Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

What are Peer-Reviewed Journals?

- A Definition of Peer-Reviewed

- Research Guides and Tutorials

- Library FAQ Page This link opens in a new window

Research Help

540-828-5642 [email protected] 540-318-1962

- Bridgewater College

- Church of the Brethren

- regional history materials

- the Reuel B. Pritchett Museum Collection

Additional Resources

- What are Peer-reviewed Articles and How Do I Find Them? From Capella University Libraries

Introduction

Peer-reviewed journals (also called scholarly or refereed journals) are a key information source for your college papers and projects. They are written by scholars for scholars and are an reliable source for information on a topic or discipline. These journals can be found either in the library's online databases, or in the library's local holdings. This guide will help you identify whether a journal is peer-reviewed and show you tips on finding them.

What is Peer-Review?

Peer-review is a process where an article is verified by a group of scholars before it is published.

When an author submits an article to a peer-reviewed journal, the editor passes out the article to a group of scholars in the related field (the author's peers). They review the article, making sure that its sources are reliable, the information it presents is consistent with the research, etc. Only after they give the article their "okay" is it published.

The peer-review process makes sure that only quality research is published: research that will further the scholarly work in the field.

When you use articles from peer-reviewed journals, someone has already reviewed the article and said that it is reliable, so you don't have to take the steps to evaluate the author or his/her sources. The hard work is already done for you!

Identifying Peer-Review Journals

If you have the physical journal, you can look for the following features to identify if it is peer-reviewed.

Masthead (The first few pages) : includes information on the submission process, the editorial board, and maybe even a phrase stating that the journal is "peer-reviewed."

Publisher: Peer-reviewed journals are typically published by professional organizations or associations (like the American Chemical Society). They also may be affiliated with colleges/universities.

Graphics: Typically there either won't be any images at all, or the few charts/graphs are only there to supplement the text information. They are usually in black and white.

Authors: The authors are listed at the beginning of the article, usually with information on their affiliated institutions, or contact information like email addresses.

Abstracts: At the beginning of the article the authors provide an extensive abstract detailing their research and any conclusions they were able to draw.

Terminology: Since the articles are written by scholars for scholars, they use uncommon terminology specific to their field and typically do not define the words used.

Citations: At the end of each article is a list of citations/reference. These are provided for scholars to either double check their work, or to help scholars who are researching in the same general area.

Advertisements: Peer-reviewed journals rarely have advertisements. If they do the ads are for professional organizations or conferences, not for national products.

Identifying Articles from Databases

When you are looking at an article in an online database, identifying that it comes from a peer-reviewed journal can be more difficult. You do not have access to the physical journal to check areas like the masthead or advertisements, but you can use some of the same basic principles.

Points you may want to keep in mind when you are evaluating an article from a database:

- A lot of databases provide you with the option to limit your results to only those from peer-reviewed or refereed journals. Choosing this option means all of your results will be from those types of sources.

- When possible, choose the PDF version of the article's full text. Since this is exactly as if you photocopied from the journal, you can get a better idea of its layout, graphics, advertisements, etc.

- Even in an online database you still should be able to check for author information, abstracts, terminology, and citations.

- Next: Research Guides and Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Dec 12, 2023 4:06 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bridgewater.edu/c.php?g=945314

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

What is peer review.

Peer review is ‘a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already know.’ You can learn more in this explainer from the Social Science Space.

Peer review brings academic research to publication in the following ways:

- Evaluation – Peer review is an effective form of research evaluation to help select the highest quality articles for publication.

- Integrity – Peer review ensures the integrity of the publishing process and the scholarly record. Reviewers are independent of journal publications and the research being conducted.

- Quality – The filtering process and revision advice improve the quality of the final research article as well as offering the author new insights into their research methods and the results that they have compiled. Peer review gives authors access to the opinions of experts in the field who can provide support and insight.

Types of peer review

- Single-anonymized – the name of the reviewer is hidden from the author.

- Double-anonymized – names are hidden from both reviewers and the authors.

- Triple-anonymized – names are hidden from authors, reviewers, and the editor.

- Open peer review comes in many forms . At Sage we offer a form of open peer review on some journals via our Transparent Peer Review program , whereby the reviews are published alongside the article. The names of the reviewers may also be published, depending on the reviewers’ preference.

- Post publication peer review can offer useful interaction and a discussion forum for the research community. This form of peer review is not usual or appropriate in all fields.

To learn more about the different types of peer review, see page 14 of ‘ The Nuts and Bolts of Peer Review ’ from Sense about Science.

Please double check the manuscript submission guidelines of the journal you are reviewing in order to ensure that you understand the method of peer review being used.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- Transparent Peer Review

- How to Review Articles

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage Editorial Policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

- Open Resources & Current Initiatives

- Discipline Hubs

- USU Library

Articles: Finding (and Identifying) Peer-Reviewed Articles: What is Peer Review?

- What is Peer Review?

- Finding Peer Reviewed Articles

- Databases That Can Determine Peer Review

Peer Review in 3 Minutes

What is "Peer-Review"?

What are they.

Scholarly articles are papers that describe a research study.

Why are scholarly articles useful?

They report original research projects that have been reviewed by other experts before they are accepted for publication, so you can reasonably be assured that they contain valid information.

How do you identify scholarly or peer-reviewed articles?

- They are usually fairly lengthy - most likely at least 7-10 pages

- The authors and their credentials should be identified, at least the company or university where the author is employed

- There is usually a list of References or Works Cited at the end of the paper, listing the sources that the authors used in their research

How do you find them?

Some of the library's databases contain scholarly articles, either exclusively or in combination with other types of articles.

Google Scholar is another option for searching for scholarly articles.

Know the Difference Between Scholarly and Popular Journals/Magazines

Peer reviewed articles are found in scholarly journals. The checklist below can help you determine if what you are looking at is peer reviewed or scholarly.

- Both kinds of journals and magazines can be useful sources of information.

- Popular magazines and newspapers are good for overviews, recent news, first-person accounts, and opinions about a topic.

- Scholarly journals, often called scientific or peer-reviewed journals, are good sources of actual studies or research conducted about a particular topic. They go through a process of review by experts, so the information is usually highly reliable.

- Next: Finding Peer Reviewed Articles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2023 10:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usu.edu/peer-review

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Understanding Peer Review in Science

Peer review is an essential element of the scientific publishing process that helps ensure that research articles are evaluated, critiqued, and improved before release into the academic community. Take a look at the significance of peer review in scientific publications, the typical steps of the process, and and how to approach peer review if you are asked to assess a manuscript.

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of work by peers, who are people with comparable experience and competency. Peers assess each others’ work in educational settings, in professional settings, and in the publishing world. The goal of peer review is improving quality, defining and maintaining standards, and helping people learn from one another.

In the context of scientific publication, peer review helps editors determine which submissions merit publication and improves the quality of manuscripts prior to their final release.

Types of Peer Review for Manuscripts

There are three main types of peer review:

- Single-blind review: The reviewers know the identities of the authors, but the authors do not know the identities of the reviewers.

- Double-blind review: Both the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other.

- Open peer review: The identities of both the authors and reviewers are disclosed, promoting transparency and collaboration.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each method. Anonymous reviews reduce bias but reduce collaboration, while open reviews are more transparent, but increase bias.

Key Elements of Peer Review

Proper selection of a peer group improves the outcome of the process:

- Expertise : Reviewers should possess adequate knowledge and experience in the relevant field to provide constructive feedback.

- Objectivity : Reviewers assess the manuscript impartially and without personal bias.

- Confidentiality : The peer review process maintains confidentiality to protect intellectual property and encourage honest feedback.

- Timeliness : Reviewers provide feedback within a reasonable timeframe to ensure timely publication.

Steps of the Peer Review Process

The typical peer review process for scientific publications involves the following steps:

- Submission : Authors submit their manuscript to a journal that aligns with their research topic.

- Editorial assessment : The journal editor examines the manuscript and determines whether or not it is suitable for publication. If it is not, the manuscript is rejected.

- Peer review : If it is suitable, the editor sends the article to peer reviewers who are experts in the relevant field.

- Reviewer feedback : Reviewers provide feedback, critique, and suggestions for improvement.

- Revision and resubmission : Authors address the feedback and make necessary revisions before resubmitting the manuscript.

- Final decision : The editor makes a final decision on whether to accept or reject the manuscript based on the revised version and reviewer comments.

- Publication : If accepted, the manuscript undergoes copyediting and formatting before being published in the journal.

Pros and Cons

While the goal of peer review is improving the quality of published research, the process isn’t without its drawbacks.

- Quality assurance : Peer review helps ensure the quality and reliability of published research.

- Error detection : The process identifies errors and flaws that the authors may have overlooked.

- Credibility : The scientific community generally considers peer-reviewed articles to be more credible.

- Professional development : Reviewers can learn from the work of others and enhance their own knowledge and understanding.

- Time-consuming : The peer review process can be lengthy, delaying the publication of potentially valuable research.

- Bias : Personal biases of reviews impact their evaluation of the manuscript.

- Inconsistency : Different reviewers may provide conflicting feedback, making it challenging for authors to address all concerns.

- Limited effectiveness : Peer review does not always detect significant errors or misconduct.

- Poaching : Some reviewers take an idea from a submission and gain publication before the authors of the original research.

Steps for Conducting Peer Review of an Article

Generally, an editor provides guidance when you are asked to provide peer review of a manuscript. Here are typical steps of the process.

- Accept the right assignment: Accept invitations to review articles that align with your area of expertise to ensure you can provide well-informed feedback.

- Manage your time: Allocate sufficient time to thoroughly read and evaluate the manuscript, while adhering to the journal’s deadline for providing feedback.

- Read the manuscript multiple times: First, read the manuscript for an overall understanding of the research. Then, read it more closely to assess the details, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Evaluate the structure and organization: Check if the manuscript follows the journal’s guidelines and is structured logically, with clear headings, subheadings, and a coherent flow of information.

- Assess the quality of the research: Evaluate the research question, study design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Consider whether the methods are appropriate, the results are valid, and the conclusions are supported by the data.

- Examine the originality and relevance: Determine if the research offers new insights, builds on existing knowledge, and is relevant to the field.

- Check for clarity and consistency: Review the manuscript for clarity of writing, consistent terminology, and proper formatting of figures, tables, and references.

- Identify ethical issues: Look for potential ethical concerns, such as plagiarism, data fabrication, or conflicts of interest.

- Provide constructive feedback: Offer specific, actionable, and objective suggestions for improvement, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript. Don’t be mean.

- Organize your review: Structure your review with an overview of your evaluation, followed by detailed comments and suggestions organized by section (e.g., introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion).

- Be professional and respectful: Maintain a respectful tone in your feedback, avoiding personal criticism or derogatory language.

- Proofread your review: Before submitting your review, proofread it for typos, grammar, and clarity.

- Couzin-Frankel J (September 2013). “Biomedical publishing. Secretive and subjective, peer review proves resistant to study”. Science . 341 (6152): 1331. doi: 10.1126/science.341.6152.1331

- Lee, Carole J.; Sugimoto, Cassidy R.; Zhang, Guo; Cronin, Blaise (2013). “Bias in peer review”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (1): 2–17. doi: 10.1002/asi.22784

- Slavov, Nikolai (2015). “Making the most of peer review”. eLife . 4: e12708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12708

- Spier, Ray (2002). “The history of the peer-review process”. Trends in Biotechnology . 20 (8): 357–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01985-6

- Squazzoni, Flaminio; Brezis, Elise; Marušić, Ana (2017). “Scientometrics of peer review”. Scientometrics . 113 (1): 501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2518-4

Related Posts

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to know if an article is peer reviewed [6 key features]

Features of a peer reviewed article

How to find peer reviewed articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviewed articles, related articles.

A peer reviewed article refers to a work that has been thoroughly assessed, and based on its quality, has been accepted for publication in a scholarly journal. The aim of peer reviewing is to publish articles that meet the standards established in each field. This way, peer reviewed articles that are published can be taken as models of research practices.

A peer reviewed article can be recognized by the following features:

- It is published in a scholarly journal.

- It has a serious, and academic tone.

- It features an abstract at the beginning.

- It is divided by headings into introduction, literature review or background, discussion, and conclusion.

- It includes in-text citations, and a bibliography listing accurately all references.

- Its authors are affiliated with a research institute or university.

There are many ways in which you can find peer reviewed articles, for instance:

- Check the journal's features and 'About' section. This part should state if the articles published in the journal are peer reviewed, and the type of reviewing they perform.

- Consult a database with peer reviewed journals, such as Web of Science Master Journal List , PubMed , Scopus , Google Scholar , etc. Specify in the advanced search settings that you are looking for peer reviewed journals only.

- Consult your library's database, and specify in the search settings that you are looking for peer reviewed journals only.

➡️ Want to know if a source is scholarly? Check out our guide on scholarly sources.

➡️ Want to know if a source is credible? Find out in our guide on credible sources (+ how to find them).

A peer reviewed article refers to a work that has been thoroughly assessed, and based on its quality has been accepted to be published in a scholarly journal.

Once an article has been submitted for publication to a peer reviewed journal, the journal assigns the article to an expert in the field, who is considered the “peer”.

The easiest way to find a peer reviewed article is to narrow down the search in the "Advanced search" option. Then, mark the box that says "peer reviewed".

Consult a database with peer reviewed journals, such as Web of Science Master Journal List , PubMed , Scopus , etc.

There are many views on peer reviewed articles. Take a look at Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide for more insight on this topic.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 2 September 2022.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, frequently asked questions about peer review.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymised) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymised comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymised) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymised) review – where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymised – does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimises potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymise everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimise back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarise the argument in your own words

Summarising the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organised. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticised, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the ‘compliment sandwich’, where you ‘sandwich’ your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarised or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilising rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication.

For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project – provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well regarded.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field.

It acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 02). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/peer-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a double-blind study | introduction & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data cleaning | a guide with examples & steps.

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Finding Journal Articles 101

Peer-reviewed or refereed.

- Research Article

- Review Article

- By Journal Title

What Does "Peer-reviewed" or "Refereed" Mean?

Peer review is a process that journals use to ensure the articles they publish represent the best scholarship currently available. When an article is submitted to a peer reviewed journal, the editors send it out to other scholars in the same field (the author's peers) to get their opinion on the quality of the scholarship, its relevance to the field, its appropriateness for the journal, etc.

Publications that don't use peer review (Time, Cosmo, Salon) just rely on the judgment of the editors whether an article is up to snuff or not. That's why you can't count on them for solid, scientific scholarship.

Note:This is an entirely different concept from " Review Articles ."

How do I know if a journal publishes peer-reviewed articles?

Usually, you can tell just by looking. A scholarly journal is visibly different from other magazines, but occasionally it can be hard to tell, or you just want to be extra-certain. In that case, you turn to Ulrich's Periodical Directory Online . Just type the journal's title into the text box, hit "submit," and you'll get back a report that will tell you (among other things) whether the journal contains articles that are peer reviewed, or, as Ulrich's calls it, Refereed.

Remember, even journals that use peer review may have some content that does not undergo peer review. The ultimate determination must be made on an article-by-article basis.

For example, the journal Science publishes a mix of peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed content. Here are two articles from the same issue of Science .

This one is not peer-reviewed: https://science-sciencemag-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/content/303/5655/154.1 This one is a peer-reviewed research article: https://science-sciencemag-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/content/303/5655/226

That is consistent with the Ulrichsweb description of Science , which states, "Provides news of recent international developments and research in all fields of science. Publishes original research results, reviews and short features."

Test these periodicals in Ulrichs :

- Advances in Dental Research

- Clinical Anatomy

- Molecular Cancer Research

- Journal of Clinical Electrophysiology

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2023 9:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/journalarticles101

Peer Reviewed Literature

What is peer review, terminology, peer review what does that mean, what types of articles are peer-reviewed, what information is not peer-reviewed, what about google scholar.

- How do I find peer-reviewed articles?

- Scholarly vs. Popular Sources

Research Librarian

For more help on this topic, please contact our Research Help Desk: [email protected] or 781-768-7303. Stay up-to-date on our current hours . Note: all hours are EST.

This Guide was created by Carolyn Swidrak (retired).

Research findings are communicated in many ways. One of the most important ways is through publication in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals.

Research published in scholarly journals is held to a high standard. It must make a credible and significant contribution to the discipline. To ensure a very high level of quality, articles that are submitted to scholarly journals undergo a process called peer-review.

Once an article has been submitted for publication, it is reviewed by other independent, academic experts (at least two) in the same field as the authors. These are the peers. The peers evaluate the research and decide if it is good enough and important enough to publish. Usually there is a back-and-forth exchange between the reviewers and the authors, including requests for revisions, before an article is published.

Peer review is a rigorous process but the intensity varies by journal. Some journals are very prestigious and receive many submissions for publication. They publish only the very best, most highly regarded research.

The terms scholarly, academic, peer-reviewed and refereed are sometimes used interchangeably, although there are slight differences.

Scholarly and academic may refer to peer-reviewed articles, but not all scholarly and academic journals are peer-reviewed (although most are.) For example, the Harvard Business Review is an academic journal but it is editorially reviewed, not peer-reviewed.

Peer-reviewed and refereed are identical terms.

From Peer Review in 3 Minutes [Video], by the North Carolina State University Library, 2014, YouTube (https://youtu.be/rOCQZ7QnoN0).

Peer reviewed articles can include:

- Original research (empirical studies)

- Review articles

- Systematic reviews

- Meta-analyses

There is much excellent, credible information in existence that is NOT peer-reviewed. Peer-review is simply ONE MEASURE of quality.

Much of this information is referred to as "gray literature."

Government Agencies

Government websites such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) publish high level, trustworthy information. However, most of it is not peer-reviewed. (Some of their publications are peer-reviewed, however. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, published by the CDC is one example.)

Conference Proceedings

Papers from conference proceedings are not usually peer-reviewed. They may go on to become published articles in a peer-reviewed journal.

Dissertations

Dissertations are written by doctoral candidates, and while they are academic they are not peer-reviewed.

Many students like Google Scholar because it is easy to use. While the results from Google Scholar are generally academic they are not necessarily peer-reviewed. Typically, you will find:

- Peer reviewed journal articles (although they are not identified as peer-reviewed)

- Unpublished scholarly articles (not peer-reviewed)

- Masters theses, doctoral dissertations and other degree publications (not peer-reviewed)

- Book citations and links to some books (not necessarily peer-reviewed)

- Next: How do I find peer-reviewed articles? >>

- Last Updated: Feb 12, 2024 9:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.regiscollege.edu/peer_review

- Collections

- Services & Support

Which Source Should I Use?

- The Right Source For Your Need-Authority

- Finding Subject Specific Sources: Research Guides

- Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles

- Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles- Arts & Humanities

- How to Read a Journal Article

- Locating Journals

- How to Find Streaming Media

The Peer Review Process

So you need to use scholarly, peer-reviewed articles for an assignment...what does that mean?

Peer review is a process for evaluating research studies before they are published by an academic journal. These studies typically communicate original research or analysis for other researchers.

The Peer Review Process at a Glance:

Looking for peer-reviewed articles? Try searching in OneSearch or a library database and look for options to limit your results to scholarly/peer-reviewed or academic journals. Check out this brief tutorial to show you how: How to Locate a Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Article

Part 1: Watch the Video

Part 1: watch the video all about peer review (3 min.) and reflect on discussion questions..

Discussion Questions

After watching the video, reflect on the following questions:

- According to the video, what are some of the pros and cons of the peer review process?

- Why is the peer review process important to scholarship?

- Do you think peer reviewers should be paid for their work? Why or why not?

Part 2: Practice

Part 2: take an interactive tutorial on reading a research article for your major..

Includes a certification of completion to download and upload to Canvas.

Social Sciences

(e.g. Psychology, Sociology)

(e.g. Health Science, Biology)

Arts & Humanities

(e.g. Visual & Media Arts, Cultural Studies, Literature, History)

Click on the handout to view in a new tab, download, or print.

For Instructors

- Teaching Peer Review for Instructors

In class or for homework, watch the video “All About Peer Review” (3 min.) .

Video discussion questions:

- According to the video, what are some of the pros and cons of the peer review process

Assignment Ideas

- Ask students to conduct their own peer review of an important journal article in your field. Ask them to reflect on the process. What was hard to critique?

- Have students examine a journals’ web page with information for authors. What information is given to the author about the peer review process for this journal?

- Assign this reading by CSUDH faculty member Terry McGlynn, "Should journals pay for manuscript reviews?" What is the author's argument? Who profits the most from published research? You could also hold a debate with one side for paying reviewers and the other side against.

- Search a database like Cabell’s for information on the journal submission process for a particular title or subject. How long does peer review take for a particular title? Is it is a blind review? How many reviewers are solicited? What is their acceptance rate?

- Assign short readings that address peer review models. We recommend this issue of Nature on peer review debate and open review and this Chronicle of Higher Education article on open review in Shakespeare Quarterly .

Proof of Completion

Mix and match this suite of instructional materials for your course needs!

Questions about integrating a graded online component into your class, contact the Online Learning Librarian, Rebecca Nowicki ( [email protected] ).

Example of a certificate of completion:

- << Previous: Finding Subject Specific Sources: Research Guides

- Next: Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles- Arts & Humanities >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sdsu.edu/WhichSource

Evaluating Information Sources: What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article?

- Should I Trust Internet Sources?

What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article?

Anali Perry, a librarian from Arizona State University Libraries, gives a quick definition of a peer-reviewed article.

The Library Minute: Academic Articles from ASU Libraries on Vimeo .

How Do Peer-Reviewed Articles Differ From Popular Ones?

This 3 minute video from the Peabody Library at Vanderbilt University talks about the differences between popular and scholarly articles. It also mentions trade publications.

What Is Peer Review?

In academic publishing, the goal of peer review is to assess the quality of articles submitted for publication in a scholarly journal. Before an article is deemed appropriate to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, it must undergo the following process:

- The author of the article must submit it to the journal editor who forwards the article to experts in the field. Because the reviewers specialize in the same scholarly area as the author, they are considered the author’s peers (hence “peer review”).

- These impartial reviewers are charged with carefully evaluating the quality of the submitted manuscript.

- The peer reviewers check the manuscript for accuracy and assess the validity of the research methodology and procedures.

- If appropriate, they suggest revisions. If they find the article lacking in scholarly validity and rigor, they reject it.

Because a peer-reviewed journal will not publish articles that fail to meet the standards established for a given discipline, peer-reviewed articles that are accepted for publication exemplify the best research practices in a field.

Features of a Peer-Reviewed Article

When you are determining whether or not the article you found is a peer-reviewed article, you should consider the following.

Does the article have the following features?

Also consider...

- Is the journal in which you found the article published or sponsored by a professional scholarly society, professional association, or university academic department? Does it describe itself as a peer-reviewed publication? (To know that, check the journal's website).

- Did you find a citation for it in one of the databases that includes scholarly publications? (Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, etc.)? Read the database description to see if it includes scholarly publications.

- In the database, did you limit your search to scholarly or peer-reviewed publications? (See video tutorial below for a demonstration.)

- Is the topic of the article narrowly focused and explored in depth ?

- Is the article based on either original research or authorities in the field (as opposed to personal opinion)?

- Is the article written for readers with some prior knowledge of the subject?

- If your field is social or natural science, is the article divided into sections with headings such as those listed below?

How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles?

The easiest and fastest way to find peer-reviewed articles is to search the online library databases , many of which include peer-reviewed journals. To make sure your results come from peer-reviewed (also called "scholarly" or "academic") journals, do the following:

- Read the database description to determine if it features peer-reviewed articles.

- When you search for articles, choose the Advanced Search option. On the search screen, look for a check-box that allows you to limit your results to peer-reviewed only.

- If you didn't check off the "peer-reviewed articles only" box, try to see if your results can organized by source . For example, the database Criminal Justice Abstracts will let you choose the tab "Peer-Reviewed Journals."

Video tutorial

Watch this video through to the end. It will show you how to use a library database and how to narrow your search results down to just peer-reviewed articles.

- << Previous: Should I Trust Internet Sources?

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2019 2:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/evaluatingsources

University of Denver

University libraries, research guides, a guide to health & medical research.

- Evidence based medicine

- Consumer health info

- Journal articles

- Books & media

- Clinical guidelines, statistics, & more

- Newspapers & magazines

- Get full text of a specific article

- Request sources not at DU Libraries

- Search databases effectively

- Evaluate your sources

- Confirm an article is peer-reviewed

What is a scholarly, peer-reviewed journal?

Confirm that an article is peer-reviewed -- part 1:, confirm that an article is peer-reviewed -- part 2:, primary research articles vs review articles.

- Cite sources properly

First, determine whether the article is published in a peer-reviewed journal. There are two ways to determine whether a journal has a peer-review process in place (which means that it is a scholarly source):

Next, look at the article to see what elements it has in it, and consult the table below to make your final determination:

Why are some of the articles in a peer-reviewed journal NOT peer-reviewed?

The peer-review process take a lot of time and effort, so it's reserved for articles where accuracy is essential -- reports of new and original research, or summaries of research. Other researchers are going to use and build upon the data and information reported in those articles, so it's important that it is accurate.

For articles such as book reviews, accuracy is not as important (after all, book reviews and editorials are highly influenced by personal opinions). Therefore, these articles are checked for grammar by an editor but don't undergo the rigorous peer-review process.

A primary research article presents a first report of original research. It's written by the people who performed the research, and it's usually written for other researchers in the same field.

Example of a primary research article: Bramhanwade, K.; Shende, S.; Bonde, S.; Gade, A.; Rai, M. Fungicidal activity of Cu nanoparticles against Fusarium causing crop diseases. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2016 , 14, 229-235.

The structure is designed to be a practical and efficient means of delivering information. It also ensures that key points will be covered in the article, including:

A scholarly review article is a special type of peer-reviewed article that provides an overview of an area of research; it describes major advances, discoveries, and ongoing debates in that field. It can be very useful to look for review articles if you are new to an area of research.

Example of a scholarly review article: Kasana, R. C.; Panwar, N. R.; Kaul, R. K.; Kumar, P. Biosynthesis and effects of copper nanoparticles on plants. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2017 ,15, 233-240.

- << Previous: Evaluate your sources

- Next: Cite sources properly >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.du.edu/health-medical

Ask a Librarian

- Finding Company Information

- Finding Research Articles

- What does peer-reviewed mean?

- Citing Sources in APA

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- TCOM 101 Critical Media Literacy -- Moore

TCOM 101 Critical Media Literacy -- Moore: What does peer-reviewed mean?

Peer-reviewed articles.

A peer-reviewed (or refereed) article has been read, evaluated, and approved for publication by scholars with expertise and knowledge related to the article’s contents. Peer-reviewing helps insure that articles provide accurate, verifiable, and valuable contributions to a field of study.

- The peer-review process is anonymous, to prevent personal biases and favoritism from affecting the outcomes. Reviewers read manuscripts that omit the names of the author(s). When the reviewers’ feedback is given to the author(s), the reviewers’ names are omitted.

- Editors of journals select reviewers who are experts in the subjects addressed in the article. Reviewers consider the clarity and validity of the research and whether it offers original and important knowledge to a particular field of study.

How do I know if an article is peer reviewed?

- Most scholarly journal articles also have symbols next to their record in the library catalog.

- Search the journal title in Ulrichsweb Global Serials Directory.

- In general, book reviews, opinion pieces/editorials, and brief news articles are not peer-reviewed.

- Published peer-reviewed articles name their author(s) and provide details about how to verify the contents of the articles (such as footnotes and/or a list of “literature cited” or “references”). If the article does not name its author(s), it is not peer-reviewed.

- Some articles provide specific information about the peer-review process, such as dates of review and approval for publication.

- Some journals list peer-reviewed articles as “research” or “articles” in the table of contents to distinguish them from other materials like “news” or “book reviews”.

What is a scholarly peer reviewed journal article?

- << Previous: Research Article Evaluation

- Next: Citing Sources in APA >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2023 4:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/tcom101

Evidence-Based Health Care

- Learning About EBP

- The 6S Pyramid

- Forming Questions

- Identifying Peer-Reviewed Resources

- Critical Appraisal

What is Peer Review?

If an article is peer reviewed , it was reviewed by scholars who are experts in related academic or professional fields before it was published. Those scholars assessed the quality of the article's research, as well as its overall contribution to the literature in their field.

When we talk about peer-reviewed journals , we're referring to journals that use a peer-review process.

Related terms you might hear include:

- Academic: Intended for academic use, or an academic audience.

- Scholarly: Intended for scholarly use, or a scholarly audience.

- Refereed: Refers to a specific kind of peer-review process.

National University Library System. (2018). "Find Articles: How to Find Scholarly/Peer-Reviewed Articles". Retrieved from: http://nu.libguides.com/articles/PR.

How Peer Review Works

Here's how it typically works:

- Submission : An author submits their research paper or article to a scholarly journal for publication consideration.

- Editorial Assessment : The journal's editor(s) review the submission to determine if it meets the journal's scope, standards, and criteria for publication. They may reject it outright if it doesn't meet these criteria.

- Peer Review : If the submission passes the initial editorial assessment, it is sent out to experts in the field, known as "peers" or "referees," for thorough evaluation. These experts are typically researchers or scholars who have expertise in the subject matter of the submitted work but are not directly affiliated with the author.

- Peer Feedback : The peer reviewers carefully examine the submission for its originality, significance, methodology, accuracy, and overall quality. They provide detailed feedback, critiques, and suggestions for improvement to the journal's editor(s).

- Editorial Decision : Based on the feedback from the peer reviewers, the editor(s) make a decision on whether to accept the submission for publication, request revisions from the author(s) to address specific concerns, or reject it if it does not meet the journal's standards.

- Revision and Resubmission (if applicable): If revisions are requested, the author(s) revise their work in response to the reviewers' feedback and resubmit it to the journal. The revised version may undergo further rounds of peer review until it meets the journal's requirements.

- Publication : Once the submission has successfully passed peer review and any necessary revisions, it is accepted for publication and included in the journal's forthcoming issue.

Peer review serves as a critical checkpoint in the academic publishing process, helping to ensure that only high-quality, rigorously researched, and credible scholarly work is disseminated to the academic community and the public. It helps to uphold standards of academic integrity, accuracy, and reliability.

How Do I Know If a Journal is Peer-Reviewed?

The easiest way to find out if a journal is peer-reviewed is to search for the title in a serials directory like UlrichsWeb:

- UlrichsWeb Global Serials Directory Includes in each record: ISBN, title, publisher, country of publication, status (Active, ceased, etc.), start year, frequency, refereed (Yes/No), media, language, price, subject, Dewey #, circulation, editor(s), email, URL, brief description Also known as: Ulrichs

How to Use Ulrichs

1. Type the name of the journal in the search bar and click the search button. NOTE : you need to use the full name of the journal, not an abbreviation.

2. Locate the journal in the results list. You may see multiple entries for one journal because Ulrichs lists print, electronic, and international version separately.

Other Techniques for Determining Peer Review Status

Determining whether an article has been peer-reviewed without a service like Ulrichs typically involves a few steps:

- Journal Reputation: Look at the journal where the article is published. Reputable academic journals usually have a peer-review process in place. Check the journal's website or databases like PubMed, Scopus, or Web of Science to see if it's peer-reviewed.

- Article Information: Sometimes, journals explicitly state whether articles undergo peer review. This information can usually be found on the journal's website, alongside other details about submission and publication processes.

- Author Guidelines: Journals often provide authors with guidelines that include information about the peer-review process. Authors are usually instructed to submit their work for peer review as part of the publication process.

- Editorial Policies: Review the journal's editorial policies. Peer-reviewed journals typically have detailed descriptions of their review processes, including how they select reviewers, criteria for acceptance, and timelines for review.

- Check the Article Itself: While this is not always conclusive, some peer-reviewed articles will include a statement indicating that the article has undergone peer review. Look for phrases like "peer-reviewed" and "refereed."

- Indexing Databases: Many indexing databases only include peer-reviewed journals in their listings. If you find the article indexed in databases like PubMed, you can generally assume it has been peer-reviewed.

Remember that while these methods can help you determine whether an article has undergone peer review, it's always good practice to critically evaluate the content of the article regardless of its peer-review status.

How Do I Know If an Article is Peer-Reviewed?

Even if an article was published in a peer-reviewed journal, it may not necessarily be peer-reviewed itself; for example, a commentary article may undergo editorial review instead, meaning it was only reviewed by the journal editor.

There are some clues you can look for to help you identify if an article is peer-reviewed:

- Does the abstract discuss the author's/authors' research process?

- Does the abstract include a variation of the phrase "This study..."?

- Is there a Methodology or Data header in the text of the article?

- Does the paper discuss related research in a literature review?

- Is there an analysis of a need for further research, or gaps in the literature?

- Are the references for scholarly articles and books?

If an article published in a verified peer-reviewed journal includes these elements, it is most likely a peer-reviewed article.

- National University Library: Scholarly Checklist Use this printable checklist to help you identify scholarly, research-based articles

Identifying Peer Reviewed Materials in Scholarly Databases

Peer reviewed material in pubmed and medline.

Good news! Most of the journals in Medline and PubMed are peer reviewed. Generally speaking, if you find a journal citation in Medline and PubMed you should be just fine. However, there is no way to limit your results within PubMed or the Medline EBSCO interface to knock out the few publications that are not considered refereed titles.

However, EBSCO (a third-party vendor) does provide a list of all titles within Medline and lets you see which titles are considered peer reviewed. You can check if your journal is OK - see the "Peer Review" tab in the report below to see the very small list of titles that don't make the cut.

- Medline: List of Full-Text Journals These journals cover a wide range of subjects within the biomedical and health fields containing information needed by doctors, nurses, health professionals, and researchers engaged in clinical care, public health, and health policy development. Information on peer-reviewed status available within table of titles.

Peer Reviewed Material in CINAHL & PsycINFO

In CINAHL and PsycINFO, there is a "Peer Reviewed" box in the advanced search, which allows you to limit your search results to those that have been identified as peer reviewed.

- View the Title List for CINAHL Complete This page links to the full title list for CINAHL Complete in both Excel and HTML formats.

- << Previous: Forming Questions

- Next: Critical Appraisal >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 11:08 AM

- URL: https://libguides.libraries.wsu.edu/EBHC

Peer-reviewed journal articles

- Overview of peer review

- Scholarly and academic - good enough?

- Find peer-reviewed articles

Using Library Search

Is a journal peer reviewed, check the journal.

Resources listed in Library Search that are peer reviewed will include the Peer Reviewed icon.

For example:

If you have not used Library Search to find the article, which may indicate if it's peer reviewed, you can use Ulrichsweb to check.

- Go to Ulrichsweb

Screenshot of search box in UlrichsWeb © Proquest

- Enter the journal title in the search box.

Screenshot of results list in UlrichsWeb © Proquest

- If there are no results, do a search in Ulrichsweb to find journals in your field that are peer reviewed.

Be aware that not all articles in peer reviewed journals are refereed or peer reviewed, for example, editorials and book reviews.

If the journal is not listed in Ulrichsweb :

- Go to the journal's website

- Check for information on a peer review process for the journal. Try the Author guidelines , Instructions for authors or About this journal sections.

If you can find no evidence that a journal is peer reviewed, but you are required to have a refereed article, you may need to choose a different article.

- << Previous: Find peer-reviewed articles

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2023 2:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/how-to-find/peer-reviewed-articles

What is peer-reviewed?

What does “peer reviewed” mean, how do academic articles improve the quality of your work, how can you tell if an academic journal article is peer reviewed or not, how can you use the library databases to find “peer reviewed” articles, for further information.

Watch this short video for a brief overview of the subject.

Alternatively, have a look at the below presentation or read the full article.

You have no doubt seen the mention of “peer reviewed” academic articles in your project outlines and heard your faculty requiring you to base your research on “peer reviewed” articles. But what exactly does the term “peer reviewed” mean? How does using “peer reviewed” articles improve the quality of your work? How can you tell if an article is peer reviewed or not? How can you use the library databases to find “peer reviewed” articles?

A simple definition would be “read thoroughly and checked by fellow experts”. The peer review process guarantees the validity, reliability, and credibility of the article.

In practice, before an article is published in an academic journal, it is sent to a panel of experts in the same field or discipline. These experts read the article carefully, checking for weaknesses or gaps in the arguments, research methodology or results and discussion. The experts also consider whether the article is contributing something new to the field of knowledge and not just repeating information already known. They give feedback to the authors of the article suggesting improvements or changes. The authors improve their article according to the feedback and then resubmit the article for publication. The article is peer reviewed again. If it now reaches the required standard, it will be published. If not, it will be rejected and will not appear in the journal. The peer review process usually takes several months.

Since the academic journal guarantees the validity, reliability, and credibility of the information it publishes, you can be sure that when you base your work on peer reviewed articles you are using the most authoritative sources. This in turn gives your work an air of authority and credibility. The very fact of citing the work of experts demonstrates the seriousness of your own work.

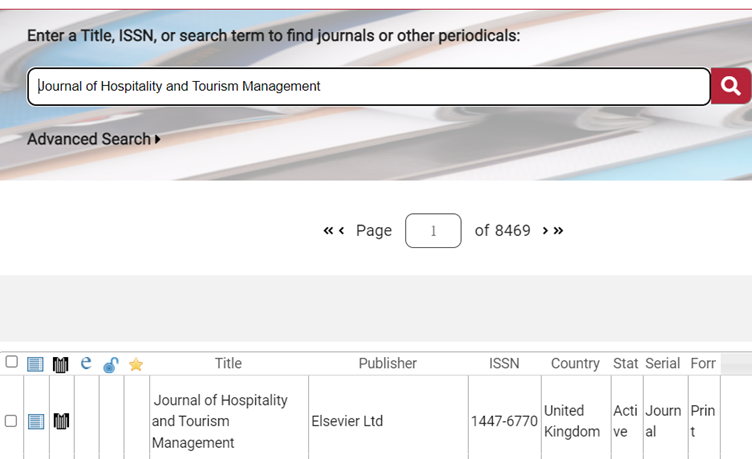

Most, but not all, academic journals use the peer review process to check the quality of articles before publication. There are several ways to check if the article you are interested in has been peer reviewed. One way is to go to the home page of the journal, where you will usually find information about the journal’s peer review process. Here is an example from the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management (select “Guide for authors”)

Peer review

This journal operates a double anonymized review process. All contributions will be initially assessed by the editor for suitability for the journal. Papers deemed suitable are then typically sent to a minimum of two independent expert reviewers to assess the scientific quality of the paper.

Source: https://www.elsevier.com/journals/journal-of-hospitality-and-tourism-management/1447-6770/guide-for-authors

If you cannot find this type of statement, then you should begin to have doubts about whether the articles in the journal are peer reviewed or not.

Another way to check if an academic journal uses the peer review process is to visit Ulrichsweb Global Serial Directories . Enter the name of the journal in the search bar and you will see if it is peer reviewed. This is the example for Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management

How to find out the ranking of an academic journal

When you access the main search bar on the library database, make sure you check the “peer reviewed” box on the left-hand side:

Please consult the library produced document How to identify reliable sources?

- Coronavirus Updates

- Education at MUSC

- Adult Patient Care

- Hollings Cancer Center

- Children's Health

Biomedical Research

- Research Matters Blog

- NIH Peer Review

NIH announces the Simplified Framework for Peer Review

The mission of NIH is to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and to apply that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability . In support of this mission, Research Project Grant (RPG) applications to support biomedical and behavioral research are evaluated for scientific and technical merit through the NIH peer review system.

The Simplified Framework for NIH Peer Review initiative reorganizes the five regulatory criteria (Significance, Investigators, Innovation, Approach, Environment; 42 C.F.R. Part 52h.8 ) into three factors – two will receive numerical criterion scores and one will be evaluated for sufficiency. All three factors will be considered in determining the overall impact score. The reframing of the criteria serves to focus reviewers on three central questions they should be evaluating: 1) how important is the proposed research? 2) how rigorous and feasible are the methods? 3) do the investigators and institution have the expertise/resources necessary to carry out the project?

• Factor 1: Importance of the Research (Significance, Innovation), scored 1-9

• Factor 2: Rigor and Feasibility (Approach), scored 1-9

• Factor 3: Expertise and Resources (Investigator, Environment), to be evaluated with a selection from a drop-down menu

o Appropriate (no written explanation needed)

o Identify need for additional expertise and/or resources (requires reviewer to briefly address specific gaps in expertise or resources needed to carry out the project)

Simplifying Review of Research Project Grant Applications

NIH Activity Codes Affected by the Simplified Review Framework.

R01, R03, R15, R16, R21, R33, R34, R36, R61, RC1, RC2, RC4, RF1, RL1, RL2, U01, U34, U3R, UA5, UC1, UC2, UC4, UF1, UG3, UH2, UH3, UH5, (including the following phased awards: R21/R33, UH2/UH3, UG3/UH3, R61/R33).

Changes Coming to NIH Applications and Peer Review in 2025

• Simplified Review Framework for Most Research Project Grants (RPGs )

• Revisions to the NIH Fellowship Application and Review Process

• Updates to NRSA Training Grant Applications (under development)

• Updated Application Forms and Instructions

• Common Forms for Biographical Sketch and Current and Pending (Other) Support (coming soon)

Webinars, Notices, and Resources

Apr 17, 2024 - NIH Simplified Review Framework for Research Project Grants (RPG): Implementation and Impact on Funding Opportunities Webinar Recording & Resources

Nov 3, 2023 - NIH's Simplified Peer Review Framework for NIH Research Project Grant (RPG) Applications: for Applicants and Reviewers Webinar Recording & Resources

Oct 19, 2023 - Online Briefing on NIH’s Simplified Peer Review Framework for NIH Research Project Grant (RPG) Applications: for Applicants and Reviewers. See NOT-OD-24-010

Simplifying Review FAQs

Upcoming Webinars

Learn more and ask questions at the following upcoming webinars:

June 5, 2024 : Webinar on Updates to NIH Training Grant Applications (registration open)

September 19, 2024 : Webinar on Revisions to the Fellowship Application and Review Pro

Categories: NIH Policies , Research Education , Science Communications

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NATURE INDEX

- 01 May 2024

Plagiarism in peer-review reports could be the ‘tip of the iceberg’

- Jackson Ryan 0

Jackson Ryan is a freelance science journalist in Sydney, Australia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Time pressures and a lack of confidence could be prompting reviewers to plagiarize text in their reports. Credit: Thomas Reimer/Zoonar via Alamy

Mikołaj Piniewski is a researcher to whom PhD students and collaborators turn when they need to revise or refine a manuscript. The hydrologist, at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, has a keen eye for problems in text — a skill that came in handy last year when he encountered some suspicious writing in peer-review reports of his own paper.

Last May, when Piniewski was reading the peer-review feedback that he and his co-authors had received for a manuscript they’d submitted to an environmental-science journal, alarm bells started ringing in his head. Comments by two of the three reviewers were vague and lacked substance, so Piniewski decided to run a Google search, looking at specific phrases and quotes the reviewers had used.

To his surprise, he found the comments were identical to those that were already available on the Internet, in multiple open-access review reports from publishers such as MDPI and PLOS. “I was speechless,” says Piniewski. The revelation caused him to go back to another manuscript that he had submitted a few months earlier, and dig out the peer-review reports he received for that. He found more plagiarized text. After e-mailing several collaborators, he assembled a team to dig deeper.

Meet this super-spotter of duplicated images in science papers

The team published the results of its investigation in Scientometrics in February 1 , examining dozens of cases of apparent plagiarism in peer-review reports, identifying the use of identical phrases across reports prepared for 19 journals. The team discovered exact quotes duplicated across 50 publications, saying that the findings are just “the tip of the iceberg” when it comes to misconduct in the peer-review system.

Dorothy Bishop, a former neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, UK, who has turned her attention to investigating research misconduct, was “favourably impressed” by the team’s analysis. “I felt the way they approached it was quite useful and might be a guide for other people trying to pin this stuff down,” she says.

Peer review under review

Piniewski and his colleagues conducted three analyses. First, they uploaded five peer-review reports from the two manuscripts that his laboratory had submitted to a rudimentary online plagiarism-detection tool . The reports had 44–100% similarity to previously published online content. Links were provided to the sources in which duplications were found.

The researchers drilled down further. They broke one of the suspicious peer-review reports down to fragments of one to three sentences each and searched for them on Google. In seconds, the search engine returned a number of hits: the exact phrases appeared in 22 open peer-review reports, published between 2021 and 2023.

The final analysis provided the most worrying results. They took a single quote — 43 words long and featuring multiple language errors, including incorrect capitalization — and pasted it into Google. The search revealed that the quote, or variants of it, had been used in 50 peer-review reports.