Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Google Classroom - Creating Assignments and Materials

Google classroom -, creating assignments and materials, google classroom creating assignments and materials.

Google Classroom: Creating Assignments and Materials

Lesson 2: creating assignments and materials.

/en/google-classroom/getting-started-with-google-classroom/content/

Creating assignments and materials

Google Classroom gives you the ability to create and assign work for your students, all without having to print anything. Questions , essays , worksheets , and readings can all be distributed online and made easily available to your class. If you haven't created a class already, check out our Getting Started with Google Classroom lesson.

Watch the video below to learn more about creating assignments and materials in Google Classroom.

Creating an assignment

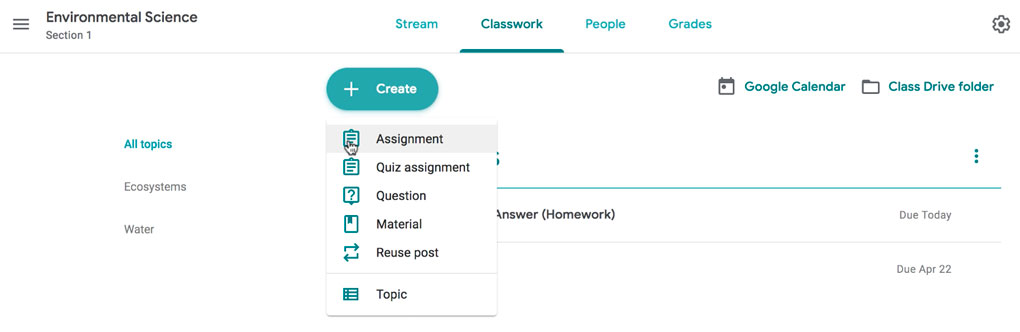

Whenever you want to create new assignments, questions, or material, you'll need to navigate to the Classwork tab.

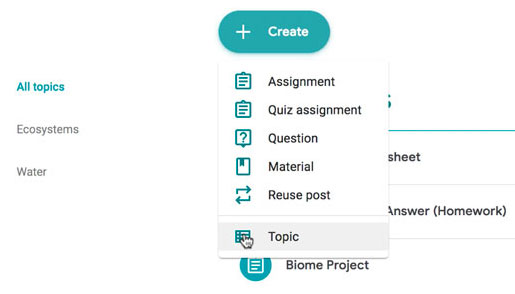

In this tab, you can create assignments and view all current and past assignments. To create an assignment, click the Create button, then select Assignment . You can also select Question if you'd like to pose a single question to your students, or Material if you simply want to post a reading, visual, or other supplementary material.

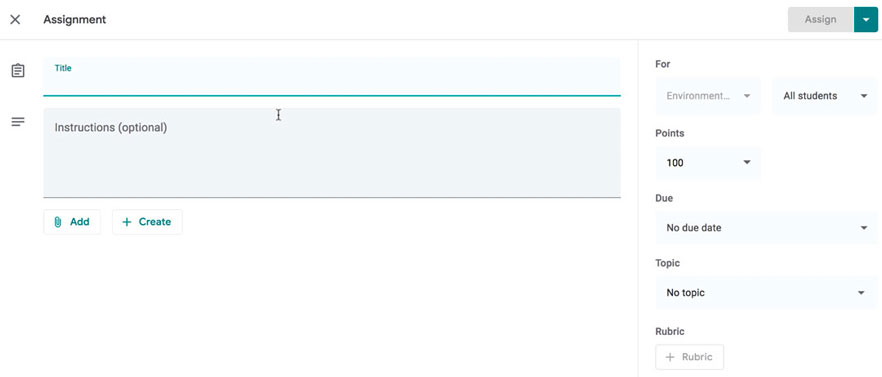

This will bring up the Assignment form. Google Classroom offers considerable flexibility and options when creating assignments.

Click the buttons in the interactive below to become familiar with the Assignment form.

This is where you'll type the title of the assignment you're creating.

Instructions

If you'd like to include instructions with your assignment, you can type them here.

Here, you can decide how many points an assignment is worth by typing the number in the form. You can also click the drop-down arrow to select Ungraded if you don't want to grade an assignment.

You can select a due date for an assignment by clicking this arrow and selecting a date from the calendar that appears. Students will have until then to submit their work.

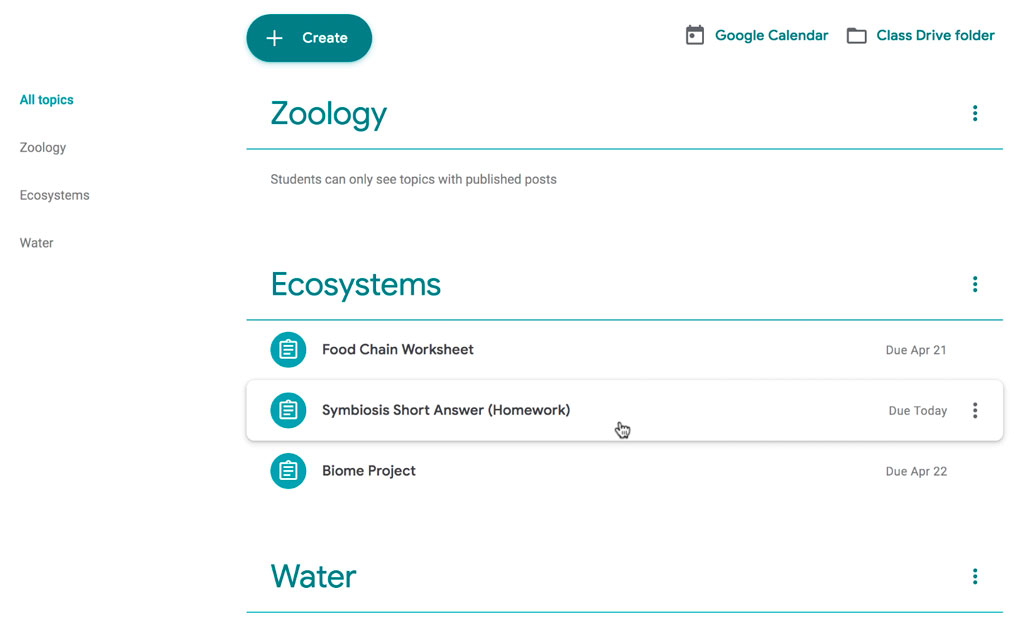

In Google Classroom, you can sort your assignments and materials into topics. This menu allows you to select an existing topic or create a new one to place an assignment under.

Attachments

You can attach files from your computer , files from Google Drive , URLs , and YouTube videos to your assignments.

Google Classroom gives you the option of sending assignments to all students or a select number .

Once you're happy with the assignment you've created, click Assign . The drop-down menu also gives you the option to Schedule an assignment if you'd like it to post it at a later date.

You can attach a rubric to help students know your expectations for the assignment and to give them feedback.

Once you've completed the form and clicked Assign , your students will receive an email notification letting them know about the assignment.

Google Classroom takes all of your assignments and automatically adds them to your Google Calendar. From the Classwork tab, you can click Google Calendar to pull this up and get a better overall view of the timeline for your assignments' due dates.

Using Google Docs with assignments

When creating an assignment, there may often be times when you want to attach a document from Google Docs. These can be helpful when providing lengthy instructions, study guides, and other material.

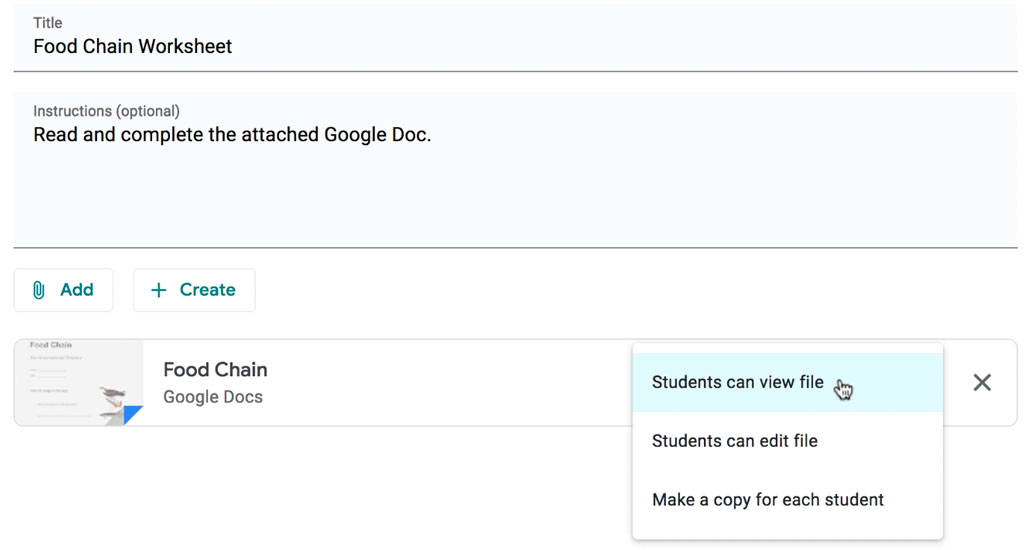

When attaching these types of files, you'll want to make sure to choose the correct setting for how your students can interact with it . After attaching one to an assignment, you'll find a drop-down menu with three options.

Let's take a look at when you might want to use each of these:

- Students can view file : Use this option if the file is simply something you want your students to view but not make any changes to.

- Students can edit file : This option can be helpful if you're providing a document you want your students to collaborate on or fill out collectively.

- Make a copy for each student : If you're creating a worksheet or document that you want each student to complete individually, this option will create a separate copy of the same document for every student.

Using topics

On the Classwork tab, you can use topics to sort and group your assignments and material. To create a topic, click the Create button, then select Topic .

Topics can be helpful for organizing your content into the various units you teach throughout the year. You could also use it to separate your content by type , splitting it into homework, classwork, readings, and other topic areas.

In our next lesson , we'll explore how to create quizzes and worksheets with Google Forms, further expanding how you can use Google Classroom with your students.

/en/google-classroom/using-forms-with-google-classroom/content/

- Google Classroom

- Google Workspace Admin

- Google Cloud

Getting started with Assignments

Learn how to use Assignments to easily distribute, analyze, and grade student work – all while using the collaborative power of Google Workspace.

Find tips and tricks from teachers like you

Get the most out of Assignments with these simple tips from fellow teachers and educators.

Discover training lessons and related resources to accelerate your learning

Error loading content :( Please try again later

- {[ item.label ]}

{[ collectionContentCtrl.activeTopic.label ]} All resources ({[ collectionContentCtrl.totalItemsCount ]})

{[ item.eyebrow ]}

{[ item.name ]}

{[ item.description ]}

{[ item.featured_text ]}

No results matching your selection :( Clear filters to show all results

Dive into Assignments

Already have Google Workspace for Education? Sign in to Assignments to explore the features and capabilities.

Get support from our help center

See how assignments can help you easily distribute, analyze, and grade student work, you're now viewing content for united states..

For content more relevant to your region, choose a different location:

Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center

- Teaching Resources

- TLPDC Teaching Resources

How Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?

Prepared by allison boye, ph.d. teaching, learning, and professional development center.

Assessment is a necessary part of the teaching and learning process, helping us measure whether our students have really learned what we want them to learn. While exams and quizzes are certainly favorite and useful methods of assessment, out of class assignments (written or otherwise) can offer similar insights into our students' learning. And just as creating a reliable test takes thoughtfulness and skill, so does creating meaningful and effective assignments. Undoubtedly, many instructors have been on the receiving end of disappointing student work, left wondering what went wrong… and often, those problems can be remedied in the future by some simple fine-tuning of the original assignment. This paper will take a look at some important elements to consider when developing assignments, and offer some easy approaches to creating a valuable assessment experience for all involved.

First Things First…

Before assigning any major tasks to students, it is imperative that you first define a few things for yourself as the instructor:

- Your goals for the assignment . Why are you assigning this project, and what do you hope your students will gain from completing it? What knowledge, skills, and abilities do you aim to measure with this assignment? Creating assignments is a major part of overall course design, and every project you assign should clearly align with your goals for the course in general. For instance, if you want your students to demonstrate critical thinking, perhaps asking them to simply summarize an article is not the best match for that goal; a more appropriate option might be to ask for an analysis of a controversial issue in the discipline. Ultimately, the connection between the assignment and its purpose should be clear to both you and your students to ensure that it is fulfilling the desired goals and doesn't seem like “busy work.” For some ideas about what kinds of assignments match certain learning goals, take a look at this page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons.

- Have they experienced “socialization” in the culture of your discipline (Flaxman, 2005)? Are they familiar with any conventions you might want them to know? In other words, do they know the “language” of your discipline, generally accepted style guidelines, or research protocols?

- Do they know how to conduct research? Do they know the proper style format, documentation style, acceptable resources, etc.? Do they know how to use the library (Fitzpatrick, 1989) or evaluate resources?

- What kinds of writing or work have they previously engaged in? For instance, have they completed long, formal writing assignments or research projects before? Have they ever engaged in analysis, reflection, or argumentation? Have they completed group assignments before? Do they know how to write a literature review or scientific report?

In his book Engaging Ideas (1996), John Bean provides a great list of questions to help instructors focus on their main teaching goals when creating an assignment (p.78):

1. What are the main units/modules in my course?

2. What are my main learning objectives for each module and for the course?

3. What thinking skills am I trying to develop within each unit and throughout the course?

4. What are the most difficult aspects of my course for students?

5. If I could change my students' study habits, what would I most like to change?

6. What difference do I want my course to make in my students' lives?

What your students need to know

Once you have determined your own goals for the assignment and the levels of your students, you can begin creating your assignment. However, when introducing your assignment to your students, there are several things you will need to clearly outline for them in order to ensure the most successful assignments possible.

- First, you will need to articulate the purpose of the assignment . Even though you know why the assignment is important and what it is meant to accomplish, you cannot assume that your students will intuit that purpose. Your students will appreciate an understanding of how the assignment fits into the larger goals of the course and what they will learn from the process (Hass & Osborn, 2007). Being transparent with your students and explaining why you are asking them to complete a given assignment can ultimately help motivate them to complete the assignment more thoughtfully.

- If you are asking your students to complete a writing assignment, you should define for them the “rhetorical or cognitive mode/s” you want them to employ in their writing (Flaxman, 2005). In other words, use precise verbs that communicate whether you are asking them to analyze, argue, describe, inform, etc. (Verbs like “explore” or “comment on” can be too vague and cause confusion.) Provide them with a specific task to complete, such as a problem to solve, a question to answer, or an argument to support. For those who want assignments to lead to top-down, thesis-driven writing, John Bean (1996) suggests presenting a proposition that students must defend or refute, or a problem that demands a thesis answer.

- It is also a good idea to define the audience you want your students to address with their assignment, if possible – especially with writing assignments. Otherwise, students will address only the instructor, often assuming little requires explanation or development (Hedengren, 2004; MIT, 1999). Further, asking students to address the instructor, who typically knows more about the topic than the student, places the student in an unnatural rhetorical position. Instead, you might consider asking your students to prepare their assignments for alternative audiences such as other students who missed last week's classes, a group that opposes their position, or people reading a popular magazine or newspaper. In fact, a study by Bean (1996) indicated the students often appreciate and enjoy assignments that vary elements such as audience or rhetorical context, so don't be afraid to get creative!

- Obviously, you will also need to articulate clearly the logistics or “business aspects” of the assignment . In other words, be explicit with your students about required elements such as the format, length, documentation style, writing style (formal or informal?), and deadlines. One caveat, however: do not allow the logistics of the paper take precedence over the content in your assignment description; if you spend all of your time describing these things, students might suspect that is all you care about in their execution of the assignment.

- Finally, you should clarify your evaluation criteria for the assignment. What elements of content are most important? Will you grade holistically or weight features separately? How much weight will be given to individual elements, etc? Another precaution to take when defining requirements for your students is to take care that your instructions and rubric also do not overshadow the content; prescribing too rigidly each element of an assignment can limit students' freedom to explore and discover. According to Beth Finch Hedengren, “A good assignment provides the purpose and guidelines… without dictating exactly what to say” (2004, p. 27). If you decide to utilize a grading rubric, be sure to provide that to the students along with the assignment description, prior to their completion of the assignment.

A great way to get students engaged with an assignment and build buy-in is to encourage their collaboration on its design and/or on the grading criteria (Hudd, 2003). In his article “Conducting Writing Assignments,” Richard Leahy (2002) offers a few ideas for building in said collaboration:

• Ask the students to develop the grading scale themselves from scratch, starting with choosing the categories.

• Set the grading categories yourself, but ask the students to help write the descriptions.

• Draft the complete grading scale yourself, then give it to your students for review and suggestions.

A Few Do's and Don'ts…

Determining your goals for the assignment and its essential logistics is a good start to creating an effective assignment. However, there are a few more simple factors to consider in your final design. First, here are a few things you should do :

- Do provide detail in your assignment description . Research has shown that students frequently prefer some guiding constraints when completing assignments (Bean, 1996), and that more detail (within reason) can lead to more successful student responses. One idea is to provide students with physical assignment handouts , in addition to or instead of a simple description in a syllabus. This can meet the needs of concrete learners and give them something tangible to refer to. Likewise, it is often beneficial to make explicit for students the process or steps necessary to complete an assignment, given that students – especially younger ones – might need guidance in planning and time management (MIT, 1999).

- Do use open-ended questions. The most effective and challenging assignments focus on questions that lead students to thinking and explaining, rather than simple yes or no answers, whether explicitly part of the assignment description or in the brainstorming heuristics (Gardner, 2005).

- Do direct students to appropriate available resources . Giving students pointers about other venues for assistance can help them get started on the right track independently. These kinds of suggestions might include information about campus resources such as the University Writing Center or discipline-specific librarians, suggesting specific journals or books, or even sections of their textbook, or providing them with lists of research ideas or links to acceptable websites.

- Do consider providing models – both successful and unsuccessful models (Miller, 2007). These models could be provided by past students, or models you have created yourself. You could even ask students to evaluate the models themselves using the determined evaluation criteria, helping them to visualize the final product, think critically about how to complete the assignment, and ideally, recognize success in their own work.

- Do consider including a way for students to make the assignment their own. In their study, Hass and Osborn (2007) confirmed the importance of personal engagement for students when completing an assignment. Indeed, students will be more engaged in an assignment if it is personally meaningful, practical, or purposeful beyond the classroom. You might think of ways to encourage students to tap into their own experiences or curiosities, to solve or explore a real problem, or connect to the larger community. Offering variety in assignment selection can also help students feel more individualized, creative, and in control.

- If your assignment is substantial or long, do consider sequencing it. Far too often, assignments are given as one-shot final products that receive grades at the end of the semester, eternally abandoned by the student. By sequencing a large assignment, or essentially breaking it down into a systematic approach consisting of interconnected smaller elements (such as a project proposal, an annotated bibliography, or a rough draft, or a series of mini-assignments related to the longer assignment), you can encourage thoughtfulness, complexity, and thoroughness in your students, as well as emphasize process over final product.

Next are a few elements to avoid in your assignments:

- Do not ask too many questions in your assignment. In an effort to challenge students, instructors often err in the other direction, asking more questions than students can reasonably address in a single assignment without losing focus. Offering an overly specific “checklist” prompt often leads to externally organized papers, in which inexperienced students “slavishly follow the checklist instead of integrating their ideas into more organically-discovered structure” (Flaxman, 2005).

- Do not expect or suggest that there is an “ideal” response to the assignment. A common error for instructors is to dictate content of an assignment too rigidly, or to imply that there is a single correct response or a specific conclusion to reach, either explicitly or implicitly (Flaxman, 2005). Undoubtedly, students do not appreciate feeling as if they must read an instructor's mind to complete an assignment successfully, or that their own ideas have nowhere to go, and can lose motivation as a result. Similarly, avoid assignments that simply ask for regurgitation (Miller, 2007). Again, the best assignments invite students to engage in critical thinking, not just reproduce lectures or readings.

- Do not provide vague or confusing commands . Do students know what you mean when they are asked to “examine” or “discuss” a topic? Return to what you determined about your students' experiences and levels to help you decide what directions will make the most sense to them and what will require more explanation or guidance, and avoid verbiage that might confound them.

- Do not impose impossible time restraints or require the use of insufficient resources for completion of the assignment. For instance, if you are asking all of your students to use the same resource, ensure that there are enough copies available for all students to access – or at least put one copy on reserve in the library. Likewise, make sure that you are providing your students with ample time to locate resources and effectively complete the assignment (Fitzpatrick, 1989).

The assignments we give to students don't simply have to be research papers or reports. There are many options for effective yet creative ways to assess your students' learning! Here are just a few:

Journals, Posters, Portfolios, Letters, Brochures, Management plans, Editorials, Instruction Manuals, Imitations of a text, Case studies, Debates, News release, Dialogues, Videos, Collages, Plays, Power Point presentations

Ultimately, the success of student responses to an assignment often rests on the instructor's deliberate design of the assignment. By being purposeful and thoughtful from the beginning, you can ensure that your assignments will not only serve as effective assessment methods, but also engage and delight your students. If you would like further help in constructing or revising an assignment, the Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center is glad to offer individual consultations. In addition, look into some of the resources provided below.

Online Resources

“Creating Effective Assignments” http://www.unh.edu/teaching-excellence/resources/Assignments.htm This site, from the University of New Hampshire's Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, provides a brief overview of effective assignment design, with a focus on determining and communicating goals and expectations.

Gardner, T. (2005, June 12). Ten Tips for Designing Writing Assignments. Traci's Lists of Ten. http://www.tengrrl.com/tens/034.shtml This is a brief yet useful list of tips for assignment design, prepared by a writing teacher and curriculum developer for the National Council of Teachers of English . The website will also link you to several other lists of “ten tips” related to literacy pedagogy.

“How to Create Effective Assignments for College Students.” http:// tilt.colostate.edu/retreat/2011/zimmerman.pdf This PDF is a simplified bulleted list, prepared by Dr. Toni Zimmerman from Colorado State University, offering some helpful ideas for coming up with creative assignments.

“Learner-Centered Assessment” http://cte.uwaterloo.ca/teaching_resources/tips/learner_centered_assessment.html From the Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, this is a short list of suggestions for the process of designing an assessment with your students' interests in mind. “Matching Learning Goals to Assignment Types.” http://teachingcommons.depaul.edu/How_to/design_assignments/assignments_learning_goals.html This is a great page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons, providing a chart that helps instructors match assignments with learning goals.

Additional References Bean, J.C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fitzpatrick, R. (1989). Research and writing assignments that reduce fear lead to better papers and more confident students. Writing Across the Curriculum , 3.2, pp. 15 – 24.

Flaxman, R. (2005). Creating meaningful writing assignments. The Teaching Exchange . Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008 from http://www.brown.edu/Administration/Sheridan_Center/pubs/teachingExchange/jan2005/01_flaxman.pdf

Hass, M. & Osborn, J. (2007, August 13). An emic view of student writing and the writing process. Across the Disciplines, 4.

Hedengren, B.F. (2004). A TA's guide to teaching writing in all disciplines . Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Hudd, S. S. (2003, April). Syllabus under construction: Involving students in the creation of class assignments. Teaching Sociology , 31, pp. 195 – 202.

Leahy, R. (2002). Conducting writing assignments. College Teaching , 50.2, pp. 50 – 54.

Miller, H. (2007). Designing effective writing assignments. Teaching with writing . University of Minnesota Center for Writing. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008, from http://writing.umn.edu/tww/assignments/designing.html

MIT Online Writing and Communication Center (1999). Creating Writing Assignments. Retrieved January 9, 2008 from http://web.mit.edu/writing/Faculty/createeffective.html .

Contact TTU

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

How to Write an Effective Assignment

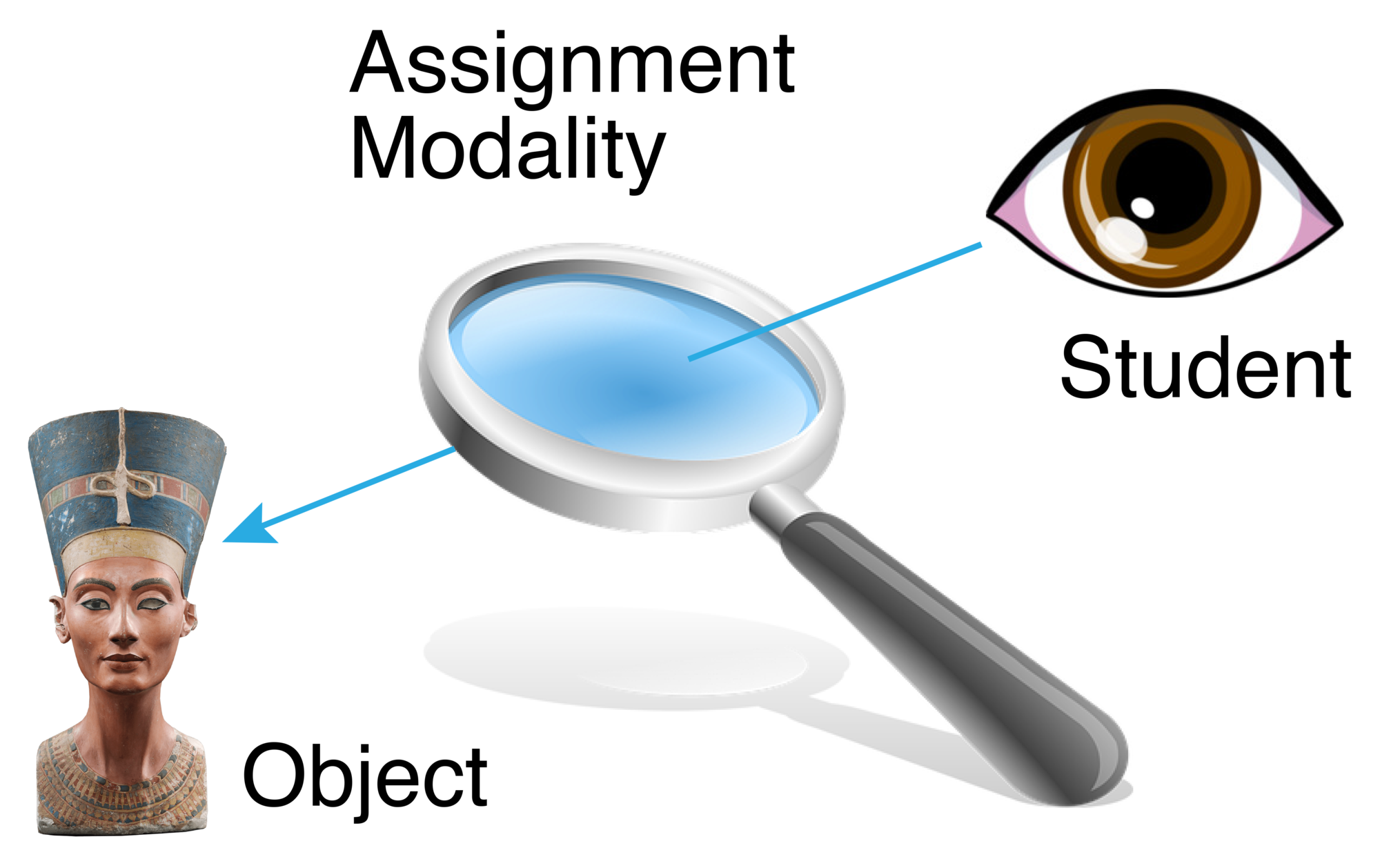

At their base, all assignment prompts function a bit like a magnifying glass—they allow a student to isolate, focus on, inspect, and interact with some portion of your course material through a fixed lens of your choosing.

The Key Components of an Effective Assignment Prompt

All assignments, from ungraded formative response papers all the way up to a capstone assignment, should include the following components to ensure that students and teachers understand not only the learning objective of the assignment, but also the discrete steps which they will need to follow in order to complete it successfully:

- Preamble. This situates the assignment within the context of the course, reminding students of what they have been working on in anticipation of the assignment and how that work has prepared them to succeed at it.

- Justification and Purpose. This explains why the particular type or genre of assignment you’ve chosen (e.g., lab report, policy memo, problem set, or personal reflection) is the best way for you and your students to measure how well they’ve met the learning objectives associated with this segment of the course.

- Mission. This explains the assignment in broad brush strokes, giving students a general sense of the project you are setting before them. It often gives students guidance on the evidence or data they should be working with, as well as helping them imagine the audience their work should be aimed at.

- Tasks. This outlines what students are supposed to do at a more granular level: for example, how to start, where to look, how to ask for help, etc. If written well, this part of the assignment prompt ought to function as a kind of "process" rubric for students, helping them to decide for themselves whether they are completing the assignment successfully.

- Submission format. This tells students, in appropriate detail, which stylistic conventions they should observe and how to submit their work. For example, should the assignment be a five-page paper written in APA format and saved as a .docx file? Should it be uploaded to the course website? Is it due by Tuesday at 5:00pm?

For illustrations of these five components in action, visit our gallery of annotated assignment prompts .

For advice about creative assignments (e.g. podcasts, film projects, visual and performing art projects, etc.), visit our Guidance on Non-Traditional Forms of Assessment .

For specific advice on different genres of assignment, click below:

Response Papers

Problem sets, source analyses, final exams, concept maps, research papers, oral presentations, poster presentations.

- Learner-Centered Design

- Putting Evidence at the Center

- What Should Students Learn?

- Start with the Capstone

- Gallery of Annotated Assignment Prompts

- Scaffolding: Using Frequency and Sequencing Intentionally

- Curating Content: The Virtue of Modules

- Syllabus Design

- Catalogue Materials

- Making a Course Presentation Video

- Teaching Teams

- In the Classroom

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating assignments.

Here are some general suggestions and questions to consider when creating assignments. There are also many other resources in print and on the web that provide examples of interesting, discipline-specific assignment ideas.

Consider your learning objectives.

What do you want students to learn in your course? What could they do that would show you that they have learned it? To determine assignments that truly serve your course objectives, it is useful to write out your objectives in this form: I want my students to be able to ____. Use active, measurable verbs as you complete that sentence (e.g., compare theories, discuss ramifications, recommend strategies), and your learning objectives will point you towards suitable assignments.

Design assignments that are interesting and challenging.

This is the fun side of assignment design. Consider how to focus students’ thinking in ways that are creative, challenging, and motivating. Think beyond the conventional assignment type! For example, one American historian requires students to write diary entries for a hypothetical Nebraska farmwoman in the 1890s. By specifying that students’ diary entries must demonstrate the breadth of their historical knowledge (e.g., gender, economics, technology, diet, family structure), the instructor gets students to exercise their imaginations while also accomplishing the learning objectives of the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1989, p. 25).

Double-check alignment.

After creating your assignments, go back to your learning objectives and make sure there is still a good match between what you want students to learn and what you are asking them to do. If you find a mismatch, you will need to adjust either the assignments or the learning objectives. For instance, if your goal is for students to be able to analyze and evaluate texts, but your assignments only ask them to summarize texts, you would need to add an analytical and evaluative dimension to some assignments or rethink your learning objectives.

Name assignments accurately.

Students can be misled by assignments that are named inappropriately. For example, if you want students to analyze a product’s strengths and weaknesses but you call the assignment a “product description,” students may focus all their energies on the descriptive, not the critical, elements of the task. Thus, it is important to ensure that the titles of your assignments communicate their intention accurately to students.

Consider sequencing.

Think about how to order your assignments so that they build skills in a logical sequence. Ideally, assignments that require the most synthesis of skills and knowledge should come later in the semester, preceded by smaller assignments that build these skills incrementally. For example, if an instructor’s final assignment is a research project that requires students to evaluate a technological solution to an environmental problem, earlier assignments should reinforce component skills, including the ability to identify and discuss key environmental issues, apply evaluative criteria, and find appropriate research sources.

Think about scheduling.

Consider your intended assignments in relation to the academic calendar and decide how they can be reasonably spaced throughout the semester, taking into account holidays and key campus events. Consider how long it will take students to complete all parts of the assignment (e.g., planning, library research, reading, coordinating groups, writing, integrating the contributions of team members, developing a presentation), and be sure to allow sufficient time between assignments.

Check feasibility.

Is the workload you have in mind reasonable for your students? Is the grading burden manageable for you? Sometimes there are ways to reduce workload (whether for you or for students) without compromising learning objectives. For example, if a primary objective in assigning a project is for students to identify an interesting engineering problem and do some preliminary research on it, it might be reasonable to require students to submit a project proposal and annotated bibliography rather than a fully developed report. If your learning objectives are clear, you will see where corners can be cut without sacrificing educational quality.

Articulate the task description clearly.

If an assignment is vague, students may interpret it any number of ways – and not necessarily how you intended. Thus, it is critical to clearly and unambiguously identify the task students are to do (e.g., design a website to help high school students locate environmental resources, create an annotated bibliography of readings on apartheid). It can be helpful to differentiate the central task (what students are supposed to produce) from other advice and information you provide in your assignment description.

Establish clear performance criteria.

Different instructors apply different criteria when grading student work, so it’s important that you clearly articulate to students what your criteria are. To do so, think about the best student work you have seen on similar tasks and try to identify the specific characteristics that made it excellent, such as clarity of thought, originality, logical organization, or use of a wide range of sources. Then identify the characteristics of the worst student work you have seen, such as shaky evidence, weak organizational structure, or lack of focus. Identifying these characteristics can help you consciously articulate the criteria you already apply. It is important to communicate these criteria to students, whether in your assignment description or as a separate rubric or scoring guide . Clearly articulated performance criteria can prevent unnecessary confusion about your expectations while also setting a high standard for students to meet.

Specify the intended audience.

Students make assumptions about the audience they are addressing in papers and presentations, which influences how they pitch their message. For example, students may assume that, since the instructor is their primary audience, they do not need to define discipline-specific terms or concepts. These assumptions may not match the instructor’s expectations. Thus, it is important on assignments to specify the intended audience http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm (e.g., undergraduates with no biology background, a potential funder who does not know engineering).

Specify the purpose of the assignment.

If students are unclear about the goals or purpose of the assignment, they may make unnecessary mistakes. For example, if students believe an assignment is focused on summarizing research as opposed to evaluating it, they may seriously miscalculate the task and put their energies in the wrong place. The same is true they think the goal of an economics problem set is to find the correct answer, rather than demonstrate a clear chain of economic reasoning. Consequently, it is important to make your objectives for the assignment clear to students.

Specify the parameters.

If you have specific parameters in mind for the assignment (e.g., length, size, formatting, citation conventions) you should be sure to specify them in your assignment description. Otherwise, students may misapply conventions and formats they learned in other courses that are not appropriate for yours.

A Checklist for Designing Assignments

Here is a set of questions you can ask yourself when creating an assignment.

- Provided a written description of the assignment (in the syllabus or in a separate document)?

- Specified the purpose of the assignment?

- Indicated the intended audience?

- Articulated the instructions in precise and unambiguous language?

- Provided information about the appropriate format and presentation (e.g., page length, typed, cover sheet, bibliography)?

- Indicated special instructions, such as a particular citation style or headings?

- Specified the due date and the consequences for missing it?

- Articulated performance criteria clearly?

- Indicated the assignment’s point value or percentage of the course grade?

- Provided students (where appropriate) with models or samples?

Adapted from the WAC Clearinghouse at http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm .

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

- Our Mission

Teaching Students to Manage Their Digital Assignments

Predictable routines can teach students how to use organizational tools and help them develop their executive function skills.

You just wrapped up an invigorating conversation with your 10th-grade students. They contributed brilliant ideas, and you’re looking forward to reading the written reflections you assigned for homework. But when you log into Google Classroom the next day to grade their work, you find that nearly half of your students didn’t submit the assignment. Only two-thirds of them even opened the document.

Sound familiar?

So many students who are engaged in real-world learning activities struggle to complete assignments in the digital world. Digital work is often out of sight and out of mind the moment they leave our classrooms. It can cause teachers and parents to wonder if being organized is even possible in our tech-focused society.

1-to-1 Devices are Permanent Fixtures in Today’s Classroom

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic pushed most schools into a virtual teaching model, students spent much of their instructional time on a device. A 2019 study out of Arlington Public Schools found that middle school students spent 47 percent of their time and high school students spent 68 percent of their time on a device. Findings from the study suggest that devices are frequently used for “reference and research, presentations and projects, and feedback and assessment.”

By the return to in-person learning, 90 percent of students had access to a one-to-one device for school, and it’s evident that technology in the classroom (and workplace) is here to stay.

Teaching Digital Organization Skills is Key

Although they have access to a myriad of digital organization tools ( myHomework , Evernote , Google Keep , and Coggle , to name a few), students may still struggle to organize their assignments and complete them from start to submission. We often assume that students can transfer organizational skills from the real world to the digital world, and we often ask them to quickly and seamlessly transition from hard-copy work (reading a chapter in a novel, completing a science experiment) to digital work, such as writing a reflection in Google Docs and submitting it to a learning management system (LMS).

Digital files are perceivable to the human brain, but they aren’t tangible in the same way that binders, notebooks, and folders are. And while an LMS may aid students’ access to information, it doesn’t do the heavy lifting of organizing information and prioritizing tasks. These actions are highly demanding cognitive skills that students can be taught and practice in the digital world—even if students have already perfected them in the analog world.

Teachers can prioritize strategic, direct instruction of organizational and other executive functioning skills for a tech-focused world.

Streamline Your Classroom Resources

The first step in helping students organize digital work is to organize your classroom resources on the back end. In coordination with your department, grade level, or district, choose one LMS and three to four instructional resources, and stick with them for the entire year. For example, you could select Google Classroom as your LMS and use PearDeck, Google Calendar, and EdPuzzle as instructional resources.

Though it’s tempting to adopt new and exciting technology as it evolves, a revolving door of programs is difficult for students to juggle and can lead to app fatigue.

Teachers can further streamline their classroom resources by color-coding folders and files in their chosen LMS, posting log-in directions in easily accessible locations, and offering a landing page in their LMS that holds all of the links to digital resources.

Create Predictable Routines Around Digital Work

Next, it’s important for teachers to create clear and predictable routines around organizing digital assignments.

One routine that I’ve developed in my classroom is a living table of contents document. I create and print out a blank table of contents for each unit, and students house them in their binders. I then project the table of contents at the start of each class with the day’s newest assignments, and students fill in these new items on their hard copies when they settle in. Each assignment is numbered, and assignments located online that won’t appear in their binders are labeled with an “S” (for us, that stands for Schoology) to note that the assignment is in our LMS.

Another predictable routine is entering homework assignments into Google Calendar or agenda books together at the end of every class. Prompting students to write down their homework may seem elementary, but even older students appreciate the predictability and consistency of this routine because it reduces anxiety (rushing to write it down before the teacher moves on) and frees up brain space for critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving.

If you’re not sure that your current routine is clear and predictable, consider whether or not students could replicate your system in your absence. If students can’t get through the routine on their own, your routine may need to be articulated more clearly (such as being posted somewhere in the classroom), or it may need to be implemented more consistently.

Model a Variety of Organizational Strategies

Similar to the process of how academic skills are acquired, teachers can model organizational skills for students. Consider creating opportunities to demonstrate strategies such as how and where to save documents, how to sync information across devices, how to share calendar events with peers and parents, and how to plan for long-term projects.

You can also help students get more comfortable with organizational strategies by sharing “think-alouds” for task initiation, task prioritization, and time management. Consider using common language for reminding and prompting. For example, at the start of every new assignment, you could say something like, “Now that I’m ready to start, I’m going to open up Schoology, Google, and a Word document and close out of other tabs.”

Because executive functioning skills are not innate, providing language for them allows students to identify them, replicate them, and use tools to do them more quickly. Prioritizing these skills can improve student outcomes and prepare students for an increasingly tech-focused world.

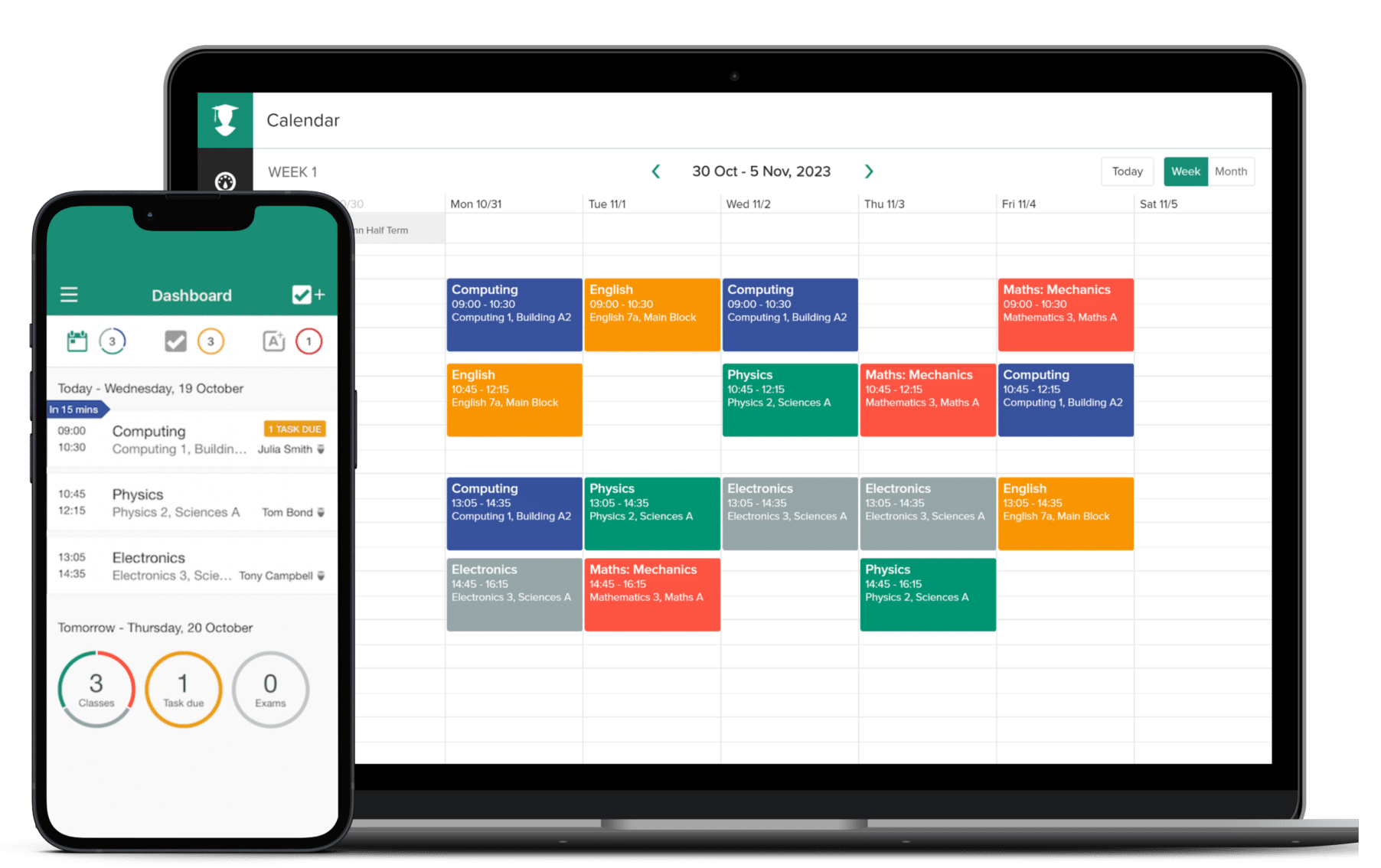

Never forget a class or assignment again.

Unlock your potential and manage your classes, tasks and exams with mystudylife- the world's #1 student planner and school organizer app..

School planner and organizer

The MyStudyLife planner app supports rotation schedules, as well as traditional weekly schedules. MSL allows you to enter your school subjects, organize your workload, and enter information about your classes – all so you can effortlessly keep on track of your school calendar.

Homework planner and task tracker

Become a master of task management by tracking every single task with our online planner – no matter how big or small.

Stay on top of your workload by receiving notifications of upcoming classes, assignments or exams, as well as incomplete tasks, on all your devices.

“Featuring a clean interface, MyStudyLife offers a comprehensive palette of schedules, timetables and personalized notifications that sync across multiple devices.”

” My Study Life is a calendar app designed specifically for students. As well as showing you your weekly timetable– with support for rotations – you can add exams, essay deadlines and reminders, and keep a list of all the tasks you need to complete. It also works on the web, so you can log in and check your schedule from any device.”

“MyStudyLife is a great study planner app that makes it simple for students to add assignments, classes, and tests to a standard weekly schedule.”

“I cannot recommend this platform enough. My Study Life is the perfect online planner to keep track of your classes and assignments. I like to use both the website and the mobile app so I can use it on my phone and computer! I do not go a single day without using this platform–go check it out!!”

“Staying organized is a critical part of being a disciplined student, and the MyStudyLife app is an excellent organizer.”

The ultimate study app

The MyStudyLife student planner helps you keep track of all your classes, tasks, assignments and exams – anywhere, on any device.

Whether you’re in middle school, high school or college MyStudyLife’s online school agenda will organize your school life for you for less stress, more productivity, and ultimately, better grades.

Take control of your day with MyStudyLife

Stay on top of your studies. Organize tasks, set reminders, and get better grades, one day at a time.

We get it- student life can be busy. Start each day with the confidence that nothing important will be forgotten, so that you can stay focused and get more done.

Track your class schedule on your phone or computer, online or offline, so that you always know where you’re meant to be.

Shift your focus back to your goals, knowing that MyStudyLife has your back with timely reminders that make success the main event of your day

Say goodbye to last minute stress with MyStudyLife’s homework planner to make procrastination a thing of the past.

Coming soon!

MyStudyLife has lots of exciting changes and features in the works. Stay tuned!

Stay on track on all of your devices.

All your tasks are automatically synced across all your devices, instantly.

Trusted by millions of students around the world.

School can be hard. MyStudyLife makes it easier.

Our easy-to-use online study planner app is available on the App Store, the Google Play Store and can be used on desktop. This means that you can use MyStudyLife anywhere and on any device.

Discover more on the MyStudyLife blog

See how MyStudyLife can help organize your life.

Best AI Websites and Apps for Homework: Top 10 Resources

Maximize your success: final exam calculator & last-minute tips for better grades, filter by category.

- Career Planning

- High School Tips and Tricks

- Productivity

- Spanish/Español

- Student News

- University Advice

- Using MyStudyLife

Hit enter to search or ESC to close

How students’ GenAI skills and reflection affect assignment instructions

The ability to use generative AI is akin to time management or other learning skills that students need practice to master. Here, Vincent Spezzo and Ilya Gokhman offer tips to make sure instructions land equally no matter students’ level of AI experience

Vincent Spezzo

.css-76pyzs{margin-right:0.25rem;} ,, ilya gokhman.

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Rather than restrict the use of AI, embrace the challenge

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, leveraging llms to assess soft skills in lifelong learning, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools, a diy guide to starting your own journal.

November 2022: ChatGPT rapidly emerges as the next big disruptor in higher education. On campuses across the US, the primary feelings are scepticism and fear of cheating, but pushing past that is the notion that this technology could be harnessed to benefit education.

Spring 2023: At Georgia Institute of Technology, our conversations and workshops on generative AI (GenAI) focus on how faculty can use it in course design, assignment creation, personalised learning efforts and more. Fear and scepticism still exist but don’t obstruct brainstorming efforts. In the summer, we see instructors’ responses range from dipping toes into the AI water and using it to create rubrics, case studies and other standard course content to diving in headfirst and using GenAI to produce entire courses.

Fall 2023: Many employers of future graduates want students to gain knowledge and experience using GenAI tools while in their degree programmes. Thinking shifts from students wanting to use GenAI to cheat to students needing to learn about GenAI to succeed. The professors at our institution are beginning to embrace the idea that they should support the correct usage of GenAI in their classrooms.

- AI can help fix student evaluations

- How can we teach AI literacy skills?

- Resource collection: How to build data literacy on campus

Here lies the challenge: how much direction should you include in GenAI-inclusive assignments? Previously, instructors had to balance assignment guidelines with student creativity, so students could create a unique submission while remaining within the assignment objectives. Now the additional task is finding the right amount of guidance to ensure students can effectively use GenAI beyond simply copying and pasting predefined prompts.

Creating GenAI assignments

How to create assignments using GenAI is one of the questions that co-authors Ilya Gokhman and Vincent Spezzo have addressed. Students in Gokhman’s public policy course worked in groups of four to complete project-based tasks and provide peer feedback to their team members at four points during the semester. The idea was to have students use GenAI as a leadership and collaboration coach to help them process and reflect on peer feedback. GenAI was used in three of the four feedback phases (students completed the first reflection unassisted). For the remaining phases, students were: 1) instructed to use GenAI with no further guidance, 2) given detailed instructions on how to use GenAI, including suggested prompts, and 3) instructed to use GenAI how they wanted, whether that was to use the instructors suggested prompts or their own.

Students divided on using GenAI

Students were surveyed on a six-point Likert scale to determine their experience using GenAI in their assignments and how it impacted their learning (see list below). This included a self-rating on their prior experience using GenAI that included options of “a lot”, “some”, “little” and “none”. From the 72 participants, several novel insights were gleaned. The most significant finding was a clear division in students’ experiences using GenAI for assignments between the two groups at opposite ends of the prior-usage spectrum. Those students who had the most prior experience rated several items significantly higher than those who came into the class never having used GenAI before. This was true despite very detailed instructions and prompt examples being added to the third and fourth assignments.

- I would rather use GenAI than complete feedback review with another person: A lot M=4.7, None M=2.78

- I felt using GenAI helped me in learning the course material: A lot M=4.8, None M=3.06

- I felt using GenAI increased my motivation to complete assignments: A lot M=4.8, None M=2.83

- Overall, I felt using GenAI had a positive impact on my course experience: A lot M=5.4, None M=3.89

Two things worth noting are: 1) while students with more experience rated items significantly higher, students with no prior experience generally still rated items around a three on the six-point scale, and 2) students who fell into the two middle groupings were not shown to be significantly different from the two extremes on almost all questions.

Students also responded to open-ended questions, with 30 per cent stating that the assignments could be improved by more frequent GenAI usage, 25 per cent commented that GenAI was useful in generating ideas and expanding their perspectives, and 20 per cent indicated a desire for more detailed instructions on using GenAI for the assignment.

Addressing students’ differences in experience using GenAI

Results pointed to a difference in instructional needs between students with no GenAI experience and those with a lot of experience. One could mistakenly assume the number of students with little or no experience will decrease as use of these technologies becomes more widespread. However, the ability to use GenAI is likely more akin to time management, studying and a host of other learning skills that students need support and practice with before mastering. Coupling this with the current lack of adoption at K-12 , it is very likely that inequity with prior usage of GenAI will exist for some time. Two actionable practices that can address this inequality:

- Include more detailed instruction and prompt examples for assignments. While not all students need this, at least 20 per cent of the students surveyed indicated they wanted even more direction than was provided, and there was no indication that the additional instructions negatively impacted students with prior experience. Part of an equitable framework is to ensure that those who need the additional support have it available, so including optional additional guidelines may be the way to go with GenAI assignments for now.

- Create and include a lesson or optional module for teaching students how to use GenAI effectively within your course or discipline. From this study, it seems that simply including more examples and instructions was not enough for some students. To address the gap of experience, students seem to need support and exposure to the basics of using GenAI that goes beyond creating good prompts. There is already discussion of including such experiences in freshmen seminar courses, but until then it will be up to instructors to help bridge the gap for students who have yet to learn how to use GenAI in ways that will benefit their education.

By using these practices, the intent is that students coming into a course with little or no prior GenAI experience can be brought up to speed and benefit at near the same level as those who have had a lot of experience using the tools. Conducting a start-of-semester survey is a good way to identify students who need additional resources and ensure they are directed to access them. While this means yet another task for instructors, the benefits to student learning and the expectations of future employers make this worth taking on.

Vincent Spezzo is assistant director of teaching and learning online in the Center for Teaching and Learning, and Ilya Gokhman is faculty lead for grand challenges in the Office of Leadership Education and Development, both at Georgia Institute of Technology.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

Rather than restrict the use of AI, embrace the challenge

Let’s think about assessments and ai in a different way, how students’ genai skills affect assignment instructions, how not to land a job in academia, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, three steps to unearth the hidden curriculum of networking.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

- Alderman Road Elementary School

- Alma Easom Elementary School

- Armstrong Elementary School

- Ashley Elementary School

- Beaver Dam Elementary School

- Benjamin Martin Elementary School

- Bill Hefner Elementary School

- Brentwood Elementary School

- C. Wayne Collier Elementary School

- Cliffdale Elementary School

- College Lakes Elementary School

- Cumberland Academy K-5

- Cumberland Mills Elementary School

- Cumberland Road Elementary School

- District 7 Elementary School

- E. Melvin Honeycutt Elementary School

- E.E. Miller Elementary School

- Eastover Central Elementary School

- Ed V. Baldwin Elementary School

- Elizabeth Cashwell Elementary School

- Ferguson-Easley Elementary School

- Gallberry Farm Elementary School

- Glendale Acres Elementary School

- Gray's Creek Elementary School

- Howard Hall Elementary School

- J.W. Coon Elementary School

- J.W. Seabrook Elementary School

- Lake Rim Elementary School

- Long Hill Elementary School

- Loyd Auman Elementary School

- Lucile Souders Elementary School

- Manchester Elementary School

- Margaret Willis Elementary School

- Mary McArthur Elementary School

- Montclair Elementary School

- Morganton Road Elementary School

- New Century International Elementary School

- Ponderosa Elementary School

- Raleigh Road Elementary School

- Rockfish Elementary School

- Sherwood Park Elementary School

- Stedman Elementary School

- Stedman Primary Elementary School

- Stoney Point Elementary School

- Sunnyside Elementary School

- Vanstory Hills Elementary School

- W.T. Brown Elementary School

- Walker-Spivey Elementary School

- Warrenwood Elementary School

- Westarea Elementary School

- William H. Owen Elementary School

- Anne Chesnutt Middle School

- Douglas Byrd Middle School

- Gray's Creek Middle School

- Hope Mills Middle School

- Howard Learning Academy Middle School

- John Griffin Middle School

- Lewis Chapel Middle School

- Luther Nick Jeralds Middle School

- Mac Williams Middle School

- Max Abbott Middle School

- New Century International Middle School

- Pine Forest Middle School

- Seventy-First Classical Middle School

- South View Middle School

- Spring Lake Middle School

- Westover Middle School

- Alger B. Wilkins High School

- Cape Fear High School

- Cross Creek Early College High School

- Cumberland Academy 6-12

- Cumberland International Early College High School

- Cumberland Polytechnic High School

- Douglas Byrd High School

- E.E. Smith High School

- Gray's Creek High School

- Jack Britt High School

- Massey Hill Classical High School

- Pine Forest High School

- Ramsey Street High School

- Reid Ross Classical School

- Seventy-First High School

- South View High School

- Terry Sanford High School

- Westover High School

- CCS Training Site

Cumberland County Schools

Student Assignment

Quick links.

- Meet the Team

- CCS Department Directory

- New Student Enrollment

- CCS Internal Student Transfer

- Online Student Enrollment

- Student Assignment Forms

- Foreign Exchange Students Information

- Student Code of Conduct

Department Overview