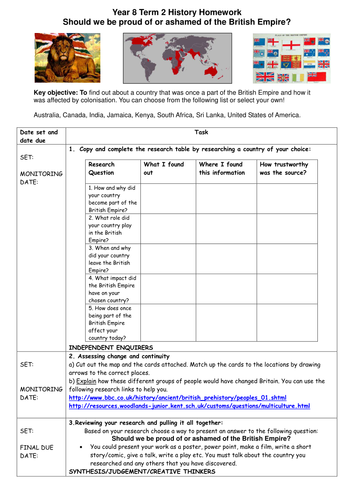

15 History Project Ideas for High School Students

Indigo Research Team

If you have a deep interest in past events and feel a connection to different periods, pursuing history projects might be for you.

Studying history allows you to understand the reasons behind decisions made over time and gives you valuable skills that can contribute to shaping a better future. Not to mention, passion projects for high school students have become increasingly important to make your college application better.

So, if you are interested in history, here is the list of 15 creative ideas that you can start now:

Creative Ideas for History Projects

1. comparative research studies: history vs present times.

Comparing history and present times through research could be a great history research project idea for high school students. This study offers a valuable opportunity to delve into the complexities of historical events and societies. By examining two or more instances, you can develop critical thinking and analytical skills while uncovering patterns and trends that may not be apparent at first glance. These studies provide an avenue for exploring the similarities and differences between different periods and places, shedding light on the factors that shape societies and influence historical outcomes.

When engaging in a history research project, it is crucial to start by selecting specific historical events or societies to compare. This allows you to focus on research efforts effectively. In addition to investigating political, economic, social, and cultural aspects, it is equally important to dive into the causes and consequences of these events. If you need help to do research, you can always find research mentors who can guide you through the process.

2. Israel-Palestine conflict

The war between Israel and Palestine is one of the trending history project topics , so high school students can get a lot of information online. Learn about the root cause of the conflict by researching the historical background, key events, religion, and cultural values.

3. Ancient Civilizations scrapbook

A virtual Scrapbook is another creative idea for a history project for students. You can choose your favorite ancient civilization and start collecting old images and maps. Join maps and images and write short descriptions for the readers. Do extensive research and learn about their daily life activities to showcase their lifestyle. This project will spark your creativity.

4. Historical Fashion Show

If you have a passion for trends and fashion, the evolution of style is a perfect history project idea. Choose a specific period to take a stroll through the history. Your historical fashion show project will be more interesting if you consider a large period. Conduct research and present how ancient people used to cover their bodies. If you have enough time, you can create simple costumes from ancient civilizations to represent different eras. The video below can also be your reference in creating your historical fashion project.

5. History Box

High school students can create a history project by transforming historical events into three-dimensional masterpieces. You can choose your favorite history projects, such as a big discovery, a famous battle, or any other historical event that inspires you.

Take a shoe box, colored paper, and pens to transform your history project idea into a 3D scene. Incorporate small details like landscapes, buildings, and figures to tell the whole story. Write captions on each item to help other students understand the history.

6. Historical Cooking Show

Calling all foodie students! If you are passionate about cooking, you can try this European history project ideas. Choose your European cuisine and dig deep into how ancient people used to prepare food. Prepare old European dishes and record your adventurous video. Explain the whole recipe and how it reflects the culture of that time.

7. Inventions show

Create a visual show of inventors and inventions. Conduct thorough research, pick a few big inventors, learn about their contributions, and present your knowledge through digital presentation. You can also mention how their inventions changed the lifestyle of that era. This visual showcase will motivate you and your classmates to do something big and create a better future.

8. Historical Comic Show

Create a comic strip by using historical events. Choose a particular era and gather drawings and captions to narrate the key moments. This history project idea will polish your storytelling skills and make history more accessible and entertaining.

9. Podcasts from the Past

Creating a podcast series of historical figures can take your creativity to the next level. Interview "guests" from the past, portraying their achievements, struggles, and impact on society. Use your creativity to make it informative and entertaining for your audience.

10. Timeline Wall

High school students can use a blank wall to showcase significant events of a specific region. Suppose you want to showcase US history, then conduct research and list down important events of the past. Using different colors and markers, you can illustrate events on the wall.

11. Presidential Time Capsule

This is one of the best US history final project ideas. Students can represent different presidents by exploring their political achievements, personal aspects, and societal influences. You can create artifacts to showcase the life of a specific president. This US History project idea will enhance your artistic skills.

12. Oil Board Game

Are you looking for Texas history project ideas? This educational oil board game will allow you to explore the oil industry of Texas. You need extensive research to learn about the boomtown era, economic fluctuations, and the impact of oil discoveries. Players will take on the roles of independent oil entrepreneurs, navigating the economic landscape to strike it rich or face financial pitfalls.

13. ABC Past Book

Students can create an E-book just like a dictionary where each letter represents a historical event of a specific era or region. For example, A stands for Arts & Crafts Movement Worksheet and B stands for Berlin. You can add small captions and illustrations to enhance readability.

14. Black Man Museum

Black Man Museum is one of the outstanding black history project ideas because it allows you to honor the achievements and struggles of people of color. Conduct research and find a few historical black figures, gather all the information about their achievements. You can also share stories of black people in your community. This project will spark your public speaking abilities and deepen your understanding of the diverse contributions to society.

Following are a few more black history project ideas:

- The Montgomery bus boycott

- The civil rights movement

- Black women’s history

- The black panthers

- Contribution of black teachers in Society

15. Documentary on the Freedom Movement

If you’re passionate about India’s history and looking for Indian history project ideas, you can create a Documentary on the Freedom Movement. Find elders from your family or your community who witnessed the freedom of India and record their interviews. Ask about their experiences, sacrifices, and contributions to the freedom movement. This could be a good history research idea because the diverse perspectives can help you make your project more interesting.

How to Create a Successful History Project for a High School Student?

Before choosing your history project, ask yourself a few questions what do you like the most about history? How much time do you have to complete the project and what are your educational goals? These questions will help you choose the right project that will stand out from the crowd.

Here are some more tips that will make your history project rewarding.

1. Identify Your Interest

The common rule to start anything is your interest, the more you enjoy doing something, the more it will motivate you to finish the project. Start thinking about the historical events, periods, and figures that capture your attention.

2. Consider your Class Curriculum

To obtain history project ideas, you could also browse on school's history book to explore topics that you find interesting. You can also consider themes that haven’t been covered in your class yet. Choosing a topic from your class content will help you to understand better and perform well in final exams.

3. Explore Current Events

Consider current issues that have relevance to history. Connecting the dots of the present to the past can make your project more engaging and memorable.

4. Create an Engaging Documentation

Creating visually appealing documentation is not only aesthetically pleasing but also a powerful tool for exploring historical events. Start with providing a visual representation of the chronological order of key events, timelines help learners connect the dots and develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Visual cues capture people’s attention and spark their curiosity, encouraging them to dig deeper into the interconnectedness between historical events and notable figures. Ultimately, creating engaging documentation will always be beneficial for your college application or future careers.

5. Use Historical Books and Resources

When working on a history project, it is essential to utilize reliable historical books and resources. These sources provide accurate and credible information that can support your research and strengthen the credibility of your project.

Start by identifying reputable books written by historians or experts in the field. Look for well-researched, peer-reviewed, and widely recognized books within the academic community. These books often provide comprehensive coverage of knowledge that you can rely on.

There are endless creative ideas for history projects. You should choose something that you’re passionate about. We assume that this article has given you a project idea and by choosing the above tips, you can bring life to your history project.

History is no doubt one of the most interesting topics to explore in a research project. If you want to start your research journey, the Indigo Research Program is here to transform your idea into reality. We will pair you with mentors from top universities and turn your project into publishable research.

101+ Interesting History Project Ideas For Students

Finding a good history project idea can be tricky, but with some help, students of all ages can pick a fascinating, doable, and educational topic. From biographies of influential people to historical events or places, there are many exciting ways to learn about the past.

This blog post will explore potential history project ideas from different periods, locations, and views. Whether you want to understand your family’s history better, focus on a topic that connects to current events, or satisfy your curiosity about the past, you will find inspiration.

With the right history project idea, you can gain valuable research skills while diving into a subject you’re passionate about. From Native American culture to the Civil Rights Movement and more, read on for historical project suggestions that will teach and engage you.

Are you struggling with History Assignment Help ? Do you need assistance in getting the best and A+ Quality human-generated solutions? Hire our tutors to get unique assignment solutions before the assignment deadline.

What Are History Projects?

Table of Contents

History projects are assignments, often given in school, where students research and present information about a particular topic or period from history. They typically require students to investigate using libraries, museums, interviews, online sources, and other methods to find useful facts and materials.

Students then synthesize what they learned into a project that demonstrates their knowledge. Common types of history projects include research papers, exhibits, documentaries, posters, presentations, websites, and more.

The format allows students to understand history through hands-on learning and exploration. Here are some key reasons history projects are essential:

- Develop research and critical thinking skills

- Gain perspective on how past events shape the present

- Make history come alive through creativity and engagement

- Learn to evaluate and analyze historical sources

- Practice presentation and communication abilities

- Promote an appreciation for the study of history

Here are 103 history project ideas for students, categorized to help you find a topic that suits your interests.

Ancient Civilizations

- The Rise & Fall of the Roman Empire

- Life in Ancient Egypt: Pharaohs, Pyramids, and Daily Life

- Contributions of Ancient Greece to Modern Civilization

- Mesopotamia: The Cradle of Civilization

- Indus Valley Civilization: Mystery of the Lost Civilization

- Ancient Chinese Dynasties: Han, Qin, and Tang

Medieval Times

- Knights and Chivalry: Code of Honor in Medieval Europe

- The Black Death: Impact on Europe in the 14th Century

- Feudalism: Structure of Medieval Society

- Crusades: Holy Wars and Their Consequences

- Vikings: Raiders of the North Sea

Renaissance and Enlightenment

- Renaissance Art and its Influences

- The Scientific Revolution: Changing the Paradigm

- Enlightenment Thinkers: Ideas That Shaped Modern Society

- The Age of Exploration: Discoveries and Consequences

- The Printing Press: Revolutionizing Communication

Also Read:- STEM Project Ideas For Middle School

Colonial America

- 17. Jamestown vs. Plymouth: Contrasting Early American Colonies

- Salem Witch Trials: Hysteria in Colonial Massachusetts

- Founding Fathers: Architects of the United States

- The Triangle Trade: Economic Forces in Colonial America

- Indigenous Peoples and European Contact

American Revolution

- Causes and Effects of the American Revolution

- Revolutionary War Battles: Turning Points and Strategies

- Declaration of Independence: Crafting a Nation’s Identity

- The Role of Women in the Revolutionary Era

- African Americans in the Revolutionary War

19th Century

- Industrial Revolution: Impact on Society and Economy

- Manifest Destiny: Expansion Westward in the United States

- Abolitionist Movement: Struggle for the End of Slavery

- Immigration Waves: Contributions of Immigrants in the 1800s

- California Gold Rush: Boomtowns and Prospecting

Civil War and Reconstruction

- Causes of the Civil War: Sectionalism and Tensions

- Battle of Gettysburg: Explore the Turning Point in the Civil War

- Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln’s Bold Move

- Reconstruction Era: Rebuilding the United States

- Freedmen’s Bureau: Aid to Former Slaves

- World War I: Causes, Events, and Consequences

- Trench Warfare: Life on the Front Lines

- Treaty of Versailles: Impact on the Interwar Period

- Rise of Adolf Hitler: Factors Leading to World War II

- Holocaust: Remembering the Atrocities

Cold War Era

- The Cuban Missile Crisis: Tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union

- Space Race: Race for Supremacy in Space Exploration

- McCarthyism: Anti-Communist Hysteria in the United States

- Vietnam War: Causes, Events, and Legacy

- Civil Rights Movement: Struggle for Equality

Post-Cold War

- 47. Fall of the Berlin Wall: Symbol of the End of the Cold War

- Apartheid in South Africa: Nelson Mandela’s Fight for Equality

- The collapse of the Soviet Union: End of the Superpower Era

- Gulf War: Operation Desert Storm

- Rwandan Genocide: Tragedy and International Response

Also Read:- Statistics Project Ideas

Recent History

- 9/11 Attacks: Impact on Global Politics

- War on Terror: U.S. Military Interventions in the Middle East

- Arab Spring: Protests and Political Change in the Middle East

- Brexit: The United Kingdom’s Decision to Leave the EU

- COVID-19 Pandemic: Global Responses and Lessons Learned

Historical Figures

- Alexander the Great: Explore Conqueror of the Ancient World

- Joan of Arc: Explore Heroine of the Hundred Years’ War

- Martin Luther King Jr.: Explore Leader of the Civil Rights Movement

- Winston Churchill: Explore Prime Minister during World War II

- Cleopatra: Queen of Ancient Egypt

Women in History

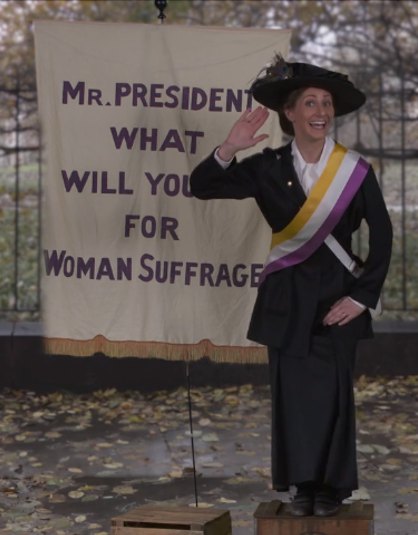

- Suffragette Movement: Struggle for Women’s Right to Vote

- Eleanor Roosevelt: Explore First Lady and Human Rights Advocate

- Marie Curie: Pioneering Scientist in Radiology

- Rosa Parks: Explore Catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement

- Malala Yousafzai: Advocate for Girls’ Education

Cultural History

- Harlem Renaissance: Cultural and Artistic Flourishing

- Beat Generation: Literary and Cultural Rebellion

- Woodstock Festival: Music and Counterculture in the 1960s

- Mayan Civilization: Art, Architecture, and Culture

- Japanese Tea Ceremony: Tradition and Ritual

Economic History

- Great Depression: Causes and Effects on Global Economies

- 1929 Stock Market Crash: Precursor to the Great Depression

- Keynesian Economics vs. Supply-side Economics

- Gold Rushes: Economic Booms and Busts

- Silicon Valley: Technological Innovation Hub

Social Movements

- LGBTQ+ Rights Movement: Struggles and Achievements

- Environmentalism: Origins and Impact on Policy

- Anti-Apartheid Protests: Global Solidarity

- Occupy Movement: Protests Against Economic Inequality

- #MeToo Movement: Addressing Sexual Harassment and Assault

Military History

- Sun Tzu and the Art of War: Ancient Military Strategy

- Battle of Thermopylae: Spartan Stand Against the Persians

- D-Day Invasion: Allied Assault on Normandy

- Code Talkers: Navajo Language in World War II

- Military Technology Advancements: From Swords to Drones

Historical Artifacts

- Rosetta Stone: Decoding Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

- The Dead Sea Scrolls: Unearthing Ancient Texts

- The Shroud of Turin: Controversy Surrounding the Relic

- The Rosetta Disk: A Modern-Day Rosetta Stone

- The Declaration of Independence: Preserving a National Treasure

Also Read:- Social Studies Fair Project Ideas

Historical Places

- Machu Picchu: Inca Civilization’s Hidden Citadel

- The Acropolis: Symbol of Ancient Greek Civilization

- The Great Wall of China: Construction and Purpose

- The Louvre: Home to Priceless Art and Artifacts

- Auschwitz Concentration Camp: Remembering the Holocaust

Historical Events

- The Great Fire of London: Investigate Destruction and Rebuilding

- The Boston Tea Party: Investigate Prelude to the American Revolution

- The Cuban Revolution: Investigate Fidel Castro and the Rise of Communism

- The Moon Landing: Apollo 11’s Historic Achievement

- The Treaty of Westphalia: Shaping Modern Diplomacy

Historical Science and Medicine

- Hippocrates and the Hippocratic Oath: Foundations of Medicine

- Darwin’s Theory of Evolution: Impact on Biology and Society

These History Project Ideas cover a wide range of historical topics, allowing students to delve into different periods, regions, and themes within history. Students can select projects based on their interests and explore various aspects of human history.

How Do You Plan A History Project?

Here are some tips for planning a successful history project:

- Choose a history topic that interests you and fits the scope of the assignment. Consider a critical event, period, location, historical figure, or cultural phenomenon you want to explore further.

- Research general background information on your topic to help refine and focus your project idea. Determine what’s most important to convey or what questions you want to answer.

- Determine the type of project – will it be a research paper, documentary, website, exhibit, reenactment, or something else? Choose a format that aligns with your topic and allows you to convey what you learned creatively.

- Create a work timeline accounting for research, creating a rough draft, gathering materials, fact-checking, and finalizing the project. Leave time for revisions and editing.

- Locate primary and secondary sources to conduct your research. Use libraries, academic databases, museums, interviews, archives, credible online sources, etc. Evaluate each source for accuracy and credibility.

- Take careful notes and document all sources used, tracking which information comes from each source. This will be important for citations/bibliography later.

- Outline your project and draft a structure before beginning. Use your research to shape the narrative or argument you’ll present.

- Stick to your timeline as you move through the drafting and production process. Review the project requirements and rubric to ensure you meet all expectations.

- Double-check your facts, polish the final product, and practice presenting/explaining your work if required. Revise as needed to create an informative, engaging history project!

How Do You Write A History Project?

Here are some tips for writing a successful history project:

- Craft an introduction that presents your topic and establishes its significance in history. State your central thesis, argument, or purpose for your analysis.

- Provide background context so your reader understands your topic’s setting and circumstances. Give relevant details about time, place, politics, culture, etc.

- Present your research and findings in a logical structure with clear organization. Use sections and headings to divide details and make connections.

- Blend narrative explanation and evidence from sources. Paraphrase, summarize, and directly quote relevant research information to support your points.

- Analyze and interpret your findings to make arguments, draw conclusions, and explain historical significance. Move beyond just restating facts.

- Consider different perspectives and causes when analyzing historical events and figures. Provide context for their motivations and obstacles.

- Use transitions to connect ideas and paragraphs so your writing flows smoothly.

- Define key terms, events, and concepts so readers understand their meaning and historical significance.

- Summarize your main points, emphasize your central argument, and explain why your topic matters.

- Correctly note all sources within the text and in a bibliography using the required citation style.

- Revise your writing to check for clarity, organization, grammar, and spelling before finalizing. Make sure your writing is clear, concise, and compelling.

Final Remarks

In summary, working on a history project gives students an excellent chance to explore the exciting stories of the past. They can build essential skills while exploring different topics that they find exciting. Students can get creative by picking a topic they like, whether it’s for a research paper, a documentary, or a presentation. Being organized, doing careful research, and sticking to deadlines are super important for doing well.

As students learn about ancient civilizations, essential events, incredible people from history, and significant social changes, they understand history better and get better at thinking critically, doing research, and talking to others. History projects make the past feel alive and help us appreciate how history significantly impacts how things are now and what might happen in the future.

Similar Articles

How To Do Homework Fast – 11 Tips To Do Homework Fast

Homework is one of the most important parts that have to be done by students. It has been around for…

How to Write an Assignment Introduction – 6 Best Tips

In essence, the writing tasks in academic tenure students are an integral part of any curriculum. Whether in high school,…

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Find A Local Contest

- Get Started

- Contest Rules & Evaluation

- Find Your Local Contest (Affiliate)

- National Contest

- Classroom Tools

- Teaching Research Skills

- Advising NHD Students

- News & Events

- Why NHD Works

- People of NHD

- Find Your Local Affiliate

- 50 Years of NHD

- Sponsors and Supporters

- Volunteer to Judge

- Alumni Network

Get Started on Your Project

A National History Day ® (NHD) project is your way of presenting your historical argument, research, and interpretation of your topic’s significance in history. NHD projects can be created individually or as part of a group. There are two entry divisions: Junior (grades 6–8) or Senior (grades 9–12). After reading the Contest Rule Book and learning about the annual theme , you’re ready to dig in!

Your Guide to Getting Started

Choose your topic .

A topic is the part of history you want to study. Choose a topic that is interesting to you, that fits the annual theme , and that is not too big and not too small. Studying the entire American Revolution is probably too big. At the same time, studying one decision made by General George Washington on one day in the Revolutionary War might be too small. Just like Goldilocks, find a topic that is “just right.”

Can I select any topic I want?

Absolutely! NHD encourages you to explore historical topics ( local , regional, national, or global ) from any time period. Start by checking with your teacher. Teachers might have certain guidelines specific to their classrooms. All topics also need to be approved by your parent or guardian.

How old should my topic be?

Your topic must be old enough that historians are writing about it. Historians tend to wait until enough time has passed that the topic feels complete and they can answer the “So What?” question about the topic; i.e., why is the topic important to know about? You will answer the same question about your topic.

If you are interested in something that is happening currently or very recently, consider exploring that topic in history. For example, you might be interested in how people today are coping with a dwindling water supply. Look back to struggles over access to water in the past. You might find a great topic that way!

Start Your Research

Once you select a topic, you are ready to begin your research by finding out what was going on before and during the time that your topic occurred. This is called historical context and it’s where historians begin.

Historians use these and other terms when talking about the study of history. Refer to the Student Glossary as you come across historical terms and concepts.

Historical context sets the stage for your topic. To learn about historical context, historians use two key types of resources: primary and secondary sources. Remember to keep track of your research sources so you can create your bibliography.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources tell, analyze, or interpret events. Historians create secondary sources based on their reading of primary sources. Secondary sources are usually written decades, if not centuries, after the event occurred by people who did not live through or participate in the event.

Begin your research with secondary sources to help you build your knowledge of the big picture surrounding your topic. To understand the connections between your topic and the time period, ask yourself:

- Why did my topic happen at this particular time and in this particular place?

- What were the events that came before my topic?

- How was my topic influenced by the economic, social, political, and cultural climate of the time period?

Primary Sources

Primary sources are the most exciting part of history. These are the sources created during the time that the event took place. Be sure to look at primary materials created by as many people as you can. Looking at various viewpoints will help you develop multiple perspectives.

Examples of primary sources include: documents, artifacts, historic sites, songs, or other written and tangible items created during the historical period you are studying.

While it can be tempting to jump right to the primary sources, the historical context of your topic that you learn from secondary sources will help you make sense of the primary sources that you find.

Conducting Interviews

Interviews are not required for an NHD project. Requests to interview historians or other secondary sources are inappropriate. Historians do not interview each other. Instead, you might conduct oral history interviews of those who were eyewitnesses to the events. Oral histories are primary sources. Learn more about g uidelines for conducting interviews and the difference between oral histories and interviews with experts.

Develop a Historical Argument

NHD projects must do more than just tell a story. Historians create a historical argument to state what they will prove through their writing. The historical argument is a clear and specific two or three-sentence statement that contains the how and why of what historians found in their research.

After you do your research and analyze your sources, your ideas about the significance of your topic in history will take shape. Then it is time for you to develop your historical argument.

Your research provides the evidence to support the argument you wish to make.

Example Topic: Battle of Gettysburg

Historical Argument: The Battle of Gettysburg was a major turning point in the U.S. Civil War. It turned the tide of the war from the South to the North. After the battle, Lee’s army would never fight again on Northern soil and the Union army gained confidence.

Select a Contest Category

NHD offers five creative categories in each division (Junior: grades 6–8, or Senior: grades 9–12). The documentary, exhibit, performance, and website categories offer both individual and group participation options. The paper category allows individual participation only. Groups may include two to five students.

Documentary

A documentary is a ten-minute film that uses media (images, video, and sound) to communicate your historical argument, research evidence, and interpretation of your topic’s significance in history.

A documentary should reflect your ability to use audiovisual equipment to communicate your topic’s significance. The documentary category will help you develop skills in using photographs, film, video, audio, computers, and graphic presentations. Your presentation should include primary source materials and also must be an original production. To produce a documentary, you must have access to equipment and be able to operate it.

Documentary Resources

Documentary project checklist, documentary evaluation form, documentary project example 1: baseball diplomacy, documentary project example 2: aiming for a diplomatic future.

An exhibit is a three-dimensional physical and visual representation of your historical argument, research evidence, and interpretation of your topic’s significance in history.

Exhibits use color, images, documents, objects, graphics, and design, as well as words, to tell your story. Exhibits can be interactive experiences by asking viewers to play music, look at a video, or open a door or window to see more documents or photos.

Exhibit Resources

Exhibit project checklist, exhibit evaluation form, exhibit project example 1: black studies now, exhibit project example 2: the radium girls.

A paper is a written format for presenting your historical argument, research evidence, and interpretation of your topic’s significance in history.

A paper is a highly personal and individual effort, and if you prefer to work alone this may be the category for you. Papers depend almost entirely on words to tell the story, and you can usually include more information in a paper than in some of the other categories. Various types of creative writing (for example, fictional diaries, poems, etc.) are permitted but must conform to all general and category rules.

Paper Resources

Paper project checklist, paper evaluation form, paper project example 1: women strike for peace, paper project example 2: soil conservation service, performance.

A performance is a dramatic portrayal of your historical argument, research evidence, and interpretation of your topic’s significance in history.

The performance category is the only one that is presented live. Developing a strong narrative that allows your subject to unfold in a dramatic and visually interesting way is important. Memorizing, rehearsing, and refining your script is essential, so you should schedule time for this in addition to research, writing, costuming, and prop gathering.

Performance Resources

Performance project checklist, performance evaluation form, performance project example 1: caroline chisholm, performance project example 2: debate over the bill of rights.

A website is a collection of interconnected web pages that uses multimedia to communicate your historical argument, research evidence, and interpretation of your topic’s significance in history.

A website should reflect your ability to use website design software and computer technology to communicate your topic’s significance in history. To create an NHD website project, you must use NHDWebCentral ® .

Website Resources

Nhdwebcentral ® instructions, website project checklist, website evaluation form, write your process paper & annotated bibliography.

All NHD projects have two required elements in common—a process paper and an annotated bibliography.

Process Paper

A process paper is a description of how you conducted your research, developed your topic idea, and created your entry. The process paper must also explain the relationship of your topic to the contest theme. You’ll find these and further information about writing your Process Paper in the Contest Rule Book .

Annotated Bibliography

An annotated bibliography is a formatted list of the sources that you used in your research. The main goals of an annotated bibliography are to:

- Give credit to the original authors, avoiding plagiarism

- Show the value of a source to the research

- Reflect varied perspectives with different types of sources

- Provide the source information so that readers can explore those sources on their own

An annotated bibliography is required for all categories. Read the Contest Rule Book to learn about the detailed requirements.

NoodleTools: NHD and NoodleTools partner together to help you organize your research sources. NoodleTools can help you track your sources, take notes, organize your ideas, and create your annotated bibliography. Your teachers can sign up and receive account access for all of their students for one year. The program allows teachers to see the progress their students have made and offer direct electronic feedback.

Find Your Local Contest

National History Day competition begins at the local level. Registration, contest dates, submission deadlines, and further supporting materials are available through each affiliate’s local contest website.

Project Examples

Get inspired by NHD projects submitted in previous years’ contests.

Create an Entry

Resources to help you start and complete your NHD entry

National History Day ®

Influencing the future through discovery of the past

- Job Openings

Read our newsletter for the latest resources, events, and training.

We use cookies to analyze how visitors use our website so we can provide the best possible experience. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device. For more information, please view our Privacy Policy.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Mumbai

ICSE, CBSE study notes & home schooling, management notes, solved assignments

History Project for Class 9 Students: Topics and Sample Projects

March 18, 2024 by studymumbai

Here’s how to make History Projects for Class 9 students. Find sample projects and the best structure to incorporate while making History projects.

General Instructions

Your written work must be complemented with relevant pictures/ photographs. It’s a good practice to use a caption for all the pictures /photographs that you use.

GET INSTANT HELP FROM EXPERTS!

Hire us as project guide/assistant . Contact us for more information

If possible, try and use maps and time-lines where appropriate.

Students are expected to submit the History project in hand-written format in Spiral interleaved book.

Project Structure

You can keep the following structure for the History project, in case the structure is not provided by the school.

Index page – Introduction – Content – Conclusion – Bibliography – Acknowledgements (optional)

The number of pages to be written will be provided by the school. In case, it is not provided, you may write around 4 pages for the main content and about 1 page for each of the remaining sections.

History Project Topics for Class 9

History of Mysore

The objective of this project is to research and present a comprehensive study on the history of Mysore, covering various aspects such as its origins, rulers, cultural evolution, significant events, and contributions to the region and beyond.

You may use the following structure:

1) Index on page- 1

2) Introduction (1 to 2 pages):

Significance of Architecture in the reconstruction of the past. Create a chronological timeline highlighting rulers, and developments in Mysore’s history.

3) Content: (3-4 pages)

Part I: Cultural Heritage: Explore the rich cultural heritage of Mysore, including art, architecture, music, and dance. Part II: Economic and Trade History: Investigate Mysore’s historical economic activities, trade routes, and economic prosperity. Part III: Architectural Heritage: Write about the architectural features of the Mysore palace and the temple you have visited.

4) Conclusion: Write your experience about the Sound and Light Show. (1 page)

Bibliography: (1 page)

List all reference material used: first print (books, magazines etc.) then web sites. If you visited web sites state the exact site/link (not just Google.com!)

6)Acknowledgements (optional): A brief acknowledgement of the people who made this project possible.

StudyMumbai.com is an educational resource for students, parents, and teachers, with special focus on Mumbai. Our staff includes educators with several years of experience. Our mission is to simplify learning and to provide free education. Read more about us .

Related Posts:

- EVS Project for Class 9 Students: Topics and Sample Projects

- Geography Project for Class 9 Students: Topics and…

- History and Civics (Class - IX): Projects / Assignments

- Engaging Class 11 (XI) English Project Topics and Ideas

- How to choose a Research Topic (also find sample topics)

ICSE CLASS NOTES

- ICSE Class 10 . ICSE Class 9

- ICSE Class 8 . ICSE Class 7

- ICSE Class 6 . ICSE Class 5

- ICSE Class 4 . ICSE Class 2

- ICSE Class 2 . ICSE Class 1

ACADEMIC HELP

- Essay Writing

- Assignment Writing

- Dissertation Writing

- Thesis Writing

- Homework Help for Parents

- M.Com Project

- BMM Projects

- Engineering Writing

- Capstone Projects

- BBA Projects

- MBA Projects / Assignments

- Writing Services

- Book Review

- Ghost Writing

- Make Resume/CV

- Create Website

- Digital Marketing

STUDY GUIDES

Useful links.

- Referencing Guides

- Best Academic Websites

- FREE Public Domain Books

- How to Use this Site

- Lessons & Activities

- Interactives & Media

- Museum Artifacts

- Teacher Resources

Lessons & Activities

Search history explorer.

Young People Shake Up Elections (History Proves It) Educator Guide

Becoming US

Head to Head: History Makers

What Will You Stand For? Video Discussion Guide

What Will You Stand For? Video

Educator Guide for World War I: Lesson and Legacies

The Suffragist Educators' Guide for the Classroom Videos

The Suffragist

World War I: Lessons and Legacies

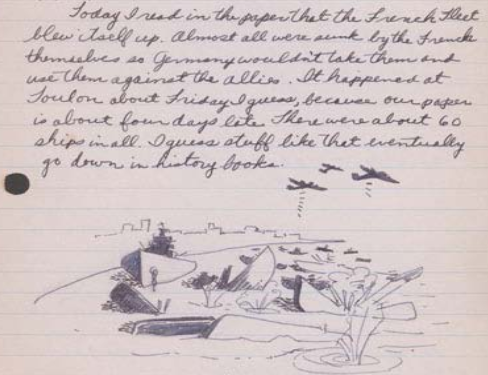

Japanese American Incarceration: The Diary of Stanley Hayami

...If You Traveled On The Underground Railroad

A Boy at War: A Novel of Pearl Harbor

A Boy No More

A Bus of Our Own

A Carp for Kimiko

A Christmas Tree in the White House

A Different Mirror for Young People: A History of Multicultural America

A Fence Away From Freedom: Japanese Americans and World War II

A Multicultural Portrait of Immigration

A Picture Book of Eleanor Roosevelt

Filter resources by:, featured artifact.

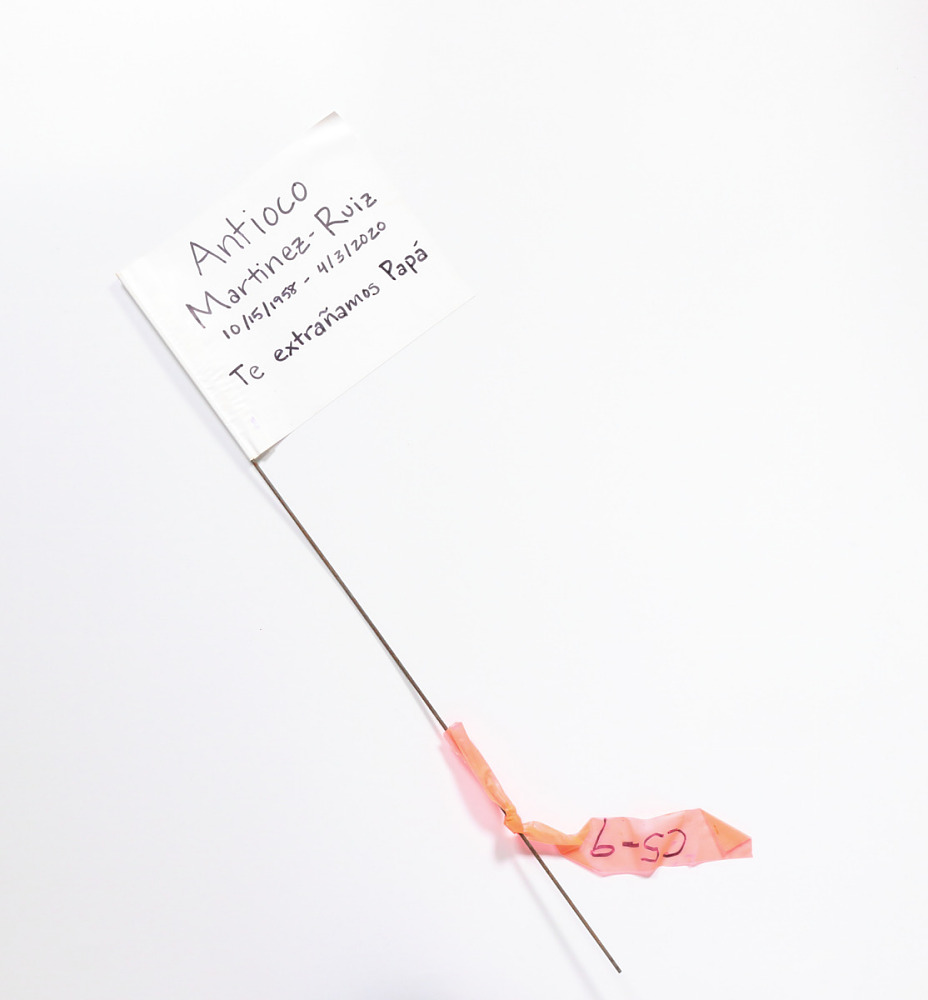

As COVID-19 deaths spiked in 2020, Suzanne Firstenberg’s public art installation "In America: How could this happen…"

Support for Smithsonian's History Explorer is provided by the Verizon Foundation

- Interactives/Media

- Museum/Artifacts

- About History Explorer

- Terms of Use

- Plan Your Visit

- Topical and themed

- Early years

- Special needs

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

Thought-provoking historical projects

Australia and new zealand, international schools, tes resources team.

Inspire inquisitive minds to investigate a variety of historical periods with these captivating project ideas

With the end of term almost in sight, projects are a great way to keep your classes engaged while acquiring new knowledge and developing important skills. Whether they are used to introduce unfamiliar historical periods, explore one in more detail or discover local history, this collection of imaginative project ideas has the power to get students of all ages and abilities thinking more deeply.

Industrial Cities: Research Project.

World War I Research and Project Based Task Cards

History Homework Project for KS3 double pack

History homework projects - Years 7 to 9

History Themed project work for KS3/KS2

Fun Castle Project

Henry VIII - Full Homework Project

World War One Homework Project - a Trench Diary

Local history resources.

22 practical ideas on how to weave Local History into your History lessons

Local History: Culture on Your Doorstep

Discover the Dissolution Local History Project

Language selector

Don't have an account? Create an account today and support the 9/11 Memorial & Museum.

Log in with Google , Facebook or Twitter .

- Create new account

- Forgot your password?

- Oral Histories

The 9/11 Memorial Museum’s oral history collection documents the history of 9/11 through recorded interviews with responders, survivors, 9/11 family members, and others deeply affected by the attacks at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and near Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

Stories of those killed aboard the hijacked aircraft and those killed in the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center are also reflected in the collection. The edited segments below are drawn from a collection of more than 1,000 recorded interviews. The Museum continues to collect and record oral histories.

Ester DiNardo, Family Member

On September 11, 2001, Ester DiNardo lost her daughter, Marisa. Ester remembers how on her last night, Marisa brought her to Windows on the World on the top of the World Trade Center to celebrate Ester's birthday.

Oral History Transcript: Ester DiNardo

Ester DiNardo – Mother of Marisa DiNardo

Adrienne Walsh, First Responder

Off duty on the morning of 9/11, firefighter Adrienne Walsh responded to the World Trade Center with the second wave of firefighters to leave FDNY Ladder Company 20 on Lafayette Street in Soho. In this interview, Lt. Walsh recalls the fall of the North Tower.

Oral History Transcript: Adrienne Walsh

Adrienne Walsh – New York City Fire Department

Adrienne Walsh – New York City Fire Department

Robert Gray, First Responder

An expert in rescuing survivors in collapsed buildings and other high-risk situations, Arlington County Virginia Captain Robert Gray led the department’s Technical Rescue Team in its search for survivors and the recovery of victims at the Pentagon. In this interview, Gray, who was later promoted to battalion chief, describes working the 12-hour night shift at the Pentagon.

Oral Transcript History: Robert Gray

Chief Robert Gray – Arlington Country Fire Department

Frank Razzano, Survivor

A guest at the Marriott Hotel at 3 World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, Washington, D.C.–based attorney Frank Razzano was roused from sleep by a series of loud bangs. Confident that the FDNY would handle the situation, and unaware that a hijacked airplane had struck the North Tower, Razzano delayed his departure until after the collapse of the South Tower. In this segment, Razzano describes his evacuation experience.

Oral History Transcript: Frank Razzano

Frank Razzano – Survivor

Frank Razzano – Survivor

Dianne DeFontes, Survivor

The first person to arrive at her job in a law firm on the 89th floor of the North Tower, Dianne DeFontes felt the impact of hijacked Flight 11 strike the building a few floors above her desk. Within a short while, Frank De Martini , a long-time employee of the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, found DeFontes and a group of people from a nearby office and ushered them into a stairwell, where he and a coworker, Pablo Ortiz , had broken through a jammed door. In this part of her oral history, DeFontes recalls her evacuation and the vital assistance provided by De Martini and Ortiz, who lost their lives helping others that day.

Oral History Transcript: Dianne DeFontes

Dianne DeFontes – Survivor

Dianne DeFontes – Survivor

Bruno Dellinger, Survivor

From an office on the 47th floor of the North Tower, Bruno Dellinger owned and managed a small company providing art consultation services and developing cultural and commercial ties between New York and various regions in his home country of France. In an oral history recorded with the Museum, Dellinger recalls the first stages of his journey to safety, describing fellow survivors making way for injured civilians in the stairwell and the collapse of the South Tower moments after he arrived at street level.

Oral History Transcript: Bruno Dellinger

Bruno Dellinger – Survivor

Bruno Dellinger – Survivor

Arturo Ressi, World Trade Center Engineer

As a young engineer, Arturo Ressi oversaw construction of the World Trade Center slurry wall, built to prevent the Hudson River from leaking into the lowest levels of the Twin Towers. Ressi was shocked by the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11, yet also gratified to learn that the wall remained intact. In an oral history recorded for the Museum a few years before his death, Ressi said he felt that the slurry wall “wanted to stay up.” He also noted his concern that had the wall been breached, the loss of life would have grown exponentially worse. Ressi also described the strength of the 450-million-year-old Manhattan schist bedrock that makes the soaring skyline of New York City possible.

Oral History Transcript: Arturo Ressi

Arturo Ressi – World Trade Center Engineer

Arturo Ressi – World Trade Center Engineer

Rita Calvo, Survivor

A lower Manhattan resident going to high school on the Upper West Side, Rita Calvo was in class when the students learned that the World Trade Center had been attacked. In an oral history recorded for the Museum, she recalled anxiously trying to phone her parents to see if their home had been damaged. She also described how she got home that day and her father’s efforts to maintain a sense of normalcy in the midst of unprecedented terror.

Oral History Transcript: Rita Calvo

Rita Calvo – Survivor

Harry Ong Jr., Family Member

Harry Ong Jr. remembers his sister, Betty Ong , a flight attendant aboard hijacked Flight 11. He describes his family’s reaction to learning about the event and that Betty, also called Bee, had been killed in the attack.

Oral History Transcript: Harry Ong Jr.

Harry Ong Jr. – Family Member

Carl Selinger, Former Port Authority Employee

Carl Selinger was at work for the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey at the World Trade Center when a bomb was detonated there on February 26, 1993. Having left his office to pick up some lunch, he was trapped in an elevator for hours. As conditions worsened in the enclosed space, Selinger feared for his life and wrote a letter to his family before the lights went out completely. In this segment of his oral history, Selinger shares his thoughts and feelings as he waited to be rescued.

Oral History Transcript: Carl Selinger

Carl Selinger – Former Port Authority Employee

- Exhibitions

The Museum tells the story of 9/11 through interactive technology, personal narratives, and both monumental and intimate artifacts.

- The Collection

Explore a permanent collection of 60,000 artifacts consisting of material evidence, first-person testimony, and historical records of response to February 26, 1993 and 9/11.

- Group Visits

- Museum Admission Discounts

- Health and Safety

- Visitor Guidelines

- Getting Here

- Accessibility

- Programs and Events

- Find a Name

- Outdoor Memorial Audio Guide

- 9/11 Memorial Glade

- The Survivor Tree

- Past Public Programs

- School Programs

- Lesson Plans

- Anniversary Digital Learning Experience

- Digital Learning Experience Archives

- Teacher Professional Development

- Activities at Home

- Youth and Family Tours

- Talking to Children about Terrorism

- Digital Exhibitions

- Interactive Timelines

- 9/11 Primer

- Visiting Information

- Rescue and Recovery Workers

- Witnesses and Survivors

- Service Members and Veterans

- September 11, 2001

- Remember the Sky

- February 26, 1993

- May 30, 2002

- The MEMO Blog

- Sponsor a Cobblestone

- Other Ways to Give

- Member Login

- 5K Run/Walk

- Benefit Dinner

- Summit on Security

- Corporate Membership

- The Never Forget Fund

- Visionary Network

- Give to the Collection

- Share full article

The 1619 Project and the Long Battle Over U.S. History

Fights over how we tell our national story go back more than a century — and have a great deal to teach us about our current divisions.

Credit... Illustration by Derek Brahney

Supported by

By Jake Silverstein

- Published Nov. 9, 2021 Updated Nov. 12, 2021

Listen to This Article

To hear more audio stories from publications like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android .

On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became the 1619 Project for many years. Following that January meeting, she led an editorial process that over the next six months developed the idea into a special issue of the magazine, a special section of the newspaper and a multiepisode podcast series. Next week we are publishing a book that expands on the magazine issue and represents the fullest expression of her idea to date.

This book, which is called “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story,” arrives amid a prolonged debate over the version of the project we published two years ago. That project made a bold claim, which remains the central idea of the book: that the moment in August 1619 when the first enslaved Africans arrived in the English colonies that would become the United States could, in a sense, be considered the country’s origin.

The reasoning behind this is simple: Enslavement is not marginal to the history of the United States; it is inextricable. So many of our traditions and institutions were shaped by slavery, and so many of our persistent racial inequalities stem from its enduring legacy. Identifying the start of such a vast and complex system is a somewhat symbolic act. It was not until the late 1600s that slavery became codified with new laws in various colonies that firmly established the institution’s racial basis and dehumanizing structure. But 1619 marks the earliest beginnings of what would become this system. (It also could be said to mark the earliest beginnings of what would become American democracy: In July of that year, just weeks before the White Lion arrived in Point Comfort with its human cargo, the Virginia General Assembly was called to order, the first elected legislative body in English America.)

But the argument for 1619 as our origin point goes beyond the centrality of slavery; 1619 was also the year that a heroic and generative process commenced, one by which enslaved Africans and their free descendants would profoundly alter the direction and character of the country, having an impact on everything from politics to popular culture. “Around us the history of the land has centered for thrice a hundred years,” W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1903, and it is difficult to argue against extending his point through the century to follow, one that featured a Black civil rights struggle that transformed American democracy and the birth of numerous Black art forms that have profoundly influenced global culture. The 1619 Project made the provocative case that the start of the African presence in the English North American colonies could be considered the moment of inception of the United States of America. This argument was supported by 10 works of nonfiction — an opening essay by Nikole , followed by works from the journalists Jamelle Bouie , Jeneen Interlandi , Trymaine Lee , Wesley Morris and Linda Villarosa and the scholars Matthew Desmond , Kevin M. Kruse , Khalil Gibran Muhammad and Bryan Stevenson , all focused on the enduring impacts of slavery and racism and the contributions of Black Americans to our society.

Initially, the magazine issue was greeted with an enthusiastic response unlike any we had seen before. The weekend it was available in print, Aug. 18 and 19, readers all over the country complained of having to visit multiple newsstands before they could find a copy. A week later, when The Times made tens of thousands of copies available for sale online, they sold out in hours. Copies of the issue began to appear on eBay at ridiculous markups. Portions of Nikole’s opening essay from the project, which would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary, were cited in the halls of Congress; candidates in what was then a large field of potential Democratic nominees for president referred to it on the stump and the debate stage; 1619 Project book clubs seemed to materialize overnight. All of this happened in the first month.

Criticisms of the project arrived, too, including those from the World Socialist Web Site, which published numerous articles about the project and interviewed historians with objections to its conclusions. In December, four of these historians, led by a fifth, the Princeton scholar Sean Wilentz, sent a letter that asked The Times to issue “prominent corrections” for what they claimed were the project’s “errors and distortions.” We took this letter very seriously. The criticism focused mostly on Nikole’s introductory essay and within that essay zeroed in on her argument about the role of slavery in the American Revolution: “Conveniently left out of our founding mythology,” Nikole wrote, “is the fact that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

Though we recognized that the role of slavery is a matter of ongoing debate among historians of the revolution, we did not agree that this line or the other passages in question required “prominent corrections,” as I explained in a letter of response. Ultimately, however, we issued a clarification, accompanied by a lengthy editors’ note: By saying that protecting slavery was “one of the primary reasons,” Nikole did not mean to imply that it was a primary reason for every one of the colonists, who were, after all, a geographically and culturally diverse lot with varying interests; rather, she meant that one of the primary reasons driving some of them, particularly those from the Southern colonies, was the protection of slavery from British meddling. We clarified this by adding “some of” to Nikole’s original sentence so that it read: “Conveniently left out of our founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons some of the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

We published the letter from the five historians, along with my response, a few days before Christmas. Dozens of media outlets covered the exchange, and the coverage set certain corners of social media ablaze — which fueled more stories, which led others to weigh in. The editor of The American Historical Review, the journal of the American Historical Association, the nation’s oldest professional association of historians, noted in an editor’s letter that the controversy was “all anyone asked me about at the A.H.A.’s annual meeting during the first week of January.” The debate was still raging two months later, when everyone’s world changed abruptly.

Almost immediately, present and past converged: 2020 seemed to be offering a demonstration of the 1619 Project’s themes. The racial disparities in Covid infections and deaths made painfully apparent the ongoing inequalities that the project had highlighted. Then, in May, a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, and decades of pent-up frustration erupted in what is believed to be the largest protest movement in American history. In demonstrations around the country, we saw the language and ideas of the 1619 Project on cardboard signs amid huge crowds of mostly peaceful protesters gathering in cities and small towns.

It was around this time that Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas introduced a bill called the Saving American History Act, which would “prohibit federal funds from being made available to teach the 1619 Project curriculum in elementary schools and secondary schools, and for other purposes.” Cotton, who just weeks earlier published a column in The New York Times’s Opinion section calling for federal troops to subdue demonstrations, stated that the project “threatens the integrity of the Union by denying the true principles on which it was founded.” (The “curriculum” Cotton’s legislation referred to was a set of educational materials put together not by The Times but by the Pulitzer Center , a nonprofit organization that supports global journalism and, in certain instances, helps teachers bring that work into classrooms. Since 2007, the Pulitzer Center, which has no relationship to the Pulitzer Prizes, has created lesson plans around dozens of works of journalism, including three different projects from The Times Magazine. To date, thousands of educators in all 50 states have made use of the Pulitzer Center’s educational materials based on the 1619 Project to supplement — not replace — their standard social studies and history curriculums.)

As our country has moved forward from its imperfect beginnings, our history has transformed behind us.

Cotton’s bill did not move forward, but it inspired many similar efforts, perhaps most prominently the 1776 Commission, an advisory committee formed by President Donald Trump to respond to the 1619 Project and other attempts to advance a more complicated narrative of the American past. Referring to an academic framework that seeks to locate the ways racism affects the law and other institutions, Trump said, “Critical race theory, the 1619 Project and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together.” Instead, Trump’s commission would promote “patriotic education” focused on “the legacy of 1776.” This never got very far. The committee’s members issued a report on Jan. 18, just weeks after the failed insurrection in Trump’s name at the U.S. Capitol, but it was widely criticized by historians, and one of Joe Biden’s first acts as president was to disband the 1776 Commission altogether.

This barely mattered. In the United States, the real decisions over education are left to local governments and state legislatures, and the Republican Party has been steadily gaining control of legislatures in the last decade. Today the party holds full power in 30 state houses, and as the 2021 sessions got underway, Republican lawmakers from South Carolina to Idaho proposed laws echoing the language and intent of Cotton’s bill and Trump’s commission. By the end of the summer, 27 states had introduced strikingly similar versions of a “divisive concepts” bill, which swirled together misrepresentations of critical race theory and the 1619 Project with extreme examples of the diversity training that had proliferated since the previous summer. The list of these divisive concepts, which the laws would prohibit from being discussed in classrooms, included such ideas as “one race, ethnic group or sex is inherently morally or intellectually superior to another race, ethnic group or sex” and “an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race, ethnicity or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed by other members of the same race, ethnic group or sex,” as Arizona House Bill 2898 put it. To be clear, these notions aren’t found in the 1619 Project or in any but the most fringe writings by adherents of critical race theory, but the legislation aimed at something broader. “The clear goal of these efforts is to suppress teaching and learning about the role of racism in the history of the United States,” the A.H.A. and three other associations declared in a statement in June. “But the ideal of informed citizenship necessitates an educated public.” Eventually, more than 150 professional organizations would sign this letter, including the Society of Civil War Historians, the National Education Association, the Midwestern History Association and the Organization of American Historians.

Nevertheless, by late August, the two-year anniversary of the 1619 Project, 12 states had enacted some form of these bans. In Florida, the State Board of Education voted unanimously to prohibit the teaching of the project at a meeting in June, following a brief address from Gov. Ron DeSantis, in which he explained his opposition (mischaracterizing, as was so often the case, the claim from Nikole’s essay that the original five historians seized on):

This 1619 Project that came out a couple years ago, the folks who created that said that the American Revolution was fought primarily to preserve slavery. Now, that is factually false. That is something that you can look at the historical record. You want to know why they revolted against Britain? They told us. They wrote pamphlets, they did committees of correspondence, they did a Declaration of Independence. ... I think it’s really important that when we’re doing history, when we’re doing things like civics, that it is grounded in actual fact, and I think we’ve got to have an education system that is preferring fact over narratives.

A curious feature of this argument on behalf of the historical record is how ahistorical it is. In privileging “actual fact” over “narrative,” the governor, and many others, seem to proceed from the premise that history is a fixed thing; that somehow, long ago, the nation’s historians identified the relevant set of facts about our past, and it is the job of subsequent generations to simply protect and disseminate them. This conception denies history its own history — the dynamic, contested and frankly pretty thrilling process by which an understanding of the past is formed and reformed. The study of this is known as historiography, and a knowledge of American historiography, in particular the way our historical profession evolved to take fuller account of the role of slavery and racism in our past, is critical to understanding the debates of the past two years.

The earliest attempts to record the nation’s history took the form of accounts of military campaigns, summaries of state and federal legislative activity, dispatches from the frontier and other narrowly focused reports. In the 19th century, these were replaced by a master narrative of the colonial and founding era, best exemplified by “the father of American history,” George Bancroft, in his “History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent.” Published in 10 volumes from the 1830s through the 1870s, Bancroft’s opus is generally seen as the first comprehensive history of the country, and its influence was incalculable. Bancroft’s ambition was to synthesize American history into a grand and glorious epic. He viewed the European colonists who settled the continent as acting out a divine plan and the revolution as an almost purely philosophical act, undertaken to model self-government for all the world.

The scholarly effort to revise this narrative began in the early 20th century with the work of the “Progressive historians,” most notably Charles A. Beard, who tried to show that the founders were motivated not exclusively by idealism and virtue but also by their pocketbooks. “Suppose,” Beard asked in 1913, “our fundamental law was not the product of an abstraction known as ‘the whole people,’ but of a group of economic interests which must have expected beneficial results from its adoption?” Though the Progressives’ work was influential, they were bitterly attacked for their theories, which shocked many Americans. “SCAVENGERS, HYENA-LIKE, DESECRATE THE GRAVES OF THE DEAD PATRIOTS WE REVERE,” blared one headline in an Ohio newspaper.

As the Cold War dawned, it became clear that this school could not provide the necessary inspiration for an America that envisioned itself a defender of global freedom and democracy. The Beardian approach was beaten back by the counter-Progressive or “Consensus” school, which emphasized the founders’ shared values and played down class conflict. Among Consensus historians, a keen sense of national purpose was evident, as well as an eagerness to disavow the whiff of Marxism in the progressive narrative and re-establish the founders’ idealism. In 1950, the Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison lamented that the Progressives were “robbing the people of their heroes” and “insulting their folk-memory of the great figures whom they admired.” Seven years later, one of his former students, Edmund S. Morgan, published “The Birth of the Republic, 1763-1789,” a key text of this era (described by one reviewer at the time as having the “brilliant hue of the era of Eisenhower prosperity”). Morgan stressed the revolution as a “search for principles” that led to a nation committed to liberty and equality.

By the 1960s, the pendulum was ready to swing the other way. A group of scholars identified variously as Neo-Progressive historians, New Left historians or social historians challenged the old paradigm, turning their focus to the lives of common people in colonial society and U.S. history more broadly. Earlier generations primarily studied elites, who left a copious archive of written material. Because the subjects of the new history — laborers, seamen, enslaved people, women, Indigenous people — produced relatively little writing of their own, many of these scholars turned instead to large data sets like tax lists, real estate inventories and other public records to illuminate the lives of what were sometimes called the “inarticulate masses.” This novel approach set aside “the central assumption of traditional history, what might be called the doctrine of implicit importance,” wrote the historian Jack P. Greene in a 1975 article in The Times. “From the perspective supplied by the new history, it has become clear that the experience of women, children, servants, slaves and other neglected groups are quite as integral to a comprehensive understanding of the past as that of lawyers, lords and ministers of state.”

An explosion of new research resulted, transforming the field of American history. One of the most significant developments was an increased attention to Black history and the role of slavery. For more than a century, a profession dominated by white men had mostly consigned these subjects to the sidelines. Bancroft had seen slavery as problematic — “an anomaly in a democratic country” — but mostly because it empowered a Southern planter elite he considered corrupt, lazy and aristocratic. Beard and the other Progressives hadn’t focused much on slavery, either. Until the 1950s, the institution was treated in canonical works of American history as an aberration best addressed minimally if at all. When it was taken up for close study, as in Ulrich B. Phillips’s 1918 book, “American Negro Slavery,” it was seen as an inefficient enterprise sustained by benevolent masters to whom enslaved people felt mostly gratitude. That began to change in the 1950s and 1960s, as works by Herbert Aptheker, Stanley Elkins, Philip S. Foner, John Hope Franklin, Eugene D. Genovese, Benjamin Quarles, Kenneth M. Stampp, C. Vann Woodward and many others transformed the mainstream view of slavery.

Among the converts was Edmund Morgan himself, who noted in a 1972 address that “American historians interested in tracing the rise of liberty, democracy and the common man have been challenged in the past two decades by other historians, interested in tracing the history of oppression, exploitation and racism. The challenge has been salutary, because it has made us examine more directly than historians have hitherto been willing to do the role of slavery in our early history. Colonial historians, in particular, when writing about the origin and development of American institutions, have found it possible until recently to deal with slavery as an exception to everything they had to say. I am speaking about myself but also about most of my generation.”

To be more precise, Morgan might have said that white historians had “found it possible” to hold slavery and the creation of American democracy entirely apart. Black historians, working outside the mainstream for a hundred years, tended to see the matter more clearly. For during this whole evolution in American history, from Bancroft through the 1960s, there was another scholarly tradition unfolding, one that only rarely gained entry into white-dominated academic spaces.

It began, like all historiographies, with the work of non-historians, the sermons, poems, speeches and memoirs by Black writers of the revolutionary period and beyond. The antebellum historians William C. Nell and William Wells Brown wrote scholarly accounts of Black participation in the American Revolution. But the first work by a Black author generally considered part of what was then the emerging field of professional history was George Washington Williams’s “History of the Negro Race in America From 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers and as Citizens,” published in 1882.

Williams was an innovator. He had to be. In writing his landmark book, he pioneered several research methodologies that would later re-emerge among the social historians — the use of oral history, the aggregation of statistical data, even the use of newspapers as primary sources. His view of the centrality of slavery was also far ahead of its time:

No event in the history of North America has carried with it to its last analysis such terrible forces. It touched the brightest features of social life, and they faded under the contact of its poisonous breath. It affected legislation, local and national; it made and destroyed statesmen; it prostrated and bullied honest public sentiment; it strangled the voice of the press, and awed the pulpit into silent acquiescence; it organized the judiciary of States, and wrote decisions for judges; it gave States their political being, and afterwards dragged them by the fore-hair through the stormy sea of civil war; laid the parricidal fingers of Treason against the fair throat of Liberty, — and through all time to come no event will be more sincerely deplored than the introduction of slavery into the colony of Virginia during the last days of the month of August in the year 1619!

Like so many Black historians, Williams was writing against the grain, not only in his insistence on the influence of slavery in shaping American institutions but in something even more basic: his assumption of Black humanity. This challenge he faced is made clear from the first chapter of Volume I: “It is proposed, in the first place, to call the attention to the absurd charge that the Negro does not belong to the human family.” In a nation backtracking on the promise of Reconstruction, this was an inherently political statement. Just one year after “History of the Negro Race” was published, the U.S. Supreme Court would invalidate as unconstitutional the protections of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which barred racial discrimination in public accommodations and transportation. A country that denied Black people the rights of citizens could not also see them as significant historical actors.

“History is a science, a social science, but it’s also politics,” the historian Martha S. Jones, who contributed a chapter in the new 1619 book, told me. “And Black historians have always known that. They always know the stakes. In a world that would brand Africans as people without a history, Williams understood the political consequence of the assertion that Black people have history and might even be driving it.”

We can see evidence of this in the decades of Jim Crow that followed Reconstruction, when Black people were not only prevented from voting and denied access to a wide array of public accommodations but also, for the most part, kept out of the mainstream history profession. Nevertheless, a rich Black scholarly tradition continued to unfold in publications like The Journal of Negro History, founded by Carter G. Woodson in 1916, and in the work of scholars like W.E.B. Du Bois, Helen G. Edmonds, Lorenzo Greene, Luther P. Jackson, Rayford Logan, Benjamin Quarles and Charles H. Wesley. Quarles’s book “The Negro in the American Revolution,” published in 1961, was an important part of that decade’s historiographical reassessments. It was the first to thoroughly explore an often-overlooked feature of that war: that substantially more Black people were drawn to the British side than the Patriot cause, believing this the better path to freedom. Quarles’s work posed profound questions about the traditional narrative of the founding era. While acknowledging that for some white people the ideals of the Revolution had “exposed the inconsistencies” of chattel slavery in a nation founded on equality, he also observed a deeply uncomfortable fact: “They were far outnumbered by those who detected no ideological inconsistency. These white Americans, not considering themselves counterrevolutionary, would never have dreamed of repudiating the theory of natural rights. Instead they skirted the dilemma by maintaining that blacks were an outgroup rather than members of the body politic.”

The story told by Quarles and his predecessors amounted to a counternarrative of American history, one in which, contrary to what many white historians had argued, slavery was essential to the development of the colonies; Black soldiers played an important role on both sides of the American Revolution and in the Union victory in the Civil War; and Reconstruction was an idealistic attempt to make the United States an interracial democracy, not a failed experiment that served only to demonstrate the folly of giving Black people the right to vote.

It is no coincidence that this counternarrative began to break through in the 1960s, at the same time as Black Americans finally won that right, one that the 15th Amendment to the Constitution sought to guarantee in 1870 (for men), only to see it abrogated in all the Southern states by the turn of the century. As Bancroft demonstrated and Jones noted, history is not simply an academic exercise — it is inherently political. Those without political standing in the present are generally discounted as historical actors in the past. In the 1960s, after hundreds of years, American democracy had been made to include Black people; now American history would, too.