Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 February 2020

A novel selection strategy for antibody producing hybridoma cells based on a new transgenic fusion cell line

- Martin Listek 1 ,

- Anja Hönow 1 ,

- Manfred Gossen 2 , 3 &

- Katja Hanack 1 , 4

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 1664 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

17 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Antibody generation

- Assay systems

The use of monoclonal antibodies is ubiquitous in science and biomedicine but the generation and validation process of antibodies is nevertheless complicated and time-consuming. To address these issues we developed a novel selective technology based on an artificial cell surface construct by which secreted antibodies were connected to the corresponding hybridoma cell when they possess the desired antigen-specificity. Further the system enables the selection of desired isotypes and the screening for potential cross-reactivities in the same context. For the design of the construct we combined the transmembrane domain of the EGF-receptor with a hemagglutinin epitope and a biotin acceptor peptide and performed a transposon-mediated transfection of myeloma cell lines. The stably transfected myeloma cell line was used for the generation of hybridoma cells and an antigen- and isotype-specific screening method was established. The system has been validated for globular protein antigens as well as for haptens and enables a fast and early stage selection and validation of monoclonal antibodies in one step.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Fast and Sensitive Luciferase-based Assay for Antibody Engineering and Design of Chimeric Antigen Receptors

Integrating SpyCatcher/SpyTag covalent fusion technology into phage display workflows for rapid antibody discovery

Development of a new affinity maturation protocol for the construction of an internalizing anti-nucleolin antibody library

Introduction.

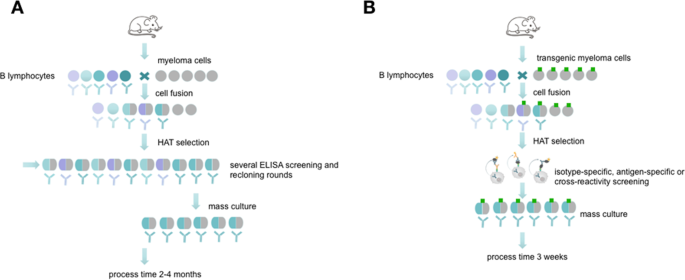

Antibodies are well known as universal binding molecules with a high specificity for their corresponding antigens and have found, therefore, widespread use in very many different areas of biology and medicine 1 . Most murine antibodies are produced today by means of the hybridoma technique as monoclonal antibodies 2 or with the help of antibody gene libraries and display techniques as recombinant antibody fragments 3 . Both methods have intrinsic advantages but also difficulties such that they are restricted to specialized laboratories and companies. Currently, the reliability of monoclonal antibodies was critically discussed in several publications 4 , 5 which is related to a growing demand of better validation and characterization of these molecules 6 , 7 , 8 . Especially the hybridoma technique which results in full-length monoclonal antibodies can be cumbersome, labour-intensive and time-consuming (Fig. 1A ). Although several improvements have been tried in the course of the past years, the basic method is still very similar to the original method published by Köhler and Milstein 9 , 10 , 11 . The critical issue in the development of antigen-specific hybridomas is the lack of any direct connection between the hybridoma cell and the released antibody. Therefore, it is necessary to perform limited dilution techniques in order to separate single cells to ensure monoclonality. Unfortunately, this process could not be combined with a simultaneous, proper validation of the desired antibodies because the concentration in the supernatants are often very low at the early beginning of culture.

Schematic overview about conventional hybridoma technology compared side by side to the new selection approach. The picture (reprinted by permission from Springer Nature 10 ) shows the process of monoclonal antibody generation via conventional hybridoma technology ( A ) and via the new selection approach using transgenic fusion cell lines ( B ). The fusion with transgenic myeloma cells allows a fast and efficient hybridoma screening in an isotype- or antigen-specific manner and allows an early screening for possible cross-reactivities.

To facilitate the isolation of specific antibody-producing hybridomas, a method has to be established which temporarily restricts the cells from releasing the antibody into the culture medium and thus retaining the genotype (the antibody-coding genes) and the phenotype (the produced antibodies) in one entity. Such precondition can easily be fulfilled when recombinant antibody fragments are isolated, e.g. by phage display techniques. To confer this basic principle to the hybridoma technique would require to capture the synthesized antibody on the surface of the synthesizing hybridoma cell (Fig. 1B ). To realize this, a covalent surface labeling of antibody-producing cells with biotin was accomplished in the past, which allowed the isolation of specific cells by means of avidin- or streptavidin-conjugated ligands binding the released antibodies 12 . However, chemical surface labeling is very often unpredictable and may disturb normal functions and the vitality of the cells.

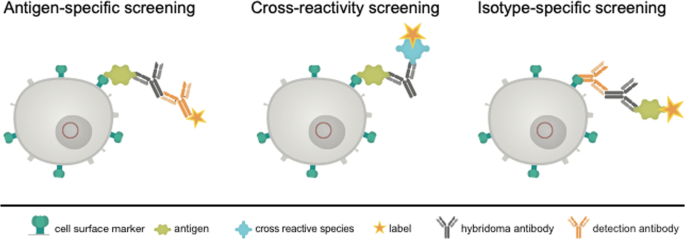

We, therefore, tried to replace this principle by a more gentle method. We transfected the myeloma cells to be used for hybridoma fusion with a construct enabling the expression of a surface marker containing the acceptor peptide (AP) sequence for site-specific biotinylation by biotin ligase (BirA) 13 . Such a surface marker, after in vitro biotinylation, should be applicable for the isolation of antigen-specific antibody-producing hybridoma, allowing for a built-up of a bridge e.g. with the streptavidin-conjugated antigen or isotype-specific antibody, which in turn catches the produced antibody, and a labeled indicator anti-immunoglobulin or antigen (Fig. 2 ). The system allows a combination of three possible sorting options. The antigen-specific approach (Fig. 2 , left) is performed by an antigen-avidin complex bound to the biotinylated cell. The antigen is specifically recognized by the secreted antibody and the detection takes place via a secondary antibody labelled to a fluorescent dye. This approach can be extended to a cross-reactivity screening (Fig. 2 , middle panel), where different antigen-avidin complexes can be linked to the cell surface and the secreted antibodies can be tested for a specific binding. This approach is also transferable to the isotype-specific approach shown in Fig. 2 on the right panel. Here, an isotype-specific antibody, such as an anti-IgG antibody, coupled to avidin, is linked to the cell surface. The secreted antibody, in case it is an IgG, is caught and the dye-coupled antigen is used for fluorescence detection. In dependance of the antigen and the selection principle all three options can be combined or performed consecutively. This principle allows a fast and specific sorting of antigen-specific hybridoma cells 10 days after HAT selection and avoids laborious limited dilution techniques and ELISA screenings.

Schematic view of the proposed selection principle. Shown is a transgenic hybridoma cell line (in grey) with an artificial marker construct (HA-AP-EGF-R, in dark green) present on the cell surface. The genetic construct (red circle) contains a truncated variant of the human immature EGF-receptor (EGF-R), a hemagglutinin epitope (HA) and a biotin acceptor peptide (AP). The secreted hybridoma antibody (black) can be linked to the corresponding cell by binding to the antigen (light green) or to an isotype-specific detection antibody either (orange). Sorting of specific hybridomas is performed by using appropriate labels conjugated to a secondary antibody or to the antigen of interest.

In order to realize this principle a suitable gene construct was designed and transfected into myeloma cells to establish a cell line stably expressing the construct on the cell surface. The next steps were to prove that the expression pattern did not change significantly after fusion of the transfected myelomas with B lymphocytes and that the system can indeed be used to isolate specific antibody-producing hybridomas. The results shown here prove that an easy and efficient selection of specific antibody-producing cells is possible with this novel method.

HA-AP-EGF-R expression on transfected myeloma cells

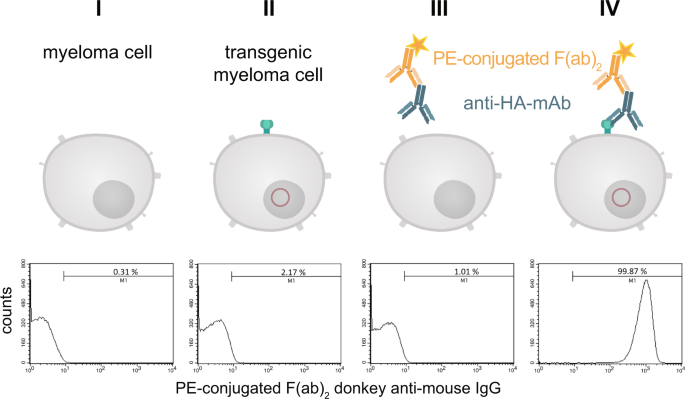

The construct to be used for transfection (Fig. 3 ) contained the signal peptide of the immature human EGF-R followed by the hemagglutinin epitope (HA) containing the biotin acceptor peptide (AP) and the extracellular domain and transmembrane domain of the mature human EGF-R (aa 1-651). The elements were chosen because the EGF-R is one of the best characterized receptors in literature and it is known which truncated versions still provide a faithful transmembrane localisation, while being devoid of signalling activity. The latter is important to prevent unwanted interference with intracellular signalling upon ectopic transgene expression 14 , 15 , 16 . The HA epitope was used as detection element to visualize the marker on the surface of the cells and the AP sequence is necessary for the biotinylation. The transfection of myeloma cells performed by transposase-mediated gene transfer resulted in stable expression of HA-AP-EGF-R on the cell surface. This could be shown by a monoclonal anti-HA.11 antibody and a phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG in flow cytometry experiments. Over 99% of the transfected cells could be positively stained for the artificial cell surface construct (Fig. 4IV ).

Vector design of the artificial cell surface receptor. To express the HA-AP-EGF-receptor fusion protein on the surface of myeloma cells, the signal peptide of the immature human EGF-receptor was inserted at the N-terminus of the cloned hemagglutinin epitope (HA) containing a biotin acceptor peptide (AP) sequence, and a truncated variant of the mature humane EGF-receptor (aa 1-651) at its C-terminus. The construct is controlled by the EF1α-promoter.

Detection of the HA-tag on the cell surface of transfected myeloma cells. Stable transfected and non-transfected myeloma cells (1 × 10 6 ) were stained with a monoclonal anti-HA.11 antibody and a PE-labeled F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG. After staining and washing the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Non-stained cells served as negative control. To exclude non-living cells a staining with 7-AAD was performed. The histograms represent all living cells from this approach with 1 × 10 5 recorded events. Analysis was performed by using BD CellQuest Pro software version 6.0.

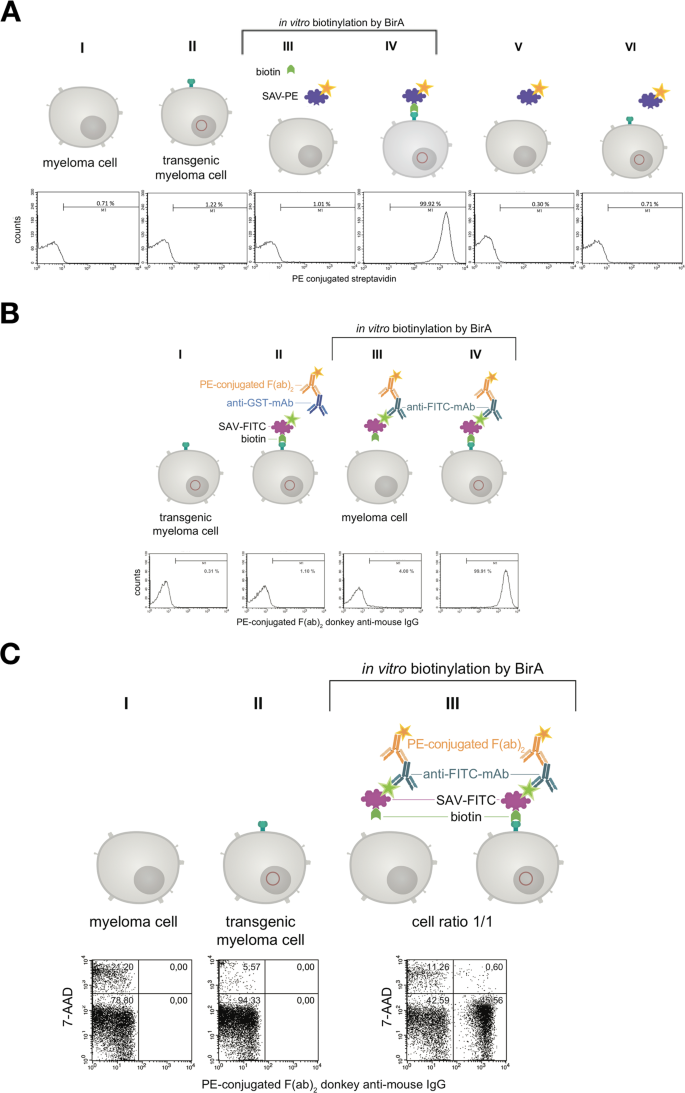

In the next step the binding of PE-conjugated streptavidin (SAV) to the myeloma cell surface after biotinylating the artificial surface marker was verified by flow cytometry as shown in Fig. 5A . Over 99% of cell population IV showed a positive staining compared to non-transfected control cells. When using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated SAV, the mouse monoclonal anti-FITC antibody B13-DE1 and a PE-labeled F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG, over 99% of the cells could be stained (Fig. 5B ). After receptor-expressing and non-expressing myeloma cells were mixed in equal numbers and the same treatment was performed, i.e. FITC-conjugated SAV, mouse monoclonal anti-FITC antibody B13-DE1 and PE-labeled F(ab) 2 fragment (donkey anti-mouse IgG), about 45% of the cells were stained, which was the expected ratio used in the initial experiment (Fig. 5C ). These experiments showed clearly the specific labeling of the cells. The same results were obtained when using ovalbumin-conjugated SAV, external monoclonal anti-ovalbumin antibodies and PE-labeled F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG (data not shown) showing that it is feasible to apply the system both for haptens as well as globular proteins.

Characterization of the artificial receptor functions on myeloma cells. ( A ) The biotin acceptor peptide (AP) is accessible on the surface of stably transfected myeloma cells. Transfected and non-transfected myeloma cells (1 × 10 6 ) were used for BirA mediated biotinylation. The cells in approaches III & IV were incubated with a mixture consisting of 5 mM MgCl 2 , 1 mM ATP, 10 µM Biotin and 0.789 µg BirA. The cells in approaches I, II, V, VI were incubated without BirA. To investigate whether BirA mediated biotinylation reaction was successful and specific, the cells (III, IV, V, VI) were treated with PE-conjugated streptavidin (2 µg/mL). After staining and washing cells were analyzed and 2.5 × 10 4 events were recorded by flow cytometry. Non-stained cell served as negative control. Dead cells were excluded by 7-AAD-staining. Analysis was performed by using BD CellQuest Pro software version 6.0. ( B ) The artificial receptor as bridge between phenotype and genotype. To investigate whether the HA-AP-EGF-R is a suitable tool to retain a soluble antibody at the surface of biotinylated transfected cells, a stable bridge was constructed between the receptor, an antigen and the antibody. Fluorescein was used as antigen which was bound to the surface as FITC-labeled SAV (2 µg/mL). The monoclonal mouse anti-fluorescein antibody B13-DE1 was used as antibody to be bound. As an isotype control a mouse anti-GST antibody (1 µg/1 × 10 6 cells) was used. A PE-conjugated F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG diluted in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA was used as indicator antibody. Dead cells were excluded by staining with 7-AAD and 1 × 10 4 events were recorded. Analysis was performed by using BD CellQuest Pro software version 6.0. ( C ) Antigen loaded HA-AP-EGF-R+ myeloma cells can be identified within a heterogeneous cell population. Transfected and non-transfected myeloma cells (1 × 10 6 ) were mixed together in a cell ratio of 1/1 followed by in vitro biotinylation reaction. The cells from approach III were incubated with a mixture of 5 mM MgCl 2 , 1 mM ATP, 10 µM Biotin and 0.789 µg BirA. The cells from approaches I and II were incubated without BirA. Following that the heterogeneous cell pool was incubated with a FITC-labeled SAV-conjugate (2 µg/mL). After this, the cells were labeled with B13-DE1 (1 µg/1 × 10 6 cells) and a PE-conjugated F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG. Non-stained cells served as negative control and dead cells were excluded by staining with 7-AAD. 1 × 10 4 events were recorded and analysed by using BD CellQuest Pro software version 6.0.

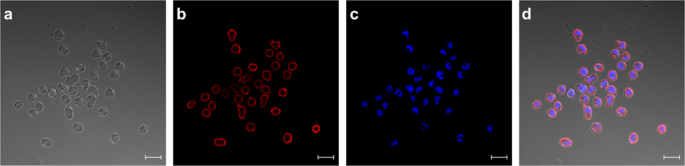

In the next experiments we showed, that the receptor expression did not cease after fusing the transfected myeloma cells with lymphocytes from mice (Fig. 6 , Panel III). In order to visualize receptor expression on biotinylated hybridoma cells fluorescence was performed with PE-conjugated SAV (Fig. 7 ). Panel 7d showed a merge of differential interference contrast, DAPI- and PE-conjugated SAV staining which presents the expected stained surface corona on all cells imaged.

The artificial cell surface receptor is present after cell fusion and HAT selection on the surface of hybridoma cells. Transgenic and non-transgenic hybridoma cells (1 × 10 6 ) were used for in vitro biotinylation. The cells from approach III and IV were incubated with a mixture of 5 mM MgCl 2 , 1 mM ATP, 10 µM Biotin and 0.789 µg BirA. The cells from approach I and II were incubated without BirA. BirA mediated biotinylation was screened by treating the cells (III, IV) with PE-conjugated streptavidin (2 µg/mL). After staining and washing the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Non-stained cell served as negative control. Dead cells were excluded by staining with 7-AAD. 2 × 10 4 events were recorded and analysed by using BD CellQuest Pro software version 6.0.

Staining of HA-AP-EGF-R bearing hybridoma cells. HA-AP-EGF-R bearing hybridoma cells were stained for receptor expression using PE-conjugated streptavidin. DAPI-staining was performed in panel c. Both stainings were merged in panel d together with panel a which represents the differential interference contrast picture. Immunofluorescence pictures were taken with an LSM 880 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) with a 20 µm size bar.

Selection of ovalbumin-specific hybridomas

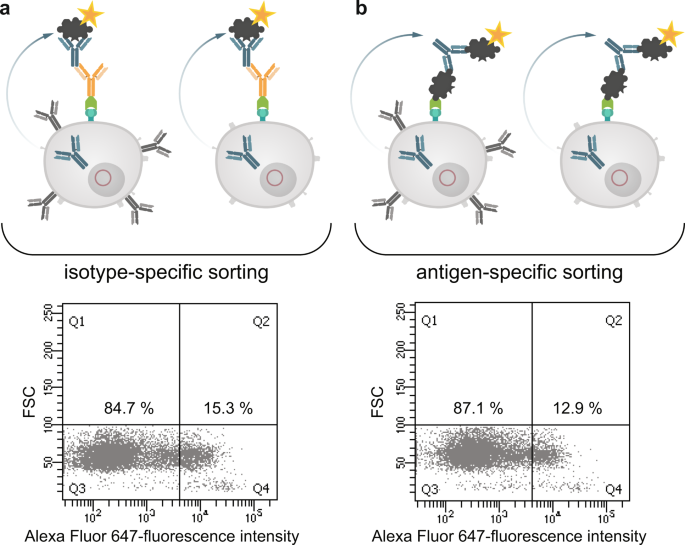

The results revealed that the new fusion cell line should be suitable to identify antigen-specific hybridomas by cell sorting. In order to prove this directly, we performed an ovalbumin-specific fusion and combined an isotype- and antigen-specific sorting two weeks after fusion. Figure 8a shows the corresponding dot plot of hybridoma cells sorted with the isotype-specific approach. Out of 1 × 10 6 cells from the fusion pool and after gating it was possible to stain 15.3% of the cells specifically with the isotype-specific approach which corresponds to a cell number of 49,000 cells. With the antigen-specific approach 12.9% (41,500 cells) of the cells could be stained specifically (Fig. 8b ). Positive sorted cells from both sortings were exemplarily single-cell plated in one 96-well plate and tested by ELISA. We could detect an ovalbumin-specific signal in each cavity showing outgrowth of sorted hybridoma cells (data not shown).

Isotype-specific as well as antigen-specific labeling of antibody producing hybridomas. Antibody producing HA-AP-EGF-R+ hybridoma cells (1 × 10 6 ) were biotinylated in vitro by BirA and incubated with an avidin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG specific antibody (panel a) or with ovalbumin conjugated to avidin (panel b) for 20 min at 4 °C. For antibody production and secretion the hybridoma cells were washed (PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA at 300 × g for 10 min) and incubated in full growth media for 3 h at 37 °C and 6% CO 2 . After incubation the cells were washed by using PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA at 300 × g for 10 min and incubated with an Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated ovalbumin (10 µg/1 × 10 6 cells) for 20 min at 4 °C as indicator of antigen-specific captured antibodies. Dead cells were excluded by 7-AAD staining. 1 × 10 4 events were recorded and analysed by using BD FACSDiva version 8.0.

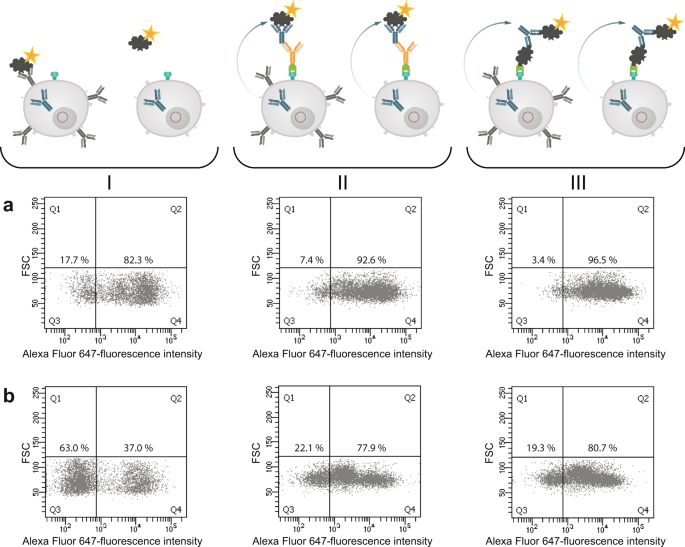

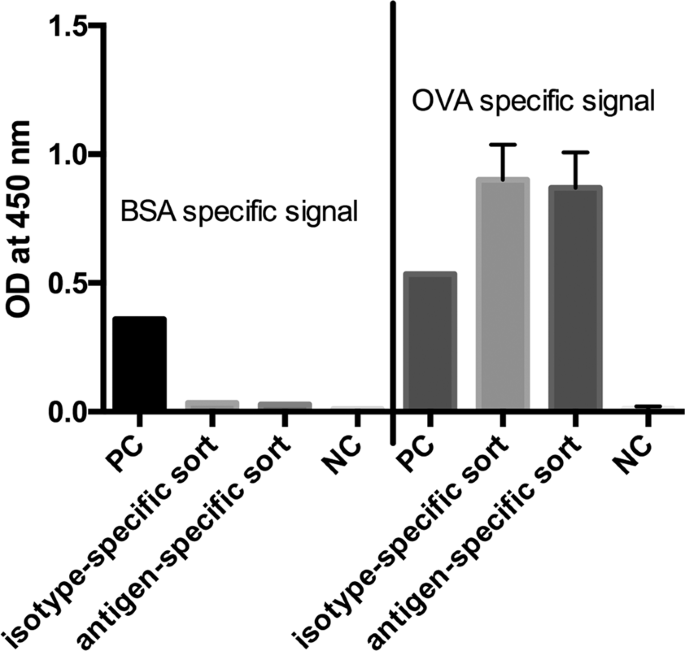

In the next step we analyzed both cell pools again with different sorting options after one week of culture (Fig. 9 ). In order to see wether the B cell receptor (BCR) itself is influencing the sorting procedure we labelled the cells with antigen only. In panel I fluorescently labeled ovalbumin was used to identify antigen-specific BCR + hybridomas. In the isotype-specific approach (Fig. 9a ) 82.3% of the cells could be stained specifically whereas 17.7% were negative in binding the antigen (panel Ia). For cells sorted with the antigen-specific approach before we obtained a different result (Fig. 9b ). Here, 63% of the population were negative in binding fluorescently labeled ovalbumin whereas only 37% were positive (panel Ib). This indicates, that nearly two thirds of the population do not carry an antigen-specific BCR on the cell surface and these could not be detected with just labelled antigen. In comparison to panel IIb and IIIb where 78% and 80% of the cells could be selected positive, the outcome of specific hybridomas could be doubled by using our new approach. Also for the isotype-specific staining it was obvious that the outcome of positive hybridomas could be further increased from 82.3% to 96.5%. These results showed that a specific labelling process independent from the BCR on the cell surface is more reliable and allows a subsequent selection of antigen-specific hybridomas already two weeks after fusion. It is well known, that the BCR itself is not presented stably on the cell surface and that internalization after polyvalent antigen binding is a common event 17 . In a further experiment, the culture supernatants of both sortings were tested in an indirect ELISA for ovalbumin specificity and cross-reactivity to bovine serum albumine (BSA) (Fig. 10 ). In contrast to the specific signal for ovalbumin no cross-reactive binding could be detected for BSA.

Comparison of three different sorting options for selecting specific hybridoma cells. Hybridoma cells sorted isotype-specific (panel a) and antigen-specific (panel b) were analyzed again with (I) fluorescent labeled ovalbumin, (II) isotype-specific and (III) antigen-specific via HA-AP-EGF-R. Panel I shows the results when the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated ovalbumin (10 µg/1 × 10 6 cells) alone without using the HA-AP-EGF-R construct. In Panel (II,III) the isotype- and antigen-specific sorting was performed as described. Positive cells were displayed in Q4. Dead cells were excluded by 7-AAD staining. 1 × 10 4 events were recorded and analysed by using BD FACSDiva version 8.0.

Indirect ELISA for ovalbumin and BSA specificity. Culture supernatants of the isotype- and antigen-specific approach were tested for specific antibody production by immobilizing ovalbumin and BSA to a microtiter plate (10 µg/mL). The detection of specific antibody responses was performed by an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody and TMB as substrate. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a reference at 630 nm. Values are given as single measurement for positive controls (PC), BSA-specific signals and negative control (NC) for BSA. Ovalbumin specific signals and NC for ovalbumin were performed twofold. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Conclusions

In this article we describe a novel and highly effective method for the selection of antigen-specific hybridoma cells based on a new transgenic myeloma cell line. The cell line carries an artificial cell surface marker for isotype- and antigen-specific binding of produced antibodies and enables therefore a smart and fast selection and validation procedure for antigen-specific hybridomas. The field of monoclonal antibody generation via hybridoma technology is still plagued by long screening processes and suboptimal selection methods 18 and it is rarely possible to validate selected antibodies at an early stage. A further issue is that the outcome of antigen-specific B lymphocytes depends on the individual host immune response and the composition of the immunizing antigen. This can dramatically influence the process afterwards. However, the third aspect in this field is the complex process of cell fusion and stable growth of hybridomas as such. With an input of approximately 8 × 10 7 cells prior fusion and an outcome of 10–20 hybridomas producing a suitable monoclonal antibody this process seems to be one of the most ineffective processes known in biotechnology (efficiency of 0.000025%). In order to address this unsatisfactory situation and to find a method which can provide an efficient screening and an early validation of antibodies we developed a system for linking the genotype and the phenotype of the cell which leads to an efficient linking of the produced antibody to the corresponding hybridoma cell. With this system it is possible to simultaneously handle all positive hybridomas after fusion and to screen for antigen- and isotype-specificity in parallel. Further, the system can be flexibly used to screen e.g. for cross-reactivities when the antigen is replaced by other targets of interest.

This antigen-specific hybridoma selection reminds of the method proposed by Manz et al . 12 but avoids the chemical cell surface labeling, so that the method described here will be much more reliable and easier to be performed. There are alternative selection methods available as described earlier by Browne et al . such as LEAP (laser-enabled analysis and processing technology) 19 , 20 , gel microdrop technology 21 , semisolid media 22 or droplet based microfluidic assays 23 , 24 but all these methods require an encapsulation of cells which leads to physical stress and low efficiencies with regard to high throughput production of monoclonal antibodies. Selection methods for antibody-producing hybridoma cells based on flow cytometry are described since 1979 25 and are used today effectively with some improvements as reviewed in 26 . Nevertheless, with the exception of the droplet based assays these methods often require hybridoma cells which express the antigen-specific BCR on the cell surface in order to label the corresponding cell. Depending on the B cell differentiation at the time point of spleen cell isolation for fusion it is often the case that the generated hybridoma cells do not express BCRs anymore and so these selection methods are not suitable for those hybridomas even when they secrete highly specific antibody molecules. Further, there are several studies published where it could be shown that BCR expression depends on culture medium conditions and cell numbers 27 , cell cycle 28 , 29 or secretion intensity 30 . When staining with just labelled antigen alone we could select cells but these underwent apoptosis after sorting (data not shown). Therefore, sorting via the BCR itself seems not a feasible method to identify antigen-specific hybridomas. Another method published by Pierce et al . 31 described a transgenic myeloma cell line expressing Igα and Igß on the cell surface, so that the membrane-bound form of the secreted antibody could be caught and used for a flow cytometry based screening. This system is also dependent on the B cell status at the time of fusion and could lead to BCR-clustering and internalization and therefore could induce cell death as described by Li et al . 32 . Our developed approach is independent on BCR expression and is therefore suitable for all hybridomas generated by the fusion process. We could show that the method is applicable for low- and high-molecular weight substances such as FITC and ovalbumin, so that the basis for anti-hapten antibody and anti-protein antibody selections can be provided. Of course, the question raised, if negative cells were positively stained when secreted antigen-specific antibodies bound to the surface receptor of a neighboring cell. We have investigated different secretion temperatures and time periods and found an optimum at 37 °C for 3 h. We could not detect any significant labeling of non-producers. Further, we could transfer this selection principle to HEK293 and CHO cells in order to allow an efficient screening of cells expressing recombinant proteins and introduced BirA into the vector construct, so that the cells are able to biotinylate themselves (data not shown). The described technology in this study allows a fast and efficient identification of desired antibody-producing cells and a flexible validation with regard to isotype-specificity and cross-reactivities. In ongoing studies the focus is shifted to different classes of antigens such as transfected cells, nucleic acids or whole microorganisms to show the general feasibility of the system.

Cell line and cell culture

Murine non-secreting myeloma Sp2/0 cells (ATCC CRL-1581) were cultured under 6% CO 2 , at 37 °C and 95% humidity by using DMEM full growth media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine, 50 µM ß-mercaptoethanol and 0.1 mg/mL gentamycine.

Design of the surface marker gene construct HA-AP-EGF-R

To express the HA-AP-EGF-receptor fusion protein on the surface of the Sp2/0 mammalian cells, we inserted the signal peptide of the immature human EGF-receptor at the N-terminus of the cloned hemagglutinin epitope (HA) containing a biotin acceptor peptide (AP) sequence, and a truncated variant of the mature human EGF-receptor (aa 1-651) at its C-terminus (Fig. 3 ). The EGF receptor signal peptide (forward primer 5′ATATA GGTACC GCCACCATGCGACCCTCCG 3′ KpnI, reverse primer 5′ATTAT AAGCTT AGACGAGCCTTCCTCCAGAGCC 3′ HindIII), the HA-AP sequence (forward primer 5′CATGA AAGCTT GGCTCGTCTGGGTATCCATATGATG 3′ Hind III, reverse primer 5′CTAAT GGTAGC CGGCGCGCCCTCG 3′ NheI) as well as the whole extracellular domain and transmembrane domain of the mature human EGF-receptor (forward primer 5′ATAGA GCTACC GGAAGCAGCGGGCTGGAGGAAAAGA 3′ NheI, reverse primer 5′CATAA GCGGCCGC TTACCGAACGATGTGG 3′ NotI) were amplified by standard PCR techniques from the pcDNA3.1 EGF-R-YFP plasmid (this was a kind gift of Stefan Kubick, Fraunhofer Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Potsdam-Golm) and the pDisplay AP-CFP-TM plasmid (this was a kind gift of A. Ting, Department of Chemistry Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts). Following that, the DNA fragments were cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCEP4 (Invitrogen, Paisley). Finally, the whole gene construct (HA-AP-EGF-R) was subcloned into a pPB EF1α vector 33 , such that expression of the artificial receptor from the piggyBac transposon is under control of the human elongation factor 1 alpha promoter. The integration of the HA-AP-EGF-receptor fusion gene into the vector was confirmed by sequencing (GATC Biotech AG, Konstanz). The signal peptide cleavage efficiency was determined by using the SignalP 4.0 model 34 and the membrane topology of the fusion protein was analyzed and predicted by using HMMTOP 35 , 36 .

Generation of stably HA-AP-EGF-R-transfected Sp2/0 cells

Two days prior transfection, 1.5 × 10 4 living Sp2/0 cells were plated into each well of a 6-well plate and cultured as described above. At the day of transfection the culture supernatant was discarded and replaced by 2 mL of freshly prepared culture medium and the culture dish was further incubated at 37 °C under 6% CO 2 . The transfection with the surface marker-expressing gene construct HA-AP-EGF-R was conducted according to Kuroda et al . 37 and Cardinos and Bradley 38 . Briefly, to obtain a special ratio between donor and helper plasmid, 2 µg of the plasmid pPB EF1a HA-AP-EGF-R (donor plasmid) were supplemented with 0.2 µg of the transposase plasmid (mPB, helper plasmid) and filled up to 100 µL with 150 mM NaCl (plasmid DNA mixture). Moreover 8 µL of PEI (polyethylenimin) stock solution (7.5 mM in water, pH 7.4) were diluted in 92 µL 150 mM NaCl (PEI mixture). After 10 min incubation at room temperature (RT) the PEI mixture was added to the plasmid DNA mixture and further incubated at RT for 10 min. The solution was added dropwise to the cells while gently shaking the plate. The cells were then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under 6% CO 2 . After this treatment, the culture supernatant was replaced by fresh growth medium and the cells were cultured for another 24 h at 37 °C under 6% CO 2 . The growth medium was then exchanged by selection medium (DMEM with 10% (v/v) FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 50 µM ß-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mg/mL gentamycine and 25 µg/mL puromycin). After 7 days of puromycin selection the resistant colonies were expanded and incubated under reduced puromycin concentrations (3 µg/mL).

Isolation and enrichment of HA-AP-EGF-R-expressing Sp2/0 cells

Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) was chosen to enrich puromycin-resistant cells that express and display the HA-AP-EGF-R on the cell surface. Therefore, puromycin-resistant cells were harvested. An aliquot of 5 × 10 6 living cells was applied to the magnetic labeling procedure and incubated with the primary antibody (1 µg of a mouse anti-HA.11 monoclonal antibody per 1 × 10 6 cells, Covance, MMS-101R, Munich) for 30 min at 4 °C. Further treatment was performed according to the manufacturer´s instruction by using the MACS Miltenyi Biotec Anti-Mouse IgG MicroBeads kit (130-048-401, lot number 5161103197, Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). Briefly, the cells were washed twice after labeling with the primary antibody by using PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA (MACS buffer) at 300 × g for 10 min. Following that, the magnetic labeling procedure was conducted by resuspending the cell pellet in 100 µL MACS buffer and adding 10 µL of the anti-mouse IgG microbeads suspension. After a 15 min incubation step at 4 °C the cells were washed twice by using MACS buffer. For the magnetic separation step the cell pellet was resuspended in MACS buffer and the suspension was added on a MACS column. Beforehand the MACS column was placed in the magnetic field of a suitable MACS separator. After the execution of the positive separation the cell suspension was washed once with MACS buffer and, following that, the cell pellet was resuspended in fresh growth culture media. The cells were cultured at 37 °C under 6% CO 2 .

Antibody treatment of HA-AP-EGF-R-expressing Sp2/0 cells

The cells were treated with antibodies in suspension and washed by centrifugation. Antibodies and secondary reagents were diluted in PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA. As washing solution PBS, pH 7.4, 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA was used.

In vitro biotinylation of the surface receptor HA-AP-EGF-R by the biotin ligase BirA

A constant amount of stably transfected living cells was used for the in vitro biotinylation as described by Chen et al . 12 . The cell supernatant was discarded and the cells were washed twice with PBS supplemented with 5 mM MgCl 2 . Following that, the cells were incubated with a mixture consisting of 5 mM MgCl 2, 1 mM ATP, 10 µM Biotin and 0.789 µg per 1 × 10 6 cells BirA (GeneCopoeia™ Source BioScience LifeSciences, Nottingham UK) for 30 min. To get rid of the reaction mixture, the cells were washed four times with PBS containing 5 mM MgCl 2 . To investigate the transfected cells by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD), transfected and biotinylated cells were treated with PE-conjugated streptavidin (2 µg/mL; eBioscience, UK).

Flow cytometry analysis of using the artificial receptor as bridge between the phenotype and genotype

To investigate whether the HA-AP-EGF-R is a suitable tool to retain a soluble antibody at the surface of the biotinylated transfected cells, a stable bridge was constructed between the receptor, an antigen and the antibody. Fluorescein was used as antigen which was bound to the surface as FITC-labeled SAV (2 µg/mL) (eBioscience, Hatfield UK) and the monoclonal mouse anti-fluorescein antibody B13-DE1 39 was used as antibody to be bound. A PE-conjugated F(ab) 2 fragment of a donkey anti-mouse IgG (12-4012, eBioscience, UK) diluted in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA was used as indicator antibody.

Fusion and HAT selection of HA-AP-EGF-R-containing Sp2/0 cells with spleen lymphocytes from ovalbumin immunized Balb/c mice

The hybridoma technique was used to analyze the cell surface expression behavior of the HA-AP-EGF-R fusion protein after fusion of a transfected Sp2/0 cell with spleen lymphocytes from an ovalbumin immunized Balb/c mouse. Immunization was performed according to the relevant national and international guidelines. The study was approved by the Ministry of Environment, Health and Consumer Production of the Federal State of Brandenburg (reference number V3-2347-A16-4-2012). Briefly, Balb/c mice (8–12 wks old) were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 µg ovalbumin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in 200 µL PBS supplemented with 50 µL Complete Freund´s Adjuvant (CFA). The fusion was conducted according to Köhler and Milstein 11 with an electrofusion modification 40 . Briefly, spleen lymphocytes were mixed in a ratio of 3 to 1 with transfected myeloma cells that bear the artificial cell surface fusion protein and were washed three times with fusion buffer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 4 mM CaCl 2 , 2.5 mM MgCl 2 , 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.2 µm). The cell pellet was dissolved in 200 µL fusion buffer and filled up to a final volume of 400 µL with 25% (w/v) PEG8000 in fusion buffer. The cell suspension was transferred into a fusion cuvette and placed into the electro fusion device. The cells were pulsed with 600 V for 25 ms. Three minutes post pulse the cell suspension was transferred into 37 °C pre-warmed full growth media supplemented with 20% (v/v) FCS and cultured for 5 h at 37 °C and 95% humidity under 6% CO 2 . Following that, HAT medium ( h ypoxanthine; 27.24 µg/mL, a zaserine; 2 µg/mL and t hymidine; 7.76 µg/mL) was added to the cell suspension. Finally the cell suspension was transferred into T75 flasks and further cultured at 37 °C and 95% humidity under 6% CO 2 . HAT selection was performed for 10 days. Growing hybrids were then checked for HA-AP-EGF-R surface receptor expression and secretion of ovalbumin-specific antibodies as described below.

Isotype- and antigen-specific sorting of HA-AP-EGF-R+ hybridoma cells

Ten days after fusion HA-AP-EGF-R+ hybridoma cells were sorted either isotype- or antigen-specific. Therefore, the cells were first biotinylated in vitro with 0.5 mM biotin for 48 h at 37 °C and 6% CO 2 . After this, the cells were harvested and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 10 6 cells/mL. For the isotype-specific labeling the cells were washed twice with MACS buffer and incubated with a goat anti-mouse IgG specific antibody (115-005-164, lot number 128439, Dianova, Germany) conjugated to avidin (20 µg/mL) for 20 min at 4 °C. For the antigen-specific screening the cells were labeled with ovalbumin conjugated to avidin (Invitrogen, 20 µg/mL) for 20 min at 4 °C. After this incubation, the cells were washed again with 10 mL MACS buffer, the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL full growth cell culture media supplemented with 20% (v/v) FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 50 µM ß-mercaptoethanol and the cells were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C and 6% CO 2 to allow antibody secretion and binding to the HA-AP-EGF-R construct. After incubation the cells were washed with 10 mL MACS buffer. The cell pellet was resuspended in 300 µL MACS buffer and 10 µg ovalbumin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen, 2 mg/mL diluted in PBS) were added per sample (for 20 min at 4 °C). For panel I in Fig. 8a,b the cells were incubated only with 10 µg ovalbumin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647. After this, the cells were washed twice with 10 mL MACS buffer, the pellet was resuspended in 500 µL MACS buffer supplemented with 3 µL 7-AAD (BD Biosciences, 100 µg/mL diluted in MACS buffer) and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C. The sample volume was adapted to 1 mL and analyzed by a flow cytometer (BD FACS Aria III, Becton Dickinson, Germany).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

In order to detect the antigen-specificity and cross-reactivity of secreted antibodies an indirect ELISA was performed. Briefly, microtiter plates (greiner-bio one, Frickenhausen, Germany) were coated with 10 µg/mL ovalbumin and bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in PBS (50 µL/well) overnight at 4 °C in a humid chamber. The wells were washed three times with tap water and blocked with PBS/NCS (5% neonatal calf serum, 50 µL/well) for 30 min at RT. After this, the wells were washed again and 50 µL/well culture supernatant from selected hybridomas were added and incubated for 1 h at RT. After washing a secondary goat anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Lot number 129410, Dianova) was used for detection. The plates were incubated for 45 min at RT. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) solution (0.12 mg/mL TMB with 0.04% hydrogen peroxide in 25 mM NaH 2 PO 4 ) was used as substrate. The reaction was stopped after 5 min with 1 M H 2 SO 4 . Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm with a reference of 630 nm.

Flow cytometry stainings were statistically validated by using BD CellQuest Pro software version 6.0 and BD FACSDiva software version 8.0. Graph Pad prism 6 was used for representing the ELISA data shown in Fig. 10 .

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Burton, D. R. & Wilson, I. A. Immunology. Square-dancing antibodies. Sci. 317 (5844), 1507–8 (2007).

CAS Google Scholar

Alkan, S. S. Monoclonal antibodies: the story of a discovery that revolutionized science and medicine. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4 (2), 153–6 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Geyer, C. R., McCafferty, J., Dübel, S., Bradbury, A. R. & Sidhu, S. S. Recombinant antibodies and in vitro selection technologies. Methods Mol. Biol. 901 , 11–32 (2012).

Bradbury, A. & Plückthun, A. Standardize antibodies used in research. Nat. 518 (7537), 27–9 (2015).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Baker, M. Reproducibility crisis: Blame it on the antibodies. Nat. 521 (7552), 274–6 (2012).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Reiss, P. D., Min, D. & Leung, M. Y. Working towards a consensus for antibody validation. F1000Res 3 (266), 2014–6 (2014).

Google Scholar

Freedman, L. P. et al . The need for improved education and training in research antibody usage and validation practices. Biotechniques 61 (1), 16–8 (2016).

Pauly, D. & Hanack, K. How to avoid pitfalls in antibody use. F1000Res 4 , 691 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Zhang, C. Hybridoma technology for the generation of monoclonal antibodies. Methods Mol. Biol. 901 , 117–135 (2012).

Hanack, K., Messerschmidt, K. & Listek, M. Antibodies and selection of monoclonal antibodies. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 917 , 11–22 (2016).

Köhler, G. & Milstein, C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nat. 256 (5517), 495–7 (1975).

Manz, R., Assenmacher, M., Pflüger, E., Miltenyi, S. & Radbruch, A. Analysis and sorting of live cells according to secreted molecules, relocated to a cell-surface affinity matrix. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92 (6), 1921–5 (1995).

Chen, I., Howarth, M., Lin, W. & Ting, A. Y. Site-specific labeling of cell surface proteins with biophysical probes using biotin ligase. Nat. Methods 2 (2), 99–104 (2005).

Zhen, Y., Caprioli, R. M. & Staros, J. V. Characterization of glycosylation sites of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Biochem. 42 (18), 5478–92 (2003).

Jorisson, R. N. et al . Epidermal growth factor receptor: mechanisms of activation and signalling. Exp. Cell Res. 284 (1), 31–53 (2003).

He, C., Hobert, M., Friend, L. & Carlin, C. The epidermal growth factor receptor juxtamembrane domain has multiple basolateral plasma membrane localization determinants, including a dominant signal with a polyproline core. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (41), 38284–93 (2002).

Lanzavecchia, A. Receptor-mediated uptake and its effect on antigen presentation to class II-restricted T lymphocytes. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 8 , 73–93 (1990).

Tomita, M. & Tsumoto, K. Hybridoma technologies for antibody production. Immunotherapy 3 (3), 371–80 (2011).

Browne, S. M. & Al-Rubeai, M. Selection methods for high-producing mammalian cell lines. Trends Biotechnol. 25 (9), 425–432 (2007).

Caroll, S. & Al-Rubeai, M. The selection of high-producing cell lines using flow cytometry and cell sorting. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 4 (11), 1821–9 (2004).

Dharshanan, S. & Hung, C. S. Screening and subcloning of high producer transfectomas using semisolid media and automated colony picker. Methods Mol. Biol. 1131 , 105–12 (2014).

Weaver, J. C., McGrath, P. & Adams, S. Gel microdrop technology for rapid isolation of rare and high producer cells. Nat. Med. 3 (5), 583–5 (1997).

El Debs, B., Utharala, R., Balyasnikova, I. V., Griffiths, A. D. & Merten, C. A. Functional single-cell hybridoma screening using droplet-based microfluidics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109 (29), 11570–5 (2012).

Eyer, K. et al . Single-cell deep phenotyping of IgG-secreting cells for high-resolution immune monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 35 (10), 977–982 (2017).

Parks, D. R., Bryan, V. M., Oi, V. T. & Herzenberg, L. A. Antigen-specific identification and cloning of hybridomas with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76 (4), 1962–6 (1979).

Mattanovich, D. & Borth, N. Applications of cell sorting in biotechnology. Microb. Cell Fact. 5 , 12 (2006).

McKinney, K. L., Dilwith, R. & Belfort, G. Manipulation of heterogeneous hybridoma cultures for overproduction of monoclonal antibodies. Biotechnol. Prog. 7 (5), 445–54 (1991).

Kromenaker, S. J. & Srienc, F. Cell cycle kinetics of the accumulation of heavy and light chain immunoglobulin proteins in a mouse hybridoma cell line. Cytotechnology 14 (3), 205–18 (1994).

Charlet, M., Kromenaker, S. J. & Srienc, F. Surface IgG content of murine hybridomas: Direct evidence for variation of antibody secretion rates during the cell cycle. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 47 (5), 535–40 (1995).

Meilhoc, E., Wittrup, K. D. & Bailey, J. E. Application of flow cytometric measurement of surface IgG in kinetic analysis of monoclonal antibody synthesis and secretion by murine hybridoma cells. J. Immunol. Methods 121 (2), 167–74 (1989).

Pierce, P. W. et al . Engineered cell surface expression of membrane immunoglobulin as a means to identify monoclonal antibody-secreting hybridomas. J. Immunol. Methods 31 (343), 28–41 (2002).

Li, C., Siemasko, K., Clark, M. R. & Song, W. Cooperative interaction of Iga and Igb of the BCR regulates the kinetics and specificity of antigen targeting. Int. Immunol. 14 (10), 1179–1191 (2002).

Werner, J. & Gossen, M. Modes of TAL effector-mediated repression. Nucleic Acid. Res. 42 (21), 13061–73 (2014).

Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G. & Nielsen, H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8 (10), 785–6 (2011).

Tusnády, G. E. & Simon, I. Principles governing amino acid composition of integral membrane proteins: application to topology prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 283 (2), 489–506 (1998).

Tusnády, G. E. & Simon, I. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinforma. 17 (9), 849–850 (2001).

Kuroda, H., Marino, M. P., Kutner, R. H. & Reiser, J. Production of lentiviral vectors in protein-free media. Curr Protoc Cell Biol , Chapter 26:Unit 26.8 (2011).

Cadinanos, J. & Bradley, A. Generation of an inducible and optimized piggyBac transposon system. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (12), e87 (2007).

Micheel, B. et al . The production and radioimmunoassay application of monoclonal antibodies to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). J. Immunol. Methods 111 (1), 89–94 (1988).

Holzlöhner, P. & Hanack, K. Generation of murine monoclonal antibodies by hybridoma technology. J Vis Exp 119 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research for funding the work (03IP703). We thank Prof. Burkhard Micheel for proof-reading and critical comments. MG was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Grant FKZ 13GW0098) and by the Helmholtz Association through programme oriented funding (POF). We acknowledge the support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Open Access Publishing Fund of University of Potsdam.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Immunotechnology Group, Institute of Biochemistry and Biology, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

Martin Listek, Anja Hönow & Katja Hanack

Berlin-Brandenburg Center for Regenerative Therapies (BCRT), Berlin, Germany

Manfred Gossen

Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Institute of Biomaterial Science, Teltow, Germany

new/era/mabs GmbH, August-Bebel-Str. 89, Potsdam, Germany

Katja Hanack

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.L. designed the vector and performed the transfection of myeloma cells as well as the experimental studies to characterize cell surface expression. A.H. developed the protocol for the staining and selection of hybridoma cells and validated the system for routine use. M.G. provided the piggyBac transposon system and supported the genetic engineering of cells. K.H. wrote the paper, analyzed the data and coordinated the development and validation of the technology.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katja Hanack .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

K.H. has a management role and is shareholder of new/era/mabs GmbH. The technology is patent filed under EP 14727392.4 by the company. The work of M.L., A.H. and K.H. was funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (Grant No. 03IPT703X). K.H. and M.L. are inventors of the described technology. M.G. declares no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Listek, M., Hönow, A., Gossen, M. et al. A novel selection strategy for antibody producing hybridoma cells based on a new transgenic fusion cell line. Sci Rep 10 , 1664 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58571-w

Download citation

Received : 09 August 2019

Accepted : 14 January 2020

Published : 03 February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58571-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Integrative overview of antibodies against sars-cov-2 and their possible applications in covid-19 prophylaxis and treatment.

- Norma A. Valdez-Cruz

- Enrique García-Hernández

- Mauricio A. Trujillo-Roldán

Microbial Cell Factories (2021)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

Hybridoma Technology for the Generation of Monoclonal Antibodies

Series: Methods In Molecular Biology > Book: Antibody Methods and Protocols

Protocol | DOI: 10.1007/978-1-61779-931-0_7

- NIBR Biologics Center, Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Cambridge, MA, Switzerland

Hybridoma technology has long been a remarkable and indispensable platform for generating high-quality monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Hybridoma-derived mAbs have not only served as powerful tool reagents but also have emerged as the most rapidly

Hybridoma technology has long been a remarkable and indispensable platform for generating high-quality monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Hybridoma-derived mAbs have not only served as powerful tool reagents but also have emerged as the most rapidly expanding class of therapeutic biologics. With the establishment of mAb humanization and with the development of transgenic-humanized mice, hybridoma technology has opened new avenues for effectively generating humanized or fully human mAbs as therapeutics. In this chapter, an overview of hybridoma technology and the laboratory procedures used routinely for hybridoma generation are discussed and detailed in the following sections: cell fusion for hybridoma generation, antibody screening and characterization, hybridoma subcloning and mAb isotyping, as well as production of mAbs from hybridoma cells.

Figures ( 0 ) & Videos ( 0 )

Experimental specifications, other keywords.

Citations (50)

Related articles, production of monoclonal antibody, hybridoma technology, production and screening of monoclonal peptide antibodies, production of human antibodies from transgenic mice, monoclonal antibodies, generation of monoclonal antibodies against chemokine receptors, 8 the recovery of immunoglobulin sequences from single human b cells by clonal expansion, immunohistochemical, flow cytometric, and elisa-based analyses of intracellular, membrane-expressed, and extracellular hsp70 as cancer biomarkers, experimental mouse models of ragweed- and papain-induced allergic conjunctivitis, s100a8/a9 in myocardial infarction.

- Köhler G, Milstein C (1975) Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 256:495–497

- Little M, Kipriyanov SM, Gall FL, Moldenhauer G (2000) Of mice and men: hybridoma and recombinant antibodies. Immunol Today 21: 364–370

- An Z (2010) Monoclonal antibodies—a proven and rapidly expanding therapeutic modality for human diseases. Protein Cell 1:319–330

- Weiner LM (2007) Building better magic bullets—improving unconjugated monoclonal antibody therapy for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 7: 701–706

- Schlossman SF et al (1995) Leucocyte typing V: white cell differentiation antigens. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Matesanz-Isabel J, Sintes J, Llinàs L et al (2011) New B-cell CD molecules. Immunol Lett 134:104–112

- Kung P, Goldstein G, Reinherz EL, Schlossman SF (1979) Monoclonal antibodies defining distinctive human T cell surface antigens. Science 206:347–349

- Reinherz EL, Kung PC, Goldstein G, Schlossman SF (1979) Separation of functional subsets of human T cells by a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:4061–4065

- Meuer SC, Hussey RE, Hodgdon JC et al (1982) Surface structures involved in target recognition by human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Science 218:471–473

- Zhang C, Ao Z, Seth A, Schlossman SF (1996) A mitochondrial membrane protein defined by a novel monoclonal antibody is preferentially detected in apoptotic cells. J Immunol 157: 3980–3987

- Zhang C (1998) Monoclonal antibody as a probe for characterization and separation of apoptotic cells. In: Zhu L, Chun J (eds) Apoptosis detection and assay methods. BioTechniques series on molecular laboratory methods. BioTechniques Books, Eaton Publishing, Natick, MA, pp 63–73

- Bok RA, Small EJ (2002) Bloodborne biomolecular markers in prostate cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2:918–926

- Wagner PD, Maruvada P, Srivastava S (2004) Molecular diagnostics: a new frontier in cancer prevention. Exp Rev Mol Diagn 4:503–511

- Jones PT, Dear PH, Foote J, Neuberger MS, Winter G (1986) Replacing the complementarity-determining regions in a human antibody with those from a mouse. Nature 321:522–525

- Riechmann L, Clark M, Waldmann H, Winter G (1988) Reshaping human antibodies for therapy. Nature 332:323–327

- Smith SL (1996) Ten years of Orthoclone OKT3 (muromonab-CD3): a review. J Transpl Coord 6:109–119

- Lupo L, Panzera P, Tandoi F et al (2008) Basiliximab versus steroids in double therapy immunosuppression in liver transplantation a prospective randomized clinical trial. Transplantation 86:925–931

- Van den Brande JM, Braat H, van den Brink GR et al (2003) Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 124:1774–1785

- Chan AC, Carter PJ (2010) Therapeutic antibodies for autoimmunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 10:301–316

- Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, White CA et al (1997) IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 90:2188–2195

- Meissner HC, Welliver RC, Chartrand SA et al (1999) Immunoprophylaxis with palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection in high risk infants: a consensus opinion. Pediatr Infect Dis J 18:223–231

- Blattman JN, Greenberg PD (2004) Cancer immunotherapy: a treatment for the masses. Science 305:200–205

- Reichert JM (2011) Antibody-based therapeutics to watch in 2011. mAbs 3:76–99

- McCafferty J, Griffiths AD, Winter G, Chiswell DJ (1990) Phage antibodies: filamentous phage displaying antibody variable domains. Nature 348:552–554

- Hoogenboom HR (2005) Selecting and screening recombinant antibody libraries. Nat Biotechnol 23:1105–1116

- Traggiai E, Becker S, Subbarao K et al (2004) An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat Med 10:871–875

- Lanzavecchia A, Bernasconi N, Traggiai E et al (2006) Understanding and making use of human memory B cells. Immunol Rev 211: 303–309

- Nossal GJV (1992) The molecular and cellular basis of affinity maturation in the antibody response. Cell 68:1–2

- Jakobovits A, Amado RG, Yang X, Roskos L, Schwab G (2007) From XenoMouse technology to panitumumab, the first fully human antibody product from transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol 25:1134–1143

- Brüggemann M, Neuberger MS (1996) Strategies for expressing human antibody repertoires in transgenic mice. Immunol Today 17: 391–397

- Green LL (1999) Antibody engineering via genetic engineering of the mouse: XenoMouse strains are a vehicle for the facile generation of therapeutic human monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol Methods 231:11–23

- Lonberg N (2005) Human antibodies from transgenic animals. Nat Biotechnol 23: 1117–1125

- Davis CG, Gallo ML, Corvalan JRF (1999) Transgenic mice as a source of fully human antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 18:421–425

- Zhang C, Xu Y, Gu J, Schlossman SF (1998) A cell surface receptor defined by a mAb mediates a unique type of cell death similar to oncosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:6290–6295

- Yonehara S, Ishii A, Yonehara M (1989) A cell-killing monoclonal antibody (anti-Fas) to a cell surface antigen co-downregulated with the receptor of tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med 169:1747–1756

- Trauth BC, Klas C, Peters AMJ et al (1989) Monoclonal antibody-mediated tumor regression by induction of apoptosis. Science 245:301–305

- Kearney JF, Radbruch A, Liesegang B, Rajewsky K (1979) A new mouse myeloma cell line that has lost immunoglobulin expression but permits the construction of antibody-secreting hybrid cell lines. J Immunol 123:1548–1550

- Shi S-R, Shi Y, Taylor CR (2011) Antigen retrieval immunohistochemistry: review and future prospects in research and diagnosis over two decades. J Histochem Cytochem 59:13–32

- D’Amico F, Skarmoutsou E, Stivala F (2009) State of the art in antigen retrieval for immunohistochemistry. J Immunol Methods 341:1–18

- Glassy M (1988) Creating hybridomas by electrofusion. Nature 333:579–580

- Ohnishi K, Chiba J, Goto Y, Tokunaga T (1987) Improvement in the basic technology of electrofusion for generation of antibody-producing hybridomas. J Immunol Methods 100:181–189

- Long WL, McGuire W, Palombo A, Emini EA (1986) Enhancing the establishment efficiency of hybridoma cells: use of irradiated human diploid fibroblast feeder layers. J Immunol Methods 86:89–93

Advertisement

Hybridoma technology; advancements, clinical significance, and future aspects

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Engineering & Technology, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies, Faridabad, Haryana, 121004, India.

- 2 Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Engineering & Technology, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies, Faridabad, Haryana, 121004, India. [email protected].

- PMID: 34661773

- PMCID: PMC8521504

- DOI: 10.1186/s43141-021-00264-6

Background: Hybridoma technology is one of the most common methods used to produce monoclonal antibodies. In this process, antibody-producing B lymphocytes are isolated from mice after immunizing the mice with specific antigen and are fused with immortal myeloma cell lines to form hybrid cells, called hybridoma cell lines. These hybridoma cells are cultured in a lab to produce monoclonal antibodies, against a specific antigen. This can be achieved by an in vivo or an in vitro method. It is preferred above all the available methods to produce monoclonal antibodies because antibodies thus produced are of high purity and are highly sensitive and specific. Monoclonal antibodies are useful in diagnostic, imaging, and therapeutic purposes and have a very high clinical significance. Once hybridoma cells become stable, these cell lines offer limitless production of homogenized antibodies. This method is also cost-effective. The antibodies produced by this method are highly sensitive and specific to the targeted antigen. It is an important tool used in various fields of research such as in toxicology, animal biotechnology, medicine, pharmacology, cell, and molecular biology. Monoclonal antibodies are used extensively in the diagnosis and therapeutic applications. Radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies are used as probes to detect tumor antigens in the living system; also radioisotope coupled antibodies are used for therapeutic target specific action on oncogenic cells.

Short conclusion: Presently, the monoclonal antibodies used are either raised in mice or rats; this poses a risk of disease transfer from mice to humans. There is no guarantee that antibodies thus created are entirely virus-free, despite the purification process. Also, there are some immunogenic responses observed against the antibodies of mice origin. Technologically advanced techniques such as genetic engineering helped in reducing some of these limitations. Advanced methods are under development to make lab-produced monoclonal antibodies as human as possible. This review discusses the advantages and challenges associated with monoclonal antibody production, also enlightens the advancement, clinical significance, and future aspects of this technique.

Keywords: Chimeric; Cryopreservation; Hybridomas; Monoclonal antibodies; Therapeutic.

© 2021. The Author(s).

Publication types

Monoclonal Antibodies Generation: Updates and Protocols on Hybridoma Technology

- First Online: 06 January 2022

Cite this protocol

- Ahmed Muhsin 3 , 4 na1 ,

- Roberto Rangel 5 na1 ,

- Long Vien 3 na1 &

- Laura Bover 3 , 6 na1

Part of the book series: Methods in Molecular Biology ((MIMB,volume 2435))

1753 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Since its inception in 1975, the hybridoma technology revolutionized science and medicine, facilitating discoveries in almost any field from the laboratory to the clinic. Many technological advancements have been developed since then, to create these “magical bullets.” Phage and yeast display libraries expressing the variable heavy and light domains of antibodies, single B-cell cloning from immunized animals of different species including humans or in silico approaches, all have rendered a myriad of newly developed antibodies or improved design of existing ones. However, still the majority of these antibodies or their recombinant versions are from hybridoma origin, a preferred methodology that trespass species barriers, due to the preservation of the natural functions of immune cells in producing the humoral response: antigen specific immunoglobulins. Remarkably, this methodology can be reproduced in small laboratories without the need of sophisticate equipment. In this chapter, we will describe the most recent methods utilized by our Monoclonal Antibodies Core Facility at the University of Texas–M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. During the last 10 years, the methods, techniques, and expertise implemented in our core had generated more than 350 antibodies for various applications.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Kohler G, Milstein C (1975) Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 256(5517):495–497. https://doi.org/10.1038/256495a0

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Couzin-Frankel J (2013) Cancer immunotherapy. Science 342(6165):1432–1433. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.342.6165.1432

Zhang J, Medeiros LJ, Young KH (2018) Cancer immunotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front Oncol 8:351. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00351

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Giordano SH, Temin S, Chandarlapaty S, Crews JR, Esteva FJ, Kirshner JJ, Krop IE, Levinson J, Lin NU, Modi S, Patt DA, Perlmutter J, Ramakrishna N, Winer EP, Davidson NE (2018) Systemic therapy for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 36(26):2736–2740. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.79.2697

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Modest DP, Denecke T, Pratschke J, Ricard I, Lang H, Bemelmans M, Becker T, Rentsch M, Seehofer D, Bruns CJ, Gebauer B, Modest HI, Held S, Folprecht G, Heinemann V, Neumann UP (2018) Surgical treatment options following chemotherapy plus cetuximab or bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer-central evaluation of FIRE-3. Eur J Cancer 88:77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.10.028

Urits I, Clark G, An D, Wesp B, Zhou R, Amgalan A, Berger AA, Kassem H, Ngo AL, Kaye AD, Kaye RJ, Cornett EM, Viswanath O (2020) An evidence-based review of Fremanezumab for the treatment of migraine. Pain Ther 9(1):195–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00159-3

Menegatti S, Bianchi E, Rogge L (2019) Anti-TNF therapy in Spondyloarthritis and related diseases, impact on the immune system and prediction of treatment responses. Front Immunol 10:382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00382

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Saphire EO, Schendel SL, Fusco ML, Gangavarapu K, Gunn BM, Wec AZ, Halfmann PJ, Brannan JM, Herbert AS, Qiu X, Wagh K, He S, Giorgi EE, Theiler J, Pommert K, Krause TB, Turner HL, Murin CD, Pallesen J, Davidson E et al (2018) Systematic analysis of monoclonal antibodies against Ebola virus GP defines features that contribute to protection. Cell 174(4):938–952.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.033

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19 (Accessed 9 2020)

US Food and Drug Administration Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibodies-treatment-covid-19 (Accessed 21 2020)

Marhelava K, Pilch Z, Bajor M, Graczyk-Jarzynka A, Zagozdzon R (2019) Targeting negative and positive immune checkpoints with monoclonal antibodies in therapy of cancer. Cancers 11(11):1756. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111756

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sharma P, Allison JP (2015) Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell 161(2):205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.030

Rose S (2017) First-ever CAR T cell therapy approved in U.S. news in brief. Cancer Discov 7(10):OF1. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2017-126

Article Google Scholar

Boyiadzis MM, Dhodapkar MV, Brentjens RJ, Kochenderfer JN, Neelapu SS, Maus MV, Porter DL, Maloney DG, Grupp SA, Mackall CL, June CH, Bishop MR (2018) Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T therapies for the treatment of hematologic malignancies: clinical perspective and significance. J Immunother Cancer 6(1):137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-018-0460-5

Poh A (2017) Equipping NK cells with CARs. News in brief. Cancer Discov 7(10):OF2. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2017-124

Mehta RS, Rezvani K (2018) Chimeric antigen receptor expressing natural killer cells for the immunotherapy of cancer. Front Immunol 9:283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00283

Guo B, Fu S, Zhang J, Liu B, Li Z (2016) Targeting inflammasome/IL-1 pathways for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Rep 6:36107. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36107

Dagenais M, Dupaul-Chicoine J, Douglas T, Champagne C, Morizot A, Saleh M (2017) The interleukin (IL)-1R1 pathway is a critical negative regulator of PyMT-mediated mammary tumorigenesis and pulmonary metastasis. Onco Targets Ther 6(3):e1287247. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2017.1287247

Ritter B, Greten FR (2019) Modulating inflammation for cancer therapy. J Exp Med 216(6):1234–1243. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20181739

Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Thuren T, Everett BM, Libby P, Glynn RJ, CANTOS Trial Group (2017) Effect of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 390(10105):1833–1842. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32247-X

Arumugam T, Deng D, Bover L, Wang H, Logsdon CD, Ramachandran V (2015) New blocking antibodies against novel AGR2-C4.4A pathway reduce growth and metastasis of pancreatic tumors and increase survival in mice. Mol Cancer Ther 14(4):941–951. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0470

Sergeeva A, Alatrash G, He H, Ruisaard K, Lu S, Wygant J, McIntyre BW, Ma Q, Li D, St John L, Clise-Dwyer K, Molldrem JJ (2011) An anti-PR1/HLA-A2 T-cell receptor-like antibody mediates complement-dependent cytotoxicity against acute myeloid leukemia progenitor cells. Blood 117(16):4262–4272. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-07-299248

Meller S, Di Domizio J, Voo KS, Friedrich HC, Chamilos G, Ganguly D, Conrad C, Gregorio J, Le Roy D, Roger T, Ladbury JE, Homey B, Watowich S, Modlin RL, Kontoyiannis DP, Liu YJ, Arold ST, Gilliet M (2015) T(H)17 cells promote microbial killing and innate immune sensing of DNA via interleukin 26. Nat Immunol 16(9):970–979. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3211

Fuery A, Leen AM, Peng R, Wong MC, Liu H, Ling PD (2018) Asian elephant T cell responses to elephant Endotheliotropic herpesvirus. J Virol 92(6):e01951–e01917. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01951-17

Voo KS, Bover L, Harline ML, Vien LT, Facchinetti V, Arima K, Kwak LW, Liu YJ (2013) Antibodies targeting human OX40 expand effector T cells and block inducible and natural regulatory T cell function. J Immunol 191(7):3641–3650. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1202752

Hu J, Vien LT, Xia X, Bover L, Li S (2014) Generation of a monoclonal antibody against the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked protein Rae-1 using genetically engineered tumor cells. Biol Proced Online 16(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1480-9222-16-3

Cao W, Bover L, Cho M, Wen X, Hanabuchi S, Bao M, Rosen DB, Wang YH, Shaw JL, Du Q, Li C, Arai N, Yao Z, Lanier LL, Liu YJ (2009) Regulation of TLR7/9 responses in plasmacytoid dendritic cells by BST2 and ILT7 receptor interaction. J Exp Med 206(7):1603–1614. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20090547

Swaminathan A, Lucas RM, Dear K, McMichael AJ (2014) Keyhole limpet haemocyanin - a model antigen for human immunotoxicological studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 78(5):1135–1142. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12422

Zhou H, Wang Y, Wang W, Jia J, Li Y, Wang Q, Wu Y, Tang J (2009) Generation of monoclonal antibodies against highly conserved antigens. PLoS One 4(6):e6087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006087

Yeung TL, Leung CS, Yip KP, Sheng J, Vien L, Bover LC, Birrer MJ, Wong S, Mok SC (2019) Anticancer immunotherapy by MFAP5 blockade inhibits fibrosis and enhances chemosensitivity in ovarian and pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 25(21):6417–6428. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0187

FortéBio. High throughput Octet HTX and Octet RED384 systems 2020 [March 5, 2020]. https://www.fortebio.com/sites/default/files/en/assets/app-overview/characterizing-membrane-protein-interactions-by-bio-layer-interferometry.pdf

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Janis Johnson, Julio Pollarolo, and Zhuang Wu, members of the MAF laboratory. The Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) P30 CA016672 for partially supporting UT-MDACC Shared resources. All the current and past users of our facility for selecting our laboratory to close collaborate in their projects. Finally, the Department of Immunology, chaired by Dr. James P. Allison, home of MAF.

Conflict of Interest : The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Ahmed Muhsin and Roberto Rangel contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Immunology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), Houston, TX, USA

Ahmed Muhsin, Long Vien & Laura Bover

Center for Translational Cancer Research, Institute of Biosciences and Technology, Texas A&M University, Houston, TX, USA

Ahmed Muhsin

Department of Head and Neck Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), Houston, TX, USA

Roberto Rangel

Department of Genomic Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), Houston, TX, USA

Laura Bover

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Laura Bover .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Florencia McAllister

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this protocol

Muhsin, A., Rangel, R., Vien, L., Bover, L. (2022). Monoclonal Antibodies Generation: Updates and Protocols on Hybridoma Technology. In: McAllister, F. (eds) Cancer Immunoprevention. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 2435. Humana, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2014-4_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2014-4_6

Published : 06 January 2022

Publisher Name : Humana, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-0716-2013-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-0716-2014-4

eBook Packages : Springer Protocols

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Hybridoma technology has brought a revolution in cell biology, immunology, biotechnology, toxicology, pharmaceutical research, and medical research. Prior to the introduction of hybridoma technology, antibodies were created by immunizing laboratory animals followed by isolation of the sera, which may then be put to therapeutic use.

Hybridoma technology is one of the most common methods used to produce monoclonal antibodies. In this process, antibody-producing B lymphocytes are isolated from mice after immunizing the mice with specific antigen and are fused with immortal myeloma cell lines to form hybrid cells, called hybridoma cell lines. These hybridoma cells are cultured in a lab to produce monoclonal antibodies ...

The recent advent of antibody engineering technology has superseded the species level barriers and has shown success in isolation of hybridoma across phylogenetically distinct species. This has led to the isolation of monoclonal antibodies against human targets that are conserved and non-immunogenic in the rodent.

Additionally, although hybridoma technology enables the generation of large quantities of mAbs, it is a time-consuming process (6-9 months) that demands substantial resources and time [205]. In ...

Since the introduction of the hybridoma technology, mAbs have had a profound impact on medicine, providing an almost limitless source of therapeutic, diagnostic, and research reagents (Nissim and Chernajovsky, 2008; Ribatti, 2014).Given the universality and usefulness of mAbs, many discoveries came as a result of hybridoma technology, allowing the generation of antibodies directed against an ...

Hybridoma technology used to produce mAbs: ... Academic and industrial research groups with expertise in the field of antibody isolation, hybridoma methodology continues being the methodology of the first choice, particularly if the goal is to obtain antibodies for analytical purposes. ... RK wrote the paper and finalized with the help of HAP ...

The field of monoclonal antibody generation via hybridoma technology is still ... MG was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Grant FKZ 13GW0098) and by the ...

Hybridoma technology has long been a remarkable and indispensable platform for generating high-quality monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). ... Antigen retrieval immunohistochemistry: review and future prospects in research and diagnosis over two decades. J Histochem Cytochem 59:13-32 D'Amico F, Skarmoutsou E, Stivala F (2009) State of the art in ...

Abstract. Background: Hybridoma technology is one of the most common methods used to produce monoclonal antibodies. In this process, antibody-producing B lymphocytes are isolated from mice after immunizing the mice with specific antigen and are fused with immortal myeloma cell lines to form hybrid cells, called hybridoma cell lines.

Hybridoma technology has brought a revolution in cell biology, immunology, biotechnology, toxicology, pharmaceutical research, and medical research. Prior to the introduction of hybridoma technology, antibodies were created by immunizing laboratory animals followed by isolation of the sera, which may then be put to therapeutic use.

"The hybridoma technology was a by-product of basic research. Its success in practical applications is the result of unexpected and unpredictable properties of the method. It represents another example of the enormous practical impact of an investment in research which might not have been considered commercially worthwhile, or of immediate medical relevance.