- Trying to Conceive

- Signs & Symptoms

- Pregnancy Tests

- Fertility Testing

- Fertility Treatment

- Weeks & Trimesters

- Staying Healthy

- Preparing for Baby

- Complications & Concerns

- Pregnancy Loss

- Breastfeeding

- School-Aged Kids

- Raising Kids

- Personal Stories

- Everyday Wellness

- Safety & First Aid

- Immunizations

- Food & Nutrition

- Active Play

- Pregnancy Products

- Nursery & Sleep Products

- Nursing & Feeding Products

- Clothing & Accessories

- Toys & Gifts

- Ovulation Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- How to Talk About Postpartum Depression

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

How Teens Use Technology to Cheat in School

Why teens cheat, text messaging during tests, storing notes, copying and pasting, social media, homework apps and websites, talk to your teen.

- Expectations and Consequences

When you were in school, teens who were cheating were likely looking at a neighbor’s paper or copying a friend’s homework. The most high-tech attempts to cheat may have involved a student who wrote the answers to a test on the cover of their notebook.

Cheating in today’s world has evolved, and unfortunately, become pervasive. Technology makes cheating all too tempting, common, and easy to pull off. Not only can kids use their phones to covertly communicate with each other, but they can also easily look up answers or get their work done on the Internet.

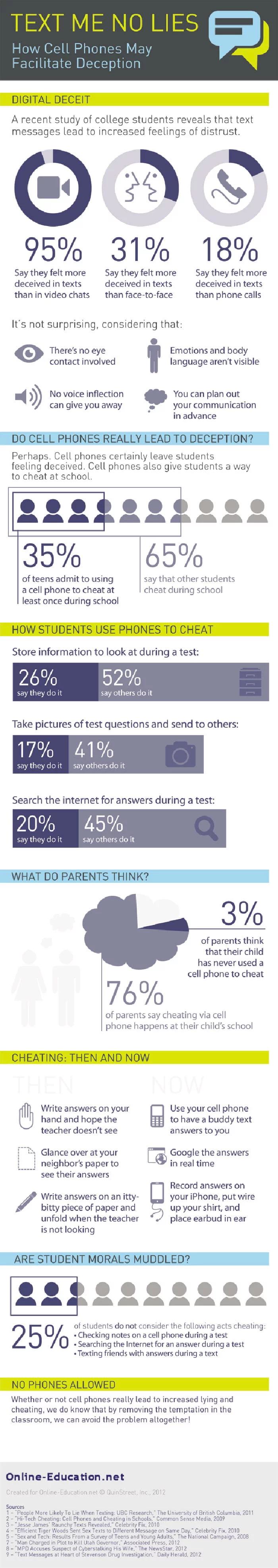

In one study, a whopping 35% of teens admit to using their smartphones to cheat on homework or tests. 65% of the same surveyed students also stated they have seen others use their phones to cheat in school. Other research has also pointed to widespread academic indiscretions among teens.

Sadly, academic dishonesty often is easily normalized among teens. Many of them may not even recognize that sharing answers, looking up facts online, consulting a friend, or using a homework app could constitute cheating. It may be a slippery slope as well, with kids fudging the honesty line a tiny bit here or there before beginning full-fledged cheating.

For those who are well aware that their behavior constitutes cheating, the academic pressure to succeed may outweigh the risk of getting caught. They may want to get into top colleges or earn scholarships for their grades. Some teens may feel that the best way to gain a competitive edge is by cheating.

Other students may just be looking for shortcuts. It may seem easier to cheat rather than look up the answers, figure things out in their heads, or study for a test. Plus, it can be rationalized that they are "studying" on their phone rather than actually cheating.

Teens with busy schedules may be especially tempted to cheat. The demands of sports, a part-time job , family commitments, or other after-school responsibilities can make academic dishonesty seem like a time-saving option.

Sometimes, there’s also a fairly low risk of getting caught. Some teachers rely on an honor system, and in some cases, technology has evolved faster than school policies. Many teachers lack the resources to detect academic dishonesty in the classroom. However, increasingly, there are programs and methods that let teachers scan student work for plagiarism.

Finally, some teens get confused about their family's values and may forget that learning is the goal of schooling rather than just the grades they get. They may assume that their parent would rather they cheat than get a bad grade—or they fear disappointing them. Plus, they see so many other kids cheating that it may start to feel expected.

It’s important to educate yourself about the various ways that today’s teens are cheating so you can be aware of the temptations your teen may face. Let's look at how teens are using phones and technology to cheat.

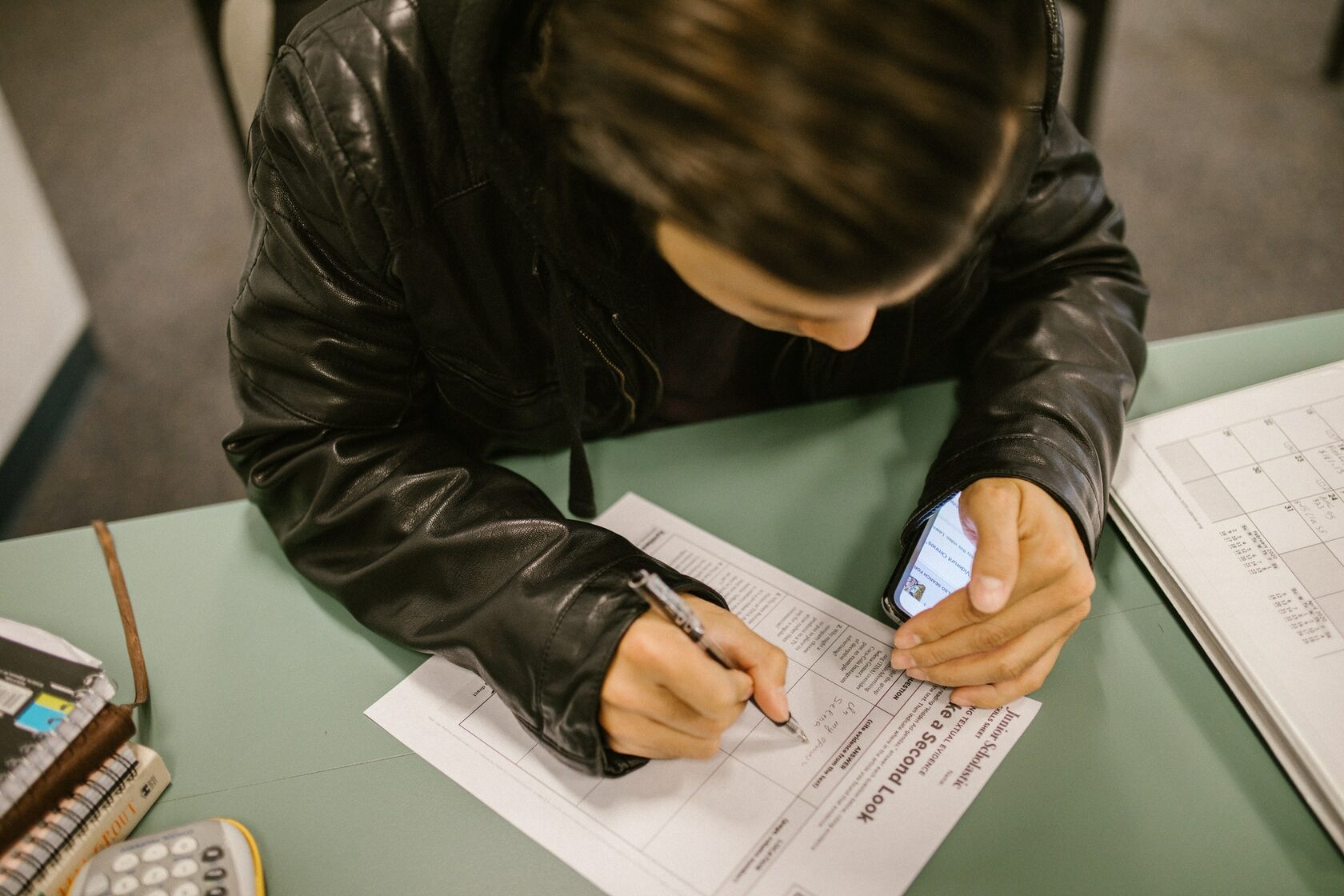

Texting is one of the fastest ways for students to get answers to test questions from other students in the room—it's become the modern equivalent of note passing. Teens hide their smartphones on their seats and text one another, looking down to view responses while the teacher isn't paying attention.

Teens often admit the practice is easy to get away with even when phones aren't allowed (provided the teacher isn't walking around the room to check for cellphones).

Some teens store notes for test time on their cell phones and access these notes during class. As with texting, this is done on the sly, hiding the phone from view. The internet offers other unusual tips for cheating with notes, too.

For example, several sites guide teens to print their notes out in the nutrition information portion of a water bottle label, providing a downloadable template to do so. Teens replace the water or beverage bottle labels with their own for a nearly undetectable setup, especially in a large class. This, of course, only works if the teacher allows beverages during class.

Rather than conduct research to find sources, some students are copying and pasting material. They may plagiarize a report by trying to pass off a Wikipedia article as their own paper, for example.

Teachers may get wise to this type of plagiarism by doing a simple internet search of their own. Pasting a few sentences of a paper into a search engine can help teachers identify if the content was taken from a website.

A few websites offer complete research papers for free based on popular subjects or common books. Others allow students to purchase a paper. Then, a professional writer, or perhaps even another student, will complete the report for them.

Teachers may be able to detect this type of cheating when a student’s paper seems to be written in a different voice. A perfectly polished paper may indicate a ninth-grade student’s work isn’t their own. Teachers may also just be able to tell that the paper just doesn't sound like the student who turned it in.

Crowdsourced sites such as Homework Helper also provide their share of homework answers. Students simply ask a question and others chime in to give them the answers.

Teenagers use social media to help one another on tests, too. It only takes a second to capture a picture of an exam when the teacher isn’t looking.

That picture may then be shared with friends who want a sneak peek of the test before they take it. The photo may be uploaded to a special Facebook group or simply shared via text message. Then, other teens can look up the answers to the exam once they know the questions ahead of time.

While many tech-savvy cheating methods aren’t all that surprising, some methods require very little effort on the student’s part. Numerous free math apps such as Photomath allow a student to take a picture of the math problem. The app scans the problem and spits out the answers, even for complex algebra problems. That means students can quickly complete the homework without actually understanding the material.

Other apps, such as HWPic , send a picture of the problem to an actual tutor, who offers a step-by-step solution to the problem. While some students may use this to better understand their homework, others just copy down the answers, complete with the steps that justify the answer.

Websites such as Cymayth and Wolfram Alpha solve math problems on the fly—Wolfram can even handle college-level math problems. While the sites and apps state they are designed to help students figure out how to do the math, they are also used by students who would rather have the answers without the effort required to think them through on their own.

Other apps quickly translate foreign languages. Rather than have to decipher what a recording says or translate written words, apps can easily translate the information for the student.

The American Academy of Pediatrics encourages parents to talk to teens about cheating and their expectations for honesty, school, and communication. Many parents may have never had a serious talk with their child about cheating. It may not even come up unless their child gets caught cheating. Some parents may not think it’s necessary to discuss because they assume their child would never cheat.

However, clearly, the statistics show that many kids do engage in academic discretions. So, don’t assume your child wouldn’t cheat. Often, "good kids" and "honest kids" make bad decisions. Make it clear to your teen that you value hard work and honesty.

Talk to your teen regularly about the dangers of cheating. Make it clear that cheaters tend not to get ahead in life.

Discuss the academic and social consequences of cheating, too. For example, your teen might get a zero or get kicked out of a class for cheating. Even worse, other people may not believe them when they tell the truth if they become known as dishonest or a cheater. It could also go on their transcripts, which could impair their academic future.

It’s important for your teen to understand that cheating—and heavy cell phone use—can take a toll on their mental health , as well. Additionally, studies make clear that poor mental health, particularly relating to self-image, stress levels, and academic engagement, makes kids more likely to indulge in academic dishonestly. So, be sure to consider the whole picture of why your child may be cheating or feel tempted to cheat.

A 2016 study found that cheaters actually cheat themselves out of happiness. Although they may think the advantage they gain by cheating will make them happier, research shows cheating causes people to feel worse.

Establish Clear Expectations and Consequences

Deciphering what constitutes cheating in today's world can be a little tricky. If your teen uses a homework app to get help, is that cheating? What if they use a website that translates Spanish into English? Also, note that different teachers have different expectations and will allow different levels of outside academic support.

Expectations

So, you may need to take it on a case-by-case basis to determine whether your teen's use of technology enhances or hinders their learning and/or is approved by their teacher. When in doubt, you can always ask the teacher directly if using technology for homework or other projects is acceptable.

To help prevent cheating, take a firm, clear stance so that your child understands your values and expectations. Also, make sure they have any needed supports in place so that they aren't tempted to cheat due to academic frustrations or challenges.

Tell your teen, ideally before an incident of academic dishonesty occurs, that you don’t condone cheating of any kind and you’d prefer a bad grade over dishonesty.

Stay involved in your teen’s education. Know what type of homework your teen is doing and be aware of the various ways your teen may be tempted to use their laptop or smartphone to cheat.

To encourage honesty in your child, help them develop a healthy moral compass by being an honest role model. If you cheat on your taxes or lie about your teen’s age to get into the movies for a cheaper price, you may send them the message that cheating is acceptable.

Consequences

If you do catch your teen cheating, take action . Just because your teen insists, “Everyone uses an app to get homework done,” don’t blindly believe it or let that give them a free pass. Instead, reiterate your expectations and provide substantive consequences. These may include removing phone privileges for a specified period of time. Sometimes the loss of privileges —such as your teen’s electronics—for 24 hours is enough to send a clear message.

Allow your teen to face consequences at school as well. If they get a zero on a test for cheating, don’t argue with the teacher. Instead, let your teen know that cheating has serious ramifications—and that they will not get away with this behavior.

However, do find out why your teen is cheating. Consider if they're over-scheduled or afraid they can’t keep up with their peers. Are they struggling to understand the material? Do they feel unhealthy pressure to excel? Ask questions to gain an understanding so you can help prevent cheating in the future and ensure they can succeed on their own.

It’s better for your teen to learn lessons about cheating now, rather than later in life. Dishonesty can have serious consequences. Cheating in college could get your teen expelled and cheating at a future job could get them fired or it could even lead to legal action. Cheating on a future partner could lead to the end of the relationship.

A Word From Verywell

Make sure your teen knows that honesty and focusing on learning rather than only on getting "good grades," at all costs, really is the best policy. Talk about honesty often and validate your teen’s feelings when they're frustrated with schoolwork—and the fact that some students who cheat seem to get ahead without getting caught. Assure them that ultimately, people who cheat truly are cheating themselves.

Common Sense Media. It's ridiculously easy for kids to cheat now .

Common Sense Media. 35% of kids admit to using cell phones to cheat .

Isakov M, Tripathy A. Behavioral correlates of cheating: environmental specificity and reward expectation . PLoS One . 2017;12(10):e0186054. Published 2017 Oct 26. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186054

Marksteiner T, Nishen AK, Dickhäuser O. Students' perception of teachers' reference norm orientation and cheating in the classroom . Front Psychol . 2021;12:614199. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.614199

Khan ZR, Sivasubramaniam S, Anand P, Hysaj A. ‘ e’-thinking teaching and assessment to uphold academic integrity: lessons learned from emergency distance learning . International Journal for Educational Integrity . 2021;17(1):17. doi:10.1007/s40979-021-00079-5

Farnese ML, Tramontano C, Fida R, Paciello M. Cheating behaviors in academic context: does academic moral disengagement matter? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences . 2011;29:356-365. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.250

Pew Research Center. How parents and schools regulate teens' mobile phones .

Mohammad Abu Taleb BR, Coughlin C, Romanowski MH, Semmar Y, Hosny KH. Students, mobile devices and classrooms: a comparison of US and Arab undergraduate students in a middle eastern university . HES . 2017;7(3):181. doi:10.5539/hes.v7n3p181

Gasparyan AY, Nurmashev B, Seksenbayev B, Trukhachev VI, Kostyukova EI, Kitas GD. Plagiarism in the context of education and evolving detection strategies . J Korean Med Sci . 2017;32(8):1220-1227. doi:10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1220

Bretag T. Challenges in addressing plagiarism in education . PLoS Med . 2013;10(12):e1001574. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001574

American Academy of Pediatrics. Competition and cheating .

Korn L, Davidovitch N. The Profile of academic offenders: features of students who admit to academic dishonesty . Med Sci Monit . 2016;22:3043-3055. doi:10.12659/msm.898810

Abi-Jaoude E, Naylor KT, Pignatiello A. Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health . CMAJ . 2020;192(6):E136-E141. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190434

Stets JE, Trettevik R. Happiness and Identities . Soc Sci Res. 2016;58:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.04.011

Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015 . Pew Research Center.

By Amy Morin, LCSW Amy Morin, LCSW, is the Editor-in-Chief of Verywell Mind. She's also a psychotherapist, an international bestselling author of books on mental strength and host of The Verywell Mind Podcast. She delivered one of the most popular TEDx talks of all time.

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

- Get the app

- Media Choice

- Digital Equity

- Digital Literacy and Citizenship

- Tech Accountability

- Healthy Childhood

- 20 Years of Impact

The Healthy Young Minds Campaign

AI Ratings and Reviews

- Our Current Research

- Past Research

- Archived Datasets

Constant Companion: A Week in the Life of a Young Person's Smartphone Use

2023 State of Kids' Privacy

- Press Releases

- Our Experts

- Our Perspectives

- Public Filings and Letters

Common Sense Media Announces Framework for First-of-Its-Kind AI Ratings System

Protecting Kids' Digital Privacy Is Now Easier Than Ever

- How We Work

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Meet Our Team

- Board of Directors

- Board of Advisors

- Our Partners

- How We Rate and Review Media

- How We Rate and Review for Learning

- Our Offices

- Join as a Parent

- Join as an Educator

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Request a Speaker

- We're Hiring

35% of Teens Admit to Using Cell Phones to Cheat

National Poll Reveals Students’ Attitudes Toward Hi-Tech Cheating and Highlights Need for Parents and Educators to Set Guidelines and Address Consequences

Watch The Early Show segment. Read about this study in USA Today , the Los Angeles Times , and the San Francisco Chronicle .

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – Common Sense Media today released the results of a national poll on the use of digital media for cheating in school. The poll, conducted by The Benenson Strategy Group, revealed that more than 35% of teens admit to cheating with cell phones, and more than half admit to using the Internet to cheat. More importantly, many students don't consider their actions to be cheating at all. The results highlight a real need for parents, educators, and leaders to start a national discussion on digital ethics.

"The results of this poll should be a wake-up call for educators and parents," said James Steyer, CEO and founder of Common Sense Media. "Cell phones and the Internet have been a real game-changer for education and have opened up many avenues for collaboration, creation, and communication. But as this poll shows, the unintended consequence of these versatile technologies is that they've made cheating easier. The call to action is clear: Parents and educators have to be aware of how kids are using technology to cheat and then help our kids understand that the consequences for online cheating are just as serious as offline cheating."

Kids have always found ways to cheat, but the tools they have today are more powerful than ever. In this poll, kids reveal that they're texting each other answers during tests, using notes and information stored on their cell phones during tests, and downloading papers from the Internet to turn in as their own work. Because the digital world is distant, hard to track, and mostly anonymous, kids are less likely to see the consequences of their online actions, especially when they feel they won't get caught.

Common Sense Media is asking parents and educators to step in to help kids develop a set of guidelines to follow in the digital world and to understand that the rules of right and wrong in their offline lives also apply in their online lives. For parents, it's important to understand and embrace the media their kids are using and have a frank discussion about cheating and its implications. Educators need to be hyper aware of the amount of hi-tech cheating happening in their schools, talk to students about it, and establish rules and consequences for the classroom that reflect the reality of our kids' 24/7 media world.

Other key findings from the poll include:

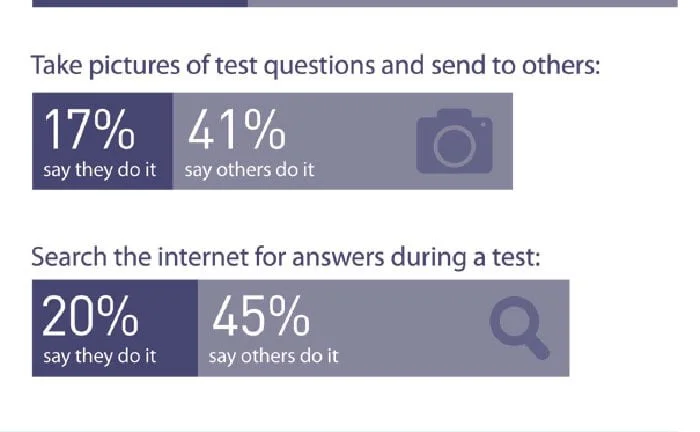

- 41% of teens say that storing notes on a cell phone to access during a test is a serious cheating offense, while 23% don't think it's cheating at all.

- 45% of teens say that texting friends about answers during tests is a serious cheating offense, while 20% say it's not cheating at all.

- 76% of parents say that cell phone cheating happens at their teens' schools, but only 3% believe their own teen has ever used a cell phone to cheat.

- Nearly two-thirds of students with cell phones use them during school, regardless of school policies against it.

- Teens with cell phones send 440 text messages a week and 110 a week while in the classroom.

In conjunction with the poll, Common Sense Media is releasing a policy paper, "Digital Literacy and Citizenship in the 21st Century," which lays out its vision for educating, empowering, and protecting today's kids so they can develop the skills, knowledge, and ethics for today's digital world.

For full poll results, the policy paper, parent tips, and more, visit www.commonsensemedia.org/blog/cheating-goes-hi-tech .

To set up an interview with our experts, please use the contact information below.

About Common Sense Media Common Sense Media is the nation's leading nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the impact of media and entertainment on kids and families. Common Sense Media provides trustworthy ratings and reviews of media and entertainment based on child development criteria created by leading national experts. For more information, visit www.commonsensemedia.org .

About Benenson Strategy Group The Benenson Strategy Group is a nationally recognized strategic research and consulting firm with a reputation for being energetic, fast-paced, and analytically aggressive. Founded in 2001, The Benenson Strategy Group's clients include major nonprofit organizations, President Barack Obama, governors, U.S. Senators, members of Congress, international labor unions, and Fortune 100 companies. For more information, visit www.bsgco.com .

Press Contacts: Marlene Saritzky Vice President of Communications, Common Sense Media 415-553-6768 (direct) 415-713-1241 (cell) [email protected]

Marisa Connolly Communications Manager, Common Sense Media 415-553-6703 (direct) 617-699-4235 (cell) [email protected]

Students Cheating with Cell Phones Statistics [Infographic]

The tendency for students to cheat on tests and exams has existed since the beginning of education.

Cell phones and smartphones however, have only been around for a short period of time and have definitely increase the temptation for high school and college students to use modern technology to cheat in school.

See Also: Facebook’s Effect on Student Grades [Study]

As mobile technology continues to improve, we will continue to address the question of where the line is between cheating and being resourceful.

An infographic ( posted below ) was recently published by Online-Education.net that provides us with some insight on how common it is for students to use their mobile devices to cheat on tests and exams.

Students Cheating with Cell Phones Statistics Highlights:

- 35% of teens admit to using a cell phone at least once to cheat at school.

- 65% of teens report that other students use phones to cheat.

- 26% of students report using smartphones to store information to look at during a test.

- 17% of students report taking pictures of test questions to send to other peers.

- 20% of students admit to searching the interent for answers during a test.

- 76% of parents believe that cheating by using cell phones occurs at their child’s school.

- 25% of students do not consider the following acts cheating:

- Checking notes on a cell phone during a test.

- Searching the internet for an answer during a test.

- Texting friends with answers during a test.

Anson Alexander

I am an author, digital educator and content marketer. I record, edit, and publish content for AnsonAlex.com, provide technical and business services to clients and am an avid self-learner. I have also authored several digital marketing and business courses for LinkedIn Learning (previously Lynda.com).

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Internet Protocol: From IPv4 to IPv6

- Windows 11 File Explorer Tricks: 15 Essential Tips to Boost Your Workflow

- Windows 11 Taskbar Customization: The Ultimate Guide for Control [2024 Edition]

- How to Create Desktop Shortcuts in Windows 11 – The Ultimate Guide [2024 Update]

- Numeric Keypad vs. Compact Keyboard: Considerations to Make (2024 Update)

LAST STRETCH!

You can still support your source of education news this teacher appreciation week.

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

Another problem with shifting education online: cheating

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

When universities went online in response to Covid-19, so did the tests their students took. But one of the people who logged on to take an exam in a pre-med chemistry class at a well-known mid-Atlantic university turned out not to be a student at all.

He was a plant. An imposter. A paid ringer.

Proctors — remote monitors some schools have hired to watch test-takers through their webcams — discovered by reviewing video recordings that this same person had taken tests for at least a dozen different students enrolled at seven universities across the country. The camera caught a spreadsheet tacked to the wall of his workspace with student names, course schedules, remote login information and passwords for websites that could feed him answers.

“We can only imagine what the rate of inappropriate testing activity is when no one is watching.” Scott McFarland, CEO, ProctorU

But he was in Qatar, beyond the reach of any attempts to hold him accountable, according to proctors familiar with the situation. They could not say what happened to the students who allegedly hired him.

It was a dramatic case, but far from unique. Universal online testing has created a documented increase in cheating, often because universities, colleges and testing companies were unprepared for the scale of the transformation or unable or unwilling to pay for safeguards, according to faculty and testing experts.

Even with trained proctors watching test-takers and checking their IDs, cheating is up. Before Covid-19 forced millions of students online, one of the companies that provides that service, ProctorU, caught people cheating on fewer than 1 percent of the 340,000 exams it administered from January through March. During the height of remote testing, the company says, the number of exams it supervised jumped to 1.3 million from April through June, and the cheating rate rose above 8 percent.

“We can only imagine what the rate of inappropriate testing activity is when no one is watching,” said Scott McFarland, CEO of ProctorU.

Related: As students fill summer courses, many ask: Why aren’t all colleges open in the summers?

And for most online test-takers, no one has been watching. One reason is that, as demand for online testing spiked, proctoring capacity was overwhelmed. One company, Examity, suspended its live proctoring services during the demand surge when its 1,000 proctors in India were locked down to curb the spread of the coronavirus there.

Ninety-three percent of instructors think students are more likely to cheat online than in person , according to a survey conducted in May by the publishing and digital education company Wiley. Only a third said they were using some type of proctoring to prevent it. Many colleges and universities moved ahead with online testing without supervision to save money. Others opted instead for less expensive, scaled-down kinds of test security, such as software that can lock a web browser while a student takes a test.

While locking a browser during an exam may help — and about 15 percent of instructors take that step, the Wiley survey found — it can’t stop other forms of cheating.

“You cannot give an exam if it is not proctored,” said Charles M. Krousgrill, a professor of engineering at Purdue, where faculty have been more willing to publicly discuss cheating than their counterparts at many other schools.

When, after the Covid shutdowns, Purdue gave students extra time to take their tests online, said Krousgrill, “there was rampant dishonesty.” He described some students in his department organizing videoconferences and sharing answers. “Once we went to online instruction, we could not watch. [The students] knew it, and knew the game was up for grabs. There were lots of kids who got caught up in that.”

ProctorU, which provides proctors to be sure online test-takers follow the rules, caught people cheating on fewer than 1 percent of exams it administered before the Covid-19 outbreak. Since then the number has jumped to more than 8 percent.

Online tests have also meant a booming business for companies that sell homework and test answers, including Chegg and Course Hero. Students pay subscription fees to get answers to questions on tests or copies of entire tests with answers already provided. The tests are uploaded by other students who have already taken them, in exchange for credits, or answers are quickly provided by “tutors” who work for the sites.

For $9.95 a month, Chegg is offering a new service that provides fast answers to math problems submitted by smartphone camera, step-by-step solution included. Snap a pic, get the answer.

Related: While focus is on fall, students’ choices about college will have a far longer impact

Though these sites have been around since before the pandemic, their use appears to have exploded as more tests are given online. Students used Chegg to allegedly cheat on online exams and tests in the spring at schools including Georgia Tech, Boston University, North Carolina State and Purdue, according to faculty at those institutions and news reports. Universities prefer not to talk about cheating incidents, and federal privacy law limits how much detail they can provide.

At North Carolina State, more than 200 of the 800 students in a single Statistics 311 class were referred for disciplinary action for getting answers to exam questions from a company that offers online tutoring services.

At North Carolina State, more than 200 of the 800 students in a single Statistics 311 class were referred for disciplinary action for using “tutor-provided solutions” to exam questions from Chegg, said Tyler Johnson, the course coordinator.

After the exam, Johnson said, he asked his university to get Chegg to remove the questions, citing copyright law. Chegg did, and furnished a report of users who had either posted or accessed the exam materials.

“I was initially really naive to the extent to which these services are utilized by students,” he said.

Related: Amid pandemic, graduate student workers are winning long-sought contracts

The North Carolina State students have protested in a petition that they didn’t know using Chegg would be considered cheating, and that Johnson showed “no regard to the personal stresses we are enduring and have endured throughout the semester.”

Krousgrill and his colleagues at Purdue asked Chegg to remove their exam materials, too, and asked for help identifying cheaters. They found “a massive number” of students who had used Chegg to get test answers, he said. In one class, Krousgrill said, as many as 60 students out of 250 had done it, and 100 students in a colleague’s class were identified as having used Chegg in a similar fashion.

“I do feel for the students,” Eric Nauman, a professor of engineering and director of the engineering honors program at Purdue, told a web panel for engineering faculty and majors convened to discuss the use of Chegg and similar services for cheating. “If one person starts using it and gets a better grade and these exams are graded on a curve, then they’re in big trouble.”

The number of students who are cheating is almost certainly higher than the number being caught or reported. Research has shown that instructors believe cheating happens much less often than students do , which means they may not be looking for it. When they do find it, many choose to simply give cheaters an F, without reporting the incidents further.

“I do feel for the students. … If one person starts using [an online service] and gets a better grade and these exams are graded on a curve, then they’re in big trouble.” Eric Nauman, professor of engineering and director of the engineering honors program, Purdue University

“I had a conversation with a group of students several months ago,” said James Pitarresi, vice provost at Binghamton University. “And one of the students said, ‘Look, you know, probably 80 percent of the class is looking at Chegg. What are you going to do, expel all of us?’ ”

For most faculty, their only recourse is to ask the companies to remove their exam materials and identify cheaters. But that can take days or even weeks, and happens after the materials have already been shared and an exam is over. It also puts the burden on professors to go site by site, search for their material and ask that it be taken down. “I go through every couple of months and write to them and say, ‘Please take these 200 or 300 items off your site,’ ” said Krousgrill. “But that takes a lot of time.” Especially, he said, when his students are getting answers in 10 minutes.

The cheaters are often way ahead. Message boards at Reddit are filled with warnings to students not to use their school email addresses or real names when signing up for Chegg or similar services. That makes catching cheaters nearly impossible. Even when professors try to preempt Chegg and other sites ahead of time, as one did by embedding a trackable code in test questions, students figured it out and worked around it, according to faculty familiar with the example, although they wouldn’t identify which institution did this.

Chegg, which offers online tutoring services, declined to comment at length. A spokesman said the company supports academic integrity and hasn’t seen “any relative increase in honor code issues since the Covid-19 crisis began.” In an interview with The New York Times, Chegg chief executive Dan Rosensweig, when asked whether his company’s services were being used for cheating, said: “Let’s face it: Students have always found a way, whether it’s in fraternities, or whether they go to Google. But Chegg is not built for that.”

The company reported $153 million in revenue for the second quarter , when the pandemic shutdowns were at their peak — a 63 percent year-over-year increase.

Related: Could the online, for-profit college industry be “a winner in this crisis”?

Chegg CFO Andy Brown told investors in a video call, “We’ve clearly been seeing tailwinds since the shelter in place and kids were learning off campus.”

Colleges were not the only institutions to rush examinations online. Advanced placement and other tests also went virtual in the spring and the parent College Board said it was prepared to move the SAT online in the fall if necessary but then reversed itself.* So did law school entrance and placement exams, professional certification tests for financial managers and food handlers and many others.

The College Board , which administers the AP tests, reconfigured these exams to be “open book” when they were moved online, but without proctoring. Students reportedly used private messaging apps to collaborate on answers. Even before the exams began, College Board officials tweeted about “a ring of students who were developing plans to cheat” and canceled their registrations.

The College Board won’t disclose whether any cheating actually happened. A spokesman would say only that “at-home testing presents some different security challenges” and that the organization took steps to prevent it.

There are other reasons besides just having the opportunity that students are cheating online. About a quarter of students “indicated that it should be expected that students will use whatever is available to them in a take-home or online test ,” according to research published in the spring by the Journal of the National College Testing Association. It said “any inaction on the part of the faculty to provide a secure exam administration was seen [by students] as an indication that the faculty did not care about” cheating.

“One student with a pattern of cheating is an ethical problem for that student. Multiple students with a pattern of cheating devalues any grade or degree they might be receiving,” Steve Saladin, a co-author of the study, said. “And when cheating spreads to many students in many programs and schools, degrees and grades cease to provide a measure of an individual’s preparedness for a profession or position. And perhaps even more importantly, it suggests a society that blindly accepts any means to an end as a given.”

*This story has been updated to correct that the SAT was not moved online in the spring.

This story about online testing was produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our higher education newsletter .

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

- Share full article

Accused of Cheating by an Algorithm, and a Professor She Had Never Met

An unsettling glimpse at the digitization of education.

Credit... Ariel Davis

Supported by

By Kashmir Hill

- May 27, 2022

A Florida teenager taking a biology class at a community college got an upsetting note this year. A start-up called Honorlock had flagged her as acting suspiciously during an exam in February. She was, she said in an email to The New York Times, a Black woman who had been “wrongfully accused of academic dishonesty by an algorithm.”

What happened, however, was more complicated than a simple algorithmic mistake. It involved several humans, academic bureaucracy and an automated facial detection tool from Amazon called Rekognition. Despite extensive data collection, including a recording of the girl, 17, and her screen while she took the test, the accusation of cheating was ultimately a human judgment call: Did looking away from the screen mean she was cheating?

The pandemic was a boom time for companies that remotely monitor test takers, as it became a public health hazard to gather a large group in a room. Suddenly, millions of people were forced to take bar exams, tests and quizzes alone at home on their laptops. To prevent the temptation to cheat, and catch those who did, remote proctoring companies offered web browser extensions that detect keystrokes and cursor movements, collect audio from a computer’s microphone, and record the screen and the feed from a computer’s camera, bringing surveillance methods used by law enforcement, employers and domestic abusers into an academic setting.

Honorlock, based in Boca Raton, Fla., was founded by a couple of business school graduates who were frustrated by classmates they believed were gaming tests. The start-up administered nine million exams in 2021, charging about $5 per test or $10 per student to cover all the tests in the course. Honorlock has raised $40 million from investors, the vast majority of it since the pandemic began.

Keeping test takers honest has become a multimillion-dollar industry, but Honorlock and its competitors, including ExamSoft, ProctorU and Proctorio, have faced major blowback along the way: widespread activism , media reports on the technology’s problems and even a Senate inquiry . Some surveilled test takers have been frustrated by the software’s invasiveness , glitches , false allegations of cheating and failure to work equally well for all types of people.

The Florida teenager is a rare example of an accused cheater who received the evidence against her: a 50-second clip from her hourlong Honorlock recording. She asked that her name not be used because of the stigma associated with academic dishonesty.

The teenager was in the final year of a special program to earn both her high school diploma and her associate degree. Nearly 40 other students were in the teenager’s biology class, but they never met. The class, from Broward College, was fully remote and asynchronous.

Asynchronous online education was growing even before the pandemic. It offers students a more flexible schedule, but it has downsides. Last year, an art history student who had a question about a recorded lecture tried to email his professor, and discovered that the man had died nearly two years earlier .

The Florida teenager’s biology professor, Jonelle Orridge, was alive, but distant, her interactions with students taking place by email, as she assigned readings and YouTube videos. The exam this past February was the second the teenager had taken in the class. She set up her laptop in her living room in North Lauderdale making sure to follow a long list of rules set out in the class syllabus and in an Honorlock drop-down menu: Do not eat or drink, use a phone, have others in the room, look offscreen to read notes, and so on.

The student had to pose in front of her laptop camera for a photo, show her student ID, and then pick her laptop up and use its camera to provide a 360-degree scan of the room to prove she didn’t have any contraband material. She didn’t mind any of this, she said, because she hoped the measures would prevent others from cheating.

She thought the test went well, but a few days later, she received an email from Dr. Orridge.

“You were flagged by Honorlock,” Dr. Orridge wrote. “After review of your video, you were observed frequently looking down and away from the screen before answering questions.”

She was receiving a zero on the exam, and the matter was being referred to the dean of student affairs. “If you are found responsible for academic dishonesty the grade of zero will remain,” Dr. Orridge wrote.

“This must be a mistake,” the student replied in an email. “I was not being academically dishonest. Looking down does not indicate academic dishonesty.”

‘The word of God’

The New York Times has reviewed the video. Honorlock recordings of several other students are visible briefly in the screen capture, before the teenager’s video is played.

The student and her screen are visible, as is a partial log of time stamps, including at least one red flag, which is meant to indicate highly suspicious behavior, just a minute into her test. As the student begins the exam, at 8:29 a.m., she scrolls through four questions, appearing to look down after reading each one, once for as long as 10 seconds. She shifts slightly. She does not answer any of the questions during the 50-second clip.

It’s impossible to say with certainty what is happening in the video. What the artificial intelligence technology got right is that she looked down. But to do what? She could be staring at the table, a smartphone or notes. The video is ambiguous.

When the student met with the dean and Dr. Orridge by video, she said, she told them that she looks down to think, and that she fiddles with her hands to jog her memory. They were not swayed. The student was found “responsible” for “noncompliance with directions,” resulting in a zero on the exam and a warning on her record.

“Who stares at a test the entire time they’re taking a test? That’s ridiculous. That’s not how humans work,” said Cooper Quintin, a technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights organization. “Normal behaviors are punished by this software.”

After examining online proctoring software that medical students at Dartmouth College claimed had wrongly flagged them , Mr. Quintin suggested that schools have outside experts review evidence of cheating. The most serious flaw with these systems may be a human one: educators who overreact when artificially intelligent software raises an alert.

“Schools seem to be treating it as the word of God,” Mr. Quintin said. “If the computer says you’re cheating, you must be cheating.”

Tess Mitchell, a spokeswoman for Honorlock, said it was not the company’s role to advise schools on how to deal with behavior flagged by its product.

“In no case do we definitively identify ‘cheaters’ — the final decision and course of action is up to the instructor and school, just as it would be in a classroom setting,” Ms. Mitchell said. “It can be challenging to interpret a student’s actions. That’s why we don’t.”

Dr. Orridge did not respond to requests for comment for this article. A spokeswoman from Broward College said she could not discuss the case because of student privacy laws. In an email, she said faculty “exercise their best judgment” about what they see in Honorlock reports. She said a first warning for dishonesty would appear on a student’s record but not have more serious consequences, such as preventing the student from graduating or transferring credits to another institution.

Who decides

Honorlock hasn’t previously disclosed exactly how its artificial intelligence works, but a company spokeswoman revealed that the company performs face detection using Rekognition, an image analysis tool that Amazon started selling in 2016. The Rekognition software looks for facial landmarks — nose, eyes, eyebrows, mouth — and returns a confidence score that what is onscreen is a face. It can also infer the emotional state, gender and angle of the face.

Honorlock will flag a test taker as suspicious if it detects multiple faces in the room, or if the test taker’s face disappears, which could happen when people cover their face with their hands in frustration, said Brandon Smith, Honorlock’s president and chief operating officer.

Honorlock does sometimes use human employees to monitor test takers; “live proctors” will pop in by chat if there is a high number of flags on an exam to find out what is going on. Recently, these proctors discovered that Rekognition was mistakenly registering faces in photos or posters as additional people in the room.

When something like that happens, Honorlock tells Amazon’s engineers. “They take our real data and use it to improve their A.I.,” Mr. Smith said.

Rekognition was supposed to be a step up from what Honorlock had been using. A previous face detection tool from Google was worse at detecting the faces of people with a range of skin tones, Mr. Smith said.

But Rekognition has also been accused of bias. In a series of studies, Joy Buolamwini, a computer researcher and executive director of the Algorithmic Justice League, found that gender classification software, including Rekognition , worked least well on darker-skinned females.

Determining a person’s gender is different from detecting or recognizing a face, but Dr. Buolamwini considered her findings a canary in a coal mine. “If you sell one system that has been shown to have bias on human faces, it is doubtful your other face-based products are also completely bias free,” she wrote in 2019.

The Times analyzed images from the student’s Honorlock video with Amazon Rekognition. It was 99.9 percent confident that a face was present and that it was sad, and 59 percent confident that the student was a man.

Dr. Buolamwini said the Florida student’s skin color and gender should be a consideration in her attempts to clear her name, regardless of whether they affected the algorithm’s performance.

“Whether it is technically linked to race or gender, the stigma and presumption placed on students of color can be exacerbated when a machine label feeds into confirmation bias,” Dr. Buolamwini wrote in an email.

The human element

As the pandemic winds down, and test takers can gather in person again, the remote proctoring industry may soon be in lower demand and face far less scrutiny. However, the intense activism around the technology during the pandemic did lead at least one company to make a major change to its product.

ProctorU, an Honorlock competitor, no longer offers an A.I.-only product that flags videos for professors to review.

“The faculty didn’t have the time, training or ability to do it or do it properly,” said Jarrod Morgan, ProctorU’s founder. A review of ProctorU’s internal data found that videos of flagged behavior were opened only 11 percent of the time.

All suspicious behavior is now reviewed by one of the company’s approximately 1,300 proctors, most of whom are based abroad in cheaper labor markets. Mr. Morgan said these contractors went through rigorous training, and would “confirm a breach” only if there was solid evidence that a test taker was receiving help. ProctorU administered four million exams last year; in analyzing three million of those tests, it found that over 200,000, or about 7 percent, involved some kind of academic misconduct, according to the company.

The teenager graduated from Broward College this month. She remains distraught at being labeled a cheater and fears it could happen again.

“I try to become like a mannequin during tests now,” she said.

Kashmir Hill is a tech reporter based in New York. She writes about the unexpected and sometimes ominous ways technology is changing our lives, particularly when it comes to our privacy. More about Kashmir Hill

Advertisement

Study: 1 in 3 students use cellphones to cheat on exams

Itty-bitty hidden scraps of paper. Blurry ink on hands. That's old-school cheating.

Today, teens cheat with electronic devices.

One in three kids in the U.S. use cellphones or other devices to cheat. That's what McAfee, an online security software maker, found in a newly released survey. Plus, about six in 10 teens have seen or know another teen who used a connected device in class to cheat on an exam or quiz.

McAfee conducted an online survey of 1,201 U.S. high school students in Grades 9-12 in June. (Read more about the expanded study of teens' use of technology in classrooms in Australia, the U.K. and Canada here .)

More sneaky ways

Teens also have figured out how to get around school electronic security restrictions with 31 percent of teens accessing banned content in classrooms.

More than half of the students were able to access any (29 percent) or some (25 percent) of the social-media sites on school-owned connected devices.

Cyberbullied before high school

About one in three teens have reported being cyberbullied, with more than half saying it happened before ninth grade.

The survey found:

- 30 percent of students said they were cyberbullied.

- 51 percent said it happened before ninth grade.

- Girls are cyberbullied 30 percent more than boys.

- Social networks used the most for cyberbullying: Facebook (71 percent), Instagram (62 percent) and Snapchat (49 percent).

Like All the Moms?

Follow us on Facebook.

More teen news

Academic Dishonesty Statistics

Definition Of Academic Cheating

- Cheating refers to using various types of materials, information, or devices that are not allowed when completing an academic task. It can include communicating with other test-takers without the consent of the proctor, using a phone to search for information on the Internet, etc.

- Plagiarism implies using the works of other people (their ideas, words, designs, etc.) without their consent. One of the most common forms of plagiarism is copying text written by one or more other authors and pasting it into your paperwork without citation.

- Fabrication involves using data that doesn't exist. For example, having failed to find evidence for their theories, some students opt for counterfeiting the necessary information.

Why Do Students Prefer to Cheat?

- Lack of time or poor time management

- Fear of failure

- Anxiety about grades

- Desire to help classmates

- Academic overload

- Stress, etc.

What’s more, some students not only cheat, but also find it acceptable in particular situations. Eric M. Anderman, a professor from Ohio State University, published a survey in 2017 stating that the majority of the 400 respondents admitted that it’s not a big deal to cheat if you are not interested in a subject. This perspective was also considered in research from Lindale High School (LHS). According to the results, 44.4% of students consider it ethical to behave dishonestly while doing homework, but not during a test.

Could Cheating Hinge on Student Culture?

What’s more, East European countries, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, and former Soviet Union countries tend to be less strict and more accepting of academic cheating than Western European countries and the US. According to a survey carried out by CEDOS together with American Councils for International Education, American and European universities often have different or even opposite opinions about academic misconduct.

Academic Cheating Fact Sheet

The cheating rate among high school and college students is tremendously high, and it isn’t losing momentum. There is an avalanche of cheating incidents happening worldwide. Students who have been lured by cheating once usually tend to continue shortcutting. Unsurprisingly, the statistics are supported by ample evidence. Here are some jaw-dropping facts about cheating in school and college:

60.8% of polled college students admitted to cheating

According to a survey conducted by the CollegeHumor website among 30,000 respondents, 60.8% of college students admitted to committing some form of cheating. Moreover, 16.5% of them didn’t feel guilty about it. This data was supported by the results of Rutgers University research showing that 68% of the polled students acted dishonestly during their studies.

Cheaters have higher GPAs

Many students opt for cheating to get good grades. Although it may be upsetting for their honest counterparts, cheaters manage to achieve their goals. Statistics provided by Fordham University show that dishonest students have a Grade Point Average (GPA) of about 3.41, while non-cheaters can boast of only 2.85. It’s important to understand that these numbers not only indicate the decreasing amount of opportunities for honest students, but also may push more of them to commit the same unethical acts.

95% of cheaters don't get caught

Research carried out by ETS and the Ad Council indicates that the majority of cheaters stay unnoticed and don’t get caught for their misconduct. This is another motive for other students to break the established rules of academic integrity. According to U.S. News and World Report, 90% of polled college students are sure that they will not be caught cheating.

Dishonesty among college students stems from high school

According to ETS and Ad Council research, 75% to 98% of students who admitted to cheating at college confessed to have started doing it in high school. Moreover, academic dishonesty is showing up among even younger students, meaning that it is starting to take place not only in high school, but also in elementary school.

There is no gender difference in cheating

The Ad Council and ETS survey states that there is no significant gender difference in academic misconduct. However, men tend to confess to it slightly more than women. When it comes to subjects, disciplines like math and science are more prone to cheating incidents.

Cheating is getting worse

According to research from the Josephson Institute Center for Youth Ethics, the number of cheating students is not only high, but also shows an uptrend potential. The study provided statistics from two academic years. In the first year, it revealed 59% of cheating high-school students, but in the next year, the number surged to 95%.

Renowned Colleges Turn Out to Be Vulnerable Too

Despite the common belief that renowned educational institutions have managed to eliminate cheating, statistics and news headlines provide a different view. According to McCabe research, reputable colleges and universities have significantly reduced the level of academic misconduct due to stricter honor codes and a more developed academic culture, but they haven’t managed to eradicate it. Even world-famous elite institutions are found to be involved in cheating scandals.

In 2012, Harvard University was involved in one of the biggest cheating scandals in its history. About 125 of its students were suspected of working in collaboration on an exam despite being asked to do it alone. As a result, around 70 students were forced out.

Strategies for Reducing Cheating

- Avoid student overload. When placed under continuous pressure, students often fail to manage their time and start looking for easier ways to get a good grade.

- Be thoughtful about language . It’s important to choose the right words for praising your students. It’s recommended to use phrases that include both praising and stimulus for further progress. For example, “You did a great job but there are still more areas you can develop in.”

- Develop academic culture . Educational institutions are advised to devote more time to discussing ethical matters with their students. Moreover, they could consider including these types of lessons in their curriculum.

- Proctoring . The increasing popularity of e-learning and continuous technological development has fostered a surge in academic misconduct. However, why not turn the tide in your favor? Nowadays, there are many innovative digital proctoring solutions, such as ProctorEdu.com, that help educational institutions increase the effectiveness of online learning and protect their reputation.

What is the percentage of students cheating?

How often do students get caught cheating, is academic cheating getting worse, what percentage of high schoolers have cheated.

- Auto proctoring

- Live proctoring

- AI Proctoring

- Exam Monitoring Software

- For Higher education

- Corporate Certification

- Professional Certification

- Olympiad Exams

- Language Certification

- Test Platforms

- Online Proctoring Software for Pre-Employment Testing

- HR-training

- Case studies

- YouTestMe Partner

- Our Partners

- Documentation

- For students

- Computer check

- Terms of service

- Accessibility statement

- Privacy policy

- Regulations for technical support

- General data protection regulation

share this!

August 19, 2019

Students are still using tech to cheat on exams, but things are getting more advanced

by Dalvin Brown, Usa Today

In many ways, cheating on high school and college exams used to be a lot harder than it is nowadays.

What used to take an elaborate plot to discreetly spread answers across a classroom can now be done with a swipe on a smartwatch. You used to have to steal the answer key or have a cheat sheet hidden around your desk.

Now, smartphones can be disguised as calculators, information can be spread invisibly via the airwaves and tiny earbuds allow students to listen to content transmitted from a smartphone in their backpack across the room.

The self-identified student cheaters we reached out to wouldn't go on the record to discuss these behaviors (for obvious reasons). However, Twitter is a hotbed for discussion on the topic and smartwatches are a fan favorite as a convenient loophole to classroom smartphone bans.

"An Apple Watch is the go-to way to cheat on any exam. Hands down," Tweets @too_Coziey in December 2018. "I bought an Apple Watch just to cheat on exams in ( high school )," writes @Shymyafaith.

"My teacher collects phones during exams so I brought two phones and an Apple Watch. I will cheat on my exam, (i don't care) if it kills me," writes Twitter user @Wontonpx.

There are even online instructional videos and countless digital forums that teach students how to cheat on tests using their gadgets.

Technology enthusiasts often tout the latest innovations as tools to help students feel more engaged in the classroom. They encourage teachers and schools to adapt to the shifting tech landscape and instructors and institutions often follow suit, introducing Echo Dots and smartwatches to campuses in recent years.

While the gadgets have utility in educational environments, they also open pandora's box, allowing students to pay less attention in class and shortcut their education—aka cheat.

"Technology presents new ways for students to do things that they've always been doing which is avoid doing the work themselves," said David Rettinger, president of International Center for Academic Integrity and instructor of psychological sciences at the University of Mary Washington.

"Forever, students would go to a book and copy things for a paper. Copy and paste plagiarism is as old as reading and writing, but now it's so much easier. You don't even have to leave your desk to do that. The bar has gotten much lower."

In other words, cheating is nothing new, and students have been taking notes on their devices, getting notifications during tests, texting their friends for answers and sending photos of exams to their classmates for years.

However, one of the latest, widespread forms of cheating in the classroom involves students using auto-summarize features in programs like Word to pass off computer-generated essays as original work.

Summarizing tools can also be found on the internet. They take the most important information from a large text and generate a shorter version that isn't easily picked up by anti-plagiarism software, according to Teddi Fishman, the former director of the International Center for Academic Integrity.

She works with educators, students and administrators to identify integrity vulnerabilities and taught at the State University of West Georgia and Clemson University.

What makes today's cheating landscape even more dire is that "teachers are so overworked" Fishman said. "A lot of them are not tenured so they may be working at two or three universities to make ends meet. They just don't have time" to double-check if they suspect a student of cheating.

Along with the auto-summarizing tools, technology now enables students to buy "bespoke essays" from third parties overseas. These so-called "essay mills" don't just let students buy one assignment. They're contracting someone to write all their assignments for a semester or even a year.

If it's an online class, "You can pay somebody in another country to take that course for you. If you do an easy online search for 'take my online class," you see sites where someone can log in, take the class and you can get the credit for it," Fishman said.

"That's a danger for all of us. Imagine if your nurse paid someone to take classes for them."

The Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 requires institutions to verify the identities of remote students by using at least one of the following methods: a secure login and password, proctored exams or other technological practices to accurately identify a person.

In many cases, the use of a secure User ID and password that can be easily exchanged with others and proctored exams are effective only if the instructor actually knows what the student looks like. However, tech such as typing-style verification and speed checks may help to curb cheating in e-learning situations.

Rettinger, who is also an associate professor of psychological science, has started giving his classes shorter exams, which cuts down on the time students could spend trying to figure out how to cheat.

"I've changed a lot of my assessment to be much shorter, lower-stake assessment rather than big exams. (So) students feel less pressure to cheat," Rettinger said.

"When you have a test and it's worth a lot of points, a student is going to put a lot of work into either studying or cheating," he said. "If it's a quick test, there isn't as much time to set up those structures. You're not dumbing down the material. I'm just testing more frequently."

The University of Mary Washington and many others use a student-run honor codes to discourage cheating where the student body self-polices to create a social sanction against being dishonest.

Teachers also use tools like the plagiarism-checking software Turnitin to sniff out academic dishonesty. In March 2019, Turnitin released a piece of software called Authorship Investigate, which creates a digital fingerprint of a writer's writing style so teachers can detect changes over the course of the semester to detect "contract cheating."

Alexis Redding, a lecturer in the Higher Education Program at Harvard who studied cheating, warns that if instructors don't go through those types of plagiarism reports with students, they "become confused about what they're doing right and what they're doing wrong."

Some institutions and departments across the country mandate that students submit all essays through plagiarism detection programs. "That feels like a very dangerous direction to go in," Redding said. "It sends a negative message to students that we are expecting them to do something for which we need to catch them."

Still, advances in technology will continue to make information sharing easier and more discreet. With teens and young adults being digital natives and early adopters of innovative communications, experts say teachers will always be slower to catch up.

"By the time you try to figure out how to outsmart the people who want to cheat, you've already lost the battle," said Howard Gardner, a research professor of cognition and education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Instead of getting into a technological arm's race with students, Gardner said instructors and parents should help students understand "why one shouldn't cheat and why it's destructive to them. It's easy to say that and be completely ignored, but otherwise, it's a (game of) cops and robbers."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Solar storm puts on brilliant light show across the globe, but no serious problems reported

11 hours ago

Study discovers cellular activity that hints recycling is in our DNA

12 hours ago

Weaker ocean currents lead to decline in nutrients for North Atlantic ocean life during prehistoric climate change

Research explores ways to mitigate the environmental toxicity of ubiquitous silver nanoparticles

AI may be to blame for our failure to make contact with alien civilizations

15 hours ago

Saturday Citations: Dietary habits of humans; dietary habits of supermassive black holes; saving endangered bilbies

18 hours ago

Scientists unlock key to breeding 'carbon gobbling' plants with a major appetite

May 10, 2024

Clues from deep magma reservoirs could improve volcanic eruption forecasts

Study shows AI conversational agents can help reduce interethnic prejudice during online interactions

NASA's Chandra notices the galactic center is venting

Relevant physicsforums posts, plagiarism & chatgpt: is cheating with ai the new normal.

3 hours ago

Physics Instructor Minimum Education to Teach Community College

6 hours ago

Studying "Useful" vs. "Useless" Stuff in School

Apr 30, 2024

Why are Physicists so informal with mathematics?

Apr 29, 2024

Digital oscilloscope for high school use

Apr 25, 2024

Motivating high school Physics students with Popcorn Physics

Apr 3, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Don't assume online students are more likely to cheat. The evidence is murky

Jul 27, 2018

How disliked classes affect college student cheating

Oct 4, 2017

Doing away with essays won't necessarily stop students cheating

Dec 20, 2018

High achievers in competitive courses more likely to cheat on college exams

Aug 25, 2017

Professors need to be entertaining to prevent students from watching YouTube in class

Jun 26, 2019

US teens use smart phones for cheating: study

Jun 19, 2009

Recommended for you

Investigation reveals varied impact of preschool programs on long-term school success

May 2, 2024

Training of brain processes makes reading more efficient

Apr 18, 2024

Researchers find lower grades given to students with surnames that come later in alphabetical order

Apr 17, 2024

Earth, the sun and a bike wheel: Why your high-school textbook was wrong about the shape of Earth's orbit

Apr 8, 2024

Touchibo, a robot that fosters inclusion in education through touch

Apr 5, 2024

More than money, family and community bonds prep teens for college success: Study

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

What do ai chatbots really mean for students and cheating.

The launch of ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots has triggered an alarm for many educators, who worry about students using the technology to cheat by passing its writing off as their own. But two Stanford researchers say that concern is misdirected, based on their ongoing research into cheating among U.S. high school students before and after the release of ChatGPT.

“There’s been a ton of media coverage about AI making it easier and more likely for students to cheat,” said Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE). “But we haven’t seen that bear out in our data so far. And we know from our research that when students do cheat, it’s typically for reasons that have very little to do with their access to technology.”

Pope is a co-founder of Challenge Success , a school reform nonprofit affiliated with the GSE, which conducts research into the student experience, including students’ well-being and sense of belonging, academic integrity, and their engagement with learning. She is the author of Doing School: How We Are Creating a Generation of Stressed-Out, Materialistic, and Miseducated Students , and coauthor of Overloaded and Underprepared: Strategies for Stronger Schools and Healthy, Successful Kids.

Victor Lee is an associate professor at the GSE whose focus includes researching and designing learning experiences for K-12 data science education and AI literacy. He is the faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning and director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), a program that provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students.

Here, Lee and Pope discuss the state of cheating in U.S. schools, what research shows about why students cheat, and their recommendations for educators working to address the problem.

Denise Pope

What do we know about how much students cheat?

Pope: We know that cheating rates have been high for a long time. At Challenge Success we’ve been running surveys and focus groups at schools for over 15 years, asking students about different aspects of their lives — the amount of sleep they get, homework pressure, extracurricular activities, family expectations, things like that — and also several questions about different forms of cheating.

For years, long before ChatGPT hit the scene, some 60 to 70 percent of students have reported engaging in at least one “cheating” behavior during the previous month. That percentage has stayed about the same or even decreased slightly in our 2023 surveys, when we added questions specific to new AI technologies, like ChatGPT, and how students are using it for school assignments.

Isn’t it possible that they’re lying about cheating?

Pope: Because these surveys are anonymous, students are surprisingly honest — especially when they know we’re doing these surveys to help improve their school experience. We often follow up our surveys with focus groups where the students tell us that those numbers seem accurate. If anything, they’re underreporting the frequency of these behaviors.

Lee: The surveys are also carefully written so they don’t ask, point-blank, “Do you cheat?” They ask about specific actions that are classified as cheating, like whether they have copied material word for word for an assignment in the past month or knowingly looked at someone else’s answer during a test. With AI, most of the fear is that the chatbot will write the paper for the student. But there isn’t evidence of an increase in that.

So AI isn’t changing how often students cheat — just the tools that they’re using?

Lee: The most prudent thing to say right now is that the data suggest, perhaps to the surprise of many people, that AI is not increasing the frequency of cheating. This may change as students become increasingly familiar with the technology, and we’ll continue to study it and see if and how this changes.

But I think it’s important to point out that, in Challenge Success’ most recent survey, students were also asked if and how they felt an AI chatbot like ChatGPT should be allowed for school-related tasks. Many said they thought it should be acceptable for “starter” purposes, like explaining a new concept or generating ideas for a paper. But the vast majority said that using a chatbot to write an entire paper should never be allowed. So this idea that students who’ve never cheated before are going to suddenly run amok and have AI write all of their papers appears unfounded.

But clearly a lot of students are cheating in the first place. Isn’t that a problem?

Pope: There are so many reasons why students cheat. They might be struggling with the material and unable to get the help they need. Maybe they have too much homework and not enough time to do it. Or maybe assignments feel like pointless busywork. Many students tell us they’re overwhelmed by the pressure to achieve — they know cheating is wrong, but they don’t want to let their family down by bringing home a low grade.

We know from our research that cheating is generally a symptom of a deeper, systemic problem. When students feel respected and valued, they’re more likely to engage in learning and act with integrity. They’re less likely to cheat when they feel a sense of belonging and connection at school, and when they find purpose and meaning in their classes. Strategies to help students feel more engaged and valued are likely to be more effective than taking a hard line on AI, especially since we know AI is here to stay and can actually be a great tool to promote deeper engagement with learning.

What would you suggest to school leaders who are concerned about students using AI chatbots?

Pope: Even before ChatGPT, we could never be sure whether kids were getting help from a parent or tutor or another source on their assignments, and this was not considered cheating. Kids in our focus groups are wondering why they can't use ChatGPT as another resource to help them write their papers — not to write the whole thing word for word, but to get the kind of help a parent or tutor would offer. We need to help students and educators find ways to discuss the ethics of using this technology and when it is and isn't useful for student learning.

Lee: There’s a lot of fear about students using this technology. Schools have considered putting significant amounts of money in AI-detection software, which studies show can be highly unreliable. Some districts have tried blocking AI chatbots from school wifi and devices, then repealed those bans because they were ineffective.