- Health & Research

- Grants & Funding

- Training, Education & Career Development

- News & Media

- About NICHD

Site Maintenance Page

Eunice kennedy shriver national institute of child health and human development (nichd) public web site is currently down for maintenance..

As of the site is down for maintenance. Please check back to this web site at a later time today. The NICHD apologizes for any inconvenience this may cause.

If you require immediate assistance, please email the WebMaster .

Child and Adolescent Development

- First Online: 28 January 2017

Cite this chapter

- Rosalyn H. Shute 3 &

- John D. Hogan 4

11k Accesses

For school psychologists, understanding how children and adolescents develop and learn forms a backdrop to their everyday work, but the many new ‘facts’ shown by empirical studies can be difficult to absorb; nor do they make sense unless brought together within theoretical frameworks that help to guide practice. In this chapter, we explore the idea that child and adolescent development is a moveable feast, across both time and place. This is aimed at providing a helpful perspective for considering the many texts and papers that do focus on ‘facts’. We outline how our understanding of children’s development has evolved as various schools of thought have emerged. While many of the traditional theories continue to provide useful educational, remedial and therapeutic frameworks, there is also a need to take a more critical approach that supports multiple interpretations of human activity and development. With this in mind, we re-visit the idea of norms and milestones, consider the importance of context, reflect on some implications of psychology’s current biological zeitgeist and note a growing movement promoting the idea that we should be listening more seriously to children’s own voices.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

School-Age Development

Children’s Developmental Needs During the Transition to Kindergarten: What Can Research on Social-Emotional, Motivational, Cognitive, and Self-Regulatory Development Tell Us?

Transition to School from the Perspective of the Girls’ and Boys’ Parents

Achenbach, T. M. (2009). The Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Development, findings, theory, and applications . Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth and Families, University of Vermont.

Google Scholar

Ainsworth, M. D., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41 , 49–67.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Book Google Scholar

Ames, L. B. (1996). Louise bates Ames. In D. N. Thompson & J. D. Hogan (Eds.), A history of developmental psychology in autobiography (pp. 1–23). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Anderson, V., Spencer-Smith, M., & Wood, A. (2011). Do children really recover better? Neurobehavioural plasticity after early brain insult. Brain, 134 , 2197–2221. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr103 .

Annan, J., & Priestley, A. (2011). A contemporary story of school psychology. School Psychology International, 33 (3), 325–344. doi: 10.1177/0143034311412845 .

Article Google Scholar

Aries, P. (1962). Centuries of childhood: A social history of family life (R. Baldick, Trans.). New York: Random House.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1 (2), 68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x .

Arnett, J. J. (2013). The evidence for Generation We and against Generation Me. Emerging adulthood, 1 , 5–10. doi: 10.1177/2167696812466842 .

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development . New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

Bjorklund, D. E., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2002). The origins of human nature: Evolutionary developmental psychology . Washington, DC: APA.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1). New York: Basic Books.

Boyce, W. T., & Ellis, B. J. (2005). Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary developmental theory of the origins and function of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology, 17 , 271–301. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050145 .

British Psychological Society. (2011). Response to the American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 development . Retrieved January 16, 2015, from http://www.bps.org.uk/news/british-psychological-still-has-concerns-over-dsm-v

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). Chapter 17: The ecology of developmental processes. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 535–584). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Burman, E. (2008). Deconstructing developmental psychology . London: Routledge. (Original work published 1994)

Burns, M. K. (2011). School psychology research: Combining ecological theory and prevention science. School Psychology Review, 40 (1), 132–139.

Byers, L., Kulitja, S., Lowell, A., & Kruske, S. (2012). ‘Hear our stories’: Child-rearing practices of a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 20 , 293–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2012.01317.x .

Cefai, C. (2011). Chapter 2: A framework for the promotion of social and emotional wellbeing in primary schools. In R. H. Shute, P. T. Slee, R. Murray-Harvey, & K. L. Dix (Eds.), Mental health and wellbeing: Educational perspectives (pp. 17–28). Adelaide: Shannon Research press.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures . The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (Eds.). (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs . Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Crain, W. (2010). Theories of development: Concepts and applications (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Darwin, C. (1877). A biographical sketch of an infant. Mind, 2 , 285–294.

Dekker, S., Lee, N. C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3 , Article 429. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429

Department of Education and Training, Victoria. (2005). Research on learning: Implications for teaching. Edited and abridged extracts . Melbourne: DET. Retrieved October 8, 2014, from www.det.vic.gov.au

Elkind, D. (2011). Developmentally appropriate practice: Curriculum and development in early education (C. Gestwicki, Guest editorial, 4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society . New York: Norton.

Freud, S. (2005). The unconscious . London, UK: Penguin.

Goodman, R., & Scott, S. (1999). Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behavior checklist: Is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27 , 17–24.

Gredler, M. E. (2012). Understanding Vygotsky for the classroom: Is it too late? Educational Psychology Review, 24 , 113–131. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9183-6 .

Greene, S. (2006). Child psychology: Taking account of children at last? The Irish Journal of Psychology, 27 (1/2), 8–15.

Guenther, J. (2015). Analysis of national test scores in very remote Australian schools: Understanding the results through a different lens. In H. Askell-Williams (Ed.), Transforming the future of learning with educational research . Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Hall, G. S. (1883). The contents of children’s minds. Princeton Review, 11 , 249–272.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relation to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education (Vol. 1–2). New York: D. Appleton.

Heary, C., & Guerin, S. (2006). Research with children in psychology: The value of a child-centred approach. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 27 (1/2), 6–7.

Hindman, H. D. (2002). Child labor: An American history . Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Hogan, J. D. (2003). G. Stanley Hall: Educator, innovator, pioneer of developmental psychology. In G. Kimble & M. Wertheimer (Eds.), Portraits of pioneers in psychology (Vol. V, pp. 19–36). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Iossifova, R., & Marmolejo-Ramos, F. (2013). When the body is time: Spatial and temporal deixis in children with visual impairments and sighted children. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34 , 2173–2184.

Jantz, P. B., & Plotts, C. A. (2014). Integrating neuropsychology and school psychology: Potential and pitfalls. Contemporary School Psychology, 18 , 69–80. doi: 10.1007/s40688-013-0006-2 .

Jarvis, J. (2011). Chapter 20: Promoting mental health through inclusive pedagogy. In R. H. Shute, P. T. Slee, R. Murray-Harvey, & K. L. Dix (Eds.), Mental health and wellbeing: Educational perspectives (pp. 237–248). Adelaide: Shannon Research press.

Jiang, X., Kosher, H., Ben-Arieh, A., & Huebner, E. S. (2014). Children’s rights, school psychology, and well-being assessments. Social Indicators Research, 117 , 179–193. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0343-6 .

Jones, M. C. (1924). A laboratory study of fear: The case of Peter. Pedagogical Seminary, 31 , 308–315.

Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2012). Perspectives on the dynamic development of cognitive capacities: Insights from Williams syndrome. Current Opinion in Neurology, 25 , 106–111. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283518130 .

Kennedy, H. (2006). An analysis of assessment and intervention frameworks in educational psychology services, in Scotland. Past, present and possible worlds. School Psychology International, 27 (5), 515–534. doi: 10.1177/0143034306073396 .

Ketelaar, T., & Ellis, B. J. (2000). Are evolutionary explanations unfalsifiable? Evolutionary psychology and the Lakatosian philosophy of science. Psychological Inquiry, 11 (1), 1–21.

Lansdown, G., Jimerson, S. R., & Shahrooz, R. (2014). Children’s rights and school psychology: Children’s right to participation. Journal of School Psychology, 35 , 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.006 .

Lorenz, K. (1961). King Solomon’s ring (M. K. Wilson, Trans.). London: Methuen.

Magai, C., & McFadden, S. H. (1995). The role of emotions in social and personality development: History, theory and research . New York: Plenum.

Matthews, S. H. (2007). A window on the ‘new’ sociology of childhood. Sociology Compass, 1 , 322–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00001.x .

Moon, C., Lagerkrantz, H., & Kuhl, P. K. (2013). Language experience in utero affects vowel perception after birth: A two-country study. Acta Paediatrica, 102 , 156–160. doi: 10.1111/apa.12098 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moriceau, S., & Sullivan, R. M. (2005). Neurobiology of infant attachment. Developmental Neurobiology, 47 (3), 230–242. doi: 10.1002/dev.20093 .

Nsamenang, A. B. (2006). Cultures in early childhood care and education . Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2007, Strong Foundations: Early Childhood Care and Education . Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001474/147442e.pdf

O’Donnell, J. (1985). The origins of behaviorism. American psychology, 1870–1920 . New York: New York University Press.

Oberklaid, F. (2011). Is my child normal? Retrieved October 2, 2014, from http://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2011/september/is-my-child-normal/

Overton, W. F., & Ennis, M. D. (2006). Developmental and behavior-analytic theories: Evolving into complementarity. Human Development, 49 , 143–172. doi: 10.1159/000091893 .

Packenham, M., Shute, R. H., & Reid, R. (2004). A truncated functional behavioral assessment procedure for children with disruptive classroom behaviors. Education and Treatment of Children, 27 (1), 9–25.

Perry, B. D. (1997). Incubated in terror: Neurodevelopmental factors in the “cycle of violence”. In J. D. Osofky (Ed.), Children in a violent society . New York: Guilford.

Ritchie, J., & Ritchie, J. (1979). Growing up in Polynesia . Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Romer, D. (2010). Adolescent risk taking, impulsivity, and brain development: Implications for prevention. Developmental Psychobiology, 52 (3), 263–276. doi: 10.1002/dev.20442 .

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rousseau, J. J. (1914). Emile on education (Foxley, Trans.). New York: Basic Books. (Original work published 1762)

Rutherford, A. (2009). Beyond the box: B. F. Skinner’s technology of behaviour from laboratory to life, 1950s to 1970s . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sattler, J. M. (2008). Assessment of children: Cognitive foundations (5th ed.). La Mesa, CA: Sattler.

Seligman, M. (2002). Authentic happiness . New York: Free Press.

Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children in Society, 15 (2), 107–117.

Shute, R. H. (2015). Transforming the future of learning: People, positivity and pluralism (and even the planet). In H. Askell-Williams (Ed.), Transforming the future of learning with educational research . Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Shute, R. H. (2016). ‘Promotion with parents is challenging’. The role of teacher communication skills and parent-teacher partnerships in school-based mental health initiatives. In R. H. Shute & P. T. Slee (Eds.), Mental health through schools: The way forward . Hove: Routledge.

Shute, R. H., & Slee, P. T. (2015). Child development: Theories and critical perspectives . Hove: Routledge.

Siegel, A. W., & White, S. H. (1982). The child study movement: Early growth and development of the symbolized child. In H. W. Reese (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 17). New York: Academic.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior . Acton, MA: Copley Publishing.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A. (2005). Vineland adaptive behaviour scales (Vineland II) (2nd ed.). Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Pearson Australia.

Spears, B., Slee, P., Campbell, M., & Cross, D. (2011). Educational change and youth voice: Informing school action on cyberbullying. Centre for Strategic Education, Seminar Series Paper 208 . Melbourne, VIC, Australia: CSE.

Strauss, E., Sherman, E. S., & Spreen, O. (2006). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms and commentary (3rd ed., pp. 46–52). Retrieved October 8, 2014, from http://scholar.google.com.au/scholar_url?hl=en&q=http://www.iapsych.com/articles/strauss2006.pdf&sa=X&scisig=AAGBfm0m5ZgjHj9p9Ew9NuSmlUnv9CWiUA&oi=scholarr&ei=ZQUuVKLUGOKsjAKiuoDoBw&ved=0CCQQgAMoADAA

Teo, T. (1997). Developmental psychology and the relevance of a critical metatheoretical reflection. Human Development, 40 , 195–210.

Thelen, E., & Adolph, K. E. (1992). Arnold L. Gesell: The paradox of nature and nurture. Developmental Psychology, 28 , 368–380.

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1994). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Timimi, S., Moncrieff, J., Jureidini, J., Leo, J., Cohen, D., Whitfield, C., … White, R. (2004). A critique of the international consensus statement on ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7 , 59–63.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989). Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations. Accessed October 31, 2014, from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20 , 158–177.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1–14.

Weaver, I. C., et al. (2004). Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience, 7 , 847–854.

Wood, D. (1998). How children think and learn . Oxford: Blackwell. (Original work published 1988)

Yell, M. (1998). The law and special education . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Additional Sources

Fancher, R. E., & Rutherford, A. (2012). Pioneers of psychology (4th ed.). New York: Norton.

Kessen, W. (1979). The American child and other cultural inventions. American Psychologist, 34 , 815–820.

Parke, R. D., Ornstein, P. A., Rieser, J. J., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (Eds.). (1994). A century of developmental psychology . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Thompson, D. N., Hogan, J. D., & Clark, P. M. (2012). Developmental psychology in historical perspective . Chichester: Wiley.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide, SA, 5001, Australia

Rosalyn H. Shute

St John’s University, Jamaica, NY, USA

John D. Hogan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosalyn H. Shute .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychological Sciences, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia

Monica Thielking

St. John’s University, Jamaica, New York, USA

Mark D. Terjesen

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Shute, R.H., Hogan, J.D. (2017). Child and Adolescent Development. In: Thielking, M., Terjesen, M. (eds) Handbook of Australian School Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45166-4_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45166-4_4

Published : 28 January 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-45164-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-45166-4

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Advanced search

Deposit your research

- Open Access

- About UCL Discovery

- UCL Discovery Plus

- REF and open access

- UCL e-theses guidelines

- Notices and policies

UCL Discovery download statistics are currently being regenerated.

We estimate that this process will complete on or before Mon 06-Jul-2020. Until then, reported statistics will be incomplete.

Ecological Influences on Child and Adolescent Development: Evidence from a Philippine Birth Cohort

The largest number of children and young people in history are alive today, so the costs of them failing to realise their potential for development are high. Most live in low-income and lower-middle-income countries (LLMICs), where they are vulnerable to risks that may compromise their development. Yet many risk factors in LLMICs are not well understood. Moreover, recent studies suggest that in addition to the critical first 1,000 days there are several key periods of development in later childhood and adolescence which have received comparatively little research attention. This work responds to the gaps in the evidence, examining the influence of exposure to risks in the physical and social environment on health, education and development outcomes in a birth cohort of children from the Philippines. The first chapter provides a brief introduction to the theoretical and empirical evidence on the risks children face in LLMICs as well as a description of the Philippine country context and the birth cohort. The second chapter tests the associations between infant exposure to sanitation risks and subsequent school survival. The third chapter investigates the effects of housing instability in early to middle childhood on cognitive performance at 11 years of age. And, the fourth chapter examines the links between forms of social marginalisation and adolescent mental health and wellbeing. This work’s findings suggest infant exposure to faecal contamination in the home environment shortens the overall length of time children later spend at school. Preprimary-school age children appear to be at risk of developmental deficits and/or delays as a result of changes to their neighbourhood environment. And, adolescents who are excluded or become disengaged from the important socialising institutions of school and the workplace are at increased risk from developing mental disorders, while among older teens the protective effects associated with being in employment are greater than those linked to being in education.

Archive Staff Only

- Freedom of Information

- Accessibility

- Advanced Search

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Adolescence; Kipke MD, editor. Adolescent Development and the Biology of Puberty: Summary of a Workshop on New Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999.

Adolescent Development and the Biology of Puberty: Summary of a Workshop on New Research.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

Key Findings of Recent Studies

The workshop included a series of panel discussions that focused on adolescence as experienced by both human and nonhuman primates, including neuroendocrine physiology at puberty, the interplay between pubertal development and behavior, and implications for research, policy, and practice. Here we briefly summarize key findings from some of the studies that were discussed at the workshop (also see Crockett and Petersen, 1993; Grumbach and Styne, 1998; Pusey, 1990; Suomi, 1997;1991). As previously noted, this summary is not intended to provide a comprehensive review of the new research in this field; rather, it highlights important new findings that emerged during the workshop presentations and discussions.

- In the United States, the Onset of Puberty Occurs Earlier than was Previously Recognized.

Over the last 150 years, girls' sexual maturation, as measured by the age of menarche, is occurring at younger ages in all developed countries by at least two to three years. In the mid-nineteenth century, the average age at which girls reached menarche was approximately 15. The trend toward earlier menarche is now being documented in developing countries as well. Improved diets and more effective public health measures are the reasons often cited for this trend (Garn, 1992).

Research conducted during the 1990s greatly enhanced researchers' understanding of the age of puberty among girls. For example, although the onset of menarche is still considered to be a significant indicator of the tempo of maturation, researchers now view menarche as a late event in the pubertal process. At the workshop, Frank Biro presented data from the Growth and Health Study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. This longitudinal study enrolled a cohort of over 2,000 girls, ages 9 to 10 years in 1987–1988; approximately half of the sample was white and half was black; the sample was recruited from clinics at three clinical centers located in Richmond, California, Cincinnati, Ohio, and metropolitan Washington, D.C. According to the study design, girls' maturation stage and body mass index were assessed annually; data for other variables, such as household income, nutrition, physical activity, cardiovascular risk factors, self-esteem and self-perception, and other psychosocial measures, were collected biennially (Brown et al., 1998). Almost half of the participants had begun puberty before the onset of the study. According to Biro, indicators of pubertal growth have been observed as early as age 7. These findings suggest that as children experience puberty and other developmental changes at earlier ages, there may be the need to consider how to design and deliver age-appropriate interventions during the middle childhood and preteen years, to help them avoid harmful or risky behaviors and develop a health-promoting lifestyle.

- There is Significant Variation Among Individuals in the Timing of Puberty.

There is variation in both the onset and the tempo of puberty. Research shows that the timing of puberty can affect other aspects of development, especially for girls. Jeanne Brooks-Gunn discussed the findings from a recent study, which recruited a community sample of nearly 2,000 high school students from urban and rural areas of western Oregon. The study found that early-maturing girls and late-maturing boys showed more evidence of adjustment problems than other adolescents (Graber et al., 1997).

- Multiple Factors Affect the Age of Puberty.

Research now suggests that the timing of puberty can be affected by a wide range of factors, including genetic and biological influences, stress and stressful life events, socioeconomic status, environmental toxins, nutrition and diet, exercise, amount of fat and body weight, and the presence of a chronic illness. Research also shows that the family, the peer group, the neighborhood, the school, the workplace, and the broader society have all been shown to influence adolescent developmental outcomes, although it is less clear if these factors influence pubertal development. With respect to school settings, research suggests that the transition from small elementary schools to larger, more anonymous middle schools can be a stressful event in the lives of children (National Research Council, 1993). Some of the stressful influences or events factors mentioned above have been correlated with pubertal timing, but a causal relationship cannot be assumed.

- Stress does not Trigger Puberty, But it does Modulate the Timing of Puberty.

In her remarks at the workshop, Elizabeth Susman took note of research correlating stress and the timing of puberty. 1 A review of this literature shows that researchers observe different effects of stress at different stages of puberty (Susman et al., 1989). For example, stress appears to delay maturation for young adolescents but to precipitate puberty for older adolescents. According to Susman, it makes sense that stress would delay maturation because stress hormones tend to suppress reproductive hormones (Susman, 1997; Graber and Warren, 1992). She added that her research has not yet resolved the question of directionality: Do environmental stressors affect the reproductive hormones, or does the rate of maturation affect the level of circulating stress hormones? Other participants at the meeting noted that social factors influence this process as well. For example, family conflict appears to be associated with earlier menarche in girls (Graber et al., 1995).

- There is some Evidence that, on Average, Girls experience more distress during adolescence than boys.

Some researchers have speculated that, for girls, the transition during puberty brings about greater vulnerability to other environmental stressors (Ge et al., 1995). In particular, a growing literature suggests that the early onset of puberty can have an adverse effect on girls' development (Caspi et al., 1993; Ge et al., 1996). It can affect their physical development (they tend to be shorter and heavier), their behavior (they have higher rates of conduct disorders); and emotional development (they tend to have lower self-esteem and higher rates of depression, eating disorders, and suicide). The youngest, most mature children are those at greatest risk for delinquency.

Early-maturing boys also appear to have higher rates of delinquency (Graber et al., 1997; Rutter and Smith, 1995). Generally speaking, however, boys who mature early fare better than late bloomers. Because they are taller and more muscular than their age-mates, they may be more confident, more popular, and more successful both in the classroom and on the playing field. In contrast, late-maturing boys have a poorer self-image, poorer school performance, and lower educational aspirations and expectations (Dorn et al., 1988; Litt, 1995).

- Girls from Ethnic Minority Groups may be Reaching Puberty Earlier than White Girls.

Data presented at the workshop show that for black girls, the average age of menarche is 12.1 years, compared with 12.9 years for white girls (see Brown et al., 1998). Black girls also begin pubertal development earlier than their white peers do—by 15 months. Interestingly, even though they reach menarche earlier, tempo of the pubertal development is slower. Researchers have also found that self-esteem does not follow the same developmental pattern in black and white girls. It appears that black girls' higher self-esteem may be rooted in cultural differences in attitudes toward physical appearance and obesity (Brown et al., 1998). In general, however, the factors that protect some girls and place others at risk are not well understood. It is important to note that these findings are preliminary in nature, and more research is need to further validate them, as well as determine if these differences apply to girls from other ethnic, and racial groups, such as Hispanics, American Indians, Asians, and Pacific Islanders.

- Puberty may be a Better Predictor of Aggression and Problem Behaviors than Age.

There is growing evidence to suggest that puberty rather than chronological age may signal the onset of delinquency and problem behaviors among some teenagers (Keenan and Shaw, 1997; Rutter et al., 1998). For example, early maturers—both mate and female—are more likely than other adolescents to report delinquency. Early-maturing females also appear to be at increased risk for victimization, especially sexual assault, and this may partially explain their greater likelihood of problem behaviors (Flannery et al., 1993; Raine et al., 1997). These findings suggest the need for interventions that are targeted to early-maturing adolescents who may be at increased risk for a wide range of behavior problems and associated poor developmental outcomes.

- Physical Maturation Appears to have Little Correlation with Cognitive Development.

Many developmental psychologists, most notably Jean Piaget, have documented an expanded capacity for abstract reasoning during adolescence. Today's adolescents are often capable of complex reasoning and moral judgment; their capacities frequently astonish parents and teachers. Indeed, IQ tests show an overall gain in cognitive capacities since the 1940s, when military personnel were tested in large numbers and achieved a median score of about 100. However, there appears to be little relationship between physical and cognitive maturation.

Researchers have tested the hypothesis that growth across the developmental spectrum—physical, cognitive, social, and emotional—proceeds on a similar timetable, and they have found little evidence to support this hypothesis. However, the research in this area is relatively weak, in part due to a lack of reliable, valid, easily administered instruments for assessing cognitive development (Litt, 1995). When cognitive development and capacities are not in sync with physical and sexual maturation, young people are more vulnerable; this also creates special challenges for designing and delivering age appropriate clinical interventions and services. Adults will often assume that adolescents who look older have a better grasp of the consequences of their actions.

- Brain Development Appears to Continue During Adolescence.

One of most remarkable findings in neurobiology over the last decade is the extent of change that can occur in the brain, even in the adult brain, as a function of the physical, social, and intellectual environment.

Starting in infancy and continuing into later childhood, there is a period of exuberant synapse growth followed by a period of synaptic ''pruning" which is largely completed by puberty. Although, neuroscientists have documented the time line of this synaptic waxing and waning, they are less sure about what it means for changes in childrens' and adolescents' cognitive development, behavior, intelligence, and capacity to learn. Generally, they point to correlations between changes in synaptic density or numbers and observed changes in behavior based on developmental and cognitive psychology. In coming decades, research tools such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans should greatly expand researchers' knowledge about adolescent brain development. In particular, functional imaging, if repeated over time, carries the potential for providing a better understanding of the functional connections between brain development and psychological performance (including cognitive development). New insights into brain development may also shed light on some psychopathologies and learning disabilities that affect preteens and adolescents, such as attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depressive disorders, and schizophrenia.

- Researchers are Also Providing New Insights into the Relationship Between Gender, Hormones, Brain Development, and Behavior.

In terms of the onset of puberty, boys generally follow girls by two years. For example, boys typically reach their maximum height velocity two years later than girls. In the realm of neuroscience, there is new evidence of divergent patterns of male and female brain development; these patterns have been observed between the ages of 5 and 7. Case in point: during this period, the amygdala (a part of the limbic system concerned with the expression and regulation of emotion and motivation) increases robustly in males, but not in females; the hippocampus (a part of the limbic system that plays an important role in organizing memories) increases robustly in females, but not in males. The basal ganglia are larger in females; this appears to be significant, since boys are more likely to have disorders, such as ADHD, that are associated with smaller basal ganglia. Girls may have extra protection against this type of disorder. Although there are clear differences in the path of brain development for girls and boys, it is not yet possible to look at a brain scan and determine whether the subject is male or female.

- Pregnancy During Adolescence may Alter the Physiological Development of Girls.

During pregnancy, young women at different points in pubertal development show comparable hormone profiles. Pregnancy in very young women may compromise their skeletal growth, preventing them from reaching maximum bone mass. Frank Biro noted that his research team, which followed several hundred adolescent pregnancies, found that, after giving birth, adolescent mothers were on average significantly heavier (by approximately 10 pounds) and fatter (having thicker skin folds) than their counterparts who had not given birth.

For the purposes of this discussion, stress is defined as a physical, mental, or emotional strain or tension. Stress is a normal part of everyone's life and need not be either good or bad; reactions to stress however, can vary considerably, with some reactions being unpleasant and/or undesirable.

- Cite this Page National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Adolescence; Kipke MD, editor. Adolescent Development and the Biology of Puberty: Summary of a Workshop on New Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999. Key Findings of Recent Studies.

- PDF version of this title (248K)

In this Page

Recent activity.

- Key Findings of Recent Studies - Adolescent Development and the Biology of Puber... Key Findings of Recent Studies - Adolescent Development and the Biology of Puberty

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 07 May 2024

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

- Amy Orben ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2937-4183 1 ,

- Adrian Meier ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8191-2962 2 ,

- Tim Dalgleish ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7304-2231 1 &

- Sarah-Jayne Blakemore 3 , 4

Nature Reviews Psychology ( 2024 ) Cite this article

5028 Accesses

165 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Psychiatric disorders

- Science, technology and society

Research linking social media use and adolescent mental health has produced mixed and inconsistent findings and little translational evidence, despite pressure to deliver concrete recommendations for families, schools and policymakers. At the same time, it is widely recognized that developmental changes in behaviour, cognition and neurobiology predispose adolescents to developing socio-emotional disorders. In this Review, we argue that such developmental changes would be a fruitful focus for social media research. Specifically, we review mechanisms by which social media could amplify the developmental changes that increase adolescents’ mental health vulnerability. These mechanisms include changes to behaviour, such as sharing risky content and self-presentation, and changes to cognition, such as modifications in self-concept, social comparison, responsiveness to social feedback and experiences of social exclusion. We also consider neurobiological mechanisms that heighten stress sensitivity and modify reward processing. By focusing on mechanisms by which social media might interact with developmental changes to increase mental health risks, our Review equips researchers with a toolkit of key digital affordances that enables theorizing and studying technology effects despite an ever-changing social media landscape.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent

Probing the digital exposome: associations of social media use patterns with youth mental health

Social contextual risk taking in adolescence

Introduction.

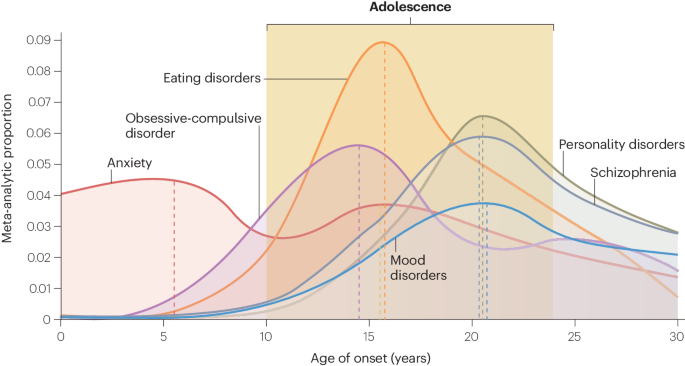

Adolescence is a period marked by profound neurobiological, behavioural and environmental changes that facilitate the transition from familial dependence to independent membership in society 1 , 2 . This critical developmental stage is also characterized by diminished well-being and increased vulnerability to the onset of mental health conditions 3 , 4 , 5 , particularly socio-emotional disorders such as depression, and eating disorders 4 , 6 (Fig. 1 ). Notable symptoms of socio-emotional disorders include heightened negative affect, mood dysregulation and an increased focus on distress or challenges concerning interpersonal relationships, including heightened sensitivity to peers or perceptions of others 6 . Although some risk factors for socio-emotional disorders do not necessarily occur in adolescence (including genetic predispositions, adverse childhood experiences and poverty 7 , 8 , 9 ), the unique developmental characteristics of this period of life can interact with pre-existing vulnerabilities, increasing the risk of disorder onset 10 .

Meta-analytic proportion of age of onset of anxiety (red), obsessive-compulsive disorder (purple), eating disorders (orange), personality disorders (green), schizophrenia (grey) and mood disorders (blue). The peak age of onset (dotted lines) is 5.5 and 15.5 years for anxiety, 14.5 years for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 15.5 years for eating disorders and 20.5 years for personality disorders, schizophrenia and mood disorders. Adapted from ref. 258 , CC BY 4.0 ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

Over the past decade, declines in adolescent mental health have become a great concern 11 , 12 . The prevalence of socio-emotional disorders has increased in the adolescent age range (10–24 years 2 ) 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , leading to mounting pressures on child and adolescent mental health services 16 , 21 , 22 . This increase has not been as pronounced among other age groups when compared with adolescents 20 , 22 , 23 (measured in ref. 20 , ref. 22 and ref. 23 as age 12–25 years, 12–20 years and 18–25 years, respectively), even if some studies have found increases across the entire lifespan 24 , 25 . Although these trends might not be generalizable across the world 26 or to subclinical indicators of distress 15 , similar trends have been found in a range of countries 27 . Declines in adolescent mental health, especially socio-emotional problems, are consistent across datasets and researchers have argued that they are not solely driven by changes in social attitudes, stigma or reporting of distress 28 , 29 .

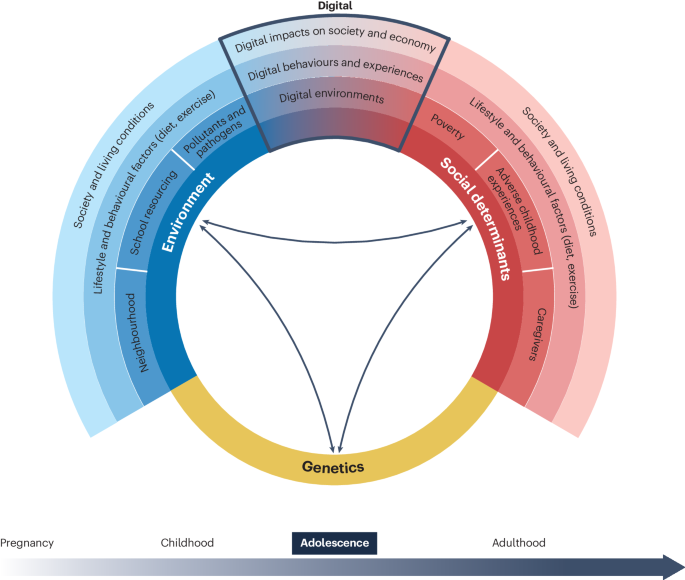

Concurrently, adolescents’ lives have become increasingly digital, with most young people using social media platforms throughout the day 30 . Ninety-five per cent of UK adolescents aged 15 years use social media 31 , and 50% of US adolescents aged 13–17 years report being almost constantly online 32 . The social media environment impacts adolescent and adult life across many domains (for example, by enabling social communication or changing the way news is accessed) and influences individuals, dyads and larger social systems 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 . Because social media is inherently social and relational 37 , it potentially overlaps and interacts with the developmental changes that make adolescents vulnerable to the onset of mental health problems 38 , 39 (Fig. 2 ). Thus, it has been intensely debated whether the increase in social media use during the past decade has a causal role in the decline of adolescent mental health 40 . Indeed, rapid changes to the environment experienced before and during adolescence might be a fruitful area to explore when examining current mental health trends 41 .

During adolescence, the interaction between genetic programming (yellow), social determinants (red) and environmental factors (blue), as well as the developmental changes discussed in this Review, increases the risk for onset of mental health conditions. Digital environments, mediated behaviours and experiences, and the impact that this technology has on society and economy more generally, are one aspect of the complex forces that might lead to the declines in adolescent mental health observed in the last decade. Adapted from ref. 259 , Springer Nature Limited.

Although there are many environmental changes that could be relevant, a substantial body of research has emerged to investigate the potential link between social media use and declines in adolescent mental health 42 , 43 using various research approaches, including cross-sectional studies 44 , longitudinal observational data analyses 45 , 46 , 47 and experimental studies 48 , 49 . However, the scientific results have been mixed and inconclusive (for reviews, see refs. 43 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ), which has made it difficult to establish evidence-based recommendations, regulations and interventions aimed at ensuring that social media use is not harmful to adolescents 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 .

Many researchers attribute the mixed results to insufficient study specificity. For instance, the relationship between social media use and mental health varies notably across individuals 45 , 58 and developmental time windows 59 . Yet studies often examine adolescents without differentiating them based on age or developmental stage 60 , which prevents systematic accounts of individual and subgroup differences. Additionally, most studies only rely on self-reported measures of time spent on social media 61 , 62 , and overlook more nuanced aspects of social media use such as the nature of the activities 63 and the content or features that users engage with 52 . These factors need to be considered to unpack any broader relationships 35 , 64 , 65 , 66 . Furthermore, the measurement of mental health often conflates positive and negative mental health outcomes as well as various mental health conditions, which could all be differentially related to social media use 52 , 67 .

This research space presents substantial complexity 68 . There is an ever-increasing range of potential combinations of social media predictors, well-being and mental health outcomes and participant groups of varying backgrounds and demographics that can become the target of scientific investigation. However, the pressure to deliver policy and public-facing recommendations and interventions leaves little time to investigate comprehensively each of these combinations. Researchers need to be able to pinpoint quickly the research programmes with the maximum potential to create translational and real-world impact for adolescent mental health.

In this Review, we aim to delineate potential avenues for future research that could lead to concrete interventions to improve adolescent mental health by considering mechanisms at the nexus between pre-existing processes known to increase adolescent mental health vulnerability and digital affordances introduced by social media. First, we describe the affordance approach to understanding the effects of social media. We then draw upon research on adolescent development, mental health and social media to describe behavioural, cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms by which social media use might amplify changes during adolescent development to increase mental health vulnerability during this period of life. The specific mechanisms within each category were chosen because they have a strong evidence base showing that they undergo substantive changes during adolescent development, are implicated in mental health risk and can be modulated by social media affordances. Although the ways in which social media can also improve mental health resilience are not the focus of our Review and therefore are not reviewed fully here, they are briefly discussed in relation to each mechanism. Finally, we discuss future research focused on how to systematically test the intersection between social media and adolescent mental health.

Social media affordances

To study the impact of social media on adolescent mental health, its diverse design elements and highly individualized uses must be conceptualized. Initial research predominately related access to or time spent on social media to mental health outcomes 46 , 69 , 70 . However, social media is not similar to a toxin or nutrient for which each exposure dose has a defined link to a health-related outcome (dose–response relationship) 56 . Social media is a diverse environment that cannot be summarized by the amount of time one spends interacting with it 71 , 72 , and individual experiences are highly varied 45 .

Previous psychological reviews often focused on social media ‘features’ 73 and ‘affordances’ 74 interchangeably. However, these terms have distinct definitions in communication science and information systems research. Social media features are components of the technology intentionally designed to enable users to perform specific actions, such as liking, reposting or uploading a story 75 , 76 . By contrast, affordances describe the perceptions of action possibilities users have when engaging with social media and its features, such as anonymity (the difficulty with which social media users can identify the source of a message) and quantifiability (how countable information is).

The term ‘affordance’ came from ecological psychology and visuomotor research, and was described as mainly determined by human perception 77 . ‘Affordance’ was later adopted for design and human–computer interaction contexts to refer to the action possibilities that are suggested to the user by the technology design 78 . Communication research synthesizes both views. Affordances are now typically understood as the perceived — and therefore flexible — action possibilities of digital environments, which are jointly shaped by the technology’s features and users’ idiosyncratic perceptions of those features 79 .

Latent action possibilities can vary across different users, uses and technologies 79 . For example, ‘stories’ are a feature of Instagram designed to share content between users. Stories can also be described in terms of affordances when users perceive them as a way to determine how long their content remains available on the platform (persistence) or who can see that content (visibility) 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 . Low persistence (also termed ephemerality) and comparatively low visibility can be achieved through a technology feature (Instagram stories), but are not an outcome of technology use itself; they are instead perceived action possibilities that can vary across different technologies, users and designs 79 .

The affordances approach is particularly valuable for theorizing at a level above individual social media apps or specific features, which makes this approach more resilient to technological changes or shifts in platform popularity 79 , 85 . However, the affordances approach can also be related back to specific types of social media by assessing the extent to which certain affordances are ‘built into’ a particular platform through feature design 35 . Furthermore, because affordances depend on individuals’ perceptions and actions, they are more aligned than features with a neurocognitive and behavioural perspective to social media use. Affordances, similar to neurocognitive and behavioural research, emphasize the role of the user (how the technology is perceived, interpreted and used) rather than technology design per se. In this sense, the affordances approach is essential to overcome technological determinism of mental health outcomes, which overly emphasizes the role of technology as the driver of outcomes but overlooks the agency and impact of the people in question 86 . This flexibility and alignment with psychological theory has contributed to the increasing popularity of the affordance approach 35 , 73 , 74 , 85 , 87 and previous reviews have explored relevant social media affordances in the context of interpersonal communication among adults and adolescents 35 , 88 , 89 , adolescent body image concerns 73 and work contexts 33 . Here, we focus on the affordances of social media that are relevant for adolescent development and its intersection with mental health (Table 1 ).

Behavioural mechanisms

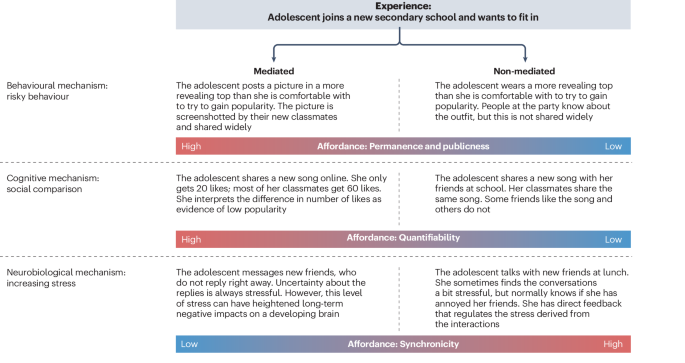

Adolescents often use social media differently to adults, engaging with different platforms and features and, potentially, perceiving or making use of affordances in distinctive ways 35 . These usage differences might interact with developmental characteristics and changes to amplify mental health vulnerability (Fig. 3 ). We examine two behavioural mechanisms that might govern the impact of social media use on mental health: risky posting behaviours and self-presentation.

Social media affordances can amplify the impact that common adolescent developmental mechanisms (behavioural, cognitive and neurobiological) have on mental health. At the behavioural level (top), affordances such as permanence and publicness lead to an increased impact of risk-taking behaviour on mental health compared with similar behaviours in non-mediated environments. At the cognitive level (middle), high quantifiability influences the effects of social comparison. At the neurobiological level (bottom), low synchronicity can amplify the effects of stress on the developing brain.

Risky posting behaviour

Sensation-seeking peaks in adolescence and self-regulation abilities are still not fully developed in this period of life 90 . Thus, adolescents often engage in more risky behaviours than other age groups 91 . Adolescents are more likely to take risks in situations involving peers 92 , 93 , perhaps because they are motivated to avoid social exclusion 94 , 95 . Whether adolescent risk-taking behaviour is inherently adaptive or maladaptive is debated. Although some risk-taking behaviours can be adaptive and part of typical development, others can increase mental health vulnerability. For example, data from a prospective UK panel study of more than 5,500 young people showed that engaging in more risky behaviours (including social and health risks) at age 16 years increases the odds of a range of adverse outcomes at age 18 years, such as depression, anxiety and substance abuse 96 .

Social media can increase adolescents’ engagement in risky behaviours both in non-mediated and mediated environments (environments in which the behaviour is executed in or through a technology, such as a mobile phone and social media). First, affordances such as quantifiability in conjunction with visibility and association (the degree with which links between people, between people and content or between a presenter and their audience can be articulated) can promote more risky behaviours in non-mediated environments and in-person social interactions. For example, posts from university students containing references to alcohol gain more likes than posts not referencing alcohol and liking such posts predicts an individual’s subsequent drinking habits 97 . Users expecting likes from their audience are incentivized to engage in riskier posting behaviour (such as more frequent or more extreme posts containing references to alcohol). The relationship between risky online behaviour and offline behaviour is supported by meta-analyses that found a positive correlation between adolescents’ social media use and their engagement in behaviours that might expose them to harm or risk of injury (for example, substance use or risky sexual behaviours) 98 . Further, affordances such as persistence and visibility can mean that risky behaviours in mediated and non-mediated environments remain public for long periods of time, potentially influencing how an adolescent is perceived by peers over the longer term 39 , 99 .

Adolescence can also be a time of more risky social media use. For most forms of semi-public and public social media use, users typically do not know who exactly will be able to see their posts. Thus, adolescents need to self-present to an ‘imagined audience’ 100 and avoid posting the wrong kind of content as the boundaries between different social spheres collapse (context collapse 101 ). However, young people can underestimate the risks of disclosing revealing information in a social media environment 102 . Affordances such as visibility, replicability (social media posts remain in the system and can be screenshotted and shared even if they are later deleted 39 ), association and persistence could heighten the risk of experiencing cyberbullying, victimization and online harassment 103 . For example, adolescents can forward privately received sexual images to larger friendship groups, increasing the risk of online harassment over the subject of the sexual images 104 . Further, low bandwidth (a relative lack of socio-emotional cues) and high anonymity have the potential to disinhibit interactions between users and make behaviours and reactions more extreme 105 , 106 . For example, anonymity was associated with more trolling behaviours during an online group discussion in an experiment with 242 undergraduate students 107 .

Thus, social media might drive more risky behaviours in both mediated and non-mediated contexts, increasing mental health vulnerability. However, the evidence is still not clear cut and often discounts adolescent agency and understanding. For example, mixed-methods research has shown that young people often understand the risks of posting private or sexual content and use social media apps that ensure that posts are deleted and inaccessible after short periods of time to counteract them 39 (even though posts can still be captured in the meantime). Future work will therefore need to investigate how adolescents understand and balance such risks and how such processes relate to social media’s impact on mental health.

Self-presentation and identity

The adolescent period is characterized by an abundance of self-presentation activities on social media 74 , where the drive to present oneself becomes a fundamental motivation for engagement 108 . These activities include disclosing, concealing and modifying one’s true self, and might involve deception, to convey a desired impression to an audience 109 . Compared with adults, adolescents more frequently take part in self-presentation 102 , which can encompass both realistic and idealized portrayals of themselves 110 . In adults, authentic self-presentation has been associated with increased well-being, and inauthentic presentation (such as when a person describes themselves in ways not aligned with their true self) has been associated with decreased well-being 111 , 112 , 113 .

Several social media affordances shape the self-presentation behaviours of adolescents. For example, the editability of social media profiles enables users to curate their online identity 84 , 114 . Editability is further enhanced by highly visible (public) self-presentations. Additionally, the constant availability of social media platforms enables adolescents to access and engage with their profiles at any time, and provides them with rapid quantitative feedback about their popularity among peers 89 , 115 . People receive more direct and public feedback on their self-presentation on social media than in other types of environment 116 , 117 . The affordances associated with self-presentation can have a particular impact during adolescence, a period characterized by identity development and exploration.

Social media environments might provide more opportunities than offline environments for shaping one’s identity. Indeed, public self-presentation has been found to invoke more prominent identity shifts (substantial changes in identity) compared with private self-presentation 118 , 119 . Concerns have been raised that higher Internet use is associated with decreased self-concept clarity. Only one study of 101 adolescents as well as adults reviewed in a 2021 meta-analysis 120 showed that the intensity of Facebook use (measured by the Facebook Intensity Scale) predicted a longitudinal decline in self-concept clarity 3 months later, but the converse was not the case and changes in self-concept clarity did not predict Facebook use 121 . This result is still not enough to show a causal relationship 121 . Further, the affordances of persistence and replicability could also curtail adolescents’ ability to explore their identity freely 122 .

By contrast, qualitative research has highlighted that social media enables adolescents to broaden their horizons, explore their identity and identify and reaffirm their values 123 . Social media can help self-presentation by enabling adolescents to elaborate on various aspects of their identity, such as ethnicity and race 124 or sexuality 125 . Social media affordances such as editability and visibility can also facilitate this process. Adolescents can modify and curate self-presentations online, try out new identities or express previously undisclosed aspects of their identity 126 , 127 . They can leverage social media affordances to present different facets of themselves to various social groups by using different profiles, platforms and self-censorship and curation of posts 128 , 129 . Presenting and exploring different aspects of one’s identity can have mental health implications for minority teens. Emerging research shows a positive correlation between well-being and problematic Internet use in transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse adolescents (age 13–18 years), and positive sentiment has been associated with online identity disclosures in transgender individuals with supportive networks (both adolescent and adult) 130 , 131 .

Cognitive mechanisms

Adolescents and adults might experience different socio-cognitive impacts from the same social media activity. In this section, we review four cognitive mechanisms via which social media and its affordances might influence the link between adolescent development and mental health vulnerabilities (Fig. 3 ). These mechanisms (self-concept development, social comparison, social feedback and exclusion) roughly align with a previous review that examined self-esteem and social media use 115 .

Self-concept development

Self-concept refers to a person’s beliefs and evaluations about their own qualities and traits 132 , which first develops and becomes more complex throughout childhood and then accelerates its development during adolescence 133 , 134 , 135 . Self-concept is shaped by socio-emotional processes such as self-appraisal and social feedback 134 . A negative and unstable self-concept has been associated with negative mental health outcomes 136 , 137 .

Perspective-taking abilities also develop during adolescence 133 , 138 , 139 , as does the processing of self-relevant stimuli (measured by self-referential memory tasks, which assess memory for self-referential trait adjectives 140 , 141 ). During adolescence, direct self-evaluations and reflected self-evaluations (how someone thinks others evaluate them) become more similar. Further, self-evaluations have a distinct positive bias during childhood, but this positivity bias decreases in adolescence as evaluations of the self are integrated with judgements of other people’s perspectives 142 . Indeed, negative self-evaluations peak in late adolescence (around age 19 years) 140 .

The impact of social media on the development of self-concept could be heightened during adolescence because of affordances such as personalization of content 143 (the degree to which content can be tailored to fit the identity, preferences or expectations of the receiver), which adapts the information young people are exposed to. Other affordances with similar impacts are quantifiability, availability (the accessibility of the technology as well as the user’s accessibility through the technology) and public visibility of interactions 89 , which render the evaluations of others more prominent and omnipresent. The prominence of social evaluation can pose long-term risks to mental health under certain conditions and for some users 144 , 145 . For example, receiving negative evaluations from others or being exposed to cyberbullying behaviours 146 , 147 can, potentially, have heightened impact at times of self-concept development.

A pioneering cross-sectional study of 150 adolescents showed that direct self-evaluations are more similar to reflected self-evaluations, and self-evaluations are more negative, in adolescents aged 11–21 years who estimate spending more time on social media 148 . Further, longitudinal data have shown bidirectional negative links between social media use and satisfaction with domains of the self (such as satisfaction with family, friends or schoolwork) 47 .

Although large-scale evidence is still unavailable, these findings raise the interesting prospect that social media might have a negative influence on perspective-taking and self-concept. There is less evidence for the potential positive influence of social media on these aspects of adolescent development, demonstrating an important research gap. Some researchers hypothesize that social media enables self-concept unification because it provides ample opportunity to find validation 89 . Research has also discussed how algorithmic curation of personalized social media feeds (for example, TikTok algorithms tailoring videos viewed to the user’s interests) enables users to reflect on their self-concept by being exposed to others’ experiences and perspectives 143 , an area where future research can provide important insights.

Social comparison

Social comparison (thinking about information about other people in relation to the self 149 ) also influences self-concept development and becomes particularly important during adolescence 133 , 150 . There are a range of social media affordances that can amplify the impact of social comparison on mental health. For example, quantifiability enables like or follower counts to be easily compared with others as a sign of status, which facilitates social ranking 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 . Studies of older adolescents and adults aged, on average, 20 years have also found that the number of likes or reactions received predict, in part, how successful users judge their self-presentation posts on Facebook 155 . Furthermore, personalization enables the content that users see on social media to be curated so as to be highly relevant and interesting for them, which should intensify comparisons. For example, an adolescent interested in sports and fitness content will receive personalized recommendations fitting those interests, which should increase the likelihood of comparisons with people portrayed in this content. In turn, the affordance of association can help adolescents surround themselves with similar peers and public personae online, enhancing social comparison effects 63 , 156 . Being able to edit posts (via the affordance of editability) has been argued to contribute to the positivity bias on social media: what is portrayed online is often more positive than the offline experience. Thus, upward comparisons are more likely to happen in online spaces than downward or lateral comparisons 157 . Lastly, the verifiability of others’ idealized self-presentations is often low, meaning that users have insufficient cues to gauge their authenticity 158 .

Engaging in comparisons on social media has been associated with depression in correlational studies 159 . Furthermore, qualitative research has shown that not receiving as many positive evaluations as expected (or if positive evaluations are not provided quickly enough) increases negative emotions in children and adolescents aged between age 9 and 19 years 39 . This result aligns with a reinforcement learning modelling study of Instagram data, which found that the likes a user receives on their own posts become less valuable and less predictive of future posting behaviour if others in their network receive more likes on their posts 160 . Although this study did not measure mood or mental health, it shows that the value of the likes are not static but inherently social; their impact depends on how many are typically received by other people in the same network.

Among the different types of social comparison that adolescents engage in (comparing one’s achievements, social status or lifestyle), the most substantial concerns have been raised about body-related comparisons. One review suggested that social media affordances create a ‘perfect storm’ for body image concerns that can contribute to both socio-emotional and eating disorders 73 . Social media affordances might increase young people’s focus on other people’s appearances as well as on their own appearance by showing idealized, highly edited images, providing quantified feedback and making the ability to associate and compare oneself with peers constantly available 161 , 162 . The latter puts adolescents who are less popular or receive less social support at particular risk of low self-image and social distress 35 .

Affordances enable more prominent and explicit social comparisons in social media environments relative to offline environments 158 , 159 , 163 , 164 , 165 . However, this association could have a positive impact on mental health 164 , 166 . Initial evidence suggests beneficial outcomes of upward comparisons on social media, which can motivate behaviour change and yield positive downstream effects on mental health 164 , 166 . Positive motivational effects (inspiration) have been observed among young adults for topics such as travelling and exploring nature, as well as fitness and other health behaviours, which can all improve mental health 167 . Importantly, inspiration experiences are not a niche phenomenon on social media: an experience sampling study of 353 Dutch adolescents (mean age 13–15 years) found that participants reported some level of social media-induced inspiration in 33% of the times they were asked to report on this over the course of 3 weeks 168 . Several experimental and longitudinal studies show that inspiration is linked to upward comparison on social media 157 , 164 , 166 . However, the positive, motivating side of social comparison on social media has only been examined in a few studies and requires additional investigation.

Social feedback

Adolescence is also a period of social reorientation, when peers tend to become more important than family 169 , peer acceptance becomes increasingly relevant 170 , 171 , 172 and young people spend increasing amounts of time with peers 173 . In parallel, there is a heightened sensitivity to negative socio-emotional or self-referential cues 140 , 174 , higher expectation of being rejected by others 175 and internalization of such rejection 142 , 176 compared with other phases in life development. A meta-analysis of both adolescents and adults found that oversensitivity to social rejection is moderately associated with both depression and anxiety 177 .

Social media affordances might amplify the potential impact of social feedback on mental health. Wanting to be accepted by peers and increased susceptibility to social rewards could be a motivator for using social media in the first place 178 . Indeed, receiving likes as social reward activated areas of the brain (such as the nucleus accumbens) that are also activated by monetary reward 179 . Quantifiability amplifies peer acceptance and rejection (via like counts), and social rejection has been linked to adverse mental health outcomes 170 , 180 , 181 , 182 . Social media can also increase feelings of being evaluated, the risk of social rejection and rumination about potential rejection due to affordances such as quantifiability, synchronicity (the degree to which an interaction happens in real time) and variability of social rewards (the degree to which social interaction and feedback occur on variable time schedules). For example, one study of undergraduate students found that active communication such as messaging was associated with feeling better after Facebook use; however, this was not the case if the communication led to negative feelings such as rumination (for example, after no responses to the messages) 183 .

In a study assessing threatened social evaluation online 184 , participants were asked to record a statement about themselves and were told their statements would be rated by others. To increase the authenticity of the threat, participants were asked to rate other people’s recordings. Threatened social evaluation online in this study decreased mood, most prominently in people with high sensitivity to social rejection. Adolescents who are more sensitive to social rejection report more severe depressive symptoms and maladaptive ruminative brooding in both mediated and non-mediated social environments, and this association is most prominent in early adolescence 185 . Not receiving as much online social approval as peers led to more severe depressive symptoms in a study of American ninth-grade adolescents (between age 14 and 15 years), especially those who were already experiencing peer victimization 153 . Furthermore, individuals with lower self-esteem post more negative and less positive content than individuals with higher self-esteem. Posted negative content receives less social reward and recognition from others than positive content, possibly creating a vicious cycle 186 . Negative experiences pertaining to social exclusion and status are also risk factors for socio-emotional disorders 180 .

The impact of social media experiences on self-esteem can be very heterogeneous, varying substantially across individuals. As a benefit, positive social feedback obtained via social media can increase users’ self-esteem 115 , an association also found among adolescents 187 . For instance, receiving likes on one’s profile or posted photographs can bolster self-esteem in the short term 144 , 188 . A study linking behavioural data and self-reports from Facebook users found that receiving quick responses on public posts increased a sense of social support and decreased loneliness 189 . Furthermore, a review of reviews consistently documented that users who report more social media use also perceive themselves to have more social resources and support online 52 , although this association has mostly been studied among young adults using social network sites such as Facebook. Whether such social feedback benefits extend to adolescents’ use of platforms centred on content consumption (such as TikTok or Instagram) is an open question.

Social inclusion and exclusion

Adolescents are more sensitive to the negative emotional impacts of being excluded than are adults 170 , 190 . It has been proposed that, as the importance of social affiliation increases during this period of life 134 , 191 , 192 , adolescents are more sensitive to a range of social stimuli, regardless of valence 193 . These include social feedback (such as compliments or likes) 95 , 194 , negative socio-emotional cues (such as negative facial expressions or social exclusion) 174 and social rejection 172 , 185 . By contrast, social inclusion (via friendships in adolescence) is protective against emotional disorders 195 and more social support is related to higher adolescent well-being 196 .

Experiencing ostracism and exclusion online decreases self-esteem and positive emotion 197 . This association has been found in vignette experiments where participants received no, only a few or a lot of likes 198 , or experiments that used mock-ups of social media sites where others received more likes than participants 153 . Being ostracized (not receiving attention or feedback) or rejected through social media features (receiving dislikes and no likes) is also associated with a reduced sense of belonging, meaningfulness, self-esteem and control 199 . Similar results were found when ostracism was experienced over messaging apps, such as not receiving a reply via WhatsApp 200 .

Evidence on whether social media also enables adolescents to experience positive social inclusion is mostly indirect and mixed. Some longitudinal surveys have found that prosocial feedback received on social media during major life events (such as university admissions) helps to buffer against stress 201 . Adult participants of a longitudinal study reported that social media offered more informational support than offline contexts, but offline contexts more often offered emotional or instrumental support 202 . Higher social network site use is, on average, associated with a perception of having more social resources and support in adults (for an overview of meta-analyses, see ref. 52 ). However, most of these studies have not investigated social support among adolescents, and it is unclear whether early findings (for example, on Facebook or Twitter) generalize to a social media landscape more strongly characterized by content consumption than social interaction (such as Instagram or TikTok).

Still, a review of social media use and offline interpersonal outcomes among adolescents documents both positive (sense of belonging and social capital) and negative (alienation from peers and perceived isolation) correlates 203 . Experience sampling research on emotional support among young adults has further shown that online social support is received and perceived as effective, and its perceived effectiveness is similar to in-person social support 204 . Social media use also has complex associations with friendship closeness among adolescents. For example, one experience sampling study found that greater use of WhatsApp or Instagram is associated with higher friendship closeness among adolescents; however, within-person examinations over time showed small negative associations 205 .

Neurobiological mechanisms

The long-term impact of environmental changes such as social media use on mental health might be amplified because adolescence is a period of considerable neurobiological development 95 (Fig. 3 ). During adolescence, overall cortical grey matter declines and white matter increases 206 , 207 . Development is particularly protracted in brain regions associated with social cognition and executive functions such as planning, decision-making and inhibiting prepotent responses. The changes in grey and white matter are thought to reflect axonal growth, myelination and synaptic reorganization, which are mechanisms of neuroplasticity influenced by the environment 208 . For example, research in rodents has demonstrated that adolescence is a sensitive period for social input, and that social isolation in adolescence has unique and more deleterious consequences for neural, behavioural and mental health development than social isolation before puberty or in adulthood 206 , 209 . There is evidence that brain regions involved in motivation and reward show greater activation to rewarding and motivational stimuli (such as appetitive stimuli and the presence of peers) in early and/or mid adolescence compared with other age groups 210 , 211 , 212 , 213 , 214 .