- Business & Enterprise

- Education, Learning & Skills

- Energy & Environment

- Financial Services

- Health & Wellbeing

- Higher Education

- Work & Welfare

- Behavioural insights

- Business Spotlight – IFF’s business omnibus

- Customer experience research

- Customer satisfaction measurement

- National statistics and complex surveys

- Stakeholder research

- Tenant satisfaction measures

- Our approach

- Trusted partner

- Equality, diversity & inclusion at IFF

- Sustainability at IFF

- Charity giving

- Meet the team

- News & resources

- Case studies

How to write an effective research brief

Whether you’re launching a simple survey or planning a large-scale project the quality of your brief will hugely impact on the value you get from the research. While it can take a little time and effort creating a research brief, it will undoubtedly be time well spent – getting you better results and return on your investment and saving you valuable resources on further clarification. At best, a poor brief will be a time drain on you and your team. At worst, the findings will fail to meet your objectives, costing you time and money.

We’ve seen a lot of research briefs over the years. Some of which have been well thought through and clear, helping us prepare a detailed proposal and deliver an effective project and subsequent results. And others which have been not so good, lacking clarity or detail.

Using this experience, we’ve put together a ‘how to’ guide on writing an effective research brief, to help you ensure success on your next project.

1. Preparation is key

As with any project, before you start it’s crucial you think through what you want and need to deliver. Here are some things you should consider:

- Why are you conducting the research? What exactly are you looking to understand?

- Who are you looking to understand better? Who do you need to speak to answer your research questions?

- Who are your internal stakeholders? Have you discussed the project needs with the people in your organisation who will use the findings or who are invested in the research?

- How will the findings be used?

- When do you need the findings?

- Have you agreed a budget with either your procurement team, or the relevant person in your organisation?

2. Be clear on your objectives

This is one of the most important parts of your brief to convey to the reader what you want out of the project and ensure you get results which deliver.

Projects should have around three or four overarching aims which set out what the project ultimately wants to achieve.

These might be things like:

- Assess the impact of……

- Examine views of…..

- Evaluate the effectiveness of….

In addition to project objectives, you should also include the key questions you want the research to answer. These should support you in meeting the aims of the research.

For example, if the project aim is to assess the impact of an intervention, your research questions might include:

- Who did the intervention target?

- What did the project deliver?

- What elements were successful, and why?

- What were the main enablers and barriers?

3. Remember your audience

Research agencies or organisations who will be responding to your brief might not know anything about your business. So, make sure you include enough background information in your brief to enable them to understand your needs and deliver effectively. And avoid use of jargon or acronyms which could lead to errors or confusion.

4. Structure your research brief

Before you start to populate your brief it’s worth considering all the information and sections you need to include, to structure your thinking and ensure you don’t miss anything important.

This might include some, or all, of the following:

- Background info

- Introduction

- Aims and objectives

- Research Question(s)

- Issues / Risks

- Methodology

- Timing and Outputs

- Project Management

5. Make it thorough, yet succinct

While it’s crucial to include all the relevant information to enable bidders to respond effectively, no one wants to read reams and reams of information. To avoid the key information getting lost in the details use annexes to add supplementary information which could be useful.

6. Consider how prescriptive you want to be on the methodology

The extent to which you want to specify the methodology will depend on the project you aim to deliver. There are benefits and risks to being overly prescriptive or offering free reign. If you outline in precise detail how you want the research to be conducted, you will hamper any original ideas from those invited to tender and might limit the impact on the research. Whereas, if you’re less prescriptive, allowing room for creativity, you risk not getting the project or results you want, or receiving proposals on a scale which you can’t resource.

Generally, it is useful to allow those invited to tender some scope to develop the methodology they propose to use. Exceptions might be where previous work has to be very precisely replicated or some other very precise commitment about the nature of findings has been given to stakeholders.

7. Define your timelines

As a minimum, you need to include when you want the project to start and end. But you should also include the timetable for procurement. When planning this, don’t underestimate the time and resource needed to run a procurement exercise. Make sure your evaluators are available when you need them and have enough time blocked out in their diary.

You’ll likely also want to include milestones for when you expect outputs to be delivered, such as deadlines for a draft report (providing opportunity for review and feedback) and the final report; allowing sufficient time between the two to enable your stakeholders to consult, for you to feedback and for the contractor to revise the report.

8. Set expectations on cost

You will most likely have budgetary constraints, with a figure for what you are prepared to spend. To save you and your bidders time, and to set realistic expectations, you should include an indication within your brief. This will prevent you receiving proposals which are way out of the ballpark; enable bidders to plan a project which delivers on (or at least close to) budget; and will prevent any nasty surprises, further down the line.

By following these tips you’ll be well on your way to creating an effective research brief which delivers on time and on budget.

If you’d like more guidance download our “step-by-step” guide, which includes a template and information for what to include in each section to ensure success.

Download the guide now.

- Scroll to top

- Light Dark Light Dark

Cart review

No products in the cart.

Research Brief Format: Essential Guide for Clear & Concise Reports

- Author Survey Point Team

- Published February 28, 2024

Research brief format are invaluable tools for distilling complex research findings into an easily digestible format for busy stakeholders. A well-structured research brief gets the most important information in front of decision-makers, policymakers, and other non-technical audiences. This guide breaks down the essential elements that make a research brief impactful and easy to understand.

Delving into the world of research briefs requires finesse and a deep understanding of the essentials. In this guide, we unravel the intricacies of the [Research Brief Format: Essential Guide for Clear & Concise Reports]. From the foundation to advanced strategies, we’ve got you covered. Let’s embark on this journey to elevate your reporting skills.

Table of Contents

Research Brief Basics

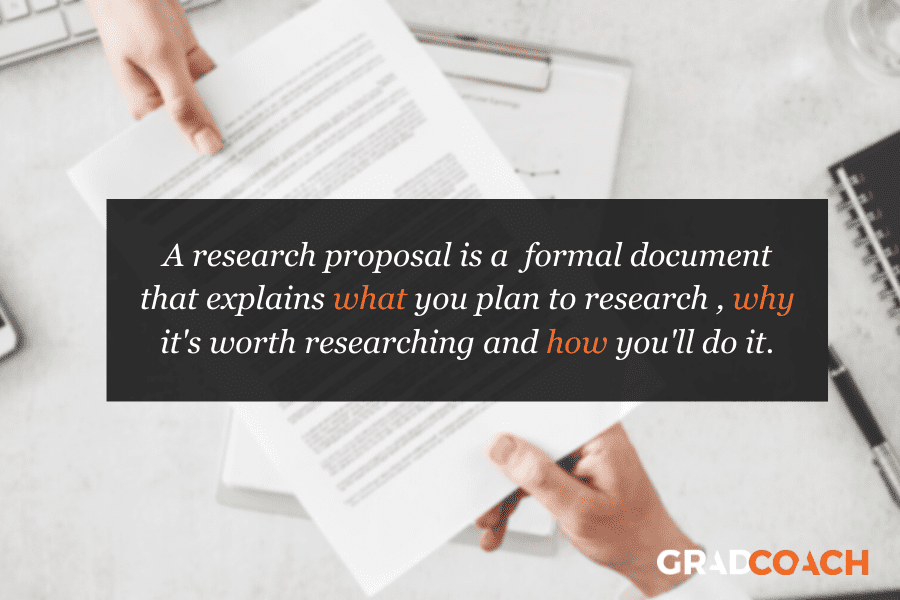

Definition and Purpose: A research brief is a short, targeted summary of a research study or project. Its primary purposes are to:

- Inform decision-makers who might not have time for in-depth reports.

- Influence policy by highlighting key research outcomes.

- Shape public opinion or action regarding a specific issue.

Target Audience: Research briefs are written for a non-specialist audience. This generally includes policymakers, stakeholders, or the general public without the technical background to decipher full research reports.

Key Differences from a Research Report:

Length: Research briefs are concise (often 2-4 pages), while reports are much longer.

Focus: Briefs highlight key conclusions and recommendations, while reports present detailed methodology, data, and in-depth analysis

Essential Elements of a Research Brief Format

Title: Concisely and accurately reflects the research focus.

Executive Summary: A few sentences or a short paragraph outlining the absolute essentials: problem, key findings, and main recommendations.

Background/Problem Statement: Briefly explain the issue the research addressed and why it matters.

Research Questions: State the specific questions your research sought to answer.

Methodology: A high-level summary of your research methods (e.g., surveys, experiments, etc.). Avoid excessive technical detail.

Key Findings: Present main findings as clear bullet points or short statements.

Recommendations: Offer actionable recommendations based directly on your findings.

Limitations: Briefly acknowledge factors that might limit the generalizability of your findings.

Visual Aids (Optional): A simple graph or chart can powerfully illustrate the most important finding.

Tips for Writing Clear & Concise Research Brief Format

Plain Language: Ditch the jargon and complex terminology!

Focused: Include only the most essential information for your target audience.

Action-oriented: Clearly emphasize the implications of your findings and provide practical recommendations. What is the ideal length for a research brief? A research brief’s length depends on the complexity of the topic. However, aiming for a concise document of 2-3 pages is often effective.

Frequently Asked Questions

How crucial are LSI keywords in a research brief? LSI keywords enhance the visibility and relevance of your research brief, making it a vital element for a successful report.

Can visual aids replace detailed explanations? While visual aids are impactful, they should complement, not replace, detailed explanations. Balance is key for an effective research brief.

Is there a specific structure to follow in a research brief? Yes, a well-structured research brief typically includes an introduction, methodology, findings, and conclusion. Adhering to this format ensures clarity.

How can I scope my research effectively? Define the scope by clearly stating the objectives, limitations, and expected outcomes of your research. This provides a clear roadmap for your study.

Should I include recommendations in my research brief? Yes, offering actionable recommendations adds value to your research brief, demonstrating its practical implications.

A well-formatted research brief is a powerful communication tool . It can shape how your research is understood and applied by those in positions to make a difference. Use this guide to create briefs that are both informative and persuasive.

Survey Point Team

Marketing91

Research brief: Meaning, Components, Importance & Ways to Prepare

June 12, 2023 | By Hitesh Bhasin | Filed Under: Marketing

Have you ever faced a situation where a researcher has not exactly given the results that you require? Have you ever discussed research as what you want precisely and been disappointed to find that there is a disparity in your expectation and the outcomes? This is because of a failure in communication , that is particular an insufficient brief.

This is where we exactly wish to discuss research brief.

A research brief is a statement that comes from the sponsor, who sets the objectives and background. This is to enable the researcher to plan the research and conduct an appropriate study on it. Research Brief can be as good as a market research study and is very important to a researcher.

It provides good insight and influences on the choice of methodology to be adopted in the research. It also provides an objective to which the project links itself.

It is a short and non-technical summary of a discussion paper that is purely intended for decision-makers with a concentration on the paper’s policy-relevant findings.

Table of Contents

Components of a Research Brief

Some sponsors deliver the brief orally by developing many detail points at the time of initial discussion with the researcher. On the other hand, the brief can also be completely thought through and committed to a paper.

This is very important when many research agencies need to submit proposals. Whether the research brief is oral or written, it should pay attention to the following points:

- Problem Background – This is a short record of the events which has actually led to the study. This provides an insight into the researcher a better viewpoint and understanding of the objective of the project.

- Problem Description – The researcher requires details in depth to perform the research. When the scope of the research is described properly, the research process gets easier. It becomes helpful for the sponsor to monitor the progress of the research.

- Market Analysis – The researcher needs to know the geographical areas of the research. Hence this should be part of the research brief.

- Objective Statement – The object of the researcher should be put statement. The researcher should gather the details from the sponsor and then provide a view of what has to be achieved.

- Time and Budget – The research brief should mention the time and budget constraints of the research.

Importance of Research Brief

Now, why is research brief important? It is like the way you set a foundation for a building; research brief provides a strong foundation for the research process.

Writing a research brief is important to the success of any market research project. However, it can be difficult to craft the perfect brief that meets the necessity of both the client and the researcher but eventually leads to the desired outcomes.

It helps a researcher to identify a problem to be researched, the exact background of the problem, the required details to address the problem, time and budget constraints within which the research is supposed to be designed.

Example of Research Brief

Keeping the above points in mind, let us take a small example of the way to write a market research brief.

To write a market research brief, it clarifies the research requirement and also makes sure that the ideas are well articulated. It helps to write a better research proposal , conduct user research, and achieve the desired outcome.

Background:

Describe the problem that is required to solve. Include applicable background and the challenge during the research.

Business and Project Objectives:

Explain the business objectives. For example: to increase sales /profit. Try to be specific as you can.

Also, describe the purpose of research and the expected outcomes. What is the decision that you require to make?

Market Objectives:

Market research objective typically follows from the above two objectives. Hence you will need to summarise the aim and information of the research. This will help to mention the questions required for answering.

Stakeholders:

Here, you will need to consider the participant who will sign-off and act on the research outcomes listed.

Research Methods, scope, sample, and guidelines:

Here, you will explain what is required. This will help you to focus on what is important and also have a piece of knowledge of the research investment. Here, more focus is given on the scope of the work and type of research . The inputs and the sample are also analyzed.

Research outcomes:

Here, you will require to define the delivery part of the research.

Ways to prepare Research Brief

Having discussed the basic of research brief, the following points will give you a brief idea of the ways to prepare yourself to write an effective research brief.

- Start with a summary of the current situation. Also, define in clear words as what you are already aware of. It would be more useful if you could include more details on your thought about the responsibility for the project on you and the research agency.

- After a summary, set up the business and research objectives . For business objectives, you need to mention the overall strategy and what is the importance of the current research. For research objectives, list the issues and topics that are likely to discover. List the problems to solve. Based on the research agency design, define clearly the business and research objectives. Having a clear objective will help you to assess the quality and also focus on the research agency’s report.

- Next, you may suggest about the ways about data collection . You can decide on a suitable research methodology that you think will be best fit the project.

- List what the outcomes of the project and the deliverables are. Like for example, you might just want to advise on survey design . For this, statistically robust data would be ideal. Or sometimes, you might write a full report with data, interpretation, recommendations, etc. Whatever it is, be clear as what is required. Suggest a timetable and mention the deadline to receive proposals and other deliverables.

Research Brief Template

Given below the template for research brief:

Research Brief: Project Name

#1 background.

In this area, give the background of the research brief.

#2 Business objectives

In this area, define the business objectives. Ideally, for a better understanding and readability, it would be good if the points are bulleted.

#3 Marketing objectives

In this area, type your marketing objectives. In case you have any other kind of objectives apart from marketing, you could change the section title.

In this area, define the research target here. Here, name all the target groups that will be a part of the research and the reason for it. Capture any other applicable details of the target group .

In this area, mention the Budget information. Mentioning a range of budget is fine. Also, indicate an upper limit in case you have any.

In this area, mention the timeline of the research. The approximate time as when this work would be over. Also, when can you provide the final analysis?

#6 Deliverables

In this area, mention the report requirements. For example, whether a detail report is required or just a presentation.

#7 Contact information

In this area, mention the contact information for questions or clarification. It could be Client company name or Individual name, title, e-mail id, phone number, and mailing address.

Liked this post? Check out the complete series on Market research

Related posts:

- What is Brand Brief? Components of Brand Brief and Examples

- Causal Research – Meaning, Explanation, Examples, Components

- What is a Design Brief and How to Write it in 9 Easy Steps?

- Qualitative Research: Meaning, and Features of Qualitative Research

- Advertising Message – Definition, Meaning, Importance and Components

- Research Ethics – Importance and Principles of Ethics in Research

- Market Space – Definition, Meaning, Characteristics, Components

- Sales Agreement – Meaning, Components and Samples

- How to Write Research Proposal? Research Proposal Format

- 7 Key Differences between Research Method and Research Methodology

About Hitesh Bhasin

Hitesh Bhasin is the CEO of Marketing91 and has over a decade of experience in the marketing field. He is an accomplished author of thousands of insightful articles, including in-depth analyses of brands and companies. Holding an MBA in Marketing, Hitesh manages several offline ventures, where he applies all the concepts of Marketing that he writes about.

All Knowledge Banks (Hub Pages)

- Marketing Hub

- Management Hub

- Marketing Strategy

- Advertising Hub

- Branding Hub

- Market Research

- Small Business Marketing

- Sales and Selling

- Marketing Careers

- Internet Marketing

- Business Model of Brands

- Marketing Mix of Brands

- Brand Competitors

- Strategy of Brands

- SWOT of Brands

- Customer Management

- Top 10 Lists

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- About Marketing91

- Marketing91 Team

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Editorial Policy

WE WRITE ON

- Digital Marketing

- Human Resources

- Operations Management

- Marketing News

- Marketing mix's

- Competitors

AdGrade Digital

Other Research Solutions

- AI Qualitative Research

Consumer Platform

- Oil & Energy

Personal Care & Cosmetics

Media & Entertainment

Apparel & Fashion

- Health Care & Pharmaceuticals

Telecommunication

How It Works

Multi-dimensional Data

Digital Targeting

Geo-triggering

Customer Dashboard

Media & Press

Blockchain: The Revolutionary Technology of the Digital World

Iblockchain technology, although initially introduced in satoshi nakamoto's 2008 bitcoin paper, now spans a wide range of applications from the financial sector to healthcare services, supply chains, and voting systems. this technology enables transactions to be recorded and verified on a distributed network without the need for a third-party intermediary, thus minimizing issues like data manipulation and fraud while enhancing transparency and trust., how to write a good and effective research brief, as twentify, we believe a well-written research brief sets the foundation for a successful research study. in this blog post, we will discuss how to write a good and effective research brief that will help companies run a successful study and reach their goals., understanding the purpose of the research.

The first step in writing a research brief is to understand the purpose of the research. This means identifying the problem or opportunity that the research will address. Therefore, it is essential to be clear about the research objectives and clearly communicate them in brief. This will ensure that everyone involved in the research project is on the same page and working towards the same goals.

Defining the Target Audience

Once the purpose of the research has been established, it is essential to define the target audience. For example, who are the people that the research is intended to reach? Understanding the target audience is crucial as it will help to determine the research method, sample size, and the questions that will be asked.

Determining the Research Methods

The next step is to determine the research methods that will be used. Many methods can be used, including surveys, focus groups, and interviews. Choosing the most appropriate method for the research objectives and target audience is essential.

Developing a Detailed Research Plan

Once the research methods have been determined, developing a detailed research plan is essential. This plan should include the specific questions that will be asked, the sample size, and the timeline. It is also necessary to consider the research budget and allocate resources accordingly.

Reviewing and Refining the Research Brief

Finally, it is essential to review and refine the research brief. This means checking the research objectives, target audience, methods, and plan to ensure they are clear, accurate, and achievable. This review process is crucial to ensure that the research project is set up for success.

In conclusion, writing a good and effective research brief is crucial for running a successful study. By understanding the research purpose, defining the target audience, determining the research methods, developing a detailed research plan, and reviewing and refining the research brief, companies can ensure that their research project is set up for success.

As an innovative consumer and market research company, we are committed to helping companies reach their goals by running successful research studies.

Contact us today to learn more about how we can help you with your research needs.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR | Ogün Tübek

Topics: RESEARCH

Popular searches

- How to Get Participants For Your Study

- How to Do Segmentation?

- Conjoint Preference Share Simulator

- MaxDiff Analysis

- Likert Scales

- Reliability & Validity

Request consultation

Do you need support in running a pricing or product study? We can help you with agile consumer research and conjoint analysis.

Looking for an online survey platform?

Conjointly offers a great survey tool with multiple question types, randomisation blocks, and multilingual support. The Basic tier is always free.

Catherine Chipeta

Monthly newsletter.

Get the latest updates about market research, automated tools, product testing and pricing techniques.

A good market research brief helps agencies lead successful projects. Learn what to include and how to write a detailed brief with our template guide.

A market research brief is a client document outlining all the relevant information that a research agency needs to understand the client’s specific research needs to propose the most suitable course of action.

A clear, informed brief will ensure the market researcher can deliver the most effective research possible. It also streamlines the project by reducing the need for back and forth between your company and the researcher. A good brief will leave no confusion and provide a meaningful framework for you and the researcher, maximising the accuracy and reliability of insights collected.

Start your project faster with our market research brief template!

In this article, we’ve broken down the key components of a well-written brief, with examples. Using this template guide, you can confidently equip the researcher with the right information to deliver exemplary research for your next project.

Business Background/ Project Background

This section of the brief introduces your company to the market researcher, giving them a more informed overview of your brand, product/service, and target market. You should provide all available context to ensure you and the researcher are on the same page with the project.

Relevant information to add in this section includes: company details, company mission/vision, industry status and trends, market performance history, competitive context, any existing research.

Business Objectives/ Marketing Objectives

Your business objectives/marketing objectives should answer why you are being asked to conduct the research. The researcher should be able to grasp the existing problems/issues your company is looking to address in the research.

For example, this could involve sales, competition, customer satisfaction, or product innovation, to name a few.

Research Objectives

Research objectives address the specific questions you would like the research to cover, including what insights you wish to gain. This is where you should detail what actions your company is planning to take based on the research you are commissioning.

Your research objective is one of the most important elements of your brief, as it dictates how your study will be conducted and the quality of results.

Target Market

Who will this research focus on? This is where you should state respondents’ demographic and profiling information, along with any pre-existing segments you want to target. Be specific, but also be aware that the more restrictive the criteria are, the higher the sample cost will be. Extensive limitations are also realistically harder to meet.

For example:

- Market: Canada

- Sample size: 200 – 1000

- Demographics: Household income of $150k and above a year

- Markets: Malaysia (priority), Thailand, Singapore

- Sample size: N=200 (Product Variant Selector) + N=500 (Conjoint)

- Demographics: 16 – 50 years old

- National representation: Age, gender and location

- Target definition: Bought electronics online in the past 12 months

- Reads on: 16 – 30-year olds vs. 31 – 50-year olds

- Market: South America

- Sample size: 1800

- Target definition: Main and joint grocery buyers

- 5 target groups: Income, urban/rural, age, family status, shopping frequency (divide each into 3 subgroups, e.g. low, medium, high).

Action Standards/ Decision Rules

Action standards outline which criteria will determine the decisions you make following research. These should detail specific numerical scores and any company benchmarks which need to be met in your research results for decision-making to go ahead. Clear and detailed action standards will allow you to make decisions faster and more confidently following research.

Nestlé’s 60/40 action standard which prioritises preference and nutrition, by aiming “to make products that achieve at least 60% consumer taste preference with the added ‘plus’ of nutritional advantage”.

Pricing is seen as credible by at least 40% of the target market.

Product has at least 50% acceptance from the target market.

Methodology

You should only include methodology if you are certain of the approach you want to take. If you do not know which methodology you should use, leave this section blank for agency recommendations.

Monadic test : Monadic testing introduces survey respondents to individual concepts, products in isolation. It is usually used in studies where independent findings for each stimulus are required, unlike in comparison testing, where several stimuli are tested side-by-side. Each product/concept is displayed and evaluated separately, providing more accurate and meaningful results for specific items.

Discrete choice modelling : Sometimes referred to as choice-based conjoint, discrete choice is a more robust technique consistent with random utility theory and has been proven to simulate customers’ actual behaviour in the marketplace. The output on relative importance of attributes and value by level is aligned to the output from conjoint analysis (partworth analysis).

Qualitative research : Qualitative forms of research focus on non-numerical and unstructured data, such as participant observation, direct observation, unstructured interviews, and case studies.

Quantitative research : Numbers and measurable forms of data make up quantitative research, focusing on ‘how many’, ‘how often’, and ‘how much’, e.g. conjoint analysis , MaxDiff , Gabor-Granger , Van Westendorp .

Deliverables

Deliverables should clearly outline project expectations – both from your company and the agency. This should cover who is responsible for everything required to undertake research, including survey inputs and outputs, materials, reporting, reviewing, and any additional requirements.

- PowerPoint presentation

- Crosstabs of data

- Raw datasets

- Excel simulator

- Online dashboard

- “Typing tool” for future research

Timing and Cost

Timing covers the due dates for key milestones of your research project, most importantly, for your preliminary and final reports. Cost should include your project budget, along with any potential additional costs/constraints.

Contacts and Responsibilities

This section states all stakeholders involved in the project, their role and responsibilities, and their contact details. You should ensure that these are easy to locate on your brief, for quick reference by the agency and easier communication.

Ready-to-use market research brief template with examples

Start your research project faster and get better results. Using this template, you can confidently equip the researcher with the right information to deliver exemplary research for your next project.

Read these articles next:

Reddit rebrand — new vs. old.

To evaluate the effectiveness of Reddit's recent logo update, this Logo Test compares the new 2023 logo with the 2017 Reddit logo.

Kano Model or MaxDiff Analysis?

Should you use Kano or MaxDiff for feature selection? We compare the two and draw practical recommendations.

How to get the most out of open-ended questions

Open-ended questions should be part of any research project as they can gather in-depth and rich insights from your target audience. Learn more about open-ended questions and getting the most out of them for your projects.

Which one are you?

I am new to conjointly, i am already using conjointly, cookie consent.

Conjointly uses essential cookies to make our site work. We also use additional cookies in order to understand the usage of the site, gather audience analytics, and for remarketing purposes.

For more information on Conjointly's use of cookies, please read our Cookie Policy .

Do you want to be updated on new features from Conjointly?

We send occasional emails to keep our users informed about new developments on Conjointly , such as new types of analysis and features.

Subscribe to updates from Conjointly

You can always unsubscribe later. Your email will not be shared with other companies.

Ready to level up your insights?

Get ready to streamline, scale and supercharge your research. Fill out this form to request a demo of the InsightHub platform and discover the difference insights empowerment can make. A member of our team will reach out within two working days.

Cost effective insights that scale

Quality insight doesn't need to cost the earth. Our flexible approach helps you make the most of research budgets and build an agile solution that works for you. Fill out this form to request a call back from our team to explore our pricing options.

- What is InsightHub?

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

- Data Activation

- Research Templates

- Information Security

- Our Expert Services

- Support & Education

- Consultative Services

- Insight Delivery

- Research Methods

- Sectors We Work With

- Meet the team

- Advisory Board

- Press & Media

- Book a Demo

- Request Pricing

Embark on a new adventure. Join Camp InsightHub, our free demo platform, to discover the future of research.

Read a brief overview of the agile research platform enabling brands to inform decisions at speed in this PDF.

InsightHub on the Blog

- Surveys, Video and the Changing Face of Agile Research

- Building a Research Technology Stack for Better Insights

- The Importance of Delegation in Managing Insight Activities

- Common Insight Platform Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

- Support and Education

- Insight Delivery Services

Our services drive operational and strategic success in challenging environments. Find out how.

Close Connections bring stakeholders and customers together for candid, human conversations.

Services on the Blog

- Closing the Client-Agency Divide in Market Research

- How to Speed Up Fieldwork Without Compromising Quality

- Practical Ways to Support Real-Time Decision Making

- Developing a Question Oriented, Not Answer Oriented Culture

- Meet the Team

The FlexMR credentials deck provides a brief introduction to the team, our approach to research and previous work.

We are the insights empowerment company. Our framework addresses the major pressures insight teams face.

Latest News

- Insight as Art Shortlisted for AURA Innovation Award

- FlexMR Launch Video Close Connection Programme

- VideoMR Analysis Tool Added to InsightHub

- FlexMR Makes Shortlist for Quirks Research Supplier Award

- Latest Posts

- Strategic Thinking

- Technology & Trends

- Practical Application

- Insights Empowerment

- View Full Blog Archives

Discover how to build close customer connections to better support real-time decision making.

What is a market research and insights playbook, plus discover why should your team consider building one.

Featured Posts

- Five Strategies for Turning Insight into Action

- How to Design Surveys that Ask the Right Questions

- Scaling Creative Qual for Rich Customer Insight

- How to Measure Brand Awareness: The Complete Guide

- All Resources

- Client Stories

- Whitepapers

- Events & Webinars

- The Open Ideas Panel

- InsightHub Help Centre

- FlexMR Client Network

The insights empowerment readiness calculator measures your progress in building an insight-led culture.

The MRX Lab podcast explores new and novel ideas from the insights industry in 10 minutes or less.

Featured Stories

- Specsavers Informs Key Marketing Decisions with InsightHub

- The Coventry Panel Helps Maintain Award Winning CX

- Isagenix Customer Community Steers New Product Launch

- Curo Engage Residents with InsightHub Community

- Tech & Trends /

- Research Methods /

- Strategic Thinking /

How to Write a Market Research Brief (+ Free Template)

Emily james, pitch it: the business case for customer salience.

As insight experts, we understand the power of insights, their inherent value in key decision-making...

- Insights Empowerment (29)

- Practical Application (170)

- Research Methods (283)

- Strategic Thinking (192)

- Survey Templates (7)

- Tech & Trends (387)

A market research brief is a document a client produces detailing important information about their unique situation and research requirements. This information should include (but is not limited to) the context of the situation in which the decision to conduct research was made, the initial objectives, and the resulting actions that hope to be taken after the research has concluded.

This brief would come before the typical market research plan (see our example here ), and so any information that is contained within the brief will be subject to modification once in-depth chats between the client and the research agency have been conducted.

This is one of the most important initiating steps for market research as it provides the necessary information that researchers need to understand your needs as much as you do yourself. There is a lot to be said for being on the same page at this early stage of the research experience. While different agencies will prioritise different aspects of the research project, 90% of the brief will follow the same lines, so a draft should always be made and then it can be easily edited to the agency’s requirements.

Why Create a Market Research Brief?

Writing up a brief is essential for the clear communication of your research requirements. Clear communication from the very start is essential if a positive working relationship is going to bloom between the parties involved. This brief outline of a business’ unique scenario communicates information that researchers need in order to achieve a high level of understanding which they can use to create and further refine a detailed plan the research experience.

Key Components

Just looking at the many template designs out there, we can see that a research brief has a few key aspects that everyone agrees are important:

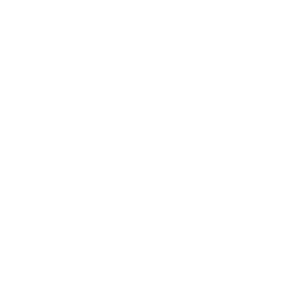

1. Contextual Information

Now this can be interpreted in two ways, both of which should be included within the market research brief. The first interpretation is contextual information relating to the business hiring the research agency. What does the business do? What are it’s values? How is it run? And then the second interpretation is contextual information relating to how the need for research arose. What are the steps that took place towards the realisation that research was needed? This timeline could span months or just days, but even so, the detail must be included for the researcher to get a full understanding of the situation at hand.

2. Description of Research Purpose

At this point, a description of the product (or service) which is to be researched is needed; whoever is carrying out the research will need to know as much detail as possible about the subject of the study as this will have a big influence on the research method used (more information on that to come).

A description of the target markets will also be needed at this point: covering the geographical territories, the target audience (consumers vs. potential consumers) and any specific demographics that should be included or excluded. If this information is known, an approximate sample size can also be noted down.

If a business is wanting to test adverts, product examples, etc. then example designs or prototypes are going to be needed for both the researcher and the participants to use in the formation of the research tasks and the generation of data.

3. Objectives

Again, this aspect of the brief can be split up into two equally important interpretations. The objectives of the business are incredibly important as they provide another level of contextual understanding for the researcher. The other set of objectives that are needed within the brief, are the research objectives. Now, these are usually formed as questions that the business would like answered, but are subject to modification with the input of the researcher as they will know what is achievable, and what the business needs instead of what they want. Research objectives also cover what the business want to do with the insights generated as that gives an indication of what sort of research needs to be conducted. For the best research experience that ends in fully applicable insights, aligning business and research objectives is imperative.

4. Research Methods

While this will also be subject to modification, an idea of what types of research methods the business might want to employ for this research experience will provide insights on a couple of things to a well-trained researcher. Firstly, it will indicate the business’ level of knowledge on market research, which will allow the researcher to adjust their tone, etc. to accommodate for any knowledge gaps that might be present.

Secondly, it will indicate what type of research that the business is looking to conduct (i.e. qualitative or quantitative, etc.), even if they don’t know it themselves. This section also serves the purpose of sparking a bit of research on the business’ end to see for themselves what options are available to them.

5. Business constraints

This is a relatively simple one. Constraints such as time and budget are imperative to communicate to the researcher, as this will be the main factor in the shaping of your research experience. Depending on whether a business is very constrained or loosely constrained will determine what types of research tasks should be employed, and how extravagant and dedicated a researcher can be in their pursuit of insights for the business.

a. Research Deliverables

Finally, this is an optional category of information that will help shape the research experience in both the formation of the research tasks and the research reports. One important question is, what actions would you want to take after receiving the insights from the research?

If the answer to this question depends on the tone of the insights, then what options do you see for how the results will be used within the business? Different agencies will offer different reporting options and it helps to know which you would like. So, what type of report would you like to receive? The answers to these questions help how the report and project are framed.

Free Template Example

Use this link to download our free market research brief template. This template contains editable sections that complies with the advice above, with brief guidance and tips on how to make the most out of your brief. This template is currently available in .docx format only, and will require a copy of Microsoft Word or an alternative text editor to be used.

About FlexMR

We are The Insights Empowerment Company. We help research, product and marketing teams drive informed decisions with efficient, scalable & impactful insight.

About Emily James

As a professional copywriter, Emily brings our global vision to life through a broad range of industry-leading content.

Stay up to date

You might also like....

Market Research Room 101: Round 2

On Thursday 9th May 2024, Team Russell and Team Hudson duelled in a panel debate modelled off the popular TV show Room 101. This mock-gameshow-style panel, hosted by Keen as Mustard Marketing's Lucy D...

Delivering AI Powered Qual at Scale...

It’s safe to say artificial intelligence, and more specifically generative AI, has had a transformative impact on the market research sector. From the contentious emergence of synthetic participants t...

How to Use Digital Ethnography and ...

In one way or another, we’ve all encountered social media spaces. Whether you’ve had a Facebook account since it first landed on the internet, created different accounts to keep up with relatives duri...

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Quantitative Research Questions

- Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

Jump to DSE Guide

Purpose statement overview.

The purpose statement succinctly explains (on no more than 1 page) the objectives of the research study. These objectives must directly address the problem and help close the stated gap. Expressed as a formula:

Good purpose statements:

- Flow from the problem statement and actually address the proposed problem

- Are concise and clear

- Answer the question ‘Why are you doing this research?’

- Match the methodology (similar to research questions)

- Have a ‘hook’ to get the reader’s attention

- Set the stage by clearly stating, “The purpose of this (qualitative or quantitative) study is to ...

In PhD studies, the purpose usually involves applying a theory to solve the problem. In other words, the purpose tells the reader what the goal of the study is, and what your study will accomplish, through which theoretical lens. The purpose statement also includes brief information about direction, scope, and where the data will come from.

A problem and gap in combination can lead to different research objectives, and hence, different purpose statements. In the example from above where the problem was severe underrepresentation of female CEOs in Fortune 500 companies and the identified gap related to lack of research of male-dominated boards; one purpose might be to explore implicit biases in male-dominated boards through the lens of feminist theory. Another purpose may be to determine how board members rated female and male candidates on scales of competency, professionalism, and experience to predict which candidate will be selected for the CEO position. The first purpose may involve a qualitative ethnographic study in which the researcher observes board meetings and hiring interviews; the second may involve a quantitative regression analysis. The outcomes will be very different, so it’s important that you find out exactly how you want to address a problem and help close a gap!

The purpose of the study must not only align with the problem and address a gap; it must also align with the chosen research method. In fact, the DP/DM template requires you to name the research method at the very beginning of the purpose statement. The research verb must match the chosen method. In general, quantitative studies involve “closed-ended” research verbs such as determine , measure , correlate , explain , compare , validate , identify , or examine ; whereas qualitative studies involve “open-ended” research verbs such as explore , understand , narrate , articulate [meanings], discover , or develop .

A qualitative purpose statement following the color-coded problem statement (assumed here to be low well-being among financial sector employees) + gap (lack of research on followers of mid-level managers), might start like this:

In response to declining levels of employee well-being, the purpose of the qualitative phenomenology was to explore and understand the lived experiences related to the well-being of the followers of novice mid-level managers in the financial services industry. The levels of follower well-being have been shown to correlate to employee morale, turnover intention, and customer orientation (Eren et al., 2013). A combined framework of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory and the employee well-being concept informed the research questions and supported the inquiry, analysis, and interpretation of the experiences of followers of novice managers in the financial services industry.

A quantitative purpose statement for the same problem and gap might start like this:

In response to declining levels of employee well-being, the purpose of the quantitative correlational study was to determine which leadership factors predict employee well-being of the followers of novice mid-level managers in the financial services industry. Leadership factors were measured by the Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) assessment framework by Mantlekow (2015), and employee well-being was conceptualized as a compound variable consisting of self-reported turnover-intent and psychological test scores from the Mental Health Survey (MHS) developed by Johns Hopkins University researchers.

Both of these purpose statements reflect viable research strategies and both align with the problem and gap so it’s up to the researcher to design a study in a manner that reflects personal preferences and desired study outcomes. Note that the quantitative research purpose incorporates operationalized concepts or variables ; that reflect the way the researcher intends to measure the key concepts under study; whereas the qualitative purpose statement isn’t about translating the concepts under study as variables but instead aim to explore and understand the core research phenomenon.

Best Practices for Writing your Purpose Statement

Always keep in mind that the dissertation process is iterative, and your writing, over time, will be refined as clarity is gradually achieved. Most of the time, greater clarity for the purpose statement and other components of the Dissertation is the result of a growing understanding of the literature in the field. As you increasingly master the literature you will also increasingly clarify the purpose of your study.

The purpose statement should flow directly from the problem statement. There should be clear and obvious alignment between the two and that alignment will get tighter and more pronounced as your work progresses.

The purpose statement should specifically address the reason for conducting the study, with emphasis on the word specifically. There should not be any doubt in your readers’ minds as to the purpose of your study. To achieve this level of clarity you will need to also insure there is no doubt in your mind as to the purpose of your study.

Many researchers benefit from stopping your work during the research process when insight strikes you and write about it while it is still fresh in your mind. This can help you clarify all aspects of a dissertation, including clarifying its purpose.

Your Chair and your committee members can help you to clarify your study’s purpose so carefully attend to any feedback they offer.

The purpose statement should reflect the research questions and vice versa. The chain of alignment that began with the research problem description and continues on to the research purpose, research questions, and methodology must be respected at all times during dissertation development. You are to succinctly describe the overarching goal of the study that reflects the research questions. Each research question narrows and focuses the purpose statement. Conversely, the purpose statement encompasses all of the research questions.

Identify in the purpose statement the research method as quantitative, qualitative or mixed (i.e., “The purpose of this [qualitative/quantitative/mixed] study is to ...)

Avoid the use of the phrase “research study” since the two words together are redundant.

Follow the initial declaration of purpose with a brief overview of how, with what instruments/data, with whom and where (as applicable) the study will be conducted. Identify variables/constructs and/or phenomenon/concept/idea. Since this section is to be a concise paragraph, emphasis must be placed on the word brief. However, adding these details will give your readers a very clear picture of the purpose of your research.

Developing the purpose section of your dissertation is usually not achieved in a single flash of insight. The process involves a great deal of reading to find out what other scholars have done to address the research topic and problem you have identified. The purpose section of your dissertation could well be the most important paragraph you write during your academic career, and every word should be carefully selected. Think of it as the DNA of your dissertation. Everything else you write should emerge directly and clearly from your purpose statement. In turn, your purpose statement should emerge directly and clearly from your research problem description. It is good practice to print out your problem statement and purpose statement and keep them in front of you as you work on each part of your dissertation in order to insure alignment.

It is helpful to collect several dissertations similar to the one you envision creating. Extract the problem descriptions and purpose statements of other dissertation authors and compare them in order to sharpen your thinking about your own work. Comparing how other dissertation authors have handled the many challenges you are facing can be an invaluable exercise. Keep in mind that individual universities use their own tailored protocols for presenting key components of the dissertation so your review of these purpose statements should focus on content rather than form.

Once your purpose statement is set it must be consistently presented throughout the dissertation. This may require some recursive editing because the way you articulate your purpose may evolve as you work on various aspects of your dissertation. Whenever you make an adjustment to your purpose statement you should carefully follow up on the editing and conceptual ramifications throughout the entire document.

In establishing your purpose you should NOT advocate for a particular outcome. Research should be done to answer questions not prove a point. As a researcher, you are to inquire with an open mind, and even when you come to the work with clear assumptions, your job is to prove the validity of the conclusions reached. For example, you would not say the purpose of your research project is to demonstrate that there is a relationship between two variables. Such a statement presupposes you know the answer before your research is conducted and promotes or supports (advocates on behalf of) a particular outcome. A more appropriate purpose statement would be to examine or explore the relationship between two variables.

Your purpose statement should not imply that you are going to prove something. You may be surprised to learn that we cannot prove anything in scholarly research for two reasons. First, in quantitative analyses, statistical tests calculate the probability that something is true rather than establishing it as true. Second, in qualitative research, the study can only purport to describe what is occurring from the perspective of the participants. Whether or not the phenomenon they are describing is true in a larger context is not knowable. We cannot observe the phenomenon in all settings and in all circumstances.

Writing your Purpose Statement

It is important to distinguish in your mind the differences between the Problem Statement and Purpose Statement.

The Problem Statement is why I am doing the research

The Purpose Statement is what type of research I am doing to fit or address the problem

The Purpose Statement includes:

- Method of Study

- Specific Population

Remember, as you are contemplating what to include in your purpose statement and then when you are writing it, the purpose statement is a concise paragraph that describes the intent of the study, and it should flow directly from the problem statement. It should specifically address the reason for conducting the study, and reflect the research questions. Further, it should identify the research method as qualitative, quantitative, or mixed. Then provide a brief overview of how the study will be conducted, with what instruments/data collection methods, and with whom (subjects) and where (as applicable). Finally, you should identify variables/constructs and/or phenomenon/concept/idea.

Qualitative Purpose Statement

Creswell (2002) suggested for writing purpose statements in qualitative research include using deliberate phrasing to alert the reader to the purpose statement. Verbs that indicate what will take place in the research and the use of non-directional language that do not suggest an outcome are key. A purpose statement should focus on a single idea or concept, with a broad definition of the idea or concept. How the concept was investigated should also be included, as well as participants in the study and locations for the research to give the reader a sense of with whom and where the study took place.

Creswell (2003) advised the following script for purpose statements in qualitative research:

“The purpose of this qualitative_________________ (strategy of inquiry, such as ethnography, case study, or other type) study is (was? will be?) to ________________ (understand? describe? develop? discover?) the _________________(central phenomenon being studied) for ______________ (the participants, such as the individual, groups, organization) at __________(research site). At this stage in the research, the __________ (central phenomenon being studied) will be generally defined as ___________________ (provide a general definition)” (pg. 90).

Quantitative Purpose Statement

Creswell (2003) offers vast differences between the purpose statements written for qualitative research and those written for quantitative research, particularly with respect to language and the inclusion of variables. The comparison of variables is often a focus of quantitative research, with the variables distinguishable by either the temporal order or how they are measured. As with qualitative research purpose statements, Creswell (2003) recommends the use of deliberate language to alert the reader to the purpose of the study, but quantitative purpose statements also include the theory or conceptual framework guiding the study and the variables that are being studied and how they are related.

Creswell (2003) suggests the following script for drafting purpose statements in quantitative research:

“The purpose of this _____________________ (experiment? survey?) study is (was? will be?) to test the theory of _________________that _________________ (compares? relates?) the ___________(independent variable) to _________________________(dependent variable), controlling for _______________________ (control variables) for ___________________ (participants) at _________________________ (the research site). The independent variable(s) _____________________ will be generally defined as _______________________ (provide a general definition). The dependent variable(s) will be generally defined as _____________________ (provide a general definition), and the control and intervening variables(s), _________________ (identify the control and intervening variables) will be statistically controlled in this study” (pg. 97).

Sample Purpose Statements

- The purpose of this qualitative study was to determine how participation in service-learning in an alternative school impacted students academically, civically, and personally. There is ample evidence demonstrating the failure of schools for students at-risk; however, there is still a need to demonstrate why these students are successful in non-traditional educational programs like the service-learning model used at TDS. This study was unique in that it examined one alternative school’s approach to service-learning in a setting where students not only serve, but faculty serve as volunteer teachers. The use of a constructivist approach in service-learning in an alternative school setting was examined in an effort to determine whether service-learning participation contributes positively to academic, personal, and civic gain for students, and to examine student and teacher views regarding the overall outcomes of service-learning. This study was completed using an ethnographic approach that included observations, content analysis, and interviews with teachers at The David School.

- The purpose of this quantitative non-experimental cross-sectional linear multiple regression design was to investigate the relationship among early childhood teachers’ self-reported assessment of multicultural awareness as measured by responses from the Teacher Multicultural Attitude Survey (TMAS) and supervisors’ observed assessment of teachers’ multicultural competency skills as measured by the Multicultural Teaching Competency Scale (MTCS) survey. Demographic data such as number of multicultural training hours, years teaching in Dubai, curriculum program at current school, and age were also examined and their relationship to multicultural teaching competency. The study took place in the emirate of Dubai where there were 14,333 expatriate teachers employed in private schools (KHDA, 2013b).

- The purpose of this quantitative, non-experimental study is to examine the degree to which stages of change, gender, acculturation level and trauma types predicts the reluctance of Arab refugees, aged 18 and over, in the Dearborn, MI area, to seek professional help for their mental health needs. This study will utilize four instruments to measure these variables: University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA: DiClemente & Hughes, 1990); Cumulative Trauma Scale (Kira, 2012); Acculturation Rating Scale for Arabic Americans-II Arabic and English (ARSAA-IIA, ARSAA-IIE: Jadalla & Lee, 2013), and a demographic survey. This study will examine 1) the relationship between stages of change, gender, acculturation levels, and trauma types and Arab refugees’ help-seeking behavior, 2) the degree to which any of these variables can predict Arab refugee help-seeking behavior. Additionally, the outcome of this study could provide researchers and clinicians with a stage-based model, TTM, for measuring Arab refugees’ help-seeking behavior and lay a foundation for how TTM can help target the clinical needs of Arab refugees. Lastly, this attempt to apply the TTM model to Arab refugees’ condition could lay the foundation for future research to investigate the application of TTM to clinical work among refugee populations.

- The purpose of this qualitative, phenomenological study is to describe the lived experiences of LLM for 10 EFL learners in rural Guatemala and to utilize that data to determine how it conforms to, or possibly challenges, current theoretical conceptions of LLM. In accordance with Morse’s (1994) suggestion that a phenomenological study should utilize at least six participants, this study utilized semi-structured interviews with 10 EFL learners to explore why and how they have experienced the motivation to learn English throughout their lives. The methodology of horizontalization was used to break the interview protocols into individual units of meaning before analyzing these units to extract the overarching themes (Moustakas, 1994). These themes were then interpreted into a detailed description of LLM as experienced by EFL students in this context. Finally, the resulting description was analyzed to discover how these learners’ lived experiences with LLM conformed with and/or diverged from current theories of LLM.

- The purpose of this qualitative, embedded, multiple case study was to examine how both parent-child attachment relationships are impacted by the quality of the paternal and maternal caregiver-child interactions that occur throughout a maternal deployment, within the context of dual-military couples. In order to examine this phenomenon, an embedded, multiple case study was conducted, utilizing an attachment systems metatheory perspective. The study included four dual-military couples who experienced a maternal deployment to Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) or Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) when they had at least one child between 8 weeks-old to 5 years-old. Each member of the couple participated in an individual, semi-structured interview with the researcher and completed the Parenting Relationship Questionnaire (PRQ). “The PRQ is designed to capture a parent’s perspective on the parent-child relationship” (Pearson, 2012, para. 1) and was used within the proposed study for this purpose. The PRQ was utilized to triangulate the data (Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012) as well as to provide some additional information on the parents’ perspective of the quality of the parent-child attachment relationship in regards to communication, discipline, parenting confidence, relationship satisfaction, and time spent together (Pearson, 2012). The researcher utilized the semi-structured interview to collect information regarding the parents' perspectives of the quality of their parental caregiver behaviors during the deployment cycle, the mother's parent-child interactions while deployed, the behavior of the child or children at time of reunification, and the strategies or behaviors the parents believe may have contributed to their child's behavior at the time of reunification. The results of this study may be utilized by the military, and by civilian providers, to develop proactive and preventive measures that both providers and parents can implement, to address any potential adverse effects on the parent-child attachment relationship, identified through the proposed study. The results of this study may also be utilized to further refine and understand the integration of attachment theory and systems theory, in both clinical and research settings, within the field of marriage and family therapy.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Problem Statement

- Next: Conceptual Framework >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 8:25 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchtools

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2021

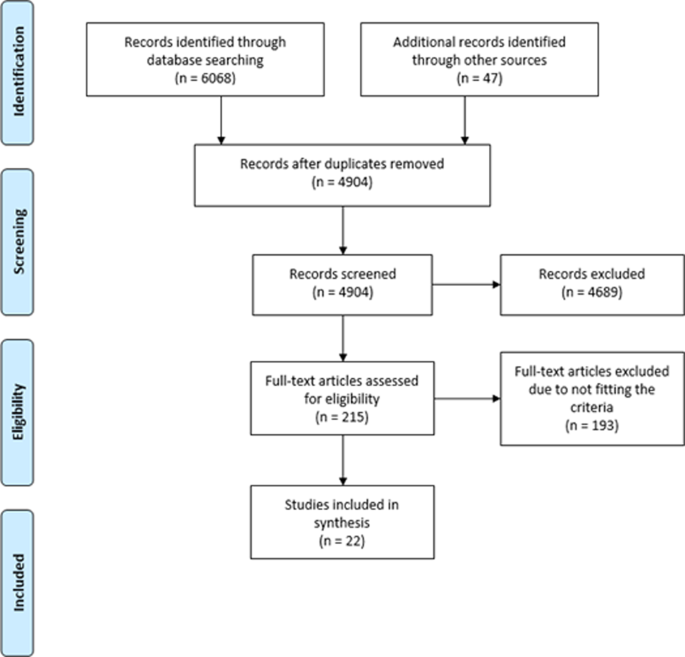

Use and effectiveness of policy briefs as a knowledge transfer tool: a scoping review

- Diana Arnautu 1 &

- Christian Dagenais 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 211 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

17 Citations

100 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health humanities

- Medical humanities

There is a significant gap between researchers’ production of evidence and its use by policymakers. Several knowledge transfer strategies have emerged in the past years to promote the use of research. One of those strategies is the policy brief; a short document synthesizing the results of one or multiple studies. This scoping study aims to identify the use and effectiveness of policy briefs as a knowledge transfer strategy. Twenty-two empirical articles were identified, spanning 35 countries. Results show that policy briefs are considered generally useful, credible and easy to understand. The type of audience is an essential component to consider when writing a policy brief. Introducing a policy brief sooner rather than later might have a bigger impact since it is more effective in creating a belief rather than changing one. The credibility of the policy brief’s author is also a factor taken into consideration by decision-makers. Further research needs to be done to evaluate the various forms of uses of policy briefs by decision-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Barriers and facilitators of translating health research findings into policy in sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review

Insights from a cross-sector review on how to conceptualise the quality of use of research evidence

Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice

Introduction.

Improving well-being and reducing health-related inequalities is a challenging endeavor for public policymakers. They must consider the nature and significance of the issue, the proposed interventions and their pros and cons such as their impact and acceptability (Lavis et al., 2012 ; Mays et al., 2005 ). Policymakers are members of a government department, legislature or other organization responsible for devising new regulations and laws (Cambridge University Press, 2019 ). They face the challenge of finding the best solutions to multiple health-related crises while being the most time and cost-effective possible. Limited by time and smothered by an overwhelming amount of information, some policymakers are likely to use cognitive shortcuts by selecting the “evidence” most appropriate to their political leanings (Baekgaard et al., 2019 ; Cairney et al., 2019 ; Oliver and Cairney, 2019 ).

To prevent snap decisions in policymaking, it is essential to develop tools to facilitate the dissemination and use of empirical research. Evidence-informed solutions might be an effective way to address these complicated questions since they derive knowledge from accurate and robust evidence instead of beliefs and provide a more holistic view of a problem. Although it may be possible for different stakeholders to agree on certain matters, a consensus is uncommon (Nutley et al., 2013 ). Using research evidence allows policymakers to decrease their bias towards an intervention’s perceived effectiveness. This leads to more confidence among policymakers on what to expect from an intervention as their decisions are guided by evidence (Lavis et al., 2004 ). However, trying to integrate research findings into the policy-making process comes with a whole new set of challenges, both for researchers and policymakers.

Barriers to evidence-informed policy

Barriers to evidence-informed policy can be defined in three categories: the research evidence is not available in an accessible format for the policymaker, the evidence is disregarded for political or ideological reasons and the evidence is not applicable to the political context (Hawkins and Pakhurst, 2016 ; Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ).

The first category of barriers refers to the availability and the type of evidence. The vast amount of information policymakers need to keep up-to-date in specific fields is a particular challenge to this barrier, leading to policymakers being frequently overwhelmed with the amount of information they need to go through regarding each case (Orandi and Locke, 2020 ). Decision-makers have reported a lack of competencies in finding, evaluating, interpreting or using certain evidence such as systematic reviews in their decision-making, leading to difficulty in accessing these reviews and identifying the key messages quickly (Tricco et al., 2015 ). Although policymakers use a broader variety of forms of evidence than previously examined in the literature, scholars have rarely been consulted and research evidence has rarely been seen as directly applicable (Oliver and de Vocht, 2017 ). The lack of awareness on the importance of research evidence and on the ways to access these resources also contribute to the gap between research and policy (Oliver et al., 2014 ; van de Goor et al., 2017 ). Some other frequently reported barriers to evidence use in policymaking were the poor access to timely, quality and relevant research evidence as well as the limited collaboration between policymakers and researchers (Oliver et al., 2014 ; Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ; van de Goor et al., 2017 ). Given the fact that research is only one input amongst all the others that policymakers must consider in their decision, it is no surprise that policymakers may disregard research evidence in favor of other sources of information (Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ).

The second category of barriers refers to policymakers’ ideology regarding research evidence and the presence of biases. Resistance to change and a lack of willingness by some policymakers to use research are two factors present when attempting to bridge the gap. This could be explained by certain sub-cultures of policymaking that grants little importance to evidence-informed solutions or by certain policymakers prioritizing their own opinion when research findings go against their expectations or against current policy (Koon et al., 2013 ; Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ). Policymakers tend to interpret new information based on their past attitudes and beliefs, much like the general population (Baekgaard et al., 2019 ). It also does not seem to persuade policymakers with beliefs opposed to the evidence, rather it increases the effect of attitudes on the interpretation of information by policymakers (Baekgaard et al., 2019 ). This highlights the importance of finding methods to disseminate tailored evidence in a way that policymakers will be open to receive and consider (Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ).

The third category of barriers refers to the evidence produced not always being tailor-made for application in different contexts (Uzochukwu et al., 2016 ; WHO, 2004 ). Indeed, the political context is an undeniable factor in the use of evidence in policymaking. Political and institutional factors such as the level of state centralization and democratization, the influence of external organizations and donors, the organization of bureaucracies and the social norms and values, can all affect the use of evidence in policy (Liverani et al., 2013 ). The elaboration of new policies implies making choices between different priorities while taking into consideration the limited resources available (Hawkins and Pakhurst, 2016 ). The evidence of research can always be contested or balanced with the potential negative consequences of the intervention in another domain, such as a health-care intervention having larger consequences on the economy. Even if the effectiveness of an intervention can be proved beyond doubt, this given issue might not be a priority for decision-makers, or it might involve unrealistic resources that would rather be granted to other issues. Policymakers need to stay aware of the political priorities identified and the citizens they need to justify their decisions to. In this sense, politics and institutions are not a barrier to the use of research but rather they are the context under which evidence must respond to (Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ; Hawkins and Parkhurst, 2016 ).

Summaries to prevent information overload

A great deal of research evidence has been developed but not enough of it is being disseminated in effective ways (Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ). Offering a summary of research results in an accessible format could facilitate policy discussion and ultimately improve the use of research and help policymakers with their decisions (Arcury et al., 2017 ; Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ). In this age of information overload, when too much information is provided, one can have trouble discerning what is most important and make a decision. It is not unlikely that policymakers will, after a brief glance, discard a large amount of information given to them (Beynon et al., 2012 ; Yang et al., 2003 ). Decision-makers oftentimes criticize the length and overly dense contents of research documents (Dagenais and Ridde, 2018 ; Oliver et al., 2014 ). Hence, summaries of research results could increase the odds of decision-makers reading and therefore using the evidence proposed by researchers.