The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Psychology, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. [email protected].

- PMID: 31384033

- DOI: 10.1038/s41583-019-0202-9

Mental imagery can be advantageous, unnecessary and even clinically disruptive. With methodological constraints now overcome, research has shown that visual imagery involves a network of brain areas from the frontal cortex to sensory areas, overlapping with the default mode network, and can function much like a weak version of afferent perception. Imagery vividness and strength range from completely absent (aphantasia) to photo-like (hyperphantasia). Both the anatomy and function of the primary visual cortex are related to visual imagery. The use of imagery as a tool has been linked to many compound cognitive processes and imagery plays both symptomatic and mechanistic roles in neurological and mental disorders and treatments.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Cognitive Neuroscience / methods

- Cognitive Neuroscience / trends*

- Hippocampus / diagnostic imaging

- Hippocampus / physiology

- Imagination / physiology*

- Memory / physiology

- Nerve Net / diagnostic imaging

- Nerve Net / physiology*

- Visual Cortex / diagnostic imaging

- Visual Cortex / physiology*

- Visual Perception / physiology*

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Visual Imagery

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Neurocognition Follow Following

- Family Structure Follow Following

- Family Functioning Follow Following

- Parent-Child Relationship Follow Following

- Visual perception (Psychology) Follow Following

- Hallucinations Follow Following

- Near-Death Experiences Follow Following

- Youth & Adolescence Follow Following

- Mental Images Follow Following

- Emotions in the workplace Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Frontiers in Psychology

- Research Topics

Creativity and Mental Imagery

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Creativity is one of the most mysterious and controversial topic in Cognitive Psychology. Nevertheless, it is important at both individual, social and cultural level, being involved in problem solving, visual and verbal thinking, scientific invention and discovery, industrial design, works of art, dance, and ...

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Neural Basis Of Visual Imagery Research Paper

View sample Neural Basis Of Visual Imagery Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Human thought makes use of different forms of mental representation; some language-like and some more visual or spatial. The term ‘mental imagery’ refers to the latter. It plays a central role in many cognitive abilities, from creative problem solving to strategies for improving memory. This research paper will review the current state of knowledge on the neural bases of mental imagery, beginning with the controversies in cognitive psychology that motivated the neuroscience research.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, 1. imagery, verbal thought, and perception.

Much of the early history of imagery research was devoted to discriminating imagery from verbal thought, and characterizing some of its differences in functional information-processing terms. Allan Paivio (e.g., 1971) addressed these issues within the context of memory research. He demonstrated that, in ostensibly verbal learning tasks, imagery affected memory encoding. Though a program of research in which subjects learned words, which either lent themselves to concrete images or not (e.g., banana vs. vacation), with or without imagery instructions, he gathered evidence in support of a ‘dual coding hypothesis.’ According to this hypothesis, imagery and language are two distinct forms of mental representation. Imagery was therefore helpful in verbal memory tasks because, in effect, it doubled the number of representations being stored.

A challenge to this view came from Zenon Pylyshyn (1973), who questioned the computational feasibility of storing visual images, and raised a number of issues concerning the role of imagery phenomenology in the information processing that underlies thought. This challenge brought an empirical response from Stephen Kosslyn (e.g., 1978), who devised experimental tasks in which the visual-spatial properties of images could be shown to affect subjects’ information processing. For example, when subjects focus their attention on one location within an image, and then shift to a different location, the time taken to shift is directly proportional to the imagined distance (Kosslyn et al. 1978). Findings from the laboratory of Roger Shepard also supported the visual-spatial nature of imagery. In mental image rotation experiments, images took more time to rotate through larger angles (Cooper and Shepard 1973).

As evidence accumulated that imagery is a distinct form of mental representation from linguistic or propositional thought, the question of its relation to visual perception came to force. Early work on this topic was pioneered by Ron Finke (e.g., 1980), who demonstrated many detailed and striking similarities between mental images and percepts. For example, he reported that mental images had similar-shaped fields of resolution to the perceptual visual field.

2. Image Representation: Insights From Neuroscience

The relation between imagery and perception can also be assessed in terms of their respective neural substrates. Indeed, many of the alternative interpretations that plagued the purely behavioral approaches to mental imagery did not apply to the neural data. An initial review of the literature on imagery and the brain, motivated by the need for more decisive evidence concerning the imagery–perception relation, uncovered a variety of relevant findings (Farah 1988). These included numerous findings of parallel impairments of imagery and perception after brain damage, which suggest that the same underlying representations are needed for both.

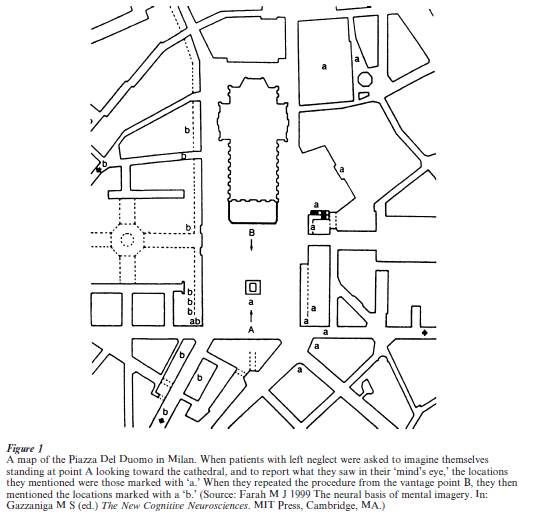

In one of the best-known demonstrations of parallel impairments in imagery and perception. Bisiach and Luzzatti (1978) found that patients with hemispatial neglect for visual stimuli also neglected the contralesional sides of their mental images (that is, the side of their image opposite the side of their brain lesion). Their two right-parietal-damaged patients were asked to imagine a well-known square in Milan, shown in Fig. 1. When they were asked to describe the scene from vantage point A on the map, they tended to name more landmarks on the cast side of the square (marked with lower case a’s in the figure); that is, they named the landmarks on the right side of the imagined scene. When they were then asked to imagine the square from the opposite vantage point, marked B on the map, they reported many of the landmarks previously omitted (because these were now on the right side of the image) and omitted some of those previously reported.

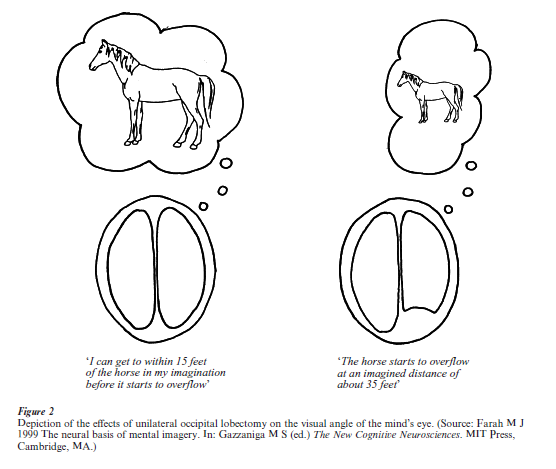

Imagery and perception also share representations at relatively early stages of visual processing. This point was demonstrated by a patient with blindness in half of her visual field following occipital resection (Farah et al. 1992). If mental imagery consists of activating representations in the occipital lobe, then it should be impossible to form images in regions of the visual field that are blind due to occipital lobe destruction. This predicts a reduced maximum image size, or visual angle of the mind’s eye, in this patient. By asking her to report the distance of imagined objects such as a horse, breadbox, or ruler when they are visualized as close as possible without ‘overflowing’ her imaginal visual field, one could compute the visual angle of that field before and after her surgery. It was found that the size of her biggest possible image was reduced after surgery, as represented in Fig. 2. Furthermore, the separate measurement of maximal image size in the vertical and horizontal dimensions showed that only the horizontal dimension of her imagery field was reduced significantly. These results provide strong evidence for the use of occipital visual representations during imagery.

The results of functional neuroimaging studies in normal subjects have been, on the whole, supportive of shared representations for visual mental images and percepts. Early studies with event-related potentials (e.g., Farah et al. 1989) and SPECT (e.g., Goldenberg et al. 1989) implicated a cortical visual locus and, as newer methods allowed better localization, it has been possible to test far more specific hypotheses concerning the precise areas within visual cortex that are recruited for mental imagery (Kosslyn and Ochsner 1994; Roland and Gulyas 1994).

3. Brain Systems For Image Generation

If imagery consists of activating some of the same cortical visual areas used for perception, this raises the question of how these representations become activated in the absence of a stimulus. Whereas one cannot see a familiar object without recognizing it, one can think about familiar objects without inexorably calling to mind a visual mental image. This suggests that the activation of visual representations in imagery is a separate voluntary process, needed for image generation but not for visual perception and object recognition.

Neuropsychological evidence for such a process comes from patients whose perception and general memory are preserved, but who cannot visualize objects or scenes from memory. This is the profile of abilities that would be expected given an impairment of image generation per se. A number of such cases have been reported in the neurological literature, with lesions generally being located in the posterior left hemisphere. In one such case (Farah et al. 1988), the imagery impairment was demonstrated in a number of ways, including a sentence verification task developed by Eddy and Glass (1981). Half of the sentences required the use of visual imagery to verify them (e.g., ‘A grapefruit is larger than a cantaloupe’), and half did not (e.g., ‘The US government functions under a two-party system’). Eddy and Glass had shown that normal subjects find the two sets of questions to be of equal difficulty (as did right-hemisphere-damaged control subjects tested by Farah et al. 1988), and that performance on the imagery questions was impaired selectively by visual interference, thus validating them as imagery questions. RM showed a selective deficit for imagery on this validated task: He performed virtually perfectly on the nonimagery questions, and performed significantly worse on the imagery questions.

RM was also tested on imagery for the colors of objects, using black and white drawings of characteristically-colored objects (e.g., a cactus, an ear of corn) for which he was to select the appropriate colored pencil. His imagery was further tested with drawing tasks. By these measures, too, his imagery was poor, despite adequate color perception and object recognition ability.

In subsequent years, a small number of additional cases of image generation deficit have been reported (e.g., Goldenberg 1992, Grossi et al. 1986, Riddoch 1991), as well as similar but weaker dissociations in subgroups of patients in group studies (Bowers et al. 1991, Goldenberg 1989, Goldenberg and Artner 1991, Stangalino et al. 1995).

What parts of the brain carry out image generation? This question has evoked controversy. Although mental imagery was for many years assumed to be a function of the right hemisphere, Ehrlichman and Barrett (1983) pointed out that there was no direct evidence for this assumption. Most of the patient-based research supports a left-hemisphere basis for image generation (see Tippett 1992, Trojano and Grossi 1994 for reviews; see Sergent 1990 for a different position). However, for questions of localization, we can also turn to functional neuroimaging.

Not all neuroimaging studies of visual imagery are appropriate for localizing image generation per se. The study must be designed in a way that can isolate this process, separated from perceptual and memory processing more generally. A large number of studies do meet this criterion, including those done with ERP, SPECT, PET and fMRI (see Farah 1999 for a review); in most cases, but not all, foci of activity are observed in the left inferior temporo-occipital region.

Although the bulk of evidence favors a left-hemisphere superiority for image generation, it also suggests that in most individuals both hemispheres possess some image generation ability. This hypothesis explains both the rarity of cases of image generation deficit after brain damage, as well as the asymmetries observed in neuroimaging studies, and the fact that when impairments are observed after damage, the left or dominant hemisphere is implicated.

Bibliography:

- Bisiach E, Luzzatti C 1978 Unilateral neglect of representational space. Cortex 14: 129–33

- Bowers D, Blonder L X, Feinberg T, Heilman K M 1991 Differential impact of right and left hemisphere lesions on facial emotion and object imagery. Brain 11: 2593–609

- Cooper L A, Shepard R N 1973 Chronometric studies of the rotation of mental images. In: Chase W G (ed.) Visual Information Processing. Academic Press, New York

- Eddy P, Glass A 1981 Reading and listening to high and low imagery sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 20: 333–45

- Ehrlichman H, Barrett J 1983 Right hemispheric specialization for mental imagery: A review of the evidence. Brain and Cognition 2: 55–76

- Farah M J 1988 The neural basis of mental imagery: Converging evidence from brain-damaged and normal subjects. In: Bellugi E A U (ed.) Spatial Cognition: Brain Gases and Development. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Farah M J 1999 The neural basis of mental imagery. In: Gazzaniga M S (ed.) The New Cognitive Neurosciences. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Farah M J 2000 The Cognitive Neuroscience of Vision. Blackwell, Oxford

- Farah M J, Peronnet F 1989 Event-related potentials in the study of mental imagery. Journal of Psychophysiology 3: 99–109

- Farah M J, Levine D N, Calvanio R 1988 A case study of mental imagery deficit. Brain and Cognition 8: 147–64

- Farah M J, Soso M J, Dasheiff R M 1992 Visual angle of the mind’s eye before and after unilateral occipital lobectomy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 18: 1–6

- Finke R A 1980 Levels of equivalence in imagery and perception. Psychological Review 87: 113–32

- Goldenberg G 1989 The ability of patients with brain damage to generate mental visual images. Brain 112: 305–25

- Goldenberg G 1992 Loss of visual imagery and loss of visual knowledge–a case study. Neuropsychologia 30: 1081–99

- Goldenberg G, Artner C 1991 A Visual imagery and knowledge about the visual appearance of objects in patients with posterior cerebral artery lesions. Brains and Cognition 15: 160–86

- Goldenberg G, Podreka I, Steiner M, Willmes K, Suess E, Dseoke L 1989 Regional cerebral blood flow patterns in visual imagery. Neuropsychologia 27: 641–64

- Grossi D, Orsini A, Modafferi A 1986 Visuoimaginal constructional apraxia: On a case of selective deficit of imagery. Brain and Cognition 5: 255–67

- Kosslyn S M 1978 Measuring the visual angle of the mind’s eye. Cognitive Psychology 10: 356–89

- Kosslyn S M, Ochsner K N 1994 Trends in Neuroscience 17: 289–91

- Kosslyn S M, Ball T M, Reiser B J 1978 Visual images preserve metric spatial information: Evidence from studies of image scanning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 4: 47–60

- Paivio A 1971 Imagery and Verbal Processes. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

- Pylyshyn Z W 1973 What the mind’s eye tells the mind’s brain: A critique of mental imagery. Psychological Bulletin 80: 1–24

- Riddoch J M 1990 Loss of visual imagery: A generation deficit. Cognitive Neuropsychology 7: 249–73

- Roland P E, Gulyas B 1994 Visual imagery and visual representation. Trends in Neurosciences 17: 281–7; 294–7

- Sergent J 1990 The neuropsychology of visual image generation: Data, method, and theory. Brain and Cognition 13: 98–129

- Stangalino C, Semenza C, Mondini S 1995 Generating visual mental images: Deficit after brain damage. Neuropsychologia 33: 1473–83

- Tippett L J 1992 The generation of visual images: A review of neuropsychological research and theory. Psychological Bulletin 112: 415–32

- Trojano L, Grossi D 1994 A critical review of mental imagery defects. Brain and Cognition 24: 213–43

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Studentshare

- The Theory behind Mental Imagery and Visual Imagery

The Theory behind Mental Imagery and Visual Imagery - Research Paper Example

- Subject: Psychology

- Type: Research Paper

- Level: College

- Pages: 6 (1500 words)

- Downloads: 3

- Author: runtesavanna

Extract of sample "The Theory behind Mental Imagery and Visual Imagery"

- Cited: 0 times

- Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied

CHECK THESE SAMPLES OF The Theory behind Mental Imagery and Visual Imagery

The theory of the society of the simulacrum, what is qualia, visual system processes of incoming information, theory of the society of the simulacrum, dental psychology: pain, the window into jane eyres soul, conceptual analysis, connecting concepts from percy, abram, and berger.

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 October 2017

The visual essay and the place of artistic research in the humanities

- Remco Roes 1 &

- Kris Pint 1

Palgrave Communications volume 3 , Article number: 8 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

9680 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Archaeology

- Cultural and media studies

What could be the place of artistic research in current contemporary scholarship in the humanities? The following essay addresses this question while using as a case study a collaborative artistic project undertaken by two artists, Remco Roes (Belgium) and Alis Garlick (Australia). We argue that the recent integration of arts into academia requires a hybrid discourse, which has to be distinguished both from the artwork itself and from more conventional forms of academic research. This hybrid discourse explores the whole continuum of possible ways to address our existential relationship with the environment: ranging from aesthetic, multi-sensorial, associative, affective, spatial and visual modes of ‘knowledge’ to more discursive, analytical, contextualised ones. Here, we set out to defend the visual essay as a useful tool to explore the non-conceptual, yet meaningful bodily aspects of human culture, both in the still developing field of artistic research and in more established fields of research. It is a genre that enables us to articulate this knowledge, as a transformative process of meaning-making, supplementing other modes of inquiry in the humanities.

Introduction

In Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (2011), Tim Ingold defines anthropology as ‘a sustained and disciplined inquiry into the conditions and potentials of human life’ (Ingold, 2011 , p. 9). For Ingold, artistic practice plays a crucial part in this inquiry. He considers art not merely as a potential object of historical, sociological or ethnographic research, but also as a valuable form of anthropological inquiry itself, providing supplementary methods to understand what it is ‘to be human’.

In a similar vein, Mark Johnson’s The meaning of the body: aesthetics of human understanding (2007) offers a revaluation of art ‘as an essential mode of human engagement with and understanding of the world’ (Johnson, 2007 , p. 10). Johnson argues that art is a useful epistemological instrument because of its ability to intensify the ordinary experience of our environment. Images Footnote 1 are the expression of our on-going, complex relation with an inner and outer environment. In the process of making images of our environment, different bodily experiences, like affects, emotions, feelings and movements are mobilised in the creation of meaning. As Johnson argues, this happens in every process of meaning-making, which is always based on ‘deep-seated bodily sources of human meaning that go beyond the merely conceptual and propositional’ (Ibid., p. 11). The specificity of art simply resides in the fact that it actively engages with those non-conceptual, non-propositional forms of ‘making sense’ of our environment. Art is thus able to take into account (and to explore) many other different meaningful aspects of our human relationship with the environment and thus provide us with a supplementary form of knowledge. Hence Ingold’s remark in the introduction of Making: anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture (2013): ‘Could certain practices of art, for example, suggest new ways of doing anthropology? If there are similarities between the ways in which artists and anthropologists study the world, then could we not regard the artwork as a result of something like an anthropological study, rather than as an object of such study? […] could works of art not be regarded as forms of anthropology, albeit ‘written’ in non-verbal media?’ (Ingold, 2013 , p. 8, italics in original).

And yet we would hesitate to unreservedly answer yes to these rhetorical questions. For instance, it is true that one can consider the works of Francis Bacon as an anthropological study of violence and fear, or the works of John Cage as a study in indeterminacy and chance. But while they can indeed be seen as explorations of the ‘conditions and potentials of human life’, the artworks themselves do not make this knowledge explicit. What is lacking here is the logos of anthropology, logos in the sense of discourse, a line of reasoning. Therefore, while we agree with Ingold and Johnson, the problem remains how to explicate and communicate the knowledge that is contained within works of art, how to make it discursive ? How to articulate artistic practice as an alternative, yet valid form of scholarly research?

Here, we believe that a clear distinction between art and artistic research is necessary. The artistic imaginary is a reaction to the environment in which the artist finds himself: this reaction does not have to be conscious and deliberate. The artist has every right to shrug his shoulders when he is asked for the ‘meaning’ of his work, to provide a ‘discourse’. He can simply reply: ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I do not want to know’, as a refusal to engage with the step of articulating what his work might be exploring. Likewise, the beholder or the reader of a work of art does not need to learn from it to appreciate it. No doubt, he may have gained some understanding about ‘human existence’ after reading a novel or visiting an exhibition, but without the need to spell out this knowledge or to further explore it.

In contrast, artistic research as a specific, inquisitive mode of dealing with the environment requires an explicit articulation of what is at stake, the formulation of a specific problem that determines the focus of the research. ‘Problem’ is used here in the neutral, etymological sense of the word: something ‘thrown forward’, a ‘hindrance, obstacle’ (cf. probleima , Liddell-Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon). A body-in-an-environment finds something thrown before him or her, an issue that grabs the attention. A problem is something that urges us to explore a field of experiences, the ‘potentials of human life’ that are opened up by a work of art. It is often only retroactively, during a second, reflective phase of the artistic research, that a formulation of a problem becomes possible, by a selection of elements that strikes one as meaningful (again, in the sense Johnson defines meaningful, thus including bodily perceptions, movements, affects, feelings as meaningful elements of human understanding of reality). This process opens up, to borrow a term used by Aby Warburg, a ‘Denkraum’ (cf. Gombrich, 1986 , p. 224): it creates a critical distance from the environment, including the environment of the artwork itself: this ‘space for thought’ allows one to consciously explore a specific problem. Consciously here does not equal cerebral: the problem is explored not only in its intellectual, but also in its sensual and emotional, affective aspects. It is projected along different lines in this virtual Denkraum , lines that cross and influence each other: an existential line turns into a line of form and composition; a conceptual line merges into a narrative line, a technical line echoes an autobiographical line. There is no strict hierarchy in the different ‘emanations’ of a problem. These are just different lines contained within the work that interact with each other, and the problem can ‘move’ from one line to another, develop and transform itself along these lines, comparable perhaps to the way a melody develops itself when it is transposed to a different musical scale, a different musical instrument, or even to a different musical genre. But, however, abstract or technical one formulates a problem, following Johnson we argue that a problem is always a translation of a basic existential problem, emerging from a specific environment. We fully agree with Johnson when he argues that ‘philosophy becomes relevant to human life only by reconnecting with, and grounding itself in, bodily dimensions of human meaning and value. Philosophy needs a visceral connection to lived experience’ (Johnson, 2007 , p. 263). The same goes for artistic research. It too finds its relevance in the ‘visceral connection’ with a specific body, a specific situation.

Words are one way of disclosing this lived experience, but within the context of an artistic practice one can hardly ignore the potential for images to provide us with an equally valuable account. In fact, they may even prove most suited to establish the kind of space that comes close to this multi-threaded, embodied Denkraum . In order to illustrate this, we would like to present a case study, a short visual ‘essay’ (however, since the scope of four spreads offers only limited space, it is better to consider it as the image-equivalent of a short research note).

Case study: step by step reading of a visual essay

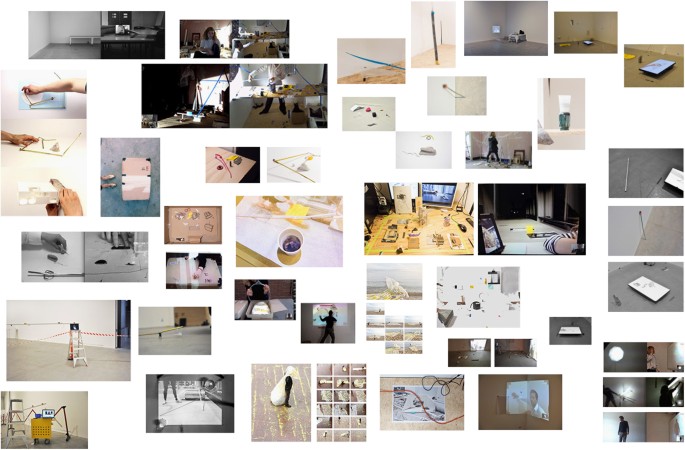

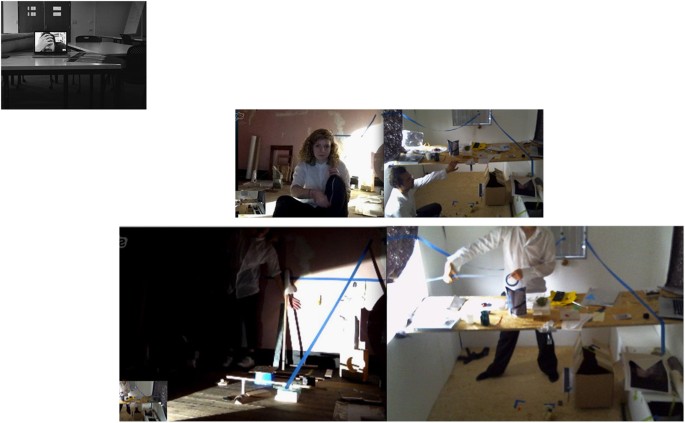

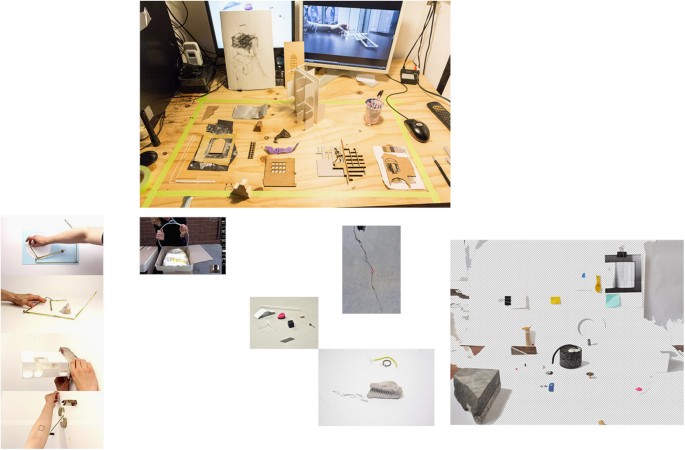

The images (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) form a short visual essay based on a collaborative artistic project 'Exercises of the man (v)' that Remco Roes and Alis Garlick realised for the Situation Symposium at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Melbourne in 2014. One of the conceptual premises of the project was the communication of two physical ‘sites’ through digital media. Roes—located in Belgium—would communicate with Garlick—in Australia—about an installation that was to be realised at the physical location of the exhibition in Melbourne. Their attempts to communicate (about) the site were conducted via e-mail messages, Skype-chats and video conversations. The focus of these conversations increasingly distanced itself from the empty exhibition space of the Design Hub and instead came to include coincidental spaces (and objects) that happened to be close at hand during the 3-month working period leading up to the exhibition. The focus of the project thus shifted from attempting to communicate a particular space towards attempting to communicate the more general experience of being in(side) a space. The project led to the production of a series of small in-situ installations, a large series of video’s and images, a book with a selection of these images as well as texts from the conversations, and the final exhibition in which artefacts that were found during the collaborative process were exhibited. A step by step reading of the visual argument contained within images of this project illustrates how a visual essay can function as a tool for disclosing/articulating/communicating the kind of embodied thinking that occurs within an artistic practice or practice-based research.

Figure 1 shows (albeit in reduced form) a field of photographs and video stills that summarises the project without emphasising any particular aspect. Each of the Figs. 2 – 5 isolate different parts of this same field in an attempt to construct/disclose a form of visual argument (that was already contained within the work). In the final part of this essay we will provide an illustration of how such visual sequences can be possibly ‘read’.

First image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Second image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Third image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Fourth image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Fifth image of the visual essay. Remco Roes and Alis Garlick, as copyright holders, permit the publication of this image under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Figure 1 is a remnant of the first step that was taken in the creation of the series of images: significant, meaningful elements in the work of art are brought together. At first, we quite simply start by looking at what is represented in the pictures, and how they are presented to us. This act of looking almost inevitably turns these images into a sequence, an argument. Conditioned by the dominant linearity of writing, including images (for instance in a comic book) one ‘reads’ the images from left to right, one goes from the first spread to the last. Just like one could say that a musical theme or a plot ‘develops’, the series of images seem to ‘develop’ the problem, gradually revealing its complexity. The dominance of this viewing code is not to be ignored, but is of course supplemented by the more ‘holistic’ nature of visual perception (cf. the notion of ‘Gestalt’ in the psychology of perception). So unlike a ‘classic’ argumentation, the discursive sequence is traversed by resonance, by non-linearity, by correspondences between elements both in a single image and between the images in their specific positioning within the essay. These correspondences reveal the synaesthetic nature of every process of meaning-making: ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual and potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences. In pragmatist lingo, the meaning of something is a matter of how it connects to what has gone before and what it entails for present or future experiences and actions’ (Johnson, 2007 , p. 265). The images operate in a similar way, by bringing together different actions, affects, feelings and perceptions into a complex constellation of meaningful elements that parallel each other and create a field of resonance. These connections occur between different elements that ‘disturb’ the logical linearity of the discourse, for instance by the repetition of a specific element (the blue/yellow opposition, or the repetition of a specific diagonal angle).

Confronted with these images, we are now able to delineate more precisely the problem they express. In a generic sense we could formulate it as follows: how to communicate with someone who does not share my existential space, but is nonetheless visually and acoustically present? What are the implications of the kind of technology that makes such communication possible, for the first time in human history? How does it influence our perception and experience of space, of materiality, of presence?

Artistic research into this problem explores the different ways of meaning-making that this new existential space offers, revealing the different conditions and possibilities of this new spatiality. But it has to be stressed that this exploration of the problem happens on different lines, ranging from the kinaesthetic perception to the emotional and affective response to these spaces and images. It would, thus, be wrong to reduce these experiences to a conceptual framework. In their actions, Roes and Garlick do not ‘make a statement’: they quite simply experiment with what their bodies can do in such a hybrid space, ‘wandering’ in this field of meaningful experiences, this Denkraum , that is ‘opened up’: which meaningful clusters of sensations, affects, feelings, spatial and kinaesthetic qualities emerge in such a specific existential space?

In what follows, we want to focus on some of these meaningful clusters. As such, these comments are not part of the visual essay itself. One could compare them to ‘reading remarks’, a short elaboration on what strikes one as relevant. These comments also do not try to ‘crack the code’ of the visual material, as if they were merely a visual and/or spatial rebus to be solved once and for all (‘ x stands for y’ ). They rather attempt to engage in a dialogue with the images, a dialogue that of course does not claim to be definitive or exhaustive.

The constellation itself generates a sense of ‘lacking’: we see that there are two characters intensely collaborating and interacting with each other, while never sharing the same space. They are performing, or watching the other perform: drawing a line (imaginary or physically), pulling, wrapping, unpacking, watching, framing, balancing. The small arrangements, constructions or compositions that are made as a result of these activities are all very fragile, shaky and their purpose remains unclear. Interaction with the other occurs only virtually, based on the manipulation of small objects and fragments, located in different places. One of the few materials that eventually gets physically exported to the other side, is a kind of large plastic cover. Again, one should not ‘read’ the picture of Roes with this plastic wrapped around his head as an expression, a ‘symbol’ of individual isolation, of being wrapped up in something. It is simply the experience of a head that disappears (as a head appears and disappears on a computer screen when it gets disconnected), and the experience of a head that is covered up: does it feel like choking, or does it provide a sense of shelter, protection?

A different ‘line’ operates simultaneously in the same image: that of a man standing on a double grid: the grid of the wet street tiles and an alternative, oblique grid of colourful yellow elements, a grid which is clearly temporal, as only the grid of the tiles will remain. These images are contrasted with the (obviously staged) moment when the plastic arrives at ‘the other side’: the claustrophobia is now replaced with the openness of the horizon, the presence of an open seascape: it gives a synaesthetic sense of a fresh breeze that seems lacking in the other images.

In this case, the contrast between the different spaces is very clear, but in other images we also see an effort to unite these different spaces. The problem can now be reformulated, as it moves to another line: how to demarcate a shared space that is both actual and virtual (with a ribbon, the positioning of a computer screen?), how to communicate with each other, not only with words or body language, but also with small artefacts, ‘meaningless’ junk? What is the ‘common ground’ on which to walk, to exchange things—connecting, lining up with the other? And here, the layout of the images (into a spread) adds an extra dimension to the original work of art. The relation between the different bodies does now not only take place in different spaces, but also in different fields of representation: there is the space of the spread, the photographed space and in the photographs, the other space opened up by the computer screen, and the interaction between these levels. We see this in the Fig. 3 where Garlick’s legs are projected on the floor, framed by two plastic beakers: her black legging echoing with the shadows of a chair or a tripod. This visual ‘rhyme’ within the image reveals how a virtual presence interferes with what is present.

The problem, which can be expressed in this fundamental opposition between presence/absence, also resonates with other recurring oppositions that rhythmically structure these images. The images are filled with blue/yellow elements: blue lines of tape, a blue plexi form, yellow traces of paint, yellow objects that are used in the video’s, but the two tones are also conjured up by the white balance difference between daylight and artificial light. The blue/yellow opposition, in turn, connects with other meaningful oppositions, like—obviously—male/female, or the same oppositional set of clothes: black trousers/white shirt, grey scale images versus full colour, or the shadow and the bright sunlight, which finds itself in another opposition with the cold electric light of a computer screen (this of course also refers to the different time zones, another crucial aspect of digital communication: we do not only not share the same place, we also do not share the same time).

Yet the images also invite us to explore certain formal and compositional elements that keep recurring. The second image, for example, emphasises the importance placed in the project upon the connecting of lines, literally of lining up. Within this image the direction and angle of these lines is ‘explained’ by the presence of the two bodies, the makers with their roles of tape in hand. But upon re-reading the other spreads through this lens of ‘connecting lines’ we see that this compositional element starts to attain its own visual logic. Where the lines in image 2 are literally used as devices to connect two (visual) realities, they free themselves from this restricted context in the other images and show us the influence of circumstance and context in allowing for the successful establishing of such a connection.

In Fig. 3 , for instance, we see a collection of lines that have been isolated from the direct context of live communication. The way two parts of a line are manually aligned (in the split-screens in image 2) mirrors the way the images find their position on the page. However, we also see how the visual grammar of these lines of tape is expanded upon: barrier tape that demarcates a working area meets the curve of a small copper fragment on the floor of an installation, a crack in the wall follows the slanted angle of an assembled object, existing marks on the floor—as well as lines in the architecture—come into play. The photographs widen the scale and angle at which the line operates: the line becomes a conceptual form that is no longer merely material tape but also an immaterial graphical element that explores its own argument.

Figure 4 provides us with a pivotal point in this respect: the cables of the mouse, computer and charger introduce a certain fluidity and uncontrolled motion. Similarly, the erratic markings on the paper show that an author is only ever partially in control. The cracked line in the floor is the first line that is created by a negative space, by an absence. This resonates with the black-stained edges of the laser-cut objects, laid out on the desktop. This fourth image thus seems to transform the manifestation of the line yet again; from a simple connecting device into an instrument that is able to cut out shapes, a path that delineates a cut, as opposed to establishing a connection. The circle held up in image 4 is a perfect circular cut. This resonates with the laser-cut objects we see just above it on the desk, but also with the virtual cuts made in the Photoshop image on the right. We can clearly see how a circular cut remains present on the characteristic grey-white chessboard that is virtual emptiness. It is evident that these elements have more than just an aesthetic function in a visual argumentation. They are an integral part of the meaning-making process. They ‘transpose’ on a different level, i.e., the formal and compositional level, the central problem of absence and presence: it is the graphic form of the ‘cut’, as well as the act of cutting itself, that turns one into the other.

Concluding remarks

As we have already argued, within the frame of this comment piece, the scope of the visual essay we present here is inevitably limited. It should be considered as a small exercise in a specific genre of thinking and communicating with images that requires further development. Nonetheless, we hope to have demonstrated the potentialities of the visual essay as a form of meaning-making that allows the articulation of a form of embodied knowledge that supplements other modes of inquiry in the humanities. In this particular case, it allows for the integration of other meaningful, embodied and existential aspects of digital communication, unlikely to be ‘detected’ as such by an (auto)ethnographic, psychological or sociological framework.

The visual essay is an invitation to other researchers in the arts to create their own kind of visual essays in order to address their own work of art or that of others: they can consider their artistic research as a valuable contribution to the exploration of human existence that lies at the core of the humanities. But perhaps it can also inspire scholars in more ‘classical’ domains to introduce artistic research methods to their toolbox, as a way of taking into account the non-conceptual, yet meaningful bodily aspects of human life and human artefacts, this ‘visceral connection to lived experience’, as Johnson puts it.

Obviously, a visual essay runs the risk of being ‘shot by both sides’: artists may scorn the loss of artistic autonomy and ‘exploitation’ of the work of art in the service of scholarship, while academic scholars may be wary of the lack of conceptual and methodological clarity inherent in these artistic forms of embodied, synaesthetic meaning. The visual essay is indeed a bastard genre, the unlawful love (or perhaps more honestly: love/hate) child of academia and the arts. But precisely this hybrid, impure nature of the visual essay allows it to explore unknown ‘conditions and potentials of human life’, precisely because it combines imagination and knowledge. And while this combination may sound like an oxymoron within a scientific, positivistic paradigm, it may in fact indicate the revival, in a new context, of a very ancient alliance. Or as Giorgio Agamben formulates it in Infancy and history: on the destruction of experience (2007 [1978]): ‘Nothing can convey the extent of the change that has taken place in the meaning of experience so much as the resulting reversal of the status of the imagination. For Antiquity, the imagination, which is now expunged from knowledge as ‘unreal’, was the supreme medium of knowledge. As the intermediary between the senses and the intellect, enabling, in phantasy, the union between the sensible form and the potential intellect, it occupies in ancient and medieval culture exactly the same role that our culture assigns to experience. Far from being something unreal, the mundus imaginabilis has its full reality between the mundus sensibilis and the mundus intellegibilis , and is, indeed, the condition of their communication—that is to say, of knowledge’ (Agamben, 2007 , p. 27, italics in original).

And it is precisely this exploration of the mundus imaginabilis that should inspire us to understand artistic research as a valuable form of scholarship in the humanities.

We consider images as a broad category consisting of artefacts of the imagination, the creation of expressive ‘forms’. Images are thus not limited to visual images. For instance, the imagery used in a poem or novel, metaphors in philosophical treatises (‘image-thoughts’), actual sculptures or the imaginary space created by a performance or installation can also be considered as images, just like soundscapes, scenography, architecture.

Agamben G (2007) Infancy and history: on the destruction of experience [trans. L. Heron]. Verso, London/New York, NY

Google Scholar

Garlick A, Roes R (2014) Exercises of the man (v): found dialogues whispered to drying paint. [installation]

Gombrich EH (1986) Aby Warburg: an intellectual biography. Phaidon, Oxford, [1970]

Ingold T (2011) Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge, London/New York, NY

Ingold T (2013) Making: anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. Routledge, London/New York, NY

Johnson M (2007) The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hasselt University, Martelarenlaan 42, 3500, Hasselt, Belgium

Remco Roes & Kris Pint

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Remco Roes .

Additional information

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher’s note : Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Roes, R., Pint, K. The visual essay and the place of artistic research in the humanities. Palgrave Commun 3 , 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0004-5

Download citation

Received : 29 June 2017

Accepted : 04 September 2017

Published : 31 October 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0004-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Visualizing Research: The Power of Pictures in Papers

As the use of technology and software grows in both teaching and research, so too does the importance of visual representation. The ability to effectively interpret data with pictures has become an essential tool for researchers from all fields. This article will explore how visuals are used as a powerful communication tool within academic papers, discussing what makes a successful visual representation while also considering some potential drawbacks. Moreover, this paper will look at different methods which can be employed when incorporating visuals into publications. It is expected that after reading this article academics will have gained greater understanding of ways they can more efficiently utilize images to present their findings.

1. Introduction: Visualizing Research and the Power of Pictures in Papers

2. examining how visualization enhances understanding of complex concepts, 3. different types of images used to enhance academic writing, 4. the pros and cons of including images in academic writing, 5. creative strategies for incorporating pictorial elements into paper content, 6. best practices for designing high quality graphics that convey meaningful information, 7. conclusion: leveraging the ability to “see” ideas through pictures.

We are living in a visual world. Many of us have grown accustomed to seeing visuals everywhere, from colorful advertisements and maps on our way to work to vibrant charts when researching a paper online. However, the power of visualizing research is something that can often be overlooked by researchers. From simplifying complex data points into tangible images or providing an overall context for further exploration, incorporating pictures within research papers has tremendous potential.

When considering how best to utilize visuals in academic writing, it’s important to understand which types may be most helpful. A few popular options include infographics , diagrams and tables.

- Infographics:

Visualization of complex concepts is a powerful tool for understanding and memory retention. It provides the opportunity to break down difficult topics into visuals that can be more easily absorbed, even by those who are unfamiliar with the concept or subject. Studies have shown that visual representation of material such as diagrams and charts improves comprehension and recall when compared to verbal descriptions.

When it comes to academic writing, there is often the need for illustrations that can help readers understand a point more clearly. Images are particularly useful in this regard as they allow authors to succinctly and effectively explain their argument. Generally speaking, three types of images are commonly used: charts, diagrams and photographs.

Charts come in many forms such as bar graphs or pie-charts. They provide a visual representation of numerical data which allows readers to quickly grasp patterns otherwise not immediately apparent from looking at raw figures alone. For example, a study by Lien et al., (2012) on Chinese foreign direct investment looked at trends across four countries over ten years and presented the results using two simple bar graphs.

The research paper concluded that “regional integration has been promoted through these outward investments” – an idea made easily understandable with the use of relevant graphics.

Diagrams also present complex concepts visually but differ from charts because they focus on how something works rather than pure numbers or statistics.. A good example can be seen in Peng’s article (2008), which explained how China had reformed its rural taxation system since 1978 using various government led initiatives including de-collectivization reforms . To complement his explanation he included an illustration detailing all key steps:

This provided clarity to what could have otherwise been quite dense text for some readers.

Pictures in Research Papers

- Images can capture complex concepts quickly.

- Well-selected images can help to illustrate and explain research findings.

The use of visual elements such as pictures, diagrams, or graphs is an increasingly popular option for researchers who want to improve the impact of their work. Images are effective at capturing readers’ attention while helping them better understand key points. However, there are several pros and cons associated with this approach that should be considered before including any visuals in your academic writing.

One major pro of using images is that they often have a powerful emotional impact on viewers which helps them engage more deeply with your paper’s content. In addition, when used judiciously they allow you to summarize complex ideas faster than words alone could ever do – making it easier for readers to gain an understanding without having wade through pages of text. Furthermore research studies show that papers featuring figures tend to get read more thoroughly compared those without (Skandari et al., 2017). This means that adding relevant illustrations may give you a competitive edge when vying for publications slots in well-regarded journals or other outlets. However along with these advantages also come certain challenges; most notably copyright issues as publishing unlicensed material constitutes copyright infringement if not properly attributed or credited correctly (Henderson & Morrissey 2019). Also excessive inclusion of visuals may make it difficult for busy reviewers to adequately assess each image given tight deadlines — thus leading the reader less inclined towards viewing your submissions favorably .To minimize these risks authors need ensure all graphics used adhere strictly within accepted standards concerning originality , accuracy and proper attribution where necessary.. Doing so will increase both the quality and clarity overall presentation–making sure no important details fall between the cracks due lack inadequate visual cues

Making an Impact with Images

Images have the power to capture our attention and trigger emotions. Incorporating them into a paper can help readers understand complex concepts, add visual interest, and make abstract ideas more concrete. To create effective visuals for papers:

- Choose images that are relevant.

- Avoid using stock photos unless they accurately depict what you’re trying to communicate.

- Include captions for context where appropriate.

When it comes to data-driven research studies, pictorial elements such as charts or graphs provide a way of demonstrating information quickly and clearly. They enable the reader to focus on specific patterns within large datasets in order to draw insights without having to wade through endless paragraphs of text. For example, a recent study by National Geographic found that Americans consume twice as much food today than in 1950. [1] . This finding was illustrated via an engaging line graph (see Figure 1) which made this statistic easier to grasp at first glance compared with reading about it alone:

References [1] National Geographic Society (2021). The Effects Of Increased Consumption On Resources & Health | nationalgeographic.org/education/. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/activity/the-effects-of-increased-consumption-onresources–health/ [2] Line graph image retrieved from Pixabay

Careful Color Selection and Contrast When designing high quality graphics, careful consideration should be given to the use of colors. Colors can carry meaning and elicit emotion from viewers, so it’s important to choose those that accurately represent the data being conveyed. It is also essential to ensure adequate contrast between elements on a graphic in order for them to remain distinguishable when viewed by an audience. Recent research conducted by Liu et al (2020) suggests that “by incorporating appropriate color contrasts, information will be more easily perceived” – indicating the importance of making sure colors are clearly contrasted within a graphic design piece.

The Power of Visual Representation Pictures have long been used to convey ideas more effectively than words alone. This is especially true when it comes to complex concepts such as scientific theories or abstract art – visual representation makes them easier for people to understand and comprehend. As technology advances, this capability has become even more useful in the classroom. With computers now able to generate detailed images that demonstrate how various phenomena work, students are better equipped with the tools necessary for a thorough understanding of their subject matter.

Researchers have discovered that humans can process pictures at a much faster rate than text-based information. In fact, some studies indicate that students learn quicker from an image compared to textual descriptions on its own. Moreover, using imagery during teaching can also help retain knowledge longer due to its ability to create emotional connections with content material which leads greater recall rates later on down the line.

A study conducted by [insert research paper] found significant increases in comprehension among participants who were exposed materials containing both visuals and text versus only verbal communication being utilized throughout their learning sessions; up 28% in total understanding was seen across those involved! Using these results one could infer from this data sets conclusion through sound reasoning: leveraging techniques involving visuals within educational contexts has proven beneficial effects upon cognitive capabilities overall amongst our modern day student populations thus far explored through experimentations methods.

This article has provided an insightful look into the power of visual representation in research papers. By providing compelling visuals, researchers can effectively communicate their results to a wider audience and maximize their impact. Visualizing data also enables readers to better interpret complex information and think critically about it. We have seen how visuals, such as graphs, tables, diagrams and maps offer powerful tools for showing relationships between variables or presenting findings with greater clarity than text alone could achieve. The inclusion of appropriate visuals in papers can therefore enhance reader engagement and understanding while driving further dialogue among peers on the subject matter at hand.

- Research Paper

- Book Report

- Book Review

- Movie Review

- Dissertation

- Thesis Proposal

- Research Proposal

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation Introduction

- Dissertation Review

- Dissertat. Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- Admission Essay

- Scholarship Essay

- Personal Statement

- Proofreading

- Speech Presentation

- Math Problem

- Article Critique

- Annotated Bibliography

- Reaction Paper

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Statistics Project

- Multiple Choice Questions

- Resume Writing

- Other (Not Listed)

Mental (Visual) Imagery (Research Paper Sample)

explain the use of mental imagery

Other Topics:

- Effects Stress Plays on the Body Description: Stress that is caused due to different factors that affect the body can be long-term or short-term... 10 pages/≈2750 words | 6 Sources | APA | Life Sciences | Research Paper |

- Incineration as an Energy Source Description: This paper talks about incineration as a method of producing energy. The incineration sector in the country is also analyzed in the paper... 9 pages/≈2475 words | 4 Sources | APA | Life Sciences | Research Paper |

- Psychology & Pedagogics Description: Describe how to critically evaluate research relevant to the practice of clinical mental health counseling... 2 pages/≈550 words | No Sources | APA | Life Sciences | Research Paper |

- Exchange your samples for free Unlocks.

- 24/7 Support

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Mental imagery can be advantageous, unnecessary and even clinically disruptive. With methodological constraints now overcome, research has shown that visual imagery involves a network of brain ...

Mental imagery is an under-explored field in clinical psychology research but presents a topic of potential interest and relevance across many clinical disorders, including social phobia ...

Mental imagery can be advantageous, unnecessary and even clinically disruptive. With methodological constraints now overcome, research has shown that visual imagery involves a network of brain areas from the frontal cortex to sensory areas, overlapping with the default mode network, and can function much like a weak version of afferent perception.

The use of imagery as a tool has been linked to many compound cognitive processes and imagery plays both symptomatic and mechanistic roles in neurological and mental disorders and treatments ...

Mental imagery research has weathered both disbelief of the phenomenon and inherent methodological limitations. Here we review recent behavioral, brain imaging, and clinical research that has reshaped our understanding of mental imagery. Research supports the claim that visual mental imagery is a depictive internal representation that functions ...

Almost every reviewer of mental imagery research starts with Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.), who stated that "Images belong to the rational soul in the manner of perceptions, and whenever it affirms or denies that something is good or bad, it pursues or avoids. ... Hatakeyama's research papers are available in Tohoku University's repository ...

More research is necessary to investigate this idea. In addition to the neural correlates of imagery vividness, this study also provides novel insights with regard to the overlap in neural representations of imagined and perceived stimuli. We reveal a large overlap between perception and imagery in visual cortex.

Our research presents an extended cognitive fingerprint of aphantasia and helps to clarify the role that visual imagery plays in wider consciousness and cognition. Visual imagery is a cognitive ...

Recent research suggests imagery is functionally equivalent to a weak form of visual perception. Here we report evidence across five independent experiments on adults that perception and imagery are supported by fundamentally different mechanisms: Whereas perceptual representations are largely formed via increases in excitatory activity, imagery representations are largely supported by ...

This paper assesses the effect of paraphrasing and visual imagery learning strategies on English language students' academic achievement in College of Education, Pankshin. This study employed the two groups, randomized subjects, post-test... more. Download. by League of Researchers.

In sum, the visual media analysis is the study of engagement and ordering in demarcated online spaces. Finally, in striving to display the results of the work, the notion of a metapicture is invoked as a technique that retains and frames the images under study so as to enable critical reflection of them.

Creativity is one of the most mysterious and controversial topic in Cognitive Psychology. Nevertheless, it is important at both individual, social and cultural level, being involved in problem solving, visual and verbal thinking, scientific invention and discovery, industrial design, works of art, dance, and music. In these last years Creativity has been also seen as a new way to improve the ...

See our list of visual communication research paper topics . In communication and media studies the term 'visual communication' did not come into use until after World War II and has been used most often to refer to 'pictures,' still and moving, rather than the broader concept of 'the visual.'. Studies of visual communication arose ...

1. Introduction. Models of human cognition propose that mental imagery exists for aiding thought predictions by linking them to emotions [1,2], allowing us to simulate and 'try out' future scenarios, as if we are experiencing them and their resulting emotional outcomes, aiding us in decision making (see [] for a review).Models of mental illness commonly identify mental imagery as a key ...

1. Imagery, Verbal Thought, And Perception. Much of the early history of imagery research was devoted to discriminating imagery from verbal thought, and characterizing some of its differences in functional information-processing terms. Allan Paivio (e.g., 1971) addressed these issues within the context of memory research.

The authors stress the importance of researchers engaging with theories (or approaches) to research ethics in their ethical decision making in order to protect the reputation and integrity of visual research. 1. Introduction. There has been a rapid growth and re-interest in visual methods in the last decade or so.

This research paper will provide a critical analysis of these arguments. This paper looks at mental imagery in its aid in human cognition, looking at the principles behind it. The paper also explores the theory behind the mental imagery and visual imagery which are always believed to be functioning as one.

For this topic, we expect that creating a visual rather than verbal explanation will aid students of both high and low spatial abilities. Visual explanations demand completeness; they were predicted to include more information than verbal explanations, particularly structural information. ... All paper materials were typed on 8.5 × 11 in ...

Here, we set out to defend the visual essay as a useful tool to explore the non-conceptual, yet meaningful bodily aspects of human culture, both in the still developing field of artistic research ...

Making an Impact with Images. Images have the power to capture our attention and trigger emotions. Incorporating them into a paper can help readers understand complex concepts, add visual interest, and make abstract ideas more concrete. To create effective visuals for papers: Choose images that are relevant.

The criteria selection helps to limit the broad topic to direct relevance for the research questions. The language is selected as English as it is the primary publication language for scientific articles. ... It comprises research articles, conference papers, and students' dissertations. Other databases like Springer, Science Direct, and Taylor ...

Topic: Mental (Visual) Imagery (Research Paper Sample) Instructions: explain the use of mental imagery. source.. Content: ... Visual imagery can be used to explain the construction of visual images and the perception of real objects or events that are actually perceived. Several of the same kinds of interior processes used in psychological ...

The topics involved in VH can be described by the keywords extracted from each article in the dataset; however, new insights into this field should be determined. The burst patterns of keywords reveal research hotspots in the field of VH because a burst of a keyword is a sharp increase of the keyword that is likely to have a great influence ...