Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Factors influencing plagiarism in higher education: A comparison of German and Slovene students

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Personnel and Education, Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Maribor, Kranj, Slovenia

Roles Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia; School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing, China

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Economics and Law, Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences, Frankfurt, Germany

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Methodology, Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Maribor, Kranj, Slovenia

Roles Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft

Roles Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Eva Jereb,

- Matjaž Perc,

- Barbara Lämmlein,

- Janja Jerebic,

- Marko Urh,

- Iztok Podbregar,

- Polona Šprajc

- Published: August 10, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252

- Reader Comments

Over the past decades, plagiarism has been classified as a multi-layer phenomenon of dishonesty that occurs in higher education. A number of research papers have identified a host of factors such as gender, socialisation, efficiency gain, motivation for study, methodological uncertainties or easy access to electronic information via the Internet and new technologies, as reasons driving plagiarism. The paper at hand examines whether such factors are still effective and if there are any differences between German and Slovene students’ factors influencing plagiarism. A quantitative paper-and-pencil survey was carried out in Germany and Slovenia in 2017/2018 academic year, with a sample of 485 students from higher education institutions. The major findings of this research reveal that easy access to information-communication technologies and the Web is the main reason driving plagiarism. In that regard, there are no significant differences between German and Slovene students in terms of personal factors such as gender, motivation for study, and socialisation. In this sense, digitalisation and the Web outrank national borders.

Citation: Jereb E, Perc M, Lämmlein B, Jerebic J, Urh M, Podbregar I, et al. (2018) Factors influencing plagiarism in higher education: A comparison of German and Slovene students. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0202252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252

Editor: Andreas Wedrich, Medizinische Universitat Graz, AUSTRIA

Received: May 21, 2018; Accepted: July 6, 2018; Published: August 10, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Jereb et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: MP was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (Grant Nos. J1-7009 and P5-0027), http://www.arrs.gov.si/ . The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Many of those who teach in higher education have encountered the phenomenon of plagiarism as a form of dishonesty in the classroom. According to the Oxford English Dictionary online 2017, the term plagiarism is defined as ‘the practice of taking someone else's work or ideas and passing them off as one's own’. Perrin, Larkham and Culwin define plagiarism as the use of an author's words, ideas, reflections and thoughts without proper acknowledgment of the author [ 1 – 3 ]. Koul et al. define plagiarism as a form of cheating and theft since in cases of plagiarism one person takes credit for another person’s intellectual work [ 4 ]. According to Fishman, ‘Plagiarism occurs when someone: 1) uses words, ideas, or work products; 2) attributable to another identifiable person or source; 3) without attributing the work to the source from which it was obtained; 4) in a situation in which there is a legitimate expectation of original authorship; 5) in order to obtain some benefit, credit, or gain which need not be monetary’ [ 5 ]. But why do students use someone else's words or ideas and pass them on as their own? Which factors influence this behaviour? That is the main focus of our research, to discover the factors influencing plagiarism and see if there are any differences between German and Slovene students.

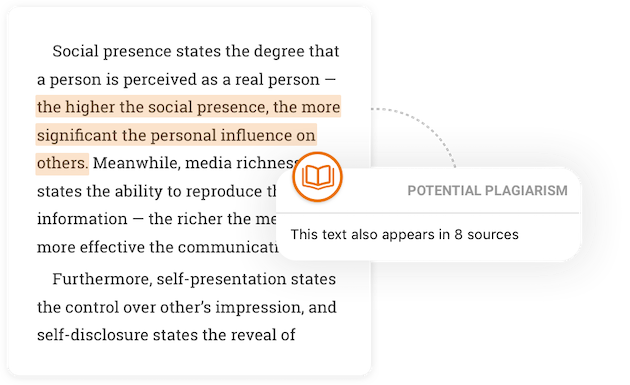

Koul et al. pointed out that particular circumstances or events should be considered in the definition of plagiarism since plagiarism may vary across cultures and societies [ 4 ]. Hall has described Eastern cultures (the Middle East, Asia, Africa, South America) and Western cultures (North America and much of Europe) using the idea of ‘context’, which refers to the framework, background, and surrounding circumstances in which an event takes place [ 6 ]. Western societies are generally ‘low context’ societies. In other words, people in Western societies play by external rules (e.g., honour codes against plagiarism), and decisions are based on logic, facts, and directness. Eastern societies are generally ‘high context’ societies, meaning that people in Eastern societies put strong emphasis on relational concerns, and decisions are based on personal relationships. Nisbett et al. have suggested that differences between Westerners and Easterners may arise from people being socialised into different worldviews, cognitive processes and habits of mind [ 7 ]. In Germany, there has been ongoing reflection on academic plagiarism and other dishonest research practices since the late 19th century [ 8 ]. However, according to Ruiperez and Garcia-Cabrero, in Germany, 2011 became a landmark year with the appearance of an extensive public debate about plagiarism—brought back into the limelight because of an investigation into the incumbent German Defence Minister’s doctoral thesis [ 9 ]. Aside from the numerous cases of plagiarism detected in academic work since 2011, several initiatives have enriched the debate on academic plagiarism. For example, the development of a consolidated cooperative textual research methodology using a specific Wiki called ‘VroniPlag’ has made Germany one of the most advanced European countries in terms of combating these practices. Similar to Germany, Slovenia has also paid increased attention to plagiarism in recent years. The debate about plagiarism became public after it was discovered that certain Slovene politicians had resorted to academic plagiarism. Today, universities in Slovenia use a variety of tools (Turnitin, plagiarism plug-ins for Moodle, plagiarisma.net, etc.) in order to detect plagiarism. The focus of this research is to investigate the factors influencing plagiarism and if there are any differences between Slovene and German students’ factors influencing plagiarising. The research questions (RQ) of the study were divided into three groups:

- RQ group 1: Which factors influence plagiarism in higher education?

- RQ group 2: Are there any differences between male and female students regarding factors influencing plagiarism? Are the factors influencing plagiarism connected with specific areas of study (technical sciences, social sciences, natural sciences)?

- RQ group 3: Does the students’ motivation affect their factors influencing plagiarism? Are there any differences between male and female students regarding this?

In addition, for all three research question groups, we also wanted to know if there were any differences between the German and Slovene students.

Theoretical background

Plagiarism is a highly complex phenomenon and, as such, it is likely that there is no single explanation for why individuals engage in plagiarist behaviours [ 10 ]. The situation is often complex and multi-dimensional, with no simple cause-and-effect link [ 11 ].

McCabe et al. noted that individual factors (e.g. gender, average grade, work ethic, self-esteem), institutional factors (e.g., faculty response to cheating, sanction threats, honour codes) and contextual factors (e.g., peer cheating behaviours, peer disapproval of cheating behaviours, perceived severity of penalties for cheating) influence cheating behaviour [ 12 ]. Giluk and Postlethwaite also related individual characteristics and situational factors to cheating—individual characteristics such as gender, age, ability, personality, and extracurricular involvement; and situational factors such as honour codes, penalties, and risk of detection [ 13 ]. The study of Jereb et al. also revealed that specific individual characteristics pertaining to men and women influence plagiarism [ 14 ]. Newstead et al. suggested that gender differences (plagiarism is more frequent among boys), age differences (plagiarism is more frequent among younger students), and academic performance differences (plagiarism is more frequent among lower performers) are specific factors for plagiarism [ 15 ]. Gerdeman stated that the following five student characteristic variables are frequently related to the incidence of dishonest behaviour: academic achievement, age, social activities, study major, and gender [ 16 ].

One of the factors influencing plagiarism could be that students do not have a clear understanding of what constitutes plagiarism and how it can be avoided [ 17 , 18 ]. According to Hansen, students don’t fully understand what constitutes plagiarism [ 19 ]. Park states genuine lack of understanding as one of the reasons for plagiarism. Some students plagiarise unintentionally, when they are not familiar with proper ways of quoting, paraphrasing, citing and referencing and/or when they are unclear about the meaning of ‘common knowledge’ and the expression ‘in their own words’ [ 11 ].

Furthermore, it is important to remember that, in our current day and age, information is easily accessed through new technologies. In addition, as Koul et al. have stated, the belief that we as people have greater ownership of information than we have paid for may influence attitudes towards plagiarism [ 4 ]. Many other authors have also stated that the Internet has increased the potential for plagiarism, since information is easily accessed through new technologies [ 14 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Indeed, the Internet grants easy access to an enormous amount of knowledge and learning materials. This provides an opportunity for students to easily cut, paste, download and plagiarise information [ 21 , 23 ]. Online resources are available 24/7 and enable a flood of information, which is also constantly updated. Given students' ease of access to both digital information and sophisticated digital technologies, several researchers have noted that students may be more likely to ignore academic ethics and to engage in plagiarism than would otherwise be the case [ 24 ].

In a study of the level of plagiarism in higher education, Tayraukham found that students with performance goals were more likely to indulge in plagiarism behaviours than students who wanted to achieve mastery of a particular subject [ 25 ]. Most of the students plagiarised in order to provide the right responses to study questions, with the ultimate goal of getting higher grades—rather than gaining expertise in their subjects of study. Anderman and Midgley observed that a relatively higher performance-oriented classroom climate increases cheating behaviour; while a higher mastery-oriented classroom climate decreases cheating behaviour [ 26 ]. Park also claimed that one of the reasons that students plagiarise is efficiency gain, that is, that students plagiarise in order to get a better grade and save time [ 11 ]. Songsriwittaya et al. stated that what motivates students to plagiarise is the goal of getting good grades and comparing their success with that of their peers [ 27 ]. The study of Ramzan et al. also revealed that the societal and family pressures of getting higher grades influence plagiarism [ 21 ]. Such pressures sometimes push students to indulge in unfair means such as plagiarism as a shortcut to performing better in exams or producing a certain number of publications. Engler et al. and Hard et al. tended to agree with this idea, stating that plagiarism arises out of social norms and peer relationships [ 28 , 29 ]. Park also stated that there are many calls on students’ time, including peer pressure for maintaining an active social life, commitment to college sports and performance activities, family responsibilities, and pressure to complete multiple work assignments in short amounts of time [ 11 ]. Šprajc et al. agreed that students are under an enormous amount of pressure from family, peers, and instructors, to compete for scholarships, admissions, and, of course, places in the job market [ 30 ]. This affects students’ time management and can lead to plagiarism. In addition to time pressures, Franklin-Stokes and Newstead found another six major reasons given by students to explain cheating behaviours: the desire to help a friend, a fear of failure, laziness, extenuating circumstances, the possibility of reaping a monetary reward, and because ‘everybody does it’ [ 31 ].

Another common reason for plagiarism is the poor preparation of lecture notes, which can lead to the inadequate referencing of texts [ 32 ]. Šprajc et al. found out that too many assignments given within a short time frame pushes students to plagiarise [ 30 ]. Poor explanations, bad teaching, and dissatisfaction with course content can also drive students to plagiarise. Park exposed students’ attitudes towards teachers and classes [ 11 ]. Some students cheat because they have negative attitudes towards assignments and tasks that teachers believe to have meaning but that they don’t [ 33 ]. Cheating tends to be more common in classes where the subject matter seems unimportant or uninteresting to students, or where the teacher seemed disinterested or permissive [ 16 ].

Park mentioned students’ academic skills (researching and writing skills, knowing how to cite, etc.) as another reason for plagiarism [ 11 ]. New students and international students whose first language is not English need to transition to the research culture by understanding the necessity of doing research, and the practice and skills required to do so, in order to avoid unintentional plagiarism [ 21 ]. According to Park to some students, plagiarism is a tangible way of showing dissent and expressing a lack of respect for authority [ 11 ]. Some students deny to themselves that they are cheating or find ways of legitimising their behaviour by passing the blame on to others. Other factors influencing plagiarising are temptation and opportunity. It is both easier and more tempting for students to plagiarise since information has become readily accessible with the Internet and Web search tools, making it faster and easier to find information and copy it. In addition, some people believe that since the Internet is free for all and a public domain, copying from the Internet requires no citation or acknowledgement of the source [ 34 ]. To some students, the benefits of plagiarising outweigh the risks, particularly if they think there is little or no chance of getting caught and there is little or no punishment if they are indeed caught [ 35 ].

One of the factors influencing plagiarism could be also higher institutions’ attitudes towards plagiarism, that is, whether they have clear policies regarding plagiarism and its consequences or not. The effective communication of policies, increased student awareness of penalties, and enforcement of these penalties tend to reduce dishonest behaviour [ 36 ]. Ramzan et al. [ 21 ] mentioned the research of Razera et al., who found that Swedish students and teachers need training to understand and avoid plagiarism [ 37 ]. In order to deal with plagiarism, teachers want and need a clear set of policies regarding detection tools, and extensive training in the use of detection software and systems. According to Ramzan et al., Dawson and Overfield determined that students are aware that plagiarism is bad but that they are not clear on what constitutes plagiarism and how to avoid it [ 21 , 38 ]. In Dawson and Overfield’s study, students required teachers to also observe the rules set up to avoid plagiarism and be consistently kept aware of plagiarism—in order to enforce the university’s resolve to control this academic misconduct.

According to this literature review and our experiences in higher education teaching, we determined that the following factors influence plagiarism: students’ individual factors, information-communication technologies (ICT) and the Web, regulation, students’ academic skills, teaching factors, different forms of pressure, student pride, and other reasons. The statements used in the instrument we developed, and the results of our research are presented in the following chapters.

Participants

The paper-and-pencil survey was carried out in the 2017/18 academic year at the University of Maribor in Slovenia and at the Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences in Germany. Students were verbally informed of the nature of the research and invited to freely participate. They were assured of anonymity. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research in Organizational Sciences at Faculty of Organizational Sciences University of Maribor.

A sample of 191 students from Slovenia (SLO) (99 males (51.8%) and 92 (48.2%) females) and 294 students from Germany (GER) (115 males (39.1%) and 171 (58.2%) females) participated in this study. Slovene students’ ages ranged from 19 to 36 years, with a mean of 21 years and 1 months ( M = 21 . 12 and SD = 1 . 770 ) and German students’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years, with a mean of 22 years and 10 months ( M = 22 . 84 and SD = 3 . 406 ). About half (49.2%) of the Slovene participants were social sciences students, 34.9% were technical sciences students, and 15.9% were natural sciences students. More than half (58.5%) of the German participants were social sciences students, 32% were technical sciences students and 2% were natural sciences students. More than half of the Slovene students (53.4%) attended blended learning, and 46.6% attended classic learning. The majority of German students (87.8%) attended classic learning, and 6.8% attended blended learning. More than half of the Slovene students (61.6%) were working at the time of the study, and 39.8% of all participants had scholarships. In addition, in Germany, more than half the students (65.0%) were working at the time of the study, but only 10.2% of all the German participants had scholarships. More than two thirds (68.9%) of the Slovene students were highly motivated for study and 31.1% less so; 32.6% of the students spend 2 or fewer hours per day on the Internet, 41.6% spend between 2 and 5 hours on the Internet, and 25.8% spend 5 or more hours on the Internet per day. Also, more than two thirds (73.1%) of the German students were highly motivated for study and 23.8% less so; 33.3% of the students spend 2 or fewer hours per day on the Internet, 32.3% spend between 2 and 5 hours on the Internet, and 27.9% spend 5 or more hours on the Internet per day. The general data can be seen in S1 Table .

The questionnaire contained closed questions referring to: (i) general/individual data (gender, age, area of study, method of study, working status, scholarship, motivation for study, average time spent on the internet), and factors influencing plagiarism (ii) ICT and Web, (iii) regulation, (iv) academic skills, (v) teaching factors, (vi) pressure, (vii) pride, (viii) other reasons. The items in the groups (ii) to (viii) used a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), with larger values indicating stronger orientation.

The statements used in the survey were as follows:

- 1.1 It is easy for me to copy/paste due to contemporary technology

- 1.2 I do not know how to cite electronic information

- 1.3 It is hard for me to keep track of information sources on the web

- 1.4 I can easily access research material using the Internet

- 1.5 Easy access to new technologies

- 1.6 I can easily translate information from other languages

- 1.7 I can easily combine information from multiple sources

- 1.8 It is easy to share documents, information, data

- 2.1 There is no teacher control on plagiarism

- 2.2 There is no faculty regulation against plagiarism

- 2.3 There is no university regulation against plagiarism

- 2.4 There are no penalties

- 2.5 There are no honour codes relating to plagiarism

- 2.6 There are no electronic systems of control

- 2.7 There is no systematic tracking of violators

- 2.8 I will not get caught

- 2.9 I am not aware of penalties

- 2.10 I do not understand the consequences

- 2.11 The penalties are minor

- 2.12 The gains are higher than the losses

- 3.1 I run out of time

- 3.2 I am unable to cope with the workload

- 3.3 I do not know how to cite

- 3.4 I do not know how to find research materials

- 3.5 I do not know how to research

- 3.6 My reading comprehension skills are weak

- 3.7 My writing skills are weak

- 3.8 I sometimes have difficulty expressing my own ideas

- 4.1 The tasks are too difficult

- 4.2 Poor explanation—bad teaching

- 4.3 Too many assignments in a short amount of time

- 4.4 Plagiarism is not explained

- 4.5 I am not satisfied with course content

- 4.6 Teachers do not care

- 4.7 Teachers do not read students' assignments

- 5.1 Family pressure

- 5.2 Peer pressure

- 5.3 Under stress

- 5.4 Faculty pressure

- 5.5 Money pressure

- 5.6 Afraid to fail

- 5.7 Job pressure

- 6.1 I do not want to look stupid in front of peers

- 6.2 I do not want to look stupid in front of my professor

- 6.3 I do not want to embarrass my family

- 6.4 I do not want to embarrass myself

- 6.5 I focus on how my competences will be judged relative to others

- 6.6 I am focused on learning according to self-set standards

- 6.7 I fear asking for help

- 6.8 My fear of performing poorly motivates me to plagiarise

- 6.9 Assigned academic work will not help me personally/professionally

- 7.1 I do not want to work hard

- 7.2 I do not want to learn anything, just pass

- 7.3 My work is not good enough

- 7.4 It is easier to plagiarise than to work

- 7.5 To get a better/higher mark (score)

All statistical tests were performed with SPSS at the significance level of 0.05. Parametric tests (Independent–Samples t-Test and One-Way ANOVA) were selected for normal and near-normal distributions of the responses. Nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney Test, Kruskal-Wallis Test, Friedman’s ANOVA) were used for significantly non-normal distributions. Chi-Square Test was used to investigate the independence between variables.

The average values for the groups (and standard deviations) of the responses referring to the factors influencing plagiarism can be seen in Table 1 (descriptive statistics for all statements can be seen in S2 Table ), shown separately for Slovene and German students. An Independent Samples t-test was conducted to obtain the average values of the responses, and thus evaluate for which statements these differed significantly between the Slovene and German students.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.t001

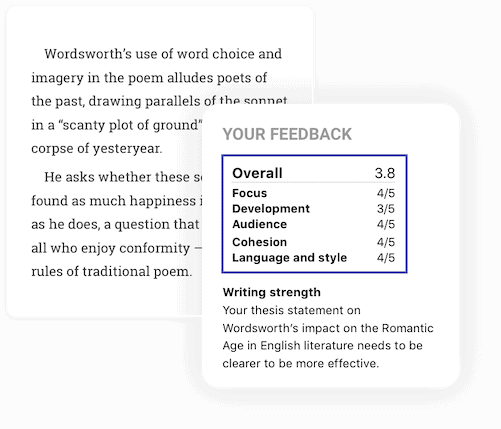

According to the Friedman’s ANOVA (see Table 2 ), the Slovene students’ factors influencing plagiarism can be formed into four homogeneous subsets, where in each subset, the distributions of the average values for the responses are not significantly different. At the top of the list is the existence of ICT and the Web (group 1). The second subset consists of teaching factors (group 4). The third subset is composed of academic skills, other reasons, and pride, in order from highest to lowest (groups 3, 7 and 6). The fourth subset is composed of other reasons, pride, pressure, and regulation, respectively (groups 7, 6, 5 and 2).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.t002

For the Slovene students, ICT and the Web were detected as the dominant factors influencing plagiarism and, as such, we investigated them in greater detail. A Friedman Test ( Chi-Square = 7.180, p = .066) confirmed that the distributions of the responses to the statements 1.1, 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8—those with the highest sample means—are not significantly different. Consequently, the average values (means) of the responses to the statements 1.1, 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8 are not significantly different. The average values of the responses for all the other statements (1.7, 1.6, 1.2, and 1.3 listed in the descending order of sample means) are significantly lower. A Mann-Whitney Test showed that there is no statistically significant difference between the distributions of the responses in the group of ICT and Web reasons considering gender (male, female) and motivation for study (lower, higher). For statement 1.2, a Kruskal-Wallis Test ( Chi-Square = 7.466, p = .024) confirmed that there are different distributions for the responses when the area of study is considered (technical sciences, social sciences, natural sciences).

According to the Friedman’s ANOVA (see Table 3 ), the German students’ factors influencing plagiarism can be formed into five homogeneous subsets, where in each subset, the distributions of the average values for the responses are not significantly different. At the top of the list is the existence of ICT and the Web (group 1). The second subset is composed of pressure and pride, in order from highest to lowest (groups 5 and 6). The third subset consists of pride, teaching factors and other reasons, respectively (groups 6, 4 and 7). The fourth subset is composed of teaching factors, other reasons and academic skills, in order from highest to lowest (groups 4, 7 and 3). Finally, the last subset consists of regulation (group 2).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.t003

Just like the Slovene students, for the German students ICT and the Web were detected as the dominant factors influencing plagiarism. That the distributions of the responses to the statements 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8—those with the highest sample means—are not significantly different was confirmed by Friedman Test ( Chi-Square = 5.815, p = .055). Consequently, the average values (means) of the responses to the statements 1.4, 1.5 and 1.8 are not significantly different. The average values of the responses for all the other statements (1.1, 1.7, 1.6, 1.2, and 1.3 listed in the descending order of sample means) are significantly lower. A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Tests also confirmed that the distributions of the responses to the statements 1.6 and 1.7 are not statistically significantly different ( Z = -0.430, p = .667). The same holds for statements 1.2 and 1.3 ( Z = -0.407, p = .684). A Mann-Whitney Test showed that there is no statistically significant difference between the distributions of the responses in the group of ICT and Web reasons considering gender (male, female), area of study (technical and social sciences (students of natural sciences were omitted due to the small sample size)) and motivation for study.

ICT and Web reasons were detected as the dominant factors influencing plagiarism for Slovene and German students. As can be seen in Table 1 , there are significant differences ( t = 4.177, p = .000 ) between the Slovene and German students regarding this factor. It seems that the Slovene students ( M = 3.69, SD = 0.56) attribute greater importance to the ICT and Web reasons than the German students ( M = 3.47, SD = 0.55). There are also significant differences ( t = 5.137, p = .000 ) between the Slovene and German students regarding regulation. It seems that the Slovene students ( M = 2.35, SD = 0.63) attribute greater importance to regulation reasons than the German students ( M = 2.05, SD = 0.61). Both, however, consider this factor to have the lowest impact on plagiarism overall. There are no significant differences ( t = 1.939, p = .053 ) between the Slovene students ( M = 2.56, SD = 0.67) and the German students ( M = 2.44, SD = 0.68) regarding academic skills. The Slovene students ( M = 2.87, SD = 0.68) attribute greater importance to teaching factors than the German students ( M = 2.56, SD = 0.72). The differences are significant ( t = 4.827, p = .000 ) . There are significant differences ( t = -3.522, p = .000 ) between the Slovene and German students regarding pressure, whereas the German students ( M = 2.71, SD = 0.91) attribute greater importance to this reason than the Slovene students ( M = 2.42, SD = 0.86). The same goes for pride. The German students ( M = 2.67, SD = 0.80) attribute greater importance to pride reasons than the Slovene students ( M = 2.43, SD = 0.84). The differences are significant ( t = -3.032, p = .003 ) . There are no significant differences ( t = - 0.836, p = .404 ) between the Slovene students ( M = 2.47, SD = 0.82) and the German students ( M = 2.54, SD = 0.94) regarding other factors influencing plagiarism.

We conducted an Independent Samples t-test to compare the average time (in hours) spent per day on the Internet by the Slovene students with that of the German students. The test was significant, t = -2.064, p = .004. The Slovene students on average spent less time on the Internet ( M = 3.52, SD = 2.23) than the German students ( M = 4.09, SD = 3.72).

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to gender (male, female) and the significances for the t-test of equality of means are shown in S3 Table for the Slovene students and in S4 Table for the German students. The average values of the responses for these statements are significantly different. They are higher for males than for females (except in the case of statement 3.8 for the Slovene students and 4.1 for the German students). Slovene and German male students think that they will not get caught and that the gains are higher than the losses. Both also think that teachers do not read students’ assignments.

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to area of study (technical sciences, social sciences, natural sciences) and the results for ANOVA for the Slovene students are shown in S5 Table . Gabriel's post hoc test was used to confirm the differences between groups. The significant difference between the students of technical sciences and the students of social sciences was confirmed for all statements listed in S5 Table . There were higher average values of responses for the students of technical sciences. The only significant difference between the students of technical sciences and the students of natural sciences was confirmed for statement 5.6 (there were higher average values of responses for the students of technical sciences). No other pairs of group means were significantly different.

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to area of study (technical sciences, social sciences) and the significances for the t-test of equality of means for German students are shown in S6 Table . For German students, only technical and social sciences were considered because of the low number of natural sciences students. The average values of responses for these statements are significantly different. They were higher for the students of technical sciences than for the students of social sciences.

The average values of the responses for individual statements according to the motivation of the students (lower, higher) and the significances for t-Test of equality of means are shown in S7 Table for the Slovene students and in S8 Table for the German students. The average values of the responses for these statements are significantly different. They were higher for students with lower motivation for both groups of students, except in the case of statements 2.1 and 6.6 for Slovene students.

We conducted an Independent Samples t-test to compare the average time (in hours) spent per day on the Internet by groups of low motivated students with groups of highly motivated students. For Slovene students, the test was not significant, t = -1.423, p = .156. For German students, the test was significant, t = 2.298, p = .024. Students with lower motivation for study ( M = 5.24, SD = 4.84) on average spent more time on the Internet than those with higher motivation for study ( M = 3.76, SD = 3.27).

The Chi-Square Test of Independence was used to determine whether there is an association between gender (male, female) and motivation for study (lower, higher). There was a significant association between gender and motivation for the Slovene students ( Chi-Square = 4.499, p = .034). Indeed, it was more likely for females to have a high motivation for study (76.9%) than for males to have a high motivation for study (61.6%). For the German students, the test was not significant ( Chi-Square = 0.731, p = .393).

In this study, we aimed to explore factors that influence students’ factors influencing plagiarism. An international comparison between German and Slovene students was made. Our research draws on students from two universities from the two considered countries that cover all traditional subjects of study. In this regard the conclusions are representative and statistically relevant, although we of course cannot exclude the possibility of small deviations if other or more institutions would be considered. Taken as a whole, there are no major differences between German and Slovene students when it comes to motivation for study and working habits. In both cases, more than two thirds of the students were highly motivated for study and more than 60% were working during their time of study. About 33% of the surveyed students spend on average two or less hours a day on the Internet, and about one quarter spend on average more than five hours a day on the Internet.

When it comes to explaining plagiarism in higher education, the German and Slovene students equally indicated the ease-of-use of information-communication technologies and the Web as the top one cause for their behaviour. Which does not lag behind other notions of current contributions to the topic of plagiarism in the world. Indeed, our findings reinforce the notion that new technologies and the Web have a strong influence on students and are the main driver behind plagiarism [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. An academic moral panic has been caused by the arrival in higher education of a new generation of younger students [ 39 ], deemed to be ‘digital natives’ [ 40 ] and allegedly endowed with an inherent ability for using information-communication technologies (ICT). This younger generation is dubbed ‘Generation Me’ [ 41 ], and it is believed that their expectations, interactions and learning processes have been affected by ICT. Introna, et al., Ma et al., and Yeo, agree that the understanding of the concept of plagiarism through the use of ICT is the main contributor to it being a problem [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. The effortless use of ICT such as the Internet has made it easy for students to retrieve information with a simple click of the mouse [ 45 , 46 ].

The Slovene students in our study nominated the teaching factor as the second most important reason for plagiarism. This result is also found in other studies, namely those of Šprajc et al. [ 30 ] and Barnas [ 47 ]. Young people in Slovenia are, like in other Western societies, given a prolonged period of identity exploration and self-focus, i.e., freedom from institutional demands and obligations, competence, and freedom to decide for themselves [ 48 , 49 ]. The results of the German students however, contradict this finding that teaching factors are one of the most important factors influencing plagiarism. Indeed, the top two factors influencing plagiarism for the German students are actually pressure and pride—and not teaching factors. Overall though, the findings for both the German students and the Slovene students are in line with e.g. Koul et al., who suggest that factors influencing plagiarism may vary across cultures [ 4 ]. Among German students, the pressure and pride in the second and third places in terms of importance are mostly reflected, which does not lag behind the mention of the author Rothenberg stated that in Germany today ‘pride could be expressed for individual accomplishments’ [ 50 ]. As far as the Slovene students are concerned, the authors Kondrič et al. presumed that there is a specific set of values in Slovenia, which perhaps intensify the distinction between the collectivist culture of former socialist countries and the individualism of Western countries [ 51 ]. This might shed light on why the Slovene students consider teaching factors as being one of the most important factors influencing plagiarism.

Furthermore, several studies have implied that individual characteristics, especially gender, play an important role when it comes to plagiarism [ 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 ]. A number of studies from around the world have shown that men more frequently plagiarise than women do. For example, Reviews of North American’s research into conventional plagiarism has indicated that male students cheat more often than female students [ 12 ]. The results we found are basically in line with these findings. Since the average values of responses are significantly different for male and female students, gender seems to play an important role in terms of plagiarism.

Park pointed out that one reason for plagiarism is efficiency gain [ 11 ]. About 15 years after this statement, the study at hand is empirical evidence that efficiency gain due to different forms of pressure is still a factor that influences students’ behaviour in terms of plagiarism. Lack of knowledge and uncertainties about methodologies are additional factors that are frequently recognized as reasons for plagiarism [ 11 , 17 , 18 ]. The results at hand support these studies since the responses about e.g. academic skills demonstrate students’ lack of knowledge.

Another interesting finding of our study shows that students with a lower motivation for study spend more time on the Internet, which complements our finding that the Internet is one of the simplest solutions for studying. The German students showed a somewhat higher level of motivation to study than the Slovene students, but the difference is not statistically significant.

We would nevertheless like to draw attention to the perceived difference, which refers to the perception of the factors influencing the plagiarism of the teacher factors and academic skills (Slovene students) and pride and pressure (German students). The perceived difference between students is one of the social dimensions that represents a tool to promote true motivation for study and proper orientation without ethically disputable solutions (such as plagiarism). In all this, it makes sense to direct students and educate them from the beginning of education together with information technology, while also builds responsible individuals who will not take technology and the Internet as a negative tool for studying and succeeding, but to help them to solve and make decisions in the right way. The main aim of this research into Slovene and German students was to increase understanding of students’ attitudes towards plagiarism and, above all, to identify the reasons that lead students to plagiarise. On this basis, we want to expose the way of non-plagiarism promotion to be developed in a way that will be more acceptable and more understandable in each country and adequately controlled on a personal and institutional level.

Conclusions

In contrast to a number of preliminary studies, the major findings of this research paper indicate that new technologies and the Web have a strong and significant influence on plagiarism, whereas in this specific context gender and socialisation factors do not play a significant role. Since the majority of the students in our study believe that new technologies and the Web have a strong influence on plagiarism, we can assume that technological progress and globalisation has started breaking down national frontiers and crossing cultural boundaries. These findings have also created the impression that at universities the gender gap is not predominant in all areas as it might be in society.

Nevertheless, some minor results in our study indicate that there are still some differences between Slovene and German students. For example, it seems like in Slovenia, teaching factors have a greater influence on plagiarism than in Germany. Indeed, in Germany, the focus should rest on the implementation and publication of a code of ethics, and on training students to deal with pressure.

This research focuses on only two countries, Slovenia and Germany. Thus, the findings at hand are not necessarily generalizable, though they do manifest a certain trend in terms of the reasons why students resort to plagiarism. Furthermore, the results could be a starting point for additional comparative studies between different European regions. In particular, further research into the influence of digitalization and the Web on plagiarism, and the role of socialisation and gender factors on plagiarism, could contribute to the discourse on plagiarism in higher education institutions.

Understanding the reasons behind plagiarism and fostering awareness of the issue among students might help prevent future academic misconduct through increased support and guidance during students’ time studying at the university. In this sense, further reflection on preventive measures is required. Indeed, rather than focusing on the detection of plagiarism, focusing on preventive measures could have a positive effect on good scientific practice in the near future.

Supporting information

S1 table. frequency distributions of the study variables..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s001

S2 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by nationality and results of the t-Test.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s002

S3 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by gender and results of the t-Test (SLO).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s003

S4 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by gender and results of the t-Test (GER).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s004

S5 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by area of study and results of the One-Way ANOVA (SLO).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s005

S6 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by study area and results of the t-Test (GER).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s006

S7 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by motivation and results of the t-Test (SLO).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s007

S8 Table. Descriptive statistics for items referring to the factors influencing plagiarism, by motivation and results of the t-Test (GER).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s008

S1 File. Individual data.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252.s009

- 1. Perrin R. Pocket guide to APA style. 3 rd ed. Boston, MA: Wadsworth; 2009.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Fishman T. We Know it When We See it is not Good Enough: Toward a Standard Definition of Plagiarism that Transcends Theft, Fraud, and Copyright. Paper presented at the 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Educational Integrity, NSW, Australia. 2009. Available from: http://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/09-4apcei/4apcei-Fishman.pdf

- 6. Hall TE. Beyond culture. New York: Anchor Books; 1979.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 8. Schwinges RC. (Ed.). Examen, Titel, Promotionen. Akademisches und Staatliches Qualifikationswesen vom 13. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert [Examinations, Titles, Doctorates, Academic and Government Qualifications from the 13th to the 21th Century]. Basilea: Schwabe; 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199694-044.003.0009

- 16. Gerdeman RD. Academic dishonesty and the community college, ERIC Digest, ED447840; 2000. Available from: https://www.ericdigests.org/2001-3/college.htm

- 27. Songsriwittaya A, Kongsuwan S, Jitgarum K, Kaewkuekool S, Koul R. Engineering Students' Attitude towards Plagiarism a Survey Study. Korea: ICEE & ICEER; 2009.

- 37. Razera D, Verhage H, Pargman TC, Ramberg R. Plagiarism awareness, perception, and attitudes among students and teachers in Swedish higher education-a case study. Paper Presented at the 4th International Plagiarism Conference-Towards an authentic future. Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK. 2010. Available from http://www.plagiarismadvice.org/researchpapers/item/plagiarism-awareness

- 39. Bennett S, Maton K. Intellectual field or faith-based religion: moving on from the idea of ‘digital natives’. In Thomas M, editor. Deconstructing digital natives. London: Routledge; 2011. pp. 169–185.

- 40. Prensky M. Digital wisdom and homo sapiens digital. In Thomas M, editor. Deconstructing digital natives. London: Routledge; 2011. pp. 15–29.

- 42. Introna L, Hayes N, Blair L, Wood E. Cultural attitudes towards plagiarism. Lancaster: University of Lancaster; 2003.

- 48. Puklek-Levpušček M, Zupančič M. Slovenia. In Arnett JJ, editor. International encyclopedia on adolescence. New York: Routledge; 2007. pp. 866–877. 10.1007/s10734-011-9481-4 .

- 49. Zupančič M. Razvojno obdobje prehoda v odraslost—temeljne značilnosti. [Developmental period of transition to adulthood—basic characteristics]. In Puklek-Levpušček M, Zupančič M, editors. Študenti na prehodu v odraslost [Students in transition to adulthood]. Ljubljana: Znanstveno raziskovalni inštitut Filozofske fakultete; 2011. pp. 9–38.

Advertisement

Understanding Undergraduate Plagiarism in the Context of Students’ Academic Experience

- Published: 19 March 2021

- Volume 20 , pages 147–168, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Jorge Ávila de Lima ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2311-1796 1 ,

- Áurea Sousa 2 ,

- Angélica Medeiros 3 ,

- Beatriz Misturada 3 &

- Cátia Novo 3

1275 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

Previous research has shown that student plagiarism is the product of interplay between individual and situational factors. The present study examined the relationship between these two sets of factors with a particular focus on variables linked to students’ academic context namely, their perception of peer behaviors, their experience of adversities in academic life, and their year of enrollment. So far, these situational features have received scant attention in studies of plagiarism conducted in most of Europe. A survey was carried out in a European higher education institution, involving a sample of 427 undergraduates. The data was analyzed via both conventional univariate and bivariate statistical analysis, and multivariate, multilevel modeling. The results suggest that awareness of peer plagiarizing and the experience of hardships in academic life, rather than level of academic achievement or year of study, are significantly related to plagiarizing, whereas heightened perception of the seriousness of plagiarism is associated with a lower likelihood of this type of behavior. The study also shows that students who plagiarize are more likely to be involved in other types of academic misconduct.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Student Perspectives on Plagiarism

Exploring the Perceived Spectrum of Plagiarism: a Case Study of Online Learning

Availability of data and material.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Adam, L., Anderson, V., & Spronken-Smith, R. (2017). ‘It’s not fair’: Policy discourses and students’ understandings of plagiarism in a New Zealand university. Higher Education, 74, 17–32.

Article Google Scholar

Akbulut, Y., Sendag, S., Birinci, G., Kiliçer, K., Sahin, M. C., & Odabasi, H. F. (2008). Exploring the types and reasons of Internet-triggered academic dishonesty among Turkish undergraduate students: Development of Internet-Triggered Academic Dishonesty Scale (ITADS). Computers & Education, 51, 463–473.

Aljurf, S., Kemp, L. K., & Williams, P. (2019). Exploring academic dishonesty in the Middle East: A qualitative analysis of students’ perceptions. Studies in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564262 .

Ashworth, P., Bannister, P., & Thorne, P. (1997). Guilty in whose eyes: University student perception of cheating and plagiarism. Studies in Higher Education, 22, 187–203.

Auer, N. J., & Krupar, E. M. (2001). Mouse click plagiarism: The role of technology in plagiarism and the librarian’s role in combating it. Library Trends, 49 (3), 415–432.

Google Scholar

Ba, K. D., Ba, K. D., Lam, Q., & D., Le, D., Nguyen, P. L., Nguyen, P. Q., & Pham, Q. L. . (2017). Student plagiarism in higher education in Vietnam: An empirical study. Higher Education Research & Development, 36 (5), 934–946.

Babaii, E., & Nejadghanbar, H. (2017). Plagiarism among Iranian graduate students of language studies: Perspectives and causes. Ethics & Behavior, 27 (3), 240–258.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barnhardt, B., & Ginns, P. (2017). Psychological teaching-learning contracts: Academic integrity and moral psychology. Ethics & Behavior, 27 (4), 313–334.

Blankenship, K. L., & Whitley, B. E. (2000). Relation of general deviance to academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 10, 1–12.

Blum, S. D. (2009). My word! Plagiarism and college culture . Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Bowers, W. J. (1964). Student dishonesty and its control in college . New York, NY: Bureau of Applied Social Research, Columbia University.

Bretag, B., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenberg, P., et al. (2018). Contract cheating: A survey of Australian university students. Studies in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788 .

Bunn, D. N., Caudill, S. B., & Gropper, D. M. (1992). Crime in the classroom: An economic analysis of undergraduate student cheating behavior. The Journal of Economic Education, 23 (3), 197–207.

Cebrián-Robles, V., Raposo-Rivas, M., Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M., & Sarmiento-Campos, J. A. (2018). Percepción sobre el plagio académico de estudiantes universitarios españoles. Educación XX1, 21 (2), 105–129.

Chien, S.-C. (2016). Taiwanese college students’ perceptions of plagiarism: Cultural and educational considerations. Ethics & Behavior . https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2015.1136219 .

Chirikov, I., Shmeleva, E., & Loyalka, P. (2019). The role of faculty in reducing academic dishonesty among engineering students. Studies in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1616169 .

Chudzicka-Czupała, A. (2014). Psychological and moral determinants in accepting cheating and plagiarism among university students in Poland. Polish Journal of Applied Psychology, 12 (1), 75–98.

Comas-Forgas, R., & Sureda-Negre, J. (2016). Prevalencia y capacidad de reconocimiento del plagio académico entre el alumnado del área de Economía [Prevalence and ability to recognize academic plagiarism among university students in economics]. El Profesional de la Información, 25 (4), 616–622.

Curtis, G. J., & Clare, J. (2017). How prevalent is contract cheating and to what extent are students repeat offenders? Journal of Academic Ethics, 15, 115–124.

Curtis, G. J., & Tremayne, K. (2019). Is plagiarism really on the rise? Results from four 5-yearly surveys. Studies in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1707792 .

Foltýnek, T., & Čech, F. (2012). Attitude to plagiarism in different European countries. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 60 (7), 71–80.

Foltýnek, T., & Glendinning, I. (2015). Impact of policies for plagiarism in higher education across Europe: Results of the project. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 63 (1), 207–216.

Freiburger, T. L., Romain, D. M., Randol, B. M., & Marcum, C. D. (2016). Cheating behaviors among undergraduate college students: results from a factorial survey. Journal of Criminal Justice Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2016.1203010 .

Geddes, K. A. (2011). Academic dishonesty among gifted and high-achieving students. Gifted Child Today, 34 (2), 49–56.

Gibson, C. J., Khey, D., & Schreck, C. J. (2008). Gender, internal controls, and academic dishonesty: Investigating mediating and differential effects. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 19 (1), 2–18.

Glendinning, I. (2014). Responses to student plagiarism in higher education across Europe. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 10 (1), 4–20.

Hensley, L. C., Kirkpatrick, K. M., & Burgoon, J. M. (2013). Relation of gender, course enrollment, and grades to distinct forms of academic dishonesty. Teaching in Higher Education, 18 (8), 895–907.

Hetherington, E. M., & Feldman, S. E. (1964). College cheating as a function of subject and situational variables. Journal of Educational Psychology, 56 (4), 212–218.

Hu, G., & Lei, J. (2015). Chinese university students’ perceptions of plagiarism. Ethics & Behavior, 25 (3), 233–255.

Ison, D. C. (2018). An empirical analysis of differences in plagiarism among world cultures. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management . https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1479949 .

Iyer, R., & Eastman, J. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty: Are business students different from other college students? Journal of Education for Business, 82 (2), 101–110.

Jensen, L. A., Arnett, J. J., Feldman, S. S., & Cauffman, E. (2002). It’s wrong, but everybody does it: Academic dishonesty among high school and college students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27, 209–228.

Jereb, E., Perc, M., Lämmlein, B., Jerebic, J., Urh, M., Podbregar, I., & Šprajc, P. (2018). Factors influencing plagiarism in higher education: A comparison of German and Slovene students. PLoS One, 13 (8), e0202252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202252 .

Jian, H., Li, G., & Wang, W. (2020). Perceptions, contexts, attitudes, and academic dishonesty in Chinese senior college students: A qualitative content-based analysis. Ethics & Behavior, 30 (7), 543–555.

Kerkvliet, J. (1994). Cheating by economic students: A comparison of survey results. Journal of Economic Education, 25, 121–133.

Kerkvliet, J., & Sigmund, C. L. (1999). Can we control cheating in the classroom? Journal of Economic Education, 30, 331–343.

Khathayut, P., Walker-Gleaves, C., & Humble, S. (2020). Using the theory of planned behaviour to understand Thai students’ conceptions of plagiarism within their undergraduate programmes in higher education. Studies in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1750584 .

Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., McKendall, M., & Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: How do business school students compare? Journal of Business Ethics, 72 (2), 197–206.

Lin, C.-H., & Wem, L.-Y. (2007). Academic dishonesty in higher education: A nationwide study in Taiwan. Higher Education, 54 (1), 85–97.

Love, P. G., & Simmons, J. (1998). Factors influencing cheating and plagiarism among graduate students in a college of education. College Student Journal, 32, 539–551.

Lowe, H., & Cook, A. (2003). Mind the gap: Are students prepared for higher education? Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27 (1), 53–76.

Lynch, K., & O’Riordan, C. (1998). Inequality in higher eEducation: A study of class barriers. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 19 (4), 445–478.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Treviño, L. K. (2012). Cheating in college: Why students do it and what can be done about it . Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Book Google Scholar

McCabe, D. L., & Treviño, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38 (3), 379–396.

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics & Behavior, 11, 219–232.

McKibban, A. R., & Burdsal, C. A. (2013). Academic dishonesty: An in-depth investigation of assessing measurable constructs and a call for consistency in scholarship. Journal of Academic Ethics, 11, 185–197.

Molnar, K. K. (2015). Students’ perceptions of academic dishonesty: A nine-year study from 2005 to 2013. Journal of Academic Ethics, 13, 135–150.

Newstead, S. E., Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Armstead, P. (1996). Individual differences in student cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88 (2), 229–241.

Newton, P. (2015). Academic integrity: A quantitative study of confidence and understanding in students at the start of their higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199 .

Olafson, L., Schraw, G., Nadelson, L., Nadelson, S., & Kehrwald, N. (2013). Exploring the judgment–action gap: College students and academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 23 (2), 148–162.

Park, C. (2003). In other (people’s) words: Plagiarism by university students – literature and lessons. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28 (5), 471–488.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Pulfrey, C., & Butera, F. (2016). When and why people don’t accept cheating: Self-transcendence values, social responsibility, mastery goals and attitudes towards cheating. Motivation and Emotion, 40, 438–454.

Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 25, 111–163.

Rettinger, D. A., & Kramer, Y. (2009). Situational and personal causes of student cheating. Research in Higher Education, 50, 293–313.

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms . Oxford, England: Harper.

Simon, C. A., Carr, J. R., Mccullough, S. M., Morgan, S. J., Oleson, T., & Ressel, M. (2004). Gender, student perceptions, institutional commitments and academic dishonesty: Who reports in academic dishonesty cases? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29 (1), 75–90.

Smith, T. R., Langenbacher, M., Kudlac, C., & Fera, A. G. (2013). Deviant reactions to the college pressure cooker: A test of general strain theory on undergraduate students in the United States. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 8 (2), 88–104.

Stephens, J. M. (2017). How to cheat and not feel guilty: Cognitive dissonance and its amelioration in the domain of academic dishonesty. Theory Into Practice, 56, 111–120.

Stone, T. H., Jawahar, I. M., & Kisamore, J. L. (2010). Predicting academic misconduct intentions and behavior using the theory of planned behavior and personality. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32 (1), 35–45.

Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Sutton, A., Taylor, D., & Johnston, C. (2014). A model for exploring student understandings of plagiarism. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38 (1), 129–146.

Szabo, A., & Underwood, J. (2004). Cybercheats: Is information and communication technology fueling academic dishonesty? Active Learning in Higher Education, 5 (2), 180–199.

Tibbets, S. G. (1997). Gender differences in students: Rational decisions to cheat. Deviant Behavior, 18, 393–414.

Tibbetts, S. G. (1999). Differences between women and men regarding decisions to commit test cheating. Research in Higher Education, 40 (3), 323–342.

Underwood, J., & Szabo, D. (2003). Academic offences and e-learning: Individual propensities in cheating. British Journal of Educational Technology, 34, 467–477.

Vowell, P. R., & Chen, J. (2004). Predicting academic misconduct: A comparative test of four sociological explanations. Sociological Inquiry, 74 (2), 226–249.

Walker, J. (1998). Student plagiarism in universities: What are we doing about it? Higher Education Research and Development, 17 (1), 89–106.

Walker, M., & Townley, C. (2012). Contract cheating: A new challenge for academic honesty? Journal of Academic Ethics, 10 (1), 27–44.

Wallace, M. J., & Newton, P. M. (2014). Turnaround time and market capacity in contract cheating. Educational Studies, 40 (2), 233–236.

Whitley, B. E., Nelson, A. B., & Jones, C. J. (1999). Gender differences in cheating attitudes and classroom cheating behavior: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles, 41 (9/10), 657–680.

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30 (6), 707–722.

Wowra, S. A. (2007). Moral identities, social anxiety, and academic dishonesty among American college students. Ethics & Behavior, 17 (3), 303–321.

Yeo, S. (2007). First-year university science and engineering students’ understanding of plagiarism. High Education Research & Development, 26 (2), 199–216.

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., & Moore, B. (2016). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A study of individual factors. Ethics & Behavior . https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, University of the Azores, Portugal; and Centro Interdisciplinar de Ciências Sociais – CICS.UAc/CICS.NOVA.UAc, R. Mãe de Deus, 9500-801, Ponta Delgada, Portugal

Jorge Ávila de Lima

Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of the Azores, Portugal; and CEEAplA, Ponta Delgada, Portugal

Áurea Sousa

Department of Sociology, University of the Azores, Ponta Delgada, Portugal

Angélica Medeiros, Beatriz Misturada & Cátia Novo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jorge Ávila de Lima .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

de Lima, J.Á., Sousa, Á., Medeiros, A. et al. Understanding Undergraduate Plagiarism in the Context of Students’ Academic Experience. J Acad Ethics 20 , 147–168 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09396-3

Download citation

Accepted : 24 January 2021

Published : 19 March 2021

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09396-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Undergraduate students

- Higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

According to USC's Office of Student Judicial Affairs and Community Standards , plagiarism is:

- The submission of material authored by another person but represented as the student's own work, whether that material is paraphrased or copied in verbatim or near-verbatim form.

- The submission of material subjected to editorial revision by another person that results in substantive changes in content or major alteration of writing style.

- Improper acknowledgment of sources in essays or papers.

Avoiding Allegations of Plagiarism

An allegation of plagiarism is intent-neutral . In other words, the reader cannot discern whether the absence of a citation was done deliberately or you simply forgot to add a citation or accidentally cited to the wrong source. Therefore, it is important to proofread your paper before you submit it to ensure you have listed all sources used during your research and that every in-text citation relates to a full citation in your list of references. This is also why it is important to keep track of everything you have used during the course of writing your paper so you can easily assess whether all your sources have been cited.

With this in mind, credit must be given when using one of the following in your own research paper:

- Another person's idea, opinion, or theory;

- Any facts, statistics, graphs, drawings, or other non-textual elements used or that you adapted from another source;

- Any pieces of information that are not common knowledge;

- Quotations of another person's actual spoken or written words; or

- Paraphrase of another person's spoken or written words.

To introduce students to the process of citing other people's work, the USC Libraries have created a useful online tutorial on avoiding plagiarism . It describes what constitutes plagiarism and offers helpful advice on how to properly cite sources. In addition, the Office of Student Judicial Affairs and Community Standards has also published, "Trojan Integrity: A Guide for Avoiding Plagiarism." This guide provides a comprehensive explanation for how to defend yourself against allegations of violating the university's policy on academic integrity.

If you have any doubts about whether to cite a particular source concerning an argument or statement made in your paper, protect yourself by citing the source or sources that helps the reader determine the validity of your work. Note that not citing a source not only raises concerns about the academic integrity of your paper, but, more importantly, it tells the reader that you did not conduct an effective or thorough review of the literature in support of examining the research problem. It also inhibits the reader's ability to review the cited source to obtain further information about what is being discussed in your paper.

Academic Integrity. The Writing Center. University of Kansas; Avoiding Plagiarism. Academic Skills Program, University of Canberra; How and When to Cite Other People's Work. Psychology Writing Center, University of Washington; Proctor, Margaret. "How Not to Plagiarize." University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Plagiarism. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Plagiarism. The Writing Center. Department of English, George Mason University. Avoiding Plagiarism. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Understanding and Avoiding Plagiarism. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University.

- << Previous: 11. Citing Sources

- Next: Footnotes or Endnotes? >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 11:14 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Recognizing & Avoiding Plagiarism in Your Research Paper

- Posted on January 26, 2024 January 26, 2024

Recognizing and Avoiding Plagiarism in Your Research Paper

Plagiarism in research is unfortunately still a serious problem today. Research papers with plagiarism contain unauthorized quoting from other authors; the writer may even try to pass off others’ work as their own. This damages the individual’s reputation, but also the entire class, school, or field, because one can never fully trust that writer’s work is genuine. Naturally, you don’t want to contribute to that problem.

Unfortunately, plagiarism doesn’t have to be intentional to be damaging. College students and even professionals often fail to properly cite their sources for anything that isn’t common knowledge. While accidental plagiarism is more innocent, it is not less dangerous as it can still get you in a great deal of academic trouble.

The good news is, as long as you put research integrity first, and do your plagiarism due diligence, you shouldn’t have anything to worry about.

Ready to learn all about research paper citation rules, and how to avoid getting caught in this trap? Let’s take a look.

What is Plagiarism in Research?

Plagiarism is the act of using someone else’s work or intellectual property without acknowledging what you’re doing. Before you can truly understand plagiarism rules, it’s critical to know what plagiarism is in academic writing. In a nutshell, work is considered plagiarized if it is not your own original work and is also not cited as someone else’s.

Plagiarism is unethical because it takes the blood, sweat, and tears of other writers and passes it off as yours, without real effort on your part. This can dilute someone else’s standing or lead to confusion down the line about where credit is due. If readers can’t tell whose work led to certain academic papers, data sets, or theories, the science and art worlds suffer.

Science writers, journalists, marketing experts, medical and dental researchers, and students, among others, have all been stung by misunderstanding these rules. Even a simple copy and paste without attribution or referencing the original author is enough to signal professional and/or academic dishonesty.

The bottom line is, if you’re using someone else’s text word-for-word, you absolutely must note where that work came from. This protects the ideas of others and upholds publication ethics for all of us. That means, of course, you need to spot any plagiarism red flags from the get-go.

What Types of Plagiarism Can Occur in a Research Paper?

Some of the most common forms of plagiarism that occur in research papers and other forms of academic writing are:

- In-text citations, in parentheses, without a corresponding citation in a bibliography or works cited page, which means people have trouble finding the true source

- Citing work incorrectly

- Not following the prescribed citation style, whether that’s APA, MLA, or Chicago, making it difficult or impossible for others to find the source

- Paraphrasing someone else’s work too closely without citing the source

- Using data or statistics from someone else without a proper citation

- Following the format of someone else’s work in a section or in the paper as a whole

- Attributing research to the wrong person, such as cutting and pasting someone else’s quote and attributing it either to an incorrect author, or simply not providing attribution at all

- Relying too heavily on just a few sources, meaning you are taking their ideas wholesale

The truth is, most of this plagiarism isn’t even on purpose. Indeed, unintentional plagiarism is a major source of confusion in academia, where you yourself don’t realize that you have committed it. Self-plagiarism poses a problem too and is when you reuse your own work without citing it. This is definitely considered plagiarism even though you are the original author. Although re-using your old work is allowed with citations, doing so without them passes off old work as original, which has two drawbacks:

- You are not obeying the spirit of the assignment, which is to put in the time to create something new with your own ideas.

- You create downstream confusion when people are searching for your work, which conflicts with the entire goal of citing sources.

Direct plagiarism also occurs; however, direct plagiarism is intentional. Intentional thievery is even worse because it is often disguised by the person committing it and therefore more harmful to the original author. Again, this leads to severe moral and ethical problems, as it dilutes the hard work of others. Considering the fact that it’s generally quite easy to detect direct plagiarism, it’s worthwhile for students to realize that committing plagiarism intentionally is never worth it.

In summary, there are many examples of plagiarism of which to be aware. All of these can lead to serious trouble if you’re not continually wary of the plagiarism research paper traps. Students should know that Blackboard and other online academic portals check for plagiarism . Professionals should know that serious plagiarizing can cost them licenses, grants, and standing among their peers.

In other words, it’s no joke. To avoid potential consequences, keep an eye out for the following plagiarism research paper warning signs.

Warning Signs of Plagiarism in a Research Paper

To avoid plagiarism, research papers must be free of uncited work that uses the ideas of others. That means indicating the original source every single time you use one, with a proper citation, in the correct style as dictated by your professor or industry.

While unintentional plagiarism can happen to anyone, knowing its signs can help students and professional authors realize when they need to rewrite or add a citation to their writing. That will help you stay on the good side of academia, respect others’ work and ensure your own work is always improving. When reviewing your paper, look for the following signs that you may have failed to cite sources properly.

Infrequent Use of Citations

If you simply don’t have very many citations in a long research paper, you are likely using the ideas of others without proper credit. Most well-researched papers use dozens of sources for a 10-page paper. That indicates that you are weaving together others’ work to express your own ideas.

However, if your work contains close to five or six citations, chances are you are relying too heavily on ideas that are not your own. This indicates that you need to search more carefully for ideas that belong to others in your writing and cite them. As another suggestion, you should probably seek additional different sources to support your argument.

Using Words That You Don’t Normally Use

Any section of your paper that contains a smattering of words that don’t fit into your existing vocabulary hints you’ve likely nabbed them from somewhere else. While it’s fine (and good!) to build your word bank, inserting non-typical words into your text is a good indication that you are also inserting the ideas of others without credit. Comb over such sections carefully to ensure you have properly accredited the original writer.

Changes in Tone and Sentence Structure

As with words you don’t use, tone and sentence structure that is alien to your writing should be a red flag. Look carefully at these sections, asking yourself:

- Are any of these sentences just reconstructions of someone else’s writing?

- If I rewrote this idea from the ground up, would it sound different?

- Is this the tone I’m even going for in this paper?

Changes in Font

Changes in the font used in your research paper is a dead giveaway. It indicates clearly that you have copied and pasted something into your paper, be that from an outside source or your own previous work. If you spot such a section, you should either rewrite it or source it accurately, and be sure to change the font to match the rest of your paper.

Tips to Avoid Plagiarizing

Avoiding plagiarism is truly easy. Simply provide citations for all research and ideas that you didn’t create yourself, in the correct styles. These styles include APA, most common for science and medical writing; MLA, common for the arts; and Chicago Style, usually used for publishing. You can also use the following tips for beating a plagiarism checker :