Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

English EFL

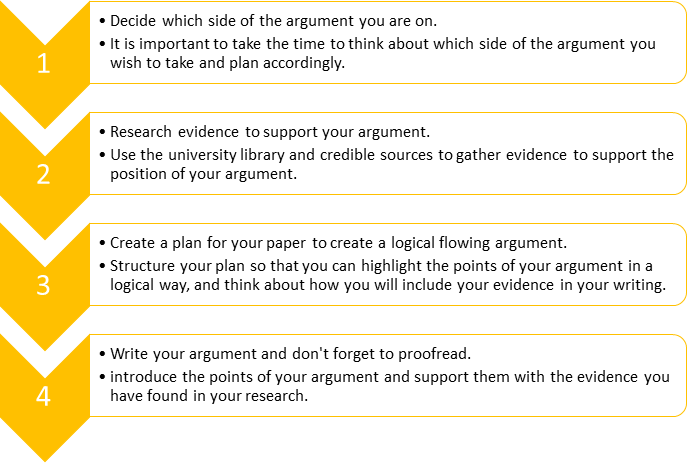

4 key points for effective assignment writing.

Methodology

By Christina Desouza

Writing an effective assignment is more of an art than a science. It demands critical thinking, thorough research, organized planning, and polished execution. As a professional academic writer with over four years of experience, I've honed these skills and discovered proven strategies for creating standout assignments.

In this article, I will delve into the four key steps of assignment writing, offering detailed advice and actionable tips to help students master this craft.

1. Start With Research

In-depth research is the cornerstone of any high-quality assignment. It allows you to gain a profound understanding of your topic and equip yourself with relevant data, compelling arguments, and unique insights.

Here's how to do it right:

● Diversify Your Sources

Don't limit yourself to the first page of Google results. Make use of academic databases like JSTOR , Google Scholar , PubMed , or your school's online library. These resources house a plethora of scholarly articles, research papers, and academic books that can provide you with valuable information.

● Verify Information

Remember, not all information is created equal. Cross-check facts and data from multiple reliable sources to ensure accuracy. Look for consensus among experts on contentious issues.

● Stay Organized

Keep track of your resources as you go. Tools like Zotero or Mendeley can help you organize your references and generate citations in various formats. This will save you from scrambling to find sources when you're wrapping up your assignment.

1. Prepare Assignment Structure

Creating a well-planned structure for your assignment is akin to drawing a roadmap. It helps you stay on track and ensures that your ideas flow logically. Here's what to consider:

● Develop an Outline

The basic structure of an assignment includes an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction should present the topic and establish the purpose of your assignment. The body should delve into the topic in detail, backed by your research. The conclusion should summarize your findings or arguments without introducing new ideas.

● Use Subheadings

Subheadings make your assignment easier to read and follow. They allow you to break down complex ideas into manageable sections. As a rule of thumb, each paragraph should cover one idea or argument.

● Allocate Word Count

Assignments often come with word limits. Allocate word count for each section of your assignment based on its importance to avoid overwriting or underwriting any part.

1. Start Assignment Writing

Writing your assignment is where your research and planning come to fruition. You now have a robust foundation to build upon, and it's time to craft a compelling narrative.

Here's how to accomplish this:

● Write a Gripping Introduction

Your introduction is the gateway to your assignment. Make it captivating. Start with a hook—a surprising fact, an interesting quote, or a thought-provoking question—to grab your readers' attention. Provide an overview of what your assignment is about and the purpose it serves. A well-crafted introduction sets the tone for the rest of the assignment and motivates your readers to delve deeper into your work.

● Develop a Comprehensive Body

The body of your assignment is where you delve into the details. Develop your arguments, present your data, and discuss your findings. Use clear and concise language. Avoid jargon unless necessary. Each paragraph should cover one idea or argument to maintain readability.

● Craft a Convincing Conclusion

Your conclusion is your final chance to leave an impression on your reader. Summarize your key findings or arguments without introducing new ideas. Reinforce the purpose of your assignment and provide a clear answer to the question or problem you addressed in the introduction. A strong conclusion leaves your readers with a sense of closure and a full understanding of your topic.

● Write Clearly

Use straightforward sentences and avoid jargon. Your goal is to communicate, not to confuse. Tools like Hemingway Editor can help ensure your writing is clear and concise.

● Use Paraphrasingtool.ai

Paraphrasingtool.ai is an AI-powered tool that can enhance your assignment writing. It reformulates your sentences while preserving their meaning. It not only helps you avoid plagiarism but also enhances the readability of your work.

● Cite Your Sources

Citations are a critical part of assignment writing. They acknowledge the work of others you've built upon and demonstrate the depth of your research. Always include in-text citations and a bibliography at the end. This not only maintains academic integrity but also gives your readers resources to delve deeper into the topic if they wish.

1. Review and Proofread The Assignment

Reviewing and proofreading are the final but critical steps in assignment writing. They ensure your assignment is free from errors and that your ideas are coherently presented. Here's how to do it effectively:

● Take a Break

After you finish writing, take a break before you start proofreading. Fresh eyes are more likely to spot mistakes and inconsistencies.

● Read Aloud

Reading your work aloud can help you identify awkward phrasing, run-on sentences, and typos. You're more likely to catch errors when you hear them, as it requires a different type of processing than reading silently.

● Use Proofreading Tools

Digital tools like Grammarly can be your second pair of eyes, helping you spot grammatical errors, typos, and even issues with sentence structure. However, don't rely solely on these tools—make sure to manually review your work as well.

Effective assignment writing is a skill that takes practice to master. It requires meticulous research, organized planning, clear writing, and careful proofreading. The steps and tips outlined in this article are by no means exhaustive, but they provide a solid framework to start from.

Remember, there is always room for improvement. Don't be disheartened by initial challenges. Each assignment is an opportunity to learn, grow, and sharpen your writing skills. So, be persistent, stay curious, and keep refining your craft. With time and practice, you will find yourself writing assignments that are not just excellent, but truly outstanding.

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

How to Write an Effective Assignment

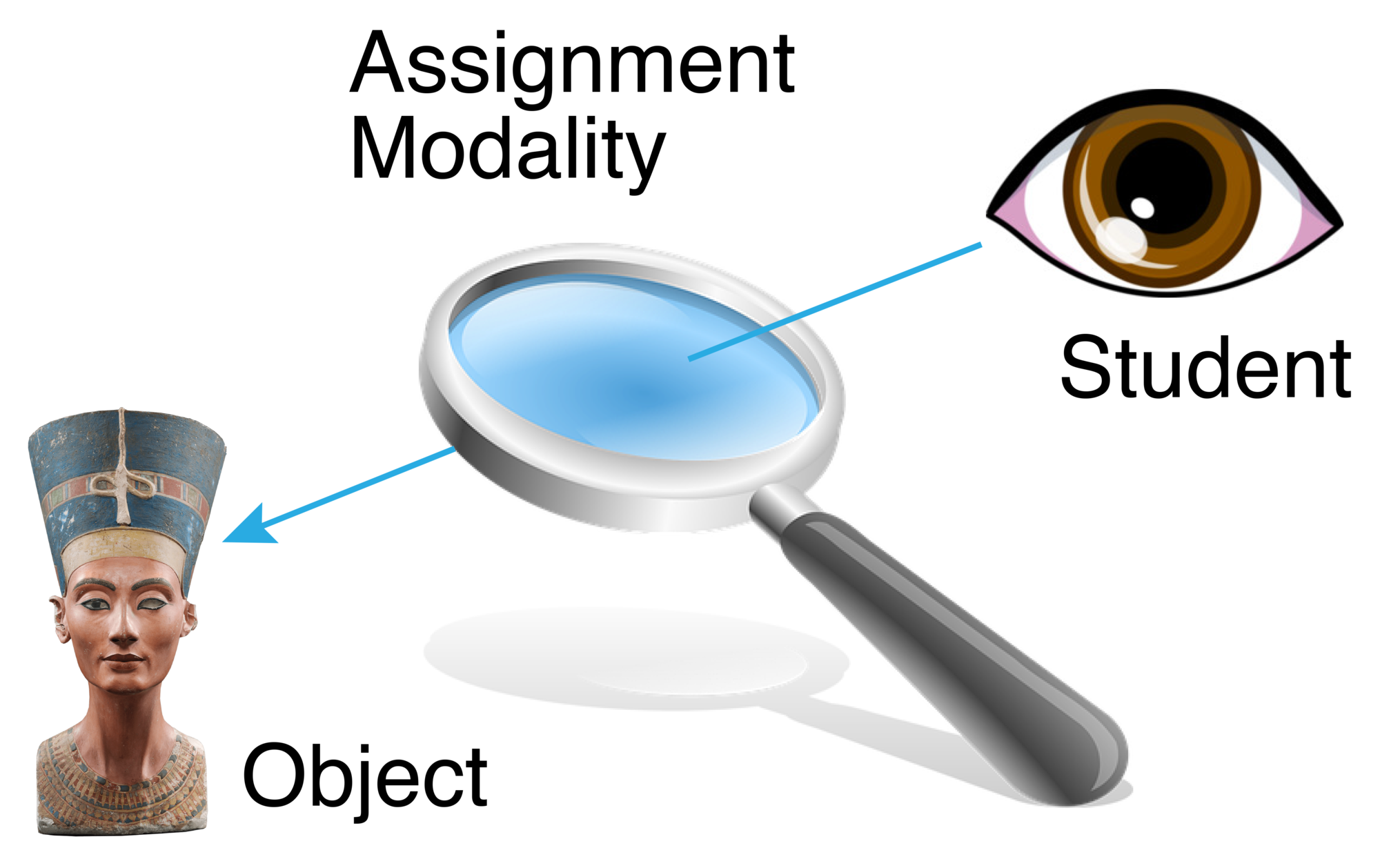

At their base, all assignment prompts function a bit like a magnifying glass—they allow a student to isolate, focus on, inspect, and interact with some portion of your course material through a fixed lens of your choosing.

The Key Components of an Effective Assignment Prompt

All assignments, from ungraded formative response papers all the way up to a capstone assignment, should include the following components to ensure that students and teachers understand not only the learning objective of the assignment, but also the discrete steps which they will need to follow in order to complete it successfully:

- Preamble. This situates the assignment within the context of the course, reminding students of what they have been working on in anticipation of the assignment and how that work has prepared them to succeed at it.

- Justification and Purpose. This explains why the particular type or genre of assignment you’ve chosen (e.g., lab report, policy memo, problem set, or personal reflection) is the best way for you and your students to measure how well they’ve met the learning objectives associated with this segment of the course.

- Mission. This explains the assignment in broad brush strokes, giving students a general sense of the project you are setting before them. It often gives students guidance on the evidence or data they should be working with, as well as helping them imagine the audience their work should be aimed at.

- Tasks. This outlines what students are supposed to do at a more granular level: for example, how to start, where to look, how to ask for help, etc. If written well, this part of the assignment prompt ought to function as a kind of "process" rubric for students, helping them to decide for themselves whether they are completing the assignment successfully.

- Submission format. This tells students, in appropriate detail, which stylistic conventions they should observe and how to submit their work. For example, should the assignment be a five-page paper written in APA format and saved as a .docx file? Should it be uploaded to the course website? Is it due by Tuesday at 5:00pm?

For illustrations of these five components in action, visit our gallery of annotated assignment prompts .

For advice about creative assignments (e.g. podcasts, film projects, visual and performing art projects, etc.), visit our Guidance on Non-Traditional Forms of Assessment .

For specific advice on different genres of assignment, click below:

Response Papers

Problem sets, source analyses, final exams, concept maps, research papers, oral presentations, poster presentations.

- Learner-Centered Design

- Putting Evidence at the Center

- What Should Students Learn?

- Start with the Capstone

- Gallery of Annotated Assignment Prompts

- Scaffolding: Using Frequency and Sequencing Intentionally

- Curating Content: The Virtue of Modules

- Syllabus Design

- Catalogue Materials

- Making a Course Presentation Video

- Teaching Teams

- In the Classroom

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

NCI LIBRARY

Academic writing skills guide: structuring your assignment.

- Key Features of Academic Writing

- The Writing Process

- Understanding Assignments

- Brainstorming Techniques

- Planning Your Assignments

- Thesis Statements

- Writing Drafts

- Structuring Your Assignment

- How to Deal With Writer's Block

- Using Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Introductions

- Revising & Editing

- Proofreading

- Grammar & Punctuation

- Reporting Verbs

- Signposting, Transitions & Linking Words/Phrases

- Using Lecturers' Feedback

Keep referring back to the question and assignment brief and make sure that your structure matches what you have been asked to do and check to see if you have appropriate and sufficient evidence to support all of your points. Plans can be structured/restructured at any time during the writing process.

Once you have decided on your key point(s), draw a line through any points that no longer seem to fit. This will mean you are eliminating some ideas and potentially letting go of one or two points that you wanted to make. However, this process is all about improving the relevance and coherence of your writing. Writing involves making choices, including the tough choice to sideline ideas that, however promising, do not fit into your main discussion.

Eventually, you will have a structure that is detailed enough for you to start writing. You will know which ideas go into each section and, ideally, each paragraph and in what order. You will also know which evidence for those ideas from your notes you will be using for each section and paragraph.

Once you have a map/framework of the proposed structure, this forms the skeleton of your assignment and if you have invested enough time and effort into researching and brainstorming your ideas beforehand, it should make it easier to flesh it out. Ultimately, you are aiming for a final draft where you can sum up each paragraph in a couple of words as each paragraph focuses on one main point or idea.

Communications from the Library: Please note all communications from the library, concerning renewal of books, overdue books and reservations will be sent to your NCI student email account.

- << Previous: Writing Drafts

- Next: How to Deal With Writer's Block >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 1:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ncirl.ie/academic_writing_skills

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

- Teesside University Student & Library Services

- Learning Hub Group

Structuring your assignment

Getting started with academic writing: the time model, information and videos on being targeted, being in-depth and bringing it all together, further reading, using material on this page.

Evidence-based

- Bringing it all together

- Finally ...

- Writing an assignment takes time, more time than you may expect. Just because you find yourself spending many weeks on an assignment doesn’t mean that you’re approaching it in the wrong way.

- It also takes time to develop the skills to write well, so don’t be discouraged if your early marks aren’t what you’d hoped for. Use the feedback from your previous assignments to improve.

- Different types of assignments require different styles, so be prepared for the need to continue to develop your skills.

We’ve broken down TIME into 4 key elements of academic writing: Targeted, In-depth, Measured and Evidence-based.

- What is an academic piece of work

Your assignment needs to be targeted . It should:

- Be focused on the questions and criteria

- Make a decision

- Follow an argument

- How to be targeted

- Academic keywords or clue words

Your assignment needs to be in-depth . You should consider your questions and criteria thoroughly, thinking about all possible aspects, and including the argument both for and against different viewpoints.

You should:

- Identify topic areas

- Plan your assignment

- Think about your introduction and conclusion

- How to be in-depth

- How to read quickly

An academic writing style is measured. By this, we mean that it’s:

- Emotionally neutral

- Formal – written in the third person and in full sentences

- How to be measured

Your assignment needs to be evidence-based . You should:

- Reference all the ideas in your work

- Paraphrase your evidence

- Apply critical thinking to your evidence

- How to be evidence-based

- How to paraphrase

Once you’ve found all your evidence, and have decided what to say in each section, you need to write it up as paragraphs. Each paragraph should be on a single topic, making a single point. A paragraph is usually around a third of a page.

We find Godwin’s (2014) WEED model very helpful for constructing paragraphs.

W is for What

You should begin your paragraph with the topic or point that you’re making, so that it’s clear to your lecturer. Everything in the paragraph should fit in with this opening sentence.

E is for Evidence

The middle of your paragraph should be full of evidence – this is where all your references should be incorporated. Make sure that your evidence fits in with your topic.

E is for Examples

Sometimes it’s useful to expand on your evidence. If you’re talking about a case study, the example might be how your point relates to the particular scenario being discussed.

D is for Do

You should conclude your paragraph with the implications of your discussion. This gives you the opportunity to add your commentary, which is very important in assignments which require you to use critical analysis.

So, in effect, each paragraph is like a mini-essay, with an introduction, main body and conclusion.

Allow yourself some TIME to proofread your assignment. You’ll probably want to proofread it several times.

You should read it through at least once for sense and structure, to see if your paragraphs flow. Check that your introduction matches the content of your assignment. You’ll also want to make sure that you’ve been concise in your writing style.

You’ll then need to read it again to check for grammatical errors, typos and that your references are correct.

It’s best if you can create some distance from your assignment by coming back to it after a few days. It’s also often easier to pick out mistakes if you read your work aloud.

- How to proofread

- Identifying what the assessment criteria is asking you to do (being targeted/generating ideas)

- Planning your argument (b eing in-depth/organising ideas)

- Structuring paragraphs, conclusions and introductions (b ringing it all together)

The resources below are available in different formats to suit your learning style, including: a full visual and printable guide; bite-size printable guides ; bite-size videos; and infographics.

Full guide:

Content includes: using the assessment criteria; planning your argument and structuring paragraphs, introductions and conclusions.

Bite-size videos ( Link to example WEED paragraph used in the videos):

Bite-size guide (visual and printable):.

Tips on how to: generate ideas; organise ideas; and structure paragraphs, introductions and conclusions.

- Structuring your assignment PDF

- Structuring your assignment PPT

- Structuring your assignment workshop: exercise text (PDF)

- Structuring your assignment workshop: exercise text (Word)

- Structuring your assignment: planning templates (PDF)

- Structuring your assignment workshop: planning templates (Word)

Online reading list of additional resources and further reading

If you thought this information was useful you may want to look at some of the other Learning Hub guides aimed at helping students with their assessments:

If you have any comments about this skills guide, we would love to know them.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License .

- Last Updated: Feb 7, 2024 2:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/structure

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Assignments

Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine

Introduction

Assignments are a common method of assessment at university and require careful planning and good quality research. Developing critical thinking and writing skills are also necessary to demonstrate your ability to understand and apply information about your topic. It is not uncommon to be unsure about the processes of writing assignments at university.

- You may be returning to study after a break

- You may have come from an exam based assessment system and never written an assignment before

- Maybe you have written assignments but would like to improve your processes and strategies

This chapter has a collection of resources that will provide you with the skills and strategies to understand assignment requirements and effectively plan, research, write and edit your assignments. It begins with an explanation of how to analyse an assignment task and start putting your ideas together. It continues by breaking down the components of academic writing and exploring the elements you will need to master in your written assignments. This is followed by a discussion of paraphrasing and synthesis, and how you can use these strategies to create a strong, written argument. The chapter concludes with useful checklists for editing and proofreading to help you get the best possible mark for your work.

Task Analysis and Deconstructing an Assignment

It is important that before you begin researching and writing your assignments you spend sufficient time understanding all the requirements. This will help make your research process more efficient and effective. Check your subject information such as task sheets, criteria sheets and any additional information that may be in your subject portal online. Seek clarification from your lecturer or tutor if you are still unsure about how to begin your assignments.

The task sheet typically provides key information about an assessment including the assignment question. It can be helpful to scan this document for topic, task and limiting words to ensure that you fully understand the concepts you are required to research, how to approach the assignment, and the scope of the task you have been set. These words can typically be found in your assignment question and are outlined in more detail in the two tables below (see Table 19.1 and Table 19.2 ).

Table 19.1 Parts of an Assignment Question

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the task word requires you to address.

Table 19.2 Task words

The criteria sheet , also known as the marking sheet or rubric, is another important document to look at before you begin your assignment. The criteria sheet outlines how your assignment will be marked and should be used as a checklist to make sure you have included all the information required.

The task or criteria sheet will also include the:

- Word limit (or word count)

- Referencing style and research expectations

- Formatting requirements

Task analysis and criteria sheets are also discussed in the chapter Managing Assessments for a more detailed discussion on task analysis, criteria sheets, and marking rubrics.

Preparing your ideas

Brainstorm or concept map: List possible ideas to address each part of the assignment task based on what you already know about the topic from lectures and weekly readings.

Finding appropriate information: Learn how to find scholarly information for your assignments which is

See the chapter Working With Information for a more detailed explanation .

What is academic writing?

Academic writing tone and style.

Many of the assessment pieces you prepare will require an academic writing style. This is sometimes called ‘academic tone’ or ‘academic voice’. This section will help you to identify what is required when you are writing academically (see Table 19.3 ). The best way to understand what academic writing looks like, is to read broadly in your discipline area. Look at how your course readings, or scholarly sources, are written. This will help you identify the language of your discipline field, as well as how other writers structure their work.

Table 19.3 Comparison of academic and non-academic writing

Thesis statements.

Essays are a common form of assessment that you will likely encounter during your university studies. You should apply an academic tone and style when writing an essay, just as you would in in your other assessment pieces. One of the most important steps in writing an essay is constructing your thesis statement. A thesis statement tells the reader the purpose, argument or direction you will take to answer your assignment question. A thesis statement may not be relevant for some questions, if you are unsure check with your lecturer. The thesis statement:

- Directly relates to the task . Your thesis statement may even contain some of the key words or synonyms from the task description.

- Does more than restate the question.

- Is specific and uses precise language.

- Let’s your reader know your position or the main argument that you will support with evidence throughout your assignment.

- The subject is the key content area you will be covering.

- The contention is the position you are taking in relation to the chosen content.

Your thesis statement helps you to structure your essay. It plays a part in each key section: introduction, body and conclusion.

Planning your assignment structure

When planning and drafting assignments, it is important to consider the structure of your writing. Academic writing should have clear and logical structure and incorporate academic research to support your ideas. It can be hard to get started and at first you may feel nervous about the size of the task, this is normal. If you break your assignment into smaller pieces, it will seem more manageable as you can approach the task in sections. Refer to your brainstorm or plan. These ideas should guide your research and will also inform what you write in your draft. It is sometimes easier to draft your assignment using the 2-3-1 approach, that is, write the body paragraphs first followed by the conclusion and finally the introduction.

Writing introductions and conclusions

Clear and purposeful introductions and conclusions in assignments are fundamental to effective academic writing. Your introduction should tell the reader what is going to be covered and how you intend to approach this. Your conclusion should summarise your argument or discussion and signal to the reader that you have come to a conclusion with a final statement. These tips below are based on the requirements usually needed for an essay assignment, however, they can be applied to other assignment types.

Writing introductions

Most writing at university will require a strong and logically structured introduction. An effective introduction should provide some background or context for your assignment, clearly state your thesis and include the key points you will cover in the body of the essay in order to prove your thesis.

Usually, your introduction is approximately 10% of your total assignment word count. It is much easier to write your introduction once you have drafted your body paragraphs and conclusion, as you know what your assignment is going to be about. An effective introduction needs to inform your reader by establishing what the paper is about and provide four basic things:

- A brief background or overview of your assignment topic

- A thesis statement (see section above)

- An outline of your essay structure

- An indication of any parameters or scope that will/ will not be covered, e.g. From an Australian perspective.

The below example demonstrates the four different elements of an introductory paragraph.

1) Information technology is having significant effects on the communication of individuals and organisations in different professions. 2) This essay will discuss the impact of information technology on the communication of health professionals. 3) First, the provision of information technology for the educational needs of nurses will be discussed. 4) This will be followed by an explanation of the significant effects that information technology can have on the role of general practitioner in the area of public health. 5) Considerations will then be made regarding the lack of knowledge about the potential of computers among hospital administrators and nursing executives. 6) The final section will explore how information technology assists health professionals in the delivery of services in rural areas . 7) It will be argued that information technology has significant potential to improve health care and medical education, but health professionals are reluctant to use it.

1 Brief background/ overview | 2 Indicates the scope of what will be covered | 3-6 Outline of the main ideas (structure) | 7 The thesis statement

Note : The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing conclusions

You should aim to end your assignments with a strong conclusion. Your conclusion should restate your thesis and summarise the key points you have used to prove this thesis. Finish with a key point as a final impactful statement. Similar to your introduction, your conclusion should be approximately 10% of the total assignment word length. If your assessment task asks you to make recommendations, you may need to allocate more words to the conclusion or add a separate recommendations section before the conclusion. Use the checklist below to check your conclusion is doing the right job.

Conclusion checklist

- Have you referred to the assignment question and restated your argument (or thesis statement), as outlined in the introduction?

- Have you pulled together all the threads of your essay into a logical ending and given it a sense of unity?

- Have you presented implications or recommendations in your conclusion? (if required by your task).

- Have you added to the overall quality and impact of your essay? This is your final statement about this topic; thus, a key take-away point can make a great impact on the reader.

- Remember, do not add any new material or direct quotes in your conclusion.

This below example demonstrates the different elements of a concluding paragraph.

1) It is evident, therefore, that not only do employees need to be trained for working in the Australian multicultural workplace, but managers also need to be trained. 2) Managers must ensure that effective in-house training programs are provided for migrant workers, so that they become more familiar with the English language, Australian communication norms and the Australian work culture. 3) In addition, Australian native English speakers need to be made aware of the differing cultural values of their workmates; particularly the different forms of non-verbal communication used by other cultures. 4) Furthermore, all employees must be provided with clear and detailed guidelines about company expectations. 5) Above all, in order to minimise communication problems and to maintain an atmosphere of tolerance, understanding and cooperation in the multicultural workplace, managers need to have an effective knowledge about their employees. This will help employers understand how their employee’s social conditioning affects their beliefs about work. It will develop their communication skills to develop confidence and self-esteem among diverse work groups. 6) The culturally diverse Australian workplace may never be completely free of communication problems, however, further studies to identify potential problems and solutions, as well as better training in cross cultural communication for managers and employees, should result in a much more understanding and cooperative environment.

1 Reference to thesis statement – In this essay the writer has taken the position that training is required for both employees and employers . | 2-5 Structure overview – Here the writer pulls together the main ideas in the essay. | 6 Final summary statement that is based on the evidence.

Note: The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing paragraphs

Paragraph writing is a key skill that enables you to incorporate your academic research into your written work. Each paragraph should have its own clearly identified topic sentence or main idea which relates to the argument or point (thesis) you are developing. This idea should then be explained by additional sentences which you have paraphrased from good quality sources and referenced according to the recommended guidelines of your subject (see the chapter Working with Information ). Paragraphs are characterised by increasing specificity; that is, they move from the general to the specific, increasingly refining the reader’s understanding. A common structure for paragraphs in academic writing is as follows.

Topic Sentence

This is the main idea of the paragraph and should relate to the overall issue or purpose of your assignment is addressing. Often it will be expressed as an assertion or claim which supports the overall argument or purpose of your writing.

Explanation/ Elaboration

The main idea must have its meaning explained and elaborated upon. Think critically, do not just describe the idea.

These explanations must include evidence to support your main idea. This information should be paraphrased and referenced according to the appropriate referencing style of your course.

Concluding sentence (critical thinking)

This should explain why the topic of the paragraph is relevant to the assignment question and link to the following paragraph.

Use the checklist below to check your paragraphs are clear and well formed.

Paragraph checklist

- Does your paragraph have a clear main idea?

- Is everything in the paragraph related to this main idea?

- Is the main idea adequately developed and explained?

- Do your sentences run together smoothly?

- Have you included evidence to support your ideas?

- Have you concluded the paragraph by connecting it to your overall topic?

Writing sentences

Make sure all the sentences in your paragraphs make sense. Each sentence must contain a verb to be a complete sentence. Avoid sentence fragments . These are incomplete sentences or ideas that are unfinished and create confusion for your reader. Avoid also run on sentences . This happens when you join two ideas or clauses without using the appropriate punctuation. This also confuses your meaning (See the chapter English Language Foundations for examples and further explanation).

Use transitions (linking words and phrases) to connect your ideas between paragraphs and make your writing flow. The order that you structure the ideas in your assignment should reflect the structure you have outlined in your introduction. Refer to transition words table in the chapter English Language Foundations.

Paraphrasing and Synthesising

Paraphrasing and synthesising are powerful tools that you can use to support the main idea of a paragraph. It is likely that you will regularly use these skills at university to incorporate evidence into explanatory sentences and strengthen your essay. It is important to paraphrase and synthesise because:

- Paraphrasing is regarded more highly at university than direct quoting.

- Paraphrasing can also help you better understand the material.

- Paraphrasing and synthesising demonstrate you have understood what you have read through your ability to summarise and combine arguments from the literature using your own words.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is changing the writing of another author into your words while retaining the original meaning. You must acknowledge the original author as the source of the information in your citation. Follow the steps in this table to help you build your skills in paraphrasing (see Table 19.4 ).

Table 19.4 Paraphrasing techniques

Example of paraphrasing.

Please note that these examples and in text citations are for instructional purposes only.

Original text

Health care professionals assist people often when they are at their most vulnerable . To provide the best care and understand their needs, workers must demonstrate good communication skills . They must develop patient trust and provide empathy to effectively work with patients who are experiencing a variety of situations including those who may be suffering from trauma or violence, physical or mental illness or substance abuse (French & Saunders, 2018).

Poor quality paraphrase example

This is a poor example of paraphrasing. Some synonyms have been used and the order of a few words changed within the sentences however the colours of the sentences indicate that the paragraph follows the same structure as the original text.

Health care sector workers are often responsible for vulnerable patients. To understand patients and deliver good service , they need to be excellent communicators . They must establish patient rapport and show empathy if they are to successfully care for patients from a variety of backgrounds and with different medical, psychological and social needs (French & Saunders, 2018).

A good quality paraphrase example

This example demonstrates a better quality paraphrase. The author has demonstrated more understanding of the overall concept in the text by using the keywords as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up to see how much the structure has changed from the original text.

Empathetic communication is a vital skill for health care workers. Professionals in these fields are often responsible for patients with complex medical, psychological and social needs. Empathetic communication assists in building rapport and gaining the necessary trust to assist these vulnerable patients by providing appropriate supportive care (French & Saunders, 2018).

The good quality paraphrase example demonstrates understanding of the overall concept in the text by using key words as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up, which indicates how much the structure has changed from the original text.

What is synthesising?

Synthesising means to bring together more than one source of information to strengthen your argument. Once you have learnt how to paraphrase the ideas of one source at a time, you can consider adding additional sources to support your argument. Synthesis demonstrates your understanding and ability to show connections between multiple pieces of evidence to support your ideas and is a more advanced academic thinking and writing skill.

Follow the steps in this table to improve your synthesis techniques (see Table 19.5 ).

Table 19.5 Synthesising techniques

Example of synthesis

There is a relationship between academic procrastination and mental health outcomes. Procrastination has been found to have a negative effect on students’ well-being (Balkis, & Duru, 2016). Yerdelen, McCaffrey, and Klassens’ (2016) research results suggested that there was a positive association between procrastination and anxiety. This was corroborated by Custer’s (2018) findings which indicated that students with higher levels of procrastination also reported greater levels of the anxiety. Therefore, it could be argued that procrastination is an ineffective learning strategy that leads to increased levels of distress.

Topic sentence | Statements using paraphrased evidence | Critical thinking (student voice) | Concluding statement – linking to topic sentence

This example demonstrates a simple synthesis. The author has developed a paragraph with one central theme and included explanatory sentences complete with in-text citations from multiple sources. Note how the blocks of colour have been used to illustrate the paragraph structure and synthesis (i.e., statements using paraphrased evidence from several sources). A more complex synthesis may include more than one citation per sentence.

Creating an argument

What does this mean.

Throughout your university studies, you may be asked to ‘argue’ a particular point or position in your writing. You may already be familiar with the idea of an argument, which in general terms means to have a disagreement with someone. Similarly, in academic writing, if you are asked to create an argument, this means you are asked to have a position on a particular topic, and then justify your position using evidence.

What skills do you need to create an argument?

In order to create a good and effective argument, you need to be able to:

- Read critically to find evidence

- Plan your argument

- Think and write critically throughout your paper to enhance your argument

For tips on how to read and write critically, refer to the chapter Thinking for more information. A formula for developing a strong argument is presented below.

A formula for a good argument

What does an argument look like?

As can be seen from the figure above, including evidence is a key element of a good argument. While this may seem like a straightforward task, it can be difficult to think of wording to express your argument. The table below provides examples of how you can illustrate your argument in academic writing (see Table 19.6 ).

Table 19.6 Argument

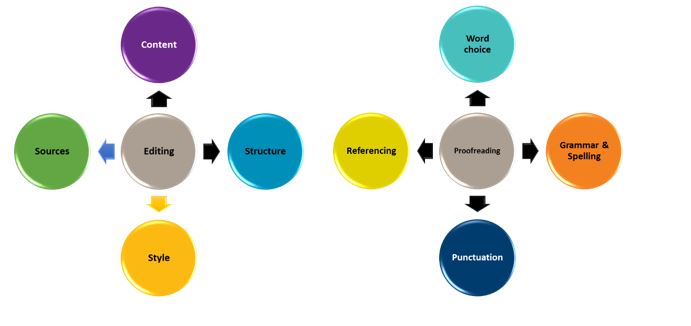

Editing and proofreading (reviewing).

Once you have finished writing your first draft it is recommended that you spend time revising your work. Proofreading and editing are two different stages of the revision process.

- Editing considers the overall focus or bigger picture of the assignment

- Proofreading considers the finer details

As can be seen in the figure above there are four main areas that you should review during the editing phase of the revision process. The main things to consider when editing include content, structure, style, and sources. It is important to check that all the content relates to the assignment task, the structure is appropriate for the purposes of the assignment, the writing is academic in style, and that sources have been adequately acknowledged. Use the checklist below when editing your work.

Editing checklist

- Have I answered the question accurately?

- Do I have enough credible, scholarly supporting evidence?

- Is my writing tone objective and formal enough or have I used emotive and informal language?

- Have I written in the third person not the first person?

- Do I have appropriate in-text citations for all my information?

- Have I included the full details for all my in-text citations in my reference list?

There are also several key things to look out for during the proofreading phase of the revision process. In this stage it is important to check your work for word choice, grammar and spelling, punctuation and referencing errors. It can be easy to mis-type words like ‘from’ and ‘form’ or mix up words like ‘trail’ and ‘trial’ when writing about research, apply American rather than Australian spelling, include unnecessary commas or incorrectly format your references list. The checklist below is a useful guide that you can use when proofreading your work.

Proofreading checklist

- Is my spelling and grammar accurate?

- Are they complete?

- Do they all make sense?

- Do they only contain only one idea?

- Do the different elements (subject, verb, nouns, pronouns) within my sentences agree?

- Are my sentences too long and complicated?

- Do they contain only one idea per sentence?

- Is my writing concise? Take out words that do not add meaning to your sentences.

- Have I used appropriate discipline specific language but avoided words I don’t know or understand that could possibly be out of context?

- Have I avoided discriminatory language and colloquial expressions (slang)?

- Is my referencing formatted correctly according to my assignment guidelines? (for more information on referencing refer to the Managing Assessment feedback section).

This chapter has examined the experience of writing assignments. It began by focusing on how to read and break down an assignment question, then highlighted the key components of essays. Next, it examined some techniques for paraphrasing and summarising, and how to build an argument. It concluded with a discussion on planning and structuring your assignment and giving it that essential polish with editing and proof-reading. Combining these skills and practising them, can greatly improve your success with this very common form of assessment.

- Academic writing requires clear and logical structure, critical thinking and the use of credible scholarly sources.

- A thesis statement is important as it tells the reader the position or argument you have adopted in your assignment. Not all assignments will require a thesis statement.

- Spending time analysing your task and planning your structure before you start to write your assignment is time well spent.

- Information you use in your assignment should come from credible scholarly sources such as textbooks and peer reviewed journals. This information needs to be paraphrased and referenced appropriately.

- Paraphrasing means putting something into your own words and synthesising means to bring together several ideas from sources.

- Creating an argument is a four step process and can be applied to all types of academic writing.

- Editing and proofreading are two separate processes.

Academic Skills Centre. (2013). Writing an introduction and conclusion . University of Canberra, accessed 13 August, 2013, http://www.canberra.edu.au/studyskills/writing/conclusions

Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2016). Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: underregulation or misregulation form. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31 (3), 439-459.

Custer, N. (2018). Test anxiety and academic procrastination among prelicensure nursing students. Nursing education perspectives, 39 (3), 162-163.

Yerdelen, S., McCaffrey, A., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Longitudinal examination of procrastination and anxiety, and their relation to self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: Latent growth curve modeling. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16 (1).

Writing Assignments Copyright © 2021 by Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Steps for writing assignments

- Information and services

- Student support

- Study skills and learning advice

- Study skills and learning advice overview

- Assignment writing

Follow this step-by-step guide to assignment writing to help you to manage your time and produce a better assignment.

This is a general guide. It's primarily for research essays, but can be used for all assignments. The specific requirements for your course may be different. Make sure you read through any assignment requirements carefully and ask your lecturer or tutor if you're unsure how to meet them.

- Analysing the topic

- Researching and note-taking

- Planning your assignment

- Writing your assignment

- Editing your assignment

1. Analysing the topic

Before you start researching or writing, take some time to analyse the assignment topic to make sure you know what you need to do.

Understand what you need to do

Read through the topic a few times to make sure you understand it. Think about the:

- learning objectives listed in the course profile – understand what you should be able to do after completing the course and its assessment tasks

- criteria you'll be marked on – find out what you need to do to achieve the grade you want

- questions you need to answer – try to explain the topic in your own words.

Identify keywords

Identify keywords in the topic that will help guide your research, including any:

- task words – what you have to do (usually verbs)

- topic words – ideas, concepts or issues you need to discuss (often nouns)

- limiting words – restrict the focus of the topic (e.g. to a place, population or time period).

If you're writing your own topic, include task words, topic words and limiting words to help you to focus on exactly what you have to do.

Example keyword identification - text version

Topic: Evaluate the usefulness of a task analysis approach to assignment writing, especially with regard to the writing skill development of second language learners in the early stages of university study in the Australian university context. Task words: Evaluate Topic words: task analysis approach, assignment writing, writing skill development Limiting words : second language learners (population), early stages of university (time period), Australian university (place)

Brainstorm your ideas

Brainstorm information about the topic that you:

- already know

- will need to research to write the assignment.

When you brainstorm:

- use 'Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How?' questions to get you thinking

- write down all your ideas – don't censor yourself or worry about the order

- try making a concept map to capture your ideas – start with the topic in the centre and record your ideas branching out from it.

- Assignment types

- How to write a literature review

Learning Advisers

Our advisers can help undergraduate and postgraduate students in all programs clarify ideas from workshops, help you develop skills and give feedback on assignments.

How a Learning Adviser can help

Further support

Workshops Find a proofreader

A simple but effective guide to writing a perfect assignment

The idea of writing assignments can be daunting; feeling under pressure, and unsure of if you've prepared enough to tackle the question effectively. Remember it does not have to be like this; the most important thing is to start – and start early.

Starting your assignment in good time will allow you to keep looming deadline pressures down. This should help you to maintain a better headspace; which will increase your ability to focus.

Keep reading for our quick guide to writing assignments; perfect for all levels. We recommend you also read the more detailed ABE Assignment Guide document below and, of course, work closely with your ABE tutors.

1. Read the Question

This may seem like an obvious step, but it is one that is often overlooked. Many of us do not take the time to carefully read the assignment question, and instead, skim-read. This can be risky as although you may have identified some of the keywords you think are important, you need to fully understand what is being asked and what answer the examiner is looking for.

Read our guide to command words here:

It is easy to get carried away and delve into writing your assignment without really answering the question. A good way to avoid this is to take some time to consider the keywords within the question and what they are prompting you to do. Understanding directive words such as 'evaluate', 'discuss', and 'explain', are vital when writing an assignment, as they provide instruction on how you are supposed to answer the question. It is a good idea to highlight or underline these words within the question, to help you keep them in mind as you progress through your assignment.

Sometimes the question can be written in a manner that makes it appear more intimidating than it is. Once you have read (and re-read) the question, you may find that what is being asked is actually quite straightforward. You may also benefit from rewriting it in a way that you are able to process the instructions better .

2. Research & Planning

Carefully researching and planning your assignment will give you a structure to follow when it comes to writing it. Research and planning will allow you to be better prepared and could make the difference between a mediocre piece of work and an exceptional one.

This is your chance to consider any specifications for the assignment such as word count, the points you would like to include, and how it needs to be set out.

When planning the points for your assignment it is important to understand what you are working towards. You should refer to the learning outcomes and assessment criteria for the assignment to help you with this. You can find these on the assignment brief as well as within the syllabus, in your Study Guide or in the Qualification Specification document for your course.

As well as researching the topic, it is also a good idea to find good source materials to include in your assignments beforehand. It's a good idea to do wider reading from reputable sources to gain different perspectives to support your answer.

3. Structure

Before you start, it can help to create an assignment structure. This can be as detailed as you like but the basic structure should be your introduction, key arguments and points, and your planned conclusion.

Introduction

This refers to a short paragraph that explains what you are going to be discussing. It should outline your argument and reference the key issues within the question.

This is where you should focus on structuring your argument. You may need to compare or critically evaluate two or more different methods or theories to explain your choices or recommendations. Examiners are looking to see if you can analyse information and make decisions accordingly. You should make sure that your ideas and claims are supported with research when required.

- When you start to discuss a new idea, you should start another paragraph

- When using a lot of different sources for supporting evidence, it can be easy to forget to add them to your reference list. To avoid this, reference as you go along

The conclusion is your final chance to summarise what you have discussed. You should be careful not to introduce new points that you did not mention within your assignment. A good conclusion will leave a lasting impression on the examiner, so make it count.

- Recap the key points in your assignment, including supporting evidence if needed.

4. Drafting

Ask your teacher for feedback by submitting the first draft of your assignment a few weeks before the final hand-in date. This will help you improve your assignment before submitting your final version.

- Make sure it is your own work; although your teacher can give you some advice on how to improve your work, you must write the assignment yourself

5. Proofread

Editing and proofreading can help you to improve your assignment even after you’ve finished writing it. Before doing this, it is important to get some distance from your work. Taking a short break will help you to come back and check it over with fresh eyes.

When proofreading, as well as grammatical; and spelling errors; you should be checking that the structure of your assignment is clear and that you have properly addressed all of the question.

- It can often be difficult to see mistakes in your own work, if possible ask a friend or family member to proofread your assignment for you

- Refer back to the assignment objectives; have you answered the question?

- Make sure that your assignment reads well, and that you are within the word count

6. Plagiarism & Referencing

Not taking the time out to reference properly is the biggest way to lose marks on an assignment. When using books, cases and journals you must reference to show where you got your information from.

When writing ABE assignments, you should use Harvard Referencing to correctly cite information sources and include a bibliography at the end. Citations should be listed in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If there are multiple sources by the same author, then citations are listed in order by the date of publication. Also, read the ABE Assignment Guide for more helpful information about referencing.

Using your own words, and correctly citing information sources mentioned within your assignment will help you ensure you have not committed plagiarism .

- Use anti-plagiarism software such as Quetext to check your work before submission, to pick up any risk of plagiarism. Your examiner will also be checking for plagiarism when marking; remember it’s not worth the risk – your assignment could be rejected if you get caught.

Writing assignments is something most of us cannot avoid; following these steps should make the process a lot easier.

We wish you every success. Do share any top tips of your own.

Happy writing.

Blog categories

- All blogs (36)

- Professional development (9)

- Study tips (5)

- ABE blogs (9)

- ABE way (7)

- For schools (6)

Membership offer from The Institute of Leadership

Our parent company, The Institute of Leadership (IoL) is offering ABE graduates, from Level 5 upwards, the opportunity to become an Institute Member at a price exclusively for ABE qualification holders. Read more .

How to Write a Perfect Assignment: Step-By-Step Guide

Table of contents

- 1 How to Structure an Assignment?

- 2.1 The research part

- 2.2 Planning your text

- 2.3 Writing major parts

- 3 Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

- 4 Will I succeed with my assignments?

- 5 Conclusion

How to Structure an Assignment?

To cope with assignments, you should familiarize yourself with the tips on formatting and presenting assignments or any written paper, which are given below. It is worth paying attention to the content of the paper, making it structured and understandable so that ideas are not lost and thoughts do not refute each other.

If the topic is free or you can choose from the given list — be sure to choose the one you understand best. Especially if that could affect your semester score or scholarship. It is important to select an engaging title that is contextualized within your topic. A topic that should captivate you or at least give you a general sense of what is needed there. It’s easier to dwell upon what interests you, so the process goes faster.

To construct an assignment structure, use outlines. These are pieces of text that relate to your topic. It can be ideas, quotes, all your thoughts, or disparate arguments. Type in everything that you think about. Separate thoughts scattered across the sheets of Word will help in the next step.

Then it is time to form the text. At this stage, you have to form a coherent story from separate pieces, where each new thought reinforces the previous one, and one idea smoothly flows into another.

Main Steps of Assignment Writing

These are steps to take to get a worthy paper. If you complete these step-by-step, your text will be among the most exemplary ones.

The research part