- Study protocol

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2019

The impact of racism on the future health of adults: protocol for a prospective cohort study

- James Stanley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8572-1047 1 ,

- Ricci Harris 2 ,

- Donna Cormack 2 ,

- Andrew Waa 2 &

- Richard Edwards 1

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 346 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

236k Accesses

21 Citations

266 Altmetric

Metrics details

Racial discrimination is recognised as a key social determinant of health and driver of racial/ethnic health inequities. Studies have shown that people exposed to racism have poorer health outcomes (particularly for mental health), alongside both reduced access to health care and poorer patient experiences. Most of these studies have used cross-sectional designs: this prospective cohort study (drawing on critical approaches to health research) should provide substantially stronger causal evidence regarding the impact of racism on subsequent health and health care outcomes.

Participants are adults aged 15+ sampled from 2016/17 New Zealand Health Survey (NZHS) participants, sampled based on exposure to racism (ever exposed or never exposed, using five NZHS questions) and stratified by ethnic group (Māori, Pacific, Asian, European and Other). Target sample size is 1680 participants (half exposed, half unexposed) with follow-up survey timed for 12–24 months after baseline NZHS interview. All exposed participants are invited to participate, with unexposed participants selected using propensity score matching (propensity scores for exposure to racism, based on several major confounders). Respondents receive an initial invitation letter with choice of paper or web-based questionnaire. Those invitees not responding following reminders are contacted for computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI).

A brief questionnaire was developed covering current health status (mental and physical health measures) and recent health-service utilisation (unmet need and experiences with healthcare measures). Analysis will compare outcomes between those exposed and unexposed to racism, using regression models and inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) to account for the propensity score sampling process.

This study will add robust evidence on the causal links between experience of racism and subsequent health. The use of the NZHS as a baseline for a prospective study allows for the use of propensity score methods during the sampling phase as a novel approach to recruiting participants from the NZHS. This method allows for management of confounding at the sampling stage, while also reducing the need and cost of following up with all NZHS participants.

Peer Review reports

Differential access to the social determinants of health both creates and maintains unjust and avoidable health inequities [ 1 ]. In New Zealand, these inequities are largely patterned by ethnicity, particularly for Māori (the indigenous peoples) and Pacific peoples, and intertwined with ethnic distributions of socioeconomic status [ 2 , 3 ]. In models of health, racism is recognised as a key social determinant that underpins systemic ethnic health and social inequities, as is evident in New Zealand and elsewhere [ 4 , 5 ].

Racism can be understood as an organised system based on the categorisation and ranking of racial/ethnic groups into social hierarchies whereby ethnic groups are assigned differential value and have differential access to power, opportunities and resources, resulting in disadvantage for some groups and advantage for others [ 4 , 6 ]. Historical power relationships underpin systems of racism [ 7 ], which in New Zealand relates specifically to our colonial history and ongoing colonial processes [ 8 ].

Racism can be expressed at structural and individual levels, with several taxonomies describing different levels of racism. Institutionalised racism, for example, has been defined as, “the structures, policies, practices, and norms resulting in differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race[/ethnicity]” (p. 10) [ 6 ]. In contrast, personally-mediated racism has been defined as, “prejudice and discrimination, where prejudice is differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intents of others by ‘race[/ethnicity],’ and discrimination is differential actions towards others by ‘race[/ethnicity]’” (p. 10) [ 6 ].

The multifarious expressions of racism can affect health via several recognised direct and indirect pathways. Indirect pathways include differential access to societal resources and health determinants by race/ethnicity, as evidenced by long-standing ethnic inequities in income, education, employment and living standards in New Zealand, with subsequent impacts on living environments and exposure to risk and protective factors [ 4 , 6 , 9 , 10 ]. At the individual level, experience of racism can affect health directly through physical violence and stress pathways, with negative psychological and physiological impacts leading to subsequent mental and physical health consequences. In addition, racism influences healthcare via institutions and individual health providers, leading to ethnic inequities in access to and quality of care. For example, ethnic disparities in socioeconomic status can indirectly result in differential access to care, while health provider ethnic bias can influence the quality and outcomes of healthcare interactions [ 11 ].

There has been considerable recent growth in research supporting a direct link between experience of racism and health. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis summarised the evidence for direct links between self-reported personally-mediated racism and negative physical and mental health outcomes [ 12 ], with the strongest effect sizes demonstrated for mental health. Related work has also shown that experience of racial discrimination is associated with other adverse health outcomes and preclinical indicators of disease and health risk across various ethnic groups and countries, including in New Zealand [ 9 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Experience of racism has also been linked to a range of negative health care-related measures [ 16 ].

However, most studies have used cross-sectional designs: very few of the articles in a recent systematic review [ 12 ] used prospective or longitudinal designs ( n = 30, 9% of total, including multiple articles from some studies), limiting our ability to draw strong causal conclusions as the direction of causality cannot be determined when racism exposure and health outcomes are measured at the same time. Additionally, cross-sectional studies may give biased estimates of the magnitude of association between experience of racism and health: for example, bias may occur if experience of ill health (outcome) increases reporting or perception of racism (exposure) [ 12 ]. This is suggested by meta-analyses where effect sizes for the association between racism and mental health were larger for cross-sectional compared to longitudinal studies [ 12 ]. Longitudinal research on the effects of racism has been particularly limited with respect to physical health outcomes and measures of healthcare access and quality [ 12 , 16 ]. Finally, existing prospective studies have largely been restricted to quite specific groups (e.g. adolescents, females, particular ethnic groups), with a limited number of studies undertaken at a national population level and few with sufficient data to explore the impact of racism on the health of Indigenous populations [ 12 ].

In New Zealand, reported experience of racism is substantially higher among Māori, Asian and Pacific ethnic groupings compared to European [ 3 , 17 ]. In our own research, we have examined cross-sectional links between reported experience of racism and various measures of adult health in New Zealand using data from the New Zealand Health Survey (NZHS), an annual national survey by the Ministry of Health including ~ 13,000 adults per annum [ 2 , 18 , 19 ]. In these studies [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 22 ] we have shown that both individual experience of racism (e.g. personal attacks or unfair treatment) and markers of structural racism (deprivation, other socioeconomic indicators) are independently associated with poor health (mental health, physical health, cardiovascular disease), health risks (smoking, hazardous alcohol consumption) and healthcare experience and use (screening, unmet need and negative patient experiences). Other New Zealand researchers have reported similar findings including studies among older Māori [ 23 ], adolescents [ 24 ], and for maternal and child health outcomes [ 25 ]. However, evidence from New Zealand prospective studies is still limited. The NZ Attitudes and Values study showed that, among Māori, experience of racism was negatively linked to subsequent wellbeing [ 26 ], and the Growing Up in New Zealand study reported that maternal experience of racism (measured antenatally) was linked to a higher risk of postnatal depression among Māori, Pacific and Asian women [ 27 ].

While empirical evidence of the links between racism and health is growing in New Zealand, it remains limited in several areas. There is consistent evidence from cross-sectional studies for the hypothesis that racism is associated with poorer health and health care. This study seeks to build on existing research to provide more robust causal evidence using a prospective design that helps to rule out reverse causality, in order to inform policy and healthcare interventions.

Theoretical and conceptual approaches

Addressing racism as a health determinant is intrinsically linked to addressing ethnic health inequities. In New Zealand, Māori health is of special relevance given Māori rights under the Treaty of Waitangi [ 28 ] and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People [ 29 ], and in recognition of the inequities for Māori across most major health indicators [ 28 ]. We recognise the direct significance of this project to Māori and understand racism in its broader sense as underpinning our colonial history with ongoing contemporary manifestations and effects [ 8 ]. As such, our work is informed by critical approaches to health research that are explicitly concerned with understanding inequity and transforming systems and structures to achieve the goal of health equity. This includes decolonising and transformative research principles [ 30 ] that influence our approach to the research question, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and translation of research findings. The team includes senior Māori researchers as well as advisors with experience in Māori health research and policy.

Aims and research questions

The overall aim is to examine the relationship between reported experience of racism and a range of subsequent health measures. The specific objectives are:

To determine whether experience of racism leads to poorer mental health and/or physical health.

To determine the impact of racism on subsequent use and experience of health services.

Study design

The proposed study uses a prospective cohort study design. Respondents from the 2016/17 New Zealand Health Survey [ 2 , 18 , 19 ] (NZHS) provide the source of the follow-up cohort sample and the NZHS provides baseline data. The follow-up survey will be conducted between one and two years after respondents completed the NZHS. Using the NZHS data as our sampling frame provides access to exposure status (experience of racism), along with data on a substantial number of covariates (including age, gender, and socioeconomic variables) allowing us to select an appropriate study cohort for answering our research questions. Participant follow-up will be conducted by a multi-modality survey (mail, web and telephone modalities).

This study explores the impact of racism on health in the general NZ adult population (which is the target population of the NZHS that forms the baseline of the study).

Participants

Participants were selected from adult NZHS 2016/17 interviewees ( n = 13,573, aged 15+ at NZHS interview) who consented to re-contact for future research within a 2 year re-contact window (92% of adult respondents). The NZHS is a complex-sample design survey with an 80% response rate for adults [ 18 ] and oversampling of Māori, Pacific, and Asian populations (who experience higher levels of racism), which facilitates studying the impact of racism on subsequent health status. Participants who had consented to re-contact ( n = 12,530) also needed to have contact details recorded and sufficient data on exposures/confounders to be included in the sampling frame ( n = 11,775, 93.9% of consenting adults). All invited participants will be aged at least 16 at the time of follow-up, as at least one year will have passed since participation in the NZHS (where all participants were aged at least 15).

Exposure to racism was determined from the five previously validated NZHS items [ 31 ] asked of all adult respondents (see Table 1 ) about personal experience of racism across five domains (verbal and physical attack; unfair treatment in health, housing, or work). Response options for each question cover recent exposure (within the past 12 months), more historical exposure (> 12 months ago), or no exposure to racism.

Identification of exposed and unexposed individuals

Individuals were classified as exposed to racism if they answered “yes” to any question in Table 1 , in either timeframe (recent or historical: referred to as “ever” exposure). This allows for analysis restricted to the nested subset of individuals reporting recent exposure to racism (past 12 months) and those only reporting more historical exposure (> 12 months ago). The unexposed group comprised all individuals answering “No” to all five domains of experience of racism. We selected all exposed individuals for follow-up, along with a matched sample of unexposed individuals. Individuals missing exposure data were explicitly excluded.

Matching of exposed and unexposed individuals

To address potential confounding, we used propensity score matching methods in our sampling stage to remove the impact of major confounders (as measured in the NZHS) of the causal association between experience of racism and health outcomes. Propensity score methods are increasingly used in observational epidemiology as a robust method for dealing with confounding in the analysis stage [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ] and have more recently been considered as a useful approach for secondary sampling of participants from existing cohorts for subsequent follow up [ 37 ].

All exposed NZHS respondents will be invited into the follow-up survey. To find matched unexposed individuals, potential participants were stratified based on self-reported ethnicity (Māori, Pacific, Asian, European and Other; using prioritised ethnicity for individuals identifying with more than one grouping) [ 38 ] and then further matched for potential sociodemographic and socioeconomic confounders using propensity score methods [ 39 , 40 ]. Stratification by ethnicity reflects the differential prevalence of racism by ethnic group, and furthermore allows ethnically-stratified estimates of the impact of racism [ 22 ].

Propensity scores were modelled using logistic regression for “ever” exposure to racism based on major confounder variables of the association between racism and poor health (Table 2 ), with modelling stratified by ethnic group. Selection of appropriate confounders was based on past work using cross-sectional analysis of the 2011/12 NZHS (e.g. [ 21 , 22 ]) and the wider literature that informed the conceptual model for the project. Some additional variables were considered for inclusion in the matching process but were removed prior to finalisation (details in Table 2 ).

Within each ethnic group stratum, exposed individuals were matched with unexposed individuals (1:1 matching) based on propensity scores to make these two groups approximately exchangeable (confounders balanced between exposure groups). The matching process [ 41 ] used nearest neighbour matching as implemented in MatchIt [ 42 ] in R 3.4 (R Institute, Vienna, Austria). As the propensity score modelling is blind to participants’ future outcome status, the final propensity score models were refined using just the baseline NZHS data to achieve maximal balance of confounders between exposure groups, without risking bias to the subsequent primary causal analyses [ 39 ]. Balance between groups was then checked on all matching variables prior to finalisation of the sampling lists.

Questionnaire development

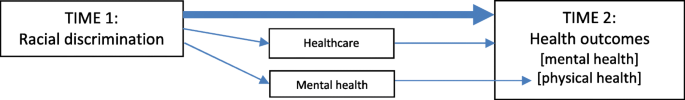

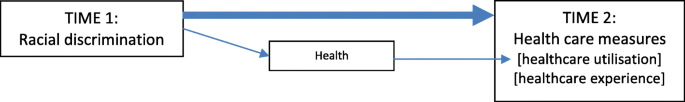

Development of the follow-up questionnaire was informed by a literature review and a conceptual model (Figs. 1 and 2 ) of the potential pathways from racism to health outcomes (Fig. 1 ) and health service utilisation (Fig. 2 ) [ 4 , 10 , 16 , 43 , 44 ]. The literature review focussed on longitudinal studies of racism and health among adolescents and adults that included health or health service outcomes. The literature review covered longitudinal studies post-dating the 2015 systematic review by Paradies et al. [ 12 ], using similar search terms for papers between 2013 and 2017 indexed in Medline and PubMed databases, alongside additional studies from systematic reviews [ 12 , 16 ].

Potential pathways between racism and health outcomes. Direct pathway: Main arrow represents the direct biopsychosocial and trauma pathways between experience of racial discrimination (Time 1) and negative health outcomes (Time 2) Indirect pathways: Racial discrimination (Time 1) can impact negatively on health outcomes (Time 2) via healthcare pathways (e.g. less engagement, unmet need). Racial discrimination (Time 1) can impact negatively on physical health outcomes (Time 2) via mental health pathways

Potential pathways between racism and healthcare utilisation outcomes. Main pathway: Main arrow represents the pathway between experience of racial discrimination (Time 1) and negative healthcare measures (Time 2), via negative perceptions and expectations of healthcare (providers, organisations, systems) and future engagement. Secondary pathway: Racial discrimination (T1) can impact negatively on healthcare (Time 2) via negative impacts on health increasing healthcare need

We used several criteria for considering and prioritising variables for the questionnaire. The conceptual model also informed prioritisation of variables for the questionnaire. For outcome measures, these included: alignment with study aims and objectives; existing evidence of a relationship between racism and outcome; New Zealand evidence of ethnic inequities in outcome; previous cross-sectional relationships between racism and outcome in New Zealand data; availability of baseline measures (for health outcomes); plausibility of health effects manifesting within a 1–2 year follow-up period; and data quality (e.g. validated measures, low missing data, questions suitable for multimodal administration). Mediators and confounders were considered for variables not available in the baseline NZHS survey, as was recent experience of racism (following the NZHS interview) to provide additional measurement of exposure to recent racism. A final consideration for prioritising items for inclusion was keeping the length of the questionnaire short in order to maximise response rates (while being able to fully address the study aims). The questionnaire was extensively discussed by the research team and reviewed by the study advisors prior to finalisation.

Table 3 summarises the outcome measures by topic domain and original source (with references). The final questionnaire content can be found in the Additional file 1 , and includes: health outcome measures of mental and physical health (using SF12-v2 and K10 scales); health service measures (unmet need, satisfaction with usual medical centre, experiences with general practitioners); experience of racism in the last 12 months (adapted from items in the NZHS); and variables required to restrict data (e.g. having a usual medical centre, type of centre, having a General Practitioner [GP] visit in the last 12 months) or potential confounder and mediator variables not available at baseline (e.g. number of GP visits).

Recruitment and data collection

Recruitment is currently underway. The sampling phase provided a list of potential participants for invitation, and recruitment for the follow-up survey uses the contact details from the NZHS interview (physical address, mobile/landline telephone, and email address if available). Recruitment will take place over three tranches to (1) manage fieldwork capacity and (2) allow tracking of response rates and adaptation of contact strategies if recruitment is sub-optimal.

To maximise response rates, we chose to use a multi-modal survey [ 45 ]. Participants are invited to respond by a paper questionnaire included with the initial invitation letter (questionnaire returned by pre-paid post), by self-completed online questionnaire, or by computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI, on mobile or landline.) A pen is included in the study invitation to improve initial engagement with the paper-based survey [ 46 ]. Participants completing the survey are offered a NZ$20 gift card to recognise their participation. The contact information contains instructions for opting out of the study.

Those participants not responding online or by post receive a reminder postcard mailed out two weeks after the initial letter, containing a link to the web survey and a note that the participant will be contacted by telephone in two weeks’ time.

Two weeks after the reminder postcard (four weeks post-invitation) remaining non-respondents are contacted using CATI processes. For those with mobile phone numbers or email addresses, a text (SMS) or email reminder is sent two days before the telephone contact phase. Once contact is made by telephone, the interviewer asks the participant to complete the survey over the telephone at that time or organises a subsequent appointment (interview duration approximately 15 min). Interviewers make up to seven telephone contact attempts for each participant, using all recorded telephone numbers. Respondents who decline to complete the full interview at telephone follow-up are asked to consider answering two priority questions (self-rated health and any unmet need for healthcare in the last 12 months: questions 1 and 8 in Table 3 and Additional file 1 ).

Past surveys conducted in NZ have frequently noted lower response rates and hence under-representation of Māori [ 47 , 48 ]. Drawing on Kaupapa Māori research principles, we are explicitly aiming for equitable response rates of Māori to ensure maximum power for ethnically stratified analysis. This involves providing culturally appropriate invitations and interviewers for participants, and actively monitoring response rates by ethnicity during data collection to allow longer and more frequent follow-up of Māori, Pacific and Asian participants if required [ 48 , 49 ]. The use of a multi-modal survey is also expected to minimise recruitment problems inherent to any single modality (e.g. lower phone ownership or internet access in some ethnic groups).

We have contracted an external research company to co-ordinate recruitment and data collection fieldwork under our supervision (covering all contact processes described here), which follows recruitment and data management protocols set by our research team.

Statistical analysis

Propensity score methods for the sampling stage are described above: this section focuses on causal analyses for health outcomes in the achieved sample. The sampling frame selects participants based on “ever” experience of racism, which is our exposure definition.

All analyses will account for both the complex survey sampling frame (weights, strata and clusters from the NZHS) and the secondary sampling phase (selection based on propensity scores). Complex survey data will be handled using software to account for these designs (e.g. survey package [ 50 ] in R); propensity scores will be handled in the main analysis by using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) combined with the sampling weights [ 51 ].

Linear regression methods will be used to compare change in continuous outcome measures (e.g. K10 score) by estimating mean score at follow-up, adjusted for baseline. Analysis of dichotomous categorical outcomes (e.g. self-rated health) will use logistic regression methods, again adjusted for baseline (for health outcomes). We will conduct analyses stratified by ethnic group to explore whether the impact of racism differs by ethnic group. Models will adjust for confounders included in creating the propensity scores (doubly-robust estimation) to address residual confounding not fully covered by the propensity score approach [ 52 ]. Analysis for other outcomes will use similar methods.

As we hypothesise that some outcomes (e.g. self-reported mental distress) will be more strongly influenced by recent experience of racism, we will also examine our main outcomes restricted to those only reporting historical (more than 12 months ago) or recent (last 12 months) racism at baseline. These historical and recent experience groups (and corresponding unexposed individuals) form nested sub-groups of the total cohort, and so analysis will follow the same framework outlined above. Experience of racism in the last 12 months (measured at follow-up) will be examined in cross-sectional analyses and in combination with baseline measures of racism to create a measure to examine the cumulative impact of racism on outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses

While the sampling invitation lists are based on matched samples, we have no control about specific individuals choosing to participate in the follow-up survey, and so the original matching is unlikely to be maintained in the achieved sample. We will conduct sensitivity analyses using re-matched data (based on propensity scores for those participating in follow-up) to allow for re-calibration of exposed and unexposed groups in the achieved sample.

To consider potential for bias due to non-response in our follow-up sample, we will compare NZHS 2016/17 cross-sectional data for responders and non-responders on baseline sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and baseline health variables.

Sample size

Based on NZHS 2011/12 responses, we anticipated a total pool of 2100 potential participants with “ever” experience of racism, with approximately 1100 expected to be Māori/Pacific/Asian ethnicity, and 10,000 with no report of racism (at least 2 unexposed per exposed individual in each ethnic group).

For the main analyses (based on “ever” experience of racism) we assumed a conservative follow-up rate of 40%, giving a final sample size of at least 840 exposed individuals. This response rate includes re-contact and agreement to participate, based on past experience recruiting NZHS participants for other studies and the relative length of the current survey questionnaire.

Initial projections (based on NZHS2011/12 data) indicated sufficient numbers of unexposed individuals for 1:1 matching based on ethnicity and propensity scores. This gives a feasible total sample size of n = 1680, providing substantial power for the K10 mental health outcome (standard deviation = 6.5: > 95% power to detect difference in change of 2 units of K10 between groups.) For the second main health outcome (change in self-rated health), this sample size will have > 85% power for a difference between 8% of those exposed to racism having worse self-reported health at follow-up (relative to baseline) compared to 5% of unexposed individuals.

For analyses of effects stratified by ethnicity, we expect > 95% power for Māori participants ( n = 280 each exposed and unexposed) for the K10 outcome (assumptions as above); change in self-rated health will have 80% power for a difference between 12% of exposed individuals having worse self-reported health at follow-up (relative to baseline) compared to 5% of unexposed individuals. Stratified estimates for Pacific and Asian groups will have poorer precision, but should still provide valid comparisons.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study involves recruiting participants who have already completed the NZHS interview (including questions on racial discrimination) The NZHS as conducted by the Ministry of Health has its own ethical approval (MEC/10/10/103) and participants are only invited onto the present study if they explicitly consented (at the time of completing the NZHS) to re-contact for future health research. The current study was reviewed and approved by the University of Otago’s Human Ethics (Health) Committee prior to commencement of fieldwork (reference: H17/094). Participants provided informed consent to participate at the time of completing the follow-up survey depending on response modality: implicitly through completion and return of the paper survey which stated “By completing this survey, you indicate that you understand the research and are willing to participate” (see Additional file 1 : a separate written consent document was not required by the ethics committee); in the online survey by responding “yes” to a similarly worded question that they understood the study and agreed to take part (recorded as part of data collection, and participation could not continue unless ticked), or by verbal consent in a similar initial question in the telephone interview (since written consent could not be collected in this setting). These consent methods were approved by the reviewing Ethics committee [ 53 ]. Ethical approval for the study included using the same consent processes for those participants aged 16 to 18 as for older participants.

This study will contribute robust evidence to the limited national and international literature from prospective studies on the causal links between experience of racism and subsequent health. The use of the NZHS as the baseline for the prospective study capitalises on the inclusion of racism questions in that survey to provide a unique and important opportunity to build on and substantially strengthen the current evidence base for the impact of racism on health using data spanning the entire New Zealand adult population. In addition, our use of propensity scores in the sampling phase is a novel approach to prospective recruitment of participants from the NZHS. This approach should manage confounding while reducing the need (and cost) of following up all NZHS participants, without compromising the internal validity of the results. The novel methods developed for using the NZHS as the base for a prospective cohort study will have wider application to other health priority areas. One general limitation of this approach is that baseline data (for both propensity score development and baseline health measures) is limited to the data captured in the existing larger survey. We anticipate that this study will assist in prioritising racism as a health determinant and inform the development of anti-racism interventions in health service delivery and policy making.

Current stage of research

Funding for this project began October 1st 2017. The first set of respondent invitations was mailed out on July 12th 2018; fieldwork for the final tranche of invitations was underway at the time of submission and is expected to be completed by 31 December 2018. Analysis and reporting will take place in mid-to-late 2019.

Abbreviations

Computer Assisted Telephone Interview

General Practitioner

General Social Survey

Index of Multiple Deprivation

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weights

- New Zealand

New Zealand Deprivation Index

New Zealand Health Survey

12/36-Item Short Form Survey

short message service

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through actions on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Google Scholar

Ministry of Health. Annual Update of Key Results 2016/17: New Zealand Health Survey 2017 [Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2016-17-new-zealand-health-survey . accessed 13/09/2018].

Ministry of Social Development. The Social Report 2016: Te pūrongo oranga tangata. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development; 2016.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340 .

Reid P, Robson B. Understanding health inequities. In: Robson B, Harris R, editors. Hauora: Maori standards of health IV a study of the years 2000–2005. Wellington: Te Ropu Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pomare; 2007. p. 3–10.

Jones C. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon. 2002;50:7–22.

Article Google Scholar

Garner S. Racisms: An introduction. London/Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2010.

Book Google Scholar

Becares L, Cormack D, Harris R. Ethnic density and area deprivation: neighbourhood effects on Maori health and racial discrimination in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2013;88:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.007 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Paradies YC. Defining, conceptualizing and characterizing racism in health research. Crit Public Health. 2006;16(2):143–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590600828881 .

Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–44. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544 .

Jones CP. Invited commentary: "race," racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):299–304; discussion 05-6.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:407–40. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728 .

Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, et al. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:130–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxp009 .

Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ben J, Cormack D, Harris R, et al. Racism and health service utilisation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189900. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189900 published Online First: 2017/12/19.

Harris R, Cormack D, Tobias M, et al. The pervasive effects of racism: experiences of racial discrimination in New Zealand over time and associations with multiple health domains. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(3):408–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.004 .

Ministry of Health. Methodology report 2016/17: New Zealand health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2017.

Ministry of Health. Content guide 2016/17: New Zealand health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2017.

Harris R, Cormack D, Tobias M, et al. Self-reported experience of racial discrimination and health care use in New Zealand: results from the 2006/07 New Zealand health survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):1012–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300626 .

Harris RB, Cormack DM, Stanley J. Experience of racism and associations with unmet need and healthcare satisfaction: the 2011/12 adult New Zealand health survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12835 published Online First: 2018/10/09.

Harris RB, Stanley J, Cormack DM. Racism and health in New Zealand: prevalence over time and associations between recent experience of racism and health and wellbeing measures using national survey data. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196476 published Online First: 2018/05/04.

Dyall L, Kepa M, Teh R, et al. Cultural and social factors and quality of life of Maori in advanced age. Te puawaitanga o nga tapuwae kia ora tonu - life and living in advanced age: a cohort study in New Zealand (LiLACS NZ). N Z Med J. 2014;127(1393):62–79.

PubMed Google Scholar

Crengle S, Robinson E, Ameratunga S, et al. Ethnic discrimination prevalence and associations with health outcomes: data from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of secondary school students in New Zealand. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-45 .

Thayer ZM, Kuzawa CW. Ethnic discrimination predicts poor self-rated health and cortisol in pregnancy: insights from New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.003 .

Stronge S, Sengupta NK, Barlow FK, et al. Perceived discrimination predicts increased support for political rights and life satisfaction mediated by ethnic identity: a longitudinal analysis. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2016;22(3):359–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000074 .

Becares L, Atatoa-Carr P. The association between maternal and partner experienced racial discrimination and prenatal perceived stress, prenatal and postnatal depression: findings from the growing up in New Zealand cohort study. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0443-4 .

Robson B, Harris R, editors. Hauora : Maori standards of health IV : a study of the years 2000–2005. Wellington: Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare; 2007.

UN General Assembly. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly 2007. Available from: https://undocs.org/A/RES/61/295 . Accessed 1 Nov 2018.

Smith L. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. 2nd ed. London and New York: Zed Books; 2012.

Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, et al. Racism and health: the relationship between experience of racial discrimination and health in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(6):1428–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.009 .

Sturmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, et al. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(5):437–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004 .

Luo Z, Gardiner JC, Bradley CJ. Applying propensity score methods in medical research: pitfalls and prospects. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(5):528–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558710361486 .

Weitzen S, Lapane KL, Toledano AY, et al. Principles for modeling propensity scores in medical research: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(12):841–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.969 .

Shah BR, Laupacis A, Hux JE, et al. Propensity score methods gave similar results to traditional regression modeling in observational studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):550–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.016 .

Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313 published Online First: 2010/09/28.

Stuart EA, Ialongo NS. Matching methods for selection of subjects for follow-up. Multivariate Behav Res. 2010;45(4):746–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2010.503544 [published Online First: 2011/01/12].

Ministry of Health. Ethnicity Data Protocols Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/hiso-10001-2017-ethnicity-data-protocols-v2.pdf . Accessed 1 Nov 2018.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 .

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv. 2008;22(1):31–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x .

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, et al. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal. 2017;15(03):199–236. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl013 .

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, et al. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42(8):1–28.

Sarnyai Z, Berger M, Jawan I. Allostatic load mediates the impact of stress and trauma on physical and mental health in indigenous Australians. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24(1):72–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215620025 published Online First: 2015/12/10.

Kaholokula J. Mauli Ola: Pathways toward Social Justice for Native Hawaiians. Townsville: LIME Network Conference; 2015.

Fowler FJ, Roman AM, Mahmood R, et al. Reducing nonresponse and nonresponse error in a telephone survey: an informative case study. J Survey Stat Methodol. 2016;4(2):246–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jssam/smw004 .

White E, Carney PA, Kolar AS. Increasing response to mailed questionnaires by including a pencil/pen. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):261–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi194 [published Online First: 2005/06/24].

Fink JW, Paine SJ, Gander PH, et al. Changing response rates from Maori and non-Maori in national sleep health surveys. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1328):52–63.

Paine SJ, Priston M, Signal TL, et al. Developing new approaches for the recruitment and retention of Indigenous participants in longitudinal research: Lessons from E Moe, Māmā: Maternal Sleep and Health in Aotearoa/New Zealand. MAI Journal: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship. 2013;2(2):121–32.

Selak V, Crengle S, Elley CR, et al. Recruiting equal numbers of indigenous and non-indigenous participants to a 'polypill' randomized trial. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-44 .

Lumley T. survey: analysis of complex survey samples v3.32 2017 [R package]. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/index.html . Accessed 1 Nov 2018.

Lenis D, Nguyen TQ, Dong N, et al. It's all about balance: propensity score matching in the context of complex survey data. Biostatistics. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxx063 [published Online First: 2018/01/03].

Funk MJ, Westreich D, Wiesen C, et al. Doubly robust estimation of causal effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(7):761–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq439 [published Online First: 2011/03/10].

National Ethics Advisory Committee. Ethical guidelines for observational studies: observational research, audits and related activities. Revised edition. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012.

Atkinson J, Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep2013 index of deprivation. Dunedin: University of Otago; 2014.

Exeter DJ, Zhao J, Crengle S, et al. The New Zealand indices of multiple deprivation (IMD): a new suite of indicators for social and health research in Aotearoa, New Zealand. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181260 [published Online First: 2017/08/05].

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–76.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Fleishman JA, Selim AJ, Kazis LE. Deriving SF-12v2 physical and mental health summary scores: a comparison of different scoring algorithms. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(2):231–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9582-z .

Bastos JL, Harnois CE, Paradies YC. Health care barriers, racism, and intersectionality in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:209–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.010 [published Online First: 2017/05/16].

Australian Bureau of Statistics. General Social Survey 2014: Household questionnaire. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2014.

Ministry of Health. The New Zealand Health Survey: Content Guide and questionnaires 2011–2012 Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012 [Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-health-survey-content-guide-and-questionnaires-2011-2012 . accessed 31/10/2016 2016].

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Ministry of Health’s New Zealand Health Survey Team for facilitating access to the NZHS data and respondent lists, and for help with constructing the questionnaire (including providing the Helpline contact template).

We would also like to acknowledge the expertise and input of our project advisory team: Natalie Talamaivao (Senior Advisor, Māori Health Research, Ministry of Health), Associate Professor Bridget Robson (Director, Eru Pōmare Māori Health Research Centre, University of Otago, Wellington), and Dr. Sarah-Jane Paine (Senior Research Fellow, University of Auckland and University of Otago, Wellington). Thanks also to Ms. Ruruhira Rameka (Eru Pōmare Māori Health Research Centre, University of Otago, Wellington) for providing administrative support. Research New Zealand was contracted to undertake the data collection and other fieldwork for the follow-up survey.

This project was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRC 17–066). The funding body approved the study but has no further role in the study design or outputs from the study.

Availability of data and materials

Data from the follow-up study is not available to other researchers as participants did not provide their consent for data sharing. The NZHS 2016/17 data used as the baseline for the study described in this protocol is available to approved researchers subject to the New Zealand Ministry of Health’s Survey Microdata Access agreement https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/national-collections-and-surveys/surveys/access-survey-microdata .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington, 23a Mein Street, Newtown, Wellington, New Zealand

James Stanley & Richard Edwards

Eru Pōmare Māori Health Research Centre, University of Otago, Wellington, 23a Mein Street, Newtown, Wellington, New Zealand

Ricci Harris, Donna Cormack & Andrew Waa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JS and RH initiated the project and are co-principal investigators of the study, and jointly led writing of the grant application and this protocol paper. JS designed the sampling plan, led the development of the contact protocol, led the development of the statistical analysis plan, contributed to revising the questionnaire, and is guarantor of the paper. RH designed the questionnaire, contributed to development of the sampling and contact protocol, and co-led the statistical analysis plan. DC led the conceptual plan with support from RH. AW and RE contributed to the contact protocol. DC, AW and RE all contributed to writing the grant application, revising the questionnaire and sampling plans, and revising the draft protocol paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to James Stanley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The follow-up study protocol and questionnaire were approved by the University of Otago’s Human Ethics (Health) Committee prior to commencement of fieldwork (reference: H17/094). The NZHS has its own ethical approval as granted to the New Zealand Ministry of Health (NZ Multi-Region Ethics Committee, MEC/10/10/103), and consent for re-contact was gained from participants at the time of their NZHS interview. Participants provided informed consented to participate at the time of completing the follow-up survey: implicitly through completion and return of the paper survey which stated “By completing this survey, you indicate that you understand the research and are willing to participate”; in the online survey by responding “yes” to a similarly worded question that they understood the study and agreed to take part, or by verbal consent in a similar initial question in the telephone interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JS, RH, DC, AW, and RE report funding from the Health Research Council of New Zealand to complete this work. JS and RH report personal fees from the Health Research Council of New Zealand for service as external members on committees (neither are employees of the HRC), outside the scope of the current work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Questionnaire used in follow-up survey. (PDF 919 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Stanley, J., Harris, R., Cormack, D. et al. The impact of racism on the future health of adults: protocol for a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 19 , 346 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6664-x

Download citation

Received : 28 November 2018

Accepted : 15 March 2019

Published : 28 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6664-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Prospective cohort study

- Health service utilisation

- Health inequities

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Interviews

- Research Curations

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Submission Site

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Consumer Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, a call for race in the marketplace scholarship, demystifying race in the marketplace, what is rim consumer research, guidance for conducting race-relevant research, evolving an understanding of race in consumer research, author notes.

- < Previous

Race in Consumer Research: Past, Present, and Future

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Sonya A Grier, David Crockett, Guillaume D Johnson, Kevin D Thomas, Tonya Williams Bradford, Race in Consumer Research: Past, Present, and Future, Journal of Consumer Research , Volume 51, Issue 1, June 2024, Pages 56–65, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucad050

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Race has been a market force in society for centuries. Still, the question of what constitutes focused and sustainable consumer research engagement with race remains opaque. We propose a guide for scholars and scholarship that extends the current canon of race in consumer research toward understanding race, racism, and related racial dynamics as foundational to global markets and central to consumer research efforts. We discuss the nature, relevance, and meaning of race for consumer research and offer a thematic framework that critically categorizes and synthesizes extant consumer research on race along the following dimensions: (1) racial structuring of consumption and consumer markets, (2) consumer navigation of racialized markets, and (3) consumer resistance and advocacy movements. We build on our discussion to guide future research that foregrounds racial dynamics in consumer research and offers impactful theoretical and practical contributions.

The scholarship on race in the marketplace has a long history. Dating back to late 19th-century Western social science, it emerged in no small part to oppose the vulgar race science of earlier epochs. For instance, significant portions of Du Bois’ (1899) pioneering Philadelphia Negro investigate the link between market-based practices and racial segregation in the turn of the century U.S. Despite this lengthy history, many have noted that the Journal of Consumer Research ( JCR ) has published relatively few studies on the topic over its first 50 years ( Arsel, Crockett, and Scott 2022 ; Burton 2009 ; Davis 2018 ; Pittman Claytor 2019 ; Williams 1995 ). On this occasion of JCR ’s semi-centennial, we renew calls to revivify the study of race, racialization, and racism in consumer research and to situate it globally.

Race is a political, rather than zoological, categorization system that assigns physical and sociocultural traits to people and arranges them hierarchically based on those identifiers. Although racial categorization occurs around the world, it shows considerable variation across time and place. Consider that polling data from Pew Research suggest that people worldwide believe their country is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse ( Poushter, Fetterolf, and Tamir 2019 ). Yet, even as people perceive shifting demographics, their experience in national and local contexts differs fundamentally on many dimensions. Scholarship reflects how pernicious power dynamics that often take the form of anti-blackness, antisemitism, Islamophobia, anti-Asian racism, and White supremacist ideology permeate race relations. Racialization is the work of assigning ethno-racial meanings to categories and drawing boundaries around them to incorporate some and expel others ( Fanon 1961 ; Omi and Winant 2015/1986 ; Thomas, Cross, and Harrison 2018 ). Finally, racism orders and systematizes the distribution of material and symbolic resources to ethno-racial groups. It legitimizes and promotes the withholding of such resources in cultural discourse, polity, civic life, and the political economy to those positioned at or toward the bottom of the hierarchy ( Emirbayer and Desmond 2021 ). These dynamic social forces undergird and energize various social, political, and economic projects that intersect with consumer behaviors and markets ( Grier, Thomas, and Johnson 2019 ). Some of these projects foster genuinely inclusive consumer journeys. Others foster racially biased ones. And many, if not most, journeys are environmentally noxious, built on fossil fuel and exploited labor from the Global South. Thus, it behooves consumer researchers to consider race and its impact more fully on markets and in the journeys of the consumers that empower them. As an organizing feature of social life, race is central to the discipline of consumer research.

We, therefore, call for a renewed scholarly focus on the role of market institutions and consumer culture in reproducing racial group boundaries, (re-)articulating racialization logics, and challenging or exacerbating racism. This is in addition to traditional examinations of race’s influence on marketplace experiences and approaches, racialized messaging, and offerings.

We outline an inclusive vision for engaging race in consumer research by identifying important areas that dimensionalize prior and future research. However, we begin by offering some details about the authorial team that are relevant to that vision. In a spirit of reflexivity-as-praxis rather than confession, we note that each author identifies as Black, as middle-class, as North American or European, as cisgender, and as part of the Race in the Marketplace (RIM) research network, which is a multiracial and global network of scholars that examines race’s role in markets and the market’s role in race. Our purpose in this article is to introduce a broadened conceptualization of race in consumer research under the RIM moniker. To that end, we briefly discuss the nature, relevance, and meaning of race for consumer research and offer a thematic framework that critically categorizes and synthesizes prior consumer research on race along the following dimensions of meaning: (1) the racial structuring of consumption and consumer markets; (2) how consumers navigate racialized markets; and (3) the consumer resistance and advocacy movements. These dimensions are partially overlapping and variant across time and place, level of analysis (micro, meso, and macro), and defining practice. Our discussion of these dimensions generates a guide for conducting impactful consumer research that fully integrates race.

What we label “RIM scholarship” is a characterization of past and ongoing cross-disciplinary research organized around our identified themes. This labeling intends to underscore the framework’s defining dimensions of meaning. It is not our contention that all consumer research on race corresponds to RIM scholarship. Finally, although the framework is appropriate for exploring racialized phenomena outside of consumer research, that is not our present focus.

Prior to elaborating on the features of the framework, we first address a set of prevailing myths that have contributed to the historical marginalization of consumer research on race. Myths are functionally stories with morals. Myths are powerful when their morals resonate, both animating action and justifying it after the fact. Some myths perpetuate harm, especially once embedded in sociocultural systems and institutions. Once there, they can endure despite their logical flaws and factual inaccuracies. Moreover, “debunking” them, or drawing attention to those shortcomings, rarely dilutes their staying power (and ironically can facilitate resonance). Disempowering harmful myths requires direct confrontation, but for the purpose of demystifying rather than debunking them. We confront three prevalent myths about consumer research on race to first demystify them and to help advance competing myths that are more coherent, more resonant, and more perceptive.

Theoretical Insufficiency

The most enduring (and pernicious) myth about consumer research on race is that the race construct is insufficient for theory development. The argument is that race is a categorical variable, useful as a demographic or market segment identifier but not otherwise beneficial for developing theory. Theory development is hallowed ground for scholars, and obviously at JCR . But this harmful myth poisons that ground by encouraging adherents to adopt an essentialized, check-the-box notion of race that reduces it to a one-dimensional caricature rather than the unstable but legible product of various intersecting social and historical processes ( Omi and Winant 2015/1986 ). It is not surprising then that myth adherents might struggle to see the construct’s theoretical utility. Unfortunately, an impoverished understanding of race is too often misattributed to the construct itself rather than to a narrow conceptualization in the discipline, even relative to other academic disciplines. It is even more unfortunate that when this myth animates action, it poisons the ground right where theory takes root. It does so in doctoral programs, in the form of well-intentioned advice to interested students to avoid or re-frame race-related topics of inquiry. It does so when early-career scholars internalize the myth in ways that shape their scholarship. And it does so in myriad ways throughout the publication process after manuscripts are submitted. This kind of harm contributes to the marginalization of scholarship on race in consumer research, which has negative consequences for theoretical development.

Like most 20th-century social science, RIM scholarship is premised on the notion that race is socially constructed, with no immutable essence, biological or otherwise. This fundamental ontological instability is an obvious problem for static accounts of race. Yet, RIM-based inquiry treats such instability as a matter to be theorized rather than problematized. In the current era of neoliberal globalization, and in the preceding historical eras, markets and consumption have evolved in ways that situate race as a central axis of social power but with ethno-racial group boundaries and meanings that are locally contested and unstable ( Crockett 2022 ). Race is of course one of numerous axes of power that have evolved across different historical eras. We see no benefit—only loss—in pitting them against one another, as any are suitable grounds for developing theory. We posit that each warrants sustained, critical inquiry on its own terms to generate important theoretical insights independently and at their intersections.

Me-Search Is Not Research

A related harmful myth contends that marketing and consumer research on race is self-focused “me-search,” whose insights do not generalize beyond a focal racial group. This myth likewise poisons the ground for developing theory in at least two ways. First, the me-search myth presumes that race-focused inquiry constitutes politics, which moves the discipline away from an ideal of objective, dispassionate scholarship. Racially minoritized scholars who do race-focused research are effectively framed as incapable of embodying this ideal and/or find their research delegitimized when it actively attempts to unsettle this ideal. A related way it poisons the ground is by situating Western notions of middle-class whiteness as a status quo that generalizes unproblematically to other people and settings. Those others must then explain and validate their position vis a vis the status quo ( Williams 1995 ). This effectively stigmatizes research that centers the agency and experiences of people of color.

Enacting the me-search myth presupposes the wisdom of avoiding a focus on race. That renders it invisible, especially in spaces where the focal racial group is marked as White. But in the marketplace—a quintessentially social space—race is operating even if it is rarely theorized. Apart from RIM scholarship, it is uncommon for consumer researchers to report the ethno-racial composition of samples, a necessary condition for understanding even the simplest categorical effects of race. Few systematic efforts are underway to change this status quo ( Turner and Uduehi 2021 ). RIM scholars then find themselves in a catch-22—conduct research that is perceived as self-serving (and thus devalued in the academic marketplace) or limit their investigations to conceptual frameworks and methods that greatly limit the explication of meaningful insights. We posit that the more fruitful ground for theory development is the one rich with explorations of race as a global social force with local particularities rather than the one that leaves it untheorized. The RIM research network exemplifies the impressive potential of discovery-oriented scholarly exploration that centers race to operate across paradigmatic and methodological divides around the globe ( Johnson et al. 2019 ).

Race Is an “American” Problem

A third harmful myth is that RIM scholarship provides a race-only analysis that centers U.S. racial categories (especially Black and White) and politics that are not analogous to other national contexts. This criticism may reflect the U.S. origins of consumer research on race rather than its actual scope of practice. RIM scholars have written compellingly about race as a global phenomenon shaped under complex local conditions in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Europe, and the Middle East. Nevertheless, they have avoided an “exceptionalism trap” that would fix race, racialization, and racism to any specific national boundaries or deny their operation therein. They have challenged the discursive and material power of various national myths about racial “universalism” (e.g., France), “colorblindness” (e.g., U.S.), and “racial democracy” (e.g., Brazil) that would poison the ground by rendering persistent racialized inequities invisible ( Johnson et al. 2017 ; Rocha et al. 2020 ).

RIM scholarship challenges these myths where they appear in consumer research, in part, by moving away from a tidy-but-false dichotomy of “race” as phenotype and lineage and “ethnicity” as sociocultural. Although race and ethnicity are analytically distinct and draw from different intellectual traditions, in practice, they can prevail on the same social, historical, and political content. Ultimately, to avoid enacting this myth and poisoning the ground for theory development, RIM researchers must account for the relevant sociocultural, historical, and political features of a specific context that actors mobilize into a race-making project. Next, we expound on the RIM thematic framework and what it offers to a broad array of scholarly, managerial, and public policy stakeholders.

We offer a concise thematic overview that critically synthesizes prior consumer research on race along three broad dimensions: (1) the racial structuring of consumption and consumer markets, (2) consumer navigation of racialized markets, and (3) consumer resistance and advocacy movements. These three dimensions are not mutually exclusive, as scholarship can and does encompass more than one, and potentially all three dimensions.

Racial Structuring of Consumption and Consumer Markets

RIM scholarship on this dimension explains how, why, and where racialization and racial inequity take place in markets. Commonly but not exclusively operating at the macro-level of conceptualization, these studies aim to destabilize dominant conceptualizations of markets. Meaning, they reimagine markets as sites that are constituted by racism rather than sites where racialization and racial inequities merely take place sometimes. The key implication of this reimagining is that it reconceptualizes marketplace racialization and racial inequity as at least as likely to be pervasive, conspicuous, or routine as to be episodic, inconspicuous, or aberrational. The research on this dimension draws on multidisciplinary theoretics such as racial formation theory ( Omi and Winant 2015/1986 ), racial capitalism ( Robinson 2005/1983 ), intersectionality ( Crenshaw 2011/1991 ), critical race theory ( Bell 1995 ), and whiteness theory ( Roediger 1991 ) to demonstrate how racism is pervasive and routine in markets and directs their functioning. For instance, Crockett (2022) and Jamerson (2019) each draw on racial formation theory to explore the ways market systems reify racial inequities in contrast to Burton (2009) and Rosa-Salas (2019) , who incorporate whiteness theory to demonstrate the ways scholarly and practice-oriented research have historically constructed the “consumer” and the “mass (general) market” as White. Although studies on this dimension are predominantly conceptual, some utilize approaches like empirical modeling (e.g., Jaeger and Sleegers 2023 ) and mystery shopping field experiments ( Scott et al. 2023 ) to examine racial dynamics in the marketplace. Research on this dimension also explores racialization and inequity in specific market domains, including advertising ( Crockett 2008 ), alcohol and food ( Barnhill et al. 2022 ; Gaytán 2014 ), finance ( Friedline and Chen 2021 ), gentrification ( Grier and Perry 2018 ), and online markets ( Rhue 2019 ). For instance, Dhillon-Jamerson (2019) focuses on matrimonial ads in India to demonstrate how colorism intersects with social class and caste to impact the lives of women during the process of matchmaking.

Navigating Racialized Markets

RIM scholarship on this dimension assesses the effects of racialized markets on consumers and the myriad ways they attempt to construct lifestyles while living within such constraints. Researchers ask: how does the racial structuring of consumption and consumer markets impact consumer choices; how do consumers make meaning from such a structuring; and how is that meaning supported or contested by other market actors? Scholars typically broach these questions by employing micro-level methodological approaches such as one-on-one in-depth interviews ( Crockett 2017 ) and quasi-experiments ( Brumbaugh, 2002 ). It is common practice in this research to pair micro-level methodologies with macro-level conceptualizations when analyzing data. RIM scholarship that addresses navigating racialized markets represents the largest of the three dimensions discussed here and operates across a broad array of consumptive and geographic contexts. These include explorations of marketplace experiences among people in specific racialized groups, such as Black, Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous populations in the U.S., as well as racially minoritized people worldwide ( Bogatsu 2002 ; Crockett, 2017 ; Rocha et al. 2020 ; Veresiu and Giesler 2018 ). For instance, Alkayyali (2019) examines the individual coping strategies implemented by “veiled” Muslim women living in France in response to their racialized marketplace experiences. In contrast, only a few studies examine the experiences of consumers racialized as White expressly on that basis ( Johnson et al. 2017 ; Luedicke 2015 ; Peñaloza and Barnhart 2011 ). Collectively, research on navigating racialized markets explores and demonstrates the ways in which a variety of fluid coping strategies are deployed by consumers as they navigate an ever-evolving marketplace.

Consumer Resistance and Advocacy

RIM scholarship on this dimension centers on consumers’ collective actions to advance their race-related political agenda. Often using meso-level conceptual frameworks and/or historical approaches, this research considers consumer collectives and markets as sites of political expression and resistance. The core question driving this scholarship is about how consumers engage in cooperation and conflict to challenge or support the racialization of markets. Studies examine diverse consumer movements involving protests, boycotts, buycotts, and/or the establishment of self-organization. For instance, research on boycotts investigates consumer movements that oppose products and services connected to slavery ( Page 2017 ), segregation ( Brown 2017 ), and (neo)colonialism ( Parnell-Berry and Michel 2020 ). It also examines racist collective projects like consumer boycotts against Jewish populations in pre-Nazi Germany ( Stolle and Huissoud 2019 ) and far-right extremist organizations mobilizing White consumer movements ( Miller-Idriss 2018 ). Researchers also explore “buycotts” and self-organized consumer groups and segments ( Branchik and Davis 2009 ). Drawing on notions such as sovereignity, solidarity, and agency, these studies investigate self-organizing in domains as diverse as recreation ( Harrison 2013 ), access to food ( Reese 2018 ), and personal finance ( Krige 2014 ). Exploring “financialization from below” in an all-male savings club in Soweto (South Africa), Krige (2014) shows how participants viewed self-organizing as a means to move away from apartheid’s racial capitalism and embrace the political and economic promises of the “New” South Africa. Overall, research on consumer resistance and advocacy demonstrates how consumer collectives emerge, develop, and collapse as they challenge or sustain the marketplace’s racialized allocation of resources.

Table 1 summarizes each RIM consumer research dimension, its distinguishing characteristics, and opportunities for research.

RIM Consumer Research Dimensions.

Leveraging the thematic organization of prior research, we now provide broad guidance on how consumer researchers could engage race and racial dynamics in a manner that yields important theoretical and practical contributions.

Crafting a Solid Foundation

Whether a new investigator or a seasoned researcher, the basic aspects of research merit self (and research team) reflexivity. Across a multitude of design choices throughout the research process (e.g., questions, methods, sample), each warrants consideration of race. Researchers can reflect on how their backgrounds, beliefs, and motivations challenge efforts at neutrality and filter approaches to conducting research. Additionally, taking an intersectional approach to contemplate the interconnected nature of different forms of oppression in the research endeavor will better capture institutionalized modes of gendered, racialized, and economic oppression at the core of any consumer research project ( Poole et al. 2021 ). Deliberate and systematic attention to race and intersecting power dynamics in the conceptualization, design, and implementation of research studies is more likely to generate theoretical knowledge with real practical impact.

Adopting Theories, Frameworks, and Constructs

Consumer researchers adopt theories that influence how they conceive of race and related constructs, as well as shape study design and ascertained knowledge. Seemingly “universal” theories, frameworks, and constructs carry ontological assumptions that structure or constrain ideas and understanding. Many are empirically calibrated on homogeneous, primarily White, middle-class samples and have not been tested with other populations. The late Williams (1995 , 240) lamented the discipline’s reliance on theories and approaches developed with populations that are “vastly different from today.” The use of race-focused theoretical approaches that incorporate history and sociopolitical concerns can help broaden rather than limit disciplinary knowledge.

The dynamic nature of racialization reinforces the need for attention to how category boundaries are defined. Scholars should define what “race” means in their study—identify how it is embedded in the consumer ideologies and/or practices under study, and where relevant, influenced by sociopolitical forces. This involves reflecting on constructs explicitly about race (e.g., racial identity and racial socialization). But it may also involve reconceptualizing presumably race-neutral constructs (e.g., self-efficacy and deservingness) to include racially influenced perspectives that may be unaccounted for yet still operating. Intentional use of both types of constructs can enhance research protocols.

Echoing recent calls in management studies ( Phillips et al. 2022 ), RIM researchers should explore constructs that mark advantage (e.g., privilege, trust) as well as disadvantage (e.g., prejudice, stigma, stereotyping). Indeed, framing inequity solely as disadvantage shapes beliefs about inequity and its causes and impacts ( Phillips et al. 2022 ; Thomas 2017 ). For example, a focus on disadvantaging constructs (e.g., reducing prejudice) in retail discrimination may diminish racial inequity without eradicating it in part because advantaging mechanisms (e.g., helping) that fuel discrimination have not been addressed. Scholars can strategically and creatively use common constructs (e.g., trust and satisfaction) to support theoretical understandings of race-related phenomena. We suggest that consumer researchers shift their orientation from stigma-centric to one focused on privilege and related power dynamics to fully grasp the persistence of racial inequality in markets and envision possible alternatives.

Innovative Methods

An enhanced engagement with race in consumer research could benefit from developing and using multiple, innovative methods. Research methods utilizing artistic processes such as photography, video, poetry, drawings, or a creative combination of thereof ( Harrison 2019 ; Sobande et al. , 2021 ; Wilson 2020 ) can creatively reflect the theoretical articulation of sociopolitical forces that influence consumer markets. While a full accounting of these approaches is beyond the scope of this commentary, a key point is that innovative methods that identify specific ways to connect the individual to systems of power and the environment will best support future research efforts in this area.

Global pandemics, economic turmoil, military conflict, and climate crisis, each of which intersects with consumption, imperil human survival on this planet. These ongoing threats simultaneously shape contemporary consumer markets and disproportionately impact those at the bottom of the global racial hierarchy who do not have equal access to harm-mitigating resources. Consumption of mass-produced products, especially those reliant on fossil fuels, encompasses issues of environmental justice and social sustainability, and all consumer research, including RIM research, must be situated in this macro-social context.

The thematic framework presented above provides a springboard to examine a vast array of groups, dynamics, and innovative consumer research topics around the world, anchored in various ways to race. Scholars may center directly on race as a topic, examine race-related domains, or infuse their current investigations with a better and deeper understanding of the role race may be playing. For those with an interest but less certainty about where to focus, we add to recent scholarship on race and racism that highlights future consumer research paths ( Grier, Johnson, and Scott 2022 ; Thomas, Johnson, and Grier 2023 ; Wooten and Rank-Christman 2022 ).

Category Construction and Racialization