How to build strong study habits

Here's your chance to become a master of studying! Benefit from our complete guide to building strong study habits that will last a lifetime.

If your habits don't line up with your dream, then you need to either change your habits or change your dream ― John C. Maxwell

Like college students amid their first bad hangover, we swear we’ll never, ever wait to cram at the last moment again. It's the perennial complaint of students everywhere: “...if only I’d started studying sooner, then I wouldn’t be in this mess!”

Well, I have good news for you. Studying effectively doesn't have to be hard!

The secret is building strong study habits .

Habits are grooves carved into your brain’s neural network that eventually become hard-wired, like tracks for a train to run on. Once studying becomes a habit, instead of your brain trudging along muddy hillocky paths, pushing aside thorny bushes, and stepping in cowpats, you glide along smooth rails, getting your study done easily so you can go out and play.

Studies have shown that once an action becomes habitual it takes far less effort for your brain to accomplish it. (Which would FINALLY help you keep your New Year's resolutions! )

Sounds great, right?

Well, it is great. Once you’ve made studying daily a rock-solid habit, you’ll reap the rewards. Daily practice plays to your memory’s strengths, so you’ll be able to get knowledge solidly into your brain with less effort.

However, there are a series of enemies blocking your path: (1) social expectations, aka FOMO ; (2) the desire to save brainpower ; (3) procrastination ; and (4) instant gratification .

If you want to become a study master and cruise smoothly through each study session, you will need to disarm these enemies and use their weapons against them.

We've given you 11 tips on how to do that:

- Anchor new habits to old ones

- Start one micro-habit at a time

- Keep the chain going

- Bribe yourself to study

- Discover your best time to study

- Use peer pressure to study better

- Combat the forces of FOMO

- Be unapologetic about studying

- Give yourself consequences

- Sort out your study environment

- The hidden benefits of daily study habits

Are you ready to enter the dojo and build strong daily study habits? Then welcome, young padawan. It’s time to learn the ways of the study master.

Psst. Improve your mental and physical well-being with these small life-changing habits that take ZERO time ! Also, did you know you can use the Brainscape app to achieve your personal growth goals —like improving your health, wealth, mindset, emotional intelligence, etc.?

1. The enemies of good study habits

The secret to improving study motivation and building good study habits is to realize it’s a game of two halves—you must play both offense and defense. This means you need to both defend against distractions and set your mind to do the work.

Think of your brain as a sort of council. There is more than one politician in Congress, and not all of them have your long-term interests at heart. Sometimes the long-term planner (the frontal cortex) wins the vote, and you go and do things that are hard but will give you rewards later.

Many other times, however, the more ancient, less evolved parts of your brain win the day. This is when the lizard brain or limbic system takes over. These areas respond well to crises—but when there’s no emergency, they seek pleasure.

This is the part that’s in control when, instead of studying, you do whatever is easy and rewards you straight away. Think watching Netflix, playing beer pong, napping, surfing the net, shopping, or eating ice cream.

The issue is that for most people, their frontal cortex has a minority government; It doesn’t have all that much pull. And both inside and outside the brain, the forces arrayed against it are multitudinous.

So now, you’re about to learn which obstacles are in the way of building your study habits and how to defeat them . Let’s get started ...

1.1. Social expectations, aka FOMO

This one is huge, especially if you’re engaged in campus life. The pull to skip studying and do fun things with your friends can be really strong.

Continually resisting temptation puts a heavy load on your willpower.

Many of the best-laid study plans are derailed by some random invitation that spirals into a whole day of distraction. Socializing is important. But there’s a way to prioritize your study so it gets done, and you can still have guilt-free outings with your friends.

1.2. The desire to save brainpower

The brain is an energy-hungry organ . It’s only 2% of your body weight, but even when you’re resting, it demands 20% of your energy.

Thinking, studying, learning—all of these take up brain space. Normally, we prefer to conserve this energy, so it’s a natural thing for us to avoid tasks that are going to exhaust us mentally.

This is why you need systems to get you through the hardest part: actually sitting down to study. Because this avoidance of spending brain energy leads to procrastination!

1.3. Procrastination

A test that’s weeks or months away doesn’t feel urgent. As the test looms closer, however, it’s amazing how many people end up with spotlessly clean kitchens, perfectly ordered sock drawers, and crisply cut lawns.

This is a wonderful tactic to feel productive even when you have far more important things to do.

What’s at work here is a phenomenon called delay discounting . Researchers have found that humans prefer a small reward delivered in the near future over a larger reward they have to wait for. It’s a variation on avoiding delayed gratification.

The ancient parts of your brain HATE spending valuable brain energy on things that are not either a clear and present danger or a pleasurable escape. Back in the days when we were part of the food chain, humans needed their brains to stay focused on urgent problems, like staying alive.

Precious brain juice wasn’t spent on contemplating why apples fell off trees or other non-urgent problems. This urge to prioritize only urgent tasks is still very much alive in us all.

Our brains are very skilled at bringing up seemingly urgent tasks to do instead of hard mental work. Hence the emergence of the spotless fridge and ironed boxer shorts during study week.

1.4. Instant gratification

As mentioned before the ancient, emotion-driven limbic system in our brains craves instant rewards.

In the 1960s, a Stanford professor named Walter Mischel conducted a series of experiments designed to test four-year-old children to their furthest limits.

Mischel put a marshmallow on a table in front of a kid and said they could eat the marshmallow now. Or they could eat two marshmallows if they didn’t eat the marshmallow while he left the room.

Mischel then left the room, leaving a marshmallow sitting in front of a deeply conflicted four-year-old.

This now-famous test became known as the Marshmallow Experiment . While tormenting children for science was entertaining (some children had to scoot their chairs over to the corner, face the wall, and sit on their hands to avoid eating the marshmallow) what was most interesting was the aftermath.

For the next forty years, Mischel followed his participants’ lives. He and other researchers found that the kids who passed the Marshmallow Experiment and could delay gratification had higher SAT scores , better health , and happier relationships .

It turns out that the ability to delay gratification is a key part of living a good life . Those who will do something hard to experience rewards not now, but in the future, succeed in their endeavors.

The issue here is that you’re not a four-year-old child who has to wait five minutes for two marshmallows. (Although to be fair, when you’re four years old, five minutes is a lifetime.)

Navigating life when you’re a student or working means constant pressure from conflicting obligations. You’ll have to make myriad decisions throughout each day. You’ll be resisting temptations, juggling priorities, and managing your energy.

Each time you put off something easy to do something hard, you’re using your willpower. It turns out that willpower is a limited resource and gets exhausted the more you use it.

That’s why if you try to study daily on an ad hoc basis, it’s much more likely to not get done. Then you end up like everyone else: only studying when a test is looming closer, under the tyranny of an impending deadline.

Cramming is an ineffective way to study, which is why (as you’ll find out soon) distraction is an enemy you will need to vanquish to build strong study habits.

2. Strong study habit tips to defeat your enemies

As you may have figured out by now, the phrase "strong study habits" is synonymous with "developing the willpower to do a little bit of work every day because the alternative – cramming – is less effective and even more time-consuming in the long run."

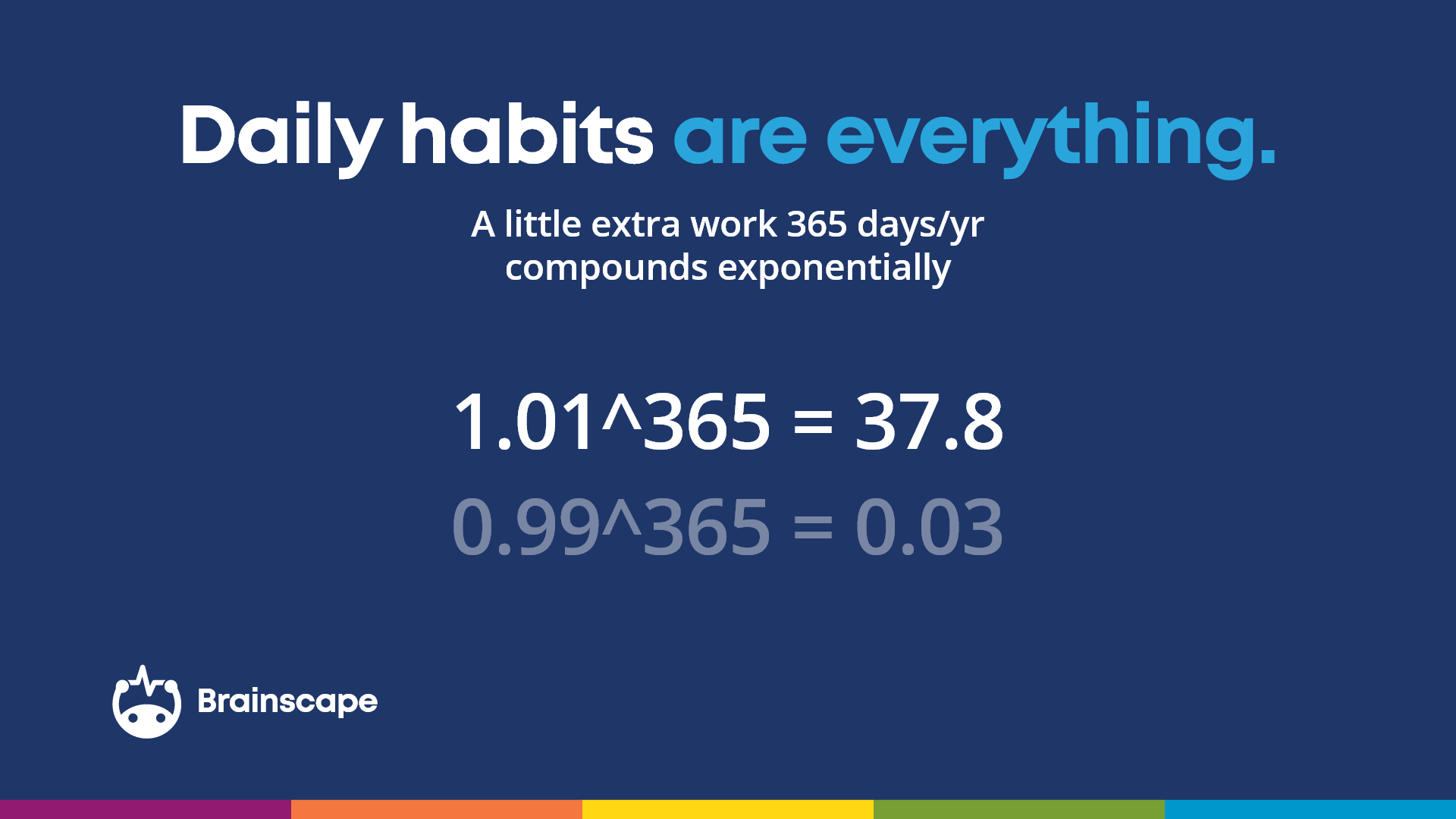

The importance of this realization cannot be underestimated. You can even think of habit formation in terms of this popular mathematical equation:

In other words, doing just a little bit of extra effort every day (no exceptions!) for an entire year will exponentially increase your performance, while slacking off every day will erode your performance or knowledge toward nearly zero, such that you have to start again from scratch (e.g. "cramming") at the last minute.

The good news is that you can fundamentally hack your brain to develop these consistent daily study habits to the point that they become almost effortless.

Below is our list of various forms of mental jiu-jitsu that can help you turn study foes’ weapons against them.

[Try this hack: ' How the benefits of cold showers can change your life ']

Tip 1. Anchor new habits to old ones

As we mentioned above, our brains don’t like to expend lots of energy on hard mental work. But when something becomes a habit, it doesn’t take energy or willpower; you do the thing on autopilot.

The easiest way to make a new habit is to tie it into an existing habit that is already established (otherwise known as an anchor habit.)

For example, if you study better in the morning, then bring out your notes and do your study session while you have your first coffee of the day. The first coffee is your anchor habit, and study is the new habit you’re attaching to it. Quite quickly, you’ll see that studying also becomes automatic.

If evenings are your chosen study time, then build your habit on something you do every evening. For example, you could spend an hour studying every night after dinner, or you could work through your notes before you go to bed each night. Or you could use the Feynman Technique while you’re out walking, exercising, or commuting.

When you tie your new habit with an existing habit, you’re taking advantage of neural pathways that have been already laid down. With consistent practice, your new study habit should start to feel effortless in a couple of weeks.

Tip 2. Start one micro-habit at a time

One of the best ways to guarantee that your new habit won't stick is to take on too big of a challenge at once. So let's nip that one in the bud before we continue.

If your goal is to study every day instead of waiting until the last minute, don't start by promising yourself that you'll study for two hours a day or re-read 5 textbook chapters at a time. That can feel so daunting that you'll end up quitting the first time a major wave of inertia hits you.

Instead, maybe just commit to studying one 10-flashcard round in Brainscape every day, or to making digital flashcards for just one small textbook lesson every day. As long as you have broken up your studying into bite-sized milestones, it will be much easier to develop these habits and stay motivated to study .

Admittedly, tiny daily study sessions might not initially be enough to prevent your need to cram more at the last minute. But at least you're establishing real habits, and you can always add to your goals once your small starter goals have begun to stick.

Tip 3. Keep the chain going

Another hack for building strong study habits comes from comedian Jerry Seinfeld. For years, Seinfeld would write a joke every day, no matter what was going on in his life. After many days, this chain of daily practice became its own incentive.

The threat of breaking the chain contributed to his motivation: Seinfeld didn’t want to break the chain, so he continued writing a joke every day. The habit stuck.

You can use apps like Don’t Break the Chain or Done to create a chain for your daily study habit OR you can very simply set study reminders in Brainscape!

Go into the menu in the mobile app, select 'Notifications', and then toggle on 'Streak Reminders'. Those will show up as push notifications on your phone’s home screen, reminding you to stop what you’re doing and put in a quick study round with Brainscape. You can also customize the time of day you’d prefer to receive your reminders!

Additionally, Brainscape's new study metrics page will help you visualize your progress toward your goals, which can serve as a huge motivation.

Tip 4. Bribe yourself to study

You now know there are deep and powerful parts of your brain that crave instant gratification. They are not moved by distant lofty goals. They want something yummy now. So, use this to your advantage.

The idea is to train your brain like it’s one of Pavlov’s dogs. In his foundational experiment, Pavlov was able to connect two stimuli in a dog’s brain : the ringing of a bell, and a bowl of delicious dog food. By the end of Pavlov’s experiment, the connection between the sound of the bell and a meal was so strong, that his dogs would start to salivate when they heard the bell.

You need to make a connection between sitting down to study, and something your brain likes.

It’s time to train your brain with gratification.

Every time you sit down to study, give yourself a treat. Whatever floats your particular boat: whether it’s chocolate, gummy bears, or your favorite TV show. Naked and Afraid anyone? Once you've studied at least 10-15 minutes (of Brainscape flashcards :), give yourself the treat.

Pretty soon, your brain will start to look forward to your study sessions, because you’ll have connected the positive experience (the treat) with studying.

Congratulations! You have created a neural connection in your brain to tie studying together with gummy bears. Science has been achieved.

Tip 5. Discover your best time to study

To build strong habits, it’s very important to study at the same time each day whenever possible. We’re cyclical creatures, and keeping your study schedule regular will cement the habit much more strongly than shifting it around each day.

So when should you study? Are you a morning lark or a night owl ?

Do you feel sharp at 11 am or 7 pm? Do you fade after lunch? Perk up after dinner? Maybe you’re one of those rare birds who wake up at 6 am bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, ready to go...

Everyone has a circadian cycle of sleep and wakefulness. Paying attention to this cycle means you can go to study at times when your energy is optimal. To discover your cycle, spend a week observing yourself ( or read this article ). Look for the times of day or night when you are at your best and able to tackle difficult mental tasks.

Take note of how the time you go to bed affects how you feel in the morning. This is important. Your circadian rhythm means you can get the same eight hours of sleep, but how rested you feel depends a lot on when during the night you take your rest.

Some people can go to bed at midnight and feel great the next day. Others need to go to bed before 10 pm to get a really good night’s sleep. Once you’ve worked out when you function best, note down those times. Use this knowledge to decide when is the best time for you to study .

Tip 6. Use peer pressure to study better

Peer pressure is a powerful force. It makes people do strange things, like wear clothes with brand logos on them or buy $30 drinks at bars.

One of Professor Robert Cialdini’s six powerful elements of human persuasion is a variant of this force. It’s called consistency, and you can use it to persuade yourself into good habits.

Here’s how consistency works. As human beings, we like to appear to be consistent with our fellow humans. So if we tell everyone “I’m a party animal, and the only time I ever study is on the night before a test,” a precedent has been set.

To appear consistent with your peers, you can’t be found going over your lecture notes on a mid-term Wednesday evening.

However, if you tell all your friends about the wonders of studying every day, then you have a different kind of reputation to uphold.

Most people will expend far more effort to avoid embarrassment than they will to achieve a distant goal. So use this knowledge to create social pressure in support of the habits that will make you succeed in life.

Embrace your inner nerd , and ‘own’ the fact that you geek out at a set time each day. Anyone who makes fun of you will find the tables turned during finals week when they’re frantically trying to cram, and you’re relaxed and confident with plenty of time for leisure.

After a few months of daily studying, you’ll find your habits become a part of your identity. Once you see yourself as someone who studies every day, you’ve truly won the battle and created strong study habits.

Tip 7. Combat the forces of FOMO

Always turn your phone and social media notifications OFF when you start your study time. Apps like Freedom and StayFocusd can do this for you on a laptop. Ignorance is the best cure for FOMO—if you don’t know about the other things you could be doing, you can’t be distracted by them.

Tip 8. Be unapologetic about studying

Another way to avoid social pressure is to be unapologetic about how you spend your time. Don’t give an explanation, and people won’t press you.

For example, if someone asks you to hang out during your study time, just say "Nope, I have to study." They don't have to know that your test isn't for another 6 weeks.

Tip 9. Give yourself consequences

Lastly, if you have someone who wants to join your daily study regime, use the power of aversion to cement your study habits.

This is because while rewards are good, bad consequences are an even more powerful way to create habits. Studies show people will go further to avoid pain than gain pleasure .

With your study partner, create awful consequences if you don’t follow through on your daily study. Keep each other accountable, and be ready to enforce the payout if they don’t keep up their side of the bargain. (And be ready to suffer the consequences if you don’t.)

Using a service like Stickk , people have been forced to donate money to their least favorite charity when they don’t complete their goals. Other sites will publish photos of the person naked if they don’t stick to their weight loss goals (whatever gets the job done, right?). You’d better believe that with stakes like that in the game, participants stick to their goals, and so will you.

Tip 10. Sort out your study environment

The last key to creating a rock-solid study habit is controlling your environment. Set reminders for you to start your daily study session. Create a special area dedicated to study, with all the things you’ll need to do the work close at hand.

Put up a calendar so you can see how each day brings you closer to your exam. Use this same calendar to keep track of your chain of daily study sessions.

Make it "convenient" to study often. Keep your books and notes in a place where you can easily and frequently access them. Have your flashcard app on your phone's home screen and in your web browser's "Favorites" bar, so you don’t have to think about what to do first in your study session.

Building a strong study habit is very similar to getting fit. As your brain gets into the habit of working each day at a set time, it gets fitter, and study sessions become more enjoyable.

Tip 11. The hidden benefits of daily study habits

When you defy the enemies of study and build your strong study habit, you’re also doing something else. Something very important. You’re building character.

'Character' has been defined as the ability to complete a task long after the mood in which the decision to do it has left you.

When you keep your promises to yourself, you’re sending yourself an important message about who you are, and what you’re capable of. In doing this, you’re laying the foundation for future success and happiness.

3. Build your study system

We’ve now gone through the two parts of building a strong study habit: defense and offense. It’s time to put it all together.

Here are the habits that go into building a study system that will work for you.

- Choose an existing activity you habitually do at these times and tie it to your new study habit.

- Keep the chain going—maintain a record of your daily sessions, and create an unbroken chain of them.

- Decide on your study treat and bribe yourself with it at the start and end of your session.

- Note the times of day when your brain is sharpest. Choose these as your designated study times.

- Start celebrating your inner nerd. Spread the gospel of daily study to your friends to create a consistent character you have to live up to.

- Push back against FOMO by turning off your phone and staying ignorant of what your friends are doing.

- Be unapologetic when ducking out of social events in order to keep your study habit.

- Choose your accountability partner, and decide on some (very unpleasant) consequences if you don’t follow through on your study plan.

- Set up a special study space with everything you need.

- Prep your study materials and Brainscape flashcards so the first few minutes of study can be done on autopilot

- Study daily to build character

Building strong study habits is ultimately about respecting your long term goals. And if you need help breaking out of a fixed mindset and learning how to stick to the long road, roll with the punches, be a little more patient, and embrace the learning curve, definitely read: ' How to unlock a growth mindset '.

Remind yourself that studying is actually a way of honoring yourself and keeping your promises. Every time you keep your commitments, you’re building your willpower muscle, and this will help you throughout your entire life.

Ayduk, O., Mendoza-Denton, R., Mischel, W., Downey, G., Peake, P. K., & Rodriguez, M. (2000). Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79 (5), 776–792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.776

Cialdini, R. (2016). Pre-suasion: A revolutionary way to influence and persuade. Simon & Schuster.

Doyle, J. R. (2013). Survey of time preference, delay discounting models . Judgment and Decision Making , 8 (2), 116-135.

Gardner, B., & Rebar, A. L. (2019). Habit formation and behavior change . In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology .

Gailliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., Plant, E. A., Tice, D. M., Brewer, L. E., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2007). Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 (2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325

Jarius, S., & Wildemann, B. (2015). And Pavlov still rings a bell: Summarising the evidence for the use of a bell in Pavlov’s iconic experiments on classical conditioning. Journal of neurology , 262 (9), 2177-2178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7858-5

Mischel, W., Ayduk, O., Berman, M. G., Casey, B. J., Gotlib, I. H., Jonides, J., ... & Shoda, Y. (2011). ‘Willpower’ over the life span: Decomposing self-regulation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience , 6 (2), 252-256.

Seeyave, D. M., Coleman, S., Appugliese, D., Corwyn, R. F., Bradley, R. H., Davidson, N. S., ... & Lumeng, J. C. (2009). Ability to delay gratification at age 4 years and risk of overweight at age 11 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 163 (4), 303-308.

Flashcards for serious learners .

College Info Geek

How to Build Good Study Habits: 5 Areas to Focus On

C.I.G. is supported in part by its readers. If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. Read more here.

Growing up, I learned the importance of good study habits early.

I was responsible for writing down my homework assignments each day, checking I had all the right books the night before school, and making flashcards to study spelling or vocab words. If I didn’t stay diligent in these study habits, then I was bound to hear about it from my mom.

Establishing good study habits at an early age paid off. In high school and college, I was able to focus on learning the material instead of learning how to study. I never got bad grades because I forgot to turn in homework, and if I ever did poorly on a test I had no one to blame but myself.

However, I recognize that not everyone has the benefit of learning good study habits early in life. For many people, college is the first time you even have to think about how to study and manage a schedule all on your own.

To bridge the gap, I’ve put together the following guide to good study habits. First, we’ll look at what good study habits are and why they matter. Then, we’ll give some practical examples of good study habits in action (and how they can solve some common academic issues).

What Is a Good Study Habit?

Before we go any further, we need to define what a good study habit is. To start, we should define “habit”.

A habit is an action (or series of actions) that you perform automatically in response to a particular cue. For instance, the sound of your alarm going off might cue the habit of getting out of bed and walking into the kitchen to make coffee (or, for some of us, hitting the snooze button).

But what makes a habit “good”? Generally, we define a good habit as one that helps you achieve your goals and live in line with your values . A bad habit, meanwhile, is detrimental to your goals and values in the long-term (even if it relieves pain or provides pleasure in the short-term).

A good study habit, then, is a habit that helps you achieve your academic objectives while still supporting your broader goals and values.

3 Reasons Good Study Habits Matter

Good study habits matter for three main reasons: focus, grades, and mental health.

Starting with focus, having the right study habits in place frees up your mind to concentrate on the material you’re learning.

Instead of having to think about how to create flashcards, for example, you can focus on using flashcards to learn a new language .

If your study techniques aren’t automatic, meanwhile, they can distract you from the larger work you’re trying to do.

While good study habits won’t automatically raise your GPA , they’ll certainly improve your chances.

As an example, you’re likely to perform better on an exam if you’re in the habit of studying for it over several days (or weeks) instead of the night before.

Mental Health

Most important of all, however, is the benefit good study habits have for your mental health.

No matter how much “raw intelligence” you might have, poor study habits will make college stressful and anxious.

If you aren’t in the habit of starting research papers well in advance, for instance, then you’ll be in for some sleepless, caffeine-fueled nights. But if you habitually start your research papers early, then you can avoid the unnecessary stress that comes from procrastination.

5 Types of Good Study Habits (and How to Build Them)

Originally, this section was going to contain a long list of good study habits. But since we already have an extensive list of study tips , many of which are specific study habits, I decided to do something different.

Instead of listing yet more study tips, I’m going to examine some common college academic struggles that good study habits can help eliminate or avoid. This way, you can get some practical tips for building good study habits and putting them into action.

This section focuses on how to build good study habits, specifically. For a more general overview of how to build good habits, read this .

Study Habits for Doing Better on Exams

Are your exam grades lower than you’d like? If so, your study habits could be the culprit.

When it comes to studying for exams effectively, here are some habits to keep in mind:

Go to Review Sessions

Usually, your professor and/or TA will hold a review session before each exam. This review will only be helpful, however, if you attend it. Therefore, make a habit of going to any scheduled exam review sessions, especially in classes you find difficult.

How to build the habit: This is one of the easier habits on this list to build. All you have to do is put the review session on your calendar and then be sure you go to it. To make this easier, pay attention in class for any announcements of review sessions.

Make and Study Flashcards

If you’re studying for an exam that requires you to memorize lots of information, then flashcards are your friend. In particular, building a habit of daily flashcard review leading up to an exam can help your performance greatly.

How to build the habit: First, be sure you understand the best ways to make and study flashcards .

From there, we recommend using a flashcard app that reminds you to study the cards each day (and focuses your efforts on the cards you struggle with). This is a case where notifications on your phone can be a study aid instead of a distraction.

Study Habits for Writing Better Papers

No matter your major, you’ll have to write a paper at some point in college. And having the right study habits will make the process much easier and less stressful. Here are some study habits that will help you write better papers:

Don’t Procrastinate on Writing

I won’t deny it: I pulled my share of all-nighters in college. And usually, I was staying up late to finish a paper I’d procrastinated on.

While you can certainly write a paper in one night, it’s unlikely to be your best work. Instead, make it a habit to work on your paper a little bit each day in the week before the due date.

How to build the habit: If you’re struggling with procrastination, then read into the science behind why we do it .

From there, consider the stress and pain that will come from writing a paper in one night. Use that as motivation to work on your paper a little bit at a time.

Once you’ve done this for one paper and seen how much better it makes your life, you’ll be more inclined to do it with future papers.

Visit the Writing Center

While procrastination is a common issue with writing papers, you may also struggle with the writing itself. Depending on where you went to high school, in fact, you might never have learned how to write the kind of papers college requires.

If this is the case, get in the habit of visiting your college’s writing center when you’re working on a paper. The staff there would be more than happy to help you improve your writing.

How to build the habit: Going to the writing center is a fairly easy habit to build if you schedule your writing center appointments in advance.

This should be possible at most colleges, and it’s often required during high-demand times such as finals season. Making an appointment in advance adds some external accountability, so you’re more likely to show up.

For more paper writing tips, read this .

Study Habits for Completing Homework Faster

Homework is important for practicing and solidifying the concepts your professor discusses in lectures, but that doesn’t mean you should spend all your time outside of class doing it.

Here are some study habits to help you complete your homework faster, without sacrificing quality:

Schedule Your Homework Time

If you can fit all of your homework into a defined block each day, it will be much easier to get started on it. Plus, knowing that you only have to spend a defined amount of time working will reduce the dread that generally accompanies homework.

How to build the habit: First, find a time each day that’s free of obligations. Evenings will work well for some, while mornings are better for others; it depends on your schedule.

Then, put that block of time on your calendar with the title “Homework Time.” If you like, you can also break that block down into smaller chunks for each of the courses you’re taking.

Next, decide on a study space where you’ll do your homework: dorm room, library, student center, etc. Note that location on your calendar as well.

Finally, treat this block of study time like any other class, meeting, or appointment. If someone tries to schedule something during that time, tell them you already have an obligation.

Focus Completely On Your Work

You’ll get your homework done much faster if you only focus on the assignment at hand. But if you’re checking social media and your phone as your work, the process will take longer overall.

To avoid this issue, make a habit of distraction-free homework. When you’re working on homework, let nothing else fragment your attention.

How to build the habit: First, turn off your phone and put it away. If you can’t do that, then at least take some steps to make it less distracting .

Next, try to work without an internet connection whenever possible. If that isn’t practical, then use an app like Freedom to block distracting sites and apps.

If that still isn’t enough, then you can also try the Pomodoro technique .

Study Habits for Being Less Stressed

As I mentioned earlier, one of the main advantages of good study habits is reduced levels of stress.

Some study habits, in particular, are great at making the studying process less stressful. Here are a couple to try:

Use the Fudge Ratio

Due to something called the planning fallacy , humans are terrible at estimating how long things will take. The fudge ratio is a solution to this problem. It helps you create more accurate time estimates for tasks, using a simple formula that we’ll explain below.

Applying the fudge ratio to your studies will help you be less stressed since you’ll be in the habit of planning more time than you need to do assignments. If you get done early, then you’ll get a great sense of accomplishment. But if something takes the full time you “fudged,” then you won’t be caught off guard.

How to build the habit: To work the fudge ratio into your planning, you’ll need to keep track of how long you think tasks take vs. how long they truly take. Record these numbers somewhere you can review them regularly. For an accurate measure of how long tasks actually take, you can use time-tracking software .

Once you’ve done this for a bit, you can then compare your estimated times to your actual completion times. This will allow you to calculate a literal ratio that you can use to make future time estimates.

To calculate the fudge ratio for a task, use this formula:

Estimated completion time / Actual completion time = Fudge ratio

For instance, if you think it will take you 30 minutes to finish your Intro to Sociology reading but it actually takes you 45, then your fudge ratio for these reading assignments is 45/30 = 1.5. Now, you know that whenever you’re estimating how long reading will take for this class, you should multiply your estimate by 1.5.

Doing this for each class and assignment can be time-consuming. But with time, using the fudge ratio will help you get into the habit of making better time estimates overall. Eventually, you won’t need to do the tracking and math described here.

Not all classes are created equal. Sure, each instructor thinks their class is the most important on your schedule, but we all know that isn’t true. Some classes require more time and effort than others, and how you study should reflect that.

Specifically, you’ll be much less stressed if you prioritize studying the subjects that take the most work.

How to build the habit: During the first couple weeks of the semester, pay attention to how much work each class on your schedule will require. From there, you can decide where to prioritize your attention.

Then, spend most of your study time on the most difficult classes. Of course, you’ll still need to spend some time on your easier classes, but not nearly as much. Doing this will give you more free time and reduce your general stress levels.

Study Habits for the Forgetful

For our final area of habits, we turn to the pernicious problem of forgetting. Whether you’re having trouble remembering homework assignments or even showing up for class, these habits will help.

Keep a List of Your Assignments

If you’re having trouble remembering your assignments, then build the habit of keeping them on a list. This is a classic piece of advice. But if you put it into practice, it can change your life.

How to build the habit: First, decide where you’ll write down your assignments. We’re a big fan of to-do list apps for this purpose. But you could also go analog and use a paper planner. Just make sure it’s something you can easily carry with you to class.

Then, write down assignments as the professor gives them. In many cases, of course, the professor will expect you to refer to the syllabus for homework assignments. So be sure to review your syllabus each week (and bring a copy to class so you can note any changes).

Finally, review your list of assignments at the start of each homework session. As you complete an assignment, cross or check it off the list. With this habit in place, you’ll be much less likely to forget assignments.

Put Your Classes on Your Calendar

Unlike in high school, where your schedule is regimented and closely supervised, college offers more independence. While this can be exciting, it also means greater responsibility. And one of the first responsibilities you’ll face as a college student is showing up for class at the right time.

While simple in theory, it can be challenging to remember the time and location of all of your classes. Especially during the first couple weeks of class. To ensure you don’t forget when and where your classes are, put them on your calendar.

How to build the habit: Leading up to the first week of school, go online and consult the syllabus for each of your classes.

Note the class times and locations, and put that information on your calendar in recurring events. Make sure your calendar is set up to send you event notifications on your phone, and you should be able to remember each class no problem.

With time, of course, you’re likely to memorize you schedule and won’t need to consult the calendar. But having your classes on your calendar will still be helpful for planning, ensuring you don’t schedule a meeting or other event during a class.

If you’ve never set up a digital calendar, check out this guide to using your calendar efficiently in college .

Good Study Habits Aren’t Built in a Day

I hope this article has shown you the importance of good study habits, as well as how to start making them a part of your academic life.

As with any new habit, forming good study habits takes time and focus. For greater odds of success, work on forming one or two of these habits at a time. When they’re a solid part of your routine, you can add new ones.

Habit formation is such a vast topic, there was no way we could cover all the details in one article. For a deep dive into building habits that last, check out our habit-building course:

Building habits isn’t just about discipline; there are real-world steps you can take to set yourself up for success! In this course, you'll learn how to set realistic goals, handle failure without giving up, and get going on the habits you want in your life.

Image Credits: person studying

- Map & Directions

- Class Registration

- MyFNU opens in a new window

- FNU FaceBook-f opens in a new window

- FNU Twitter opens in a new window

- FNU Youtube opens in a new window

- FNU Linkedin opens in a new window

- FNU Instagram opens in a new window

- FNU Tiktok opens in a new window

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- US Military/Veterans

FNU Advising 11 Techniques to Improve Your Study Habits

11 Techniques to Improve Your Study Habits

When it comes to developing good study habits, there is a method to all of the madness. The type of study habits that you’ve come to practice in high school may not work so well in college. However, you can certainly build on those practices to make your study habits more disciplined—because you’ll need to! In college, you’ll have more responsibility, but you’ll also have more independence. For first-time college students, this could be a challenge to balance. That’s why Florida National University (FNU) wants to help prepare all of our students for how they can improve their study habits with these 11 helpful techniques.

Study Habit #1. Find a good studying spot.

This is important. You need to be in an environment with little to no distractions—an environment that will aid in keeping you focused on your assignments. The library has always been a reliable place to get some real academic work done, but if you prefer someplace else, just make sure that you’re set up for success. Your university may have other places on campus that will provide you with a nice little studying spot. While cafeterias may be quite busy, there are some university campus cafeterias that tend to have just enough silence for students to study while they grab a bite to eat.

You might get campus fever and decide to venture outside of your university to get some work done. Many students find little coffee shops with Wi-Fi that will let them sit there all day long for a buying customer. Outdoor parks and recreational centers, even the public library might be a nice change of scenery.

Even study lighting is also important. If you want to preserve your eyesight and maximize your time and energy, then choose lighting that will not cause eye strain or fatigue so you can keep your study session effective at any time of the day.

Establish rules when you’re in your study zone. Let people living with you know that when your door is closed, it means you do not want to be disturbed. Try not to respond to phone calls or texts, this will break your concentration and you will lose focus.

Let’s not forget about your home. No matter the size of your apartment or house, we recommend dedicating a little office space just for studying—away from any distractions.

Study Habit #2. Avoid social media.

Speaking of distractions, nothing can sap away your time for a good 20-30 minutes like good old social media! Emails used to be the necessary evil in order to keep life going, but now people are communicating through social media platforms more than email or even talking on the phone! As a result, it’s pretty common to have a browser tab open just for social media. The problem with this is the alerts! As much as you may try to ignore it, you won’t be satisfied until you follow through with the alert—an alert that will most likely require a reply! In all likelihood, it will end up being a conversation that could’ve waited an hour—and now you’ve just added another 20-30 minutes to your study time! Congratulations!

Study Habit #3. Stay Away From Your Phone.

Distractions also include avoiding your phone. The best thing you can do is either put your phone on silent, turn off the alerts and flip it over so that you can’t even SEE them, or just turn the thing off! If it helps, place the phone out of sight so that you’re not even tempted to check your messages. The world can wait. Your education is a priority and anyone who’s in your circle of friends should understand this. If you are absolutely adamant about keeping your phone nearby in case of an emergency, then allow yourself some study breaks so that you can dedicate a certain amount of time just for checking your alerts and messages.

Study Habit #4. No Willpower? Enlist the Help of an App.

Apps like Focus Booster and AntiSocial have your back!

AntiSocial blocks your access to a selection of websites with a timer that you select.

Focus Booster is a mobile phone app that relies on the Pomodoro Technique, where you work intensively for 25 minutes and then you break for five minutes. The app also includes productivity reports and revenue charts.

Study Habit #5. Take a break and take care of yourself.

Talking a little more about taking breaks, this really shouldn’t be an option. College is hard work, and just like any other kind of job, you deserve a break. Don’t be so hard on yourself. Working until the wee hours of the morning to complete an assignment might be great for that class, but it’s not for you or other academic courses. You MUST take care of yourself in order to give your academic career the attention it deserves. You’re paying to get an education—to learn. Running yourself into the ground without allowing time for your body and mind to rest is unacceptable.

- Ophthalmologists will warn you that you need to remember to blink when working on a computer screen to save your sight. Give your eyes a rest by gazing into the horizon, preferably out of a window with natural light. Did you know that your eyes need exercise, too? Especially in today’s world where we are reading everything at such close distances. Keep your head in a neutral position and with just your eyeballs, look at the ceiling or a tree and try to focus. Go from corner to corner, focusing up, then do the same for the floor. Roll your eyes.

- Your hands also need a break: learn to use the mouse with your other hand, put the keyboard in the most comfortable position, which is actually on your lap. Take a moment to stretch your wrists and fingers.

- Blueberries

And don’t forget to sleep and reboot!

Study Habit #6. Organize lectures notes.

For some students, the best way to organize notes is to ask if you can record your professors’ lectures for a better understanding of the lesson. The best way to do this is to transcribe the recorded lecture notes. This way, you can rewind what you didn’t understand. It also behooves you to revisit those notes—while the material is fresh in your mind and rewrite them in a style that’s more legible and review-friendly. On the day of the exam, you’ll be glad you did.

Fact: it has been proven that information retention is higher when you go over your notes and repeat the lesson after the class is over. Rewriting your lecture notes is going to be one of the most brilliant study techniques to practice. Rewriting will help you remember the context better and reorganizing them in nice outline forces you to comprehend the lesson.

Study Habit #7. Join or create a study group.

Finding fellow students who are struggling to understand the coursework can be comforting. However, joining or creating a study group can be helpful in many ways. Guaranteed someone in your study group can help you through a certain assignment you’re struggling with and you’ll be able to do the same. It’s all about helping each other succeed!

Study Habit #8. Aromatherapy, plants and music.

Science is always tinkering with nature, but in this case, in a simple way, only studying the effects of essential oils and plants on concentration, focus, and memory.

Some studies have shown that lavender has a good effect on memory, however, others have shown that its effect is negligible and in fact, lavender oil and teas are used to relax the body in preparation for sleep. So lavender may calm and center yourself, but for focus, sandalwood and frankincense (also known as Boswellia) have shown much more promising results in most studies.

Plants, in general, have a natural, comforting effect and in their presence, humans tend to have a higher pain tolerance and faster recoveries from hospitalizations. Music, also improves brain function, can help you focus and also eases the pain. Learn more about the benefits of studying with music.

Study Habit #9. Leave time for the last-minute review.

Here are where well-organized lecture notes come into play. Always, always leave time for the last-minute review. Here, we’re exercising the tried and true memory game. This is a technique that most students apply as one study habit. That’s just impossible for the amount of college work you’ll be taking on, but it can work quite well as a last-minute review—only if you have good notes!

Better still, ff you can pair reviewing your notes with a good night’s sleep, then you will significantly improve your ability to retain more information. Just know that studying when you’re sleepy is ineffective. If your body is telling you that you’re tired, then have a nap or go to bed early. A good night’s sleep is another technique to use that will help you understand and remember information better.

If you’re finding that you are getting stressed out or tired, reflect back on your study schedule and priorities. Make sure that you have dedicated time for rest and de-stressing activities as well.

Study Habit #10. Understand Your Best Learning Style

It’s important to know that there are many different styles of learning and each person will retain information better in different ways.

- Visual learners who learn best when pictures, images, and spatial understanding is used.

- Auditory learners who prefer using music, sounds or both.

- Kinesthetic learners actually use a more physical style of learning through using the body, sense of touch and hands.

- Logical learners need to use reasoning, logic, and systems.

- Verbal learners will prefer using words in writing and speech.

- Social learners will thrive in learning with other people or in groups.

- Solitary learners are able to learn best when alone.

Think about which style of learning works best for you, and it will help you determine how to study, where to study when to study and other important factors like what study aids you should use and be aware of, and knowing what things may distract you while you are trying to study.

Study Habit #11. Make Study Time a Part of Your Daily Routine

If cramming all of your study time into a few long days isn’t working for you then it’s time to try something new and less stressful. What you do every day is more important than what you do occasionally, so make time for studying every single day, with or without exams coming up.

Consistency is key and once you start getting into good study habits, so make it a routine that you will be able to maintain throughout the school year.

When it becomes part of your schedule, you don’t need to find the time, you’ve made time for your study sessions each month. Don’t forget to also check your schedule for the week or month, and consider your personal commitments: chores, must-attend activities, and appointments. All you need to do now is to stay committed to your new study schedule.

Make studying your priority and place these sessions when you’re at your peak performance times to make them extra effective. Some people work best in the mornings, and others, at night. Experiment with this and don’t assume that because you wake early you should study early, but instead try morning, noon, and night to see which is best.

FNU Want You To Succeed!

Try to learn and not just memorize and remember, keep it simple. Don’t try to get fancy with your study notes. They are for your eyes only and won’t be graded. The goal is to help you get a high-scoring grade. We hope this quick checklist will alleviate some anxiety you might have for managing college work. If you have questions about this or any of our degree programs, contact an FNU advisor at any of our campus locations today!

Request More Info

Are you ready for your new career? Schedule your campus tour today!

Clicking the "Send Me Info" button constitutes your express written consent to be called, emailed and/or texted by FNU at the number(s) you provided, regarding furthering your education. You understand that these calls may be generated using an automated technology.

- Share FNU on facebook

- Share FNU on twitter

- Share FNU on linkedin

- Share FNU on facebook facebook.com/FloridaNationalUniversity/

- Share FNU on linkedin LinkedIn

- FNU on facebook-f

- FNU on twitter

- FNU on youtube

- FNU on linkedin

- FNU on instagram

- FNU on tiktok

- Degree Programs

- FNU Continuing Education

- Dual Enrollment

- Application & Requirements

- Visa Info & Requirements

- Financial Aid

- Consumer Information

- Online Degree Programs

- Blackboard Login

- Blackboard Student Tutorial

- Master Degrees

- Bachelor of Arts

- Bachelor of Science

- Associates of Arts

- Associates of Science

- Career Education Diplomas

- Certificates

- Campus Programs

- Academic Advising

- Career Services

- Bursar’s Office

- Registrar’s Office

- Technical Requirements

- University Calendar

- Upcoming Events

- Publications

- Student Achievement

- Men’s Basketball

- Men’s Cross Country

- Men’s Soccer

- Men’s Tennis

- Men’s Track & Field

- Men’s Esports

- Women’s Basketball

- Women’s Cross Country

- Women’s Soccer

- Women’s Tennis

- Women’s Track & Field

- Women’s Volleyball

- Women’s Esports

- Staff Directory

- Athletic Training

- Mission Statement

- Student-Athlete Services

- Visitor’s Guide

- NAIA Champions of Character

- Corporate Sponsors

- Conquistadors Branding

- Equity in Athletics

- Student Athlete Handbook

- Accreditation, Licenses And Approval

- Student Achievement Goals and Success

- Compliance Report

- Classification of Instructional Program (CIP) codes

- National Accreditation & Equivalency Council of the Bahamas Act

- Campus Locations

- Job Openings

- Press Releases

- News Spotlight

- Meet Our Faculty

- Meet Our Administration

- Board of Governors

- Community Services

Best Methods for Developing Effective Study Habits

- Muhammad Asif

- December 24, 2023

You can develop effective study habits with the help of understanding the power of rewards, the tranquility of a beautiful study environment, and the importance of self-awareness.

From setting goals that ignite your passion for learning to understanding the importance of discipline and mentorship, you need practical tips beyond the ordinary.

I adopted some of the best methods for building successful study habits . Here! I share a comprehensive guide on developing good study habits in this enlightening journey.

What is effective study?

Effective study involves learning more in less time. It means more output for less input, which involves multiple ways of learning. Effective study aims for brilliant work focusing on the learning process. It is a purposeful and systematic approach to more productivity.

What are effective study habits?

With effective study habits, you will achieve and adopt productive and systematic behaviors or routines to increase personal, academic, and learning performance.

Reasons: Why are good study habits important?

Here are several reasons why developing effective study habits are important:

- Developing good study habits is essential for academic success and personal growth.

- It is essential to build healthy study habits because we sometimes get distracted as humans. We become victims of negative thoughts about our progress. Building and adapting to study habits are vital to avoid such a situation.

- Efficient study methods optimize learning time, improving information retention and understanding.

- Study habits foster discipline and responsibility, reduce stress, and increase productivity.

- Moreover, good study habits prepare you for future challenges, equipping you with transferable skills like critical thinking and time management. These are crucial in both education and the workforce.

- Forming effective study habits is a key to time management and saving. It also makes you mentally relaxed.

- Ultimately, good study habits establish a foundation for long-term success, encouraging a lifelong commitment to personal development and the pursuit of knowledge.

11 Best Methods for Developing Effective Study Habits

There can be different ways and methods for developing effective study habits. Some of the practical tips are given as follows:

1. Set Goals

Setting goals is one of the most essential tips for making successful study habits . Goals are your plans that keep you on the right path. They motivate and convince you to do great things. Goal setting is the best remedy for creating interest in studies.

If you find it challenging to study regularly, then set a goal.

For example, you can tell yourself you will learn two chapters today. Then, make levels for this one chapter. Level 1 may include reading two paragraphs. Level 2 may consist of reading four sections and so on.

When you set such goals, you are convincing yourself to build a study habit.

2. Reward yourself

When you achieve the specified goals, like reading one chapter, feel free to reward yourself. There are several ways to treat yourself. You can watch a movie, a celebrity, a recent sports game you missed, talk to your favorite person, etc.

Know how to reward yourself for good habits .

Rewards are like food for humans. You can have one or two whenever you perform your studies. Don’t be ashamed and hesitate to get too many tips from yourself.

3. Study in a beautiful place

Beauty is something that gives pleasure. It makes you feel good and fresh. You will like to read there when you have a neat and clean library, room, table, and other necessary study items. It is because your mind will feel relaxed, and your heart will find solace.

When you get command of your heart and mind through beauty, it is where you become addicted to a healthy study habit.

4. Set a proper time

Most people find studies hard because they need to follow a proper schedule. You are at risk if you don’t decide a time of the day for reading. Make a time and table. Mention what time you want to study and for how long.

Remain consistent with your set time. Study only at that specific time and Follow the hours. After you form an effective study habit, you can study anytime.

5. Know the requirements

Your first task for making successful study habits is to know the format and requirements of your studies. Many of you cannot learn because you must see the course expectations.

For example, our fiction teacher assigned us an assignment. She asked me to write a one-page review of the article based on our course novel. She also said we should present the same work. We didn’t write and study the report because we needed clarification as we were confused. We prepared well when asked and got clear instructions about the requirements and format.

So, it is essential to get a clear picture of what you are studying, how you should prepare for it, and so on.

6. Practice and solve previous or model papers

Model papers are the best tools to engage your-self in healthy reading . When you successfully solve them, you get some motivation, which paves the way for building a reading routine. This strategy is helpful for exam preparation.

Practice makes a man perfect, so if you fail to develop a study routine effectively, you are safe because you know the pattern and type of questions you can expect.

7. Learn some of the best study plans and methods

I improved my study skills after reading the book STUDY SKILLS by Stella Cottrell.

It was helpful and strategic. You can save time and energy when you start studying with a strategy. For example, SQ3R is one of the critical methods for making a healthy study schedule. Explore what SQ3R is.

You can also make your plan. Your method will be very workable and motivate you. For example, if you struggle to form an effective study habit, you can name your body organs with the chapters in your course. When you move any organ, it will directly remind you something about the system.

8. Write your achievements

One of the tips for rewarding yourself is to write what you have completed. Note down how much you have read. For example, pick a pen and diary before sleeping and write if you have read one chapter or two or more.

Writing your achievements will give you happiness and satisfaction. Besides, it is also a way to record how much you study on a specific day.

9. Bring variety and novelty

Don’t limit yourself to one method. Always search for new strategies. Discuss your way of reading with your colleagues and find other ways. Also, try to read different subjects on different days.

Make your reading creative and intelligent. Don’t cram, but be a competent reader.

10. Group study

While finding your strength, know if you like group study. Some people can read better when they discuss a topic in group form. If you want group discussions, request and make a group of your fellows and learn through discussions.

11. Include pleasure reading in your schedule

If you still need to improve your studies, give yourself time for pleasure reading. This is one of the best strategies to develop effective study habits . As a student, you lose interest in scientific or course reading because you must memorize it by hook or crook. But pleasure reading does not involve any such action.

Read a short story, a novel, or a poem that will make you happy. So through pleasure reading you can make successful study habits.

How do you study effectively in college?

College is the first step in all our plans. If you become successful here, you have better chances to succeed. As you know, every type of success requires study in one way or another, and so is college. For a beneficial journey and lifelong plans to be executed, you should actively study in college.

There are many ways to perform well in college. Some of them are

Stay disciplined

Discipline is the most crucial part of successful people. Start following discipline if you want to form good study habits and make your time valuable. It will be the door to your success at college and life ahead.

Manage your time

Time management is a crucial skill. Every college student should master time management to develop an effective study schedule . You must manage time to perform any activity effectively.

Make mentors

Mentors are people who guide you towards the best. Finding a mentor in college is such a bliss that your life will be in the right direction. You can save time and energy. They can shape your future. I feel blessed as I found my mentor in my first days of college.

Select best friends

Friend selection is also significant for college students. If you want to study effectively in college , select hardworking students as your friends. They also help you form study habits that can change your life.

Mastering effective study habits is a transformative expedition that empowers you with the tools to navigate the challenges of learning and academia. From setting purposeful goals to creating a harmonious study environment, each step is a building block toward a more productive and fulfilling academic experience. As you embrace the art of self-awareness, discipline, and strategic planning, you unlock the door to success in your current educational endeavors and the broader landscape of life.

Time management is crucial for a successful study routine. Setting a specific time for studying, remaining consistent, and following a schedule contribute to forming effective study habits , allowing for better productivity.

Discipline is essential for success. Following a schedule and dedicating specific hours to study daily helps maintain consistency. Over time, as effective study habits develop, flexibility in study times becomes achievable.

Sharing Is Caring...

Related articles.

10 Wonderful Millionaire Success Habits that Will Transform Your Life

Does becoming a millionaire rely on incorporating certain habits? Yes! There are certain millionaire success

9 Important Habits for Self-Love that Can Change Your Life

“To love oneself is the beginning of a life-long romance.” What are your thoughts after

Happy People and their Habits of Happiness

We always chase something, whether a promotion, a new house, a car, good grades, or

How To Make Exercise A Habit? 17 Easy Steps

Copyright 2024 © All Right Reserved by Habit Corner

Subscribe to our Newsletter

7-Week SSP & 2-Week Pre-College Program are still accepting applications until April 10, or earlier if all course waitlists are full. 4-Week SSP Application is closed.

Celebrating 150 years of Harvard Summer School. Learn about our history.

Top 10 Study Tips to Study Like a Harvard Student

Adjusting to a demanding college workload might be a challenge, but these 10 study tips can help you stay prepared and focused.

Lian Parsons

The introduction to a new college curriculum can seem overwhelming, but optimizing your study habits can boost your confidence and success both in and out of the classroom.

Transitioning from high school to the rigor of college studies can be overwhelming for many students, and finding the best way to study with a new course load can seem like a daunting process.

Effective study methods work because they engage multiple ways of learning. As Jessie Schwab, psychologist and preceptor at the Harvard College Writing Program, points out, we tend to misjudge our own learning. Being able to recite memorized information is not the same as actually retaining it.

“One thing we know from decades of cognitive science research is that learners are often bad judges of their own learning,” says Schwab. “Memorization seems like learning, but in reality, we probably haven’t deeply processed that information enough for us to remember it days—or even hours—later.”

Planning ahead and finding support along the way are essential to your success in college. This blog will offer study tips and strategies to help you survive (and thrive!) in your first college class.

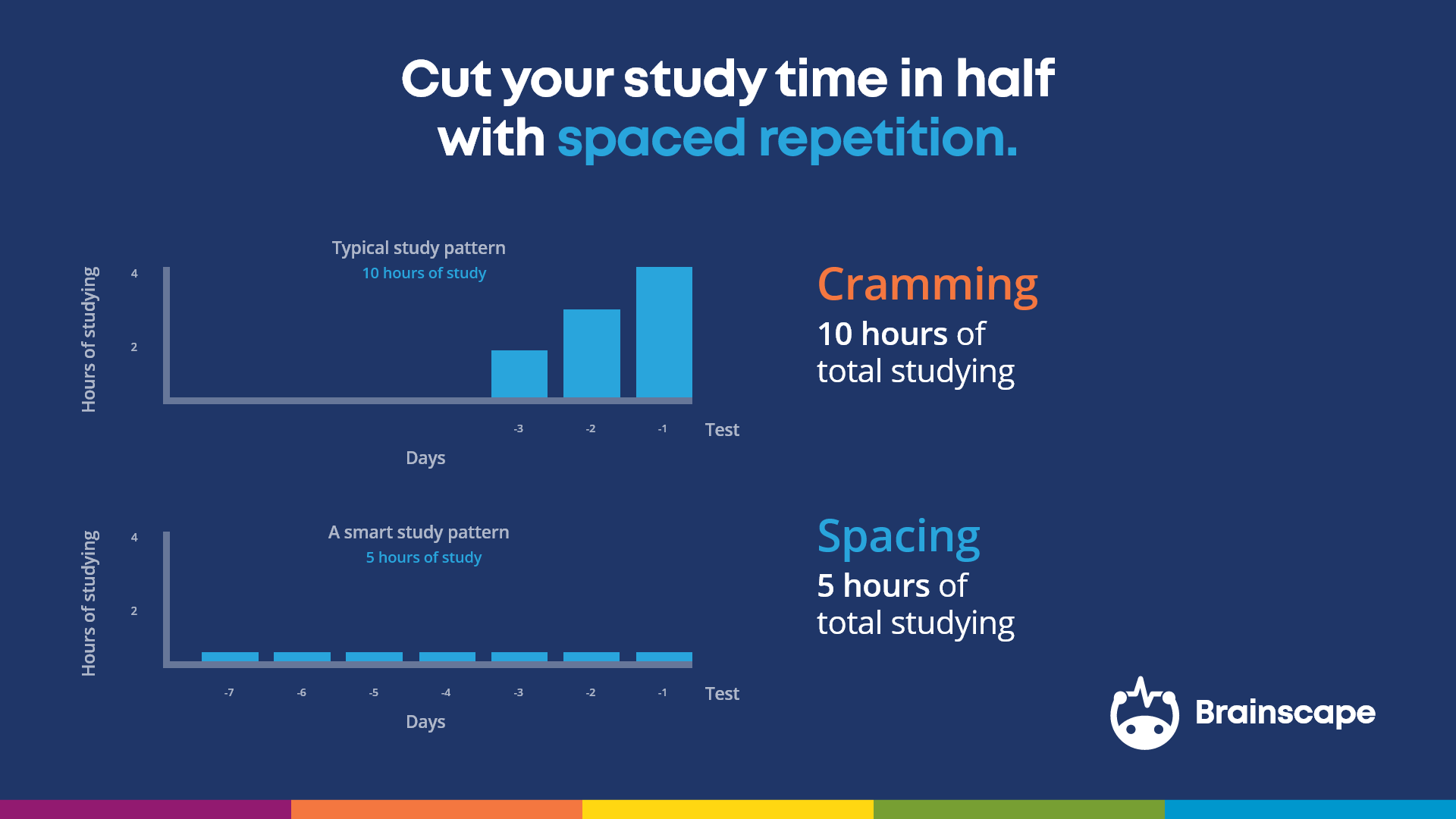

1. Don’t Cram!

It might be tempting to leave all your studying for that big exam up until the last minute, but research suggests that cramming does not improve longer term learning.

Students may perform well on a test for which they’ve crammed, but that doesn’t mean they’ve truly learned the material, says an article from the American Psychological Association . Instead of cramming, studies have shown that studying with the goal of long-term retention is best for learning overall.

2. Plan Ahead—and Stick To It!

Having a study plan with set goals can help you feel more prepared and can give you a roadmap to follow. Schwab said procrastination is one mistake that students often make when transitioning to a university-level course load.

“Oftentimes, students are used to less intensive workloads in high school, so one of my biggest pieces of advice is don’t cram,” says Schwab. “Set yourself a study schedule ahead of time and stick to it.”

3. Ask for Help

You don’t have to struggle through difficult material on your own. Many students are not used to seeking help while in high school, but seeking extra support is common in college.

As our guide to pursuing a biology major explains, “Be proactive about identifying areas where you need assistance and seek out that assistance immediately. The longer you wait, the more difficult it becomes to catch up.”

There are multiple resources to help you, including your professors, tutors, and fellow classmates. Harvard’s Academic Resource Center offers academic coaching, workshops, peer tutoring, and accountability hours for students to keep you on track.

4. Use the Buddy System

Your fellow students are likely going through the same struggles that you are. Reach out to classmates and form a study group to go over material together, brainstorm, and to support each other through challenges.

Having other people to study with means you can explain the material to one another, quiz each other, and build a network you can rely on throughout the rest of the class—and beyond.

5. Find Your Learning Style

It might take a bit of time (and trial and error!) to figure out what study methods work best for you. There are a variety of ways to test your knowledge beyond simply reviewing your notes or flashcards.

Schwab recommends trying different strategies through the process of metacognition. Metacognition involves thinking about your own cognitive processes and can help you figure out what study methods are most effective for you.

Schwab suggests practicing the following steps:

- Before you start to read a new chapter or watch a lecture, review what you already know about the topic and what you’re expecting to learn.

- As you read or listen, take additional notes about new information, such as related topics the material reminds you of or potential connections to other courses. Also note down questions you have.

- Afterward, try to summarize what you’ve learned and seek out answers to your remaining questions.

Explore summer courses for high school students.

6. Take Breaks

The brain can only absorb so much information at a time. According to the National Institutes of Health , research has shown that taking breaks in between study sessions boosts retention.

Studies have shown that wakeful rest plays just as important a role as practice in learning a new skill. Rest allows our brains to compress and consolidate memories of what we just practiced.

Make sure that you are allowing enough time, relaxation, and sleep between study sessions so your brain will be refreshed and ready to accept new information.

7. Cultivate a Productive Space

Where you study can be just as important as how you study.

Find a space that is free of distractions and has all the materials and supplies you need on hand. Eat a snack and have a water bottle close by so you’re properly fueled for your study session.

8. Reward Yourself

Studying can be mentally and emotionally exhausting and keeping your stamina up can be challenging.

Studies have shown that giving yourself a reward during your work can increase the enjoyment and interest in a given task.

According to an article for Science Daily , studies have shown small rewards throughout the process can help keep up motivation, rather than saving it all until the end.

Next time you finish a particularly challenging study session, treat yourself to an ice cream or an episode of your favorite show.

9. Review, Review, Review

Practicing the information you’ve learned is the best way to retain information.

Researchers Elizabeth and Robert Bjork have argued that “desirable difficulties” can enhance learning. For example, testing yourself with flashcards is a more difficult process than simply reading a textbook, but will lead to better long-term learning.

“One common analogy is weightlifting—you have to actually “exercise those muscles” in order to ultimately strengthen your memories,” adds Schwab.

10. Set Specific Goals

Setting specific goals along the way of your studying journey can show how much progress you’ve made. Psychology Today recommends using the SMART method:

- Specific: Set specific goals with an actionable plan, such as “I will study every day between 2 and 4 p.m. at the library.”

- Measurable: Plan to study a certain number of hours or raise your exam score by a certain percent to give you a measurable benchmark.

- Realistic: It’s important that your goals be realistic so you don’t get discouraged. For example, if you currently study two hours per week, increase the time you spend to three or four hours rather than 10.

- Time-specific: Keep your goals consistent with your academic calendar and your other responsibilities.

Using a handful of these study tips can ensure that you’re getting the most out of the material in your classes and help set you up for success for the rest of your academic career and beyond.

Learn more about our summer programs for high school students.

About the Author

Lian Parsons is a Boston-based writer and journalist. She is currently a digital content producer at Harvard’s Division of Continuing Education. Her bylines can be found at the Harvard Gazette, Boston Art Review, Radcliffe Magazine, Experience Magazine, and iPondr.

Becoming Independent: Skills You’ll Need to Survive Your First Year at College

Are you ready? Here are a few ideas on what it takes to flourish on campus.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Daniel Wong

22 Study Habits That Guarantee Good Grades

Updated on June 6, 2023 By Daniel Wong 18 Comments

Were you hoping to get an A for your last test or exam, but your study habits got in the way?

Maybe you got a B, or maybe you did worse than that.

It’s annoying, isn’t it…

You put in all those hours of studying. You even gave up time with your friends.

So what if I could show you a way to work smarter and not harder, so you get good grades and have time for the things you enjoy and find meaningful?

Even better, what if I could guarantee it?

Well, I can.

All you have to do is adopt these 22 study habits.

(Throughout my career as a student I got straight A’s, so I can promise you that these study habits work.)

Want to get the grades you’ve always wanted while also leading a balanced life?

Then let’s get started.

Enter your email below to download a PDF summary of this article. The PDF contains all the habits found here, plus 5 exclusive bonus habits that you’ll only find in the PDF.

The best study habits.

Add these effective study habits to your routine to start getting good grades with a lot less stress.

Habit #1: Create a weekly schedule

When you schedule time for a particular task like studying, you’re saying to yourself, “I’m going to focus on studying at this time, on this date, and it’s going to take this number of hours.”

Once it’s down in writing, it becomes a reality and you’re more likely to stick to it.

This might sound weird, but it’s true.

Do this in your calendar, in a spreadsheet, or download a template – whatever works best for you.

First, think about your fixed commitments like school, sports practice, family time, religious activities and so on.

Now, decide which times around these fixed commitments are the best for you to do your work and revision each week.

Don’t worry about exactly what work you’ll be doing, or what assignments are due. Just focus on blocking out the times.

Your weekly study schedule might look something like this (the blue slots are the times you’ve blocked out to do work):

Give yourself a study-free day (or at least half a day) once a week.

Everyone needs a break, so you’re more likely to come back to the work refreshed if you give yourself permission to take some time off.

Habit #2: Create a pre-studying checklist

Have you ever heard your mother say you should never go to the supermarket without a shopping list?

You’ll wander up and down the aisles, wasting time. You’ll make poor choices about what to buy and end up with all the wrong things for dinner.

By using a shopping list, your mind will be focused. You’ll only put items in your shopping trolley that you need, checking them off as you go.

It’s no different from a checklist used by a pilot before he takes off, or a mechanic as he services a car.

Checklists are essential as you learn how to develop good study habits. They ensure that you cover all the necessary steps to achieve an outcome.

Here are some of the things that might be on your pre-studying checklist:

- Set up workspace

- Make sure your phone is in another room or turned off

- Let family members know not to disturb you until the end of the study session

- Gather together all the notes and reference books needed

- Get a glass of water

Keep your checklist handy, and tick everything off at the start of every study session.

Habit #3: Create a study plan

The purpose of a study plan is similar to that of a checklist. It keeps you on track.

When you go camping, you might have a checklist that covers all the equipment you need to pack into the car.

But you also need a road map to show you how to get to the campsite. It allows you to plan your route, and keeps you focused on your destination.

So, at the start of each study session, create a study plan.

For example, today you might need to complete a math assignment and write up the summary notes of chapter 4 of your history textbook.

Write down the key tasks, together with a list of steps you’ll need to take along the way.

To complete your math assignment, you might write:

- Read notes from math class

- Read chapter in the textbook on algebraic calculations

- Do questions 1 to 3