“He told me he would be here at ten.”

Choose as many answers as you think are right.

15 . Question

Which words in the following sentence are likely to be content words?

“We need some fruit for breakfast tomorrow.”

16 . Question

Which words are most likely to be stressed in this sentence?

“My sister hasn’t called me for ages.”

- hasn't

1. Introduction to Sentence Stress

Look at a sentence:

- How about we go for a coffee this afternoon?

In this sentence, there are two kinds of words; let’s call them content words and grammar words.

Content words give you the meaning of the sentence. The content words here are go, coffee, this and afternoon. If you don’t hear these words, you won’t understand the sentence.

Grammar words don’t carry meaning. They’re grammatically necessary; they connect the content words together.

Think about it this way: if someone comes up to you and says, “Go coffee this afternoon?” you can understand what they mean, even if it sounds a bit weird.

If someone comes up to you and says, “How about we for a this?” you’ll have no idea what they’re talking about.

So, why are we talking about this? Aren’t we supposed to be talking about sentence stress?

The difference between content words and grammar words is the foundation of sentence stress.

Content words are usually stressed, and grammar words are usually unstressed.

Listen and try to hear the stress.

Can you read the sentence with the stress?

- how about we GO for a COFFEE THIS AFTERNOON?

Let’s look at one more example sentence:

- My phone’s broken, so I’m going to buy a new one.

Which words do you think are content words, and which words are grammar words?

Before you answer, you should know one important point.

Sentence stress is flexible, and the line between content words and grammar words isn’t fixed, so the answers we show you are just the most probable ones; there are other possibilities.

So, think about your sentence, and which words you think are content words or grammar words. Pause the video if you want more thinking time!

Ready? Here’s our suggestion:

- my PHONE’S BROKEN, so i’m GOING to BUY a NEW ONE.

Again, think about it like this: if you hear the content words, you can understand the meaning of the sentence: “phone broken, going buy new one.”

If you hear only the grammar words, it doesn’t make any sense at all: “my so I’m to a.”

By the way, this idea can also really help your English listening.

You can see that you don’t need to hear every word to understand the meaning of a sentence.

If you focus on listening to the stressed words, you can understand someone’s meaning, even if you don’t hear the unstressed grammar words.

Anyway, let’s practice this sentence. Can you say the sentence with the stress?

Okay, now you know the basics about sentence stress. Let’s see what you can do!

2. Recognising and Pronouncing Sentence Stress

Look at three sentences:

- Could you get some bread from the bakery on your way here?

- I heard that the weather’s going to be bad tomorrow.

- He has no idea what he wants to do after he graduates.

In this section, you’re going to find the stressed words in these sentences, and then we’ll practice pronouncing them together.

So, first of all, pause the video, and find the stressed words in these three sentences. Take as much time as you need, and start again when you’re ready.

Okay? Let’s look at our suggested answers. Remember that other answers are possible:

- could you GET some BREAD from the BAKERY on your WAY HERE?

- i HEARD that the WEATHER’S going to be BAD TOMORROW.

- he has NO IDEA WHAT he WANTS to DO AFTER he GRADUATES.

Next, let’s try reading the sentences together. Repeat after me, and pay attention to the stress:

Let’s do the next one:

Let’s try the third sentence:

How was that? Easy? Difficult? Remember that you can go back and review this section as many times as you need to.

You can also adjust the video speed to make it easier or more difficult. For example, if you find it difficult, watch this section again at point seven five or point five speed. Practice at a lower speed until you can pronounce the stress easily. Then, try again at full speed!

Now, to pronounce sentence stress well, you also need to pay attention to the unstressed words in a sentence.

Why is this?

3. Stressed vs. Unstressed Contrast

Here’s a very important point about sentence stress, or any stress .

Stress is about contrast.

You heard before that stress means pronouncing some syllables more loudly, more clearly, and more slowly than others.

That means that stress is relative. To pronounce stress clearly, you need a clear contrast between your stressed and unstressed syllables.

So, when you’re practicing sentence stress, you should pay equal attention to the unstressed words.

Let’s look at an example, using a sentence you saw before:

You need to pronounce the stressed words more strongly, and you need to pronounce the unstressed words at a lower volume and a higher speed.

Often, unstressed words have a weak pronunciation. Knowing how to pronounce weak forms is also important if you want to pronounce sentence stress clearly.

Let’s try something. Read the sentence. Make the stressed words as clear as possible. Exaggerate the stress a little bit.

Pronounce the unstressed words as fast as you can. Try to get a really clear contrast between the stressed and unstressed words.

Listen first, then you try:

Let’s do one more example, with a new sentence. Look at the sentence:

- i HAVEN’T HEARD ANYTHING from them SINCE their WEDDING.

Try reading the sentence.

It’s worth spending some time practicing this contrast: if you can pronounce the contrast between stressed and unstressed sounds clearly, your English will sound much better and more natural.

We were exaggerating the contrast slightly, so that you could hear it clearly. It’s fine to do this while you’re practicing!

You can go back and review this section, or review the previous section and focus on contrast in your pronunciation.

What’s next? Well, you heard before that sentence stress is flexible.

Let’s talk more about that!

4. Shifting Stress and Tonic Stress

Mikey: Hello, what can I get you?

Kae: One chocolate and raspberry muffin and a small americano with milk, please.

M: Sorry, you said a CHOCOLATE and raspberry muffin?

K: That’s right!

M: Here you are!

K: I said a chocolate RASPBERRY muffin.

M: Oh, I am sorry! I thought you said chocolate and STRAWBERRY.

K: Also, is there milk in this coffee?

M: Did you want MILK? I thought you said an americano with SUGAR!

K: No, with MILK!

M: I’ll make you a new one. One cappuccino with milk coming up.

K: No, not CAPPUCINO! AMERICANO!

M: Right, right, just a minute.

Sentence stress is flexible. It doesn’t follow strict rules; instead, it depends on the meaning you want to express.

Sometimes, one idea in your sentence is more important than others. You’ll add extra stress to this idea.

Why does this happen?

One reason is to contradict or correct someone. For example:

M: Buenos Aires is the capital of China.

K: No, Mikey. Buenos Aires is the capital of ARGENTINA. BEIJING is the capital of China.

M: Two plus two is five.

K: No, Mikey. Two plus two is FOUR.

M: Carrots are green.

K: No, Mikey. Carrots are ORANGE.

Another reason to add extra stress is that you want to contrast two ideas. For example:

- i didn’t want CAPPUCINO; i wanted an AMERICANO.

- she doesn’t live in PARIS; she lives in ROME.

- the flight left at TEN? but i thought it left at TWELVE!

Finally, you might add extra stress just to emphasise one idea in your sentence, like this:

- ARE you going to london tomorrow? –> Meaning: I’m emphasising the question, because I want a yes or no answer from you.

- are YOU going to london tomorrow? –> Meaning: I know some other people are going to London, but I want to know if you are going. This stress pattern is often used to show surprise.

- are you going to london TOMORROW? –> Meaning: I know you’re going to London on another day, but I want to know specifically about tomorrow. Again, this suggests that I’m surprised.

In all of these cases, you add extra stress to one word in the sentence.

This doesn’t replace ‘regular’ sentence stress. Instead, it’s like an extra layer on top of it.

In the question Are you going to London tomorrow , the content words going, London and tomorrow are stressed. If you want to add stress to emphasise one idea, then you add this on top of the existing stress.

For example:

- are YOU going to london tomorrow?

In this case, you add ‘regular’ sentence stress to going, London and tomorrow, and ‘extra’ sentence stress to you.

The ‘extra’ stress should be stronger than the ‘regular’ stress. Try it! Repeat after me:

Note that this ‘extra’ stress can be anywhere, including on grammar words.

So now, you know the most important points about sentence stress in English.

Thanks for watching!

Keep practicing your pronunciation with another free lesson from Oxford Online English: English Pronunciation Secrets .

We Offer Video Licensing and Production

Use our videos in your own materials or corporate training, videos edited to your specifications, scripts written to reflect your training needs, bulk pricing available.

Interested?

More English Lessons

English pronunciation lessons.

Spoken English Lessons

- Facebook 145

- Odnoklassniki icon Odnoklassniki 0

- VKontakte 2

- Pinterest 6

- LinkedIn 13

Sentence Stress

Sentence stress is the music of spoken English. Like word stress , sentence stress can help you to understand spoken English, even rapid spoken English.

Sentence stress is what gives English its rhythm or "beat". You remember that word stress is accent on one syllable within a word . Sentence stress is accent on certain words within a sentence .

Most sentences have two basic types of word:

- content words Content words are the keywords of a sentence. They are the important words that carry the meaning or sense—the real content.

- structure words Structure words are not very important words. They are small, simple words that make the sentence correct grammatically. They give the sentence its correct form—its structure.

If you remove the structure words from a sentence, you will probably still understand the sentence.

If you remove the content words from a sentence, you will not understand the sentence. The sentence has no sense or meaning.

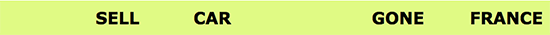

Imagine that you receive this telegram message:

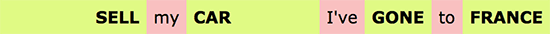

This sentence is not complete. It is not a "grammatically correct" sentence. But you probably understand it. These 4 words communicate very well. Somebody wants you to sell their car for them because they have gone to France . We can add a few words:

The new words do not really add any more information. But they make the message more correct grammatically. We can add even more words to make one complete, grammatically correct sentence. But the information is basically the same :

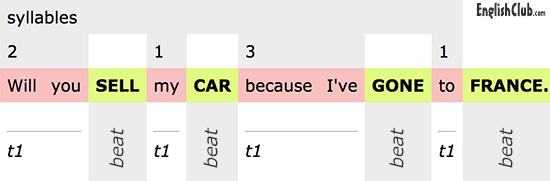

In our sentence, the 4 keywords (sell, car, gone, France) are accentuated or stressed .

Why is this important for pronunciation? It is important because it adds "music" to the language. It is the rhythm of the English language. It changes the speed at which we speak (and listen to) the language. The time between each stressed word is the same.

In our sentence, there is 1 syllable between SELL and CAR and 3 syllables between CAR and GONE. But the time ( t ) between SELL and CAR and between CAR and GONE is the same. We maintain a constant beat on the stressed words. To do this, we say "my" more slowly , and "because I've" more quickly . We change the speed of the small structure words so that the rhythm of the key content words stays the same.

I am a proFESsional phoTOgrapher whose MAIN INterest is to TAKE SPEcial, BLACK and WHITE PHOtographs that exHIBit ABstract MEANings in their photoGRAPHic STRUCture.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

- Signs of Burnout

- Stress and Weight Gain

- Stress Reduction Tips

- Self-Care Practices

- Mindful Living

What Is Stress?

Your Body's Response to a Situation That Requires Attention or Action

Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Elizabeth-Scott-MS-660-695e2294b1844efda01d7a29da7b64c7.jpg)

- Identifying

- Next in How Stress Impacts Your Health Guide How to Recognize Burnout Symptoms

Stress can be defined as any type of change that causes physical , emotional, or psychological strain. Stress is your body's response to anything that requires attention or action.

Everyone experiences stress to some degree. The way you respond to stress, however, makes a big difference to your overall well-being.

Verywell / Brianna Gilmartin

Sometimes, the best way to manage your stress involves changing your situation. At other times, the best strategy involves changing the way you respond to the situation.

Developing a clear understanding of how stress impacts your physical and mental health is important. It's also important to recognize how your mental and physical health affects your stress level.

Watch Now: 5 Ways Stress Can Cause Weight Gain

Signs of stress.

Stress can be short-term or long-term. Both can lead to a variety of symptoms, but chronic stress can take a serious toll on the body over time and have long-lasting health effects.

Some common signs of stress include:

- Changes in mood

- Clammy or sweaty palms

- Decreased sex drive

- Difficulty sleeping

- Digestive problems

- Feeling anxious

- Frequent sickness

- Grinding teeth

- Muscle tension, especially in the neck and shoulders

- Physical aches and pains

- Racing heartbeat

Identifying Stress

What does stress feel like? What does stress feel like? It often contributes to irritability, fear, overwork, and frustration. You may feel physically exhausted, worn out, and unable to cope.

Stress is not always easy to recognize, but there are some ways to identify some signs that you might be experiencing too much pressure. Sometimes stress can come from an obvious source, but sometimes even small daily stresses from work, school, family, and friends can take a toll on your mind and body.

If you think stress might be affecting you, there are a few things you can watch for:

- Psychological signs such as difficulty concentrating, worrying, anxiety, and trouble remembering

- Emotional signs such as being angry, irritated, moody, or frustrated

- Physical signs such as high blood pressure, changes in weight, frequent colds or infections, and changes in the menstrual cycle and libido

- Behavioral signs such as poor self-care, not having time for the things you enjoy, or relying on drugs and alcohol to cope

Stress vs. Anxiety

Stress can sometimes be mistaken for anxiety, and experiencing a great deal of stress can contribute to feelings of anxiety. Experiencing anxiety can make it more difficult to cope with stress and may contribute to other health issues, including increased depression, susceptibility to illness, and digestive problems.

Stress and anxiety contribute to nervousness, poor sleep, high blood pressure , muscle tension, and excess worry. In most cases, stress is caused by external events, while anxiety is caused by your internal reaction to stress. Stress may go away once the threat or the situation resolves, whereas anxiety may persist even after the original stressor is gone.

Causes of Stress

There are many different things in life that can cause stress. Some of the main sources of stress include work, finances, relationships, parenting, and day-to-day inconveniences.

Stress can trigger the body’s response to a perceived threat or danger, known as the fight-or-flight response . During this reaction, certain hormones like adrenaline and cortisol are released. This speeds the heart rate, slows digestion, shunts blood flow to major muscle groups, and changes various other autonomic nervous functions, giving the body a burst of energy and strength.

Originally named for its ability to enable us to physically fight or run away when faced with danger, the fight-or-flight response is now activated in situations where neither response is appropriate—like in traffic or during a stressful day at work.

When the perceived threat is gone, systems are designed to return to normal function via the relaxation response . But in cases of chronic stress, the relaxation response doesn't occur often enough, and being in a near-constant state of fight-or-flight can cause damage to the body.

Stress can also lead to some unhealthy habits that have a negative impact on your health. For example, many people cope with stress by eating too much or by smoking. These unhealthy habits damage the body and create bigger problems in the long-term.

Mental Health in the Workplace Webinar

On May 19, 2022, Verywell Mind hosted a virtual Mental Health in the Workplace webinar, hosted by Amy Morin, LCSW. If you missed it, check out this recap to learn ways to foster supportive work environments and helpful strategies to improve your well-being on the job.

Types of Stress

Not all types of stress are harmful or even negative. Some of the different types of stress that you might experience include:

- Acute stress : Acute stress is a very short-term type of stress that can either be positive or more distressing; this is the type of stress we most often encounter in day-to-day life.

- Chronic stress : Chronic stress is stress that seems never-ending and inescapable, like the stress of a bad marriage or an extremely taxing job; chronic stress can also stem from traumatic experiences and childhood trauma.

- Episodic acute stress : Episodic acute stress is acute stress that seems to run rampant and be a way of life, creating a life of ongoing distress.

- Eustress : Eustress is fun and exciting. It's known as a positive type of stress that can keep you energized. It's associated with surges of adrenaline, such as when you are skiing or racing to meet a deadline.

4 Main Types of Stress:

The main harmful types of stress are acute stress, chronic stress, and episodic acute stress. Acute stress is usually brief, chronic stress is prolonged, and episodic acute stress is short-term but frequent. Positive stress, known as eustress, can be fun and exciting, but it can also take a toll.

Impact of Stress

Stress can have several effects on your health and well-being. It can make it more challenging to deal with life's daily hassles, affect your interpersonal relationships, and have detrimental effects on your health. The connection between your mind and body is apparent when you examine stress's impact on your life.

Feeling stressed over a relationship, money, or living situation can create physical health issues. The inverse is also true. Health problems, whether you're dealing with high blood pressure or diabetes , will also affect your stress level and mental health. When your brain experiences high degrees of stress , your body reacts accordingly.

Serious acute stress, like being involved in a natural disaster or getting into a verbal altercation, can trigger heart attacks, arrhythmias, and even sudden death. However, this happens mostly in individuals who already have heart disease.

Stress also takes an emotional toll. While some stress may produce feelings of mild anxiety or frustration, prolonged stress can also lead to burnout , anxiety disorders , and depression.

Chronic stress can have a serious impact on your health as well. If you experience chronic stress, your autonomic nervous system will be overactive, which is likely to damage your body.

Stress-Influenced Conditions

- Heart disease

- Hyperthyroidism

- Sexual dysfunction

- Tooth and gum disease

Treatments for Stress

Stress is not a distinct medical diagnosis and there is no single, specific treatment for it. Treatment for stress focuses on changing the situation, developing stress coping skills , implementing relaxation techniques, and treating symptoms or conditions that may have been caused by chronic stress.

Some interventions that may be helpful include therapy, medication, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

Press Play for Advice On Managing Stress

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast featuring professor Elissa Epel, shares ways to manage stress. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Psychotherapy

Some forms of therapy that may be particularly helpful in addressing symptoms of stress including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) . CBT focuses on helping people identify and change negative thinking patterns, while MBSR utilizes meditation and mindfulness to help reduce stress levels.

Medication may sometimes be prescribed to address some specific symptoms that are related to stress. Such medications may include sleep aids, antacids, antidepressants, and anti-anxiety medications.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Some complementary approaches that may also be helpful for reducing stress include acupuncture, aromatherapy, massage, yoga, and meditation .

Coping With Stress

Although stress is inevitable, it can be manageable. When you understand the toll it takes on you and the steps to combat stress, you can take charge of your health and reduce the impact stress has on your life.

- Learn to recognize the signs of burnout. High levels of stress may place you at a high risk of burnout. Burnout can leave you feeling exhausted and apathetic about your job. When you start to feel symptoms of emotional exhaustion, it's a sign that you need to find a way to get a handle on your stress.

- Try to get regular exercise. Physical activity has a big impact on your brain and your body . Whether you enjoy Tai Chi or you want to begin jogging, exercise reduces stress and improves many symptoms associated with mental illness.

- Take care of yourself. Incorporating regular self-care activities into your daily life is essential to stress management. Learn how to take care of your mind, body, and spirit and discover how to equip yourself to live your best life.

- Practice mindfulness in your life. Mindfulness isn't just something you practice for 10 minutes each day. It can also be a way of life. Discover how to live more mindfully throughout your day so you can become more awake and conscious throughout your life.

If you or a loved one are struggling with stress, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Cleveland Clinic. Stress .

National institute of Mental Health. I'm so stressed out! Fact sheet .

Goldstein DS. Adrenal responses to stress . Cell Mol Neurobiol . 2010;30(8):1433–1440. doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9606-9

Stahl JE, Dossett ML, LaJoie AS, et al. Relaxation response and resiliency training and its effect on healthcare resource utilization [published correction appears in PLoS One . 2017 Feb 21;12 (2):e0172874]. PLoS One . 2015;10(10):e0140212. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140212

American Heart Association. Stress and Heart Health.

Chi JS, Kloner RA. Stress and myocardial infarction . Heart . 2003;89(5):475–476. doi:10.1136/heart.89.5.475