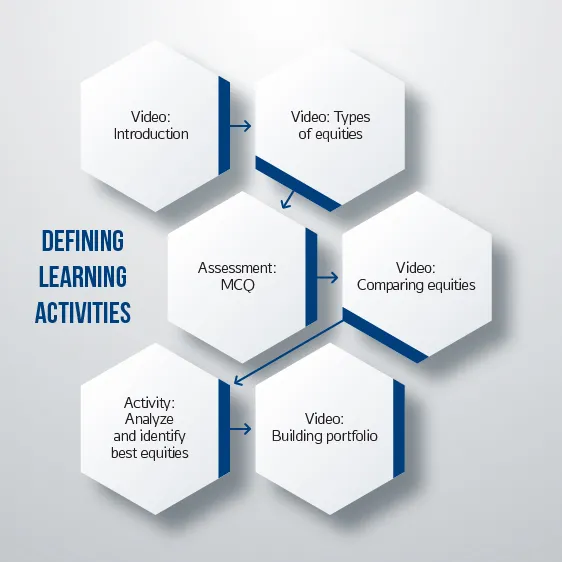

- Designing learning activities

- Teaching guidance

- Teaching practices

Learning activities need to align with their assessment, with the learning outcomes for the course/program overall, and with the students’ needs at this stage of their learning.

Planning learning activities

Lesson planning.

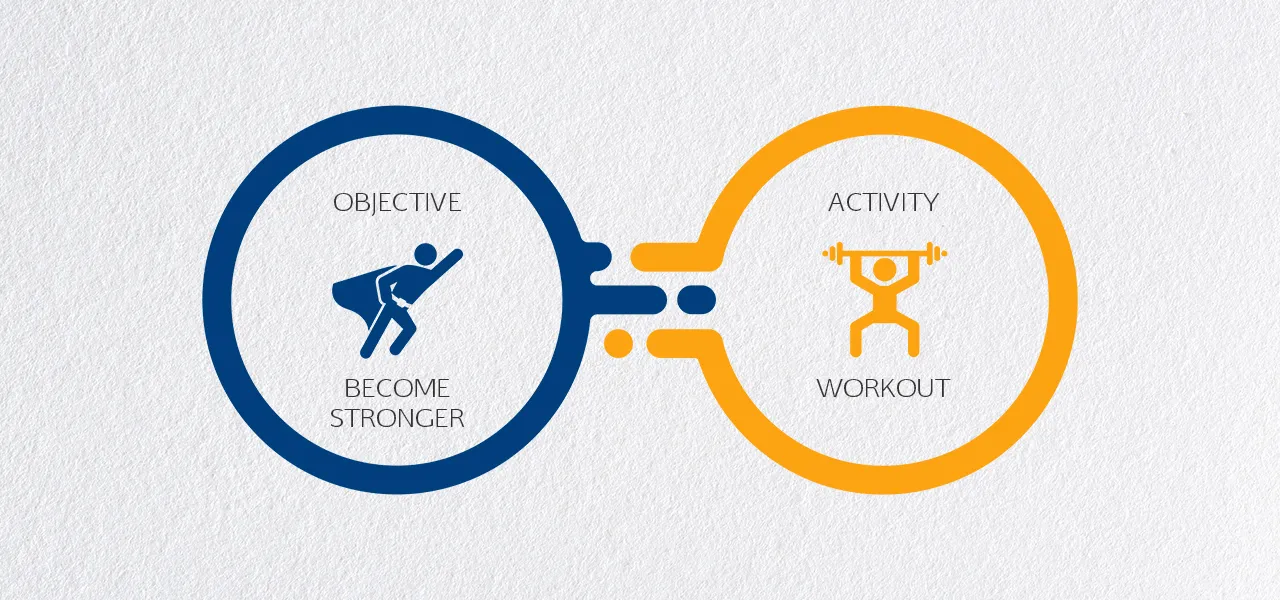

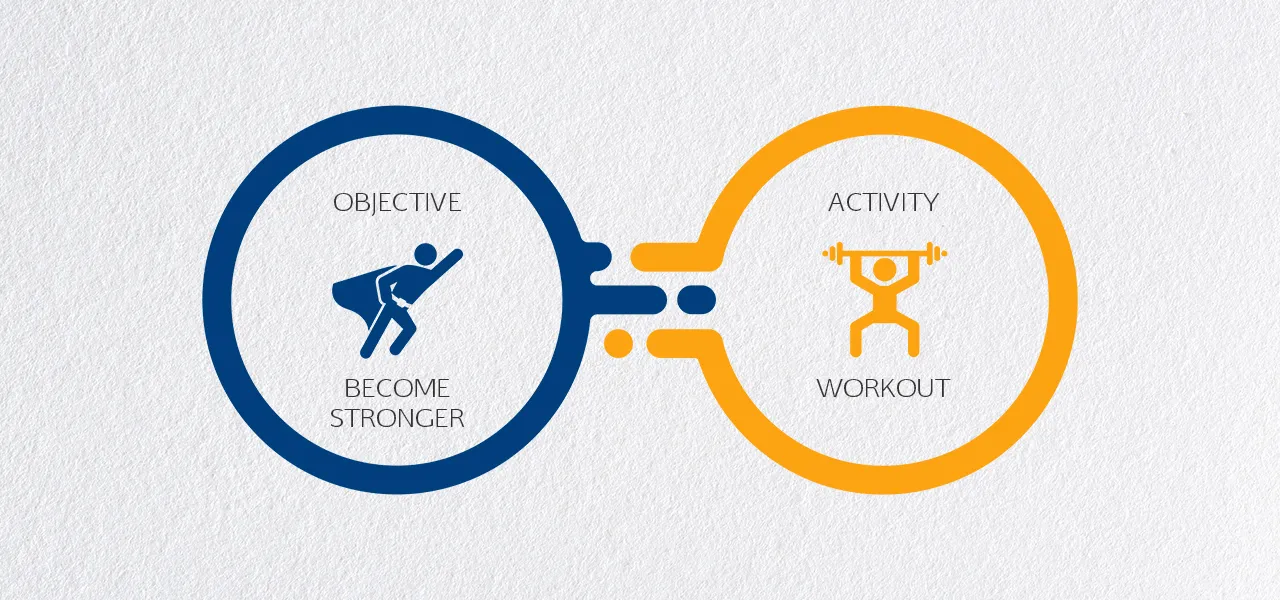

When planning learning activities, you should consider the types of activities that students will need to engage in to achieve and demonstrate the intended learning outcome/s. The activities should provide experiences that will enable students to engage, practice and gain feedback on specific outcome/s.

Some questions to think about when designing the learning activities:

- What would motivate your students to do these activities?

- What do students need to hear, read, or see to understand the topic?

- How can I engage students in the topic?

- What are some relevant real-life examples, analogies, or situations that can help students explore the topic?

- What will students need to do to practice and demonstrate knowledge of the topic?

Diana Laurillard (2012) classified learning activities into six types: acquisition, inquiry discussion, practice, collaboration and production.

Laurillard, Diana. (2012). Teaching as a design science . In Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group . Routledge.

Robert Gagne proposed a nine-step process called the events of instruction, which is useful for planning the sequence of your lesson.

Source: Lesson planning , Singapore Management University Centre for Teaching Excellence.

A lesson plan contains the details of what students need to learn and how it will be done effectively during a class.

A successful lesson:

- considers the social, physical, personal, and emotional needs of the student

- is aligned with the graduate attributes of the institute where the course is being taught

- has clear and well-defined learning outcomes

- has a sequence of learning activities that help students master the proposed learning outcomes

- provides students with the ability to be actively involved in the session

- promote creativity, critical thinking, communication and collaboration in the classroom

- includes formative assessments to check for student understanding

- enables educators to collect data about the learning process and learning experience of the students.

Before the class

- Identify graduate attributes

- Identify learning outcomes

- Plan the learning activities

- Plan to assess student understanding

- Create a realistic time plan

- Plan for lesson closure.

During the class

- Share the plan with students

- Effectively implement the plan

- Try to keep to the proposed time plan

- Try to collect data.

After the class

- Analyse collected data

- Reflect on what worked and what didn’t

- Redesign the lesson and the lesson plan.

- Planning for learning

- Active learning

- Inclusive practice

- Enhancing teaching

Ready to Teach Week

Twice a year, ITaLI puts together a program of online and in-person activities designed to help you prepare course materials for the upcoming semester.

Resources

- Developing learning outcomes/objectives

- Designing assessment

- Principles of learning

ITaLI offers personalised support services across various areas including planning and designing learning activities.

- Office of Curriculum, Assessment and Teaching Transformation >

- Teaching at UB >

- Course Development >

- Design Your Course >

Designing Activities

Determining learning experiences for students to develop skills, actively construct knowledge and deepen understanding.

On this page:

Importance of activities.

Activities are the experiences that allow students to achieve learning outcomes. These may consist of readings, lectures, group work, labs or projects to name a few. While situations and learning outcomes are unique, there are best practices that have proven to be more effective across contexts.

Active Learning

· improves critical thinking skills

· increases retention and transfer of new information

· increases motivation

· improves interpersonal skills

· decreases course failure

· provides practice and feedback

For further evidence please see active learning’s effectiveness.

Choosing Activities

Build in active learning.

On the teaching methods page you will find student-centered teaching methods that are inherently more active than lecturing.

Often, there are concerns about difficulty of implementing active learning in large courses or with limited support. We address several of these concerns here:

Aligning Activities

The chart below offers a variety of suggested activities that can support learning outcomes.

- Activity groupings are a starting point and many can be used in combination and in different categories. For example, small group work may have a discussion component built in.

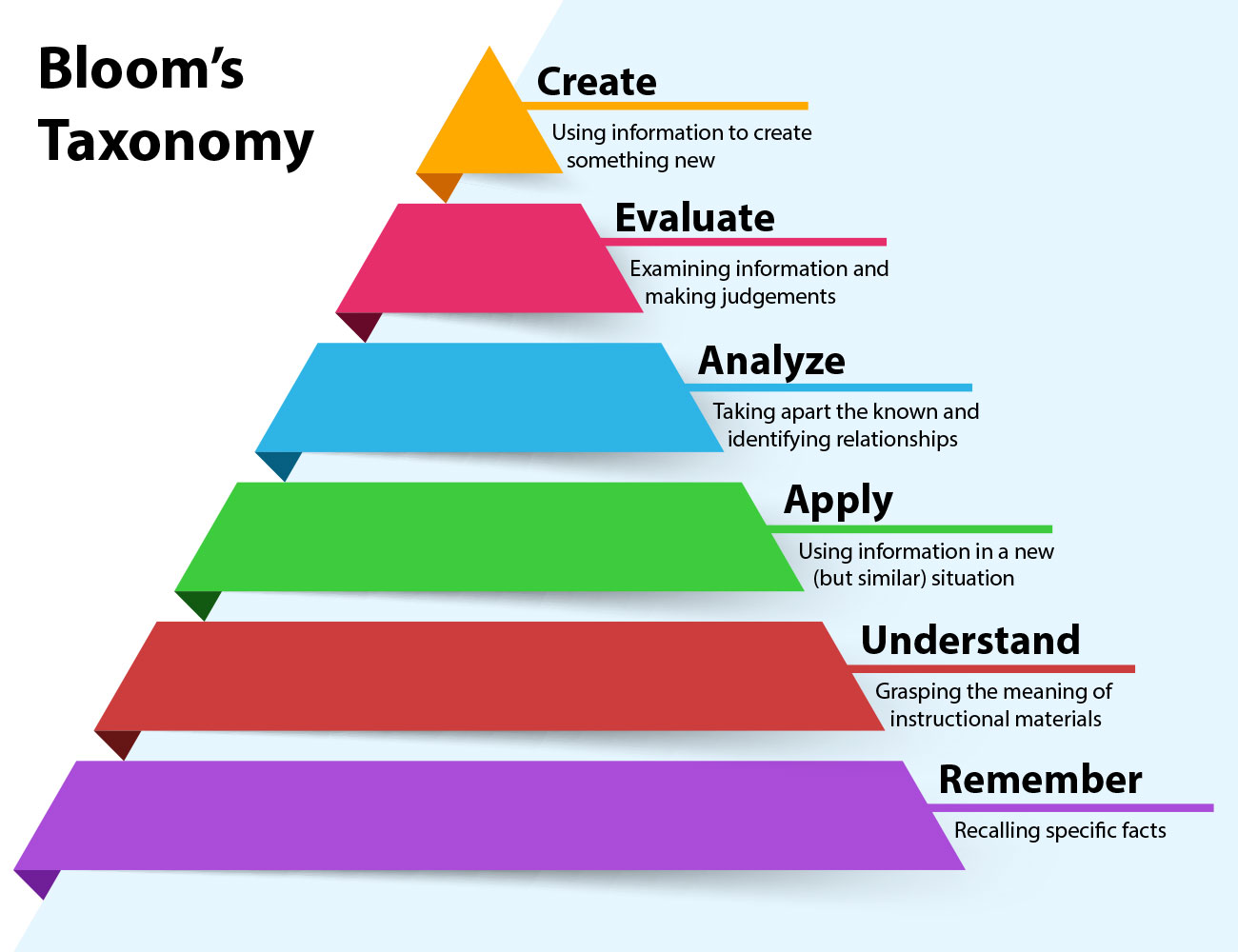

- Activities can be adapted to meet a variety of learning outcomes depending on what students do in the activity. To adapt an activity, first choose your learning outcome, and then choose an activity to help students achieve the learning outcome. To ensure alignment, refer to either Bloom’s Taxonomy or Fink’s Taxonomy to make sure the verb (what students are doing) matches the category your learning outcome is in. For example, a discussion board activity may ask students to create, analyze or explain their understanding of a topic.

Further information about these activities is in the Build section of course development.

Choose Your Activities

Use the Couse Design Template to determine the activities that will support your learning outcomes and assessments.

- A. The teaching methods you’ve chosen for each learning outcome.

- B. Your learning outcomes, and whether the activity will support student growth in this outcome. Refer to the verb lists for Bloom’s Taxonomy or Fink’s Taxonomy to ensure alignment.

- C. Choosing student-centered activities that promote active learning when appropriate.

After choosing your activities, you have now completed the design phase of course development. Next, you will begin building the elements of your course.

Additional resources

Overview of activities that encourage active learning.

Additional active learning techniques and examples to consider integrating into your course design.

Further active learning examples in higher education.

Active learning examples and directions.

SUNY OSCQR – Importance of activities to develop higher order thinking and encourage real world applications.

For further information about active learning, see the following readings.

- Ambrose, S. A. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bonwell, C. C., Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: creating excitement in the classroom. The George Washington University, ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education. Washington, D.C.: ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education. Retrieved from Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049

- Darby, F. and Lang, J. (2019) Small teaching online: apply learning science in online courses. Josey-Bass/Wiley.

- Lang, J. (2016). Small teaching: everyday lessons from the science of learning. Josey-Bass/Wiley.

- McGuire, S. (2015). Teach students how to learn: strategies you can incorporate into any course to improve student metacognition, study skills, and motivation. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Select your location

- North America English

- Brazil Português

- Latin America Español

Asia Pacific

- Australia English

- Germany Deutsch

- Spain Español

- United Kingdom English

- Benelux Dutch

- Italy Italiano

Demystifying Instructional Design: A Comprehensive Guide for Innovative Learning

Instructional design is a multifaceted approach to lesson planning that reshapes the teaching landscape, evolving it into an engaging, interactive experience rather than a one-way transmission of knowledge. Herein we show you how embarking on this informative journey will empower you to transform the educational experience you develop for your students, fostering an environment of active learning and genuine intellectual exploration. And our principles, strategies, and tips will set you up for success on your instructional design journey.

Unpacking instructional design: A gateway to enhanced learning

Instructional design, at its heart, is a systematic, user-focused process aimed at creating dynamic, engaging, and effective educational experiences. Its purpose is twofold: it seeks to simplify the process of learning, while ensuring knowledge retention through the development of clear and precise learning objectives.

Instructional design combines education, psychology, and communications to create optimal teaching plans. It evolved from traditional lesson planning under the influence of behavioural psychology.

The process doesn't just involve planning what information to present and how to deliver it, it's also about creating a tailored learning environment that fosters interaction and practical application. It's underpinned by the fundamental understanding of how people learn, and it employs a variety of instructional models to ensure educational content aligns with the learner's needs and the defined educational goals.

What sets instructional design apart is its iterative nature. It encourages constant analysis and adjustment to ensure optimal learning outcomes. This dynamism is what makes instructional design a powerful tool, not just in traditional education settings, but also in corporate training and personal learning pathways.

In essence, instructional design is the backbone of effective education, the catalyst that can transform a mundane lesson into an engaging, memorable learning journey.

Delineating curriculum and instructional design: What sets them apart?

The terms 'curriculum design' and 'instructional design' are often used interchangeably. However, these two concepts, while interrelated, are distinct in their approach and scope.

Curriculum design refers to the overarching plan for a course or educational program. It's the 'big picture' approach that outlines what will be taught, including course objectives, content topics, and the sequence of learning experiences. Curriculum design sets the framework and provides a roadmap to achieve desired educational outcomes.

On the other hand, instructional design focuses on how the curriculum will be taught. It's the methodological strategy that addresses the specifics of how to deliver the curriculum effectively. Instructional design encompasses the creation of instructional materials, learning activities, and assessment tasks, all structured to facilitate student learning and engagement.

In simpler terms, if curriculum design is about 'what' is to be learned, then instructional design is about 'how' it's learned.

The two work in tandem for a successful educational experience. A well-designed curriculum outlines the learning journey, and effective instructional design ensures that journey is engaging, accessible, and impactful for all learners.

Unlocking almost limitless potential: Instructional design principles and strategies

Keen to apply these innovative ideas in your teaching practice, but unsure where to start? A great place to begin is with the core instructional design principles and strategies that define this learner-centred approach to education.

Instructional design principles

The fundamental principles of instructional design are built on three key concepts: analysis, design, and evaluation.

Analysis involves understanding your learners' needs and defining clear, measurable objectives for what they should know or be able to do by the end of the course. This step is crucial because it lays the groundwork for designing the course content.

Design , the second principle, is the creation of the learning environment. Here, educators develop engaging and interactive content, incorporating a variety of teaching methods that cater to different learning styles. This part is all about structuring courses and lessons to give all learners the best chance of understanding and remembering the material being taught.

Lastly, Evaluation is the process of measuring the effectiveness of the instructional design. It's about giving feedback, assessing learners' progress, and making necessary adjustments to the course design.

Instructional design strategies

Implementing these principles might sound challenging, but don't fret! Here are some practical strategies to help you get started:

- Backwards design: Start with the end in mind. Define your learning outcomes first, then work backwards to design activities and assessments that support these outcomes.

- Chunking: Break down complex information into manageable 'chunks' to make it easier for learners to digest.

- Active learning: Create opportunities for learners to actively engage with the material, promoting higher-order thinking skills like analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

- Multimedia: Use a mix of text, images, audio, and video to cater to various learning styles and enrich the learning experience. If you're feeling particularly innovative and you have the resources available, consider including virtual reality and augmented reality experiences to really bring the materials to life.

- Feedback and revision: Regularly solicit feedback from learners and use it to continually refine and improve the course design.

Strategies specifically for online courses

In our ongoing work to support educators who are transitioning to an online or blended learning model, we’ve identified three commonalities all successful online courses share:

- Communication: Important announcements are easy to find, faculty can be contacted as needed, and feedback is given to personalise learning

- Empathy: Courses are designed to address the social and emotional needs of all learners by providing multiple opportunities for interaction

- Consistency: Courses are structured in a cohesive fashion to improve navigation and user experience

These fundamentals undoubtedly present educators with a balancing act, but together they create a foundation for both student and institutional success.

Kona Jones of Richland Community College calls the above “designing for kindness,” and considers it an important part of reframing coursework. “When students feel like their teacher cares about them as a person, as well as their success in the course, it creates a foundation of trust that promotes meaningful interactions and learning.” Plus, she adds, “It’s important to note that 'kindness' doesn’t mean 'easy.' You can still have an extremely rigorous course. Your course can still do some amazing things with students and expect phenomenal things out of them.”

Dr. Sean Nufer, Director of Teaching and Learning at TCS Education System suggests thinking about three B’s: Be human, be present, and be adaptable. “If you’re new to online teaching, think about what you do in your face-to-face settings to foster relationships between students and between you and students. Be sure you’re continuing to do that.”

Remember, instructional design isn't a one-size-fits-all approach. It's a flexible framework you can adapt and personalise to suit your specific teaching context and learners' needs. Embracing these principles and strategies could be your ticket to creating enriching, impactful learning experiences.

Harnessing instructional design for online courses: A pathway to vibrant eLearning and online learning experiences

As digital learning, and especially mobile learning, continues to transform all sectors of education, the role of instructional design in shaping effective online courses has become more crucial than ever. Let's explore how instructional design principles can be adapted to craft an engaging and effective online learning experience.

Two of the major challenges in online learning are to:

- Sustain student engagement when it's so easy to just turn off a device or 'alt tab' to YouTube or TikTok part way through a lesson

- Facilitate meaningful interactions when students aren't physically coming together to learn or work with their peers (and given that nearly half of all students value hands-on instruction )

Here's where the power of instructional design comes into play. It allows educators to leverage technology and devise innovative instructional strategies tailored to the digital learning environment, which can help overcome these barriers to effective and efficient online learning.

For starters, one of the instructional design principles that can greatly influence online learning is chunking information. In an online setting, long blocks of content can be overwhelming for students, and the longer a piece of content, the more likely students will be to succumb to the temptation of the many distractions around them. Breaking down content into manageable 'chunks' allows students to tell themselves 'it's ok, I only have to get through 2 more mins of lecture'. And it can be invaluable for students who don't have large chunks of time to devote to study — e.g. parents caring for young children who study during nap time. It also enhances comprehension and retention. Chunking can take many forms. For example, it might mean creating shorter, topic-specific video lessons instead of hour-long lectures, or designing modular learning activities that students can progress through at their own pace.

Interactive learning activities are another instructional design strategy that can foster engagement in online courses. This could be through the use of virtual breakout rooms for group discussions, interactive quizzes, or hands-on projects that students can complete independently. The key is to offer diverse ways for students to interact with the content, their peers, and the instructor, thus preventing the sense of isolation often associated with online learning.

Applying the principle of scaffolding is also instrumental in the online learning environment. Providing support structures and gradual release of responsibility allows students to build on prior knowledge and gain confidence in their learning journey. This could be achieved through guided tasks, collaborative projects, or constructive feedback that encourages student reflection and self-assessment.

It's equally important to use technology to personalise learning experiences. Instructional design for eLearning allows educators to tailor content delivery and assessment methods based on individual learning styles, preferences, and pace. Adaptive learning technologies, for instance, can modify content or tasks based on a student's performance, providing a more personalised and effective learning experience.

Lastly, good instructional design for online learning also embraces the principle of assessment for learning. Rather than using assessments solely as a measure of how much a student has learned, they can be employed as tools to actually guide (personalise) and improve learning. Assessments for learning might include regular formative assessments, peer-review activities, and opportunities for self-assessment, all geared towards providing feedback and informing future learning.

Let's consider an example. The University of Sydney has been experimenting with gamification in its online courses, using an instructional design strategy that involves game-based elements to motivate students. By incorporating elements such as points, badges, and leaderboards into their online learning environment, they've created a more engaging and interactive experience for students, demonstrating a unique application of instructional design in eLearning.

Instructional design provides a robust framework for creating meaningful and effective online learning experiences. By leveraging these principles and strategies, educators can craft online courses that not only transmit knowledge, but also foster engagement, promote active learning, prepare students for lifelong learning in the digital age, and equip students with the real-world skills they'll need to thrive in the workplace.

Charting new paths in learning with instructional design

In essence, instructional design is a crucial cornerstone in crafting powerful learning experiences, whether in traditional classroom settings or the digital sphere. It's a conduit for fostering deep engagement, promoting active participation, and personalising education to cater to diverse learning needs. By effectively applying instructional design strategies and principles, educators can revolutionise the teaching process. In doing so, they transform passive recipients of knowledge into active learners, setting the stage for a dynamic, interactive, and rewarding educational journey. So, is it time you embraced instructional design? Now is the time to unlock the door to a transformative learning environment through instructional design

Discover More Topics:

Related Content

Blog Articles

AI & Gamification: Unpacking the Student Perspective

Navigating Generative AI: Key Insights for This School Year

Measuring What Matters: Validity and Reliability in Assessment

Stay in the know..

How to design unforgettable class activities that help students learn better

Jonathan Sim shares teaching techniques designed to pique the emotions as a way to lodge key lessons more firmly in students’ memories

Jonathan Sim

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn?

A diy guide to starting your own journal, universities, ai and the common good, artificial intelligence and academic integrity: striking a balance, create an onboarding programme for neurodivergent students.

A problematic trend I notice when conversing with students is how many of them struggle to remember what they did in modules from previous semesters.

These discussions got me thinking about how to design learning activities that are unforgettable. Albert Einstein, among other figures credited with the quote, famously said that “education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school”. I want to ensure my students remember what they have learned from me, especially after all the hard work they put into the course.

So, I began experimenting with techniques that I used as a student. I had a very unorthodox method that was inspired by the comedian and counsellor Mark Gungor. He said that if you take an event and attach a strong emotion to it, that event will be seared into your memory for good. I applied this principle to my learning and created jokes for everything I wanted to remember. The funnier the joke, the stronger the emotion, and the better my memory of it.

Activities to reinforce learning

I thought it would be interesting to apply this approach to my teaching, regardless of whether it was through a quiz, a group project or a tutorial activity. So, every learning activity I created came packaged with its own scenario. The more fun the scenario, or the more shocking the conclusion, the better the students remembered the learning points and their efforts to achieve it.

I can tell how effective this approach has been when students consult me for help. Instead of explaining the concept, I can just invoke the name of the relevant learning activity. For example, I could say: “Do you remember how you found the spy in the ‘Who’s the spy?’ activity?” Immediately, students light up as they recall the concept or what they did.

Engaging the imagination

This is not the only ingredient for making learning activities unforgettable. The other reason I create fictitious scenarios and situate learning activities in them is that it provides fertile soil for the students’ imagination. This is particularly powerful when we invite them to role-play. There, students step out of their identities to be someone else – which enables them to have more fun learning.

This works well for group projects and discussions, where students within the group may differ in abilities and competencies. Fast learners may not feel a need to help their slower counterparts, and slower learners may be too embarrassed to seek help. In the context of the role-play, learners unite around a common mission to solve a problem and save the day.

This group mission prompts learners to emotionally invest themselves into the topic and to collaborate with each other in order to solve the problem. Given the chance to temporarily be someone else, students can put aside the stress that they often impose on themselves and have fun. As someone else, students are more inclined to engage in peer teaching and learning with each other. They can contribute their own insights and help one another out if they find themselves lost without additional prompting. This helps to reinforce the culture of collaboration that we try to foster in the module.

Difficulty and challenge

However, there is another issue. If we design activities meant for stronger students, the weaker students will feel lost and disengage from the class. If we design for the weaker students, stronger students will complete the task quickly on their own, become bored and disengage from the class.

To solve this conundrum, I found it effective to borrow two categories from game design: “difficulty” and “challenge”. A problem can have a low difficulty, or be easy, but be challenging or it can be difficult but not challenging at all.

A problem is difficult when it is hard to accomplish, and it depends very much on the learner’s ability to succeed. A sharp learner, for example, may not struggle much with a difficult problem, but a slower learner may feel lost and be unable to solve the problem unless someone steps in.

On the other hand, a problem is challenging when it requires effort rather than ability to solve it. Hence, a challenging-yet-easy problem can be solved by both fast and slower learners, and they will both need to work hard to find the solution since the answer is not immediately achievable.

With these categories in mind, we can design learning activities that have low difficulty but are still challenging enough for stronger students. This is achieved by providing just enough scaffolding and guiding resources, such as a Q&A resource page, that weaker students can refer to for help. This mirrors the way computer games leave clues and hints lying around.

For formative activities, I calibrate them to be easy yet challenging. In my course, this means that someone who has just learned Microsoft Excel will be able to solve the problem even with minimal experience. But it is challenging in a sense that the most experienced Excel user will not find the answer immediately and will have to work towards the answer, too.

For summative assessments, I will calibrate them to be just as challenging but with a higher difficulty level. There will be fewer scaffolds and guiding resources available. I typically pick out scenarios without clear answers, and so students have to talk within their groups to convince themselves of the right solutions.

Satisfaction and shock

The greater the challenge of the activity, the more we must ensure that students find the activity satisfying, as a reward for completing the challenge. Some activities are satisfying once the learner completes them. But sometimes the satisfaction may not be enough. To combat this, I usually test these activities with my teaching assistants, who are all undergraduates. I observe their behaviour and note their feedback for improvement.

Role-playing is useful in augmenting satisfaction levels. Depending on the assigned scenario, accomplishing the task can leave students feeling as if they’ve just solved one of humanity’s greatest dilemmas or that they have made the world a better place with their solution.

Sometimes, we can conclude the activity with a shocking revelation or a mind-blowing learning point that they least expect. For example, in one of my learning activities, students are tasked to develop an allocation algorithm to enrol children for a special learning programme with limited slots. Students feel incredibly accomplished finding the solution. However, when we get them to reflect on their solution, students soon discover that they had unintentionally prioritised children from more privileged backgrounds.

Like a plot twist in a movie, the students’ sense of accomplishment is almost immediately replaced with shock as they realise how their solution perpetuates inequality. This has a profound impact on them, making them more cautious about such issues when they carry out subsequent exercises.

These learning activities may be somewhat theatrical. But they help in generating strong emotions, which helps to sear the learning deep into students’ memories.

The result: an unforgettable learning experience. I stay in touch with many former students from two years ago and they still fondly remember various activities and learning points from the module. I believe this is an education that Einstein would be proud of.

Jonathan Y. H. Sim is an instructor in the department of philosophy at the National University of Singapore .

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn?

Global perspectives: navigating challenges in higher education across borders, how to help young women see themselves as coders, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, authentic assessment in higher education and the role of digital creative technologies, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

Design for Learning: Principles, Processes, and Praxis

(3 reviews)

Jason K. McDonald, Brigham Young University

Richard E. West, Brigham Young University

Copyright Year: 2021

Publisher: EdTech Books

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Ann Jerks, Associate Professor, Tidewater Community College on 1/9/24

The book covers instructional design practice in part one to include the role of a learning designer and how that can encompass many titles, responsibilities, and skills. Part one also includes the importance of problem framing and how the... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The book covers instructional design practice in part one to include the role of a learning designer and how that can encompass many titles, responsibilities, and skills. Part one also includes the importance of problem framing and how the learning designer role should go beyond the formula of creating a learning solution that will solve “x.” I really enjoy how the book provides multiple examples and scenarios of how to capture the actual problem(s) and what tools can help highlight the problem statement. Part two includes instructional design knowledge, learning theories, the instructional design process, and instructional activities and managing stakeholders, clients, and the project team. Including Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a very beneficial reminder that autonomous environments may not always produce the results and outcomes that are needed but it relies on the learner to be ready and willing to learn.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The content appears accurate with external links to additional resources that populate appropriately to the content and video media.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The content is relevant but also includes foundational learning theories and fundamentals that contribute to the longevity of learning design.

Clarity rating: 5

The text provides adequate context for any terminology used and describes the different titles and roles often lumped into the learning designer role. The content was easy to follow and navigate.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is consistent with terminology.

Modularity rating: 5

The text contains two main parts: Instructional Design Practice and Instructional Design Knowledge. Part one contains four subsections: Understanding, Exploring, Creating, and Evaluating that goes into a learning designer role and how it applies to practice. Part two contains four subsections: Sources of Design Knowledge, Instructional Design Processes, Designing Instructional Activities, and Design Relationships. Some chapters and subsections were longer than others but the content breakdown was easy to digest.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The topics are presented in a logical sequence. I felt that most resources on instructional design often have part two (instructional design knowledge) first instead of having the instructional design practice at the forefront.

Interface rating: 5

The text was very easy to navigate. I enjoyed having the ability to listen to the material instead of reading, however, some of the audio contained additional information that was distracting to the content such as a URL or page reference. The images and media enhanced the content. The reflective exercises and example forms and worksheets are very beneficial.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not encounter any grammatical errors or spelling concerns. Resources were cited appropriately.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The content includes designing for diverse learners and offers methods to recognize learner needs, potential considerations for various barriers to learning and possible solutions. Incorporating UDL helps highlight the importance and need for accessible learning.

I would love to have access to all the examples and worksheets all in one instead of having them at the end of the sections.

Reviewed by Blevins Samantha, Instructional Designer & Learning Architect, Radford University on 1/12/23

This book is a comprehensive look at the ever evolving field of instructional design, sometimes referred to as learning design. Both up to date practical implications, as well as theoretical underpinnings are included, giving a holistic view of... read more

This book is a comprehensive look at the ever evolving field of instructional design, sometimes referred to as learning design. Both up to date practical implications, as well as theoretical underpinnings are included, giving a holistic view of the field.

This text appears to be free from errors and bias.

This text is extremely relevant for those just entering the field of instructional design, but can also be used as a review of current practices by those currently working in the field. Relevant research for the field is included, and the content could be easily updated as relevant research is published and presented.

Clarity rating: 4

Clarity of the chapters varies throughout the text, but overall it is well written and easy to follow. The text includes many examples and case studies are included and can be easily used on a one-off basis or in a more comprehensive way.

Consistency rating: 4

The text is well organized and all chapters follow a similar format. Included are figures, case students, examples, tables, and videos in a way that enhance the text. However, reflective exercises are sometimes included in chapters, which would be even more helpful and valuable if they were included in every single chapter.

Modularity rating: 4

The text would serve as a holistic reading for a course/program, or could easily be used in sections as deemed appropriate. Some of the chapters are hefty, so it would take some time for an instructor to decide what chapters/sections would be appropriate for their own course.

The text is clear and easy to follow. Each section is thoughtfully organized into its respective theme.

The text is easy to navigate. Audio files of each chapter are also available, which is a great exampled of including universal design priciples.

I did not encounter any grammatical errors.

The text includes a diverse representation of the field, both in viewpoints and through the inclusion of a variety of races, genders and backgrounds.

Reviewed by Pamela Sullivan, Professor, James Madison University on 10/19/22

Design for Learning: Principles, Processes and Praxis is a comprehensive view of instructional design intended to both facilitate an introductory level of knowledge and to review the current practices of design for practitioners. These dual... read more

Design for Learning: Principles, Processes and Praxis is a comprehensive view of instructional design intended to both facilitate an introductory level of knowledge and to review the current practices of design for practitioners. These dual intentions result in an expansive review of knowledge and practices contained with a mammoth thirty-six chapter text. The authors/editors stated goals for utilizers of this text are to help complete a basic design project and to help create effective and engaging learning environments by exploring the current design thinking. While those dual purposes can and do lead to a great deal of information included within this text, each chapter stands on its own and it would be entirely possible to create a smaller set of readings customized to individual purposes from within this resource. The index and table of contents are helpful in organizing smaller groups of readings.

This text appears to be accurate, error-free, and unbiased.

Because this text is intended for beginning learners in the field or as a review of current practices, it does focus on content that both remains relevant and is timeless research inherent to the field, as well as more up-to-date practices and implementation of said research. The very focused chapters make it possible to update information on an on-going basis whilst continuing access to the literature reviews that wouldn’t change. These updates would be straightforward and easy to implement by simply updating the affected chapters.

The clarity of the text did vary between chapters but overall the text was very well-written. Although some chapters contained more technical information than others, jargon was avoided and the information was adequately explained for the beginning level readers comprising the stated audience for the text. Many examples and case studies were provided to illuminate the ideas presented

All of the chapters in this text are well-organized and follow a similar format. They include figures, tables, case studies, examples, and videos when appropriate to illustrate the ideas in the text. These additions to the text are quite helpful and useful. However, some of the chapters also contain reflective exercises to aid the reader in summarizing or applying the information and some chapters do not. This is unfortunate as those exercises are quite helpful for beginners to the field. Several chapters are also reprints, by permission, of work originally printed elsewhere, and these chapters are often formatted differently than others in the text. An instructor may need to carefully filter these chapters to ensure students follow the flow of information. Similarly, there are stylistic differences between chapters, expected in an edited work, but something an instructor might need to account for to students. One example of this is the included videos, some are embedded within the text while some are presented as a set of links within a table. As an instructor, noting this and including explicit instructions for your students as to whether and when to watch the videos might be important for a successful class experience.

This text lends itself to subdivision into smaller reading sections, in fact, with thirty-six chapters, it might be necessary. The text is grouped in sections with several chapters included in each section and a brief introduction at the beginning of each section. The section organization is well-thought out and described for the reader, however, the chapters contained within could benefit from reorganizing and better links between them. Information varied quite a bit across chapters, from general to highly specific, and it will take time as an instructor to sort through which chapters provide the best fit for class purposes. Conversely, some information is repeated several times across different chapters as well.

The topics in the text are presented in a clear, logical fashion. The sections are helpful in organizing the chapters into themes to support the overall goals of the text.

The text is easily navigable. Display features and items such as videos work as integrated into the text. Each chapter is available as an audio file as well, in an excellent example of universal design.

The text contains no grammatical errors.

This text includes chapters by a diverse set of authors and while the representation of a variety of races, genders, backgrounds in examples and videos also varies by chapter, across the entire text there is a diverse representation.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding 1. Becoming a Learning Designer 2. Designing for Diverse Learners 3. Conducting Research for Design 4. Determining Environmental and Contextual Needs 5. Conducting a Learner Analysis

- Exploring 6. Problem Framing 7. Task and Content Analysis 8. Documenting Instructional Design Decisions

- Creating 9. Generating Ideas 10. Instructional Strategies 11. Instructional Design Prototyping Strategies

- Evaluating 12. Design Critique 13. The Role of Design Judgment and Reflection in Instructional Design 14. Instructional Design Evaluation 15. Continuous Improvement of Instructional Materials

- Sources of Design Knowledge 16. Learning Theories 17. The Role of Theory in Instructional Design 18. Making Good Design Judgments via the Instructional Theory Framework 19. The Nature and Use of Precedent in Designing 20. Standards and Competencies for Instructional Design and Technology Professionals

- Instructional Design Processes 21. Design Thinking 22. Robert Gagné and the Systematic Design of Instruction 23. Designing Instruction for Complex Learning 24. Curriculum Design Processes 25. Agile Design Processes and Project Management

- Designing Instructional Activities 26. Designing Technology-Enhanced Learning Experiences 27. Designing Instructional Text 28. Audio and Video Production for Instructional Design Professionals 29. Using Visual and Graphic Elements While Designing Instructional Activities 30. Simulations and Games 31. Designing Informal Learning Environments 32. The Design of Holistic Learning Environments 33. Measuring Student Learning

- Design Relationships 34. Working With Stakeholders and Clients 35. Leading Project Teams 36. Implementation and Instructional Design

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Our purpose in this book is twofold. First, we introduce the basic skill set and knowledge base used by practicing instructional designers. We do this through chapters contributed by experts in the field who have either academic, research-based backgrounds, or practical, on-the-job experience (or both). Our goal is that students in introductory instructional design courses will be able to use this book as a guide for completing a basic instructional design project. We also hope the book is useful as a ready resource for more advanced students or others seeking to develop their instructional design knowledge and skills.

About the Contributors

Dr. Jason K. McDonald is an Associate Professor of Instructional Psychology & Technology at Brigham Young University and the program coordinator of the university’s Design Thinking minor. He brings twenty years of experience in industry and academia, with a career spanning a wide-variety of roles connected to instructional design: face-to-face training; faculty development; corporate eLearning; story development for instructional films; and museum/exhibit design. He gained this experience as a university instructional designer; an executive for a large, international non-profit; a digital product director for a publishing company; and as an independent consultant.

Dr. McDonald's research focuses around advancing design practice and design education. He studies design as an expression of certain types of relationships with others and with the world, how designers experience rich and authentic ways of being human, the contingent and changeable nature of design, and design as a human accomplishment (meaning how design is not a natural process but is created by designers and so is open to continually being recreated by designers).

At BYU, Dr. McDonald has taught courses in instructional design, media and culture change, project management, learning psychology, and design theory.

Dr. Richard E. West is an associate professor of Instructional Psychology and Technology at Brigham Young University. He teaches courses in instructional design, academic writing, qualitative research methods, program/product evaluation, psychology, creativity and innovation, technology integration skills for preservice teachers, and the foundations of the field of learning and instructional design technology.

Dr. West’s research focuses on developing educational institutions that support 21st century learning. This includes teaching interdisciplinary and collaborative creativity and design thinking skills, personalizing learning through open badges, increasing access through open education, and developing social learning communities in online and blended environments. He has published over 90 articles, co-authoring with over 80 different graduate and undergraduate students, and received scholarship awards from the American Educational Research Association, Association for Educational Communications and Technology, and Brigham Young University.

Contribute to this Page

- Campus Maps

- Faculties & Schools

Now searching for:

- Home

- Courses

- Learning activity design

- Constructive alignment

- First Nations education

- Digital media services support

- Educational design support

- Delivery

- Evaluation

- Assessments

- Teaching

- Learning technology

- Professional learning

- Framework and policy

- Strategic projects

- About and contacts

- Help and resources

Learning activity design

Learning activities need to be aligned with learning outcomes and assessment to provide students with opportunities to develop relevant and appropriate skills, knowledge, values, and attitudes.

The importance of learning activities

Learning activities play an important role in student learning and engagement. Students benefit from the opportunity to reflect upon their learning and to ascertain progression towards outcomes.

The teacher's fundamental task is to get students to engage in learning activities that are likely to result in achieving [the intended learning] outcomes. It is helpful to remember that what the student does is actually more important than what the teacher does. (Schuell, 1986, p.429)

Learning activities should:

- align to outcomes and assessment

- engage students in active learning

- facilitate the practice of core skills prior to assessment

- provide feedback on student progress towards outcomes

- be accessible for all students.

Types of learning activities

Diana Laurillard's Conversational Framework (2012) identified six types of learning activities.

Source: Optimising blended and online learning , Diana Laurillard Professor of Learning with Digital Technology, UCL Knowledge Lab

There are different techniques to embed learning. Your strategies might be different depending on what you're teaching or learner preferences.

Acquisition

Learning through acquisition is when teachers engage students with theories, concepts, and ideas.

For example:

- reading books, journal articles, or websites

- attending face-to-face presentations, or synchronous lectures/tutorials

- watching videos, demonstrations, animations, or

- listening to podcasts or lecture recordings.

Students are supported and guided by teachers to explore and compare theories, concepts, and ideas to develop their own conceptual understanding.

- research concepts, theories, or events

- explore and analyse data

- compare different ideas to critique practice

- formulate solutions to problems

- fieldwork, work-integrated learning, and placements

Students use their emerging conceptual understanding to put theory into practice, and utilise feedback to amend their actions and understanding.

- test solutions to problems

- simulations

Students produce an output to represent their conceptual understanding. The intention of production is to consolidate learning through the process of producing an output.

- ePortfolios

- digital posters

- video and audio presentations

- written texts

- infographics and concept maps

- blogs, journals, and wikis

Students engage with their peers and teacher to articulate and share their ideas and questions. Through discussion, students are able to enhance their conceptual understanding and generate more questions and ideas.

- think-pair-share

- in-class or online synchronous discussions

- online asynchronous discussions

Collaboration

Students work with their peers to address a problem or to complete an output. Collaboration often involves discussion and production.

- jigsaw group activities

- project-based work

- team problem solving

- collaborative problem solving

- peer feedback

Laurillard, Diana. (2012). Teaching as a design science . In Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group . Routledge.

What are the six learning types?

For more information on this framework and the different types of learning activities, please watch the following video:

Learning activity ideas

For some great ideas and suggested digital learning activities, see the NSW Department of Education website.

Explore learning activities

Planning for teaching

After you have designed your learning activities, it's time to start planning for your teaching.

Start planning

- Utility Menu

The Making of a Learning Designer: Part 1

by: Bonnie Anderson

One of the questions we ask prospective learning designers is, “If you get this job, how will you describe your new role to your friends and family?” The way a candidate answers this question can reveal much about their understanding of and approach to the work of learning design.

What does a learning designer do, exactly? What makes this role distinct from that of an instructor, program developer, learning technologist, or media producer? How does a person become a dedicated learning designer….and why might they want to do so? In this series of posts, I will explore these questions with the aim of helping both prospective designers and those who collaborate with designers to understand the work, approach, and skills of those in this role. Specifically, I will look at the most common roles and responsibilities of learning designers ( also known as instructional designers ), the attributes and competencies of effective learning designers, the art and science of learning design as a collaborative process, and developmental paths toward becoming a learning designer.

Four Domains

Learning design is an endlessly complex and fascinating field spanning a range of organizational contexts, including corporate, academic, medical, and social. Within academia alone, designers may work in public, private, profit and not for profit organizations from pre-K through postsecondary and graduate institutions. To dig even deeper, within higher education, a learning designer may be involved in campus-based programming, online and blended programming, and/or professional development programming for the wider community. Within any of these scopes of work, the designer is typically responsible for contributions requiring a wide range of skill sets.

Instructional Design in Higher Education , a new report by Intentional Futures and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, was written to help “institutions gain a better understanding about how instructional designers are utilized and their potential impact on student success” (page 2). The report describes four key domains of a designer’s work: Design, Manage, Train, and Support.

Based on my ten+ years in the field of learning design, and with a particular focus on the creation of online and blended educational programs, I would consider the proposed breakdown to be an accurate snapshot of the work, with two caveats. First, I would add “Develop” to the Design domain, and “Evaluate” to the Support domain. Learning Designers are rarely called upon to conceptualize a learning experience without also developing it, either in prototype or final form. This may include the development of multimedia resources, interactive exercises, text-based materials, and/or, for an online experience, the course site itself. Similarly, online learning experiences benefit greatly from iterative evaluation and improvement processes, so we should not overlook Evaluation as a critical component of the work.

Into Practice: Two Examples

To illustrate how a Learning Designer performs these responsibilities (Design and Develop, Manage, Train, and Support and Evaluate), I will use two projects recently completed by the TLL in partnership with Programs in Professional Education (PPE).

The first example is a short, lightly facilitated, asynchronous learning experience designed for teachers and educational leaders looking to increase the inclusivity and accessibility of their instruction. “ Ensuring Success for All: Tools and Practices for Inclusive Schools ” is a 10-day module developed with Professor Tom Hehir to extend the reach of the research-based principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Two of the learning designers in the TLL, Andrea Flores and Joanna Huang, worked with Dr. Hehir, a teaching fellow, and staff at PPE to create and launch this module. Their work included design and development, management, training, and support as follows:

Design and Develop Andrea and Joanna watched video of Dr. Hehir describing UDL principles and examples from a recent webinar offered by HGSE. They considered how this content may be offered as an asynchronous learning experience with opportunities for participants to dive more deeply into the material. This work involved:

- Identifying learning goals, activities, and assessments for consideration and refinement by the teaching team.

- Dividing the material into strategically-sized “chunks” according to best practices in online learning design (see multimedia learning theory , attention span of the online learner ).

- Creating orientation materials to usher participants into what may be to them a new learning modality.

With an understanding of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, ensure the course is accessible to a diverse range of learners across various abilities, genders, races, cultures, and other dimensions impacting the experience of our learners.

- Using graphic design skills and tools, developing a visual template and navigational structure for the experience in the learning platform (Canvas).

- Using programming skills and tools, building out the content pages, discussions, quizzes, and other resources in the learning platform.

Using user experience (UX) design skills and tools, ensuring language, flow and functionality of all aspects of the experience in the learning platform are as clean, intuitive and engaging as possible.

- Create a project plan and timeline for faculty, PPE, TLL, and IT to follow to produce the module by the designated launch date.

- Function as project manager within the TLL to ensure coordination of media team, technologists, and IT resources based on timeline.

- Develop procedures for, and ensure that reviews are conducted and changes implemented for, usability, accessibility, quality, and technical functionality.

Advocate for the learner and the learning experience as the primary drivers of all decisions.

Train identified facilitator(s) in the use of the learning platform (Canvas) as well as best practices in facilitating online learning. For this project this work was done by PPE, though the TLL is working on guidelines for the effective facilitation of online discussions (and learning in general).

- Support and Evaluate

- During the run of this module and future experiences, the TLL works closely with IT and PPE to iron out any technical or teaching and learning challenges that come up.

- Each short-form module benefits from the lessons learned from the prior offering. As the UDL module is the second one we have developed, the design reflects improvements identified by learners in the first module. This iterative improvement will continue with each new module.

The second example is a semester long, highly facilitated, online learning experience designed for current educational leaders looking to further their development. The Certificate in Advanced Education Leadership (CAEL) features four semester-long modules, the second of which, Managing Evidence , is running as we speak.

- Design and Develop I helped the team consider ways in which learning goals that are traditionally met in campus-based programs might also be accomplished online, and to understand the unique affordances of the online format. This project required all of the design work described in the example above, as well as:

- The development of interactive exercises for use within the course. These include use of rapid development courseware (Articulate Storyline, Engage, and Quizmaker) as well as an online tool for multimedia discussions (VoiceThread).

- Working with the team (including T127 Practicum student, Dustin Hilt) to build in meaningful opportunities for learners to connect with one another and create a vibrant learning community throughout the learning experience (see connectivism , discussion strategies , and self-determination theory ).

I wrote about other principles impacting the design of CAEL modules in this blog post .

Manage This project required all of the management work described in the example above, as well as the creation of custom processes and tools such as an asset tracker, a cross-departmental timeline of responsibilities, and a unique edit decision list (EDL) mechanism for use with the TLL’s media team.

Train Brandon and I contribute to the Online Learning Facilitator (OLF) Handbook, a guide for the people responsible for facilitating the learning experience for up to fifteen people each. Brandon’s team also created videos and documentation for using various aspects of the course site and participated in a live training for the OLFs as well as the first Live Online for learners, orienting them to the learning platform.

Support and Evaluate As with the example above, the TLL works closely with IT and PPE to iron out any technical or teaching and learning challenges that come up. We also collaborate with the teaching and delivery teams to design the weekly learning evaluations, the results of which are discussed in our weekly “Learning Loop” meetings. Here, emerging questions and opportunities for improvement are addressed in thoughtful and strategic ways so that our own learning does not end.

How can one person be a creative designer and developer of learning experiences, a detailed project manager, a helpful trainer, and a service-oriented support person? In a future post, I will explore the attributes of effective learning designers and the steps one might take to prepare for work in this field.

Call to action/comments from current learning designers : What do you think of this breakdown of the responsibilities encompassed in your work? Do they accurately capture your role? What would you add or change?

View the discussion thread.

- Organization (6)

- Project (8)

- Teaching and Learning (4)

- Technology (4)

Blog posts by month

- February 2023 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (2)

- October 2020 (2)

- March 2017 (1)

Short courses - staff resources

Designing learning activities

Enabling learners to achieve their learning outcomes through engagement with meaningful learning activities.

Once the course aims and learning outcomes have been established, you should plan and design the learning activities and assessments that will enable students to achieve them. The order in which you do this is not usually important, provided they align with the course aims and learning outcomes.

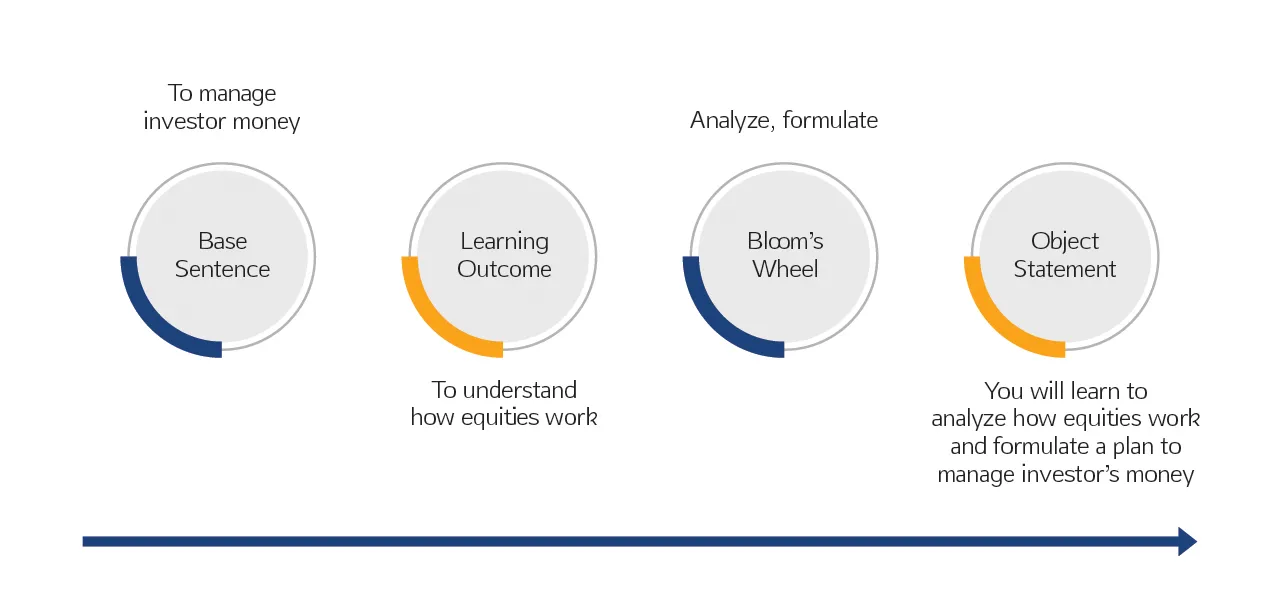

Aligning the elements of the course

As we have seen, learning outcomes must include action verbs that can be measured. From a learning design perspective, this implies:

The selection of activities should be driven by the learning outcomes.

Assessments should target the level of proficiency as stated in the outcomes.

For example, if a learning outcome includes a verb such as argue, which is at the ‘evaluation’ level in Bloom’s Taxonomy , learners should engage in activities that will enable them to reach and demonstrate that level of competency.

Designing learning activities with the ABC method

When designing learning activities, it is useful to reflect on the learning process. At UCL we utilise the ABC Learning Design method , based on the Conversational Framework (Laurillard, 2002), and the six learning types :

Acquisition

Discussion , investigation , collaboration .

- Practice, and

- Production.

The learning types have proven to be an effective course design tool because they involve creating flexible learning paths and course narratives centred around how people actually learn. Once a sequence of activities has been established, the tools or technologies that best facilitate the activities and the learners’ path towards proficiency can then be assessed.

When designing your short course, it is helpful to frame your thinking using these types.

This type tends to focus on content and what learners do when they read, listen, and watch. In this way learners acquire new concepts, models, vocabulary, models, and methodologies. Acquisition should be reflective as learners align new ideas to their existing knowledge.

Acquisitional learning activities include making articles and books available, delivering presentations and lectures, and having learners listen to or watch videos, podcasts, and animations.

Discussion activities require a learner to articulate their ideas and questions as well as challenging and responding to those from their tutor and peers.

Discursive learning activities include in-person seminars or structured online tasks within asynchronous discussion fora, and synchronous classroom tools such as debates and role plays.

Investigative activities encourage learners to take an active and exploratory approach to learning, searching for and evaluating a range of new information and ideas.

Either online or offline, students are guided to analyse, compare, and critique the texts, data, documents and resources within the concepts and ideas being taught.

Collaboration asks learners to work together in small groups to achieve a common project goal. It is about taking part in the process of knowledge building itself, and may build on acquisition, discussion, or investigation activities.

Collaborative learning activities might include paired or small group projects taking place online or on campus, with plenty of reflection and discussion to produce a joint output.

Practice activities enable knowledge to be applied in context, giving learners the opportunity to try out something they have learned and receive feedback on, whether via self-reflection, from peers, their tutor, or from tools and activity outcomes.

Practice tasks can include lab work, field trips, placements, and practice-based projects. Online, learners may engage with videos of methods, simulations, and sample datasets. Online quizzes can be used to test application and understanding.

Production

Production focuses on how a teacher motivates learners to consolidate what they have learned by articulating their current conceptual understanding and reflecting upon how they used it in practice. Production is usually associated with formative and summative assessment.

Activities for this type can include essays, designs, performances, and videos, made available both in-person and online.

If you are working with a Learning Designer, you will be fully supported in your understanding of and engagement with these learning types. In the next section we will think more about the two final types, practice and production, and their relation to assessment in the short course context.

Example of a short course learning activity

Here is an example learning activity from a course about Transfer Medicine :

Spot The Mistakes!

Watch this video of a transfer team simulating a chaotic packaging sequence. Consider what areas could have been improved before reading on.

We’re sure you have spotted a whole load of mistakes in the video.

In the comments section below we invite you to explore:

- Solutions. Give us your way of improving the mistake listed in the most recent comment.

- Mistakes. List a different mistake you’ve seen in the video for the next commenter to improve on!

This activity involves two learning types: acquisition and discussion. Learners engage in the acquisitional learning type when watching the video and discussion type when writing comments and responding to those of others afterwards. Crucially, however, both sections contain clear guidance that encourages targeted reflection during the acquisition stage and structured engagement during the discussion stage.

Further information

Full information about ABC learning design, including videos and self-directed resources, can be found on its website .

Designing Learning Activities and Instructional Systems

- First Online: 28 February 2019

Cite this chapter

- Ronghuai Huang 9 ,

- J. Michael Spector 10 &

- Junfeng Yang 11

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Educational Technology ((LNET))

168k Accesses

2 Citations

In this chapter, the focus will be first on some general principles of learning activities design and then on principles to consider when designing instructional systems.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. In P. W. Airasian, K. A. Cruikshank, R. E. Mayer, P. R. Pintrich, J. Raths, & M. C. Wittrock (Eds.), A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . New York: Longman.

Google Scholar

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). New York: Academic Press.

Beetham. H, (2004) Review: developing e-learning Models for the JISC Practitioner Communities. Retrieved from http://www.ibrarian.net/navon/paper/Review__developing_e_Learning_Models_for_the_JISC.pdf?paperid=1725131 .

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals; Handbook I: Cognitive domain. In M. D. Engelhart, E. J. Furst, W. H. Hill, & D. R. Krathwohl (Eds.), Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals; Handbook I: Cognitive domain . New York: David McKay.

Branch, R. M. (2009). Instructional design: The ADDIE approach . New York: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive Load Theory and the Format of Instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8 (4), 293–332.

Article Google Scholar

Dave, R. H. (1970). Psychomotor levels. In R. J. Armstrong (Ed.), Developing and writing behavioral objectives (pp. 20–21). Tucson: AZ: Educational Innovators Press.

Davydov, V. (1988). Problems of developmental teaching. Soviet Education, 30 (10), 3–41.

Gagné, R. M. (1987). Instructional technology foundations . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hedegaard, M., & Lompscher, J. (1999). Introduction. In M. Hedegaard & J. Lompscher (Eds.), Learning activity and development (pp. 10–21). Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Huang R., Kinshuk, & Spector J. M. (2013). Reshaping learning: New frontiers of educational research . Berlin: Springer.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom’s taxonomy: an overview. Theory into Practice, 41 (4), 212–218.

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals (Affective domain, Vol. Handbook II). New York: David McKay.

Mayer, R. E. (1992). Cognition and instruction: Their historic meeting within educational psychology. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84 (4), 405–412.

Mayer, R. E. (2003). Elements of a science of e-learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 29 (3), 297–313.

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2010). Applying the science of learning to medical education. Medical Education, 44, 543–549.

Merrill, M. D., Drake, L., Lacy, M. J., Pratt, J., & ID2_Research_Group. (1996). Reclaiming instructional design. Educational Technology, 36 (5), 5–7.

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., & Kemp, J. E. (2010). Designing effective instruction (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes . New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Shuell, T. J. (1986). Cognitive conceptions of learning. Review of Educational Research, 56, 411–436.

Simpson, E. J. (1966). The classification of educational objectives: Psychomotor domain. Illinois. Journal of Home Economics., 10 (4), 110–144.

Spector, J. M. (2015). The Encyclopedia of educational technology . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Spector, J. M. (2016). Foundations of educational technology: integrative approaches and interdisciplinary perspectives . New York: Routledge.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science., 12 (2), 257–285.

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J., & Paas, F. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10 (3), 251–296.

Tennyson, R. D. (1993). A framework for automating instructional design. In J. M. Spector, M. C. Polson, & D. J. Muraida (Eds.), Automating instructional design: Concepts and issues (pp. 191–214). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (1997). Training complex cognitive skills: A four-component instructional design model for technical training . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Kirschner, P. A. (2007). Ten steps to complex learning: A systematic approach to four-component instructional design . Mahwah, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Clark, R. E., & de Croock, M. B. M. (2002). Blueprints for complex learning: The 4C/ID-model. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50 (2), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02504993 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Educational Technology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Ronghuai Huang

University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

J. Michael Spector

School of Education, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Junfeng Yang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ronghuai Huang .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Huang, R., Spector, J.M., Yang, J. (2019). Designing Learning Activities and Instructional Systems. In: Educational Technology. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6643-7_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6643-7_8

Published : 28 February 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-6642-0

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-6643-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Enroll & Pay

Campuses | Buses | Parking

Information Technology | Jobs at KU

Tuition | Bill Payments | Scholarship Search Financial Aid | Loans | Beak 'em Bucks

People Search

Search class sections | Online courses

Libraries | Hours & locations | Ask

Advising | Catalog | Tutors Writing Center | Math help room Finals Schedule | GPA Calculator

- Social Media

Search form

- Step-by-step

- Step 3: Instructional activities

- Teaching in socially distanced classrooms

- Models for Alternating Cohort Courses

- Options for Online Instructional Activities

- Choosing between synchronous versus asynchronous methods

- Capturing video and audio

Step 3: Plan your instructional activities

Once you have made headway in determining what assessments will work in your flexible or online course, think about how you will design your instructional activities (or your students' learning activities) to give students the knowledge and skills they will need to perform well. Stay centered on the skills and concepts you want students to acquire through those activities, and how they will help students suceed on the assessments.

Begin by reflecting on:

- What knowledge and skills will students need for successful performance on my assessments?

- What types of practice and feedback would promote students’ learning of the needed knowlege and skills?

- Is there anything you need to break into steps, clarify, or “uncover?

Once you have identified the types of practice and learning experiences you would like to implement, you will need to address how to implement them online and in flexible ways. As suggested in the introductory section of this guidebook , design each course element for an online environment , even though you may plan to implement that component in person. That way, you already have a way for students who miss class for a day or a larger part of a semester to complete the work. Use online activities to "book-end" the in-person activities so that students who do have to miss class have a ready-made way of being involved in the discussion. The upfront time to plan in this way will save you time and grief later in the semester. It is almost always easier to transfer online course material to a physical class session than to transfer classroom material online, especially at the last minute. The goal is to design one, flexible class, rather than two classes offered simultaneously!

General considerations

Reenvisioning learning activities for online.

Online teaching requires a different mindset from classroom teaching, but done well, it can be just as effective and engaging as in-person teaching. It involves thinking about teaching and learning in a slightly different way.

- Online options: This page provides suggestions about a variety of learning activities that can be carried out online and give students practice using and applying concepts and skills.

- Group activities: And this page provides guidance for implementing and scaffolding online group activities .

How do I decide whether to use real-time online activities?

This page here describes the pros and cons of synchronous and asynchronous online activties, and provides recommendations for deciding the best balance for your course.

Deciding what to do with in-person time

Planning class time will involve thinking through the sorts of learning activities that can be carried out in a physically distanced classroom and the relationship between face-to-face activities and the learning activities completed online.

What sorts of learning activities will work best in a physically distanced classroom?

With students in masks and physically distanced from one another, it may be difficult to envision how to make use of your in-person time with students. Here is some information from a simulation of socially distanced classrooms, as part of a video shoot. This video on the Protect KU website illustrates what campus activity and student and instructor movement in and out of classrooms will look like this fall.

We are currently running experiments of specific instructional practices in classrooms. There are ways to use the structure and immediacy of class time even under these conditons. Based on these principles and the initial simulation, consider the following types of activities:

- Small group discussion