Reconstruction: Inquiry High School Lesson Plan

Grades: High School

Approximate Length of Time: 3 hours excluding the final essay

Goal: Students will be able to discuss and cite the outcomes of the reconstruction period – 1863-1877.

Objectives:

- Students will be able to complete questions, finding key information within primary and secondary sources.

- Students will be able to address a question about a historic event, providing evidence from primary and secondary sources.

- Students will be able to identify ways in which historic events impact current events.

Common Core Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.2 Write informative/explanatory texts, including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/ experiments, or technical processes.

NCSS Standards for Social Studies:

1—Culture 2—Time, Continuity, and Change 3—People, Places, and Environment 5—Individuals, Groups, and Institutions 6—Power, Authority, and Governance 10—Civic Ideals and Practices

Description:

This is an inquiry lesson where students will do research to answer the inquiry question concerning the reconstruction period following the civil war. Students will develop a hypothesis, search for evidence in multiple primary and secondary sources, and complete a graphic organizer. Through this process students will develop a strong answer to the inquiry question posed at the beginning.

Inquiry Question:

What are the outcomes of the period known as Reconstruction?

- Primary Source Documents Packet

- Some of the secondary sources are links, be sure to allow access to the internet for these documents and videos

- Final Essay

- Highlighters

- The PowerPoint will act as a guide for the lesson. The PowerPoint is so detailed, it can even be done independently by students.

- There are videos within the PowerPoint that should be queued-up ahead of the lesson presentation.

- Documents within the Primary Source packet and Secondary Source packet will be referred to through-out the PowerPoint. Some of the documents are required reading, while others are noted in the PowerPoint as ‘provided,’ meaning the document has been provided but is not required reading. The provided documents might be useful for more in-depth understanding or for research purposes. Students may wish to look over and cite these documents for their essay.

- For each document guiding questions are provided, it is up to the teacher as to whether or not these need to be answered. The questions help focus students’ attention and guide in the formation of their own document related questions.

- Students should provide citations to documents as they complete the storyboard, this will act as an organizer/outline for their final essay.

Conclusion:

Students will answer the inquiry question either orally or in essay form (Essay is provided). They should use evidence from their primary and secondary sources. They can use the documents, their notes, the storyboard, and their answered questions. Students can do additional research to bolster their argument.

Assessment in this Lesson:

- Completed storyboard.

- A complete answer to the inquiry question with citations from the provided documents.

6 Primary Sources from the American Civil War

Antietam 360: Natural and Man-made Features Middle School Lesson Plan

The Civil War Animated Map: Traditional Middle School Lesson Plan

Civil War & Reconstruction

Lesson plan.

The Civil War and Reconstruction Era brought about the end of slavery and the expansion of civil rights to African Americans through the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Compare the Northern and Southern states, discover the concepts of due process and equal protection, and understand how the former Confederate states reacted to the Reconstruction Amendments.

Pedagogy Tags

Teacher Resources

Get access to lesson plans, teacher guides, student handouts, and other teaching materials.

- Civil War and Reconstruction_Lesson Plan.pdf

- Civil War and Reconstruction_StudentDocs.pdf

I find the materials so engaging, relevant, and easy to understand – I now use iCivics as a central resource, and use the textbook as a supplemental tool. The games are invaluable for applying the concepts we learn in class. My seniors LOVE iCivics.

Lynna Landry , AP US History & Government / Economics Teacher and Department Chair, California

Related Resources

A movement in the right direction (infographic).

Breaking Barriers: Constance Baker Motley

Civic action and change.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Historical Monuments & Meaning

Little Rock: Executive Order 10730

Resisting slavery, slave states, free states, slavery: no freedom, no rights.

See how it all fits together!

Civil War and Reconstruction Toolkit

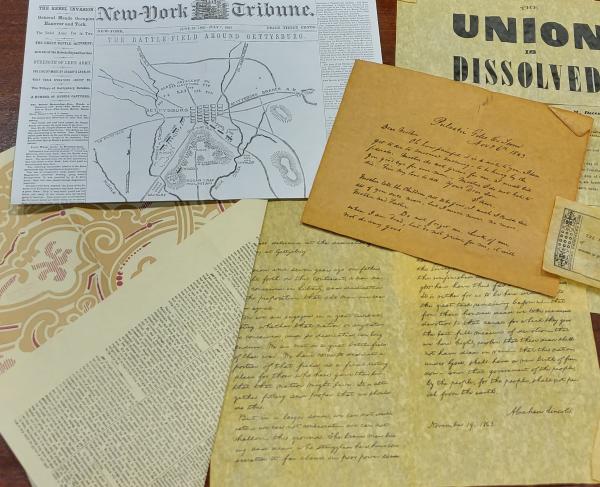

The American Civil War was fought from 1861-1865, and followed by the period of Reconstruction, generally accepted by scholars to have ended in 1877. The following collections include documents essential to gaining and understanding of how the war began, progressed, and ended, and how Reconstruction was conceived and attempted.

Guiding Questions

- What did Americans think about slavery and emancipation as a constitutional matter, and how did their disagreement over the institution and its possible elimination shape the coming of the Civil War and its prosecution?

- How did Americans understand secession and the problem it posed for the viability of self-government?

- How did Lincoln and Americans understand the nature of the federal union and Constitution in relation to state sovereignty?

- What problems did Reconstruction pose for Presidents and Congresses both during and after the Civil War, and to what extent did the federal structure of the American union, along with the 13 th , 14 th , and 15 th Amendments, complicate the return of peaceful self-government to the United States?

Suggested answers

Essential Documents

- Fragment on the Constitution and Union , 1861, Abraham Lincoln

- South Carolina Declaration of Causes of Secession , 1860

- “Corner Stone” Speech , 1861, Alexander Stephens

- The War – Its Cause and Cure , 1861, William Lloyd Garrison

- Message to Congress in Special Session , 1861, Abraham Lincoln

- Letter to Horace Greeley , 1861, Abraham Lincoln

- Final Emancipation Proclamation , 1863, Abraham Lincoln

- Gettysburg Address , 1863, Abraham Lincoln

- Resolution Submitting the Thirteenth Amendment to the States , 1865, Abraham Lincoln

- Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln , 1876, Frederick Douglass

- Documents in Detail: Gettysburg Address

- Moments of Crisis: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

- Documents in Detail: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address

- American Controversies: Did Lincoln Violate the Constitution?

- Great American Debates: Secessionists vs. Unionists

- American Minds: Frederick Douglass

- Documents in Detail: Lincoln’s Fragment on the Constitution and Union

- Special Webinar: What Can We Learn from the Election of 1860?

- Special Webinar: Heroes of the Civil War

- Enduring American Questions: Did Slavery Cause the Civil War?

- Documents in Detail: “Cornerstone” Speech

- Documents in Detail: Final Emancipation Proclamation

Lesson Plans

- On the Eve of War – A one-day lesson focused on the relative strengths and weaknesses of the North and the South on the eve of the American Civil War

- Battles of the Civil War – Help students learn the essentials about important battles of the war in this two-day lesson

- Abraham Lincoln and Wartime Politics – This in-depth 3-4 day lesson explores Lincoln’s handling of the war as a political event

- Abraham Lincoln on the American Union – a four-lesson arc examining the president, his ideas, and his actions

- The Battle over Reconstruction – a three-lesson mini-unit on the tumultuous years after the war

- Making Sense of Secession – a week-long sequence of lessons exploring Southern justifications – constitutional, legal, and moral – for secession

- Civil Rights, Andrew Johnson, and the Radical Republicans – a 3-day lesson sequence helping students understand the foundation of the post-Civil War Civil Rights movements

Receive resources and noteworthy updates.

Lesson Plans

- Primary Documents

- Video Transcripts

- Instructions

- The Backstory

Lesson overview: Freedpeople built and expanded existing institutions during Reconstruction, many of which had their roots in practices begun by enslaved people. They included religion, education, benevolent organizations, the press, and the family. Today’s lesson titled, “Teaching Ourselves,” focuses on education. The power of education was incalculable. Even before the Civil War, the South had the highest rate of illiteracy for both Black and white populations. Although benevolent organizations such as Northern missionary societies, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and other supporters raised money to support teachers and build schools for freedpeople, it was the formerly enslaved who worked the hardest to educate themselves. The Reconstruction governments elected after the enfranchisement of Black men founded more than 3,000 schools. Freedpeople, even the poorest, held fundraisers to pay teachers, and donated land and labor to build schools.

Essential Question: How did freedpeople use institutions to create social change during Reconstruction?

Driving Questions: Why did freedpeople consider education an integral institution during Reconstruction?

Lesson Progression

- The teacher will introduce Reconstruction 360 and determine prior knowledge about the Reconstruction period through classroom discussion. If the class has completed the module “A Seat at the Table,” prior knowledge could include five things students learned from completing that lesson.

- The teacher will direct students in watching the immersive 360 video/module, “Teaching Ourselves.”

After showing the module, the teacher will give students a prompt and lead students in a discussion:

Prompt: Places have personalities. The personality of a place often reflects its purpose and those who inhabit it. Before doing any research, it is helpful to record first impressions. In watching the “Teaching Ourselves” scene, what can you learn about the place where the scene was shot and the people in the scene?

What are your initial observations about the place and the people shown in the video “Teaching Ourselves” ?

Portrait of Lincoln

Group of Children

Spelling Book

- Neighbor – Older Woman

- Teacher – Younger Woman

- Church Pew – Church as School

- Stack of Books – Freedmen’s Bureau

- Pulpit – Missionary Societies

Chalkboards

Map of the World

- Groups should use their device/devices to rewatch the video and explore the various immersive aspects of the 360 technology, especially focusing on the embedded videos. The teacher should encourage groups to explore all the videos, not just the one assigned to their group.

- After groups have had time to explore the features of “Teaching Ourselves,” the teacher will give each group a central question that requires groups to define the primary aspects of their hot spot. Each group must write one group-agreed-upon response to their question.

- The teacher will place a masking tape line on the wall of the classroom. The line will represent the spectrum of responses that groups and individuals may have. One end of the line will indicate a “100%/Absolute Yes” response. The other end of the tape will represent a “0%/Absolute No” response with tags for 75%, 50%, and 25% as well.

- The teacher will ask each group to Walk the Line , one group at a time. The groups will choose a percentage of certainty they feel about their response.

- Using a worksheet, each group will record their percentage choice along the spectrum, as well as their written justification of their choice. The group will in turn place themselves on the tape beside the percentage they have chosen.

- The group will read their response to the teacher prompt to the entire class.

- Students in other groups will make a judgement based on their personal interpretation of the prompt, which was read by the presenting group. Individual students will place themselves along the continuum wall line, choosing a percentage that represents their view of the prompt.

- The teacher should advise individual students that they may be questioned about their choice of percentage. Students should be prepared to justify their choice if questioned.

- This process will continue until all 10 groups have presented. When all the presentations are completed, the continuum wall line should have markers indicating the percentage chosen by each group as well as their written responses which are taped under the percentage they chose.

Hot Spot Prompts

Think about time and how perception changes as time passes. Given the time between Lincoln’s assassination and the opening of schools for children of former slaves, how would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Former slaves were justified in idolizing Lincoln and giving him the title of the Great Emancipator.

Our group feels the response to the prompt falls at this percentage along the spectrum:

We feel that it falls at this percentage because:

Think about the period following emancipation. What opportunities were available to families that were new to their lives as emancipated people? How would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Education seemed to distract from the responsibilities of living and surviving as newly freed people.

Communication has many components. Slavery purposely limited how those enslaved were allowed to communicate. Thinking of communication and its many components, how would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Noah Webster’s Elementary Spelling Book impacted the way freedmen interacted and communicated with those in and out of their communities.

Older Woman – Community Member

Schools are part of our community. Communities form the foundation of larger societies. Think about how difficult it was for children of freedpeople to become educated citizens. How would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Education for children of freedpeople was difficult because support from communities and society was sparse.

Younger Woman – Teacher

Often historians evaluate periods of time based on the words and actions of past leaders of a particular period. Reconstruction is marked by leaders and groups trying to provide opportunities where they once did not exist. How would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Normal schools were a jewel in the crown of Reconstruction, providing educational opportunities for freedmen throughout the South.

Church as School – Pew

Freedpeople left slavery with very few possessions and what little they could carry. Think about what institutions define a society. If your family, and those you know, were in a similar situation, what institutions would you be sure to include in your new community? What issues are you going to have to confront? How would your group respond to the following prompt:

Teacher prompt: Communities created by freedmen often relied on the generosity of white land owners to establish needed institutions.

Freedmen’s Bureau – Stack of Books

Think about radical change and how people react when old established traditions are no longer practiced. In what ways would an organization like the Freedmen’s Bureau be helpful to people who are trying to establish themselves in society? How would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: The Freedmen’s Bureau was an offshoot of the US military and was not helpful in promoting education in African American communities.

Missionary Societies – Pulpit

A benevolent act is defined as charitable act that is intended to benefit rather than profit. Think about the different charitable organizations today that help people throughout the world and during times of need. Many of these organizations have been started and funded by churches and their congregations. Looking at how the private sector can and does help the public sector of society, how would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Many private benevolent societies from the North came to the South to help freedpeople learn skills needed to function in a free society.

Educational aids have existed for well over 5,000 years. In this activity you are using tablets and/or computers to watch videos and explore hotspots found in the Teaching Ourselves video. How would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Educational aids help students learn.

Slavery closed educational and geographic boundaries. Think about individuals who escaped slavery and were able to travel. Imagine how their view of the world changed when they traveled to places where slavery was abolished. How would your group respond to the following prompt?

Teacher prompt: Travel can change perspectives and give knowledge to the traveler and those he/she impacts.

Group Assessment Activity

As a final assessment of what students have learned from Teaching Ourselves , and to answer the Driving question, groups will be asked to continue the “Slide Book” begun with the module A Seat at the Table . If that lesson was not completed, students must create a new “Slide Book”. If this is a continuation of the first “Slide Book” students will be adding a chapter 4 titled My Driving Question Explained in a Six-Word Novel .

- A Six-Word Novel succinctly explains the gist of a topic or question. Groups must brain-storm and come up with six words they believe encapsulates a response to the driving question, Why did freedpeople consider education an integral institution during Reconstruction?

- An example of a Six-Word Novel can be found in Ernest Hemingway’s challenge to write a novel using only six words. His response was as follows: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

- Six-Word Novels may generate further questions or discussion. There is an additional activity in the Lesson Extension section below that will allow students to explore this aspect of Six-Word Novels.

- There should be one master Slide Book for the class. Each group will add their Six-Word Novel to a page under the chapter titled My Driving Question Explained in a Six-Word Novel .

Lesson Extensions

- If time permits, a logical extension of the lesson would be to allow different groups to ask questions that the Six-Word Novel did not address. For example, in Hemingway’s novel one might want to know why the baby shoes were never worn. The teacher can determine a maximum or minimum number of questions each group can generate and specifically whose novel they are to ask questions about.

- Refer to the video found by clicking on the flowers given to the teacher. As an additional activity students can research the types of wildflowers found in their local area by taking pictures of wildflowers in their neighborhood and identifying them using an application or different resources. We have listed some resources below. Students can create a simple “plant identification slide show” showing the plant, where it commonly resides, and the season it blooms. Plants must be native to the area. They can be domestic plants or weeds.

- Students can create a biodome that contains common weeds that are found in their area. They should include a written explanation of the plants and how these plants enhance and contribute to local natural habitats.

- Students will refer to the Reconstruction map link found in the resources. The link shows the Confederate states that were occupied during the Reconstruction period. Students can choose a particular state or a Reconstruction military district and must research historically black colleges/universities (HBCUs) that currently still exist but were initially established during the Reconstruction period. Using Google Maps, students will drop pins showing the location of current colleges and/or universities and write a brief description of the school and its history.

Teacher Notes

- Teachers should explore the Reconstruction 360 module “Teaching Ourselves” prior to showing the module in class. On the toolbar of the module there is an “Explore” pull down menu. This menu contains links to all the embedded videos within the module. They can be accessed through this explore option or by scrolling over and clicking the people/topics as the module is shown.

- The teacher can decide whether to allow extra credit using the lesson extension. The top three questions for each Six-Word Novel could be added as an additional page to the class “Reconstruction 360 Slide Book” and could provide additional opportunities for lesson extensions and/or extra credit by having students research the questions they added to the lesson.

- The Teacher Prompts connected to the Walk the Line activity are purposely written to elicit either positive or negative responses. The idea behind this is to force students to really examine their “hot spot” and decide if the prompt is accurate based on the information found in the prompt and on prior knowledge they have learned from other activities completed in the Reconstruction 360 series.

- The teacher can decide where the Reconstruction Slide Books should be published. There are many options including Google Classroom, Nearpod, and Edmodo. A link that allows teachers to view various options has been included in the resources.

- Please note, included in the resources is a link that will provide a listing of all Historically Black Colleges and Universities found in the former Confederate states. Some listed were established after Reconstruction. If completing the lesson extension on maps, students should be aware to only include those colleges/universities that were established in the South during the Reconstruction period.

Six-Word Novel Rubric

Ideas/Content: Your novel is deep and powerful; instead of just being a basic description of your topic. It is centered around a primary idea that explains the relevance of a person or group and their purpose and/or role during Reconstruction.

Word Choice: You have chosen powerful, vivid, specific verbs and nouns.

Voice: Your novel accurately depicts your person or group’s place in history. Your Six-Word Novel succinctly provides a response to the driving question, Why was education considered an integral institution for freedpeople during Reconstruction?

Connections: Your novel gives accurate information to the reader yet, fosters a desire to learn more about the topic. The reader may have questions that may lead to further investigation.

Lesson Extension Resources

https://backgarden.org/plant-identification-apps/

https://nativebackyards.com/inaturalist-app-to-identify-plants/

http://www.scwf.org/native-plant-list/

Explanation of how to drop a pin on Google Maps – https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/dropped-pins-in-google-maps-how-to-pin-a-location-and-remove-a-pin/

Reconstruction Map link - https://yhoo.it/3p9uUaW

List of historically black colleges and universities - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_historically_black_colleges_and_universities

Slide Book Publishing Options

https://elearningindustry.com/the-5-best-free-tools-for-publishing-student-work

https://nearpod.com/

https://new.edmodo.com/

SC Standards

Grade 4: Standard 5 – Indicators 4.5.CO, 4.5.P, 4.5.CX

Grade 8: Standard 4 – Indicator 8.4.CO

US History and the Constitution: Standard 2 – Indicators USHC.2.CC, USHC.2.E

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Lincoln’s Reconstruction Plan

By rosanne lichatin, essential question.

To what degree was Abraham Lincoln successful in achieving his goals?

The Civil War was perhaps the most momentous event that the United States endured in its history. Author and historian Shelby Foote said, "Any understanding of this nation has to be based on an understanding of the Civil War. . . . It was the crossroads of our being." The key personality in that contest was President Abraham Lincoln, who had the arduous task of steering this nation through the war and also the more difficult challenge of determining a course for peace and Reconstruction. As war leader and peacemaker, he faced criticism from political opponents as well as from members of his own party. This lesson will allow students to explore Lincoln’s words, speeches, and proclamations in order to understand his views on secession, amnesty, and Reconstruction, as well as his hopes for the nation.

- Students will examine primary documents in order to understand and evaluate Lincoln’s plans for Reconstruction.

- Students will be able to identify the specific proposals Lincoln made for the readmission of Southern states, amnesty, and opportunities for freedmen.

- Students will analyze the conflict between the executive and legislative branches in trying to assert control over Reconstruction during Lincoln’s term.

- Students will recognize the need for cooperation and compromise in creating federal policy on Reconstruction.

- Students will recognize the significance of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address in setting the tone of reconciliation for the nation.

- Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction , University of Maryland

- Wade-Davis Bill , Our Documents

- Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address , Yale University, Avalon Project

Homework Assignment #1

Divide the class in half. One half will be assigned Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. The other half will read the Wade-Davis Bill.

Students should answer the following questions in writing and be prepared to discuss them in class the next day:

- Who is the author of this document and when was it produced?

- According to the document, who should control Reconstruction?

- According to the document, what is the role of the executive branch? The legislative branch?

- What conditions must be met for Southern states to be readmitted to the Union?

- Who should be excluded from readmission? Is a rationale provided to justify this exclusion? Do you support it?

- Does this document indicate any provisions to support or assist former slaves?

- Who do you think would support this document? Who would reject it?

- What do you believe is the strength of this proposal?

- What difficulties do you believe might arise if this proposal was accepted?

- Choose one adjective to describe the terms of this plan. Be prepared to defend your choice.

All students will read the Wade-Davis Bill in class and comment on Lincoln’s response.

- What argument does Lincoln provide for not accepting the Wade-Davis Bill?

- If you had been a member of Congress who had supported the Wade-Davis Bill, how would you have reacted to Lincoln’s pocket veto?

Homework Assignment #2

Students should read Lincoln’s address for homework and come to class prepared to discuss its importance. The class will be divided into groups of three to discuss and respond to the following questions:

- To whom do you think Lincoln was addressing his comments?

- In her book Team of Rivals , Doris Kearns Goodwin says about Lincoln, "More than any of his other speeches, the Second Inaugural fused spiritual faith with politics." Identify specific comments made by Lincoln that prove this statement.

The class will be divided into groups of three to discuss and respond to the homework question.

Suggested Enrichment

The following documents can be shared with students to bring the inauguration and the activities surrounding it to life:

- Read George Rable’s essay, " Lincoln’s Civil Religion ," in the Lincoln issue of History Now (Winter 2005).

- An additional resources for an analysis of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address: "President Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address, 1865," a Spotlight on a Primary Source by Abraham Lincoln

- " An Inaugural Poem " dedicated to Abraham Lincoln of Illinois and Andrew Johnson of Tennessee from the Library of Congress. Printed in the Inauguration Procession of Lincoln and Johnson, Chronicle Junior Each stanza will be assigned to two students to analyze. Students will read the entire poem and then be responsible for reporting the meaning of their stanzas to the rest of the class. As part of that exercise, they will discuss how the poem frames the challenge Lincoln faced in saving the Union.

- Students will read the following in class: Chandra Manning, "Douglass, Lincoln, and the Civil War," History Now 50: "Frederick Douglass at 200," Winter 2018 James Oaked, "Douglass and Lincoln: A Convergence," The Gilder Lehrman Institute

- The teacher will lead a discussion that focuses on the following questions:

- In what way did Lincoln make Douglass feel that he was supportive of African Americans?

- What words from the inaugural address do you think impressed Frederick Douglass the most?

Application

- Write a letter to the editor of a newspaper either supporting or opposing: Andrew Johnson’s plan for Reconstruction OR the Radical Reconstruction plan.

- Write a newspaper editorial responding to Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.

- Create an annotated historical timeline of Lincoln’s Reconstruction policies.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- New Lessons

- Popular Lessons

- Explore by Time Period

- Explore by Theme

- Explore by Resource Type

- This Day In People’s History

- If We Knew Our History Series

- New from Rethinking Schools

- Workshops and Conferences

- Teach Reconstruction

- Teach Climate Justice

- Teaching for Black Lives

- Teach Truth

- Teaching Rosa Parks

- Abolish Columbus Day

- Project Highlights

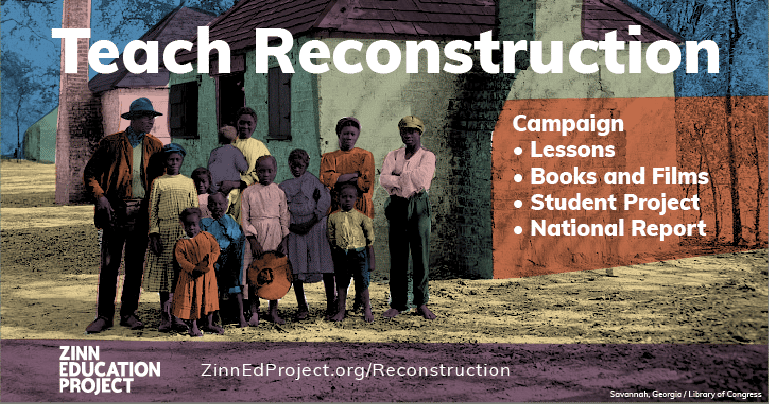

Teach Reconstruction Campaign

Reconstruction, the era immediately following the Civil War and emancipation, is full of stories that help us see the possibility of a future defined by racial equity. Yet the possibilities and achievements of this era are too often overshadowed by the violent white supremacist backlash. Too often the story of this grand experiment in interracial democracy is skipped or rushed through in classrooms across the country. Today — in a moment where activists are struggling to make Black lives matter — every student should probe the relevance of Reconstruction. Our campaign aims to help teachers and schools uncover the hidden, bottom-up history of this era.

We offer lessons for middle and high school, a national report, a student campaign to make Reconstruction history visible in their communities, and an annotated list of recommended teaching guides, student friendly books, primary document collections, and films. This campaign is informed by teachers who have used our Reconstruction lessons and a team of Reconstruction scholars.

Sections: Why • Lessons • National Report • Textbook Critique • Petition • Share Your Story • Related Resources • Student Project • Open Letter • Support • Advisors • In the News

When Black Lives Mattered: Why Teach Reconstruction

Reconstruction, the era immediately following the Civil War and emancipation, is full of stories that help us see the possibility of a future defined by racial equity. Though often overlooked in classrooms across the country, Reconstruction was a period where the impossible suddenly became possible.

Back to top

Reconstructing the South: What Really Happened

A follow-up lesson to “Reconstructing the South,” using primary source documents to reveal key outcomes of the Reconstruction era.

Teaching the Reconstruction Revolution: Picturing and Celebrating the First Era of Black Power

A lesson that help students understand, imagine, and celebrate the Reconstruction period as the first era of Black power in the United States.

Reconstructing the South: A Role Play

This role play engages students in thinking about what freedpeople needed in order to achieve — and sustain — real freedom following the Civil War. It’s followed by a chapter from the book Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution on what would happen to the land in the South after slavery ended.

Teacher Comments “I found the lesson plan to be a valuable addition to my teaching about this era. The students were engaged in their roles and, later, more engaged than ever before in finding out what choices were actually made the years following the Civil War .” — Amy Grant, a middle school social studies teacher, Dexter, Michigan

▸ Read more teacher comments .

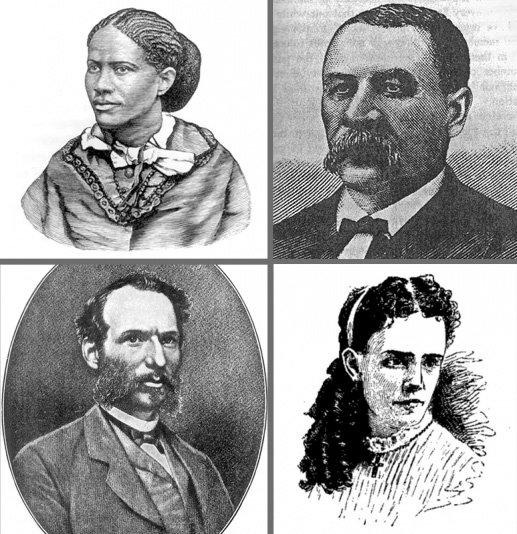

Clockwise: Frances Harper, Isaac Myers, William Sylvis, and John Roy Lynch are a few of the people featured in the role play.

When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer

A mixer role play that explores the connections between different social movements during Reconstruction, introducing students to individuals in the labor movement, women’s rights, and voting rights movements that followed the Civil War and their attempts to build alliances with one another.

Keith Henry Brown

40 Acres and a Mule: Role-Playing What Reconstruction Could Have Been

This multimedia, creative role play introduces students to the ways African American life changed immediately after the Civil War by focusing on the Sea Islands before and during Reconstruction.

Many historians term this post-war experiment in grassroots democracy and Black self-determination that occurred in the coastal Sea Islands a “rehearsal” for Reconstruction. But the Sea Islands experiment was more than a rehearsal; subsequent Reconstruction plans lacked the key ingredient that made it revolutionary: the redistribution of land.

Who Killed Reconstruction? A Trial Role Play

A role play about the demise of Reconstruction that helps students get beyond the question “Was Reconstruction a success or failure?”

This trial role play encourages students to take a broader view of Reconstruction’s demise looking at the role of the major political parties and their wealthy backers, the racism of poor white people, and the systems of white supremacy and capitalism.

More lessons : The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy from Facing History and Almost Emancipated: Reconstruction from Teach Rock.

The Zinn Education Project produced a national report, “ Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction, ” on the teaching of the Reconstruction era, including a state-by-state assessment.

The report, released in January of 2022, examines state standards, course requirements, frameworks, and support for teachers in each state. It also includes stories about creative efforts by districts and/or individual teachers in each state to teach outside the textbook about Reconstruction.

One cannot study Reconstruction without first frankly facing the facts of universal lying,” explained scholar W. E. B. Du Bois in 1935. Spurred by that directive, we offer Five Ways Textbooks Lie About Reconstruction by Mimi Eisen as an addition to our national report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle .

Sign the petition urging school boards to examine how much time is dedicated to teaching the Reconstruction era in kindergarten through 12th grade, make a plan to increase it, and ensure that teaching materials and curricula in schools reflect the everyday people who powered these movements.

Stories from the classroom can inform and inspire more teachers to use lessons on reconstruction. We invite you to share your story . Selected responses will be posted at the Zinn Education Project website .

The “ Make Reconstruction History Visible ” mapping project is an opportunity for students and teachers to identify and advocate for recognition of Reconstruction history in their community. This helps students learn about this vital era in U.S. history while also playing an active role in giving visibility to an era that has been hidden or misrepresented for too long.

For this project, students (individually or as a class) identify and document Reconstruction history such as schools, hospitals, election sites, Freedmen’s Bureau offices, Black churches, Black newspapers, Black owned businesses, prominent individuals, organizations, key events, and more. Learn how to participate .

The Other ’68: Black Power During Reconstruction

Article By Adam Sanchez

From the urban rebellions to the salute at the Olympics, commemorations of 1968 — a pivotal year of Black Power — have appeared in news headlines throughout this anniversary year. Yet 2018 also marks the 150th anniversary of 1868 — the height of Black Power during Reconstruction. Read more .

Related Resources

Readings, primary documents, and films for classrooms about the Reconstruction era .

The Teach Reconstruction campaign is made possible by donations from individuals. Please contribute today so that more teachers receive free lessons on Reconstruction history and more students can participate in the Make Reconstruction History Visible project. Donate now!

- Shawn Leigh Alexander is a professor and the chairperson of African and African American Studies and the director of the Langston Hughes Center at the University of Kansas. Alexander is the author of An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP , and editor of Reconstruction Violence and the Ku Klux Klan Hearings .

- Derek W. Black is a professor of law and the Ernest F. Hollings Chair in Constitutional Law at the University of South Carolina. He is the author of Schoolhouse Burning: Public Education and the Assault on American Democracy .

- David Blight is a professor of history at Yale University and the director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale. Blight is the author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom , A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom , and Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory .

- Greg E. Carr is an associate professor of Africana Studies, the chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University, and an adjunct professor at the Howard School of Law. Carr is a co-founder of the Philadelphia Freedom Schools Movement.

- Michael Charney is a retired public school social studies teacher with over 30 years of experience in education, labor organizing, and education policy. He provides strategic guidance and support for the Teach Reconstruction campaign. Charney wrote curriculum guides to support student organizing including “Fulfilling the Promise of America: The Struggle for Voting Rights,” “ The Minimum Wage and the Youth Vote (PDF),” and the “Present as History: A Look into the Origins of the Cleveland School Desegregation Case.”

- Gregory P. Downs is a professor of history at the University of California, Davis, and the author of After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War . Downs is also a co-author of the National Parks Service’s theme study, The Era of Reconstruction, 1861–1900 .

- Jim Downs is the Gilder Lehrman NEH Professor of Civil War Era Studies at Gettysburg College. Downs is the author of several books including Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction and Beyond Freedom: Disrupting the History of Emancipation , which he co-edited with David Blight.

- Hilary N. Green is a professor of history, Africana Studies Department, at Davidson College. Green is the author of Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865–1890 .

- Steven Hahn is a professor of history at New York University and the author of A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration .

- William Loren Katz was the author of numerous books on U.S. history for middle school students, including An Album of Reconstruction. ( In Memoriam .)

- Chenjerai Kumanyika is a researcher, journalist, artist, and assistant professor in Rutgers University’s Department of Journalism and Media Studies. He is also the co-executive producer and co-host of Uncivil , Gimlet Media’s podcast on the Civil War.

- James Loewen was a professor of sociology at the University of Vermont and the author of several books including Lies My Teacher Told Me , Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong , and The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader: The “Great Truth” about the “Lost Cause” . ( In Memoriam .)

- Kate Masur is a professor of history at Northwestern University and the author of Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction and An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. Masur is also the co-author of the National Parks Service’s theme study, The Era of Reconstruction, 1861–1900 .

- Jeremy Nesoff is the associate program director for Facing History’s Leadership Academy. Among his roles is leading work connected to the curriculum unit The Reconstruction Era and The Fragility of Democracy .

- Paul Ortiz is the director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. Ortiz is the author of Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing & White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920 and An African American and Latinx History of the United States .

- Tyler Parry is an assistant professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is the author of “ Black Radicalism and the ‘Tuition-Free’ University ,” an article exploring the profound impact South Carolina’s majority Black Reconstruction era legislature had on public education.

- Tiffany Mitchell Patterson is a manager of social studies at District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS). Prior to joining the central services social studies team at DCPS, she served as an assistant professor of secondary social studies at West Virginia University. She taught middle school social studies for 10 years in Washington, D.C., and Arlington, Virginia.

- David Roediger is the foundation distinguished professor at the University of Kansas. He is the author of several books on race and class in the U.S. including Seizing Freedom: Slave Emancipation and Liberty for All .

- Mark Roudané is a retired early childhood teacher. He curates the digital archive of his great, great grandfather, Charles Roudanez , who founded the New Orleans Daily Tribune , the first daily Black newspaper during Reconstruction.

- Manisha Sinha is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut. She is the author of The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina and The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition .

- Stephen West is an associate professor of history at the Catholic University of America. West is author of From Yeoman to Redneck in the South Carolina Upcountry, 1850–1915 and co-editor of Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867, series 3, volume 2, Land and Labor, 1866–1867 .

- Kidada E. Williams is an associate professor of history at Wayne State University. Williams is the author of They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I and the producer and host of Seizing Freedom , VPM’s podcast on Black people’s quest for liberation, progress, and joy in the United States.

Educator Survey

Our national report will be continuously updated. Teachers and other staff at the state, district, or classroom level are invited to complete one of the short surveys below. Respondents receive a subscription to Rethinking Schools magazine in appreciation for their time.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Time Period

Resource type.

- Discover Tennessee History

- Newsletters

- U.S. History: Colonial America to Civil War

U.S. History: Reconstruction to Modern America

- World History

- English Language Arts: Reading Informational Text

- English Language Arts: Reading Literature

- English Language Arts: Writing

- Math & Science

- Art & Music

- Career & Technical Education

- Kindergarten to 3rd Grade

- WWII Home Front in TN

- Primary Source Sets

- Analysis Worksheets & Graphic Organizers

- Close-Reading Exercises

- Content Resources & Essays

- I Didn't Learn That

- Themed Guides

- Reconstruction & New South

- Westward Expansion

- Industrial America

- Progressive Era

- World War I

- Great Depression & New Deal

- World War II

- Civil Rights

- Citizenship Timeline Poster

- Excerpts - Select Committee on the Memphis Riots and Massacre

- Voting Rights PowerPoint

- Memphis Rebuilding PowerPoint

- Memphis Rebuilding Reading Excerpts

- Crossing the Veil PowerPoint

- DuBois Extension

- Tennessee Agriculture Primary Source Packet

- Manifest Destiny PowerPoint

- Myth of the Vanishing Race PowerPoint

- Wright Brothers' Flying Evolution PowerPoint

- 5th Grade Student Packet - Social Costs to Industrial Revolution

- High School Student Packet - Social Costs to Industrial Revolution

- Teaching the Labor Movement Thematically Student Packet

- DuBois vs. Washington PowerPoint

- Devil Baby PowerPoint

- Devil Baby Worksheets

- Child Labor: Analysis worksheet for 5th grade

- Child Labor: Analysis worksheet for 11th grade

- Upper Elementary/Middle School Student Packet - Women's Suffrage in the West

- High School Student Packet - Women's Suffrage in the West

- Prohibition in America PowerPoint

- Prohibition Sources

- World War I PowerPoint

- WWI Image Analysis

- Covid-19 Discussion Questions

- Frances Perkins in the Media - Student Packet

- Migrant Mother PowerPoint

- Gee's Bend: Before PowerPoint

- Gee's Bend: After PowerPoint

- Secret City Image Resource

- Palmer Raids and the Red Scare PowerPoint

- Vietnam Anti-War Protest Image Gallery

- Back to Africa PowerPoint

- Songs of the Labor Movement PowerPoint

- Songs of the Labor Movement Info Sheets

- Songs of the Labor Movement Worksheets

- Clinton Twelve PowerPoint

- << Previous: U.S. History: Colonial America to Civil War

- Next: World History >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 8:53 AM

- URL: https://library.mtsu.edu/tps

American Crossroads: Teaching History on the Great Plains

A Teaching American History Project of Lakes Country Service Cooperative, Moorhead Public Schools, and Minnesota State University Moorhead

Site Navigation [Skip]

- American Crossroads

- 2011 Summer Institute

- Internet Classroom Resources

- Archived Material

- Lesson Plans

- Historical Blogs

Reconstruction

Chris Stroup

Teaching American History on the Great Plains

Summer 2010 - Lesson Plan 2

Class: CIHS America History 1301

For students to expand their understanding of the politics, struggles, and shortfalls of putting the United States back together after the American Civil War. Students will examine various aspects of the time period to determined what were the greatest struggles and accomplishments of the time period.

Over the course of two days students will be exposed to a series of materials that will provide information on Reconstruction of the United States following the American Civil War. There are multiple resources available to the students, and they must utilize four, and from these be able and prepared to defend their assigned position on Reconstruction. Oral arguments will follow in class.

A. America: A Narrative History . 6 th Edition. Tindahl and Shi, 2004. Pg 714-735

- Text excerpt explaining the period of Reconstruction

B. Smartboard projection of three main Reconstruction plans (summaries) (attached)

C. “President Andrew Johnson Denounces Changes in His Program of Reconstruction,

1867” (From Major Problems in American History: Vol. 1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman, Jon Gjerde)

- President Johnson presents his argument against franchisement of blacks and his opposing radical reconstruction, which might lead to blacks in the South governing whites – and his fear of this.

D. “Congressman Thaddeus Stevens Demands a Radical Reconstuction” (From Major

Problems in American History: Vol. 1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman, Jon Gjerde)

- Stevens’ argument for radical reconstruction, and his politically motivated reasons behind it.

E. “United States Atrocities” (excerpt) (From Major Problems in American History: Vol.

1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman, Jon Gjerde)

Ida B. Wells

- Wells brings forth the problems faced by the African American community after slavery, including that very little was accomplished during Reconstruction.

F. “DuBois’ Niagara Address, 1906” (excerpt) (From Major Problems in American

History: Vol. 1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman, Jon Gjerde)

- Dubois presents a list of problems facing the African American community, and how in actuality Reconstruction did little for blacks.

G. The Unfinished Nation-Tattered Remains (Downloaded from Learn360)

A clip from the full video: The Unfinished Nation

This clip shows the cultural dynamics taking place between White southerners and former slaves right after the Civil War, as well as providing information on the corruption in the state governments.

Grade: 9-12| ©2004, Intelecom.

H. Reconstruction: Northern Disagreement [08:31] (Downloaded from Learn360)

A clip from the full video: Reconstruction: The Struggles Of Ordinary People

Following election dispute, this clip examines the Northerners not only not embracing the idea of African-American equality, but finally backing off and left African Americans to sink or swim on their own in the South.

Grade: 9-12| ©2004, PBS.

I. Freedom: A History of US: Episode 7: What Is Freedom? (Downloaded from

A clip from the full video: Freedom: A History of US: Episodes 5 - 8

An overview of the post Civil War period, providing information on early attempts to heal, challenges of/for freed slaves, and a look at Plessy v Ferguson.

Grade: 6-8, 9-12| ©2002, PBS.

J. Just the Facts: America's Documents of Freedom 1868-1890 [29:20]

(Downloaded from Learn360)

This short video presents and interprets the documents following the American Civil War and how they helped/hindered in the healing.

Grade: 6-8, 9-12| ©2003, Cerebellum.

K. Reconstruction: The Beginning [19:36] (Downloaded from Learn360)

A clip from the full video: Reconstruction: The Second Civil War: Retreat

Abraham Lincoln's first speech following the Civil War described how the fight of Reconstruction was only beginning. Learn how African Americans struggled to claim their freedom and claim their civil rights in a nation that was wrestling with the idea of their equality.

L. Searching for a New Home in the American West [04:20] (Downloaded from

A clip from the full video: The Unfinished Nation-The Meeting Ground

A brief look at the desire of newly freedmen to move west, and the struggles they encounter through the

many white immigrants also taking advantage of the Homestead Act.

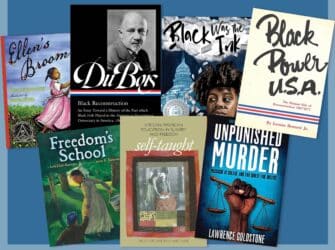

M. Diagram of the Federal Government and American Union by N. Mendal Shafer,

attorney and counseller at law, office no. 5 Masonic Temple, Cincinnati

- Illustrates the intertwined nature of the American republic

N. What a Colored Man Should do to Vote (Pamphlet)

O. Reynolds's political map of the United States

- Demonstrates the area of the free and slave states

Procedures/Culminating Activities:

H-1: Students will have read text account of Reconstruction.

Day 1: Students will be provided projection of the summaries of the major Reconstruction plans, and will be provided a position within the scope of Reconstruction. Video clip providing general information on Reconstruction will be viewed and discussed as a class. Readings will be posted online for students to read on their own prior to day 2.

Day 2: Class will meet in the computer lab to continue research on their position regarding Reconstruction. Of the resources provided (video clips, readings, documents, visuals, etc.) students will investigate and gather information to strengthen their position regarding Reconstruction. They may also research for their own two (2) resources to aid in their arguments.

Day 3: In class, students will propose, argue, and defend their Reconstruction positions. This will continue for a maximum of 3 class periods depending on student engagement.

Resource B. (Each group will only need to read one section, they can read the others)

Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan: 1863–1865

After major Union victories at the battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln began preparing his plan for Reconstruction to reunify the North and South after the war’s end. Because Lincoln believed that the South had never legally seceded from the Union, his plan for Reconstruction was based on forgiveness. He thus issued the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction in 1863 to announce his intention to reunite the once-united states. Lincoln hoped that the proclamation would rally northern support for the war and persuade weary Confederate soldiers to surrender.

The Ten-Percent Plan

Lincoln’s blueprint for Reconstruction included the Ten-Percent Plan, which specified that a southern state could be readmitted into the Union once 10 percent of its voters (from the voter rolls for the election of 1860) swore an oath of allegiance to the Union. Voters could then elect delegates to draft revised state constitutions and establish new state governments. All southerners except for high-ranking Confederate army officers and government officials would be granted a full pardon. Lincoln guaranteed southerners that he would protect their private property, though not their slaves. Most moderate Republicans in Congress supported the president’s proposal for Reconstruction because they wanted to bring a quick end to the war.

In many ways, the Ten-Percent Plan was more of a political maneuver than a plan for Reconstruction. Lincoln wanted to end the war quickly. He feared that a protracted war would lose public support and that the North and South would never be reunited if the fighting did not stop quickly. His fears were justified: by late 1863, a large number of Democrats were clamoring for a truce and peaceful resolution. Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan was thus lenient—an attempt to entice the South to surrender.

Lincoln’s Vision for Reconstruction

President Lincoln seemed to favor self-Reconstruction by the states with little assistance from Washington. To appeal to poorer whites, he offered to pardon all Confederates; to appeal to former plantation owners and southern aristocrats, he pledged to protect private property. Unlike Radical Republicans in Congress, Lincoln did not want to punish southerners or reorganize southern society. His actions indicate that he wanted Reconstruction to be a short process in which secessionist states could draft new constitutions as swiftly as possible so that the United States could exist as it had before. But historians can only speculate that Lincoln desired a swift reunification, for his assassination in 1865 cut his plans for Reconstruction short.

Louisiana Drafts a New Constitution

White southerners in the Union-occupied state of Louisiana met in 1864—before the end of the Civil War—to draft a new constitution in accordance with the Ten-Percent Plan. The progressive delegates promised free public schooling, improvements to the labor system, and public works projects. They also abolished slavery in the state but refused to give the would-be freed slaves the right to vote. Although Lincoln approved of the new constitution, Congress rejected it and refused to acknowledge the state delegates who won in Louisiana in the election of 1864.

The Radical Republicans

Many leading Republicans in Congress feared that Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction was not harsh enough, believing that the South needed to be punished for causing the war. These Radical Republicans hoped to control the Reconstruction process, transform southern society, disband the planter aristocracy, redistribute land, develop industry, and guarantee civil liberties for former slaves. Although the Radical Republicans were the minority party in Congress, they managed to sway many moderates in the postwar years and came to dominate Congress in later sessions.

The Wade-Davis Bill

In the summer of 1864, the Radical Republicans passed the Wade-Davis Bill to counter Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan. The bill stated that a southern state could rejoin the Union only if 50 percent of its registered voters swore an “ironclad oath” of allegiance to the United States. The bill also established safeguards for black civil liberties but did not give blacks the right to vote.

President Lincoln feared that asking 50 percent of voters to take a loyalty oath would ruin any chance of ending the war swiftly. Moreover, 1864 was an election year, and he could not afford to have northern voters see him as an uncompromising radical. Because the Wade-Davis Bill was passed near the end of Congress’s session, Lincoln was able to pocket-veto it, effectively blocking the bill by refusing to sign it before Congress went into recess.

The Freedmen’s Bureau

The president and Congress disagreed not only about the best way to readmit southern states to the Union but also about the best way to redistribute southern land. Lincoln, for his part, authorized several of his wartime generals to resettle former slaves on confiscated lands. General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 set aside land in South Carolina and islands off the coast of Georgia for roughly 40,000 former slaves. Congress, meanwhile, created the Freedmen’s Bureau in early 1865 to distribute food and supplies, establish schools, and redistribute additional confiscated land to former slaves and poor whites. Anyone who pledged loyalty to the Union could lease forty acres of land from the bureau and then have the option to purchase them several years later.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was only slightly more successful than the pocket-vetoed Wade-Davis Bill. Most southerners regarded the bureau as a nuisance and a threat to their way of life during the postwar depression. The southern aristocracy saw the bureau as a northern attempt to redistribute their lands to former slaves and resisted the Freedmen’s Bureau from its inception. Plantation owners threatened their former slaves into selling their forty acres of land, and many bureau agents accepted bribes, turning a blind eye to abuses by former slave owners. Despite these failings, however, the Freedman’s Bureau did succeed in setting up schools in the South for nearly 250,000 free blacks.

Lincoln’s Assassination

At the end of the Civil War, in the spring of 1865, Lincoln and Congress were on the brink of a political showdown with their competing plans for Reconstruction. But on April 14, John Wilkes Booth, a popular stage actor from Maryland who was sympathetic to the secessionist South, shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. When Lincoln died the following day, Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, became president.

Andrew Johnson, Laissez-Faire, and States’ Rights

Johnson, a Democrat, preferred a stronger state government (in relation to the federal government) and believed in the doctrine of laissez- faire , which stated that the federal government should stay out of the economic and social affairs of its people. Even after the Civil War, Johnson believed that states’ rights took precedence over central authority, and he disapproved of legislation that affected the American economy. He rejected all Radical Republican attempts to dissolve the plantation system, reorganize the southern economy, and protect the civil rights of blacks.

Although Johnson disliked the southern planter elite, his actions suggest otherwise: he pardoned more people than any president before him, and most of those pardoned were wealthy southern landowners. Johnson also shared southern aristocrats’ racist point of view that former slaves should not receive the same rights as whites in the Union. Johnson opposed the Freedmen’s Bureau because he felt that targeting former slaves for special assistance would be detrimental to the South. He also believed the bureau was an example of the federal government assuming political power reserved to the states, which went against his pro–states’ rights ideology.

Like Lincoln, Johnson wanted to restore the Union in as little time as possible. While Congress was in recess, the president began implementing his plans, which became known as Presidential Reconstruction. He returned confiscated property to white southerners, issued hundreds of pardons to former Confederate officers and government officials, and undermined the Freedmen’s Bureau by ordering it to return all confiscated lands to white landowners. Johnson also appointed governors to supervise the drafting of new state constitutions and agreed to readmit each state provided it ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. Hoping that Reconstruction would be complete by the time Congress reconvened a few months later, he declared Reconstruction over at the end of 1865.

The Joint Committee on Reconstruction

Radical and moderate Republicans in Congress were furious that Johnson had organized his own Reconstruction efforts in the South without their consent. Johnson did not offer any security for former slaves, and his pardons allowed many of the same wealthy southern landowners who had held power before the war to regain control of the state governments. To challenge Presidential Reconstruction, Congress established the Joint Committee on Reconstruction in late 1865, and the committee began to devise stricter requirements for readmitting southern states.

The Northern Response

Ironically, the southern race riots and Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” tour convinced northerners that Congress was not being harsh enough toward the postwar South. Many northerners were troubled by the presidential pardons Johnson had handed out to Confederates, his decision to strip the Freedmen’s Bureau of its power, and the fact that blacks were essentially slaves again on white plantations. Moreover, many in the North believed that a president sympathetic to southern racists and secessionists could not properly reconstruct the South. As a result, Radical Republicans overwhelmingly beat their Democratic opponents in the elections of 1866, ending Presidential Reconstruction and ushering in the era of Radical Reconstruction.

Radical Reconstruction: 1867–1877

After sweeping the elections of 1866, the Radical Republicans gained almost complete control over policymaking in Congress. Along with their more moderate Republican allies, they gained control of the House of Representatives and the Senate and thus gained sufficient power to override any potential vetoes by President Andrew Johnson. This political ascension, which occurred in early 1867, marked the beginning of Radical Reconstruction (also known as Congressional Reconstruction).

The First and Second Reconstruction Acts

Congress began the task of Reconstruction by passing the First Reconstruction Act in March 1867. Also known as the Military Reconstruction Act or simply the Reconstruction Act, the bill reduced the secessionist states to little more than conquered territory, dividing them into five military districts, each governed by a Union general. Congress declared martial law in the territories, dispatching troops to keep the peace and protect former slaves.

Congress also declared that southern states needed to redraft their constitutions, ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, and provide suffrage to blacks in order to seek readmission into the Union. To further safeguard voting rights for former slaves, Republicans passed the Second Reconstruction Act, placing Union troops in charge of voter registration. Congress overrode two presidential vetoes from Johnson to pass the bills.

Reestablishing Order in the South

The murderous Memphis and New Orleans race riots of 1866 proved that Reconstruction needed to be declared and enforced, and the Military Reconstruction Act jump-started this process. Congress chose to send the military, creating “radical regimes” throughout the secessionist states. Radical Republicans hoped that by declaring martial law in the South and passing the Second Reconstruction Act, they would be able to create a Republican political base in the seceded states to facilitate their plans for Radical Reconstruction. Though most southern whites hated the “regimes” that Congress established, they proved successful in speeding up Reconstruction. Indeed, by 1870 all of the southern states had been readmitted to the Union.

Radical Reconstruction’s Effect on Blacks

Though Radical Reconstruction was an improvement on President Johnson’s laissez-faire Reconstructionism, it had its ups and downs. The daily lives of blacks and poor whites changed little. While Radicals in Congress successfully passed rights legislation, southerners all but ignored these laws. The newly formed southern governments established public schools, but they were still segregated and did not receive enough funding. Black literacy rates did improve, but marginally at best.

The Tenure of Office Act

In addition to the Reconstruction Acts, Congress also passed a series of bills in 1867 to limit President Johnson’s power, one of which was the Tenure of Office Act. The bill sought to protect prominent Republicans in the Johnson administration by forbidding their removal without congressional consent. Although the act applied to all officeholders whose appointment required congressional approval, Republicans were specifically aiming to keep Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in office, because Stanton was the Republicans’ conduit for controlling the U.S. military. Defiantly, Johnson ignored the act, fired Stanton in the summer of 1867 (while Congress was in recess), and replaced him with Union general Ulysses S. Grant. Afraid that Johnson would end Military Reconstruction in the South, Congress ordered him to reinstate Stanton when it reconvened in 1868. Johnson refused, but Grant resigned, and Congress put Edwin M. Stanton back in office over the president’s objections.

Resource M.

Resource O.

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/map_item.pl

(zoom in using electronic version)

Questions? Contact Project Director Audrey Shafer-Erickson

This site sponsored by Minnesota State University Moorhead

Ohio State nav bar

Ohio state navigation bar.

- BuckeyeLink

- Search Ohio State

United States History

(A ten-year-old newsie carrying a heavy load of newspapers in Washington, D.C. April 1912.)

Lesson Plans

1920s Consumer Culture

Espionage in the American Revolution

Indian Removal

The Loyalists

Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion

Native American History: John Smith and the Powhatan

- Lynchings

Women's Suffrage, 1890 - 1920 World War II: The Homefront

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Advanced Placement U.S. History Lessons

The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton December 26, 1776 by John Trumbull.

Wikimedia Commons

EDSITEment brings online humanities resources directly to the classroom through exemplary lesson plans and student activities. EDSITEment develops AP level lessons based on primary source documents that cover the most frequently taught topics and themes in American history. Many of these lessons were developed by teachers and scholars associated with the City University of New York and Ashland University.

Guiding Questions

What does it mean to form "a more perfect union"?

What makes American democracy unique?

What is the proper role of government in relation to the economy and civil liberties?

To what extent is the U.S. Constitution a living document?

To what extent have civil rights been established for all in the United States?

How have technology and innovation influenced culture, politics, and economics in U.S. history?

What role should the United States government and its citizens play in the world?

Magna Carta: Cornerstone of the U.S. Constitution —Magna Carta served to lay the foundation for the evolution of parliamentary government and subsequent declarations of rights in Great Britain and the United States. In attempting to establish checks on the king's powers, this document asserted the right of "due process" of law.

Images of the New World —How did the English picture the native peoples of America during the early phases of colonization of North America? This lesson plan enables students to interact with written and visual accounts of this critical formative period at the end of the 16th century, when the English view of the New World was being formulated, with consequences that we are still seeing today.

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Concepción and the Spanish Mission in the New World —In this Picturing America lesson, students explore the historical origins and organization of Spanish missions in the New World and discover the varied purposes these communities of faith served. Focusing on the daily life of Mission Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, the lesson asks students to relate the people of this community and their daily activities to the art and architecture of the mission.

Colonizing the Bay —This lesson focuses on John Winthrop’s historic "Model of Christian Charity" sermon which is often referred to by its "City on a Hill" metaphor. Through a close reading of this admittedly difficult text, students will learn how it illuminates the beliefs, goals, and programs of the Puritans. The sermon sought to inspire and to motivate the Puritans by pointing out the distance they had to travel between an ideal community and their real-world situation.

Mapping Colonial New England: Looking at the Landscape of New England —The lesson focuses on two 17th century maps of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to trace how the Puritans took possession of the region, built towns, and established families on the land. Students learn how these New England settlers interacted with the Native Americans, and how to gain information about those relationships from primary sources such as maps.

William Penn’s Peaceable Kingdom —By juxtaposing the different promotional tracts of William Penn and David Pastorius, students understand the ethnic diversity of Pennsylvania along with the "pull” factors of migration in the 17th century English colonies.

Understanding the Salem Witch Trials —In 1691, a group of girls from Salem, Massachusetts accused an Indian slave named Tituba of witchcraft, igniting a hunt for witches that left 19 men and women hanged, one man pressed to death, and over 150 more people in prison awaiting a trial. In this lesson, students explore the characteristics of the Puritan community in Salem, learn about the Salem Witchcraft Trials, and try to understand how and why this event occurred.

Religion in 18th-Century America —This curriculum unit, through the use of primary documents, introduces students to the First Great Awakening, as well as to the ways in which religious-based arguments were used both in support of and against the American Revolution.

- Lesson 1: The First Great Awakening

- Lesson 2: Religion and the Argument for American Independence

- Lesson 3: Religion and the Fight for American Independence

C ommon Sense : The Rhetoric of Popular Democracy —This lesson looks at Tom Paine and at some of the ideas presented in Common Sense , such as national unity, natural rights, the illegitimacy of the monarchy and of hereditary aristocracy, and the necessity for independence and the revolutionary struggle.

"An Expression of the American Mind”: Understanding the Declaration of Independence —This lesson plan looks at the major ideas in the Declaration of Independence, their origins, the Americans’ key grievances against the King and Parliament, their assertion of sovereignty, and the Declaration’s process of revision. Upon completion of the lesson, students will be familiar with the document’s origins, and the influences that produced Jefferson’s "expression of the American mind.”

The American War for Independence —The decision of Britain's North American colonies to rebel against the Mother Country was an extremely risky one. In this unit, consisting of three lesson plans, students learn about the diplomatic and military aspects of the American War for Independence.

- Lesson 1: The War in the North, 1775–1778

- Lesson 2: The War in the South, 1778–1781

- Lesson 3: Ending the War, 1783

Choosing Sides: The Native Americans' Role in the American Revolution —Native American groups had to choose the loyalist or patriot cause—or somehow maintain a neutral stance during the Revolutionary War. Students analyze maps, treaties, congressional records, first-hand accounts, and correspondence to determine the different roles assumed by Native Americans in the American Revolution and understand why the various groups formed the alliances they did.

What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader? —What combination of experience, strategy, and personal characteristics enabled Washington to succeed as a military leader? In this unit, students read the Continental Congress's resolutions granting powers to General Washington, and analyze some of Washington's wartime orders, dispatches, and correspondence in terms of his mission and the characteristics of a good general.

- Lesson 1: What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader? What Are the Qualities of a Good Military Leader?

- Lesson 2: What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader? Powers and Problems

- Lesson 3: What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader? Leadership in Victory and Defeat

- Lesson 4: What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader? Leadership in Victory: One Last Measure of the Man