Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Economic freedom, inclusive growth, and financial development: A heterogeneous panel analysis of developing countries

Contributed equally to this work with: Zhengrong Yang, Prince Asare Vitenu-Sackey

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation

Affiliation School of Finance and Business, Zhenjiang College, Zhenjiang, China

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Economics, Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Roles Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft

¶ ‡ LH and YT also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliation Pamplin School of Business Administration, University of Portland, Portland, OR, United States of America

Roles Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Business School, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

- Zhengrong Yang,

- Prince Asare Vitenu-Sackey,

- Lizhong Hao,

- Published: July 11, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The effective and efficient management of financial systems and resources fosters a socioeconomic climate conducive to technological and innovative advancement, thereby fostering long-term economic growth. The study used panel data from 72 countries classified as less financially developed between 2009 and 2017 to examine the role of economic freedom and inclusive growth in financial development. For the long-run estimations, we utilised the linear dynamic panel GMM-IV estimator, panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) linear regression method, and contemporaneous correlation estimator, a generalised least squares method. Our analyses indicate that economic liberty, inclusive growth, and capital stock significantly contribute to financial development in a positive manner. Moreover, inclusive growth contributes positively to overall financial development by enhancing economic freedom. Regardless of exogenous and endogenous shocks, we found that the tax burden and investment freedom are negative drivers of financial development as measured by the overall financial development index. In contrast, protection of property rights, government spending, monetary freedom, and financial freedom are positive and significant drivers of economic growth.

Citation: Yang Z, Vitenu-Sackey PA, Hao L, Tao Y (2023) Economic freedom, inclusive growth, and financial development: A heterogeneous panel analysis of developing countries. PLoS ONE 18(7): e0288346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346

Editor: Nikeel Nishkar Kumar, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, AUSTRALIA

Received: January 9, 2023; Accepted: June 23, 2023; Published: July 11, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Yang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data that support this study can be found in the Mendeley Data repository at 10.17632/6bcpkytp52.1 .

Funding: Z Y National Social Science Fund Project “ Research on the Mechanism and Countermeasures of Digital Finance to Support SME Credit Community Financing” (No. 22BJY076). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In the pursuit of sustainable economic development, finance is an important and relevant factor [ 1 , 2 ]. However, countries with limited financial resources could be more productive if their financial resources and systems were managed effectively and efficiently [ 3 ]. Inadvertently, the effective and efficient management of financial systems and resources fosters a socioeconomic climate conducive to technological and innovation advancement, which fosters long-term economic growth [ 1 – 3 ]. Moreover, economic freedom creates two paths for growth: (i) the path for the development of new technologies and new designs, which advance technological progress and serve as essential growth stimulants; and (ii) the level of market investment and openness of an economy. In other words, the function of legal structures, such as freedom from corruption, protection of property rights, effectiveness of the judiciary, etc., ensures the protection of the property rights of individuals and institutions [ 4 ]. The endogenous relationship between economic freedom, financial market crashes, and financial market structures has been established. As a result of economic freedom’s unregulated framework, the probability of financial market collapses is inescapable. Nonetheless, economic liberty provides a degree of transparency that could reduce regulatory uncertainty and the likelihood of crashes [ 5 ]. Economic freedom is important for creating incentives. De Haan and Sturm [ 6 ] said that a country’s growth or stagnation depends on its economic freedom or strong socioeconomic institutions.

According to finance-growth theory, the variation in the quality and quantity of financial systems is critical to the expansion of an economy. According to Fung [ 7 ] and Sadorsky [ 8 ], economic growth results from financial development through two channels: first, the effectiveness of financial systems leads to the accumulation of financial resources for productive use, and second, financial liberalisation promotes risk-sharing by increasing investment and decreasing the cost of equity, which results in economic growth. Given these factors, we can assert that financial development leads to inclusive growth via enhanced socioeconomic institutions or economic liberty. Individuals and businesses have the right to own property in a free economy, and minimal taxes ensure high participation in economic activity. Despite this, inclusive growth depends on stronger socioeconomic institutions (economic freedom) based on effective government, the rule of law, open markets, and effective regulation. Consequently, promoting economic freedom results in inclusive growth [ 9 ] and advancing financial development [ 8 ]. Contrary to the foregoing, increased taxes and tariffs, stringent regulatory controls, lax startup support, increased business investment, etc., do not provide more level playing fields and competitive markets—perhaps they are not pro-business policies that stimulate inclusive growth [ 10 ].

Numerous empirical studies have concluded that financial liberalisation, a subset of economic freedom that measures access to credit and capital markets, is strongly correlated with higher economic growth, less restrictive credit constraints, and lower consumption growth volatility for smaller firms [ 11 , 12 ]. Other scholars, however, have demonstrated that financial liberalisation in capital and credit markets increases the efficiency of financial institutions, decreases intermediation costs, and improves economic outcomes through economic liberty [ 13 , 14 ]. Kouton [ 15 ] analysed the connection between economic freedom and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa using a system GMM estimator from 1996 to 2016. The result indicates that economic freedom and inclusive growth have a positive and significant relationship, as they are highly interconnected. In support of this conclusion, Olayinka Kolawole [ 16 ] opined that the design and implementation of policies that could increase investment freedom, strengthen labour freedom, and ensure the protection of property rights would significantly contribute to inclusive growth. In other words, inclusive growth could result from job creation to generate a sustainable income through economic expansion. Coetzee and Kleynhans [ 17 ] recognise that economic freedom and economic growth are interdependent, as higher levels of economic growth result from greater economic freedom. Theoretically, according to Sergeyev [ 18 ], a higher level of financial development is likely to reduce the sensitivity of an economy. However, economic freedom as a result of financial development affects the susceptibility of growth to shocks.

Given these arguments, we attempt to delve deeply into the economic freedom-inclusive growth-financial development nexus in order to provide new evidence by: first employing the financial development index and its dimensions and sub-dimensions, thus financial markets and institution development indexes, as well as access, depth, and efficiency indexes. To the best of our knowledge, no study has attempted to use these indexes to investigate this nexus. Most financial development studies employ proxies such as credit to the private sector, broad money to GDP, stock market capitalization, savings, loan growth rate, and so on [ 4 , 18 – 22 ]. According to the IMF, numerous studies estimate the effect of financial development on economic growth, wealth distribution, and stability; typically, these studies use one or two variables for financial depth to represent financial development, such as stock market capitalization or domestic credit to the private sector (private credit to GDP). These measures, however, do not fully account for the complicated and multifaceted nature of financial development. As a result, we rely on this index to capture the complex, multifaceted nature of financial development, such as financial system depth, access, and efficiency.

Second, the individual effect on the dimensional indexes of financial development is assessed using the Heritage Foundation’s twelve indicators of economic freedom as well as the overall economic freedom index. Because most studies rely on the overall index of economic freedom [ 15 , 18 ], we tend to use the sub-dimensions to reveal their positive and negative effects, as well as the major drivers of financial development. Some studies, on the other hand, used the Fraiser Institute’s overall index of economic freedom [ 5 , 17 , 20 ]. However, we use the Heritage Foundation’s Economic Freedom Index with the assumption that economic freedom leads to increased prosperity, and that the Index of Economic Freedom demonstrates the positive relationship between economic freedom and a variety of beneficial social and economic goals. Economic freedom is strongly linked to better societies, healthier environments, higher per capita incomes, human progress, democracy, and poverty eradication.

Thirdly, we make use of the linear dynamic panel data GMM IV estimator [ 23 ], the panel corrected standard errors linear regression estimator, and the generalised least square with correlated disturbances (contemporaneous correlation) estimator. The linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator fits dynamic models by employing either the Blundell-Bond/Arellano-Bover system estimator or the Arellano estimator to estimate complex models more easily than the estimators described previously [ 23 ]. For robust inference, we utilised the panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) linear regression and contemporaneous correlation estimator, and the generalised least square (GLS) with correlation disturbances methods. Using panel corrected standard errors (PCSE), we tend to resolve the issue of heteroscedasticity that could arise in the model’s standard errors [ 24 ]–since the data series exhibited mixed order of integration, this method is essentially appropriate to ensure the explicit resolution of measurement errors. In addition, the PCSE could address serial correlation, autocorrelation, simultaneity bias, and heterogeneity. Consequently, we use the GLS with correlated disturbances estimator for robust confirmation of the PCSE’s results. According to Koreisha and Fang [ 25 ], the GLS has the statistical advantage of identifying weak and inefficient parameters that can be estimated in the procedure and then corrected. In general, we employ these methods to address potential endogeneity concerns. For example, the GMM-IV method employs the lag effect of the dependent variable as a tool to control for any potential endogeneity bias.

Due to the financial crisis that occurred between 2007 and 2008, the study begins from 2009, with the assumption that, after a crisis, every country will tend to strengthen and improve the breadth, accessibility, and efficiency of its financial systems. According to De Haan and Sturm [ 26 ], in the aftermath of a crisis, countries tend to tighten regulations to allay fears of future uncertainties that could portend slower output growth–perhaps this strategy reduces economic freedom.

Our paper is organised as follows: Section 2 describes the theoretical context, Section 3 describes the econometric approach, including methodology, data, and variables, Section 4 presents the results and findings discussion, and Section 5 concludes the study.

Theoretical background

In Eq ( 1 ), Δ y i , t and y i , t -1 represents economic growth and its lagged of GDP per capita in logarithm, credit represents financial development, shock represents exogenous shocks thus annual inflation rate of oil prices multiplied by net fuel exports as a share of GDP, γ represents output variability hence economic growth volatility, and X i , t represents the control variables such as the logarithm of government share in gross domestic product, investment ratio, and population growth rate.

The concept of investment composition is used to illustrate this mechanism in the explanation. Short-term investments face fewer obstacles than long-term investments because they do not necessitate a longer implementation period. These obstacles are essentially shocks, both endogenous and exogenous shocks, that affect an economy in various ways. Exogenous shocks influence an economy as a result of external interactions, particularly with the outside world, whereas endogenous shocks influence liquidity on occasion due to imperfections within the economy. In this context, weaker social and economic institutions would generate stronger shocks (economic freedom). Because property rights protection is weaker, agents are highly motivated to seize people’s property. Moreover, raiders may inappropriately expropriate firm owners; consequently, the weaker the socioeconomic institutions, the more susceptible firms are to shocks. In other words, firms generate greater profits when the probability of overcoming shocks is greater. Profitability enables businesses to resist unjustified takeovers by employing competent attorneys to seek legal redress.

When firms recognise the risk of disruption from shocks, they are traditionally disincentivised from making long-term investments. Essentially, this occurs when there is a negative exogenous shock to productivity; when firms’ profits decline, the probability of long-term investment interruptions increases. Unintentionally, exogenous shocks have a negative impact on investments, leading to weakened socioeconomic institutions (economic freedom). When the level of financial development is greater, firms are able to borrow; consequently, they have the capacity to withstand investment shocks and growth sensitivity. Improved socioeconomic institutions (economic liberty) pave the way for firms’ and individuals’ uniform access to financial institutions and markets [ 9 ].

Numerous scholars have demonstrated a correlation between socioeconomic institutions, economic growth, and the evolution of the financial system. These academics argue that economic institutions (quality of markets, protection of property rights, government integrity, etc.) and political institutions (media freedom, effectiveness of the judiciary, right to vote, etc.) represent economic freedom and ensure economic development by empowering the incentives of economic agents and distributing political authority [ 27 , 28 ]. Beck and Levine [ 29 ] argue, in support of these scholarly works, that countries with robust legal structures ensure contract enforcement and property and investor rights protection, which strengthen financial systems and economic agents. In other words, efficient financial systems resulting from robust socioeconomic institutions result in the equitable distribution of capital among individuals and businesses, thereby ensuring economic efficiency, individual freedom, and social justice.

Econometric approach

Empirical strategy.

To achieve the study’s objective, we adopted some econometric approaches. The techniques used are (1) unit root test where we employed the tests of Pesaran [ 35 ] CIPS and CADF tests and Im, Pesaran and Shin [ 36 ] IPS test; (2) cross-sectional dependence test where we employed Pesaran [ 37 ] test; (3) cointegration test where we employed Pedroni [ 38 ], Westerlund [ 39 ] and Kao [ 40 ] cointegration tests; (4) variance inflation factor for multicollinearity test, homogeneity test [ 41 ], and correlation matrix where we used pairwise correlation test; (5) long-run parameter estimations where we used linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator, panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) linear regression method, and contemporaneous correlation estimator thus generalized least square method.

First, we examine the data series for a unit root to determine whether the variables are stationary or nonstationary. Consequently, at a significance level of 5% or less, we expect to reject the unit root assumption. After determining that the variables are non-stationary, we conduct a cross-sectional dependence test to determine the cross-sectional independence of the individual error terms of the panels and a homogeneity test to determine the heterogeneity of the slope. The cointegration relationship between the dependent and independent variables is then examined. Evidence of a cointegration relationship suggests a long-run equilibrium between the dependent and independent variables; consequently, the estimations will depict the long-term relationships. In addition, a correlation matrix and variance inflation factor were computed to test for multicollinearity and the correlation signs of the variables. The multicollinearity rule of thumb states that no two or more independent variables should have correlation coefficients between -0.70 and +0.70 with the dependent variable [ 42 ]. The variance inflation factor value should be less than 10 and the tolerance level should be greater than 0.2. Multicollinearity evidence may result in erroneous long-term parameter coefficients.

After establishing a significant and dependable data series, we employ the linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator to conduct long-run estimations. The linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator is based on the Blundell and Bond [ 43 ] and Arellano and Bover [ 44 ] estimators, which use moment conditions in which the lagged levels of the predetermined and dependent variables serve as instruments for the differenced equation. In addition, the linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator fits dynamic models by employing either the Blundell-Bond/Arellano-Bover system estimator or the Arellano estimator to estimate complex models more easily than those mentioned previously [ 23 ]. For robust inference, we utilised the panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) linear regression and contemporaneous correlation estimator and the generalised least square (GLS) with correlation disturbances method. Using panel corrected standard errors (PCSE), we tend to resolve the issue of heteroscedasticity that could arise in the model’s standard errors [ 24 ]. In addition, the PCSE could address serial correlation, autocorrelation, simultaneity bias, and heterogeneity. Consequently, we use the GLS with correlated disturbances estimator for robust confirmation of the PCSE’s results. According to Koreisha and Fang [ 25 ], the GLS has the statistical advantage of identifying weak and inefficient parameters that can be estimated in the procedure and then corrected. See Appendix in S1 File for more details about the methods.

Empirical model

In Eqs ( 3 ) and ( 4 ), FDIX denotes the overall financial development index. Financial development is measured by indexes of financial institutions’ development and financial markets development that incorporate their level of access, depth, and efficiency. EFIO stands for economic freedom index and encompasses 12-dimensional indicators. LNGDPPC represents inclusive growth; thus, gross domestic product per person employed, GCF stands for gross capital formation, which denotes investment, and POPG stands for population growth. EXOGSHOCK and ENDOSHOCK represent exogenous and endogenous shocks, respectively: the real effective exchange rate and consumer price index volatility. u represents the error terms, i represents a cross-section or panel of 72 countries, and t represents the study period 2009 to 2017. The 12 indicators measuring economic freedom have been outlined in Table 1 , and the other sub-indices of financial development–the sub-dimensions are considered in our proposed models. See S5 Table in S1 File for the list of countries used in the study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t001

The study used panel data on 72 countries classified as less financially developed from 2009 to 2017. The countries were selected based on the IMF’s financial development index, with only those scoring below 0.5 being considered. However, any country below the financial development index’s median value was classified as less financially developed. The dependent variable of our study is financial development with dimensions of financial institutions and markets development. However, the independent variables are economic freedom and inclusive growth. Economic freedom has 12 sub-dimensions: tax burden, government integrity, government spending, business freedom, investment freedom, financial freedom, labour freedom, monetary freedom, property right, judiciary effectiveness, tax burden, and trade freedom. Other variables such as population growth, gross capital formation, endogenous shock, and exogenous shock are used as control variables (see Table 1 for the description of variables).

We use Kouton’s [ 15 ] study to measure inclusive growth using GDP per person employed, with support from Raheem and Isah [ 45 ]. Kouton [ 15 ] investigated the link between economic freedom and inclusive growth, whereas Raheem and Isah [ 45 ] investigated the link between natural resource rent, human capital development, and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. We contend, based on their assumptions, that the conduit through which people can ultimately benefit from growth is through employment by earning income. In the same vein, we adopted GDP per person employed to measure inclusive growth by taking into account the economic benefits that may result from increased output rates, such as job creation, a reduction in abject poverty, and increased economic size. Furthermore, the United Nations uses the annual growth rate of GDP per person employed to measure inclusive growth and Sustainable Development Goal #8. As a result, the United Nations urges governments and policymakers to prioritise the employment aspect of growth in order to significantly increase inclusive growth [ 15 ]. It is worth noting that inclusive growth promotes decent employment, which leads to income security in the long run.

Because unemployment harms the economy and ordinary citizens, inclusive growth [ 46 ] and economic freedom [ 47 ] result in productive employment. Furthermore, economic growth is dependent on financial development in a country with a higher level of financial development. Such a country has a higher per capita income and economic growth [ 19 , 20 , 48 ]. Furthermore, regulatory reductions that result in financial liberalisation stimulate economic growth and reduce the likelihood of a financial crisis [ 49 ]. We tend to acknowledge endogenous and exogenous factors that could arise from productivity-enhancing investment volatility by including endogenous and exogenous shocks because robust financial constraints make growth and investment more vulnerable to shocks. In the same vein, the relationship between growth and volatility is inversely related [ 20 ]. To represent endogenous and exogenous shocks, we used the annual standard deviation of the consumer price index and the real effective exchange rate, respectively. Notably, volatility can be caused by a variety of factors, including changes in energy supply prices, government budget policies, exchange rate volatility, inflation volatility, and so on [ 20 ]. Furthermore, high volatility may exacerbate financial development because the ability to withstand liquidity shocks cannot be supported by weak financial markets and institutions [ 50 ]. Furthermore, we include population growth against the backdrop of Barro and Lee [ 51 ] policy variables to measure the effect of social policy with support from Blau [ 5 ].

Results and discussion

Summary statistics..

Table 2 displays the summary statistics for the variables in the study. Given the countries’ heterogeneous economic characteristics, we found that the average index score for financial development was 0.296 with a standard deviation of 0.140 annually. Whereas the economic freedom index score averaged 4.019 per year with a standard deviation of 0.145, the GDP per person employed increased by 9.114% per year with a standard deviation of 0.862%. Furthermore, gross capital formation, a measure of capital investment, increased at an annual rate of 22.79% on average. This implies that countries in our sample invested in more capital projects during the sample period, thereby supporting financial system growth and promoting economic freedom and inclusive growth. The population growth rate, on the other hand, was 0.023% per year on average, with a standard deviation of 0.938%. (See Table 3 for more details.) More importantly, the Jarque-Bera test, which shows p-values less than 0.05, confirmed that our data series is not normally distributed.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t003

Panel unit root and cross-sectional dependence tests.

We used unit root tests to determine the degree of stationarity of the variables in the study. Table 4 does, however, show the results of the tests. Unit root tests were performed on Pesaran [ 35 ] and Im, Pesaran and Shin [ 36 ]. According to the results, there is no unit root in the variables because IPS tests rejected the unit root assumption at the first difference. Meanwhile, CIPS and CADF depicted mixed order of integration. Despite the inconsistent results of the tests, we find evidence that the variables are stationary at first difference at 1% and 5% significance levels using the first generation unit root test, thus IPS. In addition, we used the Pesaran [ 37 ] cross-sectional dependence test, which has statistical power to detect any weak cross-sectional dependency. According to the results, all variables have cross-sectional dependence; thus, the error terms of the variables correlate in the individual panels. We present the cross-sectional dependence test results in S6 Table in S1 File .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t004

Cointegration tests.

Checking for long-term relationships or equilibrium between dependent and independent variables is essential because it provides confidence in the estimation of long-term parameters. In this regard, three cointegration tests were conducted to determine the long-term relationship between the dependent and independent variables of the study. Table 5 presents the results. The results of the tests indicate that the variables are cointegrated, as they have a long-run relationship. Specifically, tests conducted by Kao [ 40 ] and Westerlund [ 39 ]confirmed cointegration at 1% and 5% significance levels. In addition, the Pedroni [ 38 ] test confirmed, at a 1% significance level, that the variables have a long-term relationship within and between dimensions.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t005

Correlation, multicollinearity and homogeneity tests.

Table 6 displays the results of our correlation matrix; for the sake of clarity, we present only the results of the table’s primary variables. According to the results, however, there was no evidence of multicollinearity because none of the independent variables exhibited a strong correlation with the dependent variables. Specifically, only LNGDPPC had a high correlation coefficient, but it did not meet the criteria for collinearity. According to Sun and Tong [ 42 ], no two or more independent variables should have correlation coefficients with dependent variables greater than—or + 0.70. On the other hand, we found significant positive correlations between economic freedom, inclusive growth, gross capital formation, and financial development, whereas population growth demonstrated a significant negative correlation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t006

The assumption of multicollinearity between the dependent and independent variables is rejected based on the results of the multicollinearity test presented in Table 6 . Specifically, the VIF values of the variables were all less than 10, and the tolerance levels were also greater than 0. The correlation coefficients did not reveal any collinearity or multicollinearity. In contrast, Table 6 displays the homogeneity test performed to determine whether the slope coefficients of the parameters to be estimated are heterogeneous. The assumption that the slope is homogeneous is rejected at the 1% and 5% significance levels when the delta and adj. delta values of the homogeneity test are considered.

Heterogeneous analysis of economic freedom, inclusive growth, and financial development.

After confirming cointegration and conducting satisfactory pre-diagnostic tests, long-run estimations between the dependent and independent variables were conducted. In this regard, we utilised the linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator, which has the ability to resolve the model’s potential reverse causality and endogeneity. Based on our findings (see Table 7 ), we observed a positive and significant correlation between economic freedom and overall financial development, as well as inclusive growth and overall financial development. The findings indicate that regardless of the existence of shocks, an increase in economic freedom and the promotion of inclusive growth could substantially boost a nation’s financial development. Additionally, economic freedom and inclusive growth have a positive relationship with the development of financial institutions and markets. In S1 Table in S1 File , we present the results of our analyses pertaining to the disaggregate indexes of financial development, i.e., the indexes for financial institutions and markets.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.t007

In an effort to determine the indirect effect of economic freedom and inclusive growth on the sub-dimensions of financial institutions and market development as a composite measure of overall financial development, we investigated access, depth, and efficiency. Economic freedom has a positive relationship with the efficiency of financial institutions and the access, depth, and efficiency of financial markets, except for the access of financial institutions, which is negative.

On the other hand, we found that inclusive growth contributes positively to the access, depth, and efficiency of financial institutions and the depth of financial markets, but negatively to their access and efficiency. Invariably, the models in which the relationships between economic freedom, inclusive growth, and sub-dimensions of financial institutions and markets were inverse suffered from autocorrelation, indicating a statistical inability to infer the results. For a robust inference, we used the linear panel corrected standard errors (PSCE) method and the generalised least squares (GLS) estimator to resolve the issue of autocorrelation and any correlation disturbances encountered by the linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator during the analyses. The results of the robustness test are shown in S2-S4 Tables in S1 File . In the estimations, we relied on two models, model 1 of which does not account for shocks (both endogenous and exogenous), while model 2 does. In addition, S1 Table in S1 File details the estimations that considered the overall index of financial development and economic freedom, the disaggregate index of financial development, i.e., the financial market development index, and the financial institution development index, whereas S3 Table in S1 File details the estimations of the sub-dimensions of the financial institutions and financial markets development indices, i.e., depth, access, and efficiency. The disaggregated index of economic freedom and its association with financial development (global index, disaggregated index, and sub-dimensions) and inclusive growth are presented in S3 Table in S1 File .

Our estimations indicate that economic freedom, inclusive growth, and capital stock (gross capital formation) contribute positively and significantly to financial development. Specifically, we found that a one-percentage-point increase in overall economic freedom can boost financial development by 0.043%, 0.040%, and 0.033% at the 1% and 5% significance levels, even in the presence of negative endogenous and exogenous shocks. Moreover, inclusive growth positively contributes to overall financial development via enhanced economic freedom, such that a percentage point increase in inclusive growth could result in a 0.087%, 0.088%, or 0.089% increase in financial development at a 1% significance level. In an account of capital stock, there is evidence that it is essential and significant in terms of financial development—a percentage point increase in gross capital formation (capital stock) could significantly lead to a 0.005% to 0.006% increase in financial development at a 1% significance level. Despite the presence of exogenous or endogenous shocks, we discovered that the population growth rate has a negative impact on economic growth. Specifically, a percentage point increase in population growth rate could negate financial development by 0.005% to 0.006% at a 5% significance level; meanwhile, our robust estimation yielded a coefficient that was insignificant.

Taking into account the disaggregate or dimensional financial development index measures—the financial institutions development index and the financial markets development index—we found that economic freedom and inclusive growth positively impact the development of financial markets and institutions. However, gross capital formation (capital stock) and population growth are inconsistent. In the event of shocks, endogenous and exogenous shocks have negative and positive effects on the capital stock, respectively, and contribute insignificantly to the development of financial institutions. In the absence of shocks, however, capital stock (gross capital formation) positively influences the relationship between economic freedom, inclusive growth, and financial development. Meanwhile, regardless of the presence of shocks, capital stock contributes positively to the development of financial markets. On the other hand, population growth contributes negatively and significantly to the development of financial institutions but plays no role in the development of financial markets.

In addition, we analysed the influence of economic freedom and inclusive growth on the sub-dimensions of financial institutions and market development measures (see S3 Table in S1 File ). In particular, we considered the access, depth, and efficiency indexes of financial institutions as well as the access, depth, and efficiency indexes of financial markets. Regarding financial institutions, we found that economic freedom contributes positively and significantly to depth and efficiency but negatively to accessibility, regardless of the presence of shocks. And inclusive growth contributes positively and significantly to the accessibility, depth, and efficiency of financial institutions. In an account of capital stock, we observed a positive relationship between the efficiency of financial institutions and the depth of financial institutions when neither endogenous nor exogenous shocks are present. Meanwhile, we observed a negative and significant impact of capital stock on the access of financial institutions in the presence of exogenous and endogenous shocks but no impact in the absence of shocks. Moreover, population growth positively influences the relationship between economic freedom, inclusive growth, and the depth of financial institutions but negatively influences the access and efficiency of financial institutions. In terms of the development of financial markets, we observed a positive and statistically significant relationship between economic freedom and access to and depth of financial markets.

In contrast, the relationship between economic freedom and the efficiency of financial markets was negative and statistically significant, regardless of the presence of shocks. However, we observed a significant positive effect of capital stock (gross capital formation) on the accessibility, depth, and efficiency of financial markets, regardless of the presence of shocks. On the other hand, we observed a positive and significant effect of population growth on the access and depth of financial markets but a negative effect on their efficiency, regardless of exogenous or endogenous shocks. The results of our estimations of the sub-dimensions of economic freedom and financial development are presented in S4 Table in S1 File . Prior to that, we conducted analyses with the overall financial development index and economic freedom subdimensions in mind. Regardless of exogenous and endogenous shocks, the assessments found that tax burden and investment freedom are negative drivers of financial development as measured by the overall financial development index. In contrast, we found that the positive and significant drivers of financial development are the protection of property rights, government spending, monetary freedom, and financial freedom. Moreover, inclusive growth intervenes proportionally in this relationship; nonetheless, inclusive growth is a significant factor for economic development. We observed that the positive drivers of the development of financial institutions are business freedom, trade freedom, government integrity, monetary freedom, and financial freedom.

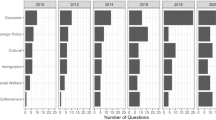

Investment freedom and tax burden, on the other hand, have the opposite effect on the development of financial institutions. In an account of the development of financial markets, we observed that positive drivers include protection of property rights, government spending, monetary freedom, and financial freedom. On the other hand, what hurts the growth of financial markets are free trade, freedom to invest, and high taxes. In addition, we investigated the sub-dimensions of financial markets and institutions—namely, access, depth, and efficiency—to decipher the impact of economic freedom on them. Tax burden and investment freedom are identical factors that consistently and negatively affect the accessibility, depth, and efficiency of financial institutions and markets. On the other hand, financial freedom makes financial institutions and markets more accessible, deeper, and better at what they do (see S4 Table in S1 File ). Also, Fig 1 depicts the overall impact of economic freedom on financial development with influence of inclusive growth.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.g001

To determine whether our data series is statistically reliable for estimations, preliminary tests were conducted. Validity and reliability were confirmed. Specifically, we found no evidence of unit root, multicollinearity, cointegration, and cross-sectional dependence. Our findings suggest that economic freedom that reflects the development of socioeconomic institutions influences financial development positively through inclusive growth, i.e., GDP per employed person. This finding backs up the claims of Assi et al. [ 4 ], Isiksal et al. [ 3 ], Kouton [ 15 ], Murray and Press [ 9 ], and Sadorsky [ 8 ], who argue that governments’ effectiveness in ensuring the independence of economic and political institutions, property rights protection, and tax reduction ensure inclusive growth—as well as strengthening financial sector development in a sustainable manner. To support this claim, Blau [ 5 ] exegetically confirmed that the strength of property rights protection and the level of free trade contribute to a lesser extent to the reduction of financial market crashes. In addition, the level of transparency in an economy as a result of economic freedom mitigates the uncertainties surrounding regulation and likely reduces the likelihood of shocks and crashes.

When an economy’s level of financial development is high, its sensitivity decreases [ 18 ]. In addition, Sergeyev [ 18 ] argues that economic freedom (socioeconomic institutions) affects the sensitivity of economic growth to endogenous and exogenous shocks. However, a greater level of financial development mitigates the severity of shocks. Nonetheless, it is essential to strengthen the legal framework and policy initiatives designed to effectively and efficiently manage the financial system or sector to withstand fluctuations or uncertainties [ 3 ]—this supports our findings that financial and monetary freedom is essential and positively contributes to financial development. In nations with a high degree of economic freedom, financial development ensures financial resources accumulation and financial liberalisation that seeks to put unproductive resources to beneficial use, boosts investment [ 10 ] and reduces equity costs [ 4 , 18 , 20 ], which ultimately results in inclusive economic growth.

Conclusion and practical implication

The study used panel data on 72 countries classified as less financially developed from 2009 to 2017 to critically assess the role of economic freedom and inclusive growth in financial development. To achieve the study’s objective, we adopted some econometric methodologies. The methodologies used are (i) unit root test where we employed the tests of Pesaran [ 35 ] CIPS and CADF tests and Im, Pesaran & Shin [ 36 ] IPS test; (ii) cross-sectional dependence test where we employed Pesaran [ 37 ] test; (iii) cointegration test where we employed Westerlund [ 39 ], Pedroni [ 38 ] and Kao [ 40 ] cointegration tests; (iv) correlation matrix where we used pairwise correlation test; Pesaran and Yamagata homogeneity test, and variance inflation factor, (v) long-run parameter estimations where we used linear dynamic panel data GMM-IV estimator, panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) linear regression method, and contemporaneous correlation estimator thus generalized least square method.

Our estimations indicate that economic freedom, inclusive growth, and capital stock positively contribute significantly to financial development. Specifically, we found that a one-percentage-point increase in overall economic freedom can boost financial development by 0.043%, 0.040%, and 0.033% at the 1% and 5% significance levels, even in the presence of negative endogenous and exogenous shocks. Moreover, inclusive growth positively contributes to overall financial development via enhanced economic freedom, such that a percentage point increase in inclusive growth could result in a 0.087%, 0.088%, or 0.089% increase in financial development at a 1% significance level. Regardless of exogenous and endogenous shocks, we found that tax burden and investment freedom are negative drivers of financial development as measured by the overall financial development index. In contrast, the protection of property rights, government spending, monetary liberty, and financial liberty are positive and significant drivers of economic growth in support of D’Agostino et al. [ 30 ]. According to the study’s findings, improved and strengthened financial sector regulatory and efficiency leads to financial development but reduces investment freedom; that is, restrictions on capital inflows and a high level of tax burden hinder or impede financial institutions’ and markets’ access, depth, and efficiency. Moreover, the development of the financial sector depends on monetary freedom, which reflects price stability and effective price control, and business freedom (business regulatory effectiveness and efficiency). Cross [ 10 ] elaborated, in support of these findings, that competitive markets and level playing fields for businesses are the overarching pro-business policies resulting from tax reduction, regulatory control limitation, startup empowerment, reining in occupational licensure rules, boosting business investment, and tariff elimination which is in support of Ding et al. [ 52 ], Huang J, Ulanowicz [ 53 ] and Singhal [ 54 ]. Our findings are consistent with the fiance-growth theory, which posits that variation in the quality and quantity of financial systems is crucial to the expansion of an economy, and that the efficiency of financial systems may lead to the accumulation of financial resources for productive use. In addition, financial liberalisation encourages risk-sharing by boosting investment and reducing the cost of equity, resulting in economic expansion. Therefore, financial development facilitates inclusive growth through improved socioeconomic institutions or economic liberty.

Practical implication

Our findings imply that property rights protection regulations and laws should be effectively guarded and enforced due to their contribution to economic growth. Importantly, financial sector regulations and rules should be staffed effectively and efficiently to ensure the financial sector’s continued growth. In addition, price stability and price control mechanisms should be designed and strategized to support the development of the financial sector. On the other hand, governments should increase their spending on productive sectors and promote inclusive growth through sustainable policy initiatives—for example, barriers to employment should be removed to encourage businesses to create more jobs. However, restrictions on capital investment inflows and high tax rates should be reduced to ensure inclusive and sustainable financial development. Our findings set out the following future research directions:

- Identify the mechanisms through which tax burden and investment freedom affect financial development.

- Investigate the impact on other policy variables on financial development.

- Analyse the effect of financial development on economic growth and possible transmission channels.

- Consider country-specific variations that could identify the idiosyncratic effect of tax burden, investment freedom and financial development

Supporting information

S1 file. this is the file that contains s1 to s6 tables and appendix..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288346.s001

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 10. Cross P. Business ambition must be a Canadian value Canada: Fraser Institute. [updated September 30, 2021]. Available from: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/business-ambition-must-be-a-canadian-value .

- 20. Aghion P, Angeletos GM, Banerjee A, Manova K. Volatility and Growth: Credit Constraints and Productivity-Enhancing Investment. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc; 2005 May.

- 23. Blundell R, Bond S, Windmeijer F. Estimation in dynamic panel data models: improving on the performance of the standard GMM estimator. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2001 Feb 13.

- 24. Greene W. Discrete choice modeling. InPalgrave handbook of econometrics 2009 (pp. 473–556). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- 28. North DC. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge university press; 1990 Oct 26.

- 37. Pesaran MH. Time series and panel data econometrics. Oxford University Press; 2015.

- 47. Feldmann H. Economic freedom and unemployment. James Gwartney, Joshua Hall, and Robert Lawson, Economic Freedom of the World: 2010 Annual Report. 2010:187–201.

- 50. Fanelli J, editor. Macroeconomic volatility, institutions and financial architectures: the developing world experience. Springer; 2008 Jan 17.

Advertisement

Economic Freedom, Income Inequality and Life Satisfaction in OECD Countries

- Research Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2017

- Volume 19 , pages 2071–2093, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Johan Graafland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1497-803X 1 , 2 &

- Bjorn Lous 2

16k Accesses

57 Citations

75 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Since Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century in 2014, scientific interest into the impact of income inequality on society has been on the rise. However, little is known about the mediating role of income inequality in the relationship between market institutions and subjective well-being. Using panel analysis on a sample of 21 OECD countries to test the effects of five different types of economic freedom on income inequality, we find that fiscal freedom, free trade and freedom from government regulation increase income inequality, whereas sound money decreases income inequality. Income inequality is found to have a negative effect on life satisfaction. Mediation tests show that income inequality mediates the influence of fiscal freedom, free trade and freedom from government regulation on life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Public Purposes of Private Education: a Civic Outcomes Meta-Analysis

Divided by Income? Policy Preferences of the Rich and Poor Within the Democratic and Republican Parties

The impact of economic, social, and political globalization and democracy on life expectancy in low-income countries: are sustainable development goals contradictory?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Up until now, a vast amount of literature has been produced on the variables affecting subjective well-being measures (Frey and Stutzer 2001 ; Dolan et al. 2008 ; Blanchflower and Oswald 2011 ). One of the research subjects which is still in its infancy, however, is the relationship between economic freedom and subjective well-being. The concept of economic freedom relates to the degree of personal choice, voluntary exchange, freedom of competition, and protection of privately owned property afforded by society (Gwartney et al. 2004 ). Previous research has shown that economic freedom stimulates life satisfaction (Veenhoven 2000 ; Ovaska and Takashima 2006 ; Gropper et al. 2011 ). Graafland and Compen ( 2015 ) show that the positive relationship between economic freedom and life satisfaction is mediated by income per capita and generalized trust. Indeed, as many studies have shown, economic freedom stimulates income per capita or economic growth (Dawson 1998 ; De Haan and Sturm 2000 ; Gwartney et al. 2004 ; De Haan et al. 2006 ; Justesen 2008 ; Altman 2008 ), and other research has shown that income per capita increases subjective well-being (Stevenson and Wolfers 2008 ; Fischer 2008 ). Trust has also been shown to be dependent on economic freedom (Berggren and Jordahl 2006 ) as well as being a determinant of life satisfaction (Helliwell 2003 , 2006 ; Bjørnskov et al. 2007 , 2010 ; Oishi et al. 2011 ).

Another potentially important mediator between economic freedom and life satisfaction, that has not yet been researched, is income inequality, interest in which has been fueled by the publication of Piketty ( 2014 ). With data based on fifteen years of research on income and wealth inequality, he shows that both income and wealth inequality have been rising continuously since the 1980s. Sixty per cent of economic growth since the 1960s has gone to the top 1% (Piketty and Saez 2013 ). According to Piketty, this has been caused by a combination of market forces and economic policy. A high level of economic freedom implies, amongst other things, low marginal tax rates that provide little room for redistributive policies (Berggren 1999 ). According to Piketty, low taxes signal that the government does not object to excessive remuneration (also Dincer and Gunalp 2012 ). Economic freedom additionally includes a low level of government regulation of financial, product, and labor markets, and this may further enhance inequality by enabling those with economic power to use it to their personal benefit (Stiglitz 2012 ). Wilkinson and Pickett ( 2010 ) argue that inequality negatively affects physical and mental health and therefore ultimately human flourishing.

The central research question that we focus on in this paper is therefore: How does income inequality mediate the relationship between economic freedom and life satisfaction in OECD countries? In order to answer this research question, we focus on two sub questions: First, how do (different dimensions of) economic freedom influence income inequality? Second, how does income inequality affect life satisfaction? By analyzing these questions, this paper aims to extend our knowledge of the role of income inequality in the influences of various indicators of economic freedom on life satisfaction in Western countries.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the conceptual framework and hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data sources. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis. Section 5 summarizes the main findings and discusses some policy implications.

2 Conceptual Framework

The real question is not whether the market economy works or not. It is whether it works the way we want it to work. Tomas Sedlacek ( 2012 : page 319)

Equality can be based on income, wealth, consumption or any other reasonable proxy for well-being (such as job opportunities and social security). Most of the empirical research focuses on inequality of annual income, because data for other types of inequality are less available and less measurable (Verme 2011 ; Piketty 2014 ). Income inequality is also important for many other dimensions of human well-being (e.g. education, health, etc.). In this paper we therefore focus on income inequality within countries.

Economic freedom means that property rights are secure and that individuals are free to use, exchange, or give their property to another as long as their actions do not violate the identical rights of others (Gwartney et al. 1996 ). Economic freedom has several dimensions: low tax rates (small size of the government), protection of property rights (rule of law), access to sound money (hard currency), freedom to exchange goods and services internationally, and no regulatory restraints that limit the freedom of exchange in credit, labor, and product markets.

In this section we will first discuss the relationship between the various aspects of economic freedom and income inequality. Second, we describe the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction. Finally, the overall conceptual framework is presented.

2.1 Economic Freedom and Income Inequality

Stiglitz ( 2012 ) argued that unfair policies and manipulation of the market through the underlying inequality in political and economic power enabled the top 1% of the income distribution to receive a disproportionate share of economic growth in the US for the last 30 years. This analysis is in line with Roine et al. ( 2009 ) who argued, using data from Atkinson and Piketty’s World Top Income Database, that the high economic growth during the last decades has been mainly beneficial to rich income groups. The increase in GDP did not trickle down, something which holds equally for Anglo-Saxon and continental European countries. Yet, in contrast to the Anglo-Saxon countries, increasing trade has not led to a further increase in the very top incomes in continental Europe within the population class of the richest 10%. According to Roine et al. ( 2009 ), this is due to strong labor market institutions and the equalizing role of the government.

This discussion indicates that inequality is related to government institutions and therefore to (various dimensions of) economic freedom. Some previous studies showed that economic freedom decreases income inequality in the longer run. Scully ( 2002 ) estimated that the index of economic freedom has a small but significant negative impact on the Gini index. Also, Berggren ( 1999 ) found that sustained and gradual increases in economic freedom influence inequality measures negatively. He argued that one cannot rightly claim on theoretical grounds that higher levels of economic freedom go hand in hand with higher levels of income inequality. This relationship is unclear a priori; even when redistribution falls, if the poor take advantage of changes in other variables of economic freedom (such as the protection of property rights, or increased trade liberalization) more so than the rich, inequality may decrease (Gwartney et al. 1996 ; De Vanssay and Spindler 1994 ). Hence, the freedom–inequality relationship should be empirically tested. Using four different variables for inequality, Berggren ( 1999 ) tested this hypothesis controlling for wealth and the illiteracy rate. In all regressions, he found that the lower the initial level of economic freedom and the higher the change in economic freedom, the lower the level of inequality at the end of the sample. Therefore, Berggren concluded that, for the poor, the relatively strong income–growth effect due to a positive change in economic freedom outweighs an increase in income inequality from lower redistributive policies. Berggren mentioned that trade liberalization and financial mobility drive these findings, suggesting that poor people are employed in industries that benefit more from free trade. A problem with Berggren’s analysis is that he used data from 1975–1985. In this period, the economic context was different, especially, as explained by Piketty ( 2014 ), regarding inequality and the economic system. This diminishes the relevance of Berggren’s article for the current state of the economy.

The paper by Bennett and Vedder ( 2013 ) looks at a more recent period. They found a non-linear, parabolic relationship between economic freedom and inequality, concluding that in the very long run (at least 10 years), increases in economic freedom might have a negative effect on inequality. However, they also stated that this reduction in inequality falls in the same time period as the technology boom in the 1990s, and this could mean that this finding is related to exceptional circumstances. Apergis et al. ( 2014 ) studied economic freedom and income inequality through a panel error correction model of US data over the period 1981–2004. They found that economic freedom decreases inequality both in the short and in the long run. On the other hand, Bennett and Nikolaev ( 2014 ) found that economic freedom is related to higher levels of both net and gross Gini coefficients.

In the literature, researchers have usually focused on only one of the five dimensions of economic freedom or on the aggregate index (Berggren and Jordahl 2005 ; Norberg 2002 ; Jäntti and Jenkins 2010 ; Berggren 1999 ; Gwartney et al. 2004 ). This is also the case with Hall and Lawson ( 2014 ), who made an overview of empirical studies using the Economic Freedom Index of Fraser Institute. They found that over two-thirds of 198 studies found a positive impact of economic freedom on well-being, while only 4% found a negative impact. However, three of the studies that did find a negative influence in the overview of Hall and Lawson concern the effect on income inequality. Hall and Lawson therefore conclude that the evidence from these studies indeed indicates that more economic freedom may come at a price of an increase in income inequality. Moreover, they did not look at the components of the index but only considered the aggregate measure. In this paper, we hypothesize that the various dimensions of economic freedom may have different, and partly opposite, effects on income inequality.

First, inequality may be positively related to tax freedom and negatively to the size of government, of which tax income is a major indicator (Berggren and Jordahl 2006 ). Traditionally, one of the major tasks of the government has been redistribution of income, as the ‘market for charity’ is usually subject to a number of failures in large societies (Schwarze and Härpfer 2002 ). Piketty ( 2014 ) stated that income inequality is mainly determined by tax policies. He argued that the progressivity of the tax system is an indicator of the general social morale of a society. It has an important signal function as to what is acceptable with respect to income inequality and therefore even affects income inequality before taxes (gross income inequality). Schneider ( 2012 ) argued that perceptions of the legitimacy of income inequality are important to their appreciation, which is reflected in the tax system (also Schmidt-Catran 2014 ). Therefore, we hypothesize that fiscal freedom increases income inequality.

Second, Norberg ( 2002 ) argued that the free market reduces inequality in the long run, because it protects the private property of all. A high quality of legal structure and security of property rights is particularly relevant for the poor, because in an economy that does not secure private property rights they are much more vulnerable than are the rich and powerful. Lack of respect of private property rights limits economic opportunities and forces the poor to restrict their economic activities to the informal economy. Only the rich elite in such a context has the power and opportunities to initiate profitable, modern economic activities. Gwartney et al. ( 2004 ) empirically studied economic freedom (as an indicator of institutional quality) in relation to cross-country income inequality. They concluded that institutional quality is very important for predicting long-term income differences, but the impact is ambiguous.

With respect to the relationship between access to sound money and inequality, literature has indicated that inflation and inequality are positively related. The underlying reason is that low income households use cash for a greater share of their purchases (Erosa and Ventura 2002 ). The use of financial technologies that hedge against inflation is positively related to household wealth (Mulligan and Sala-i-martin 2000 ). Attanasio et al. ( 1998 ) found that the use of an interest bearing bank account is positively related to educational level and income. Inflation is therefore more costly for low income households. Although Jäntti and Jenkins ( 2010 ) found no relationship between sound money and income inequality in the United Kingdom between 1961 and 1999, other research has confirmed the positive relationship between inflation and income inequality (Beetsma 1992 ; Romer and Romer 1998 ; Easterly and Fischer 2001 ; Albanesi 2002 ). Since access to sound money reduces inflation, we hypothesize that access to sound money reduces income inequality.

Literature has also related inequality to trade openness. Cornia ( 2004 ) argued that trade openness increased within-country inequality in developing countries. The World Bank ( 2006 ) also referred to various researches showing that trade liberalization has a positive influence on wage inequality. This is confirmed by an overview article by Goldberg and Pavcnik ( 2007 ) who showed that the exposure of developing countries to international markets, as measured by the degree of trade protection, the share of imports and/or exports in GDP, the magnitude of foreign direct investment, and exchange rate fluctuations, has increased inequality in the short and medium term, although the precise effect depends on country and time-specific factors. In literature, several explanations are offered for this effect. First, the rise of China and other low-income developing countries may have shifted the comparative advantage from low-skill to intermediate or high skill intensity and therefore increased the demand and wage for skilled labor at the expense of unskilled labor (Wood 1999 ). A second mechanism is skill-biased technological change. This technological change may have taken the form of increased imports of machines, office equipment, and other capital goods that are complementary to skilled labor (Acemoglu 2003 ). Liberalization may also have raised the demand for skilled labor, because it advantages companies that are operating more efficiently or closer to the technological frontier (Haltiwanger et al. 2004 ). Finally, trade liberalization has increased the prices of consumption goods (such as food and beverages) that have a relatively large share in the consumption bundle of the poor, and has decreased the prices of goods that are consumed in greater proportion by the rich (Porto 2006 ).

Finally, inequality may depend on the intensity of government regulation of financial, product, and labor markets. Stiglitz ( 2012 ) and Piketty ( 2014 ) argued that business and labor regulations are necessary for assuring minimal standards of living through minimum wage and health regulations. Minimum wages and other labor market regulations such as the right to be represented by unions strengthen the bargaining power of employees, raising average wages. This enables a large part of the population to gather adequate savings to deal with economic shocks. Liberalization may also lead to unequal access to the financial market (World Bank 2006 ). Fast liberalization and privatization allow powerful insiders to gain control over state banks (Stiglitz 2002 ). Important product market institutions that provide opportunities to the poor are antitrust legislation, good infrastructure and low transportation costs, and supply of information (for example by internet connections in rural areas) (World Bank 2006 ).

Based on this discussion, we state five hypotheses:

Fiscal freedom increases income inequality.

High quality of legal system and protection of property rights decreases income inequality.

Access to sound money decreases income inequality.

Trade openness increases income inequality.

Freedom from regulation of labor, product, and capital markets increases income inequality.

2.2 Income Inequality and Life Satisfaction

Although there is a quickly-increasing volume of literature about happiness in general, only a few researchers have investigated its relationship to income inequality. First of all, in a theoretical exercise, Baggio and Papyrakis ( 2014 ) found that the type of growth (pro-poor, pro-middle incomes, pro-rich) determines the impact of income (growth) on subjective well-being, suggesting an impact of inequality not only directly, but also through growth. Overall with respect to the direct effect, previous studies indicate that income inequality decreases life satisfaction. Footnote 1 Oshio and Kobayashi ( 2010 ) found that inequality has a strong negative impact on happiness. However, the magnitude of the negative effect varies for different population groups. For example, for females and young people, the effects are stronger than for other groups. Verme ( 2011 ) found that the measure of inequality is important, and after taking account of the variations in the measurement of inequality, he found that inequality has a robust negative and significant impact on life satisfaction. Schneider ( 2012 ) found that the influence of income inequality on life satisfaction depends on cultural perceptions and social-economic preferences. If income inequality is perceived as representing high potential for social mobility, then it might have a positive effect on life satisfaction. Thus Schneider ( 2012 ) empirically confirmed the meritocracy argument, one of the central explanations for toleration of high inequality. If, however, a society considers inequality to reflect social distance, the effect on life satisfaction will be negative. This line of argument is related to the finding by Luttmer ( 2005 ) that relative consumption is an important aspect of well-being, that should not be ignored and has a negative impact in addition to the influence of absolute consumption. Finally, Hajdu and Hajdu ( 2014 ) found that income redistribution leads to increased well-being.

Apart from these papers on income inequality and life satisfaction, there is a significant amount of literature providing indirect evidence of the negative relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction by linking income inequality to various mental problems and health. The most influential source is Wilkinson and Pickett ( 2010 ), who showed that inequality negatively affects both physical and mental health in a variety of ways. A major problem with their work is that they mostly based it on correlation patterns, but have not investigated the assumed causal relationship (Simic 2012 ). Sturm and Gresenz ( 2002 ), after giving a strong theoretical argumentation, showed empirically how chronic medical conditions and mental ill-health can be explained through income inequality. Kahn et al. ( 2000 ) established the link between income inequality and poor maternal health. The psychological dimensions of inequality have also been elaborated on by Lerner ( 2006 ), describing how working-class America is becoming increasingly disillusioned and frustrated about life.

Besides affecting mental health of individuals, inequality may also lower the quality of the social environment in which individuals live, which is reflected in crime figures and lack of trust. The IMF has published several reports that warned against the presumed negative social impact of inequality in the long run (Berg and Ostry 2011 ; Bastagli et al. 2012 ; Ostry et al. 2014 ). Similar conclusions were found by OECD ( 2012 ). All of these papers argued that the social effects of inequality are enormous, although empirical research on causal links between inequality and a variety of variables has been limited and ambiguous. Helliwell et al. ( 2009 ) found that the social environment is twice as important for happiness as income. Elgar and Aitken ( 2011 ) emphasized that inequality on a micro-scale leads to more violent crime. Wilkinson and Pickett ( 2009 ) presented evidence for income inequality explaining social dysfunction, whereas income level or other material standards do not. They also found that the national level of inequality is more important than regional inequality, which suggests that national trends and policies are crucial to the level of inequality and its impact on society. Finally, inequality may also reduce happiness by lowering trust. For example, Oishi et al. ( 2011 ) found that income inequality leads to a lack of trust. They also found that the impact differs for different income groups, and that it is strongest for the lowest income quintile.

Based on this literature overview, we state the following hypothesis:

Income inequality reduces average life satisfaction.

2.3 Overall Conceptual Model

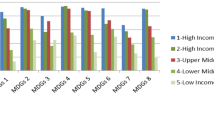

Based on Sects. 2.1 and 2.2 , the model that is used can be expressed by Fig. 1 .

Conceptual model representing hypotheses for determinants of income inequality and life satisfaction

Mathematically, the model can be described by the following equations:

LS denotes life satisfaction, II income inequality, FF fiscal freedom, PPR protection of property rights, SM sound money, FT free trade and FR freedom from regulation. V j and W j denote time variant control variables for life satisfaction and income inequality respectively. X j denote time invariant control variables for life satisfaction and Z j time invariant control variables for income inequality. The indices i and t denote country and year.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 data sources and measurement.

In order to test the model, we used a cross-country panel analysis for a period from 1990 till 2014. The dataset used for conducting the empirical analysis was constructed using different sources, including Veenhoven’s world database of life satisfaction, the World Bank, the Fraser Institute and the Heritage Foundation. Based on these sources, we constructed a sample of 21 OECD countries, for which all variables are available that we will use throughout our analysis (Table 1 ).

The data for life satisfaction came from Veenhoven’s World Database of life satisfaction. Life satisfaction was measured as a grade on a scale of 0–10 as an answer to the simple survey question “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?”. Our focus on OECD countries somewhat reduces the range and standard deviation in life satisfaction, because OECD countries have a relatively high life satisfaction. However, the range (5.5–8.5, SD = 0.65) is still quite substantial. An analysis of life satisfaction for all countries in the world shows that 8.5 is the maximum for all countries, whereas 66% of all countries have a life satisfaction score higher than 5.50 (SD = 1.40).

The most common measure for income inequality is the Gini-coefficient that calculates inequality over the complete range of the income distribution, usually after taxes. Using the Solt database, we tested both for gross Gini and for net Gini coefficients. Theoretically, one would expect that the net Gini coefficient is more relevant than the gross Gini coefficient as a mediator in the relationship between economic freedom and life satisfaction. Our focus on OECD countries also reduces the range and SD in income inequality. For example, whereas the gross Gini coefficient ranges from 32.1 to 56.6 in our sample (SD = 4.3), the range becomes 24.7–74.3 (SD = 10.1) when the sample is extended to all countries in the world (for which such data are available). Comparing the standard deviations, the focus on OECD countries thus reduces the standard deviation for life satisfaction (from 1.40 to 0.65) in equal measure as it does reduce the standard deviation in income inequality (from 10.1 to 4.3).

The data for economic freedom were taken from the Fraser Institute and the Heritage Foundation that provide alternative estimates of the five dimensions of economic freedom that we include in our analysis. Footnote 2 As the measurement of institutional characteristics is inherently difficult (Dawson 1998 ), we tested the convergence between the indicators of the Fraser Institute and Heritage Foundation for each of the dimensions of economic freedom separately. Table 2 shows that for Fiscal freedom, the Protection of property rights, and Freedom from regulation, the Spearman correlation coefficient is very significant and strong. For Free trade the coefficient is still very significant but rather low. For Sound Money, the coefficient is neither significant nor strong. This is probably caused by the different indicators that Fraser Institute and Heritage foundation use to measure Sound Money (see Appendix 1 ). Besides (average) inflation (which is used by both institutes), the Heritage Foundation uses price controls (which is not used by Fraser institute), whereas the Fraser institute uses money growth, standard deviation of inflation and freedom to own foreign currency accounts (which are not used by the Heritage Foundation). Also the weighting of these indicators is very different between the Fraser Institute and the Heritage foundation.

3.2 Control Variables

Income per capita is an important determinant of life satisfaction, because it raises consumption, health, education level, and employment (Dolan et al. 2008 ; Frey and Stutzer 2001 ; Di Tella and MacCulloch 2010 ). Although research by Easterlin et al. ( 2011 ) and Di Tella and MacCulloch ( 2010 ) has cast doubt on the long term effect of income per capita on subjective well-being, Stevenson and Wolfers ( 2008 ) and Fischer ( 2008 ) found a positive correlation between subjective well-being and income that is significant and robust among countries, within countries, and across time. Therefore, we included income per capita as a control variable in the regression analysis of life satisfaction. GDP per capita was measured in purchasing power parity at constant, international dollars. In order to deal with the non-linearity of the relationship between life satisfaction and income per capita, the natural logarithm of GDP per capita was used (lnGDPcap) (Graafland and Compen, 2015 ). Diener et al. ( 2010 ) found that life evaluation measures for well-being are equally dependent on income per capita for poor and rich countries, once the logarithm of income per capita (instead of the absolute income per capita) is used.

Besides income per capita, we included several other control variables that are often used in research in life satisfaction (Ovaska and Takashima 2006 ; for an extensive list, see also Bjørnskov et al. 2008 ) and for which data are available during the estimation period. Time variant controls include inflation, unemployment rate, female participation rate and child mortality. Time invariant controls include religion (Christianity, Muslim), political rights, civil liberty, monarchy, and average temperature.

For income inequality, we used a set of control variables that are common in research relating economic freedom to income inequality (see Bennett and Nikolaev 2014 ). Based on their list of control variables, we included foreign direct investment, age structure of population, urbanization rate, share of the labor force employed in the industrial sector and openness as time variant controls. In addition, we looked for other variables in recent literature such as part time work as time variant control and religion, political rights, civil liberty and a regional dummy for Scandinavian countries as time invariant controls (Leigh 2006 ; Steijn and Lancee 2011 ; Bergh and Bjørnskov 2014 ; Barone and Mocetti 2016 ).

3.3 Econometric Issues