How to Conduct Change Management Risk Assessment

Are you preparing to transition your organization or team through a period of significant change?

With any change comes some inherent risk, which can be both exciting and anxiety provoking.

To ensure the success of such an endeavor it’s important to plan for, mitigate and manage risks as they arise throughout the process.

In this blogpost we’ll discuss why business leaders and managers needs to pay attention to potential risks and learn how to conduct change management risk assessment in order to execute a successful transition.

What is Change Management Risk?

The factors which can negatively affect achieving desired change outcome, primarily due to insufficient planning or lack of change-readiness among stakeholders.

Change management risk can lead to delays in implementation and results, increased costs and compromised quality standards, ultimately impacting an organization’s bottom line.

It is essential for organizations to mitigate change management risks by creating a clear change strategy with well-defined objectives, monitoring change goals and gathering feedback from stakeholders along the way.

Why it is important to identify change management risk?

Change is inherent in any business, and change management can be challenging. Adequately assessing change management risks helps to minimize unexpected outcomes, increases efficiency and effectiveness, and bolsters the flexibility of organizational processes.

It is essential that organizations acknowledge the need to identify change management risks, as failure to do so may lead to project delays, budget overruns and costly repair work.

By critically diagnosing change management risk associated with specific projects or events, an organization is better equipped to develop tailored strategies for successful change implementation. Ultimately, change management risk identification is a critical step for ensuring key change objectives are met on time and within budget.

Change Management Risk Assessment

Change management risk assessment is a crucial process for organizations to mitigate the risks associated with change. It involves looking at potential change initiatives, and examining how they may affect an organization’s resources and operations.

The results of change management risk assessment allow us to make well-informed decisions on the implementation and potential success of change initiatives.

To successfully complete change management risk assessment, it is important to determine objectives, analyze relevant data sources, identify risks and their root causes, and create viable response plans.

This is ultimately done through establishing processes that help organizations develop stability during a time of transition, enabling them to achieve successful outcomes more efficiently.

04 Steps to Conduct Change Management Risk Assessment

In order to conduct change management risk assessment, there are several key steps that need to be taken.

Step 1: Define change management risk assessment framework

It is important to have a clear understanding of what the change initiative is aiming to accomplish, as this will inform the risk assessment process. During this step, it is also important to establish a change management risk assessment framework. This framework should provide the foundation for identifying change management risks and understanding their potential impact on the organization.

The change management risk assessment framework should be tailored to the specific change initiative and take into account any existing organizational change processes. This will ensure that all stakeholders are fully aware of the change objectives, can recognize change management risks, and have an understanding of the steps needed to effectively address risk.

Step 2: Analyze data

The second step to conducting change management risk assessment is to analyze data sources. This involves gathering information from a variety of sources such as internal documents, reports, and interviews with stakeholders. It is important to identify the key change components and assess their potential impacts in order to recognize change management risks.

Through data analysis, organizations can gain greater insight into change management risks and their impacts on their operations. Data analysis allows organizations to identify change management risks and the underlying causes, evaluate the solutions available to them, and make informed decisions when managing change initiatives.

Step 3: Identify and analyze risks

The third step to conducting change management risk assessment is to analyze the change management risks identified. This involves understanding their root causes and evaluating their potential impacts on the organization. It is important to identify any assumptions, dependencies, or interdependencies that could affect change management risk assessment outcomes.

Organizations should also assess whether existing change processes are adequate enough toeffectively manage change risk. This includes considering the impact that change initiatives will have on existing structures, processes and systems, as well as understanding the resources available to address change risks.

Step 4: Develop response plans

The next step to conducting change management risk assessment is to develop response plans. This involves formulating strategies and tactics to mitigate change risks, as well as determining possible contingencies in the event that change initiatives do not succeed. During this stage, organizations should identify resources necessary for successful change implementation, such as personnel and technology.

It is important to prioritize change management risks in order to ensure that the most critical risks are addressed first. This involves understanding the potential impact of each change risk on the organization, and identifying which risks should be addressed to mitigate their effects.

What are common risks of change management

Following are some common risks of change management:

lack of understanding or buy-in from stakeholders

The lack of understanding or buy-in from stakeholders is one of the most common change management risks. This risk can arise when stakeholders are not fully aware of change objectives, or do not agree with the change initiatives being undertaken. In such cases, stakeholders may resist change initiatives or take actions that undermine their success.

Inadequate change management practices and processes

Inadequate change management practices and processes can also be a major risk to change initiatives. Organizations must ensure that change strategies are understood, agreed upon, and implemented effectively in order to maximize the chances of change success. Without an effective change management process in place, organizations may find themselves unable to adjust quickly enough to address risks.

Ineffective communication

Organzations often make mistake by having one-way communication with employees and other stakeholders. This is one of the biggest risk of change management. Change is not successful if its message is only coming from top and voices of employees or other stakeholders are unheard. If organizational culture fails to exchange ideas and share experience then it’s hard to implement transformative change.

An excessive change implementation timeline

An excessive change implementation timeline can pose a serious risk to change management, as it often leads to delays, slowdowns, and potential abandonment of change initiatives. When change initiatives take too long to implement, they can become costly and complex affairs that may not yield the desired results.

Inadequate change control measures

Inadequate change control measures are one of the most common change management risks. These typically arise when change initiatives are not reviewed and approved on a timely basis. Without proper change control mechanisms in place, change initiatives can go unchecked and progress without proper risk assessment and validation.

Misaligned change initiatives with organizational objectives

Misaligned change initiatives with organizational objectives can be a major change management risk. When change initiatives are not in alignment with the organization’s overall goals and objectives, they can lead to wasted resources, reduced efficiency, and even failure of the change initiative.

Final Words

Assessing risks is a key component of successful change management. By understanding what could go wrong and taking steps to mitigate those risks, you can increase the chances of your change initiative being successful. There are many different ways to assess risks and some common risks associated with change management initiatives include resistance to change, lack of resources etc. By taking the time to understand these risks and develop a plan to address them, you can set your change initiative up for success. Do you have a plan in place to assess risks to your change management initiative? What are some of the most common risks you’ve encountered during past initiatives?

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

A Guide to Conducting SWOT Analysis for Startups

What is Leavitt’s Diamond Model?

Change Management Commitment Curve – Explained

What Could Go Wrong? How to Manage Risk for Successful Change Initiatives

David Shore, instructor of Strategies for Leading Successful Change Initiatives, shares six steps to effective risk management.

David Shore

Every change initiative comes with inherent risk. But too often we shy away from exploring the potential pitfalls at the outset. If we are to succeed, however, we should embrace risk. After all, change initiatives are born from a risk analysis — a conclusion that the risk of doing nothing is higher than the risk of embarking on an experimental initiative.

When leading a change initiative, you should focus on acknowledging, anticipating, and managing risk — instead of avoiding it at all costs.

The good news is that risk management is not rocket science. Through my extensive work with change initiatives, I’ve identified six key steps to effective risk management. By following these steps on your initiative, I hope you’ll discover how embracing risk can lead to success.

Six Steps to Effective Risk Management

1. at the start, identify the risks you face..

Make a list. Formalize this process by holding a premortem . Just as a postmortem enables the team to assess what went right or wrong after the fact, a premortem provides a space for thinking in advance about what could go wrong during the project. As you and your team brainstorm, you should cast a wide net. Consider factors intrinsic to the project and also those outside the team’s control. For example, consider the risk of potential resistance from stakeholders, which nearly always arises in change initiatives.

2. Quantify the Risks.

Not all risks are created equal. The risk of a slight delay in funding might be very different from the risk of a major partner pulling out of a joint venture. By quantifying the risk, you decrease the influence emotions can play and allow different risks to be compared. One method is to assess the risk along two dimensions: the probability of the risk occurring, and the impact the risk would have if it actually occurred. Using a scale from one to five, you can evaluate each of these dimensions for the risks you’ve identified. Then, you can multiply the two numbers to produce a risk factor from 1 to 25.

3. Establish a Risk Threshold.

Consider your initiative’s tolerance for risk and then establish a threshold. If you are not sure where to start, set your threshold at the center of your risk scale. For example, on a scale of 1 to 25, start with 12 as your threshold. Compare your quantified risks to the threshold and then spend some time thinking about the ones that exceed the threshold and then adjust as needed.

Search all Business Strategy programs.

4. Create Contingency Plans.

For each risk, engage in a thought experiment. First, think about what steps you can take, if any, to eliminate or mitigate the risk. It may be that a small adjustment to your plan will reduce the probability to zero. Second, think about what you plan to do if that possibility becomes reality — in other words, if the risk becomes an issue. Will the team be able to work around it easily? Or will the magnitude of that risk require rethinking your entire initiative? The more you plan for risks ahead of time, the better prepared you will be — and the more successful you will be in keeping your initiative on track

5. Monitor Risks over Time.

Along with the Gantt charts, status reports, dashboards, and other tools that help you assess your progress, you can also create a Risk Register (also called a Risk Log) that sets out all the risks, their risk factors, and current status. As you reach a particular milestone, perhaps one risk can be eliminated from consideration because it is no longer possible. Perhaps another risk has created an issue that needs to be dealt with. Or perhaps a new risk has been identified and should be evaluated. Your goal is to keep a close eye on risk throughout the project.

6. Consider Assigning a Risk Watcher.

You may want to identify a particular team member who has the responsibility to monitor risks and raise flags. Teams working on change initiatives are by definition optimistic. While everyone else on the team might be saying, “This will go fine,” someone needs to be able to say, “Clouds are rolling in” or “We’ve said that for the last six meetings and it hasn’t happened.”

To manage risk successfully, you need to be proactive in anticipating it. And to lead a change initiative successfully, you need to be an honest communicator. Talk with your team and with upper management about risks to the project and issues that crop up along the way. As a manager, you can improve your ability to manage risk by fostering a culture that values positive thinking while encouraging open discussions about problems.

Embracing change means embracing risk. With the right pragmatic approach, you can become a more effective change agent by understanding risk as a natural part of change — and by anticipating and managing it.

Find related Business Strategy programs.

Browse all Professional & Executive Development programs.

About the Author

Shore is an authority on change management recognized as distinguished professor at Tianjin University of Finance and Economics and 2015 Top Thought Leader in Trust.

Why Marketers Should Start Thinking Like Designers

Follow this 5-step process for applying design thinking to your marketing strategy.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Are you a ComplianceQuest Customer?

What is Change Control?

Change Control is a systematic and structured process employed across various industries to manage modifications or alterations to a project, system, or process.

It ensures that changes are implemented in a controlled and organized manner, minimizing risks , preventing disruptions, and maintaining the overall integrity of the entity undergoing modification. Change control is particularly prominent in project management, regulatory environments, and quality management systems .

How Change Control is Critical in Project Management?

In project management, Change Controls involves a series of steps, including the identification of proposed changes, their assessment for potential impacts on scope, schedule, and budget, obtaining approvals from relevant stakeholders, and implementing approved changes in a controlled manner. This process prevents unauthorized modifications, commonly called scope creep, and helps maintain project focus.

Change control is crucial in regulated pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and manufacturing industries. For example, Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) mandates that any changes proposed or implemented to processes, equipment, or materials must undergo a rigorous control change process to ensure product quality and safety are consistently upheld. This includes assessing the impact of changes, obtaining approvals, and documenting the entire process for regulatory compliance.

Related Assets

Integrated Change Control is essential for maintaining project control, preventing scope creep, and ensuring that changes contribute positively to project…

The main difference is Change Control focuses on technical aspects, Change Management addresses the human and cultural aspects. Both are…

If you work in quality management you probably know that the effectiveness of a Quality Management System (QMS) relies extensively…

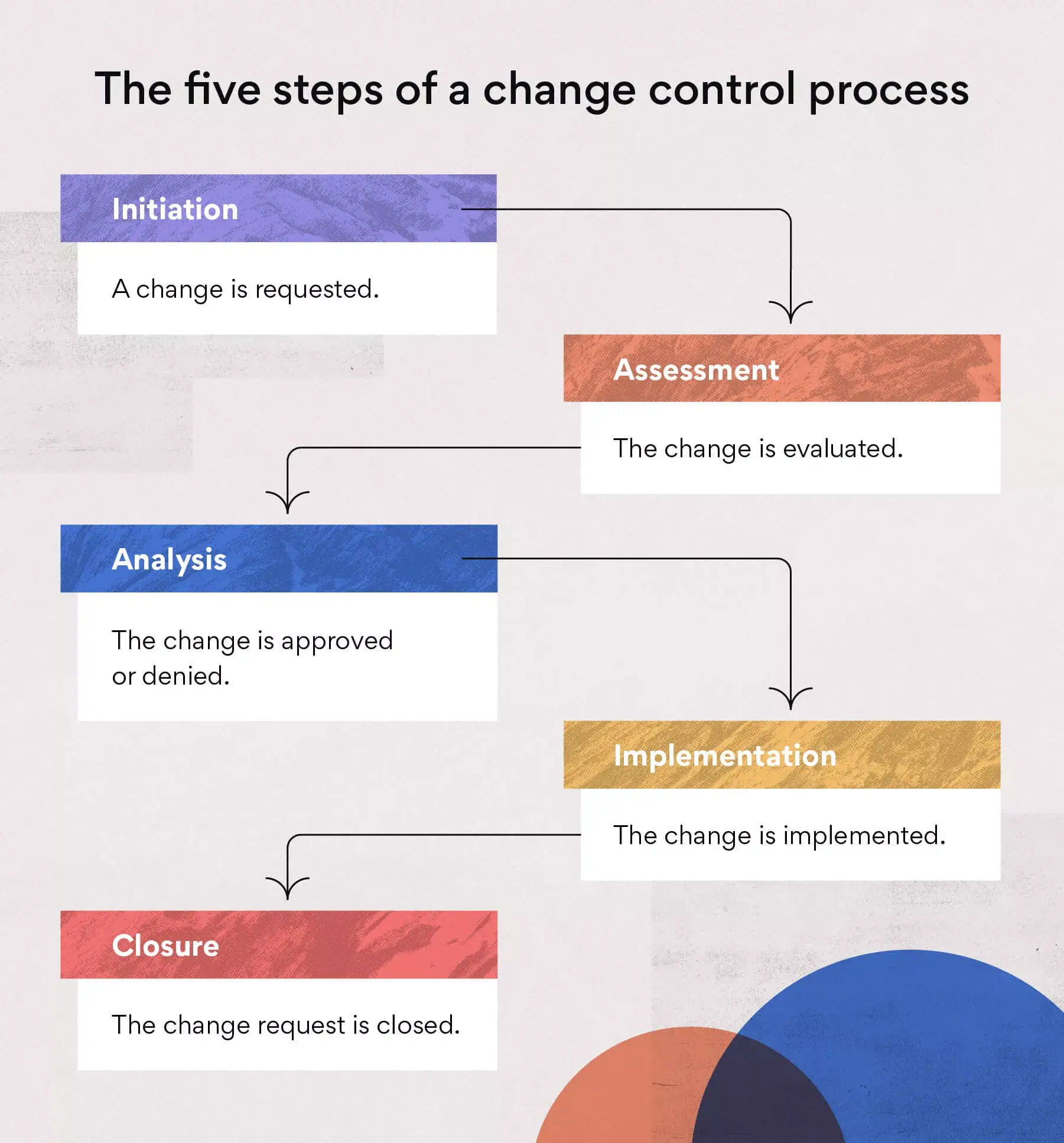

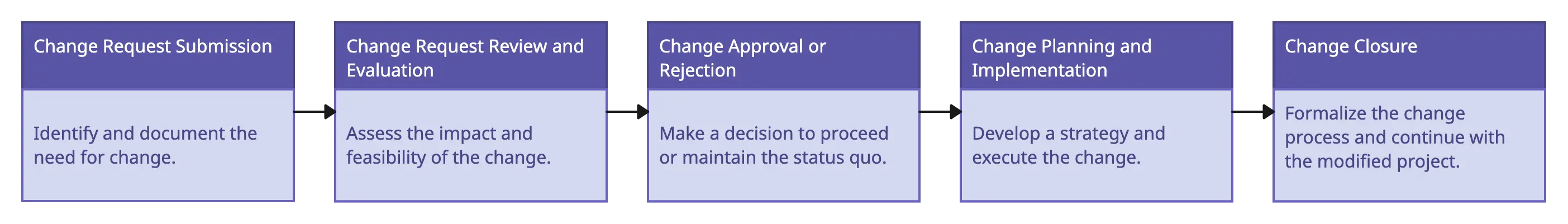

What are the Five Steps of a Change Control Process?

The five steps of a change control process are:

- Change request initiation is the first step in the change control process. It identifies and documents the proposed change. The change request should include

- A description of the change

- The reason for the change

- The impact of the change, and

- The proposed implementation plan

- Change request assessment comes once a change request has been submitted. It is done to determine its feasibility and impact. This assessment may involve

- Reviewing the change request with stakeholders

- Evaluating the potential risks and benefits

- Estimating the cost and resources required to implement the change

- Change request analysis is the next step if the change request is deemed feasible and has a positive impact. It is done to develop a detailed implementation plan. This plan should include

- Specific tasks

- Timelines, and

- Responsibilities for implementing the change

- Change request implementation happens once the change request has been approved and the implementation plan has been finalized. This involves making changes to processes, procedures, or systems. It is essential to monitor the implementation of the change to ensure that it is going smoothly without any unnecessary consequences.

- Change request closure is the last step once the change has been implemented and evaluated. This involves

- Documenting the lessons learned from the change

- Updating any relevant documentation.

What are the Benefits of a Change Control Process?

The benefits of a Change Control Process in project management are numerous and play a crucial role in ensuring the success and stability of projects. Here's an elaboration on the listed benefits:

Increased Productivity

A Control Change Process helps prevent unmanaged changes or scope creep. By formalizing, evaluating, and implementing changes, teams can stay focused on the original project objectives, avoiding unnecessary disruptions and ensuring that resources are used efficiently.

Effective Communication

Clear communication is essential in project management, especially when changes are involved. A structured Change Control Process facilitates effective communication by defining how changes are identified, assessed, and communicated to relevant stakeholders. This reduces the risk of misunderstandings.

Better Teamwork and Collaboration

The Change Control Process includes project managers, team members, and decision-makers. Collaborative decision-making ensures that changes are thoroughly evaluated from different perspectives, leading to better-informed decisions. This collaborative approach fosters teamwork and a shared responsibility for project outcomes.

Optimizing Change Management Throughout the Product Development Lifecycle

Explain change control in project management.

Change Controls in project management refers to the systematic process of managing changes to the project scope, schedule, or other project elements in a controlled and organized manner. It involves identifying, evaluating, approving, and implementing changes while minimizing potential negative impacts on the project.

Key Components of Change Control in Project Management:

Change Identification

Any proposed change to the project, whether it involves scope, schedule, or other elements, needs to be formally identified. This could come from various sources, including stakeholders, team members, or external factors.

Change Assessment

The proposed change is assessed for its impact on the project. This involves evaluating how the change may affect the project scope, timeline, budget, and other key parameters.

Change Approval

Changes are presented to relevant stakeholders, and approval is sought based on the assessment. Depending on the project's governance structure, this could involve project sponsors, clients, or other decision-makers.

Change Implementation

Once approved, the change is implemented in a controlled manner. This includes updating project plans, communicating changes to the team, and ensuring the project remains on track.

Documentation and Communication

Documentation is crucial throughout the change control process. Changes, assessments, approvals, and implementations are documented to maintain a clear record. Communication ensures that all stakeholders are informed of changes and their implications.

Change control is a proactive approach to project management that helps teams adapt to evolving circumstances while maintaining control over project parameters. It ensures that changes are carefully considered, approved by the appropriate parties, and implemented to align with project objectives. This structured process contributes to project success by preventing unmanaged changes that can lead to scope creep and project instability.

What are the Examples of Change Control Processes?

Examples of Change Control Processes:

- Software Development: In software development, a change control process may involve requests for modifying code, adding new features, or addressing bugs. Changes are typically submitted, assessed for impact, and, if approved, implemented in subsequent releases.

- Construction Project: In construction, changes to project plans, specifications, or materials may be requested. The change control process ensures that these modifications are thoroughly evaluated, approved, and communicated to the project team.

- Manufacturing: In manufacturing , changes to production processes, materials, or equipment may be proposed. The change control process ensures that these changes are assessed for their impact on product quality, and, if approved, implemented with proper documentation.

Example of Change Control in Project Management:

Imagine a construction project where the client requests a change in the design of a building's facade. The change control process would involve assessing the impact on the project timeline, budget, and other parameters. The change would be implemented if approved, and project plans would be updated accordingly.

When to use a Change Control Process?

A Change Control Process should be used in various scenarios to manage modifications to a project, product, or system in a structured and controlled manner. Here are some key situations when it is appropriate to employ a Change Control Process:

Changes in Project Scope

When there is a proposed alteration to the project scope, including additions, removals, or modifications to project deliverables.

Timeline Adjustments

When there is a need to change project timelines, deadlines, or milestones due to unforeseen circumstances or evolving project requirements.

Budgetary Changes

When there are adjustments to the project budget, including changes in resource allocation, funding, or financial constraints.

Quality Modifications

When changes are proposed that may impact the quality of the final product or service, ensuring that quality standards are maintained or improved.

Risk Mitigation

When there is a need to address identified risks or mitigate potential issues that could affect the project's success.

Stakeholder Requests

When stakeholders, clients, or end-users request modifications to the project that were not initially included in the plan.

Regulatory Compliance

When changes are required to ensure compliance with new regulations or standards affecting the project.

Technology or Process Changes

When there are proposed alterations to the technology, tools, or processes used in the project or organization.

Environmental Factors

When external factors such as market conditions, industry trends, or geopolitical events necessitate adjustments to the project.

Error Correction

When errors or issues are identified during project execution, corrections or modifications are needed to rectify these issues.

Client Feedback

When clients provide feedback or request changes based on evolving needs or preferences.

Resource Constraints or Availability

When there are changes in resource availability or constraints that necessitate adjustments to the project plan.

Customer Success

The Role of Change Management in Digital Transformation

Why Change Control is Important in GMP?

Change control is of paramount importance in Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) as it ensures the systematic management of modifications to processes, equipment, facilities, and systems within the pharmaceutical and medical device industries . Strict adherence to GMP principles is vital for consistently producing high-quality and safe products. Change control is critical because any manufacturing process or procedure alterations can significantly impact product quality, safety, and efficacy. By implementing a robust change control process, organizations in GMP-regulated industries can thoroughly assess proposed changes, identify potential risks, and ensure that modifications align with established quality standards. This systematic approach minimizes the likelihood of unintended consequences, deviations from regulatory requirements, and compromises in product quality.

Additionally, change control in GMP facilitates proper documentation, traceability, and transparency, all of which are essential for regulatory compliance and maintaining the integrity of the manufacturing process. Effective change control in GMP ultimately safeguards product quality, regulatory compliance, and patient safety throughout the product lifecycle.

Why do you Need a Change Request Form?

A Change Request Form is needed to formalize and document proposed changes. It provides a structured format for capturing essential details such as the nature of the change, reasons for the change, potential impacts, and the individuals responsible for the request. This form serves as a starting point for the change control process.

What are the Types of Change Request Forms?

There are various types of Change Request Forms, and the specific type used depends on the nature of the change. Examples include:

Scope Change Request Form

Used for changes affecting project scope.

Schedule Change Request Form

Used for changes impacting project timelines.

Budget Change Request Form

Used for changes affecting project budget.

Quality Change Request Form

Used for product or service quality changes.

These forms help standardize the information captured during the change request initiation, making assessing and managing changes easier.

ComplianceQuest delivers!

I’ve been using ComplianceQuest (CQ) for about 9 months and am extremely pleased with the product, the implementation team and ongoing support.

I selected CQ for a number of reasons. Functionality and a simple user interface were key requirements. CQ has all the functionality needed in support of a global QMS. Implementation includes; Document control, change order, personnel training, NC/CAPA, equipment management, supplier management, audit management, and customer complaints all on a single platform. As a small biologics company it was critical to find a single solution to meet our GMP quality system requirements. We wanted a cloud-based system, that would be quick to implement, that could be expanded globally and in other languages, all for a reasonable price. The user interface – it is exactly what I was hoping for. I constantly hear the staff saying, “I love CQ, it’s so straightforward to use”.

Donna Matuizek, Sr. Director Quality

What is a Change Control Policy?

A Change Control Policy is a set of documented guidelines and procedures that an organization follows to manage and control changes to its systems, processes, projects, or other regulated entities. A Change Control Policy aims to ensure that changes are implemented in a planned and systematic manner, minimizing the potential for disruptions, errors, or negative impacts on the organization's operations. It is a critical component of quality management and is often associated with IT, software development, and project management processes.

Here is a basic change control policy template:

The purpose of this Change Control Policy is to establish guidelines and procedures for managing and controlling changes to [organization's name] systems, processes, and projects to ensure the integrity, stability, and reliability of our operations.

This policy applies to all changes, including but not limited to, hardware, software, procedures, documentation, and organizational structure, that may impact the company.

Change Request Submission

All proposed changes must be submitted through the designated Change Request form. The form should include details such as the nature of the change, the reason for the change, potential impacts, and the proposed implementation plan.

Change Evaluation

The Change Control Board (CCB) will evaluate the proposed changes. The CCB will assess the change's impact, risks, and benefits before approval.

Approved changes will be documented, and stakeholders will be informed. The CCB will ensure that necessary resources are allocated to implement approved changes.

Changes will be implemented according to an approved plan. A rollback plan should be in place if unexpected issues arise during implementation.

Documentation

Comprehensive documentation of all changes, including reasons, approvals, and implementation details, will be maintained.

Communication

Effective communication will be maintained throughout the change process to inform stakeholders of progress and potential impacts.

Monitoring and Review

The effectiveness of implemented changes will be monitored, and a post-implementation review will be conducted to identify lessons learned and areas for improvement.

Roles and Responsibilities

Define the roles and responsibilities of individuals involved in the change control process, including the Change Control Board, change initiators, and those responsible for implementation.

Revision History

This policy will be periodically reviewed and updated as necessary. A revision history will be maintained.

What is the Change Control Process Template?

A Change Control Process Template is a structured and predefined document that outlines the steps and procedures to be followed when managing changes within a project, system, or process. This template serves as a guide to ensure that changes are systematically evaluated, approved, and implemented in a controlled and organized manner. The specific contents of a Change Control Process Template may vary, but typically, it includes the following key elements:

Change Request Identification

Clearly defines the process for initiating a change request, including information such as the requester's details, a description, and the reason for the proposed modification.

Change Request Evaluation

Outlines the criteria and considerations for evaluating the impact and feasibility of the proposed change. This may involve assessing the potential effects on scope, schedule, budget, and other relevant factors.

Change Approval Workflow

Defines the workflow for obtaining approvals at different levels. This includes identifying the individuals or groups responsible for reviewing and approving or rejecting the change request.

Documentation Requirements

Specifies the documentation needed to support the change control process. This may include updated project plans, revised requirements, and other relevant documentation.

Implementation Plan

Details the steps to implement the approved change. It may include instructions for updating documentation, notifying stakeholders, and conducting testing, among other activities.

Communication Plan

Outlines how communication about the change will be managed. This includes informing relevant stakeholders, team members, and other parties affected by the change.

Monitoring and Reporting

Describes the mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of the change, tracking its progress, and reporting status updates to relevant parties.

Change Closure

Specifies the criteria for closing a change request, ensuring that all necessary documentation is updated and stakeholders are notified of the successful implementation.

Clearly define the roles and responsibilities of individuals involved in the change control process. This ensures accountability and clarity in decision-making.

References and Attachments

Provides relevant references, templates, or attachments supporting the change control process.

A Change Control Process Template serves as a standardized tool for managing changes efficiently and maintaining control over project or process modifications. It helps ensure that changes are thoroughly evaluated, approved by the appropriate stakeholders, and implemented in a manner that minimizes disruptions and risks. Organizations often customize these templates to align with their specific processes and requirements.

ISO and FDA Change Control Guidance

- ISO 13485 and ISO 9000 standard

ISO 13485 and ISO 9000 are international standards that guide quality management systems in different industries. ISO 13485 focuses on the medical device industry , while ISO 9000 is a more general standard applicable to various sectors.

In the context of the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) regulations for medical devices, 820.30, 820.40, and 820.70 correspond to specific sections within Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 820, which is commonly known as the Quality System Regulation (QSR) for medical devices. These sections are part of the requirements outlined by the FDA for manufacturers to ensure the quality and safety of medical devices.

- 820.30 - Design Controls: This section outlines the requirements for design controls in developing medical devices. It includes design and development planning processes, design input, design output, design verification, design validation, design transfer, and design changes. The objective is to ensure that medical devices are designed and developed systematically and controlled to meet specified requirements.

- 820.40 - Document Controls: Document controls are crucial for maintaining an organized and controlled documentation system. This section specifies document approval, distribution, maintenance, and change requirements. It ensures that all relevant documents, including procedures and specifications, are managed effectively throughout their lifecycle.

- 820.70 - Production and Process Controls: Production and process controls are essential to ensure the consistency and quality of medical devices during manufacturing. This section outlines requirements for process validation, control of production processes, inspection, and testing. It focuses on controlling various production aspects to meet quality standards consistently.

Empower your team and drive success with our Change Control – harness the power of seamless transitions and risk mitigation today!

Quality-centric companies rely on cq qms.

Related Insights

Beyond Compliance: A Journey to FDA Inspection Mastery in Pharmaceuticals!

FDA inspections aren't just routine checks – they're the linchpin of pharmaceutical success. FDA inspections directly impact public health and company credibility. Understanding…

In today’s competitive environment, product companies including those in regulated…

Don’t Slip Back into Old Ways: Streamlining Change with Effective Document and Training Management

Adapting to changes, evolving, and being agile have become essential…

5 Best Practices for Managing Change in a Remote Workforce

Quality management systems need continuous monitoring and improvements to become…

Connect with a CQ Expert

Learn about all features of our Product, Quality, Safety, and Supplier suites. Please fill the form below to access our comprehensive demo video.

Please confirm your details

By submitting this form you agree that we can store and process your personal data as per our Privacy Statement. We will never sell your personal information to any third party.

In Need of Smarter Ways Forward? Get in Touch.

Got questions we can help.

Chat with a CQ expert, we will answer all your questions.

- Utility Menu

Risk Management & Audit Services

Change control.

Change Control is the process that management uses to identify, document and authorize changes to an IT environment. It minimizes the likelihood of disruptions, unauthorized alterations and errors. The change control procedures should be designed with the size and complexity of the environment in mind. For example, applications that are complex, maintained by large IT Staffs or represent high risks require more formalized and more extensive processes than simple applications maintained by a single IT person. In all cases there should be clear identification of who is responsible for the change control process.

A change control process should consider the following elements:

- Change Request Initiation and Control - Requests for changes should be standardized and subject to management review. Changes should be categorized and prioritized and specific procedures should be in place to handle urgent matters. Change requestors should be kept informed about the status of their request.

- Impact Assessment - A procedure should be in place to ensure that all requests for change are assessed in a structured way for all possible impacts on the operational system and its functionality.

- Control and documentation of Changes - Changes to production systems should be made only by authorized individuals in a controlled manner. Where possible a process for rolling back to the previous version should be identified. It is also important to document what changes have been made. At a minimum a change log should be maintained that includes a brief functional description of the change; date the change was implemented; who made the change; who authorized the change (if multiple people can authorize changes); and what technical elements were affected by the change.

- Documentation and Procedures - The change process should include provisions that whenever system changes are implemented, the associated documentation and procedures are updated accordingly.

- Authorized Maintenance - Staff maintaining systems should have specific assignments and their work monitored as required. In addition, their system access rights should be controlled to avoid risks of unauthorized access to production environments.

- Testing and User signoff - Software is thoroughly tested, not only for the change itself but also for impact on elements not modified.

- Consider developing a standard suite of tests for your application as well as creating a separate test environment.

- The standard test suite will help identify if core elements of an application were inadvertently affected. Maintaining this suite will make it less likely you will forget to test some feature in the future. The separate test environment will minimize disruptions to the production environment. Another important aspect of testing is that you test with transactions for which you know the correct results. Business owners of the systems should be responsible for signing off and approving changes being made.

- Testing Environment - Ideally systems should have at least three separate environments for development, testing and production. The test and production environments should be as similar as possible, with the possible exception of size. If cost prohibits having three environments, testing and development could take place in the same environment; but development activity would need to be closely managed (stopped) during acceptance testing. In no case should untested code or development be in a production environment.

- Version Control - Control should be placed on production source code to ensure that only the latest version is being updated. Otherwise previous changes may be inadvertently lost when a new change is moved into production. Version control may also help in being able to effectively back out of a change that has unintended side affects.

- Emergency Changes - Emergency situations may occur that requires some of the program change controls to be overridden such as granting programmers access to production. However, at least a verbal authorization should be obtained and the change should be documented as soon as possible.

- Distribution of Software - As a change is implemented, it is important that all components of the change are installed in the correct locations and in a timely manner.

- Hardware and System Software Changes - Changes to hardware and system software should also be tested and authorized before being applied to the production environment. They should also be documented in the change log.

If a vendor supplies patches, they should be reviewed and assessed for applicability and potential impact to determine whether their fixes are required by the system.

Get started

- Project management

- CRM and Sales

- Work management

- Product development life cycle

- Comparisons

- Construction management

- monday.com updates

What is change control management?

In some of our other posts on the monday.com blog, we’ve discussed the idea of crisis management.

Viewed a certain way, a crisis is really just a time of rapid change.

What if a company were to have a “crisis” on purpose?

Suppose they knew their infrastructure was outdated, and in need of a radical update?

It wouldn’t be easy. Without careful management, a controlled crisis like that could easily spiral into a regular crisis.

But there’s a way to ensure that big changes don’t derail your entire organization.

It’s called change control management — and the monday.com Work OS can help you pull it off.

This article will explain what change control management is, how it works, and how you can benefit.

Change control means that you pre-emptively establish processes to make any changes to your project, infrastructure, or organization.

Before we keep going, let’s sort out a point of frequent confusion: change control and change management are not the same thing.

Change management is the act of dealing with changes outside of your control. A change manager might be hired to guide an organization through a time of upheaval in the industry or the world.

Change management can also refer to how companies find a new normal after a major internal change.

Change control is different.

Let’s use an example to define change control in detail. Suppose you’re working on a SaaS platform that helps small business owners order inventory.

Your work is mainly in e-commerce but, one day, a new order comes in from the head of product: instead of just being a store, they want users to be able to bank money in the product as well.

The product head doesn’t work on your team, so your project manager is the first to learn about the proposed change. The product head recognizes that this will be a major scope change, but says it comes from user research.

Without a project change control process, your project manager has 2 options here.

1. They can refuse to make the change, causing a rift within the company and potentially missing out on customers who asked for the new features,

2. They can accept the change and ask you to start work on it immediately, at the risk of throwing the whole development schedule into confusion.

As you can see, neither option is great. But there’s a third choice.

3. They can run the project change through a thorough change control system and decide how to implement it in a way that minimizes impact and maximizes return.

In the bad scenario, say your team lead picks #2. You’re suddenly thrust into a project with a scope that doesn’t match what you’ve been working toward for months.

You make changes without understanding the consequences and, soon, you can’t get the product back to where it was when you started.

In the best scenario, where a change control process exists, any potential consequences will have been mapped out and understood ahead of time. If a change needs to be reversed later, there’s a clear path back to the starting point.

So how do you get that process in place?

Get started with monday.com

By following the steps in the next section.

How do you manage the change control process?

A good change control process needs to flow through several phases.

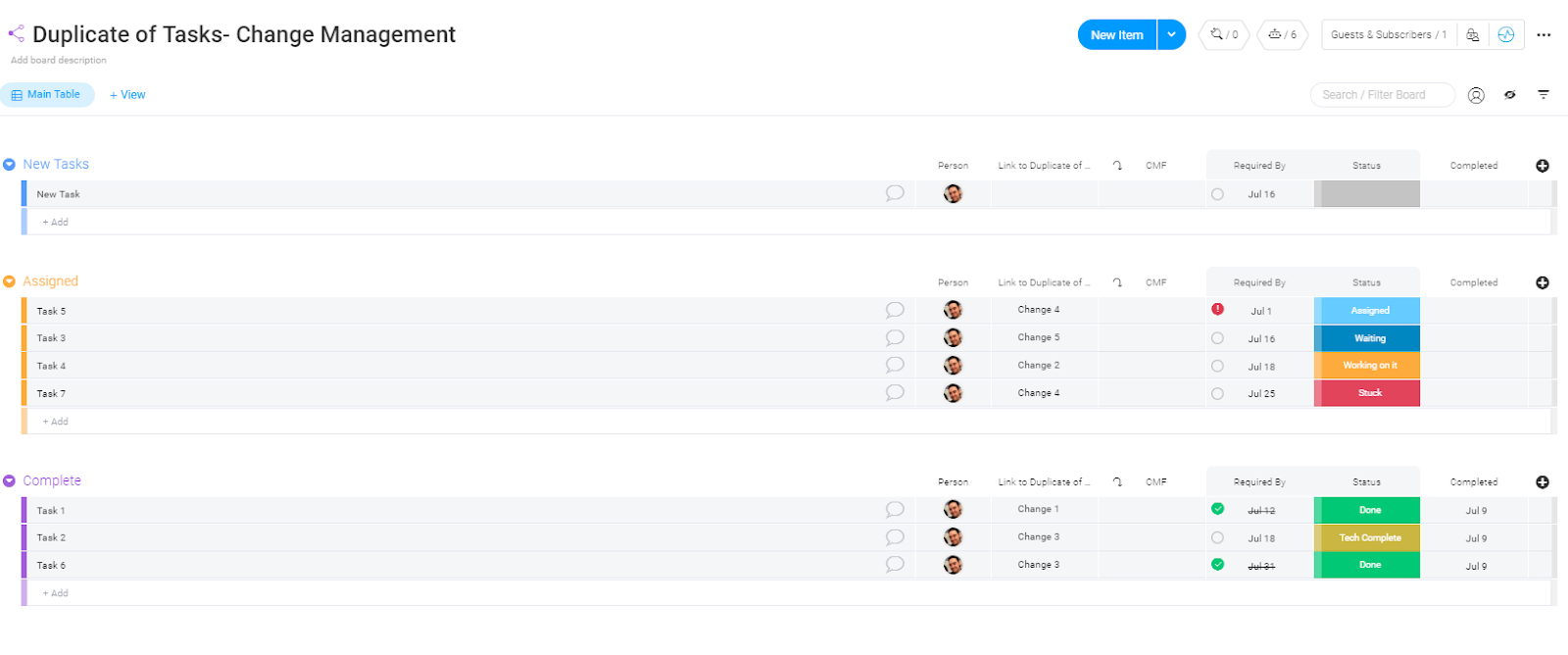

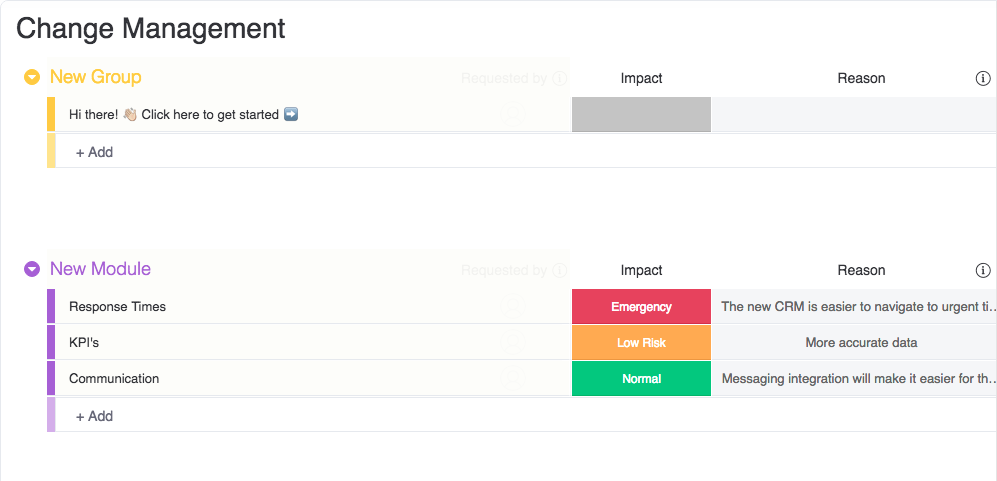

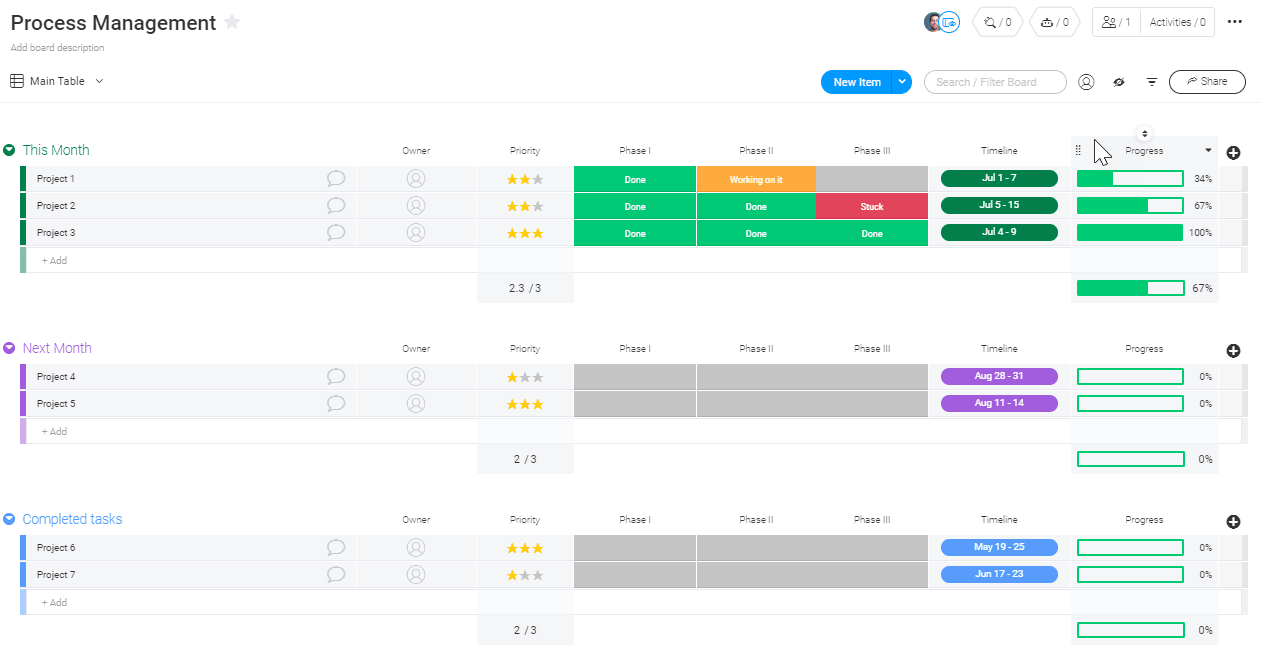

This screenshot demonstrates what a change control management tracker can look like (yes, it’s ours — that’s the change management use case for the monday.com Work OS).

As you can see, it’s a lot like how any other task gets moved through the implementation process.

First, someone submits an official change request form. As a minimum, this should define the change, the reason for the change, and how long they expect it to take.

Next, somebody needs to review the change request and make a decision about whether, when, and how to implement it. This is the critical point: at a minimum, the change request review needs to include the four elements below.

1. Risk assessment

In your company’s system, everything is connected. So any major change carries some risk.

However, failing to act on opportunities for positive change bears risks of its own.

That’s why any change control process must involve a risk analysis. Following standard risk management procedures, weigh the risks and rewards of making the change vs. the risks and rewards of doing nothing.

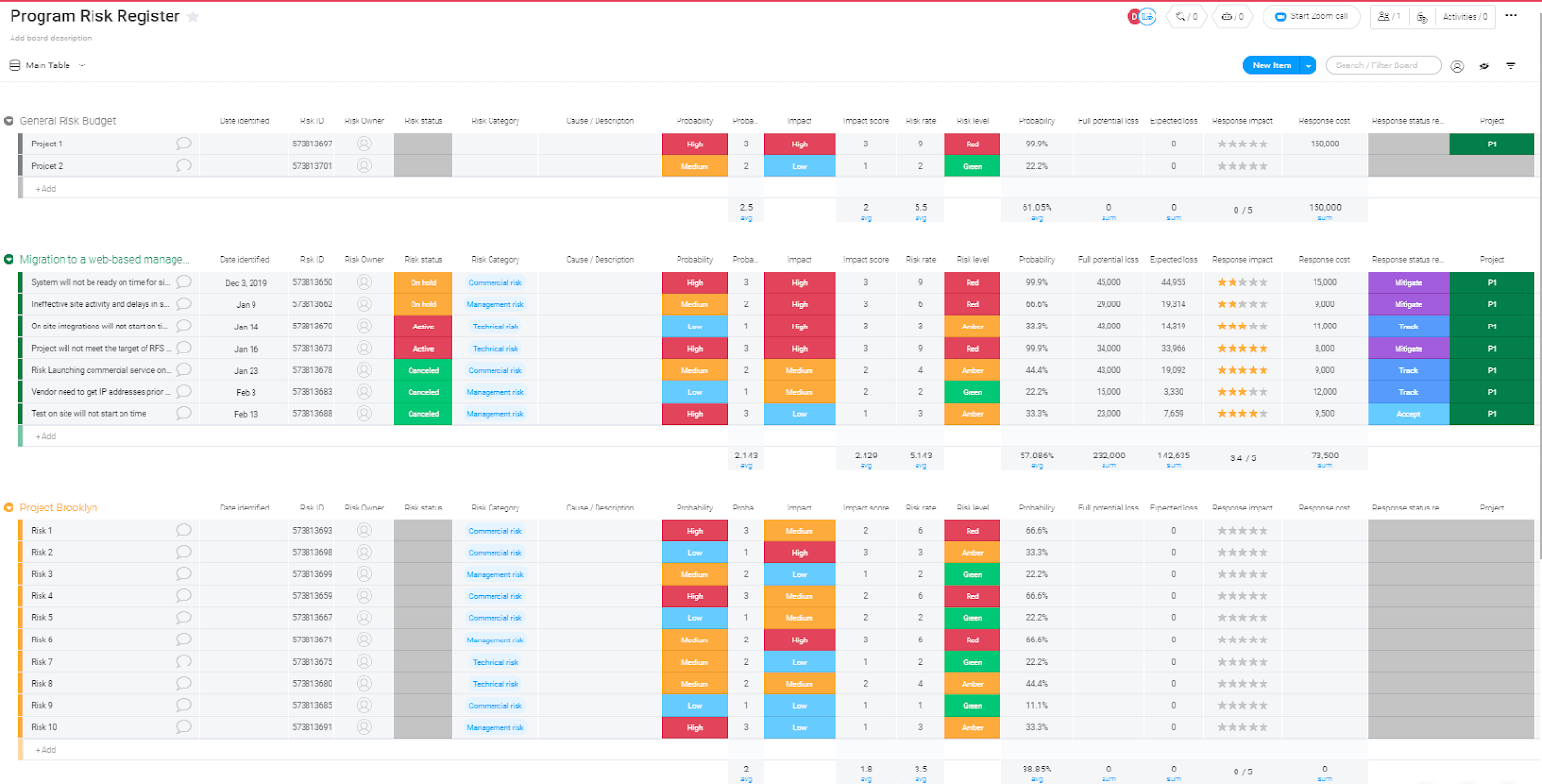

The monday.com program risk register template is our favorite example (I mean, we did invent it).

Since no two organizations face quite the same sorts of risk, we made it so you can customize this table by adding new columns.

By keeping track of risk, you can evaluate each change to see whether it’s better to press forward or play it safe for now.

2. Backout plan

Risk analysis is important, but you’ll never be able to foresee everything that could go wrong.

It’s rare, but possible, that you’ll commit to a change that’s too great for your project to bear.

In our example, turning your e-commerce app into a banking platform might mean you’ll make it to market too late.

In that case, you’ll have to activate your backout plan, and get back to basics so you can ship faster.

A backout plan means that you never embark on a change without understanding how you could return to the pre-change state on short notice.

Tracking your changes closely with a change management template (like the one above from monday.com) makes detailed backout plans a breeze.

3. Defined staff roles

Remember how, at the beginning of this post, we defined changes as controlled crises?

In a crisis situation, nothing is more important than clearly laying out jobs for every member of your team.

The same is true for change control. It’s all part of building a uniform process for rigorously vetting every change.

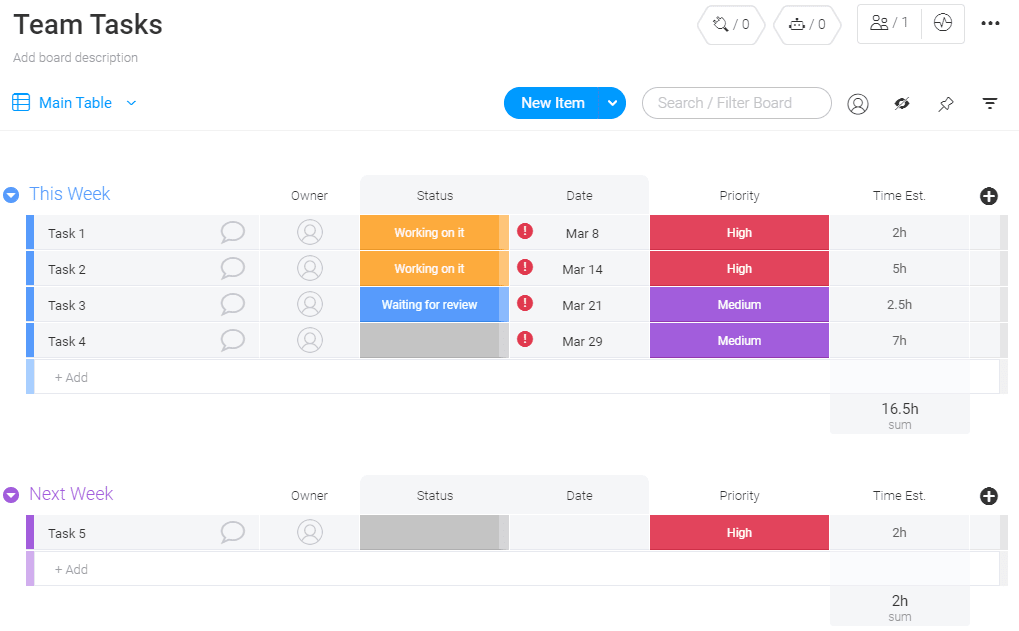

You’ll need to designate at least the following people (these can overlap):

- Someone to read change requests

- Someone to conduct risk analysis

- Someone to communicate with outside stakeholders

- Someone responsible for final approval

Use the monday.com team task management template to keep all of them straight.

4. Documentation

The change you’re dealing with at the moment is very unlikely to be the last one.

Changes will come in the future, and they might need to build on what happened during prior periods of change. That requires in-depth knowledge (particularly if something went wrong).

In change control, document everything. Every initial change request should be submitted in a standardized document format. Same with risk evaluations, approvals, denials, and requests for further information.

On top of that, the entire change log should be made available to every stakeholder both during, and after, the change control process.

You guessed it: there’s a monday.com template for that.

Our process management template lets you share links to documentation for every stage of the change control pipeline. Even people outside your company will find it easy to get what they need.

How does monday.com help with change control?

monday.com is a Work OS.

Through user-friendly templates and integrations, it helps make your workflows…y’know, work.

What does that mean for change control?

As you’ve seen above, a comprehensive change control plan has a lot of moving parts.

You need to evaluate several options in-depth, calculate forecasts for the future, and stay in communication with everyone the whole time.

It’s going to go far better if you have all your apps working together, and all your important information visible in one place. That’s where change control software can help.

Change control helps you plan change, not panic

Change control is just a fancy word for making sure change is intentional, rather than forced on your project team and company from the outside.

It’s about active change, since that almost always works out better than reactive change.

Nobody knows better than you what kind of challenges you’re likely to face over the lifetime of your project.

We figure the best thing we can do for you is open up the monday.com templates library, so you can start building your perfect change control plan.

Thanks for reading, and never forget to embrace change!

- Project change management

Send this article to someone who’d like it.

- Product overview

- All features

- App integrations

CAPABILITIES

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields

- Status updates

- goal icon Goals and reporting

- Reporting dashboards

- workflow icon Workflows and automation

- portfolio icon Resource management

- Time tracking

- my-task icon Admin and security

- Admin console

- asana-intelligence icon Asana Intelligence

- list icon Personal

- premium icon Starter

- briefcase icon Advanced

- Goal management

- Organizational planning

- Campaign management

- Creative production

- Content calendars

- Marketing strategic planning

- Resource planning

- Project intake

- Product launches

- Employee onboarding

- View all uses arrow-right icon

- Project plans

- Team goals & objectives

- Team continuity

- Meeting agenda

- View all templates arrow-right icon

- Work management resources Discover best practices, watch webinars, get insights

- What's new Learn about the latest and greatest from Asana

- Customer stories See how the world's best organizations drive work innovation with Asana

- Help Center Get lots of tips, tricks, and advice to get the most from Asana

- Asana Academy Sign up for interactive courses and webinars to learn Asana

- Developers Learn more about building apps on the Asana platform

- Community programs Connect with and learn from Asana customers around the world

- Events Find out about upcoming events near you

- Partners Learn more about our partner programs

- Support Need help? Contact the Asana support team

- Asana for nonprofits Get more information on our nonprofit discount program, and apply.

Featured Reads

- Project management |

- What is a change control process and ho ...

What is a change control process and how do you use it?

A change control process is a way for project managers to submit requests to stakeholders for review, that are then approved or denied. It’s an important process to help manage large projects with multiple moving parts.

The change control process is essential for large initiatives where many teammates work cross-departmentally. Let’s dive into the process and tangible examples to help you implement a change control procedure of your own.

What does change control process mean?

Change control is a process used to manage change requests for projects and big initiatives. It’s part of a change management plan, which defines the roles for managing change within a team or company. While there are many parts to a change process, the easiest way to think about it is that it involves creating a change log where you’ll track project change requests.

In most cases, any stakeholder will be able to request a change. A request could be as small as a slight edit to the project schedule or as large as a new deliverable. It’s important to keep in mind that not all requests will be approved, as it’s up to key stakeholders to approve or deny change requests.

Since the change control process has many moving parts and differs from company to company, it’s useful to implement tools that can help the lifecycle process flow smoothly. Tools such as workflow management software can help you manage work and communication in one place.

Change control vs. change management

Confused by the difference between change control and change management? We don't blame you. There are many differences between change control and a change management plan . Change control is just one of the many pieces of a change management strategy.

Change control: A change control process is important for any organization to have, and can help the flow of information when it comes to project changes. A successful process should define success metrics, organize your workflow, enable teams to communicate, and set your team up for future success.

Change management: A change management plan consists of coordinating budget, schedule, communication, and resources. So while a change control process consists of a formal document that outlines a request for change and the impact of the change, change management is the overarching plan.

As you can see, a change control process is just one small part of a larger change management plan. So while related, the two terms are different.

What are the benefits of a change control process?

Implementing a change control process can help organize your team with the support of organization software and efficiency around project deliverables and due dates. It’s also crucial when considering the consequences of change that isn’t managed effectively.

A change management process can help you execute a resource management plan or other work management goals. Here are some additional benefits of implementing a change control process.

Increased productivity

A change control process will eliminate confusion around project deliverables and allow the focus to be on executing rather than collecting information. This results in increased productivity and efficiency, especially with the help of productivity software .

Without a process in place, productivity can suffer due to time spent on work about work. With limited bandwidth available for the most important work, over one-quarter (26%) of deadlines are missed each week.

Effective communication

Properly documenting change can help alleviate communication issues. When goals and objectives are clearly defined, team communication can flourish. Keep in mind, a change control process won’t fix all communication issues. It may be helpful to also incorporate work management software to keep communication about projects in one place.

A change control process can then also be shared with executive stakeholders in order to easily provide context for change requests.

Better teamwork and collaboration

Not only is effective communication a benefit in its own right, but it can also help improve collaboration. With clear communication on project changes, it’s easier to collaborate and work together.

For example, when changes are clearly communicated the first time around, stakeholders have more time to focus on creativity and teamwork. Without effective communication, stakeholders are forced to spend time piecing information together instead of working creatively with team members.

Want to enhance collaboration even further? Pair your change control process with task management software to set your team up for success.

The five steps of a change control process

Similar to the five project management phases , there are five key steps when it comes to creating a change control process. Though some processes differ slightly, they all contain a few key elements. From initiation to implementation, each one of these basic steps helps change requests move efficiently through the pipeline and prevent unnecessary changes.

Some prefer to view the procedure in a change control process flow, which can be easier to visualize. No matter how you choose to look at it, the outcome will be a finalized decision on whether a change request is approved or denied.

Let’s dive into the five steps that make an effective change control process and what’s included in each.

1. Change request initiation

In the initiation phase of the change control process, a change is requested. There are numerous reasons why you might request a change. For example, a creative deliverable is taking longer than anticipated. A request would then be made to adjust the deliverable due date. While a request may be more likely to come from a stakeholder or project lead, a proposed change can be requested by anyone.

A team member who wishes to make a request should submit one via a change request form. As the project manager, you should store the change log in a place that’s easy to find and everyone has access to.

Once the request form has been filled out, you will update the change log with a name, brief description, and any other details you see fit, such as the date and name of the requester. The log is a record of all project changes, which can be beneficial for managing multiple projects that span many months.

Here’s an example of various fields you might include in a change request form.

Project name

Request description

Requested by

Change owner

Impact of change

The fields you include will depend on how thorough you want your change log to be and the type of changes you come across.

2. Change request assessment

Once the request has been filled out and the initial form has been submitted and approved, the request will then be assessed. This is different from the initial form submission since the assessment is when the actual change will be evaluated.

The assessment phase isn’t necessarily where a decision is made, but rather, reviewed for basic information. The information will likely be assessed by a project or department lead, who will review details such as the resources needed, the impact of the request, and who the request should be passed on to.

If the change request passes the initial assessment, it will then be passed on to the analysis phase where an actual decision will be made.

3. Change request analysis

The change impact analysis phase is where there will be a final decision on whether the request is approved or denied by the appropriate project lead. While you may also give input on the decision, it’s a good idea to get official approval from a leader as well. In some cases, there may even be a change control board that is in control of any change approvals.

An approved change request will require signoff, and from there, be communicated to the team and continue through the rest of the five-phase process. It should be documented on the change log and anywhere else project communication lives to ensure all project stakeholders understand the shifts needed.

If the change request is denied, it should also be documented on the change log. While communicating a denied request to the team isn’t necessary, it could be helpful in order to prevent confusion.

4. Change request implementation

If the change request is approved, the process will move on to the implementation phase. This is where you and the project stakeholders will work to make the project change.

Implementing a change will look different depending on what stage the project is in, but it usually consists of updating project timelines and deliverables, as well as informing the project team. Then the actual work can begin. It’s a good idea to evaluate the project scope to ensure any changes to the timeline won’t have a huge impact on projected goals.

It’s best to disseminate the request’s information in a shared workspace and the change log to ensure productivity isn’t lost by trying to look for new information. You may even want to send out a revised business case to cover all of your bases.

5. Change request closure

Once the request has been documented, disseminated, and implemented, the request is ready to be closed. While some teams don’t have a formal closure plan in place, it’s helpful to have one in order to store information in a place that all team members can reference in the future.

In the closing phase, any documentation, change logs, and communication should be stored in a shared space that can be accessed later on. You should also store the initial change form and any revised project plans you created along the way.

Once documents are in the appropriate place, you can close out any open tasks and work on successfully completing your project. Some project leads also host a post-mortem meeting before officially closing the project.

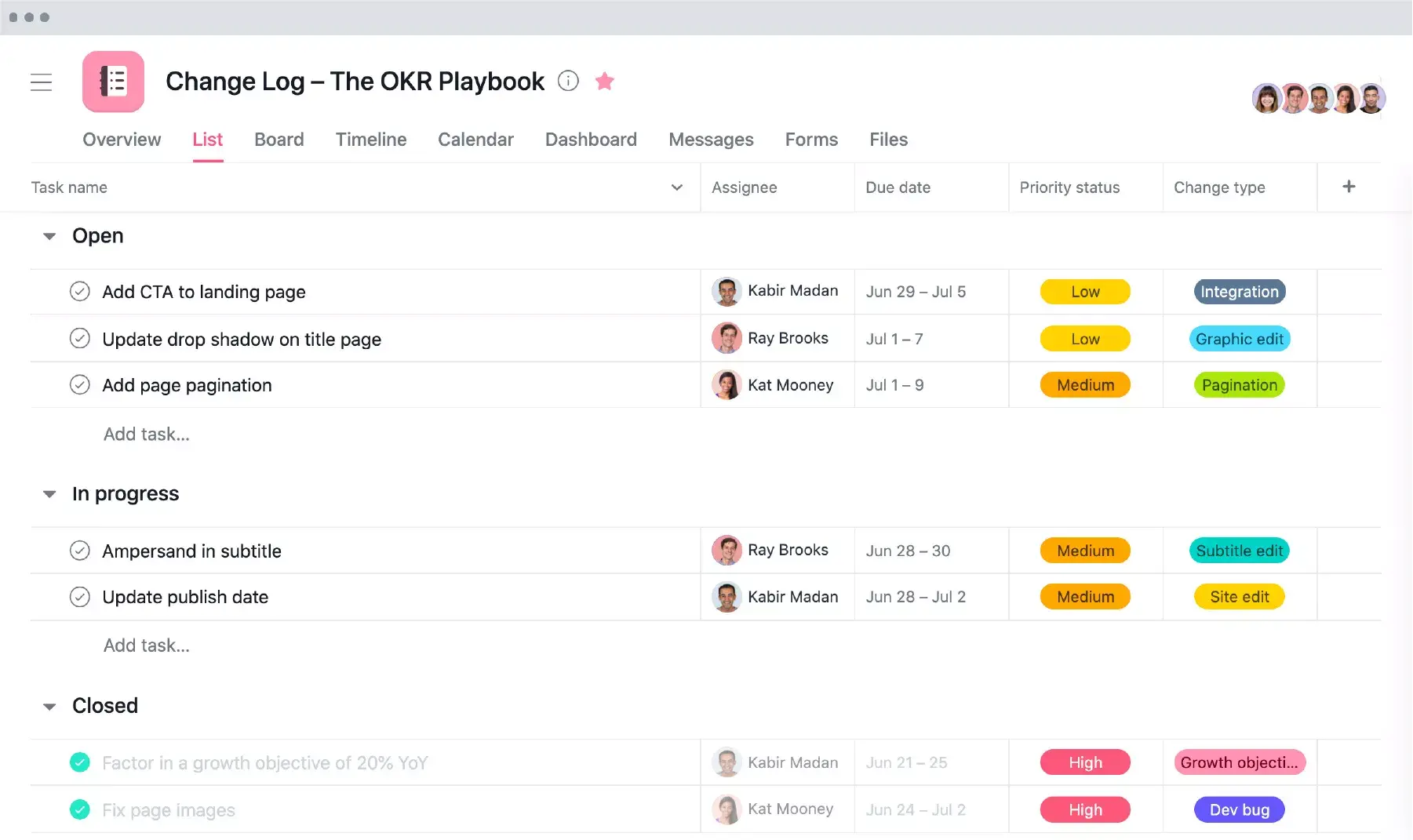

Change control process example

Now that you understand the five steps of a change control process, it’s time to put them into action. We’ve put together an example to give you a tangible place to start.

Before putting your own plan together, it’s important to evaluate your current processes and tools to ensure they’re right for your team. You may even want to create a business case or project plan to present to company stakeholders.

The entries you include in your change log may differ depending on the types of changes you frequently come across and how complicated the projects are. While complicated projects that span months may run into more change requests, smaller one-off projects may not need as detailed of a change log.

Here’s an example change log to give you an idea of what to include and how to format your own. This change control example includes:

Priority status

Progress status

Change type

This simple format is a great starting point for a change log, but you may choose to add additional fields depending on the complexity of your project.

To create your own change log, you can create a custom template or view our project templates gallery .

When to use a change control process

It’s a good idea to note when to use a change control management plan so you’re prepared when the time comes. There are many different kinds of change that you might come across, depending on any new initiatives and the tools in place.

Common changes might include requests to extend timelines, reorganization of information, or a change in the deliverables. Here are some additional instances where you may want to use a change control process.

Over scope: You may want to consider using this process when a project is going over scope, also known as scope creep .

Project inconsistencies: If you notice inconsistencies during a project, requesting a change can help you avoid having to rework deliverables later.

Steep goals: In some cases, OKRs may be out of reach and it’s a good idea to flag those issues before the project is complete.

New tools: If there are new processes or tools in place, change may be inevitable while you work out new issues during your first few projects.

Request your way to change

While changes are inevitable, the good news is a change doesn’t have to derail your next project. By implementing a change control process, you can ensure the project stays on track and communication is clear and effective. This will bolster productivity and lessen confusion about your project deliverables .

In the event that you do run into change, it’s reassuring to know that you have the right processes in place to handle the situation. When you have a change management plan ready to go, you can mitigate the negative impacts associated with a shift in strategy and continue to focus on delivering impact.

Related resources

What is a flowchart? Symbols and types explained

What are story points? Six easy steps to estimate work in Agile

How to choose project management software for your team

7 steps to complete a social media audit (with template)

How To Mitigate Change Management Risk

Change Strategists

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

So, you’ve decided to make some changes in your organization. That’s great! After all, change is necessary for growth and progress. However, before you jump headfirst into the deep end of change management, it’s important to recognize the potential risks involved.

To mitigate change management risk, it is important to have a clear plan in place before implementing any changes. This includes identifying potential risks and developing strategies to address them. Communication and training are also key components, as they can help employees understand the changes and how to adapt to them.

It is also important to have a process for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the changes, and making adjustments as needed.

Change management can be a tricky business. It’s not just about implementing new processes or technologies, but also about managing people’s emotions, expectations, and resistance to change. Without proper planning and execution, change can result in chaos, confusion, and even failure.

But fear not, dear reader! In this article, we will guide you through the process of mitigating change management risk, step-by-step.

From identifying potential risks to celebrating success, we’ll cover everything you need to know to ensure a smooth and successful transition.

So, let’s get started!

Identify Potential Risks

You need to start by looking for possible challenges that could come up in the process of change management. This is called risk assessment, and it involves identifying potential risks that may cause delays or failure of the project.

Some of the risks that should be considered during the assessment include employee resistance, lack of communication, inadequate training, and budget constraints.

Once you have identified the potential risks, you can then develop mitigation strategies to reduce the impact of these risks. For instance, to mitigate employee resistance, you can involve them in the change process by communicating the benefits of the change and providing them with adequate training.

To mitigate the lack of communication, you can establish clear communication channels and set up regular meetings to update stakeholders on the progress of the project.

In conclusion, identifying potential risks and developing mitigation strategies is crucial in mitigating change management risk. By doing so, you can ensure that the change process is smooth and successful, and that the project is completed within the set timeline and budget. Remember that risk assessment is an ongoing process, and it’s important to regularly review and update your mitigation strategies as the project progresses.

Develop a Change Management Plan

Crafting a solid plan is key to successfully navigating and adapting to any shifts in your organization. Change readiness is essential to ensure that your plan is effective and sustainable.

Assessing your team’s readiness for change will help you develop a plan that is tailored to their needs. To do this, consider conducting surveys, focus groups, or interviews to gain insights into how your team perceives the change, what they need to feel comfortable with it, and what challenges they anticipate. By taking these steps, you can ensure that your plan is well-informed and addresses any potential obstacles.

Stakeholder engagement is another crucial component of change management planning. Engaging stakeholders early on and throughout the change process can help you build buy-in and support for your plan. It can also help you identify potential resistance or challenges early on and address them before they become major roadblocks.

Consider involving stakeholders in planning, communicating, and implementing the change. This can include senior leaders, front-line employees, customers, and any other groups that may be impacted by the change. By engaging stakeholders in a meaningful way, you can ensure that your plan is well-informed, collaborative, and successful.

In summary, developing a change management plan requires careful consideration of change readiness and stakeholder engagement. Crafting a solid plan that is tailored to your team’s needs and involves stakeholders early on can help you mitigate risk and ensure long-term success. By investing time and effort in planning and engaging stakeholders, you can navigate change more effectively and build a stronger, more resilient organization.

Communicate Effectively

In this section, effectively communicating your change management plan is like a conductor leading an orchestra. Just as a conductor brings all the different instruments together in harmony towards a common goal, you must bring your team together towards a successful change implementation.

The importance of empathy and clarity cannot be overstated when it comes to effective communication. Empathy allows you to understand your team’s perspective and concerns, while clarity ensures that everyone is on the same page.

Building trust is crucial in any change management initiative, and effective communication is key to achieving it. Transparency and consistency are the building blocks of trust. Ensure that you communicate every step of the change process with transparency, keeping your team informed about what’s coming and what’s expected of them. Consistency in communication helps to establish trust, so maintain a regular cadence of communication with your team.

In summary, effective communication is vital to mitigate change management risk. Empathy and clarity are crucial components of effective communication, as is building trust through transparency and consistency. As you communicate your change management plan, remember that you’re the conductor leading your team towards a successful change initiative.

Build a Strong Team

Together, you’ll be assembling a team of skilled individuals who will work in harmony towards a common goal, much like a group of musicians in an orchestra. The success of your change management plan will depend on how effectively you build and lead your team.

To start, you should identify the key competencies required for your team and select individuals who have those skills. Once you have your team in place, it’s important to foster a culture of collaboration and communication.

To build a strong team, you can engage in team building activities that promote trust and open communication. This can be as simple as having regular team meetings or as elaborate as organizing a retreat or team-building workshop. The goal is to help your team members get to know each other better, understand their strengths and weaknesses, and develop a sense of camaraderie.

Additionally, it’s important to provide leadership development opportunities for your team members. This can include training, mentoring, and coaching to help them grow and develop their leadership skills.

In summary, building a strong team is essential to mitigating change management risk. By assembling a group of skilled individuals who work well together and providing leadership development opportunities, you can ensure that your team is equipped to handle any challenges that may arise during the change management process. Remember that team building is an ongoing process, so continue to foster a culture of collaboration and communication to maintain a high-performing team.

Monitor Progress

Monitoring progress is crucial to the success of your change management plan, so keep an eye on how things are going and adjust as needed. Set up regular feedback sessions with your team and stakeholders to ensure that everyone is on the same page. Use performance metrics to track progress and identify any areas that need improvement.

Stakeholder engagement is a critical component of change management, and regular feedback loops can help you keep your stakeholders informed and engaged. Make sure that you’re communicating with your stakeholders regularly and that you’re providing them with the information they need to understand the changes that are happening. Encourage feedback and be open to suggestions for improvement.

Using performance metrics to monitor progress is an effective way to ensure the success of your change management plan. By tracking key performance indicators, you can identify any areas that need improvement and make adjustments as needed. Regular feedback sessions with your team and stakeholders can also help you identify any issues early on and address them before they become major problems.

Remember that change management is an ongoing process, and monitoring progress is essential to ensuring that your plan is successful.

Anticipate and Address Resistance

Don’t let resistance hold you back – anticipate and address it head-on to ensure the success of your plan. Resistance is a natural part of change management, but it can also be a major obstacle.

To mitigate this risk, it’s important to have a clear understanding of the potential sources of resistance. This could include a fear of the unknown, a lack of understanding about the benefits of the change, or concerns about job security. Once you have identified these potential sources of resistance, you can develop targeted training strategies and communication plans to address them.

One effective strategy for mitigating resistance is to focus on leadership buy-in. If key leaders within the organization are on board with the change, they can help to create a culture that is supportive of the transition. This can include providing training and resources to help employees adapt to the change, as well as modeling the desired behaviors and attitudes.

By engaging these leaders early on in the process and making them part of the planning and implementation, you can help to build a coalition of support that can help to overcome resistance.

Another important aspect of addressing resistance is to be transparent and open to feedback. Employees are more likely to support a change if they feel that their concerns and opinions are being heard and valued. This means providing regular updates on the progress of the change, soliciting feedback from employees, and being willing to make adjustments as needed.

By creating a culture of openness and transparency, you can help to build trust and engagement, which can ultimately lead to a more successful change management process.

Manage Operational Disruptions

As you dive deeper into managing operational disruptions, it’s important to develop contingency plans to prepare for unexpected events. In doing so, you’ll be able to minimize disruptions and keep your business running smoothly.

Effective communication with customers and suppliers is also crucial. This will help maintain strong relationships and ensure that everyone is on the same page.

By taking a proactive approach and being prepared for potential disruptions, you can minimize their impact and keep your business moving forward.

Develop Contingency Plans

The key to successfully navigating unexpected obstacles is to have backup plans in place that are as solid as a rock. Developing contingency plans is a crucial step in mitigating change management risk. Here are three things to keep in mind when creating these plans:

Identify the potential risks: Start by conducting a thorough risk assessment to identify all possible risks that could disrupt your operations. This will help you develop contingency plans that address the most critical risks first.

Prioritize your response: Not all risks require the same level of response. Identify which risks are most likely to occur and which ones would have the greatest impact on your business. This will help you prioritize your response and allocate resources accordingly.

Test and refine your plans: Once you’ve developed your contingency plans, it’s important to test them regularly to ensure they’re effective and up-to-date. This will help you identify any weaknesses in your plans and refine them accordingly.