- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Essay and report writing skills

Course description

Course content, course reviews.

Writing reports and assignments can be a daunting prospect. Learn how to interpret questions and how to plan, structure and write your assignment or report. This free course, Essay and report writing skills, is designed to help you develop the skills you need to write effectively for academic purposes.

Course learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

- understand what writing an assignment involves

- identify strengths and weaknesses

- understand the functions of essays and reports

- demonstrate writing skills.

First Published: 10/08/2012

Updated: 26/04/2019

Rate and Review

Rate this course, review this course.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Create an account to get more

Track your progress.

Review and track your learning through your OpenLearn Profile.

Statement of Participation

On completion of a course you will earn a Statement of Participation.

Access all course activities

Take course quizzes and access all learning.

Review the course

When you have finished a course leave a review and tell others what you think.

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Related topics

- Critical thinking

- Finding information

- Understanding assessments

- Note-taking

- Time management

- Paraphrasing and quoting

- Referencing and avoiding plagiarism

See all available workshops .

Short on time? Watch a video on:

- Essay writing – 6:28

- Paraphrasing and quoting – 22:22

- Using active and passive voice – 9:58

- Editing your work – 5:12

Have any questions?

This is the footer

Report writing

Reports are informative writing that present the results of an experiment or investigation to a specific audience in a structured way. Reports are broken up into sections using headings, and can often include diagrams, pictures, and bullet-point lists. They are used widely in science, social science, and business contexts.

Scroll down for our recommended strategies and resources.

Difference between reports and essays

Essays and reports are both common types of university assignments. Whilst an essay is usually a continuous piece of writing, a report is divided into sections. See this overview for more on the differences between reports and essays:

Features of reports (University of Reading)

Reports have an expected structure with set sections so information is easy to find. Science reports may have methods and results sections, but business reports may only have a discussion and recommendations section. Always check what type of structure is needed for each report assignment as they may change. See this overview of different types of report structures:

Sample report structures (RMIT University)

Finding your own headings

Sometimes you are given the choice of how to name your sub-headings and structure the main body of your report. This is common in business where the structure has to fit the needs of the information and the client. See this short video on how to find meaningful sub-headings:

Finding your own report structure [video] (University of Reading)

Purpose of each section

Each section of a report has a different role to play and contains different types of information. See this brief overview of what goes where and how to number the sections:

What goes into each section (University of Hull)

Writing style

As well as having a different purpose, each report section is written in a different way and they don’t have to be written in order. See these guides on the style and order for writing a report and on the features of scientific writing:

Writing up your report (University of Reading)

Scientific writing (University of Leeds)

Tables and figures

Reports commonly use graphs and tables to show data more effectively. Always ensure any visual information in your report has a purpose and is referred to in the text. See this introductory guide to presenting data:

Using figures and charts (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Further resources

If you’d like to read more about the structure and style of reports, see this resource and book list created by Brookes Library:

Writing essays, reports and other assignments reading list

Back to top

Cookie statement

Report writing

- Features of good reports

- Types of Report

Introduction

Organising your information, abstract / executive summary, literature review, results / data / findings, reference list / bibliography.

- Writing up your report

Useful links for report writing

- Study Advice Helping students to achieve study success with guides, video tutorials, seminars and one-to-one advice sessions.

- Maths Support A guide to Maths Support resources which may help if you're finding any mathematical or statistical topic difficult during the transition to University study.

- Academic Phrasebank Use this site for examples of linking phrases and ways to refer to sources.

- Academic writing LibGuide Expert guidance on punctuation, grammar, writing style and proof-reading.

- Reading and notemaking LibGuide Expert guidance on managing your reading and making effective notes.

- Guide to citing references Includes guidance on why, when and how to use references correctly in your academic writing.

The structure of a report has a key role to play in communicating information and enabling the reader to find the information they want quickly and easily. Each section of a report has a different role to play and a writing style suited to that role. Therefore, it is important to understand what your audience is expecting in each section of a report and put the appropriate information in the appropriate sections.

The guidance on this page explains the job each section does and the style in which it is written. Note that all reports are different so you must pay close attention to what you are being asked to include in your assignment brief. For instance, your report may need all of these sections, or only some, or you may be asked to combine sections (e.g. introduction and literature review, or results and discussion). The video tutorial on structuring reports below will also be helpful, especially if you are asked to decide on your own structure.

- Finding a structure for your report (video) Watch this brief video tutorial for more on the topic.

- Finding a structure for your report (transcript) Read the transcript.

- When writing an essay, you need to place your information to make a strong argument

- When writing a report, you need to place your information in the appropriate section

Consider the role each item will play in communicating information or ideas to the reader, and place it in the section where it will best perform that role. For instance:

- Does it provide background to your research? ( Introduction or Literature Review )

- Does it describe the types of activity you used to collect evidence? ( Methods )

- Does it present factual data? ( Results )

- Does it place evidence in the context of background? ( Discussion )

- Does it make recommendations for action? ( Conclusion )

- the purpose of the work

- methods used for research

- main conclusions reached

- any recommendations

The introduction … should explain the rationale for undertaking the work reported on, and the way you decided to do it. Include what you have been asked (or chosen) to do and the reasons for doing it.

- State what the report is about. What is the question you are trying to answer? If it is a brief for a specific reader (e.g. a feasibility report on a construction project for a client), say who they are.

- Describe your starting point and the background to the subject: e.g., what research has already been done (if you have to include a Literature Review, this will only be a brief survey); what are the relevant themes and issues; why are you being asked to investigate it now?

- Explain how you are going to go about responding to the brief. If you are going to test a hypothesis in your research, include this at the end of your introduction. Include a brief outline of your method of enquiry. State the limits of your research and reasons for them, e.g.

Introduce your review by explaining how you went about finding your materials, and any clear trends in research that have emerged. Group your texts in themes. Write about each theme as a separate section, giving a critical summary of each piece of work, and showing its relevance to your research. Conclude with how the review has informed your research (things you'll be building on, gaps you'll be filling etc).

- Literature reviews LibGuide Guide on starting, writing and developing literature reviews.

- Doing your literature review (video) Watch this brief video tutorial for more on the topic.

- Doing your literature review (transcript) Read the transcript.

The methods should be written in such a way that a reader could replicate the research you have done. State clearly how you carried out your investigation. Explain why you chose this particular method (questionnaires, focus group, experimental procedure etc). Include techniques and any equipment you used. If there were participants in your research, who were they? How many? How were they selected?

Write this section concisely but thoroughly – Go through what you did step by step, including everything that is relevant. You know what you did, but could a reader follow your description?

Label your graphs and tables clearly. Give each figure a title and describe in words what the figure demonstrates. Save your interpretation of the results for the Discussion section.

The discussion ...is probably the longest section. It brings everything together, showing how your findings respond to the brief you explained in your introduction and the previous research you surveyed in your literature review. This is the place to mention if there were any problems (e.g. your results were different from expectations, you couldn't find important data, or you had to change your method or participants) and how they were, or could have been, solved.

- Writing up your report page More information on how to write your discussion and other sections.

The conclusions ...should be a short section with no new arguments or evidence. This section should give a feeling of closure and completion to your report. Sum up the main points of your research. How do they answer the original brief for the work reported on? This section may also include:

- Recommendations for action

- Suggestions for further research

If you're unsure about how to cite a particular text, ask at the Study Advice Desk on the Ground Floor of the Library or contact your Academic Liaison Librarian for help.

- Contact your Academic Liaison Librarian

The appendices ...include any additional information that may help the reader but is not essential to the report's main findings. The report should be able to stand alone without the appendices. An appendix can include for instance: interview questions; questionnaires; surveys; raw data; figures; tables; maps; charts; graphs; a glossary of terms used.

- A separate appendix should be used for each distinct topic or set of data.

- Order your appendices in the order in which you refer to the content in the text.

- Start each appendix on a separate page and label sequentially with letters or numbers e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B,…

- Give each Appendix a meaningful title e.g. Appendix A: Turnover of Tesco PLC 2017-2021.

- Refer to the relevant appendix where appropriate in the main text e.g. 'See Appendix A for an example questionnaire'.

- If an appendix contains multiple figures which you will refer to individually then label each one using the Appendix letter and a running number e.g. Table B1, Table B2. Do not continue the numbering of any figures in your text, as your text should be able to stand alone without the appendices.

- If your appendices draw on information from other sources you should include a citation and add the full details into your list of references (follow the rules for the referencing style you are using).

For more guidance see the following site:

- Appendices guidance from University of Southern California Detailed guidance on using appendices. Part of the USC's guide to Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper.

- << Previous: Types of Report

- Next: Writing up your report >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 8:51 AM

- URL: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/reports

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

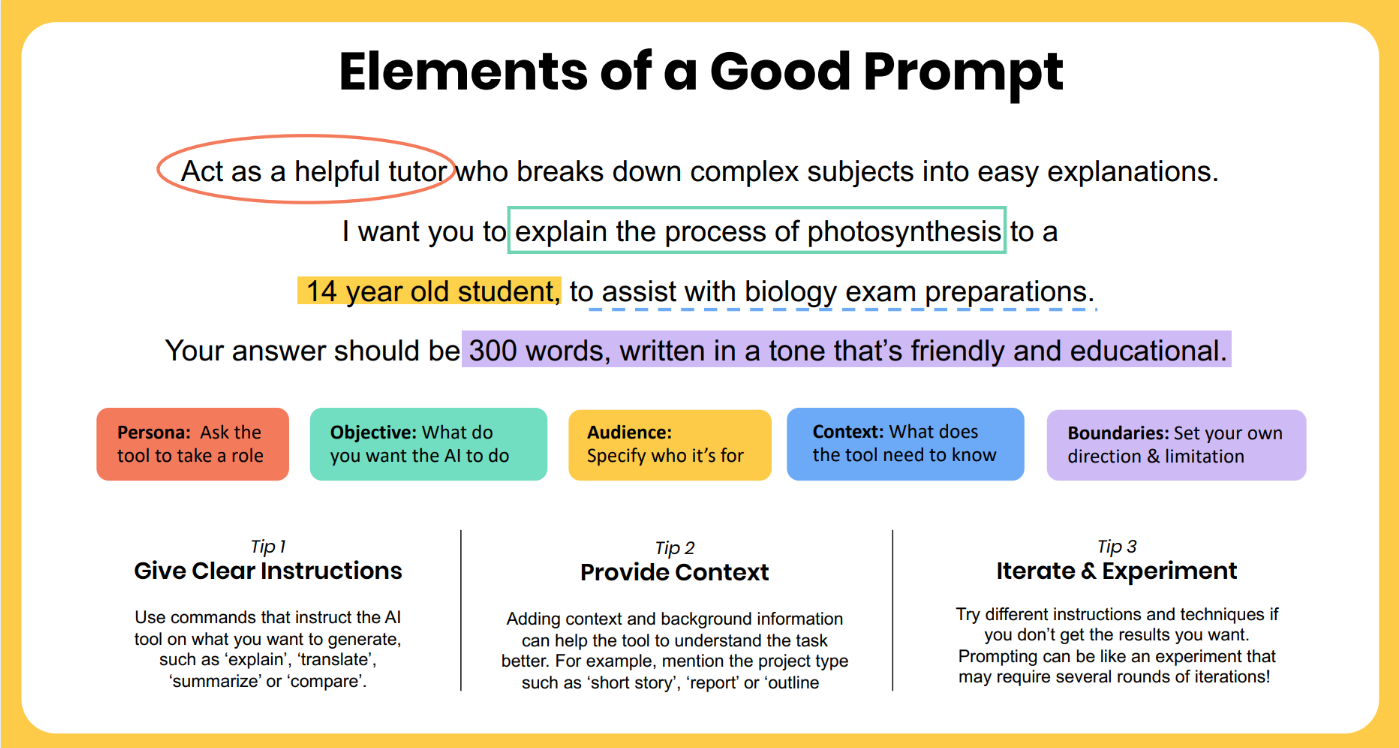

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

5 tips on writing better university assignments

Lecturer in Student Learning and Communication Development, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Alexandra Garcia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

University life comes with its share of challenges. One of these is writing longer assignments that require higher information, communication and critical thinking skills than what you might have been used to in high school. Here are five tips to help you get ahead.

1. Use all available sources of information

Beyond instructions and deadlines, lecturers make available an increasing number of resources. But students often overlook these.

For example, to understand how your assignment will be graded, you can examine the rubric . This is a chart indicating what you need to do to obtain a high distinction, a credit or a pass, as well as the course objectives – also known as “learning outcomes”.

Other resources include lecture recordings, reading lists, sample assignments and discussion boards. All this information is usually put together in an online platform called a learning management system (LMS). Examples include Blackboard , Moodle , Canvas and iLearn . Research shows students who use their LMS more frequently tend to obtain higher final grades.

If after scrolling through your LMS you still have questions about your assignment, you can check your lecturer’s consultation hours.

2. Take referencing seriously

Plagiarism – using somebody else’s words or ideas without attribution – is a serious offence at university. It is a form of cheating.

In many cases, though, students are unaware they have cheated. They are simply not familiar with referencing styles – such as APA , Harvard , Vancouver , Chicago , etc – or lack the skills to put the information from their sources into their own words.

To avoid making this mistake, you may approach your university’s library, which is likely to offer face-to-face workshops or online resources on referencing. Academic support units may also help with paraphrasing.

You can also use referencing management software, such as EndNote or Mendeley . You can then store your sources, retrieve citations and create reference lists with only a few clicks. For undergraduate students, Zotero has been recommended as it seems to be more user-friendly.

Using this kind of software will certainly save you time searching for and formatting references. However, you still need to become familiar with the citation style in your discipline and revise the formatting accordingly.

3. Plan before you write

If you were to build a house, you wouldn’t start by laying bricks at random. You’d start with a blueprint. Likewise, writing an academic paper requires careful planning: you need to decide the number of sections, their organisation, and the information and sources you will include in each.

Research shows students who prepare detailed outlines produce higher-quality texts. Planning will not only help you get better grades, but will also reduce the time you spend staring blankly at the screen thinking about what to write next.

During the planning stage, using programs like OneNote from Microsoft Office or Outline for Mac can make the task easier as they allow you to organise information in tabs. These bits of information can be easily rearranged for later drafting. Navigating through the tabs is also easier than scrolling through a long Word file.

4. Choose the right words

Which of these sentences is more appropriate for an assignment?

a. “This paper talks about why the planet is getting hotter”, or b. “This paper examines the causes of climate change”.

The written language used at university is more formal and technical than the language you normally use in social media or while chatting with your friends. Academic words tend to be longer and their meaning is also more precise. “Climate change” implies more than just the planet “getting hotter”.

To find the right words, you can use SkELL , which shows you the words that appear more frequently, with your search entry categorised grammatically. For example, if you enter “paper”, it will tell you it is often the subject of verbs such as “present”, “describe”, “examine” and “discuss”.

Another option is the Writefull app, which does a similar job without having to use an online browser.

5. Edit and proofread

If you’re typing the last paragraph of the assignment ten minutes before the deadline, you will be missing a very important step in the writing process: editing and proofreading your text. A 2018 study found a group of university students did significantly better in a test after incorporating the process of planning, drafting and editing in their writing.

You probably already know to check the spelling of a word if it appears underlined in red. You may even use a grammar checker such as Grammarly . However, no software to date can detect every error and it is not uncommon to be given inaccurate suggestions.

So, in addition to your choice of proofreader, you need to improve and expand your grammar knowledge. Check with the academic support services at your university if they offer any relevant courses.

Written communication is a skill that requires effort and dedication. That’s why universities are investing in support services – face-to-face workshops, individual consultations, and online courses – to help students in this process. You can also take advantage of a wide range of web-based resources such as spell checkers, vocabulary tools and referencing software – many of them free.

Improving your written communication will help you succeed at university and beyond.

- College assignments

- University study

- Writing tips

- Essay writing

- Student assessment

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

- Study and research support

- Academic skills

Report writing

What is a report and how does it differ from writing an essay? Reports are concise and have a formal structure. They are often used to communicate the results or findings of a project.

Essays by contrast are often used to show a tutor what you think about a topic. They are discursive and the structure can be left to the discretion of the writer.

Who and what is the report for?

Before you write a report, you need to be clear about who you are writing the report for and why the report has been commissioned.

Keep the audience in mind as you write your report, think about what they need to know. For example, the report could be for:

- the general public

- academic staff

- senior management

- a customer/client.

Reports are usually assessed on content, structure, layout, language, and referencing. You should consider the focus of your report, for example:

- Are you reporting on an experiment?

- Is the purpose to provide background information?

- Should you be making recommendations for action?

Language of report writing

Reports use clear and concise language, which can differ considerably from essay writing.

They are often broken down in to sections, which each have their own headings and sub-headings. These sections may include bullet points or numbering as well as more structured sentences. Paragraphs are usually shorter in a report than in an essay.

Both essays and reports are examples of academic writing. You are expected to use grammatically correct sentence structure, vocabulary and punctuation.

Academic writing is formal so you should avoid using apostrophes and contractions such as “it’s” and "couldn't". Instead, use “it is” and “could not”.

Structure and organisation

Reports are much more structured than essays. They are divided in to sections and sub-sections that are formatted using bullet points or numbering.

Report structures do vary among disciplines, but the most common structures include the following:

The title page needs to be informative and descriptive, concisely stating the topic of the report.

Abstract (or Executive Summary in business reports)

The abstract is a brief summary of the context, methods, findings and conclusions of the report. It is intended to give the reader an overview of the report before they continue reading, so it is a good idea to write this section last.

An executive summary should outline the key problem and objectives, and then cover the main findings and key recommendations.

Table of contents

Readers will use this table of contents to identify which sections are most relevant to them. You must make sure your contents page correctly represents the structure of your report.

Take a look at this sample contents page.

Introduction

In your introduction you should include information about the background to your research, and what its aims and objectives are. You can also refer to the literature in this section; reporting what is already known about your question/topic, and if there are any gaps. Some reports are also expected to include a section called ‘Terms of references’, where you identify who asked for the report, what is covers, and what its limitations are.

Methodology

If your report involved research activity, you should state what that was, for example you may have interviewed clients, organised some focus groups, or done a literature review. The methodology section should provide an accurate description of the material and procedures used so that others could replicate the experiment you conducted.

Results/findings

The results/findings section should be an objective summary of your findings, which can use tables, graphs, or figures to describe the most important results and trends. You do not need to attempt to provide reasons for your results (this will happen in the discussion section).

In the discussion you are expected to critically evaluate your findings. You may need to re-state what your report was aiming to prove and whether this has been achieved. You should also assess the accuracy and significance of your findings, and show how it fits in the context of previous research.

Conclusion/recommendations

Your conclusion should summarise the outcomes of your report and make suggestions for further research or action to be taken. You may also need to include a list of specific recommendations as a result of your study.

The references are a list of any sources you have used in your report. Your report should use the standard referencing style preferred by your school or department eg Harvard, Numeric, OSCOLA etc.

You should use appendices to expand on points referred to in the main body of the report. If you only have one item it is an appendix, if you have more than one they are called appendices. You can use appendices to provide backup information, usually data or statistics, but it is important that the information contained is directly relevant to the content of the report.

Appendices can be given alphabetical or numerical headings, for example Appendix A, or Appendix 1. The order they appear at the back of your report is determined by the order that they are mentioned in the body of your report. You should refer to your appendices within the text of your report, for example ‘see Appendix B for a breakdown of the questionnaire results’. Don’t forget to list the appendices in your contents page.

Presentation and layout

Reports are written in several sections and may also include visual data such as figures and tables. The layout and presentation is therefore very important.

Your tutor or your module handbook will state how the report should be presented in terms of font sizes, margins, text alignment etc.

You will need good IT skills to manipulate graphical data and work with columns and tables. If you need to improve these skills, try the following online resources:

- Microsoft online training through Linkedin Learning

- Engage web resource on using tables and figures in reports

Library Guides

Report writing: overview.

- Scientific Reports

- Business Reports

Reports are typical workplace writing. Writing reports as coursework can help you prepare to write better reports in your work life.

Reports are always written for a specific purpose and audience. They can present findings of a research; development of a project; analysis of a situation; proposals or solutions for a problem. They should inlcude referenced data or facts.

Reports should be structured in headings and sub-headings, and easy to navigate. They should be written in a very clear and concise language.

What makes a good report?

Following the instructions

You may have been given a report brief that provides you with instructions and guidelines. The report brief may outline the purpose, audience and problem or issue that your report must address, together with any specific requirements for format or structure. Thus, always check the report guidelines before starting your assignment.

An effective report presents and analyses evidence that is relevant to the specific problem or issue you have been instructed to address. Always think of the audience and purpose of your report.

All sources used should be acknowledged and referenced throughout. You can accompany your writing with necessary diagrams, graphs or tables of gathered data.

The data and information presented should be analysed. The type of analysis will depend on your subject. For example, business reports may use SWOT or PESTLE analytical frameworks. A lab report may require to analyse and interpret the data originated from an experiment you performed in light of current theories.

A good report has a clear and accurately organised structure, divided in headings and sub-headings. The paragraphs are the fundamental unit of reports. (See boxes below.)

The language of reports is formal, clear, succinct, and to the point. (See box below.)

Writing style

The language of reports should be:

Formal – avoid contractions and colloquial expressions.

Direct – avoid jargon and complicated sentences. Explain any technical terms.

Precise – avoid vague language e.g. 'almost' and avoid generalisations e.g. 'many people'

Concise – avoid repetition and redundant phrases. Examples of redundant phrases:

- contributing factor = factor

- general consensus = consensus

- smooth to the touch = smooth

Strong paragraphs

Paragraphs, and namely strong paragraphs, are an essential device to keep your writing organised and logical.

A paragraph is a group of sentences that are linked coherently around one central topic/idea. Paragraphs should be the building blocks of academic writing. Each paragraph should be doing a job, moving the argument forward and guiding your reading through your thought process.

Paragraphs should be 10-12 lines long, but variations are acceptable. Do not write one-sentence long paragraphs; this is journalistic style, not academic.

You need to write so-called strong paragraphs wherein you present a topic, discuss it and conclude it, as afar as reasonably possible. Strong paragraphs may not always be feasible, especially in introductions and conclusions, but should be the staple of the body of your written work.

Topic sentence : Introduces the topic and states what your paragraph will be about

Development : Expand on the point you are making: explain, analyse, support with examples and/or evidence.

Concluding sentence : Summarise how your evidence backs up your point. You can also introduce what will come next.

PEEL technique

This is a strategy to write strong paragraphs. In each paragraph you should include the following:

P oint : what do you want to talk about?

E vidence : show me!

E valuation : tell me!

L ink : what's coming next?

Example of a strong paragraph, with PEEL technique:

Paragraph bridges

Paragraphs may be linked to each other through "paragraph bridges". One simple way of doing this is by repeating a word or phrase.

Check the tabs of this guide for more information on writing business reports and scientific reports.

Report Structure

Generally, a report will include some of the following sections: Title Page, Terms of Reference, Summary, Table of Contents, Introduction, Methods, Results, Main body, Conclusion, Recommendations, Appendices, and Bibliography. This structure may vary according to the type of report you are writing, which will be based on your department or subject field requirements. Therefore, it is always best to check your departmental guidelines or module/assignment instructions first.

You should follow any guidelines specified by your module handbook or assignment brief in case these differ, however usually the title page will include the title of the report, your number, student ID and module details.

Terms of Reference

You may be asked to include this section to give clear, but brief, explanations for the reasons and purpose of the report, which may also include who the intended audience is and how the methods for the report were undertaken.

(Executive) Summary

It is often best to write this last as it is harder to summarise a piece of work that you have not written yet. An executive summary is a shorter replica of the entire report. Its length should be about 10% of the length of the report,

Contents (Table of Contents)

Please follow any specific style or formatting requirements specified by the module handbook or assignment brief. The contents page contains a list of the different chapters or headings and sub-headings along with the page number so that each section can be easily located within the report. Keep in mind that whatever numbering system you decide to use for your headings, they need to remain clear and consistent throughout.

Introduction

This is where you set the scene for your report. The introduction should clearly articulate the purpose and aim (and, possibly, objectives) of the report, along with providing the background context for the report's topic and area of research. A scientific report may have an hypothesis in addition or in stead of aims and objectives. It may also provide any definitions or explanations for the terms used in the report or theoretical underpinnings of the research so that the reader has a clear understanding of what the research is based upon. It may be useful to also indicate any limitations to the scope of the report and identify the parameters of the research.

The methods section includes any information on the methods, tools and equipment used to get the data and evidence for your report. You should justify your method (that is, explain why your method was chosen), acknowledge possible problems encountered during the research, and present the limitations of your methodology.

If you are required to have a separate results and discussion section, then the results section should only include a summary of the findings, rather than an analysis of them - leave the critical analysis of the results for the discussion section. Presenting your results may take the form of graphs, tables, or any necessary diagrams of the gathered data. It is best to present your results in a logical order, making them as clear and understandable as possible through concise titles, brief summaries of the findings, and what the diagrams/charts/graphs or tables are showing to the reader.

This section is where the data gathered and your results are truly put to work. It is the main body of your report in which you should critically analyse what the results mean in relation to the aims and objectives (and/or, in scientific writing, hypotheses) put forth at the beginning of the report. You should follow a logical order, and can structure this section in sub-headings.

Conclusion

The conclusion should not include any new material but instead show a summary of your main arguments and findings. It is a chance to remind the reader of the key points within your report, the significance of the findings and the most central issues or arguments raised from the research. The conclusion may also include recommendations for further research, or how the present research may be carried out more effectively in future.

Recommendations

You can have a separate section on recommendations, presenting the action you recommend be taken, drawing from the conclusion. These actions should be concrete and specific.

The appendices may include all the supporting evidence and material used for your research, such as interview transcripts, surveys, questionnaires, tables, graphs, or other charts and images that you may not wish to include in the main body of the report, but may be referred to throughout your discussion or results sections.

Bibliography

Similar to your essays, a report still requires a bibliography of all the published resources you have referenced within your report. Check your module handbook for the referencing style you should use as there are different styles depending on your degree. If it is the standard Westminster Harvard Referencing style, then follow these guidelines and remember to be consistent.

Formatting reports

You can format your document using the outline and table of contents functions in Word

- Next: Scientific Reports >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2023 10:14 AM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/report-writing

CONNECT WITH US

Writing Development

- How we can help you

- reflective writing

- dissertations

- literature reviews

- assignment toolkit

- Exams & revision

- Critical thinking

- Postgraduates

- Skills for study

When you are set a report as an assignment, you will do some form of investigation and then write up the results showing:

- what you did

- how you did it

- what you found out

- why your findings are important

Reports have a formal structure, with sections and headings, but there are many different types of report, such as business reports, lab reports, site visits and research reports and there are various possible structures. Therefore, you must check your module guide (or ask your tutor) to find out how you are expected to set out your report.

Reports will often include sections such as:

- Abstract - a short section summarising the report (although this is the first section of the report, you should write it last)

- Introduction - explains why you are writing the report and gives the background

- Literature review

- Methods - a short description on how you did your research

- Results - a very short section giving the results (don't explain them in this section)

- Discussion -

- Conclusion - your analysis of your findings

- Recommendation - your suggestions about how things could be improved

- Report writing This advice is generic - you must check your assignment brief for any guidelines from your tutors

ebooks we recommend

print books we recommend

Guide to Report Writing

- Report Writing

- << Previous: essays

- Next: reflective writing >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 9:29 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/aws

- Admin login

- ICT Support Desk

- Policy Statement

- www.lincoln.ac.uk

- Accessibility

- Privacy & Disclaimer

The Higher Education Review

- Engineering

- Jobs and Careers

- Media and Mass Communication

- Education Consultancy

- Universities

How to Write a Report for University Assignment

Download now complete list of top private engineering colleges.

More from Swinburne University

- Giving to Swinburne

- Student login

- Staff login

- Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences

- Built Environment and Architecture

- Engineering

- Film and Television

- Games and Animation

- Information Technology

- Media and Communication

- Trades and Apprenticeships

- Study online

- Transition to university from VCE

- Direct entry into university

- Returning to study

- Vocational Education and Training at Swinburne

- Early Entry Program

- University entry requirements

- Transferring to Swinburne

- Recognition of prior learning in the workplace

- Study Abroad in Melbourne

- Study support for indigenous students

- Guaranteed pathways from TAFE

- Short courses

- University certificates

- Pre-apprenticeships

- Apprenticeships

- Associate degrees

- Bachelor degrees

- Double degrees

- Certificates

- Traineeships

- Trade short courses

- Doctor of Philosophy

- Master degrees

- Graduate diploma courses

- Graduate certificate courses

- Studying outside of Australia

- Study on campus

- Loans and discounts for local students

- Fees for international students

- Fees for local students

- Student Services and Amenities Fee

- Scholarship conditions

- Scholarships for international students

- How to apply as a local student

- How to apply for a research degree

- How to apply as an international student

- Apply as an asylum seeker or refugee

- How to enrol

- Understanding your university offer

- Course planner

- Setting up your class timetable

- Enrol as a PhD or master degree student

- Why study in Australia?

- Plan your arrival in Melbourne

- Arriving in Melbourne

- Things to do in Melbourne

- Getting around Melbourne

- Money, living costs and banking in Australia

- International student stories

- Student email, password and Wi-Fi access

- Your student ID card and Swinburne login

- Student discounts and concessions

- Special consideration and extensions

- Accommodation

- Study and learning support

- Health and wellbeing

- Support for international students

- Independent advocacy for service

- Indigenous student services

- Financial support and advice

- AccessAbility services

- Legal advice for students

- Spiritual Wellbeing

- Assault reporting and help

- Asylum seeker and refugee support

- Care leaver support

- LGBTIQ+ community support

- Childcare for the Swinburne community

- Industry-linked projects

- Internships

- Student stories

- Professional Degrees

- Industry study tours

- Get paid to podcast

- Real industry experience stories

- Overseas exchange

- Overseas study tours

- Overseas internships

- Students currently overseas

- Improve your employability

- Career services

- Professional Purpose program

- Partner Stories

- Hosting students with disabilities

- Work with our accreditation placement students

- Benefits of working with our students

- Apprenticeships and traineeships

- Workshops, events and outreach programs

- Work experience

- Knox Innovation, Opportunity and Sustainability Centre

- Australian Synchrotron Science Education

- PrimeSCI! science education

- Student projects

- Meet our facilitators

- Meet our consultants

- Meet our leadership and management teams

- Learning design and innovation

- Hybrid working solutions

- Training needs analysis

- Why partner with Swinburne

- 4 simple steps to setting up a partnership

- Achievements and success stories

- Research engagement

- Facilities and equipment

- Achievements and recognition

- Iverson Health Innovation Research Institute

- Social Innovation Research Institute

- Space Technology and Industry Institute

- Innovative Planet Research Institute

- Research centres, groups and clinics

- Platforms and initiatives

- Indigenous research projects

- Animal research

- Biosafety and Defence

- Data management

- Funding from tobacco companies

- Human research

- Intellectual property

Assignment writing guides and samples

If you're looking for useful guides for assignment writing and language skills check out our range of study skills resources

Essay writing

- Writing essays [PDF 240KB] . Tips on writing a great essay, including developing an argument, structure and appropriate referencing.

- Sample essay [PDF 330KB] . A sample of an essay that includes an annotated structure for your reference.

Writing a critical review

- Writing a critical review [PDF 260KB] . Tips on writing a great critical review, including structure, format and key questions to address when writing a review.

- Sample critical review [PDF 260KB] . A sample of a critical review that includes an annotated structure for your reference.

Writing a business-style report

- Writing a business-style report [PDF 330KB] . A resource for business and law students Find out how to write and format business-style reports.

- Sample of a business-style report [PDF 376 KB] . A resource for business and law students. A sample of a business-style report with an annotated format.

Investigative report sample

- Sample of an investigative report [PDF 500KB] . A resource for science, engineering and technology students. How to write an investigative report, including an annotated format.

Assignment topics and editing

- Interpreting assignment topics [PDF 370 KB] . Find out how to interpret an assignment topic, including understanding key words and concepts.

- How to edit your work [PDF 189KB] . A guide for all students about how to edit and review their work.

Language skills

- Building your word power (expanding your knowledge of words) [PDF 306KB]. A guide to expanding your knowledge of words and communicating your ideas in more interesting ways.

- Handy grammar hints [PDF 217KB] . A guide to getting grammar and style right in your assignments.

Resources relevant to your study area

Science, engineering and technology.

- Writing a critical review [PDF 260KB]. Tips on writing a great critical review, including structure, format and key questions to address when writing a review.

- Sample critical review [PDF 260KB] . A sample of a critical review that includes an annotated structure for your reference.

- Sample of an investigative report [PDF 500KB] . A resource for science, engineering and technology students. How to write an investigative report, including an annotated format.

- How to edit your work [PDF 189KB] . A guide for all students about how to edit and review their work.

- Building your word power (expanding your knowledge of words) [PDF 306KB]. A guide to expanding your knowledge of words and communicating your ideas in more interesting ways.

- Handy grammar hints [PDF 217KB] . A guide to getting grammar and style right in your assignments.

Health, Arts and Design

- Sample essay [PDF 330KB] . A sample of an essay that includes an annotated structure for your reference.

- Writing a critical review [PDF 260KB]. Tips on writing a great critical review, including structure, format and key questions to address when writing a review.

- Sample critical review [PDF 260KB]. A sample of a critical review that includes an annotated structure for your reference.

- How to edit your work [PDF 189KB] . A guide for all students about how to edit and review their work.

- Handy grammar hints [PDF 217KB]. A guide to getting grammar and style right in your assignments.

Business and Law

- Sample essay [PDF 330KB]. A sample of an essay that includes an annotated structure for your reference.

- Writing a business-style report [PDF 330KB]. A resource for business and law students. Find out how to write and format business-style reports.

- Sample of a business-style report [PDF 376 KB]. A resource for business and law students. A sample of a business-style report, with an annotated format.

- Interpreting assignment topics [PDF 370 KB]. Find out how to interpret an assignment topic, including understanding key words and concepts.

- How to edit your work [PDF 189KB]. A guide for all students about how to edit and review their work.

Writing your assignment

The Writing your assignment resource is designed and monitored by Learning Advisers and Academic Librarians at UniSA.

The purpose of a report is to investigate an issue and 'report back' findings which allow people to make decisions or take action and depending on your course. The report may require you to record, to inform, to instruct, to analyse, to persuade, or to make specific recommendations, so it is important to check your task instructions and identify the approach you are required to take. Your completed report should consist of clear sections which are labelled with headings and sub-headings, and are logically sequenced, well developed and supported with reliable evidence . In this section you will learn more about writing a report, including process, structure and language use. The report writing checklist at the end of this section can help you finalise your report.

- The main purpose of a report is usually to investigate an issue and report back with suggestions or recommendations to allow people to make decisions or take action.

- You will need to find information on the issue by reading through course materials and doing further research via the UniSA Library and relevant databases.

- Report writing requires you to plan and think, so give yourself enough time to draft and redraft, and search for more information before you complete the final version.

- The report is typically structured with an introduction, body paragraphs, a conclusion and a reference list.

- It usually has headings and subheadings to organise the information and help the reader understand the issue being investigated, the analysis of the findings and the recommendations or implications that relate directly to those findings.

- A report can also include dot points or visuals such as graphs, tables or images to effectively present information.

- Always check the task instructions and feedback form as there might very specific requirements for the report structure.

Locate the task instructions in your course outline and/or on your course site, and use this activity to plan your approach.

- Reports overview (pdf)

- Using headings in your writing (pdf)

- Abstracts and introductions (pdf)

- Writing introductions (pdf)

- Writing paragraphs (pdf)

- Literature reviews (pdf)

- Writing conclusions (pdf)

- Constructing graphs, tables and diagrams (pdf)

- Psychology example report (pdf)

- More example reports (link)

Click through the slides below to learn about the key characteristics of academic writing.

- Academic vocabulary and phrases (pdf)

- Expressing yourself clearly and concisely (pdf)

- Tentative language (pdf)

- Writing objectively (pdf)

- Academic phrasebank - Courtesy: Uni of Manchester (link)

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

Assignment types

You will encounter many different assignment types throughout your studies, each with unique challenges and requirements. While the structure guide gives you the building blocks to create an assignment in general, this guide covers the distinct structures and characteristics of different assignment types and common errors that students make.

In brief, each assignment type has a different purpose and, as a result, different elements are required for each:

- A case study involves an in-depth examination of a specific subject or scenario, analysing its complexities and offering insights into real-world problems or situations.

An essay is a written work that presents a coherent argument, analysis, or discussion on a particular topic.

- A literature review is a critical analysis of existing research on a specific topic.

A report is a structured document that systematically gathers, analyses, and presents information on a specific topic, issue, event, or research question.

- Reflective writing encourages individuals to reflect upon and explore their thoughts, experiences, opinions, and emotions on a particular topic, event, or subject matter.

- Other written assignment types you may be assessed on at university are discussion board posts, blog posts, portfolios, creative assignments, annotated bibliographies, group projects and presentations.

Case studies

A case study involves an in-depth examination of a specific subject or scenario, analysing its complexities and offering insights into real-world (or hypothetical) problems or situations. Often, it will focus on a representative person, group of people, or other samples. A case study will generally relate to theories or methods in your chosen field of study and their applications in the broader context of your discipline. It is common for case studies to be focused on solving a particular problem and thus include potential solutions to problems or recommendations for action.

The purpose of a case study is to apply theoretical knowledge to real-world situations and is valuable in helping you prepare for professional practice. They require you to think critically, analyse complex issues, and develop effective problem-solving skills.

Case studies are divided into sections with subheadings, allowing the reader to jump to specific points of interest. This allows you to present information you have gathered or researched about a particular topic in a way your reader easily understands.

There are different types of case studies and ways to structure the information, so it is important to check your assignment instructions, suggested structure, and assessment criteria/marking rubric.

Structure of a case study

A typical case study will be structured as follows:

Introduction

The introduction of your case study should provide a concise overview of your study’s subject, background, and objectives. Clearly state the problem or issue you will be addressing and outline the purpose of the case study.

Literature review (optional)

In this section, you establish the context for your investigation. Critically examine existing research and scholarly articles relevant to your case study topic. Identify key theories, concepts, and findings that inform your study. Analyse the gaps or controversies in the literature that your case study aims to address.

In the discussion section, interpret and analyse your findings about the existing literature. Explore the implications of your results and discuss any limitations or constraints in your study. Consider alternative explanations for your findings and address their significance. Engage in a critical reflection on the strengths and weaknesses of your approach.

Conclusion/recommendations

Conclude your case study by summarising the key findings and their implications. Recommend future research or practical applications based on your study’s outcomes. Clearly state your case study’s contributions to the existing body of knowledge and suggest avenues for further exploration.

List all the sources cited in your case study. Ensure that you adhere to the correct referencing style specified by your instructor. Pay careful attention to the accuracy and formatting of your references, as this enhances the credibility and professionalism of your work.

Appendices (if necessary)

Attach any supplementary materials, such as raw data, questionnaires, or additional information that supports and complements your case study. Ensure that each appendix is labelled and referenced appropriately within the main text.

Common mistakes

- Insufficient background information

- Main issues not clearly defined

- Theory has not been applied sufficiently

- Analysis is superficial

- Recommendations are poorly supported.

If you need help with any of these areas, view the rest of the writing guide or book an appointment with a Peer Academic Mentor .

While most essays aim to inform the reader about a particular topic, the specific purpose will depend on the type of essay.

- Persuasive essays seek to convince readers of a specific viewpoint or argument.

- Argumentative essays are a subset of persuasive essays and aim to present a clear argument supported by evidence. They often address counterarguments.

- Analytical essays focus on breaking down a complex topic or issue into its constituent parts and examining them critically.

- Descriptive essays use vivid language and sensory details to paint a picture or create a mental image of a person, place, object, or experience.

- Narrative essays tell a story or recount a personal experience.

- Expository essays aim to explain or clarify a topic, concept, or process in a straightforward and informative manner.

Thesis statements

A fundamental part of any essay is a thesis statement.

A thesis statement is a concise, specific sentence that articulates the main point or claim of an essay or research paper. It serves as a roadmap for your readers, outlining the central idea you will explore and support throughout your writing.

It is recommended that you create a simple thesis statement before you begin writing to help create a roadmap for your work. As you construct your work, you should revise and refine it as necessary.

Example thesis statement

Ultimately, artificial intelligence will benefit humankind; however, precautions should be taken to mitigate potential harm. This can be accomplished in several ways, including government regulations for the ethical collection and use of data, increased education for the public on the use of AI, and investment in job protection for our future workforce.

To create a strong thesis statement, you should:

- Understand your assignment , including identifying the main topic or question you will address in your paper.

- In one or two sentences, express the primary message you want to convey in your paper. A good way to do this is to reword the assignment question.

- Review the statement to make sure it is not too vague or general. Ambiguous thesis statements can lead to unclear or unfocused essays.

- Take a stand – a strong thesis statement should go beyond stating facts and should express a debatable position that you will support and defend in your paper. If you find this challenging, consider making a list of how you feel about the topic. What do you believe? Brainstorming may help with this.

- Avoid announcement statements. Your thesis shouldn’t announce your topic but present an arguable point about it. Instead of saying, ‘This essay will discuss [topic], make a claim about the topic.

Essay structure

A typical essay will be structured as follows:

The introduction of your essay serves as the roadmap for your reader. Begin with a compelling hook to grab attention, then provide context for your topic, articulate the thesis statement (your essay’s main argument or purpose), and outline the key points you will address in the body. The introduction sets the tone and establishes the direction for the entire essay.

The body of your essay is where you present your argument, evidence, and analysis. Each paragraph should focus on a specific idea or aspect of your thesis statement. Start with a clear topic sentence, support it with evidence or examples, and then provide analysis or interpretation to demonstrate how it relates to your overall argument. Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs, creating a cohesive flow that guides the reader through your logical progression of ideas.