- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

21 Business Model Innovation

Lorenzo Massa, Researcher, University of Bologna and Vienna University of Economics and Business.

Christopher L. Tucci is Associate Professor of Management of Technology at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), where he holds the Chair in Corporate Strategy & Innovation. Prior to joining EPFL, he was on the faculty of the NYU Stern School of Business. He is interested in technological change and how waves of technological changes affect incumbent firms. For example, he is studying how the technological changes brought about by the popularization of the Internet affect firms in different industries. He has published articles in Management Science, Strategic Management Journal, Research Policy, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, and Journal of Product Innovation Management. In 2003, he was elected to the leadership track for the Technology & Innovation Management Division of the Academy of Management.

- Published: 01 October 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter offers a broad review of the literature at the nexus between Business Models and innovation studies and examines the notion of Business Model Innovation in three different situations: Business Model Design in newly formed organizations, Business Model Reconfiguration in incumbent firms, and Business Model Innovation in the broad context of sustainability. Tools and perspectives to make sense of Business Models and support managers and entrepreneurs in dealing with Business Model Innovation are reviewed and organized around a synthesizing meta-framework. The framework elucidates the nature of the complementarities across various perspectives. Finally, the use of business model-related ideas in practice is discussed, and critical managerial challenges as they relate to Business Model Innovation and managing business models are identified and examined.

Introduction

In the past fifteen years, the business model (BM) has become an increasingly important unit of analysis in innovation studies. Within this field, a consensus is emerging that the role of the BM in fostering innovation is twofold. First, by allowing managers and entrepreneurs to connect innovative products and technologies to a realized output in a market, the BM represents an important vehicle for innovation. Second, the BM may be also a source of innovation in and of itself . It represents a new dimension of innovation, distinct, albeit complementary, to traditional dimensions of innovation, such as product, process or organizational.

This chapter serves to introduce the notion of Business Model Innovation (BMI) and has four main objectives, to: (1) clarify the origins and notion of the BM; (2) organize the literature on BMI around emerging literature streams; (3) offer an overview of the various tools that have been proposed in supporting managers and entrepreneurs in dealing with BMI; and (4) offer a discussion of the principal managerial challenges related to managing BMs and BMI.

As a starting point, we seek to introduce and clarify the notion of the BM. We review the received literature, highlight the origins of the BM and clarify the nature of the construct. Next, we introduce the notion of BMI and define it as the activity of designing—that is, creating, implementing and validating—a new BM and suggest that the process of BMI differs if an existing BM is already in place vis-à-vis when it is not. Accordingly, for analytical purposes, we distinguish between BM design in newly formed organizations, and BM reconfiguration in incumbent firms. We note that these literatures tend to focus on the antecedents and mechanisms at the background of BMI. We suggest that a new literature is emerging focusing on the consequences of BMI, and pointing to the role of BMI in unlocking the private sector potential to contribute to solving environmental and social issues. We offer a review. Finally, we analyse various tools and perspectives that seek to make sense of the BM and support BMI and business modelling (the set of activities supporting BM representation, sense-making and strategic planning for BMI). We highlight the complementary nature of different perspectives and organize them in a conceptual meta-framework. In doing so, we also provide evidence of the current use of BM-related ideas in practice. We conclude with a discussion of some of most salient managerial challenges related to managing BMs and BMI.

What is a Business Model? Definition and Emergence of the Concept

In the past several years, interest in the concept of BMs has virtually exploded, attracting the attention of managers and academics alike. Zott and colleagues ( Zott, Amit, and Massa, 2011 ) searched for the use of the term business model in general management articles and noted a dramatic increase in the incidence of the term in the fifteen-year period between 1995 and 2010, in parallel with the popularization and broad diffusion of the Internet.

Teece (2010) notes that BMs have been an integral part of economic behaviour since pre-classical times. Indeed, firms have always operated according to a business model but, until the mid 1990s, firms traditionally operated following similar logics, typical of the industrial firm, in which a product/service—typically produced by the firm (and its suppliers)—is delivered to a customer from which revenues are collected. Even if instances of firms and organizations adopting innovative BMs have been recognized in business history (cf. Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010 ), it is only recently that the scale and speed at which innovative BMs are transforming industries and, indirectly, civil society, has attracted the attention of scholars and practitioners. Thus, BMs seek to make sense of these novel forms of ‘doing business’. According to Magretta (2002) , the BM is a story that answers Peter Drucker’s age old questions: (1) who is the customer, (2) what does the customer value, (3) how do we make money in this business, (4) and what is the economic logic that explains how we can deliver value to customers at an appropriate cost? The emergence of novel logics employed by firms in doing business as they go to market has increasingly popularized the notion of BM.

Several scholars agree that the Internet, together with related advances in information and communication technologies (ICTs), acted as catalysis for BM experimentation and innovation (e.g, Timmers, 1998; Amit and Zott, 2001 ; Afuah and Tucci, 2001 ), opening up new opportunities for organizing business activities. Entire industrial sectors have evolved along radically new trajectories of innovation and offered new logics of value creation not seen in recent business history.

Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010) have observed that two other phenomena have been accompanied by considerable innovation in the way firms ‘do business’. These are: (1) the advent of post-industrial technologies ( Perkmann and Spicer, 2010 ), and (2) efforts by the corporate sector to enter new markets in developing or underdeveloped countries and reach customers at the Bottom of the Pyramid 1 (BoP) ( Prahalad and Hart, 2002 ; Prahalad, 2005 ). A third one, related to BoP, is represented by ‘sustainability’. Let us discuss each of these in turn.

Scientific and technological advances in so-called post-industrial technologies (e.g., software or biotechnology) have been accompanied by a surge of organizational architectures and governance structures which radically differ from those observed in traditional manufacturing organizations (e.g., Bonaccorsi, Giannangeli, and Rossi, 2006 ). Firms, for example, have emerged that host and maintain IT applications across the Internet, offering software as a service (rather than a product: Susarla, Barua, and Whinston, 2009 ). The Open Source software movement has been accompanied by the emergence of new governance structures ( Bonaccorsi et al., 2006 ) and novel forms of collaborative entrepreneurship ( Miles, Miles, and Snow, 2006 ). Similarly, the biotechnology sector has been the locus of considerable BMI (e.g., Pisano, 2006 ), with firms emerging that focus on specific tasks and relative services along the product development value chain ( Konde, 2009 ). Innovative BMs are observed in other sectors as well. Firms such as ARM (semiconductors), Dolby (sound systems), CDT (electronic displays) or Plastic Logic (plastic materials) all have specialized in the management of intellectual property and operate in the ‘market for ideas’ (see chapter 12 by Gambardella, Giuri, and Torrisi) by licensing the rights of their innovative technologies and solutions rather than commercializing the products themselves. Whether post-industrial technologies can be properly considered an antecedent of BM innovation vis-à-vis other explanations such as the intellectual property revolution ( Pisano, 2006 ), the disintegration of the value chain observed in many industries, or the institutionalization of Open Innovation as a way to organize innovation activities outside the traditional boundaries of the firm (see chapter 22 by Alexy and Dahlander), remains an unexplored research question. Certainly, however, post-industrial technologies have been accompanied by the emergence of novel ways to conduct business.

Opportunities to address economic needs at the BoP in emerging markets ( Ricart, Enright, Ghemawat, Hart, and Khanna, 2004 ) have also pointed researchers and practitioners towards the systematic study of BMs. The core argument in the BoP literature is that the vast, untapped market of the world’s poor represents a large opportunity for companies to both serve customers and make a profit. However, business opportunities at the BoP challenge conventional ways of doing business. Due to the fundamentally different social, economic, and cultural environments that characterize emerging markets, companies are urged to rethink every step in their supply chain and develop novel BMs ( Prahalad and Hart, 2002 ). In addition, existing models may have limited applicability and need to be adapted ( Seelos and Mair, 2007 ). Chesbrough, Ahern, Finn, and Guerraz (2006) , studying product deployment in the developing world, highlight that while the ‘right’ product design is a necessary condition for penetrating low income markets, those companies that ultimately succeed in generating commercially sustainable operations are those that put in place the right BM. These BMs play a crucial role in creating key elements, such as distribution channels, supplies and sales channels necessary for the successful execution of business transactions. Thus, enterprises that aim at reaching the BoP constitute an important source of BM innovation ( Prahalad, 2005 ).

While the study of BMs has traditionally focused on business activities, the emergence of new organizational architectures designed for purposes other than economic profits, such as solving social problems and sustainability issues, has started to attract the attention of scholars studying BMs ( Seelos and Mair, 2007 ; Yunus, Moingeon and Lehmann-Ortega, 2010 ). For example, Nobel laureate Mohamed Yunus has been pioneering the concept of microfinance and designed a novel organization, the Grameen Bank, whose main purpose is the eradication of poverty (cf. Yunus et al., 2010 ), a critical issue in the discussion on sustainability (cf. WCED, 1987 ). Scholars increasingly employ the term BM in referring to the way such organizations operate and in capturing instances of value creation whose nature is not necessarily economic (see chapter 16 by Lawrence et al.).

To conclude this section, the BM is an elusive concept allowing for considerable interpretative flexibility ( Bijker, Hughes, and Pinch, 1987 ). Zott et al. (2011) have recently reviewed the most recent literature on the topic and noted that various conceptualizations of the BM exist that often serve the scope of the particular phenomenon of interest to the researcher. There are, however, some emerging common themes that act as a common denominator among the various conceptualizations of the BM that have been provided. In particular scholars seem to recognize—explicitly or implicitly—that the BM is a ‘system level concept, centered on activities and focusing on value’ (2011: 1037). It emphasizes a systemic and holistic understanding of how an organization orchestrates its system of activities for value creation. In addition, they noted that the phenomenon of value creation as depicted by the BM typically occurs in a value network (cf. Normann and Ramirez, 1993 ; Parolini, 1999 ), which can include suppliers, partners, distribution channels, and coalitions that extend the company’s resources. Therefore they suggest that the BM also introduces a new unit of analysis in addition to the product, firm, industry, or network levels. Such a new unit of analysis is nested between the firm and its network of exchange partners.

These considerations suggest that, at first glance, the BM may be conceptualized as depicting the rationale of how an organization (a firm or other type of organization) creates, delivers, and captures value (economic, social, or other forms of value) in relationship with a network of exchange partners ( Afuah and Tucci, 2001 ; Osterwalder, Pigneur, and Tucci, 2005 ; Zott et al., 2011 ). This broad definition is elastic with respect to the nature of the value created, and serves the scope of introducing the topic of BMI.

Business Models and Innovation

The literature at the intersection of the BM concept and the domain of innovation has advanced two complementary roles for the BM in fostering innovation. First, BMs allow innovative companies to commercialize new ideas and technologies. Second, firms can also view the BM as a source of innovation in and of itself, and as a source of competitive advantage.

The first view is mainly rooted in the literature on technology management and entrepreneurship. It is recognized that innovative technologies or ideas per se have no economic value. It is through the design of appropriate BMs that managers and entrepreneurs may be able to unlock the output from investments in R&D and connect it to a market. By allowing the commercialization of novel technologies and ideas, the BM becomes a vehicle for innovation. Xerox invented the first photocopy machine, but the technology was too expensive and could not be sold. Managers at Xerox solved the problem by leasing the machine, inventing a new BM for doing so. In this view, the BM is a manipulable device that mediates between technology and economic value creation ( Chesbrough and Rosenbloom, 2002 ).

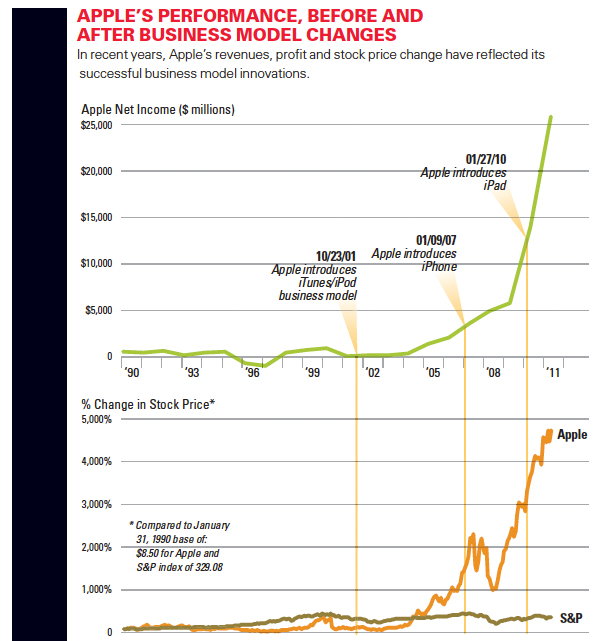

The second view is that the BM represents a new dimension of innovation itself, which spans the traditional modes of process, product, and organizational innovation. This new dimension of innovation may be source of superior performance, even in mature industries ( Zott and Amit, 2007 ). Dell in the computer industry, Southwest in the airline industry, or Apple with iPod and iTunes in the music industry, just to mention a few known cases, secured impressive growth rates and outperformed the competition by establishing innovative BMs.

This suggests that firms can compete through their BMs ( Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2007 ). Novel BMs may be a source of disruption ( Christensen, 1997 ), changing the logic of entire industries and replacing the old way of doing things to become the standard for the next generation of entrepreneurs to beat ( Magretta, 2002 ). According to Chesbrough, BMI may have more important strategic implications than other forms of innovation, in that ‘a better BM will beat a better idea or technology’ (2007: 12).

Building on the literature at the nexus between BMs and innovation, we propose that BMI may refer to (1) the design of novel BMs for newly formed organizations, or (2) the reconfiguration of existing BMs. We refer to the first phenomena by employing the term business model design (BMD) , which refers to the entrepreneurial activity of creating, implementing and validating a BM for a newly formed organization. We use the term business model reconfiguration (BMR) to capture the phenomenon by which managers reconfigure organizational resources (and acquire new ones) to change an existing BM. Thus, the process of reconfiguration requires shifting, with different degrees of radicalism, from an existing model to a new one. We contend that both phenomena are change phenomena and could lead to BMI. Xerox’s design of a leasing model to market the Xerox 914 in the late 1950s or Gillette’s design of the ‘Razor and Razor Blade’ model can be considered innovative designs. Indeed, they led to the emergence of new BMs not seen before. Not all design or reconfiguration efforts will necessarily lead to BMI, however. To be a source of BMI, the output of design or reconfiguration activities should be characterized by some degree of novelty or uniqueness. In other words, while in principle BMI may result as the product of design and/or reconfiguration of new and existing BMs, respectively, it constitutes a subset of the larger set comprising the whole product of BM design and reconfiguration activities (see Figure 21.1 ).

Business model innovation as a subset of business model design and reconfiguration

While sharing the potential for the same outcome (namely BMI), reconfiguration and design are two distinct activities that imply important differences. For example, because reconfiguration assumes the existence of a BM, it involves facing challenges that are idiosyncratic to existing organizations, such as organizational inertia, management processes, modes of organizational learning, modes of change, and path dependent constraints in general, which may not be an issue in new firms. On the other hand, newly formed organizations may face other issues such as considerable technological uncertainty, lack of legitimacy, lack of resources and, in general, liability of newness, which do influence the design and validation of new BMs (cf. Aldrich and Auster, 1986 ; Bruderl and Schussler, 1990 ). Because of these differences and for analytical purposes, we treat the above phenomena separately in the next two sections. 2

Business Model Design

As mentioned above, BMD refers to the very first instance of a new BM and is usually associated with entrepreneurial activity. The process of BMD could be considered a process of entrepreneurial venture creation involving the design of the content, structure, and governance of the transactions that a firm performs in cooperation with a network of exchange partners so as to create and capture value ( Amit and Zott, 2001 ). It involves traditional entrepreneurial activities such as internally and externally stimulated opportunity recognition, organization creation, linking with market ( Bhave, 1994 ), and also the design of boundary spanning organizational arrangements ( Zott and Amit, 2007 ). According to Zott and Amit (2007) , the latter is a critical feature of BMD in that ‘a BM elucidates how an organization is linked to external stakeholders, and how it engages in economic exchanges with them to create value for all exchange partners’ (2007: 181). Thus, BMD is concerned with traditional entrepreneurial choices (product/market mix, organizational design, control systems, etc.) as well as the design of a boundary spanning activity system, so as to link an offering (technology or service) to a realized output market. In a nutshell, BMD includes designs that take place across as well as within firms ( McGrath, 2010 ).

Uncertainty associated with the viability of new BMs may be considerable. Uncertainty arises not only because of entrepreneurs’ inability to predict customers’ response to their offering, future market conditions and dynamics, but also because of the computational and dynamic complexity associated with BM planning and design. Computational complexity arises because of the large number of logically possible combinations between BM components ( Afuah and Tucci, 2001 ), activities ( Zott and Amit, 2010 ) and/or choices ( Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010 ). Dynamic complexity arises because of the non-linear interdependencies—including delays and feedback loops—between BM components, activities, and/or choices. Both computational as well as dynamic complexity increase uncertainty surrounding BMD. Even if it were possible to detect future trends and changes, uncertainty would not be entirely eliminated, only reduced.

Uncertainty affects modes of BMD and associated entrepreneurial tasks. According to McGrath (2010) , unlike traditional concepts in entrepreneurship, such as business planning and business plan design, ‘strategies that aim to discover and exploit new models must engage in significant experimentation and learning’ (2010: 247). BMs cannot be fully planned ex ante . Rather, they take shape through a discovery-driven process; this process places a significant premium on experimentation and prototyping ( Sosna, Trevinyo-Rodríguez, and Velamuri, 2010 ; McGrath, 2010 ). Hayashi (2009) noted that many companies have had original BMs that did not work. This does not necessarily imply failure if companies are able to shift to Plan B . Hayashi proposes that in order to shift to plan B and ‘find’ the right business model, managers and entrepreneurs should engage in experimentation and challenge their initial assumptions. Investigating numerous ‘what if’ questions may be a useful strategy. The discovery-driven nature of BMs also affects the effectiveness of different design and planning approaches. Financial tools that make sense in an experimental world (e.g. real-options reasoning) may be more appropriate than more deterministic ones (e.g. projected economic value added and net present value) in supporting BMD ( McGrath, 2010 ).

While many new BMs may fail before a viable model is ‘found’, these (new BMs) may be a source of abnormal returns. As Ireland, Hitt, Camp, and Sexton (2001) note, entrepreneurs are often interested in finding fundamentally new ways of doing business and work on new models that have the potential to disrupt an industry’s competitive rules. According to McGrath (2010) , BM disruption may occur following Christensen’s model of disruptive innovation. At the beginning, these new models are more like experiments than proven business ideas and may not attract the scrutiny of incumbent firms. Newly formed ventures employing novel BMs often operate in market niches, serve customers that incumbents do not serve, and at price points they would consider unattractive, and rely on novel resources that are not necessarily under the control of incumbents. The latter may ignore the threats coming from innovative BMs. 3 And entrants could progressively experiment with their businesses and find disruptive channels.

Business Model Reconfiguration

The increasing consensus that BMI is key to firm performance (e.g. Ireland et al., 2001 ; Chesbrough, 2007 ; Johnson, Christensen, and Kagermann, 2008 ) has brought scholars working on the BM to focus on issues related to BM renewal and innovation in incumbent firms.

Considerations of issues related to BMI in incumbent firms were already present in Chesbrough and Rosenbloom’s study (2002) of the Xerox Corporation and its research center at Palo Alto (PARC). According to the authors, the BM as an heuristic logic might act as a mental map, which mediates the way business ideas are perceived by filtering information as valuable or not. This filtering process within a successful established firm is likely to preclude the identification of models that differ substantially from the firm’s current BM. In its cognitive dimension, the BM concept is similar to Prahalad and Bettis’ (1986) notion of a dominant logic . The dominant logic represents prevailing wisdom about how the world works and how the firm competes in the world. It can act as a filter of information, preventing managers from seeing opportunities and removing certain possibilities from serious consideration, when they fall outside of the prevailing logic and driving firms into a dominant logic trap ( Chesbrough, 2003 ).

Bouchikhi and Kimberly (2003) have referred to a similar phenomenon as the identity trap . In their view, an organization’s identity can become a trap when it so constrains strategic options that the organization cannot cope effectively with a changing environment. Attempts to change that are in conflict with this core identity are often doomed to failure. Chesbrough (2010) suggests two types of barriers to BMI in existing firms. The first type of barrier is structural. Barriers exist in terms of conflicts with existing assets and BMs (i.e. inertia emerges because of the complexity required for the reconfiguration of assets and operational processes). The second type of barrier is cognitive. It is manifested by the inability of managers who have been operating within the confines of a certain BM to understand the value potential in technologies and ideas that do not fit with the current BM.

Three tools are suggested that could help to overcome these barriers ( Chesbrough, 2010 ). The first consists of constructing maps of BMs to clarify the processes underlying them which then become a source of experiments to consider alternative combinations of the processes. The second involves conferring authority for experimentation within the organizational hierarchy. The third is experimentation itself. Experimentation is conceptualized as a process of discovery aimed at gaining cumulative learning from (perhaps) a series of failures before discovering a viable alternative to the BM. Sosna et al. (2010) have analysed the case of a Spanish family-owned dietary products business facing a threat to their BM of obsolescence from unforeseen external changes. The company was able to successfully reconfigure its BM thanks to experimentation, evaluation and adaptation—a trial and error learning approach—involving all echelons of the firm.

Giesen, Berman, Bell, and Blitz (2007) have proposed that BMI in incumbent firms can be classified into three groups: (1) industry model innovation, which consists of innovating the industry value chain by moving into new industries, redefining existing industries, or creating entirely new ones; (2) revenue model innovation, which represents innovation in the way revenues are generated, for example through reconfiguration of the product-service value mix or new pricing models; and (3) enterprise model innovation, changing the role a firm plays in the value chain, which can involve changes in the extended enterprise and networks with employees, suppliers, customers, and others, including capability/asset configurations. They analyse each type of innovation with respect to firm performance, and report two key findings: (1) each type of BMI can generate success, and (2) innovation in enterprise models focusing on external collaboration and partnerships is particularly effective in older companies relative to younger ones. Zott and Amit (2010) , who view the BM as a system of boundary spanning interdependent activities, have built on their decade-long research program on the BM and recently proposed that managers can fundamentally innovate a BM in three ways: by (1) adding new activities, (2) linking activities in novel ways, or (3) changing which parties perform an activity ( Amit and Zott, 2012 ). In other words, from a managerial standpoint, BMI consists of innovating the content (i.e. the nature of the activities), the structure (i.e. linkages and sequencing of activities) or the governance (the control/responsibility over an activity) of the activity system between a firm and its network ( Zott and Amit, 2010 ).

To become BM innovators, companies need to create processes for making innovation and improvements ( Mitchell and Coles, 2003 ). Doz and Kosonen (2010) have proposed a leadership agenda for accelerating BM renewal. To overcome the rigidity that accompanies established BMs, companies should be made more agile, which can be achieved by developing three meta-capabilities: strategic sensitivity, leadership unity, and resource flexibility. Doz and Kosonen point to the importance of the top management team to achieve collective commitment for taking the risks necessary to venture into new BMs and abandon old ones. Santos, Spector, and Van der Heyden (2009) have proposed a theory of BMI within incumbent firms in which they emphasize the importance of the behavioural aspects involved through mutual engagement and organizational justice. BMI, they argue, should not only consider the structural aspects of the formal organization (typically activity sets), but should also focus on informal organizational dynamics.

More recently, Bock, Opsahl, and George (2010) have linked the research on the BM with the notion of strategic flexibility ( Shimizu and Hitt, 2004 ) and proposed that firms engage in BMI to gain strategic flexibility by enhancing capabilities to respond to environmental complexity while decreasing formal design complexity.

The fragmented and young literature on BMR in incumbent firms implicitly offers a snapshot of the theoretical richness and challenges associated with studying the phenomenon as well as with carrying out the managerial tasks associated with the process of reconfiguration. Johnson et al. (2008) , perhaps not surprisingly, have noted that during the past decade of the major innovations within existing corporations ‘only a precious few have been business model related’ (2008: 52). BMR may well represent an extension of what Henderson and Clark (1990) initially conceived as ‘architectural’ innovation, that is, complex innovations that require a systemic reconfiguration of existing organizational and technological capabilities. Indeed, BMR is a complex art. As Teece (2007) notes, it requires ‘creativity, insight and a good deal of customer-competitor and supplier information and intelligence’ (2007: 1330). Additional complexity is added in incumbent firms by the existing repertoire of capabilities that constrain managers’ ability to innovate the BM, either blinding it ‘from seeing novel opportunities to innovate or acting upon those opportunities when they see them’ ( Pisano, 2006 : 1126).

Business Models and Sustainability

While studies of the BM have traditionally emphasized its importance for firms’ success, a new literature is emerging that studies the role of BMI in promoting sustainability (cf. WCED, 1987 ), analysing BMI from the point of view of its consequences in terms of either corporate social and environmental impact or as a strategic implication for sustainability (i.e. a way to align firms’ search for profits with innovations that would ultimately benefit society and help solve sustainability issues—see chapter 15 by Berkhout).

Firms could create value for sustainability in two ways: (1) by adopting more sustainable practices and processes that would reduce (or prevent the occurrence of) ‘end-of-pipe’ negative impacts (for example, reducing energy, water consumption and material intensity or social problems such as work place stress); or (2) by engineering and marketing new technologies that would help solve sustainability problems (for example, renewable energies, electrical vehicles [EVs], or green materials). In other words, value for sustainability may exist in a firm’s practice(s) or in a firm’s product(s), or both.

While there are different strategic alternatives along the product-practice mix to develop solutions for sustainability issues and improve corporate sustainability performances, market externalities of various forms could prevent profit-seeking firms from fully embracing sustainability and dilute the effectiveness of their initiatives. Activities that have an adverse environmental impact (such as pollution) or a negative social impact (such as exploitation of labour in marginalized and disadvantaged groups) are not fully internalized in the costs of enterprises’ products/services ( Cairncross, 1993 ). Accordingly, firms wanting to improve their environmental and social performance face a structural constraint (i.e. the risk associated with the implementation of sustainability when the market does not reward sustainability initiatives). Similarly, in the absence of appropriate government incentives or market regulation, green technologies may be more expensive than traditional ones—for decades an impediment to the market diffusion of certain technologies related to renewable energies.

Another problem is related to a different type of network externality in complex technological systems. Many technologies provide no value for customers unless necessary complements are also available and this problem applies to traditional and sustainable technologies alike. EVs are of no value if there is no necessary complementary technology (e.g. batteries) or infrastructure such as battery charging stations. The same two- (or three-) sided market argument can be reversed. For example, developing an infrastructure for EVs makes no economic sense if there is no available technology for producing reliable and cost-efficient EVs. The market diffusion of greener technologies may be hampered because firms may not control the full technological architecture necessary to realize the value of a technology.

Some authors have suggested that by innovating their BM, firms could overcome these barriers and make profits while benefiting the environment. For example, service-based BMs (selling a service rather than a product) could contribute to aligning firms’ search for profitability with innovating for sustainability. For example, when the carpet company Interface shifted from selling carpets to a ‘floor covering service’ ( Lovins, Lovins, and Hawken, 1999 ), it started to research, design, and manufacture more recyclable carpets. Under the new BM, when the carpets become worn, Interface replaces them and re-introduces the old ones back into the supply chain; if carpets are highly recyclable, the firm profits from this operation while benefiting the environment. The carpets themselves are eventually designed as tiles so that only consumed parts need to be replaced. The recyclable, modular carpets significantly reduce material and energy consumption, allowing Interface to deliver a better service that costs far less to create and capture the value arising from the new operations ( Lovins et al., 1999 ). Offering services rather than products, and working innovative pricing strategies and novel revenue streams, would also help firms marketing more expensive green technologies and spread their market adoption. As Wüstenhagen and Boehnke (2006) have noted, ‘Given the capital intensity of sustainable energy technologies…reducing the upfront cost for consumers is one of the key concerns in marketing innovation in this sector’ (2006: 256). BMs based on leasing or contracting, or a mix of products/services may represent a solution to the problem ( Wüstenhagen and Boehnke, 2006 ). Finally, new BMs could also help overcome issues of strategic complementarities and solve coordination issues. Better Place, the global provider of EV networks and services, worked to accelerate the transition to sustainable transportation by facilitating the market diffusion of EVs. The company’s BM was not based on EV manufacturing; rather, it was based on alliances with EV manufacturers, utility companies, governments, battery manufacturers, and others to produce a market-based transportation infrastructure that would support EV diffusion. By positioning itself upstream in the value system, and by orchestrating the network with a unique BM, the company attempted to solve two-sided market issues in sustainable transportation. However, Better Place’s bankruptcy in May 2013 demonstrates some of the complexity associated with developing new BMs for sustainability.

Business Model-related Ideas: The Theory and Practice of BMI

The BM is a systemic and conceptually rich construct, involving multiple components, several actors (boundary spanning) and complex interdependencies and dynamics. Because of that, the managerial cognitive effort required to visualize and explore possibilities for BMI as well as the effort for orchestrating (implementing and managing) the architecture of innovative BMs may be considerable.

Awareness of the complexities associated with BM cognition—description of existing BMs or design of new ones—coupled with the increasing relevance of BMs and business modelling for practice (cf. Zott et al., 2011 ), have led academics and practitioners to propose several avenues and tactics in support of BMI. Different tools such as perspectives, frameworks, and ontologies have been proposed that employ a mix of informal textual, verbal, and ad hoc graphical representations. These tools ascribe, with varying degrees, to three core functions at the nexus between the theory 4 and practice of BMI. First, they offer a ‘ reference language’ that fosters dialogue, promotes common understanding, and supports collective sense-making (cf. Amit and Zott, 2012 ). Second, by offering scaled-down simplified representations of BMs, they allow for graphical representations that simplify cognition and offer the possibility of virtually experimenting with BMI (for example, by supporting the formulation and elaboration of important ‘what if’ questions and the evaluation of strategic alternatives: Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010 ). Third, they offer representations—both graphical as well as verbal—that allow managers and entrepreneurs to articulate and instantiate the value of their venture and to support the engagement of external audiences so as to gain legitimacy, activate resources, and foster action. We note that different tools and perspectives tend to emphasize certain functions while overlooking others. For example, the strength of certain perspectives resides in their simplicity and parsimony. As such, these perspectives are particularly effective in supporting collective sense-making around a BM. Other perspectives are more articulated; their development may be slightly more arduous but allow for a better appreciation of the dynamics occurring between the various components of a BM (cf. Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2007 , 2010 ).

More broadly, we note and illustrate in Figure 21.2 that tools supporting BMI could be structured into several levels of decomposition with varying depth and complexity depending on the degree to which they abstract from the reality they aim to describe. 5

At the highest level of abstraction is a view of the BM as a narrative ( Perkmann and Spicer, 2010 ). According to Magretta (2002) , the BM is a story, a verbal description of how an enterprise works. It should be noted that BM narratives not only entail a descriptive function, but also a normative one. According to Brown (2000) , narratives represent an important way in which people seek to infuse ambiguous situations with meaning and persuade sceptical audiences that their account of reality is believable. Perkmann and Spicer (2010) have suggested that because of their forward-looking character, BM narratives play an important role in inducing expectations among interested constituents about how a business’s future might play out. Narratives of the BM can be constructed by managers and entrepreneurs and used not only to simplify cognition, but also as a communicative device that could allow achieving various goals, such as persuading external audiences, creating a sense of legitimacy around the venture (for example, by drawing analogies between a venture’s BM and the BM of a successful firm) or guiding social action (for example, by focusing attention on what to consider in decision-making and instructing how to operate).

The recognition of patterns in the structure of BMs has led to the introduction of typologies and BM archetypes . An archetype can be understood as an ideal example of a type, in this case a BM. A well-known example is the Freemium BM, adopted by firms such as Acrobat: its core logic lies in delivering a basic version of the product for free and charging for a premium version. Gillette popularized what today is known as the Razor and Razor Blade BM, which rests on ‘selling cheap razors to make customers buy its rather expensive blades’ ( Zott and Amit, 2010 : 218). This model is now popular in other industries where products such as printers (and cartridges) or game consoles (and software games) are brought to market relying on a similar logic. Archetypes are often presented with an identifying label (a ‘title’ that identifies the BM type) followed by a short description of the core essence of the BM. Archetypes perform several functions, including offering descriptions of ‘role models’, that is, models to be followed and imitated ( Baden-Fuller and Morgan, 2010 ).

While narratives and archetypes may serve several important purposes, they tend to be difficult to manipulate and manoeuvre (e.g. it is difficult to evaluate the likely consequences of changes in one part of the BM on the entire system on the basis of a narrative or an archetype). Higher descriptive accuracy, and perhaps a more rigorous approach to structuring and organizing plans for BMI, are offered by graphical frameworks of the BM, which are conceptualization and formalization of the BM obtained by enumerating, clarifying and representing its essential components (see Figure 21.2 ). A popular example among managers and practitioners is represented by the Business Model Canvas 6 (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2002). The Business Model Canvas offers a scaled-down representation of the generic BM that is obtained by enumerating and visualizing what the authors consider to be the nine critical components of a BM. Similarly, Johnson and colleagues ( Johnson, Christensen, and Kagermann, 2008 ; Johnson, 2010 ) have proposed a simple framework comprising four interdependent elements; customer value proposition, profit formula, key resources and key processes. By focusing on these elements the framework offers a synthetic ‘representation of how a business creates and delivers value, for both the customer and the company’ ( Johnson, 2010 : 22).

Business models at different levels of abstraction from ‘reality’

We contend that the power of frameworks and archetypes, and perhaps the explanation of their popularity among practitioners, stands in their simplicity and parsimony, which, however, come at the expense of descriptive depth. In particular, frameworks and archetypes have shortcomings in their inability to offer a full account of the dynamic aspects associated with a particular BM. Meta-models 7 of the BM may help to overcome this limitation. Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010) have built on system dynamics ( Sterman, 2000 ) and offered a way to conceptualize and represent BMs based on choices and consequences, and on an evaluation of the degree to which consequences are flexible vs. rigid (an important aspect to consider in dealing with BM reconfiguration). Causal loops (both damping and self-reinforcing) support understanding of how the architecture of choices drives the overall behaviour of a BM and leads to a configuration of consequences. This perspective allows for a more fine-grained description of existing BMs supporting the use of ‘theories’ to describe and understand the link between choices and likely consequences.

Gordijn and Akkermans (2001) have proposed a conceptual modelling approach that they call the ‘e3-value ontology’, designed to help define how economic value is created and exchanged within a network of actors. This modelling technique takes a value viewpoint, unlike other traditional modelling tools that take either a business process viewpoint (typical of operations management) or a system architecture viewpoint (typical of the information systems literature). The proposed meta-model borrows concepts from the business literature such as actors, value exchanges, value activities, and value objects, and uses these notions to model networked constellations of enterprises and end-consumers who create, distribute, and consume things of economic value.

In a similar vein, Zott and Amit (2010) have proposed an activity system perspective for supporting the design of new BMs. This perspective relies on an understanding of the BM as a system of interdependent activities (rather than choices and consequences) centered on a focal firm and including those conducted by the focal firm, its partners, vendors or customers, and so on. As such, it allows describing and conceptualizing BMs with considerable depth and accuracy. According to the authors, ‘an activity in a focal firm’s BM can be viewed as the engagement of human, physical and/or capital resources of any party to the BM (the focal firm, end customers, vendors, etc.) to serve a specific purpose toward the fulfillment of the overall objective’ (2010: 217). To better understand the BM as a set of interdependent activities, Zott and Amit differentiate between design elements (i.e. content, structure, and governance) and design themes (efficiency, novelty, complementarities, and lock-in). Design elements comprise the selection of activities (content), the sequencing between them (structure) and choices concerning who performs them (governance) within the network. Taken together, design elements comprise the infrastructural logic of a BM’s architecture. In addition, managers could structure the activity system around different design themes . For example, ‘efficiency-centred’ design (with efficiency being a design theme) refers to how firms use their activity system design to aim at achieving overall greater efficiency through reducing transaction costs. Other design themes are ‘novelty’ (innovation in the content, structure, or governance of the activity system), ‘lock-in’ (BM whose central feature is the ability to keep third parties attracted as a BM participant) or ‘complementarities’ (bundling activities within a system so as to produce more value than running activities separately).

Managing Business Models

Challenges associated with managing BMI go beyond the complexities related to managerial cognition and sense-making. While BMI has the potential for transformative growth and exponential returns for the innovator, it is a highly risky move that may involve changing the entire architectural configuration of a business. Accordingly, a critical challenge for managers is understanding when new BMs are needed ( Johnson, 2010 ). Once opportunities have been identified whose exploitation requires the development of new BMs, managers in incumbent firms may be confronted with problems related to simultaneously managing multiple BMs ( Markides and Charitou, 2004 ). Firms entering the BOP, or addressing new needs or new customer segments, are challenged by the potential conflicts between dual BMs (cf. Markides and Charitou, 2004 ). In this section we describe some of the key findings and insights from research in this important area of organization studies.

BMI can support companies in exploiting new opportunities (seizing ‘white space’) in three different ways ( Johnson, 2010 ): (1) by supporting the development of new value propositions that would address an unsatisfied ‘job-to-be-done’ for existing customers; (2) by tackling new customer segments that have traditionally been overlooked by existing value propositions; or (3) by entering entirely new industries or a ‘new terrain’. These instances present different managerial challenges and opportunities related to BMI.

First, the extent to which the development of new value propositions for an existing customer base requires BMI is a function of the shifts in the basis of competition (cf. Moore, 2004 ). At different stages in market development companies compete and innovate on different dimensions as illustrated in Figure 21.3 .

At early stages, customers’ unsatisfied needs mostly relate to product features and functions. Companies compete accordingly on functionality and focus on product innovation. When functionality-related needs are mostly fulfilled, the basis of competition shifts as customers require higher quality and reliability. In these cases, innovation is mostly process-oriented. When quality and reliability have improved sufficiently, customer value is provided by convenience, customization, and finally, when the market starts becoming commoditized, by lower costs. According to Johnson, managers should focus on BMI at these stages in market evolution, in that innovative BMs may allow developing new customer value propositions in response to commoditization in a way that product and process innovation would not. Innovative BMs may allow developing entirely new value propositions tailored to the customers’ individual needs, or may be able to lower costs significantly. 8

Second, innovative BMs may unlock opportunities to serve entirely new customer segments. These instances correspond to a process of democratization (cf. Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010 ) in that they allow extending products and services to potential customers who are non-consumers, for instance because existing offerings are too expensive (with respect to potential customers’ wealth), complicated (with respect to potential customers’ skills) or because potential customers lack access (both geographical distances, lack of information and/or time) to them. Attempts to reach customers at the BOP, as previously discussed, fall into this category.

While serving existing customers in innovative ways or reaching new potential customers may require developing new BMs in response to identifiable and somehow predictable market-driven circumstances, a third category of opportunities is offered by less predictable tectonic industry changes, resulting, for example, from technological discontinuities or dramatic shifts in government policy and regulation. BMI can support companies creating new business platforms uniquely suited to the radically altered terrain, such as the innovative BM developed by Better Place, which attempted (unsuccessfully, in hindsight) to exploit opportunities arising from a complex plethora of forces increasingly supporting demand for sustainable greener transportation.

Market development and BMI

Kaplan (2012) proposes that BMI should in fact be treated with equal importance to product innovation and provides a practical guide for incumbents, starting with fifteen principles for BMI divided into three major categories: connect, inspire, and transform. Connect concerns the ‘team sport’ nature of BMI and how to nurture it, for example enabling chance meetings between innovators outside of normal ‘silos’, putting into place structures enabling flexible collaborative networks from across the company, and emphasizing collaborative design thinking. Inspire refers to injecting a sense of meaning into developing new ideas, encouraging systems-level thinking, challenging current assumptions, and experimenting rapidly. Transform is about encouraging large-scale rather than incremental changes, constantly trying new things, and building urgency to innovate. Kaplan also tackles the important problem of how to conduct R&D for BMI, returning to the theme of experimentation and proposing a ‘BMI factory’ that is a ‘connected adjacency’ with the current one (rather than trying to destroy the current one), championed by top management, explicitly desired, staffed with innovators taking on diverse roles (such as idea generators, ethnographers, and BM designers) and maintained as a separate activity from product innovation that supports the current BM.

A critical managerial challenge related to the management of BMs is represented by the conflicts arising from multiple BMs ( Markides and Oyon, 2010 ). Seizing new opportunities by developing new BMs may involve, for existing firms, operating (or considering) two BMs at the same time ( Markides and Oyon, 2010 ). For example, to tap potential customers in India, Hindustan Unilever (the Indian subsidiary of Unilever) operates with a BM that is different from the parent’s BM. ING Group started the highly successful ING Direct to tap into not only Internet financial services users, but the different ways those users utilize such services. Singapore Airlines has launched SilkAir to appeal to customers in the low-cost segment of the market in addition to its traditional operations.

According to Markides and colleagues, there are serious tradeoffs involved in competing with dual BMs, as a new BM risks cannibalizing existing sales and customer bases, destroying or undermining the existing distributor network, compromising the quality of services offered to customers, or simply defocusing the organization by trying to do everything for everybody ( Markides and Charitou, 2004 ). To manage these tradeoffs, strategy experts have traditionally proposed keeping the two BMs separated in two different units (cf. Christensen, 1997 ). Instead, Markides and Charitou (2004) propose a contingency approach, according to which the quest for the best strategy is understood as fundamentally depending on (1) the degree to which the two BMs are in conflict, and (2) the degree to which the two markets related to the BMs are perceived to be strategically similar. Reducing these two dimensions to dichotomous situations (serious vs. minor conflicts and high vs. low strategic relatedness) leads to four logically possible situations with four different strategies. The latter includes both pure strategies (i.e. separate vs. integrate) as well as hybrid ones (e.g. start with integrated BMs while preparing the conditions for future ‘divorce’ or start separate preparing conditions for future ‘marriage’). Hybrid strategies require the organization to become more ambidextrous. Operational tactics for managing dual BMs include conferring operational and financial autonomy to separate units, allowing units to develop their own culture and budgetary system and to have their own CEOs, while, at the same time, encouraging cooperation by means of a common incentive and reward system and by transferring the CEO from inside the organization rather than appointing one from outside.

In this chapter, we have reviewed the small but rapidly growing literature on BMs and BMI. In the course of most industrial sectors and humanitarian undertakings, there will come a time when the traditional way of creating, delivering, and capturing value is no longer valid, efficient, useful, or profitable. In such moments (or perhaps just before!), organizations that embrace BMI will embrace the possibility to reshape industries and possibly change the world. As this exciting field is expanding every day with increasing scholarly and managerial interest, we hope this chapter helps establish a better and more uniform understanding of BMI, and helps bridge the gap between theory and practice.

In economics and business management the Bottom of the Pyramid (or ‘Base of the Pyramid’ or simply ‘BoP’) is the term used to refer to the largest but poorest socio-economic group. The expression is used in particular by people developing new models of doing business that deliberately target that demographic, often using new technology.