- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Merit or Inherit: How to Approach Succession in a Family Business

Both have risks. Here’s how to strike the right balance.

One of the most critical questions facing family businesses is how to treat the next generation. They are clearly different from other employees, as current or potential owners of the company, whose wealth and reputation are on the line. On the flip side, most parents rightfully worry that providing too many unearned advantages undermines not only the next generation’s work ethic, but the soul of the company. In answering this question, families often default to one extreme or another: giving the next generation special treatment that doesn’t hold them accountable to the same standards as other employees (the “inherit model”) or requiring them to earn everything they get (the “merit model”). This article describes a path that blends elements of both, and which is far more likely to set family members up to succeed.

“Some people are born on third base and go through life thinking they hit a triple.” This quote, often attributed to NFL football coach Barry Switzer, perfectly captures what many people think about family businesses. Family members are given jobs, promotions, and salaries that they would never have achieved without their name being on the front door. As one non-family executive put it, “He’s the COO of the company — the child of the owner.”

- JB Josh Baron is a co-founder and partner of BanyanGlobal Family Business Advisors and a Visiting Lecturer in Executive Education at Harvard Business School. He is a co-author of The Harvard Business Review Family Business Handbook (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021).

Partner Center

Balancing Succession In Family Businesses: Merit Or Inherit Approach

- September 20, 2023

- Accountability , Business Strategy & Innovation , Family business , Leadership , Motivation , Perception , Strategic planning , Succession planning , Workplace

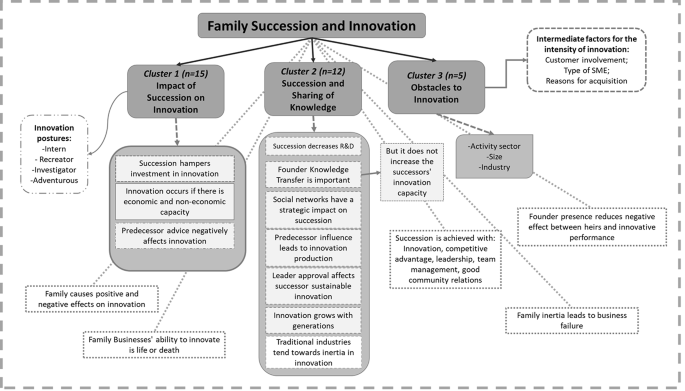

Succession planning plays a crucial role in family businesses, as it facilitates a smooth transition of leadership, preserves the family legacy and wealth, and reduces conflicts and power struggles. However, selecting the appropriate approach to succession is a complex task. The inherit model, which grants special privileges to family members, can result in a lack of accountability, erosion of work ethic, and resentment from non-family employees. Conversely, the merit model, which holds family members to the same standards as other employees, promotes fairness and equality but may face difficulties in retaining non-family talent. Therefore, a balanced approach that combines elements of both models is recommended. This approach acknowledges the unique position of family members, establishes clear expectations and performance metrics, provides development opportunities, and ensures a fair balance between merit and family ties in terms of rewards. By adopting a balanced approach, family businesses can motivate family members, uphold company values, attract non-family talent, enhance reputation, and strengthen family cohesion. Strategies for implementing a balanced succession plan include open communication, role definition, governance structure establishment, leadership development investment, and seeking external advice. However, caution must be exercised to avoid potential pitfalls such as relying excessively on unqualified family members and neglecting the concerns of non-family employees. Ultimately, finding the right balance, tailoring the approach to the family’s specific needs, and continuously evaluating and adjusting the succession plan are critical for the long-term success and sustainability of the business.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Succession planning in family businesses is important for smooth leadership transition, preserving family legacy and wealth, mitigating conflicts, and allowing for long-term strategic planning.

- Treating the next generation in family businesses involves balancing special treatment and accountability, while avoiding erosion of work ethic, threat to company culture, resentment from non-family employees, and risk of nepotism and favoritism.

- The inherit model provides unearned advantages to family members, lacks accountability and performance standards, and can negatively impact the company’s reputation and ability to attract non-family talent.

- The merit model holds family members to the same standards as other employees, promotes a strong work ethic, fairness, and equality, and avoids favoritism and nepotism. Blending the inherit and merit models involves recognizing the unique position of family members, establishing clear expectations and performance metrics, providing development opportunities, and balancing rewards based on merit and family ties.

Importance of Succession Planning

Succession planning in family businesses is crucial as it ensures the smooth transition of leadership, preserves the family legacy and wealth, mitigates potential conflicts and power struggles, allows for long-term strategic planning, and increases the chances of business continuity. However, family businesses face unique challenges in succession planning. These challenges include balancing the needs and expectations of family members, addressing conflicts and power struggles, and ensuring the selection of capable successors. Succession planning strategies for family businesses involve identifying potential successors early on, providing them with appropriate training and development opportunities, and establishing clear criteria and processes for selecting the next leader. Additionally, family businesses may benefit from seeking external advice and expertise to ensure objectivity in the decision-making process. By addressing these challenges and implementing effective succession planning strategies, family businesses can ensure a smooth transition of leadership and long-term sustainability.

Challenges in Treating the Next Generation

Challenges arise when considering the treatment of the next generation in the context of family business dynamics. One of the challenges is the potential erosion of work ethic among the next generation. The special treatment given to family members may create a sense of entitlement and reduce their motivation to work hard and earn their success. This can have a negative impact on the overall work culture and productivity of the company. Additionally, there may be resentment from non-family employees who perceive favoritism and nepotism within the organization. This can lead to a decrease in morale and commitment among non-family employees, affecting their job satisfaction and overall performance. Therefore, it is important for family businesses to address these challenges and find a balance between treating family members fairly and maintaining a productive and inclusive work environment.

The Inherit Model

The Inherit Model in family business dynamics involves providing unearned advantages to family members, which can result in a lack of accountability and performance standards, potential negative impact on the company’s reputation, difficulty in attracting and retaining non-family talent, and an increased likelihood of an entitlement mindset.

- Unearned advantages: Family members may receive preferential treatment and benefits without having to demonstrate the same level of competence or achievement as non-family employees.

- Lack of accountability and performance standards: When family members are given special treatment, they may not be held to the same standards as other employees, leading to a lack of accountability and potential underperformance.

- Negative impact on reputation: The perception of nepotism and favoritism can damage a company’s reputation, making it more challenging to attract and retain external talent and stakeholders.

- Difficulty in attracting and retaining non-family talent: Non-family employees may feel discouraged or resentful when they perceive that family members are receiving preferential treatment, leading to difficulties in attracting and retaining talent from outside the family.

- Increased likelihood of an entitlement mindset: By receiving unearned advantages, family members may develop an entitlement mindset, expecting privileges and benefits without having to earn them based on merit.

The Merit Model

A key aspect of the alternative model in family business dynamics involves holding family members to the same standards as other employees, promoting fairness and equality in the workplace, and fostering a culture of meritocracy. The merit model emphasizes the importance of treating family members as employees and not providing them with unearned advantages. By holding family members to the same standards as other employees, it promotes fairness and equality in the workplace. This approach encourages a strong work ethic and a sense of achievement among family members. By fostering a culture of meritocracy, it avoids perceptions of favoritism or nepotism and ensures transparency and fairness in decision-making. This model also helps in attracting and retaining non-family talent by establishing a level playing field for all employees.

Blending Inherit and Merit Models

Blending the principles of inheritance and meritocracy in family business succession planning involves recognizing the unique position of family members and establishing clear expectations and performance metrics. This approach aims to strike a balance between providing opportunities based on family ties and rewarding individuals based on their merit and performance. To effectively blend these models, family businesses can consider the following strategies:

Performance evaluation: Implement a fair and transparent performance evaluation system that holds family members accountable for their contributions to the business. This ensures that promotions and rewards are based on merit rather than solely on family ties.

Developmental opportunities: Provide development opportunities such as mentorship programs, training, and access to external networks. This allows family members to enhance their skills and competencies, ensuring that they are well-prepared to contribute to the business based on their own merit.

Balancing rewards: Establish a system that balances rewards based on both merit and family ties. This can involve linking compensation and benefits to performance outcomes, while also considering the long-term sustainability and well-being of the family.

Ensuring fairness: Maintain transparency and fairness in decision-making processes related to succession planning. This helps to address concerns of favoritism or nepotism, and fosters a culture of meritocracy within the family business.

Benefits of a Balanced Approach

Implementing a balanced approach in family business succession planning offers several benefits. Firstly, it motivates family members to earn their success by holding them to the same standards as non-family employees. This fosters a strong work ethic and a sense of achievement, ensuring that family members are driven to contribute to the success of the business. Secondly, a balanced approach preserves company values and culture. By maintaining a focus on merit and performance, the business can uphold its core principles and traditions. Furthermore, this approach attracts and retains non-family talent, as it demonstrates a commitment to fairness and equality in the workplace. This contributes to enhancing the reputation and credibility of the business, as it is seen as a professional and merit-based organization. Finally, a balanced approach strengthens family cohesion and harmony by minimizing the risk of favoritism and nepotism, promoting transparency and fairness in decision-making processes.

Strategies for Implementing a Balanced Succession Plan

Engaging in open and honest communication is a crucial strategy for the successful implementation of a balanced succession plan in family businesses. To evoke an emotional response in the audience, consider the following sub-lists:

Engaging stakeholders:

- Involving family members in the decision-making process fosters a sense of ownership and commitment.

- Seeking input from key employees and external advisors helps gain diverse perspectives and expertise.

- Regularly communicating the succession plan’s progress and milestones creates transparency and builds trust.

Evaluating performance metrics:

- Establishing clear performance metrics for family members ensures accountability and merit-based advancement.

- Regularly reviewing and assessing performance against these metrics allows for continuous improvement and development.

- Recognizing and rewarding achievements based on objective performance measures reinforces a culture of fairness and equality.

Case Studies: Successful Family Business Succession

The implementation of a balanced succession plan in family businesses requires careful consideration and strategic decision-making. Examining case studies of successful family business successions can provide valuable insights and lessons learned for achieving long-term sustainability. These case studies highlight the strategies and approaches implemented by companies to ensure a smooth transition of leadership and preserve family dynamics. By analyzing these examples, valuable lessons can be gleaned regarding the importance of open and honest communication, the establishment of clear roles and responsibilities, and the necessity of professional management practices. Successful family business successions demonstrate the positive outcomes that can be achieved when a balanced approach is taken, including enhanced reputation and credibility, the ability to attract and retain non-family talent, and the strengthening of family cohesion and harmony. These case studies serve as a guide for family businesses seeking to navigate the complexities of succession planning while ensuring the long-term success and sustainability of their ventures.

Potential Pitfalls to Avoid

Potential pitfalls to avoid in the implementation of a balanced succession plan in family businesses include over reliance on unqualified family members, neglecting conflicts and power struggles, lacking transparency in decision-making, disregarding non-family employees’ concerns and contributions, and underestimating the importance of professional management practices. One potential pitfall is over reliance on family members without proper qualifications. This can lead to a lack of expertise and competency in key positions, which may hinder the growth and success of the business. Additionally, ignoring non-family employees’ concerns can create a sense of resentment and disengagement among the workforce. It is important to address conflicts and power struggles within the family and the organization to maintain a harmonious and productive work environment. Transparency in decision-making is crucial to build trust and ensure fairness. Lastly, underestimating the importance of professional management practices can hinder the long-term success and sustainability of the business.

Finding the Right Balance

One key aspect to consider in achieving a balanced succession plan for family businesses is finding the optimal equilibrium between the qualifications and capabilities of family members and the need for professional management practices. This requires a holistic evaluation of the succession plan to ensure long-term sustainability. Succession plan evaluation involves assessing the qualifications, skills, and experience of family members to determine their suitability for leadership positions. It also involves considering the need for professional management practices, such as hiring external talent or implementing governance structures. Long-term sustainability assessment involves evaluating the potential impact of the succession plan on the business’s ability to adapt to changing market conditions and maintain its competitive advantage. By finding the right balance between family qualifications and professional management practices, family businesses can ensure a smooth transition of leadership while maintaining long-term sustainability.

As we continue to explore the topic of balancing succession in family businesses, the focus now shifts to managing family dynamics and ensuring fairness and equality within the organization. This is a crucial aspect of succession planning as it helps to maintain harmony within the family while also promoting a level playing field for all employees.

Key considerations in managing family dynamics and ensuring fairness and equality include:

- Establishing clear communication channels to address conflicts and concerns

- Implementing fair and transparent decision-making processes

- Providing equal opportunities for professional development and advancement

- Creating a culture of respect and inclusivity

Frequently Asked Questions

How can a balanced succession approach benefit both family members and non-family employees in a family business.

A balanced succession approach in a family business benefits both family members and non-family employees by promoting fairness, motivating family members to earn their success, attracting and retaining talent, enhancing reputation, and preserving company values and culture.

What are some potential challenges that may arise when implementing a balanced succession plan in a family business?

Some potential challenges that may arise when implementing a balanced succession plan in a family business include conflicts and power struggles, lack of transparency in decision-making, neglecting non-family employees’ concerns, and ignoring professional management practices.

Can you provide examples of successful family businesses that have effectively blended the inherit and merit models of succession?

Examples of successful family businesses that have effectively blended the inherit and merit models of succession include Ford Motor Company and Walmart. This approach benefits by motivating family members to earn their success while preserving company values and attracting non-family talent.

How can open and honest communication help facilitate a smooth transition of leadership in a family business?

Open and honest communication plays a crucial role in facilitating a smooth transition of leadership in a family business. It helps build trust, align expectations, and address any concerns or conflicts, ensuring a more seamless and successful succession process.

What are some key factors that should be considered when tailoring a succession plan to the unique needs and dynamics of a family business?

Factors to consider when tailoring a succession plan to the unique needs and dynamics of a family business include understanding the family’s values and culture, identifying suitable successors, addressing conflicts, ensuring transparency, and promoting professional management practices.

Family Business Succession Planning: The Definitive Guide & FAQs

Family business succession planning can be tiring and exhausting. Our definitive guide provides answers to all the questions about succession planning, including when to start, who to involve, and the dangers of getting it wrong.

Succession is an emotional and exhausting time for many family businesses. If handled incorrectly, it can have dire consequences for the reputation and stability of a firm. Statistics bear this out. According to research, roughly 75 percent of all businesses fail to survive past the first generation – and more than 85 percent fail by the third generation.

When succession events take place, the result can go one of two ways: the growth of your family’s business or its slow terminal decline. An ill-prepared plan, or even worse, a non-existent plan, could lead to the decline in value of your family business – and possibly even its collapse.

Our services

There is a huge amount at stake. So, it is important to create a robust plan that can see your business sail smoothly into its next chapter, where it can grow in the careful hands of your successors.

This guide provides an overview of all the key questions that families may ask as they start to think about the succession process – as well as a backgrounder on all the fundamental concepts that underlie a successful succession process.

What is succession planning?

Does a succession event happen all at once, does management and ownership have to be transitioned at the same time, how is succession in a family business different to other businesses, are next generation members part of succession discussions, what is leadership succession planning, do i only need to start thinking about succession planning when i’m ready to retire, are other business families taking succession planning seriously, why is succession planning important, what advisors are usually involved in the succession process, is there any excuse for not preparing for succession amongst business families, why don’t more families start planning early, how can you engage the next generation in the succession process, what should next-generation family members do to ensure smooth transition during succession events, in practical terms, what activities should the next-generation family members be involved in during succession, when should the current generation start to introduce younger members of the family, how early should you start to think about succession planning, how can you ensure that the succession process is staying on track, how can business families avoid the pitfalls of getting succession wrong, how do i ensure we have a strong internal family candidate to take over leadership of the company, how do i pick the right individual to take the business forwards, how do you resolve tensions between next-generation members, after you have decided on the next-generation leader, what needs to be done, how do you ensure you have made the right choice, who is responsible for developing a succession plan who should be involved, how can succession planning help you better articulate your values, what is a family charter, and how can it help with succession, what is the most common mistake when it comes to succession planning, what should you get to paper as part of succession planning, does succession planning only happen at the ceo level, how do succession events impact reputation, how do you control reputation risks during succession, how can you raise the profile of the next generation, is it best to just not say anything to stakeholders at all, what stakeholders should we think about during succession events, can succession events also improve a business’ reputation, can you give me an example of a succession event gone wrong, can you give an example of a smooth succession event, frequently asked questions (faqs).

Succession is the process of handing a business – or a large amount of wealth – down to the next generation. This means not only thinking about the future of business operations but considering the future of management and ownership.

The process can be a daunting and overwhelming task for founders who may find it difficult to hand over control of the day-to-day management of the family business.

No. ‘Succession’ is not simply the moment when the business changes hands – it is the long-term process of slow transition from one generation to the next. There is not a single moment when it happens. It is a gradual process.

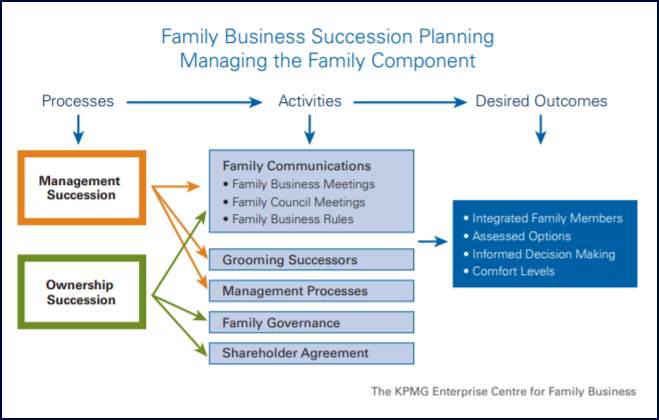

No. The handing over of control and management of the business does not necessarily mean the handing over of ownership – both transfers do not have to happen at the same time, and many advisors will recommend separating out those processes. In fact, these two different parts of the succession process could take place years apart.

In most cases, one generation will handover management of the business to the next generation first. Transitioning ownership might not take place until the last member of the current generation passes away.

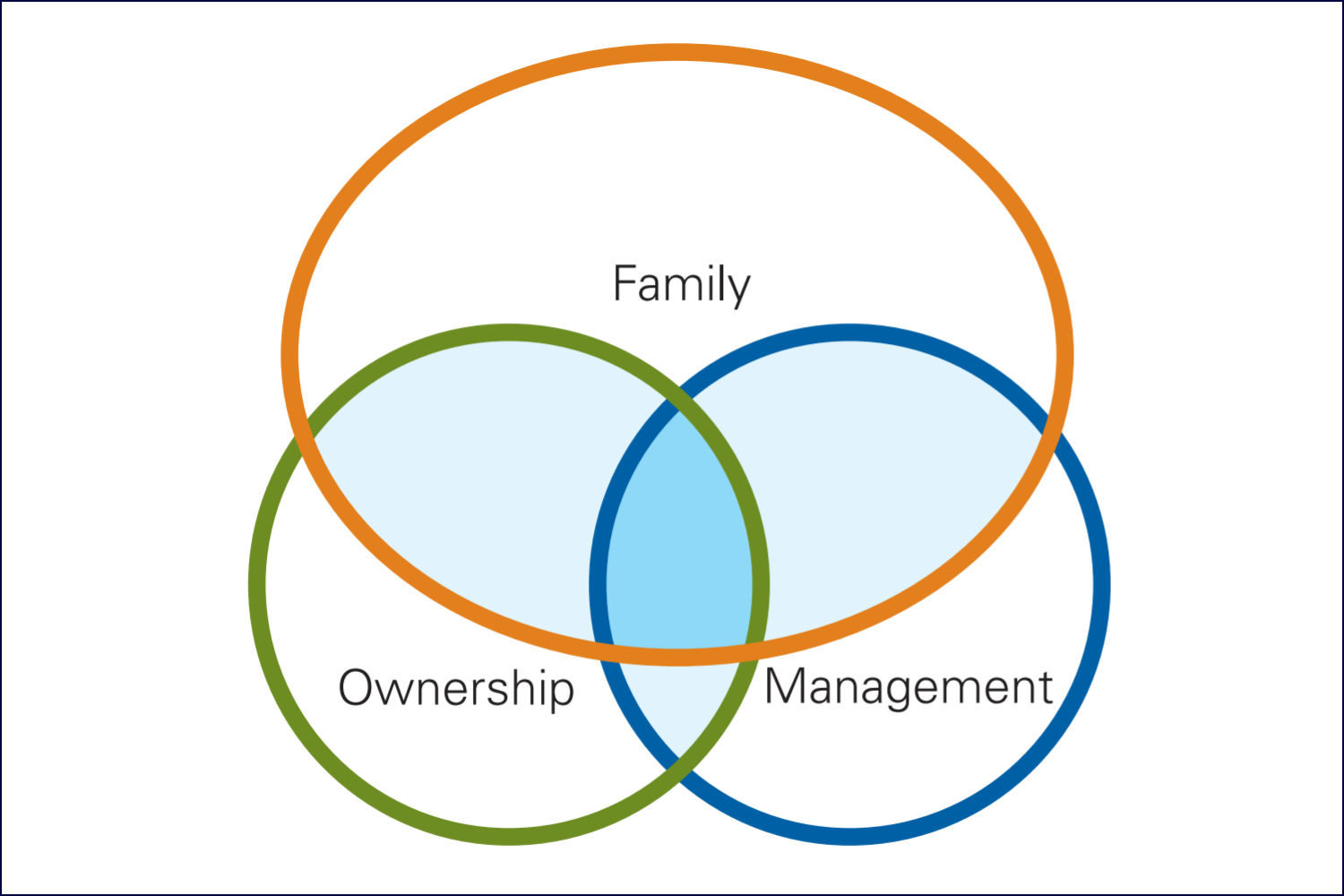

Venn diagram showing the overlap between family, business, and management. Source: KMPG Family Business Succession

Family businesses are noticeably different to other types of businesses. During succession events, complicated internal family dynamics are often at play – and these can lead to difficult, emotional, and challenging discussions amongst the family.

In many cases, the future of the business is not only a commercial decision but, instead, a deeper discussion about the family’s future itself: will they continue to lead the business? Will the family hire in new professional management? Will they sell the business? These are difficult, sometimes painful, questions that families need to ask when starting to think about succession.

Absolutely. Next-generation engagement is crucial to the success of any business’s succession planning programme. The next-generation members of the family – whether the immediate next generation or the generation below that – are the future of the company, and it’s important that their views about the direction of the business are properly represented in the process.

Younger family members may want to take the business in a different direction, prefer hiring professional management, or simply not feel up to taking the business forward. It’s important that the current generation know this because they start making decisions about the future.

‘Succession planning’ can also mean the process of identifying talent to lead a business in the future – this process applies to all businesses, and not just family businesses. For example, a publicly listed company will often undergo a process of identifying a list of candidates to takeover from an CEO when they step down or retire.

When researching succession planning, it is important for families and family businesses to distinguish between these two types of succession planning – it can be easy to confuse the two, which may lead to misunderstandings when talking about succession planning with partners, advisors, and peers.

Absolutely not. Succession events can take place completely unexpectedly, and it’s important that a family knows what to do in these unfortunate (and last-minute) circumstances. It may be that the current head of the family dies suddenly or, alternatively, that they are otherwise unable to run the business. This will be an exceptionally stressful time for the family, even without the added pressure of having to take difficult decisions around succession immediately.

Additionally, the succession process can take up to 20 years to complete successfully, so the earlier families start planning, the better.

Yes. Succession planning is a central focus of energy and anxiety amongst business families – because getting the process wrong can have long-term damaging impacts on the wealth of the family and the performance of their businesses. Research shows that nearly three in five families (57%) have started to draft a succession plan. On top of that, 67% say that succession planning and inheritance is their biggest business concern.

If the succession process isn’t handled well, it can have a hugely damaging impact on the financial affairs of the family and their businesses. A few of the potential implications:

- Next-generation family members not having the right skills to run the business effectively

- Banks and financial partners losing faith in the future of the business

- Employees not respecting the skills and capacity of the next generation to lead the business

- Lack of clarity amongst the family members about who will lead the business, resulting in interfamily disputes and conflict

- Weaker relationships between next-generation members and important partners, suppliers, and others

Ultimately, if the succession process is not handled in a professional and smooth way, it can result in a very poor outcome for the business. According to results, 70% of families report failure in intergenerational wealth transfers.

A family business could risk collapse without a strong succession plan. Source: PwC.

Business families may want to engage outside experts to help them prepare for the transition of the business to the next generation. These outside experts include:

- Lawyers to put in place structures to transition wealth effectively

- Financial advisors to help mitigate financial risk

- Family business consultants to help the family understand and navigate the risks of succession

- Reputation and public relations experts to help with communicating the succession event effectively

- Wealth managers

- Accountants

Not at all. Firstly, there is countless research to demonstrate the negative impact that a succession event can have on a family, their businesses, and its collective finances. Secondly, it is already known well ahead of time that the current generation will one day step aside and pass down the business – and the family’s collective wealth – to the next generation.

Maybe families are so ‘trapped’ in the day-to-day business that they forget to find the time to devote to succession. For many families, succession is always a topic that dropped to the bottom of the list – many families do not feel a sense of urgency, so it is always left until tomorrow.

On the other hand, many families know that discussions about succession could lead to difficult discussions about the future of the business and, potentially, even conflict. As a result, they would rather avoid these difficult discussions rather than confront – and resolve – them directly.

The family can encourage next-generation engagement through the following activities:

- Conducting family-wide meetings to discuss and decide the future of the business

- Including next-generation members in company Board meetings where succession and the future direction of the business is discussed as an agenda point

- Starting informal discussions about the future of the business around the dining room table

- Ensuring the presence of next-generational members in discussions with non-family members of staff about their own thoughts about the future of the business

The next-generation should build a hands-on, practical, and thorough understanding of all parts of the family business – and meet as many important partners as possible.

This will help tackle two potential risks of the succession process: firstly, the next generation not properly understanding all aspects of the business and how it operates, secondly, not having the strong and important relationships with partners and stakeholders that the current generation does.

In order to build a thorough understanding of the business as well as build strong relationships with partners, next-generational members might want to get involved in the following activities:

- Attend internal business meetings

- Work for short stints (3-6 months) in different departments of the business

- Participate in the preparation of financial documents and Annual Reports

- Attend meetings with important external stakeholders, such as banks, business partners, suppliers, regulators, and others

- Take a leadership position within a particular division

- Work for a short stint in partner business or supplier

- Build experience in another company in the same industry as the family business

- Take a course or degree that aligns with the family business’ industry

The components of successful family business succession planning. Source: KPMG Family Business Succession Planning.

As soon as possible. Founders can sometimes hold back on introducing younger generations to the business for fear they are not ‘old enough’, yet it is truly never too early to introduce them. Familiarity takes a long time to build, so the earlier that this process starts the earlier stakeholders will build confidence and respect for the next generation.

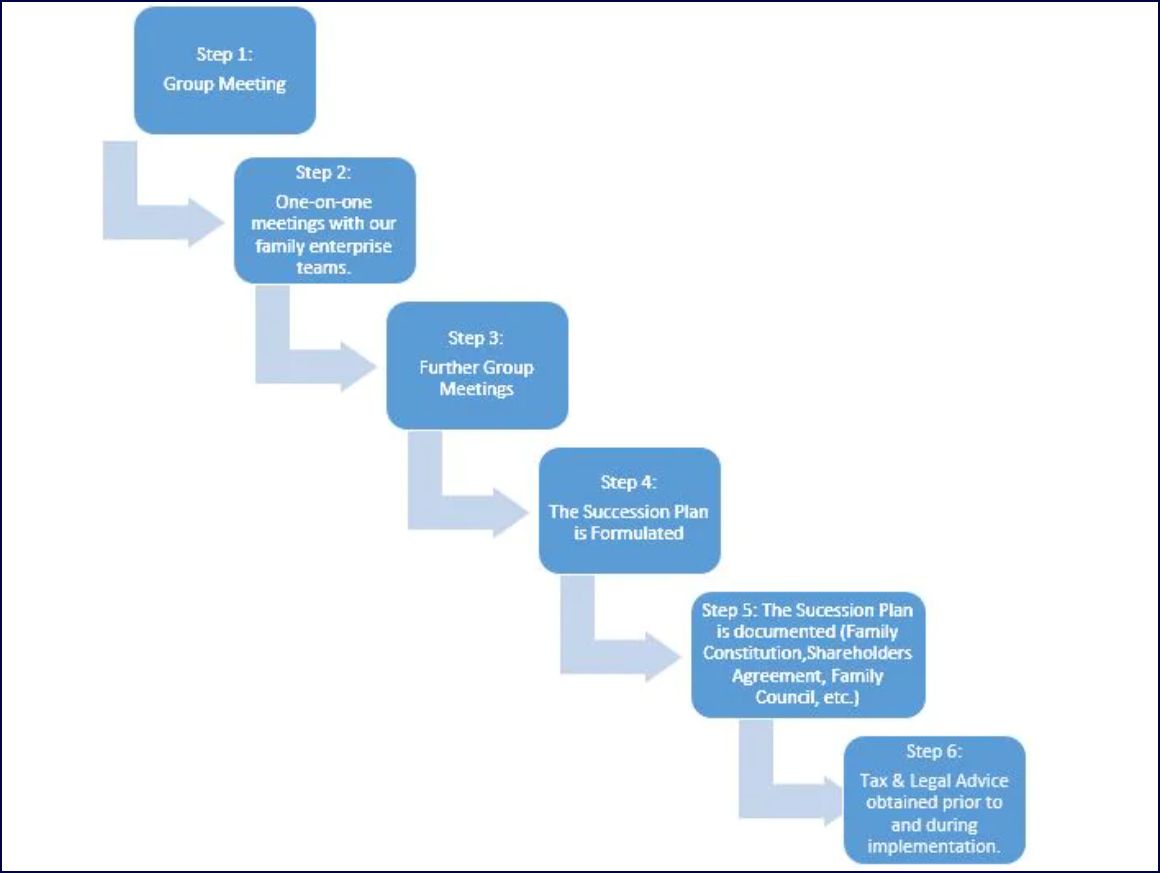

Within family business, it is important to start thinking about your succession plan up to 20 years in advance – this allows for the correct structures to be put in place. This might include taking steps to introduce the next generation of leaders to customers, shareholders, suppliers, and so on.

Regular meetings and ongoing communication are essential. It is sensible to have a quarterly meeting specifically about succession planning. These meetings might have to become more frequent the closer you get to the actual transition.

At each meeting, it is important to put to paper the next steps that need to be taken to further prepare the family for succession, whether that is getting the next-generation more involved, taking on further professional advice, or otherwise.

The family can also review the steps that were agreed in the last meeting to see if progress is being made – and the business and the family are moving in the right direction.

One of the best ways to avoid mistakes is to talk to other business families who have navigated the succession process effectively. On one hand, this might mean taking the time to talk to people in your existing network who have managed this process successfully. On the other hand, it might mean tapping into pre-existing networks for business families – like the IFB or Family Business United – where people share best practice.

Follow a step-by-step process when carrying out your succession plan. Source: Deloitte.

Firstly, it is important to understand exactly what makes the current leader of the business successful – this will usually be as a result of the skills, experience, commanding presence, and relationships that the current management bring to the business.

Now, sit down and thoughtfully answer the following questions about the current leadership:

- In precise terms, what are the current leader’s responsibilities?

- Who does the current leader depend on within the business?

- What previous experiences makes the current leader successful?

- What technical skills are essential to the current leader’s success, i.e., accountancy, pricing, supply-chain, marketing, etc?

- What softer skills are essential to the current leader’s success, i.e., management capacity, communications, etc?

- What specific relationships are essential to the current leader’s success, i.e., banks, partners, advisers, suppliers, etc?

Secondly, put to paper a ‘plan of action’ to ensure that the appropriate next-generation family member who will be taking over the business can develop those same skills, experiences, and networks that made the current leader successful. This plan of action might be a five-year pathway of technical education, experience, and exposure.

For a family business with multiple next-generation family members, this is a very difficult question, but it’s important to go through a fair and balanced process – and communicate the answer clearly across the family as early as possible.

It is not beneficial to any of the next-generation family members or the business itself for there to be an aggressive, hostile battle for the position. This could lead to a toxic work environment, one-upmanship, and other destructive behaviour.

Families should go through an objective and balanced decision-making process – and work hard to ensure that the process is not clouded by emotion. Families should answer the following questions:

- Which family members are genuinely interested in leading the business in the future?

- Which family members have existing technical skills?

- Which family members have naturally strong soft skills, and enjoy leadership itself?

- Which family member already commands respect, trust, and confidence of staff members and external partners?

Ask yourself which family members have the genuine interest and skills required to succeed you. Source: Insperity.

When choosing the next-generation leader of the business, there may be a degree of healthy competition between next-generation members. However, it is very easy for this healthy competition to descend into toxic, hostile in-fighting. Resolving these disputes will require emotional sensitivity and effective communication.

Usually, the best way to resolve these disputes is to emphasise that all next-generation members of the family that they each bring their own unique, compelling skillsets to the business – and, ultimately, everyone is pulling in the same direction: to create a growing, sustainable, and successful business that benefits everyone financially.

It is also important to clearly communicate to the next generation why different choices have been made – and show objective criteria for making these decisions.

Communicate the decision sensitively to all next-generation members. At this point, it is also important to stress that there are no guarantees, and the situation may change.

Investment in the professional development of those people who you have selected to lead the company into the future should now be stepped up. This is a good opportunity for your next-generation family members to gain additional knowledge and experience – you may consider connecting them with mentors within (and outside) the business who can boost their skills.

Use any opportunity you might have to ‘trial run’ your plan and reconfirm your choices. This might be having a next-generation member assume some responsibilities of a more senior member who is on leave or taking control of a certain division of the business. The opportunity enables the individual to gain fresh knowledge and experience and, importantly, enables you to assess if that person might need some additional training and support.

The owners and top management of a family business are responsible for developing and implementing a succession plan. It’s essential that the leadership of the business is involved at all stages. The task cannot be outsourced solely to outside advisors or HR – instead, there needs to be buy-in at the very highest levels of the company. Without this commitment, succession will not work effectively.

While strategic decisions will be made at Board level, HR will typically be responsible for carrying out, monitoring, and implementing the process. This will be done with the full involvement of the CEO, other senior leaders, and the Board.

Succession planning also provides families with an important opportunity to articulate the values of the founder (or current generation of leadership), the family, and help to cultivate agreement on these values. These are the values that have enabled the business’ success over recent decades – and the values that the next generation will take forward into the future.

A family charter is a single, collectively agreed document that puts to paper a common understanding of key issues between a family. A family charter may codify the purpose of the family, the family’s values and aims, as well as articulate a very clear plan for the future of the business, including who is expected to take the business forward.

This can be very helpful during succession events because it spells out in crystal clear detail what the future looks like and expectations about the next generation. Getting collective buy-in for the document also mitigates against the risk of dispute, misunderstandings, and strategic drift.

Ultimately, the biggest mistake is the complete absence of a succession plan in the first place. A rushed approach to the succession planning process also has very damaging results. It is like going into a storm without a map, plan, or strategy. You run the serious risk of failure.

Be aware of the common mistakes when creating your family succession plan. Source: TRG Talent.

It’s important not to approach the succession planning process informally. It’s better to have a proper formal plan to paper, which will enable you to see problems, challenges, and opportunities.

Your succession plan should align with the strategic goals of your business and should include:

- A plan to ‘skill up’ the next generation of the family

- A plan to introduce the next generation to important stakeholders

- Explicit agreement of what specific roles and responsibilities next-generation family members will take on at the point of succession

- List of actions that will be undertaken in the case of a sudden transition

- A list of professional, non-family members and advisers with the knowledge, capacity and know-how to support the next generation when they take on the business

Absolutely not. A successful succession plan will span across all levels of your company. The current generation of the family may hold leadership and technical roles across the whole business, including marketing, HR, and accounting. There must be a clear plan to replace these people, either with next-generation members of the family – or newly recruited professional individuals.

A bumpy handover of a senior leader to a next-generation family member can severely impact the reputation of your organisation. The current leader of the business – especially if they are a first-generation entrepreneur who founded the company – are often the most recognised representative of the firm by employees, suppliers, banks, and other important stakeholders.

In fact, many important stakeholders might associate the business solely with that individual and believe the success of the company depends on them.

If stakeholders believe the business cannot stand on its own two feet once the first-generation member has stepped aside, you might start to see banks pulling in credit, long-standing loyal employees leaving, and suppliers ending their dealings with the company. This could lead to a collective crisis of confidence in the company – and the start of a vicious downwards cycle.

There are many ways to mitigate against the risk of a succession event leading to a crisis of confidence in the family business. These include:

- Prepare early . It is better to start planning earlier rather than later – sometimes this means beginning the planning process up to 20 years in advance.

- Prepare a crisis plan . In the event of an unexpected death or another crisis, the future and stability of the company can be thrown up in the air without a plan for how this event will be handled. Putting a plan together that includes prepared statements for all stakeholders is one way to get on the front foot.

- Raising the profile of the next generation. Start raising the profile of the next-generation and start lowering the profile of the current generation. As early as possible, start to build familiarity around the next generation of leaders of the firm.

The best way to raise the profile of your next-generation members is to proactively include them in more of your communications, public relations, and stakeholder engagement activity. Some examples that have worked for other families include:

- Including next-generation members in internal employee-focussed newsletters

- Adding a cover letter from a next-gen member to your Annual Report

- Allowing next-gen members to address staff in townhall meetings

- Letting next-gen member deliver investor briefings

- Including next-gen members as spokespeople in press releases

- Ensuring next-gen members are interviewed and seen in relevant trade publication

- Giving next-generation members visibility on the company website

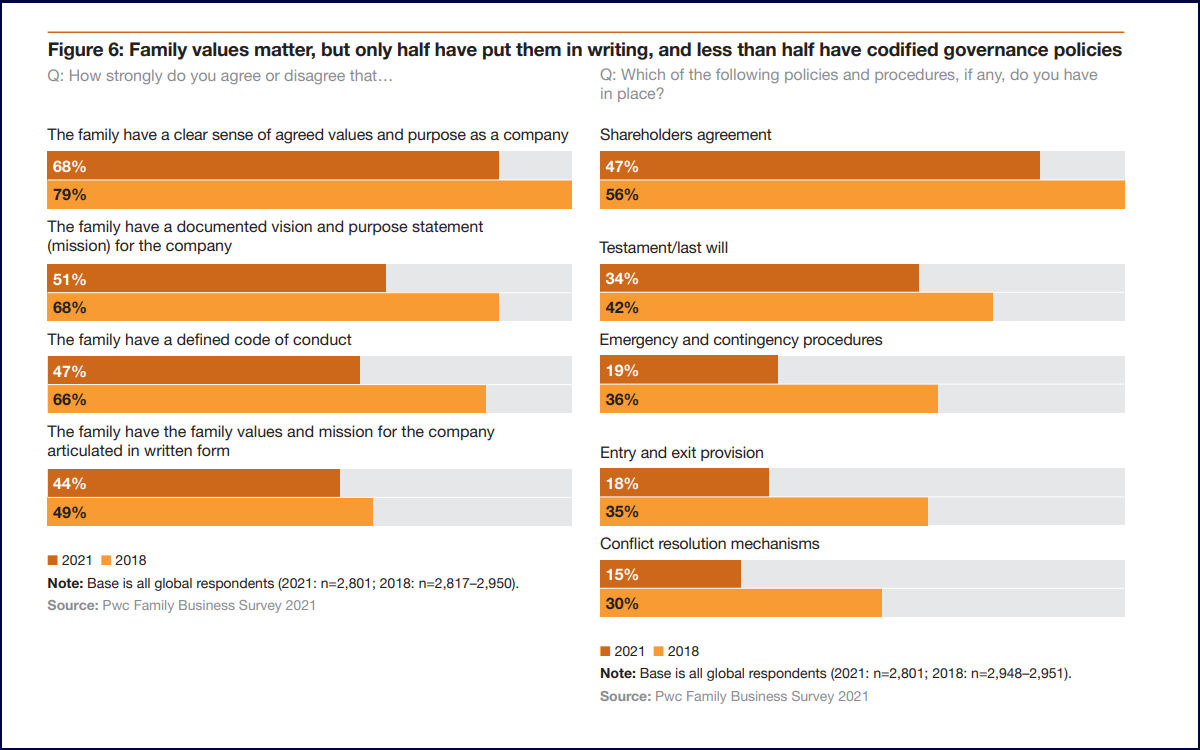

How many families have codified their values. Source: PwC Family Business Survey 2021

Absolutely not. Instinctively, some businesses might assume it is best not to say anything at all when it comes to a succession event. This is the wrong approach.

When companies ‘go silent’, they hope that important stakeholders will just not notice the transition – but they always do. Employees will start asking questions. So, will banks, suppliers, and others. It is best to answer those questions before they arise.

You should take the time to proactively list all the groups of people and individuals who you rely on to make your business a success. These will likely include:

- Banking partners

- Business partners and co-investors

- Local communities

- Policymakers

Absolutely. Succession isn’t all bad news. In fact, succession events are also opportune times to improve the brand and image of the company. Next-generation members of the family will often bring new skills and approaches to a business. For example, they might bring greater understanding of IT, digital, and social media marketing.

During the succession event, there is an opportunity to showcase to important stakeholders that the business is onboarding these important new skills that will help the business continue to grow into the future.

In 2021, the co-founder of cosmetics company Natura Siberica passed away unexpectedly without a clear plan for who was going to takeover the business. Following his death, a hostile, toxic battle broke out between various potential successors, including children from previous marriages and his widow. This led to several significant, high-profile lawsuits between different members of the family.

In August 2021, the media reported that 57 staff members quit and 101 left for a holiday in just 48 hours. This could potentially lead to a wider, broader crisis in confidence in the company – and a downwards vicious cycle that could damage its long-term value.

Usually if a succession event has been handled smoothly, we will not know about it. Instead, the business will have been handled over without attracting any untoward and unnecessary negative attention. Many of the oldest family businesses in the UK have been handed over in such a quiet and smooth way, including Hoare’s Bank, Folkes Holding, Shepherd Neame, Berry Bros & Rudd, Aspall Cyder, and many others.

Further reading

- Deloitte: Family business succession planning

- KPMG: Family Business Succession

- The Family Business Consulting Group: Family Business Succession

- Forbes: How To Make Family Business Succession Successful

- Davis Wright Tremaine: Succession Planning in a Family Business

- HBR: The Key to Successful Succession Planning for Family Businesses

Transmission Private publishes a monthly newsletter that tracks the future of reputation management for private clients.

Agree with our user data policy

- Evidence led

- Family focussed

- Digital first

Related Expertise: Leadership Development , Business Strategy , Corporate Strategy

Succeeding with Succession Planning in Family Businesses

The ten key principles.

March 25, 2015 By Vikram Bhalla and Nicolas Kachaner

For many family-owned businesses, succession planning is the proverbial “elephant in the room.” Despite recognizing the importance of selecting and preparing a successor, the leaders of a family business often do not give succession planning the attention it deserves.

In a recent survey by The Boston Consulting Group, family business leaders ranked succession as the second-most-important subject on the their minds, topped only by the closely related issue of achieving alignment among family members on critical topics. Even so, our research found that more than 40 percent of family businesses have not adequately prepared for succession during the past decade.

The consequences of not focusing on succession despite its obvious importance can be profound; a leadership void and the resulting discord can significantly undermine the company’s performance. Indeed, poorly planned successions are among the biggest value-destroying events for family-owned businesses.

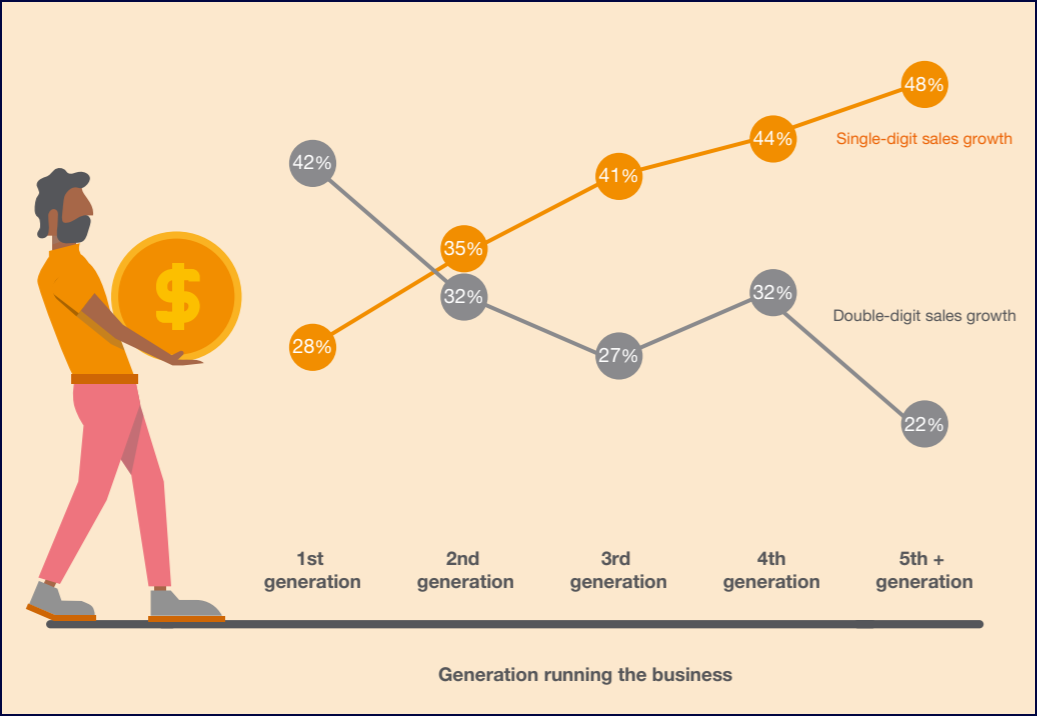

BCG’s research sheds light on the extent to which poorly planned successions can harm revenues, market capitalization, and margins. Although our study focused on family-owned businesses in India, the findings offer cautionary insights for companies in any country. We found a 14-percentage-point differential in revenue growth over two years when comparing family businesses that had planned transitions with those that had not. (See the exhibit.)

We also found a 28-percentage-point differential in market capitalization growth between companies that had planned transitions and those that had not. Moreover, unplanned transitions yielded EBITDA margins that after two years were more than 4 percentage points lower than those achieved by companies that successfully planned succession; margins remained below the trend line for the peer group for more than four years after unplanned transitions. Clearly, an enormous amount of value is destroyed by unplanned transitions, with potentially catastrophic consequences for the business.

A Difficult Subject to Discuss and Address Head-On

What lies behind the reluctance of many family-business leaders to openly discuss succession planning and tackle the challenges head-on? Succession planning sits at the intersection of family considerations, which typically involve emotions and feelings, and business considerations, which are typically driven by merit and economics. This juxtaposition of sentimental and financial concerns can make succession an especially complex topic.

Moreover, many incumbent leaders are unwilling to talk about relinquishing the helm, because their personal identity is often tightly linked to the family business itself. A charismatic founder having a strong personality, formidable capabilities, and a long record of managing all aspects of the business often casts a lengthy shadow over younger generations. In such cases, succession can be a nearly taboo subject that is difficult to broach.

Even when succession is high on the leadership agenda, family businesses face significant challenges to getting it right. First, they need to decide whether to select a successor from within or outside the family. Several family members may each aspire to take the reins, and talented nonfamily executives may also be interested in leading the company. Then, if the business designates a young family member as the successor, it must define a plan for how he or she will prepare for the role and gain acceptance as the leader by other family members and executives. Finally, the departing leader must be willing to let the successor emerge from under his or her shadow and take charge as planned.

Succeeding with Succession

Planning for a smooth succession starts with recognizing that it will be one of the most complicated transitions that a family business will experience. The family must also recognize that it is never too early to start discussing succession and that the costs of getting succession wrong will be nothing short of catastrophic for the business. These challenges mean that family members must focus strongly on succession planning, giving it their undivided attention on many occasions. Based on our experience advising family businesses on succession, we have identified ten principles that improve the chances of succeeding with succession.

Start early. Families may hesitate to plan succession because they are uncertain how the interests, choices, and decisions of different family members will play out over years or decades. But succession planning should start as soon as possible despite this uncertainty. Although things may change along the way, leaders can often anticipate the potential scenarios for how the family will evolve. Issues to consider when developing scenarios include the number of children in the next generation and whether those individuals are interested in the family business as a source of full- or part-time employment or purely as an investment. Families should also consider how the scenarios would be affected by marriages or the sudden demise of a family member or potential successor. It is important to plan a succession process and outcome that will work for the different foreseeable scenarios.

Set expectations, philosophy, and values upfront. Although setting expectations, philosophy, and values is central to many family-business issues, we have found that doing so is essential when it comes to succession planning and must be done up front, even if the specific mechanics of succession come later. In our experience, the family businesses that thrive and succeed across generations are those that possess a core philosophy and set of values linked not to wealth creation but to a sense of community and purpose.

Long before decisions will be made about specific potential successors, the family must agree on overarching issues such as whether family unity will take precedence over wealth creation, whether all branches of the family will have an equal ownership right and voice in decisions, and whether decisions will be based purely on merit and the best interests of the business. These guiding principles will provide the framework for more specific decisions.

Understand individual and collective aspirations. Understanding family members’ aspirations, individually and collectively, is critical to defining the right succession process. Leaders of the succession process should meet with family members and discuss their individual aspirations for involvement in the business. For example, does an individual want to work for the business or lead the business, or, alternatively, focus on the family’s philanthropic work? Or does an individual want to chart his or her own course outside of the business? The family’s collective aspirations can emerge from the effort to establish a philosophy and values. Does the family want its business to be the largest company in the industry? Is maintaining the business as a family-owned-and-operated company of paramount importance, or does the family want to relinquish operational responsibility in the coming years? Understanding these aspirations helps in managing expectations and defining priorities in the succession process.

Independently assess what’s right for the business. Although the best interests of the business and the family may seem indistinguishable to some family members, in reality the optimal decisions from the business’s perspective may differ from what family members want for themselves. This distinction makes it essential to consider what is right for the business independent of family preferences when developing a succession plan. It is therefore important to think about succession from a purely business perspective before making any adjustments based on family preferences. This allows leaders to be transparent and deliberate in the trade-offs they may have to make to manage any competing priorities.

Develop the successor’s capabilities broadly. A family business should invest in developing the successor’s capabilities and grooming him or her for leadership. The preparation should occur in phases starting at a young age—even before the successor turns 18.

The challenges of leading a family business are even greater than those faced by leaders of other businesses. In addition to leadership and entrepreneurship, a successor needs to develop values aligned with the family’s aspirations for the business and its role in society—capabilities that constitute stewardship of the company. Given the rapidly increasing complexity of business in the twenty-first century, we often strongly recommend that potential successors gain experience outside the family business in order to broaden their perspective.

Some of the best-managed family businesses have elaborate career-development processes for family members that are the equal of world-class talent-management and capability-building processes.

Define a clear and objective selection process. A company needs to define a selection process to implement its succession model—whether selecting a successor exclusively from the family or considering nonfamily executives as well. The selection process should be based on articulated criteria and delineate clear roles among family governance bodies and business leaders, addressing who will lead the process, propose candidates, and make decisions.

An early start is especially important if several family members are under consideration or the potential exists to divide the business to accommodate leadership aspirations. To obtain an objective perspective on which members of the younger generation have the greatest leadership potential, some families have benefited from the support of external advisors in evaluating talent and running the selection process.

It is important to note that the selection process, while critical, is the sixth point on this list. Points one through five are prerequisites for making the selection process itself more robust and effective.

Find creative ways to balance business needs and family aspirations. Striking the right balance between the business’s needs and family members’ aspirations can be complex. Addressing this complexity often calls for creative approaches—beyond the traditional CEO-and-chairperson model.

For example, the leader of one BCG client split his conglomerate into different companies, each to be led by one of his children; the split occurred without acrimony and in a planned, transparent manner. Beyond helping family members fulfill their aspirations, such a planned split can often greatly enhance value for the business. Another client systematically expanded its business portfolios as the family grew and tapped family members to take over the additions, thus ensuring that several members of the family had a role in the leadership of the businesses.

Stepping into an executive position is not the only way family members can contribute to the business or help the family live its values. As an alternative, family members can serve on the board of directors or take leading roles in the family office or its philanthropic activities.

Build credibility through a phased transition. Successors should build their credibility and authority through well-defined phases of a transition into the leadership role. They can start with a phase of shadowing senior executives to learn about their routines, priorities, and ways of operating. Next, we suggest acting more as a chief operating officer, managing the operations closely but still deferring to the incumbent leaders on strategic decisions. Ultimately, the successor can take over as the CEO and chairperson and drive the family business forward.

It is important to emphasize that the family member who assumes leadership of the business does not necessarily also become the head of the family, with responsibility for vision setting, family governance and alignment, and wealth management. The transition of family leadership can be a distinct process.

Each phase of the transition often takes between two and six months. The transition should be defined by clear milestones and commensurate decision rights. A sudden transition can be disruptive, which is especially harmful if the intent is to maintain continuity in the family business’s direction and strategy.

Ask departing leaders to leave but not disappear. Most leaders bring something distinctive to a family business. Holding onto this distinctiveness in a transition is essential but requires a delicate balance. Although departing leaders should relinquish managerial responsibility for the business, they should remain connected to one or two areas where they bring the truly distinctive value that made the family business successful under their guidance. However, the leaders should be involved in these activities through a formal process, rather than at their own personal preference and discretion. Departing leaders should stay available to guide the new leader if he or she seeks their advice.

To help leaders strike this balance and overcome their reluctance to let go, companies can create a “glide path” plan that sets out how they will turn over control in phases and transition into other activities while the successor assumes control and builds credibility.

Family businesses should also consider the need to adjust aspects of the company’s governance model when the departing leader hands over the reins. Although such adjustments can be made outside the context of succession, they often become particularly relevant after transitions to the second or third generation. A strong leader’s hands-on governance approach is often no longer sustainable for the next generation, creating the need to divide and formalize roles and institutionalize many business processes.

Motivate the best employees and foster their support. Managing the company’s most talented nonfamily executives is especially challenging during the succession process. The company needs to ensure that these executives have opportunities to develop professionally and take on new responsibilities and that morale remains high. Involving executives in the succession process can help to foster their support for the new leader. For example, they can be asked to serve as mentors for the successor or lead special projects relating to the succession. Surrounding the new leader with a strong and supportive senior team is a key ingredient for success, and the departing leader should ensure that such a team is in place.

Assessing the Status of Succession Planning Today

As an initial “health check” to assess the current status of their succession planning, family businesses should consider a number of issues:

- Has the family clearly articulated its values and the principles that will guide its decisions and succession process?

- Has the current leader committed to a fixed retirement date?

- Has the family evaluated the pipeline of leadership talent within its younger generation? Has it looked at potential leaders who come from within the business but not within the family?

- Has the company defined a succession model and determined the timing for selecting a successor so that he or she has a sufficient opportunity to prepare for the leadership role and build credibility before the current leader retires?

- Does the family understand how it will accommodate the aspirations of family members not selected for leadership roles, in order to maintain harmony and avoid discord during the transition to new leadership?

In many cases, family businesses will find that the answers to questions like these indicate the need to devote much more time and attention to succession planning. Most important, the current leader, other family members, and the top management team will need to begin having an open and candid discussion about succession-related issues to enable the business to thrive for generations to come. These discussions are never easy, but they are essential. Getting succession wrong can be an irreversible and often fatal mistake for a family business.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

Mumbai - Nariman Point

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Everything that you need to know to start your own business. From business ideas to researching the competition.

Practical and real-world advice on how to run your business — from managing employees to keeping the books.

Our best expert advice on how to grow your business — from attracting new customers to keeping existing customers happy and having the capital to do it.

Entrepreneurs and industry leaders share their best advice on how to take your company to the next level.

- Business Ideas

- Human Resources

- Business Financing

- Growth Studio

- Ask the Board

Looking for your local chamber?

Interested in partnering with us?

Start » strategy, how to write a family business succession plan.

Whether your family owned business is a Main Street mom-and-pop or a Wall Street powerhouse, a well-written succession plan can be crucial to the future success of both the company and the family.

If you don’t have a succession plan in place, you’re not alone. According to PwC , only 18% of America’s family-owned businesses have a documented strategy for handing over the reins.

Of course, this isn’t just any business we’re talking about. It’s your business, and your family’s. ‘Those without a plan’ is not the group you want to be in. Like so many other important tasks, the hardest thing is getting started. Here are some key steps.

Choose the right business structure

Many small businesses begin life as sole proprietorships or partnerships. If you launched that way, it may be time to take another look at your structure. As The Balance points out, forming a corporation will legally separate you from your business—a key step toward a smooth transfer, even if that transfer turns out to be a sale to a non-family entity.

The right business structure can set your successors up for a reduced tax burden. And, if you desire to remain a sole proprietor, you can still make your wishes for the business known by including them in your estate planning.

[Read: Getting Ready to Launch? How to Choose the Right Business Structure ]

Have a mission statement and a set of core values

You’re not just passing along some office chairs and a customer list. The big idea that launched your business is your why, and it’s what separates your family-owned business from the competition. Knowing you have clearly communicated your vision will help others understand their place in the organization and give you confidence to make the difficult decisions ahead.

According to a report from Deloitte , as time passes, the importance of family values increases, and may be the one thing that binds successive generations together. Stated family values can act as a roadmap for decision making, a magnet for like-minded employees and business partners, and a metric by which to measure success.

[Read: Writing a Mission Statement: A Step by Step Guide ]

Succession planning is not the time to make assumptions about what the next generation wants and is capable of.

Choose your successor

Working with family can be complicated and few decisions are as fraught as choosing someone to replace you. Remember the purpose of a succession plan is to do what’s best for the future of the business, its customers, vendors and employees—not any particular family member.

Now is also the time to seek advice from a diverse group of non-family members. Start with your legal and accounting professionals for help with the basics. Job descriptions and skill assessments, for example, may narrow or broaden your list of potential successors. Board members, key customers and trusted vendor partners, whether or not they have specific personnel input, will be happy to know you are planning for succession.

Talk to prospective successors

Succession planning is not the time to make assumptions about what the next generation wants and is capable of. Including them in the process may reveal strengths and weaknesses crucial to your decision making.

According to Michael Klein , author of “ Trapped in the Family Business ,” this is the time for potential successors to ask themselves some honest questions. By reviewing their motivations, qualifications and the emotional weight of carrying on what the previous generation started, the children of business owners can assure themselves, and you, that the corner office is the right future for them.

Talk to non-family employees

You should keep key employees in the loop for several reasons: First, because they have a right to know a succession plan is in the works; and second, because of the valuable insights they may have about people and processes. Long-term employees may already be working alongside family members, giving them insight that you, as the boss, might not have. Asking their opinion is a sign of respect. Finally, your successor is going to need the acceptance and cooperation of non-family employees who may be the ones offering training. This crucial support is gained more easily if the non-family employee is part of the process.

If you’re concerned about losing rising stars, the truth is, it may happen. Those with ambitions to become CEO might look elsewhere when it becomes clear they are not in contention. The risk is necessary, however, and not everyone wants to be the boss. According to the Conway Center for Family Business , working for a family-owned business can have its perks. From the way they measure success (not just profits and growth), to the strategies they embrace (putting employees first, being socially responsible), family businesses can be a great place to work.

Making a plan is the first—and most difficult—step

Announcing your successor, getting them the education and training they’ll need and having an annual review of progress all remain on your to-do list.

Remember, succession planning is a good problem—a best-case scenario. It means your business has a future—one so bright it’s going to outlive your desire, or ability, to run it. You’ve always had a plan for the worst case. You should have one for the best case, too.

CO— aims to bring you inspiration from leading respected experts. However, before making any business decision, you should consult a professional who can advise you based on your individual situation.

Follow us on Instagram for more expert tips & business owners stories.

CO—is committed to helping you start, run and grow your small business. Learn more about the benefits of small business membership in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, here .

Subscribe to our newsletter, Midnight Oil

Expert business advice, news, and trends, delivered weekly

By signing up you agree to the CO— Privacy Policy. You can opt out anytime.

For more business strategies

How startups contribute to innovation in emerging industries, how entrepreneurs can find a business mentor, 5 business metrics you should analyze every year.

By continuing on our website, you agree to our use of cookies for statistical and personalisation purposes. Know More

Welcome to CO—

Designed for business owners, CO— is a site that connects like minds and delivers actionable insights for next-level growth.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce 1615 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20062

Social links

Looking for local chamber, stay in touch.

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

Managing a Family Business for Success and Succession

Exploring the dynamics and decisions of running a family business in Kenya.

May 18, 2021

Meet Naomi Kipkorir and Annette Kimitei, the mother-daughter team leading Senaca East Africa, and Peter Francis, lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and hear about finding success and navigating succession in a family-run business.

Family dynamics can be challenging, not to mention emotional. But when you add in a business, things can get even more complicated, especially when the entire family is involved. That’s the story behind Senaca EA, a private security company headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya. Founded by Kipkorir’s husband, an ex-policeman, the business started in 2002 as a side hustle and now it’s a full-time, all-in-the-family-of-five affair.

After a failed merger with a European company, the family literally came together to pull their company back from the brink. Thinking about family succession came next. And as Kimitei learned, “Succession is not one event, it’s a process.” Formalizing corporate governance is key to that process, which for Senaca begins with introducing advisory board members who have skill sets the business is missing, and eventually independent directors.

Francis fully supports that plan. And he knows from experience: his family-run business has been going for six generations. Francis uses that firsthand knowledge to teach a class called “The Yin and Yang of Family Business Transition” at Stanford. Because issues that arise in a family business can often turn emotional, Francis advises seeking outside expertise and relying on education, transparency, and communication to handle tough issues.

“If you’re having a conversation about the business at home you might say, ‘You know what, we’re home, we should be wearing our family hat, not our business hat.’ And then communication … I don’t mean just communicating, but also learning how to communicate. That is a muscle that we can strengthen in the family.”

Listen to Kipkorir and Kimitei’s family story and Francis’ business insights to help think about your own company’s succession and governance plans.

Suggested Resources

Grit & Growth is a podcast produced by Stanford Seed , an institute at Stanford Graduate School of Business which partners with entrepreneurs in emerging markets to build thriving enterprises that transform lives.

Hear these entrepreneurs’ stories of trial and triumph, and gain insights and guidance from Stanford University faculty and global business experts on how to transform today’s challenges into tomorrow’s opportunities.

Full Transcript

Naomi Kipkorir: We are not just a family business that is by blood. Even the way we relate with our customers, the way we relate with our suppliers, the way we relate with each other, we came to realize that it was a strength and not a weakness.

Darius Teter: Naomi Kipkorir is the proud CEO of a family business, and she’s been on quite a journey with her company.

Naomi Kipkorir: I used to tell them, “Whatever brought us here won’t take us where we are going. So you have to accept change.” And they are telling me, “Now it’s not change, it’s even transformation.”

Darius Teter: For family businesses, planning for leadership change presents many challenges. But could the act of family succession itself give your business the tools to re-imagine