- 50+ Creative Art Project Ideas For College Students

By: Author The GenTwenty Team

Posted on Last updated: December 13, 2023

Categories College

Art class in college is a time to expand your palette and try new techniques! Here are well over 50 creative art project ideas.

Embarking on art projects is not just a way to fill the time between college lectures and exams; it’s a crucial element of personal and educational growth for college students . Creativity thrives when minds are given the freedom to explore, and art projects offer a unique avenue for this exploration.

As part of art education, art teachers love making projects as part of their lesson plans, whether for college or high school students. It’s a fun way for art students to show what they have learned and express themselves.

Engaging in various creative projects , whether a passion project or a calling, can enhance an individual’s ability to think laterally, solve problems imaginatively, and express complex ideas visually. These artistic endeavors are not limited to the tangible benefits of improved artistic skills but extend to bolstering academic performance and personal well-being.

As the canvas of college life stretches out, students are encouraged to paint their paths with broad strokes, dabbling in a medley of art ideas from traditional painting techniques to digital expressions in graphic design . Every student has the opportunity to craft a unique art portfolio , develop a rich tapestry of skills, and weave their narrative through creative expression .

In this blog post, we will cover a plethora creative art project ideas for college students to try. Make note of what speaks to you!

50 Creative Art Project Ideas For College Students

Here are 50 creative art project ideas suitable for college-level students:

- Create a self-portrait using abstract shapes, colors, and textures to represent different aspects of your personality. Use white paper and oil pastels or acrylic paint or do something more creative and use only materials from the natural world on black paper. The options are endless.

- Gather random objects and create a sculpture by assembling them in a unique and interesting way.

- Create a collage using photographs, combining and layering images to tell a visual story.

- Utilize 3D printing technology to produce a sculpture or object that explores form and structure.

- Design an installation that engages viewers and encourages them to interact with the artwork.

- Experiment with digital painting using software like Adobe Photoshop or Procreate. Create a virtual bulletin board for a collaborative art project.

- Transform old books into works of art by cutting, folding, and adding your own illustrations.

- Build a sculpture that incorporates movement or responds to external stimuli.

- Create a stop-motion animation using objects, drawings, or clay figures.

- Combine traditional artwork with augmented reality elements using AR apps.

- Construct an art installation using recycled materials to highlight sustainability.

- Experiment with body painting and use the human form as a canvas for photography.

- Design a mosaic using tiles, glass, or other materials to create a visually stunning piece. Take a field trip to local spots and gather materials.

- Explore alternative printmaking techniques like monoprinting, cyanotype, or linocut.

- Use projection mapping to transform the surfaces of objects or buildings with dynamic visuals.

- Create a large-scale installation using ceramic pieces to explore form and texture.

- Craft a sculpture using natural materials like branches, leaves, and stones.

- Experiment with creating a sculpture by making a cast of a part of the human body.

- Keep an art journal documenting your creative process, thoughts, and visual ideas.

- Design an artwork using typography as the primary visual element.

- Develop a virtual reality art experience that immerses viewers in a digital environment. This is a creative way to blend technology and art.

- Create an art installation that involves auditory elements and explores the relationship between sound and visual art.

- Build a detailed miniature world inside a box or container.

- Create poetry by selecting and rearranging words from existing texts, newspapers, or books.

- Stage a live art performance, incorporating elements of theater, dance, or music.

- Experiment with graffiti art techniques, either on canvas or an approved outdoor space.

- Use wire to create intricate sculptures that play with form and negative space.

- Develop a series of fashion illustrations that showcase your unique style.

- Explore the art of glassblowing to create intricate glass sculptures or vessels.

- Combine various materials like fabric, paper, and found objects to create a mixed media collage.

- Experiment with long-exposure photography and light sources to create dynamic and abstract images.

- Create an installation using textiles and fabric to explore texture, color, and form.

- Develop a project that focuses on conveying a conceptual idea through various mediums.

- Take your sketchbook to the streets and create drawings or paintings of urban scenes.

- Collect sounds from your environment and compose a piece of music or an audio installation.

- Create a performance art piece and document it through video. Video project require another set of skills as well but video is highly profitable skill in today’s world.

- Build a shadow box that tells a story or explores a theme using three-dimensional objects.

- Develop a series of landscape paintings exploring different techniques and styles.

- Use augmented reality apps to enhance street art and create interactive experiences.

- Use your body’s movement to create drawings or paintings, capturing the essence of motion.

- Create maps that illustrate personal experiences, emotions, or imaginary worlds.

- Produce an experimental short film that incorporates unconventional storytelling techniques.

- Experiment with fabric dyeing techniques, such as tie-dye or shibori, and create printed patterns.

- Weld or manipulate metal to create sculptures that explore form, balance, and structure. You could even make cookie cutters and then make cookies from what you’ve created for your college art project.

- Design and illustrate your own book, exploring both the narrative and visual aspects.

- Develop a photography series that explores a specific concept or theme.

- Create temporary art installations in natural settings using materials found on-site.

- Design and print your own textiles, exploring pattern and color.

- Create artworks that explore personal or societal views on body image and self-perception.

- Develop an art project with therapeutic goals , addressing personal or social issues through creative expression.

These art project ideas are diverse and can be adapted based on your interests, preferred mediums, and artistic style. Feel free to combine or modify these ideas to create unique and meaningful art projects for your college-level coursework.

Unlocking Your Creativity

College serves as an expansive canvas for young artists, offering an environment brimming with new experiences, diverse perspectives, and stimulating challenges that are tailor-made to fuel the creative fires.

It is in this unique academic setting that college students can harness their life experiences and academic learning as sources of inspiration to funnel into their art.

To tap into this wellspring of creativity, students are encouraged to maintain an open mind, engage in campus activities outside their comfort zone, and utilize their coursework as a muse for their artistic endeavors. Trying new mediums and techniques, such as digital art , sculpture , or printmaking , not only broadens their artistic repertoire, but also cultivates adaptability and innovation in their creative expression.

Embracing the variety of art supplies and art workshops available on campus can further expand their horizons and augment their artistic skills, pushing the boundaries of their usual creative processes. By immersing themselves in college’s vast pool of opportunities, students open the doors to discovering fresh art ideas and new ways of creative expression , setting the stage for a rich and vibrant artistic path.

Budget-Friendly Art Ideas

Embarking on creative endeavors in college need not drain your finances. A thrifty approach to art can involve recycled materials , such as repurposed cardboard, discarded magazines, and reclaimed fabrics, to not only save on costs but also add unique textures to your projects.

Scouring thrift stores and yard sales can unearth affordable art supplies and unexpected materials. Additionally, many art stores offer student discounts , allowing you to access quality resources without the hefty price tag. Be on the lookout for community art swaps or exchanges where you can trade materials with peers.

Embracing a DIY ethos can also inspire you to create your own supplies, for instance, mixing your own paint colors or crafting sketchbooks from recycled paper. The university’s art department may have resources like free workshops or a reuse center, offering an economical gateway to expand your artistic repertoire.

Here Are Some Art Projects for Beginners:

- DIY Canvas Painting: Experiment with simple paint techniques like sponging or finger painting to create abstract designs on canvas. This is a relaxing way to start with painting while learning color theory and composition.

- Papier-Mâché Sculpture: Create sculptures using recycled newspaper and glue. It’s an accessible project for beginners and helps understand three-dimensional forms.

- Basic Printmaking: Use everyday objects such as leaves or cut potatoes to practice printmaking. This teaches pattern-making and the basics of ink application.

- Recycled Art: Reuse materials to build an eco-friendly art piece. It’s a great way to learn about sustainability in art and can involve anything from plastic bottles to old clothing.

- Photography Project: Start with a smartphone or a basic camera and capture themes like ‘A Day in the Life’ or ‘Urban Landscapes’. It helps beginners understand framing and lighting.

- Sketching and Drawing: Begin with pencil sketches focusing on still life or outdoor scenes to hone observation and hand-eye coordination.

- Basic Digital Art: Utilize free digital drawing tools to create artwork on a computer or tablet. It’s an important skill set for modern art practices and encourages understanding of digital mediums.

- Mural Painting: Collaborate on a group mural project utilizing simple shapes and colors to contribute to a larger piece. This helps with planning and executing larger scale works.

Here are Examples of More Advanced Art Project Challenges:

- Large-Scale Mural Painting: Tackle the grandeur of public art by engaging in a mural project that requires planning, collaboration, and a mastery of painting techniques.

- Interactive Sculpture: Challenge both technical and conceptual skills by creating sculptures that require viewer participation or integrate mechanical elements.

- Advanced Printmaking Series: Delve into the complexities of printmaking with a series of related prints that explore advanced techniques such as intaglio or lithography.

- Complex Mixed Media Installations: Push the envelope with an installation that combines various media and engages with the exhibition space in immersive ways.

- Conceptual Photography Project: Develop a photography project with a strong thematic focus, requiring in-depth research and a sophisticated approach to visual storytelling.

Another Idea: Collaborative Pieces and Group Projects

Working together on a collaborative art piece can significantly enhance the experience of creating and learning for college students. Such projects not only merge diverse perspectives and artistic skills but also foster a spirit of community and cooperation.

For instance, a mural painting involving multiple student artists can transform a bland campus wall into a vibrant tapestry of collective expression. Similarly, sculpture installations made from recycled materials encourage students to discuss environmental themes and develop problem-solving skills as a team.

Another inspiring group project could be the creation of a large-scale mixed media piece , where each participant contributes a segment that reflects personal narratives or cultural backgrounds, ultimately weaving a story that is bigger than its parts.

By participating in such endeavors, students learn the vital role of teamwork and shared creativity in accomplishing artistic visions and projects.

Displaying Your Artwork

Once you’ve poured your heart into a piece, finding the right platform to share it can be just as rewarding. An excellent starting point is a digital portfolio , where you can curate and display your work professionally. Websites like Behance or your personal site can serve as a great showcase for potential employers or art schools.

Students should also take advantage of college exhibitions , which not only provide a legitimate space for your artwork but also offer a chance to receive feedback and network. Additionally, social media platforms have become indispensable for artists today, offering a broad audience and engagement opportunities.

Don’t overlook local coffee shops, libraries, or community centers either; they often have space dedicated to local artists. Remember, the act of presenting your art to the public is crucial – it’s a bold statement of your creativity and a significant step in your artistic journey.

Digital Art and Tech Integration

The intersection of art and technology opens up a new realm of possibilities for college students eager to expand their creative toolkit. Digital art tools and software, such as Adobe Photoshop for photo manipulation, Illustrator for vector graphics, and Procreate for digital painting on tablets, provide students with the means to push the boundaries of traditional art forms.

Blender can be used for 3D modeling and animation, while Unity offers an introduction to the world of game design and art. Encouraging the integration of technology in art not only enhances the creative process but also prepares student artists for a digital-centric professional landscape.

By blending traditional painting techniques with graphic design, or incorporating digital elements into sculpture and printmaking, students can create mixed media masterpieces that are unique and innovative. Embracing the digital dimension in art projects allows for endless experimentation and growth in both artistic skills and technological proficiency.

Reflections Through the Canvas

Art projects during college not only serve as a form of creative expression but also play a significant role in personal and professional growth. As you embark on various art endeavors, taking the time to reflect on your artistic journey can be incredibly rewarding.

Documenting your progress through journals, blogs, or visual portfolios allows you to witness your evolution as an artist. This practice isn’t just about preserving memories; it’s a proactive approach to developing your artistic skills and creating a body of work that can be instrumental in your portfolio development.

Such a portfolio can open doors to future opportunities and serve as a testament to your dedication and talent. So, continue to push boundaries, experiment with new techniques, and most importantly, keep creating. Remember, every piece you create is a step towards mastering your craft and cementing your unique artistic voice.

More Resourceful College Posts:

- 20 Comfortable College Dorm Ideas for Guys

- 9 Most Affordable Clothing Stores For College Students

- The Best College Classes You Should Choose To Take

- 10 Stand-Out Tips for Emailing Your College Professor

- 7 Things That You Can Try At A College Party

- 70 Hard Words to Spell for College Students

- 20 Effective, Good Study Habits For College Students To Develop

- The Ultimate College Bucket List – What To Do Before You Graduate

- 40 Activities To Put On Your Activities Resume For College

- 100 College Graduation Cap Ideas

- 100 Epic College Event Ideas for Students on Campus

- How to Throw a College Dorm Party

- The Best Router For a College Apartment and Dorm

- 75 Must-Try Virtual Event Ideas For College Students

- 75 Sorority Event Ideas For Sisterhood Activities

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

How to make an art portfolio for college or university (the ultimate guide)

Last Updated on September 14, 2023

What should be in an art school application portfolio? How do you present a portfolio? What gives you the best chance of being accepted by the art school of your dreams? This article explains how to make an art portfolio for college or university and is packed with tips from leading art and design school admissions staff from around the world. It is written for those who are in the process of creating an application portfolio for a foundation course, certificate, associate or undergraduate degree and contains advice for specific art-related areas, such as Architecture, Fine Art, Graphic Design, Illustration, Interior Design, Animation, Game Design, Film and other creative, visual art-based courses. It is presented along with art and design portfolio examples from students who have recently gained acceptance to a range of art schools from around the world, creating a 9,000 word document that helps guide you through the application process.

What is an art school application portfolio?

In addition to meeting academic requirements, Art and Design Schools, Universities and Colleges typically require a practical art portfolio as part of the application process (this is often accompanied by a personal statement and/or an art school interview – more on this soon). So what is this?

The University of the Arts London gives the following definition of an application portfolio:

A portfolio is a collection of your work, which shows how your skills and ideas have developed over a period of time. It demonstrates your creativity, personality, abilities and commitment, and helps us to evaluate your potential.

Just as every art student is different (with individual strengths, experiences, passions and ideas) every art school has different requirements and expectations. While some universities and colleges have strict criteria when it comes to preparing a portfolio, others are open and flexible. This variation in expectations can leave students uncertain about how to proceed. Even when criteria is clear, applicants may feel overwhelmed and wonder what to draw/paint/make/create, which mediums to use and how to best select and present their work.

Producing an art portfolio is not to be taken lightly. Top art schools often accept very small percentages of applicants. Understanding how to produce a great portfolio is crucial. Although it is impossible to generate a list of criteria that are appropriate for all applicants in every circumstance (there is unfortunately no guaranteed magic formula for creating a winning art portfolio) this article highlights tips from experienced admissions staff and makes general recommendations to help you produce the best university or art college application possible.

A step-by-step guide to creating an art portfolio for college or university

1. research carefully and record the art portfolio requirements for a number of courses that interest you.

Deciding which art or design school is for you is a big decision (our upcoming article ‘how to find the best art school in the world’ will help with this). While you consider your options, it is advisable to apply to a number of different schools, in case you are not accepted into your first choice. There is no shame in applying to college or university and not getting in (many highly successful individuals are not accepted into their university of first choice); but being left with no place to go because you didn’t apply to enough schools is an easily avoidable circumstance!

Create a list of art or design schools that you would be prepared to attend and find their admissions criteria (you can search for art schools in California and New Zealand on this website – more areas coming soon). All university and college art portfolio requirements are different. Record the exact admissions requirements carefully, well in advance, as deadlines can be earlier than you expect and portfolios take a long time to prepare. Print these out, highlight key information and keep on-hand, so that you can refer to them as needed throughout the application process.

In particular, keep careful records of:

- Open Day times

- Application and Portfolio due date/s . If you are currently studying Art at high school, check how the portfolio due dates compare to your own coursework deadlines and exam timetable. In some cases there may be issues with work needing to be in two places at one (i.e. submitted for assessment at high school and delivered to an art school in hardcopy at the same time). This occurs particularly for students studying international qualifications or applying to art schools in different countries, so you need to prepare for this in advance. Mark the deadlines of the schools that you are applying to clearly on your calendar.

- Size and format of work required

- Whether only finished pieces are expected, or whether sketchbooks, development and process work are also welcome (some schools require only finished pieces, particularly in the US; others love to see development work as well).

- Whether submissions are digital, hardcopy reproductions or original artwork . If copies of work must be sent in, find out whether these should be colour photocopies, slides or photographs etc. Find out whether there are specific criteria for time based media (animation/moving image/video/interactive website design and so on).

- Labelling and presentation requirements . Many art schools have precise portfolio presentation requirements, with work labelled or identified in certain formats, with details about titles, dates and materials used, for example. Digital portfolio submission may use online tools such as SlideRoom.

- Whether there are special requirements for international or out-of-state applicants . If you are applying from another location, there may be special application criteria for you. For example, some colleges may accept international portfolios via email, instead of delivered in person.

- Whether supplementary material is needed , for example, a personal statement or written essay (more on this soon). Art schools typically have academic requirements set by the university or college as a whole, which may require a separate application form and a different deadline. You may also be asked to submit images of work or objects that have influenced your work or teacher recommendations, testimonials or reports (only include these if specifically requested).

- Requirements about what to draw / include . Many art and design schools leave applicants free to select what to include within their portfolio. Unless specifically stated, the portfolio should contain primarily visual artwork, not art history assignments, artist analysis or extensive annotation. You may have to submit a combination of personal artwork, work produced in high school classes and/or ‘home tests’, exams or assignments set by the art school you are applying to. In the RISD application portfolio , for example, applicants must respond to three set assignments, such as ‘observe and draw a bicycle, or an interior space’. Some stunning RISD bicycle drawings completed as part of this application portfolio process are shown below:

READ NEXT: How to make an artist website (and why you need one)

As another example, Parsons the New School for Design asks applicants to submit a portfolio as well as the ‘Parsons Challenge’. In the past, this challenge has included instructions such as:

Using any medium or media, explore something usually overlooked within your daily environment. Choose one object, location, or activity. Interpret your discovery in three original pieces. Support each piece of art with an essay of approximately 250 words.

Once you have collected the requirements for the particular degrees you are interested in, the next step is to seek out existing portfolio examples.

2. Look at recent student art portfolio examples to gain a visual understanding of what is expected

Seeing examples of real portfolios is one of the best ways to understand the standard you are aiming for (and to gain your own art portfolio ideas). Many university and college art portfolio examples can be found online or in campus libraries (some art schools retain hardcopy examples to help students the following year – these can be invaluable) and a large number of varied student art portfolio examples are featured in this article below. These illustrate the range of different portfolio styles that are possible and help to show how submissions for particular specialisations or degrees might differ from one another.

If you feel daunted looking at other portfolios, it is worth stressing that is usually the best candidates who display their work (this is indeed the case within this article). Do not despair if your technical skill is not as strong as the work you see: remember art portfolios are assessed upon a wide range of criteria (more on this below). If you have a great academic background, innovative ideas and a passion for the subject, you can trump someone with technical skill who is lacking in creativity and personal drive. You might be surprised to realise how many famous artists do not have flawless observational drawing skill. Showcase your strengths and back yourself.

A portfolio for art school by Grace Camille Lee :

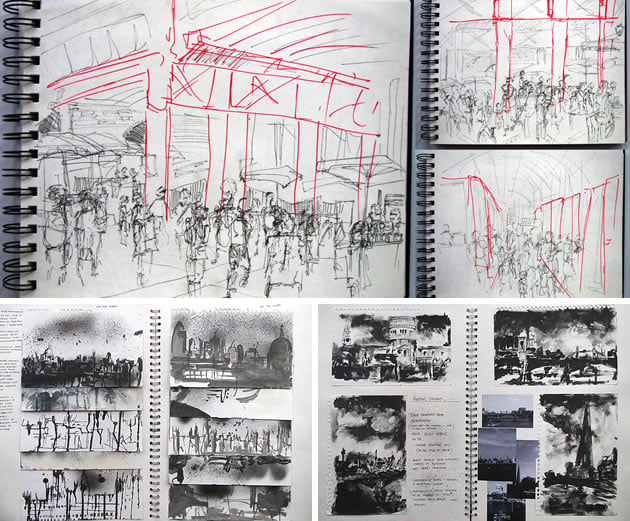

Gray’s School of Art publish a document containing examples of sketchbook pages from student portfolios (some of which are shown below):

A Kingston University application by William Govoni :

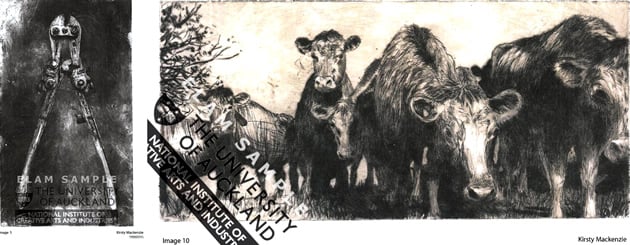

A university application portfolio by Kirsty Mackenzie :

A Kingston University application by Lily Grant :

3. Attend Open Days

Open days are the ideal time to find out whether an art school is the right place for you (read more about this in how to find the best art school in the world – coming soon). Open days are also a great opportunity to find out more about the admissions process and what is expected by a school in terms of application portfolios. (As mentioned above, some art schools have past portfolios on display at the school permanently – in the campus library, for example).

4. Plan your art portfolio, aiming to demonstrate a range of artistic skill and experiences, creative ideas/originality and passion/commitment

This is the most important section of this article, because it is the area where people are most confused. All over the internet applicants beg to know: ‘what should I include in a college art portfolio?’ The answer is this: include a range of recent visual work (completed within the last year or two) that best communicates your artistic skills and experiences, creative ideas/originality and passion/commitment.

The detailed recommendations below explain this further:

a) Emphasise observational drawing

Most art and design courses require applicants to have a certain level of observational drawing skill. This is essential not just for Fine Art specialities, but for many others, such as Architecture and Fashion Design. Even degrees that do not seem to obviously focus upon drawing usually welcome the inclusion of this within an application portfolio. For example, Ringling College of Art and Design states:

For majors without as much drawing involved, the submission of drawing in your portfolio is always welcome but not required.

An observational drawing is a realistic representation of an object or scene that has been viewed directly in real life (as opposed to something that has been imagined or drawn from a photograph) – read more about how to produce great observational drawings . It can be produced using any medium or combination of mediums such as graphite pencil, charcoal, pen, ink and/or paint. For the majority of applicants, it is highly advantageous to demonstrate the ability to observe something in real life and draw it accurately. It is recommended that observational drawing (or painting) from first-hand sources form a substantial part of your portfolio.

The aim is that you:

- Prove to admissions staff that you are able to competently record shape, proportion, tone, perspective, surface qualities, detail, space and form

- Draw in a personal, sensitive way, rather than in a mechanical way (i.e. not a laborious copy of a photograph – drawings from photographs are specifically discouraged). This might involve more creative, expressive, gestural mark-making or the addition of non-realistic elements, textures, materials. In other words, communicate a strong sense of realism, but in a way that also capture an essence of the subject, rather than an exact, rigid copy of a scene. It can help to think about ideas and meanings behind a drawing – selecting a subject that holds meaning or relevance for you, rather than just selecting any random object to draw.

Clara Lieu , Visual Artist and Adjunct Professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, explains the importance of including original observational drawings in a university or college portfolio like this:

Create original work from direct observation. This is hands down the number one, absolutely essential thing to do that many students fail to do. Just doing this one directive will put you light years ahead of other students. Accomplished drawings are above all else, the heart of a successful portfolio when applying at the undergraduate level. You might be a wizard in digital media, but none of that will matter if you have poor drawings.

Szivesen , a portfolio reviewer, explains:

Most schools emphasize drawing from direct observation as their primary basis for the portfolio, no matter what aspect of art you want to study. That’s because basic drawing skills are fundamental and because drawing is a little more likely to be a uniform measure than other areas of art and design.

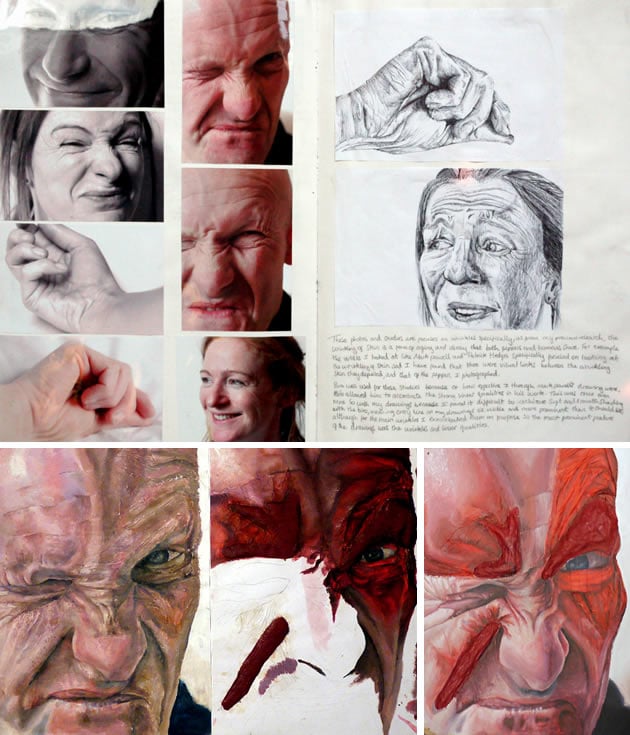

Examples of observational drawings from a university Foundation course application portfolio by Sinead Kirby :

It is worth remembering that you don’t need to attend a formal life drawing class to complete observational figure drawing (although attending such a class can be an excellent experience for artists and art students and is highly recommended if available). The drawings below by Curelea Loana Andreea (part of a university Foundation course application) show captivating examples of observational figure drawings that could take place in a home or classroom setting:

Observational portraits in a university Foundation portfolio by Emma Hooper :

b) Explore a range of subject matter – make art about (and of) lots of interesting things If you are wondering what you should draw: the possibilities are limitless. You may, for example, draw a landscape, still life, portrait, animal, human figure, interior or exterior environment, hands and feet, or any other interesting everyday object – focusing, perhaps, on subject matter that is relevant for your degree (see more about tailoring your application to your particular focus area below) and, more importantly, subject matter that has some meaning and relevance to you. You should try and avoid common or cliché approaches and include a range of different interesting objects and scenes – and do not exactly replicate the work of another artist.

Dorian Angelo , of Ringling College of Art and Design, suggests:

…if you’re not sure what to draw, draw the things in your room. Draw your hands, draw your feet, draw your dog. That’s perfectly fine. Try not to get into any clichés or any traps of drawing all the same thing. We don’t want to see a sketchbook full of horses. We don’t want to see a sketchbook full of just cartoons or anime. Show that you are looking at real life; that you’re looking at different subject matter…

In Ringling College of Art and Design’s Game Art & Design portfolio requirements , they state:

Please do not copy directly from another artist, or include such things as anime, tattoo designs, dragons, unicorns, etc.

In the words of Clara Lieu , Rhode Island School of Design:

Do not copy your work from photographs or other sources. This means no fan art, no anime, no manga, nothing from another artist’s work. Admissions officers have seen hundreds, probably thousands of images from student portfolios. They are well trained to quickly spot artworks that have been copied from photographs or that have been lifted from other resources. It is never, ever good to have fan art in any portfolio. By fan art, I mean drawings of celebrities and other characters that are not your own. That’s basically the kiss of death, and will immediately cause people to see you as nothing more than a hobbyist.

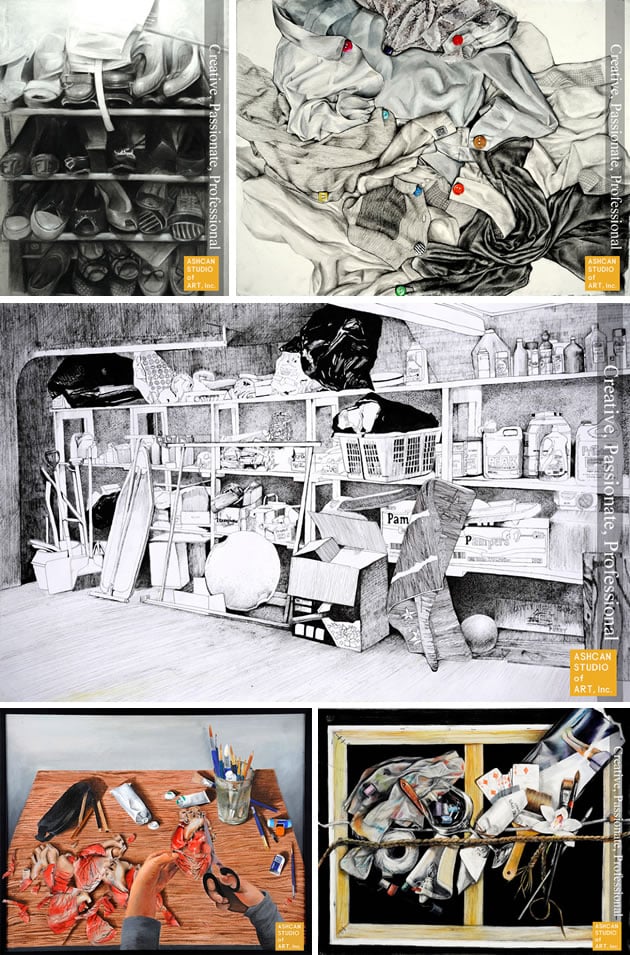

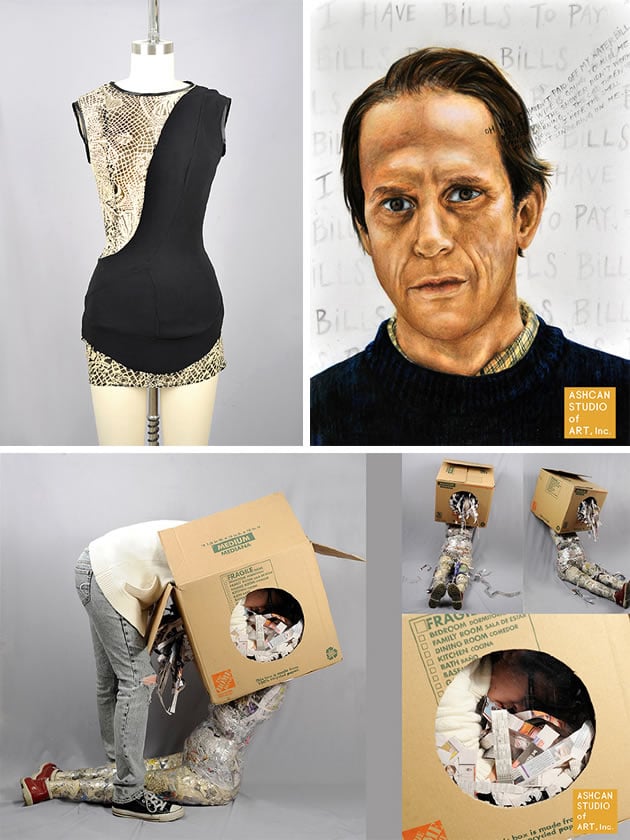

If you are stuck for observational drawing ideas, these examples by students in portfolio preparation courses at Ashcan Studio of Art may trigger some ideas.

Artwork by Suyeon Moon (shoes, top left) (accepted into the Parsons AAS Graphic Design program), Soojin Lee (crumpled clothes, top right), accepted into Parsons Fashion Design program with a 4 year scholarship, Insuk Kang (shelving scene, upper middle), accepted into Parsons Fashion Design with a 4 year scholarship, Kalene Lee (bottom left) accepted into Pratt, Industrial Design, with a 4 year scholarship and Jiwon Hwang (bottom right), Parson’s Fashion Design with a 4 year scholarship:

For more tips about what to draw, read how to come up with great ideas for an art project .

c) Use a range of mediums, styles, art forms and techniques

Your art portfolio should show a diverse range of skill and visual experiences. Demonstrate that you are able to use and experiment with a range of styles, mediums and techniques and can control, apply and manipulate mediums in a skilful, appropriate and intentional way. Someone who is able to create acrylic paintings, sculptures, prints and pencil drawings, for example, is infinitely more flexible than someone who is only able to sketch only with a pencil. The former applicant demonstrates growth, diversity and a breadth of skill, as well as an interest in learning new things. The latter may be a ‘one trick pony’.

Recommendations:

- Choose a range of mediums that highlight your artistic strengths. Use wet and dry mediums (graphite, charcoal, ink, pastel, acrylic, watercolour, oil, ceramics, film etc and other mixed mediums) and paint / draw upon a range of different surfaces (see here for great ideas about things to draw or paint on if you are looking for new ideas), but don’t include weaker work, just for the sake of covering a greater range of mediums .

- Explore a range of appropriate styles . Choose artistic styles that showcase your skill, interests and strengths. Don’t try and guess what the university of art school would prefer (despite common misconceptions, they rarely favour one style of art-making more than another); choose those that align with your strengths.

- Experiment with a variety of tools, techniques, processes and art forms . Unless otherwise specified, an application portfolio may include drawings, paintings, photography, digital media, design, three-dimensional work, web design, animation, video and almost any other type of artwork. This does not mean you should endeavour to include every different technique or art form possible (this would create a scattered and incohesive portfolio) but that you demonstrate that you are willing to experiment and try new art-making experiences, focusing on areas that interest you and highlight your strengths.

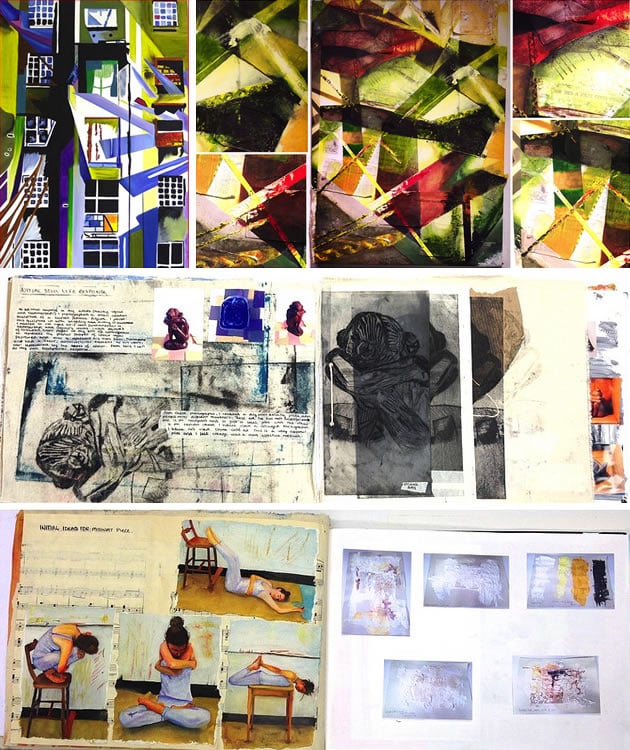

A portfolio by Kisa Sky Shiga , completed as part of a portfolio preparation course at Ashcan Studio of Art:

Printmaking in a university Foundation application by Henry Richardson :

A university Foundation application portfolio by Aqsa Iftikhar :

A university Foundation application portfolio by Ayse Kipri :

e) Include a range of varied, well-balanced compositions – show an ‘eye for aesthetics’

All work – even observational drawings – should show that you understand how to compose an image well, arranging visual elements such as line, shape, tone, texture, colour, form and colour in an pleasing way. Compositions should be well-balanced and varied – with a range of viewpoints/scales included throughout the portfolio.

- Avoid drawing items floating in centre of a page unless this is an intentional, considered decision (see our Art student’s composition guide (coming soon) which explains more about how the formal visual organisation of artwork. Think about the shadows, spaces and surfaces in and around objects. Think carefully about cropping of images and positions of items within each work.

- Select and use appropriate colours, making sure that if multiple works are arranged on one page, the colours work well together too (more on this in the portfolio presentation section below)

- Make sure the proportions and spatial relationships between different elements in graphic designs (such as text, images and space) are carefully considered

f) Include process / development work if permitted

Some art schools – particularly in the US – require that every piece in your application be a finished, realised work. Others – particularly those in the UK and NZ – love to see process, development or sketchbook work. If an art or design school specifically states that this material is permitted, this is an excellent opportunity to flaunt your skills, commitment and depth of knowledge. The research and processes undertaken to develop your work are often as important as the final work itself and allow the selection panel to understand your work in context and see how it has been initiated and developed. Process and development work helps colleges and universities to understand how you think (the ideas and meanings behind pieces, for example) and see that you are able to take an idea from concept and develop it through to a final resolution. It provides evidence that you are able to analyse / experiment / explore and trial different outcomes and make sound critical judgments.

We want to see how you generate and develop ideas from your visual research. It is important that we see how they progress from the starting point right through to the conclusion of your ideas / project. – Grays School of Art , Scotland.

Images of pages from your workbook/s can be very helpful to the selection panel. This could include: evidence of ideas, thinking processes, experimentation and analysis. – Elam School of Fine Arts , University of Auckland, New Zealand

Development work might include sketchbook or workbook pages that show:

- In depth investigations into subject matter (sketches / photography and other visual documentation of first-hand sources)

- Investigations into mediums, materials and techniques and technologies

- Development of concepts, compositions or details

- Written analysis alongside visual work and annotation discussing ideas behind your work

- Evidence of links to the historical, contemporary and/or social context in which works have been made – i.e. connections to artists and real world issues

- Annotated screen captures, contact sheets, and documentation of digital processes

A university Foundation application by Lola :

A university Foundation application by A Level Art student Heather Meredith :

A university Foundation application portfolio by Violet Volchok , who was offered a place on courses at Kingston and Ravensbourne, United Kingdom:

This video contains a good overview of what a portfolio might contain, particularly for universities that request process / development work:

For more tips about producing great process work, you might find it helpful to read our guide to producing an outstanding high school art sketchbook or how to develop ideas in an art project .

Note: If development work is not permitted as part of the portfolio itself, it is usually appropriate to bring this to the interview.

g) Communicate creative ideas: be original

It is important to remember that artistic skill must be accompanied by creativity, original ideas and some form of visual curiosity. In other words, technical skill is no use if you are unable to think of how to put this to use in a unique, interesting way. Someone who is able to generate original and captivating ideas that rip into your heart and soul is far more appealing than someone who produces dull, predictable, yet technically excellent artwork. Although skill is an excellent asset – and a certain level is necessary – applicants to colleges and universities and art schools should not aim to be glorified ‘photocopiers’, but rather the creators of exciting, unexpected visual outcomes. To achieve this within your portfolio, it may help to:

- Be experimental – try different things and push techniques, materials and technology in innovative and unexpected ways

- Make art about something (visually communicate ideas) rather than just laboriously depict a scene – demonstrate your intellectual potential.

- Be yourself – reveal your personality and interests . Never submit art that is an imitation of someone else’s. Aim for artwork that is new, fresh and about something that matters to you. Don’t replicate any of the portfolios you see on this page or elsewhere. Your portfolio should be individual to you. Let your portfolio reflect your strengths, interests and experiences and represent who you are.

On the whole, greater emphasis is put on evidence of your visual curiosity, idea generation and exploration, and your energy, engagement and contextual awareness, than on high level technical skills and finish. – Edinburgh College of Art , Scotland

…[A good portfolio] demonstrates how you can think in innovative and contrasting ways, and shows originality, inventiveness and commitment to being creative. – Massey University , New Zealand

… stand out from the crowd by pushing the boundaries of a prescribed curriculum, personalising a theme or project to demonstrate their invention and creativity. Work that reflects an applicant’s own enthusiasms, thought processes and ideas is always of interest to the selectors. – University of Dundee , Scotland

It’s no good promoting house styles, as that makes all students’ work look the same. If a student is showing a piece of work from a course, it’s important that it also shows a personal theme. – Helen Heery , University of Salford, United Kingdom

A portfolio assignment by Amelia Eaton :

A Fine Art portfolio by Karen Park , completed during a course at Ashcan Studio of Art:

A university Foundation application by Anna Clow :

A Fashion Design portfolio by Halim Ki , completed during a course at Ashcan Studio of Art:

Some great tips are contained in this video by the University of the Arts London about the importance of ideas, enthusiasm and creativity – providing some excellent thoughts, especially for those who might not have gained a strong Art education at high school:

h) Communicate passion, commitment and enthusiasm

Universities want people who will represent their school well – who will go on to do great things that will reflect positively upon their place of study. They want passionate, keen students who will cope with the workload and who intend to actually go on and make use of their degree. This means that you must convey a sense of passion, commitment and enthusiasm within the portfolio (as well as during the interview – more on the art school interview soon). To do this, you can:

- Ensure that work from classroom projects is thorough, personalised, self-motivated (goes the ‘extra mile’).

- Include some personal, independent, self-directed work that has been completed outside of the classroom. This helps to give an indication of your current involvement and interest in the arts.

During the process of reviewing portfolios, the Ruskin staff always look for work that goes beyond the mere fulfilment of School curricula. We search for highly motivated activity, over and above any project-based work, and for a breadth of engagement, a sense of purpose and a strength of opinion in the way the portfolio is edited. Important for us is to be able to discovering a sense of the temperament laying behind the work, and sense the deeper interests that inform the portfolio. We are not interested in finding a particular formula or a specific style, but in signs of energy, ambition, critical reflection and creativity. – Ruskin School of Art , United Kingdom

Personal art is the work done outside of a classroom situation and reflects the artists’ unique interests in use of materials, subject matter and concept. Work can be completed in any media including (but not limited to) drawing, painting, photography, mixed media, digital/computer art, film/video, ceramics, sculpture, animation and performance art. – Kavin Buck , School of Arts and Architecture at the University of California Los Angeles, United States

Involvement in art must be more than casual. – Tom Lightfoot , Rochester Institute of Technology, United States

Emma Rose, who works in the faculty of arts and sciences at Lancaster University, advises that students include some self-generated work – not just the projects that have been assigned on courses. “We want someone with that extra spark – perhaps you’ve gone off with a camera to take interesting photos.” – The Independent

Self-initiated projects (artwork created independent of classroom assignments/exercises) are especially encouraged. – UCLA Department of Art , United States

Ultimately, it’s all about passion and ideas, and so if you include the kinds of things that you’re most excited about, that you’re most proud of, then chances are your portfolio submission will make a strong impression. – Ringling College of Art and Design , United States

i) Tailor your application to suit your degree

Portfolio guidelines for different areas of Art and Design are often similar, but it can be wise to modify your portfolio so that it is appropriate for the degree you are applying for. Rather than creating a completely different set of images for each specialisation or major, however, a submission can be tweaked slightly, so that it showcases relevant strengths and an interest in the area you are applying for (for example, submitting observational drawings of city scenes or building interiors for an architecture application etc ( although this is not necessary – more on architecture portfolios below).

As an example, digital based degrees may like to see evidence of technological awareness and capability and the ability to work with a range of digital platforms, alongside traditional non-digital techniques. This might include time-based interactive work (film, animation, video, website design).

The following list gives some guidance about the sort of material that may be helpful for specific areas, in addition to the items discussed above, such as observational drawing. As with all recommendations in this article, you should refer to the university or college you are applying to for precise requirements.

Graphic Design Portfolios:

- Graphic design print work or web graphics

- Font design or use of typography

- Graphic illustrations

- Video graphics

- Interactive web media and any other related projects

A university Foundation application portfolio by Jacob Wise :

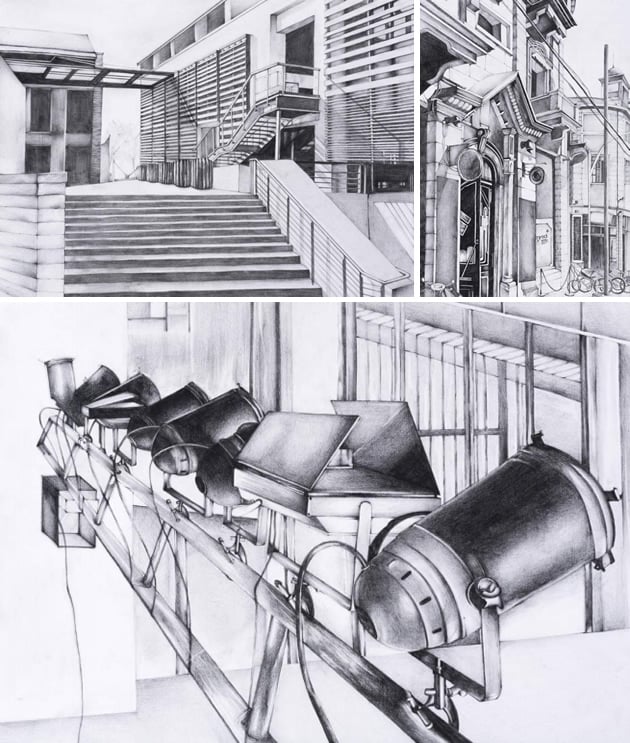

Architecture Portfolios:

- Many students assume that an architecture application portfolio must be filled with drawings of buildings or architectural designs. This is almost always not the case (as with all other recommendations made in this article, you should check the requirements of the particular course you are applying for). Admissions staff typically wish to see evidence of creativity with a range of media and strong observational drawing skill (as described in the first part of this article), including the ability to represent space, perspective and 3D form. This can be achieved through exploration of completely unrelated subject matter, such as still life, landscapes and human form. If you have a choice, however, drawing buildings, manmade structures, interior/exterior spaces, furniture and/or mechanical parts and so on, may help to demonstrate an interest in architectural design.

- Architecture schools usually do NOT require formal technical drawings (instrumental or computer generated plans / orthographic projections etc) and if these are accepted as part of the application portfolio, they are often limited in quantity, so that you include a sufficient range of hand-generated work. You are not expected to understand how to design a building – this is what you learn upon the course.

- Three-dimensional sculptures, installations, casts and/or model constructions can be great to include, as these communicate spatial awareness and an interest in working with 3D form. These might include conceptual models made from cardboard, paper, wire, wood and other found materials, for example.

- Artwork in a wide range of mediums (printmaking / photography etc) are typically accepted.

- Note: Some universities and architecture schools specifically request that the portfolio is not filled with Design Technology work, preferring to see work that has been produced as part of high school Art courses. (Although some high school Design Technology courses provide excellent preparation for architectural degrees, Art courses typically offer a stronger grounding in observational drawing and composition).

Examples of observational drawings submitted as part of an application to the University of Auckland , School of Architecture, New Zealand:

Images from an architecture application portfolio by Irence K , completed while studying at Ashcan Studio of Art:

An architecture portfolio example by Ken Liang , completed under the guidance of Evangelos Limpantoudis from the Architecture School Review who helps students gain admission to top architecture schools from around the world:

Fashion Design Portfolios

- Figure drawings – for example drawings of clothing on models

- Documentation of original sewing, textiles or fashion design projects

Part of a Kingston University Art Foundation application portfolio by Annabelle Holden :

A Fashion Design portfolio by Jinsoo Choi , prepared during a course at Ashcan Studio of Art:

Game Art Portfolios:

- Storyboards

- Original character designs

Product Design Portfolios:

- Subjects like product design often require strong practical, analytical and communication skills, as well as the technical and conceptual ideas and self-motivation required by other art-related degrees. This means that evidence of working with materials and in both 2D and 3D can be beneficial.

Film School Portfolios: Filmmaking may combine many different skills including performing arts, music, literature and writing. As a result, portfolio requirements may be quite different from a traditional art school application. Applications may include:

- Screen shots from original films, animations, videos or digital applications with video excerpts embedded (make sure these are short as admissions staff will not have time to view long reels of footage, and/or captured as a storyboard with screenshots). These may be submitted on DVD or flash drives or as URL links to YouTube, Vimeo or embedded on a personal website or blog (see why Art students should have their own website and how to make one )

- Fashion, costume or set design

- Website design and multimedia work

- Evidence of involvement in theatre or performing arts

- Screenplays and creative writing may also be appropriate

5. Take time to create new artwork and/or improve existing pieces (if required)

Once you have planned what you will include in your portfolio, you should set aside a period of time to produce this. If you have not taken high school Art classes, preparing a folio will take a lot of work – about 6 months to complete a portfolio from scratch (remember it is ideal to create more work than is needed, so that you can carefully edit and remove the weaker pieces). See if your high school Art teacher can help (even if you don’t take Art). An experienced teacher will often have a long history of helping / observing students apply and may have a good knowledge of what helped successful candidates in the past. If your own art teacher is not experienced with helping students apply to university – or you feel you need more help preparing your portfolio – find out if there are local courses or workshops that address how to make a portfolio for art school. Portfolio preparation classes are often run by the universities / colleges themselves. These may be relatively inexpensive weekend workshops or be yearlong, such as Foundation or Art portfolio courses. Making a portfolio can feel less daunting when you produce work with a class of others and seeing others produce work can be motivating and inspirational.

You will likely have to use a considerable portion of your holiday and vacation time to create work or improve existing pieces – as well as generate personal work outside of your curriculum or complete ‘home tests’ or assignments if required.

The most important detail of preparing your portfolio for college admissions is to remember to give yourself plenty of time and have fun with it. It is almost impossible to create quality work if you are nervous and under a time constraint. Don’t wait until the last minute, and make enough work so you can edit together the best portfolio for each school you plan to apply to. – Kavin Buck , School of Arts and Architecture at the University of California Los Angeles, United States

When it says put together a portfolio of 12 pieces, it doesn’t necessarily mean just make 12 pieces. It’s easier to just make, make and make and then narrow it down to 12 pieces. Not only will you have more to choose from, an admissions counselor during a portfolio review can help you decide what to submit for a final application. So don’t limit yourself, just create! Katie , Admissions Counsellor, Parsons, United States

A University Foundation application portfolio by Nina Cavaviuti :

6. Select and Review Work

Once you have completed a significant body of work, seek feedback and modify / improve / redo pieces. Don’t leave this until the last minute, because you will run out of time if changes are needed. Build in reflective time – time to set it aside and come back to it with fresh eyes.

This excellent video by Paul Stanford, Head of Department of the Foundation Course in Art and Design at Kingston University, shows the evaluation of an average student portfolio to be offered a place. It highlights the importance of editing a portfolio carefully and eliminating weaker work, as well as ending a portfolio well, so that the final impression is a good one.

Towards the middle of the portfolio, Paul begins to notice technical deficiencies – ‘ a bit of a boring drawing, you might say ’ – ‘ it’s not a great life drawing, is it? ’ – a reminder that students should only submit work that plays to their strengths. The student’s skill set as a whole and estimated potential is evaluated, with observational drawing skill only one part of this equation.

Most people become too close to their own work and cannot see it objectively. Bring an unbiased person (not friends or family) to assist with your final portfolio selection, ideally someone who has a background in art or design. When selecting work, aim for quality over quantity, avoid repetition and include variety of subject matter, skill and medium.

Read the school’s suggestions for portfolio submission carefully. Most will say “10 to 20 pieces” and I can tell you that more is often not better. If you have ten really strong works to submit, and then the quality level noticeably drops, better to show ten uniformly good works than a whole range. – Anonymous answer on Yahoo

Be selective. …don’t submit work that you are not proud of just for the sake of having variety. – Virginia Commonwealth University

Select projects that show a range of media and subject matter, while still emphasizing your strongest work. – Carnegie Mellon University

It’s good to start with lots of work and then be super selective with what you put in the portfolio… – Charlotte Cook

Some institutions offer the opportunity to have your portfolio reviewed before submission (a ‘preliminary portfolio review’). US students are also able to attend National Portfolio Day , where they are able to receive feedback on their portfolio-in-progress from university and college representatives. These are held all over the US and are highly recommended. Lines are long and you should arrive early to ensure that you are able to speak to the schools of your first choice.

At this event, brace yourself for harsh words. It’s not uncommon for students to be told at National Portfolio Day that they essentially have to start over from scratch because their portfolio is headed in the wrong direction. Reviewers will be candid and direct about the quality and type of work that their school is looking for, so don’t be discouraged if you get a tough critique. Rather, be glad that you got the feedback you needed to get yourself headed in the right direction. – Clara Lieu , Rhode Island School of Design, United States

Accept constructive criticism and advice – don’t be offended (you’ll need to get used to this if you want to go to art school!) – Virginia Commonwealth University , United States

What Should be In a Portfolio? This video from the University of Arts London explains how a good portfolio should have a sense of journey or ‘story unfolding’. It is a good video that helps you understand which pieces to select. It is a good reminder to show a range of creative skills and techniques and well as communicating your personality, interests and a sense of your own experiences.

7. Organise, photograph and present your art portfolio

Presentation of your portfolio is very important. The organisation and arrangement of your portfolio has a direct impact upon the way the work is perceived. A good layout helps to communicate an eye for composition, a professional approach, shows your commitment and desire to attend a university or college: it leaves a positive, memorable impression. Poorly cared for work that is thrown together in a sloppy, thoughtless layout, or is overly decorative and laboured in presentation, significantly detracts from the quality of the artwork. Admissions staff may spend less than five minutes looking at your portfolio, so first impressions count.

This video about preparing a portfolio by University of the Arts London contains some great reminders about presenting a portfolio. In particular, they suggest that you should ‘ put nothing in your portfolio that you can’t talk about’ and organise it so that it is easy to navigate. It also explains that while a portfolio should not be crammed full of everything a student has produced, it should not be over-edited: ‘ pared down so much that we can’t actually see little glimpse of potential ‘.

Carefully photograph work for digital submissions and any work that is three-dimensional/sculptural or that exceeds size specifications for hardcopy submissions (see our guide to photographing art like a pro – coming soon). Reread portfolio presentation requirements carefully to make sure that you present exactly what is required by the admissions departments of each of the schools that you are applying to (especially size and weight restrictions).

Here are some general portfolio presentation tips:

a) Select a simple, professional format that allows your work to be viewed easily.

If a portfolio size isn’t specified, choose something that works well for your own work and that can be transported easily. A3, A2 or A1 is usually fine.

From my own experience, I find A3 is the most ideal (both in education and beyond). A3 marks the perfect balance because you can sufficiently display your artwork effectively, while making it easier to transport. – Recent UK art school applicant from the StudentRoom .

Choose a flat type of art portfolio case or folder that opens and close easily, while protecting work so that it doesn’t get creased. (Avoid rolling work up, as it will be hard to get it to lie flat). The portfolio case may be a spine-mounted leather art portfolio (usually found in all good art retailers – see examples on Amazon) or a clear non-reflective clear file folder, for example. It doesn’t need to be overly expensive: avoid extravagant folders and choose one that is simple, clean and practical.

Although presentation is important for your portfolio, don’t spend loads of time and money buying flashy folders advises Wendy Rochefort, who is studying a foundation degree in Fine Art at Cornwall College. “Simple mounts and a tidy finish are fine.” – The Independent

Have all sheets securely bound in such a way as to allow all sheets to lie flat when the portfolio is open. Be able to be easily and safely handled. There should be no exposed metal binders, staples or similar fittings. Sheet metal or other heavy or sharp materials should not be used for portfolio covers. – School of Architecture , University of Auckland, New Zealand

Choose plain, neutral portfolio colours (black, grey, white etc) and avoid busy, decorative or patterned presentations (you want emphasis to remain on your artwork). Similarly, avoid reflective surfaces that hamper vision (for example, glazing paintings or clearfiles with shiny plastic).

Keep the presentation format uncluttered and relevant. Avoid over decorating your portfolio as this can detract from the content. – University of the Arts London , United Kingdom

b) Order the work in a logical and aesthetically pleasing way .

Start and end with a great piece of work, so that you create a great initial and final impression. Space other great work evenly throughout your portfolio (avoiding a clump of weaker work). Think about grouping similar work together, by medium, subject or style – perhaps as a series of projects – or chronologically. An assessor must be able to ‘understand’ your portfolio and see any connections between pieces (for example, show the creative journey between development work/sketchbook pages and final outcomes). Aim to make it appear coherent, rather than a whole lot of scattered, disconnected pieces.

Narrative is an important element to consider when preparing a portfolio. How work is laid out and displayed changes how it is read, meaning the placement of pieces is vital to showing tutors your best ability in the shortest amount of time. – The Guardian .

Think about the composition of each page – which images are facing each other, whether the colours work well together etc. Consider the relationships between pieces, especially the relationship between sizes, colours and format of work.

Add greater contrast, crop tighter to make more dramatic compositions. Add a little more intense color. You’d be surprised how much stronger your work can look with just a few careful additions. – Karen Kesteloot , a portfolio development coach from PortPrep

c) Avoid unnecessary repetition

If you are asked to submit a specific number of images, ensure that each of these is a different piece of work. Where a certain number of sheets are asked for, it may be possible to mount smaller works onto a single sheet. If you want to submit different angles of one piece of work, it is usually best to digitally submit these on one sheet, or as one image. Read the guidelines of the particular university or college you wish to apply to carefully to find out what is expected.

There is no virtue in quantity alone and candidates should not include multiple colour variations of prints, for example. Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design , United Kingdom

Do not include detail photos of work in your portfolio unless you consider them absolutely necessary. Under no circumstance should more than two detail shots be included. – Yale School of Art

d) Trim / crop everything in a clean environment and attach to the portfolio (if submitting in hardcopy)

- Make sure work is thoroughly dry and that pages will not stick together

- Make sure work is secured well, with no loose work falling out when pages are opened

- Use fixative to stop charcoal, chalk or graphite drawings smudging and ensure that these are not directly facing other artworks in the portfolio. Existing smudges can be erased from drawings using a putty rubber, prior to spraying with fixative.

- Avoid fold out flaps, and other irritating formats that may distract or irritate the viewer

- Make sure photographs are focused, free of fingerprints, printed on matt (non-reflective) paper and are large enough to see details clearly

- Don’t mount things with distracting borders (it is not usually necessary to mount or mat your work); faming work is unnecessary. Let the work stand on its own. A clean, professional and minimal style is usually ideal, as described above.

e) Presentation of digital work (if submitting online or upon DVD or memory stick)

- If you wish to include digital material with a hardcopy submission, ensure that the art school you are applying to is able to view work digital material in particular format (video / CD etc). Check carefully what type of new media presentations they accept and accompany this with a printed hardcopy version (screenshots etc) and a note about the programmes used, in case difficulties arise.

- Label all digital files sensibly, such as firstname-lastname-application.pdf rather than 4690243fxz.pdf

- Ensure images reflect the true colour and appearance of the artwork and are cropped correctly, without unrelated, disctracting background items

- Ensure moving image or video footage is cropped to a sensible length (admissions staff usually have tight time limitations)

- Consider embedding videos upon your own website, rather than as a link to youtube / vimeo. This creates a much more professional backdrop to your application (see how to create your own website ).

- As with physical submissions, think carefully about the organisation and grouping of images.

- Save a record of all digital submissions as a backup!

f) Label work clearly but unobtrusively

- Use small, clear writing to label work in a way that doesn’t detract from the artwork. If labelling guidelines are not given (sometimes a separate sheet containing details of each image is required), label work in the corner or on the reverse with the title, mediums, dimensions, dates and additional info as required. Avoid decorative font and excessively large headings.

- Proof for spelling errors and inaccuracies (get someone else to check this too). Make sure all links to digital moving images work.

Want more help with applying to Art school?

This article is accompanied by our Guide to the Art school interview (coming soon) – packed with advice from those who have recently applied. To make sure that you don’t miss out on this article, please make sure that you are subscribed to our newsletter using the sign up form below!

Amiria has been an Art & Design teacher and a Curriculum Co-ordinator for seven years, responsible for the course design and assessment of student work in two high-achieving Auckland schools. She has a Bachelor of Architectural Studies, Bachelor of Architecture (First Class Honours) and a Graduate Diploma of Teaching. Amiria is a CIE Accredited Art & Design Coursework Assessor.

JOIN OVER 21,000 PEOPLE WHO RECEIVE OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

You will be notified first when free resources are available: Art project ideas, teaching handouts, printable lesson plans, tips and advice from experienced teachers. What are you waiting for?

Email Address*

We send emails monthly. And don’t worry, we hate spam too! Unsubscribe at any time.

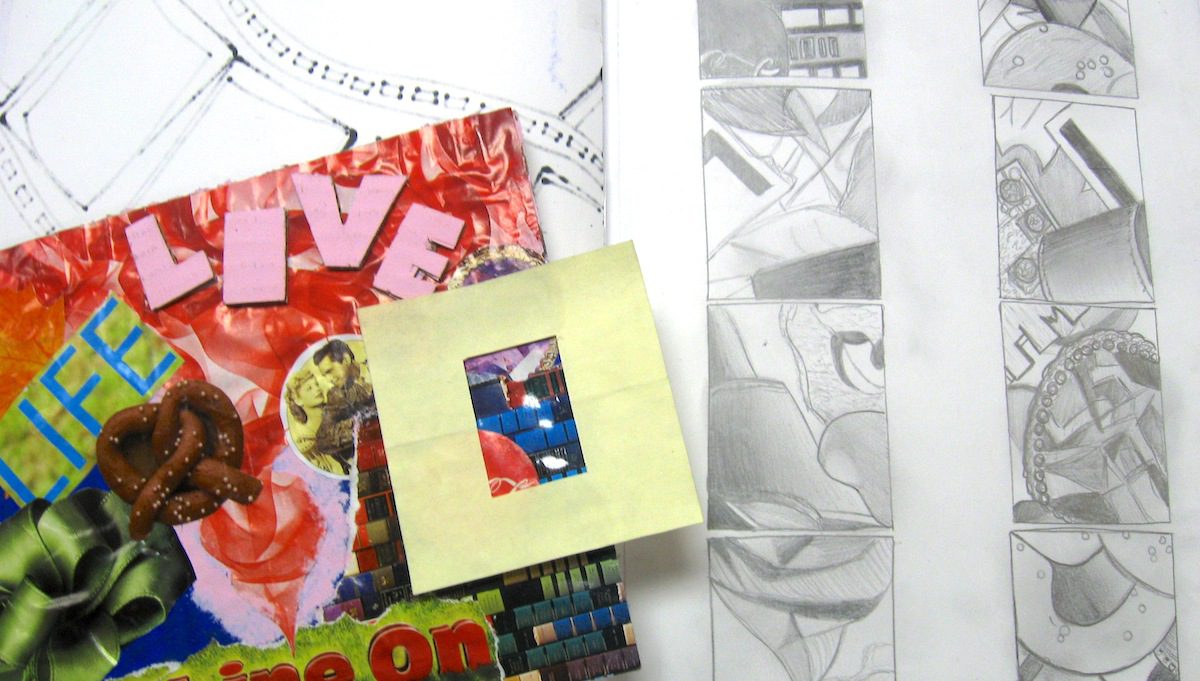

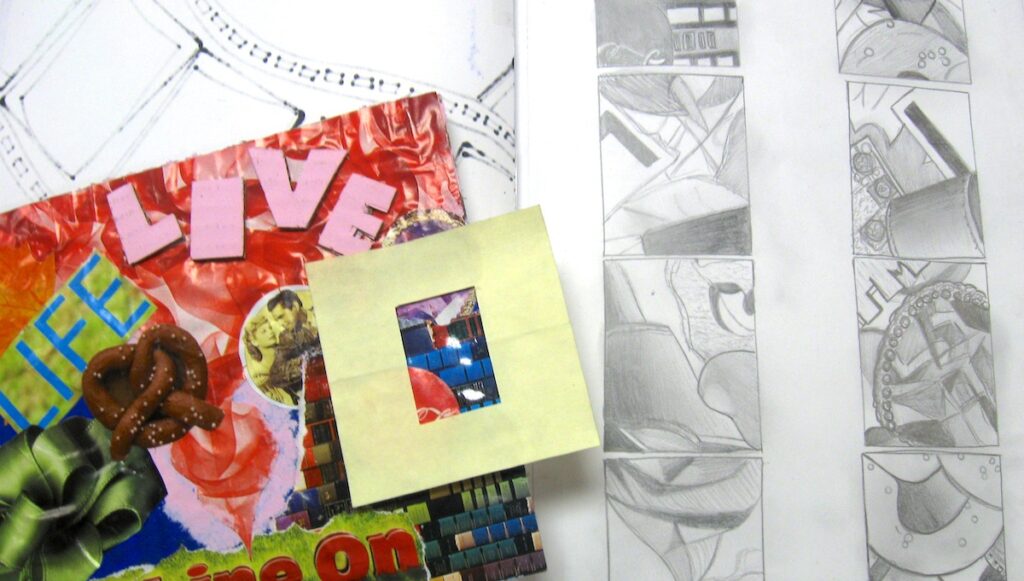

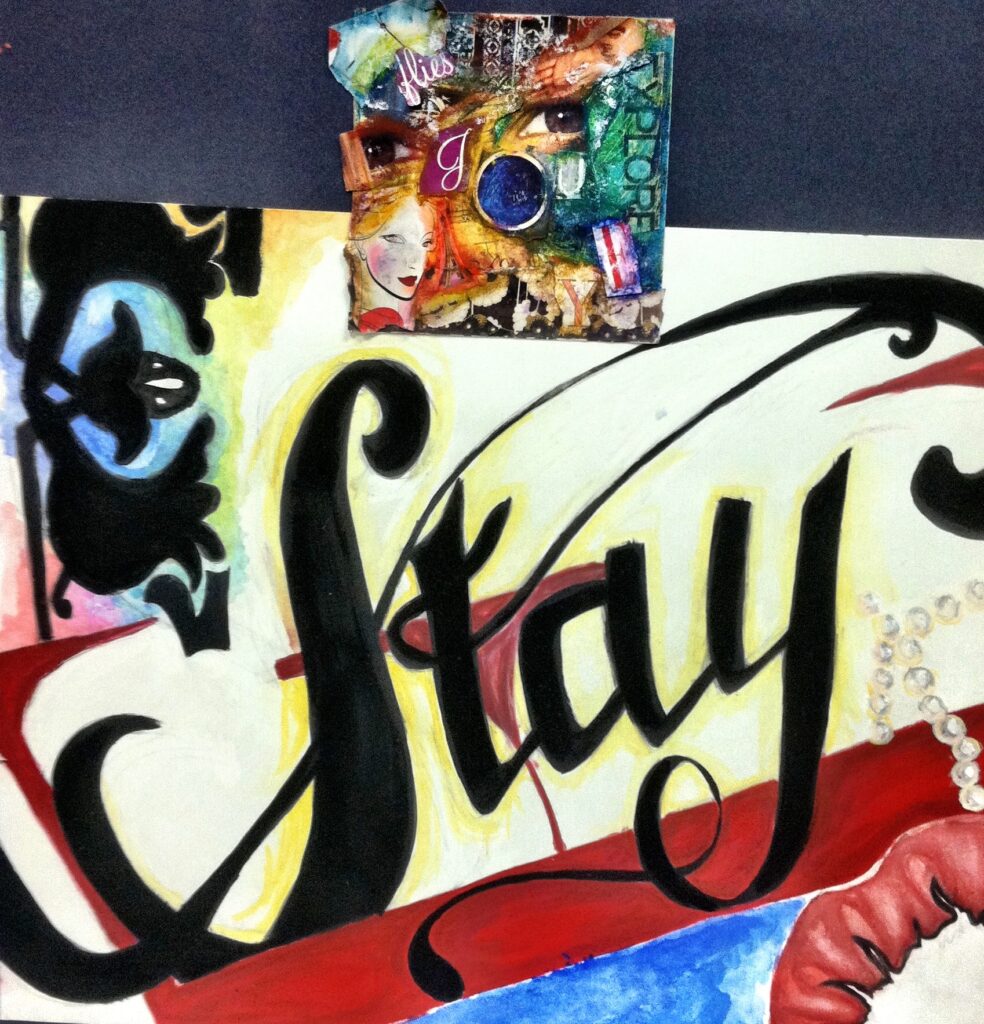

A Creative Collage Lesson for All Students

There are so many reasons to love the art of collage, from the freedom it allows to the powerful stories that can be told through it. In the classroom, I love the fact that students can mix personal items and traditional materials to create something new and uniquely meaningful. And the fact that students don’t feel intimidated when they are encouraged to collage? It’s priceless!

I use collage techniques in many of my lessons. But over the years, one lesson stands out as the most successful: Collage to Canvas.

This lesson not only has students experimenting with the art of collage, but it also has them thinking deeply about composition. It’s a great primer to get them experimenting with visual storytelling. Although I use this lesson with my secondary students, it could certainly be scaled down for elementary kiddos.

I begin the lesson by discussing the art of collage. We discuss how collage means assembling different colors, textures, shapes, and materials to create a new concept.

Then, I share the various types of materials that can be used.

Here are just some of the items I like to provide and have students gather:

- Transparencies

- Tape Transfers

- Manipulated Paper

- Handmade Paper

- Drawings/Sketches

- Photographs

- Personal Items

- Odds and Ends

It’s also a good idea to provide some examples by sharing master collage artists. Artists I’ve used in the past include Georges Braque, Picasso, Kurt Schwitters, Romare Bearden, Radcliffe Bailey, Richard Hamilton, and Robert Rauschenberg. These artists and their works lay the foundation for a wonderful class discussion. When students see this work, they become inspired to begin creating their own collages.

Here are the 7 remaining project steps.

Step 1: set a theme.

There are many themes teachers can use when collaging with their students, but for this specific lesson, I stick with the theme of “self.” I tell students they will be creating a type of “self-portrait” collage. Instead of a traditional portrait, however, they will use colors, textures, magazine images, text, fabrics, photos, and maybe even a few special items from home. The only other parameter I give is that the final collage must be smaller than 6″ x 8.”

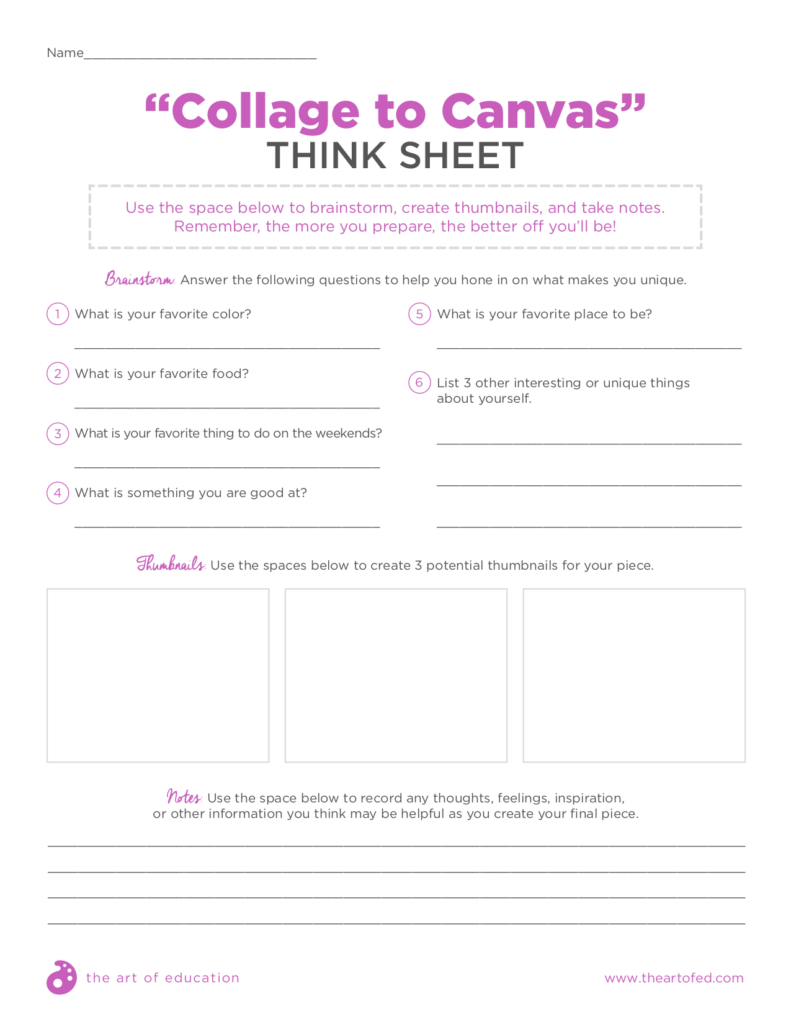

Step 2: Brainstorm

After the theme has been set, I give students a “think sheet” to help them dive deep into what makes them unique and help them brainstorm useful imagery to locate. This acts as a type of mental map for their art piece. You can grab a copy to use with your students below!

Download Now!

Step 3: Collect Imagery

I usually allow students a few days to search for imagery. They have so much fun with this step! Be sure you don’t limit your students to magazine imagery only. My students search for imagery and other items on the Internet, in old photo albums, at their homes, on nature walks, and in other unexpected places. They hold their items in an envelope until they have at least twenty-five things with which to experiment.

Step 4: Create Collage

After students have a variety of items to work with, it’s time to create their “self” collages! Many students choose to collage onto a flat surface, like posterboard or cardboard. However, I don’t limit them to these materials because often they find objects to collage on top of which adds to their visual stories. For example, one year a student collaged on her flip-flops, and another year a student collaged on a paper fan that belonged to her grandmother.

Step 5: Sketch

Once these awesome collages are complete, students take a 3” x 3” sticky note, fold it in half and cut a small viewfinder out of it. This viewfinder is then placed on top of the collage so students can find new compositions within their collage. Students move their viewfinders around, and I often have them sketch out a minimum of six new compositions.

Step 6: Paint

Students are so excited to see these new compositions and find the gems of imagery that appear when they look closely. From this point, they can either choose one or several combined areas and recreate them on a large, 16” x 20” canvas board using acrylic paint.

Students have about a week to paint this new composition onto their canvas board, creating an exciting piece based on their collage work!

Step 7: Combine Work

As a final step, I have my students combine their collages and paintings into one display. My students mount their paintings onto poster board and consider how they want to add their collage. Some students decide to put the collage to the side while others will glue the collage onto the canvas, it’s completely up to them.

This is one of my students’ favorite projects because they have so much freedom to create an artwork with such personal meaning. From the simple task of collaging, many of these pieces end up being award-winning artworks!

How do you incorporate the art of collage into your curriculum?

Do you have your students create “self” art beyond the traditional self-portrait?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.

Debi West is one of AOEU’s adjunct instructors and a former AOEU Writer and NBCT art educator. She loves sharing with others and enthusiastically stands behind her motto, “Together we ART better!”

10 One-Day Photography Activities to Keep Students “Focused” Until the End of the Year

Go Big Before Going Home: Finish the Year with a Collaborative Paper Mache Sculpture

5 Art Activities to Unwind After Testing and Portfolio Submissions

3 Contemporary Artists Making Amazing Work from Materials Found in Every Art Room

- Permissions

- New Releases

- Browse Books

- Upcoming Events

- ERS Overview

- PAS & BAS

- Foreign Language Editions

- Purchase orders

- For Customers

- For Authors

- For Booksellers

- For Librarians

- Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies Series

- Disability, Culture, and Equity Series

- Early Childhood Education Series

- International Perspectives on Education Reform Series

- Language and Literacy Series

- Multicultural Education Series

- Practitioner Inquiry Series

- Research and Practice in Social Studies Series

- School : Questions

- Speculative Education Approaches Series

- Spaces In-between Series

- STEM for Our Youngest Learners Series

- Teaching for Social Justice Series

- Technology, Education—Connections

- Visions of Practice Series

A Guide to Teaching Art at the College Level

Stacey Salazar

Publication Date: September 24, 2021

Available Formats

- Description

Description +

This accessible guide will help studio art and design professors meaningfully and effectively transform their curriculum and pedagogy so that it is relevant to today’s learners. Situating contemporary college teaching within a historic art and design continuum, the author provides a practical framework for considering complex interactions within art and design pedagogy. Readers will gain a deeper appreciation of college students and their learning, an understanding of teaching repertoires, and insight into the local and global contexts that impact teaching and learning and how these are interrelated with studio content. Throughout, Salazar expertly weaves research, theory, and helpful advice that instructors can use to enact a mode of teaching that is responsive to their unique environment. The text examines a variety of educational practices, including reflection, critique, exploration, research, student-to-student interaction, online teaching, intercultural learning, and community-engaged curricula.

Book Features:

- A clear introduction to research and theory in college learning and art education.

- A response to the current shift from studio practice to an investment in teaching practice.

- Reflective prompts, actions, teaching strategies, and recommended resources.

- User-friendly templates ready to customize for the reader’s own content.

Stacey Salazar is the vice provost for graduate studies at the Maryland Institute College of Art. A college art educator for nearly 30 years, she has received professional recognition for her teaching and research. She holds a doctorate in education and a Master of Fine Arts in painting.

“ A Guide to Teaching Art at the College Level translates the formal language of education into straightforward, comprehensible concepts and ties these to practical steps that higher education art instructors can readily apply to their teaching. Drawing on her own classroom experience, Salazar helps artists retool their practice for the instructional and learning demands of the current moment.” — Richard Siegesmund , professor, art and design education, Northern Illinois University