I’solezwe lesiXhosa

I'solezwe lesiXhosa

- OUR BRANDS /

- NEWSPAPERS /

- I’solezwe lesiXhosa /

I’solezwe lesiXhosa is South Africa’s first daily Xhosa newspaper run from Independent Media’s East London office. From Monday to Friday this innovative vernacular title delivers content that speaks to a predominantly Eastern Cape readers and is filled with news, sports, opinions as as daily themed pages. Mondays the paper carries business themed pages, Tuesdays health and lifestyle, Wednesdays is small business and enterprise development, Thursdays are devoted to education and Fridays are our traditional and cultural themed pages.

- Entsimini (English)

- Entsimini PDF

- Iikopi ze-elektroniki

- Funda Ngathi – About Us

- Nxulumana Nathi – Contact Us

- Funda Ngathi – About Us

I’solezwe lesiXhosa

The Eye of the Nation – that sees across the river.

I’solezwe lesiXhosa was first launched on the 30 of March 2015 as South Africa’s first ever daily Xhosa newspaper. The newspaper now operates successfully as a weekly – published every Thursday – in the Eastern Cape and Western Cape provinces.

I’solezwe lesiXhosa nurtures and fosters pride within the wider Xhosa community – a community that is proud of its traditions, its heritage and culture. The newspaper seeks to be truthful, accurate, objective and foster the aspirations of the amaXhosa people, both culturally and commercially.

Continuous coverage is given to national and regional news, regional business, lifestyle, entertainment, sport and social.

Physiographically, our readership is typified by individuals who are;

- Intensely proud of the Xhosa heritage.

- Wish to be informed about the happenings in their community – both the serious and light hearted.

- They wish to be informed about the outside world – but are irritated by unending flow of political rhetoric.

- Their life-needs are identical to all South Africans – shelter, food, health, basic services and an improving life style.

- Metropolitan residents are more closely focused on visible material assets than their rural counterparts.

Distribution (33 000 as of 1 August 2016) Distribution of I’solezwe lesiXosa is across the Eastern Cape Province with an up weighted focus on the key economically active regions of Mthatha, East London, King Williamstown and Port Elizabeth.

Advertising: Research records that:

- There are 3.5 million literate Xhosas, aged 15 years and plus, and falling into LSM 4 – 9 segments that are resident in the Eastern Cape.

- It is also noteworthy that a further 1.2 million are resident in the Western Cape and 500 000 in Gauteng.

- While the population is widely dispersed – both urban and rural – upwards of 66% claim to be resident in the metropolitan complexes of Port Elizabeth, East London and Mthatha.

- Expected readership will be male biased – 55:45.

To advertise in the I’solezwe lesiXhosa please contact our sales executives: Nwabisa Nompunga 043 721 2237 | Cell: 078 951 1227 | [email protected] Miso Jikijela 043 721 3465 | Cell: 082 702 8143 | [email protected]

Classified Advertising: Tel: 021 488 4598 | E-mail: [email protected] General Enquires: Tel: 021 488 4133 | E-mail: [email protected]

The I’solezwe lesiXhosa is an Africa Community Media (ACM) title. ACM also publishes: Athlone News | Atlantic Sun | Bolander | CapeTowner | False Bay Echo | Plainsman | Sentinel News | Southern Mail | Southern Suburbs Tatler | Tabletalk | Northern News Goodwood/Parow | Northern News Bellville/Durbanville | Northern News Kuilsriver/Brackenfell/Kraaifontein | The Pink Tongue | DFA | I’solezwe lesiXhosa | KZN Shoppers

Popular News

USinoxolo Kwayiba ubulela uMpengesi nabaqeqeshi abamnike ithuba!

UZizi Kodwa ufuna uRhulumente atyale imali eninzi kweZemidlalo

UVictor Gomes uthi iSafa nePSL zilungiselela ukufika kweVAR!

Waqaqamba uDumke ombhoxweni iSpringbok sathatha indebe eMadagasca!

Isindile ezembeni iSwallows konwaba uMusa Nyatama!

- Nxulumana Nathi – Contact Us

- Ezabucala – Privacy Policy

- Imiqathango Nezeluleko – Terms and Conditions

Iliso Labantu News

root - November 20, 2022

Ukusebenza nzima kukaBulelani Mvunyiswas nokuthanda umculo kumzisele indlela entle Ophuma kwityotyombe elingasemva kwendlu kwizitalato ezixineneyo zaseDunoon,oyimvumi yegospile ethe yaba luphawu lwethemba kunye nenkuthazo. Ngomculo wokhole,...

From village, to township, to gospel stardom

Bulelani Mvunyiswa’s hard work and passion for music have brought him a long way Peter Luhanga Emerging from a backyard shack off the crowded streets...

Ummeli omtsha waseDunoon obhengezwe yiANC emva kokugxotha uceba wale wadi

ISanco iyabuxhasa ubunkokheli bethutyana de kubanjwe unyulo Peter Luhanga Ukugxothwa kukaceba wakwa ward 104 eDunoons uMessie Makuwa yiANC kubangele ukuba uceba weANC uLazola Gungxe angeniswe...

New Dunoon representative announced by ANC after ousting ward councillor

Sanco supports interim leadership until by-elections are held Peter Luhanga The recall of Dunoon’s ward 104 councillor Messie Makuwa by the ANC has resulted in proportional...

Nine years later, here is how Wolwerivier is doing

Residents of the City’s emergency housing development face unemployment, extreme heat, and overcrowding. But “we have achieved a lot” says a community member Liezl Human Life...

Dunoon’s Killarney Garden housing project grinds to a halt, thwarting hopes for almost 500 families

Completion date uncertain for 488 planned units Peter Luhanga Cape Town — A housing initiative intended to alleviate the strain on overcrowded Cape Town...

Abafundi bematriki baseDunoon bagqwesile

UMakanaka Muzuva ugqame njengophumeleleyo uphezulu phakathi kwabafundi abahlanu abaphezulu bematriki ngo-2023 eSinenjongo High School, eJoe Slovo Park, eMilnerton. Ifoto: Peter Luhanga Bamenzile umahluko ngaphandle kwemicelimngeni...

Dunoon matrics rake in distinctions despite major challenges

Poverty, noise, loadshedding and crowded living conditions didn’t stop these learners reaching their academic dreams Peter Luhanga Despite the challenge of living with her two...

Uceba waseDunoon ugxothwe yiANC ngequbuliso

Uceba uMessie Makuwa uvile ngokukhutshwa kwakhe kwimizuzu nje embalwa phambi kwebhunga lebhunga leSixeko saseKapa UMakuwa uthi ukulungele ukulwa nokubizwa kwakhe enkundleni. Peter Luhanga Kwimeko eyothusayo,...

Xhosa language newspapers

This article focuses on the history of 19th century Xhosa language newspapers in South Africa.

Introduction

List of 19th and 20th century xhosa newspapers, umshumayeli wendaba, isitunywa senyanga, isigidimi samaxhosa, izwi labantu, imvo zabantsundu, inkundla ya bantu.

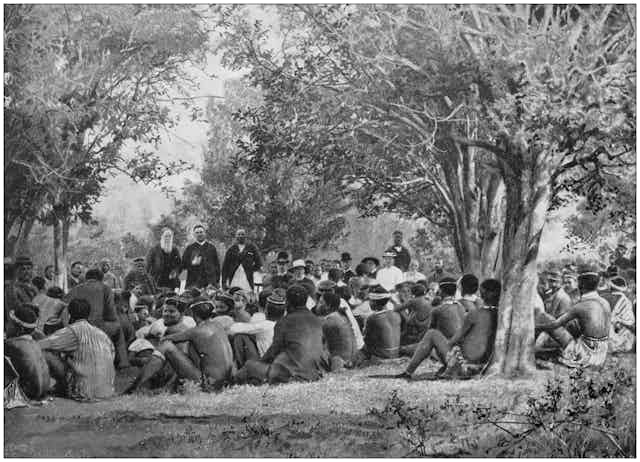

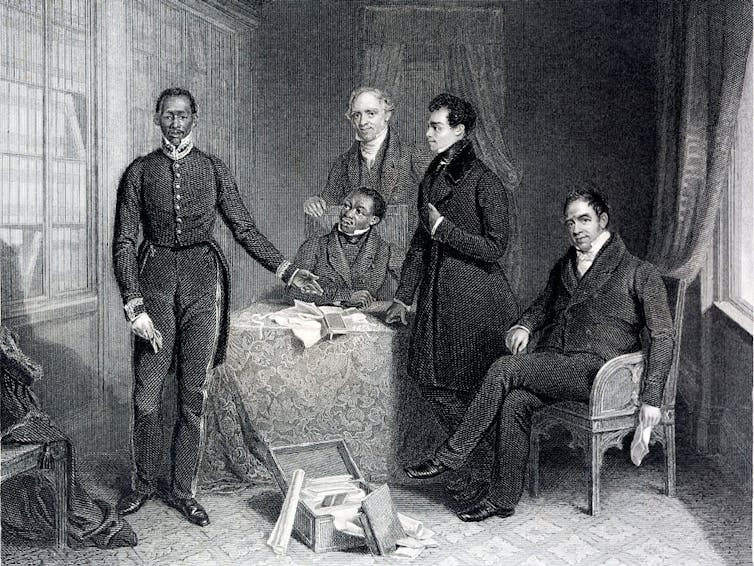

The first Nguni language newspapers in South Africa were founded in the Eastern Cape during the 19th century. The efforts of the Glasgow Missionary Society and the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society were largely responsible for the beginnings of Xhosa language publishing. Christian missionaries were responsible for the beginning of the movement towards vernacular language publishing in South Africa: the first piece of Xhosa writing was a hymn written in the early 19th century by the prophet Ntsikana. The Bible was translated into Xhosa between the 1820s and 1859. [1]

The earliest known black newspaper in Southern Africa was founded by the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society in Grahamstown , Eastern Cape. The first 10 issues (1837–39) were published in Grahamstown and the last five issues (1840–41) at Peddie . The first and fifth issues of the publication were 10 pages, and the other 13 issues were eight pages. [2]

Founded by the Glasgow Missionary Society and published in association with the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society at Chumie mission station (Chumie Press) near Lovedale in the Eastern Cape. "The items included a story of Ntsikana (the Xhosa prophet), an article on circumcision among the Xhosa , a story of George Washington ...accounts of Christian work in lands beyond Africa, stories of African converts to Christianity and an appeal to Christian parents about the training of their children" (Ngcongco). According to Mahlasela, this magazine contained the earliest known writings in Xhosa by a Xhosa writer. William Kobe Ntsikana (son of the prophet), Zaze Soga, and Makhaphela Noyi Balfour were among those who wrote for the journal. [2]

A newspaper for the "literary and religious advancement of the Xhosa" (September 1850), it was edited by J. W. Appleyard of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society. The newspaper was published at Mount Coke (Wesleyan Mission Press), near King William's Town , Cape. It averaged four pages with editorials and news stories in English. [2]

Founded and published by the Glasgow Missionary Society for African teachers and students at Lovedale, near Alice , Cape. The newspaper was written mostly by Africans from Lovedale, among whom was Tiyo Soga , who wrote under the pseudonym "Nonjiba Waseluhlangeni" (Dove of the Nation). One-third of the newspaper was in English for the "intellectual advancement" of the students. [2]

October 1870 – December 1875 (as part of The Kaffir Express ); January 1876 – December 1888 (as an independent newspaper) monthly, fortnightly (1883–84). After the demise of the first newspapers, European missionaries founded Isigidimi Sama-Xosa (The Xhosa Messenger), which appeared between October 1870 and December 1888. James Stewart, principal of Lovedale and publisher of Lovedale Mission Press, was the founding editor and he later handed the editorial position over to Tiyo Soga's students (Makiwane, Bokwe, Jabavu and Gqoba). [With the death of William Wellington Gqoba in 1888, Isigdimi Sama –Xosa newspaper collapses.] ---> Discontent with the intervention of the missionaries concerning the content of Isigidimi samaXhosa , John Tengo Jabavu founded Imvo Zabantsundu newspaper. [2]

Founded and published in East London by a group of Africans opposed to John Tengo Jabavu 's support of the Afrikaner Bond in the election of 1898 in the Cape Colony —the one area in Southern Africa before 1910 where a significant number of Africans (and Coloureds ) actually had voting rights . Nathaniel Cyril Umhalla (or Mhala), R. R. Mantsayi, Thomas Mqanda, George W. Tyamzashe, W. D. Soga, A. H. Maci and F. Jonas, with financial backing from Cecil John Rhodes , launched the news- paper which supported the English-speaking Progressive Party . Umhalla, assisted by Tyamzashe, was the first editor followed by Allan Kirkland Soga, a son of Tiyo Soga , the pioneer missionary, hymnist and writer. Samuel E. K. Mqhayi was the sub- editor (1897–1900, 1906–09) and a writer for the newspaper under the pseudonym of "Imbongi Yakwo Gompo" (The Gompo Poet). Izwi Labantu ' s most important political writer was undoubtedly Walter Rubusana , a founder-member of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in 1912 (it was renamed the African National Congress in 1919) and the political foe of Jabavu. As Trapido put it, Izwi Labantu broke Imvo Zabantsundu' s "monopoly of news and propaganda" and thus enhanced the Black Press's role as "a forum for those who wanted to co-ordinate African political activity." Izwi Labantu actively supported the Native Press Association and was used effectively in the founding of the South African Native Congress (1902), a Cape regional forerunner of the SANNC. [2] [3] [4] [5] Davenport 1966, Scott 1976, Reed personal communication.

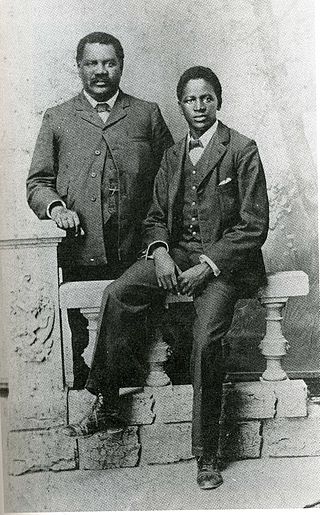

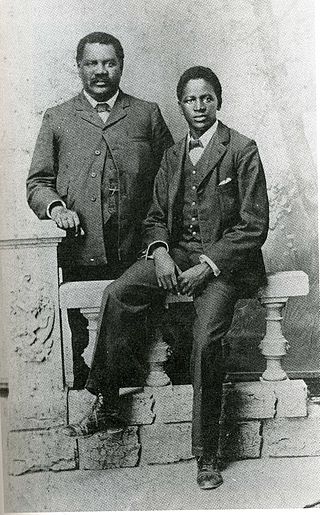

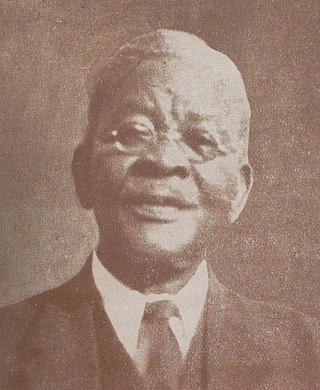

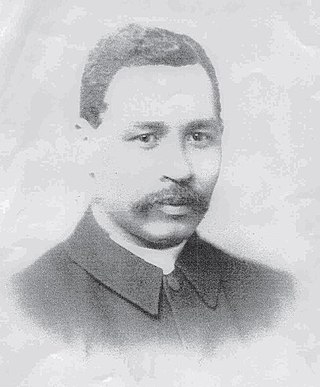

Founded in King William's Town in the Eastern Cape by John Tengo Jabavu with white financial support—chiefly from Richard W. Rose-Innes, King William's Town lawyer and the brother of James Rose-Innes , [6] and James W. Weir, a local merchant and son of a Lovedale missionary. Like John Dube , Jabavu —an influential figure in "white" and "black" politics for more than 40 years—accepted the principle of non-violence and the necessity of working together with "liberal" whites in trying to reform a white-dominated, multi-racial society. The Jabavu family controlled the newspaper until 1935—although from time to time it was edited by others, including John Knox Bokwe (a partner in the company 1898–1900), Solomon Plaatje (July–November 1911), and Samuel E. K. Mqhayi (1920–21). Jabavu's sons, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu and Alexander Macaulay Jabavu (1889–1946), [7] inherited the newspaper when their father died in 1921. Alexander edited the journal until 1940, but it was sold eventually to Bantu Press. The newspaper was moved to Johannesburg until 1953 and then transferred to East London. In 1956 it was moved back to Johannesburg. B. Nyoka edited the newspaper for most of the period it was controlled by Bantu Press, although he was supervised, in turn, by a white editorial director. King William's Town Printing Company, owned by F. Ginsberg, operated the newspaper in partnership with Bantu Press in King William's Town in 1957 and then published the newspaper independently until 1963, when it was sold to Tanda Pers – then a subsidiary of Afrikaanse Pers – and, later, Perskor. Thus Imvo Zabantsundu – the oldest, continuous newspaper founded by an African in South Africa – now promoted the ideology of apartheid . Tiyo Soga 's students later founded Imvo Zabantsundu (African Opinion, November 1884– ) [2]

Inkundla Ya Bantu was first published in April 1938 under the name Territorial Magazine . It was subsequently renamed in June 1940. Its distribution area covered at first the rural parts of the Eastern Cape and Southern Parts of KwaZulu-Natal and then later expanded to the Johannesburg and Witwatersrand area. The newspaper was released monthly at first and then in 1943 became a fortnightly publication and for a while it published weekly but in the last two years of its existence it only managed to publish monthly and some months not at all. [8] Inkundla Ya Bantu was the only independent, 100% black-owned newspaper at the time of its inception and for the duration of its lifespan, that played a significant role in African politics. It published articles in both English and Xhosa.

Intsimbi. An IsiXhosa published in and around Umtata in the 1940s

- ↑ "African – literature: Literatures in African languages", Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Donna Switzer 1979 , p. 275.

- ↑ Karis, Thomas; Carter, Gwendolen Margaret (1972), From Protest to Challenge: Protest and hope, 1882-1934 , vol. 1, Stanford, Calif: Hoover Institution Press

- ↑ Ngcongco, LD (1974). Imvo Zabantsundu and Cape native policy, 1884-1902 (MA). University of South Africa . hdl : 20.500.11892/140398 .

- ↑ "James Rose Innes" . Olive Schreiner Letters Online . 2012 . Retrieved 6 September 2018 .

- ↑ "Alexander Macaulay Jabavu", South African History Online.

- ↑ Ukpanah, Ime John (2005). The Long Road to Freedom: Inkundla Ya Bantu (Bantu Forum) and the African Nationalist Movement in South Africa, 1938-1951 . Africa World Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-59221-332-0 .

Related Research Articles

Archibald Campbell Mzolisa "A.C." Jordan was a novelist, literary historian and intellectual pioneer of African studies in South Africa.

Zachariah Keodirelang Matthews OLG was a prominent black academic in South Africa, lecturing at South African Native College, where many future leaders of the African continent were among his students.

The following lists events that happened during 1884 in South Africa .

The amaMfengu were a group of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early-mid 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa. These refugees were assimilated into the Xhosa nation and were officially recognized by the then king, Hintsa.

Lovedale , also known as the Lovedale Missionary Institute was a mission station and educational institute in the Victoria East division of the Cape Province, South Africa. It lies 520 metres (1,720 ft) above sea level on the banks of the Tyhume River, a tributary of the Keiskamma River, some 3.2 kilometres (2 mi) north of Alice.

Tiyo Soga was a Xhosa journalist, minister, translator, missionary evangelist, and composer of hymns. Soga was the first black South African to be ordained, and worked to translate the Bible and John Bunyan's classic work Pilgrim's Progress into his native Xhosa language.

John Tengo Jabavu was a political activist and the editor of South Africa's first newspaper to be written in Xhosa.

William Wellington Gqoba was a South African Xhosa poet, translator, and journalist. He was a major nineteenth-century Xhosa writer, whose relatively short life saw him working as a wagonmaker, a clerk, a teacher, a translator of Xhosa and English, and a pastor.

George Milwa Mnyaluza Pemba was a South African painter and writer. He was posthumously awarded the Order of Ikhamanga.

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi was a Xhosa dramatist, essayist, critic, novelist, historian, biographer, translator and poet whose works are regarded as instrumental in standardising the grammar of isiXhosa and preserving the language in the 20th century.

The Hlubi people or AmaHlubi are an AmaMbo ethnic group native to Southern Africa, with the majority of population found in Gauteng, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa.

Milner Langa Kabane Fort Hare Alumni, GCOB was an educator, newspaper editor, human rights activist and a pioneer of the first "Bill of Rights" version in South Africa, which was unanimously adopted by many progressive organisations including the African National Congress in 1943.

John Charles Molteno Jr. M.L.A., was a South African exporter and Member of Parliament.

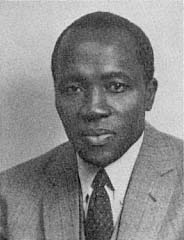

Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu was a Xhosa educationist and politician, and a founder of the All African Convention (AAC), which sought to unite all non-European opposition to the segregationist measure of the South African government. He was the eldest son of political activist and pioneering newspaper editor John Tengo Jabavu, and the father of Noni Jabavu, one of the first African female writers and journalists.

John Knox Bokwe was a South African journalist, Presbyterian minister and one of the most celebrated Xhosa hymn writers and musician. He is best known for his compositions Vuka Deborah , Plea for Africa , and Marriage Song .

Tsala ea Batho / Tsala ea Becauna was a Tswana and English language newspaper based in Kimberly, Cape Province, between 1910 and 1915. It was a politically nonpartisan newspaper, running topical news and opinions that would interest black people in South Africa.

Mpilo Walter Benson Rubusana was the co-founder of the Xhosa language newspaper publication, Izwi Labantu , funded by Cecil John Rhodes, and the first Black person to be elected to the Cape Council (Parliament) in 1909. He also initiated the Native Education Association that contributed towards the formation of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in 1912 and later renamed the African National Congress in 1923.

Ntsikana was a Christian Xhosa prophet, evangelist and hymn writer who is regarded as one of the first Christians to translate Christian ideas and concepts into terms understandable to a Xhosa audience.

William Anderson Soga was the first African to qualify with an MBCM in 1883 and the first African medical doctor to practise in South Africa, as well as being the first African to obtain a doctorate MD. His thesis titled " The ethnology of the Bomvanas of Bomvanaland, an aboriginal tribe in South East Africa, with observations upon the climate and diseases of the country, and the methods of treatment in use among the people " was completed at the University of Glasgow in 1895. He was also ordained as a minister in the United Presbyterian Church 1885 making him one of the first medical missionaries in South Africa. Soga was involved in the running of mission stations, building churches, diagnosis and treatment of patients, research and writing.

- Les Switzer; Donna Switzer (1979). The Black press in South Africa and Lesotho: a descriptive bibliographic guide to African, Coloured, and Indian newspapers, newsletters, and magazines, 1836-1976 . Hall. ISBN 9780816181742 . Online available at Black Press Research Collective

Zulu vs Xhosa: how colonialism used language to divide South Africa’s two biggest ethnic groups

Associate Professor of History, Virginia Military Institute

Disclosure statement

Jochen S. Arndt received funding from the Social Sciences Research Council, American Historical Association, and Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa.

View all partners

South Africa has 12 official languages . The two most dominant are isiZulu and isiXhosa . While the Zulu and Xhosa people share a rich common history, they have also found themselves engaged in ethnic conflict and division, notably during urban wars between 1990 and 1994. A new book, Divided by the Word , examines this history – and how colonisers and African interpreters created the two distinct languages, entrenched by apartheid education. Historian Jochen S. Arndt answers some questions about his book.

What is the key premise of the book?

The beautiful thing about history is that it can help us develop a more complex understanding of the things we consider natural in our daily lives.

People like to believe that their languages have always been there and always played an important role in defining their identity.

But history can show us that what appears to be timeless is, in fact, deeply historical and dependent on the actions of people with ambitions and agendas. My book argues that, as well-defined, standardised languages rather than speech forms (vernaculars), isiZulu and isiXhosa emerged as part of a long historical process that involved a wide range of actors, notably European and US missionaries and African interpreters and intellectuals.

How did you arrive at the project?

During the transition from apartheid to democracy in South Africa between 1990 and 1994, the urban areas reserved for black people around Johannesburg were engulfed in violence that killed thousands. Civil wars are always complex, but the testimonies of participants reveal that many of them understood the conflict as a war between Zulus and Xhosas. I was struck by how they defined Zuluness and Xhosaness. Many said they were Zulu because they spoke the Zulu language, and Xhosa because they spoke the Xhosa language. One haunting testimony was of a self-identifying Zulu:

The Xhosa who were trying to kill us were just looking for your tongue, which language you were.

My book argues that the historical process that produced isiZulu and isiXhosa as distinct languages began at least two centuries before apartheid. It was the product of colonial encounters and both foreign and African ideologies of language.

Was there a time when Zulu and Xhosa identities didn’t exist?

The subtitle of the book is: “Colonial encounters and the remaking of Zulu and Xhosa identities”. I’m not saying that Zulu and Xhosa identities didn’t exist before the languages were well defined, rather that the identities were transformed when these languages came into existence.

Read more: The 100-year-old story of South Africa's first history book in the isiZulu language

Before the 1800s, South Africa’s indigenous people had two key forms of collective belonging: the chiefdom and the clan. There were many chiefdoms and clans, including Zulu and Xhosa ones. The chiefdom was a political entity: a person belonged to a chiefdom because they had submitted or sworn an oath of fealty to a chief. The clan was a genealogical entity: a person belonged because they were born into the clan.

Membership in a chiefdom or a clan had nothing to do with language.

How did the two distinct languages come into existence?

I argue that in the 1800s foreign missionaries and their African interpreters together created distinct isiZulu and isiXhosa out of numerous speech forms.

Protestant missionaries arrived in South Africa in the 1820s. Their primary goal was to convert Africans to Christianity. For them the Bible was the source of revelation. To give Africans direct access to it, it had to be translated.

The problem was there was no written language, so written languages and their geographic reach had to be defined. Consequently, missionaries asked themselves: are the speech forms of the Zulu and Xhosa and of the chiefdoms and clans in between them – such as Mfengu, Thembu, Bhaca, Mpondo, Mpondomise, Hlubi, Cele, Thuli, Qwabe – similar enough to represent a single language into which the Bible can be translated, or do they represent multiple languages?

I suggest that the answer to this question changed over time for a host of reasons, perhaps most importantly due to the influence of African interpreters. Missionaries depended on interpreters, who had their own ideas about language. The decision to think of isiZulu and isiXhosa as two separate languages can to some extent be traced back to these interpreters.

Education played the crucial role in people identifying with these languages. It involved Africans and non-Africans, as lawmakers, superintendents of education and teachers, promoting isiZulu and isiXhosa as part of “mother tongue” education in various school settings between the middle of the 1800s and the last decade of the 1900s.

How did apartheid entrench this?

Apartheid merely reinforced this trend. Crucial was the Eiselen Commission of 1949, which claimed that isiZulu and isiXhosa were the “bearer of the traditional heritage of the various ethnic groups”. This was like saying that these languages captured the essence of these groups in particularly powerful ways.

To reinforce these group identities, the commission expanded mother tongue education in schools. This for a Mpondo child, for instance, meant studying isiXhosa, and for a Hlubi child meant studying isiZulu. Children gradually assimilated Zulu or Xhosa as their language-based identities.

How is this relevant today?

Post-apartheid South Africa continues to promote the Zulu-Xhosa divide through its own official language policies in schools. In the Eastern Cape, for instance, African pupils will learn standard isiXhosa because it is assumed that their “home language” is a dialect of isiXhosa. In KwaZulu-Natal the same happens with isiZulu. Under this policy, it is very difficult to revive and strengthen identities such as Bhaca or Hlubi.

The only way out of this predicament for the Hlubi and Bhaca is to make language a battleground of their identity politics. I think this best explains why the Hlubi have created an IsiHlubi Language Board and why the Bhaca insist that their speech is not a dialect of isiXhosa.

My point is that we cannot make sense of their need to make these arguments without coming to terms with the long history of the Zulu-Xhosa language divide.

- South African history

- African languages

- African colonialism

- Missionaries

- South African languages

- Zulu history

- Zulu culture

- Xhosa culture

- Missionaries in Africa

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

I-MK ihlabane ngofishi omkhulu eLimpopo

IChiefs ihlulekile ukubungaza uKhune ngewini itabalasa kwiPolokwane

Kuphinde kwancipha amathuba eChampions League iPirates ishaywa yiGalaxy

Kuchithwe isicelo sezintatheli kwelokufa kukaMeyiwa

Isuse ukukhuluma i-video kaDiddy ‘eshaya’ uCassie

OweChiefs ugxeka eyokushikiliswa wukungena kwi-Top 8

Ikhale ngaphansi i-Upington ebimangalele iMilford

Kusungulwe ithimba kwiNSFAS elizobhekana nezinkinga ngezindawo zokuhlala izitshudeni

Owe-EFF nezinhlelo zasemapulazini nasemijondolo eKZN

Kwamukelwe ukugwetshwa kowabulala ngeloli oPhongolo

ITheku lihlomule ngoR500 million kwi-Africa’s Travel Indaba

Ezokungcebeleka.

UKhuzani nomkhankaso othinta amadoda

UThandiswa ukhiphe esezingeni lomhlaba

Ngeke ngisithathe sithembu: Felix Hlophe

Seliyahlangana iqembu lakuleli lama-Olympic

ISharks izithwese ubunzima ngekhadi elibomvu - Plumtree

Injabulo kofakwe okokuqala kumaProteas

U-Usyk uzifake emlandweni enqoba uFury kwesosondonzima

OweMaritzburg usebheke kubaphathi ngekusasa lakhe

Intandokazi.

Kugqugquzelwa abesifazane basebenzise ubuchwepheshe

Kuyabacindezela abesifazane ngokwemali ukushesha ukuthatha umhlalaphansi

Nakekela izinwele noma usukhulile

Usebenzise imali yeqolo eqala ibhizinisi otshala kuma-tunnels

Ungadala izinkinga umjovo owehlisa izinhlungu uma ubeletha

Impilo yabantu.

Aqalile ukudayisa amaveni amasha akwa-LDV

Kuyaqala ukwakhiwa kwefemu yakwaStellantis ezokhiqiza izimoto ezingu-500 000 ngonyaka

Qaphela lokhu uma uthenge imoto ngesikweletu

Libunjwa liseva!

Zenza into eziyithandayo izinkabi zaseNigeria

Isililo sikankosikazi weqabane

Kunemibuzo engaphenduleki ngokushona kuka-Anele

Uyaziphindisela unkosikazi weqabane

Africa Is a Country

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

The Xhosa literary revival

- Use + Republish + Donate

The writer Mphuthumi Ntabeni's new novel explores the deep history of colonialism and resistance in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape Photo by Joshua Dixon on Unsplash

When cooped-up critics and writers connect on social media, their conversations often demand more room. Such was the case in my correspondence with Mphuthumi “Mpush” Ntabeni, which migrated to various messenger platforms before finding its stride on email. We read each other’s books; we related them to other books; we grew an unlikely discussion of Catholic conversion narratives from a deep love of South African intellectual history. Talking to Ntabeni, it is anyone’s guess how one body of texts will lead to another. He is a literary wanderer par excellence, and yet he is far from unmoored. Born and raised in Queenstown, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, he now resides in Cape Town, where he has continued to nurture a far-ranging knowledge of Xhosa history and culture. His first novel, The Broken River Tent , reconstitutes the perspective of a real-life 19th-century chief named Maqoma, of the amaRharhabe branch of amaXhosa who lived west of the Kei River, and were thus among the first African people to encounter white settlers when they arrived on the Cape’s Eastern shores. Ntabeni’s book uses retrospective narration framed by present-day dialogue to offer a Xhosa point of view on that violent encounter, which gave rise to the century-long period of the Xhosa or Cape Frontier Wars (1779-1879) against the British and the Boers.

Published by South Africa’s Blackbird Books imprint in 2018, The Broken River Tent won the debut category of the University of Johannesburg Prize for South African Writing in English the following year. It is not an easy book to slip into: more of a series of conversational and historical collisions than a self-propelling plot, it pairs Maqoma with a contemporary figure named Phila to parse topics ranging from the relevance of psychoanalysis for Africans to the structure and material composition of frontier wagons. One could be forgiven here for recalling fellow South African J.M. Coetzee’s early novels ( In the Heart of the Country , especially), owing not least to Phila’s “hyperanalytical” disposition. Ntabeni’s style, however, is marked not by the stymying force of endless self-reflection, but by the exuberance of a mind eager to unfurl its abundant stores. A single paragraph of the book moves rapidly from Steve Biko to Soren Kierkegaard to the biblical Job, with its dialogue lubricated by cheap whiskey. This is Ntabeni’s approach to fiction in a nutshell: high-octane and expansively informed.

This interview took place on Google Docs between Baltimore and Johannesburg, where Ntabeni has just settled into a four-month writer’s fellowship at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study, housed at the University of Johannesburg. With lockdowns still in place internationally and his work on a third novel beginning in earnest, it seemed like the perfect time to present his ideas to the AIAC readership. What follows has been edited for clarity and flow.

I’m glad we are finally getting around to this, Mpush—your novel was one of the first I read when the pandemic lockdowns started. I know that it’s intended to be part of a trilogy, so I’ll jump right in by asking you what it is that appeals to you about that format for this project. Are you intentionally in dialogue with other famous African trilogies? (Achebe, Mahfouz, and Dangarembga all come to mind, though Okri is perhaps the closest to The Broken River Tent in its merging of spiritual and historical concerns.) Or is there some intrinsic quality of the trilogy that you see your story as making use of?

Well, I’m happy to be here and finally do this with you. Thanks for inviting me. The trilogy was not my original idea. Come to think of it, even writing a book was never my original intention. I was just eager to know about my own history and so I started researching it on my own. I knew very little about it because we had not really been taught it at school or at home. When I thought I had done enough and was even beginning to form my own opinions about it, I started asking myself how I could make other people aware of it, especially the ones directly affected by it, like myself. That is when the idea of the book came to mind. I didn’t want to just translate the material I found in the archives. I wanted to find a way of making that history live, resurrect it if you like, so that non-professional historians like myself would also be interested in it. There was also the issue of gaps in historical facts I found and wished to fill by what I call an “informed imagination,” that is, by inserting psychological and emotional energy into known or unknown historical facts without betraying their true spirit. In that way the genre of historical fiction chose me.

As for why this became a plan for a trilogy in particular, I realized at some point that I had accumulated too much historical data in my research. The task of tackling it through a narrative form became formidable. Then, one cold December day, while we were walking on the High Street of Edinburgh, my wife wanted to feed our daughter who was only a month old then. So, we left the snowy streets and quickly dashed into a restaurant for a meal, to give my wife also a chance to breastfeed the baby. As we sat there, looking through the window, I realized that we were sitting across from one of the places Tiyo Zisani Soga used to stay in while studying at the University of Edinburgh. ( Note to readers: Tiyo Soga was a 19th-century South African intellectual best remembered for translating the bible and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress into isiXhosa ). Then the format of how to handle my research material came as a bolt of lightning to me. I would need to divide it into three thematic units: war, religion, and politics. The protagonist for the war section became obvious to me when I recalled that out of nine wars the amaXhosa fought with the British colonial government over 100 years, at least four of them were led by Maqoma , and he was physically present in five. This is why I used his biographical facts as the skeleton of my first book. Soga, the first Xhosa person to be educated in what we call Western education as a reverend, was also the obvious candidate for the religious section, which I’m currently busy with. And S.E.K Mqhayi (1875-1945), the poet, essayist, biographer, and newspaper editor during the foundations of political resistance that led to the foundation of the ANC, also became an obvious choice for me. I wish to call the trilogy “The River People,” and The Broken River Tent is its first installment.

My writing influences are myriad. In fact, I still consider myself an avid reader who acquired an opinion about the events of our history more than I consider myself to be a writer. I like that it is mostly my readers who make me aware of the literary influences on my writing, more than I do myself. I recall being surprised when a brilliant interviewer asked me if I considered The Broken River Tent to be magic realism. I honestly had never thought of it that way, but as I began doing so I saw her point, especially in the section when Maqoma gets a visit from Nxele in Robben Island. I suspect it is also the reason why you see Ben Okri’s influences on my writing, perhaps more with The Famished Road than any other of his works. The Chinua Achebe reference is understandable since we both write about the impact of colonialism on native culture and history. I also learnt a wonderful trick from him of titling books with lines from popular poets.

I want to get back to Soga, so hold that thought. First, though, it also strikes me that you try, in The Broken River Tent , to approximate the cadences and “feel” of Xhosa speech as well as including passages of isiXhosa. This deliberate Africanization of English is often cited as one of Achebe’s key postcolonial innovations. Can you say a bit more about what this technique entailed, for you?

I guess no one can bring forth an African voice in literature without adopting the African traditional style of speaking in proverbs and all. I don’t know how Achebe wrote his characters in his head, but I was deliberate in hearing Maqoma’s voice in Xhosa in mine, before translating it into English. This is why his English is different to that of other people in the novel, like Phila who has been educated in Western ways. I wanted Maqoma’s voice to have raw Xhosa intonations. I felt lucky in the sense that Xhosa is a singing language, so I wanted to translate that for non-Xhosa speakers so that they might be able to understand how the language, like most ancient and classical languages, sings. My sister says I Xhosalized English, and I find this phrase endearing. I was also happy that someone at least noticed the effort I tried to make with Maqoma’s voice. Much of it is acquired from a Xhosa imbongi style of praise singing. Mqhayi has been very helpful in my learning to acquire that voice. I also learn a lot from the Gaelic ancient languages, like Irish shamans and Scottish Picts, my other learning obsessions. I find a lot of commonality in how they infuse English with traits of their traditional languages, which is what gives them distinct and unique ways of speaking English mixed with their mother tongues. I’m afraid I’ll never stop bragging about the richness of the Xhosa language if you don’t stop me…

Brag away! You fill me with regret that I didn’t stick with Xhosa beyond an intro course. And I think that you are onto something important, here, about the significance of your role as a specifically Xhosa novelist to the fractious tradition of South African literature broadly. Black South African writing is most often associated with the urban, the cosmopolitan, and the “modern,” from the trope of “Jim Comes to Joburg” in the mid-20th-century; through the “Drum generation” as it flourished in the 1960s; to the Soweto novels of the 1970s and 1980s; and right up to post-apartheid figures like Phaswane Mpe and K. Sello Duiker . And yet, as you suggest with your reference to Tiyo Soga, there is a much longer and less widely read history of culturally differentiated South African writing; it isn’t simply “English,” “Afrikaans,” and “Black,” as one often hears. I am thinking even of A.C. Jordan here, whose 1940 novel Wrath of the Ancestors , as you well know, deals not so much with overt questions of racial or national identity but with intra-cultural dynamics. The historical tensions within “Xhosaness” are also something you explore in The Broken River Tent . My question, then, is this: has South African literature reached a point where there is room for more prominent literary experimentation in a wider range of constituent traditions? What, in other words, is the relationship between Mpush Ntabeni the Xhosa novelist and Mpush Ntabeni the South African one?

This is an interesting question that I doubt I’ll be able to answer, but I’m going to give it a go. I think all writing cultures that write in English, not as a mother tongue, or perhaps it is better to say those whose background is not necessarily Anglo-Saxon, have a love/hate relationship with the language. Though they understand its usefulness as a lingua franca, they tug on the leash of its dominance and hegemony. They also sometimes find it to be an insufficient means to express their own philological roots. I am not even talking about the language politics here, which Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o argues convincingly even though proper solutions still elude him also. I am talking about the sheer frustration of someone who has been raised and nurtured in say, German or Xhosa, with a much more comprehensive variety of words and phrases to transmit the spirit of their thoughts precisely and succinctly in their own language, and which often are not translatable to English. ( Note to readers: The character of Phila in TBRT was educated in South Africa and Germany .) When writing The Broken River Tent , whenever I encountered that challenge, I chose to use the Xhosa or German phrase alongside what I regarded as a weak explanation of its meaning in English. I don’t see why I should rob words/phrases of the richness of their meaning just to serve the monolinguist.

To answer your question properly, though, the genius of the English language, why it became so popular, I think, is because it is adaptable. It gleans words from various languages to enrich its vocabulary. There’s no reason why that adaptability should only be limited to Germanic, Frank, and Latin languages when English is also spoken in Africa and Asia. South African literature therefore has no choice but to adapt also, it must grow its African roots, and those cannot only be limited to Afrikaans when this country has 11 official languages. Of course, the attitude of some gatekeepers within the publishing industry is not completely convinced about this. They still come with tendencies of recognizing only occidental trends as seeds of progress. But they’ll be compelled by the ruthless hand of necessity.

My going back to the roots of our literature, I mean beyond the so-called Drum Renaissance, was necessitated by my handling of our older historical material. I guess you can say it was serendipitous in that sense. But it was deliberate also. I feel the writings of the Drum generation are too American, black US American to be precise. I hold nothing against them doing what they needed to do with the tools at their disposal then. In fact, I dream of writing a literary biography of Bloke Modisane one day as my excuse to interrogate the zeitgeist of that era, but that’s a topic for another time. Then our cultural issues developed into political ones for the necessary expediency of our freedom. I think it incumbent on us now to revisit our unresolved cultural issues for the sake of mending our identity, especially the crucial parts that were vandalized by colonialism. Your Jordans and your Jolobes interest and influence me more because they were dramatizing Xhosa oral history. To date it is very difficult to distinguish between their writings and that of J.H. Soga, who wrote non-fiction books like The South-Eastern Bantu . J.J.R Jolobe and your Mqhayi dramatize that history in their books. Not only that, they also close the gaps by what I have called their informed imagination. Hence their narrative tonality is closer to the oral history and recitations by imbongi of the amaXhosa because they wrote closer to the transitional period when all that was changing. This is why at this moment of my writing they interest me more than the Drum generation. I find in them a certain Xhosa literary tradition that got truncated into the Americanized cosmopolitanism of the Drum era when our writers moved to the big cities. I wish to trace and follow that tradition. By the way, I was named by my paternal grandpa, who taught himself how to read through Jordan’s book. Hence, I am called Mphuthumi, after the wise counselor of the king in Ingqumbo Yeminyanya .

This is a fascinating response, especially seeing as there are such tricky questions circulating right now about the uses and limitations of a US-originating racial vocabulary in articulating social justice claims within African contexts. I’m quite drawn to your idea of returning through reading and writing to a truncated but robust intranational tradition, veering off course from the more typical emphasis on South Africa’s international visibility during the apartheid years. It suggests a way of getting some intellectual distance from what can feel like overwhelmingly urgent political and cultural entanglements, at the same time as it speaks directly to some of their most prominent concerns: the decolonization of knowledge, black cultural reclamation, and language justice. In this way, The Broken River Tent is quintessential of the historical novel genre, reconstituting the past to advance crucial claims on the present. It also partakes in an ongoing “boom” of African historical fiction, appearing within the same few years as Fred Khumalo’s Dancing the Death Drill (2017), Ayesha Harrunah Atta’s The Hundred Wells of Salaga (2018), and Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light (2019), to name just a few examples. The Broken River Tent , however, does something bold and unusual: it introduces Maqoma as a character in the present, while leaving what we might call his “historicity” intact (his speech, frames of reference, etc.). What motivated this choice, and how would you describe your particular (and wonderfully peculiar) re-engineering of the historical novel?

In the first draft of my manuscript Maqoma was the one telling the story alone. It felt too monologic and like an excuse to retell historical events that affected his life. It was missing the element of clear impact on current events and the status quo of our history. I needed a way to visibly link our present status quo as consequences of those historical events. That is how Phila was born, a character that would not only ask questions to suss out what we need to know from history, but that would also provide a historical tour of the present-day situation to Maqoma and his past era. I am sure you’re aware of this trick from Dante, how he used the ancient poet, Virgil, as his tour guide to his imagined life after death. Because I wanted to talk about this life, I re-tooled that trick a little and made it so that it is Maqoma who comes back as an ancestor to help Phila in this life.

The idea of ancestors as guides for the living is prominent in Xhosa spirituality. Our culture is impatient with numinous things that only speculate about life after death with no bearing on the present situation. I’ve since been pleased to discover that Diana Gabaldon has done a similar thing on her Scottish Outlander historical novels that have been turned into a popular TV series in the UK. I am also aware of the African historical novels you mention though I wanted to introduce the element of what others are now calling magic realism, most popular in Latin American literature of the likes of Gabriel García Márquez. Somehow, he definitely influenced me because I had a period in my life when I was obsessed with his writings, which I had forgotten.

My aim was to also expose the truth of rootlessness even on those who are educated if they’ve no solid sense of their own identity. You know the proverbial saying about a tree without roots. The presence of Maqoma in our times was to give Phila a cultural background and deeper sense of his own identity as a means to assuage his weltschmerz , world-weariness. So, in a way, the book is some sort of bildungsroman for Phila whose character starts out slightly emotionally stunted, something I hope is clear in how he relates to his girlfriend Nandi.

I so admire the easy breadth of your references and reading, which also comes through in the novel itself. This feels like an important reminder that there is no need to choose between centering African traditions and richly engaging with others, Western or not. I want to return, though, to this matter of “roots” and “rootlessness,” which you’ve referenced a few times here. There is a certain skepticism, in your work, of secular and cosmopolitan ways of viewing the world, and particularly of secular modernity’s propensity to find meaning primarily in the self. (It’s no coincidence that Nandi is a psychologist.) While there is, of course, a long record of “troubling” modernity in African writing, you have also been open about your debt to the Catholic intellectual tradition. We might, then, go further afield and think about The Broken River Tent alongside some classic Catholic texts and writers for whom rootlessness was also a paramount concern—G.K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, even Graham Greene in his attempts to work through the mechanics of redemption in a British colonial setting. How has this part of your life informed your fictional practice, in ways that might be surprising to some readers?

Thanks for the complements. I get worried when people, more influenced by so-called “cancel culture,” think the process of, say, decolonizing ourselves means that we need to disregard all Western thinking in order to allow African thought to emerge. As if African thought and vision is too weak to stand its own ground against other world streams of thought. In fact, as a staunch humanist, I strongly believe that global thought, Goethe’s world literature if you like, awaits African thought traditions to be properly assimilated to it.

The human condition is my preoccupation. I have also invested a lot of learning in classical literature. And yes, there was a time classical literature was used as a weapon to propagate imperialism, patriarchy and all that rubbish whose aim was to put a white male on the pedestal to be worshipped and admired. But there’s so much more in it there that speaks to the human condition, including the African condition, that it seems to me a disservice to just throw its baby out with the dirty water of occidental historic faults. So much of it also can be used, and is being used, to counteract all of its wrongs. Hence you see this exciting bloom of the retelling of Homeric stories in particular from the feminine point of view by the likes of Madeline Miller, Pat Barker, and Natalie Heyns, among others. You earlier mentioned Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light , and I am sure you noticed that she has also begun to turn toward ancient classical themes and language to depict the African human condition. Chigozie Obioma, in The Orchestra of Minorities does the same. You shall notice in my next novel, The Wanderers [to be published in April/May] , that I delve into this a little deeper also, to depict the notion of the absurdity of the human condition, which though popularized by Albert Camus, and elaborated through thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard (another strong influence in my thinking), goes back to the classical era of literature and is a Socratic imperative. Camus was greatly influenced by the church fathers, St Augustine in particular. My thinking is also greatly influenced by Augustine. In fact, my conversion to Catholicism has something to do with my immersion into history. Perhaps the major difference between Camus and me is that the absurdity of the human condition has never managed to extinguish the flame of hope within me, not yet anyway. In fact, I define hope as that mysterious and incomprehensible energy that remains in a person when human reason has been defeated by the absurdity of their human condition. Chesterton, of course, is necessary in religious thinking in particular, so that one doesn’t take oneself too seriously to their detriment.

You formulate this belief in decolonization as cultural capaciousness so passionately, and it calls to mind the famous quote by the Roman playwright Terence, himself an African and freed slave: “I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me.” It is, of course, easy enough to cite this in a pat and cliche way, as a conversation-ending shortcut to universalism rather than as a reminder of how much work it takes for a writer to approach something like what you call “the human condition.” I take you to be suggesting that African writers, far from being peripheral to humanism, may in fact have a particular claim to its fulfillment. The title of your forthcoming novel, The Wanderers, is resonant here as well, because it is also the title of a sprawling and ambitious 1971 novel by Es’kia Mphahlele. In this light, what goals for African writing and critical thought broadly do you see your work as advancing? And, more specifically, where do you feel most “at home” within the current South African and continental publishing landscape?

I am extremely happy you picked up my association with the quote of Terence, because I had it exactly in mind when I mentioned my preoccupation with the human condition. And yes, I strongly believe the humanistic thread of world thought will only be fulfilled by something whose seed is the African life attitude of ubuntu . And yes, there are deliberate parallels on my forthcoming work with that of the late professor Es’kia Mphahlele in that they’re both exile novels, with mine in Tanzania whereas his was in Nigeria. But far be it to me to dictate where my work will eventually end up within African writing. That will depend on my readers and the generation that follows us if we’re lucky enough to be of any interest to them. For now, I feel my writing experience is drawing me towards the fractured narratives that are part of our heritage we dropped during the early parts of the 20th century and before. I feel part of our true literary roots are left stranded there and calling to be assimilated to our contemporary thoughts.

Within the current trend of continental publishing it would seem as if Nigeria is the continental trend setter for African literature. There might be many things informing this, like the fact that it is the most populated country on the continent, and so has more people in the diaspora also. And the migrant story is the flavour of the day in the global literary market. But I like what Ghana writers, who by the way you introduced me to, like Nana Oforiatta Ayim, are doing in books such as her debut The God Child , infusing philosophical and psychological substance in their writing that gives its literature more gravitas, rather than merely writing about big social issues without treating them with the deeper thinking they deserve. The charge I am making here is that made by James Baldwin against American writers, “… that they do not describe society, and have no interest in it. They only describe individuals in opposition to it, or isolated from it.” Most of our African migrant writers, especially those writing from the US, seem to have caught this disease. Like Baldwin I am beginning to find fault with it.

As for South Africa, the only way for us to move beyond the schizophrenic bipolar nature of our literary identity is by respecting what came before. It is imperative that we honestly deal with our past in order to gain our roots, a true sense of identity we can successfully depict as our assimilated literature tradition. This separate literary development of the Afrikaans of Afrikaners doing its own things, and that of colored writers doing another, or the black Africans doing theirs, though good for diversity, has not provided us with an assimilated national literary voice also, hence I call it schizophrenic. The problem is we’ve not yet distilled our identities deeply enough to go beyond politics into the understanding of not only our commonalities but our indispensability to each other also. And going to our historical foundations helps us rediscover this.

While I am tempted to go off on a tangent about Ghanaian writing, here, this seems like an ideal and provocative place to stop and let readers process the many points you’ve raised about how literary traditions can and should enrich each other, about the primacy of African histories for seeing that such exchange happens justly, and about historical legacies both recent and long past. I am sure that many readers will also want to read these issues’ fuller exposition in The Broken River Tent ! I, for one, am grateful to you for lending me your mind across these hours on other sides of the earth, and eagerly await publication of The Wanderers . Enkosi, Mpush.

Wonderful, Jeanne. Thanks for taking time to read The Broken River Tent and talk to me about it. Now that I am busy with my third manuscript, I feel The Broken River Tent is still the book that gave me the most trouble with research and writing process. It tested not only my intellectual but psychological strength also. I was not ready to encounter the rawness of the archives. It took some getting used to working with the material objectively, disregarding the anger it provoked in me as a Xhosa person, because hardly any of these historical sources ever try to see things from the perspective of the amaXhosa. That is what inspired me to write the book, that wanting to tell things, for once, from our perspective.

Further Reading

Letters of resistance

- Athambile Masola

An anthology series, Women Writing Africa , restores women’s writing to the public archive.

A Revolution in Many Tongues

- Mukoma wa Ngugi

There is not a single journal devoted to literary criticism in an African language or any writer residencies that encourage writing in African languages.

African poets for Africa

Badilisha is rare: an African project funded by a mix of government and private art donors, facilitating media access to African poets.

The most interesting bits

- Orlando Reade

Kaleidoscope magazine has done an “Africa” issue; it wants to walk a fine line between identity politics and universalism.

'Black Panther' puts spotlight on Xhosa, a real African language spoken by Nelson Mandela

Xhosa is known affectionately as the "click click language."

— -- The "Black Panther" movie is winning attention for breaking Hollywood norms through its almost entirely black cast and crew, powerful black leading ladies and a superhero who is not, for once, white.

But the movie’s cultural significance goes beyond the race of its characters to the language they speak.

Xhosa, known affectionately as the ‘click click language,’ takes its name from a people in mostly southern Africa who speak it.

One of the official languages of South Africa and the native tongue of the late Nelson Mandela , Xhosa is now spoken by around 8 million people.

One of them is South African singer and actress Zolani Mahola, lead singer of Freshlyground.

Zolani sang in Xhosa alongside Shakira for the country’s official World Cup song, ‘Waka Waka, This Time For Africa,' and continues to use the language in her music.

She is thrilled Xhosa is featured in the new movie.

"I’m very pleased," Zolani said. "I think people here will only watch that part of the movie. Just cut and paste it on repeat," she added, laughing.

The singer said she believes Xhosa's inclusion in "Black Panther" may help to build cultural bridges and appreciation.

“We are all realizing how much we have in common," she said. "I think that it’s wonderful to open up people’s windows of experience. I mean, how many people living in Ohio have heard Xhosa? I think it’s awesome.”

In South Africa, mention of the Xhosa language often brings up one of its most famous speakers.

Popular Reads

Johnson disappointed with chaotic House meeting

- May 17, 3:34 PM

Top-ranked golfer Scottie Scheffler arrested

- May 18, 1:46 PM

Teen graduates with doctoral degree

- May 14, 12:07 PM

“One of the most influential leaders of our time was a Xhosa man, Nelson Mandela," Zolani noted. "It was his only language growing up. So I mean it’s high time we had a major Hollywood production using it."

Stars of the movie are also proud of its use of Xhosa, saying it lends the film authenticity.

Danai Gurira, who plays Okoye, told ABC News, “It was very important that when you're telling a story from the African perspective it is very authentic and also very accessible -- which kind of breaks that concept that you can't tell stories from the African perspective on a global scale.”

The actress also talked of the excitement around "speaking a true African language on a global screen.”

Zolani agreed that it's important for artists to speak authentically.

“I think it’s hugely important to sound like yourself, to sound like all the parts that have informed who you are," she said. "For all artists, across all genres, it’s very important to bring that essence in.”

Both Marvel Studios and ABC News are owned by Disney.

Related Topics

Trump attends son Barron's high school graduation

- May 17, 3:44 PM

Woman, 23, killed by rock thrown at her car

- May 17, 10:08 AM

ABC News Live

24/7 coverage of breaking news and live events

Why Do Humans Sing? Traditional Music in 55 Languages Reveals Patterns and Telling Similarities

In a global study, scientists recorded themselves singing and playing music from their own cultures to examine the evolution of song

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ChristianThorsberg_Headshot.png)

Christian Thorsberg

Daily Correspondent

:focal(512x288:513x289)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f6/96/f696d107-a38b-4554-be99-d0089e6a4128/music1.jpg)

The human voice is perhaps the oldest and most diverse musical instrument we know, capable of both speech and song. But the question of why people make music has intrigued and puzzled scientists for centuries.

Is the art form simply an invention, like writing, produced so we can better express ourselves? Did acoustics arise so we could attract mates? Or ward off danger? Is there something deeply evolutionary about music inherent in each of us?

In a new global study, published Monday in the journal Science Advances , 75 researchers from 46 countries decided the best way to try to answer this question was by making melodies themselves. They recorded themselves singing traditional songs from their respective cultures, with 55 languages—including Hokkaido Ainu, Basque, Cherokee, Māori, Rikbaktsa, Ukrainian, Xhosa and Yoruba—represented in all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/b2/71b2141f-5564-4ac2-b489-d0a11cc76f26/music2.jpg)

Then, the researchers recorded themselves simply reciting their songs’ lyrics, without melody. In a third set of recordings, they played wordless versions of the songs on instruments, including the Azerbaijani tar, bamboo flute and clapping. They also described the songs with spoken words.

“I have downloaded all of their singing and speaking onto my phone,” senior author Patrick Savage , a comparative musicologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, tells Forbes ’ Eva Amsen. “And sometimes I just put it on shuffle as I’m walking around. I really love listening to their songs.”

Savage and others analyzed the various recordings with two key questions in mind: Are any acoustic features reliably different between song and speech across cultures? And are any acoustic features reliably shared? They decided to test this by measuring six features across each song, which included tempo as well as pitch height and stability.

When their analysis concluded, they were surprised to find a trio of consistencies: Singing tends to be slower than speaking, people produce more stable pitches while singing than while speaking and singing pitch is overall higher than speaking pitch.

“There are many ways to look at the acoustic features of singing versus speaking, but we found the same three significant features across all the cultures we examined that distinguish song from speech,” Peter Pfordresher , a psychologist at the University at Buffalo and a co-author of the study, says in a statement .

The study doesn’t provide a definitive answer for why humans sing, but the researchers’ leading hypothesis is that music promotes social bonding.

“Slower, more regular and more predictable melodies [may] allow us to synchronize and to harmonize and, through that, to bring us together in a way that language can’t,” Savage tells Scientific American ’s Allison Parshall.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/c2/69c2d7c9-dfe7-4682-9bc2-1879bd9fdd45/music3.jpg)

Lead author Yuto Ozaki , a musicologist from Keio University in Japan, tells the New York Times ’ Carl Zimmer that singing in large groups could have been a way to encourage social cohesion—for community engagement or preparation for conflict—and it may have evolved separately from speech in that regard.

“There is something distinctive about song all around the world as an acoustic signal that perhaps our brains have become attuned to over evolutionary time,” Aniruddh Patel , a psychologist at Tufts University who was not involved in the study, says to the New York Times .

The researchers acknowledge that each language was represented with a very small sample size (most had only a single song) and that the scientists may have chosen simpler melodies that aren’t entirely representative of different genres. Some of the researchers who participated had extensive vocal or instrumental training or accolades—including Shantala Hegde , a Hindustani classical music singer and neuroscientist; Latyr Sy , a Senegalese drummer; and Gakuto Chiba , a national champion of Japan’s Tsugaru-shamisen instrument—so their music might be slightly different from that of a random sample of participants.

Nonetheless, another study of music conducted independently—which has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal but was posted this week on the pre-print server bioRxiv —identified similar patterns in songs representing 21 societies across six continents.

“It shows us that there may be really something that is universal to all humans that cannot simply be explained by culture,” Daniela Sammler , a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics who was not involved in the study, tells the New York Times .

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ChristianThorsberg_Headshot.png)

Christian Thorsberg | READ MORE

Christian Thorsberg is an environmental writer and photographer from Chicago. His work, which often centers on freshwater issues, climate change and subsistence, has appeared in Circle of Blue , Sierra magazine, Discover magazine and Alaska Sporting Journal .

Cities [ edit ]

- 48.483333 135.066667 1 Khabarovsk — the capital and major regional center (population 570,000)

- 50.55 137 3 Komsomolsk-on-Amur — a good sized city that is the steel center of Far Eastern Russia

- 59.383333 143.3 4 Okhotsk — First Russian settlement in the Far East (17th Century) and former headquarters of Vitus Bering, discoverer of the Bering Strait and Alaska; located in the region's far north

- 53.15 140.733333 5 Nikolaevsk-on-Amur

- 49.083333 140.266667 6 Vanino

- 48.966667 140.283333 7 Sovetskaya Gavan

- 48.748889 135.646111 8 Sikachi-Alyan — a small village of the Nanai people with a museum of local culture, opportunities for fine Nanai dining, and 13000 year old Nanai cliff drawings

Other destinations [ edit ]

- 57.104283 138.257106 4 Dzhugdzhursky Nature Reserve

- 48.204944 134.858911 5 Bolshekhekhtsirsky Nature Reserve

- 48.10582 135.136973 7 Vladimirovka , located miles and miles away from Komsomolsk, a native village of Negidals.

Understand [ edit ]

Geography [ edit ]

Khabarovsk Krai occupies a long swathe of Russia's Pacific coastline, a full 2000 kilometers of it, going as far south as Sakhalin and north to Magadan Oblast . At nearly 800.000 km², it's Russias fourth largest province. In the north, taiga and tundra prevail, deciduous forests in the south, and swampy forests in the central areas around Nikolaevsk-on-Amur . As a testament to its size there are more than 50 thousand lakes to fish in, more rivers and streams than you would care to count, and several mountain ranges intersect the region, including the northern reaches of the Sikhote-Alin mountains shared with Primorsky krai. The highest point is Mount Bery, towering nearly in fact, three quarters of the area is occupied by mountains and plateaus.

Biodiversity [ edit ]

The diversity of purely North animals like brown bear and sheer South representatives like Eastern softshell spiny turtle (Trionix) is backed by the legend that God would mix the rest of seeds and animals when somebody told him about missing spot on Earth.

One can encounter pine-tree and wild Far-Eastern grape which came definitely from the South. Its blue round berries with sour taste are cultivated in gardens to produce home wine.

Like Trionix many species are listed in the Red Book.

Culture [ edit ]

Japanese director Akira Kurosawa's 1975 film Dersu Uzala, based on a book by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev, describes the friendship of a Russian explorer and his Nanai guide named Dersu Uzala. (Wikipedia)

Aboriginal culture within small enclaves across the krai are Nanai, Ulchi, Manchur, Orochi, Udege, Negidal, Nivkhi, Evenki and varies in each settlement.

Facts [ edit ]

Talk [ edit ].

See Russian phrasebook .

Get in [ edit ]

Khabarovsk is a major transportation hub for the entire Russian Far East and will likely be any visitor's first stop by either the Trans-Siberian Railway or via Khabarovsk's international airport ( KHV IATA ).

From China there are two entrance routes: one begins on the border with the Heihe - Blagoveshchensk crossing point, the other from Fuyuan town on Amur river. Another possible way is one from Sakhalin, where international ferry operates between Russian Korsakov and Japan's Wakkanai . A one-night bus trip along the federal highway Vladivostok-Khabarovsk is an option for a traveller, if the train carriage by some odd reason is not preferable.

Do [ edit ]

Fishing and hunting in the wild are the major attractions for local villagers, town and city dwellers as well as trekking routes to taiga plains and mountains untouched by humans are favourite activities for all sorts of tourists. Khabarovsk and Komsomolsk mountain bike clubs are all at it. Taiga forest roads are always abuzz with mosquitos in summer and the best seasons for visiting are May and September when the air is not so stifling and the sun is just warm. Winter attracts regional skiers and snowboarders to the ski bases "Holdomi" and "Amut Snow Lake" near Komsomolsk and "Spartak" slopes near Khabarovsk.

Eat [ edit ]

Local food follows traditional Russian cuisine featured with salted bracken, mushrooms, Korean and Chinese and even European dishes served in theme restaurants of two big cities. Don't forget to taste pancakes with a spoonful of linden, wildflower, buckweat honey or a season caviar stuffing.

Stay safe [ edit ]

Snakes and bears are rare attackers in the wild, lest provoked. More dangerous are infectious ticks which are active most of all in spring. Use spray against ticks.

Go next [ edit ]

Khabarovsk is the hub for regional air travel with important flights to Russian destinations Anadyr , Irkutsk , Krasnoyarsk , Magadan , Moscow , Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky , Yakutsk , and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk , as well as international flights to Niigata , Japan and to Seoul , Korea . There are no direct flights to/from the US .

The next major stops to the east on the Trans-Siberian Railway are Ussuriysk and Vladivostok ; to the west, Birobidzhan .

There is a regular ferry from Vanino (the terminus of the Baikal-Amur Mainline ) to Kholmsk , Sakhalin .

- Has custom banner

- Has mapframe

- Has map markers

- See listing with no coordinates

- Has Geo parameter

- Russian Far East

- All destination articles

- Outline regions

- Outline articles

- Region articles

- Bottom-level regions

- Pages with maps

Navigation menu

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Protests Swell in Russia’s Far East in a Stark New Challenge to Putin

Demonstrations in the city of Khabarovsk drew tens of thousands for the third straight weekend. The anger, fueled by the arrest of a popular governor, has little precedent in modern Russia.

By Anton Troianovski

KHABAROVSK, Russia — Watching the passing masses of protesters chanting “Freedom!” and “Putin resign!” while passing drivers honked, applauded and offered high-fives, a sidewalk vendor selling little cucumbers and plastic cups of forest raspberries said she would join in, too, if she did not have to work.

“There will be a revolution,” the vendor, Irina Lukasheva, 56, predicted. “What did our grandfathers fight for? Not for poverty or for the oligarchs sitting over there in the Kremlin.”

The protests in Khabarovsk, a city 4,000 miles east of Moscow, drew tens of thousands of people for a three-mile march through central streets for the third straight week on Saturday . Residents were rallying in support of a popular governor arrested and spirited to Moscow this month — but their remarkable outpouring of anger, which has little precedent in post-Soviet Russia, has emerged as stark testimony to the discontent that President Vladimir V. Putin faces across the country.

Mr. Putin won a tightly scripted referendum less than four weeks ago that rewrote the Constitution to allow him to stay in office until 2036. But the vote, seen as fraudulent by critics and many analysts, provided little but a fig leaf for public disenchantment with corruption, stifled freedoms and stagnant incomes made worse by the pandemic .

“When a person lives not knowing how things are supposed to be, he thinks things are good,” said Artyom Aksyonov, 31, who is in the transportation business and who was handing out water from the trunk of his car to protesters under the baking sun in Lenin Square, on the protest route. “But when you open your eyes to the truth, you realize things were not good. This was all an illusion.”

Across Russia, fear of being detained by the police and the seeming hopelessness of effecting change has largely kept people off the streets. Many Russians also say that whatever Mr. Putin’s faults, the alternative could be worse or lead to greater chaos. For the most part, anti-Kremlin protests have been limited to a few thousand people in Moscow and other big cities, where the authorities usually crack down harshly.

Partly as a result, Mr. Putin remains firmly in control. And independent polling shows he still enjoys a 60 percent approval rating, though the figure has been falling.

But the events in Khabarovsk have shown that the well of discontent is such that minor events can ignite a firestorm. The weekend crowds have been so large that the police have not tried to control them — even though the protesters did not have a permit, let alone a clear leader or organizer.

And with Russians switching en masse from television, which is controlled by the government, to the largely uncensored internet to get their news, the state can easily lose its grip on the narrative.

Khabarovsk, a city of 600,000 close to the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Chinese border, had not seen any protests of much significance since the early 1990s. That changed after July 9, when a SWAT team dragged the governor, Sergei I. Furgal , out of his car and whisked him to Moscow on 15-year-old murder accusations.

Khabarovsk social media forums erupted in indignation over an arrest that looked like a Kremlin move to eliminate a young and well-liked politician who had upset an ally of Mr. Putin in the regional election in 2018.

Tens of thousands spontaneously poured into the streets on July 11 as residents called for protests online, and they re-emerged in greater numbers on July 18. Smaller-scale marches through the city continued daily.

Russian journalists who have been following the protests since the beginning said Saturday’s crowds were the biggest yet. Opposition activists estimated that 50,000 to 100,000 had turned out . City officials said that about 6,500 people had attended , clearly an undercount.

As they have on previous weekends, the protesters gathered in the central Lenin Square by the headquarters of the regional government. They marched down a main street, blocking traffic, and made a three-mile loop through the city center before returning to the square. Police officers walked along casually on the sidewalk, without interfering.

The crowd, some of whom wore face masks stenciled with Mr. Furgal’s name, looked like a cross section of the city, including working-class and middle-class residents, pensioners and young people. The most concrete demand in their chants was that Mr. Furgal face trial in Khabarovsk rather than in Moscow, but they did not shy away from challenging Mr. Putin directly. They shouted “Shame on the Kremlin!”, “Russia, wake up!” and “We are the ones in power!”

Mr. Putin last Monday appointed a 39-year-old politician from outside the region, Mikhail V. Degtyarev, as the acting governor of the Khabarovsk region, angering residents further. Asked whether he would meet with the protesters, Mr. Degtyarev told reporters that he had better things to do than talk to people “screaming outside the windows.”

The Kremlin appears determined to wait the protests out. The regional authorities have warned that they could worsen the spread of the pandemic, announcing on Saturday a sharp rise in coronavirus infections and noting that medical equipment and personnel had arrived from Moscow to aid local hospitals.

One of the protesters, Vadim Serzhantov, a 35-year-old railway company employee, said he had held little interest in politics until recently. The arrest of Mr. Furgal, whom residents praise for populist moves such as cutting back on officials’ perks, was a turning point, Mr. Serzhantov said.