Food Deserts: Causes, Consequences and Solutions

Activities will help students:

- define and examine the characteristics of food deserts

- identify the causes and consequences of food deserts

- determine if their community is a food desert

- research the closest food desert to their school

- design solutions to help residents who live in food deserts

- How does our neighborhood influence the choices we make about our health?

- How would not having a grocery store near your home affect you?

- What are the causes of obesity?

- What does it mean to have a healthy diet?

- What criteria might supermarket chains use to decide where to build stores?

- Access to the Internet

- Food Desert Statistics

- What’s in Store?

- Flip chart paper

- Four signs, with one of the following phrases written on each: Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree and Strongly Disagree

Studies show that certain racial groups are disproportionately affected by obesity. These problems may be worse in some U.S. communities because access to affordable and nutritious food is difficult. This is especially true for those living in low-income communities of color and rural areas with limited access to supermarkets, grocery stores or other food retailers that offer the large variety of foods needed for a healthy diet such as fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fresh dairy and lean meat products. Instead, individuals in these areas may be more reliant on convenience stores, fast food or similar retailers, or they may not have enough money to afford the higher prices. These areas of limited access are called “food deserts.”

This lesson explores the concept of food deserts and the relationship between food deserts, poverty and obesity. Students are encouraged to examine their personal access to a healthy diet; compare prices of common staple items among different retail options; and analyze the causes and consequences of food deserts locally and nationally. Finally, students are asked to come up with solutions to help the food desert that is closest to their school.

Additional Resources

- United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Site includes a Food Desert Locator (Maps and provides data about food deserts in United States) and a Food Environment Atlas (Provides an overview about a community’s ability to access healthy food).

- Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and their Consequences : Report (2009) to Congress from the United States Department of Agriculture.

- The Grocery Gap: Who Has Access to Healthy Food and Why It Matters : Report from Policy Link and the Food Trust.

disparity [dih- spare -i-tee] (noun) lack of equality, inequality, difference

food desert [food dez -ert] (noun) a neighborhood where there is little or limited access to healthy and affordable food such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat milk and other foods that make up the full range of a healthy diet

food insecurity [food in-si- ky oo r -i-tee] (noun) lack of access to a sufficient amount of food because of limited funds. More than 49 million American households are considered food insecure and are vulnerable to poor health as a result.

obesity [oh- bee -si-tee] (noun) the condition of being very overweight

- It’s easy to eat healthy food.

- Limited access to a supermarket can be linked to obesity.

- Supermarket chains should be forced to build in urban and rural areas, not just suburban areas.

- Walk to the sign that represents your feelings or beliefs about this statement. Talk with the other students who chose to stand by the same sign and discuss your position. One group at a time, share your group’s position with the class. If you agree more with another group after hearing their position, feel free to switch corners. If you switch corners, be ready to defend your choice. (Note: When the groups have finished reporting their positions, repeat the activity with the following two statements.)

- Why might healthy, affordable food be difficult to obtain in certain areas?

- In which types of areas/communities do you think food deserts are most prevalent: urban, rural or suburban?

- How do you think living in a food desert could affect a person/family’s food choices?

- Other than grocery stores/supermarkets, where else could you purchase food?

- How might food options in convenience stores or fast food establishments be less healthy and/or more expensive?

- How could living in a food desert relate to food insecurity (hunger)? Conversely, how could it relate to obesity?

- Review answers to the questions as a class. What conclusions can you draw about the relationship between food deserts and obesity? If there is a direct relationship, which groups might be most often affected? Write down one or two ideas you think could help those who live in food deserts. Save them for later in the lesson.

- What’s in Store? asks you to fill out information about three different types of places you could purchase food in your community and to research costs at these retailers for select staple items. With your original partner, pair up with another set of students and complete the handout. Then compare answers with the rest of the class. What surprised you about your community, food costs or other information you researched?

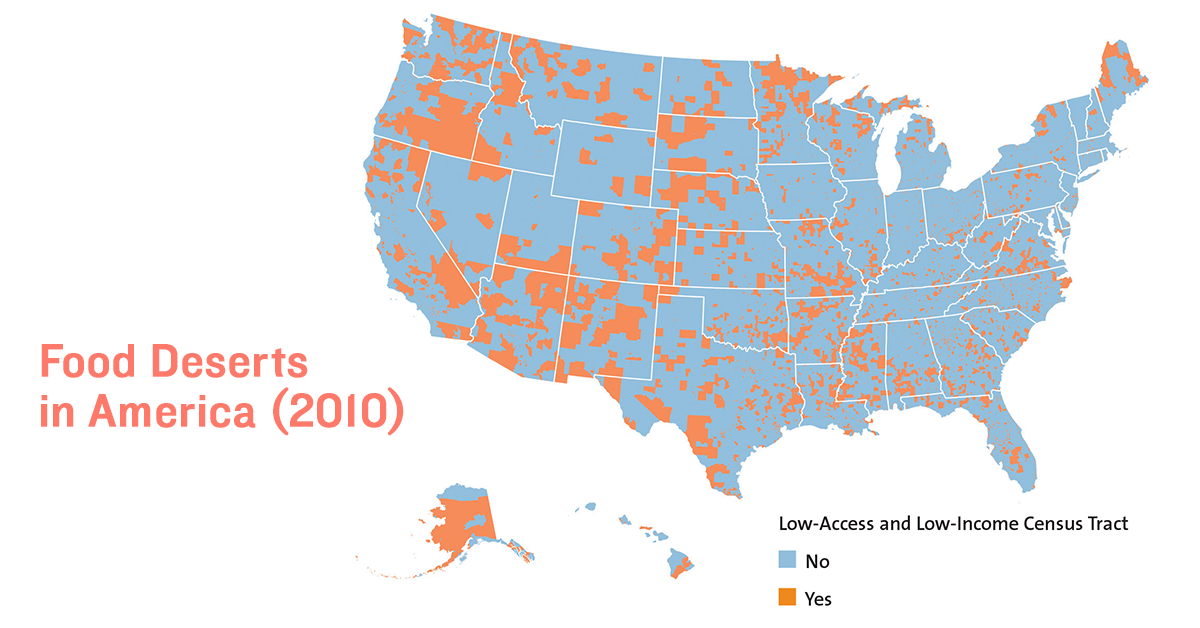

- Where do you think the closest food desert to your school/community is? Write your prediction. Then go online to the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Desert Locator . When you enter the locator, you will see a map of the United States with food deserts highlighted in red. A food desert is defined on the site as a “low income census tract where a substantial number or share of residents has low access to a supermarket or large grocery store (at least 33% of the population resides more than one mile from a grocery store or more than 10 miles for a rural census tract). Share an observation with a partner about the patterns on the national map. Are they concentrated in a particular part of the country? In urban areas? Rural areas? Do any patterns emerge? Compare observations with another group of four.

- Enter your school’s address into the locator and see if you were correct about the food desert closest to your school. Click on the area highlighted in red to see information about the Food Desert, including the number and percentage of people with low access; the poverty level and the number and percentage of people without a vehicle. What story does the statistics tell?

- Divide into two groups, one to brainstorm about the causes of food deserts and the other to brainstorm about the consequences. You can find additional information in the sites/reports listed above. The causes group should think about why supermarkets, convenience stores, and fast food restaurants might build or develop in a certain area; how geography and distance play a role; why a business may not want to build in a certain neighborhood; economics; and demographics. The consequences group should think about personal, economic, national, health-related and social consequences. Each group should present to the other, with the opposite group adding any new information.

- Pair up with two or three other students from your group to form a smaller group. Imagine that you and your group have been assigned one of the tasks below to assist those who live in the closest food desert to your school. Or refer back to the ideas you generated earlier in the lesson to see if you’d rather use one of those. In order to complete your task, you will need to research information about the neighborhood or community. Try to learn economic and racial statistics, along with other distinguishing factors of the community. Task 1: You have been asked to present information to a large grocery chain that would persuade them to build a supermarket closer to the food desert you have selected. Information could be about the community itself, including the number of children; general health/wellness statistics; the benefits to the supermarket of building here; and common good that a supermarket can bring to a community. Task 2: You have been asked to come up with an idea, other than a standard grocery store/supermarket, that could give those in the food desert you’ve selected access to healthy and affordable food. Write a white paper describing your idea, what would have to happen to make the idea a reality, any related costs and why you think it would work in this community. Task 3: You have been asked to design an education campaign to help those who live in the food desert understand the importance of eating healthy foods and tips for accessing healthy foods and selecting affordable healthy foods when on a budget.

- Present your project—justifying how you think it could help the food desert you have identified—to the class.

- Finally, go back to the statements you heard at the beginning of the lesson and determine if you feel the same or if your opinion has changed. Justify your answer using what you’ve learned in the lesson.

Extension Activity

As a class, select one (or more) of the project ideas relating to food deserts that you could truly implement. Design a plan that could turn the idea into a reality, identify the stakeholders and implement the plan.

Activities address the following standards using the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts : CCSS: SL.1, SL.4, SL.6, SL.7, W.1; Common Core State Standards for Mathematics

- Google Classroom

Sign in to save these resources.

Login or create an account to save resources to your bookmark collection.

New Virtual Workshops Are Available Now!

Registrations are now open for our 90-minute virtual open enrollment workshops. Explore the schedule, and register today—space is limited!

Get the Learning for Justice Newsletter

For Businesses

For students & teachers, food desert lesson: what are they and how do we teach our students about them.

Joseph Ciampa

For some of us, it can be difficult to think of daily life without access to the food we consume everyday: the scrambled eggs you ate this morning, that well-intentioned salad you packed for lunch, or your favorite chicken and rice recipe you whipped up for dinner. All picked up from your local grocery store earlier in the week.

Not everyone is as fortunate to have a grocery store in their neighborhood, or even their town. A 2009 study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that 23.5 million people lack access to a grocery store within a mile of their home. Reliable food sources, such as grocery stores, often go unappreciated in communities where they’re easily accessible.

Is Your Grocer Taken for Granted?

Grocery stores carry fresh foods packed with flavor, and more importantly, nutrition , all at a reasonable price. Fruits, vegetables, lean meat, dairy, and whole grains, all essential for sustaining a healthy life, are exclusively available at grocery stores.

What happens when the closest grocery store is over an hour away? Or in the next state over? What happens if you don’t have a car?

Areas like this are known as food deserts : underserved communities where access to fresh food products is limited. Low-income communities, communities of color, and sparsely populated rural areas are disproportionately affected.

Residents of these communities rely on fast food restaurants and convenience stores for meals, which tend to lack the quality, nutrient-rich ingredients necessary for a balanced diet. In fact, low-income zip codes have 30 percent more convenience stores than middle-income zip codes. While some convenience stores do carry fresh produce, they often have fewer options and tend to cost more than grocery stores, putting those who live in food deserts at a financial and nutritional disadvantage.

The Consequences of Food Deserts

The financial and nutritional disadvantages endured by those who live in food deserts eventually take a toll on overall well-being and wedge these communities further into a cycle of poverty.

Lack of access to nutritional foods means people in low-income communities suffer from diet-related illnesses, like diabetes or obesity, more than higher-income neighborhoods. The disparity is illustrated clearly when you look state by state, or city by city. In Mississippi, the state with the highest rate of obesity, 70 percent of food stamp eligible households have to travel over 30 miles to get to their closest grocery store. In Albany, NY, 80 percent of non-white residents can’t find low-fat milk or high-fiber bread in their neighborhoods.

The lack of healthy options available to these communities also causes economic disparities. Private institutions are more likely to invest in communities where there are food retail space options, creating new jobs and revitalizing neighborhoods. Pennsylvania created a statewide public-private initiative to bring new grocery stores to underserved communities. The effort created nearly 5,000 new jobs in 78 communities, bolstering the economic activity in surrounding areas around the state.

What is Food Justice?

Food justice, in the simplest of terms, is equality. It’s about ensuring everyone, regardless of wealth, race, or location, has access to the same foods.

There are three main aspects of food justice:

- Access to nutritious and fresh foods

- Living wage jobs for all food system workers

- Cooperative community organizations

Classroom Discussion

Start a conversation by asking your students three questions:

- Where does your family shop for groceries?

- How long does it take to drive there?

- How far away is the closest convenience store?

Answers from students will vary, but this is a good segway into talking about food deserts. Make sure to differentiate convenience from grocery stores, talking about the different foods primarily available in each.

Explain the importance of maintaining a balanced diet and demonstrate the connection between healthy eating and food access. People don’t always choose to eat unhealthily; sometimes it’s their only option. It’s important to voice the positive effects that better food access has on our bodies and communities.

Classroom Activity

Have students survey family, friends, and community members about needs in their neighborhoods for homework. Have them ask where they shop for groceries, how often they go, and what they typically purchase.

Students can then develop a concept for their own grocery store. Have them write down the healthy items they hope to carry in their grocery stores. They can then develop a plan to promote healthy eating and their new grocery store to the community.

Take it one step further by creating a mock grocery store in your classroom. Bring in various fruits, vegetables, and packaged foods with price tags. Show students the differences between purchasing these items in a grocery store vs. a convenience store. This will show students the importance of equal food access, while also teaching them about maintaining a balanced diet.

Joseph Ciampa is Creative Marketing Associate on EVERFI’s K-12 Marketing Team.

Want to prepare students for career and life success, but short on time?

Busy teachers use EVERFI’s standards-aligned, ready-made digital lessons to teach students to thrive in an ever-changing world.

Explore More Resources

Beyond the glass ceiling - the rise of nfl trailblazers jennifer king and maia chaka.

Learn about two women who persevered against all odds to break barriers as the first females in their NFL coaching and officiating ro ...

How Intuit for Education and EVERFI are Working to Improve Financial Confidence this Tax Se...

Learn more about this real-world tool that provides high school students with the skills and knowledge they need to file taxes.

Resource Database

Exemplar lesson plans, news for students, professional development, guidance for school boards, climatesocrates™ help center.

- Favorites Save Resource

Database Provider

Resource types.

- Lesson Plans

- Articles and Websites

Regional Focus

How to analyze sustainability problems: food deserts.

- In this lesson, students practice analyzing a sustainability problem with the concept of food deserts.

- After reading an article about food deserts, groups of students discuss the article and build a fishbone diagram to highlight the central problem and contributing factors. Then, groups consider possible food desert solutions and incorporate them into their diagrams.

- Students will need to use this article and these solution cards for the lesson.

- This lesson is relevant and the topic of food deserts will likely engage young learners.

- This lesson puts students in the position of problem solvers and administrators of a solution.

Additional Prerequisites

- Students should already have a working knowledge of environmental, social, and economic sustainability.

- The link to Chain Reaction Magazine does not work, but you can still access the article, Cultivating the Food Desert .

Differentiation

- This activity could be extended by debating the possible solutions and building cost-benefit analyses or arguments for which is the most viable.

- The resource includes five additional extension activities for students to repeat the solution analysis process using different sustainability topics.

- For learners that need additional support in a group discussion or analyzing the food desert solutions, the teacher could provide the following prompting questions:

- What parts of the problem will this solution do the best job of fixing?

- Are there any parts of the problem that will remain even after the solution has been implemented?

This resource addresses the listed standards. To fully meet standards, search for more related resources.

- MS-ESS3-4. Construct an argument supported by evidence for how increases in human population and per-capita consumption of natural resources impact Earth’s systems.

SubjectToClimate™

- More Resources

Exploring Food Deserts in the United States

- Kathryn Reynolds

How to Cite

Download citation.

Download this resource to see full details. Download this resource to see full details.

Usage Notes

Learning goals and assessments.

Learning Goal(s):

- Students will be able to define the concept of food deserts and identify where they exist in the U.S.

- Students will learn the criteria used by the USDA to define food deserts.

- Students will apply the USDA definition of food deserts to locate them in areas where they are from and assess the contexts of these food deserts.

Goal Assessment(s):

- Students will become familiar with the USDA website and the interactive food desert map. Students will also learn about the criteria used by the USDA, USDT, and DHHS to define a food desert and how these criteria differ between rural and urban areas.

- Students will complete the provided worksheet using the information from their three census tracts and indicate which criteria their census tracts fall into as food deserts.

- Students will identify the severity of their selected food deserts on a scale using proximity to grocery outlet and access to vehicles collectively on a whiteboard or other surface. A recommended scale is provided in the appendix.

When using resources from TRAILS, please include a clear and legible citation.

Similar Resources

- Kathryn Reynolds, Exploring Food Deserts in the United States , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Julie A Pelton, Food, Foodies, and Food Cultures: An Introduction to Sociology , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Jamie Oslawski-Lopez, Analyzing Social Stratification and Inequality in The Hunger Games (2012) Film: Presentation and Reflection Assignment , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Shawn Alan Trivette, Agriculture, Food, and Society , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Sherry N. Mong, Teaching About Criminological Theory and Hate Crime Through Documentary: The Case of Matthew Shepard , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Julia Waity, Samantha Durham, Using Virtual Reality to Learn about Place , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: Teaching High School Sociology

- Elaine Gerber, The Anthropology of Food: We Are How We Eat , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Georgi M. Derluguian, Varieties of the Pre-Modern World Systems: World-Systems Before the Western Expansion , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Sabine N. Merz, THE SOCIOLOGY OF FOOD: A SELECTED VIDEOGRAPHY , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Rachel Sparkman, Rural Sociology Syllabus , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 > >>

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this resource.

All ASA members get a subscription to TRAILS as a benefit of membership.

Use your ASA username and password to log in.

By clicking Login, you agree to abide by the TRAILS user agreement .

Our website uses cookies to improve your browsing experience, to increase the speed and security for the site, to provide analytics about our site and visitors, and for marketing. By proceeding to the site, you are expressing your consent to the use of cookies. To find out more about how we use cookies, see our Privacy Policy .

CUNY Academic Works

- < Previous

Home > LaGuardia Community College > Open Educational Resources > 120

Open Educational Resources

A biological lens on food deserts [biology].

Claudette Davis , CUNY La Guardia Community College Follow

Document Type

Publication date.

SCB101 is a non-major biology course. In Fall 2022, the course was designated as an Experiential Learning-LaGuardia Humanitarian Initiative (LHI) course in CUNYFirst. LHI is LaGuardia's experiential learning program that helps students to critically reflect on global issues and develop sustainable solutions in partnership with local and global organizations. For the 2022-2023 academic year, LHI focused on two United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG): Goal 2 and Goal 10. UNSDG 2 aims to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. UNSDG 10 addresses reducing inequality both within and among countries. Thus, I developed an assignment to help students examine food deserts in an urban area with the overall goal being to understand the impact of food deserts in our communities and how they contribute towards perpetuating food insecurities and injustices. Students were encouraged to independently define food deserts and relate the term to urban areas. By the end of the course, students should be able to define food desert, become familiar with mapping and scaling to show food sources in their community, analyze the data obtained to make a rational conclusion regarding food deserts in an urban community. By the end of the course, students should be able to demonstrate the skills necessary to understand and apply scientific concepts such as obesity, and reasoning like data analysis, graphing.

Furthermore, the assignment allows students to further their learning by using statistical data to identify food deserts and explain how populations that live in food deserts are affected both biologically and economically. The assignment also asks students to map their community by showing the location of food places within a 5 mile radius from their homes. After determining the location of food places within their communities, students are asked to consider whether the foods served in these places are healthy.

In the latter part of the semester, students are introduced to human physiology and complete a basal metabolic rate (BMR) lab activity. At the completion of the lab, each student is aware of the amounts of protein, carbohydrates, and fats they need on a daily bases. Having this information at hand, students can plan their daily diets accordingly. Students can use the information obtained in the lab activity to advocate for healthier food options available to them in their communities. This is particularly important for the student/students who find they do not live in a food desert due to the number of fast-food restaurants, bodegas, and delis located in their community. Students will begin to note whether obtaining food from these sources is best for a healthy diet. Finally, students developed an action plan to address the biological and economic impact of food deserts by writing letters to their local, state, or congressional representatives. Students who did not live in a food desert examined the health statistics in their communities.

LaGuardia’s Core Competencies and Communication Abilities

Learning Objectives:

By the end of the course, students should be able to demonstrate the skills necessary to understand and apply scientific concepts and reasoning, such as making observations, testing hypotheses, data analysis, and evaluation. This experiential learning assignment aligns with the learning objective of inquiring about a problem and identifying strategies to address the problem of food insecurity, as mentioned above. Below is a brief outline of the steps implemented to achieve the goals for the assignment:

First, students gathered community demographic data (population size, median income, race/ethnicity). This will help them become more knowledgable with obtaining and synthesizing data from governmental agencies like the United States Census Bureau and Centers for Disease Control. Furthermore, the assignment will allow students to become familiar with their US, state, and local representatives.

Next, students map the location of food sources in their community. Students used a 2-4-mile radius from their home to determine the number of supermarkets, bodegas, dollar stores, and vegetable markets. Identifying accessible food sources allowed students to gain a better understanding of the definition of food desert.

Finally, students synthesized the information obtained in the previous assignments to determine whether they live in a food desert. Students are given two choices on this assignment. If they live in an urban food desert, they can advocate for more supermarkets and restaurants that can bring healthy food options to their community. Thus, writing letters to their local representatives (obtained in assignment #1), students can use the data obtained to support their claim that an urban food desert needs funding to promote a healthier community.

The assignment was used in SCB101, a non-majors biology course. The course fulfills LaGuardia's general education requirement under the Life and Physical Sciences category.

Students enrolled in SCB101: Topics in Biological Sciences are non-majors.

This was a scaffolded assignment done in a 12-week semester. Students completed the first assignment by the end of week 3. The second assignment was due by the end of week 5. The final assignment was due by the end of week 8.

The assignment is worth 15% of the final grade. The assignment is divided into three parts. Scaffolding the assignment will allow students to synthesize the information gathered, thus giving them a chance to share and ask questions as they complete each part. Furthermore, scaffolding will allow students to retain information and use it to build on what they know. Below is a breakdown of each assignment.

Part I – My community’s demographics, local, state, and congressional representatives (2%) Part II – Mapping my community (5%) Part III – Action plan and Reflection (8%)

This resource is part of the Learning Matters Assignment Library .

Creative Commons License

Included in.

Biology Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

- Colleges, Schools, Centers

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- Submission Policies

- Submit Work

- LaGuardia Community College

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Financial Information

- Our History

- Our Leadership

- The Casey Philanthropies

- Workforce Composition

- Child Welfare

- Community Change

- Economic Opportunity

- Equity and Inclusion

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Juvenile Justice

- Leadership Development

- Research and Policy

- Child Poverty

- Foster Care

- Juvenile Probation

- Kinship Care

- Racial Equity and Inclusion

- Two-Generation Approaches

- See All Other Topics

- Publications

- KIDS COUNT Data Book

- KIDS COUNT Data Center

Food Deserts in the United States

What is a food desert?

Food deserts are geographic areas where residents have few to no convenient options for securing affordable and healthy foods — especially fresh fruits and vegetables. Disproportionately found in high-poverty areas, food deserts create extra, everyday hurdles that can make it harder for kids, families and communities to grow healthy and strong.

Where are food deserts located?

Generally speaking, food deserts are more common in areas with:

- smaller populations;

- higher rates of abandoned or vacant homes; and

- residents who have lower levels of education, lower incomes, and higher rates of unemployment.

Food deserts are also a disproportionate reality for Black communities, according to a 2014 study from Johns Hopkins University . The study compared U.S. census tracts of similar poverty levels and found that, in urban areas, Black communities had the fewest supermarkets, white communities had the most, and multiracial communities fell in the middle of the supermarket count spectrum.

How are food deserts identified?

Researchers consider a variety of factors when identifying food deserts, including:

- Access to food, as measured by distance to a store or by the number of stores in an area.

- Household resources, including family income or vehicle availability.

- Neighborhood resources, such as the average income of the neighborhood and the availability of public transportation.

One way that the U.S. Department of Agriculture identifies food deserts is by searching for low-income, low-access census tracts.

In low-access census tracts, a significant share ( 33 % or more) of residents must travel an inconvenient distance to reach the nearest supermarket or grocery store (at least 1 mile in urban areas and 10 miles in rural areas).

In low-income census tracts, the local poverty rate is at least 20 % or the median-family income is at most 80 % of the statewide median family income.

Mapping food deserts in the United States

How many Americans live in food deserts?

Nearly 39 . 5 million people — 12 . 8 % of the U.S. population — were living in low-income and low-access areas, according to the USDA’s most recent food access research report , published in 2017 .

Within this group, researchers estimated that 19 million people — or 6 . 2 % of the nation’s total population — had limited access to a supermarket or grocery store.

Why do food deserts exist?

There is no single cause of food deserts, but there are several contributing factors. Among them:

- Transportation challenges — Low-income families are less likely to have reliable transportation, which can prevent residents from traveling longer distances to buy groceries.

- Convenience food — Low-income families are more likely to live in communities populated by smaller corner stores, convenience markets and fast food vendors with limited healthy food options.

- Added risks — Opening a supermarket or grocery store chain is an investment risk, and this risk can grow to prohibitive proportions in lower-income neighborhoods. For example: The purchasing power of customers in these communities — including families enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — can change dramatically over the course of a month. At the same time, the threat of higher crime rates, whether real or perceived, can raise a business’s insurance fees and security costs.

- Income inequality — Healthy food costs more. When researchers from Brown University and Harvard University studied diet patterns and costs , they found that the healthiest diets — meals rich in vegetables, fruits, fish and nuts — were, on average, $ 1 . 50 more expensive per day than diets rich in processed foods, meats and refined grains. For families living paycheck to paycheck, the higher cost of healthy food could make it inaccessible even when it’s readily available.

How has the coronavirus pandemic impacted food access?

The coronavirus pandemic injected even more challenges — both logistical and financial — into the complex field of food access.

As COVID- 19 cases rose across the country, restaurants, corner stores and food markets — among other businesses — closed their doors or reduced their operating hours. Residents who relied on public transportation for fetching groceries faced additional hurdles, including new travel restrictions and scaled-back service schedules.

Beyond making it harder to get to the grocery store, the pandemic also kicked off an economic crisis that made it harder for some families to afford groceries. In fact, nearly 10 % of parents with only young children — kids ages five and under — reported having insufficient food for their families and insufficient resources to purchase more, according to a fall 2020 food insecurity update from Brookings.

What solutions to food deserts can be pursued?

Environmental, policy and individual factors shape eating habits and patterns — both personally and collectively, according to Joel Gittelsohn, a public health expert at Johns Hopkins University. Within this complex landscape, some strategies for alleviating food desert conditions include:

- Incentivizing grocery stores and supermarkets in underserved areas.

- Funding city-wide programs to encourage healthier eating.

- Extending support for small, corner-type stores and neighborhood-based farmers markets.

- Partnering with the community when selecting food desert measurements, policies, and interventions.

- Expanding pilot efforts allowing customers to use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits to purchase groceries online.

Casey Foundation resources on food insecurity and food access

The Kids, Families and COVID- 19 KIDS COUNT ® policy report highlights pandemic pain points, including the uptick in food insecurity across the United States.

Food at Home , a Casey-funded report, explores leveraging affordable housing as a platform to overcome nutritional challenges. The publication touches on food deserts and their impact on communities across the United States.

A September 2019 Data Snapshot shares recommended moves that leaders can take to help families in high-poverty, low-opportunity communities thrive.

National statistics on kids and food insecurity , via the KIDS COUNT Data Center.

This post is related to:

- Concentrated Poverty

- COVID-19 Responses

- Health and Child Development

Popular Posts

View all blog posts | Browse Topics

blog | January 12, 2021

What Are the Core Characteristics of Generation Z?

blog | June 3, 2021

Defining LGBTQ Terms and Concepts

blog | August 1, 2022

Child Well-Being in Single-Parent Families

Subscribe to our newsletter to get our data, reports and news in your inbox.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Growing Math

Classroom-ready learning resources for grades 3-8.

Food Deserts, Indigenous Seeds and Data Stories

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RST.6-8.3 Follow precisely a multistep procedure when carrying out experiments, taking measurements, or performing technical tasks.

CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.6.SP.B.4 Display numerical data in plots

CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.6.SP.B.5 Summarize numerical data sets in relation to their context

CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.7.RP.A.2 Recognize and represent proportional relationships between quantities

70 – 90 minutes, including cooking activity

📲 Technology Required

A computer with projector or smart board is required to show the video and presentation to students.

This truly cross-curricular assignment begins by watching a video about seed rematriation, that is returning Indigenous seeds to their original lands. They read a short booklet on cooking and nutrition, then do a cooking activity at school or home. A presentation on food deserts includes definitions, data and actions students can take. Students add new words or phrases to their word journal and complete a math assignment using data from the presentation. Advanced students play a game to learn more math and Navajo culture.

Watch this video seed rematriation, that is, growing Indigenous seeds in the lands from which they came originally.

Read a short booklet on cooking and nutrition

Scrambled eggs and spinach – available here as a free pdf from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is directed at parents but should be at the reading level of most sixth- or seventh-graders.

Make some eggs

It will be a lot more fun for your class if you can actually go to the school kitchen and cook some eggs. Reading the booklet above will give the recipe, optional ingredients and much more. The only 3 ingredients you absolutely need are eggs, spinach and vegetable oil or butter.

Alternative assignment

If you absolutely cannot go to the kitchen at school because of scheduling, safety regulations or other reasons, here are two other options.

- Assign this activity for students to do with their parents at home. Here is the link for the recipe. You can make this an extra credit activity because not everyone has parents who have time or money to run out for eggs and spinach. Optional: If students have access to a phone or tablet, have them record themselves/ their parent cooking.

- You can watch a video of kids making the recipe , but doing it with your class will be more fun.

Listen to/ read presentation on food deserts

What if there was nowhere to buy eggs, spinach or even seeds near where you live? You can use this Google slides presentation to present to students in class or assign them to read on their own .

Complete word journal

Students add words or terms with which they are unfamiliar to their word journal. Some teachers call it a personal dictionary, to others it’s a word journal. Regardless, the goal is the same, for students to record new words, give a dictionary definition and “make the word their own”. This can be done by rewriting the definition in their own words, using the word in a sentence or including an illustration of the word.

Two dictionary sites to recommend for definitions are below. An added bonus to mention to students is that they can hear words pronounced.

- Cambridge Dictionaries Online

- Merriam-Webster OnLine

Since students often ask for an example, here is an example you can link in your lesson .

The personal dictionary assignment, with all links, can be found here . Feel free to copy and paste into your Google classroom or other site, or print out for your class.

Math assignment: Using statistics and ratio to answer questions

Copy the assignment into your Google classroom or other system or print out for students. Students will use the data from the Food Deserts presentation to answer questions about percentages. They will also create pie charts (circle graphs) and bar charts. You can have students do this with a calculator or pencil and paper or using Google sheets.

ANSWER KEY for assignment

If you’d like a spreadsheet where these tables and graphs were created, you can find it here .

Differentiated Instruction: For Advanced Students

Challenge more advanced students to watch this video on Making Mounds for Three Sisters Gardens. The vocabulary is a little more advanced than the typical sixth-grade with terms like “nitrogen”, “fish emulsion”. In the first farm, they planted 80 mounds. Students should watch the video and figure out from the information given how wide the plot must be .

More advanced students can also play the Making Camp Navajo game, available from the Games for Kids portal on this site, to learn more about farming and expand their knowledge of ratio and proportion.

Word journals are graded based on correct or incorrect definition. Data analysis assignments assess student achievement of math standards above.

One thought on “ Food Deserts, Indigenous Seeds and Data Stories ”

Pingback: Cross-curricular Middle School Statistics Unit | Growing Math

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.2: Sample Student Research Essay Draft- Food Deserts

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 124432

- Gabriel Winer & Elizabeth Wadell

- Berkeley City College & Laney College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Reading: Draft of student essay on food deserts

Note: This sample is a rough draft that is not intended to be a model of a polished, finished essay. Since the chapter focuses on clarity and style, the essay can be used as the "before'" version for practicing revision.

17 May 2019

Accessibility and Affordability of Healthy Food Dependent Upon Socioeconomic Status

Have you ever had trouble finding a supermarket when you wanted to purchase fresh vegetables and fruits? Have you ever wondered why there are no supermarkets in certain areas? This phenomenon is especially interesting as people have begun to pay more attention to a healthy diet and lean towards purchasing healthy food, and more and more natural and organic-food stores have opened in recent years. As explained by Michael Pollan, a food detective and expert and the author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma , organic food is considered healthy because “it is grown without chemical fertilizers or pesticides” (133). Even though there are organic grocery stores like Whole Foods seemingly everywhere, it is difficult for some people of lower socioeconomic status, who live in food deserts, to access healthy food due to lack of accessibility and affordability. According to American FactFinder, the median family income in the United States was $70,850 in 2017 (“American FactFinder—Results”). This means that families with a median income below $70,850 are considered to have lower socioeconomic status. Gloria Howerton, professor in the Geography Department at the University of Georgia and the author of “‘Oh Honey, Don't You Know?’ The Social Construction of Food Access in a Food Desert,” mentions that people of lower socioeconomic status usually live in food deserts (741). A food desert is an area where there is a lack of fresh vegetable and fruit providers, such as supermarkets or farmers' markets. Food deserts that exist in places like West Oakland, California, contribute to inequitable health outcomes; however, some solutions are in place to improve this situation.

It’s difficult for people of lower socioeconomic status who live in food deserts to access healthy food because there is a lack of outlets for fresh produce in their community. As Alana Rhone, an Agricultural Economist, and colleagues report, there’s a website known as the Food Access Research Atlas (FARA) that “allows users to investigate access to food stores at the census-tract level” (1). According to the United States Department of Agriculture ERS, the measure of food access is based on proximity to the nearest store, and the number of households without a vehicle (“Documentation” para 2). As specified by FARA, 33% of residents in West Oakland are at least one mile away from any supermarket, and one-third of its residents do not have vehicles. For urban areas, such as West Oakland, the USDA defines that “a tract is considered low access if at least 100 households are more than a half-mile from the nearest supermarket and have no access to a vehicle” (“Documentation” para 8). Given the facts above, one can reasonably assume that if people don’t have a car and need to take a bus to access healthy food, it will cause inconvenience and lower their willingness to purchase healthy food. It’s harder to calculate the time it will take to go on the supermarket trip when one is taking public transportation. As a result, if one buys fresh milk but has to spend much time on taking public transportation to return home from a supermarket, the fresh milk may spoil. In contrast, if people own private vehicles, they can easily plan the trip and be willing to travel longer distances to a supermarket to purchase healthy food. Therefore, it’s hard for residents of West Oakland who live in food deserts to access healthy produce since there are insufficient outlets to fresh food in their community.

It’s also tough for people of lower socioeconomic status to buy healthy food because they cannot afford high-end organic food. According to American FactFinder, the median family income in West Oakland was $35,037 in 2017, which is below the U.S. median family income of $70,850. Based on the data above, residents in West Oakland are considered to be of a lower socioeconomic status. As mentioned previously, organic food has no chemical fertilizers or pesticides, and as stated by Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, the 6th Edition. 2019, “organic farming requires more manual labor and attention” (“Organic food.”), so its price is higher than conventional food. Take salted butter as an example; one box of four bars of organic salted butter costs $5.29, while one box of non-organic salted butter only costs $3.49 (as listed on the Whole Foods website). Additionally, as reported by an article, “Socioeconomic Status and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: Impact of Dietary Mediators,” written by many Medical Doctor and Doctor of Philosophy, “Low-income families purchase low-cost items” because “the price of fruit and vegetables was the most determinative barrier in the consumption of these products from low-income families” (Psaltopoulou Chapter: 2.2. Cost). People with lower income may face the difficulty of living a self-sufficient life, much less purchase high-end organic food. Due to the lower income, if people of lower socioeconomic status frequently purchase high-end organic food, it will increase their financial burden. They often tend to consume cheaper and less healthy produce such as processed food because the price point is lower, and the portion is larger than that of organic food. As a result, it will be challenging for people with lower income to access healthy food.

However, many residents of West Oakland believe that corner liquor stores are cheaper and more convenient than supermarkets. Admittedly, it is true. They think this because there are many corner liquor stores nearby, and that is convenient for them. They can buy everything they need in a corner liquor stores store and don’t have to travel long distances to a supermarket to access healthy food. Research on Google Maps shows there are at least ten corner liquor stores but no supermarkets like Whole Foods in West Oakland. As stated by Sam Bloch, the author of “Why Do Corner Stores Struggle to Sell Fresh Produce” and a professional writer for The New York Times , L.A. Weekly , and Artnet, most of the corner stores “don’t have walk-in refrigerators” (para 13). Thus, they cannot sell many types of fresh produce because they do not have refrigerators to keep the produces fresh; the food may spoil before being sold. As a result, liquor stores rarely provide healthy food choices, such as fresh vegetables and fruits, meat, or dairy. Hence, even if many liquor stores nearby are convenient, one is barely able to find healthier produce. In the long-term, those that constantly shop at corner liquor stores may only gain convenience but lose in health and well-being.

Although the lack of accessibility and affordability may obstruct people of lower socioeconomic status who live in food deserts to access healthy food, luckily there are some existing resources that one can make good use to improve this situation, such as food hubs and community gardens. According to Jim Downing, the executive editor of UCANR's research journal California Agriculture, food hubs are nonprofit organizations and “are designed to enable small and mid-scale farms to efficiently reach larger and more distant market channels like campuses and school districts, hospitals and corporate kitchens” (para 5). For instance, Mandela Foods Distribution, a Mandela Marketplace social enterprise, delivers fresh fruits and vegetables to corner stores in low-income neighborhoods in West Oakland (Downing para 6). Food hubs supply fresh vegetables and fruits to low-income communities, and it increases access to healthy foods for residents of West Oakland. Residents can obtain fresh and healthy food through food hubs at Mandela Marketplace. Another resource that helps residents to access healthy food is learning how to grow vegetables and fruits in community gardens. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Establishing a community garden where participants share in the maintenance and products of the garden and organizing local farmers markets are two efforts that community members themselves can do” (“Food Desert” para 4). Community gardens provide places that allow people to plant food for themselves. One of the famous community gardens is known as City Slicker Farms. The goal of City Slicker Farms is “to empower West Oakland community members to meet the basic need for fresh, healthy food by creating sustainable, high-yield urban farms and backyard gardens” (para 1). There are many plots provided to residents to plant vegetables and fruits and to exchange and discuss their gardening experiences at the farm. If residents can make good use of food hubs or community gardens, they can access to healthy food and learn how to grow fresh vegetables and fruits themselves.

This case study shows that the difficulties people of lower socioeconomic status who live in food deserts face in accessing healthy food are lower-income and a lack of supermarkets. Helping people of lower socioeconomic status increase their income to afford healthy produce or building many supermarkets that sell healthy produce may be not easy to achieve. However, to recognize this situation and make good use of existing resources to access healthy food are significant and feasible. For long-term health, people need to consume more healthy food instead of less healthy food such as processed food. In other words, people who consistently consume processed food may negatively affect their health. Since many processed foods have high amounts of added sugar and sodium, they may be associated with some diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease. In brief, people should consume unhealthy food as least as possible. Planting fresh vegetables and fruits in community gardens or going to Mandela Foods Distribution where food hubs supply much fresh food for residents are some of the ways for people who have trouble finding fresh food to access healthy produce. These may be the best ways for people who live in food deserts and belong to a lower socioeconomic status to receive the greatest benefits from limited resources.

Works Cited

“American FactFinder—Results.” American F actFinder - Results , 5 Oct. 2010.

Bloch, Sam. “Why Do Corner Stores Struggle to Sell Fresh Produce?” New Food E conomy , 21 Feb. 2019.

“Documentation.” Economic Research Service , United States Department of Agriculture.

Downing, J. “Food Hubs: The Logistics of Local.” California Agriculture , University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources, 13 Sept. 2017.

“Food Desert: Gateway to Health Communication: CDC.” Centers for Disease Control and P revention , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 15 Sept. 2017.

Howerton, Gloria, and Amy Trauger. “‘Oh Honey, Don’t You Know?’ The Social Construction of Food Access in a Food Desert.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies , vol. 16, no. 4, Dec. 2017, pp. 740–760. EBSCOhost .

“Organic Food.” Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition , Jan. 2019, p. 1. EBSCOhost.

Psaltopoulou, Theodora, et al. “Socioeconomic Status and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: Impact of Dietary Mediators.” Hellenic Journal of Cardiology , Elsevier, 1 Feb. 2017.

Pollan, Michael. Young Readers Edition: The Omnivore’s Dilemma: The Secrets behind What You Eat. New York: Dial, 2009. Print.

Rhone, Alana, et al. “Low-Income and Low-Supermarket-Access Census Tracts, 2010-2015.” A gEcon Search , 1 Jan. 2017.

"Salted Butter". Whole Foods. P roducts.wholefoodsmarket.com.

Licenses and Attributions

Cc licensed content: original.

Authored by Amanda Wu, Laney College. License: CC BY NC.

- Driver Application

- Community Impact

- Nutrition partners

- News and Blogs

- Registration

School Lunches and Food Deserts: Addressing Disparities in Access to Nutritious Meals

In this age of knowledge-driven societies, the connection between the nutritional choices students make and their cognitive development has gained significant attention. We delve into the profound impact of nutritious meals on young minds and how a well-balanced diet can bolster academic performance.

The term “food desert” might seem like a distant concept, but its effects resonate closer to home than one might think. Unraveling the complex web of factors that contribute to this challenge, we investigate how socioeconomic realities shape students’ access to nourishing school lunches.

The Importance of Nutritious School Lunches

As childhood obesity rates rise and health concerns escalate, the role of nutritious school lunches in maintaining well-being cannot be overstated. Our exploration takes us into the world of balanced diets and their role in preventing a host of health issues, showcasing inspiring instances of schools pioneering change.

The human brain is a remarkable instrument, and the fuel it requires is as critical as the air we breathe. We dissect the nutrients that are key to optimal cognitive function and demonstrate how these elements are present in meticulously planned school lunches. Research underscores the undeniable link between nutrition and heightened cognitive abilities in students.

Ingraining healthy eating habits early on is a gift that keeps on giving. We venture into the realm of schools as influencers, revealing how exposure to nutritious foods during lunchtime can shape lifelong dietary choices. Through tangible examples, we illuminate how schools are making the act of eating an engaging and mindful experience.

The Reality of Food Deserts

Within our neighborhoods lie pockets of scarcity, where the absence of grocery stores reverberates in diets and well-being. We delve into the essence of food deserts, dissecting their defining features and the intricate blend of elements that give rise to these barren nutritional landscapes.

The echo of food deserts reaches far beyond individual plates; it reverberates through communities and shapes the growth and potential of the next generation. We chronicle the tangible consequences of food deserts on children’s health, growth, and academic journey, capturing the uphill battle faced by families entrenched in these circumstances.

Initiatives to Bridge the Gap

In the heart of the challenge, schools emerge as beacons of hope, harboring innovative solutions to bring nourishment to students. We unveil ingenious approaches, shining a light on successful endeavors that ensure students receive the sustenance they need. Collaborations with local farmers, gardens, and food banks showcase the power of partnerships.

When communities unite, remarkable transformations unfold. We delve into the grassroots efforts that are rewriting the narrative of food deserts. From vibrant community gardens to bustling farmers’ markets and nimble mobile food units, we showcase the strength of collective action. Advocacy and policy changes stand as pillars of support for these promising endeavors.

Challenges and Controversies

The reality of education often dances in tandem with financial constraints. We dissect the financial hurdles that schools grapple with when striving to provide nutritious meals. Delving deeper, we explore the potential trade-offs and innovative solutions that can maximize limited resources without compromising on quality.

In our global tapestry, the need for inclusivity resonates deeply. We embark on a journey that addresses the delicate balance between nutrition and cultural diversity. Navigating through the complexities, we spotlight schools that have successfully embraced diverse cultural preferences while serving up wholesome and healthful meal options.

Future Outlook and Potential Solutions

In the digital age, technology holds the promise of transformation. We unlock the potential of technology and innovation in dismantling food deserts. From meal delivery apps to online resources, we envisage a future where technology narrows the gap and empowers individuals to access nutritious meals. Additionally, we explore the horizon of advancements in food production and distribution, envisioning a world where food deserts fade into history.

The gears of change often turn through policy and collective action. We lay out a roadmap of actionable policy changes that span local, state, and national realms. Advocacy emerges as a formidable force, one that can drive systemic change and breathe life into equitable access to nutritious meals. The resounding call for advocacy echoes as we navigate the landscape of policy, driven by the conviction that change is within our grasp.

With the mosaic of insights gathered, we arrive at the crossroads of conclusion. The symphony of evidence and stories underscores the undeniable connection between access to nutritious meals, academic success, and the vitality of communities. As we bid farewell, we carry forth a resolute commitment to nurturing both minds and bodies, ensuring a future where disparities in food access are mere shadows of the past.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. What exactly is a food desert?

A1. A food desert signifies a geographical region with scant access to affordable and nourishing sustenance, often compounded by the absence of grocery stores within reasonable proximity.

Q2. How do food deserts impact children’s academic performance?

A2. The repercussions of food deserts extend beyond plates; they ripple into classrooms. We uncover how deficient nutrition stemming from food deserts can impede cognitive development, concentration, and overall scholastic accomplishments.

Q3. Are there any successful examples of schools tackling food deserts

A3. Indeed, stories of change emerge as beacons of hope. Schools joining hands with local farmers, cultivating gardens, and partnering with community entities portray a narrative where concerted efforts dismantle the barriers of food deserts.

Q4. How can policymakers contribute to solving the issue of food deserts?

A4. The power to rewrite the food landscape rests in the hands of policymakers. Incentives for grocery stores, bolstered school lunch funding, and unwavering support for community-driven initiatives stand as lighthouses guiding the way.

Q5. What role may parents play in establishing good eating habits in their children?

A5. Amid the cacophony of life, parents hold the compass. By orchestrating meal plans, crafting nutritious home-cooked meals, and championing enhanced school lunch programs, parents sculpt a pathway to balanced nourishment for their offspring.

Q6. How might advancements in technology alleviate food desert issues?

A6. Within the realm of screens and algorithms, lies the promise of transformation. We envision a landscape where technology delivers not only meals but also knowledge about nutrition, bridging the divide and ensuring access to healthful sustenance.

Q7. How can individuals contribute to addressing food deserts in their communities?

A7. In the hands of individuals lie the seeds of change. Volunteering, patronizing farmers’ markets, nurturing community gardens, and raising awareness become the conduits through which the fabric of food deserts can be rewoven. By participating in local initiatives, lending a helping hand, and advocating for accessible nutrition, individuals assume the mantle of change-makers, sowing the seeds of transformation in their communities.

The journey through the intricate tapestry of nutrition, academia, and societal well-being has unveiled a profound narrative. From the pivotal role of nutritious school lunches in fostering health and cognitive function, to the pressing realities of food deserts and the initiatives forging pathways towards equilibrium, this exploration has showcased the intricate interplay between sustenance and success.

As the chapters of this narrative converge, the symphony of diverse voices and perspectives echoes resolutely. The conclusive resonance underscores the undeniable truth that access to nutritious meals isn’t merely a matter of sustenance; it’s a cornerstone of vibrant societies and thriving generations. The seeds planted through understanding, action, and advocacy promise to blossom into a future where every student’s potential is nourished, where food deserts are transformed into fertile oases of opportunity, and where the pursuit of knowledge walks hand in hand with the sustenance of body and mind.

Healthy Snack Alternatives: Encouraging Nutritious Choices Beyond Lunchtime

Blogs The Role of Technology in School Lunch Programs: Streamlining...

Recent Post

School lunch programs with nutritious meal options, easy ordering, and a commitment to giving back to the community.

Useful Links

- [email protected]

- 289-296-0024

- 7429 Jonathan Dr., Niagara Falls, ON L2H 2T3

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Don’t miss our new offers and get Subscribed Today!

©2022. Food for Good . All Rights Reserved.

Virginia Western hosts STEM Day for K-8 students

ROANOKE, Va. (WDBJ) - Virginia Western Community College will host STEM Day for elementary and middle school students on Saturday, April 13 from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. at 3080 Colonial Ave.

Virginia Western’s Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics departments are teaming up with community partners to provide free activities and food. This event is open to any K-8 student in the region, including Roanoke, Salem, Roanoke County, Craig County, Franklin County and southern Botetourt County. Students and their families from public, private, and home school are welcomed. Children will need an adult with them during the event.

STEM Day will offer inside and outside activities, with stations throughout Virginia Western’s STEM Building and Fralin Center for Health Professions. Activities include Raspberry Pi’s for gaming and coding, robots, dissections, DNA extractions, specimens and anatomical skeletons, animals, rocks of Minecraft and more.

Subjects involved in the activities will include chemistry, mechatronics, geology, physics, biology, agriculture, engineering, math, information technology, biotechnology and astronomy.

STEM faculty members Lanette Upshaw and Heather Lindberg are coordinating the event, which is in its second year. “This year, we will have a look at STEM in the military through some of our activities,” she said. Optional donations will be accepted for Virginia Western’s Armed Forces Student Association, “as a way of supporting our students who are veterans.”

Last year, about 2,000 people attended the inaugural STEM Day. “We were so gratified at the community response last year, and our faculty and staff have been working ever since to expand and craft another quality experience for kids,” said Virginia Western Dean of STEM Amy White. “We know how important it is for students to engage with STEM concepts early in life, so they see the wide array of exciting careers that are attainable.”

Community partners include Blue Eagle Credit Union, Freedom First Credit Union, Mission BBQ, Novonesis, Roanoke County and Salem Police Departments, Roanoke City and Roanoke County Fire Departments, the Roanoke County Sheriff’s Office, Virginia Department of Forensic Science, Virginia Tech’s Baja team, Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Virginia Tech’s formula race car and motorcycle team, VPT, Inc., and WJJS.

Copyright 2024 WDBJ. All rights reserved.

Pedestrian hit in Roanoke traffic dies

Man arrested in connection to fatal shooting of a woman

Missing Franklin County child found after two months

Roanoke couple “constantly” catches thieves on security camera

FIRST ALERT: Isolated thunderstorms possible later this week

Latest news.

Full Forecast: Wednesday morning update

Palestine Protesters Interrupt Blacksburg Meeting

Two Arrested for Henry County Armed Robbery

Parents Concerns Over Lynchburg School Budget Cuts

Lynchburg parents voice concerns for lack of transparency about school budget plans

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This lesson explores the concept of food deserts and the relationship between food deserts, poverty and obesity. Students are encouraged to examine their personal access to a healthy diet; compare prices of common staple items among different retail options; and analyze the causes and consequences of food deserts locally and nationally.

6. As students are working on their tables, project/post the Food Desert Solutions image. a. Once the class is re-assembled, the teacher should read and explain the 7 solutions offered in the infographic. b. Tell the class that each group will be creating something related to at least one of the suggested solutions.

Community Food Security and Food Desert Mapping Social Studies [20 minutes] Explain that food security can be measured at the household, community, and national levels. Community food security deals with the features of a community that might affect people's ability to get enough healthy food. Have students brainstorm what some of these

What is Food Justice? Food justice, in the simplest of terms, is equality. It's about ensuring everyone, regardless of wealth, race, or location, has access to the same foods. There are three main aspects of food justice: Access to nutritious and fresh foods. Living wage jobs for all food system workers.

Food Deserts Station: Examples of processed and packaged convenience store food items. Part I: Introduction to food sustainability and environmental issues (15 min.) ... These activities require students to have access to computers with Internet connections. Teacher tip: If you are not able to devote two days to all of the Journal activities, ...

Students will be able to identify the causes of a food desert. Students will recognize what influences grocery store locations. Lesson Context: This lesson occurs in the unit after we have already looked at where food comes from and how income can play a role in limiting access to nutritious food. We are continuing to explore the inequities of ...

Summary Students read an article about food deserts and develop a usable definition of food desert for the purposes of their own research. Students then identify and map the locations of food stores within their own community, as well as graph and use census data to determine if their community is a food desert.

The authors aimed to educate college students on food deserts—what they are and why they exist—and to use the example of food deserts to guide students in developing critical and creative problem-solving. ... Included in EL are activities (e.g., cases, projects, simulations) that seek to emulate or address real-world ...

Synopsis. In this lesson, students practice analyzing a sustainability problem with the concept of food deserts. After reading an article about food deserts, groups of students discuss the article and build a fishbone diagram to highlight the central problem and contributing factors. Then, groups consider possible food desert solutions and ...

The United States Department of Agriculture has joined forces with the Departments of Treasury and Health and Human Services to bring resources and expertise to support strategies that eliminate food deserts. The Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service developed the food desert locator, which is an interactive map that provides the spatial locations and population demographics ...

Thus, I developed an assignment to help students examine food deserts in an urban area with the overall goal being to understand the impact of food deserts in our communities and how they contribute towards perpetuating food insecurities and injustices. Students were encouraged to independently define food deserts and relate the term to urban ...

that address food deserts ASSIGNMENT Estimated Time: ~20 min • Watch "Food Deserts in D.C." (~3:30 min) • Read "Food Deserts Become Food Swamps" (~3 min) • Read "Food Swamps Are the New Food Deserts" (~3 min) • Explore this Food Desert Map administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Food at Home, a Casey-funded report, explores leveraging affordable housing as a platform to overcome nutritional challenges. The publication touches on food deserts and their impact on communities across the United States. A September 2019 Data Snapshot shares recommended moves that leaders can ...

Food Deserts assignment. a mandatory discussion about the topic of the week. Course. Teaching Elementary School Health (HED 424) ... Students also viewed. Fitness in Schools - Thoughts and Summary about an article from the online summer course ... A food desert is a place where communities don't have full access to grocery stores. Or there ...

U.S. Forest Service worker teaching a young boy about plants in the Food Forest in Atlanta, Georgia. Imagine walking through a neighborhood park and collecting fruits, nuts, and vegetables to eat when you get home. That's what kids and people of all ages are going to be able to do in a "food forest" being planted in Atlanta, Georgia.

This truly cross-curricular assignment begins by watching a video about seed rematriation, that is returning Indigenous seeds to their original lands. They read a short booklet on cooking and nutrition, then do a cooking activity at school or home. A presentation on food deserts includes definitions, data and actions students can take.

The Social Construction of Food Access in a Food Desert," mentions that people of lower socioeconomic status usually live in food deserts (741). A food desert is an area where there is a lack of fresh vegetable and fruit providers, such as supermarkets or farmers' markets. Food deserts that exist in places like West Oakland, California ...

We dissect the nutrients that are key to optimal cognitive function and demonstrate how these elements are present in meticulously planned school lunches. Research underscores the undeniable link between nutrition and heightened cognitive abilities in students. Ingraining healthy eating habits early on is a gift that keeps on giving.

The Eradicating Food Deserts in Neighborhoods through the Development of School Gardens project seeks to successfully educate local community people and students on the importance of growing their own produce. The project will utilize a holistic, hands-on approach to gardening in conjunction with the newly developed, self-produced SUAREC Community Gardening Curriculum.

Fine one news, journal, or other article discussing food deserts in Indianapolis, Marian County, or Indiana. Discuss what you learned from the article. Be sure to include a reference or link to your article. Lake County Eats Local brings awareness to food deserts in NWI - NWILife AND food deserts - Data | Indiana (dataindiana)

a. Food deserts are most prevalent in urban areas or communities. In Indianapolis, 20% of residents live in food deserts, according to 2020 research done by IUPUI, and most of those areas are heavily brown and black populated areas. How do you think living in a food desert could affect a person/family's food choices? a.

With this cut-and-paste worksheet, students will create and explain a food web for the desert biome. The steps are as follows: Cut out the ten pictures provided with the resource. Organize the pictures to create a food web. Draw arrows to show the flow of energy within the food web. Write a paragraph to explain how energy flows through the food ...

ROANOKE, Va. (WDBJ) - Virginia Western Community College will host STEM Day for elementary and middle school students on Saturday, April 13 from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. at 3080 Colonial Ave. Virginia ...