An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Bentham Open Access

Internet Addiction: A Brief Summary of Research and Practice

Hilarie cash.

a reSTART Internet Addiction Recovery Program, Fall City, WA 98024

Cosette D Rae

Ann h steel, alexander winkler.

b University of Marburg, Department for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Gutenbergstraße 18, 35032 Marburg, Germany

Problematic computer use is a growing social issue which is being debated worldwide. Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) ruins lives by causing neurological complications, psychological disturbances, and social problems. Surveys in the United States and Europe have indicated alarming prevalence rates between 1.5 and 8.2% [1]. There are several reviews addressing the definition, classification, assessment, epidemiology, and co-morbidity of IAD [2-5], and some reviews [6-8] addressing the treatment of IAD. The aim of this paper is to give a preferably brief overview of research on IAD and theoretical considerations from a practical perspective based on years of daily work with clients suffering from Internet addiction. Furthermore, with this paper we intend to bring in practical experience in the debate about the eventual inclusion of IAD in the next version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

INTRODUCTION

The idea that problematic computer use meets criteria for an addiction, and therefore should be included in the next iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) , 4 th ed. Text Revision [ 9 ] was first proposed by Kimberly Young, PhD in her seminal 1996 paper [ 10 ]. Since that time IAD has been extensively studied and is indeed, currently under consideration for inclusion in the DSM-V [ 11 ]. Meanwhile, both China and South Korea have identified Internet addiction as a significant public health threat and both countries support education, research and treatment [ 12 ]. In the United States, despite a growing body of research, and treatment for the disorder available in out-patient and in-patient settings, there has been no formal governmental response to the issue of Internet addiction. While the debate goes on about whether or not the DSM-V should designate Internet addiction a mental disorder [ 12 - 14 ] people currently suffering from Internet addiction are seeking treatment. Because of our experience we support the development of uniform diagnostic criteria and the inclusion of IAD in the DSM-V [ 11 ] in order to advance public education, diagnosis and treatment of this important disorder.

CLASSIFICATION

There is ongoing debate about how best to classify the behavior which is characterized by many hours spent in non-work technology-related computer/Internet/video game activities [ 15 ]. It is accompanied by changes in mood, preoccupation with the Internet and digital media, the inability to control the amount of time spent interfacing with digital technology, the need for more time or a new game to achieve a desired mood, withdrawal symptoms when not engaged, and a continuation of the behavior despite family conflict, a diminishing social life and adverse work or academic consequences [ 2 , 16 , 17 ]. Some researchers and mental health practitioners see excessive Internet use as a symptom of another disorder such as anxiety or depression rather than a separate entity [e.g. 18]. Internet addiction could be considered an Impulse control disorder (not otherwise specified). Yet there is a growing consensus that this constellation of symptoms is an addiction [e.g. 19]. The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recently released a new definition of addiction as a chronic brain disorder, officially proposing for the first time that addiction is not limited to substance use [ 20 ]. All addictions, whether chemical or behavioral, share certain characteristics including salience, compulsive use (loss of control), mood modification and the alleviation of distress, tolerance and withdrawal, and the continuation despite negative consequences.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR IAD

The first serious proposal for diagnostic criteria was advanced in 1996 by Dr. Young, modifying the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling [ 10 ]. Since then variations in both name and criteria have been put forward to capture the problem, which is now most popularly known as Internet Addiction Disorder. Problematic Internet Use (PIU) [ 21 ], computer addiction, Internet dependence [ 22 ], compulsive Internet use, pathological Internet use [ 23 ], and many other labels can be found in the literature. Likewise a variety of often overlapping criteria have been proposed and studied, some of which have been validated. However, empirical studies provide an inconsistent set of criteria to define Internet addiction [ 24 ]. For an overview see Byun et al . [ 25 ].

Beard [ 2 ] recommends that the following five diagnostic criteria are required for a diagnosis of Internet addiction: (1) Is preoccupied with the Internet (thinks about previous online activity or anticipate next online session); (2) Needs to use the Internet with increased amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction; (3) Has made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop Internet use; (4) Is restless, moody, depressed, or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop Internet use; (5) Has stayed online longer than originally intended. Additionally, at least one of the following must be present: (6) Has jeopardized or risked the loss of a significant relationship, job, educational or career opportunity because of the Internet; (7) Has lied to family members, therapist, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the Internet; (8) Uses the Internet as a way of escaping from problems or of relieving a dysphoric mood (e.g., feelings of helplessness, guilt, anxiety, depression) [ 2 ].

There has been also been a variety of assessment tools used in evaluation. Young’s Internet Addiction Test [ 16 ], the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ) developed by Demetrovics, Szeredi, and Pozsa [ 26 ] and the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) [ 27 ] are all examples of instruments to assess for this disorder.

The considerable variance of the prevalence rates reported for IAD (between 0.3% and 38%) [ 28 ] may be attributable to the fact that diagnostic criteria and assessment questionnaires used for diagnosis vary between countries and studies often use highly selective samples of online surveys [ 7 ]. In their review Weinstein and Lejoyeux [ 1 ] report that surveys in the United States and Europe have indicated prevalence rates varying between 1.5% and 8.2%. Other reports place the rates between 6% and 18.5% [ 29 ].

“Some obvious differences with respect to the methodologies, cultural factors, outcomes and assessment tools forming the basis for these prevalence rates notwithstanding, the rates we encountered were generally high and sometimes alarming.” [ 24 ]

There are different models available for the development and maintenance of IAD like the cognitive-behavioral model of problematic Internet use [ 21 ], the anonymity, convenience and escape (ACE) model [ 30 ], the access, affordability, anonymity (Triple-A) engine [ 31 ], a phases model of pathological Internet use by Grohol [ 32 ], and a comprehensive model of the development and maintenance of Internet addiction by Winkler & Dörsing [ 24 ], which takes into account socio-cultural factors ( e.g. , demographic factors, access to and acceptance of the Internet), biological vulnerabilities ( e.g. , genetic factors, abnormalities in neurochemical processes), psychological predispositions ( e.g. , personality characteristics, negative affects), and specific attributes of the Internet to explain “excessive engagement in Internet activities” [ 24 ].

NEUROBIOLOGICAL VULNERABILITIES

It is known that addictions activate a combination of sites in the brain associated with pleasure, known together as the “reward center” or “pleasure pathway” of the brain [ 33 , 34 ]. When activated, dopamine release is increased, along with opiates and other neurochemicals. Over time, the associated receptors may be affected, producing tolerance or the need for increasing stimulation of the reward center to produce a “high” and the subsequent characteristic behavior patterns needed to avoid withdrawal. Internet use may also lead specifically to dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens [ 35 , 36 ], one of the reward structures of the brain specifically involved in other addictions [ 20 ]. An example of the rewarding nature of digital technology use may be captured in the following statement by a 21 year-old male in treatment for IAD:

“I feel technology has brought so much joy into my life. No other activity relaxes me or stimulates me like technology. However, when depression hits, I tend to use technology as a way of retreating and isolating.”

REINFORCEMENT/REWARD

What is so rewarding about Internet and video game use that it could become an addiction? The theory is that digital technology users experience multiple layers of reward when they use various computer applications. The Internet functions on a variable ratio reinforcement schedule (VRRS), as does gambling [ 29 ]. Whatever the application (general surfing, pornography, chat rooms, message boards, social networking sites, video games, email, texting, cloud applications and games, etc.), these activities support unpredictable and variable reward structures. The reward experienced is intensified when combined with mood enhancing/stimulating content. Examples of this would be pornography (sexual stimulation), video games (e.g. various social rewards, identification with a hero, immersive graphics), dating sites (romantic fantasy), online poker (financial) and special interest chat rooms or message boards (sense of belonging) [ 29 , 37 ].

BIOLOGICAL PREDISPOSITION

There is increasing evidence that there can be a genetic predisposition to addictive behaviors [ 38 , 39 ]. The theory is that individuals with this predisposition do not have an adequate number of dopamine receptors or have an insufficient amount of serotonin/dopamine [ 2 ], thereby having difficulty experiencing normal levels of pleasure in activities that most people would find rewarding. To increase pleasure, these individuals are more likely to seek greater than average engagement in behaviors that stimulate an increase in dopamine, effectively giving them more reward but placing them at higher risk for addiction.

MENTAL HEALTH VULNERABILITIES

Many researchers and clinicians have noted that a variety of mental disorders co-occur with IAD. There is debate about which came first, the addiction or the co-occurring disorder [ 18 , 40 ]. The study by Dong et al . [ 40 ] had at least the potential to clarify this question, reporting that higher scores for depression, anxiety, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, and psychoticism were consequences of IAD. But due to the limitations of the study further research is necessary.

THE TREATMENT OF INTERNET ADDICTION

There is a general consensus that total abstinence from the Internet should not be the goal of the interventions and that instead, an abstinence from problematic applications and a controlled and balanced Internet usage should be achieved [ 6 ]. The following paragraphs illustrate the various treatment options for IAD that exist today. Unless studies examining the efficacy of the illustrated treatments are not available, findings on the efficacy of the presented treatments are also provided. Unfortunately, most of the treatment studies were of low methodological quality and used an intra-group design.

The general lack of treatment studies notwithstanding, there are treatment guidelines reported by clinicians working in the field of IAD. In her book “Internet Addiction: Symptoms, Evaluation, and Treatment”, Young [ 41 ] offers some treatment strategies which are already known from the cognitive-behavioral approach: (a) practice opposite time of Internet use (discover patient’s patterns of Internet use and disrupt these patterns by suggesting new schedules), (b) use external stoppers (real events or activities prompting the patient to log off), (c) set goals (with regard to the amount of time), (d) abstain from a particular application (that the client is unable to control), (e) use reminder cards (cues that remind the patient of the costs of IAD and benefits of breaking it), (f) develop a personal inventory (shows all the activities that the patient used to engage in or can’t find the time due to IAD), (g) enter a support group (compensates for a lack of social support), and (h) engage in family therapy (addresses relational problems in the family) [ 41 ]. Unfortunately, clinical evidence for the efficacy of these strategies is not mentioned.

Non-psychological Approaches

Some authors examine pharmacological interventions for IAD, perhaps due to the fact that clinicians use psychopharmacology to treat IAD despite the lack of treatment studies addressing the efficacy of pharmacological treatments. In particular, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been used because of the co-morbid psychiatric symptoms of IAD (e.g. depression and anxiety) for which SSRIs have been found to be effective [ 42 - 46 ]. Escitalopram (a SSRI) was used by Dell’Osso et al . [ 47 ] to treat 14 subjects with impulsive-compulsive Internet usage disorder. Internet usage decreased significantly from a mean of 36.8 hours/week to a baseline of 16.5 hours/week. In another study Han, Hwang, and Renshaw [ 48 ] used bupropion (a non-tricyclic antidepressant) and found a decrease of craving for Internet video game play, total game play time, and cue-induced brain activity in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex after a six week period of bupropion sustained release treatment. Methylphenidate (a psycho stimulant drug) was used by Han et al . [ 49 ] to treat 62 Internet video game-playing children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. After eight weeks of treatment, the YIAS-K scores and Internet usage times were significantly reduced and the authors cautiously suggest that methylphenidate might be evaluated as a potential treatment of IAD. According to a study by Shapira et al . [ 50 ], mood stabilizers might also improve the symptoms of IAD. In addition to these studies, there are some case reports of patients treated with escitalopram [ 45 ], citalopram (SSRI)- quetiapine (antipsychotic) combination [ 43 ] and naltrexone (an opioid receptor antagonist) [ 51 ].

A few authors mentioned that physical exercise could compensate the decrease of the dopamine level due to decreased online usage [ 52 ]. In addition, sports exercise prescriptions used in the course of cognitive behavioral group therapy may enhance the effect of the intervention for IAD [ 53 ].

Psychological Approaches

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a client-centered yet directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving client ambivalence [ 54 ]. It was developed to help individuals give up addictive behaviors and learn new behavioral skills, using techniques such as open-ended questions, reflective listening, affirmation, and summarization to help individuals express their concerns about change [ 55 ]. Unfortunately, there are currently no studies addressing the efficacy of MI in treating IAD, but MI seems to be moderately effective in the areas of alcohol, drug addiction, and diet/exercise problems [ 56 ].

Peukert et al . [ 7 ] suggest that interventions with family members or other relatives like “Community Reinforcement and Family Training” [ 57 ] could be useful in enhancing the motivation of an addict to cut back on Internet use, although the reviewers remark that control studies with relatives do not exist to date.

Reality therapy (RT) is supposed to encourage individuals to choose to improve their lives by committing to change their behavior. It includes sessions to show clients that addiction is a choice and to give them training in time management; it also introduces alternative activities to the problematic behavior [ 58 ]. According to Kim [ 58 ], RT is a core addiction recovery tool that offers a wide variety of uses as a treatment for addictive disorders such as drugs, sex, food, and works as well for the Internet. In his RT group counseling program treatment study, Kim [ 59 ] found that the treatment program effectively reduced addiction level and improved self-esteem of 25 Internet-addicted university students in Korea.

Twohig and Crosby [ 60 ] used an Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) protocol including several exercises adjusted to better fit the issues with which the sample struggles to treat six adult males suffering from problematic Internet pornography viewing. The treatment resulted in an 85% reduction in viewing at post-treatment with results being maintained at the three month follow-up (83% reduction in viewing pornography).

Widyanto and Griffith [ 8 ] report that most of the treatments employed so far had utilized a cognitive-behavioral approach. The case for using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is justified due to the good results in the treatment of other behavioral addictions/impulse-control disorders, such as pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating-disorders [ 61 ]. Wölfling [ 5 ] described a predominantly behavioral group treatment including identification of sustaining conditions, establishing of intrinsic motivation to reduce the amount of time being online, learning alternative behaviors, engagement in new social real-life contacts, psycho-education and exposure therapy, but unfortunately clinical evidence for the efficacy of these strategies is not mentioned. In her study, Young [ 62 ] used CBT to treat 114 clients suffering from IAD and found that participants were better able to manage their presenting problems post-treatment, showing improved motivation to stop abusing the Internet, improved ability to control their computer use, improved ability to function in offline relationships, improved ability to abstain from sexually explicit online material, improved ability to engage in offline activities, and improved ability to achieve sobriety from problematic applications. Cao, Su and Gao [ 63 ] investigated the effect of group CBT on 29 middle school students with IAD and found that IAD scores of the experimental group were lower than of the control group after treatment. The authors also reported improvement in psychological function. Thirty-eight adolescents with IAD were treated with CBT designed particularly for addicted adolescents by Li and Dai [ 64 ]. They found that CBT has good effects on the adolescents with IAD (CIAS scores in the therapy group were significant lower than that in the control group). In the experimental group the scores of depression, anxiety, compulsiveness, self-blame, illusion, and retreat were significantly decreased after treatment. Zhu, Jin, and Zhong [ 65 ] compared CBT and electro acupuncture (EA) plus CBT assigning forty-seven patients with IAD to one of the two groups respectively. The authors found that CBT alone or combined with EA can significantly reduce the score of IAD and anxiety on a self-rating scale and improve self-conscious health status in patients with IAD, but the effect obtained by the combined therapy was better.

Multimodal Treatments

A multimodal treatment approach is characterized by the implementation of several different types of treatment in some cases even from different disciplines such as pharmacology, psychotherapy and family counseling simultaneously or sequentially. Orzack and Orzack [ 66 ] mentioned that treatments for IAD need to be multidisciplinary including CBT, psychotropic medication, family therapy, and case managers, because of the complexity of these patients’ problems.

In their treatment study, Du, Jiang, and Vance [ 67 ] found that multimodal school-based group CBT (including parent training, teacher education, and group CBT) was effective for adolescents with IAD (n = 23), particularly in improving emotional state and regulation ability, behavioral and self-management style. The effect of another multimodal intervention consisting of solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), family therapy, and CT was investigated among 52 adolescents with IAD in China. After three months of treatment, the scores on an IAD scale (IAD-DQ), the scores on the SCL-90, and the amount of time spent online decreased significantly [ 68 ]. Orzack et al . [ 69 ] used a psychoeducational program, which combines psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral theoretical perspectives, using a combination of Readiness to Change (RtC), CBT and MI interventions to treat a group of 35 men involved in problematic Internet-enabled sexual behavior (IESB). In this group treatment, the quality of life increased and the level of depressive symptoms decreased after 16 (weekly) treatment sessions, but the level of problematic Internet use failed to decrease significantly [ 69 ]. Internet addiction related symptom scores significantly decreased after a group of 23 middle school students with IAD were treated with Behavioral Therapy (BT) or CT, detoxification treatment, psychosocial rehabilitation, personality modeling and parent training [ 70 ]. Therefore, the authors concluded that psychotherapy, in particular CT and BT were effective in treating middle school students with IAD. Shek, Tang, and Lo [ 71 ] described a multi-level counseling program designed for young people with IAD based on the responses of 59 clients. Findings of this study suggest this multi-level counseling program (including counseling, MI, family perspective, case work and group work) is promising to help young people with IAD. Internet addiction symptom scores significantly decreased, but the program failed to increase psychological well-being significantly. A six-week group counseling program (including CBT, social competence training, training of self-control strategies and training of communication skills) was shown to be effective on 24 Internet-addicted college students in China [ 72 ]. The authors reported that the adapted CIAS-R scores of the experimental group were significantly lower than those of the control group post-treatment.

The reSTART Program

The authors of this article are currently, or have been, affiliated with the reSTART: Internet Addiction Recovery Program [ 73 ] in Fall City, Washington. The reSTART program is an inpatient Internet addiction recovery program which integrates technology detoxification (no technology for 45 to 90 days), drug and alcohol treatment, 12 step work, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), experiential adventure based therapy, Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT), brain enhancing interventions, animal assisted therapy, motivational interviewing (MI), mindfulness based relapse prevention (MBRP), Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR), interpersonal group psychotherapy, individual psychotherapy, individualized treatments for co-occurring disorders, psycho- educational groups (life visioning, addiction education, communication and assertiveness training, social skills, life skills, Life balance plan), aftercare treatments (monitoring of technology use, ongoing psychotherapy and group work), and continuing care (outpatient treatment) in an individualized, holistic approach.

The first results from an ongoing OQ45.2 [ 74 ] study (a self-reported measurement of subjective discomfort, interpersonal relationships and social role performance assessed on a weekly basis) of the short-term impact on 19 adults who complete the 45+ days program showed an improved score after treatment. Seventy-four percent of participants showed significant clinical improvement, 21% of participants showed no reliable change, and 5% deteriorated. The results have to be regarded as preliminary due to the small study sample, the self-report measurement and the lack of a control group. Despite these limitations, there is evidence that the program is responsible for most of the improvements demonstrated.

As can be seen from this brief review, the field of Internet addiction is advancing rapidly even without its official recognition as a separate and distinct behavioral addiction and with continuing disagreement over diagnostic criteria. The ongoing debate whether IAD should be classified as an (behavioral) addiction, an impulse-control disorder or even an obsessive compulsive disorder cannot be satisfactorily resolved in this paper. But the symptoms we observed in clinical practice show a great deal of overlap with the symptoms commonly associated with (behavioral) addictions. Also it remains unclear to this day whether the underlying mechanisms responsible for the addictive behavior are the same in different types of IAD (e.g., online sexual addiction, online gaming, and excessive surfing). From our practical perspective the different shapes of IAD fit in one category, due to various Internet specific commonalities (e.g., anonymity, riskless interaction), commonalities in the underlying behavior (e.g., avoidance, fear, pleasure, entertainment) and overlapping symptoms (e.g., the increased amount of time spent online, preoccupation and other signs of addiction). Nevertheless more research has to be done to substantiate our clinical impression.

Despite several methodological limitations, the strength of this work in comparison to other reviews in the international body of literature addressing the definition, classification, assessment, epidemiology, and co-morbidity of IAD [ 2 - 5 ], and to reviews [ 6 - 8 ] addressing the treatment of IAD, is that it connects theoretical considerations with the clinical practice of interdisciplinary mental health experts working for years in the field of Internet addiction. Furthermore, the current work gives a good overview of the current state of research in the field of internet addiction treatment. Despite the limitations stated above this work gives a brief overview of the current state of research on IAD from a practical perspective and can therefore be seen as an important and helpful paper for further research as well as for clinical practice in particular.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Internet Addiction: A Brief Summary of Research and Practice

Affiliation.

- 1 reSTART Internet Addiction Recovery Program, Fall City, WA 98024.

- PMID: 23125561

- PMCID: PMC3480687

- DOI: 10.2174/157340012803520513

Problematic computer use is a growing social issue which is being debated worldwide. Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) ruins lives by causing neurological complications, psychological disturbances, and social problems. Surveys in the United States and Europe have indicated alarming prevalence rates between 1.5 and 8.2% [1]. There are several reviews addressing the definition, classification, assessment, epidemiology, and co-morbidity of IAD [2-5], and some reviews [6-8] addressing the treatment of IAD. The aim of this paper is to give a preferably brief overview of research on IAD and theoretical considerations from a practical perspective based on years of daily work with clients suffering from Internet addiction. Furthermore, with this paper we intend to bring in practical experience in the debate about the eventual inclusion of IAD in the next version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 06 January 2021

Prevalence and associated factors of internet addiction among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia: a community university-based cross-sectional study

- Yosef Zenebe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0138-6588 1 ,

- Kunuya Kunno 1 ,

- Meseret Mekonnen 1 ,

- Ajebush Bewuket 1 ,

- Mengesha Birkie 1 ,

- Mogesie Necho 1 ,

- Muhammed Seid 1 ,

- Million Tsegaw 1 &

- Baye Akele 2

BMC Psychology volume 9 , Article number: 4 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

39 Citations

280 Altmetric

Metrics details

Internet addiction is a common problem in university students and negatively affects cognitive functioning, leads to poor academic performance and engagement in hazardous activities, and may lead to anxiety and stress. Behavioral addictions operate on a modified principle of the classic addiction model. The problem is not well investigated in Ethiopia. So the present study aimed to assess the prevalence of internet addiction and associated factors among university students in Ethiopia.

Main objective of this study was to assess the prevalence and associated factors of internet addiction among University Students in Ethiopia.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among Wollo University students from April 10 to May 10, 2019. A total of 603 students were participated in the study using a structured questionnaire. A multistage cluster sampling technique was used to recruit study participants. A binary logistic regression method was used to explore associated factors for internet addiction and variables with a p value < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis were fitted to the multi-variable logistic regression analysis. The strength of association between internet addiction and associated factors was assessed with odds ratio, 95% CI and p value < 0.05 in the final model was considered significant.

The prevalence of internet addiction (IA) among the current internet users was 85% (n = 466). Spending more time on the internet (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 10.13, 95% CI 1.33–77.00)), having mental distress (AOR = 2.69, 95% CI 1.02–7.06), playing online games (AOR = 2.40, 95% CI 1.38–4.18), current khat chewing (AOR = 3.34, 95% CI 1.14–9.83) and current alcohol use (AOR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.09–4.92) were associated with internet addiction.

Conclusions

The current study documents a high prevalence of internet addiction among Wollo University students. Factors associated with internet addiction were spending more time, having mental distress, playing online games, current khat chewing, and current alcohol use. As internet addiction becomes an evident public health problem, carrying out public awareness campaigns may be a fruitful strategy to decrease its prevalence and effect. Besides to this, a collaborative work among stakeholders is important to develop other trendy, adaptive, and sustainable countermeasures.

Peer Review reports

Globally, more than three billion people use the internet daily with young people being the most common users [ 1 ]. In the field of medicine and healthcare, it helps in the practice of evidence-based medicine, research and learning, access to medical and online databases, handling patients in remote areas, and academic and recreational purposes [ 2 , 3 ].

In terms of classical psychology and psychiatry, IA is a relatively new phenomenon. The literature uses interchangeable references such as “compulsive Internet use”, “problematic Internet use”, “pathological Internet use”, and “Internet addiction”. The Psychologist Mark Griffiths, one of the widely recognized authorities in the sphere of addictive behavior, is the author of the most frequently quoted definition: “Internet addiction is a non-chemical behavioral addiction, which involves human–machine (computer-Internet) interaction” [ 4 , 5 ]. Internet addiction is a behavioural problem that has gained increasing scientific recognition in the last decade, with some researchers claiming it is a "21st Century epidemic"[ 6 ]. The psychopathologic symptoms of internet addiction includes Salience(the respondent most likely feels preoccupied with the Internet, hides the behaviour from others, and may display a loss of interest in other activities and/or relationships only to prefer more solitary time online), Excessive Use (the respondent engages in excessive online behaviour and compulsive usage, and is intermittently unable to control time online that he or she hides from others), Neglect Work (Job or school performance and productivity are most likely compromised due to the amount of time spent online), Anticipation(the respondent most likely thinks about being online when not at the computer and feels compelled to use the Internet when offline), Lack of Control(the respondent has trouble managing his or her online time, frequently stays online longer than intended, and others may complain about the amount of time he or she spends online) and Neglect Social Life (the respondent frequently forms new relationships with fellow online users and uses the Internet to establish social connections that may be missing in his or her life) [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Events during the adolescence period greatly influence a person's development and can determine their attitudes and behavior in later life [ 11 ]. The teenagers are often in conflict with authority and cultural and moral norms of society, certain developmental effects can trigger a series of defense mechanisms [ 12 ]. During adolescence, there is an increased risk of emotional crises, often accompanied by mood changes and periods of anxiety and depressive behavior, which some adolescents attempt to fight through withdrawal, avoidance of any extensive social contact, aggressive reactions, and addictive behaviour [ 13 , 14 ]. Adolescents are exceptionally vulnerable and receptive during this period and can become drawn to the Internet as a form of release. Over time, this can lead to addiction [ 15 ].

Relaxed access and social networking are two of the several aspects of the Internet development of addictive behaviour [ 16 ]. Internet addiction is a newly emerged behavioral problem of adults which was reported after problem behavior theory was proposed [ 17 ]. Behavioral addictions operate on a modified principle of the classic addiction model [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Others have reported, that there is a tendency for individuals to be multiply ''addicted'' and to have overlapping addictions between common substances such as alcohol and cigarettes and ''addictions'' to activities such as internet use, gambling, exercising, and television [ 21 ]. A key factor to both models of substance and behavioral addictions is the concept of psychological dependence, in which no physiological exchange, such as ingestion of a substance, occurs [ 18 , 22 ]. Internet addiction in puberty and young adults can negatively impact life satisfaction and engagement [ 23 ], which may negatively affect cognitive functioning [ 24 ], lead to poor academic performance [ 25 , 26 ], and engagement in hazardous activities [ 27 ]. Internet addiction is also related to depression, somatization, and obsessive–compulsive disorder [ 28 ]. It has been found that paranoid ideation, hostility, anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, and obsessive–compulsive average scores are higher in people with high Internet Addiction scores than those without Internet addiction [ 29 , 30 ].

College students are especially susceptible to developing a dependence on the Internet, more than most other segments of society. This can be qualified to numerous factors including the following: Availability of time; ease of use; the psychological and developmental characteristics of young adulthood; limited or no parental supervision; an expectation of Internet/computer use covertly if not, as some courses are Internet-dependent, from assignments and projects to link with peers and mentors; the Internet offering a way of escape from exam anxiety [ 31 ].

Studies have indicated that IA is associated with different factors. Socio-demographic factors such as age (having lower age) [ 32 ] and male gender [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Reason for internet use related factors such as making new friendships online [ 33 ], getting into relationships online [ 33 ], using the internet less for coursework/assignments [ 33 ], visiting pornographic sites [ 34 ] and playing online games [ 31 , 34 , 38 ]. Time related and other factors such as higher internet usage time [ 37 , 39 ],continuous availability online [ 33 , 35 , 39 ] and mode of internet access [ 35 ]. Clinical and substance related factors such as insomnia [ 40 ], attention deficient disorder and hyperactivity symptoms [ 41 ], being sexual inactive [ 32 ], low self-esteem [ 40 ], failure in academic performance [ 32 ], smoking [ 41 ], and potential addictive personal habits of, drinking alcohol or coffee, and taking drugs [ 34 ]. Besides, mental illness like depression, anxiety and psychological distress [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 ] are associated with internet addiction. This could be based on the application of a general strain theory framework whereby negative emotions that are secondary to depression, anxiety, and psychological distress will be associated positively with internet addiction [ 42 ].

Internet Addiction is now becoming a serious mental health problem among Chinese adolescents. The researchers identified 10.6% to 13.6% of Chinese college students as Internet addicts [ 43 , 44 ]. A study conducted among Taiwan college students reported that the prevalence of Internet Addiction was 15.3% [ 37 ].

The prevalence of Problematic Internet Use (PIU) was greater among university students. For instance, the prevalence was 36.9 to 81% in Malaysian medical students by using the internet addiction questionnaire and Internet Addiction Diagnostic Questionnaire study instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 43 and 31to 79 respectively [ 45 , 46 ], 25.1% in American community university students by using the YIATstudy instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 40 [ 47 ], 40.7% in Iranian university students by utilizing the YIAT study instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 40 [ 48 ], 38.2–63.5% IA in Japanese university students as measured with the YIAT study instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 40 and ≥ 40 respectively [ 36 , 49 ], 16.8% IA in Lebanon University students by utilizing the YIAT study instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 50 [ 40 ], 35.4% IA in Nepal undergraduate students as measured with the YIAT study instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 40 [ 32 ], 40% IA in Jordan University students by utilizing the YIAT study instrument with a cut-offs point of ≥ 50 [ 50 ],19.85% to 42.9% IA in various parts of India as measured with the YIAT study instrument with a cut-offs point of 31to79, ≥ 50 and ≥ 50 respectively [ 33 , 35 , 39 ], 12% IA to 34.7% (PIU) in Greek University students by utilizing the Problematic Internet Use Diagnostic Test study instrument with no stated cut-offs point [ 34 ], 1.6% IA in Turkey students by using the Young’s Internet Addiction Scale study instrument with a cut-offs point of 70–100 [ 41 ].

In general, the main reason why youths are at particular risk of internet addiction is that they spend most of their time on online gaming and social applications like online social networking such as Twitter, Facebook, and telegrams [ 51 ].

Even though developing countries shares for a large magnitude of internet addiction, indicating the public health impact of the problem in the region, much is not known about the occurrence rate of the problem in these regions in general and Ethiopia in particular. As a result, trustworthy assessments of internet addiction in university students in these circumstances are required for delivering a focused intervention geared towards addressing the associated factors.

Moreover, it will be a ground for the expansion of national and international plans, procedures, and policy. At last but not least, the findings from this study will provide significant implications for counsellors and policymakers to prevent students' Internet addiction. Hence, this a community university-based cross-sectional study aimed and assessed the prevalence and associated factors of internet addiction among Wollo university students.

Research questions

The purpose of this study was to measure prevalence and associated factors of IA among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia. The specific research questions that guided the present study were:

What is the prevalence of IA among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia?

What are the associated factors of IA?

Methods and materials

Study area and period.

The study was done at Wollo University, Dessie campus that is found in South Wollo Zone, Amhara Regional State which is 401 kms far from Addis Ababa, Northeastern Ethiopia. It had 5 colleges and 2 schools and a total of 62 departments. The number of regular students in 2018/2019 is 7248; among these 4009 are males and 3239 are females. The study was conducted from April 10 to May 10/ 2019. The sample size was determined using single population proportion formula, taking a 50% prevalence of Internet Addiction with the following assumption: 95% CI, 5% margin of error, 10% non-response rate, and a design effect of 1.5. So, the final sample size was 603.

Sampling technique and procedure

A multistage cluster sampling technique was used to recruit study participants. In the first stage, by the use of the lottery method, two colleges (College of medicine and health sciences, and College of natural sciences, and one school (school of law)) were selected. In the second stage, 18 departments (9 from the college of medicine and health science, 8 from the college of natural science and 1 from the school of law) were selected. Students were selected proportionally from the given departments based on the number of students of a particular.

Study design

A community university-based cross-sectional study was carried out to assess the prevalence and associated factors of Internet Addiction among undergraduate students at Wollo University, Amhara Region, Ethiopia.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All generic regular undergraduate adult students whose ages were 18 years and above, and who were present at the time of data collection. Students who gave consent to the study were recruited. The study participants who are blind and severely ill were excluded from the study.

Study instruments

Self-administered, well-structured, and organized English version questionnaire was disseminated to students, and data were collected from the individual student. The questionnaires comprised six parts. The first part consisted of socio-demographic details; a structured questionnaire was used to assess sociodemographic characteristics. The second part consists of Young’s Internet Addiction Test (YIAT); a structured, self-administered questionnaire was used to assess Internet Addiction. The YIAT [ 7 ] is the most commonly used measure of Internet Addiction among adults [ 52 ]. It includes 20 questions with a scoring of 1–5 for each question and a total maximum score of 100. Based on scoring subjects would be classified into normal users (0–30), mild (31–49), moderate (50–79), and severe (80–100) Internet Addiction groups. Mild Internet addiction, moderate Internet addiction, and severe Internet Addiction were considered as having an Internet Addiction [ 53 , 54 , 55 ]. YIAT-20 showed that it is more reliable in University students. The Cronbach α in the present study was 0.89. The third part time-associated factors; a self-report structured questionnaire was prepared from different kinds of literature to assess time-associated factors (such as Internet use experience in months and Internet use per day in hours). The fourth part reasons for internet use; a structured questionnaire was used to assess the reasons for internet use. The fifth part psychoactive substance use-associated factors; a self-report questionnaire was used to assess the current use of psychoactive substances (Khat, Cigarette, Alcohol, and Cannabis), and the last part mental health problem-associated factors and it was assessed by Kessler10 (K10). The K10 scale [ 56 ] is a simple measure of mental distress. The K10-item scale, which has been translated into Amharic and validated in Ethiopia [ 57 ], was used to measure mental distress (depressive, anxiety, and somatic symptoms). The internal consistency of the K10 psychological distress scale in the present study was checked with a reliability assessment and was found to be 0.86 [ 58 , 59 , 60 ]. Scores will range from 10 to 50. A score under 20 is likely to be well, a score of 20–24 is likely to have mild mental distress, a score of 25–29 is likely to have moderate mental distress and a score of 30 and over are likely to have severe mental distress. Study participants with a score of 20 or more points on the K10 Likert scale were considered as having mental distress [ 61 ].

Data quality control

A structured self-administered questionnaire was developed in English and would be translated to Amharic language and again translated back into English to ensure consistency. Data collectors and supervisors would be trained for two days on the objective of the study, the content of the questionnaire, and the data collection procedure. Data would be pilot tested on 5% of the total sample size outside the study area and based on feedback obtained from the pilot test; the necessary modification would be done. During the study period, the collected data would be checked continuously daily for completeness by principal investigator and supervisor in the respective departments.

Data processing and analysis

Quantitative data would be cleaned, coded, and entered into Epi-data 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Descriptive data would be presented by a table, graphs, charts, and means. Multicollinearity test was checked by using standard error and there was no correlation between independent variables. The association between independent variables and Internet Addiction would be made using a binary logistic regression model and all independent variables having p value ≤ 0.25 would be included in multiple logistic regression models. A p value less than 0.05 and Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) not inclusive of one would be considered as statically significant and would be used to determine predictors of Internet Addiction in the final model. Hosmer–Lemeshow test was done to check model fitness and the model was fit.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 603 participants were involved with a response rate of 90.9% (n = 548). However, the rest 9.1% (n = 55) participants were excluded due to incomplete responses. The mean age of the respondents was 21.4 (SD 1.8) years, the minimum and maximum age of the participants was 18 years and 30 years respectively. More than half of, 291 (53.1%) of respondents were males. Many of the study participants had a practice of using the internet for more than twelve months, 321 (58.6%). About 501 (91.4%), 268 (48.9%), 433 (79%) were using the internet less than five hours per day, most common mode of internet access Wi-Fi, and log in and off occasionally during the day respectively. The study participants with current khat use, current cigarette smoking, current alcohol use, and current cannabis use were 19.0%, 11.3%, 25.4%; and 4.0% respectively. About 19.3% of the participants had mental distress (Table 1 ).

Prevalence of Internet addiction

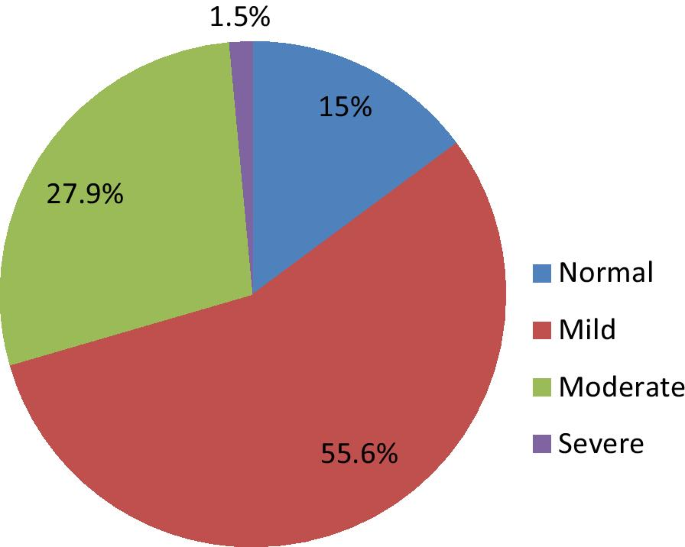

The prevalence of IA was 466 (85%) of the 305(55.6%), 153(27.9%), 8(1.5%) mild, moderate, and severe Internet Addiction respectively. Nevertheless, the remaining 82 (15%) are free from Internet Addiction (Fig. 1 ). Participants who login permanently had a greater figure of IA than those who log in and off occasionally during the day (92.2% versus 83.1%). Those who used the internet for about six months had a greater prevalence of Internet Addiction than those who used greater than twelve months (91.6% versus 84.1%) (Table 2 ).

Internet Addiction by severity among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 548)

Reasons for internet use among Wollo University students

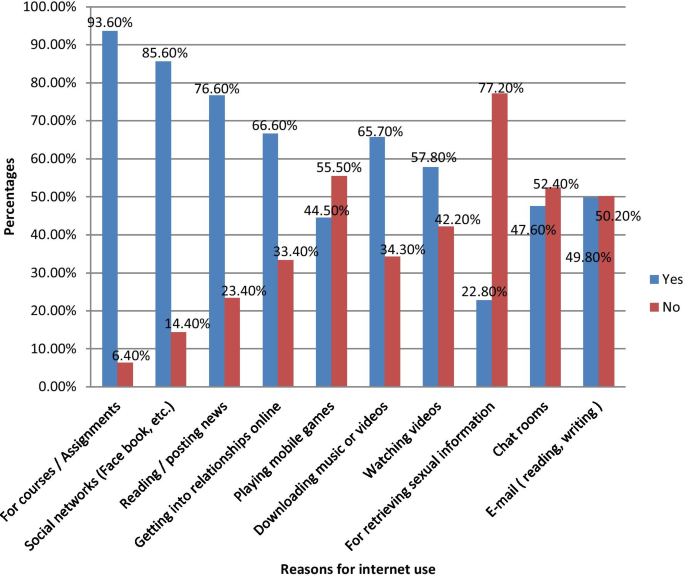

The furthermost frequent reasons for internet use among Wollo University undergraduate students were using the internet for courses / assignments (93.6%), for social networks (Facebook, etc.) (85.6%), for reading / posting news (76.6%), for getting into relationships online (66.6%),for playing mobile games (44.5%), for downloading music or videos (65.7%), for watching videos (57.8%),for retrieving sexual information (22.8%), for chat rooms (47.6%) and for e-mail ( reading, writing) (49.8%) (Fig. 2 ).

Reasons for internet use among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 548)

Factors associated with internet addiction in the univariate analysis

Time related factors.

Duration of using the internet was associated with Internet Addiction i.e. students who used the internet for more than a year was 51% lower risks of having internet addiction than their counterparts (OR=0.49; CI 0.24–0.96). Respondents who were spending more time on the internet were more likely to develop Internet Addiction than their counterparts (OR=8.87; CI 1.21–65.25).

Mode of internet access was related to Internet Addiction i.e. those who used mobile internet were 45% lower risks of having Internet Addiction than those who used data cards (OR = 0.55; 95% CI 0.28–1.07).Participants who were permanently online were most likely to have Internet Addiction than those who were not (OR=2.39; 95% CI 1.16–4.93).

Reasons for internet use related factors

Study participants who played mobile games online were more likely to develop Internet Addiction than those who were not played mobile games (OR = 2.67; 95% CI 1.57–4.52). Those who downloaded music or videos were higher risks of having Internet Addiction than those who didn’t (OR = 1.62; 95% CI 1.00–2.61). Study participants who watched the video online were most likely to have Internet Addiction than those who didn’t watch (OR=1.94; 95% CI 1.21–3.12).

Psychoactive substance use related factors

Those who chewed khat currently were higher odds of having Internet Addiction than those who were not (OR = 5.33; 95% CI 1.90–14.91). Respondents who smoked cigarettes currently were more likely to have Internet Addiction than their counterparts (OR = 12.20; 95% CI 1.67–89.28).

Those who used alcohol currently were greater risks of having Internet Addiction than those who hadn't (OR = 2.76; 95% CI 1.38–5.51).

Mental health problem related factors

Study participants who had mental distress were four times more likely to develop Internet Addiction than those who didn't have mental distress (OR = 4.26; 95% CI 1.68–10.81) (Table 2 ).

Factors associated with internet addiction in the multivariate analysis

In the final model, spending more time on the internet, having mental distress and playing online games were the factors associated with Internet Addiction. Moreover, current khat chewing and current alcohol use were the independent predictors for Internet Addiction. Using the internet for more than twelve months and using the internet by mobile internet were negatively associated with Internet Addiction (Table 2 ).

Discussions

The present study aims to assess the prevalence and associated factors of Internet Addiction among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia. The prevalence of IA was 85% (n = 466). In the final model; spending more time on the internet, having mental distress and playing online games were the factors associated with Internet Addiction. Moreover, current khat chewing and current alcohol use were the independent predictors for Internet Addiction. Using the internet for more than twelve months and using the internet by mobile internet were negatively associated with Internet Addiction.

The prevalence of Internet Addiction in the present study was higher than the prevalence of Internet Addiction that was done in different universities such as three medical schools across three countries ( Croatia, India, and Nigeria) 49.7% [ 55 ], Malaysian 36.9% to 81% [ 45 , 46 ], American community 25.1% [ 47 ], Iran 12.5 to 40.7% [ 48 , 62 , 63 ], Japan 38.2% to 63.5% [ 36 , 49 ], Greek 12% to 30.1% [ 54 , 64 ], Jordan 40% [ 50 ], Lebanon 16.8% [ 40 ], Nepal 35.4% [ 32 ] and in different parts of India 19.85% to 42.9% [ 33 , 35 , 39 ]. The discrepancy might be due to the cut-off point of YIAT-20, instrument difference, mental health policy, a cultural difference like time utilization, the difference in study participants such as in our study the participants were from two colleges and one school, and all participants were internet users, sample size and the time difference between the studies. The study in Malaysian University was conducted among medical students only and focusing on mild Internet Addiction and moderate Internet Addiction and not on severe Internet addiction.

In our study spending more time on the internet was 10 times more likely to develop Internet Addiction than those who are spending less time. The finding of this study is in line with similar studies done on college students in Taiwan and three medical schools across three countries (Croatia, India, and Nigeria) [ 37 , 55 ]. The possible explanation for the association between Internet usage time and Internet Addiction is that it might be as much a symptom as it is a cause. However, this study design was cross-sectional and no causal relationship can be clarified, further studies ought to examine whether Internet usage time is an essential factor for determining Internet addiction.

Likewise, students who had mental distress were 2.7 times more likely to develop Internet Addiction as compared to their counterparts. Study findings in these areas showed that students who had mental distress were related to higher levels of Internet Addiction than students who hadn’t mental distress [ 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 50 ]. This could be due to the Khantzian’s [ 65 ] self-medication hypothesis, indicating that mentally distressed university students might come to rely on the Internet as a method for coping with their mental distress. Hence, they will devote more and more time on the Internet and headway toward addiction if their mental distress symptoms are not cured [ 66 ].Students who had playing online games were 2.4 times higher to have Internet Addiction than their counterparts. A similar finding was also reported in Greek University and others [ 34 , 38 , 54 , 67 ].

Furthermore, students who chewed khat currently were three times most likely to develop Internet Addiction than students who reported no current khat chewing which is in line with the study finding in Greek University students [ 34 ]. In this study, students who drank alcohol currently were 2.3 times most likely to have Internet Addiction as compared with students who didn’t drink alcohol. Other studies reported a similar finding [ 17 , 34 , 68 , 69 ]. Probable reasons involve; based on the problem behavior theory, the problem behaviors (Internet Addiction and substance abuse) are inter-related.

Students who used the internet by mobile internet were 60% of lower risks of having Internet Addiction as compared to those students who used data cards. This might be due to inadequate finance to use the internet on mobile internet. So, the students may refrain from using the internet through mobile internet. Students who used the internet for more than 12 months were 52% less likely to have Internet Addiction than their counterparts. The current finding is not supported by other studies in the world. The present study has limitations such as alpha inflation from multiple testing and the analysis did not account for the complex sampling strategy in adjusting the standard errors.

The current study documents a high prevalence of Internet Addiction among Wollo University students. The factors associated with Internet Addiction were spending more time on the internet, having mental distress, playing online games, current khat chewing, and current alcohol use. As internet addiction becomes an evident public health problem, carrying out public awareness campaigns on its severity and negative consequences of excruciating agonies may be a fruitful strategy to decrease its prevalence and effect. Campaign programs may aim at informing the adults on the phenomenon of internet addiction, knowing the possible risks and symptoms. Besides to this, a collaborative work among all stakeholders is important to develop other trendy, adaptive, ethical and sustainable countermeasures.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are not publicly available due to ethics regulations but may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted odds ratio

Confidence interval

Crude odds ratio

- Internet addiction

Statistical package for social science

Young’s internet addiction test

Bremer J. The internet and children: advantages and disadvantages. Child Adolesc Psychiat Clin. 2005;14(3):405–28.

Article Google Scholar

Swaminath G. Internet addiction disorder: fact or fad? Nosing into nosology. Indian J Psychiat. 2008;50(3):158.

Dargahi H, Razavi S. Internet addiction and its related factors: a study of an Iranian population. 2007.

Tereshchenko S, Kasparov E. Neurobiological risk factors for the development of internet addiction in adolescents. Behav Sci. 2019;9(6):62.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Griffiths M. Does internet and computer" addiction" exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychol Behav. 2000;3(2):211–8.

Kuss D, Griffiths M. Internet addiction in psychotherapy. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

Google Scholar

Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1(3):237–44.

Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P, editors. Incidence and correlates of pathological internet usage. Paper presented art the 105th annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Chicago, Illinois; 1997.

Young KS, De Abreu CN. Internet addiction. A handbook and guide to evaluation. 2011.

Scherer K. College life online of college life and development. Healthy Unhealthy Internet Use J. 1997;38(6):655–65.

Blos P. On adolescence: psychoanalytic interpretation. Reissue. New York, NY: Free Press; 1966.

Karacic S, Oreskovic S. Internet addiction through the phase of adolescence: a questionnaire study. JMIR Mental Health. 2017;4(2):e11.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Achenbach TM, Becker A, Döpfner M, Heiervang E, Roessner V, Steinhausen HC, et al. Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiat. 2008;49(3):251–75.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Graovac M. Adolescent u obitelji. Medicina Fluminensis: Medicina Fluminensis. 2010;46(3):261–6.

ZboralskiACD K, OrzechowskaDEF A, TalarowskaDE M, DarmoszAB A, JaniakGF A, JaniakGF M, et al. The prevalence of computer and Internet addiction among pupils Rozpowszechnienie uzależnienia od komputera i Internetu. Postepy Hig Med Dosw(online). 2009;63:8–12.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(9):3528–52.

Ko CH, Yen J-Y, Yen CF, Chen CS, Weng CC, Chen CC. The association between Internet addiction and problematic alcohol use in adolescents: the problem behavior model. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(5):571–6.

Bradley BP. Behavioural addictions: common features and treatment implications. Br J Addict. 1990;85(11):1417–9.

Holden C. 'Behavioral'addictions: do they exist?: American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2001.

Miele GM, Tilly SM, First M, Frances A. The definition of dependence and behavioural addictions. Br J Addict. 1990;85(11):1421–3.

Greenberg JL, Lewis SE, Dodd DK. Overlapping addictions and self-esteem among college men and women. Addict Behav. 1999;24(4):565–71.

Buckley RC. Adventure thrills are addictive. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1915.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shahnaz I, Karim A. The impact of internet addiction on life satisfaction and life engagement in young adults. Univ J Psychol. 2014;2(9):273–84.

Park M-H, Park E-J, Choi J, Chai S, Lee J-H, Lee C, et al. Preliminary study of Internet addiction and cognitive function in adolescents based on IQ tests. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(2–3):275–81.

Akhter N. Relationship between internet addiction and academic performance among university undergraduates. Educ Res Rev. 2013;8(19):1793–6.

Usman N, Alavi M, Shafeq SM. Relationship between internet addiction and academic performance among foreign undergraduate students. Proced Soc Behav Sci. 2014;114:845–51.

Pfaff DW, Volkow ND. Neuroscience in the 21st century: from basic to clinical: Springer, Berlin, 2016.

Alavi SS, Alaghemandan H, Maracy MR, Jannatifard F, Eslami M, Ferdosi M. Impact of addiction to internet on a number of psychiatric symptoms in students of isfahan universities, iran, 2010. Int J Prevent Med. 2012;3(2):122.

Xiuqin HHZ, Mengchen L, Jinan W, Ying Z, Ran T. Mental health, personality, and parental rearing styles of adolescents with Internet addiction disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(4):401–6.

Alavi SSAH, Maracy MR, Jannatifard F, Eslami M, Ferdosi M. Impact of addiction to internet on a number of psychiatric symptoms in students of Isfahan universities. Iran Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(2):122–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kandell JJ. Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1(1):11–7.

Bhandari PM, Neupane D, Rijal S, Thapa K, Mishra SR, Poudyal AK. Sleep quality, internet addiction and depressive symptoms among undergraduate students in Nepal. BMC Psychiat. 2017;17(1):106.

Krishnamurthy S, Chetlapalli SK. Internet addiction: prevalence and risk factors: A cross-sectional study among college students in Bengaluru, the Silicon Valley of India. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59(2):115.

Frangos CC, Frangos CC, Sotiropoulos I. Problematic internet use among Greek university students: an ordinal logistic regression with risk factors of negative psychological beliefs, pornographic sites, and online games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1–2):51–8.

Gedam SR, Ghosh S, Modi L, Goyal A, Mansharamani H. Study of internet addiction: Prevalence, pattern, and psychopathology among health professional undergraduates. Indian J Soc Psychiat. 2017;33(4):305.

Kitazawa M, Yoshimura M, Murata M, Sato-Fujimoto Y, Hitokoto H, Mimura M, et al. Associations between problematic internet use and psychiatric symptoms among university students in Japan. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(7):531–9.

Lin M-P, Ko H-C, Wu JY-W. Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors associated with Internet addiction in a nationally representative sample of college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(12):741–746.

Petry NM, O'Brien CP. Internet gaming disorder and the DSM‐5. 2013.

Gupta A, Khan AM, Rajoura O, Srivastava S. Internet addiction and its mental health correlates among undergraduate college students of a university in North India. J Family Med Primary Care. 2018;7(4):721.

Younes F, Halawi G, Jabbour H, El Osta N, Karam L, Hajj A, et al. Internet addiction and relationships with insomnia, anxiety, depression, stress and self-esteem in university students: a cross-sectional designed study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0161126.

Seyrek S, Cop E, Sinir H, Ugurlu M, Şenel S. Factors associated with Internet addiction: Cross-sectional study of Turkish adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2017;59(2):218–22.

Jun S, Choi E. Academic stress and Internet addiction from general strain theory framework. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;49:282–7.

Chou C, Hsiao M-C. Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: the Taiwan college students’ case. Comput Educ. 2000;35(1):65–80.

Yang T, Yu L, Oliffe JL, Jiang S, Si Q. Regional contextual determinants of internet addiction among college students: a representative nationwide study of China. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(6):1032–7.

Ching SM, Awang H, Ramachandran V, Lim S, Sulaiman W, Foo Y, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with internet addiction among medical students-A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(1):7–11.

Haque M, Rahman NAA, Majumder MAA, Haque SZ, Kamal ZM, Islam Z, et al. Internet use and addiction among medical students of Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin. Malaysia Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:297.

Jelenchick LA, Becker T, Moreno MA. Assessing the psychometric properties of the internet addiction test (IAT) in US college students. Psychiat Res. 2012;196(2–3):296–301.

Bahrainian SA, Alizadeh KH, Raeisoon M, Gorji OH, Khazaee A. Relationship of Internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. J Prevent Med Hygiene. 2014;55(3):86.

Tateno M, Teo AR, Shirasaka T, Tayama M, Watabe M, Kato TA. Internet addiction and self-evaluated attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder traits among Japanese college students. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70(12):567–72.

Al-Gamal E, Alzayyat A, Ahmad MM. Prevalence of internet addiction and its association with psychological distress and coping strategies among university students in Jordan. Perspect Psychiat Care. 2016;52(1):49–61.

Kuss DJ, Van Rooij AJ, Shorter GW, Griffiths MD, van de Mheen D. Internet addiction in adolescents: prevalence and risk factors. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(5):1987–96.

Frangos CC, Frangos CC, Sotiropoulos I, editors. A meta-analysis of the reliabilty of young’s internet addiction test. Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering; 2012: World Congress on Engineering London, United Kingdom.

Young KS. Internet addiction test. Center for on-line addictions. 2009.

Tsimtsiou Z, Haidich A-B, Spachos D, Kokkali S, Bamidis P, Dardavesis T, et al. Internet addiction in Greek medical students: an online survey. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(3):300–4.

Balhara YPS, Gupta R, Atilola O, Knez R, Mohorović T, Gajdhar W, et al. Problematic internet use and its correlates among students from three medical schools across three countries. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):634–8.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2003;60(2):184–9.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-L, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–76.

Tadegge AD. The mental health consequences of intimate partner violence against women in Agaro Town, southwest Ethiopia. Trop Doct. 2008;38(4):228–9.

Hanlon C, Medhin G, Selamu M, Breuer E, Worku B, Hailemariam M, et al. Validity of brief screening questionnaires to detect depression in primary care in Ethiopia. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:32–9.

Fekadu A, Medhin G, Selamu M, Hailemariam M, Alem A, Giorgis TW, et al. Population level mental distress in rural Ethiopia. BMC Psychiat. 2014;14(1):194.

Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(6):494–7.

Arbabisarjou A, Gorgich EAC, Barfroshan S, Ghoreishinia G. The Association of internet addiction with academic achievement, emotional intelligence and strategies to prevention of them from student’s perspectives. Int J Hum Cult Stud (IJHCS). 2016;3(1):1656–66.

Gorgich EAC, Moftakhar L, Barfroshan S, Arbabisarjou A. Evaluation of internet addiction and mental health among medical sciences students in the southeast of Iran. Shiraz E Med J. 2018;19(1).

Frangos CCFC, Sotiropoulos I. A meta-analysis of the reliability of young’s internet addiction test. A meta-analysis of the reliability of young’s internet addiction test. WCE. 2012;1:368–71.

Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiat. 1997;4(5):231–44.

Yen J-Y, Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Wu H-Y, Yang M-J. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of Internet addiction: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(1):93–8.

Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

Sajeev Kumar P, Prasad N, Raj Z, Abraham A. Internet addiction and substance use disorders in adolescent students-a cross sectional study. J Int Med Dent. 2015;2:172–9.

Ko C-H, Yen J-Y, Chen C-C, Chen S-H, Wu K, Yen C-F. Tridimensional personality of adolescents with internet addiction and substance use experience. Can J Psychiat. 2006;51(14):887–94.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University for supporting the research in different ways. We extend our heartfelt thanks to the student service directorate office for providing us the necessary information. We are grateful to all the students who participated in the study.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

Yosef Zenebe, Kunuya Kunno, Meseret Mekonnen, Ajebush Bewuket, Mengesha Birkie, Mogesie Necho, Muhammed Seid & Million Tsegaw

Department of Pharmacy, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YZ and KK designed and supervised the study, carried out the analysis, and interpreted the data; MM, AB, MB, MNA, MS, MT, and BA assisted in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and YZ wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yosef Zenebe .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was conducted after getting ethical clearance from Wollo University College of medicine and health science institutional review board with a certificate of approval number: CMHS/508/2019. A formal letter of permission was obtained from the student service directorate of Wollo University. The respondents were informed about the aim of the study. Confidentiality was maintained by giving codes for respondents rather than recording their names. The privacy of the respondents was also assured since the anonymous data collection procedure was followed. The data collectors have informed the clients that they had the full right to discontinue or refuse to participate in the study. Written consent was obtained from each participant before administering the questionnaire.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zenebe, Y., Kunno, K., Mekonnen, M. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of internet addiction among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia: a community university-based cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol 9 , 4 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00508-z

Download citation

Received : 21 May 2020

Accepted : 21 December 2020

Published : 06 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00508-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

“Internet Addiction”: a Conceptual Minefield

- Open access

- Published: 19 September 2017

- Volume 16 , pages 225–232, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Francesca C. Ryding 1 &

- Linda K. Kaye 1

17k Accesses

55 Citations

19 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

With Internet connectivity and technological advancement increasing dramatically in recent years, “Internet addiction” (IA) is emerging as a global concern. However, the use of the term ‘addiction’ has been considered controversial, with debate surfacing as to whether IA merits classification as a psychiatric disorder as its own entity, or whether IA occurs in relation to specific online activities through manifestation of other underlying disorders. Additionally, the changing landscape of Internet mobility and the contextual variations Internet access can hold has further implications towards its conceptualisation and measurement. Without official recognition and agreement on the concept of IA, this can lead to difficulties in efficacy of diagnosis and treatment. This paper therefore provides a critical commentary on the numerous issues of the concept of “Internet addiction”, with implications for the efficacy of its measurement and diagnosticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Internet Addiction

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What Is Internet Addiction (IA)?

Traditionally, the term addiction has been associated with psychoactive substances such as alcohol and tobacco; however, behaviours including the use of the Internet have more recently been identified as being addictive (Sim et al. 2012 ). The concept of IA is generally characterised as an impulse disorder by which an individual experiences intense preoccupation with using the Internet, difficulty managing time on the Internet, becoming irritated if disturbed whilst online, and decreased social interaction in the real world (Tikhonov and Bogoslovskii 2015 ). These features were initially proposed by Young ( 1998 ) based on the criteria for pathological gambling (Yellowlees and Marks 2007 ), and have since been adapted for consideration within the DSM-5. This has been well received by many working in the field of addiction (Király et al. 2015 ; Petry et al. 2014 ), and has been suggested to enable a degree of standardisation in the assessment and identification of IA (King and Delfabbro 2014 ). However, there is still debate and controversy surrounding this concept, in which researchers acknowledge much conceptual disparity and the need for further work to fully understand IA and its constituent disorders (Griffiths et al. 2014 ).