The future of banking: Time to rethink business models

4-MINUTE READ

- Banking is changing as a new wave of digital-only players fragment the market, componentize products and challenge age-old business models.

- New research examines the business models of traditional and digital-only players to identify how value chain fragmentation is reshaping the industry.

- Our analysis shows that the digital-only players using adaptive models enjoyed higher revenue growth compared to players with traditional models.

- Incumbent banks can catalyze growth by operating a range of new models in parallel with the current core of the business.

An age-old model gets turned on its head

The digital revolution has finally come for one of banking’s long-standing foundations.

For years, business models in the industry were as fixed as panes of stained-glass cathedral windows. A bank typically owned each layer of the value chain and would create, package, and distribute its products, whether the bank was a century-old global titan or a neobank offering a digital alternative to traditional offerings. Its models were monolithic, linear and vertically integrated.

But new waves of digital-only players have unshackled themselves from vertical integration and are fragmenting the banking value chain by choosing which layers they want to play in. They are also unbundling traditional products into micro-products or services and re-bundling their own offerings together with components from other providers to offer better customer propositions.

Many digital-only players are using this non-linear and adaptive business model to attack incumbent banks where they are most exposed. The strategy of each challenger varies, but they are unified in their ability to configure innovative products and propositions quickly and at scale, with lower customer acquisition costs.

The result in most markets? A steady outflow of banking and payments revenues from incumbents to new entrants.

There’s value in going non-linear, our report shows

Our Future of Banking report analyzes the business models of leading incumbent banks and digital-only players to identify how value chain fragmentation and product componentization are reshaping the banking market of the future.

We found that digital-only players with non-linear business models are outperforming those that simply emulate vertically integrated models in the digital world. They can also adapt more easily to product componentization and further value chain fragmentation to respond quickly to future disruption in the market.

The average compound annual revenue growth of banks and competing players in our study that utilize different business models (between 2018 and 2020):

digital-only players with non-linear models.

digital-only players emulating traditional vertically integrated models.

traditional banks with vertically integrated models.

The performance of these digital-only, non-linear challengers offers inspiration for incumbent banks looking for breakout growth and higher market valuations. The billion dollar question is: where to begin?

The life centricity playbook

Crafting a kaleidoscope of business models.

Large banks are understandably reluctant to discard the vertically integrated business models that still drive their profitability. The good news is that taking on non-linear business models is not an all-or-nothing proposition.

The key to success in this flexible, fluid environment is not just to shift from yesterday’s business model to a new one. Rather, it is to evolve from reliance on a single, vertically integrated business model to multiple non-linear models and roles in the value chain.

Owning the value chain end-to-end and selling only your own products are no longer requirements for success. Architecting and creating value for the end-customer or for the next player in the value chain offer new paths to differentiation and growth. This requires having the vision and flexibility to reimagine and “package” compelling propositions that truly focus on customers’ needs and intentions.

To become a value architect, banks should consider playing a range of roles in the value chain. Depending on the size, market and strength of the bank, an incumbent can embrace any mix of these approaches to increase business model flexibility and differentiate itself from the competition.

Sell the bank’s own products

Control all layers of the value chain, from manufacturing to distribution, in a traditional model of vertical integration

Build a distribution-driven ecosystem

Distribute financial products of all kinds from other companies, or even non-banking products.

Sell banking capability as a service

Reach scale by manufacturing technology or business processes that are invisible to end-clients.

Create new propositions through bundling

Build or package fragmented micro-products or products for distribution through other companies and digital experiences.

In the leading banks of tomorrow, the traditional model of vertical integration will co-exist with an endlessly configurable kaleidoscope of non-linear models. This will allow these banks to both defend their existing business and seize new opportunities. By unshackling themselves from the traditional value chain, they can grow and scale in new markets while lowering the cost of growth.

You can find more detail on the future of banking business models in our report .

By rethinking their business models and embracing the innovative strategies of digital-only banking and financial services new entrants, banks could boost revenues by nearly 4% annually.

Senior Managing Director – Global Banking Lead

Managing Director – Strategy & Consulting, Credit Lead, EMEA

Dilnisin advises financial services firms on how to stay ahead of major changes in credit, helping them to transform their business for the future.

Purpose: Driving powerful transformation for banks

The banking experience reimagined

Global banking industry outlook

Related capabilities, intelligent operations.

At the New York Fed, our mission is to make the U.S. economy stronger and the financial system more stable for all segments of society. We do this by executing monetary policy, providing financial services, supervising banks and conducting research and providing expertise on issues that impact the nation and communities we serve.

Introducing the New York Innovation Center: Delivering a central bank innovation execution

Do you have a Freedom of Information request? Learn how to submit it.

Learn about the history of the New York Fed and central banking in the United States through articles, speeches, photos and video.

Markets & Policy Implementation

- Effective Federal Funds Rate

- Overnight Bank Funding Rate

- Secured Overnight Financing Rate

- SOFR Averages & Index

- Broad General Collateral Rate

- Tri-Party General Collateral Rate

- Treasury Securities

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Repos & Reverse Repos

- Securities Lending

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps

- System Open Market Account Holdings

- Primary Dealer Statistics

- Historical Transaction Data

- Agency Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Agency Debt Securities

- Discount Window

- Treasury Debt Auctions & Buybacks as Fiscal Agent

- Foreign Exchange

- Foreign Reserves Management

- Central Bank Swap Arrangements

- ACROSS MARKETS

- Actions Related to COVID-19

- Statements & Operating Policies

- Survey of Primary Dealers

- Survey of Market Participants

- Annual Reports

- Primary Dealers

- Reverse Repo Counterparties

- Foreign Exchange Counterparties

- Foreign Reserves Management Counterparties

- Operational Readiness

- Central Bank & International Account Services

- Programs Archive

As part of our core mission, we supervise and regulate financial institutions in the Second District. Our primary objective is to maintain a safe and competitive U.S. and global banking system.

The Governance & Culture Reform hub is designed to foster discussion about corporate governance and the reform of culture and behavior in the financial services industry.

Need to file a report with the New York Fed? Here are all of the forms, instructions and other information related to regulatory and statistical reporting in one spot.

The New York Fed works to protect consumers as well as provides information and resources on how to avoid and report specific scams.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York works to promote sound and well-functioning financial systems and markets through its provision of industry and payment services, advancement of infrastructure reform in key markets and training and educational support to international institutions.

The New York Fed provides a wide range of payment services for financial institutions and the U.S. government.

The New York Fed offers several specialized courses designed for central bankers and financial supervisors.

The New York Fed has been working with tri-party repo market participants to make changes to improve the resiliency of the market to financial stress.

- High School Fed Challenge

- College Fed Challenge

- Teacher Professional Development

- Classroom Visits

- Museum & Learning Center Visits

- Educational Comic Books

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- Economic Education Calendar

We are connecting emerging solutions with funding in three areas—health, household financial stability, and climate—to improve life for underserved communities. Learn more by reading our strategy.

The Economic Inequality & Equitable Growth hub is a collection of research, analysis and convenings to help better understand economic inequality.

This Economist Spotlight Series is created for middle school and high school students to spark curiosity and interest in economics as an area of study and a future career.

« Unequal Burdens: Racial Differences in ICU Stress during the Third Wave of COVID‑19 | Main | The Housing Boom and the Decline in Mortgage Rates »

Going with the Flow: Changes in Banks’ Business Model and Performance Implications

Nicola Cetorelli, Michael G. Jacobides, and Samuel Stern

Does the performance of banks improve or worsen when banks enter into new business activities? And does it matter which activities a bank expands into, or retreats from, and when that decision is made? These important questions have remained unaddressed due to a lack of data. In a recent publication , we used a unique data set detailing the organizational structure of the entire population of U.S. bank holding companies (BHCs). In this post, we draw on that research to show that while scope expansion on average hurts performance, entering into activities that are highly synergistic with core banking at a given point in time yields net performance benefits.

Transformation in U.S. Banks’ Organizational Structure

In the past two to three decades, U.S. banking institutions have gone through the largest and deepest process of scope transformation in history. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, more than half of the population of BHCs (accounting for about 97 percent of total industry assets) either created or took control of tens of thousands of subsidiaries, spanning virtually every activity within the financial industry and even beyond. For example, between 1990 and 2006, more than 230 distinct U.S. BHCs incorporated securities-dealer or broker subsidiaries, about 500 took control of insurance agencies, and over 1,000 added one or more special purpose vehicle legal entities to their organizations.

Costs and Benefits of Adding Subsidiaries

The so-called “agency view” predicts that adding new operational units, especially those engaged in activities that the organization has not previously focused on, will impose a variety of costs (misallocation of resources, for example) associated with agency frictions within the organizational hierarchy. And yet, scope expansion is widely observed through time and across industries, suggesting that adding subsidiaries may promise underlying economic gains . An influential strand of research in the strategy literature, known as the “ resource-based view ,” has emphasized that a firm may benefit from expanding scope into business activities where its current resources can be efficiently redeployed. This, in turn, rests on the premise that certain activity types are more likely than others to share similar processes, knowledge bases, human capital, and so on. Such relatedness across activities should translate into relatively larger efficiency gains and/or the attainment of return synergies associated with their joint operation.

A challenge in trying to capture relatedness across activities is that sectors are not static. As Teece et al. have observed, industries evolve, and so should the opportunities for synergies across activities. This suggests that relatedness has a life cycle, so that certain additions may confer different performance benefits at different points in time . The observation rings particularly true for U.S. banking, where the mode of financial intermediation changed so dramatically during the 1990s and 2000s.

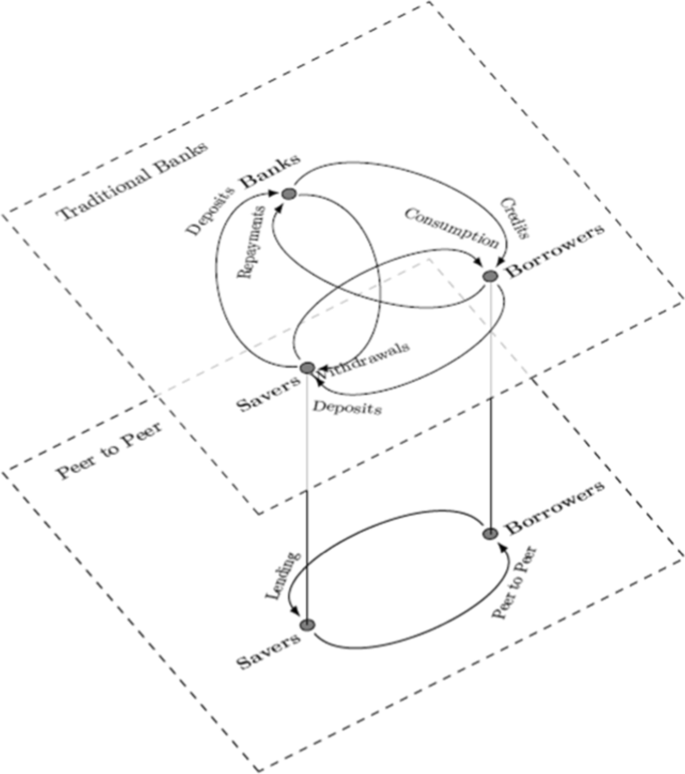

The banking sector shifted from a model where commercial banks brokered supply and demand of intermediated funds, to a decentralized system where matching increasingly took place through much longer credit intermediation chains, with nonbank entities emerging as providers of specialized inputs along the way. This evolution created new opportunities for potential synergies across a variety of businesses—but the value of those synergies also varied depending on regulatory, technological, and market conditions. For example, the newfound benefits from combining commercial banking with securities dealing and underwriting, following the institution of Section 20 subsidiaries in the late 1980s/early 1990s, appear to have increased firm-level value, and probably especially so in the run-up to the 90s technology boom. Likewise, the surge in asset securitization throughout the 1990s likely created the conditions for banking institutions to add specialty lenders, special purpose vehicles, and servicers, among others.

Empirical Study of Relatedness

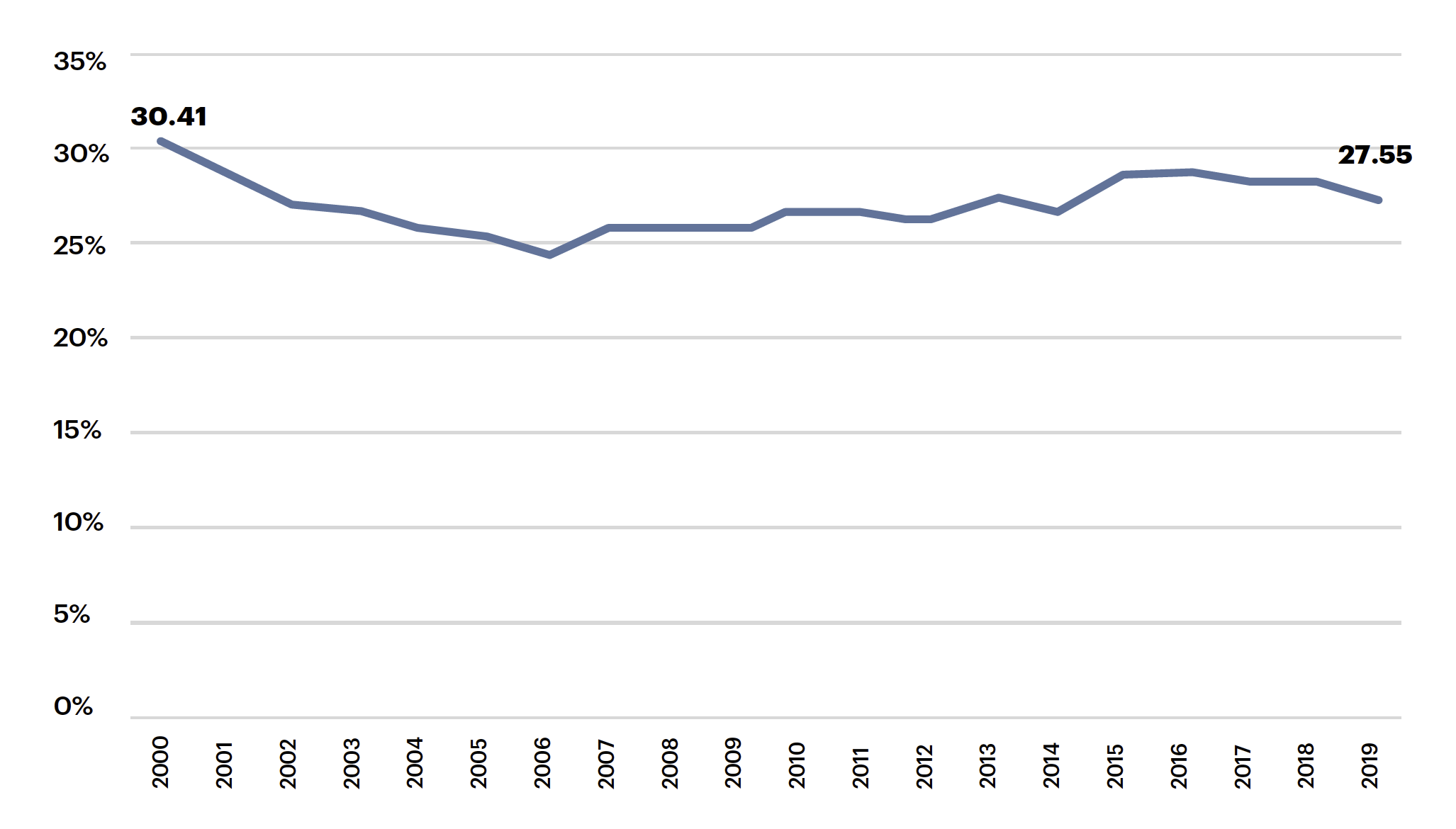

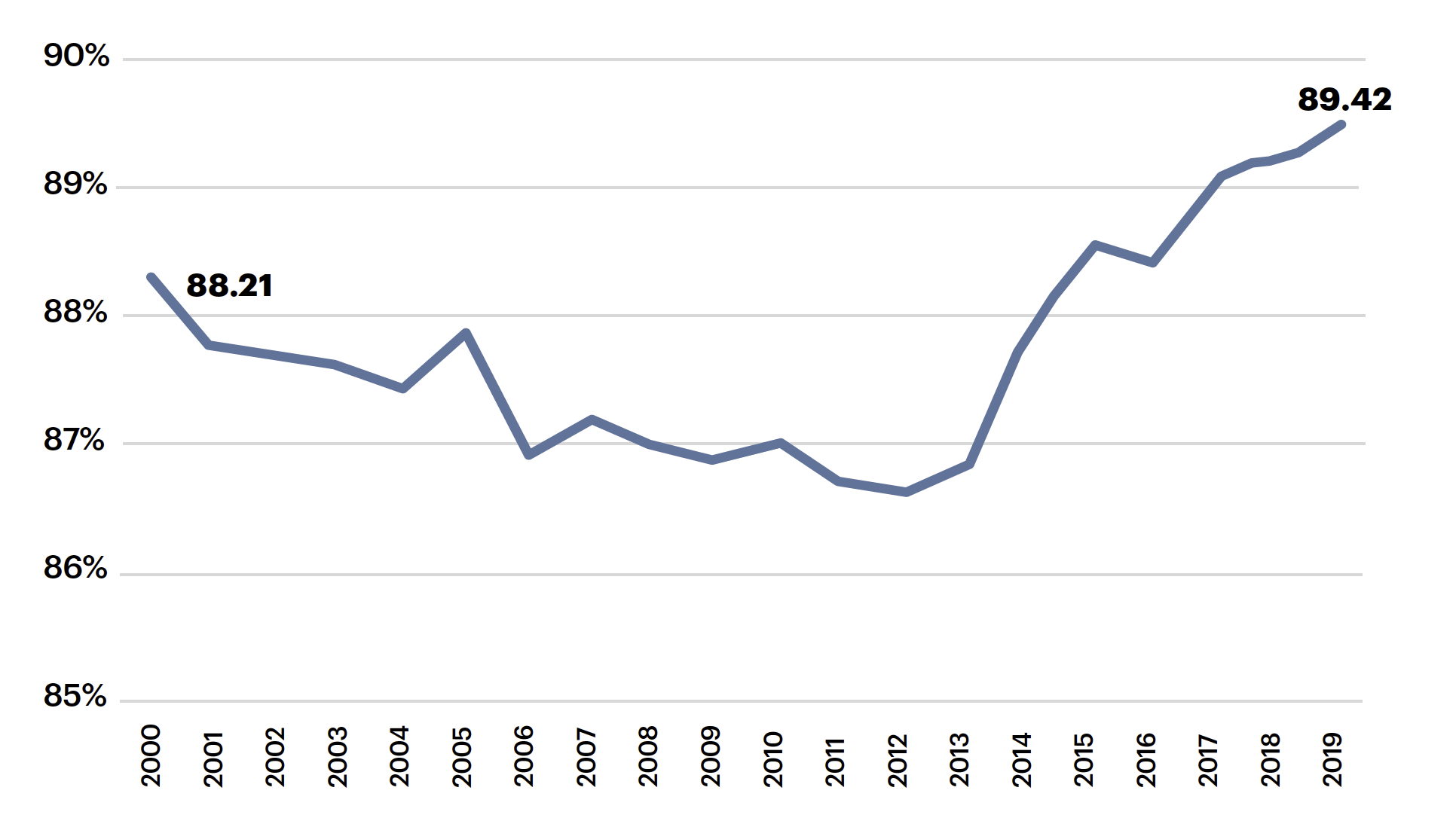

The empirical analysis of an evolving relatedness has represented a major challenge in applied studies because of the demanding data needs. However, we are able to address these needs in our study. Following the strategy literature, we capture relatedness by looking at how many BHCs choose to hold a given activity at a given time, under the plausible assumption that the more popular activities are those closer to the current core of intermediation. Such a metric could only be computed by having full information on scope of the entire population of BHCs, which is what our database provides.

We can offer a simple visualization of this concept of evolving relatedness. The chart below shows, for a sample of alternative business activities, the proportion of BHCs in any quarter/year reporting at least one entity that both is part of their organization and was engaged in that activity. So, for instance, special purpose vehicles (included in “Other financial vehicles”) were hardly found in BHCs’ organizational structures in the early 1990s, but they indeed became a staple for BHCs in later years, as the asset securitization boom prompted banks to move into that business area, and new synergies emerged as a result.

Waxing and Waning of Banks’ Business Scope

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report of Changes in Organizational Structure (Y-10); authors’ calculations.

Conversely, entities managing residential dwellings (included in “Lessors of residential buildings and dwellings”) were relatively very popular in the cross section of BHCs in the early 1990s. These were indeed times when balance-sheet assets such as mortgages and their collateral defined the predominant scope of a commercial bank—but later they declined into obscurity, probably mirroring the subsequent evolution toward the originate-and-distribute model of intermediation. At the same time, securities brokerage entities and insurance brokerage firms start at similar levels of popularity but diverge later on.

How Should Relatedness Contribute to Performance?

Using the chart above as an illustration, we conjecture that a BHC entering the insurance business for the first time when this activity is at the nadir of its popularity should yield a smaller performance boost than if entry is done at a time when the insurance business is more integrated with banking, as reflected by insurance subsidiaries being found more frequently across BHCs. We find that this is indeed the case. According to our estimates, BHCs that expanded into this activity in the early 1990s were more likely to experience a net negative impact on their return on equity . Conversely, for BHCs that expanded instead when the activity was at its maximum popularity (around the mid-2000s), the return on equity increased.

We brought this intuition to the data and sought more systematic evidence, and our overall findings confirm this example: BHCs pursuing scope transformation strategies on averagedo not do as well as their peers. However, it matters a lot whichactivities a BHC expand into, but even more importantly whensuch entry occurs: entry into activities when those activities are highly related to core bankingtranslates into significant net performance gains.

We find that expansion into activities when they are highly related to core banking seems to be beneficial for BHCs. However, we should also clarify that benefits for BHCs that transform their scope do not necessarily imply concomitant benefits for society as a whole, nor do they rule out the possibility of associated negative systemic externalities (see, for example, Rajan 2011 and Jacobides et al 2014 ). This in an important issue, and one deserving of a separate undertaking.

Nicola Cetorelli is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael G. Jacobides is the Sir Donald Gordon Professor of entrepreneurship and innovation and Professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at London Business School.

Samuel Stern is a Ph.D. student at the University of Michigan and a former senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post: Nicola Cetorelli, Michael G. Jacobides, and Samuel Stern, “Going with the Flow: Changes in Banks’ Business Model and Performance Implications,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics , September 1, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/09/going-with-the-flow-changes-in-banks-business-model-and-performance-implications.

Related Reading Same Name, New Businesses: Evolution in the Bank Holding Company The Evolution of Banks and Financial Intermediation Were Banks Ever ‘Boring’? Were Banks ‘Boring’ before the Repeal of Glass-Steagall?

Disclaimer The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Share this:

This is a very useful and interesting piece of work. Was it not possible to bring the data forward to analyze the period through and post financial crisis? The addition of more fee based businesses like asset management would seem important to understand.

The comments to this entry are closed.

Liberty Street Economics features insight and analysis from New York Fed economists working at the intersection of research and policy. Launched in 2011, the blog takes its name from the Bank’s headquarters at 33 Liberty Street in Manhattan’s Financial District.

The editors are Michael Fleming, Andrew Haughwout, Thomas Klitgaard, and Asani Sarkar, all economists in the Bank’s Research Group.

Liberty Street Economics does not publish new posts during the blackout periods surrounding Federal Open Market Committee meetings.

The views expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the position of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

Economic Inequality

Most Read this Year

- Credit Card Delinquencies Continue to Rise—Who Is Missing Payments?

- Deposit Betas: Up, Up, and Away?

- The Great Pandemic Mortgage Refinance Boom

- The Post-Pandemic r*

- Spending Down Pandemic Savings Is an “Only-in-the-U.S.” Phenomenon

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data)

- Economic Roundtable

- OECD Insights

- World Bank/All about Finance

We encourage your comments and queries on our posts and will publish them (below the post) subject to the following guidelines:

Please be brief : Comments are limited to 1,500 characters.

Please be aware: Comments submitted shortly before or during the FOMC blackout may not be published until after the blackout.

Please be relevant: Comments are moderated and will not appear until they have been reviewed to ensure that they are substantive and clearly related to the topic of the post.

Please be respectful: We reserve the right not to post any comment, and will not post comments that are abusive, harassing, obscene, or commercial in nature. No notice will be given regarding whether a submission will or will not be posted.

Comments with links: Please do not include any links in your comment, even if you feel the links will contribute to the discussion. Comments with links will not be posted.

Send Us Feedback

The LSE editors ask authors submitting a post to the blog to confirm that they have no conflicts of interest as defined by the American Economic Association in its Disclosure Policy. If an author has sources of financial support or other interests that could be perceived as influencing the research presented in the post, we disclose that fact in a statement prepared by the author and appended to the author information at the end of the post. If the author has no such interests to disclose, no statement is provided. Note, however, that we do indicate in all cases if a data vendor or other party has a right to review a post.

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- Request a Speaker

- International, Seminars & Training

- Governance & Culture Reform

- Data Visualization

- Economic Research Tracker

- Markets Data APIs

- Terms of Use

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Understanding Banking History

Banking in the Roman Empire

European monarchs discover easy money, adam smith gives rise to free-market banking, merchant banks come into power, j.p. morgan rescues the banking industry, the end of an era, the birth of the fed, world war ii and the rise of modern banking, banking goes digital.

- History of Banking FAQs

The Bottom Line

- Personal Finance

The Evolution of Banking Over Time

From the ancient world to the digital age

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/andy__andrew_beattie-5bfc262946e0fb005143d642.jpg)

Banking has been in existence since the first currencies were minted and wealthy people realized they needed a safe place to store their money. Ancient empires also needed a functioning financial system to facilitate trade, distribute wealth, and collect taxes. Banks were to play a major role in that, just as they do today.

Key Takeaways

- Religious temples became the earliest banks because they were seen as safe places to store money.

- Before long, temples got into the business of lending money at interest, much as modern banks do.

- By the 18th century, many governments gave banks a free hand to operate, based on the theories of economist Adam Smith.

- Numerous financial crises and bank panics over the decades eventually led to increased regulation.

Banking Is Born

The barter system of exchanging goods for goods worked reasonably well for the earliest communities. It prove problematic as soon as people started traveling from town to town in search of new markets for their goods and new products to take home.

Over time, coins of various sizes and metals began to be minted to provide a store of value for trade.

Coins, however, need to be kept in a safe place, and ancient homes did not have steel safes. Wealthy people in Rome stored their coins and jewels in the basements of temples. They were seen to be secure, given the presence of priests and temple workers, not to mention armed guards.

Historical records from Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Babylon suggest that temples loaned money in addition to keeping it safe. The fact that temples often functioned as the financial centers of their cities is one reason why they were inevitably ransacked during wars.

Coins could be exchanged and hoarded more easily than other commodities, such as 300-pound pigs, so a class of wealthy merchants took to lending coins, with interest , to people in need of them. Temples typically handled large loans, including those to various sovereigns, while wealthy merchant money lenders handled the rest.

The Romans, who were expert builders and administrators, extricated banking from the temples and formalized it within distinct buildings. During this time, moneylenders still profited, as loan sharks do today, but most legitimate commerce—and almost all government spending—involved the use of an institutional bank.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, Julius Caesar initiated the practice of allowing bankers to confiscate land in lieu of loan payments. This was a monumental shift of power in the relationship of creditor and debtor , as landed noblemen had previously been untouchable, passing debts on to their descendants until either the creditor’s or debtor’s lineage died out.

The Roman Empire eventually crumbled, but some of its banking institutions lived on in the Middle Ages through the services of papal bankers and the Knights Templar. Small-time moneylenders who competed with the church were often denounced for usury .

Eventually, the monarchs who reigned over Europe noted the value of banking institutions. As banks existed by the grace—and occasionally, the explicit charters and contracts—of the ruling sovereignty, the royal powers began to take loans, often on the king’s terms, to make up for hard times at the royal treasury.

This easy access to financing led kings into gross extravagances, costly wars, and arms races with neighboring kingdoms, not to mention crushing debt.

In 1557, Philip II of Spain managed to burden his kingdom with so much debt due to several pointless wars that he caused the world’s first national bankruptcy —as well as the world’s second, third, and fourth, in rapid succession. These events occurred because 40% of the country’s gross national product (GNP) went toward servicing the nation's debt.

The practice of turning a blind eye to the creditworthiness of powerful customers continues to haunt banks today.

Banking was already well-established in the British Empire when economist Adam Smith introduced his invisible hand theory in 1776. Empowered by his views of a self-regulating economy, moneylenders and bankers managed to limit the state’s involvement in the banking sector and the economy as a whole. This free-market capitalism and competitive banking found fertile ground in the New World, where the United States of America was about to emerge.

In its earliest days, the United States did not have a single currency. Banks could create a currency and distribute it to anyone who would accept it. If a bank failed, the banknotes that it had issued became worthless. A single bank robbery could crush a bank and its customers. Compounding these risks was a cyclical cash crunch that could disrupt the system at any time.

Alexander Hamilton , the first secretary of the U.S. Treasury, established a national bank that would accept member banknotes at par , thus keeping banks afloat through difficult times. After a few stops, starts, cancellations, and resurrections, this national bank created a uniform national currency and set up a system by which national banks backed their notes by purchasing Treasury securities , thus creating a liquid market . The national banks then pushed out the competition through the imposition of taxes on the relatively lawless state banks .

The damage had been done, however, as average Americans had grown to distrust banks and bankers in general. This feeling would lead the state of Texas to outlaw corporate banks with a law that stood until 1904.

Most of the economic duties that would have been handled by the national banking system, in addition to regular banking business like loans and corporate finance , soon fell into the hands of large merchant banks . During this period, which lasted into the 1920s, the merchant banks parlayed their international connections into enormous political and financial power.

These banks included Goldman Sachs ; Kuhn, Loeb & Co.; and J.P. Morgan & Co. Originally, they relied heavily on commissions from foreign bond sales from Europe, with a small backflow of American bonds trading in Europe. This allowed them to build capital.

As large industries emerged and created the need for major corporate financing, the amounts of capital required could not be provided by any single bank. Initial public offerings (IPOs) and bond offerings to the public became the only way to raise the amount of money needed.

Successful offerings boosted a bank’s reputation and put it in a position to ask for more to underwrite an offer. By the late 1800s, many banks demanded a position on the boards of the companies seeking capital, and if the management proved lacking, they ran the companies themselves.

J.P. Morgan & Co. emerged at the head of the merchant banks during the late 1800s. It was connected directly to London, then the world’s financial center, and had considerable political clout in the United States.

Morgan & Co. created U.S. Steel, AT&T, and International Harvester, as well as duopolies and near- monopolies in the railroad and shipping industries, through the revolutionary use of trusts and a disdain for the Sherman Antitrust Act .

It remained difficult, however, for average Americans to obtain loans or other banking services. Merchant banks didn’t advertise and rarely extended credit to the “common” people. Racism was widespread. Merchant banks left consumer lending to the lesser banks, which were still failing at an alarming rate.

The collapse in shares of a copper trust set off the Bank Panic of 1907 , with a run on banks and stock sell-offs. Without a Federal Reserve Bank to take action to stop the panic, the task fell to J.P. Morgan personally. Morgan used his considerable clout to gather all the major players on Wall Street and persuade them to deploy the credit and capital that they controlled, just as the Fed would do today.

Ironically, Morgan’s move ensured that no private banker would ever again wield that much power. In 1913, the U.S. government formed the Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed). Although the merchant banks influenced the structure of the Fed, they were also pushed into the background by its creation.

Even with the establishment of the Fed, enormous financial and political power remained concentrated on Wall Street. When World War I broke out, the United States became a global lender, and by the end of the war, it had replaced London as the center of the financial world.

At that point, the government decided to put some handcuffs on the banking sector. It insisted that all debtor nations pay back their war loans—which traditionally were forgiven, especially in the case of allies—before any American institution would extend them further credit.

This slowed world trade and caused many countries to become hostile toward American goods. When the stock market crashed on Black Tuesday in 1929, the already-sluggish world economy was knocked out. The Fed couldn’t contain the damage, which led to some 9,000 bank failures from 1929 to 1933.

New laws emerged to salvage the banking sector and restore consumer confidence. With the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, for example, commercial banks were no longer allowed to speculate with consumers’ deposits, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) was created to insure accounts up to certain limits. The insured limit as of 2023 is $250,000 per account.

World War II may have saved the banking industry from complete destruction. For the banks and the Fed, the war required financial maneuvers involving billions of dollars. This massive financing operation created companies with huge credit needs that, in turn, spurred banks into mergers to meet the demand. These huge banks spanned global markets.

More importantly, domestic banking in the United States finally settled to the point where, with the advent of deposit insurance and widespread mortgage lending , the average citizen could have confidence in the banking system and reasonable access to credit. The modern era had arrived.

The most significant development in the world of banking in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has been the advent of online banking , which in its earliest forms dates back to the 1980s but really began to take off with the rise of the internet in the mid-1990s.

The growing adoption of smartphones and mobile banking apps further accelerated the trend. While many customers continue to conduct at least some of their business at brick-and-mortar banks, a 2021 J.D. Power survey found that 41% of them have gone digital-only.

What Does a Central Bank Do?

A central bank is a financial institution that is authorized by a government to oversee and regulate the nation’s monetary system and its commercial banks. It produces and manages the nation's currency. Most of the world’s countries have central banks for that purpose. In the United States, the central bank is the Federal Reserve System.

Who Regulates Banks in the U.S. Today?

Depending on how they are chartered, commercial banks in the United States are regulated by a number of government agencies, including the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) , and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC).

State-chartered banks are also regulated by the state in which they do business.

Investment banks are largely regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) .

What Is the Difference Between a Commercial Bank and an Investment Bank?

Commercial banks provide services to the general public and to businesses. They take deposits, issue loans, and operate ATMS.

Investment banks provide services only to large companies, institutional investors , and some high-net-worth individuals . Those services include helping companies raise money by issuing stocks or bonds or obtaining loans. They may also be deal-makers, facilitating corporate mergers and acquisitions.

Investopedia / Yurle Villegas

Banks have come a long way from the temples of the ancient world, but their basic business practices have not changed much. Although history has altered the finer points of the business model, a bank’s purposes are still to make loans and to protect depositors’ money.

Even today, where digital banking and financing are replacing traditional brick-and-mortar locations, banks still perform these fundamental functions.

World History Encyclopedia. “ Banking in the Roman World .”

World History Encyclopedia. “ Caesar as Dictator: His Impact on the City of Rome .”

World History Encyclopedia. " Knights Templar ."

New World Encyclopedia. “ Philip II of Spain .”

Adam Smith Institute. “ The Theory of Moral Sentiments .”

JSTOR. " Banks' Own Private Currencies in 19th-Century America ."

Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives. " The First Bank of the United States ."

Federal Reserve History. " National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 ."

Texas Department of Banking. " History of the Banking Industry in Texas and the Department ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Banks, Insider Connections, and Industrialization in New England: Evidence from the Panic of 1873 ."

JPMorgan Chase & Co. " History of Our Firm ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Did J. P. Morgan's Men Add Value? An Economist's Perspective on Financial Capitalism ," Table 6.2.

Federal Reserve History. “ The Panic of 1907 .”

Federal Reserve History. " Overview: The History of the Federal Reserve ."

East Tennessee State University. " Neither a Borrower Nor a Lender Be: America Attempts to Collect its War Debts 1922-1934 ," Pages 5-6.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. “ The First 50 Years: A History of the FDIC .”

Federal Reserve History. " Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) .

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. " Deposit Insurance at a Glance ."

J.D. Power. “ U.S. Retail Banks Nail Transition to Digital During Pandemic, J.D. Power Finds .”

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. " About the Fed ."

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. “ Are All Commercial Banks Regulated and Supervised by the Federal Reserve System, or Just Major Commercial Banks? ”

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " The Role of the SEC ."

- A Primer on Important U.S. Banking Laws 1 of 29

- Dodd-Frank Act: What It Does, Major Components, and Criticisms 2 of 29

- Major Regulations Following the 2008 Financial Crisis 3 of 29

- Too Big to Fail: Definition, History, and Reforms 4 of 29

- Volcker Rule: Definition, Purpose, How It Works, and Criticism 5 of 29

- Understanding the Basel III International Regulations 6 of 29

- What Is Basel I? Definition, History, Benefits, and Criticism 7 of 29

- Basel II: Definition, Purpose, Regulatory Reforms 8 of 29

- Basel III: What It Is, Capital Requirements, and Implementation 9 of 29

- What Basel IV Means for U.S. Banks 10 of 29

- A Brief History of U.S. Banking Regulation 11 of 29

- The Evolution of Banking Over Time 12 of 29

- How the Banking Sector Impacts Our Economy 13 of 29

- What Agencies Oversee U.S. Financial Institutions? 14 of 29

- Dual Banking System: Meaning, History, Pros and Cons 15 of 29

- Glass-Steagall Act of 1933: Definition, Effects, and Repeal 16 of 29

- Bancassurance: Definition, How It Works, Pros & Cons 17 of 29

- Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA): Definition and Requirements 18 of 29

- Bank Secrecy Act (BSA): Definition, Purpose, and Effects 19 of 29

- How Banking Works, Types of Banks, and How To Choose the Best Bank for You 20 of 29

- Chartered Bank: Explanation, History and FAQs 21 of 29

- Nonbank Financial Institutions: What They Are and How They Work 22 of 29

- Shadow Banking System: Definition, Examples, and How It Works 23 of 29

- Islamic Banking and Finance Definition: History and Example 24 of 29

- What Is Regulation E in Electronic Fund Transfers (EFTs)? 25 of 29

- What Is Regulation CC? Definition, Purpose and How It Works 26 of 29

- Regulation DD: What it is, How it Works, FAQ 27 of 29

- Regulation W: Definition in Banking and When It Applies 28 of 29

- Deregulation: Definition, History, Effects, and Purpose 29 of 29

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/skyscrapers-at-new-york-stock-exchange--view-from-below-944864660-30759ac5b1ec48709797ee6152d096d5.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

KPMG Personalization

- Rethinking new business models for banking

Adapting platforms, ecosystems, payments and data for the future, the banking business model has proven to be resilient to disruption.

- Share Share close

- Download Rethinking new business models for banking pdf Opens in a new window

- 1000 Save this article to my library

- View Print friendly version of this article Opens in a new window

- Go to bottom of page

- Home ›

- Insights ›

Tech trends | Adapting the business model | Essential building blocks | A roadmap for adoption | Call to action

Innovations that change the way value is offered to consumers threaten the integrity and resilience of the traditional banking model.

New trends in financial service offerings such as embedded finance and decentralized finance threatens the integrity of the traditional banking business model. Examples include Uber’s embedded payments and Afterpay’s cannibalization of unsecured consumer credit. These trends also eroded the value of the ‘trust premium’ banks have held for so long. For example, Nano Home Loans, a non-bank fintech lender established in 2019, offers to approve home loans at highly competitive rates within ten minutes of an online application; this value proposition has resulted in faster-than-system growth rates.

While fintech and innovators dismember the banking value chain, incumbents also face the very real threat of highly capitalized tech giants. Many with deep customer connections and loyalty, are stepping directly into financial services, potentially redefining the category. For example, although Google has abandoned plans to launch Google Plex (a transaction account for Google Pay), the proposition found strong consumer endorsement of innovative features that embedded financial services into everyday lifestyle choices.

Finally, regulators are deliberately adjusting their posture to help increase competition (e.g., open banking) and reduce entry barriers (e.g., the Restricted ADI offers a limited risk fast track for small challenger banks to start operating as a bank in Australia). Consequently, banks are (and should be) exploring alternative business models to deepen their value pools, entrench customer relationships and expand their value propositions.

As banks evolve their market role, they will likely also need to adapt their business models. Many of the innovations that have been a threat may also be a source of strategic strength as they incorporate them to complement their core.

Adapting the business model — platforms and ecosystems

Although platforms and ecosystems are not mutually exclusive, they are distinct. Platforms can help reduce market friction by connecting suppliers with the consumer, while ecosystems orchestrate complementary value propositions focused on a pattern of customer needs (Fig. 1).

By adopting these innovative business model options, banks can complement their basic banking model (deposits, loans, transactions) and market strengths (e.g., scale of customer franchise, valuable banking licenses, strength of balance sheet) with new value propositions to help differentiate and deepen customer relationships.

For example, Goldman Sachs pivoted to become more like a platform, expanding its portfolio into consumer banking by deploying the Marcus offering, including a credit card partnership with Apple. A goal for Marcus has been to establish banking as-a-service — a platform business.

Meanwhile, DBS Singapore has built DBS Marketplace to orchestrate ecosystems of partnerships offering value propositions shaped to address specific lifecycle needs experienced by their customers, such as car ownership. This ecosystem model deepens the bank’s relationship with their customers and keeps value circulating within the ecosystem.

Essential building blocks

Three foundational capability building blocks are essential to establish either platform or ecosystem, business models:

- Value orchestration: This includes establishing, coordinating and governing participation (partner management) while also measuring the value of involvement (ecosystems or platforms) to help generate more value than the sum of the parts.

- Data-driven insights: This is the ability to convert raw data into valuable insights on customers and operations. Harnessing the power of data can lead to continuous improvement, validation through experimentation and innovation (including accidental discovery through sophisticated pattern analysis); increasingly, this is machine-driven as AI and other advanced analytics tools become mainstream and accessible.

- Digital interoperability: This refers kpmg.com.au to the ability to safely exchange information and drive functionality between participants, including orchestrating end-to-end processes across multiple participants.

Bringing these to life in a banking context involves building blocks that need to be augmented by the basic banking capabilities of financial management, payments, and risk management.

Payments are a significant capability for banks battling for consumer relevancy. Payments provide a cohesive capability for both platforms or ecosystems and maintains a connection with the basic banking value proposition (cash, credit, and transaction). It also works to generate valuable contextual and behavioral data.

A roadmap for adoption

In KPMG professionals’ experience, banks that choose to adapt and future proof their business model should start the transformation by exploring three steps (see Fig. 2).

Assess capability maturity: Does the bank have the foundational capabilities needed to deploy the future business model effectively? If not, start work immediately as this is an investment with no regrets, while, in parallel, work on the other two steps.

Evaluate the bank’s role in the market: How will the bank differentiate along the spectrum of a ‘utility bank’ to an ‘intimate bank’? This can be unlocked by looking at what strengths the bank already has (e.g., if its cost discipline, it may be more suited to a ‘utility’ play).

Identify adaptions to the current business model: Does the bank need to adapt its historical business model by incorporating a platform or ecosystem play?

Fig. 2. Roadmap to adapt the banking business model

Call to action

The banking industry faces a volatile future, but one that is rich with opportunity. KPMG professionals believe banks that prepare to adapt their business models now by establishing the basic capabilities of the future and agreeing between the board and executive on the bank’s role will likely be best positioned to take advantage of those rich opportunities.

This article is featured in Frontiers in Finance – Resilient and relevant

Explore other articles › Subscribe to receive the latest financial services insights directly to your inbox ›

Frontiers in Finance

Download the report (pdf 2.5 mb), connect with us.

- Find office locations kpmg.findOfficeLocations

- Email us kpmg.emailUs

- Social media @ KPMG kpmg.socialMedia

- Request for proposal

Stay up to date with what matters to you

Gain access to personalized content based on your interests by signing up today

Browse articles, set up your interests , or View your library .

You've been a member since

Explore more chapters

Latest market insights and forward-looking perspectives for financial services leaders and professionals.

Latest market insights and forward-looking perspectives for financial services leaders.

The leaders are uncovering new ways to accelerate and scale their innovation

Everyone from central banks to businesses are eyeing cryptoassets.

Platform models are changing the game for financial services firms.

The New Equation

Executive leadership hub - What’s important to the C-suite?

Tech Effect

Shared success benefits

Loading Results

No Match Found

The commercial banking business model is changing

A more strategic approach begins with addressing how to effectively meet client needs.

While banks of all sizes are evaluating technology-led transformation, their conversations are often limited to functional improvements such as onboarding or credit decisioning. This kind of around-the-edges experimentation might enhance customer experience and improve efficiency, but it lacks the depth necessary to differentiate and define the bank over the next three to five years.

We believe a more strategic approach begins with addressing how to effectively meet client needs—needs that keep shifting due to the growing use of technology and the entry of nontraditional competitors. In fact, a number of basic banking products already have shifted beyond the control of the bank itself. Non-banks are displacing an increasingly large part of the commercial lending market, and a growing number of companies are building payments and treasury management operations in-house.

Download The commercial banking business model is changing

Three principles to shape the next move, 1. m&a is an option, but will not solve the problem alone.

Scale-driven advantage is often mentioned as a requirement for serving the largest segments of the market in the most efficient and technology-enabled manner. However, the ability to reach the “needed” scale of a top five bank through consolidation is highly unlikely. Many smaller banks will need to find other ways to outflank their larger competitors and maintain or increase their relevancy.

2. Embrace data, but only if committed to data guiding business decisions

Can banks continuously adapt to improve how they use data? In our experience, most institutions are very good at understanding their customers but this is now a baseline expectation for how the industry uses data. Rather, banks should begin to ask whether they are linking their data to business decisions and adjusting their business processes accordingly. Few organizations have made this transition smoothly.

3. Counter the tech spend of universal banks with an ecosystem approach

New digital technologies are raising the pressure to use IT to the company’s advantage rather than using it to support the business. Most detractors will point to the disparity in tech spend where scale has an overwhelming advantage—top universal banks spend 12 times that of the top regional banks on technology.

But this unreachable technology investment can be replicated as long as the costs associated with the commodity aspects are reduced or shared. One option is with an open architecture, financial institutions can leverage larger ecosystems of innovation without incurring heavy capital and maintenance costs.

The traditional service model grounded in local relationships and substantial technology spend may no longer be viable. As the largest US banks grow significantly faster than their regional competitors and the structural shifts continue in core areas such as corporate, the long-standing dynamics will be reshaped.

Given this evolution in commercial banking, a strategy of how to replicate the unreachable - through novel uses of data, partnerships, and technology flexibility - will be crucial. Outspending the Big Three, or out-innovating tech-based competitors, has become a nearly insurmountable task.

{{filterContent.facetedTitle}}

{{item.publishDate}}

{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

Principal, Strategy&, PwC US

Tel: +1 (617) 515 6497

Roland Kastoun

Asset and Wealth Management Consulting Solutions Leader, PwC US

Rahul Wadhawan

© 2017 - 2024 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details.

- Data Privacy Framework

- Cookie info

- Terms and conditions

- Site provider

- Your Privacy Choices

- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2021

Financial technology and the future of banking

- Daniel Broby ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5482-0766 1

Financial Innovation volume 7 , Article number: 47 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

52 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper presents an analytical framework that describes the business model of banks. It draws on the classical theory of banking and the literature on digital transformation. It provides an explanation for existing trends and, by extending the theory of the banking firm, it illustrates how financial intermediation will be impacted by innovative financial technology applications. It further reviews the options that established banks will have to consider in order to mitigate the threat to their profitability. Deposit taking and lending are considered in the context of the challenge made from shadow banking and the all-digital banks. The paper contributes to an understanding of the future of banking, providing a framework for scholarly empirical investigation. In the discussion, four possible strategies are proposed for market participants, (1) customer retention, (2) customer acquisition, (3) banking as a service and (4) social media payment platforms. It is concluded that, in an increasingly digital world, trust will remain at the core of banking. That said, liquidity transformation will still have an important role to play. The nature of banking and financial services, however, will change dramatically.

Introduction

The bank of the future will have several different manifestations. This paper extends theory to explain the impact of financial technology and the Internet on the nature of banking. It provides an analytical framework for academic investigation, highlighting the trends that are shaping scholarly research into these dynamics. To do this, it re-examines the nature of financial intermediation and transactions. It explains how digital banking will be structurally, as well as physically, different from the banks described in the literature to date. It does this by extending the contribution of Klein ( 1971 ), on the theory of the banking firm. It presents suggested strategies for incumbent, and challenger banks, and how banking as a service and social media payment will reshape the competitive landscape.

The banking industry has been evolving since Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena opened its doors in 1472. Its leveraged business model has proved very scalable over time, but it is now facing new challenges. Firstly, its book to capital ratios, as documented by Berger et al ( 1995 ), have been consistently falling since 1840. This trend continues as competition has increased. In the past decade, the industry has experienced declines in profitability as measured by return on tangible equity. This is partly the result of falling leverage and fee income and partly due to the net interest margin (connected to traditional lending activity). These trends accelerated following the 2008 financial crisis. At the same time, technology has made banks more competitive. Advances in digital technology are changing the very nature of banking. Banks are now distributing services via mobile technology. A prolonged period of very low interest rates is also having an impact. To sustain their profitability, Brei et al. ( 2020 ) note that many banks have increased their emphasis on fee-generating services.

As Fama ( 1980 ) explains, a bank is an intermediary. The Internet is, however, changing the way financial service providers conduct their role. It is fundamentally changing the nature of the banking. This in turn is changing the nature of banking services, and the way those services are delivered. As a consequence, in order to compete in the changing digital landscape, banks have to adapt. The banks of the future, both incumbents and challengers, need to address liquidity transformation, data, trust, competition, and the digitalization of financial services. Against this backdrop, incumbent banks are focused on reinventing themselves. The challenger banks are, however, starting with a blank canvas. The research questions that these dynamics pose need to be investigated within the context of the theory of banking, hence the need to revise the existing analytical framework.

Banks perform payment and transfer functions for an economy. The Internet can now facilitate and even perform these functions. It is changing the way that transactions are recorded on ledgers and is facilitating both public and private digital currencies. In the past, banks operated in a world of information asymmetry between themselves and their borrowers (clients), but this is changing. This differential gave one bank an advantage over another due to its knowledge about its clients. The digital transformation that financial technology brings reduces this advantage, as this information can be digitally analyzed.

Even the nature of deposits is being transformed. Banks in the future will have to accept deposits and process transactions made in digital form, either Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) or cryptocurrencies. This presents a number of issues: (1) it changes the way financial services will be delivered, (2) it requires a discussion on resilience, security and competition in payments, (3) it provides a building block for better cross border money transfers and (4) it raises the question of private and public issuance of money. Braggion et al ( 2018 ) consider whether these represent a threat to financial stability.

The academic study of banking began with Edgeworth ( 1888 ). He postulated that it is based on probability. In this respect, the nature of the business model depends on the probability that a bank will not be called upon to meet all its liabilities at the same time. This allows banks to lend more than they have in deposits. Because of the resultant mismatch between long term assets and short-term liabilities, a bank’s capital structure is very sensitive to liquidity trade-offs. This is explained by Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ). They explain that this makes a bank a’relationship lender’. In effect, they suggest a bank is an intermediary that has borrowed from other investors.

Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ) argue a lender can negotiate repayment obligations and that a bank benefits from its knowledge of the customer. As shall be shown, the new generation of digital challenger banks do not have the same tradeoffs or knowledge of the customer. They operate more like a broker providing a platform for banking services. This suggests that there will be more than one type of bank in the future and several different payment protocols. It also suggests that banks will have to data mine customer information to improve their understanding of a client’s financial needs.

The key focus of Diamond and Rajan ( 2000 ), however, was to position a traditional bank is an intermediary. Gurley and Shaw ( 1956 ) describe how the customer relationship means a bank can borrow funds by way of deposits (liabilities) and subsequently use them to lend or invest (assets). In facilitating this mediation, they provide a service whereby they store money and provide a mechanism to transmit money. With improvements in financial technology, however, money can be stored digitally, lenders and investors can source funds directly over the internet, and money transfer can be done digitally.

A review of financial technology and banking literature is provided by Thakor ( 2020 ). He highlights that financial service companies are now being provided by non-deposit taking contenders. This paper addresses one of the four research questions raised by his review, namely how theories of financial intermediation can be modified to accommodate banks, shadow banks, and non-intermediated solutions.

To be a bank, an entity must be authorized to accept retail deposits. A challenger bank is, therefore, still a bank in the traditional sense. It does not, however, have the costs of a branch network. A peer-to-peer lender, meanwhile, does not have a deposit base and therefore acts more like a broker. This leads to the issue that this paper addresses, namely how the banks of the future will conduct their intermediation.

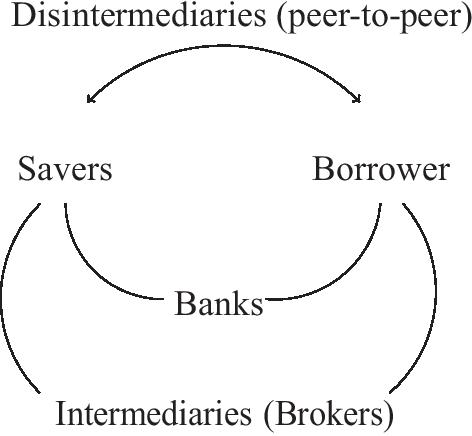

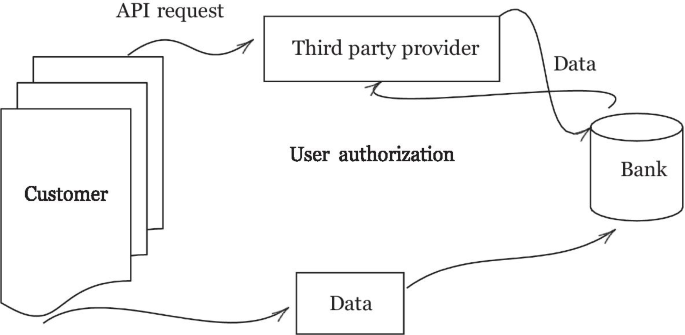

In order to understand what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the nature of the aforementioned intermediation, and the way it is changing. In this respect, there are two key types of intermediation. These are (1) quantitative asset transformation and, (2) brokerage. The latter is a common model adopted by challenger banks. Figure 1 depicts how these two types of financial intermediation match savers with borrowers. To avoid nuanced distinction between these two types of intermediation, it is common to classify banks by the services they perform. These can be grouped as either private, investment, or commercial banking. The service sub-groupings include payments, settlements, fund management, trading, treasury management, brokerage, and other agency services.

How banks act as intermediaries between lenders and borrowers. This function call also be conducted by intermediaries as brokers, for example by shadow banks. Disintermediation occurs over the internet where peer-to-peer lenders match savers to lenders

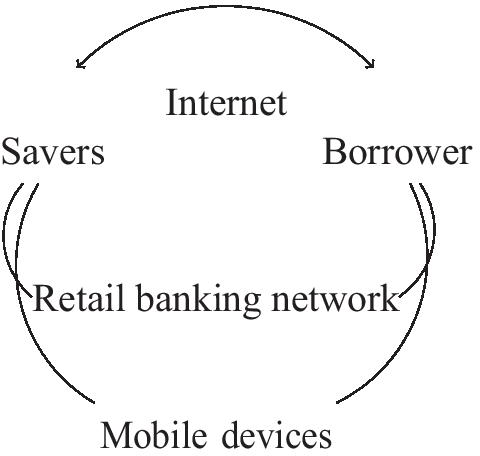

Financial technology has the ability to disintermediate the banking sector. The competitive pressures this results in will shape the banks of the future. The channels that will facilitate this are shown in Fig. 2 , namely the Internet and/or mobile devices. Challengers can participate in this by, (1) directly matching borrows with savers over the Internet and, (2) distributing white labels products. The later enables banking as a service and avoids the aforementioned liquidity mismatch.

The strategic options banks have to match lenders with borrowers. The traditional and challenger banks are in the same space, competing for business. The distributed banks use the traditional and challenger banks to white label banking services. These banks compete with payment platforms on social media. The Internet heralds an era of banking as a service

There are also physical changes that are being made in the delivery of services. Bricks and mortar branches are in decline. Mobile banking, or m-banking as Liu et al ( 2020 ) describe it, is an increasingly important distribution channel. Robotics are increasingly being used to automate customer interaction. As explained by Vishnu et al ( 2017 ), these improve efficiency and the quality of execution. They allow for increased oversight and can be built on legacy systems as well as from a blank canvas. Application programming interfaces (APIs) are bringing the same type of functionality to m-banking. They can be used to authorize third party use of banking data. How banks evolve over time is important because, according to the OECD, the activity in the financial sector represents between 20 and 30 percent of developed countries Gross Domestic Product.

In summary, financial technology has evolved to a level where online banks and banking as a service are challenging incumbents and the nature of banking mediation. Banking is rapidly transforming because of changes in such technology. At the same time, the solving of the double spending problem, whereby digital money can be cryptographically protected, has led to the possibility that paper money will become redundant at some point in the future. A theoretical framework is required to understand this evolving landscape. This is discussed next.

The theory of the banking firm: a revision

In financial theory, as eloquently explained by Fama ( 1980 ), banking provides an accounting system for transactions and a portfolio system for the storage of assets. That will not change for the banks of the future. Fama ( 1980 ) explains that their activities, in an unregulated state, fulfil the Modigliani–Miller ( 1959 ) theorem of the irrelevance of the financing decision. In practice, traditional banks compete for deposits through the interest rate they offer. This makes the transactional element dependent on the resulting debits and credits that they process, essentially making banks into bookkeeping entities fulfilling the intermediation function. Since this is done in response to competitive forces, the general equilibrium is a passive one. As such, the banking business model is vulnerable to disruption, particularly by innovation in financial technology.

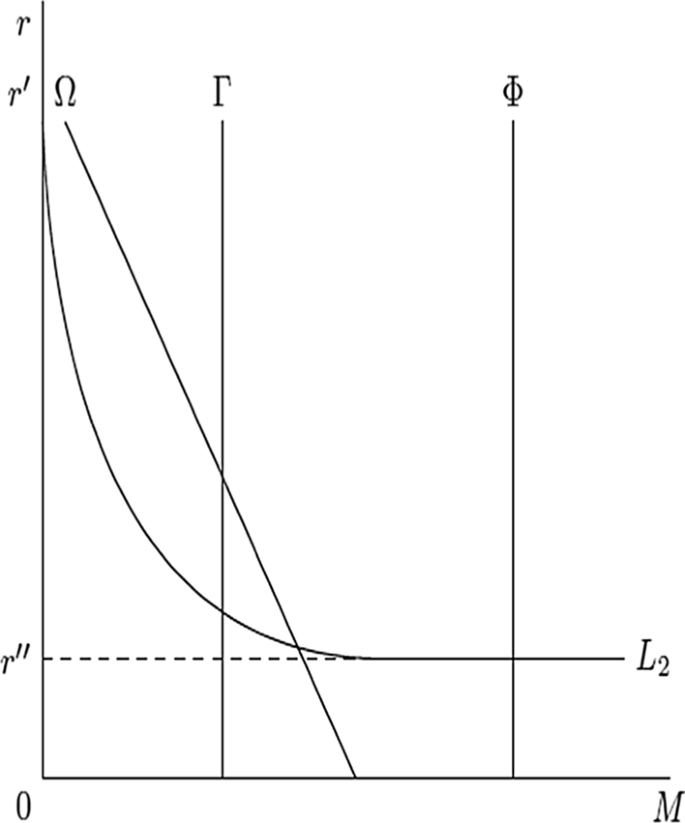

A bank is an idiosyncratic corporate entity due to its ability to generate credit by leveraging its balance sheet. That balance sheet has assets on one side and liabilities on the other, like any corporate entity. The assets consist of cash, lending, financial and fixed assets. On the other side of the balance sheet are its liabilities, deposits, and debt. In this respect, a bank’s equity and its liabilities are its source of funds, and its assets are its use of funds. This is explained by Klein ( 1971 ), who notes that a bank’s equity W , borrowed funds and its deposits B is equal to its total funds F . This is the same for incumbents and challengers. This can be depicted algebraically if we let incumbents be represented by Φ and challengers represented by Γ:

Klein ( 1971 ) further explains that a bank’s equity is therefore made up of its share capital and unimpaired reserves. The latter are held by a bank to protect the bank’s deposit clients. This part is also mandated by regulation, so as to protect customers and indeed the entire banking system from systemic failure. These protective measures include other prudential requirements to hold cash reserves or other liquid assets. As shall be shown, banking services can be performed over the Internet without these protections. Banking as a service, as this phenomenon known, is expected to increase in the future. This will change the nature of the protection available to clients. It will change the way banks transform assets, explained next.

A bank’s deposits are said to be a function of the proportion of total funds obtained through the issuance of the ith deposit type and its total funds F , represented by α i . Where deposits, represented by Bs , are made in the form of Bs (i = 1 *s n) , they generate a rate of interest. It follows that Si Bs = B . As such,

Therefor it can be said that,

The importance of Eq. 3 is that the balance sheet can be leveraged by the issuance of loans. It should be noted, however, that not all loans are returned to the bank in whole or part. Non-performing loans reduce the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet and act as a constraint on capital, and therefore new lending. Clearly, this is not the case with banking as a service. In that model, loans are brokered. That said, with the traditional model, an advantage of financial technology is that it facilitates the data mining of clients’ accounts. Lending can therefore be more targeted to borrowers that are more likely to repay, thereby reducing non-performing loans. Pari passu, the incumbent bank of the future will therefore have a higher risk-adjusted return on capital. In practice, however, banking as a service will bring greater competition from challengers and possible further erosion of margins. Alternatively, some banks will proactively engage in partnerships and acquisitions to maintain their customer base and address the competition.

A bank must have reserves to meet the demand of customers demanding their deposits back. The amount of these reserves is a key function of banking regulation. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision mandates a requirement to hold various tiers of capital, so that banks have sufficient reserves to protect depositors. The Committee also imposes a framework for mitigating excessive liquidity risk and maturity transformation, through a set Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio.

Recent revisions of theory, because of financial technology advances, have altered our understanding of banking intermediation. This will impact the competitive landscape and therefor shape the nature of the bank of the future. In this respect, the threat to incumbent banks comes from peer-to-peer Internet lending platforms. These perform the brokerage function of financial intermediation without the use of the aforementioned banking balance sheet. Unlike regulated deposit takers, such lending platforms do not create assets and do not perform risk and asset transformation. That said, they are reliant on investors who do not always behave in a counter cyclical way.

Financial technology in banking is not new. It has been used to facilitate electronic markets since the 1980’s. Thakor ( 2020 ) refers to three waves of application of financial innovation in banking. The advent of institutional futures markets and the changing nature of financial contracts fundamentally changed the role of banks. In response to this, academics extended the concept of a bank into an entity that either fulfills the aforementioned functions of a broker or a qualitative asset transformer. In this respect, they connect the providers and users of capital without changing the nature of the transformation of the various claims to that capital. This transformation can be in the form risk transfer or the application of leverage. The nature of trading of financial assets, however, is changing. Price discovery can now be done over the Internet and that is moving liquidity from central marketplaces (like the stock exchange) to decentralized ones.

Alongside these trends, in considering what the bank of the future will look like, it is necessary to understand the unregulated lending market that competes with traditional banks. In this part of the lending market, there has been a rise in shadow banks. The literature on these entities is covered by Adrian and Ashcraft ( 2016 ). Shadow banks have taken substantial market share from the traditional banks. They fulfil the brokerage function of banks, but regulators have only partial oversight of their risk transformation or leverage. The rise of shadow banks has been facilitated by financial technology and the originate to distribute model documented by Bord and Santos ( 2012 ). They use alternative trading systems that function as electronic communication networks. These facilitate dark pools of liquidity whereby buyers and sellers of bonds and securities trade off-exchange. Since the credit crisis of 2008, total broker dealer assets have diverged from banking assets. This illustrates the changed lending environment.

In the disintermediated market, banking as a service providers must rely on their equity and what access to funding they can attract from their online network. Without this they are unable to drive lending growth. To explain this, let I represent the online network. Extending Klein ( 1971 ), further let Ψ represent banking as a service and their total funds by F . This state is depicted as,

Theoretically, it can be shown that,

Shadow banks, and those disintermediators who bypass the banking system, have an advantage in a world where technology is ubiquitous. This becomes more apparent when costs are considered. Buchak et al. ( 2018 ) point out that shadow banks finance their originations almost entirely through securitization and what they term the originate to distribute business model. Diversifying risk in this way is good for individual banks, as banking risks can be transferred away from traditional banking balance sheets to institutional balance sheets. That said, the rise of securitization has introduced systemic risk into the banking sector.

Thus, we can see that the nature of banking capital is changing and at the same time technology is replacing labor. Let A denote the number of transactions per account at a period in time, and C denote the total cost per account per time period of providing the services of the payment mechanism. Klein ( 1971 ) points out that, if capital and labor are assumed to be part of the traditional banking model, it can be observed that,

It can therefore be observed that the total service charge per account at a period in time, represented by S, has a linear and proportional relationship to bank account activity. This is another variable that financial technology can impact. According to Klein ( 1971 ) this can be summed up in the following way,

where d is the basic bank decision variable, the service charge per transaction. Once again, in an automated and digital environment, financial technology greatly reduces d for the challenger banks. Swankie and Broby ( 2019 ) examine the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the evaluation of banking risk and conclude that it improves such variables.

Meanwhile, the traditional banking model can be expressed as a product of the number of accounts, M , and the average size of an account, N . This suggests a banks implicit yield is it rate of interest on deposits adjusted by its operating loss in each time period. This yield is generated by payment and loan services. Let R 1 depict this. These can be expressed as a fraction of total demand deposits. This is depicted by Klein ( 1971 ), if one assumes activity per account is constant, as,

As a result, whether a bank is structured with traditional labor overheads or built digitally, is extremely relevant to its profitability. The capital and labor of tradition banks, depicted as Φ i , is greater than online networks, depicted as I i . As such, the later have an advantage. This can be shown as,

What Klein (1972) failed to highlight is that the banking inherently involves leverage. Diamond and Dybving (1983) show that leverage makes bank susceptible to run on their liquidity. The literature divides these between adverse shock events, as explained by Bernanke et al ( 1996 ) or moral hazard events as explained by Demirgu¨¸c-Kunt and Detragiache ( 2002 ). This leverage builds on the balance sheet mismatch of short-term assets with long term liabilities. As such, capital and liquidity are intrinsically linked to viability and solvency.

The way capital and liquidity are managed is through credit and default management. This is done at a bank level and a supervisory level. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision applies capital and leverage ratios, and central banks manage interest rates and other counter-cyclical measures. The various iterations of the prudential regulation of banks have moved the microeconomic theory of banking from the modeling of risk to the modeling of imperfect information. As mentioned, shadow and disintermediated services do not fall under this form or prudential regulation.

The relationship between leverage and insolvency risk crucially depends on the degree of banks total funds F and their liability structure L . In this respect, the liability structure of traditional banks is also greater than online networks which do not have the same level of available funds, depicted as,

Diamond and Dybvig ( 1983 ) observe that this liability structure is intimately tied to a traditional bank’s assets. In this respect, a bank’s ability to finance its lending at low cost and its ability to achieve repayment are key to its avoidance of insolvency. Online networks and/or brokers do not have to finance their lending, simply source it. Similarly, as brokers they do not face capital loss in the event of a default. This disintermediates the bank through the use of a peer-to-peer environment. These lenders and borrowers are introduced in digital way over the internet. Regulators have taken notice and the digital broker advantage might not last forever. As a result, the future may well see greater cooperation between these competing parties. This also because banks have valuable operational experience compared to new entrants.

It should also be observed that bank lending is either secured or unsecured. Interest on an unsecured loan is typically higher than the interest on a secured loan. In this respect, incumbent banks have an advantage as their closeness to the customer allows them to better understand the security of the assets. Berger et al ( 2005 ) further differentiate lending into transaction lending, relationship lending and credit scoring.

The evolution of the business model in a digital world